SEVEN

THE SEARCH FOR WHOLENESS AND HIGHER CONSCIOUSNESS

What is life, what is conscious life, and what do these have to do with the awakening of higher consciousness? Myths provide us with many insights. This final chapter looks in detail at two Egyptian neters, Heka and Maat, representing magic and order, and their roles in supporting a balance of forces within us required to awaken higher consciousness that aims toward a unified whole.

Two Principles of Creation: Heka and Maat

Two major principles of creation occur in the Egyptian myths: Maat and Heka. Maat is a relatively well-known neter, while Heka is almost totally unknown. Without these special beings we cannot understand the full significance of the ancient view of creation and the awakening of higher consciousness. They also provide us with an explicit link to the Duat, enabling us to better understand how the Egyptians regarded appearance in the Duat as rebirth into another world.

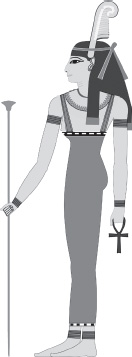

Heka is customarily associated with magic, and Maat is linked with cosmic order, truth, and justice. They first appear in the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, in relation to Atum after he differentiated himself from his surroundings as a distinct entity. They arise before any other neters are born, similar to Enki and Ninhursag as described in the Sumerian fragments of the creation myth. Parentage is not specified for either one, which implies that they were an essential part of the act of creation itself. In fact, they are often called “creation gods” by conventional archaeologists. Maat (figure 7.1) has become well recognized in translations and literary comments concerning the Egyptian view of life in the later dynasties. She is often mentioned with regard to the death and the accession of the pharaohs, who were judged on how fully they respected her properties of cosmic order, truth, and justice. Their rule of Egyptian society was considered to be “great” when her properties were reflected in their lives and rulings. Because of the frequency of rituals of invocation of Maat, she may have been the best known of all of the Egyptian neters. Her role as a creation principle in relation to the pharaohs is well established.

Figure 7.1. Maat. Illustration by Jeff Dahl.

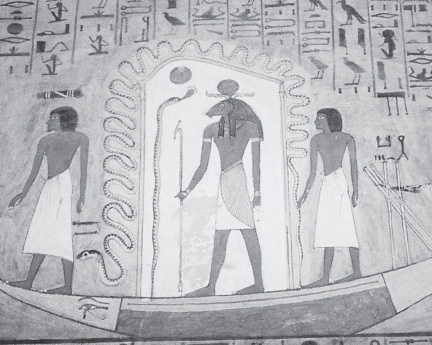

Figure 7.2. Heka attending Khnum. Heka appears directly behind the chamber room of Khnum, on the right-hand side, holding the snake’s tail. His hieroglyphic name is to the right of his shoulder. From the burial chamber in the tomb of Ramses I on the West Bank, Luxor.

In contrast, her male counterpart, Heka (figure 7.2), seems relatively obscure in the literature outlining Egyptian mythology. He seems to underlie the continuation of creation beyond the first arising of awareness that occurred within Atum. Heka seems to fill a particular need for a strong, active “force” that can support and sustain continuing acts of creativity. That is, while Atum and Kepherer, the neter of “becoming,” express the urge to create, this cannot take place automatically or by chance, even among the neters. Heka represents the force of intention that is essential for creation.

Heka’s force was needed to initiate the wider scope of creation, a force that emanated from the highest living principle, Atum, and descended in stops and stages into the realm ruled by the pharaohs. This force is so mysterious and unknown to us today that we refer to it as “magic.” It is a mystical force that the Egyptians invoked in relation to many aspects of creativity, including the insight that must exist to support the balance necessary for life, even at our mundane level. While our egos might seek to take credit for such insights, on reflection we recognize that its force is really beyond the individual attributes of most of us, belonging more appropriately to the sphere of the spirits.

These two balancing forces, Maat and Heka, underlie and unify various influences essential to the ultimate organization of our world.

A Case for the Importance of Heka

One of the challenges of appreciating the balance between Maat and Heka has been the difficulty in identifying Heka in the texts. He is mentioned by name only twice by Budge in his translation and interpretation of the Book of Coming Forth by Day.1 In addition, in chapters 23 and 24 of this translation there are several references to “magic” as a noun, which Budge translates as “charms.” This clearly relates to Heka’s full and proper name as the neter of magic. Heka is also rarely mentioned in the Pyramid Texts. The index to the six Pyramid Texts for which Allen gives translations shows only two dozen references to “magic.”2 Allen’s index doesn’t mention the neter Heka at all!

Curiously, the name Heka was clearly used in the original Egyptian texts, but in the translations what emerges is an indirect reference to the field of magic. Obviously Egyptologists have been reluctant to closely associate a neter with magic. In our time, at least in the conventional scholarly world, the indirect, less committal reference seems more “objective.” We need to keep the reluctance of these scholars in mind when attempting to understand the role of magic in creation, particularly when referring to their translations.

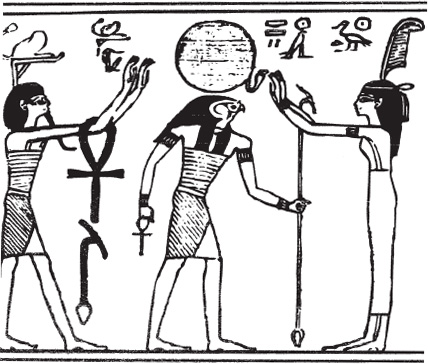

The first mention of Heka (as Hek) by Budge was in reference to a remarkable illustration from the tomb of Seti I that he used in his translation of the Book of Coming Forth by Day. It places Heka clearly in the creation myth of Heliopolis, cementing his importance in the Egyptian pantheon while offering a more succinct presentation of the created world than is possible with words alone. We present a version of this illustration from the tomb of Ramses VI in figure 7.3.3

Figure 7.3. Nun, the primeval sea, holds up the boat of creation with Heka and Maat as the third and fourth figures on the left of the scarab beetle. From the tomb of Ramses VI. From Naydler, Temple of the Cosmos, figure 2.15.

Figure 7.3 shows an image of Nun arising from the primeval sea, holding the boat of the sun in her upraised arms. In the boat the beetle, Kepherer, holds up the sun disk, which is being received by an upsidedown Nut. Although difficult to see, she is standing upside down on the head of Osiris. The accompanying hieroglyphs, in front of Osiris, read “(This) Sky receives Ra.” Inside the circle formed by the curved body of Osiris at the top we find written “(This) Osiris encircles (the) Duat.” In the boat, Maat and Heka are shown with their early hieroglyphic names above their heads, standing third and fourth to the left of the beetle. Thus, in this one figure we are shown the essential elements leading to the creation of the world of Atum, the world from which Ra eventually arose. Extending beyond this world of Ra is the realm of the Duat, which is here shown to be encircled at the top of the figure by the body of Osiris, who is usually depicted in the Egyptian murals and writings as the neter who rules the Duat. This dramatic depiction shows the main sequence of events that is spelled out at length in the Heliopolitan version of creation.

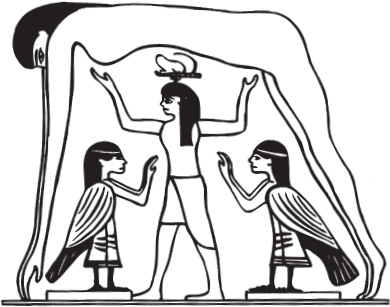

Figure 7.4 shows Heka and Maat together in an image from the papyrus of Khensumosi. In it, they stand on opposite sides of the great god of creation, shown in the form of Ra-Herakti. They are wearing typical head ornaments of the later dynasties. Heka has the hieroglyph of the hindquarters of a lion above his head, symbolizing the great strength of his special powers. Hanging on his right arm is the symbol for life (the ankh), and below it is the symbol for prosperity or wealth (the was scepter). Both of these symbols are also carried by Ra-Herakti. On the other side of Ra-Herakti stands Maat in a posture complementary to that of Heka, with the customary feather of Shu upon her head.

These figures show that Maat and Heka are of great importance in the Egyptian pantheon of neters. Figure 7.4 portrays them as principles of creation. One more indication of their similarity in importance is that they also appear together elsewhere in depictions for the hours of the day.4 Maat appears as the first hour and Heka as the tenth hour.

Figure 7.4. Heka and Maat on either side of Ra-Herakti with their individual insignia: the hindquarters of a lion above the head of Heka, on the left, and the feather of Shu upon the head of Maat. From Naydler, Temple of the Cosmos, figure 6.3.

Characteristics of Heka Relating to the Awakening of Higher Consciousness

As we suggested earlier, the concept of Heka (magic) has been subject to the unrecognized personal biases of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century translators. The Egyptian view of magic is particularly vulnerable to slanted Western attitudes. Christian scholars seem reluctant to accept the neter Heka as a magician, despite the biblical story of the birth of the Christ being heralded by the appearance of three magi, or wise men. Aside from this story, magic and magicians have not been welcomed in the West for several centuries, largely as a carryover from the almost forgotten Inquisition definition of the heretical. Since medieval times, magic has been officially regarded by the Roman Catholic Church as opposed to religion and has often been subject to their official scrutiny. As late as the seventeenth century, near the dawning of the scientific age, Newton was writing somewhat esoteric notes of his personal interests in his diaries in code, apparently so that they could not be easily probed by uninformed readers or inquisitors. In 1662 the Royal Society was founded in Great Britain “to improve Natural Knowledge,” i.e., science and rational studies. In spite of this rise in science in the Western world, superstitions surrounding magic continued. For example it was only in 1694 that the last “witches” were burned at the stake in Salem, Massachusetts.5 The suppression of the concept of witches and magic continued to at least the 1800s and possibly to today.6 The Inquisition, which lasted for centuries, was clearly not a time for open debates about topics that could be seen as challenges to the power brokers of the day.

We may wonder how such events could still cause unconscious anxiety in today’s world. Such attitudes may still live on, perhaps in the form of stories told to us when we were young. The subject is avoided in adult conventional life and seems to have been especially sidestepped in the “serious” scholarly interpretation of Egyptian myths. Indeed, perhaps partly because of difficulties in interpreting the Pyramid Texts, as well as sections of the Book of Coming Forth by Day, mid-twentieth-century translators dubbed the recitations that make up these books “spells,” as though they constitute some kind of parlor magic of no real importance. We need to remain fully alert to the fact that this problem can still cause difficulties in modern attempts to appreciate the subtlety of the Egyptian views of creation and of the neters.

As we venture into a more detailed examination of Heka and Maat, it is useful to recall two points we made earlier with respect to the mythology of the ancient world. First, in both the Sumerian and Egyptian myths, as we noted in chapter 2, all of the initial creation took place in the world of the gods. We are therefore considering events in a world whose properties are of a higher, esoteric organizational order than our material world. Second, we need to consider the arising of the neters Ptah and Seth. In chapter 2 we pointed out that the Egyptian creation myths favor the resolution of opposites. The synthesizing forces of creation, represented by the neter Ptah, are aimed at maintaining human civilization. What is called “evil” in the world of humans did not exist in the world of the neters, and so we find instead a concept closer to chaos or disorder, represented by Seth.

Heka and Maat seem to participate in a similar resolution of opposites. Maat, representing cosmic order, truth, and justice, appeals to form and reason, reflecting attitudes of intellectual as well as emotional life. Maat, however, does not represent the love or justice found at our personal level. Rather, Maat’s love and justice are on the scale of her cosmic unity. Quiet contemplation of this property of Maat may lead to comprehending her as a unifying force that we can then compare with Heka. To serve in this pairing with Maat, his magic must be equal in power to hers.

In the history of Western civilization great efforts have been made to describe magic as a force against the laws of nature. Our study of Heka shows that this is a false interpretation—at least from the ancient Egyptian point of view. Changing our perspective helps us to comprehend this alternative viewpoint. Versluis in The Philosophy of Magic emphasizes that the Egyptians considered magic an essential force of life, not a cause of phenomena in our world so much as an effect.7 The notion that magic is a cause rather than an effect is commonly mistaken in the present day. This results from a general neglect of the concept of levels of phenomena in modern day Western society. The Egyptians believed that phenomena at levels higher than that of humans result in effects that we, in our ignorance of real causes, think overturn the normal laws of cause and effect. Keeping this distinction of cause and effect in mind, we can appreciate that with regard to magic, the power of the neters is only reflected in our world, not caused in it. To us, at our lower level, actions at higher levels are seen as an invasion that cannot occur “according to law.” Instead of seeing such phenomena as magic expressing higher dimensions, we treat magic as an evil caused by imagined unlawful circumstances personified by a humanoid “devil.”

Magic in the Pyramid Texts

As we noted earlier, modern scholars seem to avoid direct mention of Heka as neter of magic in their translations of the Pyramid Texts, but in a number of instances direct mention would make the meaning of the translations considerably easier to understand. In any case, we see the use of the word magic to signal that we are dealing with an influence that originates at the spiritual level of the world of the neters.*11

The Pyramid Texts are a group of writings in hieroglyphs carved into the ceiling and walls of pyramids of the Old Kingdom from 2353 BCE to 2107 BCE. Beginning with the Pharaoh Unis at the end of the Fifth Dynasty, various compilations with slight variations of the Texts are found in pyramids through the Sixth Dynasty and one at the beginning of the Eighth Dynasty. In succession, these are the pyramids of Teti, Pepi I, Ankhesenpepi II (wife of Pepi I), Merenre, Pepi II, Neith (wife of Pepi I), Iput II (wife of Pepi), Wedjebetni (wife of Pepi II), and Ibi, a pharaoh of the Eighth Dynasty. Although Heka is not often recognized in the Pyramid Texts, magic is often mentioned.

In texts from the Pyramid of Unis, we find a reference to magic in what Allen (in The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts) refers to as Recitation 211. The introduction reads:

“How beautiful is the sight, how pleasing the vision,” say the gods, “of this god’s going forth to the sky, of Unis’s going forth to the sky, with his bas atop him, his ferocity at his sides, his magic at his feet.

Geb has acted for him just like he was acted for in the same event.”8

Ferocity is an attribute of Heka in all the Pyramid Texts and in the Book of Coming Forth by Day, where he is also named God of Magic. A related theme is found in the Pyramid Texts from Teti, having to do with his ascent to Nut. In Recitation 9, Teti is referred to as the doorkeeper of Horus and the gatekeeper of Osiris. His magic can “soothe” the wounds of Horus. He does this “with the magic that is in the gods when he first comes into being.”9 This provides further evidence that this magic is indeed an aspect of Heka in his role as one of the main principles of creation. In a text given in the Pyramid of Pepi I, Recitation 486, it is further pointed out that “the magic in the belly of Meryre belongs to him, as he emerges and ascends to the sky.”10 “Meryre” is a statue within the pyramid that represents the Pharaoh Pepi I in his effort to emerge and ascend, which requires the functioning of magic to be successful.

In an unrelated text from the Pyramid of Pepi I, Recitation 323, a great magical power is assigned directly to Pepi:

Tremble, sky; shake, earth—before this Pepi! Pepi is Magic. Pepi is one who has magic.

This Pepi has come that this Pepi may akhify Orion, that this Pepi might bring Osiris

to the fore, that this Pepi might put the gods on their seats.11

In this case, not only is Pepi assigned the power of Heka, but the text also points out how, with the power of magic, the constellation of Orion is akhified (made into the highest spiritual order of gods) and thus understood to be the visible heavenly representation of Osiris, who is assisted by this great magic of Pepi to return to his seat. That Osiris had exchanged his original “seat” for his son, Horus, as King of the Living, as he himself, became King of Eternity, is stated in chapter 17 of the Book of Coming Forth by Day.

Further reference to the ferocity and magic of the pharaoh is made in the pyramids of Unis, Recitation 211 and Pepi I, Recitation 325. In the amplified version of Pepi I, proclamations are now made by Isis and Nephthys, rather than being attributed to the neters in general. They describe the role of Pharaoh Pepi as he goes forth surrounded by the magic of Heka and the important consequences of his becoming a neter. The text goes on to say:

“I shall get for you the gods who belong to the sky,” (says Isis), “and they will join for you the gods who belong to the earth, that you might exist with them and go on their arms.”

“I shall get for you the bas of Pe” (says Nephthys), “and the bas of Nekhen will be joined together for you.”

“Everything is for you—Geb is the one who argued for it with Atum, for it is what was done for him—and the Marshes of Reeds, the Horus Mounds and the Seth Mounds. Everything is for you: Geb is the one who argued for it with Atum, for it is what was done for him.”12

A further explication of the same text is given in the Pyramid of Pepi I, Recitation 512, and two variations come from the Pyramid of Pepi II, Recitations 422 and 430. Another version is given in the Pyramid of Merenre, Recitation 261. The Pyramid of Queen Neith, Recitation 11, contains a version in which the commentators are also Isis and Nephthys.

These variations are significant not only because of the magic described surrounding the pharaoh as neter, but also because they introduce the idea that each pharaoh, in his magical condition capable of “ascending,” is important in the world of the neters due to his role of reconnecting the sky to the earth. In each case, the neter Geb, the neter of the earth, petitions Atum, the original neter of creation. The reunion of the representatives of sky and earth is equated with the union of the neters of Upper and Lower Egypt, Pe and Neken.

Rundle Clark points out and as we noted in chapter 2, splitting apart Nut and Geb introduced into the world the pain of separation. In the Pyramid Texts it is apparent that the magic of the ascending pharaoh plays the important function of removing this pain of separation by bringing about a reunification between the sky and the earth. It is in this sense that we use the modern psychological language of a “reconciliation of opposites.” In this case the opposites were set up in the divine world by the act of creation, involving the sundering of the unity of the sky and the earth. The philosophically and psychologically important reconciliation of this original sundering is described in the Pyramid Texts as an act that is promoted by the magic of Heka.

We have not, however, exhausted the accounts that spell out all of the various attributes of Heka as the neter of magic. In fact, a somewhat different version of magic is given in Pepi I, Recitation 536, which reads:

So, whoever shall [worship] Osiris and do this magic for him, he will be alive forever. Pepi is the one who worships you, Osiris, [Pepi] is the one who does [this]magic for you: [so he will be] alive forever.13

This is the only instance we know in which magic is specifically attributed the capacity of giving eternal life. However, it is of significance that in Unis Recitation 146 it is said of Unis,

Ho, Unis! You have not gone away dead: you have gone away alive.14

Following this, Unis Recitation 153 says,

He has come to you, Red Crown; he has come to you, Fiery One; he has come to you, Great One; he has come to you, Great of Magic—clean for you and fearful because of you.

May you be content with him. . . .

He has come to you, Great of Magic: for he is Horus, encircled by the aegis [protection] of his eye, the Great of Magic.15

In Unis Recitation 154, this message continues as:

Ho, Red Crown! Ho, Curl! Ho, Great One! Ho Great of Magic! Ho Fiery One,

May you make Unis’s ferocity like your ferocity,

may you make this Unis’s fearsomeness like your fearsomeness, . . .

may you make the love of this Unis like love of you.16

These recitations together establish not only that Unis was taken into the sky without having “died,” but that Heka’s powers in the spirit world are considerable. It is important to remember that these attributes of the neters are not in the physical world of our day-to-day lives, but are esoteric, dealing with our levels of higher consciousness.

In the Pyramid of Pepi II, however, there is a further explication of the theme of magic, this time also consisting of the magic attributed to the eye of Horus, which was seized by Seth in their prolonged battle. In Pepi II Recitation 106–111, the power of magic is passed on to Pepi II in the verse “Osiris Pepi Neferkare, accept Horus’s eye, of which you said: ‘Its magic is greater than mine.’”

We reach this conclusion because in the Pyramid Texts of Pepi II, on the occasion of his ascent, he is given the name Osiris Pepi Neferkare. The name Osiris is a formula assigned in the Book of Coming Forth by Day to the person being transformed, and it specifies that he or she has become a candidate for eternal life, ruled by Osiris in the Duat. It is thus this “dead” Pepi II who is granted the title Great of Magic. Following this, in Pepi II Recitation 531, the great god Djehuti is called “Lord of Magic.” Furthermore, in the Pyramid of Queen Neith Recitation 225, it says:

Horus has made your magic great in your identity of Great of Magic. You are the great god. . . .

You are in control of the Nile Valley through this Horus through whom you exercise control; you are in control of the Delta through this Horus through whom you exercise control. You shall exercise control and defend your body from your opponent.17

Pepi II is thus greeted as ruler of a united Upper and Lower Egypt, in a union that appears to take place in the world of the Duat, which in figure 7.3 is shown to be encircled by the body of Osiris at the top. Indications that the “departed” Pharoah has entered the Duat do not occur in the earlier Pyramid Texts of Unis, Teti, Pepi I, or Merenre. We are not certain whether this is an intentional difference among the texts, but there appears to be little in the Pyramid Texts that is stated casually.

In the verse found in several pyramids as Pepi I Recitation 62, Merenre Recitation 52, Pepi II Recitation 322, and Neith Recitation 227 the neter Geb, who is responsible for having spoken to Atum in the interests of healing the scission between the sky and the earth, is in his role as the eldest son of Shu, the neter who originally carried out the separation of Nut and Geb, long before the creation of humans. Figure 7.5 shows Heka in the traditional place of Shu in the act of lifting Nut to her position in the sky, hence separating her from Geb, the neter of earth.18 This demonstrates the relatively high level of Heka in the hierarchy of the neters. In this verse found in multiple pyramids, the Pharaoh who has become Osiris in “death” is presented to Geb. The text reads:

Gather him to you, that [what is against him] might end.

You alone are the great god, for Atum has given you his inheritance. He has given you the Ennead gathered, and Atum himself as well amongst them, gathered for his senior son’s son in you, for he has seen you effective, your heart big (with pride); persuasive in your identity of the persuasive mouth, the god’s elite one; standing on the earth and judging at the fore of the Ennead, your fathers and mothers . . . .

You are the lord of the entire earth, in control of the Ennead and every god as well. . . . You are the god who controls all the gods, for the eye has emerged in your head as the Nile-Valley Great-of-Magic Crown, the eye has emerged in your head as the Delta Great-of-Magic Crown, Horus has followed you and desired you, and you are apparent as the Dual King in control of the gods and their kas as well.” 19

It is of particular interest to note that when either Heka or Shu is shown holding up the sky, their arms are bent at the elbows and extended upward in the same form that is used in hieroglyphs to represent the sound ka (figure 7.5). The supporting bird images also extend their arms up in the same manner. The ka, represented by the glyph of the upraised arms bent at the elbow, is the Egyptian name for the soul that is created by Khnum on his potter’s wheel at the same time as the material pharaoh is created for birth in the human world. That is, this ka, created by Khnum, is intimately related to the function of the pharaoh, perhaps by lifting the human soul toward celestial or spiritual influences in the same way that Heka and Shu lift the sky above earth.

Figure 7.5. Heka, the neter personifying magic, in the place of Shu, lifting Nut supported on each side by images of the ka with arms raised. Twenty-first Dynasty coffin. From Naydler, Temple of the Cosmos, figure 3.13.

In a number of illustrations of the theme the arms are supported at the elbows by rams. In Egyptian, the word for ram is pronounced ba, the name used to describe the next higher level of the soul than the ka. Ba is thus a further aspect of the developing soul that is on its way to becoming spirit, or akh, a state of spiritual being that shines forth like the sun, Ra.

We would like to draw attention to Pepi I Recitation 486, where it is pointed out that the characteristics of all the various neters are incorporated as “limbs” and other body parts of Pepi Meryre as he ascends through the sky. It states:

The magic that appertains to me is that which is in my belly; . . .20

It goes on to say that if any god fails to help “lay down a stairway” by which Pepi can ascend, he will have no benefit from the whole process of transformation that will take place. The text continues:

This Pepi is not the one who says this against you gods: magic [Heka] is the one that says this against you gods. Meryre is the one who belongs to the mound that has magic, as he emerges and ascends to the sky.

Any god who will lay down a stairway for Pepi as he emerges and Meryes ascends to the sky, and any god who will provide his seat in the great boat as he emerges and this Pepi ascends to the sky, the earth will be hacked up for him, a deposited offering will be laid down before him, a bowl shall be made for him . . .

Any god who will receive the arm of this Meryre to the sky when he has gone to

Horus’s enclosure in the Cool Waters, his ka will be justified before Geb.21

In summary, the Pyramid Texts indicate that magic is not only inherent in the creation of the neters as inheritors of the greatness of Atum, but that it also penetrates the human world, including the affairs of the pharaohs of Egypt and those who are ruled.

The Need for Attention and the Role of Magic

It is relevant to our consideration of magic to make further reference here to a related power that is necessary for our individual internal perception. Kingsley writes extensively on the Ancient Greek concept of mêtis.22 The word was used by the earliest Greeks as the name of the titan Mêtis. The Greek gods Oceanus and Tethys gave birth to the goddess Mêtis, and thus she is of an earlier age than even Zeus. She was the first spouse of Zeus and mother of his first daughter, Athena. She was said to be both a threat to and an indispensable aid to Zeus, and her name connotes both the “magical cunning” of the trickster Prometheus and the “royal mêtis” of Zeus. The Orphic tradition enthroned Mêtis side by side with Eros as primal cosmogonic forces. Plato made Poros, or “creative ingenuity,” the child of Mêtis.23

Kingsley presents mêtis as “the particular quality of intense alertness that can be effortlessly aware of everything else at once.”24 He points out that such alertness requires a good deal of magic and trickery to avoid the illusory distractions of life. It offers the principal route to what the earliest Greek philosophers, in their prepared state, considered necessary for a balanced contact with the sacred impulses that maintain life. He says that mêtis is at the origin of “a teaching to make sure that no illusory person with any illusory tricks in this illusory world will ever manage to outwit or get the better of him [the observer].”25 That is, only as long as we can individually exercise the ultimate property of attention and discrimination, resulting from our exercise of mêtis within ourselves, will we have the power to distinguish our real existence from the illusory that we take to be our daily lives.

Parmenides, in a poem translated and interpreted by Kingsley, points out that the lack of the power of discrimination in our illusory world underlies our difficulty in understanding life. Parmenides travels to the “depths of darkness at the furthest the edges of existence,”26 which is very reminiscent of the Sumerian netherworld and Egyptian Duat. In that realm he is directly instructed by a goddess on the challenges of seeing his real world and the need for mêtis before sending him back to his ordinary life.

Parmenides learns that it takes a bit of magic and trickery to keep one’s attention from being distracted. It is clear from the special conditions of Parmenides’ travel and from the actions and attitudes of his “successor,” Empedocles, that this advice to develop discrimination is not related to any ordinary wariness that we might try to cultivate. In fact, Parmenides’ instructions coming from a goddess point out that this effort of attention could only emanate from the level of the gods. These god-like powers serve as the foundation for the sacred undertaking that was learned through incubation of the initiate in the course of worship of Apollo.

Our present day difficulty with recognizing the power of such ancient practices lies in our modern Western sensibilities that are heavily weighted toward the rational. We have trouble ensuring that our own sense of discrimination is at the intended level without recognizing the necessary role of mêtis or magic in our efforts.

We have been given ample evidence of the need for the transcendent power of magic in the translations of the Pyramid Texts. Following the reasoning of Versluis, we can appreciate that while the effects of magic may appear to us at our level of perception, they must originate from an esoteric power of discrimination that arises from the gods. These magical effects can be transformative; they require of us in the human world special efforts to understand.27 Those who are unprepared cannot hope to comprehend the appropriate levels of higher attention.

Parmenides’ warnings about contentment with a superficial level of understanding may have originated in Egypt and been passed on to him in ways unknown. In fact, it is important to note that Parmenides and Empedocles both belonged to traditions that can be traced to Homeric times (circa the fifth century BCE). Borrowing important concepts from the Egyptians would account for the glowing accounts of the later Greek philosophers, who extolled the secrets they encountered in the Egyptian temples when they were first taught the stories of creation described in chapter 2. The Greeks also honored the secrecy demanded of them by this teaching.

A heightened self-awareness is certainly required where strange gods or objects symbolize perceptions that are unfamiliar in our cultural memories. We have presented a number of examples in this book. The difficulties that Gilgamesh encountered in his search for immortality direct our attention to a number of hard to recognize but credible distinctions between the Land of the Living, where we experience our life, and the Land of Utnapishtim, where we might, with Gilgamesh, seek help in reaching the objects of our aspirations. The preparation and continued attention of the pharaoh as he travels through the Duat and deals with its many challenges is another example. The two trees in the Garden of Eden suggest a parallel symbolism that requires fine discrimination to unlock. Kingsley points out how both Parmenides and Empedocles taught that sharp discernment is not an automatic skill.28 Special openness, particularly engaging that magical quality he calls “mêtis,” is needed if we are not to find ourselves immediately assigning the unfamiliar to pre-established categories. Such openness is, to quote a friend, “no cheap thing.”

The search for higher consciousness can start only from realizing a sense of something missing or recognizing a need for what we do not understand—something internal and real in the present. It cannot be supposed that the searcher, figuratively fumbling in the dark, can know what is sought or what might be found. What is required is a freedom or openness to other influences. Once this openness has been achieved, one can appreciate that what needs to be learned does not come from the symbols of the ancients. In fact, it is unlikely to be found within the myths. Rather, it must be found within the whole of our personal experience of life. Many of us are fortunate to have tasted higher energy within ourselves during fleeting moments throughout our lives. Understanding becomes possible once one can consider them as glimpses of what might be called eternity and wholeness. These come to us when we participate in that extra dimensionality of being that, for want of a better term, we call the higher consciousness within us—the Self.

In this way, the alchemists fortify the lesson of the myths that the recognition of the meaning of life involves some essential, qualitative process of change that is so profound that our view of ourselves must undergo a transformation. We discover that the search for higher consciousness leads not to the stars, but to ourselves.

The Relationship between Heka and Maat

We have recounted the characteristics of Heka as magic for two reasons. First, Heka and Maat, in the Egyptian worldview, were initially regarded as a pair of opposites that must find reconciliation. Second, after Atum created these first two principles, he became aware of himself.

If magic is the equivalent of the religion of the Egyptians, the greatness of Heka’s power becomes clearer to us. Such power is hard to conceive in the Western world with its history of sectarian religions, but given the evidence of the Pyramid Texts, which are the first written texts of Egypt, we see the remarkable power of magic. Such incredible power must be balanced. We find the requisite balance in the attributes of Maat. Perhaps the power of Maat could be understood from her description as the neter of cosmic unity alone. But knowing that she is also truth and justice, we conceive in her a strength and breadth that we would find difficult to comprehend were it not for her juxtaposition with the awesome power of Heka. Because Heka as magic underlies the seemingly limitless process of creation, it must be reconciled with forces of a similar scale, such as those of Maat. She allows this remarkable created world to achieve a state of organization that affects the purpose of life itself.

Heka and Maat act throughout all levels of the worlds of both neters and humans. Pharaohs, who were considered the embodiment of the great neter Horus, were judged on the extent to which they satisfied the properties of Maat. Her significance in this regard lends insight into how Egyptians perceived the need to balance ultimate power with cosmic unity, truth, and justice. It was believed that the pharaohs’ actions in this world would have consequences in the Duat and beyond.

This chapter directly affirms that all the transformative processes we have been told of indeed emanate from the underlying influence of magic and order as personified by the Egyptian neters Heka and Maat, the two primary principles of creation. As Naydler points out, “Heka is the power by which the spiritual becomes manifest, for he is the connecting link between the Godhead, Atum, and all that comes from Atum.”29 Heka is thus the divine creative power that exists in both the spiritual and material worlds and is the means through which these spiritual and material levels of existence connect with each other. In this way it appears the powers of union that in our time have been reserved for what is called “religion” (a word that originally meant to “link” or to “bind together”) are in these texts clearly associated with the magic that, ironically, for at least three hundred years since the end of the Spanish Inquisition has been denied a place in the Christian West.

The special forces of magic, personified as Heka, and of cosmic unity, truth, and justice, personified by Maat, jointly enable us to understand new and unfamiliar characteristics that seem to be necessary at the levels of existence. Certain myths—such as those involving Enlil and Enki, Adam and Ashah, Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Osiris and Isis—show us that achieving the right level of awareness allows for the necessary reconciliation of opposites that is critical to awakening higher consciousness.

The Need to Awaken to the Larger View of Reality

Our introduction points out that consciousness is the foundation on which humankind tries to build a case for having a unique and special place among the creatures of the earth. Consciousness enables us to observe various impulses of energy within us as drives toward intended ends. We are able to see the desires of our animal instincts. At the same time, we see aspirations toward a finer nature to which our knowledge directs us. Our ability to discern the difference between our ordinary being and our higher levels of functioning sometimes leads us to suppose that we can make objective judgments about our behavior and our perceptions. We rely on this discernment to help us discover what is real. Our hope of discovering this reality is an important beginning step in ascertaining the ultimate purpose of our lives.

We must, however, discover in this process what can enable us to perceive our personal situation in relation to any ideal. There cannot be any hope that this can come from any ordinary level of perception. We seek a new level of being, one that lies beyond our present experiences; and we have only direct experience to guide our search. We must begin by cultivating a wider point of view of our circumstances than is customary for us. It is in this process that we encounter difficulties with our ideals. What passes for conscious awareness is all too easily confused with functions that are more an expression of our illusions than our wisdom. The subjective, sometimes dreamy, sometimes anxious states in which we compare ourselves with others—What do they think of us? How do our circumstances compare with theirs? Do they appreciate how hard we work or how tired we get? Do they see how much we value them, even when our own efforts are not appreciated?—are far removed from the perspective that is afforded by our rare insights and limited direct experiences of our personal situation. We do not require great knowledge to appreciate that speculation, anxiety, and daydreaming contribute nothing to our stature as human beings.

Direct experience is when we are consciously aware of ourselves in the things we see and do. We have seen it in the echoes of direct experience that speak to us out of the great works of art and literature of past or present ages. Direct experience enables us to verify the reality of our search and speaks to us of the essential unity of humans throughout the ages. It enables us to understand that the expressions of the finer spirits have always been the same. It is the real basis for understanding one another, and for hoping to understand together what we know as wisdom. In this sense myths are among the great works of art. Myths guide us toward understanding insights that come from our direct experience but that would be almost impossible to evaluate without them. The mysterious and unknown authors of the myths have understood what stands in the way of the free exchange of energies on which our real growth and development depend. Because of this, they lead us to appreciate our need to be awakened to a different, more immediate level of perception.

For this reason it seems important to acknowledge that an element of tragedy is expressed in all these myths. Adam’s attempts to find knowledge taught him of death and led to his “banishment” from Eden. Gilgamesh’s feats of daring led to the death of his dearest and closest friend, and his profound suffering led to his subsequent search for immortality and the eventual denial of everything he had sought. In Egypt, the creation of a marvelous civilization by Osiris and Isis led to the murder and dismemberment of Osiris, and only after many more struggles did his resurrection take place in the land of the everlasting.

Are personal tribulation and pain, as is implied in the myths, essential parts of gaining wisdom? Life experiences that have given us a taste of what we consider the nature of our higher consciousness have left quite a different impression: brief but vivid feelings of well-being on a sunny spring day; a breath of fresh air from the sea; sudden pleasure when one bites into a sweet and juicy orange. These are moments of enlivenment that most of us have known in one form or another and that we value.

It is true that we have also experienced the opposite. At times it is difficult to imagine being genuinely free of the limitations, tensions, and anxieties in life. We have little desire to remember moments of empty loneliness or of being drained of all vitality following an emotional upheaval. We are not naive enough to suppose that a taste of the higher consciousness is found only in moments of ecstasy. We know enough about tragedy to understand its dramatic value in works of literature. But is this a necessary part of the process of discovering wisdom?

Final Comments

What seems most evident from life experiences is that at any one time our viewpoint is relatively narrow. Our sense of balance spans only small dimensions and short durations. When we identify with moments of pleasure, we avoid glimpses of a lack of worth or sensitivity. In moments of depression, we may feel that real happiness never existed. Dismal “adult” emotions may compare unfavorably with what we remember encountering as children, with a child’s natural flexibility and depth of feeling. The child and the adult both experience pleasure and pain, but where the child may bounce emotionally from low to high, the adult becomes trapped in a tangle of memories where sadness becomes enmeshed in self-pity and anguish keeps company with anger.

Awakening to the imbalances of our world provides a new standpoint from which to view oneself. But it is necessarily an awakening to the facts of separations and compartmentalizations, the partiality of our usual views of existence. Whether happy or sad, these small views are surely tragic in relation to the vast potential of life. Before people who would be wise can present themselves at the doors of the wise individual, they must awaken to the reality of their partiality. The primary purpose of the myths is to urge us to awaken. The wonder is that they seem to be so difficult to hear.

The myths also speak of the need for struggle. We are familiar with the Christian idea of struggle against evil. However, all the myths emphasize a special aspect of evil for humankind. They repeatedly point out that the real evil for us is isolation and the separation of parts. Using symbolism, they also show that under the ordinary circumstances of life the desire for individuality leads to isolation. When one’s desire becomes the opposite of what is needed to achieve wholeness, transformation is blocked. Isolation leads to enmity and division, while integration leads to positive relationships and wholeness. The struggle in life is the work of embracing and reconciling opposites: love-hate, joy-sadness, hope-despair, and so forth.

The Egyptian story of the struggle between Horus and Seth is of particular importance in this regard. This struggle between gods seems on a different scale than those of Gilgamesh in the Land of the Living or Adam in the Garden of Eden. There is no hint of the bravado of Gilgamesh or the naïveté of Adam in this celestial struggle. In fact, the symbolism implies that in this battle even a temporary victory could not be sustained without the cooperation of Isis. Our attention is rightly attracted to the drama of the struggle in which the forces of entropy and decay continually beset Horus. But the gods cannot destroy one another. They can only restrain with the help of the guardian Isis. A unique feature of this battle is that it never comes to an end. There is no final resolution. At one point the gods simply agree that other matters need attention.

This provides an interesting insight into the dynamism that activates our internal and external worlds. In this struggle among gods we are obliquely shown that the need is not for the conquest of one side by the other; there is always the continuous engagement in desperate struggle. Rather, there is a requirement for resolution of opposites only possible through alertness to the whole. This attention alone can prevent us from being overwhelmed by the forces of partiality and strife that separate us from the obligatory interdependencies of life.

So here at the end of our exploration, we hope that readers will see these myths in a new light that will contribute to their explorations of themselves and of the world around them—to help them find and establish a stronger Self within themselves. Throughout this book, the myths have been shown to address profound questions concerning the nature of reality. The creation myths we have uncovered can be viewed as creation of the external world only by literalists living in naïveté. Do we recognize our inability to discriminate between our reactions to external stimuli, as opposed to internal feelings? Do we know how to distinguish the Egyptian concepts of the Everlasting from the Eternal? Plato brings up a serious question about the nature of life and death in the Gorgias dialogue when he quotes Euripides’ famous inquiry: “Who knows if life be death, and if death be life?”30

The Sumerian and Egyptian myths directly influenced the Judaic culture and formed the basis of some Old Testament stories, which, in turn, influenced present-day Western culture. That is, we in the West can trace our cultural roots directly to myths written down some 4,500 years ago! But the challenges modern societies face lie in understanding what these myths are telling us and determining how we can make use of them in our everyday life to awaken our higher consciousness.