chapter 3

How to Stop Dodging Discomfort

In this chapter, we’ll explore how to combat discomfort-dodging procrastination by taking a fantasy excursion to Amphibian Way and see how certain regions of your brain can stir procrastination urges and what you can do about it. This is the first of several stories, myths, and fables on specific self-mastery skills to help you recognize and correct procrastination patterns. Put yourself into the story. See if you can make the concepts work for you.

The Amphibian Way: Procrastination by Default

Tomorrow’s test, a confusing math problem, an upcoming class presentation—all can feel emotionally uncomfortable. The next thing you know you are checking Facebook or tweeting—doing almost anything but hitting the books to do the assignment. By examining what is happening, you can gain clarity and use this knowledge to overcome a procrastination pattern.

Let’s take a fantasy journey to powerful earlier regions of your brain that evolved from our amphibian ancestors. There you meet a frog. You introduce yourself and ask for the frog’s take on procrastination—you’ve heard he’s a pro. Frog is friendly, cooperative, and quick to respond: “You must be the person who lives in the executive suite. I’m glad you stopped by. I’m happy to share what I know—I’m kind of an expert, you know.” (The executive suite is your “new brain,” or prefrontal cortex. This is where your executive abilities—those for reasoning, analyzing, planning, organizing, predicting, judging, and adjusting—reside.)

Frog goes on: “Procrastination is about reactions. You feel a negative sensation when you have something to do that you feel uncomfortable doing. It doesn’t take much to kick-start escaping from this tension. A whisper of negative affect will do. You can think of this as jumping for cover. It’s as simple as that.”

You realize that a reactive frog lacks foresight. You think to yourself, Jumping for cover won’t work when an assignment is due.

It’s Jack’s problem too, and he’s struggling with it. When he has something tedious or uncomfortable to do, Jack, like Frog, jumps away. For example, he loves playing beautiful music, but not as much as he prefers to avoid uncomfortable practice sessions. So, when the time came to practice, he jumped to the refrigerator and snacked. Then he jumped to the mall to see if there was anything new to see. If you asked why, Jack would say, “I don’t know. It’s something that comes over me.”

Jack’s is a case of simple default procrastination: he feels uncomfortable, so he does something different. This reaction may not be fully under Jack’s control. The amygdala, an almond-shaped region of his brain, appears to be part of the brain circuitry of procrastination. The amygdala contains a parallel set of neurons (nerve cells that transmit nerve impulses) that carry information about pleasant and unpleasant events and assign positive and negative emotions to the events.

Let’s say that you feel uncomfortable about a school assignment and feel positive about a diversion. Here is a theory that can explain what is happening: You get a temporary (specious) double reward by avoiding doing something unpleasant and doing something pleasant instead. Positive and negative amygdala signals intermingle and kick-start the opening phases of default procrastination.

Both Jack and you can blame the amygdala for default procrastination. But that won’t solve the problem. You do have the choice of accepting discomfort and acting productively. Let’s turn to using your executive resources to address this natural and temporary amphibian reaction.

PURRRRS: A Tool for Short-Circuiting Procrastination

PURRRRS is an executive tool for slowing down, figuring things out, and acting reflectively and effectively. Let’s start with the meaning of the acronym:

- Pause. When you have an urge to jump, stop and tune in to what’s happening.

- Use your resources. Find enough personal resources to resist the impulse to get sidetracked, and slow down enough to make a real choice.

- Reflect. Ask yourself: What’s happening? Who’s in charge? Is it your executive, or is it Frog?

- Reason. Ask yourself: What do you gain by delaying? What do you lose? Take a language-of-change approach, such as, “I’ll walk back to my desk. I’ll sit down and open the book.”

- Respond. Implement each step of your language-of-change plan. If necessary, push yourself to start.

- Review and revise. You can improve on most plans. Review what you’ve learned and devise ways to improve your plan and your follow-through efforts.

- Stabilize. Keep practicing and improving until PURRRRS is automatic in situations where this method applies—that is, when your frog wants you to leap away when it is wise to persist.

Here’s Jack’s PURRRRS program, which he uses to help himself practice music.

It’s your turn to try a PURRRRS experiment and see what you can do for yourself.

Controlling Distractions

Distractions are part of life. You hear your cell phone ring. You see a bird in flight. As your attention switches from one thing to another, you engage different regions of your brain. Each switch takes a brief time for the brain to adjust. These changes take place beneath your level of awareness. This switching process is a normal part of daily life, too. However, switching can be a hindrance when you are trying to learn a complex subject and need to concentrate.

When you are doing a homework assignment, your flexible brain keeps adapting as you switch tasks. For example, you start studying physics. You pause to play a computer game. You start calculating. A friend calls. You go back to calculating. It takes time and energy for different brain regions to adjust when you switch tasks. Thus, when it comes to doing a hard assignment, you’ll lose some efficiency by retracing some of your steps each time you switch tasks.

Switching between tasks also interferes with working memory. This memory is similar to random access memory (RAM) on a computer or SMS on a mobile phone. If you switch off the device, you lose the data. For example, if you get a phone call when memorizing a list, you are likely to retrace some of the steps that you have already taken after you finish the call. To save time and effort, you can avoid a switching effect by avoiding the distractions.

When you look to your future as a college student, here is something to consider about technical distractions: College students fall into the task-switching trap when listening to lectures while using technical devices. Most believe that they can multitask efficiently. Brain-scan research suggests that this belief is an illusion. They lose efficiency and are more likely to miss points and not do as well as others who don’t distract themselves in this way.

You can’t control what your brain does when you switch between tasks. However, you can reduce factors in your environment that create switching effects while you are studying. When you have a subject to study that takes a lot of concentration, you can minimize these distractions by putting yourself in a place where you can concentrate without interruptions.

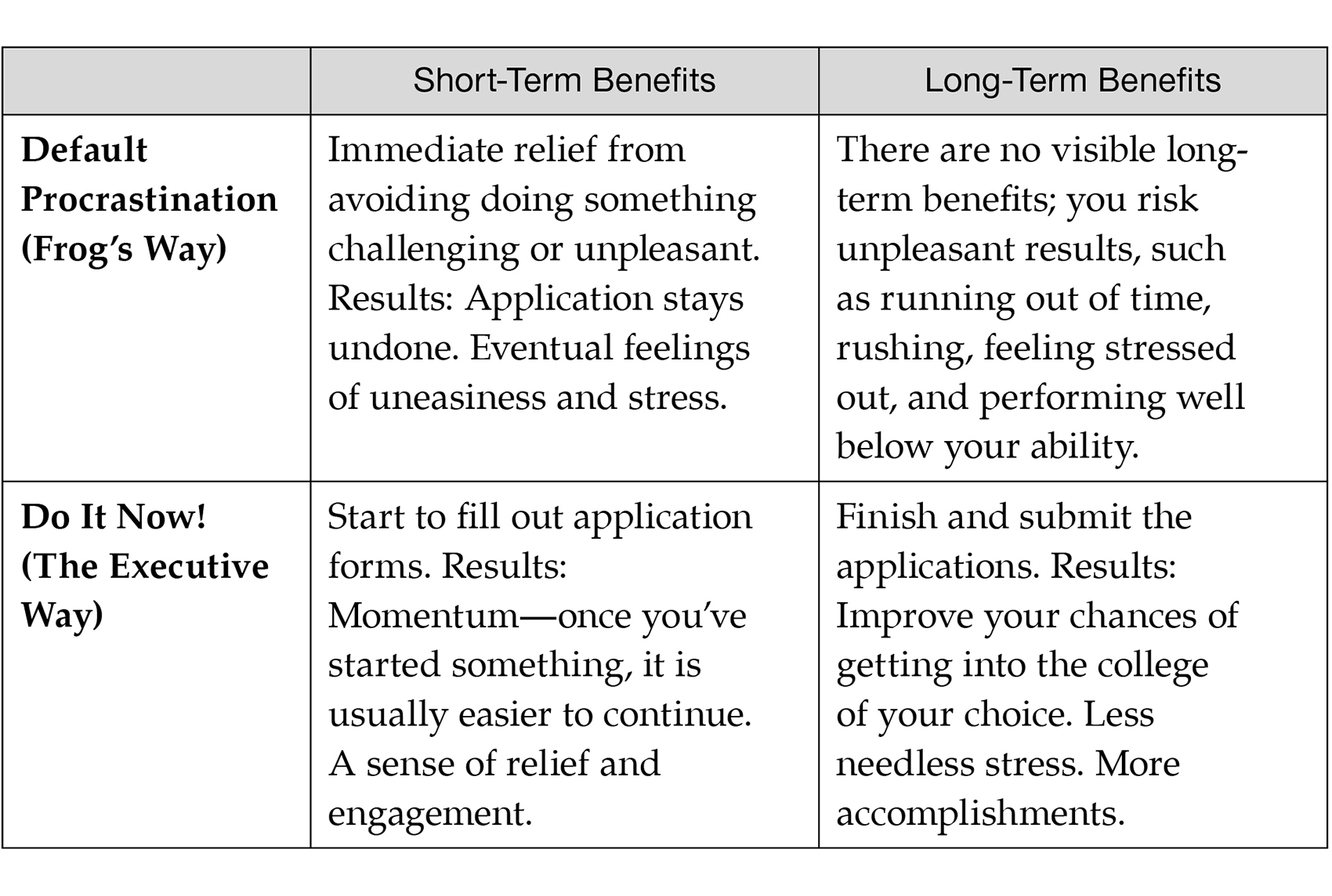

Benefit Analysis: A Tool for Choosing Action over Procrastination

When it comes to overriding urges to procrastinate, perspective helps. A short- and long-term benefits analysis can help you avoid caving into procrastination urges. Let’s use completing college applications as an example for comparing Frog’s way and the do-it-now way.

It is your turn to experiment with your short- and long-term benefits analysis:

When you compare short- and long-term benefits of default procrastination against do-it-now actions, what do you conclude? For example, when you delay feeling uncomfortable, you are likely to feel worse and rushed later. You lose touch with what you are capable of doing.

Write your conclusions below.

Now that you know how Frog works and what to watch for, you are in position to use your self-monitoring ability to track what is going on and to assert control over Frog urges when you need to.