chapter 5

Getting Beyond Procrastination Obstacles

In this chapter, we’ll look at how to strengthen three important self-mastery skills: preparing for success, following through without stopping mid-stream, and not letting test anxiety get the best of you. You’ll meet three teens who met these challenges.

Setting the Groundwork for Success

In Aesop’s fable The Grasshopper and the Ants, a grasshopper sang, danced, and fiddled the summer away. Meanwhile a colony of ants prepared for the winter. The summer ended. When the northern winds blew, a desperate grasshopper came to the ants for help.

Procrastination on preparation is as common today as when Aesop wrote this fable. This is putting off laying the groundwork for success. However, there is more. In academic settings, procrastination on preparation can have a double-whammy effect: (1) you fall behind when you don’t prepare; (2) you risk a performance problem because you are not prepared. To turn things around, do what elite performers do to prepare themselves mentally and technically for performing at peak levels. Here are three mental preparations for achieving excellence:

- Failure proofing. Errors and mistakes are necessary bumps on a long path to excelling. Elite performers focus on correcting, improving, playing through mistakes, and bouncing back smoothly. An elite athlete or musician anticipates doing well and behaves according to that belief. Consider the alternative. If you believe that you are fated to fail, you are likely to put things off or make half-hearted efforts. You might also pressure yourself to act to avoid failing. You are more likely to choke under this kind of pressure.

- Mental rehearsal. The most proficient surgeons practice mentally before they start working. On average, they perform better and make fewer errors. Musicians and athletes who mentally rehearse typically do better than those who don’t or won’t. Consider the alternative. You wait and hope for the best. That rarely turns out well.

- Pace training. It takes time and practice for your brain to develop mental networks for complex new learnings. Rushing a process that takes time is like throwing tomato soup into a microwave and expecting to take out excellent spaghetti sauce. By getting more precise on pacing, you develop the skill of estimating how long it takes to do most things, and then test your time estimate against your performance.

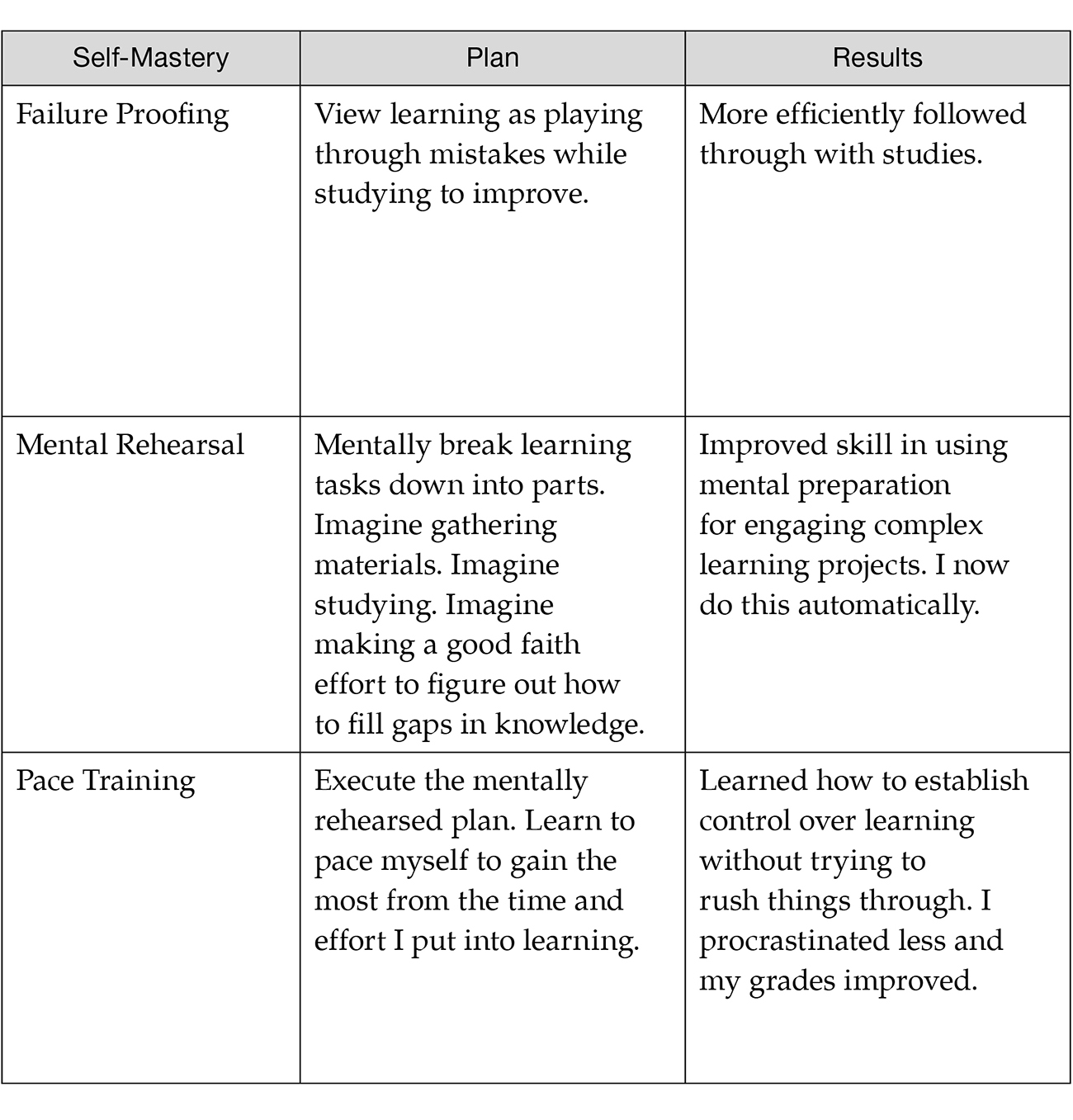

Let’s look at how Ethan developed an elite-performer self-mastery skill. Throughout middle school, Ethan did as little as he could. In his first year of high school, the work was more demanding. He was unprepared for that. He started getting low grades. That was enough to cause him to think seriously about turning things around and doing better with his studies. Here is Ethan’s self-mastery plan and the results from his six-week mental preparation experiment.

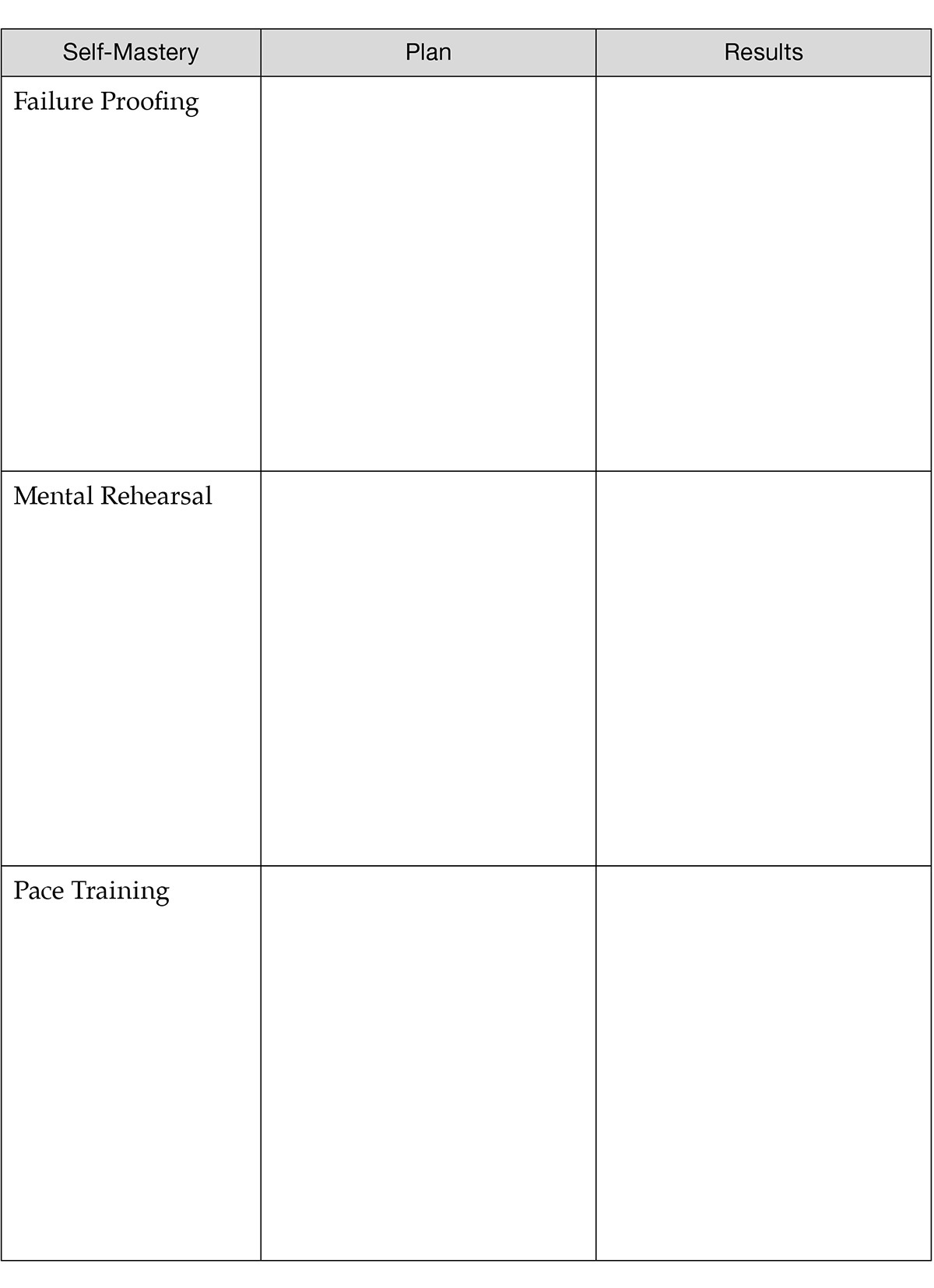

If you too would like to strengthen your preparation skills, here is a framework for your experiment in preparation.

Following Through Without Stopping Midstream

Behavioral procrastination is starting something that benefits you and then quitting before you finish. For example, you prepare for doing an assignment. You start working on the assignment. You stop midstream.

Olivia was painfully aware of behavioral procrastination. For example, items that she purchased for hobbies remained in their packaging. A tall pile of novels she bought to read gathered dust in the corner of her room. After she wrote her to-do lists, she put them aside and didn’t use them.

Olivia followed the same pattern with her studies. She started strong then faded fast. Unlike the hobbies she hoped to do someday, she had deadlines to meet for her studies.

Olivia reviewed what happened when she started, stopped, and then rushed to finish a history essay on King George III and the American Revolution. She recalled that she set a time for studying. She started on time. She checked Internet resources. She read the assigned chapter in the text. While the information was fresh in her mind, she sidetracked herself by checking her smartphone and texting her friends. In fact, she distracted herself so much that she lost track of the distractions.

Olivia was comfortable with preparing herself to do most assignments. However, when it came to writing assignments, she started strong by gathering materials and procrastinated when the time came for writing.

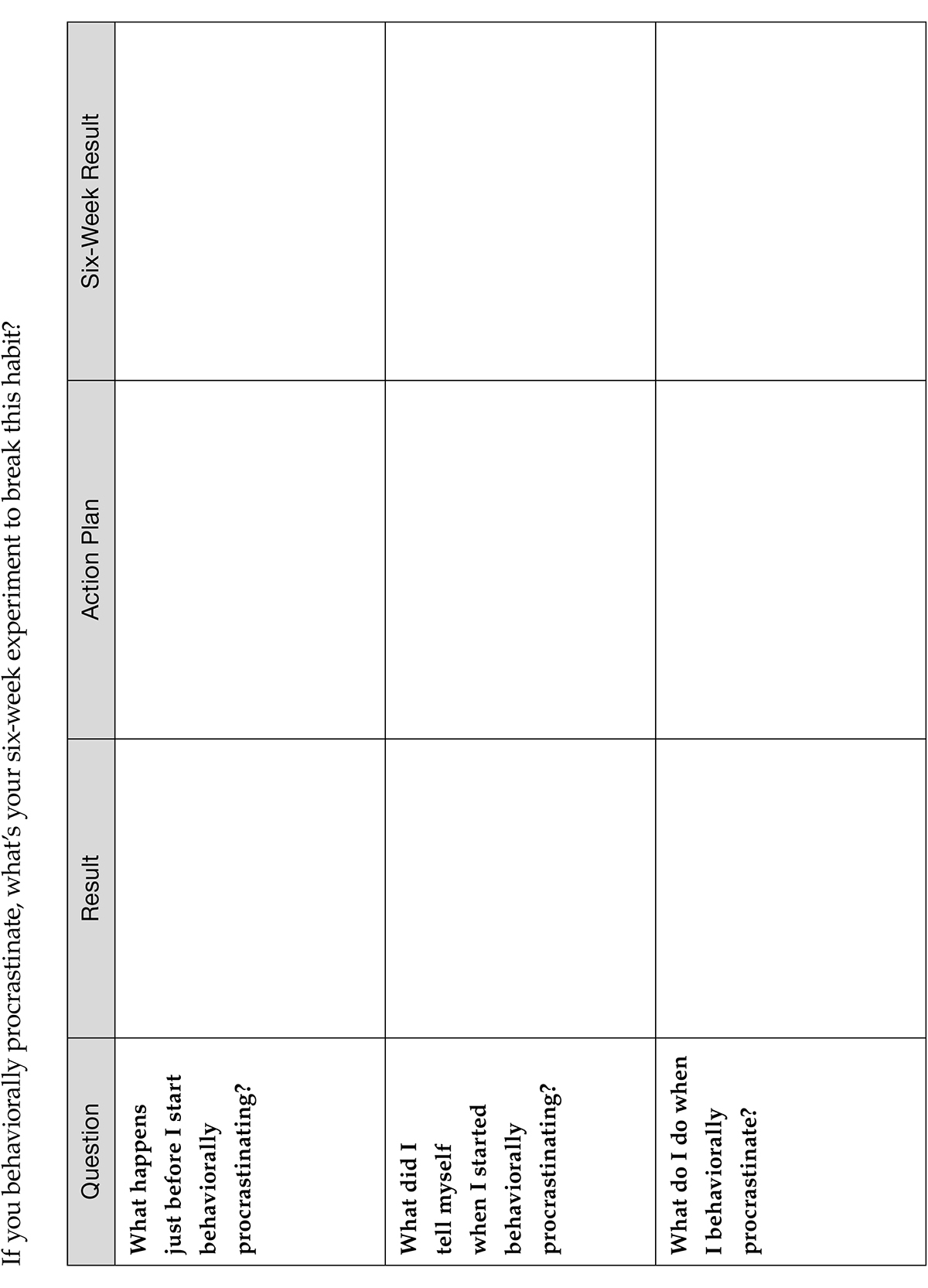

Olivia found a description of behavioral procrastination in an old book titled Do It Now: How to Stop Procrastinating. Wow, she thought, this sounds like me. She thought about what she read and then asked herself three questions about when she stopped midstream. That effort paid off. The following shows the questions and the steps she took to break her behavioral procrastination cycles.

Don’t Let Test Anxiety Get the Best of You

Test anxiety is common among high school and college students. Mild or moderate test anxiety will probably not affect a test score, providing you don’t procrastinate on studying. High anxiety may not affect the results if the test is easy. However, excess worry and distress might spur procrastinating, and this can result in a lower grade, especially for tests where preparation takes concentration.

Test anxiety is about the future. You feel vulnerable and threatened now because you don’t think you will be able to cope effectively later. The most direct way to overcome test anxiety is to practice taking tests until they become routine. However, what do you do when you are stuck on procrastination’s web along the way?

Luis’s chemistry midterm was coming up in a week. He worried that he couldn’t understand the subject well enough to pass the test. He worried about failing. He dreaded feeling anxious and spacing out during the test. He dreaded that his anxiety would wreck his performance. To escape anxiety, he procrastinated by playing Sim City. Then he sketched motorcycles on his artist’s pad. He wanted to wait to feel relaxed before studying. This was an example of test anxiety that interfered with preparation. It was also an example of procrastination on learning ways to cope with text anxiety.

Since Luis’s test anxiety was about a future chemistry test, he had time to figure out how to cope effectively. He got some help from his friend Lloyd, who suggested that Luis gather information about procrastinating. He heard that combination procrastination was very common (procrastinating in different ways and for different reasons to avoid the same thing).

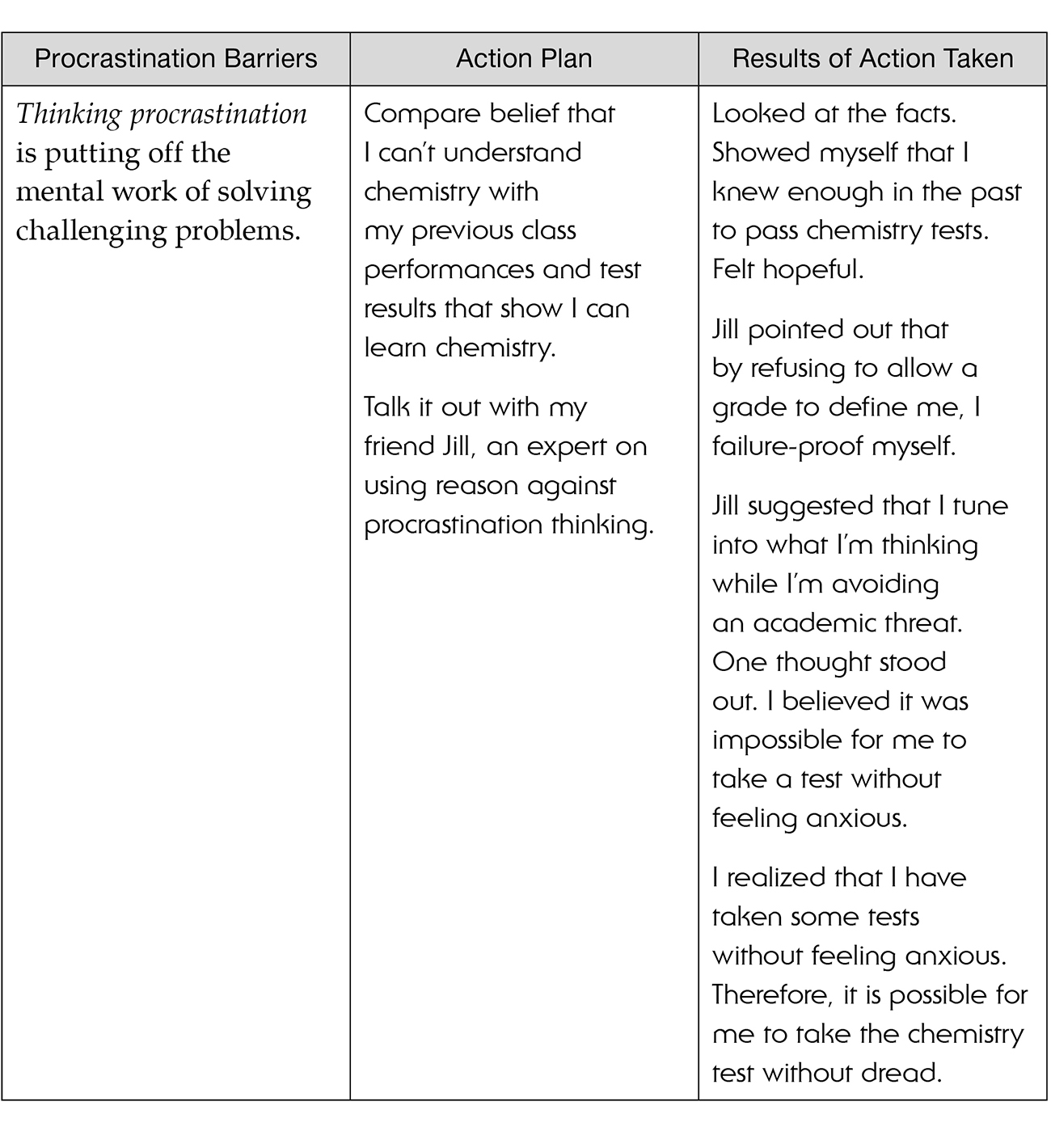

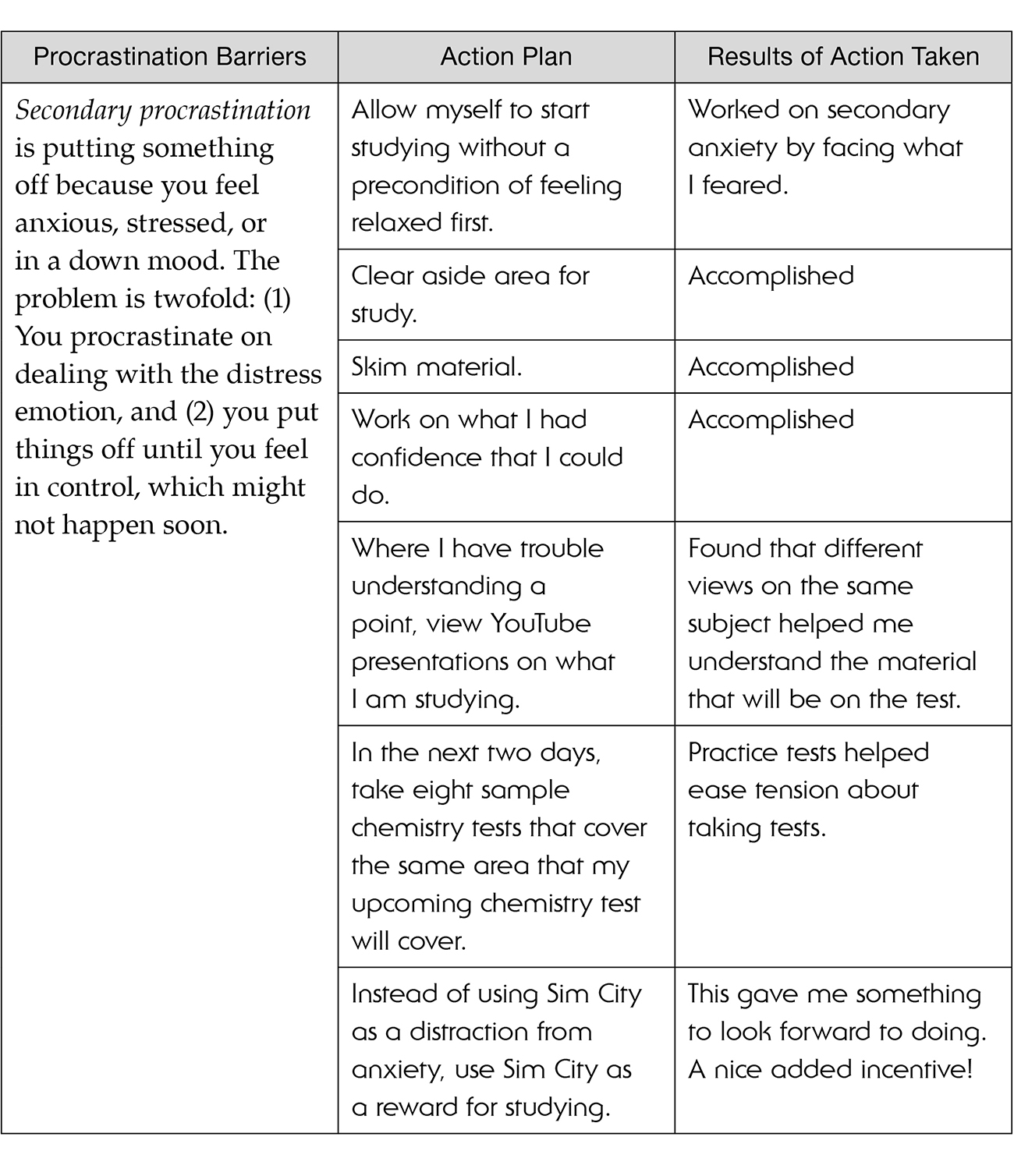

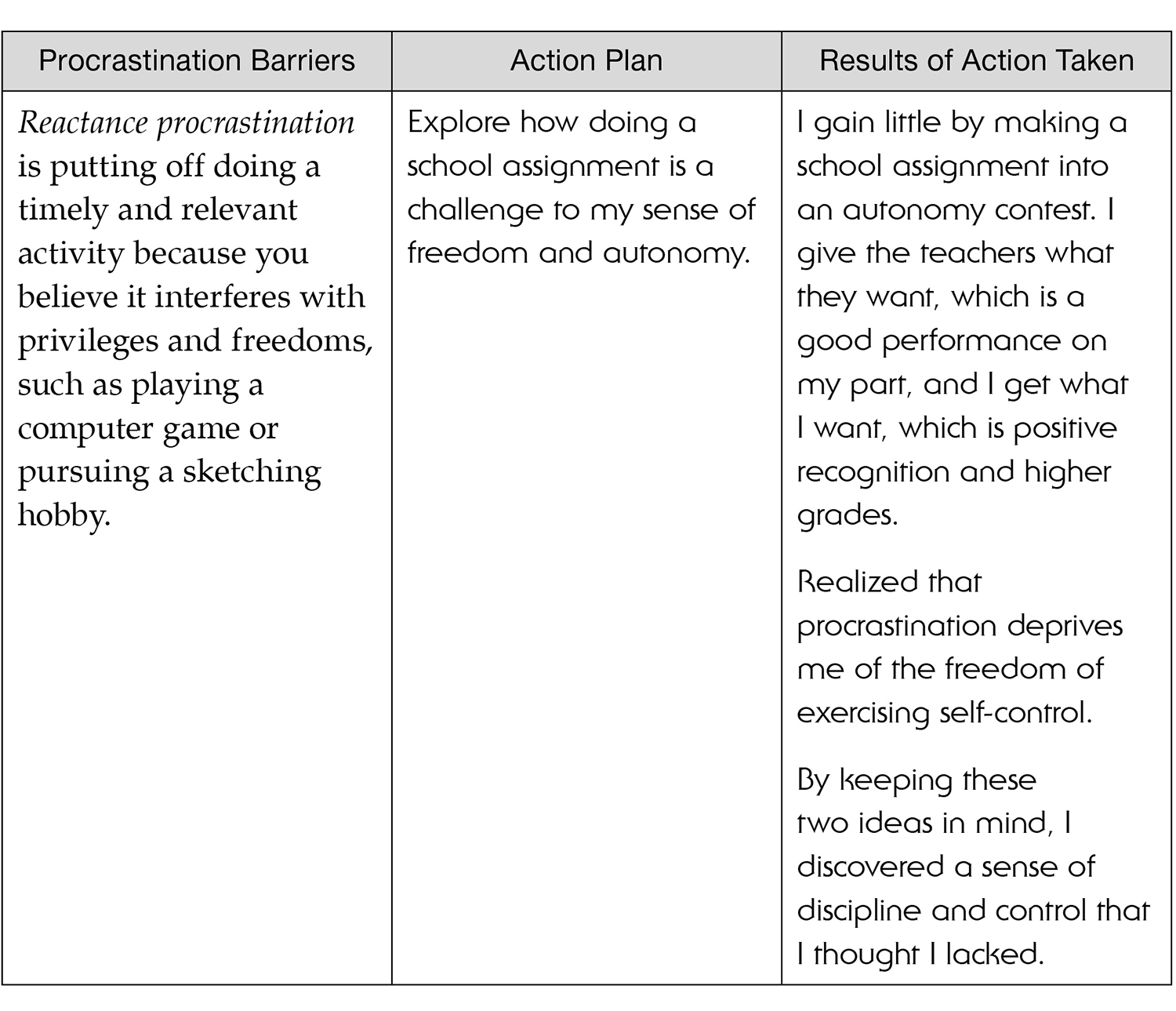

Luis thought about what Lloyd said about the different forms that procrastination takes. He then read several Psychology Today blogs on procrastination authored by Bill Knaus, EdD. That helped him pin down three procrastination obstacles that fit with his experiences: thinking procrastination, secondary procrastination, and reactance procrastination. Here is what Luis did to stop procrastinating on overcoming his chemistry test anxiety.

When you are anxious about a performance (such as a test, playing a sport, singing before a group), and if Luis’s solution resonates with you, consider combatting thinking procrastination, secondary procrastination, reactance procrastination, or whatever other form of procrastination that gets you stuck on procrastination’s web. Here is a framework for you to deal with your combination of procrastination challenges, such as default procrastination, deadline procrastination, or any other types of procrastination that interfere with positive learning goals.