chapter 9

Simplifying Your Decisions

Torn between a temptation and a loss, Michael couldn’t decide what to do. He explained, “I felt stuck.” Here was Michael’s dilemma: He was attracted to Alice, a new girl in school. However, he was going out with Sophie, whom he had known since elementary school. He couldn’t make up his mind. Should he ask Alice to go out with him? Should he break up with Sophie? What if he broke up with Sophie and Alice wouldn’t go out with him?

Sophie knew Michael well enough to know that he was distancing himself from her. She dropped him. Before Michael introduced himself to her, Alice started dating someone else.

Michael made many minor decisions without hesitation. However, for major life decisions, he was often indecisive to the point of emotional paralysis. For example, he had trouble deciding whether to apply for an early admission decision to a college that interested him. He knew that early admission decisions were binding. He had no guarantee that he’d make the right choice. He procrastinated. Here’s Michael’s reason: “I’m afraid I’ll make a mistake. What if I found out that I could have gotten into a better college?” Michael “decided” the early decision dilemma by delaying past the deadline.

Michael is not unique. From time to time, practically everyone hesitates too long on deciding some big and small matters: to hang out with friends or to study, to say what you think or stay silent, to take an SAT study course or not, or to go with “X” to the prom or with someone else.

Michael burdens himself with decision-making procrastination, which means he puts off making decisions until another day or time. He waits until the last minute to make a decision, decides too late, or waits until someone makes the decision for him.

In this chapter, we’ll look at the role of emotions in decision making using a horse-and-rider metaphor to explore why people procrastinate on decision making and how to build decisiveness skills.

Emotions in Decision Making: The Horse and the Rider

Most dictionaries define the word “decision” as a process where you make a choice between two or more conditions after thinking it out. However, when you put off making decisions, why do you stop yourself from reasoning things out?

Decision-making procrastination has an emotional component that is connected to many thoughts and feelings, from worrying about failing to an aversion for uncertainty. Say you have a class presentation to make. You are afraid that if your presentation doesn’t go well, your peers will judge you harshly. You feel tense every time you think of your presentation. To avoid thinking about it, you avoid preparing for it. You’re so unprepared and anxious that you decide to skip school on the day of the talk. Ultimately, you based a series of procrastination decisions on avoiding anxiety from uncertainty, and this has led to a larger problem (the result of skipping school).

Some tough choices include unknowns. Under conditions of uncertainty, you’ll sometimes make errors. If you think you need a guarantee that your decision will be right before you act, you might avoid a decision for as long as you can. Perhaps you’ll make an impulsive decision to escape the tension of indecision. As you master decision-making skills, you can learn to accept uncertainty as you improve the timeliness and quality of your decisions. You can grow wise as you learn to make reasoned decisions.

How do you choose reason over impulse when decision-making procrastination seems to come naturally? If you’ve read novelist Rick Riordan’s story Percy Jackson and the Olympians, or if you saw the movie, you met Chiron, a centaur—a being who is half-horse and half-human and who represents the very best of our animal and human natures. Chiron is a nurturing, patient, wise teacher with the ability to impart wisdom and encourage self-discovery. Perhaps Chiron has an answer.

The founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, drew from the myth of the centaur to create a metaphor of a horse and rider. He did this to show the ongoing conflict between impulse and reason and how the conflict might be resolved. Let’s start with the horse’s perspective.

The horse is a creature of the moment with its own priorities. When it feels like it, the horse heads for the field to graze, the stream to drink, and the barn to sleep. It frolics. It runs with the other horses. When panicked, it bolts. The horse lives in the here and now and is not concerned with longer-term interests.

Your horse represents your passions, emotions, and impulses. The horse takes the path of least resistance. When the horse is in charge, you’ll party rather than study for tomorrow’s quiz.

Your rider is the executive of your destiny. Endowed with the powers of thought and perspective, your rider (a resident of the executive suite; see chapter 3) can transcend the boundaries set by the horse. However, your rider does not enter this world with all necessary worldly knowledge. At all stages of life, there is more to learn. For example, when you feel uncertain and confused, sorting things out is your rider’s job.

Your rider has the power to accept responsibilities, act in an organized way, and work to achieve personal benefits and advantages. Your rider has the capacity to do things for the good of others. Among the rider’s tools, you’ll find the power of foresight, which allows you to look beyond the moment to see what is in your long-term interest to do. That’s something that neither the horse nor the frog you met in chapter 3 can do. Faced with an upcoming test, an enlightened rider will take ample time to study.

When Horse and Rider Are in Conflict

Like Chiron, who balances the best of human and animal natures, the horse and rider will often work together. However, conflicts are inevitable. Your mind will sometimes tell you to do one thing as your emotions pull you in a different direction.

When you have something to do that is uncomfortable, your horse is inclined to make automatic procrastination decisions. These decisions can start with a negative perception of a task, negative feelings, and an urge to diverge into safer, easier, or more comfortable areas. Even a slight negative feeling can startle the horse into setting a procrastination process into motion. Unfortunately, the rider may be swayed by horse impulses and support them with a negative evaluation of the situation that spurs a procrastination outcome.

A double-agenda dilemma surfaces when the horse and rider pull in opposite directions. You have frustrating assignments to do. You have an urge to follow a procrastination path. At the same time, you want to achieve and succeed. You face a Y choice. The letter Y has two branches, much like a branch in a road. You can pause and ponder a direction, and go one way or the other, but you can’t go in both directions at the same time.

Y decisions are a daily part of life. You have a math assignment, and you are not sure how to go about solving the problems. Your rider’s goal is to do well on the assignment to get a better grade. Your horse has a different agenda, which is to avoid uncertainty and avoid feeling uncomfortable. This is your Y choice, and how you decide the issue predicts what happens next. Let’s see how the rider and horse make choices when each works against the other.

Here is a rider’s view of the Y choice: choose the most productive action even if it is uncomfortable, realizing that the discomfort will pass and solving the problem is more important than the initial discomfort. (Learning to bear discomfort, while striving to do better, is a sign of maturity. It’s also a measure of resilience, or the ability to withstand adversity.)

Here is the horse’s view of the Y choice: instead of thinking things through, you want to put this off because you want to avoid stirring up unpleasant emotions. Here is the horse’s solution: take the path of least resistance, which is to put it off as long as you can. Meanwhile, the horse heads for the barn to eat hay.

Horse-and-rider conflicts are inevitable. Sometimes it is important for the rider to have a good grip on the reigns. The ordering-of-choice method can help.

The Ordering-of-Choice Method

When you know you are going to be pressed for time and it is important for you to stay focused, try an ordering-of-choices method.

Let’s suppose that you pick getting good grades to get into a good college as your top “study priority.” Your rider is interested in staying on track when you have a test, presentation, or paper to do. That’s how you’ll achieve your “good grades” objective. Your horse has a different idea: frolic, play, and avoid whatever feels uncomfortable. However, there is a time for play and a time for following through whether you feel uncomfortable or not. When you get this backward, you have a procrastination problem.

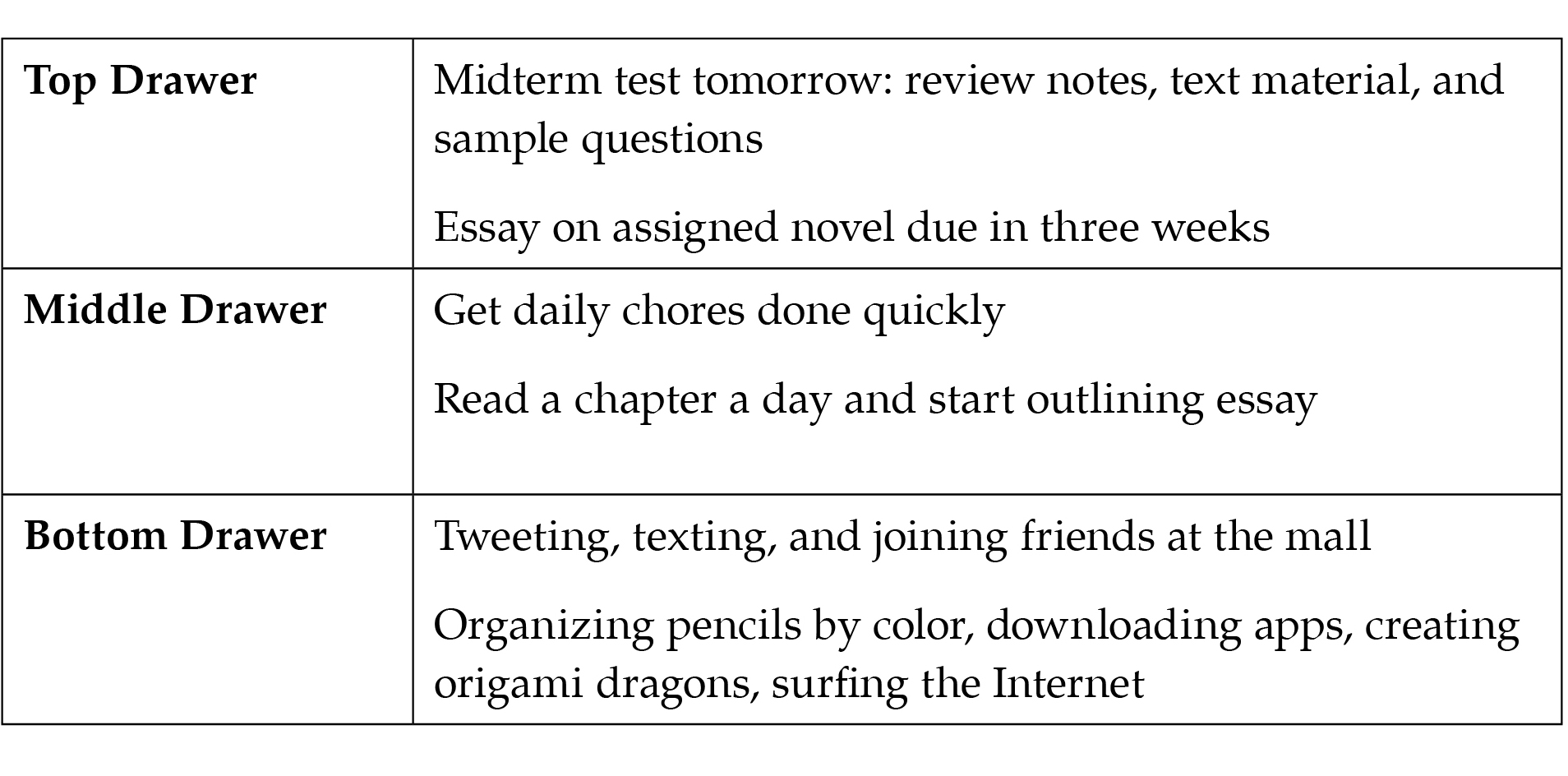

Here is how the rider can take charge. Organize your study activities into A, B, and C priorities. Priority A is a top-drawer activity, such as studying for a test scheduled for tomorrow. B, or middle-drawer, activities can wait, but not for long. Bottom-drawer activities are distractions that interfere with rational rider priorities. Here is an example:

If you elevate a middle-drawer activity above a pressing priority, it is as much of a diversion as going to an office supply store to buy paper clips when you’re running out of study time for tomorrow’s test.

The ordering-of-choices method puts your choices into a sharp perspective. You’ll know what distractions to avoid. You have a better chance of succeeding by sticking to priorities.

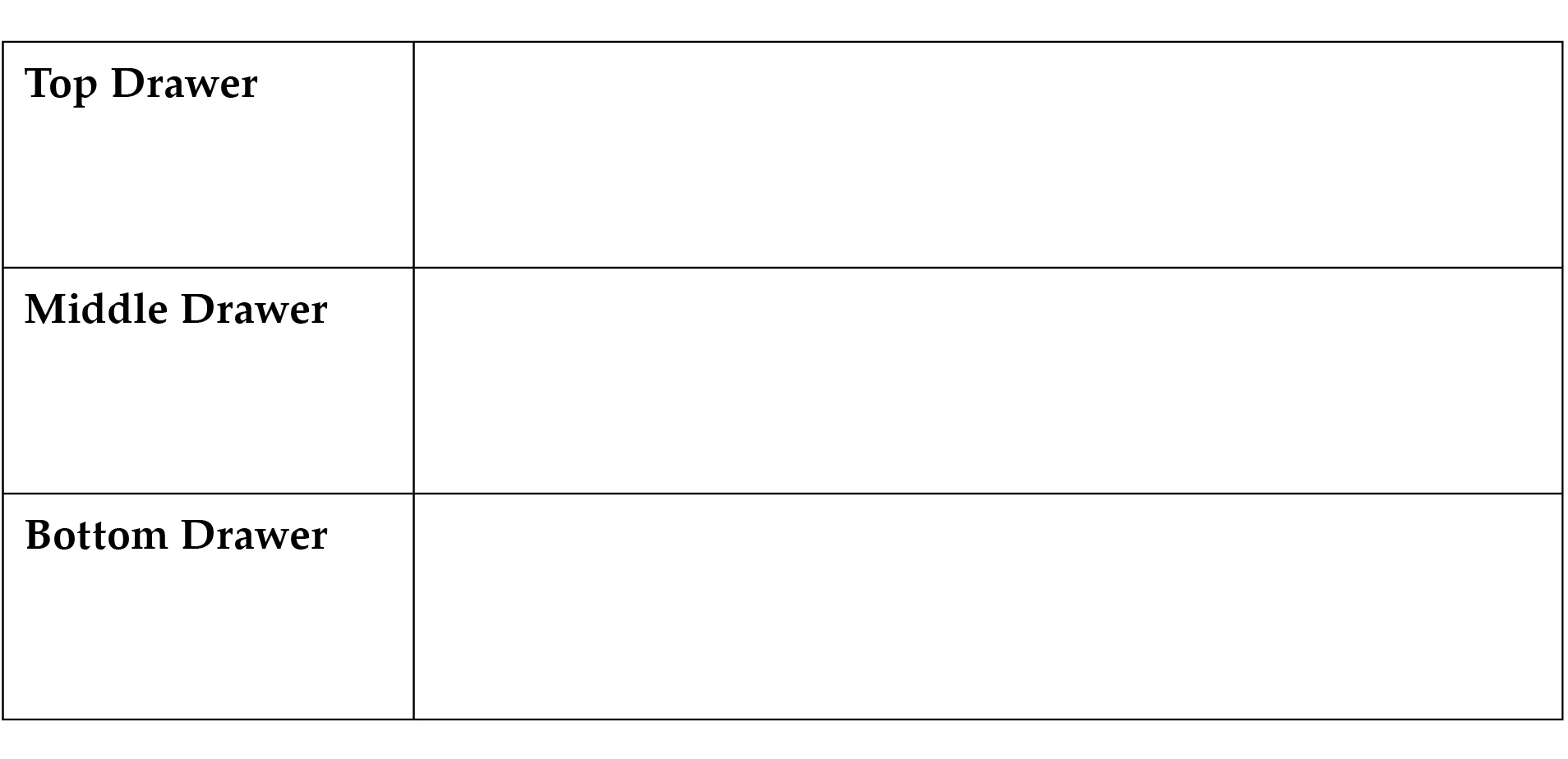

It’s your turn to target what is most pressing and important from an enlightened rider’s perspective.

As you master the method, you’ll find other ways to use this method of organizing priorities.

Practice Decision Making

Your decision-making skills may be the most important psychological tools that you have when it comes to living a happy, healthy, and productive life. Because making decisions happens so often in life, you’ll have many opportunities to refine these skills. Here are a few common horse-and-rider conflicts that give opportunities for the rider to improve decision-making skills:

- sticking to your principles or going along with peer pressure to change them

- sharing how you feel or keeping a stiff upper lip

- studying for a test that can get you the grade that you want or going to a concert

- taking a part-time job to pay for a car or increasing the amount of time studying to get top grades so you can get into a top college

You know the results of procrastination. How can you put your enlightened rider in charge to sharpen your productive abilities in the above and other similar conflict situations?

Experiment: Put Yourself in Charge

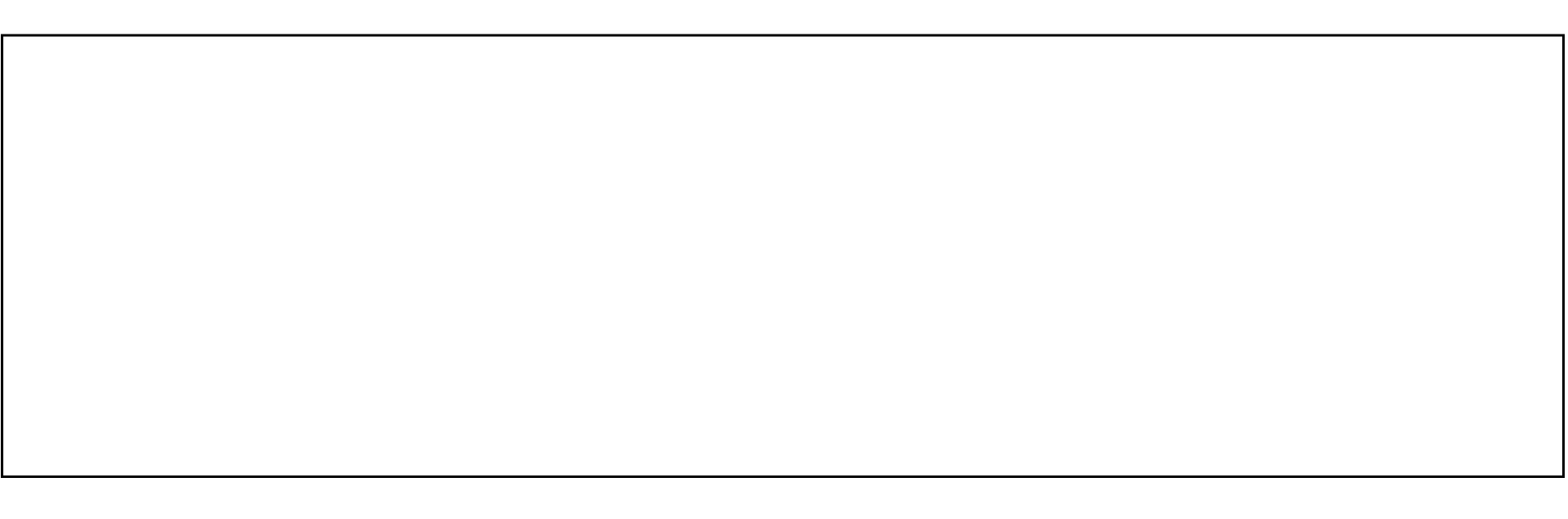

What decision is a priority for you today that you’ve put off for too long? Describe it in the box below.

Now, try the following experiment for resolving horse-and-rider conflicts.

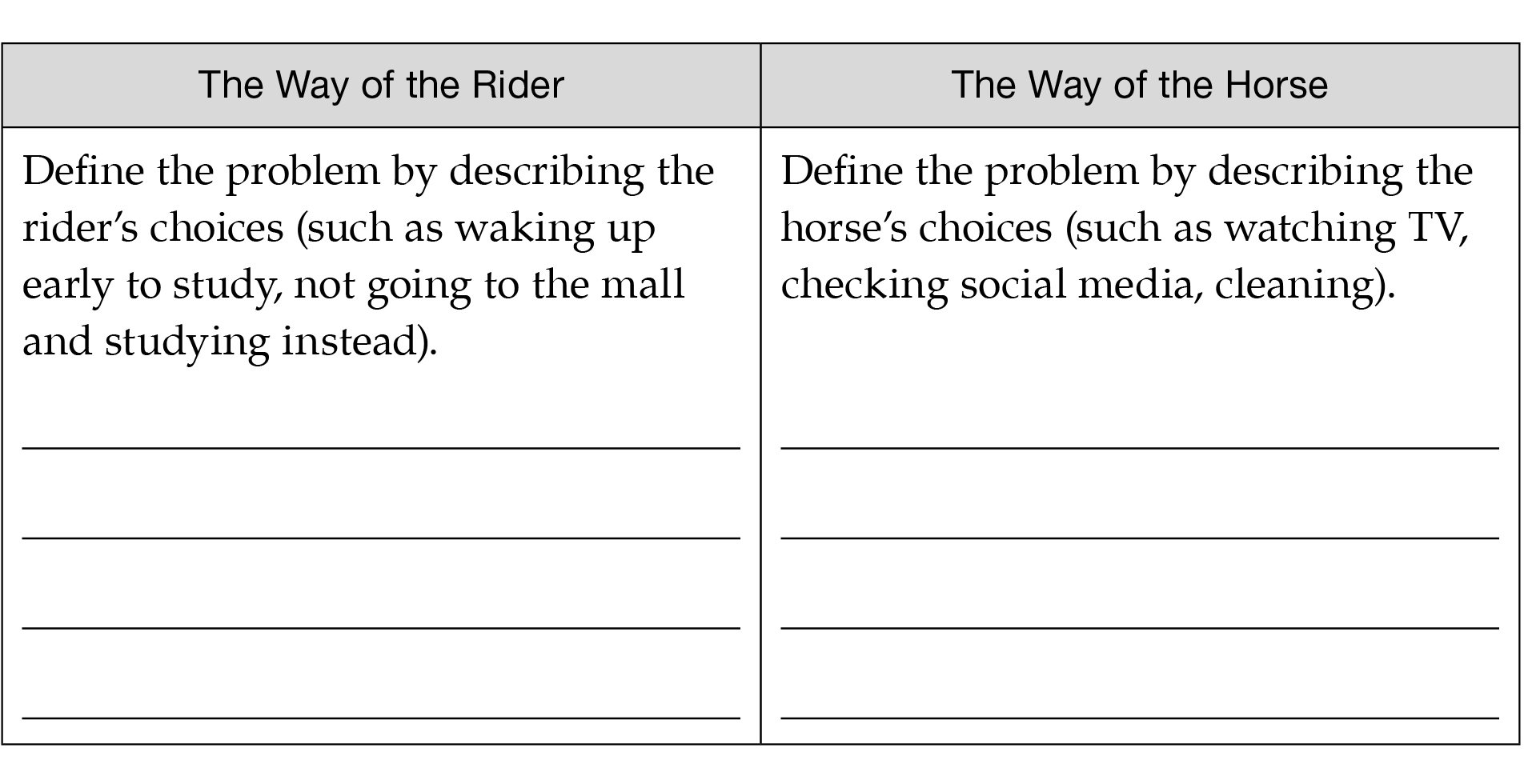

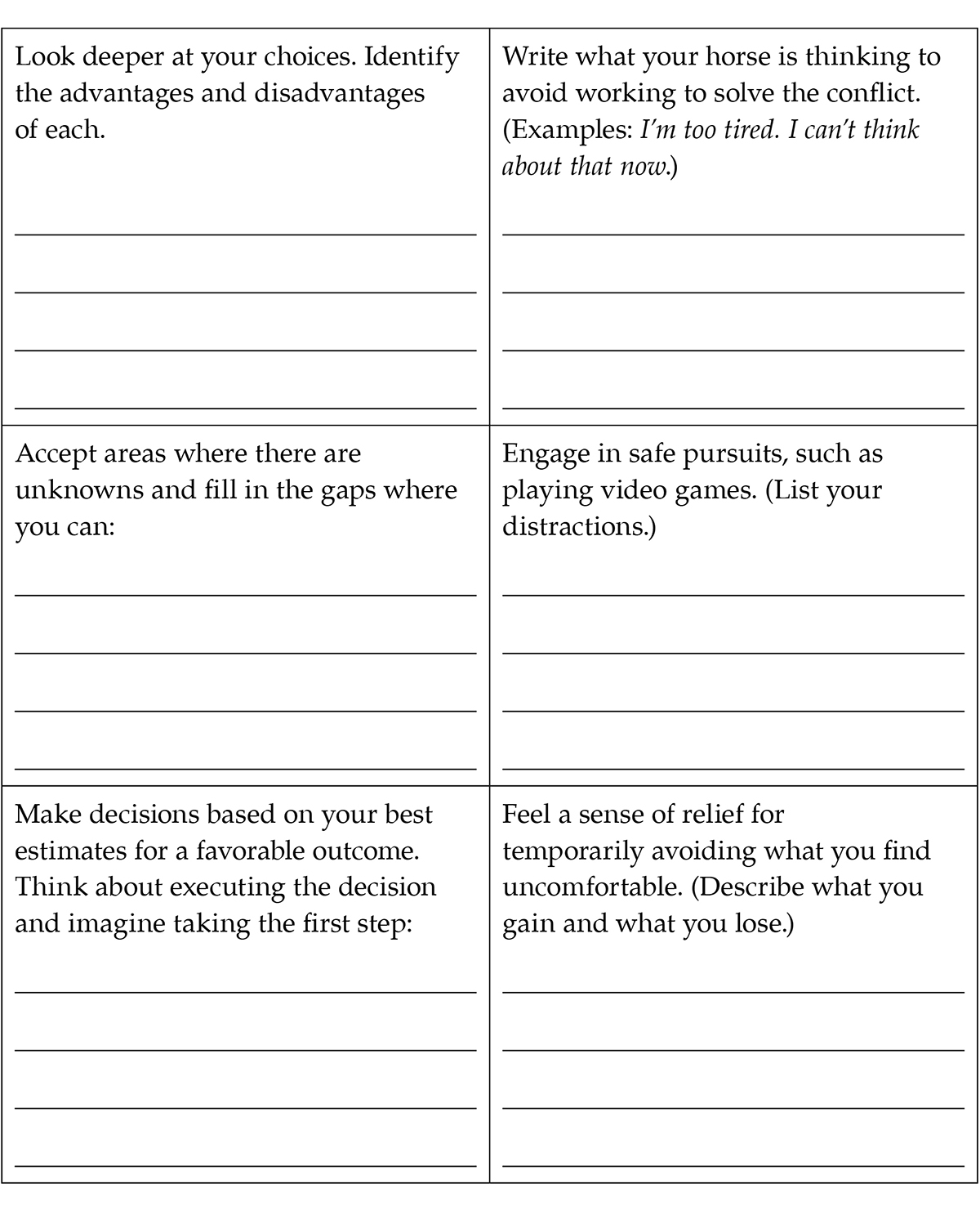

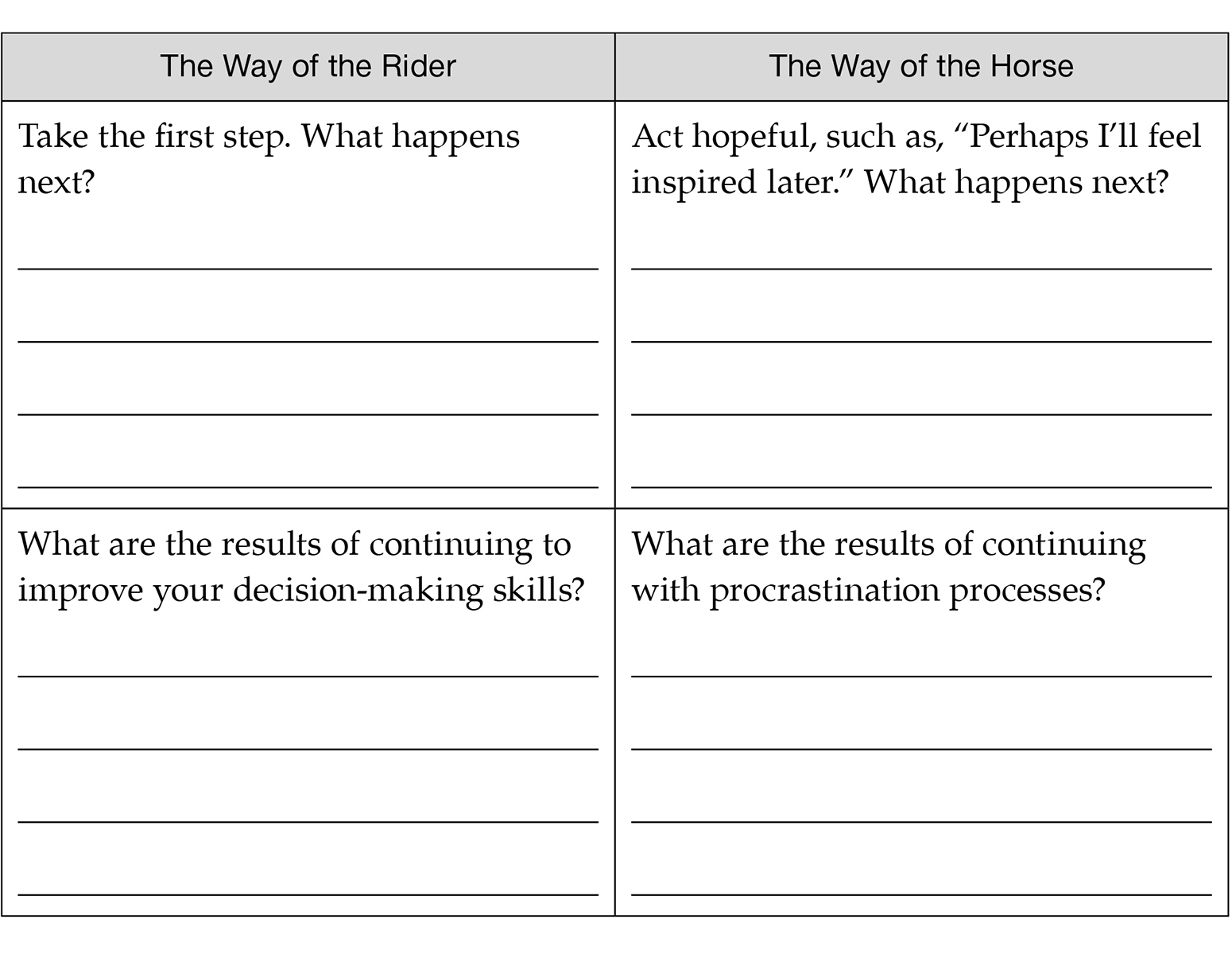

The chart shows both branches of the Y choice. The left column describes the rider’s position, and the right describes the horse’s. Under each example, fill in the blanks.

Once you map your Y-decision paths and compare them, you are in a position to make an informed decision on taking either the rider’s or the horse’s path. What path do you choose? Why?