Chapter 6

Building Your Résumé

The Big Idea

Uncovering a job in all its rich complexity is only the beginning. You’re a long way from getting hired. But truly understanding a Job to Be Done provides a sort of decoder to that complexity—a language that enables clear specifications for solving Jobs to Be Done. New products succeed not because of the features and functionality they offer but because of the experiences they enable.

If you don’t have a preteen girl in your life, you may not understand how anyone can consider paying more than a hundred dollars for a doll. But I’ve done it. Multiple times. That doesn’t even count what we’ve spent on extra clothing and accessories. I think it would have been cheaper for me to buy clothing for myself. My daughter Katie, and many of her friends, coveted pricey American Girl dolls when they were growing up. Check out Craigslist ads right after the holidays—you’ll find a shocking number of parents eager to purchase secondhand or homemade American Girl clothing to supplement their daughter’s Christmas present. By one estimate, the typical American Girl Doll purchaser will spend more than six hundred dollars in total. To date, the company has sold 29 million dolls and racks up more than $500 million in sales annually.

What’s so special about an American Girl doll? Well, it’s not the doll itself. They come in a variety of styles and ethnicities and they’re lovely, sturdy dolls. But to my eye, they look similar to dolls that children have played with for generations. American Girl dolls are nice. But they aren’t amazing.

In recent years Toys“R”Us, Walmart, and even Disney have all tried to challenge American Girl’s success with similar dolls (Journey Girls, My Life, and Princess & Me)—at a fraction of the price—but to date, no one has made a dent. American Girl is able to command a premium price because it’s not really selling dolls. It’s selling an experience.

When you see a company that has a product or service that no one has successfully copied, like American Girl, rarely is it the product itself that is the source of the long-term competitive advantage, something American Girl founder Pleasant Rowland understood. “You’re not trying to just get the product out there, you hope you are creating an experience that will do the job perfectly,” says Rowland. You’re creating experiences that, in effect, make up the product’s résumé: “Here’s why you should hire me.”

That’s why American Girl has been so successful for so long, in spite of numerous attempts by competitors to elbow in. My wife, Christine, and I were willing to splurge on the dolls because we understood what they stood for. American Girl dolls are about connection and empowering self-belief—and the chance to savor childhood just a bit longer. I have found that creating the right set of experiences around a clearly defined job—and then organizing the company around delivering those experiences (which we’ll discuss in the next chapter)—almost inoculates you against disruption. Disruptive competitors almost never come with a better sense of the job. They don’t see beyond the product. Preteen girls hire the dolls to help articulate their feelings and validate who they are—their identities, their sense of self, and their cultural and racial background—and offer them hope that they can surmount the challenges in their lives. The Job to Be Done for parents, who are actually purchasing the doll, is to help engage both mothers and daughters in a rich conversation about the generations of women that came before them, and their struggles and their strength. Those conversations had disappeared as more and more women entered the workforce in the years after the women’s movement, and mothers and grandmothers were craving an opportunity to bring them back into their lives.

“There’s no question in my mind that I came from the thesis that innovation succeeds when it addresses a job that needs to be done,” says Rowland, whose unsatisfactory options while shopping for a Christmas present for her nieces triggered the idea. At the time, the most popular options were either hypersexualized Barbies or Cabbage Patch Kids, neither of which would help her connect with her beloved nieces. Her vision for the company, which was born almost entirely out of her own childhood memories, was built around creating similar happy experiences for the mothers and daughters who buy American Girl dolls. As I said in chapter 4, our lives are very articulate.

The dolls—and their worlds—reflect Rowland’s nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the job. There are dozens of American Girl dolls representing a broad cross section of profiles. For example, there’s Kaya, a young girl from a Northwest Native American tribe in the late eighteenth century. Her back story tells of her leadership, her compassion, her courage, and her loyalty. There’s Kristen Larson, a Swedish immigrant who settles in the Minnesota territory and faces hardships and challenges but triumphs in the end. There’s modern-era Lindsey Bergman who is focused on her upcoming bat mitzvah. And so on. A significant part of the allure is the well-written, historically accurate books about each character’s life that express feelings and struggles that the preteen owner might be sharing. The books may be even more popular than the dolls themselves.

Rowland and her team thought through every aspect of the experience required to perform the job very, very well. The dolls were never sold in traditional toy stores, thrown in the mix alongside any number of competitors. They were initially available only through a catalog, then later at American Girl stores, which were initially created in a few major metropolitan areas. It turned out this added to the experience, turning a trip to the American Girl store into a special day out with mom (or dad). American Girl stores have doll hospitals that can repair tangled hair or fix broken parts. Some of the stores have restaurants in which parents, children, and their dolls can happily sit and be served from a kid-friendly menu—or host birthday parties. The dolls become the catalyst for experiences with mom and dad that will be remembered forever.

No detail was too small to consider for its experiential value. That familiar red-and-pink packaging that the dolls come in? Rowland designed them with a clear window of the doll inside, but they were wrapped with what’s known as a belly band—a narrow wrapper around the whole box—and the dolls were packed in tissue paper. That belly band, Rowland remembers, added two cents and twenty-seven seconds to the actual packaging process itself. The designers suggested they simply print the doll’s name right on the box itself to save time and money—an idea Rowland rejected out of hand. “I said you’re not getting it. What has to happen to make this special to the child? I don’t want her to see some shrink-wrapped thing coming out of the box. The fact that she has to wait just a split second to get the band off and open the tissue under the lid makes it exciting to open the box. It’s not the same as walking down the aisle in the toy store and picking a Barbie off the shelf. That’s the kind of detail we tended to. I just kept going back to my own childhood to the things that made me excited.”

American Girl was so successful in nailing the Job to Be Done of both mothers and daughters that it was able to use its core offerings—and the loyalty they established—as a platform to expand into what might seem to be wildly diverse fields. Dolls, books, retail stores, movies, clothes, restaurants, beauty parlors, and even a live theater in Chicago, all of which Rowland actually had in mind before she launched the company. They simply made intuitive sense to her—based on the happy experiences of her own childhood—and aligned squarely with the job. Going to the live theater for an American Girl show? That harkened back to the days when she used to put on white gloves to go to Chicago Symphony concerts with her own mother. “That was a moment I was trying to re-create for girls when they went to the American Girl store. It was very much coming out of my life experience,” she explains. “I simply trusted my memories of childhood.”

Three decades after its launch, there’s a generation of American Girl fans who are now adults and eager to share the dolls—and the experiences they enable—with their own children. We have a family friend who still buys American Girl dolls for her adult daughter at Christmas with the express wish that she hands them down to her own daughters someday.

Under Mattel’s ownership, it has seen a slight dip in sales in the past couple of years, but no one has been successful in unseating American Girl from its perch. “I think nobody was willing to put the depth in the product to create the experience,” says Rowland. “They thought it was a product. They never got the story part right.” To date, no other toy manufacturer has been able to copy American Girl’s magic formula.

Decoding the Complexity

As I’ve discussed, jobs are complex and multifaceted. But a deep understanding of a job provides a sort of decoder to the complexity—a job spec, if you will. Whereas the job itself is the framing of the circumstance from the perspective of the consumer with the Job to Be Done, as he or she confronts a struggle to make progress, the job spec is from the innovator’s point of view: What do I need to design, develop, and deliver in my new product offering so that it solves the consumer’s job well? You can capture the relevant details of the job in a job spec, including the functional, emotional, and social dimensions that define the desired progress, the tradeoffs the customer is willing to make, the full set of competing solutions that must be beaten, and the obstacles and anxieties that must be overcome. That understanding should then be matched by an offering that includes a plan to surmount the obstacles and create the right set of experiences in purchasing and using the product. The job spec then becomes the blueprint that translates all the richness and complexity of the job into an actionable guide for innovation. Designed without a clear job spec, even the most advanced products are likely to fail. There are just too many details to nail and tricky tradeoffs to be made in creating customer value for innovators to rely on the luck of just guessing right. The experiences you create to respond to the job spec are critical to creating a solution that customers not only want to hire, but want to hire over and over again. There’s a reason successful jobs-based innovations are hard to copy—it’s in this level of detail that organizations create long-term competitive advantage because this is how customers decide what products are better than other products.

Experiences and Premium Prices

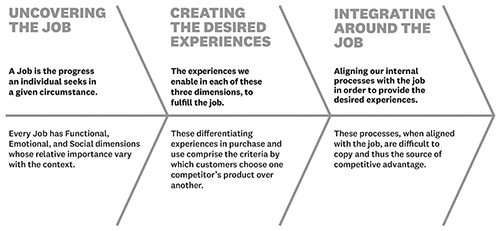

In my classroom I share an illustration with my students to highlight how to think about innovating around jobs. It’s just a simple representation, but it’s intended to underscore the point that although identifying and understanding the Job to Be Done is the foundation, it’s only the first step in creating products that you can be sure customers want to hire. Products that they’ll actually pay premium prices for.

That involves not only understanding the job, but also the right set of experiences for purchase and use of that product, and then integrating those experiences into a company’s processes. All three layers—Uncovering the Job, Creating the Desired Experiences, and Integrating around the Job—are critical. When a company understands and responds to all three layers of the job depicted here, it will have solved a job in a way that competitors can’t easily copy.

© James de Vries

Consider IKEA, for example. IKEA is one of the most profitable companies in the world and has been so for decades. Its owner, Ingvar Kamprad, is one of the wealthiest men in the world. How did he make so much money selling nondescript furniture that you have to assemble yourself? He identified a Job to Be Done.

Here’s a business that doesn’t have any special business secrets. Any would-be competitor can walk through its stores, reverse-engineer its products, or copy its catalog. But no one has. Why not? IKEA’s entire business model—the shopping experience, the layout of the store, the design of the products and the way they are packaged—is very different from the standard furniture store. Most retailers are organized around a customer segment or a type of product. The customer base can then be divided up into target demographics, such as age, gender, education, or income level. There are competitors who sell to wealthy people—Roche Bobois sells sofas that cost thousands of dollars! There are stores known for selling low-cost furniture to lower-income people. And there are a host of other examples: stores organized around modern furniture for urban dwellers, stores that specialize in furniture for businesses, and so on.

IKEA doesn’t focus on selling to any particular demographically defined group of consumers. IKEA is structured around jobs that lots of consumers share when they are trying to establish themselves and their families in new surroundings: “I’ve got to get this place furnished tomorrow, because the next day I have to show up at work.”

Other furniture stores can copy IKEA’s products. They can even copy IKEA’s layout. But what has been difficult to copy are the experiences that IKEA provides its customers—and the way it has anticipated and helped its customers overcome the obstacles that get in their way.

Nobody I know relishes the idea of spending a day shopping for furniture when they really, really need it right away. It’s not entertainment, it’s a frustrating challenge. Factor in that your children will likely be with you when you’re shopping and it could be a recipe for disaster. IKEA stores have a designated child-care area where you can leave your children to play while you wind your way through the store—and a café and ice cream stand to offer as a reward at the end. Don’t want to wait to get your bookshelves home? They’re flat-packed in cartons that can fit in or on most cars. Is it daunting to lay out all the parts to an unbuilt book-shelf and then have to put it together yourself? Absolutely. But it’s not overwhelming because IKEA has designed all its products to require just one simple tool (that’s included with every flat pack—and actually stored inside one of the pieces of wood so you can’t accidentally lose it when you open the box!). And everyone I know who has tackled an IKEA assembly ends up feeling pretty proud of himself or herself when it’s done.

Who is IKEA competing with? My son Michael hired it when he moved to California to start his doctoral studies: “Help me furnish my place today.” He’s got to decide what he’ll hire to do the job. So how does he decide? He has to have some kind of criteria to make his choice. At a fundamental level, he will factor in how much he cares about the basics of the offering: cost and quality, and the priorities and tradeoffs he’s willing to make in the context of the job he needs to get done. But he’ll care even more about what experiences each possible solution offers him in solving his job. And what obstacles he’d have to overcome to hire each possible solution.

He’ll hire IKEA, even if it costs more than some of those other solutions, because it does the job better than any alternatives. The reason why we are willing to pay premium prices for a product that nails the job is because the full cost of a product that fails to do the job—wasted time, frustration, spending money on poor solutions, and so on—is significant to us. The “struggle” is costly—you’re already spending time and energy to find a solution and so, even when a premium price comes along, your internal calculus makes that look small compared with what you’ve already been spending, not only financially, but also in personal resources.

Other furniture stores might offer Michael free delivery, but it will probably take days or even weeks to deliver the furniture he wants to purchase. What is he going to sit on tomorrow? Craigslist offers bargains, but he’ll have to cobble together his furniture choices and rent a car to drive all over town to get them, probably enlisting a friend to help him lug them up and down the stairs. Discount furniture stores might offer some of IKEA’s benefits, but they’re not likely to be so easy to assemble at home. Unfinished furniture stores have decent quality products, but you have to paint them yourself! That’s not easy to pull off in a small apartment. He’s not likely to feel good about any of these other choices.

You can only shape the experiences that are important to your customers when you understand who you are really competing with. That’s how you’ll know how to create your résumé to be hired for the job. And when you get that all right, your customers will be more than willing to pay a premium price because you’ll solve their job better than anyone else.

I should clarify, however: sometimes customers get pushed into paying for premium products because they’re interdependent with a product that they have already hired to solve a job in their lives. Think about the eye-popping price tag for printer-ink cartridges. Or smartphone rechargers or cases. We’ll give in and pay the premium price because there isn’t a better solution at the moment, but we will simultaneously despise the company for taking us to the cleaners. These products actually cause anxiety, rather than resolve it. I hated having to monitor how much color ink my kids were using on our home printer. I don’t like worrying about misplacing a charger. This is not what I mean about premium prices that customers are willing to pay. By contrast, with jobs-based innovations, customers don’t resent the price, they’re grateful for the solution.

Removing the Obstacles

Products that succeed in solving customers’ jobs essentially perform services in that customer’s life. They help them overcome the obstacles that get in their way of making the progress they seek. “Help me furnish this apartment today.” “Help me share our rich family history with my child.” Creating experiences and overcoming obstacles is how a product becomes a service to the customer, rather than simply a product with better features and benefits.

Medical-device manufacturer Medtronic learned this the hard way when it was trying to introduce a new pacemaker in India. On the surface, it seemed like a market full of potential, because, unfortunately, heart disease is the country’s number one killer. But for a variety of reasons, very few patients ever ended up opting for a pacemaker to solve their medical problem. For years, Medtronic had relied on traditional forms of research to develop its product offerings. “We were very good at understanding functional jobs,” recalls Keyne Monson, then senior director of international business development at the medical device manufacturer. For example, when Medtronic was looking to improve its pacemakers, it assembled panels of doctors to pick their brains about what they’d like to see in the next generation of the devices. The company then fielded quantitative surveys that validated the physician panels’ feedback and new products were created.

The new versions of Medtronic’s pacemaker were clearly superior, but unfortunately they didn’t sell in India as well as the company had hoped. It had been nagging at Monson for some time that neither the qualitative nor quantitative approaches Medtronic had historically relied on had actually answered the question of why people would want to hire a pacemaker and what obstacles might get in their way—and to do so for the broader set of stakeholders involved.

With the lens of Jobs to Be Done, the Medtronic team and Innosight (including my coauthor David Duncan) started research afresh in India. The team visited hospitals and care facilities, interviewing more than a hundred physicians, nurses, hospital administrators, and patients across the country. The research turned up four key barriers preventing patients from receiving much-needed cardiac care:

- Lack of patient awareness of health and medical needs

- Lack of proper diagnostics

- Inability of patients to navigate the care pathway

- Affordability

While there were competitors making some progress in India, the biggest competition was nonconsumption because of the challenges the Medtronic team identified.

From a traditional perspective, Medtronic might have doubled down on doctors, asking them about priorities and tradeoffs in the product. What features would they value more, or less? Asking patients what they wanted would not have been top of the list of considerations from a marketing perspective.

But when Medtronic revisited the problem through the lens of Jobs to Be Done, Monson says, the team realized that the picture was far more complex—and not one that Medtronic executives could have figured out from pouring over statistics of Indian heart disease or asking cardiologists how to make the pacemaker better. Medtronic has missed a critical component of the Job to Be Done.

The experience of being a candidate for a pacemaker was filled with stresses and obstacles. For a patient to receive a pacemaker to help solve his heart issues, he would have had to navigate a complicated path. First, he might have seen a local general practitioner (GP), typically the first line of medical care, but not always someone with formal medical training. Each of these doctors saw hundreds of patients in a given day. “There were patient lines stretching down the hall,” Monson recalls. “There were so many people waiting to see the local GP, they actually pushed from the hallway into the doctor’s interview room and were lining the walls there, too.” The local GP had about thirty seconds with each patient and then he was passed on, either with a prescription, recommendations, or a referral to a specialist. Symptoms that might suggest a pacemaker can be easily confused with those of other medical conditions. It would be virtually impossible for a prospective patient to find his way from a brief GP visit to the right heart surgeon to implant a pacemaker.

Even if he did get that far, referral to a higher-order specialist meant the patient was jettisoned into a system in which he was a complete stranger to the medical teams who would take the process further. Navigating the referral process after a GP did recommend someone for a pacemaker was confusing—and expensive—for a patient who had to pay for health care out of pocket.

So Medtronic adjusted not only its marketing efforts, but also the services it provided to directly target potential patients. For example, in conjunction with local cardiologists, Medtronic organized heart-health screening clinics across the country—providing prospective patients with free, direct access to specialists and high-tech equipment without having to go through an overwhelmed GP first.

The question of paying for a pacemaker and the attendant medical services was no small concern. So Medtronic created a loan program to help patients pay for the pacemaker procedure. The company initially assumed that patients might be drawn to loans that actually expired upon the patient’s death, so that they were not saddling the family with the burden of debt—the emotional and social component of their Job to Be Done. And, as the Medtronic team learned from patients themselves, that was what they often wanted. But friends and family wanted something different: they tended to rally around a patient to find the money necessary. In those cases, the patient was more likely simply to need a bridge loan until those funds could be gathered. Medtronic made sure that the loan process was not daunting for the family: a loan is typically approved within two days, requiring minimum paperwork and entailing no asset mortgage.

The experience of navigating the complex web of health care in India could be overwhelming for both patients and their families. So the company began to work with local hospitals to create a patient counselor role, initially calling them “Sherpas,” that helped patients navigate the often mind-boggling bureaucracy of a hospital, keeping their procedure and aftercare as top priorities.

The patient counselor role became so popular that hospitals asked if the company would allow patients obtaining pacemakers through traditional routes to seek assistance from a counselor, too. Seeing an opportunity to further identify Jobs to Be Done from within the hospital system, Medtronic jumped at the chance. “At the end of the day, we realized the role was such an important position, we adjusted the role. And we were OK with it,” Monson recalls. “It ingrained the value of that person into the entire hospital system, and thus our business model. And it made us the partner of choice. To me that was a clear example of hitting a Job to Be Done.”

The first Medtronic pacemaker distributed through the Healthy Heart for All (HHFA) program in India was implanted in late 2010. Medtronic currently has partnerships with more than one hundred hospitals in thirty cities. India is considered to be one of the most high-potential growth markets for the company.

According to Shamik Dasgupta, vice president of the Cardiac and Vascular Group, Indian Sub-Continent, Medtronic, “Under the HHFA initiative since its beginning till December 2015, around 167,000 patients have undergone screenings for heart diseases till date, out of which 89,900 patients were counselled and around 15,000 patients have received treatment, with financial assistance facility availed in approximately 550 cases.”

Making that possible involved creating relationships with several partners who helped Medtronic accomplish customers’ jobs. “Through the assessment of Healthy Heart for All, Medtronic understood the need for partners in different stages of the patient care pathway who can be a strong support in removing the barriers to treatment access,” says Dasgupta. “In this case, partners with capabilities in financing, administration of loans, screening and counselling of patients played a major role. With programs like Healthy Heart for All, Medtronic is delivering greater value to patients, healthcare professionals and hospitals. And it is this value which brings true differentiation where product differentiation may not be easy to demonstrate.”

The Uber Experience

The value of creating the right set of experiences in a circumstance-specific job is clearly not universally understood. I don’t know anyone who relishes the experience of renting a car, for example. You land at an airport, tired from travel, and eager to get on the road to your destination. But first you have to find your particular car rental counter in the arrivals area of the airport or figure out where you can find the shuttle bus to take you to a large parking lot offsite where your car will be waiting for you. The lines to check in or check out are often long, and it’s not uncommon to finally get to the front of the line and learn you could have done some form of “speedy check-in” instead. You have to time your return of the car rental to allow you to fill up the gas tank right before you turn into the lot because you don’t want to have to pay above-market rates for a top-up. And every renter I know anxiously hovers around the person checking the car back in to make sure you’re not later held responsible for scratches or dings that the car rental company declares happened on your watch. Some car-rental locations close early on the weekends, impacting your decision about when you need to get back to the airport. Even when nothing goes wrong, it’s almost always an unpleasant experience, with attendant frustrations and anxieties.

Simply Google “car rental reviews” and you’ll see how much customers love the experience of renting a car. It’s not hard to find hashtags that tell us how well the car-rental industry is serving its customers: you’ll easily find #hertzsucks and #avissucks on Twitter, to name just two. Online you’ll find an onslaught of complaints, most mentioning nothing about the cars the companies rent, but focusing instead on the experience that accompanied actually renting the car. Yet with the exception of some minor tinkering at the edge (skip the counter at the airport for frequent customers), car-rental companies continue to compete almost exclusively on price or the variety of cars they have to offer.

Customers actively seek out workarounds—even if they’re imperfect. If they’re traveling for business and they’re senior enough in a company, they might impose on junior local staff to get the rental car and then pick them up at arrivals. Or hire a car service for the full day. I know of one guy who, when his plane was unexpectedly diverted, paid for an Uber all the way from Milwaukee to Chicago rather than endure the stress and hassle of renting a car.

These workarounds should be warning signs to the car-rental industry—which may find itself facing an onslaught from new competitors in the near future as the job of “mobility” takes shape. Failing to deliver the experiences that help your customers solve their Jobs to Be Done leaves you vulnerable to disruption as better solutions come along and customers swiftly jump ship.

By contrast, one company that clearly understands the stakes is Uber. In the last several years, few companies have captured the media’s attention like Uber. In my opinion, Uber has been successful because it’s perfectly nailed a Job to Be Done. Yes, Uber can often offer a nice car to take you from point A to point B, but that’s not where it’s built its competitive advantage. The experiences that come with hiring Uber to solve customers’ Jobs to Be Done are better than the existing alternatives. That’s the secret to its success.

Everything about the experience of being a customer—including the emotional and social dimensions—has been thought through. Who wants to have to outmaneuver other poor schlubs on the same street corner who are trying to hail a cab? You don’t want to either pay for a car service to wait outside your meeting or be at its mercy when you’re finally ready to call it to come back and get you. With Uber, you simply push a few buttons on your mobile phone and you know that in three minutes or seven minutes a specific driver will arrive to pick you up. Now you can relax and just wait. You don’t have to worry if you have enough cash in your wallet or fear that if you swipe your credit card in that taxi machine, you’ll get a call from your bank wondering if you’ve recently made purchases in some state you’ve never even been to. Calling an Uber has even more potential to ease your anxieties about getting into a cab alone. With Uber there’s a record of your request, you know specifically who is picking you up, and you know from the driver’s ratings that he or she is reliable. Uber isn’t just competing with taxis and car services, it’s also competing with opting to take the subway home or calling a friend.

Organizations that focus on making the product itself better and better are missing what may be the most powerful causal mechanism of all—what are the experiences that customers seek in not only purchasing, but also in using this product? If you don’t know the answer to that question, you’re probably not going to be hired.

How Do I Know You’re Right for the Job?

Amazon, too, knows exactly what experiences its customers value. Everything is built around delivering those experiences well. There are many factors that have enabled Amazon’s meteoric growth, but there is no way it could be “the everything store” without its customer reviews. In fact, I’d argue that it’s probably the hardest thing for any would-be competitor to copy.

Why are Amazon’s reviews so powerful? Because they help customers make the progress they want to make. If I look around my house or my friends’ houses, for example, I can see a wide variety of products that were purchased on Amazon. A TV. A rice steamer. A digital camera. A smoothie maker. What enables me and millions of others to buy unfamiliar items with greater confidence by virtue of a listing on a website? The requisite list of features and functionality doesn’t help me much—in fact my eye tends to skip right over that section. But it does go immediately to the line that tells me where I can figure out if this is the right product to hire for my job: “56 reviews. 21 answered questions.”

Sure, seeing an item with a bunch of four-out-of-five-star ratings helps, but what I really need to know is what do reviewers who were hiring for the same job as me have to say? There might be lots of toaster oven reviews about whether it browns the toast evenly (there are, apparently, a lot of people who care about that stuff!), but I really want to know whether it will help me heat a frozen pizza when I don’t want to crank up our conventional oven. I’m sure many people care about the pixels and zoom on a digital camera, but I just want to know that it is easy to set up and use. In other words, Amazon allows me to shop unfamiliar categories with total confidence because I can find folks who share my job and gauge the performance that matters most to me from those reviews.

Amazon clearly understands the importance of these reviews. There are Hall of Fame reviewers (so noted on each review) and top ten thousand reviewer rankings—ranked by the number and percentage of helpful votes their reviews have received. In 2015 Amazon also introduced technology that automates giving more weight to newer reviews, reviews from verified Amazon purchasers, and reviews that more customers voted as being helpful.

Companies that sell their wares on Amazon are so sensitive to the power of these reviews that they routinely email their customers shortly after the purchase has arrived at its destination to ask if they have any feedback—hoping to preempt any negative feedback before they end up on the review page. They go to extraordinary lengths, including no-hassle refunds or replacements, rather than risk a bad review from a top reviewer who will, certainly, influence how many people hire that product for their Job to Be Done. The experience that those reviews provide other customers is highly valued: “I don’t want the hassle of having to return it or just considering it wasted money. And I don’t want to wait two days to find out I still need another solution. How can I be sure I’m not making a mistake?”

Online reviews have fundamentally improved the experience of purchasing almost anything in recent years. We can check reviews on everything from auto repair shops to insurance companies with a few clicks on our keyboard. Online reviews help great products get hired.

But they are a two-sided coin. From the business’s perspective, they represent the first time in history where you have to think about how to convey who should not hire your product. A customer who hires your product or service for a job it is not intended to do will be sorely disappointed—and perhaps write a disgruntled online review. Negative reviews can break a business. Restaurant owners routinely grouse about being held hostage to their Yelp ratings, at the mercy of reviews by uninformed palates. Airbnb works with its “host” customers to make sure their listings make very clear who should—and shouldn’t—hire that particular listing, says Airbnb’s Chip Conley. Airbnb advises hosts to imagine that there’s “an invisible report card on the forehead of potential guests,” rating everything about how the actual location met their expectations. “Overselling” your listing will work against you very quickly on Airbnb—and in the increasing number of marketplaces in which reviews function almost like a currency.

Airbnb listings emphasize what the local neighborhood is like and what kind of experience guests will have in the home. Is it convenient? Is it quiet and peaceful? Is it in the center of action? All those details are important to capture in both the description and photos so that guests won’t be disappointed with their choice—and write a poor review.

Research has suggested that as many as 95 percent of consumers use reviews and 86 percent say they are essential when making purchase decisions.1 And nearly one-third of consumers under the age of forty-five consult reviews for every single purchase. Businesses now have to consider how to educate customers about what job these products and services are designed to do2—and when potential customers should not consider hiring them. That is a new wrinkle.

Purpose Brand

There is a tool that helps you avoid leaving your product or service vulnerable to customers who hire it for the wrong reasons. Done perfectly, your brand can become synonymous with the job—what’s known as a purpose brand. When I list these brands, you will surely instantly know what job they’ve been hired to do:

- Uber

- TurboTax

- Disney

- Mayo Clinic

- OnStar

- Harvard

- Match.com

- OpenTable

And one of my personal favorites, Jack Bauer. When you need to save the world in twenty-four hours, Jack Bauer is your man.

A product that consistently creates the right experiences for resolving customers’ jobs should speak to the consumer: “Your search is over, pick me!” If you need to furnish the apartment you just rented or outfit your daughter’s dorm room, you better hope there’s an IKEA nearby. IKEA has become a purpose brand for “Help me furnish my apartment today.”

Purpose brands play the role of communicating externally how the “enclosed attributes” are designed to deliver a very complete and specific experience. A purpose brand is positioned on the mechanism that causes people to purchase a product: they nail the job. A purpose brand tells them to hire you for their job.

The reward for perfectly performing a job is not brand fame or brand love—though that may follow—but rather that customers will weave you into the fabric of their lives. Because purpose brands integrate around important Jobs to Be Done rather than conform to established bases of competition, purpose brands frequently reconfigure industry structure, change the basis of competition, and command premium prices.

If you wanted to enjoy a decent single cup of coffee at home, you were in a world of trouble before Keurig came to your rescue. The parental lifesaver known as Lunchables didn’t exactly compete with the deli counter, the cheese department, or the cracker aisle, but they sure made life easier. Before Fred Smith launched FedEx, urgent documents had to be handed to couriers who would then fly anywhere to meet an important deadline.

FedEx is now a household name, but breaking into the market might have seemed impossible decades ago. But through a job lens, it makes sense. When competitors successfully enter markets that seem closed and commoditized, they do it by aligning with an important job that none of the established players has prioritized. Pixar gave theatergoers a reason to care about the studio producing a film. The Apple brand assures people that the technology will be easy to use and elegantly designed. American Girl enables mothers and daughters to connect and create shared experiences in ways that defy industry categorization.

Milwaukee Electric Tool Corporation has cornered the market in two areas with its strong purpose brands: Sawzall and HOLE HAWG. Sawzall is a reciprocating saw that tradesmen hire when they need to cut through a wall quickly and aren’t sure what’s under the surface. It’s hired for the job of helping tradesmen saw safely through pretty much anything. No panic required when you start the saw. When I look at a wall and I don’t know what’s behind it, there’s one thought that jumps into my mind: where is my Sawzall?

Plumbers hire Milwaukee’s HOLE HAWG, a right-angle drill, when they need to drill a hole in a tight space. Competitors like Black & Decker, Bosch, and Makita offer reciprocating saws and right-angle drills with comparable performance and price, but none of them has a purpose brand that pops into a tradesman’s mind when he has one of these jobs to do. Milwaukee has owned more than 80 percent of these two job markets for decades.

The company’s other tools, which rely on the Milwaukee brand, are not nearly as celebrated. The word “Milwaukee” doesn’t give you any market whatsoever. But Sawzall and HOLE HAWG are hired for very specific jobs—and they’ve become purpose brands.

Purpose brands provide remarkable clarity. They become synonymous with the job. A well-developed purpose brand will stop a consumer from even considering looking for another option. They want that product. The price premium that a purpose brand commands is the wage that customers are willing to pay the brand for providing this guidance.

Federal Express illustrates how successful purpose brands are built. A job had existed practically forever: the “I need to send this from here to there—as fast as possible with perfect certainty” job. Some US customers hired the US Postal Service’s airmail; a few desperate souls paid couriers to sit on airplanes. But because nobody had yet designed a service to do this job well, the brands of the unsatisfactory alternative services became tarnished when they were hired for this purpose. But after Federal Express specifically designed its service to do that exact job, and did it wonderfully again and again, the FedEx brand began popping into people’s minds.

This was not built through advertising. It was built through people hiring the service and finding that it got the job done. FedEx became a purpose brand—in fact, it became a verb in the international language of business that is inextricably linked with that specific job.

A very long list of purpose brands, including Starbucks, Google, and craigslist.org, were actually built with minimal advertising at the outset. They’re such strong brands that they’ve become verbs: “Just Google it.” But they have been successful because each is associated with a clear purpose—they’ve been optimized around a clear Job to Be Done. These brands just pop into consumers’ minds when they have a Job to Be Done.

By the same token, brands that fail to integrate around a job risk becoming category placeholders—forced to compete on price, slugging it out with look-alike competitors. Just think airlines, automakers, business hotel chains, rental-car companies, or PC-clone manufacturers. Being called a “clone” can never be a good thing.

But it can be all too easy for an organization to lose its understanding of the power of a purpose brand when it falls into the bad habits of adding new benefits and features in the interest of creating marketplace “news” or justifying a price increase. For years, Volvo was the family car in my hometown. The distinctive, boxy cars were ubiquitous in the parking lots of schools, grocery stores, and baseball fields all across town. They may have cost more than other family car options and, let’s face it, they were unattractive—but they stood for something important: safety. As far back as its founding in 1927, its two original leaders set the compass directly on this purpose: “Cars are driven by people. The guiding principle behind everything we make at Volvo, therefore, is and must remain, safety.” And in the decades since then, the Swedish car company had earned its sterling reputation—as a purpose brand for safety and reliability.

But after Ford purchased Volvo in 1999, it seemed to veer off that clear brand, creating flashier cars to try to compete with luxury standard vehicles. The result was not only a decline in sales—but an opening in the market for competitors’ cars to tout their own safety features. Volvo no longer owned that status. By 2005 it was no longer even profitable. The recession didn’t help. In 2010 Ford gave up on Volvo altogether, selling it at a substantial loss to Chinese carmaker Geely. “We lost our way,” Volvo North America CEO Tony Nicolosi told Autoweek in 2013.3 “We gotta go back to our roots. Society is coming back to what we represent as a brand: environment, family, safety. We’ve just been poor at communicating it.” Under Geely’s ownership and substantial investment—with a renewed focus on safety and reliability—Volvo finally began growing again in 2015. But I fear it may have lost its purpose brand status forever.

Purpose brand makes very clear which features and functions are relevant to the job and which potential improvements will ultimately prove irrelevant. A purpose brand is not solely valuable to the customer in making his choices. Purpose brands create enormous opportunities for differentiation, premium pricing, and growth. A clear purpose brand guides the company’s product designers, marketers, and advertisers as they develop and market improved products. As I’ll discuss in the next two chapters, having a Job to Be Done as a North Star helps guide an organization to design the right product and experiences to achieve that job—and not “overshoot” in a way that consumers won’t value.

Achieving a purpose brand is the cherry on the top of the jobs cake. Purpose brand, when done well, provides the ultimate competitive advantage. Look no further. Don’t even bother shopping for anything else. Just hire me and your job will be done.

Chapter Takeaways

- After you’ve fully understood a customer’s job, the next step is to develop a solution that perfectly solves it. And because a job has a richness and complexity to it, your solution must, too. The specific details of the job, and the corresponding details of your solution, are critically important to ensure a successful innovation.

- You can capture the relevant details of the job in a job spec, which includes the functional, emotional, and social dimensions that define the desired progress; the tradeoffs the customer is willing to make; the full set of competing solutions that must be beaten; and the obstacles and anxieties that must be overcome. The job spec becomes the blueprint that translates all the richness and complexity of the job into an actionable guide for innovation.

- Complete solutions to jobs must include not only your core product or service, but also carefully designed experiences of purchase and use that overcome any obstacles a customer might face in hiring your solution and firing another. This means that ultimately all successful solutions to jobs can be thought of as services, even for product companies.

- If you can successfully nail the job, over time you can transform your company’s brand into a purpose brand, one that customers automatically associate with the successful resolution of their most important jobs. A purpose brand provides a clear guide to the outside world as to what your company represents and a clear guide to your employees that can guide their decisions and behavior.

Questions for Leaders

- What are the most critical details that must be included in the job spec for your target job? Do you understand the obstacles that get in customers’ way? Do your current solutions address all these details?

- What are the experiences of purchase and use that your customers currently have? How well do these align with the requirements of their complete job spec? Where are there opportunities to improve them?