If someone told you that there was a medical disorder in which 80 percent of the patients were women, and the average age of onset was thirty to fifty years of age, what connections do you think might be obvious to study? It seems pretty important to look at a factor, or factors, that make women different from men in that age range, wouldn’t you agree? As I mentioned in an earlier chapter, I have done a great deal of work with chronic pain patients since my residency at Johns Hopkins in the early 1980s. Over the years, I have been struck by the fact that almost all of the fibromyalgia patients I see are women, typically over forty, and frequently with a history of hysterectomy or early menopause. The obvious gender difference in this common medical disorder made me consider two important points: (1) the age range of thirty to fifty is a time of significant hormonal changes for women, but not typically a time of marked hormonal change for men, and (2) women’s pain symptoms typically flared up at certain times of their menstrual cycle and subsided at other times in the cycle. I thought there might be a connection with changes in estrogen and progesterone and how these hormones affect brain chemistry in the pain-regulating centers of the nervous system.

The more I began looking into these connections in evaluating patients, the more I was stunned to find marked degrees of hormonal loss, which clearly could be of clinical significance in addressing the chronic pain problems. The information available was so profound, and so overlooked, I have now written a complete book addressing the overlooked hormone connections in fibromyalgia. I realize that with something as complex as fibromyalgia and chronic pain, there are multiple causative and contributing factors. It is too simplistic to say that these medical problems are due to, or only caused by, declining estrogen and other female hormones. My question, however, is why haven’t physicians and researchers in the field of chronic pain even considered female hormonal factors when the majority of patients with fibromyalgia are female? I continue to be astounded at the collective lack of awareness of women’s physiological differences and the failure to include these variables in clinical management and our research models.

Listen to one woman’s voice (one of many who has made the connections with her menstrual cycle menopausal hormonal changes):

I am forty-five, and I’ve felt for about ten years that there were problems with my hormones. Around the time of my period, the pain seems to increase markedly. As I have been getting closer to menopause, I feel like my fibromyalgia has increased a lot. My doctors say there is absolutely (!) no hormonal connection in fibromyalgia, I’ve been made to feel I’m stupid for even asking such a dumb question. When I have asked what can help my pain, I have felt talked down to. The only thing offered me was to exercise more. No one is really listening to me.

In addition to overlooking the role of female hormones in fibromyalgia, we have also been too slow in looking at some of the brain hormones and chemical messengers (serotonin, dopamine, epinephrine, substance P, and others) in approaching chronic pain as a problem very different from acute pain. It was over twenty years ago during my specialty training at Johns Hopkins that we were using serotonin-modulating medications to help patients with chronic pain. But use of these types of medication in fibromyalgia is just now beginning to gain more widespread use; such approaches are so important that they need wider use. Management options for chronic pain are still largely in the dark ages with negative stereotypes of patients (the majority of whom are women, remember?) as “neurotic,” “drug-seekers,” “addictive personalities,” and so on. I hope this chapter will help you see that new hope, help, and treatment approaches are available if you have been struggling with the chronic pain of fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia (FMS) is a condition that has been described in the medical writings for several thousand years, going back to the time of Hippocrates and early Chinese physicians. It is also the second most common rheumatological disorder, following osteoarthritis in frequency. The disorder we currently call fibromyalgia has been called a number of different names over the years: rheumatism, neurasthenia, myofascial pain syndrome, myositis, fibrositis, fibromyositis, myalgia. FMS is difficult to diagnose on objective physical findings. Although it is far more common in women, I have only once seen a medical article mention checking blood levels of ovary hormones in women with fibromyalgia. Studies have shown low growth hormone (GH) and low serotonin (ST) levels in FMS patients, but these changes are found in other disorders as well, and both GH and ST are decreased by decline in estradiol. One problem is that there are no consistent lab abnormalities in FMS, such as objective measures of inflammation or actual damage to the muscles. In fact, we are now fairly certain that there is no actual inflammation of the muscles in FMS. Furthermore, FMS is a disorder of diffuse pain throughout major areas of the body; patients do not have a specific, easily identifiable lesion in one area. For all of these reasons, FMS is a particularly frustrating condition, both for patients who suffer with it, and doctors who want to offer their patients some help and relief. Since FMS has been difficult to pin down, this syndrome was long viewed by many medical people with skepticism and disparagement. Doctors saw it as something vague and psychosomatic because its symptoms come and go, the pain is hard to localize, and there are no objective changes in the body when the person is experiencing pain. Add to all this what we already know about the negative stereotypes commonly applied to the female patient, and you can begin to see how a problem that occurs more often in women and is a vague, ill-defined syndrome was often labeled a psychogenic illness.

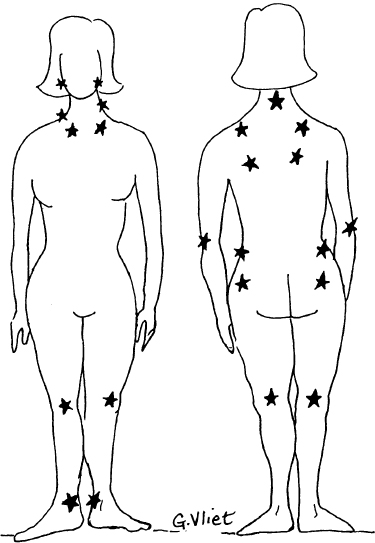

In 1990, FMS was finally recognized as a legitimate disorder and was given standard diagnostic criteria based upon the presence of both of these findings: (1) persistent pain or achiness at multiple body sites, and (2) the presence of painful trigger points at a minimum of eleven of the eighteen classic sites shown in the diagram below. Current research has shown that individuals with FMS show increased sensitivity to pain throughout the entire body, even areas such as the forehead, rather than just tenderness at the discrete points shown in the diagram as was originally thought. This observation is helpful because it lends support to the concept that the increased sensitivity to pain (or global reduction in pain threshold) is based in the brain (central nervous system, CNS) rather than just in the muscles or nerves of the body (peripheral nervous system, PNS). There are many mechanisms that may affect the CNS pain centers, such as estrogen balance in women, among others. The summary chart below shows some of the characteristic findings of FMS itself, along with nonmuscular associated conditions that have been reported in more current research on FMS. It is striking that many of the associated disorders and conditions that are found to be more common in patients with FMS are also ones that are markedly affected by a decline in ovary hormone production, especially estrogen. Associated conditions described in the FMS medical literature are the same conditions being described in the menopause medical literature about the widespread effects of declining estrogen. We will discuss these hormone aspects in more detail in this chapter, but I want you to begin thinking about this now as it may relate to your own experience.

HALLMARK FEATURES OF FIBROMYALGIA

• generalized stiffness and soreness, often worse in the morning

• increased pain in neck, trunk, and hips

• restless, fragmented sleep

• exquisite tender points where muscles and tendons meet

• numbness, burning, or cold sensations in muscles and/or extremities

• diminished energy, marked fatigue

• commonly associated with mood changes: irritability, lability, depression

• commonly associated with alterations in memory and concentration

• associated with high incidence of recurrent noncardiac chest pain, palpitations

• commonly associated with smooth muscle dysmotility (irritable bowel, esophageal reflux, urinary frequency, interstitial cystitis, dysmenorrhea, TMJ pain)

• higher incidence of CNS-mediated hypotension in FMS patients than in persons without FMS

• may be associated with hearing changes/decreased painful sound tolerance

• altered motility of ocular muscles, and vestibular abnormalities

• may be associated with migraine headaches, multiple chemical sensitivities

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995

What is a trigger (tender) point? This is an area where muscle and tendons meet at bone and produce pain that may radiate to other areas as well. A trigger point is defined as positive when pressure of about 4 kg applied to the area during physical examination causes a localized sensation of increased tenderness and pain. It is possible to have other types of chronic myofascial pain syndromes without having all eleven painful trigger points required for the diagnosis of FMS. In this chapter, I have focused on FMS, but I want you to keep in mind that many of the same factors that make FMS worse will also aggravate other myofascial pain syndromes. The use of tender points to confirm a diagnosis of FMS has some problems, and researchers are trying to find better ways of assessing the abnormalities in pain threshold with this disorder. Studies have shown that tenderness is a characteristic that varies a great deal along a continuum in the general population. This means that some patients who do have FMS will be excluded if tenderness is a primary diagnostic feature, and others who have a biological tendency to have more tenderness sensitivity will be overdiagnosed. Tenderness is also influenced by a variety of other factors that may not themselves predispose to developing FMS: getting older, being female, not being very physically fit, poor nutrition. Again, the problem is that the diagnostic criteria may fail to recognize some people who have FMS and include others who don’t. At some point, we will need to find a better method of measuring the pain threshold and abnormalities, such as using a dolorimeter (a pressure gauge applied against the skin), in order to better define this disorder.

FMS is often confused with arthritis, a group of inflammatory disorders that lead to joint deterioration and pain. FMS may occur along with osteoarthritis and other types of arthritis. But unlike arthritis (inflammation of the joints) and arthralgias (soreness, aching of the joints), fibromyalgia does not affect the joints directly. It affects the muscles, tendons, and ligaments. When you have muscle pain with movement, or the muscles have become tight in spasm, this can then affect the way joints function and thus may give the impression that fibromyalgia is in your joints. FMS does not cause deformities or permanent crippling as may happen with arthritis, but it can certainly interfere with quality of life and ability to function optimally. Many patients describe the pain as “intrusive,” “overwhelmingly present,” “debilitating,” a “robber of my life.” These convey how serious this problem is. In addition, there is often a peculiar fuzziness of thinking that sufferers euphemistically call “fibrofog,” but the term doesn’t convey how devastating the mental cloudiness and confusion can be and the extent to which it can rob you of your ability to carry out even basic daily activities.

Fibromyalgia may also be precipitated by some type of trauma, whether a car accident with whiplash injuries, a severe jarring type of fall, or a surgery followed by prolonged inactivity. The anatomic and biochemical changes that occur with such traumas create severe, wide-ranging effects in the tissues of the body, and then set the foundation for the chronic pain cycle to begin. Hans Selye, M.D., the pioneer in stress research and keen observer of the multiple body effects of continued, repeated stressors, coined the term “calciphylaxis” in 1975 to described the complex series of physiological changes the body undergoes when responding to stress so that the body is able to fight the stressor or flee from it. Dr. Selye defined calciphylaxis as “an induced hypersensitivity in which tissues respond to various challenging agents with a sudden calcification.” He observed that it did not matter whether the stressor was chronic illness, multiple surgeries or injuries, or severe emotional trauma. In all these situations the body tissue changes were the same; the repeated activation of the fight-or-flight response caused adverse changes in the tissues themselves.

Diagram 11.1—FIBROMYALGIA:

FRONT AND BACK VIEW OF TRIGGER POINT SITES

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995

Our neuromuscular therapists at HER Place, as well as numerous bodywork therapists I have consulted over the years, all describe the same type of change in the tissues: tight, lumpy bands of muscle, hardened areas of muscle that should feel softer, a doughy feel to the tissues above the muscles, in addition to areas that cause marked pain when pressed. These changes are what Dr. Hans Selye called “calciphylaxis or calcification,” and this process causes a tightening and restriction of the tissues in the majority of patients with FMS. The connective tissues around and between muscles, called fascia, become thickened and lose their elasticity, and develop into hard, tight bands. As these bands cause more restriction to the movement of the muscle and fascia, blood flow, lymph flow, and nerve conduction all become impaired. Chemical messengers and nutrients can’t get to the muscle adequately, and metabolic breakdown products from cellular actions (often called “toxic wastes” by massage therapists) can’t be cleared away and then buildup in the tissue. The accumulation of these irritating metabolic wastes then further causes the “calcification” process, resulting in yet more tightness and pain. Over time this process of “calcification” causes the buildup of bumpy, tender areas and taut bands of muscle fibers we call trigger points because they cause pain at the site and refer pain to other parts of the body.

In addition to interrupting blood and lymph flow and the free movement of muscle and fascia, the fascia that is changed in this way also traps nerves and forms scar tissue and adhesions where the altered tissues stick to each other and don’t move freely. When nerves pass through a muscle between taut bands or between taut bands and bone, it causes persistent, unrelenting pressure on the nerve that then causes the nerve to lose its oxygen and nutrients. The nerve then can’t conduct signals properly, and this in turn produces numbness, tingling, or areas of hypersensitivity. You know this feeling when you sit on your foot and it goes to sleep—remember the painful prickles as you move your body, the pressure is off the foot, blood flow returns, and nerve sensations return in spades. Your brief episode of the foot falling asleep from pressure is similar to what goes on continually in FMS when pressure bands in the muscles compress blood flow and nerve impulse transmission. No wonder you hurt all the time. In fact, doctors evaluating FMS patients should ask the question “where don’t you hurt?” rather than “where do you hurt?” If this process continues for prolonged times, and the body is constantly in a state of hyperalertness, the myofascia forms even more of the tight ropy bands around and through the muscle, and these become contractures that further restrict movement, and the whole process continues the downward spiral of increasing pain, calcification, and restriction.

It was originally thought that stress and worry, which caused additional muscle tension, caused the symptoms of fibromyalgia. Although recent studies of people with fibromyalgia do not prove that stress itself causes FMS, stress, anxiety, and fatigue can make the pain worse. In fact, chronic pain and fatigue often cause stress and anxiety, which in turn can increase the pain and fatigue. We also know that chronic stress and pain cause suppression of the ovary hormone balance, which in turn causes sleep disruption and suppression of growth hormone and other crucial chemical messengers for pain regulation. Do you see a vicious cycle taking shape? Many times people who are caught in this tension-pain cycle turn to readily available drugs for relief: alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, painkillers, and the like. We are so accustomed to having these substances around that we often do not think of them as the drugs they are. Each one of these substances has many adverse effects on the brain chemical messengers, which collectively result in intensified pain, so again you can see why we must address all of these issues in order to make the journey out of pain. Since there are so many factors involved in aggravating and perpetuating fibromyalgia, it takes a comprehensive and integrated approach to achieve optimal reduction in pain and improvement in well-being. Taking painkillers alone will rarely provide for long-term relief and return to normal activity. In order to properly help reduce the pain of FMS, we must look at all of these pieces of the puzzle and look at how changes in one group of neurotransmitters or hormones can have a cascade effect on other tissues throughout the body—including the muscles affected by FMS.

There are also crucial hormonal connections in fibromyalgia, as I discuss further in this chapter. To being your thinking about these connections, keep in mind that there is a great deal of overlap in the chemical messengers of the brain and body involved in fibromyalgia and those neurotransmitters affected by the decline in ovary hormones during perimenopause. Stressors (surgical, life situations, or lifestyle habits) that suppress ovary function may also cause decline in ovary hormone levels. I do not find in the medical literature much mention of these overlapping effects on pain-modulation pathways and neurotransmitters, and I think there is much to explore in understanding these interconnecting pathways and functions. Although medical researchers and physicians don’t know the exact causes of fibromyalgia, they have recognized a number of different conditions and biological changes in the brain and body that are associated with it. The following are some of the basic connections.

Many people with fibromyalgia have other problems that often confuse their doctors. These include: Raynaud’s syndrome (poor circulation to the hands or toes), tension headaches, migraine headaches, dizziness, tingling and numbness, an irritable bowel (abdominal bloating with alternating diarrhea and constipation), muscle tremors, bladder spasms, and blurred vision. Current research has shown that estrogen loss or decline can result in most of these same symptoms. Later in this chapter and more in chapter 13, I will talk about the several mechanisms by which estrogen acts to preserve normal muscle and nerve function and normal blood vessel elasticity and to improve circulation. When estrogen decreases, there are subtle effects on blood vessels and blood flow to the tissues that in turn affect muscle tissue’s ability to clear metabolic wastes produced by daily activity. There are a number of ways, both direct and indirect, that decline in ovarian hormone can instigate or aggravate FMS, as we shall see. The estrogen factor may have more of a role in triggering or aggravating FMS than anyone has realized. Meanwhile, until we have clearer answers from research, if you have FMS you may find it helpful to have a comprehensive neuroendocrine evaluation to see whether hormone factors are part of the problem for you. If an unrecognized decline in your own body estrogen is causing a number of the triggers that will make FMS worse, you may feel better by adding appropriate hormone therapy to your overall FMS treatments.

There’s been a great deal of recent interest in the chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), which had been proposed to have many causes, from a persistent infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) to abnormalities in the brain centers that regulate blood pressure. EBV as a causal link in CFS has not held up under the scrutiny of further research. We have found, however, that many people who had previously been diagnosed as having CFS have been found to have FMS and their fatigue appears to be the result of the chronic sleep deprivation. Fatigue is for some people the most debilitating aspect of fibromyalgia; some women experience it as a lack of muscle endurance, while others describe the fatigue as an overall lack of energy. There are a number of potential links with the immune system that could contribute to FMS patients having a greater tendency to have more frequent infections of all types. Sleep deprivation suppresses immune system function, and so does a decline in estrogen and testosterone. Persistent overstimulation of the fight-or-flight response, for example by ongoing pain stimuli, leads to suppression of the immune system. Chronic pain is a stressor of the body, which also causes excessive production of cortisol, the stress hormone. Increased production of cortisol adds to more suppression of the body’s immune system over time. Remember that cortisol production is also increasing in response to decline in estrogen. Once again, do you see how the many pieces of the puzzle fit together with women’s hormonal changes and the high frequency of FMS in women?

I think it will become clear as you read further in this chapter that our current research findings lend more support to my proposed theory that FMS is triggered by the brain effects of declining ovarian hormones, with multiple brain-body systems, including muscle metabolism and repair, then being affected and leading to the wide variety of symptoms and persistent pain. This integrated model makes more sense to me physiologically, and approaching it from such a gender-specific point of view helps me to develop a more systematic, and physiological, approach to helping women feel better and deal constructively with the menstrual cycle hormonal shifts, and the effects on pain when hormone levels decline following tubal ligation, in the postpartum time frame or in the perimenopause and postmenopausal years. Think of FMS as an “early warning system” of many detrimental metabolic changes, and look at this as your opportunity to grab hold of your health to improve it for many years ahead. This is even truer now that women are living so much longer. The risk of many conditions like FMS increases as we lose our crucial metabolic hormones from the ovary, along with other changes such as thyroid and growth hormone. In 1900, the average age of death for women was forty-eight years. In the year 2000, only one hundred years later, we are fortunate to have average life expectancies of about eighty-eight years. Quite a change, and even more striking if you compare this with the fact that 500 years ago women died, on average, by age thirty-five. I think the most critical point for women to understand is that we want to learn what we need to know about maintaining our long-term health and reducing our long-term individual disease risks so we can live these additional thirty or forty years with the best possible quality of life and good health. Don’t just focus on treating or bearing with symptoms NOW; look at your big picture and make decisions based on what is needed for you over the long haul.

Hormonal Changes and Other Conditions Associated with FMS

• FMS more commonly occurs in women at times of significant ovarian hormone change: postpartum, after tubal ligation, after stopping long use of birth control pills, after hysterectomy, and during perimenopause and postmenopause

• Physically unfit muscles and an associated sleep disorder, with disruption in Stage IV sleep in particular

• Metabolic abnormalities: glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, hypoglycemia, elevated or suppressed cortisol

• Immunologic abnormalities such as elevated thyroid antibodies

• Vascular changes, such as Raynaud’s syndrome, hypertension

• Neuroendocrine changes: decreased insulin-like growth factor (IGF), decreased growth hormone, low serotonin (all of these are also decreased with decline in estradiol)

• Whiplash and fall-torsion injuries

• Presence of significant situational stressors (affect all of the above)

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995, revised 2000

I have reviewed many books on pain, and nowhere did I find anyone addressing the crucial ovary hormonal triggers that can cause and perpetuate pain syndromes far more common in women, such as fibromyalgia, joint pain, back pain, headaches, bladder pain, and other such problems. My own journey into the depths of chronic, debilitating pain has taught me much about these crucial hormone issues and their fundamental role in pain pathways. I know without question that I do not do well with my own muscle and nerve pain problems unless my estradiol is where is should be, and it is in healthy balance with the testosterone the ovaries also produce. But if it were just my own experience with pain, I wouldn’t be writing this. I have now treated hundreds of women with a variety of pain syndromes, and this work has shown me time and time again in working with so many women over many years that nothing has fully broken the cycle of pain until their optimal hormonal and nutritional balance is restored. These hormonal connections have been a profoundly important part of the clinical care I have incorporated for my own patients. Obviously, with a subject as complex as PAIN, one approach can’t address all the issues or provide all the answers, but I do hope to show you what to look for with the hormone connections, what tests to request from your physicians, and to show you how to begin putting all these pieces of the puzzle together in planning optimal treatment. Then you can begin to benefit from all the other modalities that are recommended in the many books on pain treatment and begin to develop an individualized program for your recovery.

As I noted at the beginning of this chapter, when we look at who gets FMS, some glaring trends pop out: 80 percent are women between the ages of thirty and fifty. Yes, FMS does occur in men and can begin in adolescence in both males and females, but worldwide statistics show that it is much less common in these groups. When I took careful histories of when the onset of FMS symptoms occurred, another glaring trend appeared: For the majority of my patients, the FMS began insidiously following some event that typically is associated with a significant decrease in ovarian hormone levels.

I have summarized my hypothesis about the most likely times in women’s lives when FMS may insidiously begin due to hormonal shifts. All of these times are when the active form of estrogen, 17-beta estradiol, is low or has fallen sharply. I think this hormonal connection is crucially significant. I am not being sexist. There simply isn’t anything else that so clearly differentiates male and female bodies. I think many women with FMS find it helpful and hopeful that I discuss these connections. Very commonly, they have already been asking these kinds of questions and have been frustrated with the lack of validation and acceptance of their observations about these connections. These potential hormonal connections simply have not been explored.

Dr. Vliet’s Hypothesis: HORMONAL CONNECTIONS

IN FMS AND COMMON TIMES OF ONSET

• Postpartum (particularly if the pregnancy was after the age of thirty-five)

• Perimenopause, associated with sleep changes

• Postmenopause, particularly if not on ERT or on suboptimal ERT

• Three to five years after tubal ligation

• Two to three years after hysterectomy (even if the ovaries were not removed)

• Presence of PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome)

• Presence of autoimmune ovarian disorders, especially if results in premature ovarian failure (POF)

• A period of sustained major stresses or illnesses that interrupts menses for several months

• Younger women with chronic anorexia-type dieting that suppresses ovary hormones

• Women who suppress ovarian function with drug or alcohol abuse

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995, revised 2000

Scattered in the recent medical literature are other clues to the existence of these ovary hormone connections beyond just my clinical experience. In one study of 100 patients cited by Jon Russell, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, the average age at which fibromyalgia was diagnosed was forty-eight, a common age of menopausal hormone decline. Dr. Russell described clinical observations that in women who developed FMS between the ages of twenty-five and forty, fully 40–50 percent of them were menopausal prior to the onset of FMS—either by surgical menopause or a premature natural menopause.

I think if we actually measured blood tests of female hormone levels, we would see an even higher percentage of menopausal women in such studies. Instead, the questions about menopause are rarely asked, and most physicians tend to just depend on the patient’s chronological age or her own knowledge of whether she is menopausal. This was one of the striking findings I noted when I did the thorough history and medical evaluation of the women admitted to our pain management program. When I actually measured hormone levels in these patients (FSH, estradiol, testosterone, and sometimes progesterone if the woman still had her ovaries), I was quite struck by how low the levels of estradiol and testosterone were compared to the expected normal range for a woman in her twenties through early forties. One of the treatment approaches I used, in combination with the other therapies we incorporated in our overall approach to pain management, was restoring the woman’s hormonal balance to normal levels. I was pleasantly surprised to find that the improvements in FMS occurred much more rapidly with optimal hormonal therapy added to the overall therapeutic program.

I must caution that at this time, there is simply no controlled study to determine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship with female hormones and FMS or whether this observed connection is simply an association of the phenomena of pain/FMS and menopausal hormone changes. Even if there is only an association, it certainly is important enough to at least include in our medical assessments, so that if there are hormonal imbalances, these can be properly addressed in designing an individualized treatment plan. Helping women find an optimal hormonal balance, in my experience, has frequently meant they could reduce the amount of pain medication.

Ria is an example of the significant improvements that can happen in women with fibromyalgia when hormonal balance is addressed. She is now fifty-three, and had been injured in an automobile accident about eight years ago. Following the accident she developed a severe pain syndrome called reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), which produces a burning, excruciating pain difficult to relieve even with narcotic medication. She underwent extensive evaluation and treatment by physicians very experienced in managing RSD. Two years later, when she went through menopause, she was started on a standard cyclic hormone therapy with conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin), and progestin (Provera). Her menopausal hot flashes stopped, and she was sleeping better. She felt better getting these concerns addressed, even though the RSD continued to cause pain.

Over the past five years, however, she developed a new and different type of pain, which she described as clearly distinct from the burning pain of RSD. She described the new pain as dull, aching pain in the muscles of her arms, hands, legs, and back associated with intermittent sharper pains along with stiffness in her joints. This pain had gotten so much worse over the last year that she now had difficulty walking and had to begin using a cane. Understandably, she was becoming more and more discouraged about her health. She had observed that this new pain developed after menopause and initiating hormone therapy, so it seemed a reasonable question to ask her doctors if there could be a possible hormonal connection to produce this new type of pain. She did ask several of her doctors whether it was possible to check hormone levels to see if she was taking the right amount. Each time she asked, she was told that it couldn’t have anything to do with her hormones. She was told that she had fibromyalgia. She met the criteria I described above for FMS, so this seemed a reasonable diagnosis. She was further told that there was no way to do any tests for hormone levels, and the hormone dose was fine because she wasn’t having any more hot flashes. Her doctors recommended physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medication added to the pain medicine she had been taking for the RSD. She continued to have more and more difficulty with both the RSD and this new pain problem.

Ria’s friend told her about the work I was doing with women with FMS. Ria scheduled an appointment and had her hormone levels checked along with other important blood tests. In addition to the new pain syndrome, Ria was also having problems with weight gain, loss of energy, diminished libido, restless sleep, and said she just didn’t feel “like my old self.” Ria and I spent an hour going over all that she had been through, her lab results, and the options I thought could help her. Even though she was taking estrogen, her FSH was still too high in the menopausal range, and her estradiol level was markedly low (less than 30 pg/ml). Her hormone therapy was clearly not giving adequate levels of the estrogen she most needed replenished.

Since she had experienced breast enlargement on the conjugated equine estrogen, as well as the worsening pain symptoms, I did not want to just increase the dose. I suggested she change to the native human form of estradiol, which I thought would give better pain relief. I also recommended that she dissolve the estradiol under her tongue (instead of swallowing the oral tablet) because I knew that would give a better ratio of estradiol (E2) to estrone (E1), which I thought would help reduce the breast enlargement and weight gain she had experienced, and still provide optimal levels of estradiol to help diminish her symptoms. At this time, Estrace is the only commercial tablet form of estradiol that can be dissolved under the tongue and effectively absorbed. (Note: This does not work with other brands or with the generic preparations of 17-beta estradiol.) After I had explained this rationale, she decided to try Estrace. I did not give her any particular suggestions about the change other than to say I thought this estrogen would help her feel better, improve her sleep more effectively, and perhaps help with the overall pain she had been experiencing.

At her first follow-up visit about two months later, she said she felt more energetic, was sleeping well again, and had gone down a bra size. She reported that she did not feel as bloated, her joints were not as swollen and painful, and she felt she had a better range of movement. She was surprised to see that over the two months, her overall pain seemed less intense. She asked if I thought that could be related to the hormones, and I told her that this was the response I had seen in most of my patients, and I thought it did have an important hormonal connection. We agreed that she would continue the same amount of Estrace, and she would come back in another two months to be rechecked.

Four months later she returned for follow-up, and I hardly recognized her when she walked in the door. She looked happy and cheerful, walked more quickly and fluidly, did not need her cane to lean on (although she still carried it), and had more normal overall body movements. I commented that I had not seen her in such a long time, I had begun to wonder if she had given up on the hormonal approaches we were trying. She laughed and said,

No, I was just feeling so much better, I forgot to call and make an appointment! About two weeks after my last appointment, I got up one morning and realized that my joint and muscle pain was completely gone. At first, I was afraid to believe it, but after a few more weeks, I realized the resolution of that part of my pain was very real, and it has not come back. The RSD pain is still there, but I can cope with that now that I don’t have my joints and muscles hurting so bad all the time. I am even using less pain medicine for the RSD now. Getting off the Premarin and Provera and having my estrogen where it should be made such a difference in my pain, I can’t believe how much better I feel now.

The normal premenopausal balance of estradiol in a woman’s body has a number of effects on nerves and chemical messengers to reduce pain sensations, particularly chronic pain. Other underlying triggering mechanisms in fibromyalgia can be metabolic, neuroendocrine changes. These chemical changes in the brain and body would then affect the way peripheral nerve fibers function and trigger increases in the painful spasms that set up the vicious cycle of fibromyalgia. An example of this mechanism is the way declining female hormones, particularly estradiol from the ovary, cause heightened sensitivity of nerve endings to pain and other stimuli. Decreases in estradiol also cause decreases in serotonin production, so there are several possible ways for hormone change to trigger the variety of pain and aching with FMS. In this way, FMS may be dysfunction of the nerve fibers, with changes or abnormalities occurring in the way nerves to the body transmit pain signals. The stress of chronic pain on the body can also cause further decline in ovarian hormone production, so one situation aggravates the other.

The estradiol receptors heavily concentrated in the limbic system areas of the brain provide another connecting link between the chronic pain of FMS and the hormonal changes leading up to menopause. The nerve pathways carrying chronic pain stimuli from the body to the brain travel through the limbic system centers, which regulate mood and sleep. You can imagine how the constant day-to-day presence of pain signals can then disrupt normal sleep regulation and contribute to depressed, irritable moods through effects on the limbic system. Remember that I talked in chapter 5 about the way in which decreases in estradiol can disrupt the limbic system pathways and cause irritable mood and fragmented sleep. Now we see that both chronic pain stimuli and decreases in estrogen have similar effects on the same brain centers. Acute pain pathways bypass the limbic system as they travel from the body to the higher brain centers, so when you experience an acute injury producing pain, it is not likely to cause the same types of sleep and mood upsets that we see in people who have a chronic pain syndrome.

What can you do to check these connections for yourself if you have FMS? I suggest asking your physician to check hormone levels, so you can then determine whether adding the hormones might be helpful for you. I discuss these connections with my patients, and then measure FSH, estradiol, and testosterone blood levels. If the results show low estradiol levels, and she wants to try it, I prescribe estradiol alone or possibly with low-dose natural testosterone. If she has a uterus and needs to use a progestin, I try not to use a synthetic progestin (such as Provera, Cyrin, Amen, or Aygestin) unless there is no other choice to control difficult bleeding problems. I have found the synthetic progestins seem to make fibromyalgia pain worse. One possible explanation for this observation is that the synthetic progestins actually block estrogen binding at the estradiol receptors in the brain, which will then reduce estrogen’s beneficial effects on pain. I have also found that synthetic estrogens (Ogen), the mixed animal-derived estrogens (Premarin, PremPro) or the esterified mixed plant-derived estrogens (Estratab, Cenestin, Menest) also appear to aggravate FMS symptoms. For women with FMS who may benefit from hormone therapy, I use only the bioidentical human form of 17-beta estradiol and make certain it reaches optimal estradiol blood levels. If you are having difficulty getting someone to check your hormone levels, you may want to schedule a consultation at a specialty center like our HER Place programs, where the hormone issues will be addressed as part of a comprehensive evaluation.

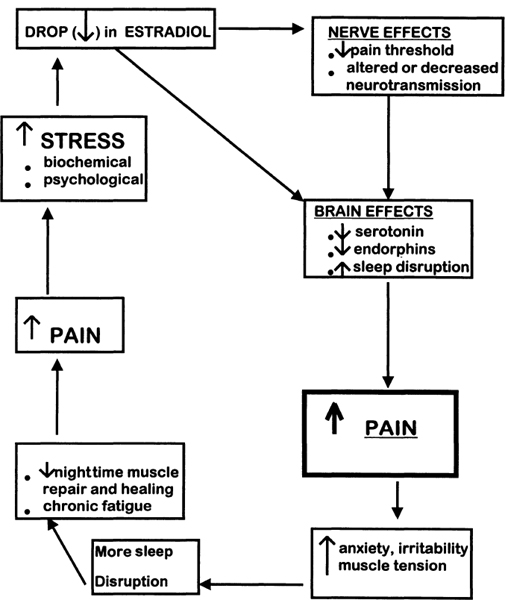

DR. VLIET’S MODEL: ESTRADIOL EFFECTS ON CHRONIC PAIN

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995, revised 2000

There is a great deal of overlap in the chemical messengers of the brain and body involved in fibromyalgia and those neurotransmitters affected by the decline in ovary hormones during perimenopause. Decline in ovary hormone levels may also be caused by stressors (surgical, life situations, or lifestyle habits) that suppress ovary function. I do not find in the medical literature much mention of these overlapping effects on pain-modulation pathways and neurotransmitters, and I think there is much to explore in understanding these interconnecting pathways and functions. The list below shows the most important of the known neurotransmitters involved in regulating pain; since there are so many of these, you can begin to see how many different disorders can contribute to making FMS pain worse. I have already mentioned that hypothyroidism is many times more common in women than men, and this hormonal disturbance may be another overlooked factor in FMS. Careful and complete evaluation of thyroid function is another crucial hormone system to be checked. In FMS patients, I think it is particularly important to also check antithyroid antibody levels and the levels of the free T3 and free T4 thyroid hormones. Autoimmune thyroid disorders may cause significant muscle pain in the early stages of the disorder, even if TSH is normal. These antibody tests are more sensitive indicators of thyroid dysfunction that may be contributing to FMS pain.

Key Neurotransmitters and Hormones Involved in FMS and Pain

• Serotonin (pain-relieving chemical messenger)

• Tryptophan (building block for serotonin found in many foods)

• Norepinephrine (NE) and Epinephrine (EPI)

• Dopamine

• Substance P (pain-inducing chemical found in higher-than-normal levels in FMS)

• Monoamine oxidase (enzyme that breaks down dopamine, nor-epinephrine, and epinephrine)

• Endorphins

• Thyroid hormone

• Ovarian hormones (some researchers say this is still open to question)

• Adrenal steroids

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995

Although medical researchers and physicians don’t know the exact causes of fibromyalgia, they have recognized a number of different conditions and biological changes in the brain and body that are associated with it. In order to properly help patients with FMS, we must look at these pieces of the puzzle and look at how changes in one group of neurotransmitters or hormones can have a cascade effect on other tissues throughout the body—including the muscles affected by FMS. I have summarized some of the conditions that are found to be present with fibromyalgia in the table entitled “Hormonal Changes and Other Conditions Associated with FMS” earlier in this chapter.

While it is not yet known whether unfit muscles are the cause or the result of FMS, there is increasing evidence that people with fibromyalgia have unfit or poorly developed muscles. Women typically lose muscle mass as they age, so there is less reserve muscle tissue than in earlier years. As the cycle of pain contributes to more inactivity, the muscles become even more unfit and atrophied, which makes them more likely to be injured or damaged with exercise. This is a vicious cycle of more pain causes more inactivity causes more loss of muscle causes more pain causes more inactivity causes more loss of muscle. I think you get the picture. Over time, underuse of your muscles leads to a negative, detraining effect, which results in even more unfit muscles that are more likely to become injured or damaged from exercise. This sort of muscle damage is commonly called microtrauma, and it causes delayed muscle pain and fatigue that may not appear until a day or two after exercising and may last six to seven days. The pain and fatigue make us postpone further physical activity until they are gone and our energy has been restored, thereby again contributing to the vicious cycle.

It is common for anyone to experience the effects of microtrauma after too much physical activity. That’s the kind of pain a weekend athlete will experience on Monday or Tuesday. Yet for people who have unfit muscles, these problems may develop after even slight exertion, such as routine day-to-day activities. Microtrauma may also result from other kinds of muscle overuse or injury: poor posture, sitting hunched over at a computer or a desk all day; damage caused by a blow or a fall; or the kind of torsion damage that occurs in a whiplash injury. In the normal person, muscles repair and restore themselves from microtrauma during stage IV sleep each night. But in FMS patients (and in women who have decreasing ovarian estrogen), the deep stages of sleep are disrupted, so normal muscle growth and repair during sleep does not occur.

In addition, there is an important chemical for muscle growth and repair, called Somatomedin-C, released by the liver when the liver is stimulated by growth hormone (GH). Eighty percent of our daily amount of GH is secreted during the deep stages of sleep, which, in FMS patients, are markedly diminished or missing altogether. It may well be, then, that the tendency toward muscle fatigue and weakness may be due to the loss of deep sleep stages, which in turn decreases the normal production of GH. Also keep in mind what I have said about the role of serotonin: This important chemical messenger in the brain is one of the crucial regulators of sleep, and serotonin production is typically also low in FMS patients.

If you think about what I have said about the role of unfit muscles in causing and/or maintaining FMS, you will see why beginning an exercise program under the supervision of a physical therapist is one of the cornerstones of effective treatment. It is crucial to break out of this vicious cycle and retrain your muscles. Patients who diligently follow a graded exercise program have a significantly better, and more rapid, recovery, because they are rebuilding and strengthening muscle tissue. A gradual increase in aerobic exercise provides better blood flow to the muscles, which brings new oxygen and fuel and takes away the waste products (particularly lactic acid), that otherwise would build up and contribute to more pain.

Almost all patients with fibromyalgia have a major sleep disturbance as part of the clinical findings. It is not yet known whether the sleep disorder causes FMS or whether the chronic pain produces the sleep disruption. At the point a person has FMS, sleep is disturbed, causing a worsening of the FMS and pain. I prefer to view it as an integrated problem and try to identify ways of constructively breaking the cycle. The clue to the sleep disorder connection in FMS has been determined from sleep laboratory studies in which patients sleep in a “bedroom” laboratory, with monitors keeping track of brain wave patterns, muscle activity, eye movements, heart rate, breathing rate, oxygen concentration in the blood, and a number of other objective measures of the quantity and quality of sleep. Patients with fibromyalgia typically show a marked degree of fragmented sleep, with the deepest or most restful stage of sleep (stage IV) disturbed or interrupted, and more waking episodes at night. Physicians refer to this abnormal pattern as “alpha intrusion of stage IV sleep.” Remember that I have also talked about the sleep disturbances that are caused by declining estrogen levels affecting the brain centers that regulate sleep. Here we see another hormonal connection that may aggravate, or help to set up the conditions for, FMS: Decreased estrogen makes nerve endings more susceptible to pain and disrupts sleep; the pain of fibromyalgia disrupts sleep; the stress to the body of continued sleep loss causes more pain and more decrease in ovary hormone production. See how it all fits together?

Sleep disturbances may be a significant reason that women with FMS describe having such low energy levels and feelings of marked fatigue. A decline in hormone levels such as estrogen and particularly testosterone may be another reason for the low energy levels. There is also evidence that both sleep problems and decreased ovarian hormones can lead to increased muscle pain. When normal, healthy volunteers were stressed by artificial disturbance of their stage IV sleep, they developed pain and soreness in their muscles very similar to that seen in FMS. This combination of pain and fatigue then often limits physical activity and endurance. The resulting lack of physical exercise can contribute to the unfit muscles that are more susceptible to further pain, and the FMS symptoms continue to get worse. As I mentioned above, stage IV sleep is important in repairing tissue damage and feeling physically and psychologically rested when you wake up. So if stage IV sleep is reduced, it can contribute to many of the other symptoms of FMS.

If you have trouble going to sleep, you may find yourself turning to alcohol, thinking it will help you sleep better. The problem with using alcohol, especially for FMS patients, is that alcohol contributes to more fragmentation in sleep and more loss of stage IV sleep. Alcohol used on a regular basis has several other effects that make FMS worse: (1) alcohol depresses the central nervous system and aggravates the biological depression that occurs in about 90 percent of patients with FMS; (2) heavy alcohol use further suppresses ovarian function; (3) alcohol diminishes production of endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers; (4) when alcohol is wearing off, it creates an adrenalin rebound that leads to increased muscle tension and pain; (5) alcohol is toxic to muscle fibers. For these reasons, I urge you to avoid drinking alcohol on a regular basis if you have FMS. Nicotine (cigarettes) and caffeine (coffee, tea, soda, etc.) are other common substances that stimulate the adrenaline system, add to muscle tension (and pain), and further aggravate fragmented sleep and reduced stage IV sleep.

I urge my patients with FMS to reduce or eliminate intake not only of alcohol but also other drugs like caffeine, nicotine, over-the-counter DHEA and stimulants found in weight-loss preparations, which may all make chronic pain worse. Take a look at the next diagram, which shows how many different factors are related to one another and create more pain. This may give you some ideas of ways you can begin to make healthy habit changes that will contribute to reducing the chronic pain. At the same time, if you take into account the hormonal factors that are involved in modulating pain sensations, you can begin to see how all these pieces of the puzzle are connected through similar effects on serotonin, endorphins, and other body messenger systems.

There are a variety of medications useful in alleviating the symptoms of FMS, including some hormonal therapies. I would like to point out that many of the pain medications we use for acute pain treatment could actually be detrimental when working with chronic pain. Acute and chronic pain are very different, both in their nerve pathways as I mentioned earlier, and in the biochemical and psychological changes they produce. The best way I can explain the difference between acute and chronic pain is to use the analogy of a loud fire alarm in a building. The fire alarm goes off, gets your attention, and you move out of the building rapidly to avoid harm. Acute pain is the body’s alarm that something has gone seriously wrong and needs your attention now. Acute pain triggers bursts of adrenaline, the pain-relieving endorphins, and other chemical messengers to prepare you to deal with the emergency. Narcotics and other potent analgesics are very helpful in relieving acute pain by a number of different mechanisms.

Chronic pain, on the other hand, is like a fire alarm without a cutoff switch. The persistent jarring sound of a fire alarm that won’t stop is one of the most intrusive and penetrating sounds I have encountered. I once had to handle a patient emergency with the hospital fire alarm ringing persistently in the background. They couldn’t get the fire alarm turned off. I thought the sound would literally drive me nuts! This is also very much what your mind-body-spirit goes through with chronic pain: Pain alarms go off continually without stopping and intrude on every dimension of one’s being. The spirit feels beaten down, the mind is overwhelmed, and the body feels like it hurts everywhere. In chronic pain, the excessive activity of the “alarm system” contributes to an imbalance in the adrenaline system (too much) and the serotonin-endorphin system (too little). Your brain and body actually become depleted of the pain-relieving endorphins, which then reduces the effectiveness of the medications we use for acute pain (such as those listed below). Sedatives, or sleeping pills, taken longer than about two weeks will cause disruption in the deep stages III and IV sleep, and alter REM sleep. These adverse effects on the sleep cycle end up making FMS sleep disorder and pain worse. If medication is needed to help improve sleep for women with FMS, I prefer to use a serotonin-boosting one such as Zoloft, Prozac, Celexa, Desyrel, (trazodone), or possibly Buspar. The serotonin-boosting medications are not sleeping pills. They do not depress the brain as sleeping pills do, so they are safer, do not cause addiction, and have fewer side effects. These medications are more specific for the deficiency of serotonin, which is thought to be a major underlying factor in FMS. While none of these (except trazodone) are directly sedating, each works indirectly to restore sleep stages back to normal and to also decrease pain by enhancing the activity of serotonin and improving the serotonin-norepinephrine balance. Improving the quality of your sleep is a major part of effective treatment for FMS.

A different class of muscle-relaxant medication, cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), is also helpful for some patients. It appears to help relax tense muscles and is also significantly sedating, so for many people it also improves sleep. The older tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline (Elavil), imipramine (Tofranil), doxepin (Sinequan), and others have been prescribed in the past to promote stage IV sleep. I generally don’t recommend using these older tricyclic medications because they have too many side effects, in particular daytime drowsiness and lethargy. One common side effect of all the tricyclic antidepressants is that they cause weight gain in a large percentage of patients. Needless to say, this bothers women immensely. Since we now have the more selective serotonin-augmenting options available, I find the SSRIs work better with fewer unwanted side effects. If you are taking one of the tricyclic antidepressants and are having unpleasant side effects, talk with your physician about changing to one of the selective serotonin-boosting medications. Corticosteroids are sometimes used for pain relief in FMS, but they do not seem to be that effective for stiffness and fatigue. In addition, these drugs actually have marked weight gain effects and potentially serious side effects. I do not recommend using corticosteroids in FMS unless you have been carefully evaluated by a rheumatologist, and you have documented low cortisol levels or there is a specific inflammatory component that is being treated by the corticosteroids.

Pain Medications to Watch Out For

• narcotics (morphine, Demerol, Vicodin, Tylox, codeine, and others): tend to cause depression, fatigue, decreased memory, and concentration when taken regularly on a daily basis.

• excessive amounts of acetaminophen (Tylenol and generics): taken in large amounts on a regular basis, acetaminophen can lead to liver and kidney toxicity.

• sleeping pills (Restoril, Dalmane, Halcion, Valium, Serax, Ambien, Ativan, Klonopin): alter the normal stages of sleep when taken on a nightly basis for long periods of time. In addition, they are habit-forming, and if you have been taking them for more than a week or two, you will need a gradual tapering when it is time to stop them.

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995, revised 2000

Fibromyalgia is one of those conditions whose “treatment” is best described as helping people manage their symptoms to achieve relief and improved body-mind function. There really isn’t a cure for FMS in the sense that physicians could prescribe a medication or other form of treatment that would make all the symptoms and pain go away forever. It can best be compared to a disease like diabetes, in which the symptoms can be controlled and reduced with a “multiple modalities” approach. The destructive effects of FMS pain and progression of muscle deterioration can be dramatically reduced by minimizing lifestyle factors that aggravate pain. There are also nonaddictive medications that can be used safely for an extended period of time to rebalance body chemistry and help you maintain productivity and pursue fairly normal life activities. It is really important that you plan to work with a team of health professionals over a period of time to decrease the symptoms of FMS. This is not a condition that can be treated quickly in three or four office visits with a physician. It is going to involve your active participation in a variety of therapeutic modalities and your commitment to a maintenance program of aerobic, strength, and flexibility exercises on a regular basis. I find that most patients with FMS respond best to a combined approach, which ideally would include achieving optimal hormonal balance, appropriate other medication for pain relief and sleep improvement, and these would be supplemented with one or more of the mind-body therapies such as physical therapy, neuromuscular-massage therapy, cranio-sacral therapy, acupuncture, TENS, biofeedback or relaxation training, vibrational medicine and sound therapy, supportive psychotherapy, stress management, regular exercise, healthy eating habits, and vitamin-mineral supplements. I have successfully used a combination of these approaches for my own recovery following my back surgeries, and I have also prescribed these techniques for my patients who suffer with fibromyalgia and other forms of chronic pain.

It is critical to make sure you have adequate intake of certain vitamins and minerals that are important in helping our body make normal muscle tissue and regulate nerve function and pain pathways. I want to mention a few key vitamins and minerals that you will want to include each day, in addition to your multivitamin, calcium, and vitamin D.

Magnesium is especially crucial for nerve cell conduction, muscle contraction, muscle repair, pain regulation, bone building, and it also has a strong independent role in regulating blood pressure. Magnesium’s role to decrease blood pressure and prevent seizures is so well known that it is used in an injectable form in the treatment of eclampsia (toxemia) of pregnancy and a variety of heart diseases. It appears to be an important factor in preventing migraine headaches and heart attacks, probably because it helps prevent spasms of the blood vessels throughout the body, but especially in the coronary (heart) arteries.

Magnesium helps maintain normal structure and contraction strength of the heart muscle itself as well as other muscle tissue in the body. In the brain, magnesium is a cofactor in the production of the important pain and mood-regulating chemical messengers such as dopamine. This is one of several reasons magnesium is useful in the treatment of PMS, as well as FMS. Several B vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin, and pyridoxine) require magnesium as a catalyst for the chemical reactions that make these vitamins biologically active in the body. Magnesium also is a cofactor for the chemical reactions for using amino acids to build protein for growth and repair of muscles and other tissues. The pathways for the body to make its energy compounds are also dependent upon magnesium.

In addition to all these, newer research has shown that magnesium plays a key role in helping to block overactivity of the NMDA receptor that is an important player in pain regulation. This receptor complex serves to spread and augment the pain sensations in persistent pain syndromes. Magnesium has been shown to act as a block at this receptor, helping to prevent the calcium channel from opening and causing “hyperexcitable” nerve cells that become overactive and intensify pain signals. Zinc is also important in this blocking process at the NMDA receptor, and the two minerals have slightly different functions to help keep the nerve cells from firing excessively in response to the excitatory amino acids (EAA) like glutamate, aspartate, and glycine. Conditions of low magnesium make the nerve cells more excitable in the presence of EAA, leading to increased pain, increased muscle spasm, and more tissue damage over time. These adverse effects are magnified under conditions when the neurons also have low energy stores of critical nutrients like glucose and oxygen. That’s why it’s so important in conditions like FMS to eat regularly and keep blood sugar levels steady, maintain optimal intake of magnesium and zinc, as well as practice regular deep breathing to improve oxygen flow to the tissues. Magnesium also is important in preventing free-radical damage to cells. When magnesium is low, not only do we lose this protective effect, but also the low magnesium is itself a trigger that generates more free radicals. Again, we have a double whammy that can have a serious cumulative effect in people with FMS.

Since magnesium is involved in so many critical chemical reactions to make energy, use oxygen, maintain “calm” nerve cells, prevent free-radical damage, build muscle, and make the chemical messengers for pain and sleep regulation, it is an absolutely essential mineral to take regularly as part of your supplements, in addition to seeing that you have good dietary sources, such as eggs, legumes, and peanuts. Estrogen enhances magnesium uptake and utilization by the body’s soft tissues and by bone, which is another factor helping women have lower rates of heart disease and bone loss if they are estrogen complete. With decline in estrogen, we also lose our ability to absorb and use magnesium optimally, which in turn aggravates the problems that come with loss of estrogen: high blood pressure, greater bone loss, and increased heart disease. But there is a flip side of this coin that you need to keep in mind: If your magnesium intake is too low and you are on supplemental estrogen, the estrogen shifts more of the magnesium into the soft tissues and bone, with a resulting decrease in serum magnesium. This in turn causes a shift in the calcium-to-magnesium ratio, favoring coagulation, and could increase the risk of clot formation. If you are taking calcium and are on estrogen, you need to be certain that you also get enough magnesium each day. But what about getting too much magnesium? Excess magnesium fairly quickly causes diarrhea, so this is a reliable indicator that you are getting more than you need and should cut back on the amount you are taking.

Zinc is a helper for some twenty enzymes and is involved in DNA and protein synthesis, immune reactions, the action of insulin, utilization of vitamin A, the healing of wounds, and it forms part of the structure of bone. It is also a part of the “gatekeeper” minerals at the NMDA receptor involved in pain regulation and serves to help dampen down the activity of this receptor system, thereby helping to decrease the spread of pain sensations. Zinc is as important as protein in the normal processes of growth and maintenance of body tissue. Animal foods are a good source of zinc. Plant sources include whole grains. The recommended intake is 15 mg per day for the average adult. Generally, two small servings of lean animal protein per day are sufficient. Vegetarians should double check that they are getting adequate intake. If you take Zinc supplements, be careful not to take too much, since excess doses cause other problems.

Absorption of zinc depends on adequate dietary intake of tryptophan and B6. A deficiency of either will impair zinc absorption. In the exocrine pancreas the metabolism of tryptophan produces picolinic acid, and this process has a step that requires pyridoxine (B6) as a cofactor for the enzyme to work properly. Picolinic acid is then secreted from the pancreas into the intestinal tract, where it forms a complex with zinc from the foods we eat. This complex of zinc and picolinic acid facilitates the passage of zinc through the mucosa lining the intestinal tract, where it is then taken up into the bloodstream for delivery to the tissues. The quantity of zinc that is carried across the mucosal membranes directly depends on the availability of picolinic acid, which in turn depends on the level of dietary tryptophan along with pyridoxine (B6). A pancreatic extract, Viokase, has been found to contain picolinic acid, as does human breastmilk (but not cow’s milk). Studies have shown that picolinic acid added to rat diets promoted growth and increased absorption-retention of dietary zinc. Rats fed diets low in protein sources of tryptophan absorbed significantly less zinc than when dietary tryptophan was adequate. Supplementing with chromium piccolinate can be useful to help keep blood glucose more stable throughout the day and aid in zinc absorption. Current studies have shown that 200 mcg daily is reasonable and has not shown any adverse effects. Higher doses can be toxic, so don’t over do it. If you are overweight and have shown clinical symptoms of glucose intolerance, chromium piccolinate with zinc may be helpful as an addition to a properly balanced diet.

Manganese is another mineral needed for the formation of important amine neurotransmitters involved in the regulation of pain and mood. It is essential for normal pituitary function and thereby indirectly regulates is one of the regulatory helpers for hormone production. Another example of its importance in hormone production is that manganese is essential to the process of forming T4 (thyroxine) by the thyroid gland. It also is involved in a number of enzyme pathways needed for the utilization of the B vitamins, vitamin E, and vitamin C, as well as the pathways of energy metabolism, glucose regulation, and immune function. Manganese is also a component of the antioxidant enzyme SOD, or superoxide dismutase, that controls superoxide free radicals formed in the body during cellular metabolism. SOD helps prevent the buildup of excess superoxide radicals that cause cell damage.

Aerobic Exercise is another important component of a well-balanced, integrated approach to effective treatment in FMS. Recent studies have shown that regular aerobic exercise can improve energy and decrease chronic pain to provide you with a sustained benefit in many aspects of your health. I find that many women with fibromyalgia are reluctant to exercise because they are afraid it will cause more pain. I suggest having a physical therapist or an exercise physiologist experienced in working with FMS evaluate you and design an exercise program that starts out slowly and gradually becomes more challenging as your strength and endurance increase. If the exercise regimen is gradual, and tailored to your individual needs, there is little risk of increased pain or muscle microtrauma. Your body will eventually be able to accept more vigorous exercise routines. Consult your physician before beginning any aerobic activities, and ask for a referral to a physical therapist to teach you appropriate stretching exercises and help you get started on an exercise program.

I recommend nonimpact aerobic exercises for FMS patients to avoid aggravating pain or stiffness. These include brisk walking, swimming, water walking, aqua-aerobics, and using a stationary bicycle or cross-country ski machine. I would suggest that you avoid activities such as jogging, aerobic dancing, “step” aerobics classes, and racquet sports until you have reached a good overall level of physical fitness and your physical therapist feels you are ready to graduate to more strenuous activities. It is especially helpful to do your exercise program in a pool, because this reduces the wear and tear on muscles weakened by FMS. A number of hospitals, YMCAs, Jewish Community Centers (JCC), and fitness clubs now have pool classes available. Remember to gently stretch all your major muscle groups for about five minutes both before and after you exercise. Stretching helps reduce the chance of muscle injury, but make sure that you stay within your body’s limits and don’t overstretch, since this will cause more injury. Bouncing movements when you stretch also cause more muscle injury and are not recommended. Stretching by Bob Anderson is an excellent book I have used for years to provide safe and effective stretching exercises.

Ergonomic Factors. The types of activities you do at home and at work may be additional factors adding to the FMS pain. For example, if you sit slumped over a desk all day, by the end of the day the pain may have gotten worse because of bad posture. I think it can be very helpful to have a posture analysis and recommendations about proper body position for various activities. Your physical therapist is a good resource to help you with these aspects. Many of us are not aware of the abnormal body positions we use daily, which are often the result of compensating for pain. One physical therapist I frequently work with in treating FMS patients does a videotape of the person’s posture and movements prior to the session and then again after the treatment. This helps the person to see clearly posture and movement differences and improvements so she is better able to maintain them at home.

Some physical therapists are able to help you assess your home and work environment for body positions that aggravate FMS. It may be helpful to change physical arrangements in your environment to reduce such pain triggers. For example, pain in the arms, neck, or shoulders can be brought on by long hours of typing or working at a computer. If so, you may be able to reduce pain by raising the height of your typewriter or computer table and by learning the acupressure points to use yourself to relieve muscle spasm. Many people are unaware that a wrong mattress for your body needs can put your back into uncomfortable positions overnight, leading to morning stiffness and pain. You may want to have someone take pictures of you lying on your mattress, to check your spinal alignment with your physical therapist. If driving is a problem, try using a backrest or changing the way you sit. I have found that certain makes of cars have seat back angles that I cannot use without aggravating my back problems, so I am particularly careful about which cars I rent when I travel. Being aware of these day-to-day details can help improve FMS pain immensely.

Relieving Stress and Depression. Worries, fears, anger, and other intense emotions may also worsen pain and fatigue. Feelings are sometimes harder to identify than our physical symptoms, yet they may definitely intensify symptoms. Look for appropriate support resources to discuss stresses in your life. I am not saying that FMS is a psychogenic disorder. Everyone has stresses, and everyone reacts to stress in different ways. Always keep in mind what I have been saying throughout this book:

Your mind and brain and body are all connected! More stress causes more muscle tension and more pain!

Thoughts and feelings produce chemical changes in the pain-and mood-regulating chemicals, just like physical pain stimuli produce chemical changes in the body. You may benefit from psychotherapy to help you express uncomfortable or distressing feelings and to help you cope more effectively with situational stresses. Many psychiatrists and psychologists specialize in helping people with chronic pain and may also have experience in teaching self-hypnosis and relaxation skills that reduce stress and tension aggravating pain and fatigue. I typically teach patients techniques such as visual imagery, autogenic conditioning, and progressive muscle relaxation. You may also find it helpful to take a stress management class.

About 80 to 90 percent of patients with chronic pain will develop a biological depression due to the persistent pain. Recent studies have shown that chronic pain patients are not typically depressed people who express depression as physical pain; they have ongoing physical pain (even when the cause is unclear), which alters brain-body chemical messengers and produces the depression. In such situations, specific medications, such as the serotonin-boosting ones mentioned in earlier chapters, are needed to alleviate the depression. Psychotherapy can be helpful but is usually not enough to treat a biological depression. A psychiatrist is a physician trained in both medication use and psychotherapy, and he/she can be an excellent resource to evaluate your integrated needs for medication and/or psychotherapy. You may then decide to see a psychologist or therapist for ongoing individual or family sessions, but it is better to have your evaluation done by a psychiatrist who knows how to identify and treat biological depression and also understands the physical connections between chronic pain and depression.

In order for any of these treatment approaches to be effective, you must be an active partner in the process. This includes becoming knowledgeable about fibromyalgia. You may find it valuable to attend educational lectures on FMS given by doctors and self-help groups in your community. It can be well worth your time and effort to find a physician who is knowledgeable about fibromyalgia and with whom you feel comfortable. Keep in mind that people respond differently to various treatments, so what works for your friend may or may not work for you. It usually takes a trial of several different kinds of treatment before you find an effective combination. If you are working on developing a hormone “recipe” to suit your needs, it may take several months of working with various options to come up with the one that is best for you. Do be prepared to invest the time it takes to find the right combination. I also encourage you to be prepared to modify some aspects of your lifestyle, to expect flare-ups to occur from time to time, and to make time for exercise and practicing relaxation skills. If you invest the time, energy, and effort in carrying out your personalized pain-management program, you will be more likely to achieve positive results.

Fibromyalgia syndrome is now the subject of carefully controlled research studies in many of the leading universities of North America. The leading question facing investigators is whether fibromyalgia represents a true disease process, and what are the metabolic-immune and other abnormalities that cause it. Another major focus of research clearly needs to be on the role of female hormonal decline in triggering and perpetuating the debilitating symptoms of FMS. The results of this research will have a major bearing on whether fibromyalgia can be controlled with new drugs and whether there will need to be more emphasis on assessing and adjusting hormone levels in women who suffer from FMS. Even with use of hormone and medication therapies, I think we will always need to include the complementary approaches I outlined for stress reduction, improved quality of sleep, reduced pain, and maintenance of physical fitness as cornerstone strategies for coping with fibromyalgia. Don’t give up hope. There are lots of helpful options available.

Listen to the words of this fibromyalgia sufferer, whose estradiol had been seriously low:

I am feeling really good now. I think we have hit a good combination, and I feel like I have come such a long way. When I saw you in April and increased the estrogen, that worked really well for me. It seemed like everytime we increased it, I got better. It has helped my sleep tremendously—within a couple of weeks I was sleeping better. I was taking the Prozac for a while and I decided in August to wean myself off it and see what happened. I didn’t feel as tired during the day after I got off it, even though I know that it helped me at first. The fluctuations in the weather and barometric pressure still affect me. One little miracle happened—I took the Micronor for 12 days, and I can actually say I was pain free for that time. When I take it, I got my period about three days after I finished it. The flow was a little heavier and I had a little more cramps, but I did OK on it—not like the problems I had with the other progesterone we had tried. It seemed to actually enhance the effects of the estrogen on the pain. I am really pleased with how much better I feel! The hormones have really made a difference.

Following her own observations that the Micronor seemed to have actually helped decrease her pain, she asked about taking Micronor daily. I told her I thought this would be fine, since she had no medical reasons not to do this. The main reason I had suggested a cyclic regimen was to minimize the progestin use because she had such difficulty taking prior prescriptions of progesterone. But since she was doing so well with the Micronor and the change in estradiol, the daily progestin is a very good solution to preventing cramps, bleeding, and hyperplasia.

So once again, we find that in listening to women’s wisdom and working as partners in the healing process, we can find ways to reduce much of the pain and many of the problems that women experience with flares in fibromyalgia pain that occur with hormone imbalance. Fibromyalgia doesn’t have to destroy your life. It is possible to recover your zest, energy, and vitality if you focus on addressing all these pieces of the pain puzzle.