Listen to the voices of these women who have called our center for a medical consultation. Each of these women had seen other physicians (both male and female physicians, I might add). Each woman described on our initial health form that she had felt dismissed, like her problems were trivial, and had felt that the physicians “just weren’t listening to me, he/she just seemed to want to get me out the door, I felt like I was on an assembly line, I felt like I was just being patted on the head like a little girl and my problems weren’t important.” I know there are good, competent, caring physicians out there—both men and women—but I am greatly concerned with the overwhelming frequency with which I hear comments like those above. The trend seems to be getting worse, not better, as more and more patients are thrust into HMO settings where many physicians are on quotas as to how many patients they have to see in an hour. Do any of these descriptions sound familiar?

“I hit thirty-nine and all of a sudden I’m a witch before my period. I never used to have PMS, and this is terrible. My mood! What’s happening to me?”

“I used to sleep so soundly a train coming through the bedroom wouldn’t wake me up. Now, I wake up five or six times a night, wide awake, my heart racing, and I get up in the morning feeling like I never went to bed. I’m just forty-two, and I asked my doctor if I was starting into menopause, but she said I’m too young.”

“Could I have PMS? I go through these awful moods—bitchy, cranky, irritable, yelling at my kids—the week before my periods, and then it seems to go as quickly as it came on after my period starts. And my hip joints, knees and shoulders seem stiff and achy so much. Am I beginning to get arthritis?”

—FORTY-ONE-YEAR-OLD MOTHER OF TWO

“I never had headaches, and last year I started getting fierce, stabbing, pounding headaches the day before my period. I feel like my head is coming apart, and I’ve missed work more, I just can’t function when a headache hits. I’ve seen three doctors. They tell me there’s nothing wrong to worry about, but nothing has helped stop these headaches. What can I do to get some relief?”

—FORTY-SEVEN-YEAR-OLD WOMAN

“My bladder is acting up, I have more problems with infections, and I want to see if you have any ideas to help me. I’ve been having these strange times each month before my period when I feel like somebody pulled a curtain over my brain. I feel foggy, my memory is shot, I can’t sleep and wake up a dozen times a night soaking wet, I don’t have any energy and I feel really blue and bad about myself. Is this stress or am I getting depressed? My doctor told me it’s just PMS and not to worry about it, but I never had this before. Is there anything that will help?”

—THIRTY-EIGHT-YEAR-OLD WOMAN

“My sex drive is gone. Zip. Zero. Just nothing there. I love my husband, we have a great relationship, I enjoyed our sex life. I have less stress in my life than I have had for years. Things should be good. I don’t understand it. My periods are getting lighter. Some months I don’t have one. My hair is falling out in clumps and I always had such great hair. I’m not sleeping very well, my energy seems shot. I feel like I’ve been run over by a truck. I try to keep going, but inside I’m worried about what is going on. My doctor said I couldn’t be starting menopause because I am too young, and she said my thyroid was normal.”

—THIRTY-SEVEN-YEAR-OLD WOMAN

PMS. PCOS. Perimenopause. Panic. Premenopause. Stress. Uncertainty. What does all this mean? One thing is clear. There are a lot of unanswered questions out there. There are a lot of women who are confused by the terms, unsure of when to be aware of changes that might mean menopause is beginning. There are also a lot of women who are experiencing premenstrual problems, who are seeking help and having difficulty finding it. I hope you will find the beginning of some answers as you read this chapter, and I also hope that if you are having problems like this, you will learn some options for feeling better.

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) was first described in modern medical writings in 1931 by Dr. Robert T. Frank, an American gynecologist. (Unfortunately, his work appeared in the Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, a journal not widely read by the rest of the medical profession.) Incredibly, these kinds of problems were also described in the writings of Hippocrates in ancient Greece. In the new millennium, medical science still says we aren’t sure what the causes are, or what helps, or even if the mood and physical changes are caused (or contributed to) by hormonal changes. Of course, most women who suffer with these problems are pretty certain there is a hormonal connection, and I would definitely agree.

An overlooked serious metabolic endocrine condition affecting about 6 percent of premenopausal women, including teenagers, called polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), often causes premenstrual mood and physical symptoms similar to PMS, but there are other changes with PCOS as well. These are described in more detail in chapter 13, but briefly, PCOS causes excess hair growth, irregular menses, waistline weight gain, high blood pressure, high androgen levels, insulin resistance with glucose intolerance, and marked increase in risk of diabetes mellitus later in life. A sixteen-year-old young woman I saw recently had severe hormonal imbalance typical of PCOS, with a very high level of free testosterone, low estradiol, and had gained fifty pounds over six months in spite of a very healthy diet and extensive exercise regimen. She had PCOS, but her gynecologist had not recognized it, because he saw her as simply a teenager obsessed with weight gain and complaining of PMS. Many physicians don’t realize that PCOS has potentially devastating consequences for the rest of a woman’s life, and could lead to early death from heart attacks or diabetes complications long before menopause. So it isn’t just a cosmetic issue—your life may be at stake. That’s why I am addressing these issues together in this chapter. For more information on the specific ways PCOS increases risk of heart disease, see chapter 13.

As I have listened to women’s descriptions over the years, I have to say it seems pretty obvious that there has to be some kind of hormonal connection in something that happens cyclically before menses on a consistent basis and resolves after the period is over. Just because we physicians and scientists may not have found the connection doesn’t mean it isn’t there. I do find it curious, however, that medical science has considered the hormonal-mood connection “controversial.” Most studies I have reviewed do not even measure hormone levels—the reason given is usually something inane like hormone levels aren’t reliable (they can’t be if you don’t check them), or hormone levels vary. Of course. That’s the point. They do vary, throughout the menstrual cycle! I think the question is: HOW do they vary, and in what relationship to the pattern of mood changes and physical symptoms?

“All these women can’t be wrong!” I said to myself. I knew that what I was seeing, and hearing my patients describe, was clearly different from the biological disorder of major depression. So I began to try and figure it out based on what I was hearing, and what I knew could be measured. I systematically checked hormone levels at specific times in the menstrual cycle, and used daily mood rating scales, depression inventories, and other measures. The patterns of hormonal change I have identified as being connected to the premenstrual mood and physical changes are:

1. Declining estradiol levels in the luteal phase (relative to levels seen in women without PMS), yet normal ovulatory levels of luteal phase progesterone being maintained, even when estradiol is significantly below optimal ranges

2. Changing ratios of estradiol and progesterone in the luteal phase

3. Lower-than-expected levels of testosterone, or in the case of PCOS, higher-than-expected levels of androgens (testosterone and DHEA), particularly the free, biologically active fraction

4. In women in their mid-thirties to mid-forties, lower-than-expected estradiol levels in the first one to three days of menses, but with FSH levels still in the premenopausal ranges

Women in this last category are still menstruating (unless they have had a hysterectomy) and most are still ovulating, but their estrogen is declining and appears to have a marked and consistent connection with the symptom clusters such as those described at the beginning of this chapter.

Now, do we call it PMS, PCOS, premenopause, or perimenopause? One of the reasons this becomes confusing is that these terms are used in many different ways in the media and in scientific articles. Generally, but not always, premenopause refers to a woman still menstruating regularly; perimenopause refers to a woman who has begun to have erratic, inconsistent periods with changing flow-patterns (may be heavy one month, lighter and shorter the next), and she is also beginning to skip periods; PMS refers to the symptom cluster of physical and emotional changes occurring between ovulation and menses, which then clears for a symptom-free interval each month. PMS may occur in both pre- and peri-menopause, since women are still having their ovary cycles. Menopause technically means “cessation of menses” and loss of the ovary cycles. I pointed out earlier, however, it is difficult to know when the last period is until a woman has gone an extended time without any menstrual periods, usually at least a year. If we use the commonly accepted definition of PMS, it doesn’t occur after menopause because there are not any more ovary cycles. In menopausal women taking cyclic progesterone or progestin hormone therapy, however, there may be PMS-like symptoms that still occur. Postmenopause refers to the years after the complete cessation of menses. Now that I have defined the terms, they may not really tell you all that much, because they aren’t always used the same way in all settings. The other problem is that rarely is there a discussion of age ranges, or the fact that chronological age doesn’t necessarily correlate well with the endocrinological age. You will typically see health books and articles write as if the chronological age were the primary indicator of what to expect with menopause changes. What we really must assess is the endocrinological age to determine whether you are menopausal or not.

The climacteric, pre-, or perimenopausal years are a normal phase of a woman’s reproductive life cycle. Many women make this transition to menopause without difficulty; however, approximately 60 to 80 percent of women DO experience mild to moderate symptoms such as PMS, insomnia, worsening premenstrual tension, irritability, mood swings (lability), and tearfulness during their thirties and forties. How serious are such symptoms? They are usually not serious enough to cause significant disruption in home, work, and social relationships and activities. Another 15 to 20 percent of women, however, experience marked luteal phase (PMS) symptoms, which are severe enough to disrupt optimal function at home and work, and are a significant source of distress for the individual woman. Several recent studies have shown that these brain-mediated symptoms are actually more numerous during the premenopause (typically, ages thirty-nine to forty-nine years) than after menopause. When articles say “there’s no evidence that women become more depressed at menopause,” they are missing the important time frame in which to look for these mood changes, as well as to look for major depression. Based on the existing studies that have asked this question, and included women in their late thirties and early forties, such distressing symptoms are extremely common and do appear to correlate both with declining hormone levels and with widely fluctuating hormone levels. Many women know or suspect this connection, but have had their observations devalued and discounted.

Early effects of estradiol decline usually manifest as restless sleep, premenstrual migraines, chronic fatigue, declining libido, the premenstrual mood changes I listed above, and irregular menstrual cycles with changing flow (lighter or heavier). While women in midlife may also be experiencing many life changes—balancing home, career, children, aging parents, community roles—I find that their changing physiological hormone balance often increases their susceptibility to situational stressors and contributes to an increasing degree of bothersome symptoms, as well as to increasing health risks for future problems like bone loss. This can become a vicious cycle in that physiological and psychological stressors further suppress ovarian function, which then exacerbates bone loss, particularly if the woman is a smoker or lacks adequate dietary calcium and weight-bearing exercise.

These are not just the “worried well” women, as they have been labeled in some settings when health professionals (and sometimes other women) perceived these kinds of symptoms as minor. I have not encountered many women who want to take time off from work or away from their families and busy lives to come for a medical appointment just because they are “worried but well.” I think this is another paternalistic attitude about women, whether it’s a male or a female physician who voices such a view. In my experience, the women who come in are having health changes that are a significant source of distress, or they wouldn’t be making the effort and spending the money (and time, which may be even more valuable to many women these days) to come and see a physician. I think we in medicine sometimes forget that point and think women have nothing better to do than come see the doctor. I do think there is something important going on; I just don’t think our present healthcare settings have really listened to what our midlife women have been trying to tell us. This next woman’s story will give you some insights as to why I think these issues should be taken seriously.

Sue was a thirty-six-year-old married woman, with no prior history of depression, who came in for an evaluation of “worsening PMS” over the past several years. She was very concerned that her mood changes and angry outbursts were getting out of hand, both at home and at work. She was worried that because she had gotten angry at her boss several times, and had “popped off” at a coworker, she might be in danger of losing her job. She was also beginning to realize that during her PMS time, she was craving alcohol in a way that she had never experienced before, and was consuming more alcohol during that week than she felt was healthy. She had not had any pattern of daily alcohol abuse and had not experienced any alcohol withdrawal episodes, but she was worried about her increasing tendency to drink too much in the week before her period. She also described herself as “a raving maniac for chocolate” during the premenstrual week, and had even gone to the store at 2:00 A.M. to buy chocolate candy. She knew that wasn’t particularly safe, given where she lived, but she said “it was such an overwhelming urge, I thought I would fly out of my skin if I couldn’t get some chocolate right then!”

In getting a complete and more detailed picture of her symptoms, both at the initial visit and then with the daily symptom logs she kept for the next two cycles, it was clear that she had a well-documented, progressively intensifying pattern of premenstrual (luteal phase) mood changes (lability), tearfulness, anxiety, irritability, anger outbursts, depressed mood, decreased energy, restless sleep, nightmares, cravings for sweets and alcohol, breast tenderness, bloating (with a three- to five-pound weight gain), and constipation. She described feeling “almost suicidally depressed” just prior to her menses, although she had never made any suicide attempt and had not been treated for a primary depressive disorder. She said “the weird thing is, once my period starts, the feeling of wanting to die seems to vanish almost as fast as it came on, and it’s gone completely until next time before my period, and then it all starts again.” She also described difficulty functioning at work the week before menses, due to her mood changes, diminished energy, and a decreased ability to concentrate, along with changes in her short-term memory and word recall.

She did not have a sustained pattern of depressive symptoms present throughout her menstrual cycle, and described feeling “my mood lifting, and I felt normal again” soon after menses began. In her words, “I hate this merry-go-round of being this way . . . two weeks of the month I’m fine, and ten days of the month I’m a lunatic. Isn’t there anything I can do to get this under control and feel better?”

Her past medical history was unremarkable for major medical illnesses. She had a pregnancy at age fifteen, but later was unable to conceive. She was found to have marked endometriosis and underwent laser surgery treatment at age twenty-eight, which appeared to solve the menstrual pain and cramps she had previously experienced. Menses continued to be regular. She took no medications except Tylenol occasionally for premenstrual headache or back pain. She started to smoke cigarettes at about age eighteen and was soon smoking two packs of cigarettes a day. She did not have a history of illegal drug use.

Both parents were alcoholic, and her three sisters had all suffered from PMS. Two sisters had undergone hysterectomies, and it was no longer clear whether they had a cyclic pattern to their symptoms. Neither her sisters nor her brother had ever required treatment for major depressive disorder. Her biological father’s medical history was not known, other than that he had been an alcoholic. Her mother was diabetic, not yet on insulin, and had been alcoholic but off alcohol for two years. Her mother had no history of depression. There was a strong history of diabetes in both parents’ families.

Her physical examination was normal, including pelvic and pap. She was slender and had a normal blood pressure. Her blood studies showed a normal chemistry profile, normal blood cell count, and normal urinalysis. Her thyroid profile, including TSH, was also normal. Day 1 estradiol was low at 20 pg/ml; her Day 20 estradiol was also quite low at 57 pg/ml (it should have been in the range of 150–250 pg/ml), but FSH and LH were still at premenopausal levels. Progesterone on Day 20 was 10 ng/ml, which indicated an ovulatory level of progesterone even though her estradiol was so low. Testosterone was less than 20 ng/dl, also too low.

Since she had such pronounced sweet cravings premenstrually and a strong family history of diabetes, I thought she may be having progesterone-induced changes in blood glucose regulation in the second half of her menstrual cycle. I suggested a luteal phase five-hour Glucose Tolerance Test, which was done in my office where I could observe any major symptoms and where my staff could help track symptoms in between blood drawings. She developed drowsiness, palpitations, and fell asleep in the first hour and a half of the test; between the third and fourth hours, she became cool, clammy, sweaty, nauseous, had trouble reading, burst out crying, described feeling anxious, and experienced the intense urge for alcohol “to calm me down.” About twenty minutes later, these symptoms had passed, and she described feeling extremely tired, “wrung out,” and had difficulty concentrating on her magazine. When we reviewed the test results two weeks later, she showed a rapid rise in her blood glucose to 180 mg/dL at the first hour (which had contributed to her drowsiness) and at hour four her blood glucose had dropped sharply to 45 mg/dL (normal is greater than 65 mg/dL). With the adrenaline surge triggered by the dropping glucose (which had caused the symptoms she experienced between hours three and four), her blood sugar had risen to 60 mg/dL by hour five. This was still lower than her initial fasting glucose, which had been normal at 84 mg/dL. I explained that she had a reactive hypoglycemia pattern, which is common in women who have diabetes in their families and is aggravated by the effects of progesterone on insulin secretion in the second half of the menstrual cycle. I thought this was a major factor in her premenstrual craving for alcohol and sweets.

With her long history of smoking and her current low estrogen levels, I recommended she have a bone density test done even though she was still menstruating and was only thirty-six. My goal in recommending the test was to have a baseline evaluation, but it turned out that she was already quite low for her age on bone density at the hip. This meant she was at a much higher risk for early osteoporosis.

With all this information, what recommendations did I make for this woman? First, dietary and lifestyle habit changes were crucial. She needed to decrease caffeine to help keep her from losing more calcium and making her bone loss worse. I also urged her to stop smoking because of tobacco’s many adverse health effects; but the most crucial reason for stopping smoking was the further suppression of her ovaries by smoking, which in turn caused more loss of estrogen and more bone loss. She was clearly much too young to have this much bone loss. She needed to completely eliminate alcohol during her premenstrual week, because this made her blood glucose changes even worse and contributed more to the depressed mood and angry outbursts, as well as additional loss of calcium needed for her bone health. She had not realized how damaging the alcohol was and had thought it helped keep her from having the mood changes and anxiety symptoms. She was willing to eliminate it once she had experienced the effects of the blood glucose changes so dramatically. The nutritionist in my office went over a meal plan to control the reactive hypoglycemia, which consisted of approximately 40 percent complex carbohydrates, 30 percent fat, and 30 percent protein with three smaller meals and three healthy snacks daily during the premenstrual week in particular. She was advised to avoid salty foods that aggravated her fluid retention.

Second, I thought that hormonal approaches were important. This is an example of a situation where having information about the hormone levels made a difference in the treatment recommendations. Without such definite evidence of low estrogen, I would not have been as likely to suggest she consider adding hormones. If medication had been needed, I would probably have used one of the serotonin-augmenting medications for the second half of her menstrual cycle and encouraged her to make the dietary and lifestyle changes I had described. But given the significant objective evidence of early ovarian decline (bone loss, low estradiol), and the severity of the premenstrual hormonal effects on mood and sleep, we discussed the pros and cons of adding estradiol during the premenstrual and menstrual week to boost estradiol levels to more normal ranges.

I gave her several articles to read about these options and encouraged her to think about what she wanted to try. She was aware that, due to her continued cigarette smoking, she was not a candidate for a trial of oral contraceptives. When she came back for her follow-up visit to discuss her choices, she said “my quality of life for the next ten to fifteen years is more important than the remote chance of some dread disease.” We also discussed the possibility that adding estradiol might have a slight possibility of triggering her previous endometriosis. She decided she wanted to try Vivelle anyway, since she had no problems with endometriosis since the laser surgery and her PMS was so disruptive for her. Four weeks after beginning the estradiol patch she stated she was feeling better overall, and both subjective and objective ratings of PMS symptoms had improved significantly. She continued to use the estradiol patch premenstrually for another two years, at which time she had successfully stopped smoking and wanted to change over to the low-dose birth control pills. She has continued to do well on her overall program and has maintained a healthier lifestyle in addition to the hormone regimen. She feels that hormonal stability has helped immensely to eliminate the disruptive mood and physical symptoms. I think the dietary changes were also a significant factor in helping her feel better, but I agree that restoring her estrogen level to a more normal range was a crucial dimension of her improvement. I believe this is a good example of the way in which our approaches need to be individualized, utilizing objective information combined with the patient’s descriptions, to determine how best to create a woman’s personalized health plan.

At this point, you may be asking yourself, “Well, did she have PMS or was she perimenopausal?” Technically, by our currently accepted definitions, Sue had PMS and was not yet perimenopausal, because her FSH and LH were still low (premenopausal levels), and she was still menstruating regularly. The window of time chronologically listed as perimenopausal is usually given as four years before menopause and four years after menopause, taken as an average age of fifty-one. Because women are all so different, I really find these arbitrary age ranges rather useless. I also think that what we will come to understand in the future is that the observed pattern of “worsening PMS” in the mid- to late thirties and forties is in all probability the beginning of ovarian decline leading to perimenopause, and that the worsening symptoms of PMS are all part of the continuum of women’s midlife changes rather than discrete points in time.

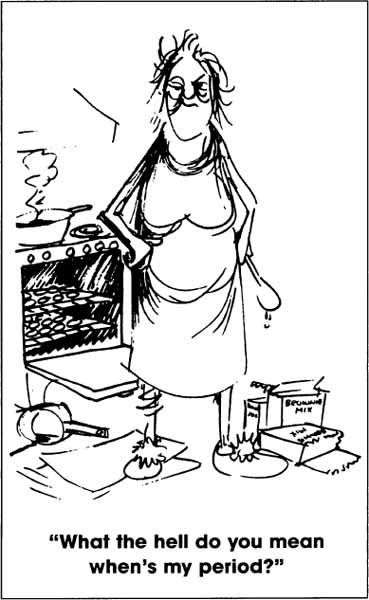

Some of you may have experienced PMS, or family members with PMS, and it may have looked a little like this:

Cartoons by Gordon Vliet © 1983

Women at my seminars howl with laughter and self-recognition when I put up the slides of these cartoons. I have to admit, somewhat sheepishly, that these were drawn by my husband a few years ago when I asked him to draw something funny for my talks. Little did I know that he was such a keen observer! So now you know some of my PMS secrets.

I enjoy the humor, but there is a downside to it: If by joking about it, we trivialize the experiences of women who are truly bothered by symptoms of PMS each month, then it doesn’t become a focus of medical study to determine the causes of and to find ways to help the significant percentage of women who suffer from PMS.

Look at these statistics:

• 40 percent of all menstruating American women have regular premenstrual symptoms. This figure translates into 27 million women! The majority of these have a milder form of the disorder, with bloating, headache, irritability, and the “blues.”

• 5 to 10 percent of these, or 3 to 7 million women, have symptoms severe enough to disrupt their personal and professional lives.

Even today, we don’t have many answers to the questions I have raised above. The science of the menstrual cycle still is not adequately understood and lags behind our knowledge of body functions common to males and females. Some of the major difficulties in conducting research into PMS are the heterogeneous and amorphous descriptions of menstrually related syndromes, the multiplicity of populations evaluated, and the paucity of adequate rating instruments—among others. Studies that purport to address the question of menstrually related mood disorders have included subjects from PMS clinics; infertility clinics; women who have had gynecological surgery; patients from primary care settings, with and without complaints of PMS symptoms; college populations; “normal” women without symptoms; and “normal” women with symptoms but not seeking treatment. Some authors have excluded women with irregular menstrual cycles, even though this group is reported to have a greater incidence of symptoms. Such a mixed bag of study populations obviously makes it difficult to come up with meaningful and reliable data!

PMS primarily affects women between the ages of twenty-five to forty-eight, but it can affect adolescents as well: My youngest patient with clearly documented PMS was fourteen. I have been asked by pediatricians to consult on a number of cases of girls with PMS, and I think they may well have some parallels with the erratic hormonal balance and fluctuations seen in the perimenopause. PMS does, however, seem to be more common in older women and to worsen with age, generally becoming most marked for women in their late thirties to mid- or later forties.

The symptoms of PMS typically begin in conjunction with a hormonal change such as puberty, pregnancy, starting or stopping oral contraceptive pills, or following surgery that affects the blood supply to the ovaries, such as tubal ligation or hysterectomy without removal of the ovaries. In fact, a common pattern is for a woman to have the onset of her PMS about three or four years after a tubal ligation. This is now recognized to be related to the alterations in blood flow to the ovary resulting from having the tubes tied. Although when they ask about these connections, many women are still told that “this couldn’t possibly be happening.” This connection between PMS and surgical procedures has been increasingly discussed in gynecology journals. Thus, new techniques for tubal ligations have been developed to minimize any negative effects on ovarian blood flow. Use of oral contraceptives with a multiphasic (many are triphasic) hormone content has also been found to produce a PMS-like syndrome in a significant percentage of women. A multiphasic pill has two or three different hormone doses, designed to theoretically mimic the normal cycle using synthetic hormones (some brand names are Triphasil, Tri-Levlen, Tri-Norinyl, Ortho Tri-Cyclen, Ortho-Novum 7/7/7, Ortho-Novum 10/11, Jenest). Aggravation of PMS, as well as migraine headaches, are reasons I don’t recommend this type of birth control pill, especially for perimenopausal women who tend to be more negatively affected by the hormonal fluctuations produced by the multiphasic pill.

I find it fascinating to look back in the older medical literature, when the observations of patients formed the basis of clinical writings and practice. Such observations are now called “anecdotal” information and devalued in importance. I have included Dr. Frank’s original description of the PMS syndrome he recognized from observing and listening to his patients. I think it is important for several reasons. First, dietary habits in the United States in 1931 included far more fresh fruits and vegetables, and less refined sugar, alcohol, and caffeine than is typical today; yet women are describing the same experiences then and now. So, while dietary factors play a role in aggravating PMS symptoms, I do not think they are the primary cause of PMS. The language Dr. Frank used in 1931 is somewhat different from words I would use today, but notice how similar his description is to what women continue to describe in 2000. Over the last seventy years since Dr. Frank’s article, nothing much has changed in women’s described experiences, so why would we even question whether PMS is real or not? Yet, you will still hear people arguing over this issue and saying PMS is a psychological problem without evidence of a hormonal cause.

DESCRIPTION OF PMS: 1931

The group of women to whom I refer especially complain of a feeling of indescribable tension, from ten to seven days preceding menstruation, which in most instances continues until a time that the menstrual flow occurs. The patients complain of unrest, irritability, feeling like jumping out of their skin, and a desire to find relief by foolish and ill-considered actions. Their personal suffering is intense and it manifests itself in many reckless, and sometimes, reprehensible actions. Not only do they realize their own suffering, but they feel conscience-stricken toward their husbands and families, knowing well that they are unbearable in their attitudes and their reactions. Within an hour or two after the onset of the menstrual flow complete relief from both physical and mental tension occurs.

—ROBERT T. FRANK, M.D.

It is important to note that the key defining characteristic of PMS is the cyclicity of symptoms, which then resolve around the onset of menses. PMS alone occurs prior to menstruation, and the bleeding phase itself is usually painless. PMS is not menstrual pain and cramps. The medical term for menstrual pain is dysmenorrhea, and it is another disorder altogether, although it may coexist with PMS in a small percentage of women. This is the widely used operational definition of PMS now:

CURRENT MEDICAL DEFINITION OF PMS

A pattern of recurring mood, behavioral, and physical symptoms which regularly occurs between ovulation and menstruation (in the luteal phase) and abates by the end of menstruation to then be followed by a symptom-free interval each month. Symptoms are present for at least six months, cause moderate to severe disruption in normal functioning, and are not due to another disorder.

PMS, which is cyclic, is also different from major depressive disorder, which is a sustained pattern of depressed, dysphoric mood and physical symptoms. I will discuss major depression in the next section. PMS as a recurring pattern of symptoms that may include anxiety attacks, is also different from panic disorder or dysthymic disorder, which are ongoing disorders without a clear pattern of relationship to the premenstrual phase of the cycle. Before concluding that a woman has PMS, the physician needs to rule out other medical disorders that may mimic the symptoms of PMS, such as thyroid problems, diabetes, and others.

There have been over 150 symptoms described as part of PMS, but these can be grouped into a few common patterns of symptoms. I have designated several major categories: affective (mood), behavioral, autonomic, fluid/electrolyte, dermatological, cognitive (brain), pain, and an “other” group. The list below features some of the frequently reported symptoms in each category. Not every woman will have all of these symptoms, but for each woman there is usually a typical pattern, and the same symptoms tend to recur with each cycle. Sometimes the symptoms for one person may begin soon after ovulation and continue until menses; in other women the symptoms begin about the peak of luteal phase rise in estrogen and progesterone (about Day 21 or 22), a week before the period. Pattern of onset may vary from woman to woman but tends to stay about the same in a given person from one cycle to another, which is why symptom logs kept daily for several cycles are so helpful in making a correct diagnosis of PMS.

PMS SYMPTOM CLUSTERS

AFFECTIVE: depression, irritability, anxiety, angry outbursts, tearfulness, panicky feelings

BEHAVIORAL: impulsive actions, compulsions, agitation, lethargy, decreased motivation

AUTONOMIC: palpitations, nausea, constipation, dizziness, sweating, tremors, blurred vision, hot flashes

FLUID/ELECTROLYTE: bloating, water weight gain, breast fullness, hands and feet swelling

DERMATOLOGICAL: acne, oily hair, hives and rashes, herpes outbreaks, allergy outbreaks

COGNITIVE (BRAIN): decreased concentration, memory changes, word-retrieval problems, fuzzy thinking, foggy brain feelings

PAIN: migraines, tension headaches, back pain, muscle and joint aches, breast pain, neck stiffness, and pain

OTHER: drug/alcohol abuse, food binges, hypersomnia, or insomnia

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1955

In spite of clinical evidence of physiological changes as the underlying disturbance, most medical textbooks, researchers, and physicians have attributed PMS symptoms to psychological or sociological causes—such as women’s failure to accept the female role. Though psychological factors may intensify the patient’s suffering, they do not cause the syndrome. Dr. Samuel Yen and other current researchers who have systematically studied PMS think that it is a neuroendocrine imbalance. The underlying mechanism involves neuroendocrine triggers within the hypothalamus and pituitary that then affect the function of such neurotransmitters as serotonin (ST), norepinephrine (NE), dopamine (DA), and acetylcholine (ACh) (see chapters 3 and 4).

The diversity of symptoms in PMS is caused by the many different brain centers and the whole series of pituitary and hypothalamic neuropeptide hormones governed by these neurotransmitters (TSH, FSH, ACTH, beta-endorphin, and alpha melanocyte stimulating [MSH] hormone and others). The neuropeptides beta-endorphin and MSH not only regulate the neurotransmitters involved in mood and behavior, but they also modulate pituitary release of other hormones such as prolactin and vasopressin, which produce a number of physical and mood effects on the brain and body. The brain-body regulation of progesterone and estrogen in response to these changes in neuropeptides differs from woman to woman and I think accounts for the various clinical forms of PMS. As better-designed studies are done, I think we will find that hormone ratios and rate of change are key factors triggering the diverse brain-mediated symptoms of PMS.

Dr. Katharina Dalton, the British pioneer who has studied PMS patients for more than thirty years, hypothesized that a deficiency of progesterone relative to the amount of estrogen present before menstruation triggers the syndrome. Dr. Dalton found that some women with PMS respond well to large doses of natural progesterone, but PMS researchers and clinicians have not found this to be consistently true. Dr. Dalton’s theory, however, was not based on actual measurements of hormone levels in the manner I have described in my book. In my clinical experience of actually measuring the luteal phase hormone levels in several thousand PMS patients, I have found that the most common pattern is low estradiol and normal progesterone levels. Thus, I have found that Dr. Dalton’s theory did not hold up under closer scrutiny and use of objective laboratory measures. I think this is one reason researchers and physicians report such mixed results about the use of progesterone to treat PMS: The treatment is applied across the board to all the PMS patients in the study, regardless of whether they actually had low-luteal phase progesterone levels or not.

In the patients of our practice, I have not found progesterone alone to be very helpful, but this is what you would expect if the progesterone levels are normal and it is the estradiol that has declined. If I do find a patient who has low progesterone levels in the luteal phase and has normal estradiol levels, then I would use progesterone, and I would expect it to alleviate the symptoms. But in many women, the declining estradiol is a more crucial factor. The clear pattern of hormone profiles in the majority of my patients is one of low estradiol (E2) and relatively normal levels of progesterone (P), so that there is a reduced ratio of E2 to P. If this is the pattern on the laboratory studies, then it only makes sense to boost estradiol back to optimal ranges rather than adding progesterone as a first step. In these women, adding progesterone actually makes them worse. Several recent double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have shown that natural progesterone is not any better than placebo in reducing PMS symptoms, and this has been my clinical experience as well. Consequently, I think there is much more to PMS, than just progesterone deficiency. In addition, the many different responses of women to a variety of hormonal approaches suggest we need a more encompassing theory of cause. I view PMS as a neuroendocrine disorder that begins with physiological hormonal shifts affecting multiple brain centers. The brain events then trigger a variety of physical changes in multiple systems in the body and can be aggravated by diet, substance use, and life stress.

Many women describe their worst days in the cycle as being the day prior to bleeding and the first day bleeding begins. Tearfulness, crying spells, fragmented sleep, anxiety attacks, palpitations, and irritability typically are intensified for these two or three days. What causes the elevated frequency of symptoms on these two specified perimenstrual days is not known with certainty. Based on my knowledge of brain chemistry, it seems most likely that these are triggered by the falling and low estrogen. It is interesting that the estrogen levels reach their bottom point of the cycle close to the day before the onset of menses and are still low on Day 1 of bleeding. Low levels of estrogen are known to coincide with both low endorphin levels and high levels of monoamine oxidase enzymes (MAO), which break down catecholamines, resulting in catecholamine depletion in the brain. Loss of catecholamines is a significant factor in precipitating depressive mood changes. The decrease in endorphins contributes to the irritability, tearfulness, and restless sleep.

Dr. E. L. Klaiber and colleagues found that a series of premenopausal women with regular menstrual cycles who suffered from a major depressive illness had higher levels of plasma MAO activity (which breaks down and inactivates catecholamines and serotonin) than did nondepressed women. Dr. Klaiber interpreted these abnormalities as further evidence of norepinephrine/serotonin insufficiency consistent with current biological theories of depression. His study did not attempt to evaluate the therapeutic effectiveness of the estrogen therapy, but all of the patients who received estrogen therapy reported “moderate to marked” improvement in their moods. In another study of women with treatment refractory depression, Dr. Klaiber’s group found that oral estrogen therapy was significantly effective in improving mood in women who had not responded to more traditional antidepressant medications. Taken together with the other evidence I have described in chapters 3 and 4, Dr. Klaiber’s research lends additional support to the role of premenopausal decline in estrogen as a contributing factor in the PMS-perimenopause continuum of mood and physical symptoms.

There is an additional mechanism by which perimenopausal women may experience anxiety attacks and depressive mood changes: This is related to the drop in estrogen levels, which triggers hot flashes that cause multiple awakenings at night. Nocturnal hot flashes causing waking episodes can be objectively measured in sleep laboratories; these waking episodes caused by surges of adrenaline trigger hot flashes that have been confirmed on EEG brain-wave recordings during sleep. Such waking episodes result in sleep deprivation, a factor associated with irritable, depressive mood changes. Eighty to 85 percent of women experience hot flashes that typically occur at night for several years prior to the beginning of skipped periods in perimenopause. The resulting sleep disturbances, coupled with unhealthy lifestyle habits, could contribute significantly to disturbances in mood (irritability and depression), loss of energy, reduced concentration and memory, fatigue, and diminished sense of well-being. I have listed the four key antidepressant actions of estradiol again in the chart below. Unpleasant changes like ones I just described respond best to a boost in estradiol, rather than antidepressants, antianxiety medications, or sleeping pills.

ESTRADIOL: ANTIDEPRESSANT EFFECTS

• Increases serotonin levels and receptors

• Increases endorphin activity

• Inhibits MAO enzyme activity, which prolongs activity of ST, DA, NE

• Enhances binding of tricyclic antidepressants at brain receptors

PMS, ESTRADIOL, AND SEROTONIN (ST)

• Rate of rise and fall in E2: crucial variable in effects on serotonin

• A more rapid rise or fall in E2 causes greater change in ST

• E2 effect on serotonin is a probable trigger for premenstrual migraine and mood changes

(see chapter 10)

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1955

There are other postulated causes of PMS, but these may also be results of the neuroendocrine changes I have already described, so it is unclear whether some of these disturbances are causes of the syndrome or are results of alterations in the reproductive hormone levels:

• altered glucose metabolism perhaps due to alterations in glucocorticoids and/or insulin activity, or the effect of excess progeserone relative to estradiol;

• abnormal fatty acid metabolism resulting in altered tissue sensitivity to reproductive hormones;

• abnormalities in the prolactin, aldosterone, renin, angiotensin, and vasopressin that govern normal fluid and electrolyte balance in the body.

Other factors that may be involved in the rising incidence of PMS in recent years, and adversely amplify menstrual cycle hormonal changes, are as follows:

1. The fact that many women are postponing pregnancy and having fewer pregnancies than women did years ago, resulting in more years of ovulatory cycles, which are clearly associated with a higher incidence of PMS;

2. The significant increase in obesity in our society, which results in increased conversion of androgens in body fat to the estrone type of estrogen in women. This alters the total estrogen-to-progesterone ratio but does not provide the higher level of 17-beta estradiol produced in the ovary, which now appears to be the primary active estrogen at brain receptors. The majority of women suffering from PMS are obese, defined as more than 20 percent over ideal body weight;

3. In addition to the problem with obesity, our cultural emphasis on extreme thinness has resulted in younger, thin women having premature decline in ovarian hormones due to loss of the minimum amount of body fat to maintain normal, ovulatory function of the ovaries. Women who are overly thin, and eat an extremely low fat diet, furthermore do not have the necessary building blocks of cholesterol needed for the ovary to make its hormones. In these women, we often see a low luteal phase estradiol, even if progesterone levels are still in the normal ranges.

4. For the majority of women today, the typical American diet is high in saturated fat, salt, refined sugars, alcohol, and caffeinated beverages, all of which have been shown to significantly aggravate the symptoms of PMS;

5. Most American women today have a deficit of magnesium in their diets, which also contributes to PMS symptoms, due to magnesium’s role as an important cofactor in the synthesis of mood-elevating neurotransmitters and mood stabilization;

6. Inadequate intake of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), which is also a cofactor in the synthesis of mood-elevating neurotransmitters and is involved in the liver metabolism of estrogen and progesterone.

In summary, I think our current research findings lend more support to the integrated theory of PMS being triggered by the brain effects of ovarian hormones, with multiple brain-body systems then being affected and leading to the wide variety of symptoms. This integrated model makes sense to me physiologically, and approaching it from an integrated point of view helps me to develop a more systematic, and physiological, approach to helping women feel better and deal constructively with the menstrual cycle hormonal shifts.

Nearly everyone has occasional down, moody times, or bouts of sadness and discouragement that may last for a while. When do the “blues and blahs” become major depressive disorder, a clinical depressive illness requiring professional intervention and possibly medication? When a black mood settles in and remains for several weeks, sapping your energy, appetite, your interest in life and activities you usually enjoy, and altering your sleep, you may be clinically depressed.

Clinical depression is a medical illness that is thought to have a primarily physical cause, that of a chemical imbalance in the neurotransmitter or “messenger” molecules in the brain. The illness of depression is two to three times more common in women, with the gender differences beginning in puberty and ending after menopause, when rates of depression become higher in males. This gender difference implicates a hormonal factor, which has not been addressed as an important connection in women’s depression.

In spite of major advances in our understandings of the neurobiology of depression, and the development of new and safer antidepressant medications, physicians and the lay public still labor under the misconception that the “chin up and get through it” approach is all that is needed. In fact, according to a recent poll by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, the American public still has many mistaken beliefs about mental illness in general:

- 71 percent believe it is due to emotional weakness

- 65 percent believe it is caused by bad parenting

- 45 percent believe it’s the victim’s fault, can be willed away

- 43 percent believe it is incurable

- 35 percent believe it is the consequence of sinful behavior

- only 10 percent BELIEVE IT HAS A BIOLOGICAL BASIS and involves brain chemistry (in spite of much publicity on this over the past thirty years!)

Clinical depression is a very common disorder, affecting 20–30 percent of adults sometime during their lifetime. Experts estimate that at any given time, some 10 million Americans are in its throes. Unfortunately, even today with so much good information available, depression is still all too frequently misunderstood by the general public and physicians alike. Many people who suffer from depression are too embarrassed to seek help. A common expression I hear in my medical practice is “I feel like I’m weak. I should be able to handle this by myself.” Such self-blaming, negative thought patterns are often a symptom of depression but the person doesn’t recognize these thought patterns as due to the illness, and so has difficulty asking for help.

Lack of proper treatment causes not only untold suffering, lost productivity, and diminished quality of life, but is also a major risk factor in suicide. Fifteen percent of people with clinical depression commit suicide. This is a tragic loss when we consider that treatment of depression is successful for 80 to 90 percent of sufferers, with proper diagnosis and careful use of medication. The lifetime risk of death from major depressive illness due to suicide is greater than the lifetime risk of death from breast cancer.

This physical, or biological, form of depression is not likely to be cured by “talk” therapies alone. Antidepressant medication to reestablish the normal chemical balance in the brain is now considered to be the most effective treatment. Proper medical diagnosis is needed to identify this form of depression and rule out other medical causes for the symptoms, such as hypothyroidism, diabetes, lupus, and perhaps a hundred or more medical problems and medications that have been found to cause a syndrome indistinguishable from primary major depressive disorders. Overuse of alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, decongestants, phenylpropanolamine diet pills, herbal products containing ephedra, and illicit drugs (cocaine, stimulants, hallucinogens, and others) may also cause biological depressions. Severe and prolonged life stress, even though “understandable,” may cause enough biochemical changes in the brain and body to result in depressive illness needing medication and psychotherapy. After a careful medical history, physical examination, and appropriate blood tests rule out these other causes, your physician may recommend antidepressant medication, which can alleviate sustained and severe depressions even though they may be clearly related to life stress.

How do you tell if what you are experiencing is just the normal “blues” or a clinical depression? DURATION of symptoms is one important key. If your mood remains down, blue, sad, discouraged, or hopeless for more than two weeks, in spite of pleasant events in your life, clinical depression is likely. People with clinical depression may also describe feeling “numb,” “leaden,” or like “I’m just going through the motions” of life. Women have said to me “I feel like I’m trying to move my body through quicksand.” Another woman said she felt like her body “weighed a thousand pounds, it was just hard to even start moving.”

Presence of SOMATIC (physical) or VEGETATIVE changes occur, such as significant loss or gain of weight for no apparent reason or changes in your sleep pattern (trouble falling asleep; problems with multiple awakenings at night; or waking up very early, unable to go back to sleep). Loss of energy, feeling “keyed up” and “hyper,” or feeling very “slowed down” and “sluggish” are other signs, along with changes in your ability to concentrate on tasks, loss of sex drive, fatigue, menstrual irregularities, marked decrease or increase in appetite with compulsive overeating, GI upset, constipation or diarrhea, and loss of interest or pleasure in your usual activities.

THOUGHTS OF DEATH OR SUICIDE are very serious symptoms and should never be ignored, particularly if you begin to feel that you no longer care about living and think about ways of taking your life. You must seek a qualified professional to help you if thoughts of suicide are present for any length of time. If a friend or family member tells you about such thoughts, even if they try to pass it off as a joke, you should take it seriously and bring it to the attention of someone who can get them to see a qualified mental health professional or physician for an evaluation. Studies are clear in showing that better than 90 percent of people who commit suicide have told someone ahead of time that they had these thoughts, but many were just not taken seriously and guided to professional help.

If you find that you have five of the above symptoms persisting more than two weeks, it is important that you see your physician for help. Many people come into a physician’s office with vague physical complaints and sidestep the real reason they are seeking help. This only leads to misdiagnosis and delay of proper treatment. Be direct. Tell your doctor that you feel depressed. Depression is just as much of an illness as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease are. Depression can have physical, chemical, genetic, hormonal, medication, emotional, and situational causes. Help is available, and the newer antidepressants have typically very few side effects. Depression is NOT “weak character.” You should not feel ashamed about having the illness of depression.

If your physician recommends an antidepressant, the serotonin-augmenting ones have few side effects and are quite effective. The serotonin-boosters are especially helpful for women in whom depression may be caused or aggravated by estrogen changes that appear to specifically decrease serotonin. Your doctor may also recommend counseling or psychotherapy to help you deal more effectively with the stresses in your life. I think other effective, helpful approaches are professionally led support groups, healthy eating, regular exercise, relaxation training, and/or meditation.

Since the large majority of patients with depression are seen by primary care physicians (often for vague somatic complaints) rather than by psychiatrists, I think it is crucial that YOU know how to recognize symptoms that could indicate the presence of a biological major depression, so you can tell your doctor. I also think it is imperative that we intensify efforts to help primary care physicians recognize milder forms of depression and begin to treat these syndromes appropriately, using antidepressant medications when indicated. Patient education brochures on depression are published by the National Institute of Mental Health and are available free. Simple screening questionnaires, such as the Zung Depression Inventory, are also available free from various sources and are valuable aids to you and your physicians to identify “masked” depression. I have included one of these self-tests for depression in appendix III.

I think it is crucial that we teach women that depression is a highly treatable biologically based disorder, and getting help early greatly reduces suffering and debilitation, as well as helps to reduce the economic burdens of excessive medical utilization and lost productivity in the workplace or at home. Yet, I do think ovarian, thyroid, and adrenal hormone levels should be carefully and completely checked before the diagnosis of major depression is made. If you find yourself feeling overwhelmed by life and slipping into a major depression, don’t feel ashamed and withdraw or hesitate to ask for help. Clinical depression is a highly treatable medical condition—one that you should NOT have to suffer through alone.

In spite of the fact that we live in a culture that often times acts as if women don’t have a brain, WE DO, and the brain is a physiological organ, as well as the psychological organ of “mind” expressing our personality, psyche, and behavior. It is affected by outside stressors (stimuli) and by internal stimuli or changes in the body, so that many times what are labeled psychological symptoms and assumed to have a psychological cause may in fact be caused by biochemical changes in our body’s physiological balance. Likewise, psychological stress causes profound changes in every cell in the body, including brain chemistry.

For both men and women, stress of whatever form, whether it’s external stressors or whether it’s the internal stressors of physiological changes that require the body to change and adapt, all of us have the body as our “final common pathway” through which these changes act and operate. With prolonged stress the body’s balance, or homeostasis, is disrupted, and we see symptoms that relate to adrenaline overactivity, such as headaches, high blood pressure, panic attacks, colitis, arteriosclerosis, eczema, overwhelming fatigue, and many others. We also see illnesses that are the result of long-term chronic stress having an adverse effect on the immune system, producing problems related to hyperactivity of the immune system such as asthma and allergies; problems related to a hypoactive immune system, such as cancers; and problems that arise when the immune system runs amuck and attacks your own body, such as the autoimmune disorders. All of these are manifestations of the combined effects of stress-induced biochemical changes on the body pathways, occurring over time.

Another aspect of the problem of stress when it affects women is the role of chronic stress in decreasing the normal function and hormone production of the ovaries, as well as the thyroid gland. At a meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Susan Ballinger, Ph.D., of Sydney, Australia, reported on her study addressing connections between women’s perception of the presence of life stress and levels of their ovarian estrogens. Ballinger’s study assessed life events, clinical depression, and anxiety, together with measurements of urinary and plasma estrogens. This study demonstrated that a high level of urinary estrogens correlated with higher psychosocial stress scores. Her conclusion was that “psychosocial stress, emotional vulnerability, and coping skills may all contribute to estrogen deficiency in post menopause.”

From my clinical observations and correlation of the estrogen levels in perimenopausal women, the opposite hypothesis may also be true about the connection between hormone levels and stress, but we don’t yet have much information on this half of the equation: Declining estrogen levels contribute to alterations in the function of norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine that regulate mood, behavior, and cognitive function. Declining estrogen, and the subsequent effect on brain chemical messengers, appears to then contribute to the observed difficulty coping with psychosocial stressors by women who have previously been able to cope successfully. Once again, the role of stress is a two-way street: Life stress suppresses the ovaries, which decrease estrogen production, which affects sleep, and so on. Normal declines in estrogen affect brain chemistry, which affects ability to cope with stress. It’s another one of those vicious cycles, as I have diagrammed in the next section.

Since I am such a “visual” learner, I decided to give you a diagram (see following page) that represents how I see these various stress and hormone factors coming together to cause some of the phenomena, or symptoms, we experience. I see it as a vicious cycle, with one event affecting another until it all snowballs on us. Think about these various pieces of the puzzle as they relate to your life, and your lifestyle habits, and see if it helps you identify some healthy ways to break the cycle.

PMS is commonly not recognized or is misdiagnosed, so it is important for you to seek a thorough evaluation. There are many diagnoses given to women who, in fact, have PMS: Some of these are dysthymic disorder, manic-depressive illness, major depressive disorder, atypical depression, chronic fatigue, chronic candidiasis, panic disorder, anxiety disorder, stress reaction, and others. The goal of a comprehensive evaluation is also to make certain that you do not have another medical problem causing similar symptoms, and to ensure that any previously unrecognized secondary disorders, which may be contributing to your symptoms, are diagnosed and properly treated.

If you are having difficulty feeling that your PMS concerns are taken seriously, you may find a specialty clinic for PMS would provide more helpful resources and suggestions. I have designed the HER Place programs in Tucson, Arizona, and Dallas–Ft.Worth, Texas, to help women get hormone levels properly tested and to identify dietary, lifestyle, hormone, and alternative therapies to alleviate troublesome symptoms. The chart below lists aspects of a complete evaluation, and points to discuss with your physician.

COMPONENTS OF A COMPREHENSIVE PMS EVALUATION

I. MEDICAL HISTORY. Key aspects include:

1. Timing of symptoms (onset, duration, when end)

2. Symptom cluster (types of problems you encounter with your cycle)

3. Onset in relation to some hormonal change (puberty, pregnancy, starting or stopping oral contraceptives, perimenopause)

4. Time of increased severity of symptoms (usually following discontinuation of oral contraceptives, after tubal ligation, following hysterectomy without removal of ovaries, after a pregnancy, after cessation of breastfeeding, or after several months of no menses)

5. History of threatened or actual miscarriage, “toxemia” (pre-eclampsia): 86 percent of women with pre-eclampsia developed PMS in the months following birth

6. History of postpartum depression of sufficient severity to require antidepressant treatment. In one study of 100 women treated for severe PMS, 73 percent had a history of significant postpartum depression

7. Weight fluctuations in adult life greater than twenty-five pounds. Obesity increases the likelihood of PMS for reasons that are still unclear, but may be related to increased estrone production in body fat

8. History of past thyroid problems and/or treatment with thyroid hormone

9. History of painless menstruation (painful menses is a different problem called dysmenorrhea and is more often due to endometriosis)

10. Pattern of food or alcohol cravings and/or alcohol intolerance during premenstrual phase of cycle

11. Inability to tolerate high-progestin birth control pills. Women with PMS often experience severe side effects and/or exacerbation of PMS with high progestin oral contraceptives, particularly the triphasic pills with changing hormone content

12. Increased libido. Women with PMS frequently report increased sex drive during the premenstrual phase, compared to women with primary depression who usually report diminished sex drive

II. FAMILY HISTORY

Note presence of similar problems, especially among women in family, such as diabetes; thyroid disease; multiple allergies; autoimmune diseases; disorders such as alcoholism, depression, and/or mania; anxiety disorders; and eating disorders (anorexia, bulimia). All of these have been associated with increased risk of menstrually related mood and physical changes seen in PMS.

III. MEDICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION

1. Physical examination (if not recently done by gynecologist or primary care physician), with attention to any signs of hormone imbalance

2. Laboratory tests: blood chemistry panel, complete blood count (CBC), thyroid profile with TSH and thyroid antibodies, prolactin, FSH, LH, progesterone, estradiol, testosterone, other lab tests as medically appropriate and indicated by history and physical findings

3. Psychological assessment of emotional and cognitive function, with rating scales such as Beck, Hamilton, or Zung Depression/Anxiety Scales; Profile of Mood States (POMS), Hopkins SCL-90, PRISM Menstrual Calendar, etc.

4. Daily Symptom Log/Journal through at least one and preferably 2-3 menstrual cycles. Should include:

a. MENSTRUAL SYMPTOMS, WEIGHT, BODY TEMPERATURE

b. Dietary intake log relating food intake to time of symptoms

c. Record of alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco use

d. Record of over-the-counter and prescription medication use

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1995, revised 2000

You and your physician should review this information and discuss the various options available that would be helpful to you. I find that a combination of approaches works best. The section that follows lists options to consider, or you may use others that your physician recommends.

There are a variety of approaches that will help you recapture your sense of well-being and zest. At the most basic level, you really can’t expect anything to help a great deal unless you first address constructive lifestyle changes to reduce or eliminate potential triggers and aggravators that make you feel worse if you have PMS. Basic and simple, yet many times not done, are the dietary modifications that have been found to be of help in eliminating many PMS symptoms. Frequently I find that it is difficult to get patients to accept that something as “simple” as changing the way they eat can have a profound impact on the way they feel—their mood, energy level, clarity of thinking—BUT IT DOES! The following suggestions are tried and true. They DO work, but you first have to commit to really giving it your best effort for long enough to see a difference. I found that when I paid close attention to these basics, I was able to eliminate just about all of my own PMS problems. I admit I wasn’t perfect all the time, but these steps do make a big difference. So, before you ask your doctor for medication or rush out for an herbal fix, make certain you try these.

1. Avoid simple sugars (you know what I am talking about: all those sweets that just seem to stick to your fingers!); reduce salt; cut out alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, and chocolate—especially just before your period.

2. Increase intake of complex carbohydrates to 40–50 percent of total daily calorie intake (have a low-fat, low-sugar, high-fiber bran muffin instead of a brownie).

3. Decrease intake of protein to about 20–30 percent of total daily calories, and concentrate on the low-fat protein sources—fish, chicken, low-fat cheese.

4. Space meals properly. Symptoms seen to be worsened by long intervals between food intake, perhaps due to the alterations in glucose tolerance seen in the premenstrual phase. More frequent eating, with smaller portions and less of the simple sugars, also reduces the tendency for women with PMS to crave and binge on sweets.

I can’t say it enough: MOVE THE BODY! Exercise is great medicine! When I do it, I feel like a different person; when I don’t, I feel sluggish. Our bodies were designed to be active. I educate women about the physiological and psychological effects of exercise that are of benefit in PMS: increase in beta-endorphin, stimulation of NE, reduction of excess anxiety, stabilization of serum glucose, suppression of appetite, increase in energy, improvement of mood, enhancement of sexual energy. I teach women how to safely begin an aerobic exercise activity and how to monitor pulse rate for optimum effect. You don’t have to be a marathon runner to get the benefits of increased physical activity. Walking will do it, especially if you have been inactive. If you have any limitations due to medical problems, talk with your physician and get a referral for a trained physical therapist to help you get started with an appropriate program.

Take a look now at the Vicious Cycle diagrams in chapter 17. Stress plays a direct role in negatively influencing the chemical messengers that are out of balance and contribute to PMS in the first place. Look for ways of reducing avoidable stresses, and look for ways you can minimize the adverse effects of unavoidable stresses. One of the techniques I teach my patients is the relaxation response, popularized by Dr. Herbert Benson but used down through hundreds of years in many cultures. You can elicit the relaxation response using a variety of techniques: visualization, progressive muscle relaxation, self-hypnosis, autogenic conditioning, meditation, and others. There are many good books and tapes available to guide you in using these approaches.

Counseling for stress management techniques may be helpful for some women, especially during times when it feels like life is running you over! Getting an outside perspective on what you can do helps you feel more in control, which then decreases the body’s fight-or-flight stress response that intensifies PMS.

Another good stress management technique is having massage therapy during the premenstrual week. Therapeutic massage is an excellent way of improving relaxation, boosting endorphins, improving circulation, and decreasing muscle tension, headaches, and back pain. Look for a registered, certified therapeutic massage therapist in your phone book under American Association of Massage Therapists, or call the A.A.M.T. toll-free number for a member therapist in your area. Acupuncture may also be helpful for some of these stress and PMS symptoms, although this modality does not usually have the more rapid onset of beneficial effect, as do the relaxation techniques and therapeutic massage. Acupuncture, to be most effective, typically requires a series of treatments.

VITAMINS

A variety of vitamin combinations have been reported to help alleviate PMS symptoms, but there have not been clear-cut benefits found in controlled studies. I think particularly if you are under a great deal of stress, which depletes the B group and vitamin C, adding a low dose of B complex supplement at least during the premenstrual week can be helpful for some women. Pyridoxine (B6) has been recommended and reported to ease some of the symptoms of PMS if used in conjunction with diet and exercise. We are not sure how pyridoxine achieves these effects, except that it is a cofactor in many chemical reactions, including those involved in making dopamine and serotonin, and it inhibits prolactin metabolism. B6 may modulate the action of dopamine and serotonin in the chain of reactions that regulate production of estrogen and progesterone. It is also involved in the metabolism of estrogen by the liver and in the metabolism of fats and carbohydrates.

The usual starting dose of B6 is 50 mg per day. Although some herbal practitioners and naturopaths say that you cannot overdose or become toxic on the water-soluble B vitamins, it has been well documented that excessive supplementation of the B vitamins (particularly B6) may cause neurological problems. Do not exceed 50 mg per day because of the risk of peripheral neuropathy (numbness, paresthesias, tingling).

I have found it is better to supplement the B complex vitamins as a group in one supplement rather than taking just vitamin B6, because the B complex needs to be present in the proper balance and ratio in order to work optimally. There are now a number of commercial vitamin formulas that have been theoretically designed for the special needs of women with PMS. Although these are usually more expensive than the general brands sold at the pharmacy, they may provide the balance of vitamins and minerals needed by some women. You may want to consider one of these options.

DIURETICS

Many doctors have used the thiazide diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), Dyazide, Maxide, and others) to alleviate the fluid retention some women experience in the premenstrual week. The thiazides are not the diuretics I recommend, because they further increase potassium loss and may actually aggravate PMS symptoms. They also tend to interfere with normal glucose balance and may increase cholesterol.

If you are someone who clearly experiences documented premenstrual weight gain, bloating, and breast tenderness due to fluid retention, I think the only diuretic that makes physiological sense to use is spironolactone (brand name: Aldactone). The usual dosage is 50 mg (25 mg twice a day) to 100 mg a day (taken in divided doses as 25 mg four times a day, because it is a shorter-acting medication). Spironolactone acts on the fluid-regulating hormone (aldosterone), which is altered by progesterone in the luteal phase of the cycle, leading to fluid shifts. I do not find that most women with PMS need a diuretic if hormonal balance and diet are improved. If you still have fluid retention, however, I think spironolactone is the better choice than a thiazide diuretic.

ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES (OCS).

I find that the steady-dose (monophasic) OCs can provide a marked degree of symptom relief in a large percentage of women, especially pre- and perimenopausal nonsmoking women who are experiencing diminishing estrogen production and erratic cycles. I have found over the years that the key to using OCs in PMS is to start with a pill formulation with the least possible progestin (the culprit for most of the unwanted side effects) and a little better level of estrogen. Many of the ones that are commonly recommended are the pills that are higher in progestin, and lower in estrogen, which is the reverse of what a woman over thirty needs. The three OC pill options on the market in the United States that I have found produce the best results in reducing PMS are: Ovcon-35 (least progestin), Modicon, and Brevicon (next lowest amount of progestin). A new OC Diane-35, available in Canada, has a unique progestin/estrogen combination designed to reduce acne by blocking the androgen receptor. Using the OCs during the perimenopause transition was approved by the FDA for nonsmokers just a few years ago, and the OCs have added health benefits of decreasing the risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers, uterine fibroids, and fibrocystic breast changes. Perimenopausal use of monophasic OCs also helps maintain adequate estradiol levels to prevent bone loss. You MUST NOT SMOKE if you take the oral contraceptives, because smoking increases the risk of stroke and blood clots in women who take oral contraceptives.

Conventional teaching has been that women with PMS don’t do well on the birth control pills due to the synthetic progestin, which can aggravate PMS. I have found that this is true if the progestin content is higher than 0.5mg norethindrone (or equivalent progestational activity). If one of my patients decides to try the birth control pill to reduce PMS, I prescribe only the low progestin formulas. There are still some women who can’t take even the lowest amount of synthetic progestin, but in my experience, this has been a minority. For women who cannot take the synthetic progestins at all, natural progesterone may work, and I talk about this further along in this section.

You might find it helpful to listen to the voices of my patients who have benefited from using oral contraceptives to alleviate the midlife PMS:

A forty-seven-year-old white female described her health as “much better. It’s Christmas and I am not sick, and that’s different from the past three years. I think the hormones [Ovcon-35] are helping me feel a whole lot better. It was really good to find out that there really is something there, I’m not imagining things. I am feeling really good.”

A forty-three-year-old woman who developed severe depression on Loestrin oral contraceptive had these comments several months after changing to a higher estrogen/lower progestin pill, Ovcon-35: “I felt much better, I’m not crying, I don’t feel depressed, I have my energy, I don’t have those headaches. I really have noticed an incredible difference. I have been able to exercise again, and I wasn’t able to do that on the other pill [Loestrin] because I just didn’t have the energy. I felt wiped out all the time.

A fifty-year-old woman said: “The birth control pills were heaven sent. Since I started taking them, I have not had any cramps, the bleeding is less, the depression is much better, that black cloud has lifted, and that’s been wonderful. I’m as pain free as I have ever been with my periods. The minute I started taking them I could tell a difference. I have had only very mild PMS feelings, but the moods going up and down has gotten better. I am so grateful to you that I feel so good.

A thirty-six-year-old woman, now on the monophasic oral contraceptive, said her physician was against her taking the hormones because of family history of breast cancer in her grandmother, “but I discussed it and felt like this was right for me and I decided to do this. I am much, much better. It’s been three weeks on the new pills, I am sleeping through the night, the crying spells are almost completely gone even though I have a reason to cry because a family member almost died of a brain abscess and I flew to another city to take care of him. I handled it really well. I don’t have the crying-for-no-reason spells like I used to. I’m like a different person, a great decrease in anxiety, I’m not irritable, the GI symptoms have resolved, I have enough energy I’m exercising in the morning going to the gym, my mood’s even, my secretary even said I seem a lot happier, I feel more focused, and my memory is somewhat better and I am getting more organized at work. I am ecstatic about my improvement, I can’t thank you enough. I’m glad to know I wasn’t crazy when I was having all the things I was experiencing.