This chapter was written by Elizabeth Neal RD, PhD. Based in the United Kingdom, Dr. Neal is a world expert in the MCT diet.

By the mid-20th century, when the classic ketogenic diet was falling out of favor because of availability of new anticonvulsants and a feeling that large amounts of fat were unpalatable, Dr. Peter Huttenlocher of the University of Chicago set out to invent a new and improved form of ketogenic diet. He believed that the ketogenic diet was an effective form of therapy and that more families would try—and benefit from—a ketogenic diet if it were formulated with foods more closely approximating a normal diet. Dr. Huttenlocher and his group replaced some of the long chain fat in the classic ketogenic diet; that, is fat from foods such as butter, oils, cream, and mayonnaise, with an alternative fat source with a shorter carbon chain length. This medium chain fat, otherwise known as medium chain triglyceride (MCT), is absorbed more efficiently than long chain fat, is carried directly to the liver in the portal blood, and does not require carnitine to transport it into cell mitochondria for oxidation. These metabolic differences give MCT increased ketogenic potential, that is, it will yield more ketones per kilocalorie of energy provided than its long chain counterparts. This increased ketogenic potential means less total fat is needed in the MCT diet. Whereas the classical 4:1 ratio ketogenic diet provides 90% of its calories from fat, the MCT ketogenic diet typically provides 70–75% energy from fat (both MCT and long chain), allowing more protein and carbohydrate foods to be included. The increased carbohydrate and protein allowance makes the MCT diet a useful option for some children, especially those with limited food choices.

The original MCT diet provided 60% of energy from MCT; the remaining 40% was usually divided up to provide 10% energy from protein, 15–19% energy from carbohydrate, and 11–15% from long chain fat. However, this level of MCT can cause gastrointestinal discomfort in some children, such as abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting, especially if the MCT is introduced too quickly into the diet. For this reason, Schwartz et al. in 1989 suggested using a modified MCT diet, which reduced the calories from MCT to 30% of total and added an extra 30% of calories from chain fat. In many children, this lower amount of MCT may not be enough to ensure adequate ketosis for optimal seizure control, and in practice, a starting MCT level somewhere between the two (40–50% energy) is likely to be the best balance between gastrointestinal tolerance and good ketosis. This can then be increased or decreased as necessary during fine-tuning.

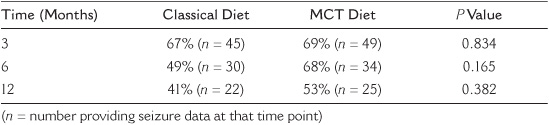

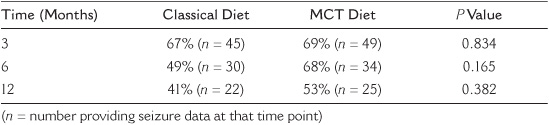

Schwartz and her group also compared the clinical and metabolic effects of the MCT ketogenic diet, both traditional (60% MCT) and modified (30% MCT), with the classical 4:1 ketogenic diet. They found all three diets equally effective in controlling seizures, but compliance and palatability were better with the classic/ketogenic diet. However, in this study children were not randomly allocated to one of the diets, leaving it open to possibility of bias. The question of differences in efficacy and tolerability between the classic and MCT ketogenic diets was looked at again by Neal et al. in 2009, but this time using a randomized study design. One hundred forty-five children with intractable epilepsy were randomized to receive a classic or MCT diet. Seizure frequency was assessed after 3, 6, and 12 months, and these data were available for analysis from 94 children: 45 on a classic diet and 49 on a MCT diet. Table 20.1 shows results for percentage of baseline seizure frequency between the two groups after 3, 6, and 12 months Although the mean value was lower in the classic group after 6 and 12 months, these differences were not statistically significant at any of the times (the P value is greater than 0.05 at 3, 6, and 12 months). There were also no significant differences in numbers achieving greater than 50% or 90% seizure reduction. Serum acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate levels at 3 and 6 months were significantly higher in children on the classic diet; this was also the case at 12 months for acetoacetate. There were no significant differences in tolerability except increased reports in the classic group of lack of energy after 3 months and vomiting after 12 months. This study concluded that both classic and MCT ketogenic diets have their place in the treatment of childhood epilepsy.

TABLE 20.1

Mean Percentage of Baseline Seizure Numbers at 3, 6, and 12 Months in Classic and MCT Diet Groups

So how does the MCT diet work in practice? The MCT is given in the diet as a commercially available MCT oil or emulsion (Liquigen®, SHS in Europe). Both are available by prescription in the United Kingdom. The amount of MCT has to be calculated into the diet just like any other fat and should be divided up over the day and included in all meals and snacks; the amount will be specified in the diet prescription provided by the dietician. Liquigen® can be mixed with milk for an MCT milk drink (best with skimmed or semi-skimmed milk as full fat milk causes the mixture to thicken excessively); it can also be added to foods such as soups and mashed potato, or used in recipes, ranging from sugar-free jelly, sauces, and baking. MCT oil also works well in meal preparation and baking, A number of recipes are available from the Matthew’s Friends Web site (www.matthewsfriends.org), which give ideas for MCT meals and snacks. MCT has a low flashpoint, so be cautious when frying, and keep the temperature fairly low!

Because the diet allows more carbohydrate and protein, a child on the MCT diet can eat a wider variety of other, antiketogenic foods. Protein portions are more generous than with the classic diet, as are the allowed amounts of fruit and vegetables. Small amounts of higher carbohydrate foods, such as bread, potatoes and cereals, can also be calculated into the daily allowance. As with the classic diet, sweet and sugary foods are not allowed, and calories will still be controlled. Although exact recipes can be calculated for the MCT, many centers will instead use food exchange lists because of the more generous amounts of carbohydrate and protein. The use of separate carbohydrate, protein, and fat exchanges is recommended because this allows an even macronutrient distribution over the meals and snacks. As with the classic ketogenic diet, full vitamin, mineral, and trace element supplementation must be given. The prescribed diet must also meet essential fatty acid requirements.

The MCT diet can be provided as a tube feed for children who need it, but there is not one complete product available as there is for the classic diet, so the prescription and the preparation of such a feed will be much more complicated. For this reason, use of the classic ketogenic diet feed products is preferable.

On commencing the MCT diet, the Liquigen® or MCT oil needs to be introduced much more slowly than long chain fat (over about 5–10 days), as it may cause abdominal discomfort, vomiting, or diarrhea if introduced rapidly. During this introduction period the rest of the diet can be given as prescribed, but an extra meal may be needed to make up the calories while using less MCT. Once on the full diet, children must stick with it just as rigidly as with the classic diet. Fine-tuning is usually needed to maximize benefit and tolerance. This is done by increasing or decreasing the amount of calories provided by MCT; the amount of long chain fat can be adjusted to keep the same total calories from fat in the diet. If a higher level of ketosis is desired and an increased amount of MCT is not tolerated, the amount of carbohydrate in the diet can be reduced and long chain fat increased to balance calories.

Discontinuing the MCT diet should be done in a stepwise process. The amount of MCT fat should be slowly reduced, and the protein and carbohydrate increased. However, if the MCT diet works, as with the classic diet, children stay on it for about 2 years.

MCT oil in small amounts can also be used as a supplement to the classic ketogenic diet, both because it can increase ketosis and because it may decrease the constipation that often accompanies this diet. Swapping some of the long chain fat allowance for MCT can soften the stools of constipated children and in small amounts is well tolerated.