One of the central objectives of this book is to demonstrate that liberalism and religious fundamentalism are the two major ideological movements in the Middle East and North Africa. As alternative discourses, they have displayed opposing political and cultural orientations as they contend for intellectual control of the social order. There is little support for other competing ideologies, such as pan-Arab nationalism (in Arab countries), ethnic nationalism (except among the Kurds), communism or state socialism, and secular authoritarian nationalism.

The conflict between the two movements in the historical context of the contemporary Middle East and North Africa is reflected in the fight over issues. The Islamic fundamentalists have taken positions on important sociopolitical and cultural issues that were often diametrically opposed to the positions taken by liberal intellectual leaders and activists on the same issues. Contrary to those taking the liberal perspective, the advocates of Islamic fundamentalism have predominantly rejected secular politics in favor of the unity of religion and politics in an Islamic government; defended the institution of male supremacy and patriarchy; portrayed Western culture as decadent; considered religion as the principal, if not the only, source of social norms and legislation; and forcefully delineated religion, rather than the territorial nation, as the basis of identity, claiming that the political community to which the diverse peoples of the region belong is an Islamic nation (ummat), rather than one bounded by and identified with their territories. Symptomatic of the depth and breadth of this conflict is the existence of active ideological debates and political disputes over these issues in many Middle Eastern and North African countries—in Iran, in particular. The relative numbers of individuals or the sizes of the groups associated with the opposing positions on these issues are an indicator of the extent of support for each of the two opposing cultural movements, providing useful data on whether the society is oriented toward religious fundamentalism or liberal values (Moaddel 2005).

What makes a religious movement fundamentalist is not simply the position of its leaders on issues, however. Except for the rejection of secular politics in favor of the unity of religion and politics and adherence to religious identity, there is nothing specifically religiously fundamentalist in the view that espouses patriarchy and male supremacy, chastises expressive individualism, and rejects Western culture as decadent. Therefore, a more effective measure of religious fundamentalism is one that captures its distinctive religious character and is defined in religious terms.1 Adhering to this stipulation, religious fundamentalism is defined here as a set of beliefs about and attitudes toward one’s and others’ religions that is based on a disciplinarian conception of the deity, literalism, religious exclusivity, and religious intolerance. This conceptualization allows for comparing fundamentalism across religions and religious sects. Fundamentalists in Christianity and Islam and in Shia and Sunni share these core orientations despite the fact that, in their concrete and specific historical context, Christian fundamentalists have irreconcilable differences with their Muslim counterparts, as do Shias with Sunnis. Moreover, as this chapter shows, individuals who have fundamentalist orientations, based on this religious definition of the term, are more likely to reject secular politics, recognize religion as the basis of identity, defend the institution of male supremacy and patriarchy, and consider Western culture decadent. Individuals with stronger fundamentalist orientations would thus be less favorable toward the liberal values of expressive individualism, gender equality, and secular politics. Positions on issues are, however, the predictors of fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes, not measures of such beliefs and attitudes.

This chapter first advances a multidimensional conception of religious fundamentalism and measures its different components. It then shows that (1) the measures of the constructs are negatively correlated with the measures of liberal values—expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and national identity—and (2) on the micro (individual) level, the factors that are positively linked to religious fundamentalism are negatively connected to liberal values, and vice versa. Chapter 5 will show that on the macro (country) level, the variables that are positively linked to religious fundamentalism have negative relationships with the measures of the liberal values as well.

Religious fundamentalism is conceptualized as a distinctive set of beliefs about and attitudes toward whatever religious beliefs one has. It is a multidimensional construct consisting of four components: (1) a disciplinarian conception of the deity, (2) literalism or inerrancy, (3) religious exclusivity, and (4) religious intolerance. Using this conceptualization, religious fundamentalism is first measured in terms of a series of survey questions. Then cross-national variation in religious fundamentalism, its relationship with liberal values, and variation by age, gender, education, religion, and religious sect are analyzed. Finally, the predictors of religious fundamentalism on the micro (individual) level are examined across the seven countries.

Historical and Cross-National Diversity of Islamic Fundamentalism

An important characteristic of religious fundamentalist movements is that they vary greatly in different historical periods, across nations, and by religious faiths. In the modern period, Islamic fundamentalism emerged as a potent oppositional force in two distinctive cultural episodes. The first consisted of the militant fundamentalism of Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1787) in Arabia and the reformist fundamentalism of Shah Waliallah (1703–1762) in India in the eighteenth century. These two movements arose in the context of the decline of Muslim politics—the gradual falling of the Ottomans in Asia Minor and the Mughals in India—and were aided by the political vacuum that this decline generated.2 The objective of the two Muslim thinkers, their associates, and their disciples was to purify the faith by rejecting what they considered to be the un-Islamic beliefs and practices that had crept into the Islamic way of life. They questioned the static formalism of the orthodox Islamic jurisprudence, rejected the interpretive functions of the ulama, and claimed the scriptures should be accessible to ordinary individual Muslims. They wanted to transform the state of affairs currently existing in their political communities to align with the political order that had existed under the first generation of Muslim leaders. Their efforts favored strengthening the literalist reading of the Quran and the hadith (the dicta attributed to Prophet Muhammad) and promoting a religion-centric and exclusivist conception of the Islamic community. The Wahhabis, in particular, exhibited an intolerant view of all sects in Islam other than the Sunni.

These teachings shaped the rise of militant movements that sought to rehabilitate Islam in Arabia and India. The Wahhabi militants gained control of central Arabia, occupied the Hijaz, sacked the Iraqi city of Karbala, and massacred thousands of Shias living in the area. They were, however, defeated by the forces of Muhammad Ali, the khedive (viceroy) of Egypt, who at the request of the Ottoman sultan destroyed the Wahhabi power in the early nineteenth century. The Indian militants faced the same fate as their Wahhabi counterparts. The Indian movement, labeled Wahhabi by the British and mujahidin by its followers, was led by Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi (1786–1831), a disciple of Shah Waliallah’s son and successor, Abdul Aziz, whose circle he joined in 1807. Two learned scions of the family of Shah Waliallah, Shah Ismail and Abdul Hayy, joined him as his disciples, marking the progress of Shah Waliallah’s program “from theory to practice, from life contemplative to life active, from instruction of the elite to the emancipation of the masses, and from individual salvation to social organization” (Ahmad 1964, 210; Lapidus 1988). Barelvi declared as dar ul-harb (the abode of war) the Indian territories that were occupied by the British and other non-Muslim forces, and he called on the regional Muslims to join him in a holy war against the infidels. The movement, however, was crushed by the British in 1858, suffered another defeat in 1863, and was persecuted throughout India in the same period (Ahmad 1964, 1967; Hardy 1972).

The second Islamic fundamentalist episode is separated from the first by more than a century in the Arab world—from the Wahhabi defeat in 1818 to the formation of the Society of the Muslim Brothers in 1928 and the establishment of the Wahhabi-inspired and supported Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932—and by about three-quarters of a century in Asia—from the defeat of the Indian mujahedin around 1863 to the formation of Jamaati Islami in India in 1941 and in Pakistan in 1947. The interregnum is characterized by the decline of sacred spirituality, the Islamic orthodoxy and the ulama, and religion as an organizing principle of social order, on the one hand, and by the rise of secular spirituality, science, and evolutionary ideologies, on the other (Moaddel and Karabenick 2013). Muslim intellectual leaders, influenced by the nineteenth century’s seminal ideas of evolutionary progress and civilizational change and impressed by remarkable scientific discoveries and technological innovation during this period, launched widespread efforts to reexamine Islamic worldviews in light of these changes and the intellectual standard of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. Their efforts resulted in Islamic modernism, a new set of religious ideas and treatises generated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Islamic modernist movement was stronger in places like late nineteenth-century Egypt and India, where the cultural context was diversified, and where the encounter with Western culture contributed in turning some of the taken-for-granted principles of social organization and deeply held beliefs into issues, including revelation versus reason, religion versus nationhood as the basis of identity, monarchical absolutism versus constitutional government, gender hierarchization and male supremacy versus gender equality, and the West as culturally inferior or decadent versus the West as the civilized order. Islamic modernism was an outcome of the religious disputations and ideological debates that transpired over these issues among such cultural or religious groups as the followers of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, modern indigenous intellectual leaders, Christian missionaries, and the think tanks connected to colonial administrations. The criticisms leveled against the Islamic faith by evangelical Christianity, on the one hand, and by the followers of the Enlightenment, on the other, prompted a significant number of Muslim intellectual leaders–cum–theologians to reexamine the traditional sources of Islamic jurisprudence in light of the Enlightenment’s intellectual standards. The principal issues that engaged these Muslim thinkers revolved around whether the knowledge derived from the sources external to Islam was valid and whether the four traditional sources of jurisprudence were methodologically adequate to effectively address the challenges posed to their faith. Considering these traditional sources—the Quran, the dicta attributed to Prophet Muhammad (hadith), the consensus of the theologians (ijma), and juristic reasoning by analogy (qiyas)—they resolved to advance a modernist exegesis of the first two sources and to transform the last two in order to formulate a reformist project in light of the prevailing standards of scientific rationality. Such prominent intellectuals and theologians as Sayyid Jamal ud-Din al-Afghani, Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, Chiragh Ali, Muhammad Abduh, Amir Ali, Shibli Nu’mani, and Mirza Muhammad Hussein Gharavi Naini presented Islamic theology in a manner consistent with modern rationalist ideas. Some of these thinkers claimed that Islam was compatible with deistic and natural religion. They applauded the achievements of the West in science and technology as well as its constitutional form of government. They all argued that Islam, as a world religion, was thoroughly capable of adapting itself to the changing conditions of every age, the hallmarks of the perfect Muslim community being law and reason (Ahmad 1967; Hourani 1983; Moaddel 2005).

The liberal nationalist movements, of which Islamic modernism was an integral part, resulted in the formation of secular states from the early 1920s on. Although the lifespan of liberal government in the Middle East and North Africa was short, the secular trend unleashed by the revolutionary or national liberation movements in the early twentieth century continued unabated until the seventies. In certain countries like Egypt, Iran, and Turkey, secularism turned overly critical of the religious establishment, which in turn begot a fundamentalist response. The major fundamentalist challenges to the secular order were launched by the Society of the Muslim Brothers in Egypt in 1928 and in other Arab countries in the subsequent decades; by Jamaati Islami (Islamic Congregation) in India in 1941, in Pakistan in 1947, and in Kashmir and Bangladesh in the subsequent decades; and by a terrorist organization named Fedaiyane Islam (Self-Sacrificers of Islam) in Iran in 1946. As was discussed in the introductory chapter, the transformation of Islamic fundamentalism into a worldwide influential religious nationalist movement was a result of four historical events that occurred almost simultaneously: (1) The military coup by General Zia ul-Haq in Pakistan in 1977, which expanded the fundamentalists’ influence in the country; (2) the Iranian Revolution of 1979, which brought Shia fundamentalists to power; (3) the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which gave legitimacy to the fundamentalists’ call for jihad as fadr al-ayn (the necessary duty incumbent upon all Muslims) against the invaders; and (4) the 1979 seizure of the Great Mosque in Mecca by Muslim militants, which demonstrated the vulnerability of the Saudi kingdom. Although each of these events was the outcome of nationally specific historical dynamics and social conditions (Moaddel 1993, 2006; Okruhlik 2002; Alavi 2009), the concurrence of the four events gave the impression of a worldwide unitary Islamic resurgence, often referred to as “Islamic awakening,” and contributed to the popularization of fundamentalist ideas and practices among a significant number of Muslim political activists the world over.

The outcome of the Iranian Revolution demonstrated the degeneration of Islamic fundamentalism into the repressive totalitarian ideology of the Islamic Republic of Iran. In the early twenty-first century, Islamic fundamentalism further degenerated into militant Shia and Sunni sectarianism, political violence, and suicide terrorism. These movements, however, have been widely differentiated, as they are represented by numerous diverse religious organizations: Sunni Islam by the Society of the Muslim Brothers in Egypt and its affiliated organizations in other Arab countries, Jamaati Islami in Pakistan, Front Islamique du Salut (FIS) in Algeria, the Taliban in Afghanistan, the National Islamic Front in Sudan, Hamas in the Gaza Strip, al-Shabaab in Somalia, and Boko Haram in Nigeria; and Shia Islam by the Iranian Fedaiyan-e Islam and the followers of Ayatollah Khomeini, the Lebanese Hezbollah, and the Yemeni Houthis. Also included are myriad Islamic extremist and suicide terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda and more recently the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria that have emerged in the region, primarily since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001 (Ahmad 1964; Mitchell 1969; Sivan 1985; Kepel 1985; Roy 1994; Almond, Appleby, and Sivan 2002; Moaddel and Karabenick 2013).

Conceptual Development

Despite their diversity, these fundamentalist movements, as well as their Christian counterparts, share a set of core orientations toward their own and other religions. The first is a preoccupation with God’s discipline and retributive character—God’s rewards in heaven, the fear of punishment in hell, and Satan’s scheme. The second is the tendency toward literalism, the belief that the scriptures are inerrant and literally true. The third is an orientation toward religious centrism or an exclusivist view of their religious community. The fourth is a degree of religious intolerance; fundamentalists tend to exhibit an intolerant view not only of other religions but also of religious sects other than their own. Drawing on these shared features, religious fundamentalism is conceptualized as a set of distinctive beliefs about and attitudes toward whatever religion one has (Altemeyer 2003; Altemeyer and Hunsberger 2004; Schwartz and Lindley 2005; Summers 2006; Moaddel and Karabenick 2008, 2013, 2018). The belief in God, for example, is a religious belief; the belief in the oneness of God is specifically Islamic; and the belief in the Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit is specifically Christian. But the beliefs that one’s own religion is closer to God than other religions, that only the followers of one’s religion will go to heaven, that one’s religious community should have more rights than other communities, and that God severely punishes people even though they have engaged in only a minor infraction of religious laws are all conceptualized as fundamentalist beliefs, for they display distinctive orientations toward one’s religion rather than being the beliefs or principles adhered to by the followers of a specific religion.

Fundamentalism is thus a multidimensional concept consisting of four components: (1) a disciplinarian deity, the belief in an almighty God who is fearful and severely punishes in hell those who fail to follow his instructions; (2) the literal nature of the scriptures, the belief that the scriptures are a comprehensive system of universal truth, having historical accuracy; (3) religious exclusivity and religious centrism, the belief that one’s faith is superior to other faiths and that one’s religious community must have more rights than other religious communities; and (4) religious intolerance, the belief that the followers of other faiths must be restricted in practicing their religions and that no one should be allowed to criticize one’s faith or the religious authorities. As will be shown, these components are conterminous with one another and form a single fundamentalism construct.

Measurement of Religious Fundamentalism

The four components of religious fundamentalism were operationalized in terms of sixteen survey questions that were intended to grasp the multiple meanings linked to each of the components. These questions had a Likert-scale response format (coded as strongly agree = 1, agree = 2, disagree = 3, and strongly disagree = 4). Muslim respondents were asked about the Quran, Islam, and Muslims, while Christian respondents were asked about the Bible, Christianity, and Christians. Although some of the questions were not allowed in Egypt, no more than one question was excluded from each component, identified by * in the following list, so the remaining questions were deemed sufficient to provide stable estimates of each component. Four survey questions measured each of the four components of religious fundamentalism, designated as disciplinarian deity, literalism, religious exclusivity, and religious intolerance. The response categories for these questions were recoded (strongly agree = 4, agree = 3, disagree = 2, and strongly disagree = 1) so that those who scored higher on the scale indicated having stronger fundamentalism orientations. Principal components analysis (PCA) of the question responses across all countries combined resulted in a single-factor solution (i.e., only one factor with an eigenvalue > 1) for each of the components: disciplinarian deity = 2.06, literalism = 2.05, religious exclusivity = 2.25, and religious intolerance = 1.84. The question responses in each component were then averaged, yielding a single score for each of the four components. A second PCA of these four means yielded a single factor with an eigenvalue of 2.41 that explained 60 percent of the variance. The four means were then averaged to create a single fundamentalism index that balanced the four components of fundamentalism. Using the sixteen questions, internal consistency estimates (Cronbach’s α) were well within the 0.70 to 0.90 range, which is considered satisfactory, for all the countries separately, except for Egypt, where the estimate was slightly lower but still acceptable: Turkey = 0.88, Lebanon = 0.88, Iraq = 0.84, Tunisia = 0.80, Saudi Arabia = 0.80, Pakistan = 0.72, and Egypt = 0.65. Reliability (α) was 0.84 when all countries but Egypt were combined and 0.80 when Egypt was included (but with the excluded items).

The distribution of the sixteen questions in the four components is as follows:

Please tell me if you (1) strongly agree, (2) agree, (3) disagree, or (4) strongly disagree with the following statements:

Disciplinarian Deity: Reward and Punishment from, and Fear of, God

• Any infraction of religious instruction will bring about Allah’s severe punishment.

• Only the fear of Allah keeps people on the right path.*

• Satan is behind any attempt to undermine the belief in Allah.

• People stay on the right path only because they expect to be rewarded in heaven.

Literalism: The Literal Truth, Accuracy, and Comprehensiveness of the Scriptures

• The Quran [Bible] is true from beginning to end.

• The Quran [Bible] has correctly predicted all the major events that have occurred in human history.*

• In the presence of the Quran [Bible], there is no need for man-made laws.

• Whenever there is a conflict between religion and science, religion is always right.

Religious Exclusivity: The Uniqueness and Superiority of One’s Religion

• Only Islam [Christianity] provides comprehensive truth about Allah.

• Only Islam [Christianity] gives a complete and unfailing guide to human salvation.

• Only Muslims [Christians] are going to heaven.

• Islam [Christianity] is the only true religion.*

Religious Intolerance: Nonrecognition of the Rights of Others’ Religions and Criticism of Religion

• Our children should not be allowed to learn about other religions.

• The followers of other religions should not have the same rights as mine.

• Criticism of Islam [Christianity] should not be tolerated.

• Criticism of Muslim [Christian] religious leaders should not be tolerated.

Cross-National Variation

Table 4.1 provides the distribution of the responses to the sixteen questions organized into the four components of religious fundamentalism, an index for each component, and an overall religious fundamentalism index across the seven countries. The index for each of the four components is the average of the numerical responses to the four questions that measure that component, and the overall religious fundamentalism index is the average of all sixteen responses (or the average of the four component indices). All indices range between 1 and 4. A score of 1 indicates strong disagreement with the beliefs and attitudes expressed in the fundamentalism items; thus, it denotes a religious orientation that is counter to religious fundamentalism. A score of 4 indicates strong agreement with or support for the beliefs and attitudes expressed in the fundamentalism items; it is religious fundamentalism proper. A median value of 2.5 for the religious fundamentalism index indicates neither disagreement nor agreement with religious fundamentalism. An aggregate median index of 2.5 for a country means that there are as many respondents in that country who adhere to fundamentalist beliefs as there are who believe otherwise. Any value that is significantly above or below this median value indicates that the respondents on average are predominantly oriented either toward or against religious fundamentalism, respectively.

TABLE 4.1 Measures of Religious Fundamentalism (Strongly Agree/Agree)

The percentages of those who strongly agree or agree with each of the fundamentalism questions were combined, and the results are reported in table 4.1. It is clear that support for religious fundamentalism is fairly strong in these countries. Respondents who strongly agreed or agreed with the disciplinarian deity items range between 98 percent among Egyptians and 64 percent among Lebanese, with literalism between 100 percent among Pakistanis and Saudis and 47 percent among Turkish respondents, with religious exclusivity between 98 percent among Pakistanis and 47 percent among Lebanese, and with religious intolerance between 9 percent among Pakistanis and 86 percent among Pakistanis and Saudis. The index values for three of the indices—disciplinarian deity, literalism, and religious exclusivity—are significantly higher than 2.5 across the seven countries. That is, the disciplinarian deity index varies between 2.98 for Lebanese and 3.77 for Egyptians, the literalism index between 3.02 for Lebanese and 3.69 for Egyptians and Pakistanis, and the religious exclusivity index between 2.85 for Lebanese and 3.69 for Pakistanis. Based on these three measures, the respondents from the seven countries display fairly strong fundamentalist orientations, although this strength varies among these countries. The values of the religious intolerance index, however, are much lower than 2.5 across the countries, ranging between 2.26 among Tunisians and 3.09 among Saudis.

The questions measuring religious intolerance provide a more varied picture of religious fundamentalism across the seven countries. These questions can be divided into two subcategories. One, which can be labeled interfaith intolerance, included these two questions: (1) “Our children should not be allowed to learn about other religions,” and (2) “The followers of other religions should not have the same rights as mine.” These questions measure the extent to which one is tolerant of other religion. Findings indicate that the respondents were significantly more tolerant than intolerant, except among Saudi and Pakistani respondents: 63 percent of Pakistanis and 66 percent Saudis strongly agreed or agreed that “Our children should not be allowed to learn about other religions” and 73 percent of Saudis strongly agreed or agreed that “The followers of other religions should not have the same rights as mine.” In the other countries, only a minority of respondents conformed to these intolerant beliefs, ranging from 45 percent of Egyptians to 9 percent of Pakistanis. The other subcategory, which can be defined as antiauthoritarian intolerance, included these two questions: (3) “Criticism of Islam [Christianity (for Christian respondents)] should not be tolerated,” and (4) “Criticism of Muslim religious leaders [Christian religious leaders (for Christian respondents)] should not be tolerated.” These questions measured the extent to which the respondents were intolerant of expressions that are critical of one’s religion or religious authorities. The strongly agree and agree responses to the third question vary between 65 percent among Lebanese and 86 percent among Pakistanis and Saudis; these responses to the fourth question vary between 30 percent among Tunisians and 76 percent among Saudis. Much higher percentages of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with questions 3 and 4 than strongly agreed or agreed with questions 1 and 2. These differences thus show that, while respondents displayed a willingness to tolerate the followers of other faiths, they were quite intolerant of criticisms of their religion and religious leaders.

Only respondents from Lebanon and Tunisia, with religious intolerance index values of 2.37 and 2.26, respectively, can be considered as tolerant, while those from the other countries cannot be considered so at the time the surveys were completed, assuming that the survey items were adequate. Nonetheless, the level of support for religious intolerance among the respondents was much lower than support for the other three components of religious fundamentalism across the seven countries. The difference between those three indices and the religious intolerance index may suggest that any significant change in religious attitudes across these countries toward religious modernity and tolerance may begin with further decline in the level of intolerance. (This hypothesis is in fact supported by findings from two waves of panel surveys carried out in Egypt, Tunisia, and Turkey, as will be shown in chapter 6.)

The overall religious fundamentalism index, which is based on the average of all sixteen items (or the average of the four component indices), shows strong support for fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes among the respondents across the seven countries. The measure also displays cross-national variation. Post hoc analysis of variance (F = 822.53, p < .001) confirms significant differences in the religious fundamentalism index by country, with Scheffé’s test showing that Egyptians and Pakistanis reported the highest levels of fundamentalism, with mean index values of 3.44 and 3.42, respectively, which were statistically nearly identical. They are followed by respondents from Saudi Arabia, with a religious fundamentalism index of 3.33; Iraq, with 3.28; Tunisia, with 3.18; Turkey, with 2.98; and Lebanon, with 2.80. Between-country differences in religious fundamentalism across these last five countries are statistically significant.

Variation by Age, Gender, and Education

Age

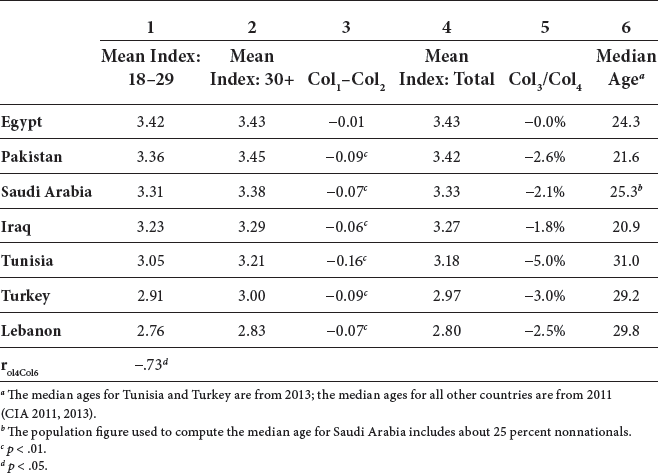

Table 4.2 shows that the age differences in the religious fundamentalism index are statistically significant for all the countries, except Egypt. It indicates that individuals in the youth bulge (aged 18–29) were less strongly fundamentalist than were those in the older age group (aged 30 and older). The table also shows that countries that have a smaller youth bulge (i.e., those that have a higher median age) were significantly less fundamentalist than were those with a large youth bulge (r = −.73). Thus, while it is true that the younger individuals had weaker fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes, the opposite is true of countries with younger populations. That is, countries with younger populations exhibited on average stronger support for religious fundamentalism.

TABLE 4.2 Age Differences in Religious Fundamentalism Index and Median Age by Country

Figure 4.1 shows the values of the religious fundamentalism index for men and women. Lebanese, Tunisian, and Saudi women were significantly more fundamentalist than were their male counterparts. Using independent samples t-tests for differences in the religious fundamentalism index by gender, the difference in Lebanon was significant at p < .001, in Saudi Arabia at p < .001, and in Tunisia at p < .05. (Although the difference in fundamentalism in Turkey is about the same as it is in Tunisia, this difference is not statistically significant in Turkey). In the other countries, however, there were no significant gender differences in fundamentalism.

Figure 4.1 Religious Fundamentalism Index by Gender.

There were significance differences in the religious fundamentalism index by age but not by gender, except among Lebanese, Saudi, and Tunisian respondents. Thus, there is no need to break down the religious fundamentalism index by gender and age.

Education

Figure 4.2 shows the variation in religious fundamentalism by education across the seven countries. People with university education had significantly weaker fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes than did people without university education across all countries, except for Saudi Arabia, where this difference was not statistically significant. The magnitude of this difference was greatest in Turkey (0.37), followed by Tunisia (0.32), Lebanon (0.18), Egypt (0.13), Pakistan (0.12), Iraq (0.08), and Saudi Arabia (0.06). It appears that university education had a greater effect in weakening fundamentalism in the more liberal countries of Turkey, Tunisia, and Lebanon (similar to its effect on liberal values, except among Pakistanis, noted in chapter 3) than in the more conservative countries of Egypt, Pakistan, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. This finding thus suggests that the effect of education on fundamentalism is mediated by the cultural-cum-authoritarian context; that is, education has stronger negative effects on fundamentalism in more open and less authoritarian environments. Independent samples t-tests for differences in the religious fundamentalism index by education show significance for Iraq at p < .01 and for Lebanon, Pakistan, Tunisia, Egypt, and Turkey at p < .001.

Figure 4.2 Religious Fundamentalism Index by Education.

Education and Age

Table 4.3 shows variation in the religious fundamentalism index by age and education across the seven countries. People with university education were significantly less fundamentalist across both age categories among respondents from Egypt, Lebanon, Pakistan, Tunisia, and Turkey. Among Iraqis, university education significantly reduced fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes only among the older age group, and among Saudis, it had no significant effect on religious fundamentalism among respondents from either age group.

TABLE 4.3 Religious Fundamentalism Index by Age and Education (Mean/Standard Deviation; n)

Variation by Religion

Table 4.4 compares the indices of disciplinarian deity, literalism, religious exclusivity, religious intolerance, and religious fundamentalism by religion and religious sects—Christians, Shia Muslims, and Sunni Muslims—across six countries: Egypt, Lebanon, Iraq, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Tunisia is excluded from this table because over 99 percent of its population was Sunni Muslims and the numbers of religious minorities in the Tunisian sample were thus negligible. As this table shows, in Egypt and Lebanon, Christians scored lower than Sunnis and Shias on each of the four indices of the components of religious fundamentalism, and in Lebanon, Iraq, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, Shias scored lower than Sunnis, except that Iraqi Shias and Sunnis scored almost the same on the index of literalism. Lebanese Christians and Turkish Shias (mainly Alavis) had religious intolerance index scores of 2.28 and 2.25, respectively, making them the least intolerant (or the most tolerant), and Saudi Sunnis had a religious intolerance index score of 3.15, making them the most intolerant (or the least tolerant) group in the samples.

TABLE 4.4 Indices of Religious Fundamentalism and its Components by Religion (Mean/Standard Deviation)

Considering the religious fundamentalism index, Christians were also less fundamentalist than Sunnis and Shias in Lebanon and Sunnis in Egypt. Lebanese Christians were considerably less fundamentalist than Egyptian Christians, indicating the effect of the liberal and pluralistic context of Lebanon on fundamentalism. Shias were significantly less fundamentalist than Sunnis across the samples from Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. The magnitude of the Sunni-Shia difference on fundamentalism was 0.80 among Saudi respondents. This difference was 0.34 for Turkey, 0.15 for Pakistan, 0.14 for Lebanon, and 0.07 for Iraq. One of the most remarkable findings of this study is that, with a religious fundamentalism index score of 2.59, Saudi Shias were the least fundamentalist group across both the religions and the religious sects reported in this table (the difference in religious fundamentalism between Saudi Shias and Lebanese Christians, who had a score of 2.62, however, is not statistically significant), and Egyptian and Pakistani Sunnis, who scored 3.44 on this index, were the most fundamentalist.

These differences in fundamentalism between the members of the religious minorities and the religious majority may indicate that the minorities, in trying to accommodate the religious majority and reduce tension, have espoused a more moderate approach to religion and thus have developed a weaker fundamentalist orientation. The stronger fundamentalism among members of the majority religion, on the other hand, may reflect their claim to a greater ownership of religion and the perception that the religious minorities have deviated from the true path and are therefore posing a threat to their religion.

Variation by Religion and Gender

Although not reported in the tables, the analysis showed that across religions and religious sects, respondents in the youth bulge were either less fundamentalist than or displayed no difference from those in the older age group. Also university education generally had negative effects on fundamentalism across Christianity and Shia and Sunni Islam.

Table 4.5 reports differences in religious fundamentalism by religion and gender. Both Shia and Sunni women were more strongly fundamentalist than men in Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, but there were no gender differences across these two sects in Iraq, Pakistan, Egypt, and Turkey. Among Christian respondents in Egypt and Lebanon, there were no significant differences in fundamentalism between male and female respondents. Again, Tunisia is excluded from this analysis because more than 99 percent of its population adhered to the Sunni sect.

TABLE 4.5 Religious Fundamentalism Index by Religion and Gender

Religious Fundamentalism Versus Liberal Values

Consistent with the argument that, in the context of the contemporary Middle East and North Africa, supporters of Islamic fundamentalism and liberal activists stand on opposite sides of significant sociopolitical and cultural issues, the analysis of the pooled survey data showed that the indices of religious fundamentalism and its components are inversely related to the indices of liberal values and its components. That is, the indices of fundamentalism, disciplinarian deity, literalism, religious exclusivity, and religious intolerance are all inversely linked to the indices of liberal values, expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and national identity. The data reported in table 4.6 confirm the inverse relationships between the measures of both constructs.

TABLE 4.6 Correlation Coefficients Between Components of Liberal Values and Religious Fundamentalism in the Pooled Data

The strongest correlation is between the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values (r = −.56), indicating the superiority of either of these composite indices over any of the measures of the four components. Among the components of liberal values, religious fundamentalism has strongest inverse correlation with secular politics (r = −.46), followed by gender equality (r = −.40), then expressive individualism (r = −.37), and finally national identity (r = −.26), which has the weakest correlation. The strength of these correlation coefficients may reflect the intensity of the clash between fundamentalism and these components of liberal values. These varying relationships imply that respondents may have a clearer idea about their stance on secular politics and gender equality than they do on expressive individualism. On identity, while the respondents who identify with the nation rather than religion, tend to be more liberal and less fundamentalist, national identity is not as clear mark of distinction between the two conflicting values than other measures. In some cases nationalism and fundamentalism may merge into a single authoritarian religious nationalist movement. This fact explains why the correlation coefficient between fundamentalism and national identity is weakest (r = −.26). In fact, among the components of liberal values, the national identity index had the weakest relationships with the components of fundamentalism (with correlation coefficients ranging between −.10 and −.24).

Finally, compared to other components of fundamentalism, the religious intolerance index had the weakest relationships with the components of liberal values, including national identity (with correlation coefficients ranging between −.10 and −.29). Again, while fundamentalists appeared to have a strong and clear view on the disciplinarian conception of the deity, literalism, and exclusivity, they are not consistently intolerant. All these correlation coefficients are, however, statistically significant (p < .001).

Cross-National Variation in the Fundamentalism-Liberalism Relationship

Conceptually, religious fundamentalism and liberalism are opposing discourses. Empirically, however, the inverse relationship between the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values is far from perfect. This is not simply because individuals vary in terms of their orientations toward liberalism or fundamentalism. Rather, an individual may not be fundamentalist or liberal on all the issues. As shown in table 4.6, respondents expressed much stronger fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes on items related to the disciplinarian deity, literalism, and religious exclusivity than they did on items related to religious intolerance. Likewise, a respondent may be strongly supportive of secular politics but not as strongly supportive of gender equality. Finally, as demonstrated by public opinion research, individuals may simultaneously hold values that clash (Sniderman, Tetlock, and Carmines 1993). They may be strongly fundamentalist on one index but liberal on another.

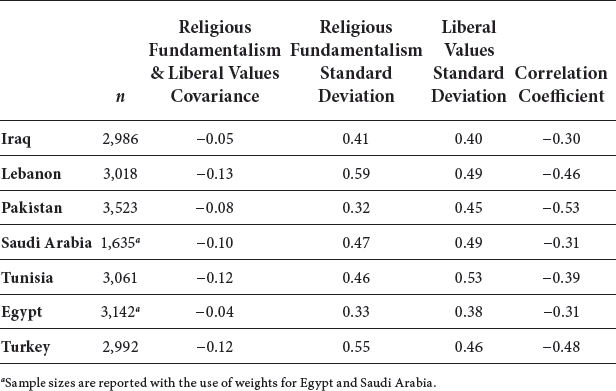

The strength of the correlations between the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values also varies by country. According to table 4.7, across the seven countries, this coefficient is highest among Pakistani respondents (r = −.53), followed by Turkish, Lebanese, Tunisian, Saudi, Egyptian, and Iraqi respondents (r = −.48, −.46, −.39 −.31, −.31, and −.30, respectively). Researchers have pointed to six factors that affect the size of a correlation coefficient: (1) the amount of variability in the data, (2) differences in the shapes of the two distributions, (3) lack of linearity, (4) the presence of outliers, (5) the characteristics of the sample, and (6) measurement error (Goodwin and Leech 2006). Here the same measures were used across the seven countries, the religious fundamentalism items were extensively pretested before being used in the surveys, and almost all the items measuring liberal values were used in the previous surveys in the region and in the World Values Surveys. Efforts were also made to keep the samples comparable, although the quality of the sample data was better in some countries than in others. The research design attempted to address factors 5 and 6. Also a lack of linearity and the presence of outliers (factors 3 and 4) were ruled out as factors explaining cross-national variation in the size of the correlation coefficients.

TABLE 4.7 Covariances, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Coefficients for the Indices of Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values

However, substantively, the characteristics of the national context may affect the variability in the data and the shape of the distribution of the variables of interests (factors 1 and 2). It was proposed that the inverse relationship between the two indices would be larger in countries where people more readily witnessed or experienced fundamentalism-liberalism debates. Probably, respondents in relatively more open and liberal countries like Lebanon, Turkey, and Tunisia were often exposed to such debates and, as a result, might be able to develop a clearer stance on one side or the other of the issues being debated, but each side might not necessarily adopt a more homogeneous set of attitudes (probably because open debates and discussions tend to direct individuals toward compromise and thus toward taking more moderate positions on issues, increasing the variability of the indices). Empirically, given the formula for the Pearson correlation coefficient,

a clear stance might produce a higher covariance between the indices of the two constructs, and homogeneous or heterogeneous attitudes toward issues might be translated into smaller or larger standard deviations for the indices. Table 4.7 shows that the covariances between the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values are higher for Lebanon (−0.13), Turkey (−0.12), and Tunisia (−0.12) than they are for the more conservative countries of Egypt (−0.04), Iraq (−0.05), and Pakistan (−0.08). As a result, the correlation coefficients for Lebanon, Turkey, and Tunisia remain higher than those for Egypt and Iraq. Saudi Arabia is an intrusive religious regime. Nonetheless, Saudis appeared to have developed keen awareness of the difference between religious fundamentalism and liberal values. This may explain a relatively higher value for the covariance between the two indices for Saudi Arabia (−0.10), resulting in a high correlation coefficient. The covariance value for Pakistan is low (−0.08), but for the index of religious fundamentalism, it has the lowest standard deviation (0.32), and for the index of liberal values, it has the third-smallest standard deviation (0.45); only Egypt (0.38) and Iraq (0.40) have smaller standard deviations for the liberal values index. As a result, the size of the denominator is reduced for Pakistan, indicating a higher correlation between the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values for Pakistan than for the other six countries. This may suggest that in Pakistan, a highly homogenous fundamentalism faces a moderately homogeneous liberalism.

Societal Support for Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values

Conceptually, fundamentalism and liberalism are incompatible discourses. Empirically, however, the fundamentalism-liberalism division is rarely reflected in the formation of two organized and culturally distinct groups. An ambiguous, cross-nationally variable intersection blurs the line of conceptual demarcation, making it hard to recognize the point where fundamentalism ends and liberalism begins. Some individuals tend to display both liberal and fundamentalist characteristics or are partly liberal and partly fundamentalist. Such individuals simultaneously adhere to values that clash, and their presence in society thus modifies the severity and intensity of the conflict between the two antagonistic ideological camps. Where the overlap is narrower or the gap wider, there is a higher likelihood of intense ideological conflict between the two groups.

To further clarify the relationship between religious fundamentalism and liberal values and to estimate the varying degrees to which individuals in the seven countries support either value orientation, the two indices were recoded into five categories. Those scored between 1 and 1.69 are labeled “strongly oppose” religious fundamentalism or liberal values, those between 1.70 and 2.39 “oppose,” those between 2.40 and 2.59 “neither oppose nor support,” those between 2.60 and 3.29 “support,” and those between 3.30 and 4 “strongly support.” The results for the two distributions are reported in tables 4.8 and 4.9.

TABLE 4.8 Distribution of Religious Fundamentalism Index

TABLE 4.9 Distribution of Liberal Values Index

The distribution of religious fundamentalism in the five categories in table 4.8 indicates that there were not very many respondents from Egypt, Iraq, Pakistan, or Saudi Arabia who opposed fundamentalism. There were no Egyptians and only 1 percent of Pakistanis, 4 percent of Iraqis, and 5 percent of Saudis who either strongly opposed or opposed fundamentalism. For the other three countries, these figures were higher; 23 percent of Lebanese, 6 percent of Tunisians, and 13 percent of Turkish respondents either strongly opposed or opposed fundamentalism. On the other hand, the percentages of those who strongly supported or supported fundamentalism were quite high, ranging between 65 percent among Lebanese and 99 percent among Egyptians. In the pooled sample, only 8 percent strongly opposed or opposed fundamentalism, while 87 percent strongly supported or supported it and 5 percent neither opposed nor supported it.

The distribution of the index of liberal values in table 4.9 shows much less support for liberal values across the seven countries. Those who strongly opposed or opposed liberal values ranged between 22 percent among Lebanese and 83 percent among Pakistanis. On the other hand, those who strongly supported or supported such values varied between 9 percent among Pakistanis and 67 percent among Lebanese.

The above comparison is useful in order to assess where these countries stood on religious fundamentalism and liberal values. Nonetheless, considering the distributions in tables 4.8 and 4.9, it is premature to conclude that, because there was a low level of support for liberal values and a high level of support for religious fundamentalism among the respondents, the future of liberalism in these countries is doomed and that, as Huntington (1996a) speculated, the chance that liberal democracy will rise in the Muslim world is nil. For a better understanding of the transformation of values toward liberal democracy, the measures of both constructs need to be modified. First, it should be noted that the high values for religious fundamentalism are a result of the high levels of support for a disciplinarian deity, literalism, and religious exclusivity. In comparison, support for religious intolerance (the fourth component of religious fundamentalism) was much lower across all seven countries. Also, it is known that an increase in the level of tolerance is necessary (but not necessarily sufficient) for liberal politics to become institutionalized and function effectively. Thus, a decline in the level of religious intolerance may be a better indicator of a change toward liberal democracy than an overall decline in religious fundamentalism. Low support for liberal values, on the other hand, is mainly due to low support for the component of expressive individualism. To make a more balanced comparison between the support for religious fundamentalism and that for liberal values, expressive individualism must be excluded from the measure and liberal values recalculated as an average of the indices of secular politics and gender equality. Then the distribution of this recalculated index of liberal values can be compared with the distribution of the index of religious intolerance. The results are reported in table 4.10.

TABLE 4.10 Distribution of Indices of Religious Intolerance and Liberal Values (%)

The distribution in table 4.10 portrays a more balanced picture of the status of liberal values versus religious fundamentalism. In the entire sample, 36 percent of respondents strongly opposed or opposed religious intolerance, while 49 percent strongly supported or supported it and 15 percent neither opposed not supported it. On the other hand, 49 percent strongly opposed or opposed liberal values, while 38 percent strongly supported or supported them and 13 percent neither opposed nor supported them. Comparing the relative support for religious intolerance versus that for liberal values, higher percentages of respondents were more strongly supportive or supportive of religious intolerance than they were of liberal values among Iraqis, 51 percent versus 27 percent; Pakistanis, 60 percent versus 14 percent; Saudis, 78 percent versus 7 percent; and Egyptians, 60 percent versus 19 percent. But the opposite was the case among Lebanese, 35 percent versus 65 percent; Tunisians, 29 percent versus 58 percent; and Turkish respondents, 45 percent versus 69 percent.

Comparing the support for religious intolerance and that for liberal values (measured as the average of the indices of secular politics and gender equality) is useful because changes in values are more likely to occur first in the religious intolerance component of religious fundamentalism and in the secular politics component of liberal values. The final chapter of this book shows that the trends in values in Egypt, Tunisia, and Turkey indicate a significant decline in religious intolerance and an increase in support for secular politics and, to a limited degree, for gender equality.

Correlates of Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values: Opposing Relationships

To more fully understand the relationship between religious fundamentalism and liberal values, one must consider that these two diverse value orientations are subject to the opposing effects of the same set of social forces on individuals. It is argued that the factors that reinforce religious fundamentalist orientations among individuals tend to weaken their support for liberal values, and vice versa. To assess this hypothesis, the linkages of such factors as demographics (SES [socioeconomic status], gender [male =1, female=0], youth bulge, and area of residence), religion (religiosity, religious modernity, confidence in religious institutions), mixing of the sexes, pre-marital sex, and morality (mixing of the sexes corrupts, and premarital sex immoral), attitudes toward outgroups (ethnic sectarianism, conspiracy, and xenophobia), sources of information (internet use), and fate versus free will (fatalism) are evaluated,

First, with demographics, the focus is on social class, gender, the youth bulge, and urban-rural residence and their relationships with religious fundamentalism and liberal values. Here it is argued that more education and higher income are likely to weaken religious fundamentalism and strengthen liberal values. Education is said to lower cognitive barriers to enlightenment, and as a result, the educated are more skilled in analyzing issues, assessing alternative perspectives, and making sense of the world autonomously than are those who are less educated (Schussman and Soule 2005; Krueger and Malečková 2003). They are thus less likely to espouse a literalist, exclusivist, and intolerant view of religion, compared to those with lower levels of education. Also, individuals with higher incomes are less likely to harbor fundamentalist beliefs because they have greater access to more diverse cultural perspectives and networks. Lower-income individuals, on the other hand, are more likely to support religious fundamentalism. They experience a higher level of status insecurity (Weber 1964; Caudill 1963; Weller 1965; Shapiro 1978; Coreno 2002), and they are more likely to support the communitarianism of religious fundamentalism (Davis and Robinson 2006). People living in rural areas, with limited access to a more diversified religious environment, may display stronger religious fundamentalism than those in urban areas. Finally, the possible effects of gender and age on religious fundamentalism and liberal values are assessed.

Second, it is evident that without religion, religious fundamentalism may not exist. Higher religiosity may thus be linked to stronger religious fundamentalism. Moreover, people with greater confidence in religious institutions are more likely to self-restrict to such institutions for information and guidance, to develop a stronger monolithic view of religion, and thus to become more strongly fundamentalist. Finally, individuals who more strongly support the idea that religious beliefs foster development—espousing religious modernity—may develop a stronger attitude against secular change, a more holistic view of religion, and a stronger fundamentalist orientation. Being secular, the adherent of liberal values, on the other hand, exhibits weaker religiosity, lower confidence in religious institutions, and a less favorable attitude toward religious modernity.

Third, fundamentalists’ attitudes toward sex and morality include censure of premarital sex and admonition against the mixing of the sexes in public places (Motahhari 1969; Taraki 1996). The linkages of people’s conceptions of the immorality of premarital sex and their attitudes toward the mixing of the sexes with religious fundamentalism and liberal values are assessed.

Fourth is the factor of in-group solidarity and out-group hostility. Social science research has shown that hostility toward outsiders, or xenophobia, and the belief in conspiracies are linked to right-wing solidarity and religious fundamentalism (Pipes 1996; Euben 1999; Zeidan 2001; Maehr and Karabenick 2005; Inglehart, Moaddel, and Tessler 2006; Choueiri 2010; Bermanis et al. 2010; Koopmans 2014).

The fifth factor is that of fatalism. The belief that one must obey a disciplinarian God and surrender unconditionally to his will may be stronger among fatalistic individuals, who consider that their fate has been firmly established and there is little one can do to change it (Ford 1962; Quinney 1964; Booth 1991; Mercier 1995; Ellerbe 1995; Cohen-Mor 2001; Brink and Mencher 2014).

Finally, the use of the internet as a source of information among ordinary individuals may be linked to religious fundamentalism and liberal values in different ways. The internet enhances individuals’ access to more diverse sources of information and a variety of perspectives on religion. Such sources of information enable individuals to develop a general awareness of a plurality of belief systems and alternative venues for spiritual satisfaction, and as a result, they tend to develop a weaker fundamentalist orientation and stronger adherence to liberal values.

Measurement of the Predictors of Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values

Demographics: Socioeconomic status was measured in terms of education and income. Education was coded in nine categories, ranging from 1 for no formal education to 9 for a university-level education with degree. Household income before taxes, counting all wages, salaries, pensions, and other income, was coded in approximate deciles by the local investigators in each country, with 1 as the lowest decile and 10 as the highest. Because education and household income were significantly correlated across the seven countries, a single index of socioeconomic status was constructed by averaging the two measures. Rural was a dummy variable, where areas with populations of 10,000 were coded 1 and areas with populations of more than 10,000 were coded 0. Gender and youth bulge were also dummy variables, where male was coded 1 and female was coded 0 and where youth bulge was coded 1 and otherwise 0.

Religion: A religiosity index was constructed by averaging three variables (coding on all three are reversed so that higher values indicate greater religiosity): (a) frequency of prayer—ranging from 1, never, to 6, five times daily; (b) self-description as religious—ranging from 1, not at all religious, to 10, very religious; and (c) the importance of God in life, ranging from 1, not at all important, to 10, very important. Confidence in religious institutions was measured by one survey question: “Please tell me whether you have (1) a great deal of confidence in religious institutions, (2) quite a lot of confidence, (3) not very much confidence, or (4) none at all.” A religious modernity index was constructed by averaging the responses to three questions about the belief that religion fosters development (the coding for these variables are reversed for the higher values to indicate more developed): “Would it make your country (1) a lot more developed, (2) more developed, (3) less developed, and (4) a lot less developed, if (a) faith in Allah increases, (b) the influence of religion on politics increases, and (c) belief in the truth of the Quran [Bible (for Christian respondents)] increases?”

Attitudes toward sex and morality: One question asked respondents to rank the morality of premarital sex on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being moral and 10 being immoral. Another question dealt with the mixing of the sexes in public places: “How often does allowing men and women to work together in public places lead to moral decay: (1) always, (2) most of the time, (3) occasionally, or (4) never?” The coding for both variables are reversed.

In-group solidarity and out-group hostility: The belief in conspiracy was measured by whether respondents “(1) strongly agree, (2) agree, (3) disagree, or (4) strongly disagree that there are conspiracies against Muslims [Christians (for Christian respondents)].” This variable is recoded from the original so that a higher value indicates a stronger belief in conspiracy. An index of xenophobia was made by averaging the responses to a series of questions on whether respondents would like to have various groups as neighbors, including French, British, Americans, Iranians [for Pakistanis in Iran], Kuwaitis [for Iraq]/Indians [for Pakistan]/Iraqis [for all other countries], Turkish [for Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Iran]/Saudis [for all other countries], and Jordanians [for Iraq]/Saudis [for Iran]/Afghanis [for Pakistan]/Pakistanis [for Saudi Arabia]/Syrians [for all other countries]. The responses were recoded as 2 for those who would not like to have them as neighbors and 1 for those who would like to have them as neighbors. Finally, sectarianism was measured in terms of intra- and intergroup trust differentials. Respondents were asked how much trust they have in the members of their own and other groups: (1) a great deal, (2) some, (3) not very much, or (4) none at all. Coding for this variable is reversed so that a higher value indicates a greater trust. It was calculated using this formula:

Ethnic sectarianism as trust differential for individual i in ethnicity e1 = Trust in his/her ethnicity1 − Mean (trust in ethnicity2 + enthnicity3 + …+ ethnicityn)

Internet use: Internet use was measured by the extent to which respondents relied on it as a source of information: (1) a great deal, (2) some, (3) not very much, and (4) not at all. Coding for this variable is reversed so that a greater value indicates more reliance on the internet as the sources of information.

Fatalism: Respondents were asked to choose a number between 1 and 10, where 1 = “everything in life is determined by fate” and 10 = “people shape their fate themselves.” Coding on this variable is reversed so that a greater number indicates stronger fatalism.

Findings: Correlates of Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values

Table 4.11 shows the correlation coefficients of the measures of demographics, religion, attitudes toward sex and morality, in-group solidarity and out-group hostility, internet use, and fatalism with the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values. There is a consistent pattern of opposing relationships between these predictors and the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values across the countries, except for gender and some minor deviations for some of the other measures. A higher socioeconomic status is negatively linked to religious fundamentalism and positively linked to liberal values across all the seven countries, except among Saudi respondents, where these relationships were not statistically significant. Those in the youth bulge were also less fundamentalist and more liberal, except in Egypt, where these relationships were not significant. Finally, respondents residing in rural areas, or smaller towns in the case of Saudi Arabia, were more strongly fundamentalist and less supportive of liberal values across the countries, except that rural residence had no significant relationship with religious fundamentalism among Iraqis and no significant relationship with either index among Tunisians. All religion-related variables—religiosity, religious modernity, and trust in religious institutions—are positively linked to fundamentalism and negatively linked to liberal values. The same was true concerning the mixing of the sexes and premarital sex, except that attitudes toward the mixing of the sexes had no significant link with religious fundamentalism among Saudis and Egyptians. All the variables related to in-group solidarity and out-group hostility were linked positively to religious fundamentalism and negatively to liberal values, except that liberal values and conspiracy among Iraqis and liberal values and xenophobia among Tunisians were not significantly linked. Internet use was consistently negatively linked to religious fundamentalism and positively linked to liberal values, but the opposite was the case with fatalism, except that Saudi fundamentalists were less fatalistic.

TABLE 4.11 Correlation Coefficients for Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values at the Micro (Individual) Level

These findings thus support the hypothesis that the sociological factors that support religious fundamentalism weaken liberal values, and vice versa. Chapter 5 will show that the same is true on the macro (country) level; that is, pertinent features of the macro (country) context that strengthen aggregate religious fundamentalism on the national level weaken liberal values, and vice versa.

Summary

This chapter offered a distinctly religious definition of religious fundamentalism, without that definition resting on the specific beliefs of any religion. It conceptualized fundamentalism as a religious orientation or a set of beliefs about and attitudes toward whatever religious beliefs one has. It considered religious fundamentalism as a multidimensional construct, having four components: a disciplinarian conception of the deity, literalism, religious exclusivity, and religious intolerance. Four sets of survey items measured these components, and the average of these four components or sixteen items produced a religious fundamentalism index. The analysis showed that there is considerable variation in fundamentalism across the seven countries. However, the majority of the respondents from the seven countries tended to have fundamentalist orientations. Among the four components of religious fundamentalism, however, the religious intolerance component was much weaker than the other three—a disciplinarian deity, literalism, and religious exclusivity.

The findings also indicated that members of the youth bulge were less fundamentalist than the older age group, except among Egyptians. There were no gender differences in fundamentalism except among Lebanese, Saudi, and Tunisian respondents, where women were more fundamentalist than men. Also people with university education had significantly weaker fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes than did people without university education across all the countries, except Saudi Arabia, where there was no significant difference between the two educational groups. In terms of age and education, university education made a significant difference in religious fundamentalism among Egyptian, Lebanese, Pakistani, Tunisian, and Turkish respondents across both age groups and among Iraqis in the older age group and no difference among Saudi respondents across both age groups.

In terms of religions and religious sects, the pooled data showed that Christians were less fundamentalist than Shia or Sunni Muslims and that Shias were less fundamentalist than Sunnis. This finding was also true at the national context, with one exception concerning the Saudi Shias. Shias were consistently and significantly less fundamentalist than Sunnis across the samples from Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey; Christians in Egypt and Lebanon were less fundamentalist than their Muslim counterparts; and Lebanese Christians were significantly less fundamentalist than Egyptian Christians. The exception was that Saudi Shias scored the lowest on the religious fundamentalism index across religions and religious sects. The difference in religious fundamentalism between Saudi Shias and Lebanese Christians, however, is not statistically significant.

The analysis showed that religious fundamentalism and its four components were negatively correlated with three components of liberal values—expressive individualism, gender equality, and secular politics—across all seven countries. A comparative analysis of the respondents’ orientations showed that the percentages of these respondents who favored religious fundamentalism were much higher than the percentages of those who favored liberal values across the seven countries, except among Lebanese, where support for the two opposing movements was about the same.

This analysis indicated the relative stand of the respondents on religious fundamentalism vis-à-vis liberal values, but to better understand how values might change toward liberalism, a more effective comparison was needed—that between support for religious intolerance and a measure of liberal values that was based on the average of the indices of gender equality and secular politics. The rationale was that the decline in religious fundamentalism is more likely to start with a decrease in support for religious intolerance and the shift toward liberal values is more likely to start with an increase in support for secular politics and gender equality. Adhering to this stipulation, these measures were recalculated, and variation in religious intolerance and liberal values (as the average of the indices of secular politics and gender equality) was assessed across the seven countries. The results showed that in Lebanon, Tunisia, and Turkey, there was significantly more support for liberal values than there was for religious intolerance. In the other four countries, those who favored liberal values varied between 7 percent among Saudis and 27 percent among Iraqis, while those who were religiously intolerant varied between 78 percent among Saudis and 51 percent among Iraqis.

Finally, this chapter showed that the individual attitudes and attributes that were positively linked to religious fundamentalism were negatively connected to liberal values, and vice versa. Religious fundamentalism was weaker and liberal values stronger among individuals who (1) had a higher socioeconomic status, (2) were younger, (3) lived in urban areas, (4) were less religious, (5) had weaker trust in religious institutions, (6) believed less strongly in religious modernity, (7) gave lower ratings to the immorality of premarital sex, (8) disagreed more strongly that the mixing of the sexes in the workplace would cause corruption, (9) believed less strongly in conspiracy theory, (10) were less xenophobic, (11) had weaker sectarian solidarity, (12) were less fatalistic, and (13) relied more strongly on the internet as the source of information.