I have argued in the preceding chapters that the ideological warfare for the cultural control of society in the Middle East and North Africa has been persistently focused on a set of historically significant issues. These issues, which have remained remarkably invariant in the contemporary period, are the autonomy of the individual, social status of women, role and function of religion in society, relationship between religion and politics, form of government, basis of the identity of one’s community, and nature of the outside world (other countries or religions). Under the current conditions, only two dominant and opposing ideological movements are competing to resolve these issues in the region. One is supported by the enthusiasts of religious fundamentalism and the other by the advocates of liberal values. In each of the seven countries, orientations toward fundamentalism and liberal values were shown to be inversely linked. Individuals who were more strongly fundamentalist were less liberal.

As discussed in chapter 4, variation in religious fundamentalism and liberal values among individuals was linked to variation in the social attributes, attitudes, and perceptions of these individuals, and the individual characteristics that were positively associated with fundamentalism were negatively connected to liberal values. This chapter shows that these relationships are also true on the macro (country) level; that is, cross-national variation in aggregate Islamic fundamentalism is inversely related to variation in aggregate support for liberal values, variation in both Islamic fundamentalism and liberal values is connected to differences in the characteristics of the national contexts of the seven countries, and the characteristics of the national context that strengthen fundamentalism weaken liberal values. To demonstrate these relationships, this chapter first draws on the extant scholarly literature on the relationship between the national context and human values. Then it specifies and measures the pertinent characteristics of the national context. Finally, it proposes and empirically assesses several hypotheses on the relationships of these characteristics with Islamic fundamentalism and liberal values.

Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values on the Country Level

The indices of religious fundamentalism and the components of liberal values were discussed in chapters 1 through 4 and were shown to vary considerably across the seven countries. The aggregate values of these variables for each of the seven countries are reproduced in table 5.1.

TABLE 5.1 Means of Indices of Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values and its Components

As shown in table 5.1, the values of the index of religious fundamentalism are significantly higher than those of the index of liberal values across the seven countries, indicating that the respondents expressed stronger support for religious fundamentalism than for liberal values. The magnitudes of the differences between the two indices, however, vary cross-nationally: 3.42 for fundamentalism versus 1.93 for liberal values for Pakistan, 3.44 versus 2.04 for Egypt, 3.33 versus 2.08 for Saudi Arabia, 3.28 versus 2.21 for Iraq, 3.18 versus 2.52 for Tunisia, 2.98 versus 2.68 for Turkey, and 2.80 versus 2.74 for Lebanon. The differences between religious fundamentalism and liberal values are much smaller for Lebanon (0.06), Turkey (0.30), and Tunisia (0.66) than for Iraq (1.07), Saudi Arabia (1.25), Egypt (1.40), and Pakistan (1.49).

The correlation coefficients for the aggregate religious fundamentalism index and the aggregate indices of expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values at the macro (country) level are significant and negative, as shown in table 5.2. The religious fundamentalism index is negatively linked to the indices of expressive individualism (r = −.89), gender equality (r = −.87), secular politics (r = −.82), and liberal values (r = −.95). These inverse relationships on the aggregate level indicate that, where religious fundamentalism is stronger, there is weaker support for liberal values. Evidently, as these and the findings reported in chapter 4 indicate, in the same way that individuals with stronger fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes tend to express weaker support for liberal values, countries that on average scored higher on religious fundamentalism also scored lower on liberal values.

TABLE 5.2 Correlation Coefficients for Indices of Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values and its Components

Explaining Macro Variation

Chapter 4 showed that the micro (individual) variations in religious fundamentalism and liberal values had opposing relationships with demographics (socioeconomic status, age, and urban-rural residence), religion (religiosity, confidence in religious institutions, and religious modernity), in-group solidarity and out-group hostility (sectarianism, conspiracy, and xenophobia), internet use, and fatalism. The previous chapters also showed that religious fundamentalism and liberal values varied on the macro (country) level and that the countries with younger populations scored higher on the aggregate religious fundamentalism index and lower on the aggregate liberal values index. This chapter further assesses the significance of the factors that are linked to macro- or country-level variation in people’s fundamentalist and liberal orientations, in an effort to explain the variation in both indices in terms of such variable features of the national context as the structure of the religious environment, state structures and interventions, economic development, globalization, and the situation of women. Finally, it is argued that, similar to the micro factors, these macro factors have opposing relationships with aggregate religious fundamentalism and aggregate liberal values; that is, cross-nationally, the factors that strengthen religious fundamentalism weaken liberal values, and vice versa.

Structure of the Religious Environment

The structure of religious environment—whether it is monolithic or pluralistic and whether it supports religious authoritarianism or religious liberty—shapes conditions in ways that are more favorable either to the rise of Islamic fundamentalism or, alternatively, to that of religious modernism and liberal values. A pluralistic context that includes both secular and religious options for seekers of spirituality weakens religious fundamentalism but strengthens religious modernism and liberal values. Such a context is likely to offer a richer menu of options to satisfy a wider range of spiritual needs than a monolithic context (Montgomery 2003). As a result, fewer “spiritual shoppers” (Wuthnow 2005) would be willing to develop a monolithic view of religion and adopt religious fundamentalism. Furthermore, a pluralistic context exposes the public to a greater number of perspectives on life, security, and happiness, reinforcing views concerning the varied ways that metaphysical entities, supernatural beings, or gods may be worshipped (Berger and Luckman 1969). People are thus less likely to follow a disciplinarian deity, accept a literal reading of the scriptures, and adopt an exclusivist and intolerant view of religion and are more likely to support religious modernism and liberal values. Religious monopolies, on the other hand, contribute to religious fundamentalism through mobilizing resources, sanctioning religious behavior, punishing religious nonobservance, and exploiting sectarian rivalries (Handy 1991; Breault 1989; Blau, Land, and Redding 1992; Blau, Redding, and Land 1993; Ellison and Sherkat 1995). In certain contexts, like postrevolutionary Iran, religious monopolies may prompt the rise of liberal oppositional discourse.

The contrast between the historical conditions that promoted the rise of Islamic modernism and those that promoted the rise of religious fundamentalism supports this proposition—namely, Islamic modernism emerged under a condition of religious pluralism, while religious fundamentalism emerged under a monolithic cultural-cum-religious condition. Modernism and fundamentalism constituted two opposing responses to the intellectual problems Islam faced in the modern period. Muslim intellectual leaders produced a modernist discourse in Islam—most notably, in Egypt and India—in the second half of the nineteenth century because they encountered a plurality of discourses advanced by the followers of the Enlightenment, Westernizers, think tanks connected to the colonial administrations, missionaries, and the ulama (Muslim theologians). All these groups were competing for intellectual control of the society, while state intervention in culture was limited. Encountering a multitude of diverse challenges to their faith, these intellectuals tried to formulate a moderate transcendental discourse that bridged Islam with the ideology of the Enlightenment. Their twentieth-century counterparts turned fundamentalist in Algeria, Egypt, Iran, and Syria because they chiefly faced a monolithic discourse imposed from above by the authoritarian secular ideological state (Moaddel 2005).

An important mechanism that may explain the development of Islamic modernism is the presence of a discursive space in the Islamic orthodoxy that enabled Muslim reformers to recognize and pinpoint the location of the problematic elements in Islamic religious and political perspectives. These problematic elements in the Islamic orthodoxy consisted of (1) the constraint placed on reason (the closing of the gate of independent reasoning) and (2) the recognition of the sultan’s discretionary power. The modernists had to reject both elements in order to be able to bring Islam closer to the sociopolitical perspective of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and advance their rationalist exegesis of the scriptures. The rise of Islamic fundamentalism, on the other hand, was a result of the narrowing of the discursive space in the Islamic system of thought. The secular authoritarian state was thought to be the problematic element that had to be overthrown. Such a political context favored those Muslim activists who were advancing the notion of a religious despot—the faqih or caliph in Shia or Sunni fundamentalism, respectively—to combat the secular state and unconditionally execute God’s instructions on Earth. These activists found that Islam was a perfect system of universal truth and glossed over the religion’s theoretical inadequacies underpinning the remarkable failures of the caliphates in historical Islam to establish a transparent and effective system of rules. This chapter thus proposes that, across the seven countries, higher levels of support for liberal values or a lower level of support for religious fundamentalism is connected to higher levels of religious pluralism and religious freedom or weaker levels of religious monopolies.

State Structures and Interventions

The premise that state structures shape religious outcomes has a long pedigree in the sociology of religion. For example, Swanson (1967) links the success of Protestantism in sixteenth-century Europe to variations in the structures of political sovereignty, relating the varying conceptions of immanence in Protestantism and Catholicism to the manner in which political sovereignty was experienced in various parts of Europe. Wuthnow (1985), as an alternative, relates the victory of the Reformation movement in England and its failure in France in the sixteenth century to the British state’s autonomy from the country’s landed aristocracy and the French state’s lack of such autonomy in this period.

Consistent with these arguments, this chapter relates variable features of the state to variations in people’s orientations toward religious fundamentalism and liberal values. The pertinent features specified in this chapter, however, are different from those mentioned by Swanson (1967) and Wuthnow (1985). Two features are proposed here for a better understanding of the relationships between regimes and religious fundamentalism, on the one hand, and liberal values, on the other. One is the state’s intervention in religious affairs, the extent to which it attempts to regulate religious institutions and their activities. Religious fundamentalism may arise as a reaction to such interventions. This may occur in several ways. First, by launching cultural programs to promote secular institutions, fostering national identity as a substitute for religious identity, and instituting laws that run contrary to religious beliefs, the secular authoritarian state may contribute to the perception among the faithful that their religion is under siege, their core values are offended, and their religious liberty is obstructed. This perception of besieged spirituality may activate religious awareness that prompts individuals to grow “hypersensitive even to the slightest hint of theological corruption within their own ranks” (Smith 1998, 8), use religious categories to frame issues, and adopt alarmist attitudes and conspiratorial perspectives (Moaddel and Karabenick 2013). At the same time, the authoritarian nature of the secular state may weaken liberal values as its policies of disorganizing and disrupting collectivities in civil society may channel oppositional politics through the medium of religion (Stepan 1985; Moaddel 1993). Finally, a religious authoritarian state by courting religious activists and groups in order to fend off challenges from secular and liberal currents may inadvertently contribute to the resources and societal influences of religious fundamentalist movements.

The other pertinent feature is the structure of the authoritarian state. It is argued here that the structure of power relations within the state is consequential for the formation of oppositional politics. Insofar as this power structure is unified, pluralism would decline and fundamentalism would be strengthened. Under a unified elite, an authoritarian state would be more effective in imposing a monolithic religion or culture on the subject population. Therefore, a limited number of secular or alternative religious options would be available for the seekers of spirituality. An authoritarian state that is controlled by a fragmented elite, on the other hand, tends to experience inter-elite rivalries and acrimonious debates. Such internal disputes would not only diminish the state’s ability to impose religious uniformity on society but also generate a political–cum–discursive space that permits the growth of alternative religious and/or secular liberal groups (Moaddel and Karabenick 2013).

An authoritarian state with a unified structure would strengthen fundamentalism, while a fragmented authoritarian state would tend to strengthen liberalism. The Islamic Republic of Iran and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia provide contrasting examples. While both regimes are remarkably similar in religious sectarianism, repressiveness, and rentierism (i.e., oil is the major source of revenue), the ruling elite is fragmented in Iran but unified in Saudi Arabia. The rise of liberalism and religious reformism in postrevolutionary Iran (Rajaee 2007; Kamrava 2008; Moaddel 2009) and fundamentalism in Saudi Arabia (Dekmejian 1994; Okruhlik 2002; Moaddel 2006, Moaddel 2016) appears to correspond to the difference in the structure of power relations between the two repressive religious regimes.

Economic Development

The modernization theory relates cross-national variation in values to the level of economic development (Rostow 1960; Deutsch 1961; Parsons 1964; Levy 1966; Apter 1965; Huntington 1968). It is, however, hard to establish a determinate relationship between a specific type of economic development (e.g., the development of capitalism) and changes in values in a particular direction (e.g., the rise of liberal democracy). Inglehart has tried to further elaborate the relationship between economic development and changes in values by suggesting specific links or mechanisms that mediate this relationship. He posits, first, that economic development brings about economic prosperity and the latter in turn satisfies the needs for physical survival, enhancing the feeling of security. The enhanced feeling of security in turn contributes to the subjective context necessary for a shift from materialist values to self-expressive and esthetic values. Second, this shift occurs primarily among those who are in their impressionable years (those under age 25). Therefore, as the younger generations grow older, a major shift toward postmaterialism occurs in the overall societal value structure (Inglehart 1971; Inglehart and Welzel 2005).

A fuller assessment of the modernization theory requires longitudinal data. Here, nonetheless, cross-national data are used in order to assess whether variation in the level of economic development across the seven countries is linked to variation in the aggregate indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values.

Globalization

Two diverse hypotheses may be advanced to test the relationship between globalization and cultural change in the direction of religious fundamentalism or liberal values in the Middle East and North Africa. The first relates globalization to diversification of culture, which weakens religious fundamentalism and strengthens liberal values. Accordingly, the development of digital communication technology and the expansion of the means of mass transportation reduce the constraints of geography on social interactions (Waters 1995), intensifying “worldwide social relations” (Giddens 1990, 64) and widening intercontinental networks of economic, political, and cultural interdependence among nations (Keohane and Nye 2000; Frankel 2000; Sassen 2001). These developments help globalize economic activities and enhance diffusion and absorption of cultures. Globalization in turn facilitates access to diverse information sources, undermines cultural control by the ruling elite, weakens religious monopolies, and thus narrows the social basis of religious fundamentalism and strengthens liberal values.

The alternative hypothesis posits that globalization, by reducing the constraints of geography and enhancing intercultural contact, intensifies the clash of civilizations (Huntington 1996a). At the same time, globalization heightens efforts to eliminate barriers to the expansion of the world markets, to facilitate the employment of similar organizational structures (Stohl 2005), and to enforce a homogeneous cultural pattern popularly known as the McDonaldization of society (Ritzer 1993). Such policies in turn tend to cause the breakdown of the protective shields of small traditional communities, generating feelings of alienation and insecurity (Giddens 1991; Kinnvall 2004). Finally, globalization is said to expand inequality through the peripheralization of less developed countries as a result of the incorporation of their indigenous economies into the global capitalist system with its hierarchy of asymmetrical exchange relations (Wallerstein 2000). The increased economic inequality intensifies social tensions and class conflict, generating a basis for the rise of alternative cultural movements to resist worldwide capitalist expansion. Reflecting this process is the increase in support for Islamic fundamentalism and the concomitant weakening of support for liberal values.

Finally, an important feature of the pertinent social conditions that may shape fundamentalism and liberal values is related to the situation of women in society. This section proposes that the strength of religious fundamentalism is inversely linked to female empowerment. In a national context where women are free to pursue their interests in various domains of social life, liberal values are stronger and fundamentalist attitudes weaker. A crucial factor that may have a strong effect on women’s empowerment is their labor force participation. Female employment outside the home is associated with, but not necessarily reducible to, the level of economic development. Through labor force participation, women earn an income and thus gain financial autonomy, contributing to their overall ability to articulate interests. This ability enables them to overcome more effectively the limitations that are imposed on them by patriarchal institutions. Furthermore, increased female participation in the labor force entails more frequent interaction with men, which may lead to the formation of a more flexible outlook on gender equality. Thus, it is proposed that liberal values are stronger and support for religious fundamentalism weaker in countries where a larger proportion of women participate in the labor force outside the home.

It has also been suggested that sex ratio (the number of males per one hundred females in a society) is another macro structural factor that shapes gender relations and attitudes toward gender equality. According to Guttentag and Secord (1983), imbalanced sex ratios have consequences for gender relations: when men are in short supply, more opportunities are available to them to form dyadic relationships with women, resulting in men having more power over women. The social consequence of this imbalance may cause men to be promiscuous, weakly committed to monogamy, and less dependable as partners. At the same time, the traditional gender role for women is less valued; women have greater freedom to engage in nontraditional types of activities and have fewer restrictions imposed on their movements, so they are able to travel and to dress in public as they wish. Where women are in short supply, on the other hand, they have dyadic power over men. Yet in this case, their ability to use this power is constrained by the fact that men have structural power through control of “the political, economic and legal structures of the society” (Guttentag and Secord 1983, 26; see also South and Trent 1988). Men use their structural power to shape the social norms and practices in their favor, thereby effectively blocking women from using their dyadic power to promote their interests. In this situation, although women are valued greatly and protected, their traditional gender role is strengthened to the point where extrafamilial social functions become quite limited. Because women are in short supply, as the theory implies, they are expected to stay away from the gaze of other men. Forcing women to stay home, imposing gender segregation at work and other social gatherings, and implementing conservative public dress codes for women thus serve to discourage such male behavior.

Therefore, the higher the sex ratio in a country, the stronger the support for religious fundamentalism and the weaker the support for liberal values.

Measurement

To summarize, on the macro (country) level, religious fundamentalism and liberal values are shaped by the structure of the religious environment, state structures and interventions, economic development, globalization, and the situation of women. These constructs are measured in order to assess the strength of their relationships with the aggregate indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values across the seven countries.

Structure of the Religious Environment

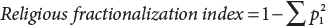

Two indicators are used to measure whether the structure of the religious environment is pluralistic or monolithic. One is a religious liberty index. It is constructed as the average of the indices of religious freedom (varies between 1 = high and 7 = low) and religious persecution (varies between 1 = religious freedom and no religious persecution and 10 = no religious freedom and high levels of religious persecution), which are reported by the Association of Religious Data Archives. The religious freedom index has been recoded so that higher values indicate greater religious freedom and less religious persecution.1 The other indicator is a measure of religious fractionalization constructed from the sample data reported in table 5.3. This measure uses the religious fractionalization formula:

TABLE 5.3 Respondents’ Religious Affiliations

In this formula, pi is the proportion of a religion or religious sect i (i = 1, 2, 3 …, n) in the sample (see table 5.3). Using the data in table 5.3, the religious fractionalization index for Saudi Arabia is equal to 1 − (0.922 + 0.082) = 0.15. A higher value indicates a higher level of religious diversity.2

State Structures and Interventions

Three features of the state are measured. The first is the authoritarian structure of the state, which is measured by political exclusion. It indicates the degree of openness of the political system and political freedom by averaging the extent of political rights and civil liberties in a country, ranging from 1 (free) to 7 (unfree).3 Political exclusion is measured in 2010 for Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia—with a one-year lag of the dependent variable or the data collection in these countries in 2011—and in 2012 for Tunisian and Turkey—again with a one-year lag of data collection in these countries in 2013. GRRI was available for 2003 and ranges between 0 (no regulation) and 10 (high regulation). The second is state intervention in religious affairs. This construct is measured by the Government Regulation of Religion Index (GRRI), which is reported by the Association of Religion Data Archives.4

The third is the degree of fragmentation of the state’s power structures. It is measured by a fragmentation ratio, which is the square root of a measure of the fractionalized elite5 divided by the political and civil liberties index.6

Economic Development and Situation of Women

Economic development is measured as GDP per capita. The situation of women involves two factors. The first, female labor force participation, is measured as the number of females in the labor force divided by the female population aged 15 and older, indicated as a percentage. Second, sex ratio is measured as the percentage of the population that is male.

Globalization

Two measures of globalization are used. One is economic globalization,7 which is a linear combination of two standardized indicators: (1) international trade, the sum of imports and exports as a percentage of GDP, and (2) foreign capital penetration (FCP), which is measured as

Foreign direct investment is the net inflow of investment to acquire a lasting management interest (10 percent or more of voting stock) in an enterprise operating in an economy other than that of the investor. It is the sum of equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, and other long-term and short-term capital as shown in the balance of payments. The other measure, which may be called cultural globalization, measures internet penetration by determining the percentage of the population that has access to the internet.

To make the two measures more stable, three-year averages of the data on trade, foreign capital penetration, and internet access were calculated where such data were available for 2009–2011 and 2010–2012, depending on whether data collection for the country was completed in 2011 or 2013, respectively.

Hypotheses

Based on the analytical framework and these measures, support for religious fundamentalism would be stronger and support for liberal values weaker in countries characterized by

1. Weaker religious liberty and lower fractionalization;

2. Lower state fragmentation ratio, higher political exclusion, and higher government regulation of religion;

3. Lower level of economic development;

4. Weaker economic and cultural globalization; and

5. Lower female labor force participation and higher sex ratio.

Table 5.4 reports measures of the five categories of variables used in the analysis: religious environment (religious liberty and religious fractionalization), state structures and interventions (political exclusion, fractionalization ratio, and government regulation of religion), economic development (GDP per capita), globalization (economic globalization and cultural globalization or internet penetration), and situation of women (female labor force participation and sex ratio) for the seven countries. The religious environment varies across the seven countries. Lebanon scored highest on religious liberty (7), followed by Turkey (6), Tunisia (5.5), and Saudi Arabia (4.5), Egypt and Pakistan (4 each), and Iraq (1.5). Lebanon is the most fractionalized country (0.76 where the maximum is 1), followed by Iraq (0.50), Turkey (0.20), Pakistan (0.18), Saudi Arabia (0.15), Egypt (0.08), and Tunisia (0.02). Measures of state structures and interventions also vary considerably; political exclusion varies between 3.0 (Turkey) and 6.5 (Saudi Arabia), the fragmentation ratio between 0.21 (Saudi Arabia) and 0.47 (Turkey), and government regulation of religion between 4.9 (Lebanon) and 9.8 (Saudi Arabia).

TABLE 5.4 Characteristics of National Context

GDP per capita is highest in Saudi Arabia (44,502) mostly due to its rentier economy, and lowest in Pakistan (4,197). The standardized measure8 of economic globalization fluctuates between −2.37 for Pakistan and 2.67 for Lebanon, and cultural globalization or internet use varies between 42.17 for Saudi Arabia and 2.87 for Iraq. Female labor force participation is highest in Turkey (29 percent) and lowest in Saudi Arabia (14 percent). Finally, the sex ratio is lowest for Lebanon (0.96), indicating that there are more females in the country than males, and highest for Saudi Arabia (1.18). A sex ratio of 1.18 is quite high, indicating that there are many more men in Saudi society than there are women.

Relationship of the National Context to Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values

The correlation coefficients measuring the strength of the association of the ten indicators for the five different features of the national context with the indices of religious fundamentalism and liberal values are reported in table 5.5. Most of these coefficients are statistically significant and in the expected directions. That is, the features of the national context that have negative effects on religious fundamentalism are positively linked to the indices of liberal values and its components, and those features that have positive effects on religious fundamentalism are negatively linked to the indices of liberal values and its components. However, there are some notable exceptions to the significance of these linkages.

TABLE 5.5 Correlation Coefficients for Indices of Religious Fundamentalism and Liberal Values and Macro- or Country-level Variables

Structure of the Religious Environment

Two indicators measure the structure of the religious environment. One is the religious liberty index, and the other is religious fractionalization index. Religious liberty is significantly inversely linked to religious fundamentalism (r = −.72). That is, the higher the level of religious liberty in a country, the weaker the support for religious fundamentalism. Religious liberty thus weakens the concept of an authoritarian deity, literalism, exclusivity, and intolerance. Religious liberty, on the other hand, is directly connected to the indices of expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values (r = .75, .69, .49, and .71, respectively), although its link to secular politics is not statistically significant. These relationships thus indicate that the stronger the conditions of religious liberty (meaning higher levels of religious freedom and fewer cases of religious persecution), the stronger people’s attitudes in support of expressive individualism and gender equality.

The religious fractionalization index, measuring the extent to which a country’s religious profile is segmented and divided into different religions and religious sects, tends to weaken religious fundamentalism (r = −.64) but has no significant effect on liberal values (although these relationships are in the expected direction).

State Structures and Interventions

The three measures of state structures and interventions reflect different attributes of the state. The first two indicators, the state’s political exclusion and regulation of religion, are positively linked to religious fundamentalism (r = .63 and .82, respectively). These linkages are thus consistent with the hypotheses that an exclusivist state tends to channel oppositional politics through religion and that government interventions in religious affairs politicize religion, contributing to the rise of religious fundamentalism. Political exclusion, as expected, is inversely linked to the indices of gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values. The correlation coefficients between political exclusion and these indices are significant and negative (r = −.92, −.76, and −.74, respectively). Government regulation of religion is negatively correlated with all the four indices of expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values (r = −.55, −.85, −.97, and −.88, respectively). Judged by the size of the correlation coefficients, it appears that government regulation of religion, which is apparently specifically targets religion, is generally a better predictor of religious fundamentalism and liberal values than is political exclusion, which is a more general state attribute.

Finally, the third indicator, the fragmentation ratio measures the authoritarian state’s ability to regulate and control the civil society. A high value for the fragmentation ratio means that, while the authoritarian state has the resources—the technology, finances, and manpower—to repress the opposition within the civil society (that is, it has the capacity), it may not have the ability to actually repress the opposition. It faces difficulties in identifying, locating, and repressing members of the opposition. These difficulties are the result of the opposition having a diffused presence. Opposition is a matter of degree, ranging from individuals who support the state somewhat to those who are totally against it. In other words, politically active individuals or currents in civil society partly oppose the state and partly support it. In fact, the fragmentation of the state structure corresponds to and encourages gradations of support and opposition within the society. The outcome is a diminished repressive capability of the state.

The findings support this proposition. The fragmentation ratio, as a measure of the state’s fragmented power structure, is negatively linked to the index of religious fundamentalism (r = −.67). Therefore, it weakens fundamentalist beliefs and attitudes. It is, on the other hand, positively linked to the indices of gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values (r = .93, .71, and .72, respectively). It therefore constitutes a favorable political context where attitudes toward gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values are strengthened. The ratio, however, has no significant relationship with the index of expressive individualism. Judging by the size of its correlation coefficients with the indices of fundamentalism and liberal values, the fragmentation ratio has a stronger effect in promoting liberal values than in weakening fundamentalism.

In sum, the fragmentation of the state power structure provides a political context favorable to liberal values and unfavorable to religious fundamentalism, while political exclusion and government regulation of religion generate a context that has the opposite effects, weakening liberal values and strengthening religious fundamentalism.

GDP per capita as a measure of the level of economic development appears to have no significant link with religious fundamentalism or any of the components of liberal values. Closer scrutiny, however, shows that the reason GDP per capita has no effect is that Saudi Arabia is an outlier. The kingdom had by far the highest GDP per capita among the seven countries. At the same time, Saudis were least supportive of liberal values and strongly supportive of religious fundamentalism. These attributes, which are the opposite of what developmental theories of social change predict, significantly lower the value of the correlation coefficient, rendering it statistically insignificant.

However, GDP per capita is a crude measure of economic development and in some cases does not adequately capture the operational meaning of the concept of development. Economic development is a multifaceted, self-propelled, and autonomous process of change in various aspects of the national economy. The Saudi economy, although it has undergone remarkable transformation since the founding of the kingdom in 1932, does not quite conform to this conception of economic development. The country is the archetype of a rentier economy, where economic growth is a function of the amount of petroleum the kingdom sells on the international market. This growth hardly produces the types of change that the autonomous process of economic development tends to bring about in social structures—including the emergence of industrial workers who form a basis for the rise of labor unions, female labor force participation, and the rise of a professional class working in the research-and-development departments of different industries. These changes are expected to support changes in values. Without such changes, the basis for the development of modern values would be quite weak (Beblawi and Luciani 1987; Mahdavy 1970).

Therefore, if Saudi Arabia is excluded and the coefficients recalculated, the values of the correlation coefficients are significantly increased, showing that economic development is negatively linked to the religious fundamentalism index (r −.81, not shown in table 5.5) and positively linked to the indices of expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values (r = .84, .73, .87, and .85, respectively, not shown in table 5.5).

Globalization

The two measures of globalization—economic and cultural globalization—are variably linked to religious fundamentalism and liberal values. Economic globalization is negatively linked to religious fundamentalism (r = −.64), indicating economic globalization weakens religious fundamentalism. Economic globalization is positively linked only to expressive individualism (r = .81) and liberal values (r = .55), but has no significant link with the indices of gender equality and secular politics. Again, economic globalization’s weak relationship with religious fundamentalism and its lack of a significant relationship with the indices of gender equality and secular politics may be the result of Saudi Arabia being the outlier. If Saudi Arabia is excluded from the equation, then the values of the correlation coefficients between economic globalization and religious fundamentalism, expressive individualism, secular politics, and liberal values significantly increase (r −.80, .78, and .75, respectively, not shown in table 5.5). Still, the relationship between globalization and gender equality remains insignificant.

Likewise, the use of the internet, as an indicator of cultural globalization, is linked negatively to religious fundamentalism (r = −.61) and positively to expressive individualism and liberal values (r = .85 and .65, respectively), although having no significant linkages with the indices of secular politics and gender equality. Again, if Saudi Arabia is excluded, the values of the correlation coefficients between internet use and religious fundamentalism, expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values significantly increase (r −.76, .86, .81, .79, and .85, respectively, not shown in table 5.5). In sum, the enhanced international system of communication and information flow weakens religious fundamentalism and strengthens liberal values.

Alternatively, Saudi Arabia may lend credence to the view that globalization reflects a multidimensional or even contradictory process, indicating how globalization promotes conservatism and fundamentalist religious discourses. Saudi conservative religious institutions have in fact benefited by globalization as it enables them to engage in worldwide promotion of Wahhabi version of Islam, a distinctive style of mosques, and its own vestimentary form—Saudis as an exporter of its own Islamic culture.

Situation of Women

Contrary to our expectation, the first factor, female labor force participation, has no significant link to the index of religious fundamentalism. It is, however, positively linked to the indices of gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values (r = .74, .69, and .60, respectively). Thus, when the percentage of women who are active in the labor force is higher in a country, support for liberal values is stronger in that country.

However, the second factor, sex ratio, is positively correlated with the religious fundamentalism index and negatively correlated with the indices of gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values, as shown in table 5.5 (r = .59, −.64, −.86, and −.64, respectively). These findings thus support the argument that the more a society’s sex ratio is unbalanced in favor of men (i.e., a higher sex ratio), the stronger the patriarchal institutions and religious fundamentalism are, and the weaker the social support for liberal values is. Neither of these structural variables is significantly linked to the index of expressive individualism.

Summary

This chapter focused on variation in Islamic fundamentalism and liberal values across the seven countries. It showed that, in the same way religious fundamentalism and liberal values were inversely related on the micro (individual) level, the aggregate indices of the two constructs were negatively linked on the macro (country) level; countries that scored higher on the aggregate fundamentalism index scored lower on the aggregate indices of expressive individualism, gender equality, secular politics, and liberal values.

The chapter also assessed (1) the extent to which cross-national variation in aggregate fundamentalism and liberal values was influenced by such variable features of the national context as the structure of the religious environment, state structures and interventions in religion, economic development, economic and cultural globalization, and the situation of women in terms of female labor force participation and the sex ratio and (2) the direction of the relationships of these varying features of the national context with religious fundamentalism and liberal values. The analysis showed that religious fundamentalism was weaker and liberal values were stronger in a national context characterized by greater religious liberty, a more fragmented state power structure, greater globalization, and higher female labor force participation. Conversely, religious fundamentalism was stronger and liberal values were weaker where there was a stronger exclusionary state, greater government regulation of religion, and a higher sex ratio. Fundamentalism was also negatively linked to religious fractionalization, and liberal values to greater female labor force participation.

The linkages between the macro variables and expressive individualism only partially conformed to this pattern. Expressive individualism was linked positively only to the measures of religious liberty as well as economic and cultural globalization, and negatively to government regulation of religion. Globalization, however, indicated a relationship with expressive individualism, thus providing a favorable context for overall aggregate individual self-expression. The economic components of the national context, however, bore no significant relationship to attitudes toward gender equality or secular politics. Religious liberty, attributes of the state, and the situation of women were significantly linked to the indices of both gender equality and secular politics, religious liberty, fragmentation ratio, and female labor force participation were positively linked to these indices, while political exclusion, government regulation of religion, and sex ration were negatively linked.

The contrast between the predictors of expressive individualism, on the one hand, and gender equality and secular politics, on the other hand, is instructive. Expressive individualism is more directly linked to globalization, because the latter contributes to economic and cultural diversity and, as a result, a more favorable context for individual self-expression. Gender equality and secular politics, by contrast, are affected by factors related to distribution of power and political and religious freedom. Government regulation of religion, however, is the only factor that is significantly linked to religious fundamentalism and the indices of liberal values and its components, supporting the view that government regulation of religion not only more than other macro indicators reinforces religious fundamentalism but weakens all the components of liberal values as well.