Putting Women at the Center of Policymaking

Public Solutions to Help Women Push Back from the Brink

By Melissa Boteach and Shawn Fremstad

If women working full time, year round, were paid the same for their work as comparable men, we would cut the poverty rate for working women and their families in half.

In the 50 years since President Lyndon Johnson issued his War on Poverty declaration, much has changed for women and families. The share of young women in college has doubled, with women’s attendance rates surpassing men’s since the late 1980s. The share of women who are both breadwinners and caregivers has steadily increased. The gender wage gap has narrowed considerably, though a substantial gap still remains. And the value of the minimum wage, both in inflation-adjusted terms and as a percentage of the average wage, has declined.

Public policies have played an important role in all of these trends, along with cultural, technological, and social changes. Still, our public policies haven’t adjusted to a world in which nearly two-thirds of mothers are primary or co-breadwinners. The consequences have been particularly troubling for low-income mothers, who are much less likely to receive decent wages and family-friendly benefits from their employers than other working moms.

Britani Hood-Mongar works in the cafeteria at an elementary school in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Because she is considered a contractor, she is not eligible for benefits like paid sick leave or family leave. {BARBARA KINNEY}

We need new policy prescriptions for a new time—ones that will benefit these women, and strengthen our economy as well.

To enact these new policies, we must first ask a game-changing question: How do we put women and their families at the center of our public policymaking? In a woman’s nation, every woman who wants to work should be able to join the labor force, and women should earn equal pay to their male counterparts. Unfortunately, we are still far from achieving these goals.

Currently, 70.5 percent of working-age women participate in the labor force compared to 83.1 percent of working-age men.1 While some women may choose not to work, the lack of policies to help families manage conflicts between work and family takes the choice of working away from too many women. In fact, between 1990 and 2010, the United States dropped from 6th to 17th in female labor force participation among 22 developed countries. More than a quarter of our relative drop was attributable to the fact that other developed countries expanded “family-friendly” policies such as parental leave, while the United States largely stagnated in enacting policies to help women balance the demands of work and care.2

As we outline throughout our report, women in the labor force face a persistent wage gap that undermines their economic security, earning 77 cents for every dollar earned by men. As economists Heidi Hartmann and Jeffrey Hayes of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research have found, if women working full time, year round were paid the same for their work as comparable men, they would earn $6,250 more a year on average. This increased income would cut the poverty rate for working women and their families in half. Of the 5.8 million working women living below the poverty line, just over 3 million would be raised above it. And the U.S. gross domestic product would increase by 2.9 percent, or $450 billion, an amount roughly equal in size to Virginia’s economy. The economic benefits could not be clearer.

With so much at stake, how do we remove barriers for women and unleash their economic potential?

Some key public solutions could help millions of women and their families join the middle class, and strengthen the nation’s economy. It is essential to remember that today’s women are increasingly both caregivers and breadwinners, and they face serious tradeoffs in both of these roles. To help women manage their care responsibilities in a way that bolsters their potential as breadwinners, we need to ensure that workers at all income levels have access to paid time off as well as access to affordable and high-quality child care and preschool—like nearly all other developed nations. We also need to ensure that women get fair and equal pay, and that they have access to the public supports and educational opportunities they need to put themselves on a stable path to middle-class economic security.

RECOGNIZING CARE

Women have long performed, without pay, the central human work of caring for children, the sick, and the elderly. And as Riane Eisler and Kimberly Otis note in Heather Boushey’s chapter, to this day, the economic value of this work largely goes unrecognized. Care work, for example, is only counted toward GDP when it is provided for pay.3

As women have joined the workforce in increasing numbers, they have turned to both formal and informal care providers, often at considerable expense. At the same time, only so much of parents’ care responsibilities can be—or should be—outsourced. Even with affordable child care, a working parent still needs to take time off to care for a sick child. And taking family leave to care for a new infant should be encouraged and supported. Yet, for the most part, our public policies don’t recognize the impact these care responsibilities have on workers.

OFFERING PAID FAMILY LEAVE INSURANCE

Fifty years ago, about half of all married mothers were “stay-at-home” moms who weren’t in the labor force at all.4 Today, only one-fifth of married moms stay at home, and a greater share of all mothers are unmarried and in the labor force. As a result, most mothers today have to balance their caregiving roles with their breadwinning ones.

Nationwide only about 12 percent of American workers have access to paid family leave through their employers to care for a new child or seriously ill family member.

Many well-paid professionals and managers have paid family leave benefits that allow them to take time off to meet these family responsibilities, while still meeting their breadwinning responsibilities. And three states—California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—operate paid family leave insurance programs.

California’s program, for example, effectively provides up to six weeks of partial wage replacement per year for covered workers to care for a new child or a seriously ill family member. For mothers, these benefits are in addition to the 10 to 12 weeks of partial wage replacement for covered pregnant and postpartum workers under California’s temporary disability insurance program.5

But nationwide, only about 12 percent of American workers have access to paid family leave through their employers to care for a new child or seriously ill family member.6 Workers without paid family leave cobble together paid sick days or vacation days—which are typically inadequate, if available at all—or they take unpaid leave if they can afford it, or leave their jobs altogether. Either caregiving comes at the expense of breadwinning or the other way around.

Paid family leave for the price of a cup of coffee

Legislation recently introduced in the U.S. Congress, and modeled on the existing state family leave programs, would enable more breadwinners to accrue paid family leave to help balance their work and care responsibilities. The Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act, or FAMILY Act, is a proposed social insurance program that would give all workers the ability to earn up to 12 weeks of paid leave to care for a new child, a seriously ill family member, or the worker’s own serious illness. Benefits would equal two-thirds of a worker’s typical wages up to a capped amount.

The program would be funded by a small increase in the payroll tax that would be shared by employers and employees. The cost for the average full-time worker earning the median hourly wage would be about $1.50 per week, less than a small cup of coffee at Starbucks.7

Under the proposed legislation, a worker’s eligibility for leave would depend on whether he or she has sufficient past work history, with the amount of past work required increasing with age. For instance, a new parent under age 24 would need to have worked in at least six calendar quarters in the past three years to be eligible, while one between the ages of 24 and 30 would need to have worked in at least half of the calendar quarters between age 21 and their leave date.

Workers in poorly compensated jobs, who are disproportionately women on the financial brink, bear the greatest financial burdens and are the least likely to have paid time off of any sort. Additionally, the lack of paid leave likely contributes to the gender gaps in both pay and employment.

A growing body of research suggests that allowing all workers to earn paid family leave would have long-term benefits, beyond the partial replacement of earnings it provides for workers, their families, and the overall economy. Most importantly, research suggests that paid family leave will increase the employment of women on the brink who are caregivers, mostly by increasing the share of women who will return to the same employer after taking leave.8

Case in point: Comparing outcomes for working women who took paid leave after a child’s birth with those of new mothers who did not, Rutgers University researchers have found that the women taking paid leave were more likely to be working 9 to 12 months after a child’s birth, more likely to report wage increases in the year following a child’s birth, and less likely to receive public assistance.9

All forms of the modern American family could benefit from paid family leave. Providing paid sick days would also have broad public health benefits. {BARBARA KINNEY, JAN SONNEMAIR, BARBARA RIES}

By making the workplace more family friendly, a national paid family leave program will help close the gender gaps in employment and wages, while bolstering women’s long-term economic security. New mothers and family caregivers who return to work after their leave, instead of dropping out of the labor force for longer periods of time, will boost their lifetime earnings, be more likely to earn further raises and promotions, and accumulate greater retirement savings through Social Security.

In today’s world, where more mothers work than stay home, paid family leave’s time has come. It is one of the most effective ways the government can adapt to the realities of today’s families, and one of the surest ways to increase the economic stability of women on the brink.

PROVIDING PAID SICK DAYS

Paid family leave is designed to help workers meet caregiving responsibilities that typically last weeks. But, of course, workers also need time to address short-term health and medical issues: a child home from school with the flu, an elderly parent’s medical emergency, or their own illness.

Unfortunately, 39 percent of private-sector workers do not have a single paid sick day.10 Even worse, 71 percent of private-sector workers in low-wage jobs—which are disproportionately held by women—go without any paid sick days.11 Working caregivers without paid sick days often have to make lose-lose choices: send a child to daycare with the flu or sacrifice a day’s wages that were going to pay for this week’s groceries? Go into work with a contagious cold, or risk losing the job altogether in this tough economy?

A whopping 87 percent of women on the brink—and 96 percent of single mothers—said paid sick days would be “very useful” to them; our poll found it to be the number one policy they thought would help them—even more than an increase in wages or benefits.

The solution is simple: a basic national standard that enables workers to earn paid, job-protected sick days. One national proposal, the Healthy Families Act introduced in Congress in 2013, would ensure that workers in businesses with 15 or more employees are able to earn one hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked, up to seven days annually.13

There is growing momentum for this type of change. In 2012, Connecticut became the first state to adopt a law that allows a substantial share of workers to earn paid sick days. And in 2013, Portland, Oregon and New York City became the fourth and fifth major cities to adopt paid sick days laws, joining San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

Typically, these laws allow workers to earn five or more days of paid sick leave annually. In San Francisco, for example, workers earn one hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked, up to nine days annually, or five days if they work for employers with 10 or fewer employees.

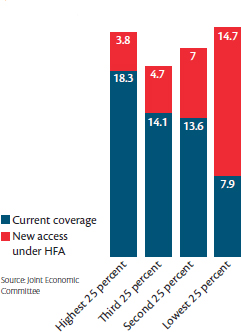

FIGURE 1

Number of workers who would gain paid sick days under Healthy Families Act, by wage percentile

(in millions)

Source: Joint Economic Committee

Sick and fired: Elose’s story

Elose worked as a dishwasher in a Miami restaurant to support her teenage son and relatives living back in her home country of Haiti. One day, Elose’s boss told her to hurry and do the job as fast as she possibly could. In her rush around the kitchen, she slammed her hand in the dishwasher door, injuring herself badly.

She went to the clinic to get treated, but as Elose notes, when she returned, “Without even asking me how I was and without explanation, my boss told me that I no longer had my job at the restaurant. I was in shock. I went home sick for getting hurt on the job, and was fired when I returned with a doctor’s note. … Getting fired was devastating.”

Elose says this wasn’t just her problem. At the restaurant where she worked, “I noticed many people would come to work sick because when calling in sick the boss would say they’d need to come in anyway.”

Elose and her colleagues were vulnerable because they, like 71 percent of private-sector workers in low-wage jobs, had no job-protected paid sick days.12

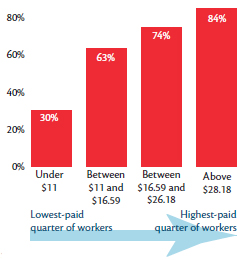

FIGURE 2

Share of workers with access to paid sick leave, by wage percentile

Source: National Compensation Survey

As with paid family leave, a national standard for paid sick leave would increase the financial security of the millions of workers currently unable to take paid time off to care for a sick child or themselves when ill. Low-income, working women, who are constantly juggling their caregiving and breadwinning roles, would be among those helped the most. According to the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, of the roughly 30 million additional workers who would have access to paid sick leave under the Healthy Families Act, nearly half are working in jobs that pay less than $11.50 an hour.14

In addition, providing paid sick days would have broad public health benefits. Nobody wants a cook with a bad case of the flu preparing his or her lunch, or a child care worker with a contagious illness taking care of his or her child. But millions of workers in these and similar industries involving direct interpersonal contact go without paid sick days, including the workers in the Miami restaurant where Elose worked.15 (see text box) And low pay in these same jobs likely limits the extent to which many sick workers can take unpaid time off.

A national standard, like the one in the Healthy Families Act, would ensure that the vast majority of these workers are able to earn paid sick leave, allowing them to stay home when it’s the best thing for their health and yours.

ENSURING ACCESS TO QUALITY PRESCHOOL AND CHILD CARE

There are 7.6 million U.S. families with children under age 6 living on the financial brink.16 If more of the mothers in these families were able to work steadily in a decent job, many of them would be able to move away from the brink and toward the middle class.

Low-income mothers are especially in need: quality child care assistance is associated with increased employment and earnings. {BARBARA KINNEY}

Let’s look at single mothers. Four out of every five single mothers with young children had incomes that put them on the economic brink in 2012. But when these mothers are able to work full time, year round, they’re twice as likely to have incomes that lift them off the brink. While far too many of these working mothers are still struggling to make ends meet, having earnings from a full-time job can make a big difference.17

However, to work full time, year round, mothers of young children need child care and preschool options that they can trust and afford. Not surprisingly, considerable economic research shows that receiving child care assistance is associated with increased employment and earnings among low-income mothers.18 Further, high-quality preschool delivers considerable long-term economic benefits. Jennifer’s story (see textbox) shows the power of affordable, quality preschool to help mothers work, as well as to improve outcomes for their children, delivering long-term economic benefits.

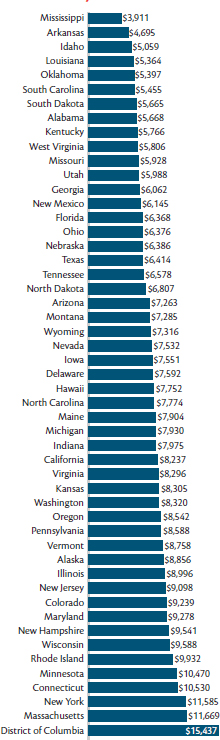

FIGURE 3

Average costs for center-based care for a 4-year-old in 2011

Source: Child Care Aware of America January 2012 Survey of State Child Care Resource and Referral Networks.

Rigorous studies have found that for every $1 invested in high-quality preschool, we save an average of $7 in future public costs due to reductions in crime and the need for remedial education, and increases in workers’ productivity.19 In our poll, 88 percent of women on the brink said that providing affordable child care to working families would improve the nation’s economic security and 64 percent of them strongly favored it as a government economic policy.

Yet the average market cost of a full-time spot in a child care center for a 4-year-old ranges from $3,911 a year (in Mississippi) to $15,437 a year (in Washington, D.C.).20 With the majority of working women earning less than $30,000 a year, many families are priced out of quality care, or pay an amount disproportionate to their earnings. Of the 3.13 million working mothers with preschoolers and a family income below 200 percent of the poverty line, just over 1 million make payments for child care. On average, the amount these mothers spend on child care each week is equal to more than one-third of their personal income.21

What about the low-income, working mothers of preschoolers who can’t afford child care? Most rely on family members and friends to help. After fathers, grandparents play the biggest role, serving as the primary child care providers to nearly 900,000 preschool children of low-income, working moms.22

A head start for families: Jennifer’s story

When Jennifer’s husband lost his welding job during the Great Recession, she started working to help support the family. Unfortunately, the couple, residing in southeast Arkansas, couldn’t afford daycare.

Thankfully, the family found the Hamburg Arkansas Better Chance, or ABC, program which received federal funding from several sources, including Head Start. With daycare taken care of, Jennifer’s husband was able to take the time to find other employment, and Jennifer could hold down two jobs to help keep the family afloat.

She writes, “If this ABC program wasn’t available, over half of that [income] would’ve been spent on daycare.” The ABC program also helped two of her children with developmental disabilities and emotional and social problems reach critical milestones and make important progress.

Jennifer was one of the lucky ones. Today, only about 18 percent of eligible children receive federally funded child care assistance, and while nationwide preschool enrollment has increased in recent years, the lowest-income children are the least likely to participate in preschool programs.25

Existing child care assistance and preschool programs help, but they remain underfunded and a patchwork. Because of insufficient funding, only about 18 percent of eligible children actually receive federally funded child care assistance.23 Similarly, the Head Start program, which provides early learning opportunities for low-income children, serves just 8 percent of all 3-year-olds and 11 percent of all 4-year-olds, and state preschool programs serve just 28 percent of 4-year-olds and 4 percent of 3-year-olds.24

We need to build on these existing systems to enable every child to attend two years of high-quality, full-day preschool. We must ensure that working mothers have affordable, quality child care options for their young children.

In his most recent budget, President Barack Obama took a historic step toward these goals. His Preschool for All initiative would create a new federal-state partnership to substantially expand the availability of high-quality preschool.26 States would be able to receive federal funding to extend preschool to all 4-year-olds from low- and moderate-income families, and they would have financial incentives to expand access to middle-class families.

In our poll, 88 percent of women on the brink said that providing high-quality, affordable child care to working families would improve the nation’s economic security.

We also need to address the “child care cliff” in many states for parents who receive child care assistance; when a parent’s earnings increase, even a bit, she may find herself over an income threshold, and no longer eligible for child care assistance. This income limit or cliff can mean that to pay for child care, a working parent ends up with considerably less take-home pay despite getting a raise or working more hours. Some struggling single parents turn down raises or promotions, and even ask for pay cuts, to avoid going off the cliff.27

To address these problems, we need to increase our investment in the Child Care and Development Fund, the primary source of federal funding for child care assistance for low- and moderate-income families. We need to turn the cliff into a gradual off ramp for parents working their way into the middle class.

Finally, we need to improve the quality of care by improving the required qualifications of the early childhood workforce, as well as their compensation. Under the president’s Preschool for All proposal, states would need to meet quality standards to receive federal funds, including requiring preschool teachers to have a bachelor’s degree and ongoing professional development, as well as requiring preschool staff salaries to be comparable to K-12 salaries. Similar reforms should be made to improve the quality of child care provided with federal dollars under the Child Care and Development Fund.28

GIVING CAREGIVERS A RIGHT TO REQUEST FLEXIBLE WORK ARRANGEMENTS

For many working women, including those in well-compensated professional jobs, the hours and lack of flexibility interfere with their family obligations. Women in low-paying fields such as health care, retail, and the restaurant industry often work too few hours to financially support their families and are more likely to face unpredictable and unstable schedules.

Kristy Richardson talks with Robert Davis, a housing case manager at the Veterans Leadership Program of Western Pennsylvania. Much of her life is spent waiting to meet with someone who may be able to help her family get by. {MELISSA FARLOW}

We can do much more to encourage employers to allow flexible work arrangements for employees who want them, as well as more predictable, stable scheduling practices in poorly compensated service jobs. Flexible work arrangements include nontraditional start and end times for work, compressed work weeks, the ability to reduce hours worked, and the ability to work from home.

Less than half of employers currently offer flexible work arrangements to their employees. But the business case for allowing flexible work arrangements is strong. Researchers have found that employees with access to flexible work arrangements tend to be more satisfied and engaged with their jobs.29 These factors have been found to increase productivity and employee retention, both of which improve a business’s bottom line.30 Examples of companies implementing flexible work arrangements—and what practices are working best for each organization—are highlighted in detail by Ellen Galinsky, James T. Bond, and Eve Tahmincioglu in the Private Solutions chapter.

As we pointed out in our first report, in the United Kingdom and several other countries, parents and caregivers have a “right to request” flexible work arrangements to accommodate caregiving responsibilities. Under U.K. law, an employer must meet with an employee requesting flexible work and make a decision about whether to accommodate the employee’s request within two weeks of the meeting.31 Employers can reject the request, but only for business-related reasons specified in the law. Vermont became the first U.S. state to adopt a right-to-request law last year; employers can generally refuse an employee’s request, but they have to discuss the request with the employee in good faith.32

In June 2013, Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) and Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA) introduced legislation that would give all U.S. employees the right to request flexible work arrangements from their employers.33 Employers would be required to respond to applications made by employees. If an employer were to reject an application, he or she would be required to provide the reasons to the employee in writing.

Although employees wouldn’t be able to challenge an employer who denies a request, simply formalizing the right to request may have a positive effect on employers’ responsiveness to flexible work. According to the Confederation of British Industries, the largest employers’ organization in the United Kingdom, the right to request flexible work “has made huge strides in promoting different ways of working—with nine out of 10 requests accepted by employers.”34

BOOSTING INCOMES FOR WOMEN BREADWINNERS

Seventy percent of Americans believe the financial contribution women make to our national economy is essential. Yet as Heather Boushey’s chapter explores, women are disproportionately consigned to low-wage work, with incomes that leave them unable to support a family, including in critical care professions set to grow over the next decade.

In trying to access the work and income supports women need to care for their families, they face a daunting web of bureaucracy. And when trying to access educational opportunities to move off the brink, women face a lack of information and support in moving into higher-paying fields.

To help millions of women push back from the brink, we must boost the incomes of female breadwinners by improving the quality of low-wage jobs, streamlining access to work and income supports, paving the path toward higher education, and ensuring equal pay.

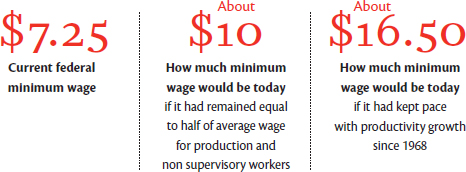

Minimum wage fails to keep pace

Source: Janelle Jones and John Schmitt, “The Minimum Wage is Not What it Used To Be,” CEPR Blog, July 17, 2013, available at http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/cepr-blog/the-minimum-wage-is-not-what-it-used-to-be.

INCREASING THE MINIMUM WAGE

Our economy and our families are stronger when we reward an honest day’s work with honest wages and benefits, regardless of a worker’s gender. Increasing the minimum wage would help us reach this goal. As President Obama noted in his 2013 State of the Union address, an increase in the minimum wage “would mean customers with more money in their pockets. And a whole lot of folks out there would probably need less help from government.”

For nearly 25 years following World War II, the minimum wage provided an adequate floor, one that was regularly adjusted to keep pace with increases in productivity. In 1964, the minimum wage was equal to half of the average wage for production workers. But not long after that, federal policymakers let the value of the minimum wage decline. If the minimum wage today were at the same level relative to the average production worker 50 years ago, it would be just over $10 per hour. If it had been adjusted over roughly the same period to keep pace with gains in productivity, it would be about $16.50 an hour.36

The minimum wage should put a floor under wages, one that ensures employers pay enough for their workers to afford the basics. If employers don’t pay their workers enough to maintain spending on necessities such as food, housing, clothing, transportation, and other items, families and our economy suffer. Increasing the minimum wage to $10.10 over the next two years would mean as much as $51 billion in additional earnings for poorly compensated workers during this period.37

Fulfilling the Affordable Care Act’s promise for women on the brink

Access to affordable health care is essential to women’s economic security and well-being. Without insurance, a broken bone or a child’s asthma attack can quickly drain a family’s savings and lead to bankruptcy. Without access to routine checkups, a preventable illness can quickly escalate.

Yet about 18.9 million nonelderly women were uninsured in 2012.43 Just over half of them will be eligible for Medicaid starting in 2014, as long as they live in states that take the Affordable Care Act’s option to extend coverage to them.44 While roughly half of states have approved or are moving toward the Medicaid expansion, in the other states, debate about whether or not to expand Medicaid is ongoing or not under consideration at this time.

The hold-out states should go forward with the expansion, which is in the best interest of the people they represent. From 2014 through 2016, the federal government will cover all of the costs of expanding Medicaid. After that, states will need to pay for only a modest share of the costs (5 percent in 2017, increasing by 1 percent up to a maximum of 10 percent in 2020 and beyond).

As a practical matter, states that adopt the expansion will improve their balance sheets and their economies because the expansion will create jobs and allow states to draw down federal funding for certain health care services they’re already providing. In Ohio, for example, projections show that implementing the expansion is expected to result in $1.9 billion in savings and increased revenues by 2022.45 In contrast, states that fail to take up the expansion will deny health insurance to tens of thousands of low-income workers and harm their states’ balance sheets.

Low-income workers are more likely than other workers to spend any pay increases on necessities that they couldn’t afford before. Grocery stores, clothing stores, and other retailers would all benefit from the increased spending power of these workers. In fact, in a recent nationally representative poll, two out of every three small business owners supported the increase.38

There is growing momentum for raising the minimum wage, as more than 20 states already have minimum wages higher than the federal level.39 In September 2013, California became the latest state to raise the minimum wage, hiking it to $10 an hour by 2016.40

At the federal level, we should follow California’s example and gradually raise the nation’s minimum wage from $7.25 to at least $10.10 per hour and then update it annually, as Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) and Rep. George Miller (D-CA) have proposed.41 We should also increase the minimum wage for employees who receive tips, from $2.13 to at least $7 per hour. These increases would be particularly helpful for low-income women. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women are twice as likely as men to be paid wages at or below the minimum wage.42

Allie Winans and her two daughters rely on multiple prescriptions and numerous doctors’ visits every week. These health care costs have driven their family to the financial brink. {AMI VITALE}

STREAMLINING AND MODERNIZING PUBLIC WORK SUPPORTS

For women on the brink and other poorly compensated breadwinners, one of the most important developments over the past several decades has been the establishment and gradual expansion of public work supports. These include Medicaid; the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP (formerly food stamps); the earned income tax credit and child tax credit; and child care assistance. These programs acknowledge that many jobs in our economy don’t pay adequate wages or provide essential benefits for families.

Work supports are incredibly effective. In 2011, for example, the earned income tax credit and child tax credit made it possible for 9.4 million people in working families with children to live above the poverty line.46

Unfortunately, obtaining these supports is too often a time-consuming and byzantine process, especially for low-wage workers juggling work and caregiving responsibilities with little time to wait in line at a government office. This is especially the case for low-wage workers seeking more than a single work support. A working mother with low earnings, for example, may be eligible for Medicaid, SNAP benefits, and child care assistance. But in many states, in order to access and maintain benefits, she has to navigate two or three different and largely uncoordinated processes. If you haven’t been through a typical application process yourself, imagine a tedious trip to your DMV office, multiply that by two or more, and you start to get the picture.

States need to streamline and coordinate the delivery of work supports in ways that reduce burdens on both the families seeking benefits and the agencies providing them. Many states are already well on the way. As California’s first lady, Maria Shriver developed WE Connect, a public-private partnership established in 2005. WE Connect works with organizations in underserved communities to connect families to resources such as the earned income tax credit, California’s Healthy Families Program, and CalFresh. The program continues to help millions of Californians through its community events, web-based tools, public-private partnerships, and collateral materials. Through her leadership, Shriver has connected more than 20 million Californians with programs and services in an effort to promote healthier and more financially independent lives. 47

Florida is also on its way, having completely modernized the way it delivers SNAP and other benefits over the past decade through its Automated Community Connection to Economic Self Sufficiency, or ACCESS, Florida initiative. The state changed eligibility rules to better align programs, shifted largely to an online application process, reduced other paperwork required from applicants, and made a number of other changes to streamline the process. Today, about 95 percent of applications for benefits in Florida are made online, rather than through a paper application process, and the state has reduced the costs of taking and processing applications by hundreds of millions of dollars.48

The Work Support Strategies Initiative, a multiyear demonstration project funded by the Ford Foundation and several other major foundations, is currently working with a select group of states to design, test, and implement “21st century” approaches that will make it easier for families to get the work supports for which they are eligible. As noted in Gov. C.L. “Butch” Otter’s (R-ID) essay following this chapter, these modern approaches aim to deliver work supports more effectively and efficiently through technologically savvy and customer-driven methods of eligibility determination, enrollment, and retention.49

At the federal level, it is imperative that Congress continues to support and incentivize state efforts to modernize benefit systems. The Affordable Care Act provides enhanced federal funding to modernize benefit systems through 2015. State human services directors have called for extending that funding to give them more time to complete the challenging task of overhauling systems.

States should also be given the option to enroll eligible adults in Medicaid based on information the individual has already provided when applying for SNAP benefits; the existing option to do this for children, set to expire in September 2014, should be made permanent. A recent review by the Government Accountability Office found that this option has produced substantial administrative savings, while increasing the number of children with health insurance.50

OPENING DOORS FOR TOMORROW’S BREADWINNERS AND CAREGIVERS

As Anthony Carnevale and Nicole Smith explain in their chapter for this report, a college degree or other postsecondary education in well-paying fields can make a tremendous difference in the lives of women and their children.

Women have made considerable progress in education over the past five decades. Today, some 38 percent of women between the ages of 25 and 34 have a four-year college degree or higher, compared to 31 percent of men.51 Yet that still leaves most young women without a four-year degree. And only 14 percent of low-income women in this age range have a four-year degree.52 We need to ensure that college is affordable for young women and men, and that they have the preparation and support they need to enter and complete college.

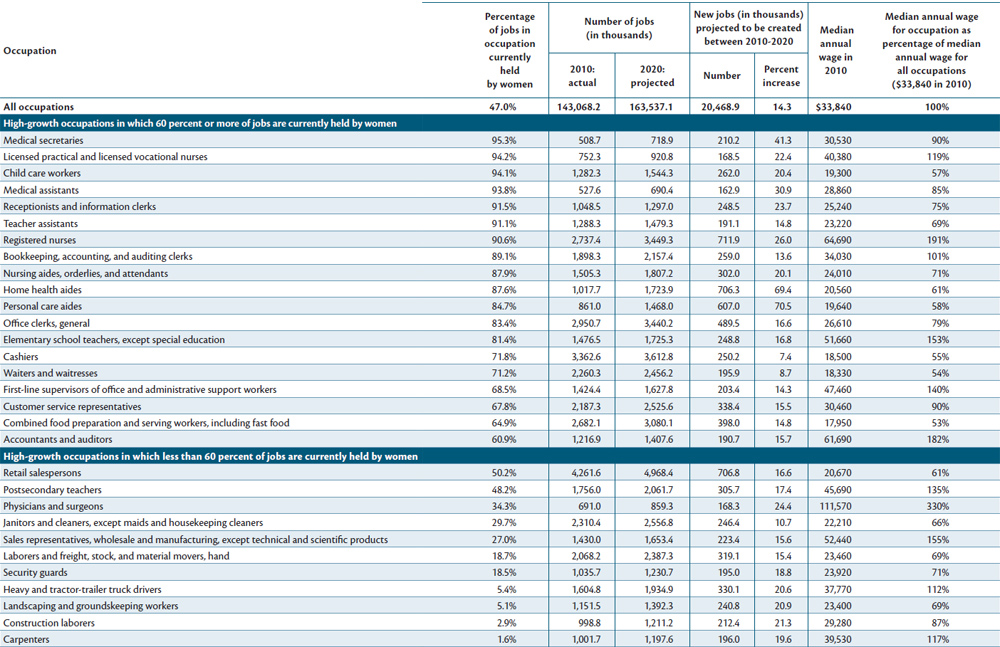

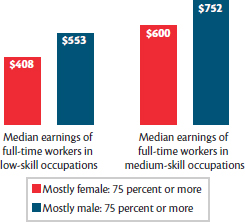

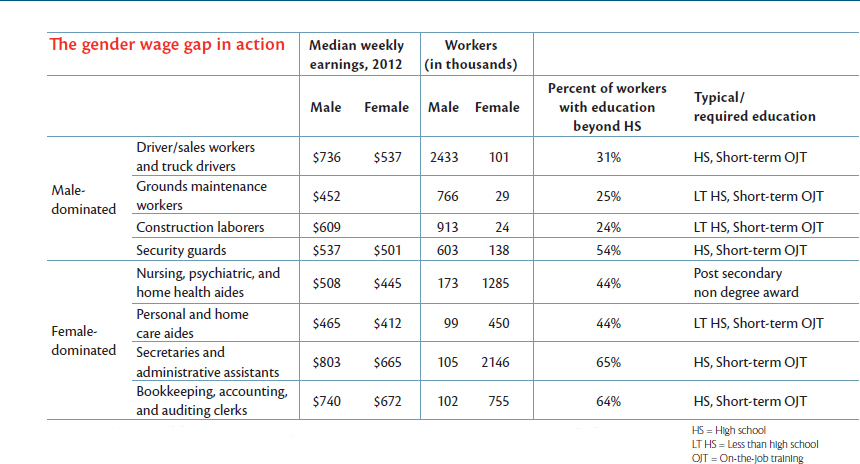

It is also important to remember that the gender gap in wages is partly driven by a gender gap in occupations, which exists even after taking educational requirements into account. Two-thirds of women work in just 5 percent of occupational categories.53 And, with the exception of teaching and nursing, the jobs in these categories are among the lowest-paying in our economy.

Investing in the future for her sons, Jessica McGowan is working towards her degree at Virginia College School of Business and Health in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She also works another part-time job. {BARBARA KINNEY}

Women are particularly underrepresented in well-paying “STEM” occupations—science, technology, engineering, and math—as well as many occupations that provide good jobs without requiring a college education. For instance, neither the male-dominated occupation of truck driver nor the female-dominated occupation of child care worker requires more than short-term, on-the-job training. But the typical heavy truck driver earns $18.37 an hour while the typical child care worker earns only $9.38 an hour.54

Two-thirds of women work in just 5 percent of occupational categories. And, with the exception of teaching and nursing, the jobs in these categories are among the lowest-paying in our economy.

One important step is to make sure young women have the information and advice they need to make smart education and career decisions. While students can get information on a school’s ranking on particular subject matters, teachers, or campus life, little public information is available on average student debt or starting salaries for students graduating from various programs. This type of information is critical for all students, but especially for lower-income students who can ill afford a misstep with the limited dollars they have to spend on higher education or training.

The Obama administration’s efforts to produce a college scorecard have promise, but only when information on earnings, particularly at the program level, become available. Bipartisan legislation such as the Student Right to Know Before You Go Act proposed by Sens. Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) could speed implementation of these initiatives, helping to connect women on the brink with the information they need to make informed decisions about careers.

Finally, we need to enforce existing equal pay and equal opportunity laws. There is evidence that discrimination is one factor contributing to the gender gap in STEM fields. A 2012 study showed that science faculty at research universities rated male applicants higher than identical female applicants and offered male applicants higher starting salaries as well as more career mentoring.55

The vigorous enforcement of Title IX in school sports has dramatically increased the participation of women and girls in school sports activities. The National Women’s Law Center recommends that the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights strengthen the enforcement of Title IX by conducting compliance reviews of schools to ensure that women and girls have equal access to STEM fields and classes.

All federal science agencies should conduct similar reviews for their grantee institutions. Similarly, the Office of Vocational Education could publish a proactive roadmap on how educational institutions can recruit and retain students in nontraditional gender fields. Educational institutions could hold regular trainings for teachers and administrators about Title IX, address factors that could discourage girls and women such as harassment and lack of mentorship, and work to make campuses more welcoming for female teachers in STEM fields to increase the number of role models for women and girls interested in entering these sectors.56

WHEN BREADWINNING IS CAREGIVING: A FAIRER DEAL FOR CARE WORKERS AND DOMESTIC WORKERS

About 4.5 million people are paid care workers; these jobs include child care workers, nursing aides, personal and home care aides, and home health aides.57 About 89 percent of these paid care workers are women. And nearly half are black, Hispanic, or Asian.58

The good news for women interested in these fields is that the jobs are plentiful and growing rapidly. According to projections by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of jobs in child care and adult care will grow by more than 1 million between 2010 and 2020. In percentage terms, two adult care occupations—personal care aide and home health aide—are currently the two fastest-growing occupations in the United States, with both needing 70 percent more workers by 2020.59

But the bad news is that these workers are paid much less than workers on average, and too few of them receive health, retirement, and other benefits. The typical wage for a child care worker in 2012 was only $9.38 an hour ($19,510 annually); for a home health aide, it was $10 an hour.60 Nearly one out of every three adult and child care workers are uninsured, and roughly three-quarters do not have employer-provided retirement benefits.61

Sabrina Jenkins of Goose Creek, South Carolina, meets with occupational therapist Tania McElveen. Sabrina has rheumatoid arthritis and has been receiving care to restore movement—even simple exercises are painful. {CALLIE SHELL}

The workers who care for our children, parents, and grandparents, often women on the brink, deserve a better deal. Policies discussed in this chapter including raising the minimum wage, increasing access to benefits, and expanding educational opportunities are essential parts of that deal.

But we also need to reform the very structure of these jobs. Along these lines, Caring Across Generations, a campaign formed in 2011, has developed a policy agenda focused on both improving the quality of the care provided by adult care workers, and ensuring that these jobs come with basic rights and a career ladder for workers.62 An important step forward came in September 2013 when the Obama administration finalized a rule that will end the exclusion of nearly 2 million home care workers from minimum wage and overtime protections starting in January 2015.63 While the rule will improve the basic economic security of many home care workers, there is still much more work to do to help the women who care for our aging and disabled family members to push back from the brink.

The 30 occupations projected to add the most new jobs by 2020: Most already have female majorities, but few pay above median wages

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Projections Program and Table 11 in Bureau of Labor Statistics, Household Data Annual Averages. This table lists the 30 occupations that the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects will add the most jobs during the current decade, sorted by the share of jobs in each occupation currently held by women. For example, BLS projects that there will between 706,800 more people working as home health aides in 2020 than in 2010. The home health aide occupation is currently dominated by women, who account for 87.6 percent of workers, and pays only 61 percent of the overall median wage for all occupations. Women currently hold more than 60 percent of the jobs in 19 of the top 30 high-growth jobs. Only 5 of the top 15 growth jobs pay wages above the overall median. But only six of the disproportionately female jobs listed here typically pay wages that are above the overall median wage.

Because federal and state governments play a major role in financing care services through programs such as Medicaid, they could play a major role in improving compensation of the workers who provide these services. The government already plays such a role in certain male-dominated sectors such as the construction of highways and other public works. The Davis-Bacon Act effectively requires companies and employers working on federally funded infrastructure work to pay decent wages to their workers. It’s time to apply a similar standard to ensure that public funds are being used to create living-wage jobs in the female-dominated care sectors.

Home care or domestic workers—workers in private households who provide care, housekeeping, or various other services—are among the most vulnerable of all care workers. While the new rule on extending minimum wage and overtime laws to domestic workers is a step forward, these workers are often excluded from other basic labor standards that apply to the vast majority of the workforce.

A growing number of states have adopted or are considering Domestic Worker Bill of Rights laws. These laws would ensure that domestic workers have basic employment protections, such as an eight-hour day, overtime protections, and paid time off. These laws would also extend other protections specific to the unique circumstances of domestic work, such as a right to a minimum number of hours of uninterrupted sleep under adequate conditions.

New York approved Domestic Worker Bill of Rights legislation in 2010, and California and Hawaii approved legislation in 2013. In addition to state-level initiatives like this, we need a nationwide Domestic Worker Bill of Rights, as Ai-jen Poo calls for in this report. Basic labor standards such as these are a win-win—when domestic workers are better off, the people they care for are better off.

ENSURING EQUAL PAY

Many of the solutions discussed in this chapter would help close the wage gap, by helping women balance their roles as breadwinners and caregivers, improving the quality of low-wage work, better enforcing current equal opportunity laws, and providing better pathways into nontraditional, higher-paying fields. But even when controlling for education, experience, occupational choice, and time out of the labor market, there is still an unexplainable gap between men’s and women’s wages.64 We need equal pay.

FIGURE 3

Female dominated professions are lower paid across skill levels

Source: Institute for Women’s Policy Research

Ensuring equal pay for women has enormous public support: Our poll found that 90 percent of women on the brink and 73 percent of respondents overall strongly favored addressing the gender wage gap as a way to increase women’s wages.

Enacting the Paycheck Fairness Act addresses the wage gap factors unexplained by occupation, industry, labor force experience, or education. And it would bring us one step closer to ensuring that women can bring home a paycheck equal to their male counterparts.

Source: Table 39 in Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013 Employment and Earnings Online, Annual Average Household Data, February 13, 2013.

Ensuring equal pay for women has enormous public support: Our poll found that 90 percent of women on the brink and 73 percent of respondents overall strongly favored addressing the gender wage gap as a way to increase women’s wages.

The bill would strengthen the Equal Pay Act in several important ways, including:

CONCLUSION

At the beginning of this chapter, we posed the question: How do we put women and their families at the center of our public policymaking? Answering this question requires us to acknowledge that today, two-thirds of U.S. mothers are primary or co-breadwinners, but that too many of our public policies are stuck back in 1964, when most families had a woman at home to be the full-time caregiver.

It’s time to enact 21st-century policies that help 21st-century women manage their care responsibilities and bolster their potential as breadwinners. Doing so would provide greater opportunities for women to join the workforce and help close the persistent gender wage gap—helping millions of families join the middle class and contributing to long-term economic growth for the nation.

Putting women at the center of our policymaking means enacting paid sick days legislation so that people like Elose don’t have to choose between their health and their job. It means expanding affordable, quality pre-K and child care so that more families like Jennifer’s can get back on their feet. It means modernizing our policies to provide access to paid family leave, so that people don’t have to choose between taking a few weeks to welcome a newborn child or earning enough income to provide economic security for their new family. And it means boosting wages for breadwinners through an increase in the minimum wage, modernizing public work supports, giving future college students better information about educational investments, and providing tools for pay equity.

These solutions would help millions of working women achieve financial security. At the same time, the solutions deliver long-term economic benefits and help strengthen our economy.

There are 42 million Eloses and Jennifers—women on the brink, and another 28 million children who depend on them. There is clear evidence that the public solutions outlined in this chapter would help millions of women and families push back, and in the process enhance U.S. economic growth and competitiveness.

It’s not a question of if we know how to do it. It’s a question of whether or not we have the political will to get it done.

The United States is the only industrialized nation in the world without paid sick leave.