Failure to Adapt to Changing Families Leaves Women Economically Vulnerable

By Anna Greenberg, David Walker, Alex Lundry, and Alicia Downs

Americans recognize and applaud the growing role of women in our economy. Seventy-one percent of Americans—including an equal number of men and women—describe women’s financial contribution to our national economy as essential; an insignificant 4 percent do not believe women play an essential role. Demographic trends prove Americans right in their assessment of women’s economic contribution; women now make up nearly half of the employed population, and the majority of all people employed in management and professional occupations are women.1 And a majority of mothers—especially single mothers—are working mothers. As women continue to outpace men in educational attainment and entry into the fastest-growing occupations, the economic power of women will continue to rise.

Many of these changes have been chronicled in past research by The Shriver Report. The research in A Woman’s Nation Changes Everything, published in 2009, documented in detail the many changes in our economy and our society from the massive influx of women into the American workforce over the past few decades. The country—men and women alike—accepted and even celebrated the rising financial role of women. Domestically, both men and women embraced the growing trend of men taking on household and child care duties, even if the reality of men’s contribution to household labor often fell short of the ideal. In that report, we declared, “the battle of the sexes is over.”

This report addresses the essential role women play in our economy, but also explores a different kind of change—one the country does not always celebrate but, rather, recognizes the need to respond to: the evolution of the American family and the consequent change in demands on American women. This report makes plain that the failure of government and business to adapt to these changes creates significant and unnecessary financial burdens for many women and diminishes the overall contribution women can make to our economy and our nation.

Currently, more than half of the children born to mothers under age 30 are born to single mothers. A significant proportion of these women are women on the brink, or women just getting by. Other women may have husbands or partners but do not have jobs that give them the flexibility to fulfill both financial and family priorities and do not have the family income to give them the choice of surrendering one income. Other women do not have the education or training to adjust to an evolving, information-age economy. For many of these women, the current economy just does not seem to have a place for people like them. Many believe that no matter how hard they work, they cannot get ahead, even if they make all the right choices.

And yet, paradoxically, their story is not one of victimhood. Despite their many challenges, most financially vulnerable women—blue-collar women, single mothers, low-income women, women of color—say they are optimistic about their economic future and confident in their own ability to make the changes they need to turn their lives around. In policy terms, they are not looking for handouts but for specific accommodations that allow them to fulfill their role as both primary caregiver and primary breadwinner. They see a disconnect between their own ability to move ahead, which is quite high, and the ability of the current economic structure to evolve with the changing family dynamics in this country, which is often frustratingly low in their eyes.

The country itself is willing to adapt. While the nation does not absolve single parents of primary responsibility for their families, a convincing majority of Americans believe women raising children on their own face tremendous challenges and government, employers, and communities should help them out financially. Nearly two-thirds of Americans believe the government should set a goal of helping society adapt to the reality of single-parent families.

Policies in both the public sector and private sector that explicitly seek to accommodate modern families where women are the primary or significant breadwinner—paid sick leave, flexible hours, pay equity, job security for pregnant women, college assistance for single mothers—find overwhelming support in the country. What is most striking in this age of partisan gridlock is that Democrats and Republicans support these policies with near-equal enthusiasm.

A Woman’s Nation Foundation, in partnership with the Center for American Progress and generously supported by the AARP, commissioned a large national survey to explore Americans’ attitudes toward women and the economy, marriage, regrets in life that affect financial status, and policies aimed at generating more economic mobility for financially vulnerable women. The poll explored the attitudes of financially vulnerable women, including their job satisfaction, their personal ambition, and their attitudes toward divorce, but also measures of how these women live their lives—whether they have children, their marital status, the level of support they receive from their child’s other parent, whether their parents were divorced, things in their lives that create stress, and their goals in life, as well as their regrets.

Working with Republican pollsters Alex Lundry and Alicia Downs of TargetPoint Consulting, the Democratic polling firm Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research interviewed 3,500 adults across the country to help write a statistical narrative of the women who rarely lead network news stories or dominate celebrity gossip in social network surveys but are an essential part of our nation’s fabric and economy.

Polling methodology

Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research and TargetPoint Consulting, in collaboration with the Center for American Progress and The Shriver Report, contacted 3,500 adults by landline and mobile telephone from August 21 to September 11, 2013. Telephone numbers were chosen randomly and in accordance with random digit dialing, or RDD, methodology. The survey included oversamples of 250 African American (574 in the total sample) and 250 Hispanic adults (501 in the total sample) to allow for more detailed subgroup analysis. The sample was adjusted to census proportions of sex, race or ethnicity, age, and national region.

The margin of sampling error for adults is plus-or-minus 1.7 points. For smaller subgroups, the margin of error may be higher. Survey results may also be affected by factors such as question wording and the order in which questions were asked. The interviews were conducted in English and Spanish.

A pragmatic perspective on single mothers

As stated earlier, more than half of the children born to mothers under the age of 30 are born to single mothers. Dating back to the Moynihan Report in 1965,2 a great deal of social science research exploring the rise of single-parent households focused on the bad outcomes disproportionately affecting these families. The high number of single mothers among women on the brink in this research further attests to the high financial costs of raising children in a single-parent household. (See Ann O’Leary’s chapter, “Marriage, Motherhood, and Men.”)

But Americans bring a practical perspective to this issue. Nearly 60 percent of Americans agree that “women raising children on their own face tremendous challenges and government, employers and communities should help them out financially.” This more tolerant attitude grows sharply among younger people (77 percent agree). At the same time, a slim majority believe single parents should be held “completely responsible” for the children they bring into this world. All told, 53 percent agree with the statement, “If women have children without being married, they need to take complete financial responsibility for their children.” Interestingly, women (56 percent) are somewhat more likely to agree than men (51 percent).

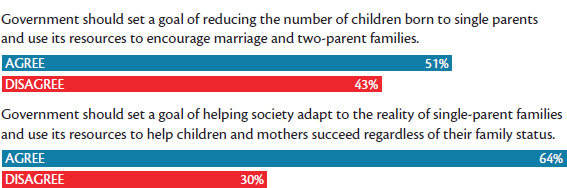

Moreover, the public greatly prefers a government policy of “helping society adapt to the reality of single-parent families” (64 percent) over a goal of “reducing the number of children born to single parents and encouraging two-parent households” (just 51 percent). Among economically vulnerable women—including, not surprisingly, single mothers—this number grows even higher. While not suspending judgment, at least not entirely, the public wants to accommodate the reality of the new American family.

This research did not ask the respondents to assess the morality of single parenthood; rather, it asked respondents to address how to best respond to the reality of the new American family. And their approach is pragmatic. While they do not absolve single mothers of the primary responsibility for their children, they also task the broader society with the obligation of doing what it can to help these mothers and their children succeed.

FIGURE 1

Pragmatic perspective on single mothers

Currently, over half the children who are born to mothers under the age of 30 are born to single mothers. With this in mind, please tell me if you agree or disagree with the following statements.

Our economy does not work for economically vulnerable women

In no small measure because policymakers and businesses have failed to adapt to changes in the American family, the current economy simply does not work for many women in our country. Single-parent households rely on one income. Even for married families, the debate between “stay-at-home moms” and “working moms” is irrelevant, as they do not have the financial flexibility to choose between one or two incomes. But women in these families often do not have flexible work schedules and lack the appropriate education or training to find more accommodating jobs.

In the survey, many of these financially vulnerable women believe—unlike other Americans—that the harder they work, the further they fall behind. They suffer disproportionate levels of stress, mostly related to bills and expenses. It is not that these women—and economically vulnerable men—do not want to work or succeed. It is that the current economic structure does not afford them the opportunity.

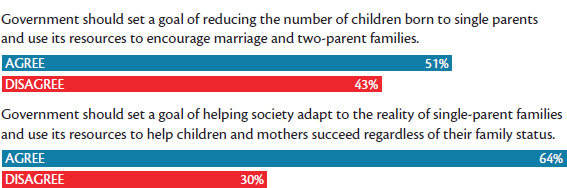

Slightly more than one in four Americans (28 percent) believe the statement “the harder I work, the more I fall behind” accurately describes them. Women are significantly more likely to agree than men (33 percent and 24 percent, respectively), but this sentiment jumps to 48 percent among single mothers and 54 percent among lower-income women.

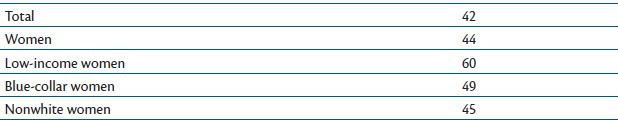

TABLE 1

Our economy does not work for economically vulnerable women

Please tell me if this statement describes you very well, describes you somewhat well, does not describe you well or does not describe you at all.

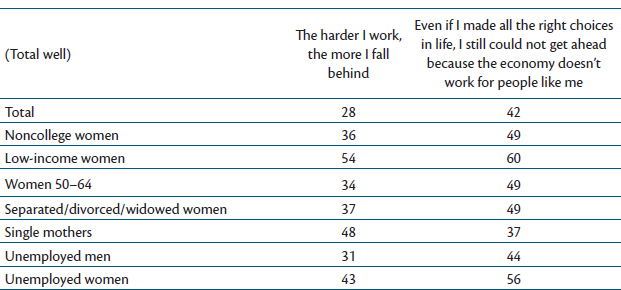

FIGURE 2

Higher levels of stress

On a scale of 0 to 10, please rate the overall level of stress you are feeling these days. A 10 would mean you feel a lot of stress. A zero would mean you do not feel much stress overall. A five would be an in-between response. You may choose any number between 0 and 10.

Forty-two percent of Americans agree that the statement “Even if I made all the right choices in life, I could still not get ahead because the economy does not work for people like me” describes them well. Women are more likely to agree than men, but the numbers really take off among lower-income and other financially vulnerable women. The percentages in figure 2 depict the portion of men/women/low-income women/single mothers who report that they are facing “extreme stress” defined as 8 or higher.

Not surprisingly, economically vulnerable people struggle with more stress than other Americans. In this survey, we asked respondents to rate their levels of stress on a 10-point scale. Overall, 46 percent of Americans rate their level of stress a 6 or higher. Women overall face more extreme stress (8 or higher) than men. Single moms, particularly those with no partner, are among the most stressed (10), as are lower-income women.

Thirty-six percent of lower-income women suffer extreme stress (8 or higher), compared to 23 percent of the population as a whole and 27 percent of all women.

Women living on the brink of financial instability suffer from disproportionate levels of stress. {MELISSA FARLOW}

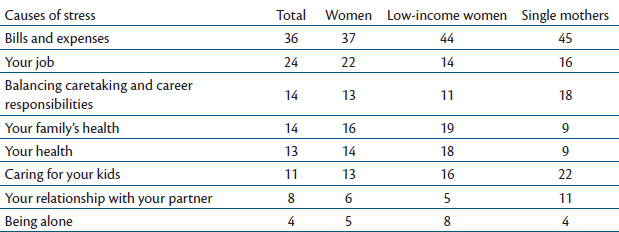

Economically vulnerable women also differ somewhat in the kinds of stress they face or at least in the scale. The leading stress point for all Americans is bills and expenses (36 percent), which climbs to 44 percent among women earning less than $60,000. The second-leading stressor nationally is “your job,” at 24 percent overall. Fourteen percent peg balancing caretaking and career responsibilities as a key source of stress, and 11 percent identify caring for kids.

Balancing career and family and caring for kids loom particularly large, not surprisingly, for single mothers. Forty percent of single moms identify either “balancing caretaking and career responsibilities” (18 percent) or caring for kids (22 percent) as a leading cause of stress in their lives.

TABLE 2

Stressed-out single moms

While notable in scale and scope, few of the challenges facing these women are surprising. What is surprising is that despite these many obstacles, these women are no less optimistic, determined, and satisfied with their lives than other segments of the population. This may seem like a contradiction, but it is not. Although most Americans are optimistic about their own future and generally happy when asked about it in a public opinion survey, these results reveal something deeper about the specific population of vulnerable women.

When we ask these women about things they can control, specifically their own ability to work hard and change their lives, they react with optimism and resilience. However, when we ask about things they cannot control, such as the current economic structure in the country, this optimism fades substantially. This is how the same woman on a survey can state she believes she has what it takes to improve herself (self-directed) while at the same time insist that the economy does not work for people like her (outwardly directed).

Economically vulnerable women remain resilient and optimistic

Americans believe in themselves. Even with the backdrop of the Great Recession and a glacial recovery, they remain generally happy and satisfied with their lives. Americans believe in their own ability to work hard, succeed, and make the changes necessary to improve their lives. This powerful American optimism and resilience runs just as strongly among economically vulnerable women as anyone else. Financial challenges aside, they are generally happy and satisfied with their lives. More importantly, they also believe they can change their lives. In their resilience, they build informal networks of people to help sustain them, even while formal networks of businesses and governments often fail them.

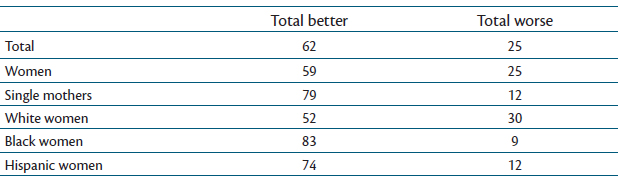

Nationally, nearly two-thirds (62 percent) of Americans believe their financial situation will get better over the next five years; 23 percent believe it will get much better. Women (59 percent believe it will get better) are only marginally less optimistic than men (65 percent); these numbers hold for noncollege women (58 percent) and lower-income women (62 percent) and increase to 79 percent among single mothers. Women of color are also disproportionately optimistic about the next five years (83 percent among African American women; 74 percent among Hispanic women).

TABLE 3

Personal financial optimism

Regardless of your financial situation right now, do you believe your financial situation will get better or get worse over the next five years?

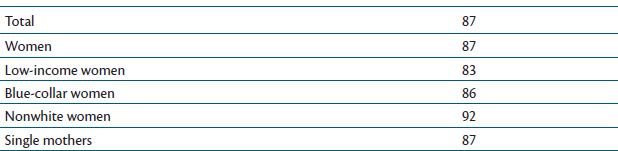

Nine in 10 Americans describe themselves as “generally happy and satisfied with their lives.” Although the number is somewhat lower, an overwhelming majority (87 percent) of lower-income women as well as single moms (79 percent) also describe themselves as happy and satisfied with their lives. Why is it that financially struggling women on the one hand believe that the harder they work, the more they fall behind and that the economy does not work for them and, on the other hand, describe themselves as generally happy and satisfied? They are more confident in their own abilities to change their financial situation compared to their confidence in what the government or employers can do for them.

Even more striking, 87 percent of Americans agree with the statement, “I believe I have the ability to make significant changes in my life to make my life better.” An inspiring 87 percent of single moms believe the same thing, as do 95 percent of African American women and 92 percent of Hispanic women. Millennial women are nearly unanimous in the belief of their own ability to change their lives for the better (98 percent).

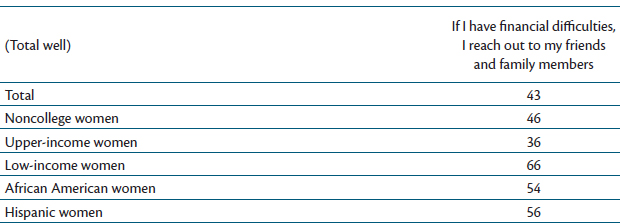

Some of these women believe they have economic resources that other women do not see in their lives. Economically vulnerable women are significantly more likely to believe the statement “If I have financial difficulties, I reach out to my friends and family members” than respondents overall (just 43 percent overall, 46 percent among noncollege women, 66 percent among lower-income women, 54 percent among single moms). This is particularly true in communities of color (54 percent among African American women, 56 percent among Hispanic women). In contrast, only 36 percent of upper-income women (earning more than $100,000 a year) believe they can reach out to family and friends if they have financial difficulties.

Kristy Richardson and her husband, Shawn, play with their sons in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. {MELISSA FARLOW}

TABLE 4

Personal financial resilience

Now I am going to read you a series of statements. For each one I read, please tell me if this statement describes you very well, describes you somewhat well, does not describe you well or does not describe you at all.

These women are survivors. When in trouble financially, they reach out to their informal networks (friends and family), because sometimes more formal networks (business and government) fail them. Despite the huge challenges outlined in this chapter and in the research in this report, these women believe in themselves, their work ethic, and their ability to change—just like other Americans. But they do not necessarily believe—or recognize—the ability of the current economic structure to accommodate people like them. Financially vulnerable women see a divide between their own ambition and ability and the current economic reality they face.

TABLE 5

Financially vulnerable women believe in themselves

Financially vulnerable women believe in themselves …

I believe I have the ability to make significant changes in my life to make my life better.

… but do not believe the economy works for people like them

Even if I made all the right choices in life, I still could not get ahead because the economy doesn’t work for people like me.

Looking back: The regrets of economically vulnerable women

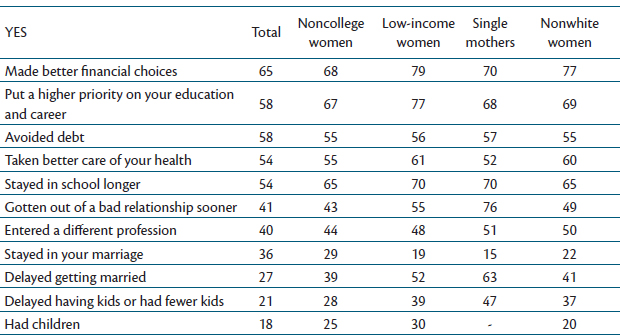

Few economically vulnerable women are doing what they thought they would do when they were growing up. This is an outcome they share with all Americans (only 33 percent of whom are doing what they thought they would do). Where they part with the rest of the country—and from economically vulnerable men—is their perspective on having children.

The financial burdens of children on one’s ambition are disproportionately borne by women. Overall, 15 percent of women identify having children too early as the reason they did not fulfill the ambitions of their youth, compared to only 1 percent of men. Sixteen percent of noncollege women identify having children too early as the reason they did not fulfill the ambitions of their youth, also compared to 1 percent of noncollege men. Not surprisingly, single mothers are the most likely (24 percent) on an open-ended question to identify children as the reason for not doing what they thought they would be doing when they were growing up. The economic consequences of early or unintended pregnancy are profoundly different for men and women.

However, it is critical to recognize that one immediate consequence of an unplanned pregnancy for many economically vulnerable women is a delay—often a lifetime “delay”—in educational attainment. Indeed, a significant number of financially vulnerable women regret having children or at least the timing of the children. Indeed, given the difficulty of sharing such a confession in a phone survey, the number here is probably understated. But the larger regret for financially vulnerable women is, indeed more so than anything else, leaving school early, which distinguishes these women from the rest of the country.

TABLE 6

Variety of regrets

Thinking specifically in terms of your own life up to this point, please tell me if you could do it all over again, whether you would do the following

Where men and women part ways, particularly among financially vulnerable populations, is on the issue of marriage and divorce.

Interestingly, most divorced women do not regret their decision to end their marriages. Only 28 percent of divorced women wish that they had stayed married, compared to 47 percent of divorced men. Only 19 percent of lower-income women who have been divorced wish they had stayed in their marriage, compared to 53 percent of divorced lower-income men. Lower-income women are also significantly more likely to regret not delaying marriage (52 percent) than lower-income men (33 percent). Seventy-six percent of single mothers wish they had gotten out of bad relationships sooner.

The challenge seems less about reorienting family life to fit the needs of careers and business and more about changing business models and rules, as well as domestic arrangements, to allow for an evolving family structure.

These women look back on their lives with the clarity of hindsight. Notably, issues of family, pregnancy, early marriage, and divorce certainly play a major role in their current financial vulnerability, specifically in damaging their education and ability to focus on a career. Still, Americans do not necessarily accept this outcome as an inevitable, lifetime consequence of “bad” choices. Americans believe a woman who has a child in her early twenties can still focus on her education and career with a little help—or at least they support policy changes with that explicit goal. As we think through potential public- and private-sector policies that can help economically vulnerable women, the challenge seems less about reorienting family life to fit the needs of careers and business and more about changing business models and rules, as well as domestic arrangements, to allow for an evolving family structure.

What businesses and government can do to help economically vulnerable women

Both the public sector and the private sector can play an important role in improving the lives of economically vulnerable women—and men—in this country. These are people who have the same drive and ambition as other Americans, the same confidence and belief in their ability to work hard and ultimately succeed.

While a minority of economically vulnerable women ascribes their financial struggles to overt discrimination in the workplace, many business practices discriminate against women in their impact. Overall, 69 percent of the public believe women “have a fair shot at the workplace and have the same opportunities to succeed as men” (74 percent among men, 63 percent among women). Views do not change among noncollege women (65 percent) or women of color (67 percent).

These women, however, argue for changes in policy that remediate de facto discrimination and, more specifically, help them accommodate their jobs with the responsibilities of family life that still disproportionately fall on women. Many need such accommodations to move up the economic ladder, such as a bump in pay or pay equity, additional training, laws protecting the rights of workers who get pregnant, and access to child care. As much as anything, the policy agenda of economically marginalized women emphasizes the ways business and government can accommodate diverse family obligations.

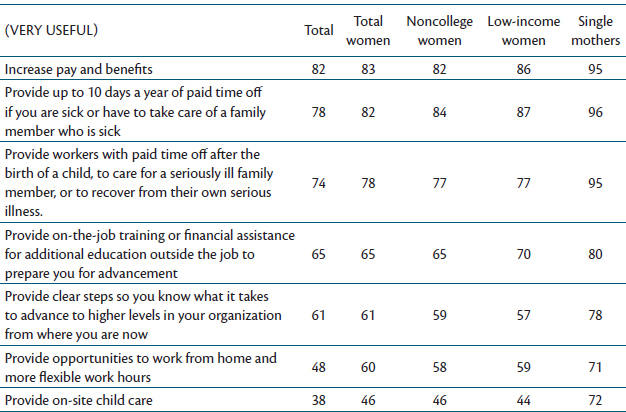

Respondents with full-time or part-time jobs were asked to describe a number of things businesses could do to improve their job as very useful, somewhat useful, not very useful, or not at all useful. Not surprisingly, increasing pay and benefits ranks as the leading response overall. But among lower-income and noncollege women, just as many identify paid sick leave as very useful in their lives. Ninety-six percent of single moms identify paid sick leave as very useful to their lives, compared to 82 percent of all women. These women are also disproportionately interested in on-site child care and flexible work hours.

TABLE 7

What businesses can do

Thinking specifically about your life, after each one I read, please tell if this would be very useful to you, somewhat useful to you, not very useful to you, or not at all useful to you.

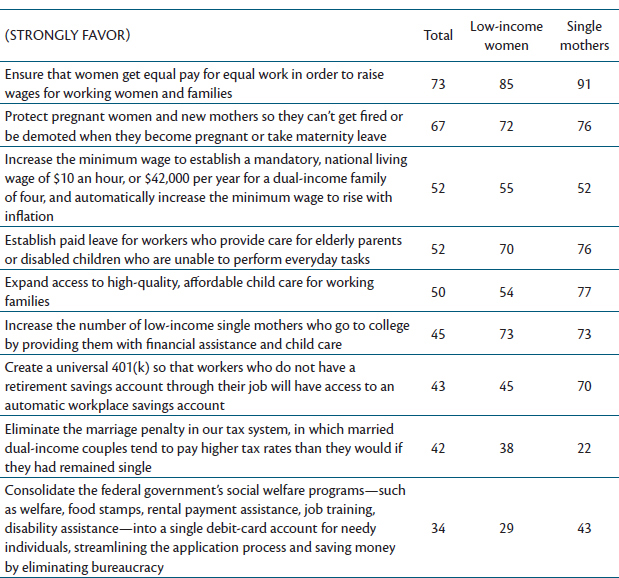

Government policy needs to change as well. As with changes in the business world, economically vulnerable women focus largely on accommodations for families. Pay equity is the leading item, critical for single-mother households. Seventy-two percent of lower-income women strongly favor rights protecting workers who get pregnant. Lower-income women are 18 percentage points more likely to strongly favor paid leave for workers who provide care for elderly parents or disabled children and 28 points more likely to strongly favor expanding college opportunities for single moms. Understandably, single moms are much more likely (27 points) to strongly favor expanding access to high-quality, affordable child care.

TABLE 8

What policymakers can do (part 1)

Now I am going to read you some steps the government could take to improve economic security for people in this country. For each one I read, please tell me if you strongly favor this proposal, somewhat favor this proposal, somewhat oppose this proposal, or strongly oppose this proposal.

Though still popular, the one policy explicitly geared toward married families notably falls toward the bottom of the list: 42 percent strongly favor (63 percent total favor) eliminating the marriage penalty in our tax system.

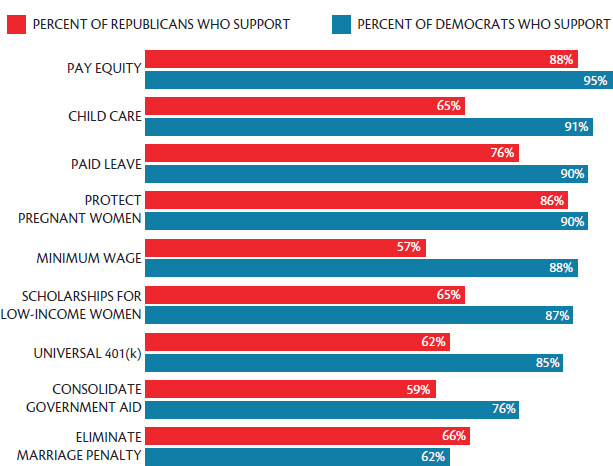

Partisan gridlock now grips Washington, as every budget deadline or debt ceiling bill becomes an occasion for government showdown and shutdown. But when it comes to policy ideas for helping economically vulnerable women, the public demonstrates impressive bipartisan consensus. Ninety-five percent of Democrats support pay equity, as do 88 percent of Republicans. Ninety percent of Democrats support protecting the rights of pregnant workers, as do 86 percent of Republicans.

FIGURE 3

What policymakers can do (part 2)

Conclusion

The country is changing.

We have moved from a dominant model of single-income, two-parent households to dual-income, two-parent households to an increasing number of single-parent, single-income households. These changes have profoundly impacted the broader American economy but also present significant financial challenges for women. Economically vulnerable women themselves recognize and often regret some of the decisions they made that have inhibited their financial potential. Even as women as a whole have captured a growing role in the American economy, this economy has left too many women behind. In the eyes of these women, this outcome is less about overt gender discrimination in the workplace than about the failure to accommodate changing family structures.

Julie Kaas, a single mother and preschool teacher, rides her motorcycle down the road to her home in Washington. {BARBARA KINNEY}

Importantly, the country itself recognizes this challenge. While the country does not absolve women—or men, for that matter—of the primary responsibility for raising their own children, a convincing majority of Americans believe government and society have a role to play in helping these new families. Even more convincing, majorities of Democrats and Republicans support a suite of policy changes in both the private sector and public sector to accommodate these families and give these women the space they need to improve their economic standing.

The changing trends in the American family will continue. The nation has already made the choice to adapt to these changes, as witnessed by the survey results above and the broad embrace of policies to help financially vulnerable women. The question is whether policymakers in the public sector and private sector will make the same choice. Doing so will ensure that economically vulnerable women have a fair shot to reach their full potential, and in the process strengthen our economy and our country.