In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau sets out to determine ways of practising life not easily subsumed to dominant tenets of the capitalist work ethic, with its practices of both surveillance and discipline, already seen as pervasive in the early 1980s. Rather than looking at narrowly revolutionary means of overthrowing capitalism, de Certeau is interested in finding a way to escape without departure—that is, a way of checking out of capital while still inhabiting it. De Certeau writes specifically in response to Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, but de Certeau’s vision is less bleak than the ominous panopticism discussed by his contemporary. De Certeau looks at a variety of specific practices like perruquerie, which he defines as the practice of putting on a metaphorical wig such that one may look like a productive worker, while in fact being the opposite through the misuse of both the time and the place of labour. “La perruque,” writes de Certeau, “is the worker’s own work disguised as the work of his employer”; even more so: when the worker dons la perruque, she disguises herself as a worker while remaining unsubsumed, and potentially, even, unalienated.1 This form of trickery, subversion, and playfulness is of interest here, in that de Certeau sees perruquerie as a means of escaping, subverting, and undermining systems of domination without having to propose a revolutionary context—or to accept a reformist vision. We might think of recent statistics concerning how most workers feel: David Harvey writes that, in a recent US poll, “about 70 percent of full-time workers either hated going to work or had mentally checked out and become, in effect, saboteurs.”2 The role of sabotage, perruquerie, and the disregard of the role of the labourer are, in a number of analyses, key indices of the failure of today’s society.

Within this context, I am interested in an important distinction that de Certeau proposes between strategies and tactics—a distinction that we might make in other ways (indeed, different political movements have done so; Charles Bernstein has previously used the distinction in the context of poetry).3 I focus on de Certeau’s articulation because I think that it may prove useful for thinking about elements of contemporary poetics and what I am calling a poetics of neoliberalism in this essay. De Certeau defines a strategy as any act, gesture, or maneuver that acts in relation to something else. A strategy is exterior to the environment in which it exists, and a strategy enunciates the potential to oppose this environment and thus to change it, if not to overthrow it. For de Certeau, strategy is the model upon which politics has been built thus far. His definition of a tactic, on the other hand, looks at everyday enunciations as themselves being political in character. The tactic is something not separate from its environment; the tactic is, rather, something that “belongs to the other” in that the tactic is part of the environment. While seeming to be a smooth element of the existing social situation, the tactic might displace dominance through a seeming participation that slightly shifts the markers.4 The contrast that de Certeau sets up, in effect, is one of capital-P Politics and the politics of the everyday.

My initial response to de Certeau is that participation in systems of dominance always risks providing legitimacy to them, and hence enabling their perpetuation; in that sense, I have been thus far liable to advocate forms of socialist strategy that actively propose alternative forms that would, in due course, themselves likely become hegemonic if successful (in the sense discussed by Laclau and Mouffe).5 Readers are likely to have different takes on the issue, as we bump into the familiar, rocky dichotomy of reform versus revolution, upon which so many leftist projects founder. However, if we can translate strategies and tactics into the framework of contemporary poetics, then we might see different forms of potential at work when they operate alongside one another.

The neoliberal moment that we are inhabiting calls for a variety of approaches, from the strategic through to the tactical, as we are confronted with biopolitical governance at all scales. Many people have written about the rise of neoliberalism, and I do not want to overstate my own version of the case, but I do want to note that the contemporary moment necessitates a particular sort of response, as many poets and activists are doing. In this context, we can and should give different accounts of neoliberalism, as its critics do, from David Harvey’s Brief History of Neoliberalism to Foucault’s lectures, especially those published in The Birth of Biopolitics.6 The aspect of neoliberalism in which I am interested here concerns the ways in which the marketization of the human since at least the era of Thatcher and Reagan has continually reasserted the priority of normative bodies and practices. That is, I view as oppressive all the ways that neoliberalism enforces the labour of the body, demanding that the body must be as economically productive as possible (a condition that disciplines in the humanities have sought to challenge). William Connolly argues that “neoliberalism is a form of biopolitics that seeks to produce a nation of regular individuals, even as its proponents often act as if they are merely describing processes that are automatic and individual behavior that is free.”7 The normalized body, the “regular individual,” can be normalized only to a certain extent, however; on the obverse side of this process, we find bodies that cannot be normalized in order to be economically productive (or even equally productive). These are the people whom Naomi Klein (in her book This Changes Everything) identifies as sacrifices to capitalism, those who are disposable because they are less economically productive.8 We live in an era in which walls go up in order to keep people from moving across borders, while borders diminish for capital and the wealthy. Wendy Brown’s study of the contemporary practice of wall-building situates such barriers in precisely such a neoliberal frame; she argues that walls “produce a collective ethos and subjectivity that is defensive, parochial, nationalistic, and militarized.”9 This ethos and subjectivity is that of the inside; from the outside perspective, we might take a cue from Elizabeth Povinelli, who suggests that “any form of life that is not organized on the basis of market values is characterized as a potential security risk” under neoliberal modes of governance.10 This outline is just a quick sketch of some of the academic terrain at the moment; a great deal of critique is focusing precisely on the reassertion of the economically productive body in models of governance and being.

We might note the ways in which neoliberalism has done more than just come home to roost. We can identify the myriad ways in which neoliberalism affects poetics. We could start with the material diminution of funding for the arts in general, moving from there to attacks on education. Or we could think more abstractly about the ways in which poetics today are harnessed: poets are asked, either implicitly or explicitly, to become drivers of economic growth and development. Following from Richard Florida’s examination of the so-called creative class,11 poetry is all around us: projected on the side of the Calgary tower, in our classrooms, at the opening of city council meetings, and in gala media events that seek to demonstrate to us that Canada does, indeed, have an elite literary class. As most of us know, however, poets are not economically productive. Any poets who read this piece could compare the public harnessing and celebration of poetry to their last cheques for an honorarium. But this fact does not mean that poets are unproductive in economic terms. Neoliberalism asks that poets not only make a buck—and who does not want to be able to pay for the essentials of living?—but also that this buck be a part of some sort of Bourdieu-esque accrual of cultural capital. The creative class, of which poets are asked to be a part, labours to build the creative city, each city vying to out-create the rest in the service of fostering vibrant markets of all sorts.

Questions that follow from this normalization of the poet—her career, her trajectory, her reception in the market—have to do with the dissenting voice: What of the poet who does not seek to be marshalled in the service of neoliberal capitalism? How will she be disciplined for non-compliance? (Impoverishment, most likely, for a start.) And, in this context, how can a poet dissent and continue to work? Can the poet have the line “fuck capitalism” in her work and still have it be displayed as a bus ad?

With such questions in mind, I would like to return to the analysis of tactics and strategies offered to us by de Certeau. What might a poetics of neoliberalism look like? I say a poetics “of” neoliberalism—neither a poetics “for” neoliberalism (which we can see all around us, not just within poetry itself), nor a poetics “against” neoliberalism (for I am concerned with the dynamic interplay of terms here). My terminology also draws upon a key antecedent to this essay, Linda Hutcheon’s book A Poetics of Postmodernism from 1988, as well as her book The Politics of Postmodernism from 1989.12 These works are key because they now signal a temporal disjunction: by the second edition of The Politics of Postmodernism in 2002, Hutcheon declares postmodernism to be “over.”13 It is not clear what comes in its wake aesthetically—because the postmodern is (or was), after all, an aesthetics—but, politically, the neoliberal moment certainly vies for the title of today’s dominant economic order. Hutcheon’s work also signals a disjunction with this essay in that her “poetics” focuses, in fact, mostly on fiction,14 as does her other book, The Canadian Postmodern.15 Her focus on fiction has been perceived as an oversight that critics—including one of the editors of this present volume—have noted.16 My thinking for a poetics of neoliberalism, however, does seek to pick up on Hutcheon’s focus on parody, because a gesture like la perruque seems to be, precisely, one way to undermine parodically the rigours of capitalism. I would hazard, however, that the forms of parody, witnessed by us in the context of neoliberalism, may be based much less on irony than the postmodern parody described by Hutcheon.

This essay works by offering a contrast between two writers—Jeff Derksen and Derek Beaulieu—both of whom we might at times identify as, in the first case, strategic, and, in the second case, tactical. I then turn to the work of Rachel Zolf and others so as to suggest that a poetics of neoliberalism can work between tactics and strategies, shifting the terms of engagement, marshalling the practices of everyday life in order to invoke what Elizabeth Povinelli calls one of the “spaces of otherwise.”17 My interest is in pushing such spaces in order to find a poetics of possibility in the context of neoliberal governance.

Jeff Derksen’s The Vestiges is one place to begin looking for a poetics that responds to neoliberalism. Derksen wonders explicitly in the “Note on the Poems” at the end of the book: “How would the writing of the poem position me in relation to the language and images of neoliberalism?”18 The volume is a combination of serial, open-form poetics and procedural, conceptual pieces, which draw on, for instance, every instance of the first-person pronoun in Marx’s Capital or every parenthetical statement from Althusser’s essay “Ideological State Apparatus.” As such, the book re-evaluates leftist thinking through deliberately late modern forms, doing so as a way of continuing the project of critique and creative research that has already been a hallmark of Derksen’s work.

While a reading of Derksen’s book could take us in many directions, I would like to focus on the opening, titular piece, “The Vestiges,” in order to examine a poetic iteration of a strategic response to neoliberalism, one that seeks to examine it from both the inside and from an exterior vantage-point. “The Vestiges,” in other words, seeks to intervene in the politics of neoliberalism, to approach an explicit critique from within a poetic form. The poem opens with lines that establish the setting, phrased in Derksen’s typically brief, allusive manner:

Linear tankers lie

on the harbour’s horizon.

The speed of globalization.

“Community-based

crystal-meth focus groups.”

Jog by.19

The scenery appears to be recognizably that of Vancouver, and the poem quickly moves to satirize the commodification of sightlines via the commerce of real estate. An ironic, not-quite-detached tone takes on the ways in which this is a space where

Soft power over borders

holds or hoards bodies

when borders are hardened

today, the miracle

of social space

refracting “sheer life”

gold, growth industries

public-private partnerships

“bare / life”

that’s legislation over flesh.20

While elusive (and allusive) in its phrasing, the critique turns from Vancouver—and the urban in general—as a commoditized space, pivoting toward an investigation into the ways in which the body itself is commoditized, controlled, bought and sold, reduced to forms of bare life. “The Dirty Wars overturned time / and collapsed space!” we are told: “And bodies.”21 We live in a world in which, in other words, “We don’t negotiate with / workers or terrorists post-Thatcher”;22 in fact, negotiations with power are foreclosed: workers and terrorists are equated as the enemy in a manner that might remind us of how the notion of terror has been expanded so radically since September 11 that the Conservative government’s draft version of Bill C51 was able to suggest that any activity that may interfere with economic productivity could be construed as a security threat (such as, say, peaceful protest).23 Dissidents, workers, and terrorists are elided, are as one, are as the bodies that lie outside of the realm of power.

The relentless processes of commoditization turn inward on the body. How the body turns in on itself prompts a reflection that turns as well toward the lyric voice:

I don’t have a hard heart

but capital has grizzled

it up

that and

other crap

crouched behind the monument

to the fishing industry24

The circumstances are dire for the embodied self: readers are told to “Expect / the exception today” as the state seeks to formalize, to commodify, its relationship to our bodies.25 Capital’s lengthy relationship with the structures of Westphalian sovereignty is summoned into a query about the ways in which the body is differentiated, interpellated, and subjugated.

In this context, there is little need for nostalgia for a purer or simpler time. Instead, the container ships on the horizon return to the poem to remind us that “Each beaded seam / of those ships / was welded / somewhere, but not here.”26 We might think not only of construction, but also of the disposable nature of all human things, witnessed in the case of tanker ships in Edward Burtynsky’s monumental photographs of ship breakers, the salvagers in Bangladesh and India, all of whom dismantle these ships when the vessels are no longer serviceable.27 Capital makes and remakes itself, exporting its exploitation from the metropole to marginal territories; the links between ships, capital, colonialism, and the bodies of the subjugated are invoked in the repeated imagery of the tanker ships that link directly back to the European vessels that landed in North America during colonization. In this context, Derksen wonders:

Why lament capital

the vestiges of which

are not material, no wooden

brain could make me dance to that.

Why lament surplus

the vestiges of which

have become immaterial

even to its makers.28

The concept of “lament” in these lines is open: on the one hand, we might lament earlier visions of capital, such as the common lament of the loss of small, mom-and-pop forms of consumerism when Walmart arrives in town. We might also ask why we would lament something that is immaterial: capital itself is not material, so why would we weep for it? Particularly given that surplus has become utterly immaterial—no longer connected to the forms of surplus capital that Marx analyzes as being in need of deposit somewhere, leading to new ravages, with their direct and indirect exploitations. We are, rather, dealing with the vestiges of a system analyzed by Marx, one that has transformed so as to be no longer recognizable in precisely the terms that he and his contemporaries used. Finally, we might wonder why we would lament capital or surplus, when they are, rather, things that we may wish to divest ourselves of in order to rethink how social relations might be conceived. Why lament capital when we wish to speed its demise?

The open-endedness of this query provides the strength of a poetic form of research. The critique of capital is embedded within the line, which directly and deliberately addresses neoliberalism. At the same time, the strategy that Derksen pursues in “The Vestiges” mixes wry observation and questioning in order to expose the violence and foolishness of a system founded upon endless growth and perpetual exploitation—a system that has solved neither the contradictions analyzed by Marx nor the flaw in the system observed by Alan Greenspan.29 The process of exposing these faultlines through poetics can, in this sense, constitute a strategy for addressing neoliberalism.

Derek Beaulieu’s Kern might seem at first glance to be a surprising juxtaposition to Derksen’s Vestiges. I would like to argue, however, that Kern constitutes precisely a tactical address to the problems of neoliberalism—problems that Derksen addresses strategically. In several places, Beaulieu has argued that contemporary poetry, in order to maintain its relevance or audience, needs to resemble the logic of advertising or the neat look of a logo like the Nike “swoosh” or the golden arches. This statement is no naive move towards succumbing to the logic of the market, either; rather, Beaulieu has explicitly stated on several occasions that his visual poetry thinks through the possibilities of subverting the push toward marketizable forms of reading. Resisting legibility and the written word, in other words, is a means of pushing back at capital (we might think of any number of ways in which capital seeks to render the body legible and read such a notion of illegiblity as a strikingly important form of resistance).

Recently, Beaulieu’s work has in fact become a form of advertising, for Calgary’s WordFest, the city’s annual celebration of the literary arts. On six large outdoor panel advertisements, displayed in the fall of 2014, a statement from Beaulieu accompanied one of his visual pieces. The statement read: “Poetry should be as fleeting as the traffic, as vital as a street sign,” and the statement appeared around Calgary’s major thoroughfares. The statement reveals a tactical desire on Beaulieu’s part: the fleeting nature of the poem that he extols might fit in with the visual speed by which we recognize the swoosh or the stylized Apple logo and move on to other things (while less than consciously absorbing these advertising images). At the same time, the fact that this “fleeting” poem is “vital” should signal to us that it is pushing our minds in another direction, interrupting our path and urging us in new directions, as traffic signs do. The visual poem is a stop sign in the path of capital. A tactical poetics of neoliberalism, as such, may be disguised as a traffic sign, providing directions to an otherwise or an elsewhere in the first instance, and highlighting the ravages of contemporary capital in the second.

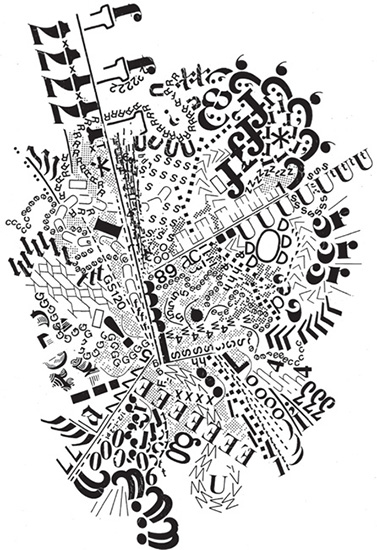

FIGURE 14 Derek Beaulieu’s “Untitled,” from Kern (Les Figues Press, 2014).

With this tactic in mind, I read Beaulieu’s Kern. The title, of course, comes from typography, referring to the process of adjusting the spacing between letters so as to improve their visual aspect. The title is apposite; Kern is a book that is particularly interested in adjusting the relationships between letters in order to rework their aspect. It is a book of visual pieces, in other words, working from the Letraset methods that Beaulieu has developed in his work. None of the pieces are titled; the book thus reads as a continuous flow with one piece per unpaginated page. The pieces vary, including complex compositions such as the the one in Figure 14. This piece works across a series of typefaces in order to provoke an admixture of linearity and chaos through juxtaposition. Meanings are not immediate; they may be drawn out or extrapolated, as the editors of a recent CanLit Guide, “Poetic Visuality and Experimentation,” have done to a piece of similar weight and density by Beaulieu.30 Clearly, a different series of strategies is needed in order to “read” this piece in any sense; its role in interrupting the expected container of the poem-as-such can, however, be readily understood by viewers.

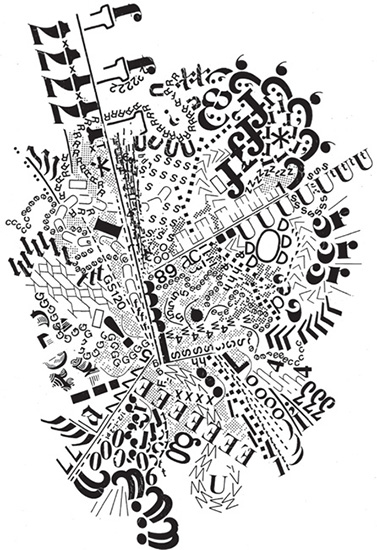

FIGURE 15 Derek Beaulieu’s “Untitled,” from Kern (Les Figues Press, 2014).

At perhaps the other end of the work in Kern is a series of seemingly simple pieces. These deploy or repeat graphemes, letters, or types, as in the Figure 15. This piece looks, indeed, much like what Beaulieu describes in the author’s note at the back of the book: it is similar to what one might see as a sign in an airport, but, rather than “leading the reader to the toilet,” the directions are “spurious if not totally useless.” Beaulieu describes Kern as being “logos for the corporate sponsors of Jorge Luis Borges’s Library of Babel,” signs and images for meanings that remain “just beyond reach.”31 They signal, in other words, meanings that the biopolitics of the present foreclose, providing indices of places, spaces, and things, all of which are currently impossible. By inhabiting a plane similar to that of advertising, Kern adopts a tactic that exists within the corporate-speak of neoliberalism, yet signals the rupture or the breakage of precisely this system that the poem inhabits.

What I have done so far is to set up two recent poetic experiments in opposition to one another in order to contemplate what strategies and tactics a poetics might adopt in order to address neoliberalism. Challenges emerge in this opposition, as they should. Derksen’s practice in much of The Vestiges pushes back against my argument, since the book is not automatically an act of social change or revolution: an outright strategy to oppose neoliberalism might be, rather, not to write poems, but to get to the barricades. Or to abandon the market logic of book production. The poems themselves, particularly those that move in procedural directions, are more complex than I have been able to suggest here. Similarly, Beaulieu suggests the ways in which his poetry does not simply inhabit advertising-speak, but offers tactics that move in strategic directions. Nevertheless, I want to hold onto this distinction between tactics and strategies because of the analytic mode that it might provide us.

Thinking beyond these texts, then, I suggest that poetic practices that challenge neoliberal politics of biopolitical governance shuttle between moments of tactics and strategies in order to undermine the facades of corporate logic at their weak points. Such an analysis might push us beyond, for instance, the opposition between conceptual poetry and lyric poetry in Canada—if such a disruption has not already effectively been carried out through the critiques of Sina Queyras in her manifesto “Lyric Conceptualism” and her recent book M x T, where we read of the “war canoe made of conceptual poems.”32 But this analysis might also allow us to read, for instance, Rachel Zolf’s book Janey’s Arcadia at the multiple levels that this text invites. By recasting the documents of early European settler-invaders in the prairie provinces and by setting these documents against a recognition of the violence of the present, particularly the ongoing violence against Indigenous women (a violence that Canada’s conservative government under Stephen Harper dismissively told us was simply an issue of domestic violence),33 Janey’s Arcadia performs a strategic intervention into Canada’s neoliberal moment, an intervention that recognizes the ongoing nature of colonial violence. By subjecting the historical documents of these same settler-invaders to Optical Character Recognition scans (OCR), Zolf’s book inhabits the technologies of capital in order to produce tactically a series of misreadings, all of which have devastating consequences. For instance, in Janey’s Arcadia the word “Indian” in the documents of the settler-invaders is consistently misread by the scanner as “Indign.” Zolf’s textual staging of the OCR misreadings adds a dimension that forces us to recognize how purportedly neutral capitalist technologies are not neutral. Rather, the historical misreadings of European settler-invaders are replicated by the OCR misreadings of these documents. The double misreading further displaces Indigenous people from their traditional territories: not only do settler-invaders misunderstand, displace, and erase Indigenous people from the land; now the technologies developed by their descendants erase their textual traces from the colonial record as well. As a result, we see Zolf reproduce scanned sections from a pamphlet intended to persuade potential settlers to move to the prairies—a pamphlet in which women are asked about their relations with local Indigenous people—and we see the OCR misread responses as “no Indign.4 around here,” “We do not experience any dread of the Indigns,” or “No, Mot any, and live close near an Indignant res-rve.”34 The sign “Indign” in Zolf’s book reproduces, while it displaces, the colonial discourse of the “Indian”; preserving the OCR glitches, squelches, and faults reanimates exactly those same glitches and faults in the discourse of the settler-invaders. As an intervention into the contemporary biopolitics of the nation-state, Janey’s Arcadia gives us strategies and tactics for undermining the colonial nature of a neoliberalizing Canada.

My poetics of neoliberalism (one that shifts between strategies and tactics for reworking the possibilities of thought) is, however, just an offering. I am finding that such an offering is a useful way of analyzing a great deal of what is taking place in the poetries that might be otherwise grouped under the rubric of Canadian avant-garde practices. The analysis could easily extend, for instance, to online poetic projects like Sachiko Murakami’s Project Rebuild and the connected book.35 A poetics of neoliberalism, one that is neither simply for nor simply against neoliberalism, but one that chafes, worries, and reworks the possibilities for thinking and speaking—such a poetics remains possible, and it is where some of the most exciting writing of the moment is being generated.

1 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 25. The idea that labour might exist in an unalienated form is, of course, also a response to Marx.

2 David Harvey, Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 271.

3 Charles Bernstein, A Poetics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), 163.

4 De Certeau, The Practice, xix.

5 See Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, 2nd ed. (London: Verso, 2001).

6 David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979, trans. Graham Burchell, ed. Michel Senellart (New York: Picador, 2008).

7 William Connolly, The Fragility of Things: Self-Organizing Processes, Neoliberal Fantasies, and Democratic Activism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 59.

8 Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Environment (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014).

9 Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (New York: Zone Books, 2010), 40.

10 Elizabeth Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 22.

11 See Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

12 Linda Hutcheon, A Poetics of Postmodernism: History, Theory, Fiction (New York: Routledge, 1988); Linda Hutcheon, The Politics of Postmodernism (New York: Routledge, 1989).

13 Linda Hutcheon, The Politics of Postmodernism, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2002), 166.

14 Hutcheon, A Poetics, 5.

15 Linda Hutcheon, The Canadian Postmodern (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1988).

16 Christian Bök, “Getting Ready to Have Been Postmodern,” Re: Reading the Postmodern: Canadian Literature and Criticism after Modernism (Ottawa: Ottawa University Press, 2010), 87–101.

17 Povinelli, Economies, 6.

18 Jeff Derksen, The Vestiges (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2013), 125.

19 Derksen, The Vestiges, 1.

20 Derksen, 12.

21 Derksen, 25.

22 Derksen, 9.

23 See British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, “8 Things You Need to Know about Bill C-51,” British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, bccla.org (11 March 2015).

24 Derksen, The Vestiges, 38.

25 Derksen, 39.

26 Derksen, 45.

27 See Edward Burtynsky, edwardburtynsky.com.

28 Derksen, The Vestiges, 45.

29 See Alan Greenspan “I Was Wrong about the Economy. Sort of,” The Guardian (24 October 2008).

30 “Poetic Visuality and Experimentation,” CanLit Guides, canlitguides.ca (2015).

31 Derek Beaulieu, Kern (Los Angeles: Les Figues Press, 2014).

32 Sina Queyras, “Lyric Conceptualism, A Manifesto in Progress,” Harriet: A Poetry Blog, poetryfoundation.org (2012); Sina Queyras, M × T (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2014), 38.

33 Gloria Galloway and Kathryn Blaze Carlson, “Tories Suggest Missing Aboriginal Women Related to Domestic Violence,” Globe and Mail, theglobeandmail.com (26 February 2015).

34 Rachel Zolf, Janey’s Arcadia (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2014), 103.

35 Sachiko Murakami, Project Rebuild (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2011).