Upon publication, Beautiful Losers (1966) sparked public debate: Was it excessively pornographic and worthy of condemnation, or was it, as Stan Dragland has argued, daringly Canada’s first postmodern novel, worthy of national praise? Cohen’s mixture of the sacred and the profane, his experimentation with the formal elements of the novel, and his incorporation of popular cultural products firmly root the text in the sixties and result in comparisons between Cohen and the likes of William S. Burroughs and Thomas Pynchon.1 Despite these virtues, the novel posed a challenge for its publisher, McClelland & Stewart, who feared it would be banned due to its pornographic content.

Regardless of this concern, Jack McClelland, McClelland & Stewart’s general manager, could not bear the thought that an American firm might publish a new novel by one of Canada’s great authors before a Canadian publisher released it.2 Thus, he planned a pre-emptive strike against public dissent, which consisted of a seven-part promotional scheme: first, a carefully planned launch party for 400 of Toronto’s most prominent artists and critics; second, a promotional card including artwork by Canadian abstract expressionist artist Harold Town, which was mailed to bookstores, reviewers, and libraries; third, another promotional card displaying additional work by Town, which was released the following week; fourth, a double poster, mailed to bookstores a few days after the second promotional flyer; fifth, another mailing, consisting of background on the novel’s composition, accompanied by quotations from Cohen’s work; sixth, the release of more advanced opinions by experts; and seventh, the purchase of ad space, with little more than the title, author, and price of the book.3 Throughout the advertising campaign, Harold Town’s illustrations, as well as his review of the novel, positioned Cohen’s work as part of the emergence of a Canadian avant-garde.

Considering McClelland’s fear of an obscenity charge, the choice of Town at first appears counter-intuitive. However, this careful pairing helped McClelland situate Beautiful Losers within an ongoing debate about freedom of expression in Canada. This essay investigates McClelland’s marketing scheme’s strange mixture of avant-garde imagery and nationalist rhetoric through the lens of what Jochen Schulte-Sasse calls “the social impotence” of the avant-garde, particularly when it comes to destabilizing the economic power structures that enable a bourgeois celebration of art as detached from social praxis.4 I argue that McClelland sought to stabilize two forms of institutional power: nationalism and democracy. On the one hand, McClelland’s tactics interpolate Town’s and Cohen’s critique of the institutions of bourgeois culture within McClelland & Stewart’s own nation-building practice. However, this accusation may be anachronistic, given that at the time nation-building was also an expression of a radical politics of decolonization. In this sense, the growth of Canadian publishing in the 1950s and 1960s, of which McClelland is often lauded as its symbol, can be seen as its own radical social formation. The economies of scale of Canadian publishing ensure that national publishing endeavours run counter to market forces. Herein lies the challenge of applying canonical theories of the avant-garde to a Canadian context, for surely the anxieties of the Futurists, Dadaists, and Surrealists in Europe and the United States were inflected differently from artists reacting against the institution of art within a Canadian context.

This essay’s definition of the avant-garde builds from Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde, which argues that art decoupled from life in the eighteenth century, when art ceased to be a conduit for religious ritual or monarchical power, and instead became a site of worship in its own right. L’art pour l’art movement, and bourgeois society more broadly, severed art from “the praxis of life.”5 The avant-garde did not so much react against the styles and techniques of its artistic predecessor’s investment in aestheticism (as did the modernists), but rather attacked the very institution of art that enabled the artist to stand at a distance from the social sphere. Bürger gives the example of Duchamp’s objets trouvés, which disavow the relationship between individuality and artistic creation. However, Duchamp’s ready-mades lose “their character as antiart” at the moment when they are installed in the gallery.6 While Duchamp’s experiments fail to integrate art into social praxis, they nevertheless succeed in highlighting the art galleries’ power to sanctify what constitutes art. The avant-garde’s revolutionary ambitions may have failed, but they remain important for exposing the institutions that govern cultural formations.

In 2010, Bürger responded to common critiques of Theory of the Avant-Garde, clarifying that the “paradox of the failure of the avant-gardists … [manifests when t]he provocation that was supposed to expose the institution of art is recognized by the institution as art.”7 However, “[o]ne could almost say: in their very failure, the avant-gardes conquer the institution.”8 The interpolation of avant-garde art into the gallery does not mean that the gallery remains unchanged. Rather, Bürger invokes Hegelian sublation to explain the dialectical transformation of the institution that results from the recognition of the everyday object as worthy of artistic scrutiny. Thus, Bürger redefines failure: the avant-gardists succeeded in provoking attitudinal changes, yet failed to incite revolution.

The comfort with which McClelland absorbs Cohen and Town into McClelland & Stewart’s nation-building practice highlights a similarly paradoxical failure by demonstrating how neither artist occupies the vanguard positions from which they claim to speak. Instead, the marketing scheme for Beautiful Losers reframes the agonistic logic that typifies avant-garde discourse:9 the “we” of Canadians against the cultural imperialism of a villainous American “them.” However, we may ask what this failure can teach us about the ideological seams of nation-building, especially given that McClelland did not see the avant-garde in Canada as at odds with his own nationalist endeavours.

In 1965, the year before the publication of Beautiful Losers, McClelland began soliciting advice on how best to position the novel in the Canadian marketplace. In a letter to Northrop Frye, dated 29 December 1965, he explained that

Because we consider Cohen an extremely important Canadian author, and because it is going to be published outside this country regardless of what we do, I have concluded that we must publish here despite the fact that we are almost certain to run into an obscenity charge either in Ontario or in the province of Quebec. The recent action in connection with Dorothy Cameron has convinced me that we are probably going to have trouble.10

In 1965, The Toronto Police Morality Squad raided Dorothy Cameron’s Yonge Street art gallery and confiscated Robert Markle’s nudes, forcing her to close the exhibition space while she awaited trial on obscenity charges.11 McClelland feared his publishing house would meet a similar level of censorship. In the name of national pride, and Canadian publishing more specifically, he planned a pre-emptive strike against public dissent.

At the centre of the seven-part marketing scheme was new artwork by Canadian abstract expressionist artist Harold Town, who was to feature prominently on all advertisements, as well as the book’s jacket. As McClelland explained to Corlies M. Smith at Viking Press, which was Cohen’s American publisher, Town was not only a contemporary and a friend of Cohen, but also “Canada’s best known and most highly regarded contemporary artist. At least to the younger group.”12 For McClelland, both attracted a similar audience, comprised of modern youth who epitomized the next generation of contemporary art.

In pairing Town and Cohen, McClelland made a comparison between abstract expressionism and the scope of Cohen’s work. As Serge Guilbaut notes, the artistic abandon of abstract expressionism came to be associated with the idea of freedom during the Cold War.13 A backlash to the realist propaganda employed in wartime, combined with both a resistance to Marxist thought in New York in the 1940s and the stifling effects of McCarthyism in the 1950s, produced a “self-proclaimed neutrality” among abstract expressionist artists.14 As a result, avant-garde artists “were soon enlisted by governmental agencies and private organizations in the fight against Soviet cultural expansion.”15 The dynamic colours and sweeping brushstrokes of this anti-representational style were “for many the expression of freedom: the freedom to create controversial works of art, the freedom symbolized by action painting, by the unbridled expressionism of artists completely without fetters.”16

Thus, McClelland’s choice to employ Town’s abstract expressionist imagery in the marketing of Beautiful Losers can be read in two complementary ways: first, it is another instance of McClelland looking to the United States for a product that he could rebrand with a maple leaf. McClelland & Stewart’s New Canadian Library serves as another example of this logic, because it draws not only its format, but also its name, from The New American Library.17 American practices heavily influenced McClelland’s understanding of national publishing. If abstract expressionism stood for American freedom, then Harold Town represented Canada’s ability to produce similar symbols of nationalist liberation. Second, it suggests a tempering of McClelland’s (and perhaps Town’s) commitment to the idea of an avant-garde revolution, a tempering also exhibited in Cohen’s novel, which sees American culture as the environment in which the characters swim. However, this failure to break out of these systems could also be read not as a wavering of their commitments, but rather as what Bürger calls an awareness of the impossibility of success. Quoting Pierre Naville’s La Révolution et les Intellectuels (1927), Bürger describes the avant-garde motto: “Notre victoire n’est pas venue et ne viendra jamais. Nous subissons d’avance cette peine.”18

In addition to providing visual interpretations of the text, Town penned a review for The Globe and Mail entitled “Confessions of a Literary Nibbler,” on 25 December 1965, arguing that Beautiful Losers

is the sort of work that inquisitional censors pray they will find under the Christmas tree; it makes Tropic of Capricorn seem like Winnie the Pooh, but is, I think, the first real proof that Cohen has authentic genius and that rarest of abilities, the power to create tenderness in a horrifying context.19

Town, as a figure in Cohen’s milieu, vouches for the writer’s “authentic genius” three months before the majority of the public could purchase the work. He also positions “inquisitional censors” against exceptional artists, encouraging readers to invest in a definition of the artist as a remarkable individual, who must be afforded freedom of expression in order to ensure that his insights reach the general public. In 1964, Marshall McLuhan published Understanding Media, in which he made a similar argument: The “serious artist is the only person able to encounter technology with impunity, just because he is an expert aware of the changes in sense perception.”20 Both McLuhan and Town position artistic vision against the general public’s blindness, thereby rendering censors unqualified to judge art, because censors operate from the disadvantaged position of the sightless. Town’s review then underwrites Cohen’s authority, by claiming clarity of vision, a privilege afforded only to genius artists.

Here, Town exhibits the paradoxical position of an avant-gardist who both erects the category of genius to justify his review and yet ostensibly deconstructs such categories, and the institutions that make these categories visible to the general public, in his artistic practice. The very notion of a “serious artist” presupposes a hierarchy of artistic practice that elevates certain artists to a canonical vantage. This oxymoronic impulse—to both fight against institutional power that severs art from everyday life and base this argument on the idea of genius, which is a concept at the heart of institutional power—drives avant-garde discourse. While the interpolation of avant-garde art into the art gallery often denotes failure in the counterculture, the inability of the avant-garde to find a way out of the use of the category of genius, represents another important failure, as exemplified by Town’s justification of reputational power as a necessary evil in the fight against systemic power.

Town’s review was part of McClelland’s strategy to sway public opinion with as many positive advanced critical reviews as possible. In an outline for the promotional program, dated 28 January 1966, McClelland informs his staff that the novel will “confound most of the critics, and certainly most of the public unless they are told in advance what they should believe.”21 This tactic sought to leverage the reputations of esteemed professionals, such as Town, in the service of Cohen’s novel. Simultaneously, it dispersed responsibility over a larger body of critics, relying on the cultural capital of others employed in the creative industries not only to buttress Cohen’s reputation, but also to protect McClelland & Stewart against public scrutiny.

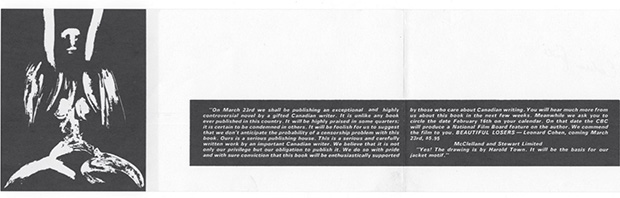

FIGURE 1 Pre-publication advertisement for Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, featuring original artwork by Harold Town (1966).

FIGURE 2 Post-publication advertisement for Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, featuring original artwork by Harold Town (1966).

The first advertisements for the novel consisted of a two-part series of black-and-white cards that were distributed to libraries, book reviewers, and employees of the book trade in advance of the launch. These cards paired Town’s abstract expressionist illustrations with justifications for the publication of the controversial novel. The illustrations for both cards depict human forms, but the black-and-white images abstract the body to the point of confusion. The first (Figure 1) shows a long-haired figure bending forward so that a cascade of tresses blocks his or her face from view. The second illustration (Figure 2) shows a bird-like body with legs that end in large claws and arms that fold into wing-like shoulders. Both androgynous bodies lack facial details and have a grotesque beauty. Situated on a flap that folds over the accompanying text, these illustrations occupy one-third of the card and can be turned, like opening the cover of a book, to reveal the full text of the advertisement.

The first card asserts, “[o]urs is a serious publishing house. This is a serious and carefully written work by an important Canadian writer. We believe that it is not only our privilege but our obligation to publish it.”22 This justification shifts attention away from the novel and towards the publisher, leveraging the “serious[ness]” of McClelland & Stewart’s brand to vouch for the quality of the book.23 McClelland fails to name the cause for which he feels an “obligation.”24 Be it an obligation to the nation, or an obligation to the publishing profession and literature more broadly, McClelland invokes nationalist sentiments to explain his support for a controversial work of art. The use of Town reiterates Cohen’s position as a prominent Canadian artist. Thus, McClelland frames dissent against the novel as an attack on both artistic freedom and nationalism.

The second version of the card, mailed to the same recipients the following week, addresses Cohen’s novel more directly. Although it begins with a reference to the work as a “controversial new novel,” it concludes that it is a “disagreeable religious epic of incomparable beauty.”25 While conceding that the novel “will mean different things to many people,” the inclusion of an anonymous interpretation provides a positive reading of the novel that could be adopted by the general public.26 McClelland often employed this tactic, most notably in the introductions that accompanied each edition in the New Canadian Library, where Canadian scholars leveraged their reputations to attest to the value of Canadian literature. These paratextual elements manage the reputations of the texts that they envelop; as acts of canon-formation, they highlight McClelland & Stewart’s role in cultivating the authority of its writers.

Both advertisements for Beautiful Losers conclude with an aside to direct the reader back to the illustration by Town: “Yes! The drawing is by Harold Town. It will be the basis for our jacket motif,” and “P.S. You’re right! That is another Harold Town illustration. It will be part of our jacket design.”27 The emphasis on Town positions Cohen’s novel at the forefront of the Canadian avant-garde. Fiercely critical of the Canadian art world’s lack of support for local artists, Town worked as an activist for Canada’s creative community. The hopeful impetus behind activist endeavours demonstrates what Gregory Betts describes as the key assumption of avant-gardism: that current tastes are inadequate and that “society can be remade.”28 While Town’s prominent role in the public sphere may at first resemble a public intellectual—“in 1966 alone, [Town] appeared in seventy-two articles in the three Toronto daily newspapers”29 (more than any avant-garde artist)—these two concepts are not immediately at odds within Canada’s postcolonial context.

In Avant-Garde Canadian Literature: The Early Manifestations, Betts delineates Canadian avant-gardists’ complicity in both commercialism and nationalism in the face of the dominant “colonial imagination.”30 The Canadian iteration of this future-oriented movement did not subscribe to total revolutionary change, so much as it advocated for Canadian artistic production, and thus “postcolonial agency” from both Britain and the United States.31 By borrowing European aesthetic models to advocate for Canadian artistic institutions, the Canadian avant-garde did not seek “to recondition the general category of reality and restart history,” but rather “sought to recondition the experience of reality in Canada and to envision the start of a truly Canadian” artistic history.32 While Betts grounds his book in literary history, his argument readily applies to Town’s advocacy work.

Town refused to relocate to the United States, despite the affordances of the art market to the south. Instead, he positioned himself in Toronto’s artistic milieu, receiving the Order of Canada in 1966 and the Canada Centennial Medal the year after.33 Town remains most famous for his role in Painters Eleven (1953–1960), a movement without a manifesto, which nevertheless stood in opposition to the landscape paintings of the Group of Seven (1920–1931).34 In the catalogue for the Art Gallery of Ontario’s 1986 exhibition of Town’s work, David Burnett argues that the unifying concept of Town’s career was a consistent attack against “the armies of the bland.”35 However, Town used his prominence in the public eye to attack not only boring art, but also institutions of power and domination that obfuscate social injustice.

In 1964, Town represented Canada at the prestigious Venice Biennale with his exhibition Enigma. During the Biennale, a cardinal ordered two of the Enigma drawings removed.36 The compositions depict professional men and woman (doctors, priests, judges) in positions of submission and domination to investigate, what Town claimed were, the “social wrongs and follies, of the hypocrisies, complacency, and self-seeking of those who hide behind the mystique of professionalism or the cosseted power of institutions.”37 While Town referred to these drawings as his “political cartoons,” others called them pornographic, misogynistic, obscene, bestial, savage, and satiric.38 Town’s explicit politics, combined with his artistic technique, express the avant-garde belief that “art has a socially consequential role only when it is somehow related to a socially relevant discussion of norms and values and thus to the cognition of society as a whole.”39 In fact, it is this investment in rescuing art from its isolation in artistic institutions and resituating it within social praxis that distinguishes avant-garde from modernist art. Both avant-garde and modernist artists react to growing industrialization, globalization, urbanism, and mass culture precipitated by capitalism; however, the avant-garde remains distinguishable from modernism in its will to political power, “tempted by the opportunity to see their revolutionary projections realized in a world in need of revitalizing.”40

When the CBC called Town to ask him to comment on Enigma, he revelled in the criticism: “[i]t’s such an honour being banned in Italy, the mother of sensuality [he explained.] It’s like being asked to straighten your tie in a bordello.”41 The litany of criticism Town received for Enigma parallels the media frenzy that erupted concerning Cohen’s work Beautiful Losers. Although the book was never banned, as McClelland feared it would be, its reception was polarized. Upon release, The Globe and Mail described it as “verbal masturbation,” and Toronto Daily Star critic Robert Fulford called it

The most revolting book ever written in Canada.… I believe everything he writes is entirely within the proper range of literature, but it seems to me his book is an important failure. At the same time it is probably the most interesting Canadian book of the year.42

Many bookstores, most notably W.H. Smith and Simpson’s, decided they did not want the risk of carrying it, a decision that considerably decreased sales.43 In contrast, avant-garde poet and publisher bill bissett raved, “i give th book of cohens a good review, a great review, easily million stars [sic].”44 When asked to defend the book in an interview with Adrienne Clarkson on her show Take 30, on 23 May 1966, Cohen responded,

I’d feel pretty lousy if I were praised by a lot of the people who had come down pretty heavy on me. I think in a way there’s a war on. It’s an old, old war.… [I]f I had to choose sides … I’d just as well be defined as I have been by the establishment press.45

The old war Cohen identifies pitted those who hold institutional power against a new wave of creative energy.

Cohen’s dichotomy between the “establishment press,” which censors artists, and the “new vanguard,” which battles for freedom, falls apart when read in the context of Donald Brittain’s and Don Owen’s National Film Board (NFB) documentary, Ladies and Gentleman … Mr. Leonard Cohen, which proved “crucial in launching his performance career,” advertising the poet to John Hammond of Columbia Records.46 At the end of filming the directors invite Cohen to a private screening so as to catch his reactions on camera. These remarks close the documentary. The footage reveals Cohen in the intimate acts of domestic life: sleeping, bathing. Confessing the staged nature of these private moments, Cohen admits, “the fraud is that I am not really sleeping.”47 While bathing, he writes in black marker on the wall behind the tub “caveat emptor.”48 When asked to translate the phrase, Cohen explains it means “buyer beware … I had to warn the public that [my performance] … is not entirely devoid of the con.”49 Cohen’s work as a self-proclaimed “double-agent” productively effaces the truth-claims of documentary film, proving him trustworthy.

This “ironic accommodation” of the documentary form constitutes a fairly common modernist response to the institutions that promote literary celebrity.50 Joe Moran, however, ascribes this quality to all literary celebrities, who must present themselves as both extraordinary and familiar, as their lives and work are “ransacked for their human interest at the same time as they are lauded for their difference and aloofness.”51 This celebration of paradox marks the reader’s “nostalgia for some kind of transcendent, anti-economic, creative element in a secular, debased, commercialized culture.”52 By unmasking the apparatus—the conscious techniques that support documentary’s truth claims—Cohen appears to rise above them. As such, he presents himself to the viewer as authentic, diffident even. Essentially, Cohen distances himself from the blatant act of self-promotion—starring in a film that only furthers his presence in the public sphere—by drawing the viewer’s attention to the constructed nature of such projects. In so doing, he becomes the biographical subject and the biographer at the same time. This distancing from the media apparatus is echoed in his term “establishment press,” but the binary between established and marginal falls apart in the Canadian context. While the NFB certainly employs film as a “citizen building technology,” and had the expressed purpose of naturalizing new immigrants, this nationalist initiative is firmly located in the nation’s transition from a British to an American sphere of influence.53 As Canada moves from being a literal colony to a colony by virtue of both capital and cultural interpolation, the NFB operates from an anti-colonial position.

The NFB’s documentary on Cohen was screened at the very expensive launch party for Beautiful Losers, which was held almost a month before the novel’s publication, on 29 March 1966, at the Centennial Ballroom, located at the Inn on the Park in Toronto. The 400-person all-star guest list for the carefully orchestrated, open-bar affair included Pierre Berton, Marshall McLuhan, Harold Town, and almost every prominent writer in the Toronto region.54 However, Cohen failed to attend the party. Disappointed with sales figures, Cohen implored McClelland to mount a more extensive advertising campaign. On 9 May 1966, McClelland composed a six-page response to defend the publisher’s efforts, which outlined the 300 copies of the novel sent to reviewers; the numerous press releases, specialty coasters and posters; and the expensive launch party that Cohen had failed to attend. In fact, McClelland claimed it had received “more direct promotional effort than any other book [had] received.”55 McClelland then berated Cohen for his failure to participate in this promotional process. In an attempt to distance himself from the marketing of his work, Cohen instead lobbied McClelland to invest in more advertising. In this way, Cohen asked McClelland to claim responsibility for the commoditization of his art, so that he could maintain a critical distance from the tarnishing effects of the market. When read in this context, we can see how Cohen’s agonistic statement about the “establishment press” attempts to erect what Stephen Voyce calls “the moral superiority of the ‘we’ against the banality of the ‘they,’”56 but Cohen is colluding with the “they” behind the scenes.

Linda Hutcheon reads Beautiful Losers, a novel sprawling in its scope, as an allegory for Canada’s political history. The novel’s four prominent nationalities—the First Nations (represented by Edith and Catherine Tekakwitha), the French (represented by the Québécois separatist F.), the English (represented by the anglophone professor I.), and the American (represented by the invasion of American mass culture in the form of comic books, advertisements, and cinema)—create a hierarchy of domination and pose the ethical question of the novel: How do we “become ‘beautiful losers’ able to deal with our loss without taking it out on someone else?”57

Robert David Stacey’s recent work on the novel delineates the tension between I.’s banal “repression and violent introjection, symbolized by his dedication to the past and his chronic and painful constipation” and F.’s doctrine of “futurity.”58 F.’s aesthetic vision, which seeks to “connect nothing,”59 nevertheless reveals an obsession with systems in general. As the spokesperson for newness as a disciplined regime, F. reveals the megalomaniacal-ego at the heart of creation:

If Hitler had been born in Nazi Germany, he wouldn’t have been content to enjoy the atmosphere. If an unpublished poet discovers his own image in the work of another writer it gives him no comfort, for his allegiance is not to the image or its process in the public domain, his allegiance is to the notion that he is not bound to the world as given, that he can escape from the painful arrangement of things as they are.60

As a separatist, F. asserts that Canada represents one such “painful arrangement.” However, F.’s admission that Hitler displays a similar mania to poets paints history’s most villainous politician and avant-garde artists with the same wary brushstroke. Both strive towards radical social formations, but their legacy-oriented motivations call their projects into question.

Here Cohen demonstrates his awareness of the close relationship between fascism and the avant-garde, both of which assert “violence as an ethical and regenerative force.”61 In his work on the close relationship between Georges Sorel and the French avant-garde, Mark Antliff argues that “[t]o be truly beautiful, Sorelian violence had to express the creative and moral transformation of each individual, otherwise it would resemble the brutal, immoral violence of the tyrant.”62 The justification of literal violence as a necessary force to destabilize systemic tyranny not only parallels the representational violence foregrounded by avant-garde artists, but also surfaced in the political allegiances of anglophone writers like Wyndham Lewis, who praised Hitler, and Ezra Pound, who supported Mussolini. These Vorticist writers “realized that controlling language, and by extension the media, meant controlling the culture and all those in it. This realization (and the revolutionary impulse to correct the denigrating course of Western culture that it inspired) led both Pound and Lewis to fascism.”63

When McClelland marked Beautiful Losers as Canadian literature by stamping it with the McClelland & Stewart brand, he interpolated F.’s separatist imagination within the publishing house’s nation-building practice. With the book’s transformative exploration of extreme violence, as exemplified by many of the masochistic characters, McClelland’s ability to locate this text within the canon of Canadian literature perhaps represents one of the book’s important failures: its aggressive sexuality and violent politics are assimilable into a national discourse. McClelland sublated the novel’s pulpy sexuality, positioning the book as literature by publishing it in a hardcover format with an “expensive jacket and a good binding.”64 In fact, the four thousand copies of its first print run sold for $6.50 a book, making it slightly more expensive than other books on the market.65 While Malcolm Ross, the editor of McClelland & Stewart’s New Canadian Library, refused to include Cohen’s novel in the series on the grounds that it was “obscenity for obscenity’s sake,”66 it was the first book added to the series upon Ross’s retirement in 1978. From the initial marketing scheme to its position in the New Canadian Library, McClelland absorbed the more agonistic aspects of the text into his national publishing framework.

Although McClelland worked in publishing from 1946 to 1987, he did not become general manager of McClelland & Stewart until 1952, essentially taking over the firm from his father.67 Throughout his tenure, McClelland tried to balance the heterodoxical objectives of running a profitable business, a service company, and a philanthropic enterprise; as McClelland said, McClelland & Stewart’s objective was “not profit, but profit from a particular field of endeavour,” specifically the service of Canadian authors.68 McClelland’s dedication to Canadian publishing was founded on an awareness of postwar trends. When McClelland took over the company he felt “that upswings in population numbers, education opportunities, leisure time and improved communications boded well for books.”69 This was a time of unprecedented growth in secondary and post-secondary education as a result of the baby boom. The ballooning of higher education translated into additional textbook acquisitions, the growth of libraries, and higher literacy rates. Nevertheless, a small population, a large geography, and competition from the south made Canada a difficult country in which to grow a national publishing culture. In opposition to the cultural invasion from the south, McClelland worked as Co-Chairman for the Committee for an Independent Canada (CIC), an organization that lobbied government for limits to foreign investment and ownership.70

Internationally, the postwar period saw rapid decolonization, and Canada, along with other post-colonial nations, sought to find independence on the world stage. As Canada became politically and economically tied to the United States, culture came to be viewed as one of the last fields of independence. Although nation-building is often understood to be a top-down project, McClelland used the firm, which he inherited from his father, to serve a nationalist agenda. The field of cultural production looks different from a Canadian perspective because of the country’s colonial heritage, proximity to the United States, small population, and relatively short history as a nation. In a Canadian context, the world of symbolic capital aligns not so much with avant-garde artistic endeavours as with domestic production, because the economically successful side of the field is occupied, almost entirely, by foreign production. Thus, domestic production becomes symbolically valuable as the antithesis to a British or American mass-media invasion.

McClelland’s dedication to domestic production resulted in the Guadalajara International Book Fair proclaiming him, in 1996, “the outstanding Canadian publisher of his generation.”71 In a letter of support for the award, fellow publisher Anna Porter named Jack McClelland the “prince of publishing,”72 a nickname that stuck. After the prince had abdicated his throne and retired, Leonard Cohen wrote him, proclaiming, “[y]ou were the real Prime Minister of Canada. You still are. And even though it has all gone down the tubes, the country that you govern will never fall apart.”73 Cohen’s elegy asserts Canadian publishing’s integral contribution to nation-building, but it also betrays his nostalgia for a kind of postwar optimism predicated on a desire for Canadian cultural independence.

Beautiful Losers, both the novel and the epitextual material, highlights how the Canadian avant-gardists were seeking to harness the burgeoning power of the nation state to create a home for their revolutionary projections. However, this case study also exposes how this failure has a particular inflection when located in a postcolonial context. If abstract expressionism came to stand for freedom during the Cold War, as Guilbaut has argued, we might ask what this same technique tells us about freedom in a Canadian context. In the Canadian milieu, with its particular tensions of cultural imperialism and decolonization, freedom also meant freedom from American cultural invasion, and thus the erection of protectionist policy in the service of national artists. Ironically, this freedom to create art necessitated institutional structures and systems to support it.

1 See Dennis Duffy, “Beautiful Beginners,” in The Tamarack Review 40 (Summer 1966); and John Wain, “Making It New,” in Leonard Cohen: The Artist and His Critics (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1976).

2 In the end, McClelland & Stewart published simultaneously with Viking Press in the United States.

3 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

4 Jochen Schulte-Sasse, “Foreword: Theory and Modernism versus Theory of the Avant-Garde,” Theory of the Avant-Garde, by Peter Bürger, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), xlii.

5 Bürger, Theory, 49.

6 Bürger, Theory, 57.

7 Peter Bürger, “Avant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde: An Attempt to Answer Certain Critics of Theory of the Avant-Garde,” New Literary History 41.4 (2010): 705.

8 Bürger, “Avant-Garde,” 705.

9 Stephen Voyce, Poetic Community: Avant-Garde Activism and Cold War Culture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 13.

10 Jack McClelland, Letter to Northrop Frye, 29 December 1965 (McClelland Box 20, File 8).

11 “Cops Ban ‘Lewd’ Drawings,” This Hour Has Seven Days, 6 February 1966 (CBC Digital Archives).

12 Jack McClelland, Letter to Corlies M. Smith (McClelland Box 20, File 8).

13 Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 201.

14 Guilbaut, How New York Stole, 11.

15 Guilbaut, 11.

16 Guilbaut, 201.

17 The New American Library was an autonomous publishing company that broke out of Penguin Books (Janet Friskney, New Canadian Library: The Ross-McClelland Years, 1952–1978, 36).

18 Bürger, “Avant,” 700.

19 Harold Town, “Confessions of a Literary Nibbler,” Globe and Mail, 25 December, 1965, A14.

20 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Toronto: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 18.

21 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

22 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

23 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

24 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

25 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

26 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

27 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

28 Gregory Betts, Avant-Garde Canadian Literature: The Early Manifestations (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 17.

29 Iris Nowell, P11 Painters Eleven: The Wild Ones of Canadian Art (Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 2010), 171.

30 Betts, Avant-Garde, 65.

31 Betts, 62.

32 Betts, 63.

33 Nowell, P11, 162–167.

34 See Lynda Shearer, Painters Eleven, and Brandi Leigh, “An Introduction to the Group of Seven.”

35 David Burnett, Town (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991), 98.

36 Nowell, P11, 165–166.

37 Town quoted in Nowell, P11, 166.

38 Nowell, P11, 166.

39 Schulte-Sasse, “Foreword,” xiii.

40 Betts, Avant-Garde, 203.

41 Town quoted in Nowell, P11, 166.

42 Robert Fulford, “Leonard Cohen’s Nightmare Novel,” Toronto Daily Star (26 April 1966).

43 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

44 bill bissett, “! ! ! ! !” Rev. of Beautiful Losers, Alphabet 13 (June 1967), 94.

45 “Beautiful Losers Praised and Condemned,” Take 30, hosts Adrienne Clarkson and Paul Soles, CBC Digital Archives.

46 Keith Harrison, “Ladies and Gentlemen … Mr. Leonard Cohen: The Performance of Self, Forty Years On,” Image Technologies in Canadian Literature: Narrative, Film, and Photography (Brussels: PIE Peter Lang, 2009), 69.

47 Donald Brittain, dir., Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr. Leonard Cohen, perf. Leonard Cohen (National Film Board of Canada, 1965).

48 Brittain, Ladies and Gentlemen.

49 Brittain, Ladies and Gentlemen.

50 Aaron Jaffe, Modernism and the Culture of Celebrity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 177.

51 Joe Moran, Star Authors: Literary Celebrity in America (Sterling: Pluto Press, 2000), 8.

52 Moran, Star Authors, 9.

53 Zoë Druick, Projecting Canada: Government Policy and Documentary Film at the National Film Board (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), 4.

54 Ira Bruce Nadel, Various Positions: A Life of Leonard Cohen (Toronto: Random House of Canada, 1996), 138.

55 McClelland Box 20, File 1.

56 Voyce, Poetic Community, 14.

57 Peter Wilkins, “‘Nightmares of Identity’: Nationalism and Loss in Beautiful Losers,” Essays on Canadian Writing 69 (1999), 25.

58 Robert David Stacey, “Mad Translation in Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers and Douglas Glover’s Elle,” English Studies in Canada 40.2–3 (June/September 2014), 179.

59 Cohen, Beautiful, 17.

60 Cohen, 59.

61 Mark Antliff, Avant-Garde Fascism: The Mobilization of Myth, Art, and Culture in France, 1909–1939 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 5.

62 Antliff, Avant-Garde Fascism, 6.

63 Betts, Avant-Garde, 201.

64 Nadel, Various Positions, 439.

65 Nadel, 439.

66 Ross quoted in Janet Friskney, New Canadian Library: The Ross-McClelland Years, 1952–1978 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007), 113.

67 James King, Jack: A Life with Writers: The Story of Jack McClelland (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), 308.

68 King, 108.

69 King, 43.

70 The desire to block out American investment was complicated later in his career by McClelland’s initiative to “create a larger market for Canadian books by forming an association with … Bantam Canada” (King 308). This new option, which had been forbidden by Canada’s Foreign Investment Review Agency until 1977, allowed McClelland to benefit from the improvement to the economies of scale, arising from combined markets.

71 Roy MacSkimming, The Perilous Trade: Book Publishing in Canada, 1946–2006 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2007), 118.

72 MacSkimming, The Perilous Trade, 118

73 Cohen quoted in King, Jack.