bpNichol is a well-known Canadian experimental writer of poetry, fiction, criticism, and even television shows. Lesser known is the fact that he was also passionate about reading, writing, and publishing comics. Both his knowledge of comics and his collection of comics were substantial enough for him to have played a formative role in the development of Ron Mann’s award-winning 1988 documentary Comic Book Confidential,1 which is in turn dedicated to Nichol. He supported the publication of other experimental collections, such as the anthology series Snore Comix (1969–1970) from Coach House Press, and he encouraged other creators around him “to produce innovative expressive forms.”2 Most notably, according to Canadian comics archivist John Bell, Nichol created the first underground, avant-garde comic in Canada with the publication of Scraptures 11 in 1967.3 Nichol’s playful and prolific contributions to multimodal literature (both poetic and narrative) were among “his most experimental achievements,”4 and they were influenced by the “imagism of the comic book form.”5 bpNichol’s comics straddle many avant-garde ideals found across his oeuvre. Furthermore, these comics function as manifestos that both embody and promote his artistic approach to the medium of this genre. By analyzing these comics, I hope to increase our understanding of Nichol’s experimental poetics, while securing his place at the emergence of postmodernity in Canada.

Nichol’s comics should be considered significant precursors to later postmodern works. Critical theorist Linda Hutcheon, for example, champions comics (in their culturally more accepted form of “graphic novels”) as “a postmodern genre par excellence” because of “the postmodern interest in the semiotic interaction between the visual and the verbal.”6 Thus, comics embody what Matei Călinescu calls postmodernity’s “double coding.”7 While Hutcheon focuses on work by Chester Brown and Seth (from the 1980s onward), we might look earlier for precursors. We can trace these theoretical innovations in comics in Canada to bpNichol, along with several other underground, experimental creators in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including (among others) John Riddell, bill bissett, Martin Vaughn-James, and Rand Holmes. Later postmodern creators like Brown and Seth draw their inspiration8 not only from these more avant-garde, counter-cultural small-press artists but also from the parallel developments of a “countercultural urgency”9 in American and British underground comics at the time.10 As I argue, Nichol’s comics showcase a significant shift from avant-garde to postmodern interests, and such comics reflect what Călinescu has described as the general “crisis of the avant-garde” in the 1960s.11 This crisis involves a shift in the practices and motivations of creators and theorists alike from an avant-garde emphasis on creative destruction to the postmodern self-reflexive construction of ambivalence, focusing on “a logic of renovation rather than radical innovation.”12 The postmodern approach re-evaluates the principles and practices of its antecedents through a multi-faceted reflection that produces textured understandings rather than absolute judgment.13 Nichol’s comics embrace this crisis of representation and subsequent turn to postmodern multiplicity, often offering humorous compositions that both rupture and reclaim the possibilities of narrative and expression.

The experimentalism of bpNichol, along with some of his contemporaries, foregrounds a complex interrogation and manipulation of the medium. Hillary Chute suggests that the increasingly self-reflexive qualities of underground, alternative comics, which begin in the 1960s, derive from the medium’s overt showcasing of its own materiality: “Comics, then, is a non-transparent form that always shows its seams, calling attention to its construction…. [C]omics has always been formally experimental.”14 In what follows, I focus on specific deconstructive manipulations characteristic of Nichol’s comics, so as to draw attention to how the medium both motivates and constrains experimentation and communication. Nichol’s playfulness reaffirms not only materialist practices, but also mythopoeic practices in the genre. His work makes a significant contribution to the emergence of postmodernism in Canadian comics.

bpNichol’s knowledge of comics history grounded many of his innovative texts, and he actively worked to highlight and promote this knowledge. For instance, he dedicated his edited collection of Canadian concrete literature, The Cosmic Chef, to five early innovators of comics.15 He also republished works by the early, formal visionary Winsor McCay (one of the dedicatees), who clearly made an impression on Nichol through the use of skilful storytelling and careful illustration.16 McCay was a groundbreaking innovator who helped establish the conventions for the layout of panels in comics,17 and he dabbled in arenas of the avant-garde. For instance, his Little Nemo in Slumberland combined elements of both Art Nuevo and Surrealism, and the work expressed the modernism of the mass market.18 Nichol adopted and adapted these conventions and predilections, while freely exploring their more abstract, theoretical qualities. As Paul Dutton notes,

Nichol didn’t just read and collect comic books and comic strips, he studied and revered them, finding rich veins not just of humour but of esthetic thrills and of insight into the workings of the mind. He once wrote that Winsor McCay, an early twentieth-century Sunday comics genius and a pioneer of animation, exposed the unconscious of the upper and middle classes.19

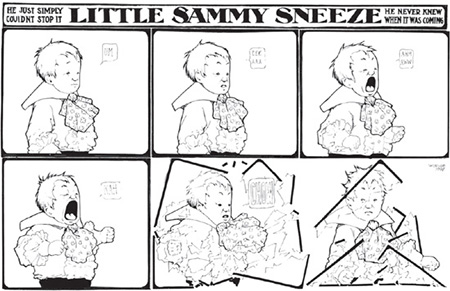

Nichol is particularly attuned to the role of the panel in comics storytelling—so much so that he refers to the study of “the art of the comics” as “panelology.”20 The layouts used by McCay make him one of Nichol’s important predecessors. For example, in the following example of McCay’s popular comic strip Little Sammy Sneeze (Figure 8), McCay employs the frame of the panel for humorous, dramatic effect. He maintains the convention of sequences, presenting a series of brief moments in close succession, all of which recapitulate the title of the strip by capturing the process of Sammy sneezing. McCay challenges comic-strip conventions not only by breaking the frame around the action, but also by breaking the fourth wall for the reader.

FIGURE 8 Winsor McCay’s Little Sammy Sneeze (New York Herald, 24 July 1904).

Winsor McCay’s Little Sammy Sneeze foregrounds several features and functions of the panel, a component that Nichol considered “exoskeletal” 21 to the form of comics.22 For instance, panels can bring together any type of picture and text, each of which can be manipulated to focus readerly attention upon a given action. Pictures and language both have a host of culturally specific conventions that render them meaningful to readers in this “hybrid art form.”23 By engaging different cues in a panel, readers draw on their “multiliteracies”24 to interpret the expression and interaction of elements within the comic. For instance, Sammy’s position, facing towards the next panel, helps propel readers through the strip, as we follow his gaze. At the same time, repetitions of, and subtle adjustments to, the onomatopoeic language (via changes in font style) and depicted prompts (via changes to mouth and hands) further propel the reader towards the conclusion by focusing on cues necessary for understanding the undeniable force of the sneeze. Panels also separate and sequence communicative elements so that readers must interpret their interrelations. Nichol refers to “the meaning derived from the relationship between panels” as “panelogic.”25 Other scholars also suggest that this panelogic of comics, which “[utilize] the eye’s ability to perceive simultaneously a number of elements,”26 including segmentarity and concurrency, constitute the core quality of the medium as a whole.

Part of the panelogic of comics is the potential for the frames of panels to contribute to their interaction by being invisible, minimal, or decorative. The frame typically supports the separation of panels, to clarify where pictures and words begin and end, thereby helping focus the reader’s attention on a given panel. In this comic strip, without the frame, especially in such close proximity, it might appear that there are multiple Sammys in various states of action at once, rather than a sequence of one figure slowly building toward the slapstick finale. Thus, the frame focuses the reader on elements of the panel, while also creating gaps between panels, thereby giving the reader space (literally) to build inferences about interactions between elements.

As with all communicative conventions, these basic functions of panels and frames can either be creatively affirmed or subverted by an author. These functions remain crucial to the works of both Nichol and McCay. In the second-to-last panel, Sammy seems to blow apart the panel frame through the force of his sneeze, and in the final panel he rests dishevelled and disgruntled, looking out at the reader. The parts of the frame themselves also look like a house in pieces around Sammy. Here, McCay strategically employs the conventional frame—typically used to focalize and sequence relevant elements within the story—as a material element within the story-world, as a window frame, which conveys the dramatic force of the sneeze. Breaking the panel transforms it from a peripheral, perceptual device to an active representational contributor to the content of the story. Furthermore, the use of two panels to show both the breaking of the frame and the response of Sammy to it requires the continued use of sequentiality. This active doubling of the functions of both the frame and panel helps to accentuate Sammy’s expression in the final panel; rather than being surprised at the intrusion of the frame into his world, he simply accepts it, allowing it to accentuate the dishevelment of his sullen demeanour.

In the final panel, Sammy turns to gaze out toward the reader, breaking the “fourth wall” and establishing an intersubjective connection. This break emphasizes his silent punchline given through his facial expression, which might be verbalized as “you’ve got to be kidding me.” He feels disgruntled, while the reader feels delighted by this unconventional finale. This break from an objective perspective to an intersubjective perspective explicitly integrates the reader into the meaning of the comic. Scott McCloud has popularized the participatory role of the reader in comics, noting that the reader brings “closure”27 to the work by integrating components both within panels and between panels so as to comprehend the comic.28 In fact, this notion draws heavily from earlier work by Marshall McLuhan, who in Understanding Media (which McCloud recommends) notes that comics “provide very little data about any particular moment in time, or aspect in space, or an object. The viewer, or reader, is compelled to participate in completing and interpreting the few hints provided by the bounding lines.”29 Likewise, Nichol recognizes the potential for communicative practices to open up spaces for the participation of readers. For instance, in his commonly quoted manifesto, “statement, november 1966,” he affirms the need to diversify communicative practices so that creators can construct “as many exits and entrances as are possible” to interact with readers.30 His approach to comics reflects this interactive, participatory potential of the medium.

Nichol explores the multiple functions of panels and frames in a manner that illustrates his interest in the materiality, sensuousness, and openness of communication. This poetics finds itself expressed through the twin notions of the “paragrammatic” text and the “’pataphysical” text. The paragrammatic text enacts a strategy of visual rupture and proliferation of possible meanings (as seen, for example, when Nichol derives names for saints from words beginning with the letters “ST” in The Martyrology). Similarly, the ’pataphysical text presents a spoof of science by pushing possibilities for meaning in all directions beyond reason towards the absurd. As I will argue through Nichol’s comics, these approaches transform the modalities of panels by altering their “panelogic” of both composition and connection. Furthermore, this approach correlates to what Gregory Betts has described as the emergence of “postmodern decadence” in Canada during the 1960s and 1970s when creators, including bpNichol, begin to emphasize a radical embrace of rupture. Betts argues that “[s]elf-conscious and self-reflexive decadent texts are not merely about desystematized meaning—they embody it.”31 I show how two representative comics by bpNichol, Fictive Funnies (created with Steve McCaffery) and Grease Ball Comics, embody these concepts. At the same time, these comics maintain a distinctly avant-garde hopefulness, which decadent texts typically deny, by exploring postmodern interests in recursivity and renovation. Furthermore, these comics act as art manifestos, arguing for an avant-garde sensibility that incorporates experimentation into the form of the medium.

To unravel the communicative complexity of Nichol’s comics, I begin with the short, collaborative comic Fictive Funnies by bpNichol and Steve McCaffery (Figure 9). This first page was drawn almost completely by Nichol, with McCaffery adding the illuminating note at the bottom.32 While it is a seemingly straightforward work, such simplicity is but an illusion.33 Nichol’s commonly used and easily recognized character, Milt the Morph, here in disguise as “Syntax Dodges,” finds a pun, trips a trap door, and falls through the frame into the panel below. While a seemingly straightforward, causal sequence, the materialized pun unravels conventional thinking—as all good puns do—and develops a commentary on the medium through its transformations of the panel, the character, and the story-world. Visualizing the pun as a trap door (and perhaps the figure peeking over the mountain as the author of the pun), Nichol doubles the meaningfulness of the frame as a physical object and a perceptual space, much like McCay has done with the final panels of Little Sammy Sneeze. In this case, Nichol literalizes a pun by causing the figure to fall downward into a different, conceptual story-world.

The pun represents the border of the panel as both a discursive boundary and an ontological divide (whose hardness and materiality appear in the shelf-like depiction of its trap-door). The door functions as “a hole in the narrative” through which a new story-world might interrupt the linear reading of panels. The shift in panelogic, by moving the reading direction vertically rather than horizontally, affirms the promise of the title to provide the “way out of the NARRATIVE CHAIN.” Interestingly, the new panel, which functions as a new world, is one in which subjectivity is also multiplied, since “Syntax Dodges” no longer coheres individually in a panel, but multiplies within it, becoming somewhat transparent (see the overlapping hands and feet). In this other world, the multiplying power of the pun dissolves subjectivity and linearity, pulling apart assumptions of identity and causation, all of which typically inform the narrative conventions of comics.

The fractured transformation of the conventional panel visualizes the action of a pun, which splits reference and, therefore, disrupts narrativity by dividing the focus of the reader. This split creates a tension between the visual sequence (which maintains a coherent landscape across the top of the page), and the action sequence that draws the reader vertically down the page. As McCaffery’s diagrammatic note at the bottom of the comic asks: Does this redirection of the reader qualify as a “meaningful sequence?” What is especially meaningful about the multiple subjects and the parallel worlds created by the pun?

FIGURE 9 First page of Fictive Funnies by Steve McCaffery and bpNichol, reproduced in Rational Geomancy: The Kids of the Book Machine (Talonbooks, 1992).

These burgeoning questions stem from the paragrammatic properties of this page, which strategically misuses established conventions to construct alternative approaches to the comic, and therefore, to narrativity. McCaffery describes paragrams as constructing “an anamorphic operation of the word on its own material interiority,” such that “errant” or excessive linguistic features can be utilized for poetic meaning. Curiously, McCaffery characterizes the paragram in Nichol’s poetry as the “comic stripping of the bared phrase.”34 As a manipulation of representational features, the notion of the paragram easily applies to comics. Pictorial communication can also be subjected to “anamorphic operations” to expose the material alterity within the conventions of this genre. For instance, every panel border can be read as a picture frame (as seen in Little Sammy Sneeze), or as a wide board upon which the characters move (as in Fictive Funnies). Here, we can see paragrammatic possibilities at work through the mobilization of the bare line as a multi-faceted, representational form.

Susan Holbrook notes that, while paragrammatic composition ruptures accepted shapes and sounds of representation, it always finds itself “recuperated”35 back into a meaningful relation. Holbrook argues that the paragram reveals a faith in the “value of human communication”36—that is, a faith in convention. The paragram expands the possibilities for meaning-making, opening up conventions to reinterpretation while still relying on them to ground our understandings. For comics, like Fictive Funnies, the pun would not function without conventions for the reading of panels. Like any paragram, the comic presents the possibility for us to re-perceive practices of representation. The comic queries its own conventions: the panels are both points of focus and rupture; the linear sequence is also rerouted and split open; and the characters are also aware of their own narrative function. The paragrammatic pun offers a way of seeing again the panelogic of comics.

Nichol published Grease Ball Comics in 1970 through his Ganglia Press, printing it on both sides of a simple piece of paper and folding it in half. Unlike the first page of Fictive Funnies, which visually enacts the working of the pun through paragrammatic employments of the medium, this comic opens up multiple reading paths without directing interpretation. The comic embraces a blend of what are typically considered avant-garde, decadent, and postmodern characteristics. This blend of experimental approaches to communication finds itself expressed in Nichol’s understanding of Alfred Jarry’s notion of ’pataphysics (with one apostrophe). Jarry describes it as a fictional science that “will examine the laws that govern exceptions, and will explain the universe supplementary to this one.”37 Jarry’s concept was vehemently opposed to rationality and coherent meaning.

Christian Bök describes the distinctly Canadian approach to ”pataphysics (signalled hereafter with a double apostrophe)38—an approach that Nichol promoted—as a phenomenon “in which every text becomes a poetic device, a novel brand of ‘book-machine.’”39 Grease Ball Comics illustrates Nichol’s specific perspective on ”pataphysics, which he describes as follows:

it’s like I’m looking for hidden content [in the alphabet]—they’re like a doorway into another universe … —& that other world is really this world—it’s really this world in the most basic sense.40

Elsewhere, Nichol notes that

the way I tend to think of ”pataphysics is that very often you climb a fictional staircase that you know is fictional; you walk up every imaginary stair, you get to your imaginary window and you open your imaginary window, and there is the real world. You see it from an angle you would not otherwise see it from.41

For Nichol, and for this comic, the stacked, twisted, and disjointed reading paths foster a multiplicity of relations that nonetheless return to a meaningful interaction with the world. In contrast to Jarry’s initial model that stretches into the abyss of irrationality, Nichol models a more moderate, less radical, approach to ”pataphysics, one that tempers Jarry’s antagonism toward a presumed reality. Nichol employs ”pataphysics both to rupture reason and to recuperate it—to explore the ephemerality of a thought expressed in language. As Nichol notes,

an attention to words & letters, an attention to the surface details of writing, opens a ”pataphysical dimension. It is a dimension filled with short-lived phenomena, phenomena which we tend to think of as “merely” ephemeral and/or “on the surface,” the dimension of the coincident, a “universe supplementary to this one.”42

The ephemerality of such works is especially relevant to a discussion of comics, a medium often pulped rather than savoured. It is also a medium invested in the transformative surface, a space which can be divided and layered, shifting between surface and depth with the drawing of a line. In particular, Grease Ball Comics enacts the logical exploration of exceptions and supplementary universes, here evidenced through the structuring of multiple possibilities for seeing and reading the comic. Nonetheless, these exceptions or alternatives do not necessarily provoke unrestrained polysemy but draw attention to assumptions that impact our acts of interpretation.

On the front cover (Figure 10), Grease Ball Comics begins with panels that layer the thought balloon in one panel onto the thinker (Milt the Morph) in another panel. As in Fictive Funnies, the reader must choose between conventions—either reading in an orderly manner, left to right, top to bottom, or maintaining the presumed connection to the source of the thought. Arguably, reading conventionally might cause confusion, since the thought and then the following image of a castle with a white picket fence do not relate to each other clearly (especially since thoughts are typically ascribed to animate rather than inanimate things). On the other hand, putting the thought and thinker together by following the thought bubbles reveals a pun: the thought decrees that it is itself “insubstantial” and that communication is “divided,” two features enacted by the emptiness of the panel in which the thought resides and by the separation of Milt from his thoughts across two panels. The dividedness of the thinker from his thoughts goes beyond the panels, since his panel also appears to float on top of the other panels, layering narrative spaces upon each other. This suggests the further possibility that this thought does not even belong to Milt, but rather to another figure obscured underneath his panel. The interactions of these panels present the reader with several choices for interpretation.

The lower-left panel offers a clue for navigating this multifarious sequence of panels. Here, a second figure looks out and addresses the thinker (and reasserts the traditional reading path, left to right), asking, “Now that you have said what you came to say … What have you said?!” The question assumes that the thoughts have been heard, thereby affirming the conventional representation of thought as text in a thought balloon, while also offering a Babel-esque critique of their value. There is an oscillation between a recognition of the thought and a retraction of its worth. Similarly, the “you” seems to be directed at the figure in the foreground, but might still be connected to one obscured behind it. Furthermore, the critic may be addressing the author, since the character is thinking, not saying anything. Only the overall text generated by the creator might be said to “say” something. While the thought remains vaguely attributed to Milt the Morph, the presence of the critic affirms several roles and values surrounding communication between the panels and its figures. The layered panels hint at a ”pataphysical interest in both supplementarity and irrationality, whereby meaning is displaced and deferred across different representational frames for communication.

FIGURE 10 Front cover of bpNichol’s Grease Ball Comics (CURVD H&Z, 1983).

Things continue to unravel as we open the comic to the next page (Figure 11). At the top of the page is a speech balloon that says, “Everything shifts + you are part of that shifting!”—a statement that appears to describe the glimpses of shifting letters depicted in the central panels of the page. In the foreground, at the bottom of the left-hand page, we glimpse a corner of a figure’s head, whose eyes, nose, and smiling mouth suggest that it is again Milt the Morph. However, while the tail of the thought balloon points toward Milt, its distant and elongated location diminishes this connection and suggests that the speech might also belong to the panels underneath it. This tension between sources of speech attribution destabilizes the possible meaning of the comment. The split-source also raises questions about who or what is being addressed: the reader, the thinker, or the panels themselves? The only figure that we might expect to speak on the page is Milt, who seems to be looking out at the reader. By addressing the readers a>as “part of that shifting,” Milt highlights the participatory role of the reader. The frame for communication remains fluid, since layers of text seem to address characters within the panels as much as they might address spectators outside the panels. The panels seem to comment upon the condition of the reader during the act of reading the comic itself.

FIGURE 11 Inside cover page of bpNichol’s Grease Ball Comics (CURVD H&Z, 1983).

By standing outside the panels to comment on their qualities, Milt the Morph takes on the authorial function of a narrator in an ekphrastic narrative. The landscape in his eye inverts the pun in the phrase: “he has his head in the clouds”—a common gripe against daydreamers and distracted thinkers. Here, however, the use of the eye as a panel helps us to read the landscape, both on the previous page and on the facing page (Figure 12), almost as if his eye provides a literal window to his soul. Perhaps, here we are witnessing Milt the Morph living up to his namesake, the morpheme, by embodying the smallest units of meaning, the pictorial cues for another type of schematic language. The layering of panels means that they can be speaking to him as much as he can be speaking to us through the same speech balloon. Here, the ”pataphysical qualities of the comic become especially clear, since multiple story-worlds are superimposed upon each other, supplementing each other. The causal logic of the page is left open.

As on the cover, the critical speaker again undermines Milt’s statement by dismissively thinking “Aphorisms!!” While Milt has finally said something, the critic now seems to have diminished in size and in verbal stature, with his words now reduced to silent thoughts. Perhaps this reduction indicates an embrace of a secondary, derivative stature. Milt has become freed from the constraints of the panels, while the critic finds himself reduced in power. This second page, then, expands upon the panelogic of the first page by relocating the specific, relational values of the two figures.

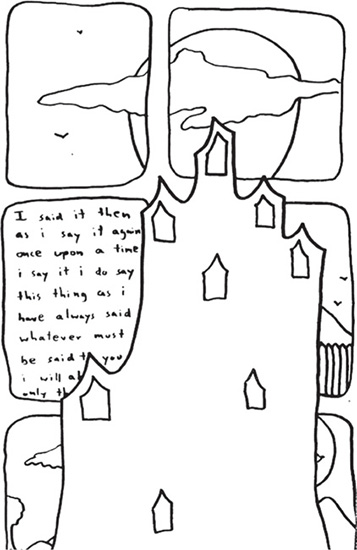

The second inner page (Figure 12) foregrounds other connections with the cover image. The small castle from the cover comes to dominate this page, quite literally expanding out of its series of panels. The background panels mimic the single one on the front page, the one that contains the castle, and the landscape has been expanded, multiplied, fractured, and overrun in the process of re-presentation. The castle seems to have superseded other panels, having broken out of its sequence to become a gestalt presence. At the same time, one panel offers the classic fairytale opening, “once upon a time …,” which clarifies this focus on the castle as a common locus of agents and events in the earliest, simplest stories from childhood. Now, the critic may also be reflecting upon the generic patterns of fairytales as aphoristic narratives, ending in a moral. The speaker becomes so concerned with saying something that the speaker becomes lost in a cyclical syntax reminiscent of writing by Gertrude Stein (one of Nichol’s mythopoeic saints, St. Ein). Again, here we see an interest in linguistic sequences rather than in narrative development. The panel suggests that the fairytale genre has perhaps become a discursive tower of Babel unto itself.

FIGURE 12 Inside back cover of bpNichol’s Grease Ball Comics (CURVD H&Z, 1983).

Arguably, the castle also resembles a hand or a bunch of calligraphic pens placed upon the page. The diagram resembles a right hand, perhaps the hand of the reader holding this particular page. This emphasis on the writing hand, reinforced by the handwritten panel, returns us to the notion of the author that has haunted the comic since Milt thinks his first thought. By placing the castle here, in a shape that connects to the hand of the reader holding the comic, the comic seems to invite the reader to take up a pen and participate in constructing the text on the page (the critic having already dispelled any concerns about saying something by saying nothing particularly significant).

This material extension of the comic also occurs through the qualities of its paper. The material qualities of the comic, as a nested series of flimsy pages, each folded in half, further reinforces the bleed-through of content from front to back, imitating the layering of panels on each page. For the comic, opening up the cover means opening up the various panels and their worlds—expanding them non-narratively to compound their possible relations. In a way, the reader reads down through the pages rather than across them, building a sense of material and narratological porosity. Furthermore, the “Steinian” approach to the opening lines of a fairy tale might represent the critic’s attempt to disrupt the aphorism as much as Milt’s attempt to write an aphorism. Here, the comic comes closest to narrative, and it seems to end in a circuitous beginning without direction.

On the back cover of the comic (Figure 13), a series of overlapped panels, including the critic and another figure, all spiral into the depths of the page by way of a conclusion without a dénouement. An angelic figure—whose body looks like a speech bubble, which also becomes a thought balloon—thinks an answer to an unspoken question about endings: “No! It’s just the end of this probable road!!” This statement affirms the conventional expectation that a narrative must have an ending, while also acknowledging that this story results in the ”pataphysical development of parallel, illogical worlds, each with its own multiple, narrative interpretations. In Grease Ball Comics, innovative strategies defamiliarize a conventional understanding of comics in order to reveal their possibilities for more varied styles of storytelling. By manipulating the relationships among the author, the thinker, the critic, and the reader, Nichol has refocused the medium upon the creativity inherent in structural connections between panels and their pages. Grease Ball Comics showcases constraints of the medium, while also exploring its reassuring possibility of another “probable road.”

FIGURE 13 Back cover of bpNichol’s Grease Ball Comics (CURVD H&Z, 1983).

Both of the comics that I have discussed rupture the conventions of the form so as to affirm a paragrammatic poetics and a ”pataphysical poetics. I would suggest that these comics also function as manifestos for what I call Nichol’s material poetics. By addressing the reader through narrative captions in Fictive Funnies and more directly through speaking figures in Grease Ball Comics, Nichol encourages the reader to take up the paragram of the pun, to become “a part of the shifting” in meaning. Such encouragement serves to motivate ongoing interrogations and renovations of the medium by future creators. These experimental comics emphatically embrace alternatives to the conventions of the genre, doing so in order to draw attention to these conventions, to defamiliarize them, and to grant the reader a critical distance from them. These comics present a revolutionary approach to the medium.43.

As an important figure in the rise of radical literatures in Canada, Nichol was keen to explore how visual, verbal, sonic, and tactile forms contributed to meaning, and he sought to open these features up across his oeuvre. Nichol is exceptional in his dedicated creation across a range of art forms, unlike most other creators’ more narrow focus on a specific medium. His comics draw out several of the experimental interests that have pervaded broader shifts under way in popular culture. As manifestos, these comics train readers in the panelogic of comics. They teach readers how to think through practices of recursivity. Such comics present an opportunity to move beyond the closure of sequential narrative, to enter into what Thierry Groensteen describes as “a dechronologized mode, that of the collection, of the panoptical spread[,] of coexistence …, of translinear relations and plurivectorial courses.”44 I would suggest that both the paragrammatic approach and the ”pataphysical approach to storytelling are allegorical. The paragrammatic approach focuses on the affordances of modalities that Nichol adapts to non-narrative ends. Fictive Funnies and Grease Ball Comics, among others, show bpNichol’s skill at rejuvenating comics, teaching readers to read them anew. Nichol’s comics are crucial documents that reflect a shift from the crisis in the later modernist avant-garde explorations of rupture to the early postmodern avant-garde emphasis on participation, multiplication, and indeterminacy.45 As manifestos, these comics continue to resound as calls to creative action.

1 Frank Davey, aka bpNichol: A Preliminary Biography (Toronto: ECW, 2012), 266, 270.

2 Jean-Paul Gabilliet, “Comic Art and Bande Dessinée: From the Funnies to Graphic Novels,” The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 467.

3 John Bell, Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe (Toronto: Dundurn, 2006), 100. See also Gabilliet, 467.

4 Christian Bök, “Nickel Linoleum,” Open Letter 10.4 (1998): 62.

5 bpNichol, Meanwhile: The Critical Writings of bpNichol (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2002), 241.

6 Linda Hutcheon, “The Glories of Hindsight: What We Know Now,” Re: Reading the Postmodern: Canadian Literature and Criticism after Modernism (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2010), 45.

7 Matei Călinescu, Five Faces of Modernity: Modernism, Avant-Garde, Decadence, Kitsch, Postmodernism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1987), 285.

8 Bell, Invaders, 143.

9 Hilary Chute, “Graphic Narrative,” The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature (New York: Routledge, 2012), 411.

10 See Patrick Rosenkranz, Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution, 1963–1975 (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2008), and Roger Sabin, Comics, Comix and Graphic Novel: A History of Comic Art (New York: Phaidon, 1996).

11 Călinescu, Five Faces, 120–125.

12 Călinescu, 276.

13 Călinescu, 292.

14 Chute, “Graphic Narrative,” 408. See also Alison Gibbons, “Multimodal Literature and Experimentation,” The Routledge Handbook of Experimental Literature (New York: Routledge, 2012): 420–434.

15 Nichol dedicates his collection to cartoonists Winsor McCay, Walt Kelly, Chester Gould, George Herriman, and Cliff Sterrett. Later, in 1983, he also self-published “After Winsor McCay: A memoir of reader/writer relations in the mid-60s” (Toronto: Ganglia Press, 1983).

16 Nichol reprinted nineteen strips of McCay’s in 1969 under the title “The Magic of Winsor McCay,” co-issued as Gronk 2.7/8 and Comics World #3. This issue included the following comics: 12 Little Nemo in Slumberland, 5 Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, 1 Little Sammy Sneeze, 1 A Pilgrim’s Progress. I am indebted to jwcurry’s bibliographic notes on this issue: https://flic.kr/p/bqFTUC.

17 For more information about McCay’s innovations and influence, see Joseph Witek, “The Arrow and the Grid: Creating the Comics Reader,” edited by Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester, A Comics Studies Reader (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009), 149–156.

18 See Katherine Roeder, Wide Awake in Slumberland: Fantasy, Mass Culture, and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCay (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014) for more on his mass-market modernism.

19 Paul Dutton, “bpNichol: Drawing the Poetic Line,” St. Art: The Visual Poetry of bpNichol (Charlottetown: Confederation Centre Art Gallery and Museum, 2000), 37.

20 Carl Peters (ed.), bpNichol Comics (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2002), 21.

21 Steve McCaffery and bpNichol, Rational Geomancy: The Kids of the Book-Machine: The Collected Research Reports of the Toronto Research Group, 1973–1982 (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1992), 122.

22 See Thierry Groensteen, The System of Comics, trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Hguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009). Groensteen offers several descriptions of panels and six interwoven functions of the frame (25–30; 39–57), all of which align with my presentation here.

23 Aaron Meskin, “Comics as Literature?” British Journal of Aesthetics 49.3 (2009): passim.

24 Elisabeth El Refaie, “Multiliteracies: How Readers Interpret Political Cartoons,” Visual Communication 8.2 (2009): passim.

25 Quoted in Peters, bpNichol Comics, 21.

26 Steve McCaffery and bpNichol, Rational Geomancy, 129.

27 Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: HarperCollins, 1994), 63–69.

28 McCloud presents “closure” as relatively straightforward (63–69), but in fact it involves complex non-deterministic cognitive processes.

29 McCloud, Understanding Comics, 160.

30 Nichol, Meanwhile, 18.

31 Gregory Betts, “Postmodern Decadence in Canadian Sound and Visual Poetry,” Re: Reading the Postmodern: Canadian Literature and Criticism after Modernism (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2010), 175.

32 The three-page comic, Fictive Funnies, is often erroneously labelled as solely authored by bpNichol and only a single page long. Stephen Voyce correctly reprimands several scholars for misattributing authorship to Nichol, but Voyce also seems to refer only to the first page as “the text” collaboratively created by a “synthetic authorial subject irreducible to either author” (n.30 293). McCaffery, in an interview with Peter Jaeger, has clarified the collaborative qualities of the text, which are not quite so “synthetic” as Voyce suggests. While this page is primarily “Barrie’s apart from a tiny inset frame in the bottom right corner” (Jaeger 83), McCaffery has drawn much of the rest of the comic, except for a few panels on the top of the next page, suggesting a dialogic, rather than synthetic, collaborative authorship. See Peter Jaeger, “An Interview with Steve McCaffery on the TRG,” Open Letter 10.4 (1998): 77–96.

33 See Mike Borkent, “Illusions of Simplicity: A Cognitive Approach to Visual Poetry,” English Text Construction 3.2 (2010): 145–164; and “Mediated Characters: Multimodal Viewpoint Construction in Comics,” Cognitive Linguistics 28.3 (2017): 539–563.

34 Steve McCaffery, “The Martyrology as Paragram,” Open Letter 6.5–6 (1986): 194.

35 Susan Holbrook, “FL, KAKA, and the Value of Lesbian Paragrams,” Tessera 30 (2001): 44.

36 Holbrook, “FL, KAKA,” 44.

37 Jarry quoted in bpNichol, Meanwhile, 353.

38 Christian Bök observes that “Canadian ”Pataphysics adds another vestigial apostrophe to its name [as opposed to the ’pataphysics begun by Alfred Jarry] in order to mark not only the excess silence imposed upon Canadians by a European avant-garde but also the ironic speech proposed by Canadians against a European avant-garde.” ’Pataphysics: The Poetics of an Imaginary Science (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2002), 83.

39 Bök, ’Pataphysics, 84.

40 Nichol, Meanwhile, 123.

41 Nichol, 333.

42 Nichol, 371.

43 Nick Sousanis’s excellent philosophical comic Unflattening (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015) responds to, and expands upon, some of the challenges and possibilities that bpNichol raises in these manifestos.

44 Groensteen, The System of Comics, 146–147.

45 Călinescu, Five Faces, 120–125 and 302–305.