The Exceptional Brain(s) of Albert Einstein

I feel like some relic in an old cathedral—one doesn’t quite know what to do with the old bones.

—LETTER FROM EINSTEIN TO PAUL EHRENFEST, September 1919

While everyone agrees that brains constitute the very embodiment of complex adaptive systems and that Albert Einstein’s brain was more complex than that of a housefly, nervous system complexity remains hard to define quantitatively or meaningfully

—CHRISTOF KOCH AND GILLES LAURENT, 80 years later

Three teams of investigators would dust off Harvey’s half-century-old photographs of Einstein’s brain, beginning with Sandra Witelson in 1996. Not surprisingly, each lead investigator (or first author, in the parlance of academic papers)—a physiological psychologist, a paleoanthropologist, and a physicist—would “see” a different brain. And although it was always the same brain, it can be argued that depending on the researcher’s perspective Einstein had (at last count) three very different and exceptional brains. For the last four studies published (to date) about Einstein’s brain, the teams did not directly study neural tissue embedded in celloidin blocks or mounted on microscope slides. They relied on photographs, which were the only way to observe the complex interrelationships of the brain’s gyri and sulci as they had presumably existed inside Einstein’s head during his annus mirabilis in 1905. Only Harvey’s meticulous black-and-white photographs could allow the teams to “reassemble” the brain’s premortem appearance from the three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle of 240 tissue blocks.

The “Parietal” Brain

When Harvey drove back to New Jersey from Hamilton, Ontario, he left the precious pieces (slides and tissue blocks) and photographs of Einstein with Sandra Witelson, who had received her doctorate in physiological psychology at McGill University. Her far-ranging interests had led her to study the neuroanatomy of language, sexual preference, handedness, and the differences between the brains of men and women. As a trailblazer in a male-dominated field of science, it is ironic that the then president of Harvard Larry Summers would refer to her research on neuroanatomical sexual differences as “one reason fewer women succeed in science and math careers.”1 One of Witelson’s overriding tenets was that “every brain is as different from another brain as every face is different from another face.”2 She meticulously reviewed the Einstein materials with particular scrutiny of five of Harvey’s original photographs. The death of her husband sadly delayed her study, but in February 1998 the manuscript was submitted to the venerable British medical journal the Lancet, which has been published weekly since 1823.3

“The Exceptional Brain of Albert Einstein” appeared in print (not as a research paper but under Lancet’s rubric, “The Department of medical history”) on June 19, 1999.4 Witelson conceded that “there was little knowledge about the cortical localization of cognitive function” but proposed that “the neurobiological substrate of intelligence may be facilitated by the comparison of extreme cases with control cases.” And when it comes to intelligence, it is hard to come up with a case that is more extreme than Albert Einstein. After skirmishing with existing limitations of knowledge about the neurology of genius, Witelson mapped out her core hypothesis—“the parietal lobes in particular might show anatomical differences between Einstein’s brain and the brains of controls.”

She dutifully noted that when Harvey placed the brain on the enamel pan of his Chatillon scale overhanging the autopsy table, it weighed in at 1,230 grams and was no different from her age-matched controls: “A large (heavy) brain is not a necessary condition for exceptional intellect.” Each hemisphere was one centimeter wider than that of the controls, making the brain more spherical. Brains, unlike footballs, are not usually symmetrical in an axial plane. Imagine cutting an undeflatable football (okay, forget the New England Patriots in the 2014 AFC Championship Game) lengthwise and exactly in the midline—both halves would match up precisely. That’s symmetry and not the case with human brains. Witelson claimed that Einstein’s brain was more symmetrical than the norm. True or false, this finding would make neuroanatomists and paleoanthropologists, such as Dean Falk, sit up and take note. The bilateral hemispheric conformation, or petalia, of most human brains (as opposed to other higher primates) lacks symmetry. The right frontal lobe and the left occipital lobe protrude in most right-handed people,5 and as Witelson would have it, Einstein was the exception to this rule.6

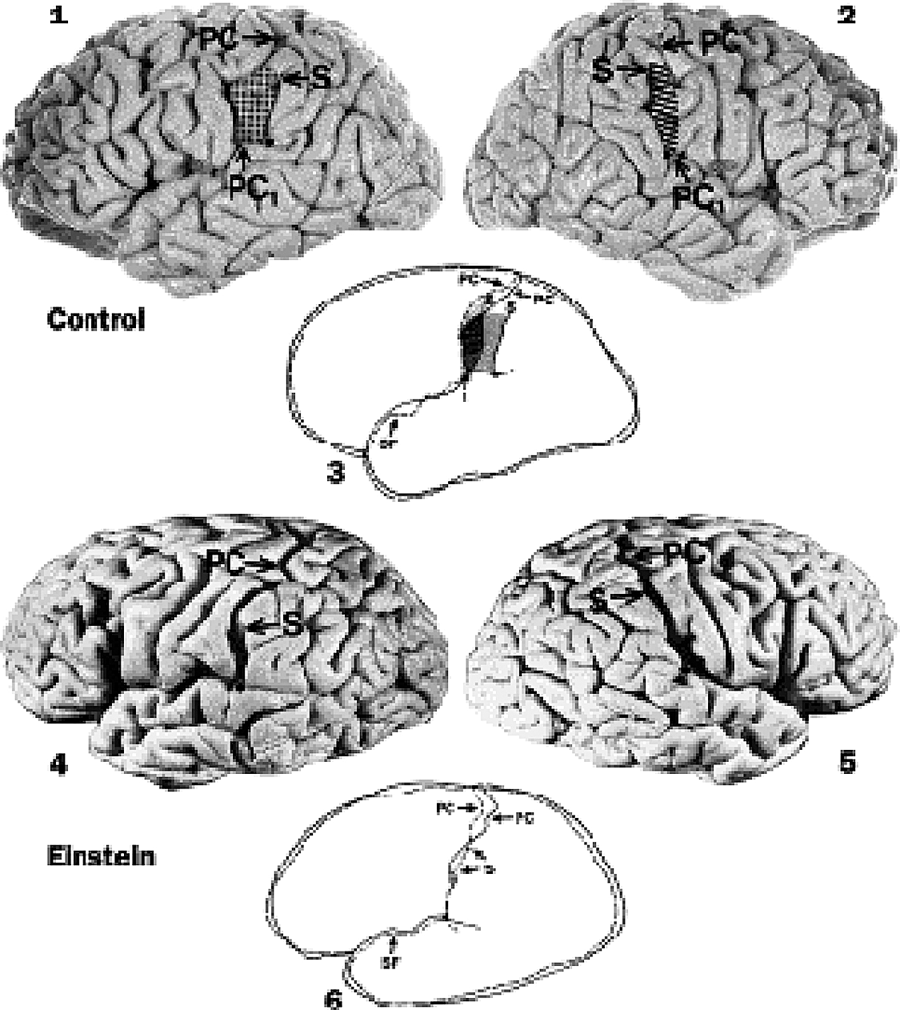

Most significantly, Witelson traced the meandering courses of the cortical fissures (sulci) of Einstein’s parietal lobes and found that a branch of the Sylvian fissure (separating the temporal lobe from the frontal and parietal lobes) was continuous with the postcentral sulcus, which serves as a line of demarcation between the primary sensory cortex and the rest of the parietal lobe (Figure 5.1).7 The anatomical implications of this confluence of sulci was the absence of the parietal operculum (a lid of cortical tissue folded over the underlying parietal lobe), a larger expanse of the inferior parietal lobule, and a “full” undivided supramarginal gyrus. She speculated that the “compactness of Einstein’s supramarginal gyrus within the inferior parietal lobule may reflect an extraordinarily large expanse of highly integrated cortex within a functional network.” Furthermore, the atypical anatomy of Einstein’s inferior parietal lobules might be linked to his exceptional intellect in “visuospatial cognition, mathematical thought, and imagery of movement.”8

Figure 5.1. Was Einstein’s “exceptional intellect” related to the “atypical anatomy” of his parietal lobes? As compared to the asymmetrical parietal opercula found in control brains (shaded and hatched areas in 3), Witelson found that Einstein’s brain lacked parietal opercula, had anterior displacement of the bifurcation of the sylvian fissure (SF) with resultant expansion of the posterior parietal cortex, and displayed unusual symmetry between his hemispheres in this region. (Reprinted from the Lancet, Volume 353, Issue 9170, Sandra F. Witelson, Debra L. Kigar, and Thomas Harvey, “The Exceptional Brain of Albert Einstein,” 2149–2153, 1999, with permission from Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10327-6.)

Five days later the eminent experimental psychologist Steven Pinker, writing for the New York Times, proclaimed the Lancet paper an “elegant study … consistent with the themes of modern cognitive neuroscience” and demonstrating that “every aspect of thought and emotion is rooted in brain structure and function.”9 Astonishingly, Witelson and her coauthors (her lab assistant Debra Kigar and of course, Thomas Harvey) had unlocked the secrets of Einstein’s variant cortical surface “using a pair of calipers.” Admittedly, Harvey had wielded the calipers four decades before Witelson could perform comparable measurements on the controls in her brain bank.

Time magazine’s appraisal was more cautious. Michael Lemonick, its senior science writer and himself the son of a physicist, wrote, “We know Einstein was a genius, and we now know that his brain was physically different from the average. But none of this proves a cause-and-effect relationship.”10

Once the popular press had its say, Witelson’s scientific peers took off their kid gloves and rigorously appraised her findings. Albert Galaburda questioned the provenance of the photos: “We are given no information to ascertain that the photos indeed came from Einstein’s brain.”11 Even today, no ironclad evidentiary chain exists to rebut this charge. All Einstein investigators past and present have relied on Thomas Harvey’s word as an honorable physician and man of science that the photos are originals (or copies) of the brain he removed on April 18, 1955. (Along the same skeptical lines, if you have doubts that Rembrandt van Rijn’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer currently on exhibit in Gallery 637 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the same one he painted in 1653, you are probably going to doubt the authenticity of the Einstein photos. Have faith!)

Galaburda, a cognitive neurologist who studied the anatomic lateralization of language in the brain, refuted Witelson by asserting that the right hemisphere “commonly” lacked a parietal operculum and that Harvey’s photographs “clearly show a parietal operculum on the left [hemisphere].” Witelson disagreed, saying that the cortical fold Galaburda identified as Einstein’s left parietal operculum was actually the postcentral gyrus.12 Both investigators possessed stellar academic credentials and had spent countless hours dissecting human brains. And yet they could not agree on whether Einstein lacked parietal opercula. This question would not be resolved until our study was published online in 2012.13 Admittedly, I’m biased … but how can I persuade you, Dear Reader, that we really settled this simmering controversy? (Hint: the five photographs in the Lancet article were not sufficient to answer many fine-grained anatomical questions.)

Before severing the Gordian knot of parietal opercula, I want to return to 1999 and the personal impact of Witelson’s findings. On June 18, 1999, I was fascinated by the New York Times’ headline—“Key to Intellect May Lie in Folds of Einstein’s Brain … So, Is This Why Einstein Was So Brilliant?”14 At the risk of repeating myself, most neurologists, myself included, deal with brain diseases, not with the “problem” of superior intellect. There are no ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, a kind of Linnaean system relied upon for medical billing) diagnostic codes for “genius,” and I have yet to see a patient referred for the chief complaint of “being too smart.” Nevertheless, Witelson’s groundbreaking description of Einstein’s cortex was irresistibly thought-provoking to a guy who spends a lot of time diagnosing and treating disordered brains. When the Dana Foundation put out a call for manuscripts on neurological topics in 2000, I pitched an account of what we had learned about Einstein’s brain and why it interests us so greatly. (This is a real cart-before-the-horse scenario for a medical school professor. I typically submit a completed manuscript to an academic journal and await the editor’s decision on acceptance—usually with revision or outright rejection. In the high church of academic publishing, it is quite unorthodox to submit a proposal sans manuscript on “spec.”) Walter Donway, the editor of the Dana journal Cerebrum, was intrigued, and I was off to the races. I didn’t know anything about Einstein and had never written a word about him (or his brain). I now had to confront Witelson’s world-renowned hypothesis of the crucial role played by Einstein’s parietal lobes.

As Witelson would have it, was Einstein a “parietal genius” by anatomical criteria? It’s a trifle overstated but a good question nonetheless. My search for an answer became a lot less straightforward when I read Macdonald Critchley’s classic monograph The Parietal Lobes, which cautioned that “the parietal lobe cannot be regarded as an autonomous anatomical entity. Its boundaries cannot be drawn with any precision except by adopting conventional and artificial landmarks and frontiers. Later it will also be seen that it is not possible to equate the parietal lobe with any narrowly defined physiological function. In other words, the parietal lobe represents a topographical convenience pegged out empirically upon the surface of the brain.”15 Anatomical imprecision aside, Critchley’s book was a high-water mark for the growing acknowledgment of the critical neurological (and psychological) roles of the parietal lobe. Critchley reminisced that “a visitor to the prewar neurological centres in Europe might be tempted to remember the Psychiatric Clinic of Vienna as a posterior parietal lobe institute.”16 Undoubtedly, classic presentations of right parietal lobe lesions in which patients ignored (parietal neglect) the left side of their environment or contended that their own paralyzed left arms belonged to other people piqued psychiatrists’ intellectual curiosity.17 Critchley’s take on the parietal lobes was very different from that of his predecessors, such as the Johns Hopkins Medical School neurosurgeon Walter Dandy, who twenty years earlier wrote that the “right parietal lobe (excluding sensory function of the paracentral region) has no known functions” and deemed the left parietal lobe “by far the most important part of the brain.”18 Neuroscience, no less than other learned disciplines, is subject to the ascendance of schools of thought, and Critchley’s groundbreaking reconsideration of the parietal lobe resonates to the present day in Oliver Sacks’s “richly human clinical tales,” which include an account of a woman (with a stroke of her right parietal lobe) who ate only from the right half of her plate, neglecting the left.19

Lesion case studies can only take you so far in understanding brain function. And Critchley reminds us that “the fallacy of confusing localization of sign-producing lesions with localization of function still needs reiteration.”20 Lest it be forgotten, in the case of Einstein, Witelson took the measure of presumably supranormal rather than defective parietal lobes. In a later chapter, I will sift through the evidence for Einstein’s distinctive brand of creative cognition, but with the anatomical facts we have in hand, I don’t think we can reduce Einstein’s core competencies to parietal lobe physiology. For now I will simply say that if we agree with cognitive scientist Marsel Mesulam’s analysis of the posterior parietal cortex as pivotal in integrating spatial information received via all our senses,21 it becomes difficult to envision Einstein’s parietal lobe as the most crucial element in the creation of his revolutionary theoretical constructs. Our senses cannot detect the curvature of space (as in the theory of general relativity) or the infinitesimal changes in time and dimension that occur with the velocities encountered in daily existence (as in the theory of special relativity). Lacking direct sensory access to length contraction/time dilation at nonzero velocity and curvature of space, from 1905 to 1915, Einstein relied on thought experiments played out in his imagination or, using the terminology of cognitive neuroscience, in his global neuronal workspace.22 As a neurologist whose occupation is to locate and treat abnormally functioning parts of the brain, I can assure you that currently imagination and global neuronal workspace do not readily localize to specific brain regions, including the parietal lobe. Neuroscience progresses in fits and starts but it is inexorable, and the specific “address” of a neural network underlying the creativity of an Einstein may yet be discovered.

By the summer of 1999, Sandra Witelson’s hunch about the starring role played by Einstein’s parietal lobes seemed vindicated. Steven Pinker agreed with her findings and assured us that “the difference between the inferior parietal lobules of Einstein and of us mortals is not subtle.”23 She was lionized and ascended to academic Valhalla—an endowed chair—when she became the inaugural Albert Einstein/Irving Zucker Chair in Neuroscience (the donor, Mr. Zucker, was kind enough to give Einstein top billing) a mere four days after her Lancet paper! Witelson wagered heavily on the primacy of the parietal lobes and stated that she was “guided theoretically on the basis of current information of cortical localization of cognitive functions.”24 The subsequent appreciation of the massive evolutionary increase of cortical connectivity in humans25 has increasingly led us to question the doctrines of “pure” cortical localization. Like it or not, most scientific hypotheses (or the way we frame our scientific questions) are biased, and Witelson found the evidence she was looking for in five of Harvey’s photographs (Figure 5.2).26 With these in hand, she wrote that “the gross anatomy of Einstein’s brain was within normal limits with the exception of his parietal lobes.”27 As Dean Falk and I came to later appreciate, when you look at two-dimensional photographs of a three-dimensional object, such as Einstein’s brain, additional photographic views are invaluable to most accurately reconstructing the object in the mind’s eye. Did Witelson have more than the five photographs she published? You bet she did. Did she weigh all of them in her final scientific conclusions? We’ll never know but if she did, the beautiful fit of the five canonical views and her preconceptions about the parietal lobe overshadowed them.

Could the anatomy of Einstein’s parietal lobes differ in isolation from the rest of his brain? Did Harvey take more than five photographs during Einstein’s postmortem, and if so, did they hold any surprises?

Twelve years would pass before Dean Falk and I could even hope to find the answers to those very questions.

The Brain with Extraordinary Prefontal Cortex … and More

As recounted in the first chapter, Dean Falk sent me an e-mail seven years after the publication of “Dissecting Genius” with an intriguing request: Could I point her to photographs with “various views (including a frontal view)” of Einstein’s gross brain that were not just those shown in Witelson’s paper and her rebuttal of Galaburda’s criticisms?28 As it turned out, I couldn’t accommodate her request for another three and a half years, but nevertheless, an improbable collaboration was launched.

Figure 5.2. Witelson selected five of Harvey’s 1955 photographs of Einstein’s brain (A, both hemispheres from above; B and C, left and right hemispheres; D, underside of the brain, cerebellum, and brain stem; and E, medial surface of the left hemisphere) to demonstrate a relatively spherical brain, moderate age-appropriate atrophy, and a lack of parietal opercula demarcated by the confluence of the postcentral sulcus and posterior ascending branch of the Sylvian fissure (see arrows, B and C). (Reprinted from the Lancet, Volume 353, Issue 9170, Sandra F. Witelson, Debra L. Kigar, and Thomas Harvey, “The Exceptional Brain of Albert Einstein,” 2149–2153, 1999, with permission from Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10327-6.)

To better understand Dean’s perspective and motivation, let’s dispense with her formidable academic bona fides—she’s senior scholar at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and a professor (and former chair) of anthropology at Florida State University. She is a paleoanthropologist with a particular interest in the evolution of the human brain—the subspecialty of paleoneurology. When confronting neurologic disease, we neurologists will infrequently review skull x-rays to screen for a fracture (in cases of head trauma). To examine the brain inside the skull, we rely on tests (CAT scan, MRI, or cerebral angiography) that visualize soft (neural) tissue. Paleoneurologists’ “patients” may have died more than three million years ago, and needless to say, only the bones remain. Without a brain to directly examine, paleoneurologists, who refer to the skull as a braincase, study the markings on the inner table of the skull with latex endocasts—and now CAT scan–derived virtual endocasts—that characterize the surface neuroanatomy and size of ancestral hominid brains.29

Given her expertise in paleoneurology, Dean was very familiar with the challenges of neuroanatomical analysis in cases lacking a brain to dissect or to neuroimage. In the case of Einstein, the challenge was to map, with unprecedented detail, the entire cortex of a brain that had been divided into 240 blocks more than half a century earlier. In Dean’s words, “Sulci may still be identified and interpreted from the extant photographs of Einstein’s whole brain, in much the same way that cortical morphology is observed and studied on endocasts from fossils by paleoneurologists.”30

As fascinating as the study of Einstein’s brain would turn out to be, it does not qualify as a day job. Dean’s real job description runs the gamut from teaching Florida State University undergraduates enrolled in ANT 2511—Introduction to Physical Anthropology and Prehistory—to making and describing latex and virtual endocasts of the brain of a new and recently extinct species of human, Homo floresiensis (the so-called hobbit due to a diminutive stature of three to three-and-a-half feet), discovered in Liang Bua, a cave in Indonesia.31 The hobbit “is now considered the most important hominim fossil in a generation.”32 Make no mistake, Einstein was a detour from Dean’s career path of innovative academic excellence in paleoanthropology. (And for that matter, I keep the wolf from the door by seeing patients and teaching neurology to medical students and residents.) There are no Einstein-research grants, and what we accomplished was cobbled together on our own time, with sweat equity. This was “curiosity-driven research”33 at its purest and most unmarketable. You can’t monetize the study of Einstein, but the exhilaration of scientific discovery was more than sufficient compensation for us both.

By January 2008 Dean’s search for any additional photos Harvey took in 1955 (if such existed, and that was not a foregone conclusion) had reached an impasse. Elliot Krauss replied that “Dr. Harvey did not give me the photos,”34 and “Sandra Witelson never answered any of my communications.”35 (Dear Reader, as you may have gathered by now, scholarly altruism and selfless collegiality are not leitmotifs in this tale of Einstein’s brain.) Undeterred, Dean announced that “having soldiered on, I now have a short paper on Einstein’s brain that is trying to find a home.”36

And find a home it did—in Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience.37 By virtue of its subspecialized subject matter, this intriguing journal is not destined to reach a wide audience but, emblematic of Dean’s philosophy of getting scientific research into the hands of interested scholars and the public alike, the article was online and open access. More critically, she demonstrated the wealth of new information that could be gleaned from the five grainy postage stamp–sized brain photos that had been reproduced in Witelson’s article a decade earlier.38

Even for an accomplished neuroanatomist, this was not as easy as it looked. Dean had to run the gauntlet of accusations of practicing phrenology and cope with the anatomical limitations of mapping the brain’s sulci (furrows), which “usually do not correlate precisely with the borders of functionally defined cytoarchitectonic fields.”39 (In other words, specific areas of gross brain anatomy do not necessarily match up neatly with the microanatomy. For example, you can have motor neurons firing happily away in the sensory cortex.40) Dean knew that “gross sulcal patterns have been associated with enlarged cortical representations that subserve functional specializations in mammals including carnivores.”41 And that begged the question: Could Einstein’s functional specializations be associated with variant cortical anatomy?

Figure 5.3. Falk identified the cortical knob (shaded convolution labeled K), which was an enlargement of Einstein’s right hemispheric primary motor cortex. This omega-shaped “bend” of cortex has been reported in right-handed string players. It abuts the central sulcus, which marks the boundary between the frontal lobe and the parietal lobe. (Dean Falk, “Photographs of Einstein’s brain that were taken in 1955, adapted from Witelson et al. [1999b],” in “New Information about Albert Einstein’s Brain,” Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience 1 [May 2009], https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/neuro.18.003.2009.)

Even with limited photo documentation at hand, Dean found two anomalies that set Einstein’s brain apart. What Dean saw (and what went unreported in Witelson’s Lancet paper) was a “knob-shaped fold of precentral gyrus,” or “omega sign”42 on the surface of Einstein’s right frontal lobe (Figure 5.3). The precentral gyrus is the primary motor cortex controlling movement of the opposite side of the body. The cortical knob that Dean had observed corresponded to the portion of the motor cortex that subserved the vast repertoire of Einstein’s left hand movements. As Louis Pasteur famously remarked, “In the fields of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind,” and the oxbow-shaped extension of Einstein’s precentral gyrus pictured in the superior and right lateral views of Witelson’s first figure (Figure 5.2)43 “jumped off the page” for Dean, who was well versed in the recent literature defining this cortical landmark. It must be conceded that when Witelson began to pore over Harvey’s photographs in 1996, the classic reference localizing the motor hand area to the precentral gyrus had not been published.44 While training her sights on Einstein’s parietal lobes, the motor cortical knob located in the frontal lobe was likely not on Witelson’s radar.

You may well ask what the cortical knob or omega sign has to do with theoretical physics. Is it an anatomical “secret handshake” that identifies physicists? As far as we know, it’s not. (Note to self: with a little funding and a bunch of physicists willing to spend ten minutes or so in an MRI scanner—the question could easily be resolved.) What we do know is that the omega sign is an anatomical landmark for musicianship! When three-dimensional MRI images of professional musicians’ brains were compared with those of nonmusicians, the musicians had a higher incidence of clearly visible omega signs. Moreover, the brains of string players could be distinguished from those of keyboard players. The omega sign occurred significantly more often in the left hemisphere of keyboard players, whereas the preponderance of omega signs in string players appeared in the right hemisphere.45 For the moment lay aside Einstein’s superpower of theoretical physics and recall that he was an enthusiastic and accomplished violinist who delighted in impromptu duets with accompanists ranging from neighbors to Queen Elizabeth of Belgium. The pitch emanating from the precise fingering of Einstein’s left hand on his violin’s fingerboard presumably began with activation of his right cortical knob. Was Einstein born with this particular cortical variation, or was it acquired as his brain “rewired” with hours of practice? This profound question of nature versus nurture will recur incessantly but will not be resolved by our study of Einstein’s brain. Suffice it to say that Dean Falk’s identification of Einstein’s cortical knob was further proof of concept that brain structure is not entirely independent of brain function. (Disclaimer: this is not a prospectus for neuroanatomical mind reading or a twenty-first-century iteration of phrenology.)

Dean’s other finding regarded the location of Witelson’s “missing” parietal opercula. As organisms ascend in phylogenetic complexity of the central nervous system to become more “brainy,” they (or rather natural selection) need to create more and more room for the cerebral cortex. One anatomical pathway is to fold and refold the cortex in on itself and maximize the cortical surface within the confines of a rigid “box”; that is, a bony skull. Opercularization is an example of this folding process in which expanding portions of frontal, parietal, and temporal lobe cortex fold over a patch of underlying insular cortex. Opercula (from Latin) are “lids,” and an apt comparison would be to imagine closing your eyelids over your eyeball. In the parlance of neuroanatomy, your upper eyelid would serve as a fold of parietal lobe cortex and your lower lid as a fold of temporal lobe cortex. Both lids would resemble the opercula covering the submerged patch of cortex known as the insula. Although Dean and Witelson did share common ground in their assessment of Einstein’s “extraordinary parietal substrates,”46 they parted ways in their analyses of the parcellation of parietal cortex. The proximity and connectivity of those parcels undoubtedly have implications for brain function, and what at first glance may seem to be an exercise in anatomic hairsplitting may help to explain how one part of the brain “talks” to another part.

Dean had enough anatomical evidence to assert that Einstein’s right and left insula were covered by opercula, but a crucial prop for her argument would be to determine whether the posterior ascending limb of the Sylvian fissure was continuous with the postcentral inferior sulcus or whether the two sulci were separated. Based on the five photographs in Witelson’s figure 1,47 Dean had no choice but to fall into line with Witelson’s conclusion that the two sulci were confluent. Except they weren’t … and it would take us three years to find that out.

“New Information about Albert Einstein’s Brain” gave further notice that “the gross anatomy of Albert Einstein’s brain in and around the primary somatosensory and motor cortices was, indeed, unusual.”48 This six-page study of portions of two lobes of Einstein’s brain was a warm-up exercise for Dean. She would run the table in 2012.

“Dear Professor Falk, I am pleased to let you know that your paper has now been accepted for publication in Brain …”49

For an academic facing the dilemma of “publish or perish,” there are no sweeter words after submitting a manuscript than “has now been accepted.” Our paper had three authors—Falk, Noe, and myself—but in the time-honored protocols of scientific publication, the editor in chief, Alastair Compston, would deliver the good or bad news to the first author, Dean Falk. After Dean and I prevailed upon Adrianne Noe to let us examine the contents of the late Thomas Harvey’s Einstein archives at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) on September 12, 2011, Dean spent months reviewing my digital copies of dozens of Harvey’s original autopsy photographs (eventually, fourteen would be published). She meticulously identified and rendered pen-and-ink tracings of every gyrus and sulcus visible in the pictures and compared them to the standard atlases of normative human cortex.50 Anatomical nomenclature had changed a bit in the half century since Harvey had labeled cortical landmarks on his photos, presumably for a paper on Einstein’s gross anatomy (that he would never write as a first author). So Dean had to dispense with the obsolete terminology of radiate sulcus and replace it with the up-to-date inferior frontal sulcus. As we shall see, she found some sulci that remain unnamed to the present day. For her prodigious efforts, Dean unquestionably was the first author of our paper, and Adrianne was designated as the last (or senior author), who frequently is “a member of the institution behind the research” (in this case the NMHM).51 I was comfortably ensconced as second author in the limbo of academic attribution—“What exactly was your contribution to this manuscript, Dr. Lepore?”—that exists between first and senior authors on the paper’s heading.

By April 10, 2012, a detailed paper had been prepared, and in her letter (with manuscript attached) to enlist Adrianne Noe as a coauthor, Dean, in the understated tone of informal scientific communication, mentioned that “the brain is extremely interesting, as you will see.”52 (Another note to self: as Dean well knew in this age of scientific ballyhoos, understatement is in very short supply. For my money, the reigning champion of scientific bon mots was, “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing that we postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material,” drily intoned by James Watson and Francis Crick when they communicated the discovery of DNA in a two-page paper.53)

Although light-years away from the Nobel Prize–strewn scientific Elysian Fields of Watson and Crick, in the midst of our exhilaration, we came face-to-face with a universal problem of scientific authorship: What journal do we submit our manuscript to? This was not a straightforward choice for denizens of three very different academic worlds—Falk (PhD in anthropology), Lepore (MD with board certification in neurology), and Noe (PhD in history). Typically, I would publish in the journal Neurology, while Dean would reach her audience of academic peers in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. For the Einstein paper, we needed a journal that could reach across the boundaries of academic disciplines and provide a sense of neuroscientific history that could encompass the brain of a genius who died in 1955 (and a large international readership would be nice, too). Dean, a member in good standing with the sorority/fraternity of neuroanatomists, made discrete inquiries of Albert Galaburda, the formidable and perceptive critic of Witelson’s Lancet paper.54 After some “background checking,” he advised that we “might submit our article to the journal Brain.”55

Brain, or more properly Brain: A Journal of Neurology, was first published in 1878 and is the oldest continuous English-language learned journal of neurology. The term neurology (or neurologie, as it was coined by Thomas Willis in 1681) originally applied to “the cranial, spinal, and autonomic nerves, as differentiated from the brain and spinal cord.”56 Over time neurology would come to encompass the study of the entire nervous system in health and disease (and I’m expected to apply this particular area of medical knowledge when patients come to see me). The explosion of neurological knowledge over the course of three and a half centuries expanded the subject matter of Brain, which by 2008 included “behavioural neurology, clinical-pathological correlation in the dementias and neurodegenerative and inflammatory brain disease, movement disorders, neurogenetics, epilepsy, nerve and muscle disease, the pathophysiology and modelling of disease mechanisms, and definitive case series that describe patterns of neurological disease or newly identified disorders.”57 One-off articles, such as our study of Einstein’s brain, had their own category—“Occasional Papers”—that was irregularly published.

Needless to say, we strongly felt our paper was both of compelling interest and neuroscientific merit. (Don’t all authors feel that way?) Despite the rigor of our scientific approach and the uniqueness of the rediscovered “lost” photographs of Einstein’s brain, our paper was off the beaten track for mainstream clinical neuroscience … and we were asking to be published in what is arguably the highest-profile neurology journal in the world. If I can invoke a metaphor bridging C. P. Snow’s “two cultures,” seeing your paper appear between the baby-blue covers of a monthly issue of Brain is like the exhilaration of a short-story writer whose work appears in the New Yorker. (To provide a little more perspective, the New Yorker turned down fifteen poems, seven short stories, and an excerpt of The Catcher in the Rye of no less a literary icon than J. D. Salinger!) Neither of these publications suffers fools gladly, and their reviewers make the classical underworld’s guardian, the three-headed Cerberus, look like a lapdog.

Besides setting our sights high, we had two additional problems—the length of our paper and institutional attribution. Our manuscript was over eleven thousand words in length. For a scientific publication, you might as well be submitting a rough draft of War and Peace, and most scientific editors consider such length to be a personal affront as they sharpen their red pencils. (Okay, I’m dating myself. Now editors use Microsoft Word document highlighting tools.) The editors will invariably and sanctimoniously protest that shortening your manuscript frees up more publication room for other important scientific papers. (In one of my recent reveries, I envisioned Herman Melville bringing a handwritten copy of Moby Dick to a medical journal editor and being brusquely advised to cut out the literary superfluities, such as dramatic foreshadowing, details of life aboard a Nantucket whaler, Biblical symbolism, etc., and go straight to the part where Ahab harpoons the White Whale).

With the exception of Norman Geschwind’s two-part, 116-page magisterial article on the “Disconnexion Syndromes in Animals and Man,”58 papers in excess of eleven thousand words simply do not get printed on the hallowed pages of Brain in the modern era. Geschwind’s paper was legitimately paradigmatic for our clinical understanding of the brain’s critical internal wiring “circuits” (which we now term the connectome). Our modest study was not even remotely in this class, but one could hope. Would Alastair Compston, a soon-to-be Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) and the immensely erudite editor of Brain, cut our manuscript to shreds or worse, simply reject it? In other words, would we go out with a whimper or a bang?

One of the supreme paradoxes in our pursuit of Thomas Harvey’s collection of Einstein artifacts was that the curating institution, NMHM, deliberately suppressed news of its acquisition of “lost” Einstein brain photos and microscope slides in June 2010. After Dean and I studied and photographed the Einstein archive (now occupying eight boxes) on September 12, 2011, we were taken aside by NMHM director (and our future coauthor) Adrianne Noe, who requested that “additional access or publication” of our Einstein findings would “not [be] occurring until after our May 2012 opening” of the new NMHM facility.59 Aside from my slack-jawed astonishment that this 149-year-old museum chose to hide its most high-profile (after the Lincoln assassination bullet) acquisition, Dr. Noe’s request for institutional anonymity created yet another stumbling block in the way of our submission to Brain.

At Adrianne’s behest Dean and I were now in the unenviable position of being unable to say just where in space and time the lost treasure trove of Einstein materials was archived. And so, the first draft of the manuscript submitted to Brain somewhat enigmatically reported that Dr. Harvey’s estate was “curated by ‘Institution X’ in 2010.” To compound our credibility problems, a PBS NOVA Science Now documentary titled “How Smart Can We Get” was in production in the latter part of 2012, and of course we had to tell our producer/director, Terri Randall, that we could not divulge where our research materials resided.60

Well, Reader, you know our paper got published, and the documentary aired on October 24, 2012 … but in the spring of 2012, however, the outcome hung very precariously. Declaring no known institutional attribution for our primary source research materials was tantamount to telling the editor and reviewers that the Einstein photographs were situated somewhere in Atlantis, Shangri-la, or the Big Rock Candy Mountain. Taking Adrianne at her word, the identity of the NMHM as the home of the Einstein materials could only be openly acknowledged when the museum celebrated a Grand Opening Open House on May 14, 2012. By mid-May, the reference to Institution X was expunged from our manuscript, and the NMHM was properly cited.61 Crisis averted … except for one trifling detail—at its grand opening in Silver Spring, Maryland, the NMHM did not acknowledge the on-site presence of its Einstein collection!62

As we came to fully appreciate, anything about Einstein will induce a media feeding frenzy. Alastair Compston was well versed in the care and handling of something (neurologically) new under the sun and wisely imposed a prepublication embargo on our findings until 00.01 hours GMT on November 16, 2012. Our online paper duly acknowledged the NMHM as the repository of the Einstein materials that had vanished when Harvey packed his bags and left Princeton Hospital in 1960.63 And so, buried in the fine print of the introduction of our paper, the NMHM backed into an announcement of its landmark acquisition.64 Clearly, I have never been savvy about institutional public relations, but in stark contrast Einstein’s brain was literally front page news when the Mütter Museum was given forty-six microscope slides from Einstein’s brain (compared to the 567 slides and dozens of photographs donated to the NMHM) on November 17, 2011. The announcement, along with a full-color reproduction of a specimen slide and its donor, made the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer the very next day.65 Eschewing something as prosaic as a press release for the scientific and lay press, the NMHM—a taxpayer-funded institution—after two and a quarter years informed John Q. Public of its ownership of five and a half linear feet of Einstein materials … not with a media blitz but by announcing the sale of an app! In collaboration with the software developer Aperio, the NMHM scanned and digitized 350 of its neuroanatomical images. The announcement was made on September 25, 2012, and would-be researchers or other interested parties could thenceforward purchase the interactive Einstein Brain Atlas app from iTunes for $9.99.66 It has since been deeply discounted at $0.99, and I suspect this may reflect the growing dismay of Tiger Moms who forked over $9.99 and realized junior was interacting with digitized pieces of Einstein’s brain and not the anticipated bold graphics of “My Baby Einstein,” which somehow got lost in the confusion of the app store. (Apparently, even app store economics are not removed from the raging controversy of nature vs. nurture.)

The NMHM eventually got around to a press release—“Never Before Seen Photos and ‘Maps’ of Albert Einstein’s Brain Go on Display at Medical Museum in Maryland”67 over four months after our paper was published online. Confounding factors of institutional attribution and manuscript length aside, Brain (and its publisher, Oxford University Press) assigned noteworthy neuroscientific significance to our discovery and analysis of the unpublished photographs. The “less is more” philosophy of manuscript editing was held in abeyance! For example, rather than abbreviate the anatomical names for all the sulci, we were instructed to use full names throughout the text, insert the abbreviations with accompanying full names in the figure legends, and devote table 1 to alternate abbreviations and names of sulci.68 Table 1 alone contained a key for ninety-seven anatomical abbreviations. Dean knew the reader would be inundated with anatomical minutiae but felt that, in the name of clarity (and the limitations of short-term memory), redundancy of these terms throughout the article was essential. This came with the significant editorial cost of increasing the page space of our article. Alastair Compston and his scientific editor, Dr. Joanne Bell, clearly wanted the most definitive and comprehensive analysis to date of Einstein’s cortical neuroanatomy to be recorded in the pages of Brain. Dean was encouraged “to err on the side of too much information than not enough.”69

Feeling as if we had entered an alternate editorial universe in which “length is strength,” we complied with alacrity. The paper topped out at twenty-four pages, and the glossy blue cover of the April 2013 issue was emblazoned with a collage composed of six of Dean’s marvelous color tracings of the brain photographs and a portrait of an atypically formal Einstein attired in a wing collar and cravat. In his editorial Compston commented on the prospect that “variation and asymmetry in gyral and sulcal patterns and hemispheric architecture may also reflect advantages conferred on the individual in terms of cognitive performance.” He then went a step further and concluded that “in so far as gross anatomy can illuminate the matter, Einstein did have a better brain than those who still struggle conceptually with E = MC2.”70

Was the conclusion that Einstein had a “better brain” the intent of our research, or was Compston overreaching? By way of an answer, let me shed further light on the discovery of the extraordinary neuroanatomy (and its implications) described in those twenty-four pages.

During the fall and winter of 2011–2012, Dean devoted months of intensive study to the previously unknown or missing photographs that we had brought back from the NMHM. The key to our unprecedented cortical findings was intense scrutiny of the multiple views of the brain that Harvey had captured in the spring of 1955. Fourteen of the photographs enabled us to “describe the entire cerebral cortex.” This was a lengthy process, as Dean had to “visually rotate between different views of Einstein’s brain to make sure that my identifications were consistent from view to view.” She had been doing this kind of demanding visuospatial work since her undergraduate days at the University of Illinois (Chicago Circle, as it was then called), when she wrote her honors thesis on the evolution of brain size.71 Her expertise notwithstanding, after “months of intensive study,” Dean realized that she was “staring at the ceiling at night and seeing sulcal patterns.”72 The upshot was that we “identified the sulci that delimit expansions of cortex (gyri or convolutions) on the external surfaces of all the lobes [my italics] of the brain and on the medial surfaces of both hemispheres.”73 With this comprehensive and detailed analysis of Einstein’s surface neuroanatomy accomplished, we could compellingly demonstrate that the external cortex (including medial surfaces not visible in undissected brains) of every lobe (frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital) of his brain was unusual.

Before proceeding any further, a thought uppermost in my mind is, “How many readers of my account of the ‘search and rescue’ of Einstein’s brain have more than a passing familiarity with neuroanatomy?” Not many, I suspect. Accordingly, I will tailor my description of his cerebral morphology to members of my imagined/hoped-for audience who enjoy the Science Times section in Tuesday’s New York Times or anything written by the late Oliver Sacks (Disclaimer: whatever the merits of this book may be, they fall far short of Oliver, even when he was having a “bad writing day,” which I don’t think ever happened.) A related point is that certain types of dry scientific jargon will suck the oxygen out of the fragile atmosphere that surrounds an interested audience. Stephen Hawking’s editor warned him that he would halve his readership for every equation in A Brief History in Time, and so Hawking included only one: E = mc2.74 By the same token, reading too much descriptive cortical morphology will deaden your senses and instantaneously induce REM sleep. To avoid that pitfall, I will guide you through the most fascinating and perplexing aspects of our anatomical study. For those hardy souls who want to embrace the totality of our findings, our twenty-four-page paper awaits you.75

Most striking was his highly unusual right frontal lobe in which the middle frontal region was cleaved into two distinct gyri by a relatively long midfrontal sulcus. Where “standard issue” human frontal lobes have three gyri, Einstein, with his anomalous divided gyrus had four! (See Figure 5.4.76) This extra frontal gyrus suggested the expansion of Einstein’s prefrontal association cortices. Dear Reader, before going any further, I implore you to regard this startling variation of anatomy strictly as a fascinating example of structural biology and not a surrogate for Einstein’s intellect. If the unique neuroanatomy I have begun to outline suggests a tangible link to Einstein’s profound grasp of our universe, so be it … but always remember that not a shred of scientific evidence exists today that will allow us to bridge the explanatory gap between brain and mind. As a clinical neurologist, I frequently try to connect straightforward but far-from-simple functions (such as vision) with parts of the brain (such as the occipital lobe). This is known as localization, and it is standard operating procedure when we try to diagnose and treat brain diseases. This approach is not so useful with problems posed by the most complex parts of the brain, such as the frontal lobe. In the words of John F. Fulton, one of the greatest researchers on the functions of the frontal lobe, “In approaching the functions of the frontal association areas one is brought face to face with activities which are difficult to describe in physiological terms.”77 As a working neurologist, I’m in good company when I concede that I can’t tell you exactly what the frontal lobes “do.” If the functions of average frontal lobes ascend to the empyrean heights of our “gnostic, mnestic, and intellectual processes,”78 then in order to grapple with the implications of Einstein’s abnormal frontal neuroanatomy (to quote Jaws), neuroscience is “gonna need a bigger boat.” Lacking such a “bigger … [connectome mapping? functional neuroimaging?] … boat,” I will return to the new anatomical findings “hiding in plain sight” on Harvey’s old photographs.

Figure 5.4. Einstein’s “extra” frontal gyrus is clearly visible in Harvey’s original 1955 photograph (with his sulcal labels) of Einstein’s right hemisphere. With covering meninges removed, the exposed cortical surface shows four (rather than the usual three) midfrontal gyri. If you’re counting, midfrontal gyri number two and number three are to the right and left, respectively, of the labeled midfrontal sulcus (Mid. frontal s). Number one lies to the right of number two, and number four is to the left of number three. (Harvey Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine.)

Dean had been aware of Einstein’s omega sign, the knob-shaped expansion of his right precentral gyrus, since 2009,79 but we now had four additional photographs to confirm this finding.80 It is said that in life you can’t be too rich or too thin, but in scientific research you can’t get too much confirmation from (in our case, photographic) data. One photograph beautifully demonstrated that Einstein’s cortical knob was larger on the right precentral gyrus and smaller on the left (Figure 5.5).81 This fit nicely with the previously cited study of larger cortical knobs found in the right hemispheres of string instrument players.82 As an aside, we have a great deal more to learn about the primary motor cortex that resides in the precentral gyrus. The classic Wilder Penfield map of the motor homunculus (Figure 3.1)83 that correlates hand and finger control with a specific portion of the precentral gyrus about two-thirds of the way between the Sylvian fissure, which sets the uppermost boundary of the temporal lobe, and the “top” of the hemisphere is overly simplistic. About one-quarter of the total length of the precentral gyrus is devoted to the hand and the fingers (elongated segments of right and left precentral gyri control the left and right hands, respectively). When Penfield stimulated the hand and fingers portion of the primary motor cortex of awake patients undergoing epilepsy surgery, he found that up to five volts applied via bipolar electrodes elicited flexion and extension of the contralateral hand and fingers. An important lesson for clinical localization is that the primary motor cortex controls movements and not individual muscles. We presume that when the digits of Einstein’s left hand were pressing on the fingerboard of his violin, neurons in his right cortical knob were discharging. However, we still can’t tell you which discrete group of neurons was governing the contraction of his flexor digitorum profundus as it was was crooking his left pinky against the violin’s strings. Of course, finger movements are not music. The motor “programs” underlying Einstein’s performance of Brahms’s G-major violin sonata are neuroanatomically “upstream” from his motor cortex. A precise localization of where his or anybody else’s music “lives” is unknown. (You didn’t really think neuroanatomy would be that simple, did you?)

The left frontal lobe also revealed an expanded rectangular area of cortex just below the precentral sulcus that had been displaced “extraordinarily high above the Sylvian fissure.” This effectively increased the amount of motor cortex devoted to the right face and tongue, as pictured in Penfield’s homunculus cartoon.84 This expanded region bordered the diagonal sulcus, which, remarkably, was found in both of Einstein’s hemispheres (and is typically a unilateral finding in normal brains). In front of (rostral in anatomical argot) the diagonal sulcus is the pars triangularis, a patch of cortex that subserves the production of language (by speech, writing, and signing) and which contains a major portion of Broca’s area. For over 95 percent of humankind (99 percent of right handers and two-thirds of left handers), Broca’s area in the left hemisphere is dominant for expressive language or speech.85 Einstein’s left pars triangularis was found to be unusually convoluted compared to its fellow in the right hemisphere, and this finding goes hand in hand with the greater anatomical complexity of Broca’s area. It would not be unreasonable to expect that this anatomical “upgrade” in Einstein’s brain of the speech area and the face/tongue motor cortex would lead to greater facility in expressing language. Paradoxically, family lore surrounding Einstein’s childhood argues that this was clearly not the case. Einstein did not begin speaking until after he was two years old, and when he did it was with a kind of echolalia in which he would softly whisper the words or sentences prior to uttering them aloud.86 If Einstein’s delay in language acquisition was a form of aphasia, most neurologists (including me) would have anticipated the destruction (and not the expansion) of Broca’s area in the left frontal lobe. In a related clinical phenomenon, children who become aphasic will “switch” the dominance for language from the damaged left hemisphere to the right hemisphere and become left-handed in the process. Such a switch did not occur with Einstein, who was right-handed, and his expanded and convoluted pars triangularis does nothing to unravel the mystery of his abnormal speech development.

Figure 5.5. Looking down on the dorsal surface of Einstein’s brain demonstrates the poles of the frontal lobes (top) and the tips of the occipital lobes (bottom). The central sulcus (Central s.) separates the frontal lobes from the parieto-occipital lobes and nicely illustrates the relatively greater volume of the frontal lobes compared to the other lobes in humans (and not just Einstein). The right cortical knob looks like an inverted letter omega abutting the central sulcus. The left cortical knob on the anterior borders of the central sulcus demarcates the smaller motor representation of Einstein’s right hand. (Harvey Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine.)

Any discussion of parietal lobe anatomy (including our new findings) must be tempered by the remarks of Macdonald Critchley, who devoted an entire book to the topic and stated: “The boundaries of the parietal lobe are not altogether satisfactory and that the exact surface-area is often a matter of conjecture.”87 Gerhardt von Bonin, one of the anatomists who received slides from Thomas Harvey, wrote that “the parietal lobe has at least two spheres, the somatosensory and the parietal association areas, whatever that may mean.”88 If your wedding ring fits a little too loosely on your left ring finger, the parietal somatosensory cortex on the right postcentral gyrus is activated. Penfield convincingly demonstrated that kind of straightforward localized neurophysiology. However, the perception or consciousness of the loose ring can’t be reduced exclusively to the simple neurophysiology of action potentials originating in the neurons of the postcentral convolution. Is my feeling, or qualia, of a not-so-tight ring the same as yours? The solution to that “hard problem”89 is unknown and is at the root of the profound mystery of consciousness.

As long as we hug the coast of sensory neurophysiology and do not sail into the deeper waters of consciousness, von Bonin’s sphere of parietal somatosensory cortex remains a simple proposition. This is not so for the parietal association areas that lie further back (caudal) from the postcentral gyrus. In contrast to the postcentral gyrus, which is unimodal, parietal association cortex is heteromodal and receives inputs from ipsilateral—that is, in the same hemisphere—frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes (and from the contralateral hemisphere by way of corpus callosum connections).90 This is an inconceivably busy neural crossroads that (especially the superior parietal lobule) constructs maps of our body and extrapersonal space (which in Einstein’s case may have encompassed space-time). And I almost forgot: the posterior parietal cortex (and the dominant inferior parietal lobule in particular) is critical to the understanding of spoken and written language, performance of mathematical calculations, as well as the interpretation and manipulation of symbols.91

Harvey’s “lost” photographs revealed new and unsuspected anomalies of Einstein’s parietal lobes in the regions previously discussed. The unimodal postcentral gyrus was markedly expanded on the left, parietal heteromodal cortex covered (opercularized) the underlying insular cortex definitely on the left and likely on the right, the inferior parietal lobule was larger on the left, and the superior parietal lobule was markedly larger in the right hemisphere. The presence or absence of parietal opercula hinged on the continuity of the ascending branch of the Sylvian fissure with the postcentral sulcus. If these sulci (which join at right angles to each other) are not continuous, the anatomists declare the presence of opercula. Witelson found that the two fissures were confluent and therefore posited the “absence of the parietal opercula.”92 We strenuously objected and asserted that a submerged part of the supramarginal gyrus interrupted the course of the left Sylvian fissure-postcentral gyrus system. How come?

Easy. Dean had access to the newly rediscovered Harvey photos that were either unavailable or ignored by Witelson. The difference in perspective of the individual photographs cannot be overestimated. By way of comparison, my wife, Lynn, and I love to visit the Grand Canyon again and again, and we know that if we stand back from the trail along the South Rim at Mather Point we won’t see the ribbon of the dark-green Colorado River cutting through the Vishnu Schist over a mile below us. As we get closer to the edge of the South Rim precipice, the river comes into view at the canyon bottom. Similarly, the vantage point of one of Harvey’s photographs (Figure 5.6) “looks down” several millimeters from the cortical surface to the bottom of the left postcentral gyrus. By closely examining this photograph, Dean identified the submerged supramarginal gyrus hidden from view in Witelson’s published photographs93 taken from more traditional right and left lateral views. Dean also unearthed submerged gyri in both diagonal sulci (Figure 5.6). Our access to additional photographic views allowed greater insight into Einstein’s cortical anatomy—and the more we looked, the more we found!

In short, we brought to light the difference between every lobe (frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital) of Einstein’s brain and normal human neuroanatomy as set forth in the atlases of Connolly94 and Ono.95 Even the split-brain views that revealed the medial surfaces of both hemispheres uncovered abnormal convolutions of the cingulate gyri curling around Einstein’s corpus callosum. Despite Dean’s exhaustive efforts to identify each and every gyrus and sulcus on the photographs, some of the fissures found on the cingulate and postcentral gyri remain unnamed in the standard reference brain atlases. These map the cortical surfaces of thirty “White” and thirty “Negro” brains (Connolly) and twenty-five European brains (probably—it’s a Swiss study, but then again, Ono was Japanese) of unknown sex and age (Ono) in meticulous detail. Both studies focused on the sulci rather than the gyri. Ono, working with the Swiss neurosurgeon M. Yasargil, was charged with mapping the “corridors of the sulci and fissures” essential for performing microsurgical procedures.96 Writing in 1950, Connolly addressed the evolving fissural patterns of lemurs to anthropoids to humans and felt that the “size and gross structure of the brain” were not reflective of “intellectual capacities.”97 It is unknown whether Thomas Harvey was acquainted with Connolly’s cautious stance on “the descriptive reports on the brains of deceased scholars.”

Figure 5.6. Submerged gyri. Another of Harvey’s original 1955 photographs shows Einstein’s left hemisphere from a slightly different perspective than the left lateral picture that Witelson used). In this photo the frontal lobe is nearer to (and the occipital lobe farther from) the film plane in Harvey’s camera. Dean Falk realized that this perspective opened up her view of the depths of the diagonal sulcus, d, and the posterior ascending limb of the sylvian sulcus, aS, allowing her to appreciate the previously unrecognized submerged gyri in both diagonal sulci (right not shown). Additionally, the vertically oriented linear structure (like an upright “rice grain” adjacent to label aS) is an anterior part of the supramarginal gyrus. Falk observed that the lower part of the “rice grain” also descended deeper (on a scale of millimeters relative to the cortical surface) and provided anatomical evidence that the posterior ascending limb of the sylvian sulcus and the postcentral inferior sulcus, pti, were separate and not confluent, contrary to the literature. Falk had established that Einstein did indeed have parietal opercula and unusual parietal lobe anatomy. (Harvey Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine.)

In the wake of our Brain publication, we were gratified with one referee’s appraisal that “this is a remarkable document describing in great detail the surface anatomy of Einstein [sic] brain in a way that has not been done before by any team of experienced anatomists and including new materials.”98 Prior to our study, it was well known that Einstein’s brain was no “bigger” and that his parietal lobes were exceptional.99 Our new evidence established that the brain was not spherical in shape but had frontal and occipital bulges (petalias), that every lobe had unusual sulci and gyri, and that the parietal lobes were “opercularized.” David C. Van Essen has hypothesized that axons in strongly interconnected brain regions may produce tension that keeps “wiring length short and overall neural circuitry compact.”100 This model suggests that the anomalous folds of Einstein’s cortex may reflect variant white matter connections and novel axonal architecture. In September 2013 we would see this intriguing hypothesis put to the test.

The “Callosal” Brain

Physicists are fascinated by the brain. Right up there with quantum mechanics and the big bang, the brain holds its own as one of the Great Mysteries, which is irresistible to people who follow the runs of the Large Hadron Collider with the same intensity as football fans who follow World Cup matches. Eminent scientists who have divided their efforts between physics and neuroscience include Sir Roger Penrose, the mathematical physicist who rejects the notion that thinking is “the action of some very complicated computer”101 and proposed that consciousness arises from quantum gravity effects in the microtubules of the neuronal cytoskeleton.102 A few blocks (not allowing for the athletic fields and a few Gothic quadrangles) from where I’m writing this, Sebastian Seung, formerly on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) physics faculty and now a professor at the Neuroscience Institute of Princeton University, is attempting to make the leap from reconstructing tiny volumes of neural circuitry in the mouse retina to the complete connectome of a mammalian brain.

And that brings us to Weiwei Men, who since his teens has revered Einstein. Dr. Men worked as a postdoctoral physicist at the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Magnetic Resonance at East China Normal University. He realized that among the fourteen photographs in our paper were two of the medial surfaces of the bisected brain that showed a cross section of the corpus callosum with great resolution and accuracy (Figure 5.7). Dr. Men enlisted Dean’s assistance for a study comparing the measurements of Einstein’s corpus callosum with those of control groups of fifteen age-matched and fifty-two younger (aged twenty-four to thirty years) living men.103 The term measurements does not begin to describe the methodology of comparing the analog data from Harvey’s photographs to the digital data from Dr. Men’s MRI brain scans of his control group. How do you adjust for the different scales of Harvey’s eight-by-ten prints and the MRI images? The shrinkage and distortion of formalin-preserved neural tissue versus the living brains of the controls? The asymmetry of a corpus callosum cut in half by a pathologist’s “brain knife” versus the virtual bisection of brains created by the data acquisition parameters of three different MR scanners? The nuts and bolts of Men’s methodology alone required five pages in both his Brain paper and his supplementary material!

Figure 5.7. Einstein’s bigger corpus callosum is apparent on the cut medial surface of the left hemisphere, with Harvey’s original labels of the bisected brain after removal of the cerebellum and brain stem. The frontal lobe is on the right, and the occipital lobe is on the left. The medial surface of the left hemisphere displays the sulci of the frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes. At the center the flattened arc of the bisected white matter of the corpus callosum appears lighter than the surrounding cortical gray matter. Weiwei Men found that Einstein’s corpus callosum was larger than those of sixty-seven younger and age-matched controls. (Harvey Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine.)

Why is the corpus callosum important? Well, for starters it’s big. It’s the largest white matter bundle in the human brain and contains over two hundred million axons connecting the right and left hemispheres. Although “size does matter” in biology, the functional importance of the corpus callosum in humans was not confirmed until the 1960s. Twenty years earlier Akelaitis and Van Wagenen had found that complete transection of the callosum in patients treated for intractable epilepsy produced “no behavioral or cognitive effects.”104 As discussed in chapter 3, Michael Gazzaniga’s study of the split-brain patient W. J. rewrote our understanding of the functional neuroanatomy of the corpus callosum.105 In short, Gazzaniga found that “the human brain produced two separate conscious systems” in 1962.106 At the time Gazzaniga was a graduate student in Roger Sperry’s lab at the California Institute of Technology (Cal Tech), and two decades later, in the time-honored academic tradition of “winner (or in this case, lab chief) take all,” Sperry went on to receive the 1981 Nobel Prize for ground-breaking discoveries of the functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres. Gazzaniga went on to further characterize the startling hypothesis of two minds residing in one brain. This is not as unexpected as you might think. For most of humanity, the capacity for language after the first few years of life is hard-wired (less “plastic”) in the left hemisphere. We can only guess at how thinking is “transacted” in the right hemisphere that lacks innate language. Ergo, the two hemispheres are functionally (and anatomically) very different. In split-brain patients, Gazzaniga found that the left hemisphere provided logical explanations for right-handed picture matching but offered implausible explanations for matches performed by the left hand. In this experiment the left hemisphere was blind to pictures viewed by the right hemisphere, which could not transfer visual information across the severed corpus callosum. As a result, the left hemisphere was dubbed “the interpreter”107 and concluded to be “capable of logical feats that the right cannot manage.”108 It requires very specialized experimental techniques to ferret out the altered behavior of postsurgical split-brain patients, but what about patients who are born without a corpus callosum? Some patients with this condition—agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC)—can have normal intelligence with subtle neuropsychological defects that are never detected during their lifetimes. Others are clearly abnormal: Kim Peek, the real-life inspiration for the film Rain Man, had ACC and savant syndrome characterized by a photographic memory and virtuoso mathematical ability. Both acquired (surgical) and congenital defects of the corpus callosum provide varied and fascinating glimpses of abnormal callosal function, but what are the consequences of “supernormal” callosal operations?

With more than a half century’s revelations about the cognitive science of the corpus callosum as a backdrop, what did Dr. Men’s examination discover? At 1,230 grams, Einstein’s brain was no larger than average … there, I’ve said it again. But his corpus callosum was larger than both young and old controls in seven (out of ten) different measurement categories. The underlying assumption was that increased callosal area indicated a greater number of axons crossing through the corpus callosum. (Alternative hypothesis alert! You could have a lesser number of axons crossing through an enlarged corpus callosum if they were hypertrophied, i.e., big and fat like a squid’s giant axons. This is the way scientists and persnickety reviewers are supposed to think.) One reasonable implication of having a brain of average (or less) size and a corpus callosum of above-average size is that Einstein had greater neural interconnectivity, or “internal wiring,” than a normal human. Einstein’s cortex (gray matter) and microscopic cell counts (neurons and glia) had been examined since 1955, but no one prior to Men had performed a scientifically rigorous examination of the largest white matter bundle in the brain.

This was not Dr. Men’s first neuroanatomical “rodeo.” In his 2013 doctoral dissertation, he devised MRI templates to compare the “wider, higher, and rounder” brains of 120 Chinese with the “longer” brains of 120 Caucasians. The Chinese cohort’s corpora callosa had thicker “front ends” (genu and rostrum) and “back ends” (splenium). No statistical difference between the volumes of Chinese and Caucasian brains was found.109 Applying his methodology to Einstein’s brain, Men was quick to point out that the corpus callosum is not a uniform structure but has regional differences with important functional implications. Anteriorly, Einstein’s rostrum and genu were thicker than those of the young and old controls. This callosal region connects the right and left orbital gyri and prefrontal cortices and could conceivably carry greater neural traffic between the expanded prefrontal cortices that we had found. Einstein’s callosal midbody linking primary motor and sensory cortex and other parietal lobe regions was thicker, possibly to accommodate a greater interhemispheric transfer of information from Einstein’s omega-shaped motor cortex knobs and enlarged left motor and sensory (subserving face and tongue) cortices. Bringing up the rear, the splenium is a conduit for neural data between the parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes. The greater bulk of Einstein’s splenium could permit greater integration of output from Einstein’s bigger left inferior and right superior parietal lobules.

As Dr. Men and all academics know full well, the editorial process is invariably a roller- coaster ride. One referee commended the paper for opening “a new aspect of the study of the Brain of an individual of great significance for the scientific community and one might say humanity as a whole.”110 The editor of Brain was more circumspect. The paper would be accepted with minor revisions, but fearing that two papers on Einstein (ours and Men’s) might ever so slightly transform one of the great periodicals of neuroscience into a Journal of Einstein Brain Studies, he sensibly advised the authors to wrap any additional findings about Einstein’s brain “into this second communication” rather than submitting a third manuscript (and trying for an Einstein brain “hat trick”). Editorial vicissitudes aside, Dr. Men has approached his research in neuroimaging with infectious enthusiasm and wants to work with MRI and functional MRI “forever.” He has moved nine hundred miles northwest to Peking University, where as a postdoc he is expanding his dissertation’s database with MRI images of two thousand young Chinese people.111

Men’s measurement technique used four hundred points along the top and bottom edges and the longitudinal middle lines of the corpora callosa of Einstein and sixty-seven controls. Its impact was immediately apparent in the precision of his computer-generated callosal thickness plot and distribution maps. For example, Men measured the average midsagittal cross-sectional area of Einstein’s corpus callosum at 7.72 cm2, significantly larger than the controls’ 6.69 cm2. This contrasts with the caliper measurements recorded by Thomas Harvey in 1955 and published in Witelson’s paper. The average area of Einstein’s corpus callosum was 6.8 cm2, which is nonsignificantly smaller than the 7.0 cm2 of her thirty-five controls.112 Dr. Men’s improved method of measuring provided a very different and more detailed picture of Einstein’s corpus callosum, and the hypothesis of Einstein’s greater interhemispheric connectivity was firmly grounded in his robust data. It is ironic that Witelson had produced a rigorous and superb body of work on corpus callosum anatomy for over a decade before she studied Einstein’s brain.113 For those important studies on callosal anatomy and its implications on hemispheric interconnectivity and specialization, she had employed postmortem brain dissection, tracings from brain photographs, and digitizing morphometry software. In contrast, when studying Einstein’s corpus callosum, she relied on secondhand caliper measurements from forty-four years earlier. We can only surmise that discovering the exceptional anatomy of Einstein’s parietal lobes eclipsed any thought of a meaningful variation of his callosal anatomy. Intended or not, Dr. Witelson’s oversight was to become Weiwei Men’s scientific gain.

Nearly a century before the advent of digitally acquired morphometric data, Dr. E. A. Spitzka (1876–1922) found the association between genius and a larger corpus callosum. Spitzka, the physician who examined the autopsied brain of the assassin of President William McKinley, wrote a monograph-length article on his study of the brains of “six eminent scientists and scholars” in 1907.114 In chapter 3 I have previously remarked on Spitzka’s readiness to leap across the yawning chasm that separates neural structure from function. He used a “new criteria of brain measurement and fissural pattern” to study six eminent members of the American Anthropometric Association who gave consent to the postmortem examination of their own brains. Spitzka found that the brains of men “possessing large capacity for doing and thinking … [when] compared with ordinary men individually and collectively [the ‘doers and thinkers’] have larger callosa.” Spitzka did data mining on the left-sided slope of the bell-shaped curve of human intellect by using illiterate laborers for comparison. Some readers (including me) might take exception to his use of murderers “executed by electricity” for “normal brains.” He concluded that the size of the corpus callosum was “an index in somatic terms” for distinguishing elite brains. At its best, science is an accumulation of data points that can amass, if need be, over centuries. Hypotheses can change, but good and plentiful data should be the constant from which science reframes its theories. Over a century after Spitzka’s speculative pronouncement about the corpus callosum of eminent scientists and scholars, Dr. Men added a crucial measurement. And we’re still learning. We can only guess at what neuroscientists a century hence will consider received wisdom about the corpus callosum and the connectome.