Zoning In

Submitted—as The Twilight Zone’s creator, host, executive producer, and primary writer Rod Serling might have said—for your consideration: two televisual references (among many) to the original The Twilight Zone, one of the most memorable network-era television dramatic series of all time.1

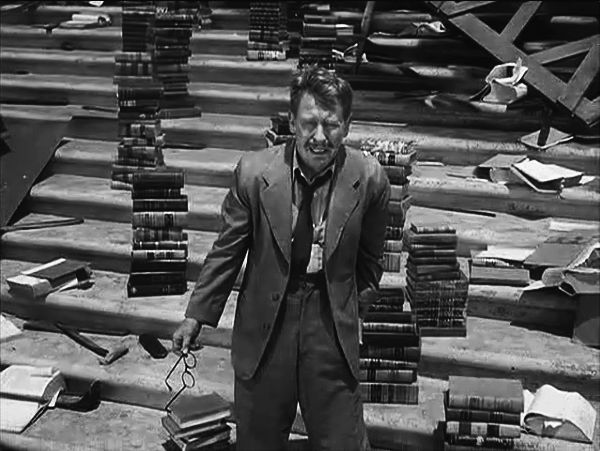

The first reference: In an episode of the contemporary animated series Family Guy (Fox, 1998–) entitled “Wasted Talent,” first aired July 5, 2000, Peter Griffin discovers he has the ability to play the piano only when drunk. When his wife, Lois, wonders about the extent to which alcohol is affecting his mental health, a zoom shot into Peter’s cranium shows that all the brain cells have died because of his excessive drinking—except for one lone cell, who wears glasses (it is a brain cell, after all, even if it does belong to Peter Griffin). The brain cell’s glasses fall off and shatter as it cries “It’s not fair!” This, of course, is a reference to one of the best-remembered Twilight Zone episodes, “Time Enough at Last” (1.8: November 20, 1959), starring Burgess Meredith as misanthropic bank clerk Henry Bemis, a schnook who just wants to be left alone to read but who meets the same ironic fate as Peter’s brain cell after an atomic war leaves him the only person alive.

The second reference, seventeen years later: On the evening broadcast of The Late Show on June 29, 2017, host Stephen Colbert—in what had become an almost-nightly ritual for him and other late-night-comedy-show hosts since the new president took office that January—once again skewered President Donald Trump. On this occasion, following Trump’s attacks on Joe Scarborough and Mika Brzezinski of MSNBC’s Morning Joe, Colbert showed a clip of Sarah Huckabee Sanders, then deputy press secretary, at a White House briefing saying that to be surprised to see the president on the attack after being criticized by these news anchors is like being “in the twilight zone.” Colbert followed up by looking into the camera and declaring, “Oh, I love The Twilight Zone. Which one is he again? Is he the little boy with no morals who has the power to kill? ’Cause it’s definitely not the guy who wants to be alone reading books.” His joke about Trump’s anti-intellectualism alludes to the same Twilight Zone episode as The Family Guy reference as well as another, “It’s a Good Life” (3.8: November 3, 1961), about a family terrorized by a small boy (Billy Mumy) who can make anything happen just by thinking it and whose fates therefore hang always on his whims.

Both of these allusions assume not only that the audience will get the reference to a television show that was first broadcast more than half a century ago but also that they will know specific episodes. Such intense viewer appreciation of individual episodes, rather than merely of the show generally, is a distinctive feature of Twilight Zone fandom. This marked fan enthusiasm for the show also provides the joke that informs the opening of the film spinoff Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). (Significantly, of the many television shows that have inspired movie adaptations, The Twilight Zone is the only anthology show—that is, one without recurring characters—to do so. What viewers tend to remember from the show are issues and ideas—and, of course, the twist endings—more than characters.) Twilight Zone: The Movie featured new versions of three memorable episodes of the show—“Kick the Can” (3.21: February 9, 1962), “It’s a Good Life,” and “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” (5.3: October 11, 1963)—as well as a new story, “Time Out,” all preceded by a short prologue. Each of the episodes was done by a different director, each of whom already had been associated with fantastic cinema: John Landis, Steven Spielberg, Joe Dante, George Miller. In the prologue, also directed by Landis, two nameless guys (Dan Ackroyd, Albert Brooks) are driving through the vast American southwest in the dark of night. To pass the time, they begin to play trivia, at first challenging each other to identify television-show theme songs. Inevitably, they come around to French composer Marius Constant’s distinctive theme for The Twilight Zone—probably the most instantly recognizable television theme music of all time—and, discovering a shared love for the show, they then take turns recalling some of their favorite episodes (“Remember the one where . . . ?”), repeating a conversation already had innumerable times by baby boomers everywhere (including, I confess, the author of this book).

Burgess Meredith as the unfortunate Henry Bemis in “Time Enough at Last.”

Of course, their trivia game can only be topped by a twist worthy of The Twilight Zone itself. Ackroyd asks Brooks if he wants to see something “really scary,” to which Brooks cautiously agrees. Then Ackroyd turns into a quickly glimpsed hideous monster who, as the film cuts to a long shot outside the car, is heard chomping on the unfortunate Brooks before the camera tilts up into the nighttime sky to evoke the familiar opening and closing shots of the television show’s stories—narrated now by none other than Burgess Meredith (who, while best remembered for “Time Enough at Last,” starred in three other Twilight Zone episodes as well).

The Twilight Zone ran on CBS for five seasons, from October 1959 to June 1964. During its run, the show was nominated for multiple awards, winning three Emmys (two for Serling as writer and one for George T. Clemens for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography for Television) as well as a Golden Globe Award for Serling for Best Producer/Director. For each of its first three seasons it won a Hugo Award from the World Science Fiction Society for Best Dramatic Achievement. On the show’s coattails the network launched a similar series, ’Way Out, in 1961, hosted by offbeat writer Roald Dahl, to pair with The Twilight Zone on Friday evenings, while ABC “countered” with The Outer Limits (ABC, 1963–65).

The show has continuously been in reruns on American television, and all of the original 156 episodes (with a handful of exceptions) are available on streaming services such as Hulu and iTunes. The Syfy channel has programmed a Twilight Zone marathon on New Year’s Eve for two decades. CBS’s website offers ten episodes for free and the others by subscription. In the age of the internet, there are numerous websites devoted exclusively or in part to the show or to Rod Serling.

In first run, The Twilight Zone’s ratings were never very strong. “We were always on the verge of getting canceled,” recalled producer Buck Houghton (Grams, 67). It was pitted first against 77 Sunset Strip (1958–64) on ABC and then The Detectives (ABC, 1959–61; NBC, 1961–62) with Robert Taylor and NBC’s reliable Gillette Cavalcade of Sports (1946–60). But by the midpoint of the first season of thirty-six episodes, the show’s ratings improved somewhat, and the network realized it had a “prestige program” (King, 232). The critics were generally enthusiastic: Cecil Smith of the Los Angeles Times called it “the finest weekly series of the season,” while John Crosby of the New York Herald Tribune said it was “certainly the best and most original anthology series of the year” (qtd. in Presnell and McGee, 16). Terry Turner of the Chicago Daily News wrote that The Twilight Zone “is about the only show now on the air that I actually look forward to seeing. It’s the one series that I will let interfere with other plans” (Zicree, 96–97). While its audience share may not have been exceptionally large, the viewership it did generate was exceptionally loyal—“all over America on Friday nights people held Twilight Zone parties” (Zicree, 211)—and it is no surprise that TV Guide ranked the show eighth in its list of the “25 Top Cult shows Ever!” (May 30, 2004). Yet despite its critical success, each season the show seemed to hang on, finding sponsors at the eleventh hour until, finally, after five years, James Aubrey, vice-president of CBS in charge of programming and then president during The Twilight Zone’s run, finally canceled it, citing cost overruns, relatively tepid ratings, and the skittishness of sponsors (Murray).

Since then, the continuing popularity of the show is clear from the numerous transmedia iterations and references to it that, as already suggested, have appeared across the many forms of popular culture, as a quick survey reveals. In print, while the show was still in first run Serling novelized several of his original scripts for the anthologies Stories from the Twilight Zone (1960), More Stories from the Twilight Zone (1961), and New Stories from the Twilight Zone (1962), all of which have enjoyed multiple printings and together have sold millions of copies, as has The Twilight Zone: Complete Stories, published in 1980. In 1995, DAW Books, a science-fiction and fantasy imprint, published three anthologies edited by Serling’s widow, Carol Serling—Journeys to the Twilight Zone, Return to the Twilight Zone, and Adventures in the Twilight Zone—each of which contained a story by Rod Serling. Gauntlet Press in Colorado completed a ten-volume set of original scripts from The Twilight Zone by Serling in 2013, as well as books of scripts by the show’s two most frequent writers after Serling, Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson. In September 2009, Tor Books published Twilight Zone: 19 Original Stories on the 50th Anniversary, containing new tales by contemporary authors such as R. L. Stine, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the show. There also have been several comic book tie-ins, including one from Gold Key (Western Publishing) that ran ninety-one issues from 1963 to 1979, and The Twilight Zone Magazine (also known as Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone Magazine), which was published monthly from 1981 to 1989.

Musical artists representing a wide diversity of styles have created work based on The Twilight Zone, among them John Cale, Iron Maiden, Manhattan Transfer, the Ventures, and the Residents. Contemporaneously with the show, in 1964 a Los Angeles session group named the Marketts had a number 3 charted hit, “Out of Limits,” which clearly echoed the show’s theme music. Episodes of the show have been adapted for radio broadcast on both subscription and commercial radio, with Stacy Keach replacing Serling as narrator. The script for the episode “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” (1.22: March 4, 1960), one of the most famous, has been published as a play for student production, and live theater productions of original episodes have been staged in several cities, including Los Angeles, London, and Seattle, where Theater Schmeater has mounted a continuing show, “The Twilight Zone—Live,” with permission of the Serling estate, since 1996. Also based on the series, The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror is an attraction at several Disney theme parks (the one at Disney California Adventure Park in Anaheim was closed in 2017). The show was adapted as a board game by Ideal in 1964, during its initial run, and as a video game in 1988 and a pinball game by Bally in 1992.

The show has been parodied many times. One of the earliest, on The Jack Benny Program (CBS, 1950–64, NBC, 1964–65) broadcast on January 15, 1963, begins with Benny hiring Serling to help improve the level of writing on his show. Their meeting falls apart when Serling confesses that he doesn’t understand Benny’s comedy and Benny admits that The Twilight Zone never really made any sense to him. On his way home Benny, lost in a thick fog, notices a signpost up ahead indicating that he is in the Twilight Zone (“subconscious” twenty-seven miles ahead, “reality” twenty-five miles behind). He manages to find his house, but Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, who plays Benny’s servant on his show, doesn’t recognize him when he gets there. Serling, now owner of the house and mayor of the town, appears in a dressing gown and, exploiting a running joke about Benny’s age, observes that “anyone who claims to be thirty-nine years old for as long as he has is a permanent resident of the Twilight Zone.”

Since its initial run, many of the show’s “plots, characters, and conceits entered the American consciousness . . . supplying a rich bank of iconic images” (Norris, 3–4). Thus, it is no surprise that, according to Serling biographer Joel Engel, the volume and variety of merchandising made The Twilight Zone “one of the most profitable shows in the history of television” (235). The mountain of merchandising it has generated includes a face mask of the gremlin on the airplane wing in the “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” episode, a decal of the open door in the later series opening, and a replica of the tabletop fortune-telling machine from the episode “The Nick of Time” (2.7: November 18, 1960). There are the inevitable coffee mugs and action figures of many of the characters, such as the robot Alicia from “The Lonely” (1.7: November 15, 1959) (with her humanoid face ripped off, of course, as in the climax of the episode), a nurse and doctor from “Eye of the Beholder” (2.6: November 11, 1960), various aliens such as the three-eyed soda jerk from “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?” (2.28: May 26, 1961), and (ironically) Jerry and the evil Willie from “The Dummy” (3.33: May 4, 1962). One can purchase black T-shirts with the show’s name in its distinctive angular font or with other variations from the CBS store. The wittiest T-shirt available, I think, is one referencing the episode “To Serve Man” (3.24: March 2, 1962), in which it is discovered that human tourists flocking to the home world of the alien Kanamits actually are being cooked and eaten; the shirt features the face of a Kanamit dressed as Colonel Sanders with the logo “KFH” (presumably, Kanamit Fried Human) and slogan “Looking Forward to Serving You.”

The Twilight Zone has been revived thrice: first on CBS for two seasons from 1985–87, with actor Charles Aidman as host (Aidman had starred in two episodes of the original series, “And When the Sky Was Opened” [1.11: December 11, 1959] and “Little Girl Lost” [3.26: March 16, 1962]) and running for sixty-five episodes; in 2002–2003 for one season on UPN, with Forest Whitaker as host and lasting for forty-three episodes; and most recently, on CBS All Access beginning in April, 2019, with Jordan Peele as host. The UPN iteration included remakes of some original classic episodes, such as “Eye of the Beholder” and “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” as well as “It’s Still a Good Life,” a sequel to “It’s a Good Life” with Billy Mumy returning to the role of the monstrous child Anthony now as an adult. In the newest version, Jordan Peele (who also acts as executive producer) may at first seem an unlikely choice to serve as host given his association with comedy (earlier in his career he appeared for five seasons on Mad TV [Fox, 1995–2000; CW, 2016–] and with Keegan-Michael Key for three years on Key & Peele [Comedy Central, 2012–15]); but clearly he hopes to build on the success of his award-winning horror/comedy Get Out (2017). Peele has acknowledged that his subsequent feature film, Us (2019), released just before the launch of his Twilight Zone reboot, was inspired in part by the original Twilight Zone episode “Mirror Image” (1.21: February 26, 1960), further reinforcing his association with horror rather than comedy and his fit as host of the new show. While some of the episodes of Peele’s version may be more overtly political, none of these hosts come close to attaining anything like the remarkable resonance, as discussed in chapter 2, of Rod Serling.

Later shows that are commonly seen as having been influenced by The Twilight Zone include The X-Files (Fox, 1993–2002, 2016–) and Black Mirror (Channel 4, 2011–14; Netflix, 2016–). One of the latter show’s most highly regarded episodes, “San Junipero” (third series, 2016), was inspired by the premises of the Twilight Zone episodes “Walking Distance” (1.5: October 30, 1959) and “A Stop at Willoughby” (1.30: May 6, 1960). The show also has influenced many feature films, providing them with similarly speculative premises. A partial list includes Liar, Liar (1997), about a man who is cursed to tell the truth (2.14: “The Whole Truth” [February 20, 1961]); Child’s Play (1988), about a killer doll (5.6: “Living Doll” [November 1, 1963]); Frequency (2001), involving a radio that broadcasts transmissions from the past (2.20: “Static” [March 10, 1961]); Real Steel (2011), about boxing robots (5.2: “Steel” [October 4, 1963]); Time Lapse (2014), about a camera that takes pictures of the future (2.10: “A Most Unusual Camera” [December 16, 1960]); The Truman Show (1998), about a man who discovers that his life is an arranged reality-television show (1.23: “A World of Difference” [March 11, 1960]); and Her (2013), about a lonely man who falls in love with his computer’s operating system (“The Lonely”). One might even consider Poltergeist (1982) to have been inspired in part by the episode “Little Girl Lost” and the family-friendly Toy Story (1995) by the Pirandellian episode “Five Characters in Search of an Exit” (3.14: December 22, 1961), which tells the story of a group of dolls in a Christmas donation bin wondering who and where they are. Several of M. Night Shyamalan’s films, including The Sixth Sense (1999), Signs (2002), The Village (2004), and The Visit (2015), as well as similar fantastic films like the Duffer brothers’ Hidden (2015), involve twist endings that are clearly indebted to the show. Devil (2010), based on a story by Shyamalan, places Satan disguised as a human among a group of people trapped in an elevator, much like the similarly disguised Martian in the snowbound diner in “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?”

Even today, most North Americans, including those born after the show’s initial run, know the series’ distinctive theme music, the first few notes of which have come to represent an iconographic shorthand for something odd or weird occurring. The theme music for the first season was provided by Bernard Herrmann, the distinguished Hollywood composer who had a long association with Alfred Hitchcock, but it was changed toward the end of the season to Marius Constant’s more familiar theme. Constant had been commissioned by Lud Gluskin, director of music for CBS, to provide some short pieces for the company’s stock library. He created the Twilight Zone theme by editing two of them together (Grams, 70–72), one featuring those opening four repeated notes on electric guitar (played by jazz guitarist Howard Roberts). The bongos toward the end add a hint of bohemian weirdness appropriate to the show’s fantastic ambiance.

This lengthy catalog of the show’s cultural afterlife makes clear the astonishing popularity The Twilight Zone has had and that shows no sign of abating more than half a century after it was on the air. This cultural impact alone guarantees its “enduring status” (Murray) as a television milestone. But the show is also important as a prism through which to see the turbulence roiling within contemporary American culture. During its run, the show spanned the seismic transition from the 1950s to the 1960s—in the words of Stephen King, “From the torpor of the Eisenhower administration to LBJ’s escalation of American involvement in Vietnam, the first of the long hot summers in American cities, and the advent of the Beatles” (King, 229). In those mere five years, the Cold War heated up to boiling point when American and Soviet tanks faced each other in August 1961 as construction began on the Berlin Wall and then during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October the following year. Nuclear tests by both countries proliferated in the decade, and, beginning with a hydrogen-bomb detonation at the Nevada proving grounds in July 1962, the US began testing within its own borders. Communist China detonated its first atomic bomb in 1964, joining the ranks of the superpowers. People were busy buying and building fallout shelters, and “duck and cover” drills continued to be practiced in the nation’s public schools when Twilight Zone episodes invoking the horrors of atomic warfare such as “Time Enough at Last,” “Third from the Sun” (1.14: January 8, 1960), and “The Shelter” (3.3: September 29, 1961) were being broadcast across the nation. The show’s stories, and the characters in them experiencing trauma of one form or another week after week, artfully revealed the stresses at work within American society as well as what Alvin Toffler called “future shock,” the accelerating rate of technological and social change and its psychological effects upon people.

At home, American society fragmented as the various challenges to state power were met with increasing and sometimes violent resistance. While some progress was made in civil rights, in June 1963 Alabama governor George Wallace personally blocked the entrance to the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa when the first two black students, escorted by federal troops, arrived to register. A year later three white civil-rights workers were arrested and then murdered in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Soon black militancy would arise with the Black Panthers, although by the end of the decade most of that group’s leaders were either in jail or dead. In 1964, the year The Twilight Zone concluded its five-season run, Bob Dylan diagnosed the state of American culture when he sang “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” noting that “there’s a battle outside and it’s ragin’.”

The show also bridged the significant cultural transition of the fantastic genres—science fiction, horror, and fantasy—from marginal to mainstream, from being scorned as subliterature to embraced as serious art. When The Twilight Zone began, these genres, apart from a few canonical exceptions (Edgar Allan Poe, H. G. Wells, Mary Shelley, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell), were mostly dismissed by cultural critics and tastemakers. By the time the show left the airwaves, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (1954–55), Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), and Kurt Vonnegut’s early works Player Piano (1952), The Sirens of Titan (1959), and Cat’s Cradle (1963) were becoming countercultural cult novels. By decade’s end these and other science-fiction books were beginning to appear in undergraduate English course syllabi across the country.

In film, shortly before The Twilight Zone premiered, science fiction typically translated the anxieties of the atomic era into B-movie creature features. Men mutated into monsters in such movies as The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961), while creatures of every kind took wing and tunneled, crawled, and climbed their way through similar plots featuring scenes of mass destruction, fleeing citizens, and the deployment of military personnel and hardware. This monstrous menagerie included giant ants (Them! [1954]), arachnids (Tarantula [1955]), grasshoppers (Beginning of the End [1957]), octopi (It Came from beneath the Sea [1955]), and crustacea (Attack of the Crab Monsters [1957]). Usually, these creatures were explained as mutations accidentally generated by atomic testing or ancient slumbering beasts awakened by them—more hyberbolic in their metaphors than The Twilight Zone but borne of shared anxieties and fears.

Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), released six months after The Twilight Zone debuted, utterly transformed the genre of the horror film by situating its monster, a serial killer with the appearance and charm of the boy next door, emphatically within the normal and the commonplace rather than an exoticized elsewhere like the Transylvania of Dracula (1931), the uncharted Island of Lost Souls (1932), or the West Indian jungle of I Walked with a Zombie (1943). In contrast to such movies, Psycho’s settings include a cheap hotel room, mundane real-estate office, used-car lot, and a nondescript motel (including a bathroom with toilet!)—the kind of banal places frequently seen in The Twilight Zone, such as a typical bus depot (“Mirror Image”), roadside diner (“Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?”), and, too, cheap hotel room (“A Most Unusual Camera”) and used-car lot (“The Whole Truth”). The Twilight Zone certainly had its futuristic settings and alien worlds, but these were less common than the commonplace—even when the world is otherworldly, as in such episodes as “Third from the Sun,” “People Are Alike All Over” (1.25: March 25, 1960), and “Elegy” (1.20: February 19, 1960). Indeed, for philosopher Mary Sirridge, the show offers nothing less than a warning about what she calls “the treachery of the commonplace” (Sirridge, 58–76). Paradoxically, The Twilight Zone explored the fringes of the fantastic but remained fixed in the familiar, and, like Hitchcock’s film, it revealed the monstrous within the normal and explored how thin the veneer of civilization in fact is.

Other movies such as Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach (1959), Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) showed established auteurs turning to science fiction and horror, a trend that culminated toward the end of the decade with 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), regarded by many as a masterwork of philosophical cinema and the greatest science-fiction film ever made. Bridging this rise to respectability for horror, science fiction, and fantasy, The Twilight Zone was at the same time responsible for much of the dramatic and pronounced cultural shift in attitude.

Unsurprisingly, there has been a great deal already written about The Twilight Zone—indeed, there is perhaps as much scholarly and fan writing about it as for any other show in television history. Writers have looked at the show from a panoply of perspectives, examining its production history, its style, its politics, the trivia. There are at least three books (Zicree, Presnell and McGee, Grams) that offer commentaries on every episode. The show has been discussed in the historical context of its changing representation of the frontier (Norris), its use of cultural myth (Hill), its response to technological change (Laudadio), even as a precursor of postmodernism (Booker). In this book, though, my focus is primarily on the interrelated questions of authorship, genre, style, and ideology in the context of The Twilight Zone. The on- and off-screen influence of executive producer and writer Rod Serling, the show’s unique and complex approach to genre, and the anxieties of the age all came together to make it the memorable show it was.

A short volume such as this one might well have focused primarily on, say, important issues of representation involving race or gender—issues that have been of considerable interest to scholars, to be sure. However, I have chosen not to make them my primary focus here, as one doesn’t have to look too deeply to see that The Twilight Zone is rooted in a white male perspective. Most obviously, the makers of the show were almost entirely white men, as are the overwhelming majority of the show’s protagonists. Only one episode was directed by a woman (“The Masks” [5.25: March 20, 1964], by Ida Lupino), and only one was written by a woman (“Caesar and Me” [5.28: April 10, 1964], by A. T. Strassfield). Although a few episodes do offer female protagonists—Helen Foley (Janice Rule), for example, in “Nightmare as a Child” (1.29: April 29, 1960) or Marsha White (Anne Francis) in “The After Hours” (1.34: June 10, 1960)—more often they were conceived and performed as stereotypes, frequently as harridans constraining men. Gart Williams’s entirely unsympathetic wife, Jane (Patricia Donahue), in “A Stop at Willoughby,” who seems to care only for material comfort and nothing for her husband, is only the most strident of the lot.

In “The Chaser” (1.31: May 13, 1960), Roger Shackleforth (George Grizzard) gives a love potion to Leila (Patricia Barry), the shallow woman he loves but who cares nothing for him; predictably, she becomes a cloying, doting wife who smothers him with her devotion. We learn nothing about how Leila might feel about her bewitchment: the episode, like most, is resolutely positioned within the masculine perspective—Roger’s story and not Leila’s. In “A Penny for Your Thoughts” (2.16: February 3, 1961), when bank clerk Hector B. Poole (Dick York), who has gained the ability to read the mind of whoever is in physical proximity, walks past the people in the bank, the soundtrack features an audio montage of their thoughts, but when he gets to the blonde fondling a wad of cash there is a resounding silence on the soundtrack—a tired “dumb blonde” joke that represents the show’s attitude toward women at its worst. Serling was possibly aware of the show’s disproportional gender representation because among the changes to the series he promised in the second season was that there would be more female protagonists (Grams, 90), although the show’s masculine bias never really did change.

Certainly, one might read the overwhelming majority of the show’s episodes as being about what scholars would identify as revealing masculinity in crisis. In addition to several episodes that reveal men beleaguered if not emasculated by their wives, others such as “The Bewitchin’ Pool” (June 19, 1964) reveal married couples locked in mutual hatred and recrimination. The most recurrent image in the show is that of a close-up of a man’s face, sweaty and emotionally overwrought, as he experiences a psychic breakdown of some sort in the dramatic climax. But such an analysis hardly requires reading against the grain to elucidate it.

Visible minorities appeared infrequently on the show, as was the case for all of network television at the time, and on the few occasions when they did, like the simple Mexican peasants of “Dust” (2.12: January 6, 1961) and “The Gift” (3.32: April 27, 1962), they were little more than stereotypes. While Serling did call out network television for omitting black actors from the small screen (Zicree, 112) and boldly cast black actors in the episode “The Big Tall Wish” (1.27: April 8, 1960), it is also the case that only white people are shown living on Maple Street and in Willoughby. One of the reasons Serling shifted his efforts from writing prestige television dramas for shows such as Playhouse 90 (CBS, 1958–60) and Kraft Television Theatre (NBC, 1947–58) to a lowbrow fantasy and science-fiction series was to avoid the kind of overt and heavy-handed censorship he had experienced when attempting to address matters of race on television.

According to Lester H. Hunt, the turning point in Serling’s approach as a writer from a realist treatment of social issues based on actual events to a more fantastic mode in which the critiques were more generalized was his experience involving his script “Noon on Doomsday” for the United States Steel Hour (ABC, 1953–55; CBS, 1955–63), broadcast on April 25, 1956 (12–22). The plot was originally based on the notorious murder of Emmett Till, a black teenager from Chicago who was killed by two white men for whistling at a white woman in Mississippi where he was visiting family. The two men charged with the murder were acquitted, as was the killer in Serling’s script. US Steel, nervous about the racial connection, relocated the town to New England, changed the victim from Jewish to a vaguely identified foreigner, and eliminated any references to lynching, so that, according to Marc Scott Zicree, “When it was finally aired in April of 1956, ‘Noon on Doomsday’ was so watered down as to be meaningless” (14).

Two years later Serling wrote another script (“especially written,” according to the closing credits) on a similar topic, “A Town Has Turned to Dust,” for Playhouse 90. Although Serling later said that the sponsors and studio execs “chopped it up like a roomful of butchers at work on a steer” (Zicree, 15) and that “a script had turned to dust,” Hunt rightly finds the drama, which was directed by John Frankenheimer, “as powerful and focused as that of ‘Noon’ is weak and vague” (19) because Serling recast the story as a Western. Many of the dramatic techniques that Serling would bring to The Twilight Zone are already present in “A Town Has Turned to Dust,” including the use of a newspaper reporter (James Gregory) who provides commentary periodically and at the end and who explicitly drives home the point that the story provides “a lesson that must be learned by all men.”

The firm, familiar frameworks of generic tradition allowed Serling greater potential to offer social criticism in his work, although, as we shall see, the politics of The Twilight Zone were ultimately contradictory, at once both critical and conservative, this very tension helping to make The Twilight Zone so important and memorable. In what follows, I focus on the place of The Twilight Zone within the various modes of the fantastic, showing how it combined them with other generic traditions to offer social criticism cast as moral fables. As I explain, the show offered a complex mix of generic codes and conventions that provided a shared visual shorthand to viewers that helped make its messages more acceptable to a mainstream prime-time audience. Television scholar Jason Mittell has argued for an understanding of genres in the medium not as text based but “as a process of categorization” that “operates across the cultural realms of media industries, audiences, policy, critics, and historical contexts” (2004, xii). The Twilight Zone serves as a case in point, as it was the fantasy nature of the show, regarded primarily as lowbrow material for juvenile audiences, that allowed Serling to offer his brand of social criticism. “A Martian,” he once declared, “can say things that a Republican or Democrat can’t” (qtd. in Javna, 16).

I then examine the singular case of authorship of The Twilight Zone. As executive producer, chief writer, and on-screen host, Serling was indisputably the main creative force of the show, but how did this authorial control function when numerous established directors, writers, actors, and others were also involved in the show’s production? In examining his vision in The Twilight Zone and in his other work, I show how Serling provided the artistic vision of the series, in effect as one of television’s first showrunners—possibly the first, well before that term even existed. Tracing motifs and themes in the show, I consider how it functioned as an ideal instance of collective authorship built around Serling’s concern with questions of individual morality and democratic principles.

In the final chapter I examine the politics of the show, how it responded to both national and world events and how these related to Serling’s moral vision as it was expressed in individual episodes and across the series’ run. Of course, the ideological values expressed by The Twilight Zone, whether deliberately or not, are inextricable from a consideration of Serling’s authorial voice; I separate them here only for the sake of discussion. Serling was a moralist writing for a mass medium in a rapidly changing society during the height of the Cold War, and the conflicting and conflicted messages of the show’s various episodes inevitably express not only the political tensions of the time but also the commercial nature of television as a form of cultural production. The frequent narrative tensions in the series between art and commerce, individualism and conformity, and nostalgia and modernism express Serling’s conflicted view of television as a medium, and they also may be understood as paradigmatic of that moment in television history when the so-called Golden Age of live television drama was pivoting toward more formula-driven filmed series.

My aim throughout has been to offer the most productive and comprehensive account of The Twilight Zone possible within the scope of a short volume. My approach and organization allow me to discuss the most important forces that shaped the show and the most salient concepts for understanding them. I also have sought to balance detailed analysis of a few selected episodes with broader discussions of multiple episodes in order to provide the necessary depth and breadth that any serious consideration of The Twilight Zone, a show that had no recurrent characters or plot premises, requires.

In a famous speech before the National Association of Broadcasters on May 9, 1961—about midway through The Twilight Zone’s original run—Newton Minow, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, attacked the television industry as “a vast wasteland.” Referring to television’s failure to grapple with real issues and problems, Minow’s comments proved prophetic indeed as the decade unfolded. During the early 1960s popular network sitcoms like The Andy Griffith Show (CBS, 1960–68), Car 54, Where Are You? (NBC, 1961–63), The Beverly Hillbillies (CBS, 1962–71), My Favorite Martian (CBS, 1963–66), The Munsters (CBS, 1964–66), and Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. (CBS, 1964–69) presented escapist visions of an impossible America untroubled by the actual conflicts within contemporary society. Watching a show like Green Acres (CBS, 1965–71), with its bucolic depiction of a harmonious but clearly fantastic rural America, one would never know that political tensions including the war in Vietnam and civil-rights struggles were then rending the social fabric of the nation. The concurrent Hogan’s Heroes (CBS, 1965–71) seemed to erase history entirely with its portrayal of funny and incompetent German soldiers running a World War II POW camp containing irrepressible American GIs. (Serling said that the only people who could appreciate it were those “who refuse to let history get in the way of their laughter” [qtd. in Murray]).

The most popular dramatic genre on television early on in the decade, the Western, also occasionally addressed social issues such as violence and racism but typically displaced them through the genre’s iconography to a past already seemingly remote in the age of television and left them there. No twist ending or host drove home the story’s relevance to the television audience in these shows. Tending to side with the moral righteousness of an unproblematic hero, most (but not all!) TV Westerns offered viewers an easy and comforting distinction between a more primitive (but necessary) stage of social evolution and our more happily enlightened present, where we know better. The early Twilight Zone episode “Execution” (1.26: April 1, 1960) addressed this point directly. In the story, Joe Caswell (Albert Salmi), an outlaw from the Wild West about to be hanged, is transported by time machine to the contemporary laboratory of Professor Manion (Russell Johnson). The brutish Caswell kills the scientist but is then overwhelmed by the bustle and noise of the modern city and so returns to the lab, where he in turn is killed by a burglar. The burglar then by chance transports himself back in time and ends up in the noose intended for Caswell. In addition to the show’s frequently sardonic take on fate and justice, the episode suggests that modern man is no less corrupt and violent than he was in the past.

The Untouchables (ABC, 1959–63) and Bonanza (NBC, 1959–73), two enormously popular shows that premiered in the same season as The Twilight Zone, were rooted in America’s mythic past. By contrast, while The Twilight Zone did feature some episodes set in the past—as well as in imagined futures—the show was emphatically rooted in the America of its time, responding to contemporary events as well as ruminating on the darker, more uncomfortable aspects of human nature and such Big Questions as faith, death, and mortality. If the later Star Trek (1966–69) envisioned an enlightened and lofty future in which humanity’s current social problems have been solved, The Twilight Zone commonly cast its characters, and sometimes its viewers as well, into the “pit of man’s fears.” It was, for Newton Minow, one of the exceptions to the vast wasteland.

1 Serling said “submitted for your consideration” when introducing two episodes, “The Trouble with Templeton” (2.9: December 9, 1960) and “To Serve Man,” although the phrase has become associated with him.