Chapter 2

Active ingredients of the therapeutic relationship that promote client change

A research perspective

Gillian Hardy, Jane Cahill and Michael Barkham

Introduction

A good relationship between client and therapist is, at the very least, considered to be the base from which all therapeutic work takes place. This circumscribed view of the therapeutic relationship is often taken by cognitive and behavioural therapists and is described as “professional skills” in the most widely used instrument for assessing therapist competence in cognitive and behavioural therapy (CBT) (Cognitive Therapy Scale; Young & Beck, 1988). For other psychotherapy schools, the therapeutic relationship is seen as one of the main therapeutic tools for achieving client change (Luborsky, 1994; Klerman, Weissman, Rounsville, & Chevron, 1984). Whatever therapeutic processes are involved in the client–therapist relationship, research has consistently shown a significant association between this relationship and outcome. For example, Norcross (2002) summarised the literature on predictors of outcome in psychotherapy and stated that 15% of outcome is due to expectancy effects, 15% to techniques, 30% to “common factors” which primarily involve the therapeutic relationship, and 40% to extra-therapeutic change.

Against this background, in this chapter we set out three overarching objectives. First, we briefly explore the differing views drawn from diverse theoretical models of what is understood by the term “therapeutic relationship”. Second, we consider why the therapeutic relationship is important. A key component of this relates to the reported relationship with treatment outcome. The role of “common factors” in achieving good treatment outcome will be also outlined. And third, in the substantive part of the chapter we consider the extent of our understanding of the therapeutic relationship and the active ingredients that promote client change. In so doing, we draw on a systematic review we conducted. We provide a map of the development of the relationship between the client and therapist and highlight elements that contribute to the relationship at different stages in the therapy process. Throughout the chapter we refer to the general literature on the therapeutic relationship, not only findings in relation to CBT.

What is the therapeutic relationship?

Freud was the first to consider the importance of the relationship between the therapist and patient in the therapeutic process, and labelled this “positive transference” (Freud, 1940). Greenson (1965) developed the idea that the relationship is central to enabling client change and made the distinction between the working alliance (task focused) and the therapeutic alliance (personal bond). Luborsky (1976) and Bordin (1979, 1994) broadened the concept so that it would be relevant to other types of therapy. The former described two phases of the relationship: the initial relationship being characterised by the client’s belief in the ability of the therapist to help him or her and the therapist’s requirement to provide a secure environment for the client; this later developing into a mutual relationship of working on the tasks of therapy.

Most current conceptualisations of the therapeutic alliance are based on Bordin’s (1979) definition of: “three features: an agreement on goals, an assignment of task or series of tasks, and the development of bonds” (p. 253). Bordin’s definition moved our understanding of the relationship from primarily a psychodynamic to a pan-theoretical concept. This arose as empirical studies to find the ingredients of successful therapy identified factors that are common to most psychotherapies as being responsible for a large part of therapeutic gain. These will be discussed in the next section. In CBT a positive relationship is seen as necessary, though not sufficient, for change to occur. For some therapists interpersonal processes are central to promoting change, and these include using the client–therapist relationship (Safran & Segal, 1990; Whisman, 1993).

However, what this definition of the relationship lacks is a consideration of what the client and therapist bring through their experiences of their past relationships (see Leahy, Chapter 11, this volume). These influence the nature of the relationship that the client and therapist form (Holmes, 1996; Mace & Margison, 1997). There is some evidence that assessing clients’ and therapists’ relationship styles, and acknowledging and working with these styles in therapy and supervision, can improve the therapeutic relationship (Meyer & Pilkonis, 2002). This will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

So, to summarise, the main components that contribute to the quality and strength of the therapeutic relationship are: the affective bond and partnership; the cognitive consensus on goals and tasks; and the relationship history of the participants. Finally, a variety of terms have been used to conceptualise the therapeutic relationship. In this chapter we use these terms interchangeably: they include therapeutic relationship, working relationship, alliance, therapeutic alliance, and therapeutic bond.

Why study the therapeutic relationship?

The context for studying the therapeutic relationship is the interest in the more general question of why psychological therapies work. The therapeutic relationship has consistently been associated with treatment outcome, with correlations ranging from .21 to .29. This association is higher than associations between specific therapy techniques and outcome. Clients’ assessments of the relationship tend to be better predictors of outcome than therapist or observer ratings of the relationship, and measures of the relationship taken early in therapy are better predictors of outcome than measures taken later in therapy. Aspects of the therapeutic relationship that appear to be important in achieving good outcomes form the basis of a book titled Psychotherapy Relationships that Work (Norcross, 2002), and are discussed later.

The current challenges facing alliance researchers include trying to understand better how relationship factors work with other “common” and “specific” factors to help clients change. For example, there is a debate in the literature about the nature and importance of “non-specific” or “common” factors (see DeRubeis, Brotman, & Gibbons, 2005; Kazdin, 2005; and Wampold, 2005). These factors are so-called because they are thought to be common across most therapies. They include a treatment rationale, expectations of improvement, a treatment ritual and the therapeutic relationship (Frank, 1961; Lambert & Ogles, 2004). As stated above, these factors have been consistently associated with outcome, are assumed by many to be important in helping clients change, and importantly, would lead to non-significant differences between treatments (Stiles, Shapiro, & Elliott, 1986). However, there is some debate about this. DeRubeis et al. (2005) argue that psychotherapies, particularly CBT, work, to a greater extent than the supporters of common factors claim, through techniques specific to a therapy. A good therapeutic alliance, they suggest, may be a product of good outcome rather than the other way round.

In an attempt to bring together this discussion, Castonguay & Holtforth (2005) make a number of points. First, within each of the broad categories of factors, such as alliance or technique, there are many variables, which may vary in their usage with different therapies. It is in some sense artificial to separate out these factors, as techniques always happen within a relationship. It is perhaps then more useful to see components of the therapeutic relationship as elements of the set of skills a therapist has to be used, when appropriate, to help clients change.

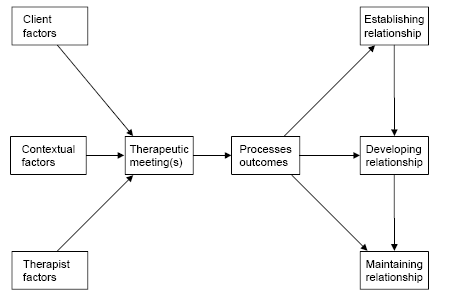

Figure 2.1 Conceptual map.

How does the therapeutic relationship work?

In this third section, which constitutes the substantive portion of this chapter, we report on the findings of a systematic search of the literature for review articles pertaining to the client-therapist relationship that were then used to map out the domains and concepts of the therapeutic relationship. The electronic search was conducted on PsycINFO. Two research workers sifted all identified references and the final list of references was rated for their degree of relevance on a five-point scale. All (45) top and (67) next rated articles were summarised (details of the search strategy and findings can be found in Cahill (2003)), and from these summaries the “map” of the therapeutic relationship was formulated. This map is described below and summarised in Figure 2.1.

Three main stages of the relationship are used to organise the research findings. These are: establishing a relationship, developing a relationship, and maintaining a relationship. We have listed key processes involved in establishing what might be called “mini outcomes” or objectives for each of the three stages. It is assumed that although these stages develop across therapy, there will also be a cycling through these stages within a therapeutic meeting, or over a number of weeks or months. For example, a therapeutic relationship may be well developed but a break in treatment may result in client-reported dissatisfaction. The therapist will work to repair this rupture in the relationship and may also return to the use of engagement skills described in establishing a relationship. In addition to describing stages in the development of the therapeutic relationship, we will briefly consider broader therapist, client and contextual factors within which the therapeutic interactions take place.

Table 2.1 Establishing the relationship

Establishing a relationship

There is clear evidence that the early development of a good relationship between therapist and client predicts better outcome and helps clients to remain in therapy (Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000). Client engagement in therapy is the primary aim at the beginning of therapy and can be divided into the following objectives: expectancies, intentions, motivation and hope (Table 2.1). It is important to build clients’ positive expectations of therapy, both role (what is expected of the client and therapist) and outcomes (Garfield, 1974; Arnkoff, Glass, & Shapiro, 2002). For example, higher client expectations of therapy predicted outcome in CBT group therapy for social phobia (Safren, Heimberg, & Juster, 1997). It is also important to develop clients’ intentions and motivation for change (Whiston & Coker, 2000). In an interesting study looking at client and therapist microprocesses during the first therapy session, the earlier that emotional involvement and meaningful connection (independently rated) were established, the better the alliance was as rated by clients (Sexton, Littauer, Sexton, & Tommeras, 2005).

There have been a number of studies looking at what therapists find important in enabling early client involvement in therapy. For example, two studies have found that therapists rate clients as more attractive if they are seen to be motivated to change and such clients are likely to become better engaged in therapy (Davis, Cook, Jennings, & Heck, 1977; Tryon, 1990). Further studies have found that good relationship ratings in early therapy sessions were associated with high levels of client working and of client involvement (Reandeau & Wampold, 1991).

Finally, developing clients’ sense of hope is associated with remaining in therapy and with better outcomes. Kuyken (2004), for example, found that clients who expressed high levels of hopelessness at the beginning of therapy, which did not reduce over the first few sessions, had significantly worse outcomes than clients whose hopelessness reduced in this initial period.

Also, therapists’ expressed hope for the usefulness of therapy is important in engaging clients in therapy (Russell & Shirk, 1998). This links to client expectancies (Garfield, 1974; Winston & Muran, 1996), which in turn increases therapists’ abilities to influence clients (Puskar & Hess, 1986). Nathan (1999) examined hope in relation to difficult clients, and found that therapists often lack hope with such clients, which leads to impoverished therapeutic relationships. The importance of openly addressing hope or the lack of it with clients is discussed by Bordin (1979). For example, improvements in the client–therapist relationship were evidenced when the early building of a sense of hope with clients was achieved (Everly, 2001).

Therapist behaviours that are associated with the above objectives of intentions, expectancies, motivation and hope include the three elements of Rogers’ therapeutic conditions: warmth, genuineness or respect, and empathy (Bachelor & Horvath, 1999; Rogers, 1957). Empathy is particularly linked to good engagement and is described as the ability of the therapist to enter and understand, both affectively and cognitively, the client’s world (Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, & Watson, 2002). In a meta-analysis on available research, empathy accounted for between 7% and 10% of the variance in outcome (Bohart et al., 2002). Unexpectedly, this meta-analysis also found some evidence for empathy being more important in the outcome of CBT than of other therapies. Why this might be is still an open question.

Engagement also involves the therapist discussing and agreeing the aims of therapy with the client. There is evidence that it is important to reach consensus early in therapy. For example, early session information gathering and later session sharing and negotiation of problem formulation and treatment plans have been found to improve engagement and return for further sessions of therapy (Tryon, 2002). In an earlier study, Tracy (1977) compared two types of initial interview, one where therapists gathered information but did not share their understandings and one where therapists shared their understandings of the client’s problems and negotiated treatment goals. Clients were significantly more likely to return for therapy if they had attended the latter interviews. The early agreement on goals, however, is not so strongly linked with overall treatment outcome. For example, Gaston, Marmar, Gallagher, & Thompson (1991) did not find a significant association between early goal consensus and outcome.

There is evidence that mutual involvement in the helping relationship is even more important than goal consensus for engaging clients in therapy and in gaining positive treatment outcome. Therapist behaviours that are associated with this development of a collaborative framework include: talking rather than remaining silent; encouraging client experiencing so that sessions are reported as being “deep”; and avoiding conflict within the sessions (Tryon & Winograd, 2001, 2002). Mutual involvement has also been assessed through homework completion, with a number of studies showing that clients who are better at attempting to do their homework between sessions have fewer symptoms at the end of therapy (Worthington, 1986; Schmidt & Woolaway-Bickel, 2000).

Table 2.2 Developing the relationship

Over half of the reviews considered discuss the importance of offering support to clients. Aspects of support that are described as being important within cognitive and behavioural therapies include tolerance (Mallinckrodt, 2000) and guidance (Luborsky, 1990). Therapist affirmation and positive regard are other aspects of support. Farber and Lane (2002) reviewed the research in this area and conclude that there is a positive but modest association between positive regard and outcome. Other techniques that improve client engagement include providing early clarifications in the here and now (Waldinger, 1987) and using client preparatory techniques, such as information sheets and educational sessions (Heitler, 1976).

Developing a relationship

At the second stage we consider therapists’ techniques and objectives that are helpful in progressing therapy and developing the client–therapist relationship (see Table 2.2). Once clients are hopeful that therapy may help and are motivated to change, it is important that they are able to turn to the tasks of the developing of the therapeutic relationship. To do this they need to have trust in the therapist, openness to the process of therapy and a commitment to working with their therapist. These, then, provide the objectives of this second stage of therapy. Therapist engagement and relationship development behaviours described in the previous section of course continue to be important. Clients who show good engagement in therapy are more likely to follow through therapeutic tasks (Corrigan, Dell, Lewis, & Schmidt, 1980; Ross, 1977). In contrast, defensiveness and hostility have been negatively linked to the quality of the client’s working relationship (Binder & Strupp, 1997).

Important techniques at this stage include exploration and reflection of aspects of the client–therapist relationship. These methods are generally emphasised by psychodynamic, interpersonal and humanistic therapies (Blagys & Hilsenroth, 2000; Blos, 1972; Dozier & Tyrrell, 1998; Enns, Campbell, & Courtois, 1997; Ogrodniczuk & Piper, 1999). There is some evidence to show that therapists who do not manage their counter-transference issues have less good alliances than therapists who successfully manage such issues (Ligiero & Gelso, 2002). Countertransference here is defined as “internal and external reactions in which unresolved conflicts of the therapist, usually but not always unconscious, are implicated” (Gelso & Hayes, 2002, p. 269). Management of countertransference issues consists of five interrelated factors: self-insight, self-integration, empathy, anxiety management, and conceptualising ability (Van Wagoner, Gelso, Hayes, & Diemer, 1991).

“Mutual affirmation” is seen as important therapist activity (Kolden, Howard, & Maling, 1994). Positive feedback also helps establish and strengthen the relationship (Claiborn, Goodyear, & Horner, 2001; Schaap, Bennun, Schindler, & Hoogduin, 1993). Feedback is usefully conceptualised as an influence process where the therapist changes the client’s behaviour through the delivery of discrepant, change-promoting messages or positive reinforcement of aspects of the client’s behaviour or self-beliefs. The feedback message can be descriptive or inferential. Research evidence indicates that descriptive feedback is more useful and positive feedback is generally more acceptable (although negative feedback can be useful if preceded by positive feedback). Ogrodniczuk & Piper (1999) discuss the fact that, when working with clients with personality disorders, therapists must balance transference work with supportive work, such as reassurance and praise.

Finally, relational interpretations are a therapy technique where the therapist makes an intervention that addresses interpersonal links, connections or themes within clients’ stories. A number of studies have linked the use of relational interpretations, particularly those that address the central interpersonal theme of the client, to positive outcome and to the quality of the alliance (for example, see review by Crits-Christoph & Connolly, 1999).

Maintaining a relationship

The objectives or outcomes of the client–therapist interactions at the third stage of our model include: client continued satisfaction with the relationship; a productive and positive working alliance; increased ability for clients to express their emotions and to experience a changing view of self with others (see Table 2.3). The first objective includes general satisfaction with and positive appraisal of the relationship (Hill & Williams, 2000; McGuire, McCabe, & Priebe, 2001). Clients’ relationship satisfaction is associated with their satisfaction with therapy in general (Reis & Brown, 1999). It is an experiential rather than a behavioural phenomenon. Clients tend to be less discriminating than therapists about the quality of their relationship, forming a global positive or negative impression of the relationship (Bachelor & Horvath, 1999). Dissatisfaction with the relationship is the most frequent reason given for leaving therapy and for non-compliance (Reis & Brown, 1999).

Table 2.3 Maintaining the relationship

The second objective is referred to as the alliance (working, therapeutic, etc.). We discussed some aspects of the alliance at the beginning of the chapter. Although there are important differences in the definitions of the alliance (Horvath & Bedi, 2002), a major controversy exists as to whether the alliance arises from the interpersonal process or is an intrapsychic phenomenon (Saketopoulou, 1999), with different therapies emphasising different aspects of the alliance. However, it does appear that it is the quality and strength of the collaborative relationship between client and therapist that is the most important (Winston & Muran, 1996).

The third objective is emotional expression and emotional acceptance (see Greenberg, Chapter 3; Swales and Heard, Chapter 9; Pierson and Hayes, Chapter 10, this volume). For some therapies the relationship is the vehicle for emotions to be supported and expressed. The emotional relationship is seen as a cathartic experience (Garfield, 1974; Truax, 1967), although for some the emotional experience leads to change in cognitions and self-understanding and for others experiential insight is the key to change (Warwar & Greenberg, 2000; Winston & Muran, 1996). The final objective, which has been described in a number of reviews, is to enable the client to explore alternative views of themself. These are sometimes referred to as narrative truths: social constructionists describe the processes in therapy as the client and therapist constructing the relationship together, where old problems are deconstructed and new narratives arise (Crits-Christoph, 1998; McGuire et al., 2001; Stiles, Honos-Webb, & Surko, 1998).

As therapy progresses it is likely that difficulties in the relationship will arise (Katzow and Safran, Chapter 5, this volume; Safran, Muran, Samstag, & Stevens, 2001). Although these are common, therapy may be impeded if the problems are not resolved. Indeed resolution appears to lead to a deeper and better relationship and better treatment outcome (Safran et al., 2001). Kivlighan and Shaughnessy (2000) and Stiles et al. (2004) found that the pattern of alliance ratings that went from high to low and back to high had the best association with good outcome.

Possible threats to the relationship have been grouped into: therapist behaviours, client behaviours and relationship challenges. The therapist actions needed to avoid or resolve these threats are grouped as self-refection, metacommunication, flexibility and repair. These threats and therapist actions are discussed below.

Therapists may have negative feelings about their clients that are not spoken about but can still have a detrimental impact on the alliance (Gelso & Carter, 1985; Safran et al., 2002). If these feelings are recognised, owned and explored, therapists report positive consequences (Greenberg, Chapter 3, this volume; Harris, 1999). Other therapist behaviours that clients have described as intrusive and defensive and as having a negative impact on the relationship include therapists imposing their own values, making irrelevant comments, and being critical, rigid, bored, blaming, moralistic, or uncertain (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001). Poor use of therapeutic techniques, such as continued application of a technique when not accepted or found helpful by the client or poor use of silence, is linked with a poor therapeutic relationship (Binder & Strupp, 1997; McLennan, 1996).

Clients also tend to hide their negative feelings (such as fear, hostility, and anger) and often the therapist is unaware of what the client is feeling. Such client deference to the therapist has been linked with poor outcome (Binder & Strupp, 1997; Beutler, Clarkin, & Bongar, 2000; Warwar & Greenberg, 2000). This type of behaviour has sometimes been termed “client resistance”. Resistance was originally developed as a psychoanalytic concept of the client’s unconscious avoidance of the analytic work. It was later developed in social psychology as a theory of psychological reactance that was seen as a normal reaction to a perceived threat. Social influence theory defined the concept of resistance as a product of incongruence between the therapist’s behaviour and the power or legitimacy ascribed to the therapist. In their review of the literature, Beutler, Moleiro, and Talebi (2002) conclude that therapy is most effective if therapists “can avoid stimulating the patient’s level of resistance” (p. 139) through adjusting how directive they are in their interventions.

Relationship challenges often occur when there are misunderstandings between clients and therapists on the goals and tasks of therapy. Such disagreements may result in confrontations and client withdrawal (Bachelor & Horvath, 1999; Safran et al., 2001). Such ruptures in therapy are common and should be an expected part of treatment (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001; Bachelor & Horvath, 1999; Binder & Strupp, 1997; Hill & Williams, 2000; Katzow & Safran, Chapter 5, this volume). Therapist recognition of a rupture in the relationship is an important first step towards resolution. This involves therapists being able to reflect on their own position in therapy and their feelings about the client and how therapy is progressing (Binder & Strupp, 1997).

The importance of repairing ruptures has been mentioned above. Safran and Muran (1996) have developed a model of rupture resolution, which provides four stages: attending to the rupture marker, exploring the rupture experience, exploring avoidance and emergence of a wish or need. Evidence for this model has been found in a number of studies (see Safran et al. (2001) for a review). Aspland, Llewelyn, Hardy, Barkham, and Stiles (2006) looked at rupture repair sequences in CBT and found that, contrary to Safran’s model, therapists did not openly discuss the rupture with clients.

Of paramount importance in maintaining the relationship is the therapist’s ability to tailor therapy to the individual needs and characteristics of clients. This involves therapists responding appropriately to relational fluctuations so that negative reactions are contained and managed. For example, therapists’ inflexible adherence to treatment strategies (either cognitive or interpretations) is associated with poor relationships (Stiles et al., 1998). Appropriate responsiveness and flexibility are seen as important in maintaining the therapeutic relationship (Davis, 1991; Stiles et al., 1998).

Contextual factors

There are also broader client, therapist and contextual factors that impact on the quality of the therapeutic relationship. Two of the main client characteristics found to moderate treatment outcome and poor therapeutic relationships are functional impairment and coping style (Beutler, Harwood, Alimohamed, & Malik, 2002). Functional impairment includes problems in work, social and intimate relationships. The more difficulties clients have in these areas, the less likely they are to benefit from therapy. Problem complexity has also been associated with poor relationship development (Kilmann, Scovern, & Moreault, 1979). For such clients to be able to benefit from therapy, treatment often needs to be of more than six months in length to give time for the therapeutic relationship to develop.

Therapist characteristics that are associated with negative aspects of the client–therapist relationship include being rigid, uncertain, distant, tense, and distracted, and level of experience (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001). A further significant therapist factor related to negative outcome is therapists’ underestimating the seriousness of clients’ problems (Beutler & Clarkin, 1990). As has been stated, therapists who stick rigidly to therapy techniques when there are relationship ruptures rather than exploring the nature of the relationship problem are less likely to achieve satisfactory client outcomes.

Clients’ and therapists’ attachment style has been found to influence the quality of the therapeutic relationship, with clients who have insecure attachment styles less able to form satisfactory alliances (Eames & Roth, 2000). Hardy, Cahill, Shapiro, Barkham, Rees, & Macaskill (2001) found that clients with an underinvolved interpersonal style (avoidant) did less well in CBT, and that this relationship between interpersonal style and outcome was mediated by the therapeutic alliance. There is also some evidence that therapists’ attachment style impacts on the quality of the relationship formed with clients. For example, therapists who have an insecure, overinvolved attachment style tend to respond less empathically to clients than secure therapists (Rubino, Barker, Roth, & Fearon, 2000).

At the broader level, cultural and demographic variables have been found to have an impact on the therapy relationship. Although the evidence is limited, clients from minority groups are less likely to remain in therapy and tend to drop out prematurely (Bernstein, 2001; Draguns, 1997; Heitler, 1976; Margolese, 1998; Peltzer, 2001; Spector, 2001; Reis & Brown, 1999). Again there is little research on whether clients should be matched with therapists from the same ethnic background, social class, religion, etc. Sue and Lam (2002) report a number of studies that suggest that matching of therapist and client in terms of cultural background may improve outcome and decrease premature termination of therapy. There is some evidence that perceived similarity with one’s therapist results in greater satisfaction (Bernstein, 2001). For example, similarity in social class between therapist and clients has been linked with the formation of a better therapeutic relationship (Gardner, 1964), although two further reviews concluded that social class did not impact on the quality of the relationship (Harrison, 1975). There is also some evidence that perspective and attitude convergence and positive complementarity are associated with higher ratings of the relationship and better outcome (Bachelor & Horvath, 1999; Whiston & Coker, 2000; Crastnopol, 2001; Reis & Brown, 1999). Positive complementarity involves both reciprocity in terms of control and correspondence in terms of affiliation (Hill & Williams, 2000).

Finally, many of the reviews mention the importance of influence in the therapeutic relationship. Keijsers, Schaap, & Hoogduin (2000) describe effective behaviour therapists as being influential. This process is linked to social influence theory or the ability of the therapist to influence the client on the basis of social power. Influence is also linked to the credibility of the therapist (McGuire et al., 2001; Corrigan et al., 1980). In addition, power has been described as the vital force in therapy (Puskar & Hess, 1986). Power in this context includes that offered through the role and status of the therapist, and the negotiated power through agreement of the therapy contract and through the therapist’s interaction. Clients, through their engagement in and compliance with their role and respect they offer to therapists, legitimise the power then given to the therapist. From a different perspective, therapists working within a social constructionist framework aim to empower (or enable) clients (Sexton & Whiston, 1994). It is this social influence aspect of the therapist’s role that is put forward as being the route through which computer/internet therapies achieve success (Binik et al., 1997).

It is also possible to link the concept of power to ruptures in the relationship. Gilbert (1993, 2000) describes how our interactions with others are influenced by our perceived social status or rank. Clients are likely to feel inferior to their therapist. If they experience a difficulty in their therapeutic relationship this may result in feelings of shame and humiliation, which may be hidden for fear of losing status in the relationship.

Conclusion

The establishment of a good relationship is necessary from the first stages of therapy. An exploration of the research on the therapeutic relationship suggests that clients tend to emphasise the importance of therapist warmth and emotional involvement, while therapists judge the quality of the relationship in terms of clients’ active participation and collaboration. Together, these make the primary components of the initial objectives for the first stage in the relationship: expectancies, intentions and hope. As therapy continues, the second stage of the relationship develops into one in which therapeutic activity is carried out. This leads to a deepening of the therapist–client relationship, but also, as the relationship shifts into the third stage, leads to misunderstandings, conflicts, activation of defences, negative reactions and ruptures. Maintaining the quality of the relationship through the various stages of therapy involves therapists ensuring they are appropriately responsive to their clients, able to recognise and seek to repair ruptures in the relationship. Maintaining this complex developing and changing relationship requires therapists to individualise their responses to specific aspects of clients’ needs and relating styles. Therapist understanding and appreciation of contextual factors are also important for developing and maintaining the therapeutic relationship. Research suggests that it is the blending of these various skills that makes for a good therapeutic relationship, which in turn will influence the outcome for the client. These findings are pertinent to all psychotherapies, including cognitive-behavioural-focused therapies.

References

Ackerman, S.J. & Hilsenroth, M.J. (2001). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques negatively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy, 38, 171–185.

Arnkoff, D.B., Glass, C.R. & Shapiro, S.J. (2002). Expectations and preferences. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 335–356). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aspland, H., Llewelyn, S., Hardy, G.E., Barkham, B. & Stiles, W.B. (2006). Alliance ruptures and resolution in CBT: A task analysis. Submitted for publication.

Bachelor, A. & Horvath, A. (1999). The therapeutic relationship. In M.A. Hubble & B.L. Duncan (eds), The heart and soul of change: What works in therapy (pp. 133–178). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Bernstein, D.M. (2001). Therapist-patient relations and ethnic transference. In W.S. Tseng & J. Streltzer (eds), Culture and psychotherapy: A guide to clinical practice (pp. 103–121). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Beutler, L.E. & Clarkin, J.F. (1990). Systematic treatment selection: Toward targeted therapeutic interventions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beutler, L.E., Clarkin, J.F. & Bongar, B. (2000). Guidelines for the systematic treatment of the depressed patient. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beutler, L.E., Harwood, T.M., Alimohamed, S. & Malik, M. (2002). Functional impairment and coping style. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 145–176). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beutler, L.E., Moleiro, C. & Talebi, H. (2002). Resistance. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 129–144). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Binder, J.L. & Strupp, H.H. (1997). “Negative process”: A recurrently discovered and underestimated facet of therapeutic process and outcome in the individual psychotherapy of adults. Clinical Psychology – Science & Practice, 4, 121–139.

Binik, Y.M., Cantor, J., Ochs, E. & Meana, M. (1997). From the couch to the keyboard: Psychotherapy in cyberspace. In S. Kiesler (ed.), Culture of the Internet (pp. 71–100). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Blagys, M.D. & Hilsenroth, M.J. (2000). Distinctive feature of short-term psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapy: A review of the comparative psychotherapy process literature. Clinical Psychology – Science & Practice, 7, 167–188.

Blos, P., Jr (1972). Silence: A clinical exploration. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 41, 348–363.

Bohart, A.C., Elliott, R.E., Greenberg, L.S. & Watson, J.C. (2002). Empathy. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 89–108). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bordin, E.S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16, 252–260.

Bordin, E.S. (1994).Theory and research in the therapeutic working alliance: New directions. In O. Horvath & L.S. Greenberg (eds), The working alliance. New York: Wiley.

Cahill, J. (2003). A review and critical appraisal of measures of therapist-patient interactions in mental health settings. National Co-ordinating Centre for Research Methodology, Birmingham, Final Report.

Castonguay, L.G. & Holtforth, M.G. (2005). Change in psychotherapy: A plea for no more “nonspecific” and false dichotomies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12, 198–201.

Claiborn, C.D., Goodyear, R.K. & Horner, P.A. (2001). Feedback. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38, 401–405.

Corrigan, J.D., Dell, D.M., Lewis, K.N. & Schmidt, L.D. (1980). Counseling as a social influence process: A review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27, 395–441.

Crastnopol, M. (2001). Convergence and divergence in the characters of analyst and patient: Fairbairn treating Guntrip. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 18, 120–136.

Crits-Christoph, P. (1998). The interpersonal interior of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 8, 1–16.

Crits-Christoph, P. & Connolly, M.B. (1999). Alliance and technique in short-term dynamic therapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 19, 687–704.

Davis, D.M. (1991). Review of the psychoanalytic literature on countertransference. International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy, 6, 143–151.

Davis, C.S., Cook, D.A., Jennings, R.L. & Heck, E.J. (1977). Differential attractiveness to a counseling analogue. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24, 472–476.

DeRubeis, R.J., Brotman, M.A. & Gibbons, C.A. (2005). Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12, 174–183.

Dozier, M. & Tyrrell, C. (1998). The role of attachment in therapeutic relationships. In J.A. Simpson & W.S. Rholes (eds), Attachment theory and close relationship (pp. 221–248). New York: Guilford Press.

Draguns, J.G. (1997). Abnormal behavior patterns across cultures: Implications for counseling and psychotherapy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21, 213–248.

Eames, V. & Roth, A. (2000). Patient attachment orientation and the early working alliance: A study of patient and therapist reports of alliance qualtiy and ruptures. Psychotherapy Research, 10, 421–434.

Enns, C.Z., Campbell, J. & Courtois, C.A. (1997). Recommendations for working with domestic violence survivors, with special attention to memory issues and posttraumatic processes. Psychotherapy, 34, 459–477.

Everly, G., Jr (2001). Personologic alignment and the treatment of posttraumatic distress. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 3, 171–177.

Farber, B.A. & Lane, J.S. (2002). Positive regard. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 175–194). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frank, J.D. (1961). Persuasion and healing. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Freud, S. (1940). The dynamics of transference. In J. Strachey (ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 12 (pp. 122–144). London: Hogarth.

Gardner, G.G. (1964). The psychotherapeutic relationship. Psychological Bulletin, 61, 426–439.

Garfield, S.L. (1974). What are the therapeutic variables in psychotherapy? Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 24, 372–378.

Gaston, L., Marmar, C.R., Gallagher, D. & Thompson, L.W. (1991). Alliance prediction of outcome: Beyond in-treatment symptomatic change as psychotherapy progress. Psychotherapy Research, 1, 104–112.

Gelso, C.J. & Carter, J.A. (1985). The relationship in counseling and psychotherapy: Components, consequences, and theoretical antecedents. Counseling Psychologist, 13, 155–243.

Gelso, C.J. & Hayes, J.A. (2002). The management of countertransference. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 267–284). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P. (1993). Defence and safety: Their function in social behaviour and psychopathology. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32, 131–153.

Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 7, 174–189.

Greenson, R.R. (1965). The working alliance and the transference neurosis. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 34, 155–181.

Hardy, G.E., Cahill, J., Shapiro, D.A., Barkham, M., Rees, A. & Macaskill, N. (2001). Client interpersonal and cognitive style as predictors of response to time limited cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 841–845.

Harris, A.H.S. (1999). Incidence and impacts of psychotherapists’ feelings toward their clients: A review of the empirical literature. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 12, 363–375.

Harrison, D.K. (1975). Race as a counselor-client variable in counseling and psychotherapy: A review of the research. Counseling Psychologist, 5, 124–133.

Heitler, J.B. (1976). Preparatory techniques in initiating expressive psychotherapy with lower-class, unsophisticated patients. Psychological Bulletin, 83, 339–352.

Hill, C.E. & Williams, E.N. (2000). The process of individual therapy. In S.D. Brown & R.W. Lent (eds), Handbook of counseling psychology, 3rd edition (pp. 670–710). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Holmes, J. (1996). Attachment, intimacy and autonomy: Using attachment theory in adult psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Arison.

Horvath, A. & Bedi, R. (2002). The alliance. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 37–70). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horvath, A.O. (1995). The therapeutic relationship: From transference to alliance. In Session – Psychotherapy in Practice, 1, 7–17.

Kazdin, A.E. (2005). Treatment outcomes, common factors, and continued neglect of mechanisms of change. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12, 164–188.

Keijsers, G.P.J., Schaap, C.P.D.R. & Hoogduin, C.A.L. (2000). The impact of interpersonal patient and therapist behavior on outcome in cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of empirical studies. Behavior Modification, 24, 264–297.

Kilmann, P.R., Scovern, A.W. & Moreault, D. (1979). Factors in the patient–therapist interaction and outcome: A review of the literature. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 20, 132–146.

Kivlighan, D.M. & Shaughnessy, P. (2000). Patterns of the working alliance development: A typology of clients’ working alliance ratings. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 362–371.

Klerman, G.L., Weissman, M.M., Rounsville, B.J. & Chevron, E.S. (1984). Interpersonal therapy of depression. New York: Basic Books.

Kolden, G.G., Howard, K.I. & Maling, M.S. (1994). The counseling relationship and treatment process and outcome. Counseling Psychologist, 22, 82–89.

Kuyken, W. (2004). Cognitive therapy outcome: The effects of hopelessness in a naturalistic study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 631–646.

Lambert, M.J. (1989). The individual therapist’s contribution to psychotherapy process and outcome. Clinical Psychology Review, 9, 469-485.

Lambert, M.J. & Ogles, B.M. (2004). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In M. Lambert (ed.), Bergin and Grafield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behaviour change, 5th edition (pp. 139–193). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Ligiero, D.P. & Gelso, C.J. (2002). Countertransference, attachment and the working alliance: The therapists’ contribution. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, and Training, 39, 3–11.

Luborsky, L. (1976). Helping alliance in psychotherapy. In J.L. Cleghorn (ed.), Successful psychotherapy (pp. 92–116). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Luborsky, L. (1990). Theory and technique in dynamic psychotherapy: Curative factors and training therapists to maximize them. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 53, 50–57.

Luborsky, L.B. (1994). Therapeutic alliances as predictors of psychotherapy outcomes. In O.A. Horvath & L.S. Greenberg (eds), The working alliance: Theory, research and practice. New York: Wiley.

Mace, C. & Margison, F. (1997). Attachment and psychotherapy: An overview. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70, 576–617.

McGuire, R., McCabe, R. & Priebe, S. (2001). Theoretical frameworks for understanding and investigating the therapeutic relationship in psychiatry. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36, 557–564.

McLennan, J. (1996). Improving our understanding of therapeutic failure: A review. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 9, 391–379.

Mallinckrodt, B. (2000). Attachment, social competencies, social support, and interpersonal process in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 10, 239–266.

Margolese, H.C. (1998). Engaging in psychotherapy with the Orthodox Jew: A critical review. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 52, 37–53.

Martin, D.J., Garske, J.P. & Davis, M.K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 438–450.

Meyer, B. & Pilkonis, P.A. (2002). Attachment style. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 367–383). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nathan, R. (1999). Scientific attitude to ‘difficult’ patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 87.

Norcross, J. (2002). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ogrodniczuk, J.S. & Piper, W.E. (1999). Use of transference interpretations in dynamically oriented individual psychotherapy for patients with personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 13, 297–311.

Peltzer, K. (2001). An integrative model for ethnocultural counseling and psychotherapy of victims of organized violence. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 11, 241–262.

Puskar, K.R. & Hess, M.R. (1986). Considerations of power by graduate student nurse psychotherapists: A pilot study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 8, 51-61.

Reandeau, S.G. & Wampold, B.E. (1991). Relationship of power and involvement to the working alliance: A multiple-case sequential analysis of brief therapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 107–114.

Reis, B.F. & Brown, L.G. (1999). Reducing psychotherapy dropouts: Maximizing perspective convergence in the psychotherapy dyad. Psychotherapy, 36, 123-136.

Ross, M.B. (1977). Discussion of similarity of client and therapist. Psychological Reports, 40, 699–704.

Rogers, C.R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 22, 95–103.

Rubino, G., Barker, C., Roth, T. & Fearon, P. (2000). Therapist empathy and depth of interpretation in response to potential alliance ruptures: The role of therapist and patient attachment styles. Psychotherapy Research, 10, 408–420.

Russell, R.L. & Shirk, S.R. (1998). Child psychotherapy process research. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology, 20, 93–124.

Safran, J.D. & Muran, J.C. (1996). The resolution of ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 447–458.

Safran, J.D., Muran, J.C., Samstag, L.W. & Stevens, C. (2001). Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38, 406–412.

Safran, J.D. & Segal, Z. (1990). Interpersonal processes in cognitive therapy. New York: Basic Books.

Safren, S.A., Heimberg, R.G. & Juster, H.R. (1997). Clients’ expectancies and their relationship to pretreatment symptomatology and outcome in cognitive-behavioral group treatment for social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 694–698.

Saketopoulou, A. (1999). The therapeutic alliance in psychodynamic psychotherapy: Theoretical conceptualizations and research findings. Psychotherapy, 36, 329–343.

Schaap, C., Bennun, I., Schindler, L. & Hoogduin, K. (1993). The therapeutic relationship in behavioural psychotherapy. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Schmidt, N.B. & Woolaway-Bickel, K. (2000). The effects of treatment compliance on outcome in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 68, 13–18.

Sexton, H., Littauer, H., Sexton, A. & Tommeras, E. (2005). Building the alliance: Early process and the client-therapist connection. Psychotherapy Research, 15, 103–116.

Sexton, T.L. & Whiston, S.C. (1994). The status of the counseling relationship: An empirical review, theoretical implications, and research directions. Counseling Psychologist, 22, 6–78.

Spector, R. (2001). Is there a racial bias in clinicians’ perceptions of the dangerousness of psychiatric patients? A review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health, 10, 5–15.

Stiles, W.B., Glick, M.J., Osatuke, K., Hardy, G.E., Shapiro, D.A., Agnew-Davies, R., Rees, A. & Barkham, M. (2004). Patterns of alliance development and the rupture-repair hypothesis: Are productive relationships U-shaped or V-shaped? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 81–91.

Stiles, W.B., Honos-Webb, L. & Surko, M. (1998). Responsiveness in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology – Science & Practice, 5, 439–458.

Stiles, W.B., Shapiro, D.A. & Elliott, R. (1986). Are all psychotherapies equivalent? American Psychologist, 41, 165–180.

Sue, S. & Lam, A. (2002). Cultural and demographic diversity. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 401–422). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sweet, A.A. (1984). The therapeutic relationship in behavior therapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 4, 253–272.

Truax, C.B. & Carkhuff, R.R. (1967). Toward effective counseling and psychotherapy. Chicago: Aldine.

Tryon, G.S. (1990). Session depth and smoothness in relation to the concept of engagement in counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37, 248–253.

Tryon, G.S. (2002). Engagement in counseling. In G.S. Tryon (ed.), Counseling based on process research: Applying what we know (pp. 1–26). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Tryon, G.S. & Winograd, G. (2001). Goal consensus and collaboration. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38, 385–389.

Tryon, G.S. & Winograd, G. (2002). Goal consensus and collaboration. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients (pp. 109–125). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Wagoner, S.L., Gelso, C.J., Hayes, J.A. & Diemer, R. (1991). Countertransference and the reputedly excellent psychotherapist. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 28, 411–421.

Waldinger, R.J. (1987). Intensive psychodynamic therapy with borderline patients: An overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 267–274.

Wampold, B.E. (2005). Establishing specificity in psychotherapy scientifically: Design and evidence issues. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12, 194-197.

Warwar, S. & Greenberg, L.S. (2000). Advances in theories of change and counseling. In S.D. Brown & R.W. Lent (eds), Handbook of counseling psychology, 3rd edition (pp. 571–600). New York: Wiley.

Whisman, M.A. (1993). Mediators and moderators of change in cognitive therapy of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 248–265.

Whiston, S.C. & Coker, J.K. (2000). Reconstructing clinical training: Implications from research. Counselor Education & Supervision, 39, 228–253.

Wilson, G.T. (1984). Clinical issues and strategies in the practice of behavior therapy. Annual Review of Behavior Therapy: Theory & Practice, 10, 291–320.

Winston, A. & Muran, J.C. (1996). Common factors in the time-limited psychotherapies. American Psychiatric Press Review of Psychiatry, 15, 43–68.

Worthington, E.L. (1986). Client compliance with homework directives during counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33, 124–130.

Young, J.E. & Beck, A.T. (1988). Revision of the Cognitive Therapy Scale. Unpublished manuscript, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.