Chapter 11

Schematic mismatch in the therapeutic relationship

A social-cognitive model

Robert L. Leahy

Introduction

In the past decade cognitive-behavioral therapists have recognized the therapeutic relationship as an important component of the process of change (Gilbert, 1992; Gilbert & Irons, 2005; Greenberg, 2001; Leahy, 2001, 2005b; Safran, 1998; Safran & Muran, 2000). Each of these models implies that the current therapeutic relationship is reflective of earlier or current relationships – similar to the psychoanalytic concept of “transference” (Menninger & Holzman, 1973). The transference relationship consists of all personal and interpersonal processes that occur in the relationship between the patient and therapist. These processes include personal schemas about the self (inadequate, special, helpless), interpersonal schemas about others (superior, judgmental, nurturing), intrapsychic processes (repression, denial, displacement), interpersonal strategies (provoking, stonewalling, clinging), and past and present history of relationships that affect how the current therapeutic relationship is experienced.

The transference relationship in therapy also depends on the particular therapeutic modality that is employed: thus, in some psychoanalytic therapies, the patient may be given little direction except to allow various thoughts and feelings to come into consciousness via free association. In contrast, most cognitive-behavioral therapies entail some directive process, such as Socratic questioning and dialogues, with explicit guidelines in the form of session agendas, bibliotherapy, socialization to the model, direct examination and testing of thoughts, and self-help homework assignments (Beck, 1995; Leahy, 2001, 2003a). Although all therapies implicitly promise change that will be facilitated by the therapist, CBT explicitly calls on the patient to actively engage with current thoughts, feelings, relationships, and behavior. As a consequence of these expectations and therapeutic procedures of the CBT model, non-compliance or resistance may take specific forms.

The therapeutic relationship is a co-construction that is shaped via interactional sequences. An interactional sequence occurs when the therapist and patient are reacting moment-to-moment with each other. For example, the therapist points out a type of negative thought but the patient experiences this as a criticism and withdraws. The therapist may react to this withdrawal by backing away or by being more dominant. In this chapter I will review common dimensions of confusion, disappointment, conflict, and resistance in the therapeutic relationship that emerge from these sequences. Of specific focus in this chapter are the personal schemas and emotional schemas that both patient and therapist bring to the relationship, and how these individual schemas can create mismatches and thus disrupt interactions that can interfere with treatment. I utilize a game metaphor that suggests that patient and therapist follow their own implicit rules as interactional sequences unfold that may result in self-fulfilling prophecies about their own personal schemas. Finally, I will identify some interventions that may be useful in overcoming these potential roadblocks in treatment.

Dimensions of resistance in the relationship

Non-compliance, resistance, or lack of progress in therapy can be understood, to some extent, as a result of strategies and roles that the patient activates to affirm personal schemas, avoid further loss, and defend themselves (Leahy, 2001, 2003a). The assumption here is that patients are trying to protect themselves from further loss, disappointment, or criticism or that they are seeking desired outcomes (for example, validation, legitimacy, moral sanction) from the therapist. I have identified seven common patterns of resistance that interfere with progress, as follows.

- Validation resistance. The patient gets stuck by demanding that the focus is exclusively on validating pain. The patient may view suggestions for alternative action or thought as invalidating: “You don’t understand how bad it feels.” Failures in validation lead to escalation of complaints and suffering until validation is obtained. Patients may have unique and self-defeating “rules” for validation, such as “You can only validate me if you agree that it is hopeless.” Potential conflicts between the therapist and patient may arise when the therapist becomes task-oriented and views validation as interfering with valued goals. Interventions for validation resistance include recognizing the need for validation, and asserting to the patient that therapy involves a dilemma – both validating the pain and encouraging change – and that the patient may be using self-defeating strategies to elicit validation (for example, complaining, catastrophizing, or withdrawing) (Leahy, 2001).

- Victim resistance. Here the patient believes that his identity is defined only by being a victim, and that he can do nothing to make things change, because he was not the cause of his problem. The person stuck in this role will have specific rules for how change has to come about: “Other people will have to apologize and make compensation. That’s how I can get better.” Attempts to move the patient toward individual change only lead the patient to view the therapist as another malicious victimizer. Interventions that are useful include acknowledging the legitimacy of the patient’s complaint that he is in fact a victim, but that he can also empower himself by focusing on personal goals and the current resources available (Leahy, 2001).

- Moral resistance. In this situation the patient believes that change would run the risk of violating one’s own moral or ethical standards. This is especially the case in obsessive–compulsive or perfectionistic patients who believe that their inflated sense of responsibility and fear of making a mistake are based on a moral code. Thus, the therapist who encourages the patient to abandon demanding standards of perfection may be viewed as facilitating irresponsible and reprehensible qualities in the patient.While recognizing that there are legitimate “shoulds” that guide behavior, the therapist can help the patient recognize that his absolutistic, perfectionistic “shoulds” violate a universal moral code of enhancing human dignity and assuring fairness. Thus, the therapist need not reject “moral resistance,” but rather can assert a more “rational” and “reasonable” moral code that recognizes human differences and needs (Leahy, 2001; Nussbaum, 2005; Rawls, 2001).

- Schematic resistance. In this role, the patient’s personal schemas limit change, since the patient has a confirmatory bias in viewing past, present and future as evidence that maladaptive personal schemas are valid. For example, the patient who views the self as “helpless” selectively recalls past evidence of ineptitude and failure, views current life primarily in terms of inertia, and predicts that the future will be just as barren, thus “justifying” avoidance and procrastination. The patient’s response to suggestions is, “You don’t realize. I really am helpless.” (This can be similar to the patient’s underlying fear of becoming more powerful and less helpless (Gilbert & Irons, 2005).) In this case the therapist can utilize techniques to modify persistent schemas, such as examining the origin of schemas, developing alternative adaptive schemas, and experimenting with acting against the schema (Leahy, 2001; Leahy, Beck, & Beck, 2005; Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2003).

- Self-consistency. All of us like to believe that there is some predictability in life – which is one reason why schemas are “conservative” in nature. A particular kind of self-consistency in resistance is the tendency to justify past failed decisions – a process known as “sunk costs.” In this situation, the patient claims that he cannot walk away from a string of bad commitments because he has already invested too much (in his failure). “I can’t leave, because I’ve already put too much time into this.” Since the therapist does not have past mistakes to justify, it may be difficult for her/him to understand how difficult it is for the patient to abandon a prior commitment that has only proved to be a lost sunk cost. Interventions to modify commitment to sunk costs include consideration of rejecting a commitment as an opportunity for new rewards, stepping away from one’s own commitment by considering the advice one would give a friend, and considering if one would take on the commitment if one could start over (Leahy, 2001, 2004a).

- Risk-aversion. All change involves an increase in uncertainty, since what is not known is expected to have greater variability than what is known. Resistant individuals often engage a risk-averse strategy of decision-making. This includes high information demands, selective focus on likelihood and magnitude of negative outcomes, high focus on regret, and low value and estimation of positive utility: “I really need to know more because it could very likely be really terrible if it did not work out and I would blame myself. And, for what? How much would I really enjoy it if it did happen the way you suggest?” Individuals with risk-averse strategies are more likely to be depressed, anxious, worried, or to score higher on the Millon Multiaxial Scale on avoidant, dependent, or borderline personality disorder (Leahy, 2002, 2003a, 2005a; Leahy & Napolitano, 2005). These individuals utilize strategies of reassurance-seeking, waiting, stopping-out quickly, quitting “while ahead,” and devaluing positive change to avoid their “expectations getting ahead of them.” The therapist and patient may face conflicts when the therapist’s suggestions for behavioral activation and change are viewed as presenting unacceptable risks to the patient, who believes he has already lost enough. Interventions include evaluation of alternative and more flexible views of calculating reasonable risks and opportunities for change and to avoid “stopping-out” or quitting too early (Leahy, 2001, 2004a). As noted above, what is key is exploring the “fear of change,” and to see these kinds of resistances in terms of safety strategies (Gilbert, Chapter 6, this volume).

- Self-handicapping. Some patients come to therapy with the apparent abilities to be successful, but with a history of limited and self-sabotaging behavior. Often labeled “masochistic” or “self-defeating,” these patients either openly resist attempts to change or make half-hearted efforts that are doomed to fail. In some cases, this strategy may reflect an attempt to obscure being evaluated at one’s best behavior. It is better to fail with limited effort, since one can always claim “I didn’t really care” or “I didn’t really try,” thus preserving some self-esteem based on what one could do under the best conditions. The therapist can assist the patient in examining the patterns of self-handicapping, evaluating the global and shame-based ideas of “failure,” and help the patient make slow progress to avoid “getting ahead of myself“ (Leahy, 2001).

We shall keep these seven dimensions of resistance in mind as we later explore schematic mismatches in therapy. For example, the patient with validation and victim resistance issues will feel especially frustrated with a therapist with demanding standards who views some emotions as “whining“ or “self-indulgent.” Thus, certain dimensions of resistance may be augmented by the therapist’s counter-transference. We will examine this later in this chapter.

Schematic model of personality

The schematic processing model has been extended to an understanding of personality disorders (Beck et al., 2003; Leahy et al., 2005; McGinn & Young, 1996; Pretzer & Beck, 2004; Young et al., 2003). Influenced by the ego analysts – such as Alfred Adler (1924/1964), Karen Horney (1945, 1950), Harry Stack Sullivan (1956), and Victor Frankl (1992) – the cognitive model of personality stresses the importance of how thinking is organized to influence and be influenced by affect, behavior and interpersonal relationships. Various dimensions of personality that are linked to vulnerabilities to psychopathologies can be understood in terms of specific schemas (for example, feeling helpless and needing others is linked to dependent personality). In contrast, seeing self as unique and superior is linked to narcissism. Various strategies flow from these self–other schematic representations – for example, the dependent patient is deferential and clinging, while the narcissistic patient is exploitative and confrontational.

Specific personality “disorders” operate differently in the transference relationship. For example, the dependent patient, fearing abandonment and isolated helplessness, may seek considerable reassurance from the therapist. In contrast, the narcissistic patient, viewing therapy as a potential humiliation, may devalue the therapist and provoke her in order to test his “power.” These role-enactments in therapy also reflect the social relational systems described by Gilbert (1989, 2000, 2005b; Chapter 6, this volume) as well as the interpersonal schemas elaborated by Safran and his colleagues (Muran & Safran, 1998; Safran, 1998; Safran & Greenberg, 1988, 1989, 1991; Safran & Muran, 1993) and the relational schemas identified by Baldwin & Dandeneau (2005). I have listed some of the common personality schemas in the transference in Table 11.1.

These schemas can be seen as dimensions that are not mutually exclusive, and different therapists may “pull on” them in different ways. For example, one therapist may stimulate hostility or (say) dependency easily in patients in a way another therapist may not. One therapist may find a particular patient very hard to work with while another therapist may not. One reason for this is that the therapeutic relationship is a co-construction and therefore the therapist’s schemas are also key to the co-constructions. Therapists will also have various degrees of these schema vulnerabilities.

Table 11.1 Patient personal schemas in therapy

Emotional schemas and experiential avoidance

Although schematic processing models have largely been focused on personal and interpersonal content, Beck and his colleagues have proposed that schemas are formed for a variety of functions, including physical, emotional, and interpersonal content (Beck et al., 2003). In the cognitive model of psychopathology emotions are implicitly and explicitly identified as important, including emotions as a consequence of cognitive content (“I am helpless” sad), as necessary in the activation of fear schemas for exposure to be effective, and as important for priming in activating latent schematic content (Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985; Foa & Kozak, 1986; Ingram, Miranda, & Segal, 1997; Miranda, Gross, Persons, & Hahn, 1998; Riskind, 1989). Emotions are, of course, the primary reason that people seek out help, but individuals differ as to their conceptualization and strategies that are employed when painful or unpleasant emotions are activated.

In recent years there has been increasing emphasis on experiential avoidance as an important transdiagnostic component in a variety of disorders (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004; Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006; Roemer & Orsillo, 2002). If unpleasant experiences are avoided, however, then opportunities for habituation, extinction, and disconfirmation are decreased. Thus, the individual who avoids social interactions where he might feel anxious cannot experience a decrease in anxiety (habituation) with repeated exposure, which would lead to extinction of escape behavior and disconfirmation of the belief that “I can’t stand to be uncomfortable in social situations” or “I will get rejected if I stay longer” (Foa & Kozak, 1986). Moreover, experiential and emotional avoidance maintains dysfunctional beliefs about emotions, such as “painful emotions will overwhelm me or last indefinitely” (Leahy, 2004b). Experiential (or emotional) avoidance has been implicated in a variety of problems, including generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and depression (Hayes et al., 2006). The question here is to what extent the therapeutic relationship facilitates more experiential avoidance. I suggest that the patient’s own conceptualization of emotions and the therapist’s parallel conceptions will either hinder or facilitate emotional processing.

Greenberg’s emotion-focused model proposes that emotions contain the content of other schemas and that individuals may often activate one emotion to hide another emotion (see Greenberg, Chapter 3, this volume; Greenberg & Paivio, 1997; Greenberg & Safran, 1987). Greenberg refers to these as “emotional schemas” – that is, the schemas that are contained within the emotion. My model of emotional schemas draws upon Greenberg’s work, but in my model I propose that the individual has a “schema” about emotion. I have proposed that individuals differ in their conceptualization and strategies for unpleasant or painful affect (Leahy, 2002). In our work we have identified 14 dimensions. These include the view that one’s emotions are unacceptable and cannot be expressed or validated, that they will last a long time, are out of control, are shameful, don’t make sense, are similar to the emotions of others; experiences of numbness, rumination, blaming, and intolerance for conflicting feelings; the demand that one should always be rational or that emotions point to higher values. We have found that patients with negative emotional schemas are more likely to be depressed, anxious, worried, more risk-averse in general, and more likely to score higher on dependent, avoidant, or borderline personality disorder (Leahy, 2002, 2005a, 2005b; Leahy & Napolitano, 2005). In contrast to the negative schemas of internalizing disorders, we have found that individuals scoring higher for narcissistic or histrionic personality disorder on the Millon Multiaxial Inventory have more positive views of their emotions (Leahy & Napolitano, 2005). Thus, emotional schemas appear to be a core factor in a range of psychological disorders.

Gottman and his colleagues have pointed out that individuals also differ as to their underlying philosophies about responding to others’ painful emotions (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1996). Some people may view the painful feelings of others as an opportunity to get closer and to matter more, while other people view painful feelings in others as a waste of time, as dangerous or as risking activating negative and unwanted feelings in the self. Gottman’s emotional philosophies are often reflected in the emotional schemas that the patient may endorse (“My emotions are boring to others” or “My emotions are disgusting”) and the emotional philosophies of some therapists (“Emotions get in the way of getting our work done” or “The patient’s intense emotions will overwhelm me”). We may view these emotional schemas and philosophies as constituting a set of rules that are often rigidly followed, regardless of the immediate outcome.

Psychopathology as rule-governed behavior

A significant contribution of the cognitive model of psychopathology is that it demystifies the nature of psychopathology. For example, one can write a “rule” that describes the regularity of schematic information processing: “Look for examples that I am helpless” (confirmation bias) or “Discount evidence that I am competent.” Similarly, one can view automatic thought distortions as rule-governed: “Use my emotions as evidence that something is true” (emotional reasoning) or “Take one example of a negative and treat it as if it represents who I really am” (labeling). To say that these are rules does not imply that one is consciously aware of the rule, much less aware that one is “following” the rule. But rule-governed behavior and thought has a long history in psychology, most notably in the field of linguistics (Chomsky, 1969; Pinker, 2002). Indeed, the idea that “rules” govern behavior has found a place in neo-Skinnerian models, such as that advanced by Hayes et al. (2006).

Let us assume that a visitor from another planet – let us say, Mars – has descended into our book-lined study. This non-gender specific individual does not know our human ways of neurosis and character-pathology, but being the good psychologists that we claim to be, we will assist him. The Martian (hereinafter arbitrarily assigned the gender, “male” and the name, Martin) asks, “How can I learn to be a neurotic human?”

To entertain our own fantasy and new theory about personality disorders, we have devised a rulebook for him. The specific personality disorder that we will give him is “avoidant personality” (AP). Having looked up the requisite requirements, we note that to qualify as AP one must have low self-esteem, be sensitive to rejection, and look for guarantees before entering a relationship. What rules will help Martin accomplish this promising role?

- Assume that these rules will protect you from devastating and surprising losses.

- Assume that you are inferior to all humans.

- Assume that other people are judgmental and rejecting.

- Look for any signs of rejection from other people.

- Don’t disclose anything personal about yourself until you have a guarantee that you are unconditionally accepted.

- Rehearse in your mind different ways that you can be rejected and humiliated.

- Treat these rehearsals as if they are perfect predictions of what could really happen.

- Avoid any uncomfortable emotions.

- If you are uncomfortable in any situation, quickly leave.

- Whenever you can, escape into fantasy that is safer and more comfortable for you.

- Conclude that if you experience any criticism or discomfort it’s because you haven’t been observant in following these rules.

Now, should Martin prove to be a good student of character pathology, he will quickly adopt the role of being an avoidant personality. Assuming that he is skilled enough to obtain a physical disguise that makes him “look human,” he might be able to “pass” in interactions, while still harboring his low self-esteem thoughts of being an inadequate and inferior Martian – that is, literally “fooling” humankind with his act. Indeed, Martin may never get rejected by well-meaning humans, but he will harbor the belief that the only thing that has protected him is his strategy of avoidance and hypervigilance. If Martin is a patient in cognitive-behavioral therapy, and he follows his avoidant personality rules, then it is likely that he will encounter a therapist with another set of rules – which may be in conflict with his rulebook.

Personality disorders as self-fulfilling prophecies

I have suggested that personality disorders may be characterized as rulebooks for dealing with other people and for experiencing the self (e.g., self-awareness, emotional schemas). I now propose that individuals who follow a rulebook elicit behavior in other people that confirms the validity of the rulebook. For example, the avoidant personality appears to other people as inhibited, shy, aloof, and often unemotional. This style is likely to elicit caution, aloofness, and tentativeness in other people – which, in turn, will suggest to the avoidant personality that other people are “holding back something” – perhaps their criticism. Indeed, this may actually be the case, since avoidant personalities are often perceived as unfriendly and, at times, conceited. If the avoidant individual is not “rejected,” then he can conclude that his rules are working. If he is rejected, he then concludes that he should be more cautious and hypervigilant.

Similarly, the narcissistic individual follows rules of advertising his grandiosity, devaluing others, and expecting special treatment. He fears devaluation and does not trust others – “I will devalue you before you devalue me.” I have noted that therapists, when discussing their narcissistic patients, both fear them and devalue them – “He thinks he’s superior – that the rules don’t apply to him.” Or, “He thinks he is up there but really he is a turkey.” Note how the therapist can get pulled into thinking in rank terms of one up and one down and competing for position/dominance. It is quite common for therapists to indicate to me, “I would never want to have someone like that in my life.“ Let’s assume that the narcissist is aware of how others experience him – that is, that others want to distance and devalue him or try to outrank and overpower him if he does not grab top position. Perhaps, from his perspective, it makes sense to exploit people who may be viewed as exploiting the self. Thus, the narcissist may have “good reasons” for distancing and devaluing – although he does not recognize that it is his strategy of dominating, devaluing, and overvaluing himself that leads others to fulfill his predictions.

Using this game metaphor of self-fulfilling prophecies, we might conclude that individuals with personality disorders seldom understand how they elicit the very behavior in other people that supports their personality disorder. Taking this one step further, we can look at the therapeutic relationship as two individuals following their own rulebooks (determined by their personality styles or disorders), without awareness that their own style may elicit behavior in the other person. By analyzing the schematic mismatches that may ensue from this, we can determine how problems may arise or be averted in the therapeutic relationship. We turn now to examining how this may occur in the counter-transference.

A social-cognitive model of counter-transference

Although therapists would ideally like to believe that they can work effectively with a wide range of people, clinical experience suggests that each of us has our own difficulties with specific groups of patients. The therapist is similar to the patient in holding certain personal and interpersonal schemas. I have listed a number of these in Table 11.2.

The therapist can ask herself, “What issues concern me most? Which patients are most troubling to me? Are there certain patients I feel too comfortable with? How do I feel about telling patients things that might disturb them?“ For example, some therapists are more concerned about the nature of the relationship, others are concerned about the expression of emotion, and others about encouraging the patient to become more active. While some therapists are intimidated by narcissistic patients, others prefer patients who are self-effacing, while other therapists have difficulty with intense emotional experiences. The therapist can note which patients and issues “push his buttons,” and what automatic thoughts and personal schemas are activated: “If the patient is disappointed in me it must be because I am an inadequate therapist.”

Table 11.2 Therapist schemas in the therapeutic relationship

Problems in the relationship can arise when “things are going well.” Feeling especially “comfortable” with a patient may make it difficult to identify and address problematic behavior such as alcohol abuse, lack of financial responsibility, or self-defeating patterns. Some therapists are reluctant to confront a patient with “disturbing” information, fearing that the patient may get angry, become sad, or leave therapy. This threat of the termination of therapy may activate the therapist’s schemas about abandonment, loss of reputation, or being controlled by the patient.These perceptions of relationship are reflected in the counter-transference schemas held by the therapist. These include demanding standards, fears of abandonment, need for approval, viewing the self as rescuer, or self-sacrifice (see Table 11.2).

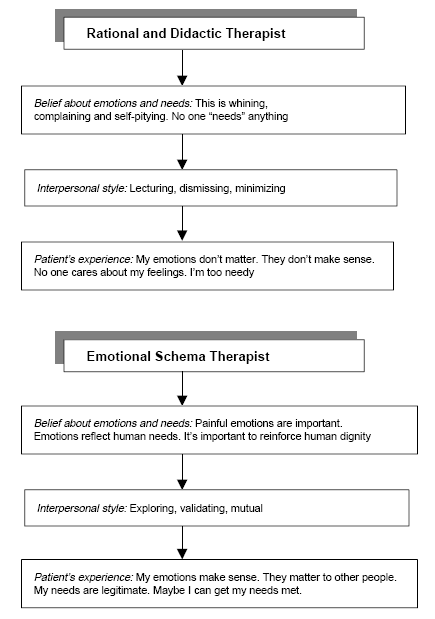

In addition, therapists have different emotional philosophies, reflecting their belief that painful and difficult emotions either can provide an opportunity to deepen the relationship or should be eliminated or avoided. As noted earlier, Gottman’s model of emotional philosophies provides a valuable taxonomy for identifying the shared emotional philosophy within the therapeutic relationship (see Gottman et al., 1996; Katz et al., 1996) – including dismissive, critical, overwhelmed, and facilitative. Of particular interest is the “emotional coaching” style that reflects the therapist’s authentic and non-judgmental interest in all emotions, while encouraging the patient to differentiate and explore these emotions, and to consider ways in which self-soothing can be facilitated. This style is similar to the empathic and supportive style advocated by Rogers (1965), Greenberg (2002; Chapter 3, this volume) and by Gilbert in his discussion of compassion as a complex set of abilities that can help the therapeutic relationship (Gilbert, 2005a; Chapter 6, this volume). Some therapists, who view painful emotions as distracting or self-indulgent, may communicate a dismissive attitude (“We need to get back to the agenda“) or they may take a critical approach, such as that reflected in Ellis’s sarcastic comments about patients who whine (Ellis, 1994). Sometimes patients need to “be with” their feelings, to become familiar with them and learn to tolerate them. However, therapists who are uncomfortable “being with” feeling may constantly ask the patient about his/her thoughts or intrude and inadvertently model emotional avoidance. In psychodynamic approaches the idea is that the patient feels their emotions “can be contained;” that they do not threaten the therapist or the therapy. In this way the patient learns that their emotions are understandable, acceptable, tolerable, and meaningful – but also can change.

The therapist’s emotional philosophy – and the strategies that are implemented – will have a significant impact on the patient’s own emotional schemas (Leahy, 2005b). For example, the therapist who takes the dismissive approach (“Let’s get back to the agenda”) conveys the unsympathetic message that “Your emotions are not interesting to me,” “Emotions are a waste of time,” and “You are indulging yourself.” As a consequence of a dismissive or critical stand by the therapist, the patient may conclude, “My emotions don’t make sense,” “No one cares about them,” “I should feel ashamed or guilty for having these feelings,” and “Focusing on my emotions won’t help me.” As the patient dutifully follows the lead of the agenda-setting therapist, emotions become secondary to compliance with an agenda that may never really address the very reason the patient sought out help – that is, help with his feelings.

Crucially, interpersonal styles differ among therapists – some are distancing, are overly attached, engage in rigid boundary-setting, appear deferent, are dominating, soothing, or reassuring. Therapists who view emotions as a waste of time may appear somewhat distancing (aloof and condescending), deferential (intellectualized), boundary-setting (“That’s not on our agenda” or “We don’t have time for that today”), or dominating (“This is cognitive therapy and we try to focus only on your thoughts and on getting things done“). Other therapists – also viewing painful emotions as intolerable – may be quick to rescue the patient from his feelings (“Oh, you’ll be OK – don’t worry – it will work out”), may directly tell the patient to stop crying (“Don’t cry. Things will be OK”), or may be quick to soothe (“You’ll be fine in a while”). The implicit message from these wellmeaning interactions is that “Your painful emotions need to be eliminated (as soon as possible).” Thus, rather than share, differentiate, explore, and clarify these emotional experiences (as one would do with emotional coaching or in emotional-focused therapy), the therapist may communicate through rescue and support that painful emotions do not have a place in this relationship and that the patient is too vulnerable to deal with his own emotions. Rescuing someone from painful emotions confirms the belief that experiential avoidance is a desirable coping strategy.

Patient-therapist schema mismatch

Games and self-fulfilling prophecies

Game models have been used extensively in biology, economics, military strategy, negotiation theory, and evolutionary theory (Axelrod & Dion, 1988; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Dugatkin & Wilson, 1991; Maynard-Smith, 1982). Games may be single-player (such as a lottery) or may be two-person games that are competitive or cooperative. Here I will outline some aspects of a two-person game that will be applied to personality, transference, and counter-transference. The assumption guiding this discussion is that personality disorders are “interpersonal games” that are self-fulfilling prophecies and strategies that may play themselves out in the therapeutic relationship.

Games are systemic – they will continue until the final move is made. Each participant seeks a “payoff” (von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1944) – which, for individuals with personality disorders, might include escape from negative evaluation (avoidant personality), protective support from a strong individual (dependent personality), or tribute and recognition that one is a superior person (narcissistic personality). Since games are self-contained or systemic – people get stuck within the game – participants may be unable to take the perspective of the game as one of many alternatives (von Bertalanffy, 1976). Thus, the avoidant personality is “stuck” within his rulebook of hesitation, avoidance, and vigilance, leading to a confirmation bias that he is “defective” and others will judge him. The therapist with demanding standards is stuck within the game of compelling others to conform to his agenda.

Games involve reciprocal causation – that is, game-players evaluate feedback and the “moves” made by others. Two-person games – such as that reflected in the therapeutic relationship – involve iterative moves such that a move by the patient leads to a counter-move by the therapist that then elicits another move by the patient. Theoretically, game-players can anticipate the counter-moves by opponents and adapt their strategies accordingly, as a good chess player might do. However, in real interaction we generally attribute our own behavior to the situation and the other person’s behavior to their personality traits. Thus, you may attribute your annoyance with me to the “fact” that I am “boring” rather than to the possibility that you are intolerant of other people. It is the other person who has the trait, while we view our own behavior as determined by the situation (Jones & Nisbett, 1972). Moreover, our explanations tend to be based on the recent prior event, such that we explain our current behavior by what just occurred previously.

Patients (and therapists) with negative schemas may view the therapeutic relationship as a “competitive game” – that is, a zero-sum game in which one side loses and the other side wins. This is in contrast to the “ideal” therapeutic relationship where both sides “get what they want” – that is, a facilitative relationship leading to a rapid improvement for the patient. Pessimistic patients may be more focused on avoiding further loss, and may employ hypervigilant strategies to look for rejection, judgment, or lack of interest in the therapist. These patients will “stop-out” quickly, viewing the small loss (frustration) as the beginning of a cascade of other losses. Patients from this perspective cut their losses early, in a manner that seems “rational.“ This “minimax” strategy – minimizing maximum losses – is also based on the view that losses are suffered more than gains are enjoyed. Indeed, from the patient’s perspective, gains seem unlikely, transient, and are not really “enjoyed” that much. Moreover, the pessimistic view of the patient may suggest that a “gain” (increase of feeling good or feeling close to the therapist) may be a false signal and may tempt the patient to take further risks of exposure. As things begin “feeling better” the cautious patient may think, “This is an aberration. The axe will fall soon. Better to get out now” (Allen & Badcock, 2003; Leahy, 1997).

If the patient’s negative schemas about relationships suggest that he will be abandoned or rejected by the therapist, then the patient may consider himself to be in a “prisoner’s dilemma.” Thus, from the pessimistic patient’s perspective, if he anticipates rejection from the therapist if he does not meet the therapist’s “expectations,” then it “makes sense” from a game model to quit earlier than later. From game theory the patient believes that the therapist will “defect” (that is, give up the supportive role and reject the patient). Research on prisoner’s dilemma shows a general tendency to defect early if the “prisoner” (patient) anticipates that the other side sees a benefit in defecting (rejecting him). Moreover, individuals who view a relationship as competitive are more likely to withhold information that reduces the possibility of any cooperation (Steinel & De Dreu, 2004). Thus, patients with negative schemas – who anticipate negative schemas in the therapist – will terminate early.

Lack of recursive and systemic role-taking

Why aren’t patients and therapists “smarter“? Why is it so difficult to be “objective” about the therapeutic relationship? The reason for myopia and egocentrism is that we may be inclined toward snap-shot views through our schemas, rather than a moving picture extended across time (an “evolutionary or unfolding model” of the relationship developing over time). Real interactions between people in a relationship involve “iterative moves” such that I repeat moves in response to a sequence of moves on your part. Thus, real relationships operate in real time. In order for me to figure out what to do in response to your recent move, I might also want to figure out how you will respond to my next move – that is, will you see me as having a strategy? If I think that you have guessed my strategy, then I might want to block your move by doing what you think I won’t do. Yet, in order to do this, I must take your perspective of the prior moves, how you see my strategy unfolding, and how you might try to outguess me. Indeed, studies of behavioral economics examining game models find a general limit to anticipating iterations. Our interactions are usually engulfed by one or two moves – it is hard to “play chess” in everyday interactions.

This anticipation of how others might respond to our future moves entails both recursive and systemic role-taking and the elaboration of a theory of mind. Recursive role-taking requires the ability to stand back and view one’s own thinking and emotions (or the thinking and emotions of the other). Systemic role-taking involves the ability to observe the relationship across time, and how each participant affects the other (Selman, 1980; Selman, Beardslee, Schultz, Krupa, & Podorefsky, 1986). Insight within the transference relationship entails the awareness of the other’s behavior, inference of motive, seeing the other as provocation or elicitor, self as object of other’s experience, and self–other role-taking (systemic relationship perspective) within the current interaction, other relationships with similar patterns, and past relationships. As the reader has likely noted, this systemic role-taking – involving anticipation of moves in response to others’ moves – is an ability rarely manifested in everyday interactions. Moreover, our own thinking about how others see events or ourselves is often anchored by our own perspective, as if we believe that others respond more like us than like a stranger (Epley, Keysar, Van Boven, & Gilovich, 2004). Indeed, we often use our own mind (the “self ”) as a best guess as to what the other person is thinking (Nickerson, 1999). Thus, if the patient believes that he is a loser, he will conclude that the therapist can see through his transparent self to the loser underneath. Our views of others’ views are anchored in ourselves.

These evaluative or cognitive constraints have important implications in the transference–counter-transference: (1) patient and therapist both have difficulty seeing the “larger picture;” (2) the other person’s behavior is attributed to unchangeable traits; (3) the other person’s behavior is personalized; (4) since one is “locked” within one’s own rule-book, it is hard to get information that runs counter to one’s expectations; and (5) the roles enacted lead to confirmation bias and self-fulfilling prophecies. Needless to say, the ability to view the relationship (in and out of therapy) is more complicated than simply identifying a “distorted automatic thought.” The game model extends the cognitive model to address a series of feedback interactions that are similar to the interpersonal reality of everyday life.

Patient–therapist mismatch

What happens when the patient’s personality disorder conflicts with the therapist’s schema or core belief? Imagine the following: the patient has an avoidant personality – his goal is to keep people from knowing him so that he cannot get rejected. He is cautious, since he does not want to take any chances of getting rejected or failing. Consequently, he is reluctant to carry out self-help assignments, he seldom has an agenda (since he either does not have direct access to his emotions – as he has avoided emotions – or does not want to “make a stand” in therapy). In contrast to this avoidant personality, consider the possibility that the therapist has demanding standards – expecting patients to conform to his agenda and treatment plans. In this interaction, the therapist has little tolerance for “vague complaints,” “procrastination,” or lack of clear goals.

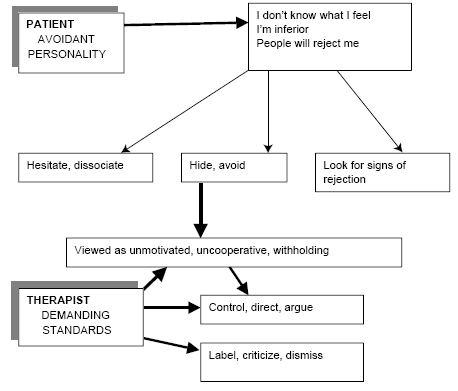

Each participant – patient and therapist – is following a rulebook determined by their schematic dispositions and their personality disorder. The rulebooks are based on attempts by each to “make sense” of the other and to modify the other’s behavior. For example, the patient is trying to find out if the therapist can be trusted, thus, the patient hesitates, remains vague, and waits to see how the therapist reacts. These are passive probes in the patient’s rulebook. Any behavior on the part of the therapist is attributed either to dispositions or traits that the therapist has (“He is critical”) or to defects in the self (“I am a loser”). (The patient does not recognize the situational game-like quality – “When I hesitate some people will either probe or withdraw from me”.) Similarly, the therapist with demanding standards will activate probes, controls, criticisms, and exhortations if the patient is “non-compliant.” The therapist will attribute his own behavior to the patient’s “non-compliance,” not recognizing that this kind of controlling and demanding behavior creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: When the therapist demands, the patient withdraws. This confirms the schematic perception of the patient as non-compliant (see Figure 11.1).

Utilizing the strategic game model outlined above, we can see that the therapeutic relationship is characterized by reciprocal causation. Specifically, therapists will often utilize interpersonal strategies to compensate or avoid the schematic issues raised by the patient. Consider the case of a dependent patient (with fears of abandonment and beliefs about personal helplessness) and a therapist who also is dependent and fears abandonment by patients.

Compensatory or avoidant strategies by therapist

Dependent patient, dependent therapist

- Avoidant strategy

- Therapist does not bring up difficult topics, avoids discussing patient’s dependent behavior, does not set limits on patient

- Therapist avoids using exposure techniques

- Patient’s experience

- My emotions must be overwhelming to other people. Doing new things will be risky and terrifying

- My therapist must think I am incapable of doing things on my own

- I should avoid independent behavior

- Compensatory strategy

- Constantly reassures patient

- Prolongs sessions, apologizes for absence

- Patient’s experience

- I need to rely on others to solve my problems

- I must be incompetent

- I can’t get better on my own

- The only way to get better is to find someone to take care of me and protect me

Or consider the schematic mismatch that arises for the dependent patient whose therapist has demanding standards. This mismatch is outlined below.

- Helpless (dependent) patient

- Seeks reassurance. Does not have an agenda of problems to solve. Frequently complains about “feelings.” Calls frequently between sessions. Wants to prolong sessions. Does not think he can do the homework or believes that homework will not work. Upset when therapist takes vacations

- Demanding standards therapist

- I have to cure all my patients

- I must always meet the highest standards

- My patients should do an excellent job

- We should never waste time

The therapist may adopt either a demanding-coercive or an avoidant strategy.

- Demanding-coercive strategy

- Views patient’s lack of progress as “personal” resistance

- Demands agenda and task compliance

- Critical of lack of progress

- Labels patient as “dependent”

- Patient’s experience

- I can’t count on my therapist

- I will be abandoned if I don’t improve

- My emotions are not important to my therapist

- I am a failure in therapy

- I can’t solve any problems

- Avoidant strategy

- Loses interest in the patient

- Does not explore patient’s need for validation and emotional expression

- Terminates patient for “non-compliance”

- Patient’s experience

- I must be boring

- My therapist has no interest in me

- Therefore, my therapist will leave me

Using the counter-transference

The therapist is not a neutral object onto which internal dynamics are projected. Rather, the therapist is a dynamic part of the patient’s interpersonal world. The therapist with “demanding standards” can recognize his own resistance to the patient in his tendency to impose his agenda onto the patient, coerce him into changing, or withdraw from the patient with indifference. Indeed, if the therapist acts and feels this way, then the patient may be eliciting these responses from other “demanding” people. Three questions can be posed: (1) How does the patient respond when other demanding people interact with him? (2) What are the typical personality characteristics of the people in the patient’s life? and (3) What is the developmental history of relationships and dysfunctional strategies?

I had recognized a number of years ago that I often had “demanding standards” with patients – trying to impose agendas, homework, taskorientation, and techniques. This was motivated by my desire to “get the job done,” but I realized that it was annoying and dismissive for patients. Although I use cognitive therapy techniques and agendas, I place a greater emphasis now on exploring the patient’s emotional schemas, and how others in the patient’s life have responded to these needs. This particular contrast between “demanding standards” and “emotional schemas” presented itself to me with a patient who had previously seen a hard-driving, agenda-setting, “rational” therapist who took a didactic stand.

The patient was a married woman, with long-standing relationship problems, characterized by feeling she was not heard, did not feel emotionally or physically in touch with her husband, and who felt guilty. She responded to the homework “demands” in therapy with statements of her own helplessness and inadequacy, complaining that her problem resided in her controlling and narcissistic husband. In this context, I recognized my own demanding standards coming up again. These would have led me to set strict agendas, “challenge” her automatic thoughts, suggest alternatives, and help lay out some problem-solving strategies. Unfortunately, as I quickly realized, this would replicate the domineering, dismissive, and emotionally empty experiences that she had with other people in her life, from her parents to her husband. I then decided to back away from imposing homework on the patient in order to examine her pattern of deferring to other people in intimate relationships. In fact, her deference to others – based on her view that she did not know her own needs and that she did not have a right to have needs – resulted in others “taking charge” or taking the lead. This reinforced her view that she was secondary in relationships, although she hoped that a strong, determined man “who knew what he wanted” would be able to satisfy her. Just as she deferred in her relationship in therapy, she also deferred in family and intimate relationships.

Prior to seeing me, she had seen an argumentative “rational” therapist who lectured to her. She indicated that this prior therapy reminded her of her father and mother who would tell her how to feel and how to act, but who never appeared to validate her individuality. She experienced the prior therapist as dismissive, critical, and condescending – experiences that she complained of with her husband.

While recognizing the importance of change, we focused on her emotional schemas. I indicated that “the most important thing in our relationship is for both of us to understand and respect your emotions; it’s what you feel that counts the most.” She had difficulty labeling her emotions, often suddenly crying “for no reason” (as she would say). She believed that her emotions made no sense, that no one could understand her emotions, and that she had no right to feel upset since she had a lucrative job and a husband who loved her. She believed that she needed to control her emotions in order to prevent them from “going out of control.” The emotional philosophies of her mother and father were that her emotions were self-indulgent, manipulative, and unwarranted. In fact, she observed that much of her life around her father was focused on trying to “put out” his emotional tirades. There was no room for her emotions in their lives – or in the life of her husband.

Figure 11.2 Therapist schemas.

We decided to view her pain and suffering as a window into her needs and values – that her painful emotions needed to be heard and respected. This new “emotional schema” included the following: “It’s important to recognize a wide range of my emotions,” “My emotions come from human needs for love, closeness, and sensuality,” “I have a human need for validation, warmth, and acceptance,” and “I want to seek this out in a new relationship.” Although she had come for “cognitive therapy” (with an emphasis on “rationality”), she acknowledged that focusing on her rights to have emotions and needs - and to develop relationships where possible – would be worth pursuing.

Let’s review the different therapeutic styles that she experienced. With the demanding and anti-emotional didactic therapist, the “coercive” and “intellectual” style reflected the belief that she was whining, had too many “shoulds,” and had low frustration tolerance. The message was “get over it” and “it shouldn’t matter that much.” The therapist appeared to her to be condescending, out of touch, and critical of her feelings. This confirmed her belief with him that her feelings didn’t make sense, she was self-indulgent, and she had too many needs: “I must be too needy.” In contrast, in taking an emotional schema approach in treatment with me, she was able to recognize and differentiate her various emotions, experiment with expressing emotions and getting validation, explore how her emotions were linked to important needs that were unmet, and recognize that while she was good at supporting and validating others, she would need to direct this nurturant and compassionate mind toward herself.

Conclusions

Cognitive models of psychopathology can be enhanced by incorporating the roles of both emotional processing and social interaction in understanding the therapeutic relationship. I have outlined a model of personality disorders – initially based on the schematic processing model – that stresses several points: (1) Personality disorders follow a rulebook that directs the individual in understanding the self and in interacting with others; (2) Individuals with personality disorders follow confirmation biases in eliciting the very behavior in other people that will confirm their own schemas; (3) Individuals in interaction may have different views of how emotions in others are handled and these differences may reaffirm the underlying schemas of both parties; (4) Participants in the therapeutic relationship are egocentrically biased toward viewing the other’s behavior as due to stable traits, but to viewing one’s own behavior as situational or goal-directed; (5) It is difficult for participants to distance themselves and take a systemic role-taking perspective; and (6) A systemic perspective is possible by identifying the therapist’s and patient’s rulebooks and schemas and examining how the confirmation biases are fulfilled.

Taking this systemic game perspective allows both the therapist and the patient to find regularities in the patient’s past relationships that continue to play out in the current relationship. The therapist and patient can use cognitive, experiential, emotion-focused, emotional schema, and compassionate mind techniques to modify the rulebook that the patient has been using and that maintains his problems even though the patient has come to believe that the rulebook has protected him from worse problems arising.

References

Adler, A. (1924/1964). Social interest: A challenge to mankind. New York: Capricorn Books.

Allen, N.B. & Badcock, P.B.T. (2003). The social risk hypothesis of depressed mood: Evolutionary, psychosocial, and neurobiological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 129(6), 887–913.

Axelrod, R. & Dion, D. (1988). The further evolution of cooperation. Science, 242(4884), 1385–1390.

Baldwin, M.W. & Dandeneau, S.D. (2005). Understanding and modifying the relational schemas underlying insecurity. In M.W. Baldwin (ed.), Interpersonal cognition (pp. 33–61). New York: Guilford.

Beck, A.T., Emery, G. & Greenberg, R.L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books.

Beck, A.T., Freeman, A., Davis, D.D., Pretzer, J., Fleming, B., Arntz, A., Butler, A., Fusco, G., Simon, K., Padesky, C.A., Meyer, J. & Trexler, L. (2003). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders (2nd edition). New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, J.S. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford.

Buss, D.M. & Schmitt, D.P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204–232.

Chomsky, N. (1969). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dugatkin, L.A. & Wilson, D.S. (1991). Rover: A strategy for exploiting cooperators in a patchy environment. American Naturalist, 138, 687–701.

Ellis, A. (1994). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy (2nd edition). Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publishing Company.

Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L. & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 327–339.

Foa, E.B. & Kozak, M.J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 20-35.

Frankl, V.E. (1992). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy (4th edition). Boston: Beacon Press.

Gilbert, P. (1989). Human nature and suffering. Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gilbert, P. (1992). Counseling for depression. London: Sage.

Gilbert, P. (2000). Social mentalities: Internal ‘social’ conflicts and the role of inner warmth and compassion in cognitive therapy. In P. Gilbert & K.G. Bailey (eds), Genes on the couch: Explorations in evolutionary psychotherapy (pp. 118–150). Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (ed.) (2005a). Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2005b). Social mentalities: A biopsychosocial and evolutionary approach to social relationships. In M.W. Baldwin (ed.), Interpersonal cognition (pp. 299-333). New York: Guilford Press.

Gilbert, P. & Irons, C. (2005). Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In P. Gilbert (ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263–325). Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

Gottman, J.M., Katz, L.F. & Hooven, C. (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 243–268.

Greenberg, L.S. (2001). Toward an integrated affective, behavioral, cognitive psychotherapy for the new millennium (Paper presented at meeting of the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration).

Greenberg, L.S. (2002). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenberg, L.S. & Paivio, S. (1997). Working with emotions. New York: Guilford.

Greenberg, L.S. & Safran, J.D. (1987). Emotion in psychotherapy: Affect, cognition, and the process of change. New York: Guilford.

Harvey, A., Watkins, E., Mansell, W. & Shafran, R. (2004). Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hayes, S.C., Luoma, J.B., Bond, F.W., Masuda, A. & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25.

Horney, K. (1945). Our inner conflicts. New York: Norton.

Horney, K. (1950). Neurosis and human growth. New York: Norton.

Ingram, R.E., Miranda, J. & Segal, Z.V. (1997). Cognitive vulnerability to depression. New York: Guilford.

Jones, E.E. & Nisbett, R.E. (1972). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of the behavior. In E.E. Jones, D.E. Kanouse, H.H. Kelley, R.E. Nisbett, S. Valins & B. Weiner (eds), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 79–94). Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

Katz, L.F., Gottman, J.M. & Hooven, C. (1996). Meta-emotion philosophy and family functioning: Reply to Cowan (1996) and Eisenberg (1996). Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 284–291.

Leahy, R.L. (1997). An investment model of depressive resistance. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 11, 3–19.

Leahy, R.L. (2001). Overcoming resistance in cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford.

Leahy, R.L. (2002). A model of emotional schemas. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 9(3), 177–190.

Leahy, R.L. (2003a). Emotional schemas and resistance. In R.L. Leahy (ed.), Roadblocks in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Transforming challenges into opportunities for change (pp. 91–115). New York: Guilford Press.

Leahy, R.L. (ed.) (2003b). Roadblocks in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Transforming challenges into opportunities for change. New York: Guilford Press.

Leahy, R.L. (2004a). Decision making and psychopathology. In R.L. Leahy (ed.), Contemporary cognitive therapy: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 116-138). New York: Guilford Press.

Leahy, R.L. (2004b). Panic, agoraphobia and generalized anxiety. In N. Kazantzis, F.P. Deane, K.R. Ronan & L. L’Abate (eds), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 195-221). New York: Routledge.

Leahy, R.L. (2005a, November 18–21). Meta-cognitive factors of worry and decision-making style. Paper presented at the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Washington, DC.

Leahy, R.L. (2005b). A social cognitive model of validation. In P. Gilbert (ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

Leahy, R.L., Beck, A.T. & Beck, J.S. (2005). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. In S. Strack (ed.), Handbook of Personology and Psychopathology (pp. 442–461). New York: Wiley.

Leahy, R.L. & Napolitano, L. (2005, November 18-21). What are the emotional schema predictors of personality disorders? Paper presented at the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Washington, DC.

McGinn, L.K. & Young, J.E. (1996). Schema-focused therapy. In P.M. Salkovskis (ed.), Frontiers of cognitive therapy (pp. 182–207). New York: Guilford.

Maynard-Smith, J. (1982). Evolution and the theory of games. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Menninger, K.A. & Holzman, P.S. (1973). Theory of psychoanalytic technique (2nd edition). New York: Basic Books.

Miranda, J., Gross, J.J., Persons, J.B. & Hahn, J. (1998). Mood matters: Negative mood induction activates dysfunctional attitudes in women vulnerable to depression. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 22(4), 363–376.

Muran, J.C. & Safran, J.D. (eds) (1998). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance in brief psychotherapy: An introduction. In J.D. Safran & J.C. Muran (eds), The therapeutic alliance in brief psychotherapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Nickerson, R.S. (1999). How we know – and sometimes misjudge – what others know: Imputing one’s knowledge to others. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 737–759.

Nussbaum, M. (2005). Frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Pinker, S. (2002). The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. New York: Viking.

Pretzer, J. & Beck, A.T. (2004). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. In J.J. Magnavita (ed.), Handbook of personality disorders: Theory and practice. New York: Wiley.

Rawls, J. (2001). Justice as fairness: A restatement. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Riskind, J.H. (1989). The mediating mechanisms in mood and memory: A cognitivepriming formulation. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 4, 173-184.

Roemer, L. & Orsillo, S.M. (2002). Expanding our conceptualization of and treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Integrating mindfulness/acceptancebased approaches with existing cognitive-behavioral models. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 9(1), 54–68.

Rogers, C. (1965). Client centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Safran, J.D. (1998). Widening the scope of cognitive therapy: The therapeutic relationship, emotion and the process of change. Northvale, NJ: Aronson.

Safran, J.D. & Greenberg, L.S. (1988). Feeling, thinking, and acting: A cognitive framework for psychotherapy integration. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 2(2), 109–131.

Safran, J.D. & Greenberg, L.S. (1989). The treatment of anxiety and depression: The process of affective change. In P. Kendall & D. Watson (eds), Anxiety and depression: Distinctive and overlapping features. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Safran, J.D. & Greenberg, L.S. (eds) (1991). Emotion, psychotherapy, and change. New York: Guilford.

Safran, J.D. & Muran, J.C. (1993). Emotional and interpersonal considerations in cognitive therapy. In K. Kuehlwein & H. Rosen (eds), Cognitive therapies in action: Evolving innovative practice (pp. 185–212). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Safran, J.D. & Muran, J. (2000). Resolving therapeutic alliance ruptures: Diversity and integration. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 233–243.

Selman, R.L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding. New York: Academic Press.

Selman, R.L., Beardslee, W., Schultz, L., Krupa, M. & Podorefsky, D. (1986). Assessing adolescent interpersonal negotiation strategies: Toward the integration of structural and functional models. Developmental Psychology, 22(4), 450–459.

Steinel, W. & De Dreu, C.K.W. (2004). Motives and strategic misrepresentation in social decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(3), 419–434.

Sullivan, H.S. (1956). Clinical studies in psychiatry. New York: Norton.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1976). General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. New York: George Braziller Publishers.

von Neumann, J. & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Young, J.E., Klosko, J.S. & Weishaar, M. (2003). Schema therapy: A practioner’s guide. New York: Guilford.