4

Rebel Arms Manufacturing and Bomb Making

Every bird upon my word is singing treble—I’m a rebel / Every hen it’s said is laying hand-grenades over there Sir I declare Sir / And every cock in the farmyard stock crows in triumph for the Gael / And it wouldn’t be surprising if there’d be another rising / Said the man from the Daily Mail

—Seán O’Casey, “The Man from the Daily Mail,” 1918 Four

Like each of their rivals, the Irish Volunteers experienced significant difficulty obtaining explosives and explosive devices of all types, especially effective hand grenades. Since British soldiers did not usually carry grenades in the early part of the war, stealing them was more difficult. To address this deficiency, the Volunteers established munitions factories and workshops throughout Ireland. Subsequently, most IRA manufacturing focused on bomb making, so that will be the primary focus of this chapter, with associated and other activities added as appropriate. Rebel manufacturing followed an unrecognized and general pattern of study and research, design, testing, production, fielding, and redesign. Similarly, the design of the explosive devices followed a pattern starting with crude devices, then moving to basic manufacturing, then to complex mechanical device development and construction, and they finished with mature (redesigned) complex mechanical-device development and production. This chapter explores the explosives and the devices the Volunteers developed, along with the organization that made them and provided the raw materials. Part of this includes examining the fabrication processes.

Pre-1917 Manufacture

Arms manufacturing was nothing new to the republicans. The United Irishmen in the 1790s manufactured pikes, and the IRB and Clan na Gael operatives during the two phases of the Dynamite Campaigns made explosives and components for their bombs. Indeed, Thomas Gallagher established a bomb-making school in New York to select personnel for his operation as well as to train revolutionaries in general.1

For the Irish Volunteers, fabrication began in 1915 after the IRB Military Council’s decision to conduct the Rising the following year, as mentioned in chapter 2. The rebels’ manufacturing methods were initially unsophisticated, but these were necessary first steps as their processes matured. At various locations around the country, they made several categories of armaments including bullets and buckshot, pikes and bayonets, and unsophisticated explosives and bombs.

Perhaps the easiest items to produce were bullets and buckshot, which they loaded into cartridges. The Volunteers made them by pouring molten lead into molds to make the bullets or shot. Headquarters gave them plaster shot molds, but these did not work, so Volunteers improvised their own. Once the bullets and shot cooled, the workers painstakingly filled the shells with primer and powder and then inserting the bullets or shot.2 These tasks were not difficult or particularly dangerous, just time consuming.

Another class of weapons easily made was bladed, such as pikes and bayonets. While the former type was entirely outdated for almost two centuries, the latter were current at the time. Ideally, one wanted a bayonet manufactured for one’s rifle, but failing that the Volunteers had alternatives available. In some instances, they modified a bayonet to fit a different type of gun.3 It is unclear how often they did this, but another common practice was to fix bayonets to shotguns by placing a bayonet lug and a simple band of metal bolted around the barrel. A problem with this was that these shotguns usually fired buckshot, which could strike the blade as it spread. The other method was to weld shears or hedge clippers, directly to the guns.4 None of the sources mentioned how useful these were or how often they were used in combat.

From these simple items, they moved to bombs. The explosives and bombs made for the Rising were crude by any standard. The most common explosives available at the time were gunpowder and nitroglycerine. Frequently, the Volunteers simply made black powder, which sufficed for shotgun ammunition but not for primers or bombs. The latter two needed high explosives, and this meant using the only commonly available source, commercial nitric-based explosives. Fortunately for the Volunteers, they had many members working in mining, quarrying, and construction with ready access to these explosives.

The first primitive bombs from the Irish Volunteers in 1915 and 1916, and even after the Rising, according to John O’Mahoney, quartermaster of Kilmurray Company, Macroom Battalion, Cork First Brigade, came almost exclusively in the form of canister bombs, which were later called “billy-can bombs” (see below). Their earlier canister bombs used black powder and buckshot.5 Both types were heavy, awkward, hard to throw, difficult to ignite, and, since they required an open flame, were often more dangerous to the Volunteers than to their enemies. For these reasons, most rebels that made them recalled never using them for combat operations.6 This unreliable bomb was never going to be adequate.

The early Irish Volunteers established several assembly locations in Ireland, but they were centered mostly around Dublin. Probably the most famous of these was at Larkfield Mill, Kimmage, a property of Joseph M. Plunkett’s family. Another was at Pearse’s St. Enda’s School in Rathfarnham. There were still others at Liberty Hall and at Clontarf.7 Volunteer Frank Daly established one in late 1915 after a fellow IRB man called John Cassidy approached him and asked Daly to work for him at Dolphin’s Barn Brick Works to learn more about explosives than was possible with his work on the Roundwood reservoir. Shortly thereafter, most likely at the behest of Sean MacDermott, Daly began to make bombs. Daly rented rooms from John Malcolm Gillies, a Scottish Presbyterian, at a residence named “Cluny,” in Clontarf. There, hiding mostly in plain sight, Daly and his men worked full time to produce bombs.8

At these types of locations around the country, they made two kinds of hand-thrown bombs: flame ignition and contact-fused. They made billy-can bombs by placing a pole into one of the tin cans, pouring in small metal discs, filling it with molten lead, and then removing the pole after cooling. The bomb makers placed a stick of gelignite or dynamite in the hole, inserted a fuse, and finally wrapped the whole assemblage in paper. The other method was to put more weight on top and using an empty rifle or pistol cartridge with only a primer in it as a detonator. The mass was to ensure that the bomb landed on the detonator.9 The improvised devices were crude but could have been quite useful under certain circumstances. These places were not true factories: they did not produce but merely assembled preexisting parts. True manufacture only came after the Rising.

Irish Volunteers’ Explosives

As mentioned in the previous chapter, the GHQ officer ultimately responsible for most aspects of Irish Volunteer explosives was the quartermaster general, but this was true only in an organizational sense. Within the QMG Department were directorates responsible for various elements of the supply field. Of those, two, Chemicals and Munitions, were directly involved in explosives acquisition, manufacture, construction, development, employment, training, planning, and so forth. A third, Purchases, was also heavily involved in explosives procurement, but its roles in this, since it usually operated overseas, will be examined in chapter 5.

The most glaring need for the Volunteers in the early part of the war, around 1918 and 1919, except for weapons or ammunition, was their lack of explosive compounds. While the rebels used gunpowder and gelignite in 1916, their explosive devices were weak. Thus, the Chemicals and Purchases Directorates came into play. The former was responsible for making and developing better explosive compounds, while the latter obtained new stocks of “factory-made,” usually commercial-grade vice military-grade, explosives. Both directorates turned the resulting explosives over to the Munitions Directorate, whose job was to “weaponize” the substances (see below).

The relationships between the directorates were fluid and frequently based on the personalities involved. While Collins maintained control over as much of GHQ as he could, he did not command the IRA or have final authority over the selection of the men who filled these positions. Therefore, there were people in GHQ not entirely under Collins’s thumb. That said, Collins was involved in many aspects of supply. The first and probably most apparent of the QMG staff directors involved with explosives was the director of chemicals.

The Directorate of Chemicals

Unlike most QMG positions throughout the War for Independence, there was only one director of chemicals, James Laurence O’Donovan. Remaining in one position was unusual. By all accounts, O’Donovan was capable with explosives; indeed, GHQ created the job for him, and he remained in it until the end of the war and beyond.10

While O’Donovan became infamous in the IRA campaigns against Britain and Northern Ireland in the 1930s and 1940s, his earlier IRA involvement focused more on development. In 1917, he was a chemistry graduate student at University College, Dublin (UCD), when Richard Mulcahy recruited him to work on explosives. Mulcahy met him through a mutual friendship with the family of Professor Hugh Ryan.

Although he failed his first-year science examinations at UCD and tried to join the Royal Navy in 1914 and 1915, O’Donovan’s exposure to Ryan, a staunch republican, and others eventually brought him into the republican camp.11 His earlier poor academic performance notwithstanding, he completed his honors degree in 1917 and worked for the Nobel Explosives Company while beginning his postgraduate studies at UCD. His primary mentors were Ryan and Professor Thomas P. Dillon.12

O’Donovan was perfect for this line of work: he was young, by all accounts brilliant, and unknown to the authorities. He said his brother was quite active and known to the police, but James was “considered the only respectable member” of his family and that he “was perfectly safe everywhere” until 1920. On Mulcahy’s direction, he worked directly for GHQ surreptitiously.13

O’Donovan’s mission was simple: develop high explosives.14 The most commonly available explosive was gelignite, a commercial-grade, nitric-based, high-explosive compound used primarily in mining, quarrying, and construction throughout Britain and Ireland. However, it was not powerful enough for combat operations. To achieve the desired results, they frequently had to use considerably higher amounts than could fit in a reasonably sized bomb case or mine. Moreover, there were other problems with gelignite: it required special handling and storage and was prone to freezing. Once frozen, it would not detonate and, upon thawing, it became dangerously unstable; thus, it was unsuited to the climatic conditions in Ireland in winter. O’Donovan worked for Dillon at UCD starting in January 1918. Their task was to develop an explosive compound that Volunteers could produce from materials found in Ireland.15 O’Donovan later blamed Dillon for leading their experiments down the wrong path; fortunately for him, their partnership did not last long.

In some ways, Dillon’s arrest during the frenzy surrounding the German Plot in March 1918 freed O’Donovan to explore other possibilities. Soon after that, O’Donovan began work on poison and lacrimatory gases.16 He believed this indicated the Irish Volunteers were going to use them against the British, but after going to work for Dr. William D. O’Kelly, instructor of pathology at UCD and assistant pathologist at Mater Misericordiae Hospital, Phibsboro, O’Donovan found out that far from learning to use the odious weapons, their mission was to develop a gas mask as a countermeasure.17

The Munitions Directorate

The second GHQ directorate involved in bomb making was Munitions. During the war, there were three directors of munitions: Michael Lynch, Peadar Clancy, and Sean Russell. Their duties were the manufacture of bombs, mines, grenades, and ammunition.18 Therefore, when O’Donovan concocted supplies of his explosives, he sent them to the Munitions Directorate, which loaded them. The bombs and grenades then went to the QMG, which sent them to the brigades or stored them until needed. Munitions also provided explosives to the Engineering Office, primarily for testing and development. It might seem that their processes were overly complicated in such an organization, but when one considers the complexity of what the rebels were doing, one would not want amateurs constructing bombs or mixing volatile chemicals into explosives. Moreover, the members of these directorates worked well together across organizational lines.

Manufacturing Explosive Devices

As mentioned already, explosives were important for breaching actions during barracks attacks, and their importance only increased as the RIC began to fortify its remaining barracks in 1920. Bombs were also useful in demolishing road and railway bridges. These uses eventually gave way to mines, both antivehicle and antipersonnel, which, after January 1921, became increasingly more critical to IRA ambushes of armored and dismounted groups. The problem, as always, was supply.

O’Donovan’s remit was primarily to produce a new high-explosive compound. He called his first concoction “War-Flour,” which he made with “nitrated resin” treated with nitric acid. Although sufficiently powerful and durable, it was difficult to make. If one did not remove all the nitric acid in the final step of the process, the mixture became unstable and, according to O’Donovan, “a bit dangerous.”19 These compounds caused some fatal accidents.

While working in the basement of the Peter Street Dispensary in late 1920, O’Donovan, and his assistants, Jim Cotter and John Tallon, tried other mixtures that would be easier and safer to produce. They tried several types of explosives;20 however, these were unsatisfactory due to complexity in production or their final properties. He based his next researches into cheddite and named his new derivative mixture “Irish cheddar.”21 It was powerful, simple to make from readily available materials, safe to handle, and easy to use.22 O’Donovan’s achievement was impressive, but until the process was known to the brigade chemists, the Irish Volunteers still had to use gelignite, if for no other reason than its seeming ubiquity among available explosives.

While O’Donovan concocted new explosives for the Volunteers, the Munitions Directorate received and dispersed them. As mentioned above, Munitions and the Engineering Office worked closely with the Chemicals Directorate to design, develop, manufacture, and assemble new explosive devices. These came in three varieties based on function: mines, bombs, and grenades.

Mines and Bombs

The Irish Volunteers rarely defined terms or doctrine, so much of their action was based on regular practice. Based on these, the rebels used mines to attack specific targets and included two varieties; antipersonnel and antivehicle. They usually placed these in the ground and either pressure or electric command detonated them.23 This required the Volunteers to observe and learn the usual patterns of army and police movement—their timing, route, and complement. The Irish Volunteers did not usually bury mines in the winter for long due to the risk of freezing and either failing or becoming unstable. The other, more humanitarian reason was they did not want to harm the wrong people.

Based on usage during the war, IRA bombs came in three varieties: breaching, demolition, and general-purpose. A breaching charge was meant to open a hole in a structure—usually a door or a wall—to allow entrance of an assault force. The weapon’s size might vary depending on the target. The demolition charge was similar, although frequently larger and used against structures such as buildings or bridges, or even trees, with the intent of bringing them down. When used in countermobility operations,24 the demolition charge resembled the mine in that its purpose was either to shape the operation or to deny territory. With the former, the effects of these weapons channeled enemy forces onto a specific route more favorable to the rebels, while the latter denied avenues of approach. In any event, the rebels designed the charge with targets in mind. Thus, charges dropping trees across a road were different in size, weight, and explosive yield than one used against a wall or door of a police barracks. General-purpose bombs, designed and constructed in standardized sizes and weights, achieved predictable effects. In these instances, there would be several different sizes premade and available for use against targets.

As should be clear from the above, the distinctions in these devices were frequently more in employment than design, such as when the IRA used a general-purpose bomb as an antipersonnel mine against the Second Hampshire Regiment Band in June 1921.25 It was merely a massive bomb embedded in a wall with the blast overpressure causing most of the casualties rather than the shrapnel. Even the antivehicle mine was mainly just a large device meant to rupture an armored vehicle. Probably the most common of Irish Volunteers explosive devices was the seemingly omnipresent hand grenade.

Grenades

Although the Volunteers needed many different pieces of equipment and weapons, from firearms to knives to blankets to bombs to ammunition, they had an inexplicable, desperate hunger for hand grenades. Grenades could be valuable for their ability to produce disproportionate casualties; one weapon could kill or maim up to a dozen or more. Grenades were not, however, a panacea for the issues the Volunteers faced. Their use in Ireland, by both the rebel and British forces alike, provides a mystery of why there was almost no mention in the extant sources of the use of different types of grenades.

Although available from the start of the Great War in August 1914, the grenade languished because the army had little doctrine for its employment by the infantry. Most of the army grenades in the early part of the war were contact-fused “stick” grenades. This type was a high-explosive tonite charge, wrapped with a metal fragmentation band. The stick helped with throwing, provided in-flight stability, and ensured that it landed tip first. They were “percussion,” or contact fused, meaning once armed, they exploded when something struck the tip. The real problem was that the fusing made the weapon dangerous because the arming safety was not foolproof, and there were frequent accidents. The need for versatility led to the development of other grenades, both of type and design.26

Toward the end of the war, British infantry had matured to having fully integrated specialist squads and platoons with various types of troops. The trench-clearing squads had riflemen, bombers,27 snipers, light machine gunners, and men detailed to use bayonets. The army established bombing schools in each of the home commands to teach the skills needed.28 The bombing schools taught a three-week course where bombers became thoroughly familiar with each of the five types of grenades and the multiple variants of each,29 along with their employment, safe handling, and maintenance.30

Use of Grenades in Ireland

With such considerable experience and doctrine, it is somewhat surprising there was no mention of the various types of grenades in the army’s publications, standing orders, after-action reports, or histories in Ireland. The only different type of grenade mentioned having been used by British forces during the war were rifle grenades used by the RIC, such as those used in an ambush in Tourmakeady, County Mayo, in the midspring of 1921.31 The difference in grenades was only an issue of delivery means, not type. The most common grenade mentioned in the war, the “Mills bomb” or “Mills grenade,”32 which came in both hand-thrown and rifle-fired variants.33 Part of the answer of why the British did not use lacrimatory grenades lay in the abhorrence of gas in the aftermath of World War I that would lead to the first Geneva Convention; the cabinet was unwilling to use gas of any type in Ireland. Thus, it kept even lacrimatory agents under lock and key.34

Irish Volunteers’ Grenades

During the war, the IRA brigades and battalions in towns and cities tended to place their bomb-making facilities in more commercial or industrial areas, probably because of the availability of the necessary services at these sites. They had to be concerned with issues such as the structural integrity of the building, especially the flooring, whether it had gas or electricity, or if water was readily available. Further, traffic in and out could not attract much attention in a shop or warehouse but might in a garage or house. Finally, such areas provided natural cover by allowing the Volunteers to disguise their activities as legitimate businesses. In this way, with the right cover story, they masked the more obvious issues, such as their use of forges and foundries, as at 198 Parnell Street, Dublin.35

The rebel factory locations depended mainly on the locale of the sponsoring unit. Those in urban environs, even if mostly rural, tended to be headquartered around the population centers, and so it was natural for their facilities to be in the major cities and larger towns. While the rural sites rarely had to be concerned with smoke or noise, these were a primary concern for the urban shops. If the rebels in the countryside chose carefully, the sites there were easily securable, since guards could command the approaches. In the cities, this was possible too but considerably more complicated due to the nature of the confined space of the built environment. Unlike the city units, the rural units did not have to travel far to test arms and munitions, but they faced other challenges.

Rural working conditions usually imposed limitations, as the sites were more rustic than the urban. Without electricity or gas, it was difficult for the Volunteers to have machining tools unless they could secure a generator, which, of course, required fuel. If using a foundry, bringing in sufficient coal could also prove challenging, especially without attracting attention. Although coal was in everyday use, residential requirements did not call for the higher grades of coal or coke required for manufacturing purposes; the Volunteers tended to place these shops in homes, farm buildings, and shacks.36

In 1917, the QMG decided to expand its capabilities by making its grenades. While the actual mechanics of assembling a grenade were not difficult, obtaining sufficient components posed a challenge. Regardless of type, all grenades essentially functioned in the same way: the filler ignited, which produced an explosive effect. Each grenade had the same essential components: case, filler or charge, and fuse. Function and the desired effect determined the composition of the elements.37

Although simple in theory, grenades are complicated devices. Grenades must be small enough to throw, sufficiently robust to fulfill their function, completely reliable, safe to handle, and manufacturable in mass quantities. When one does not need to mask the activity, one just establishes a factory, without concern about secrecy. If secrecy is critical, the entire process becomes more difficult because the most mundane action might give it away. Several steps and components went into the design, manufacture, and assembly of these weapons—explosives, casing, fusing, firing mechanisms, the production of each, assembly of the final whole, safe transportation, and safe storage—before the eventual issuance and employment.

A case is the form into which the explosives, the shrapnel, mechanical parts, and fusing go to make the complete package. The case used depended on the effects desired. For fragmentation, the grenade case usually was “a thick cast-iron wall serrated in such a way in the mold as to reduce by fragmentation to a theoretical 48 fragments upon explosion.” The GHQ staff, including Rory O’Connor, O’Donovan, a Jesuit called Dowling who was an engineer, and Daithi O’Brien, also an engineer, designed the grenades they produced with the only limiting factor being the physical capacity of the foundry.38

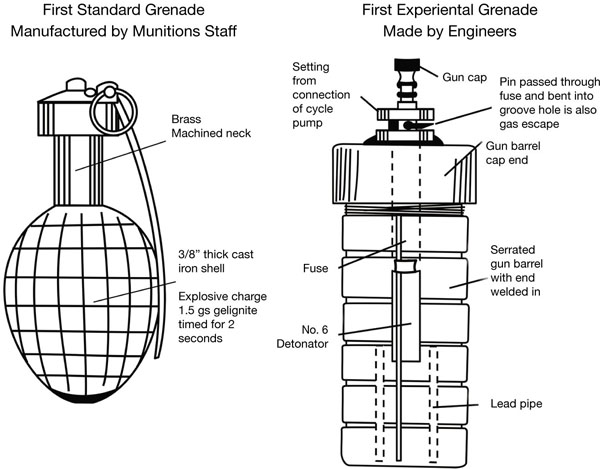

The fragmentation grenades were the first the Volunteers produced and were like the Mills bomb but slightly smaller:

It was serrated cast iron and had no base plug or filter plug, the explosive being loaded through the screwed neck opening which was then closed by the brass fitting carrying the firing set. To avoid corroding the detonator by the nitroglycerine of the gelignite, a piece of glass tubing was set in the middle of the explosive charge to keep the copper case of the detonator out of contact with it, the top of the explosive outside the edge of the glass tube sealed with wax.39

Others described these as being the size of a duck egg with a brass shaft attached, and, indeed, some Volunteers called them “egg bombs.” The quality of the grenades produced impressed O’Donovan, particularly those from the Parnell Street factory. In his witness statement, some forty years later, he still remembered “getting a beautiful grenade turned out in a week—a vast improvement on anything that had been done before in the way of molding the wall with its narrow grooves. I always maintained that our final grenade was superior to the Mills.”40 Perhaps the British agreed. Toward the end of the war, while in British custody, IRB man Joe Lawless, who worked at the grenade factory at 198 Parnell Street, claimed that the British intelligence officer who had been questioning the prisoners complimented him on the quality of the operation there.41

The Fourth Battalion, Dublin Brigade, started its operation to fabricate grenades in early 1918, albeit on a small scale and with the assistance of the QMG. Duplication in manufacturing was a wise practice, as became apparent later in the war when enemy captures took a heavy toll. Due to these security concerns and space limitations, the leaders divided the process between several locations that allowed them to work more quickly and safely. Obtaining all the necessary materials and equipment such as crucibles, molding sand, and cores through the IRA supply systems, the shop produced small numbers of a grenade of the battalion’s design. Each battalion of the brigade eventually had its factory and design.42 One problem these manufacturers had was with setting off their grenades on cue.

Fuses

Probably one of the more difficult aspects at the time in developing the grenade was its fuse. Every fuse had to ignite and then burn at a steady, constant, and consistent rate without setting off the main charge too soon or too late.43 O’Donovan and Dillon devised fuses from the cases of .22 cartridges, which, emptied of their bullet and propellant, had a percussion cap-like primer left over.44 The primer was a mercury fulminate charge designed to set off the propellant. Lawless’s witness statement provided a good description, which is worth quoting in full:

The firing set consisted of a brass casting screwed to fit the neck of the iron bomb case, and bored to carry the striker pin and its spiral spring. The lower end of this bore had the anvil carrying the percussion cap screwed into it, and at the upper end, the firing pin projected in the cocked position, to be held by the trigger handle which automatically released it on throwing.45

The problem with the small .22 was the strength of the ignition smothered the flame. Lynch said an ordinary Volunteer after a brigade council meeting one night told him that vent holes would work. These holes in the side of the case allowed the energy to dissipate while the flame continued to light the fuse.46 This igniter, combined with the fuses, springs, and triggers, formed what they called the “firing set.” O’Donovan again commented on the quality of the weapons the foundry produced, saying that “the length of fuse, its distance into detonator, total length and other measurements [were] accurate to 1/32nd of an inch” and describing it as “workmanlike.”47 That the Volunteers designed, tested, and produced a functioning grenade, without adequate materials, at a time when they had to hide their activities, was impressive.

Irish Volunteer Specialty Grenades

As mentioned above, there were several possibilities with different types of grenades, and the Volunteers experimented with various kinds. They needed better methods of attacking targets, and other types of grenades could meet those needs.

Incendiary grenades

There were many instances of “incendiarism” by the IRA, especially against police barracks, vacated or otherwise. Volunteer GHQ tried to assist in these attacks wherever possible. Two of the more famous incidents in Dublin were the Custom House and the National Shell Factory fires, both in 1921. The usual method was to dowse with kerosene or gasoline and throw a burning torch, but, considering weather and other factors, this did not always work. It also placed the Volunteers involved at considerably higher risk; they had to move forward with the accelerant and the ignition source, while under fire, usually at night. The danger of shooting or burning was high, as happened to Paddy FitzPatrick, who was badly burned attempting to set the Courtown RIC Barracks in County Wexford ablaze during an attack in early 1920.48 GHQ brought O’Donovan in to create incendiary devices.

Volunteers needed a compact device with its ignition system that would both start a fire and keep it going. It needed an “easily consumed” case, which would ideally help produce “intensely high temperatures in the least time.” In one attack on 11 April 1921, the London and North Western Railway Hotel on the North Wall Quay, then used as ADRIC Q Company headquarters and barracks, O’Donovan put a mixture of phosphorous and carbon bisulfide in grenade-sized bottles.49 This attack did not cause a fire but wounded one policeman. The Auxies reported that the IRA had used “gas” in the attack.50

The first incendiary grenade O’Donovan constructed was a thermite grenade with a lead case. He had trouble getting the fuse to work with the thermite while simultaneously producing a “mildly explosive action which had the effect of scattering the main body instead of rapidly igniting it.” The chemicals and munitions directorates eventually solved this problem, and O’Donovan, along with Peadar Clancy, Mick Lynch, Dick McKee, and Sean Russell, successfully tested it in the basement of the old Volunteer headquarters at 44 Parnell Square in 1919.51 It is not entirely clear why the Volunteers did not use these grenades in more significant quantities.

The IRA established at least one factory to manufacture weapons such as these. In April 1921, several men began working in Greenwich, England, making various types of devices, including incendiary grenades. There has been no evidence to emerge why it took almost two years to establish this factory. O’Donovan toured the facility in August 1921, hours before it experienced a catastrophic explosion that killed Volunteer Mick McInerny. It closed shortly afterward.52

Lacrimatory Gas and Other Grenades

A review of the RIC inspector-general (IG) reports reveals most IRA attacks on RIC barracks failed. Of the more than 287 reported rebel attacks from 1918 to 1921, at least seventy were unable to gain any discernable positive result for the attackers. Examination of some of these attacks in depth reveals that most apparent reason for the successful defense of a barracks was the rebels not gaining entry. Other than rushing the door, the other main way of entering was to breach a wall. If the wall was damaged sufficiently to storm the breach, the barracks was likely lost. The best means to create a hole was to use a breaching charge. For vague reasons, the Volunteers had considerable difficulty breaching barracks walls. The barracks were either converted civilian dwellings or purpose-built but not designed to withstand sieges. As such, they were considerably more difficult to fortify and should not have been difficult targets to penetrate. In several instances, the rebels set barracks ablaze, and the RIC surrendered, but in others the police continued to fight until relief forces arrived, as at Carrigadrohid, County Cork, on 9 June 1920.53

Under these circumstances, having exhausted these means, why did the Volunteers not use the apparent mixture of varying types of grenades? Phosphorus or thermite grenades would have caused a fire the police likely could not put out. Considering police did not have gas masks, lacrimatory grenades would have forced them to exit until the force could issue masks. Even smoke grenades would have obscured their vision to prevent capable defense long enough to employ other means. These weapons existed; the doctrine for using them was in the infantry manuals of times, yet there is little evidence of the IRA considering trying to use them.

Part of the answer must lay with the reality that most Irish Volunteers were very poorly trained. One must consider what the effects would have been of handing out multiple grenade types to the average Volunteer. All grenades, as the adage says, “work both ways.” Just tossing one of these grenades without consideration of the surroundings could be disastrous; that was why the British army had a three-week bombing school for handpicked men. Since they frequently used explosives and grenades they made themselves, and these were known to fail, what this additional factor of multiple types would have done either to the already tricky manufacturing process were undoubtedly problematic. Unfortunately, without further evidence, it is impossible to say whether GHQ even considered these factors. Thus, there is insufficient evidence to determine why the rebels did not use these weapons.

Considering the rebels’ continuous and expanding use of all manner of civilian and military explosives, it seems unlikely they had no desire to use these weapons. When one considers that as early as 1917, the IRA was experimenting with mortars and land mines, both of which were less discriminating than the shorter-range effects of grenades, any humanitarian reasons seem unlikely. Furthermore, the Volunteers were perfectly willing to risk using arson in crowded urban settings.54

It may well be the rebels were unable to get more than one type of grenade. This argument seems reasonable considering their difficulty in acquiring other weapons, such as machine guns, trench mortars, and armor-piercing ammunition. Nevertheless, in the admittedly patchy smuggling records, there were many references to grenades but only one to any type other than fragmentation grenades. In April 1921, Padraig O’Daly in Liverpool wrote the QMG to tell about a source in Rotterdam, one Harry Shorte, a messenger working in the arms network who claimed he could get “Gas bombs” of unspecified type. He felt the QMG should move quickly as such grenades “would be particularly valuable.”55 This demonstrates there was at least some discussion and that someone recognized the need. The records say nothing more about whether Shorte obtained gas grenades or, indeed, if the director of purchases, Liam Mellows, ever asked him to do so. It is likely that they did not.

Combined with O’Donovan’s manufacture of lacrimatory gas, these issues bring up the questions of the Irish Volunteers’ military competency and especially that of their leadership. They knew the weapons existed, and they had a clear and discernable need, but they did not use or try to obtain them. This suggests incompetence, yet several considerations counter such an accusation.

The first point is availability. These weapons were not standard and were tightly controlled. If the Volunteers were unable to purchase them, the natural recourse would have been to manufacture them. Considering O’Donovan’s work with Dr. O’Kelly mentioned above, he possessed the technical skill to produce the gases, but there were more problems, capacity being the most important. Leaving aside all consideration for safety around volatile chemicals, one man could not produce sufficient quantities of the gas to be militarily useful. Military utility, in this instance, required the ability to sustain activity. This was the same problem as with Dillon and the gas mixtures mentioned above: insufficient ability to achieve appropriate scale. The next difficulty was with the supply of important chemicals in the necessary quantities. The British regulated the chemicals industries closely, which hampered any attempt to obtain them in sufficient amounts (see chapter 6 for more detail). Therefore, having only one or two functioning weapons and using them operationally would hardly be worth the time, resources, and workforce expended for the result.

The last physical limitation was “weaponization,” which is the process of making a chemical payload deliverable as part of a weapon system. This process must ensure proper delivery of the agent to the target in a condition to maximize its intended effect. In the instance of dispersing or scattering a chemical agent, this usually requires an explosion of sufficient force to spread the agent out from the detonation without the ensuing heat changing its chemical properties beyond those desired. With gases, simple pressure usually suffices, but the timing would also complicate the issue. Considering O’Donovan’s trouble with his thermite grenades, this was an obstacle; thermite does not customarily spread far but burns in place. Given sufficient time and resources, he would have overcome these issues with a gas grenade, but he had neither. Thus, it made sense to focus O’Donovan’s energies in the areas with the greatest payoff, especially when the rebels believed that they needed fragmentation grenades.

Another reason for the rebels not using multiple types of grenades was timing. Early in the war they were poorly armed and equipped, not to mention abysmally trained. By the time they would have been ready to use such devices, probably late 1920 into the spring of 1921, the time for using them had passed. The missions shifted from attacking the tiny garrisons of the RIC barracks to striking at, and with, mobile columns. Due to these issues, it is most likely that they focused their limited resources on making what GHQ thought it needed most.

A final reason against the adoption of these weapons was not physical but moral. If despite the savagery claimed by republicans the British were unwilling to use these weapons, one can only imagine the political repercussions of the republicans doing so. Considering the mistaken, but sensational, headlines about the attack on the London and North Western Railway Hotel and that the Catholic Church in Ireland was already torn about the war, this would likely have tipped the scales against it.56 Thus, the IRA had good political reasons to avoid these weapons. Further, using them might have steeled British resolve and eroded international support. It was a demonstration of competent leadership not to use them because military victory was unlikely. Success would come from political positioning, and Mulcahy, Collins, and some others appear to have understood this.

The earlier issue of effectiveness of homemade weapons leads to other, more important considerations, such as why the IRA did not standardize their explosive devices by introducing a single design for satchel charges and grenades early in the conflict and by using commercial detonators. There were many instances of bombs and grenades failing in battle because they would not ignite. Worse, there were cases of misfires, where the devices went off at the wrong time—including fatal accidents, such as the death of Peter Monaghan at Crossbarry.57 This would have diminished with commercial detonators. Many of the items coming through the Liverpool arms office to Ireland were commercial igniters: basically a match encased in metal ensuring ignition of the fuse to the charge. They were shipped by the hundreds during the war, but they did not commonly show up on the battlefield or ambushes. If one considers that the smugglers were sending these by the gross per week in 1919 and for the entire war, there were thousands of them in Ireland by 1921.58 This was a failing of both the engineering staff and QMGs.

Figure 4.1. Sketches of IRA Grenades and Bombs

Source: Based on sketches from Liam O’Doherty, MAI WS 689.

Irish Volunteers Manufacturing

Designing useful hand grenades for Volunteers was relatively easy compared to the task of producing them in sufficient numbers to be helpful in the field. Complex facilities required a level of organization most Volunteer brigades did not have until relatively late in the war, except in places such as Dublin and Cork. As appears to have been common in this phase of the long struggle for independence, a combination of individual initiative and organizational support paved the way to manufacturing. Once any type of high explosive was available in considerable amounts, the IRA needed a functional grenade case.

To meet this need, the Volunteers established many types of shops and factories: foundries, machine shops, filling sites, assembly shops, ammunition reloading and production facilities, and repair shops. Since these facilities were hidden from the authorities, they frequently performed just one task of an overall process, to limit the damage if captured or due to space available at the location, but sometimes they had several functions collocated. For instance, while the Third Brigade had a foundry at Bailieboro, County Cavan, the Newmarket Battalion, Cork Second Brigade, established a workshop, foundry, repair shop, and machine shop in one location in October 1920.59 While it certainly facilitated production, having facilities like those at Newmarket co-located may have been due more to a matter of necessity than desire. Sufficient secure locations with the appropriate services offered may not have been available. Further, the rebels may not have been able to secure several sites; many shops together were easier to guard. The potential for discovery went up due to increased traffic and made the results of such raids all the more disastrous, as when the police raided the facility hidden in the basement of 198 Parnell Street in November 1920 (see below).

Foundries

The IRA’s foundries were either preexisting businesses or established according to need. In the former, individual Volunteers working there made items surreptitiously during their regular workday and hid them until another Volunteer or sympathizer could retrieve them. For instance, Volunteer Paddy Murray made grenade cases in the Drogheda foundry where he worked, while Willie Neenan did likewise at Merrick & Sons on Parnell Place in Cork. Men working in the Great Southern Railway Works in Inchicore also made grenade cases for the Volunteers and just dropped the finished goods into the burned sand refuse collected by another sympathizing worker daily.60 Sometimes the proprietors, managers, or foremen were republicans and assisted these efforts.

Peter de Loughrey’s commercial foundry had made grenade cases in 1916 for the Rising and, in September 1920, GHQ asked him to begin again. Headquarters also wanted him to get other foundries to work for it, but he failed in the latter mission.61 A widow, Margaret Baker, allowed the IRA to use her foundry and machine shop, Baker Iron Works on Crown Alley, Ballsbridge, Dublin. Although located just across from the heavily guarded central telephone exchange, the site was never discovered.62 Due to the relative dearth of sympathetic foundry hierarchy and the low amounts they could produce in this manner, many battalions and brigades opened their own foundries.

Table 4.1. Some IRA Arms Production Facilities in Dublin

| Address | Front company | Operative years | Primary function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 Aungier St. | Tobacconist shop | — | Assembly shop |

| Crown Alley | Baker Iron Works | Jan.1921 | Foundry & machine shop |

| Denzille Ln. | Unspecified | 1921 | Foundry |

| 17 Dingle Ln. | Unspecified | — | Filling grenades |

| Dominick St. | Tenement | — | Filling grenades |

| Eccles St. | Unspecified | — | Filling grenades |

| Inchicore | Inchicore Railway Works | 1920 | Foundry & machine shop |

| Leonard’s Corner | Unspecified | — | Machine shop |

| 1-2 Luke St. | Keane & Company, Engineers | Dec. 1920 | Main machine shop |

| Moss St. | Twynham’s Mineral Water Works | — | Machine shop |

| North King St. | Maurice Fenelon’s Marine Supply | — | Explosives manufacture |

| North Strand | Tom Keogh’s house | — | Filling grenades |

| 198 Parnell St. | Heron & Lawless Bicycle Shop | 1918-1920 | Foundry & machine shop |

| Percy Pl. | Dunne Brothers Plumbers | — | Small machine shop |

| Thomas St. | Wright’s Shop (a.k.a. Vicar Street Shop) | — | Machine shop |

The level of the organization usually determined the sophistication of the site. Companies could set up bomb-making shops easily once they secured the necessary matériel. Battalions and brigades, with more significant resources available, usually established shops with greater capabilities. For instance, the Dublin Brigade found the Parnell Street factory (see below) in 1918, but GHQ took it over in September 1920. Some battalions and brigades devoted entire units to this work. Dublin’s Fourth Battalion worked a great deal in this realm, and the Fifth Battalion was an engineering unit that devoted much to this cause too. Once cast, the parts needed shaping into final form, taking off unintended protrusions, to ensure proper fit and function, as well as drilling holes, which required complex machinery.

Machine Shops

The machine shops worked in much the same manner as the foundries. At places such as the Inchicore Railway Works and the Haulbowline Royal Naval Dockyard, County Cork, individual Volunteers worked on various projects for the IRA surreptitiously, as did Joe Kinsella and his comrades in the machine shop at Inchicore Railway Works.63 The Volunteers at Rushbrooke Dockyard, County Cork, had a similar operation established where they cast metal bomb cases in sand molds in the yard and finished them in the machine shop.64 As with the foundries, some owners were sympathetic. Baker’s business also had machine tools, and the IRA workers machined most of what they produced there, with her non-IRA employees sometimes helping.65 Once completed, the devices went to another site for assembly.

Filling, Assembly, Ammunition, and Repair Shops

The filling, assembly, ammunition, and repair shops were remarkably similar. In the filling shops, the Volunteers put explosives into the finished grenades, while the assembly shops put the devices together. Sometimes machine shops could repair rifles and pistols; otherwise, unit armorers had to fix weapons on their own (see chapter 8 for more about repair).66 Some sites made ammunition.

The ammunition shops did what they could to alleviate the supply problem by making rounds, but one must make a distinction here: they did not make their cartridge cases—they loaded premade cases, either new or spent. The Munitions Directorate converted much of its .303 and .45 “rifle” ammunition to pistol ammunition,67 which was especially useful in Dublin, where rifles were of little value operationally. Its armorers disassembled each round, reshaped the case by cutting its length, and remolded the bullets. The process to reassemble the round was the same for reloading new or spent rounds: they simply reversed the process of disassembly and tightened the bullet with crimping pliers. Woods said, “We must have been successful because we never had any serious accidents as a result of faulty bullets.” They did much of this work at Denzille Lane, Merrion, which Joseph O’Connor, commandant of the Third Dublin Battalion, founded in the autumn of 1920. He also said they performed this work at Kate Connolly’s house on Frederick Street, South.68 None of this tedious work required complex equipment or particular skill but demonstrates the level of their need, the lengths they were willing to go to, and their ingenuity.

There have been charges that the Irish Volunteers used expanding bullets—hollow-point, dum-dum, and flat-nosed bullets—in their operations. There are problems with these accusations. The IRA captured or purchased most of its ammunition and thus had little control over type. Most military arms did not have outlawed ammunition made for them, so purchase was unlikely. Added to this, the Volunteers also captured much of their ammunition from the British, which, if they were the source, would have been using illegal ammunition.69 The only other viable option was that these were reloaded rounds, where the Volunteers reloaded empty cases. This would have been an instance of military expediency since placing jacketing on expanding bullets is difficult and requires specialized equipment and skill. Thus, casting nonexpanding lead bullets and using them for reloading was the best the rebels could do. In any event, these activities still did not give the Irish Volunteers sufficient ammunition for their requirements.70

Dublin Grenades

Dublin was the epicenter for grenade making, and this is already apparent based on the examination of O’Donovan’s work. The right people, facilities, and supplies came available at the right time for the Volunteers in 1918. A mechanically minded Dublin Volunteer stepped up to establish one of the first foundries for the coming conflict.

Parnell Street Foundry and Grenade Factory

Joe Lawless was interned in Frongoch after participating in the Rising. Released in 1917, he returned to Dublin where he met Archie Heron. Heron, a Belfast native and shop assistant at Messrs. Gleason O’Dea & Co. hardware store at Christchurch Place, was also a Rising veteran, an active Volunteer, and a member of the IRB. Lawless needed work, and Heron suggested he work odd jobs repairing mechanical devices, which came into his hardware store daily. He also said they should consider opening a repair shop.71

Taking this advice, Lawless saved his money, and in the spring of 1918, the pair opened Heron & Lawless, Engineers & Cycle Mechanics, a bicycle repair shop, at 198 Parnell Street. They soon found bicycle repair paid better than general mechanical repair and eventually even designed and produced a bicycle. Their business took off to the extent they hired Christy Reilly as a shop assistant and Sean O’Sullivan as part of the manufacturing process.72 Lawless was busy with the shop, the loan for which, future Dublin Brigade commandant Batt O’Connor cosigned, but Heron remained active in the republican movement.73

During the 1918 reorganization, the Volunteer leadership looked to manufacturing to alleviate the shortage of explosives. Michael Lynch, the newly appointed director of munitions, along with Engineering Directorate staff member Matthew Furlong and Joseph Vize, began a search for a suitable factory. Lawless said that he and Heron convinced Lynch that the various bomb components would not attract much attention in a repair shop. Lynch was dubious but assigned Mathew Gahan to make simple pipe bombs.74

Lawless, unimpressed by the crudity of pipe bombs, suggested to Lynch they get the foundry in the basement of the shop working to produce bomb components.75 Lynch’s initial reaction was skeptical again, but Lawless spoke to Dick McKee and George Plunkett, and they were more positive. After more discussion, they took Peadar Clancy to the shop and examined the furnace. As commandant of the Dublin Brigade, McKee decided to repair the furnace and start making grenades.76 Although not initially a GHQ enterprise, Lynch’s directorate, along with the Engineering Directorate, assisted in the establishment and running of the factory. Rory O’Connor, GHQ engineering officer came around to survey the site and decided the flue could withstand the higher temperatures needed to smelt iron.77 O’Connor sent Furlong to prepare the site for the necessary changes. His colleagues Thomas Young, Sean O’Sullivan, and Paddy McHugh joined the work.78

The group installed a five-inch German-made lathe, purchased from Messrs. Ganter Jewellers on South Great George’s Street in the Temple Bar district who had reacquired it as surplus from the National Shell Factory on Parkgate Street. The British army had originally requisitioned it from the Ganters, who were of German origin, at the outbreak of the world war; thus, the IRA used a German lathe (owned by German Irish) that had produced British munitions to fight the Germans to make bombs to be used against the British. Their first lathe operator was Joe Furlong, brother of Matthew, who had worked at the Broadstone Works of the Midland Railway and “gave invaluable help” requisitioning the necessary tools. With this and other equipment they acquired over time, the rebel arms workers got the factory running before the end of the year.79

Tom Young became one of the molders and later said that they tricked “an Orangeman in the Royal College of Science” into making the molds. Dick Walshe then made metal dies for some of the firing components, which the molders then cast in aluminum. Using dies instead of sand sped the process considerably, increasing output to forty units per day.80

By January 1919, the arms factory staff was making cases and all other metal grenade components at the foundry. The workers used normal Morgan brass crucibles and “standard foundry sand” and cast the grenade cases in iron three days per week and the other parts in brass one day a week. Since the rebels used the same crucibles for iron and brass, they went through them quickly due to the considerably greater heat used. Once cooled, the workers machined the parts on site to smooth the edges. Matty Furlong bored holes in the cases and firing mechanisms.81

Sean O’Sullivan and Paddy McGrath tested their first grenade at Aungier Street in March 1919. O’Sullivan said they put it in a bathtub with an “iron sheet on top of the bath and as many sacks as possible.” After detonation, they “collected the fragments” and were satisfied by the pattern of the fragment holes in the iron sheet.82

Each evening the munitions staff removed the day’s production by stringing the parts onto harnesses worn around their necks and covered them with large overcoats. They used Seumas Donegan’s tobacconist shop on Aungier Street, across from Whitefriars Street Church, as an assembly site. Another location was on Dominick Street. When production increased, Volunteer Chris Healy used his pony and cart for transportation. He delivered the half ton of hard foundry coke that the foundry consumed every other week too.83

The amount of coke Healy delivered indicates the level of production; the operation used about one hundred pounds of foundry coke every day. Further, Lynch had Bill Mombrun, the manager of the General Electric Company in Dublin, provide the foundry soft foundry coke.84 Their goal was to produce one hundred grenades per week and, during the time Lynch was in charge, they made about five thousand at a cost of approximately £2,250 in total.85 Although McHugh said they could never produce enough to have a sufficient spares supply, they had enough to stockpile grenades in safe locations.86 What this meant was the Volunteers should have had sufficient grenades to conduct operations. Moreover, there were the other manufacturing locations within Dublin, which became more critical by the end of 1920.

The men of the Parnell Street site also conducted training in the construction of explosive devices for the county brigades. It is unclear if they did this in conjunction with the Engineering Directorate, which also gave training in demolition and employment of explosives in combat.87

Keen & Co., Engineers, Luke Street

For unexplained reasons, the munitions staff began looking for new sites by the early autumn of 1920. It opened the first at 1 and 2 Luke Street, just off Georges Quay, in late 1920. After a November 1920 police raid on Heron & Lawless, the QMG opened smaller factories around the city, but the QMG put greater effort into Luke Street.88

Figure 4.2. Map of Some IRA Arms Factories in Dublin

The first work at Luke Street was making grenades, but by January 1921, with the recently laid electricity working and new machinery in place, the workers began producing firing sets like those from Heron & Lawless. They made about 250 firing sets a day, which went to Mount-joy Square each night for assembly with parts from other locations into completed grenades. It is unclear if they opened the Mountjoy Square site due to a compromise of other sites or if it was due to increased volume. The QMG also sold firing sets to brigades throughout the country. The other brigade factories made the cases and some of the other parts, then finished the bombs with GHQ firing sets.89 This also demonstrates the IRA was at least moving toward standardization since the cases had to be compatible with the sets.

Another factory, mentioned earlier, the Baker Iron Works facility on Crown Alley, had a gas-fired furnace, with an air compressor attached. This meant workers could heat their metals considerably faster and produce more cases in a shorter period. At one point, they produced three hundred cases in an eight-hour shift, which went to Luke Street for boring.90

Making Other Products

While the Chemicals Directorate and Munitions Directorate jointly manufactured explosives and grenades, the latter also made other equipment. As early as May 1919, Munitions had sufficient capabilities to produce wooden rifle stocks, which required complex lathes and skilled artisans. These men worked in the repair shops of the Fourth Battalion, Dublin Brigade, and not only had skilled woodworkers but qualified gunsmiths too. Therefore, when director of purchases, Joe Vize,91 bought rifles, lacking only the wooden stocks, the men in the Heron & Lawless factory manufactured replacement stocks since they had the lathe and had a man sufficiently skilled, likely Furlong, to work it.92 The relationship between the Dublin Brigade and GHQ was different from that with the county brigades due to proximity. Somewhat by design, GHQ and particularly the QMG used Dublin Brigade assets duties within its directorates. These duties were not technically within the purview of the brigade, but with brigade officers usually serving concurrently in the GHQ staff, they could use whatever assets they needed.93

One must judge the success or failure of military organizations by assessing performance, which is generally more complicated in an insurgency than in a conventional war. While the concluding chapter will examine this with the greater whole, it is sufficient to mention that the rebels never had enough of what they needed. Considering what the British arrayed against them, these efforts, along with the demonstrable abilities to improvise and adapt, were more remarkable.

Table 4.2. Some IRA Arms Factories outside Dublin

| Address | City/County | Front company | Operative years | Primary function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balieborough | Co. Cavan | — | 1921 | Machine shop |

| Abbeymahon | Co. Cork | Home of the O’Driscolls | — | Bomb factory |

| Ardmore, Trimoleague | Co. Cork | Home of Jeremiah Lehane | — | Bomb factory |

| Ballineen | Co. Cork | — | — | Bomb factory |

| Ballinlough Rd. | Co. Cork | Home of the Nevilles | Bomb factory | |

| Ballycullane, Ballynoe | Co. Cork | — | 1918 | — |

| Ballylegane | Co. Cork | — | 1918 | — |

| Ballyvourney | Co. Cork | — | 1918 | — |

| Balteenbrack | Co. Cork | — | — | |

| Carrig | Co. Cork | Home of Con Murphy | — | Bomb factory |

| Donoughmore | Co. Cork | — | — | — |

| Kiskeam Upper | Co. Cork | — | — | Foundry |

| Knockragha | Co. Cork | — | — | — |

| Macroom | Co. Cork | — | — | Foundry |

| Newmarket | Co. Cork | — | — | Foundry |

| Grattan St. | Cork City | Shoe repair shop | 1919 | Foundry & machine shop |

| Haulbowline | Cork Harbor | Haulbowline Royal Naval Dockyard | 1915 | Foundry & machine shop |

| Parnell Pl. | Cork City | Messrs. Merrick & Sons | — | Foundry (commercial) |

| Dockyard | Co. Cork | Passage West Dockyard | — | Foundry & machine shop |

| Dingle | Co. Kerry | — | — | — |

| Lispole | Co. Kerry | — | — | — |

| Newbuilding Ln. | Kilkenny | — | — | — |

| Drogheda | Co. Louth | — | — | Foundry (commercial) |

| Carrickmore | Co. Tyrone | — | — | Foundry & machine shop |

| Adelphi Wharf | Waterford | — | — | Foundry |

| Cork Gas Works | Cork City | — | — | — |

| Keeloges, Oola | Co Limerick | — | — | — |