9

Assessment of the Republican Arms-Procurement Campaigns, 1918–1921

To be coercive, violence has to be anticipated. And it has to be avoidable by accommodation. The power to hurt is bargaining power.

—Thomas C. Schelling Nine

The Irish Volunteers did not develop mature organizational structures in any modern sense. Most units, from the company to the division levels, had, in addition to commandant and vice commandant, a quartermaster, an intelligence officer, and a transportation officer. The existence of additional staff officers depended on the time, location, need, and level of the unit. Modern armies have charts, tables, and descriptions detailing the various personnel and equipment authorized based on the unit’s size and function. These ensure that the unit, and any subordinate units, are staffed and equipped for the missions envisaged for them or that any deficiencies with personnel or equipment stand out. The absence of these structures and documents for the IRA makes analysis of the arms activities more difficult because the developmental processes over time were ad hoc and personality-driven. This does not mean one cannot determine sound principles for evaluation.

Criteria for Assessment

When examining issues of success and failure in a campaign like the republican attempts to arm the Irish Volunteers during the War for Independence, one would ideally want to have clear, demonstrable measures of effectiveness against which to assess objectively. Unfortunately, for these types of scientifically led inquiries, one must have access to detailed records from which to derive data for quantitative analysis, but accurate and complete records do not exist for this conflict.

An amateur student of war might be tempted to say that there is no better evidence of effectiveness in war than victory. While not wholly incorrect, this Eurocentric, annihilation-or attrition-focused, and simplistic view of war is too facile to be useful here. One would need to append too many caveats to this argument that it would be devoid of meaning. Added to this, military victory in revolutionary guerrilla war is considerably different than in other wars and not measured in the same ways.

The most obvious criteria to help determine effectiveness would measure quantity, frequency, predictability, and whether the fighting units had what they needed. The issue, given the nature of the republicans’ arms activities, is whether standard military measures of effectiveness really apply. Thus, while being capable of answering each of these criteria from a quantitative standpoint would be ideal, it is simply not possible given the nature of the topic and the sources available. This does not mean that the factors listed are not useful or that addressing them from a qualitative approach would not be fruitful. While this section will not answer each criterion point by point, qualitative answers to them generally will inform the rest of the analyses. Thus, this chapter will incorporate as many of these factors as possible in relation to the sources available.

The QMG “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Books”

The IRA QMG kept “army goods inwards and outwards books” to track supplies received and distributed to the fighting force by GHQ. Unlike the reports from the divisions, which contained information reported from the brigade and battalion quartermasters, there was no reason for the QMG to fabricate numbers received and distributed. The battalion and the brigade quartermasters admitted that they did not report to their higher headquarters all of the arms and munitions they held, for fear of being ordered to give up weapons to other units. Therefore, there is an admitted level of error or deceit in their reports. The QMG account books tracked everything that came through the department but, unfortunately, do not always list the source of the matériel. This means that it is the most inclusive set of records in terms of sources, origins, and destinations for the war but still not wholly accurate or complete. These books record a single point of reception because most of the matériel coming into the country passed through Dublin at least briefly and then went out to the units in the countryside. Also, the provenance of the books is considerably clearer than the reports of the various units at the various levels throughout the country. It is never entirely clear who wrote the reports forwarded to the higher headquarters, and so their veracity is sometimes hard to establish. Finally, the account books only record arms passing through GHQ and do not include other sources; therefore, these books constitute the most accurate data for analyzing the QMG and GHQ efforts. The analyses in this chapter will use these account books as the main sources, supplemented with other documents as necessary.

The Levels of War

In addition to the data, when examining successes and failures for any military effort, one must also ascertain the level of war (tactical, operational [grand tactical], strategic, and grand strategic) because it is possible to succeed at one level of war and fail at another. The Pyrrhic victory is the classic example, whereby the victor loses more than he gains. If this trend continues, the victor, having achieved several such “victories,” could end by losing the campaign or even the war. The Germans in the world wars suffered this fate by attriting their forces and their combat capabilities in victories to the point where they lost the wars. This gives rise to the German aphorism that Man kann sich totsiegen (“you can win yourself to death”).

Thus, to examine the republican arms-acquisition efforts requires a multilevel approach, examining the levels of activities within their contexts. Of course, this will look at the elements of the system and activities. Only then may one place the entire effort into context and judge its success, utility, and failures.

Tactical- and Operational-Level Arms Procurement

The arms-acquisition methods at the beginning of the war—theft, raid, and ambush—could only get the war started, not sustain a substantial war effort against the United Kingdom and its empire. Purchasing arms and munitions was the next logical step. While smuggling provided more weapons than the old methods, it still did not yield the volume of support the rebels needed to sustain their war effort. The IRA was militarily little more than an annoyance; the rebels could cause trouble locally but could not conduct significant combat operations against the British army at any major level. The IRA could win tactical engagements against small, isolated detachments and convoys but not against larger forces in the field. Failing this, the rebels were not going to cause the level of disruption they needed to win the war. If the goal was military victory, the rebels needed more weapons. The republicans tried to make what they needed.

Table 9.1. Measures of Effectiveness for the Republican Acquisition Efforts

| Quantity | Increase in combat effectiveness | Frequency of supply | Predictability | Combat units had what they needed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amounts imported | Combat units increased ops after (re)supply | Supplies of ammunition came when needed | Supply regular | Majority of Volunteers armed sufficiently |

| Amounts lost to theft, discard & capture | Frequency or complexity of ops increased | Supplies of weapons came when needed | Supply predictable | Not a limiting factor for ops |

| Amounts distributed to fighting units | Supplies of explosives & explosive devices came when needed |

One ultimately may only really make well-informed guesses about the lengths to which the QMG went for manufacturing. What is clear is that the QMG personnel manufactured what the Directorate of Munitions told them to make in the quantities that were possible with the raw materials they had (provided by the Purchase and Chemical directorates). In this, they were successful. For example, in 1921, Collins wrote to Patrick O’Daly in Liverpool asking for springs. Unfortunately, the design and description of this spring did not survive, but based on the quantity and clear extreme need for them, they were probably used in IRA grenades and bombs. By the volume of production, Collins’s requests for them bore this out; by March 1921, he said that the QMG needed one thousand springs per week (for quantities of what they produced, see below).1

Tactical- and Operational-Level Assessments

The efficiency of the constituent directorates largely determines the effectiveness of the QMG, just as the efficacy of the arms centers decides the value of the arms-procurement activities. The simplest measure of these enterprises is to determine how many weapons were in the hands of the IRA at the time of the truce, especially considering the widespread belief among the republicans that the IRA was actually prepared to continue the war.

Weapons

Historian Gerard Noonan has found that “by early 1921, the Volunteers in Ireland had 4,156 members but only 2,035 firearms—569 rifles, 30 miniature rifles, 477 revolvers and 959 shotguns.”2 Interestingly, some two weeks after the treaty signing, in what was likely a political attack on GHQ, which was clearly and overwhelmingly protreaty, Cathal Brugha queried the QMG (Sean McMahon) and the directors of munitions (Sean Russell) and purchases (Liam Mellows) on their effectiveness. All three made written replies giving totals for the war up to the truce and then to December 1921. While the original query from Brugha did not survive, the cover letter from McMahon indicated that “allegations that have been made” about what these organizations had done throughout the war. While this was likely part of Brugha’s machinations to weaken GHQ’s power base before the treaty-ratification debates and vote the next month, it also reflects the widespread belief that GHQ, the QMG, and especially Collins did not do enough for the units engaged in the fighting. Tom Barry, for instance, reported that in early 1921, officers from the three Cork brigades and South Tipperary met to urge GHQ to import arms and to spread the fight to nonfighting areas. Barry also implied that the Cork brigades were not getting their fair share of weapons. What Barry did not know, and Collins did not have the temperament to tell him, was that the arms centers, the director of purchases, the director of munitions, and the QMG generally were doing everything in their power to bring in weapons.3

Further, as quickly becomes clear from the available records, Munster got more than its share of arms, to the detriment of other regions.

Ammunition

Brugha’s questions, which, however politically motivated they probably were, remained valid, and the memoranda produced to answer him provide interesting details. Russell claimed to have purchased 91,982 rounds of ammunition from August 1920 to July 1921. Based on the QMG account books, though, the QMG received 97,390 rounds form September 1920 to July 1921, thus making a discrepancy of 5,408 rounds. It was probably that the QMG received ammunition from sources other than the Directorate of Purchases, which is the simplest and most likely explanation for the difference. The problem, however, is not that the QMG Department claimed fewer rounds than it had received but that it included noncombat rounds to reach these totals. From September 1920 to July 1921, the QMG received 53,617 rounds of ammunition suitable for combat (ranging in caliber from .30 to .50 pistol and rifle, and shotgun ammunition of varying gauges). To reach the 97,390 (or the 91,982) numbers, the QMG had to add in the 43,773 rounds of .22 and .297/.230 (Morris tube4) ammunition, none of which was suitable for combat due to their lower weight and smaller caliber.5 The QMG included these rounds as combat ammunition, which made the numbers almost double. There were other discrepancies in the reports.

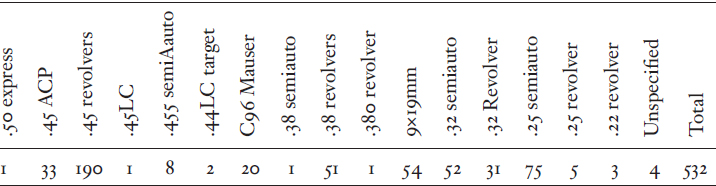

Table 9.2. Pistols Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

Source: “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book,” vols. 1–6, September 1920–July 1921, NAI DE 6/11/1–6.

Table 9.3. Rifles Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

| Lee-Enfield | Ross | Mauser | “Howth” | Martini | Winchester | “Miniature” | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 73 |

Source: “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book, vols. 1–6, September 1920–July 1921, NAI DE 6/11/1–6.

Table 9.4. Munitions Passing through QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

| Rifles | Pistols | Rounds of Ammunition | Pounds of Explosives |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 532 | 53,617 | 14,041.875 |

Source: “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book,” vols. 1–6, September 1920–July 1921, NAI DE 6/11/1–6.

Note: The .22-caliber and Morris tube ammunition, by no means suited for combat, would have added only 43,773 rounds to this total.

Table 9.5. Arms and Ammunition Imported and Distributed

| Description | 16 August 1920—11 July 1920 | 11 July 1921—17 December 1921 |

|---|---|---|

| Machine guns | 6 | 51 |

| Rifles | 96 | 313 |

| Pistols | 522 | 637 |

| Rifle ammo | 21,673 | 18,232 |

| Pistol ammo | 45,680 | 63,675 |

| Shotgun ammo | 24,629 | 16,574 |

Source: IRA QMG, “Report on Activities of Department,” 19 December 1921, MAI A/0606.

Table 9.6. Pistol Ammunition Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

| .50 exp | 140 | .38LC | 119 |

| .45 ACP | 5,425 | 9×19mm | 3737 |

| .45 | 9,498 | 7.63×25mm (C96) | 231 |

| .45LC | 3,879 | .380 rev | 2,038 |

| .455 | 223 | .32 semiauto | 1,038 |

| .450 | 60 | .32 | 3,751 |

| .44LC | 170 | .32 rim | 26 |

| .442 | 89 | .25 semiauto | 1,545 |

| .38 semiauto | 1,247 | Unspecified | 3,477 |

| .38 | 4,756 | Total | 40,849 |

Table 9.7. Ammunition Available, 21 March to 20 June 1920

| .455A | .455R | .450R | .442R | .303LE | .320R | .32A | .32R | 7.92 mm | 7.63×25 mm | 9×19 mm | Unspecified | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 712 | 261 | 66 | 366 | 40 | 14 | 125 | 103 | 30 | 1,356 | 713 | 222 | 4,008 |

Source: “Arms Accounts,” Fintan Murphy Collection, MAI CD 227/10/567.

Table 9.8. Rifle Ammunition Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

| .303 | 10mm | .45 Winchester | .38 Winchester | 7.9mm | .32 Winchester Special | Miniature rifle | .295 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,312 | 10 | 40 | 60 | 403 | 30 | 1,380 | 136 | 10,371 |

Source: “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book,” vols. 1−6, September 1920”July 1921, NAI DE 6/11/1−6.

Table 9.9. Shotgun Ammunition Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

| .410-gauge | 12-gauge | 28-gauge | Unspecif1ed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56 | 329 | 15 | 1,997 | 2,397 |

Source: “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book,” vols. 1−6, September 1920−July 1921, NAI DE 6/11/1−6

Table 9.10. Munit1ons Available, 21

Source: “Arms Accounts,” Fintan Murphy Collection, MAI CD 227/10/567

The Directorate of Chemicals, under James O’Donovan, worked to provide explosives and other useful chemical compounds. O’Donovan and his assistants worked under terrible conditions, using volatile chemicals to develop explosive compounds, especially war flour and Irish cheddar, that Irish Volunteer chemists could make throughout the country. Even with insufficient materials, O’Donovan and his directorate produced some two and a half tons of high explosives. These explosives had the potential to cause significant disruption and loss of life and property throughout Ireland.6 The QMG accounts state that Munitions delivered 5,701.75 pounds of explosives, although the amounts of explosives include those received from all sources, not just O’Donovan’s directorate.7

Likewise, the Directorate of Munitions ran at least a dozen munitions factories and two foundries of varying sizes and capacities throughout Dublin, and these do not include the other foundries producing munitions in Dublin that the IRA did not control, such as the Baker Iron Works. These facilities produced bombs, grenades, parts for grenades, and other items. Munitions claimed to have produced 2,209 grenades from August 1920 to July 1921, but the QMG accounts record receiving Table 9.11. Explosives (in Pounds) Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921 only 989 grenades from September 1920 to July 1921. It is not clear why there are discrepancies in those records. For instance, these sites manufactured at least 4,242 “grenade necks” too. While there were flaws in some of the devices, these do not appear to have been the result of manufacture. It would appear the faults with the devices were with design, although this is impossible to know definitively without access to the devices or testing results. Therefore, one must conclude that Chemicals and the manufacturing part of Munitions were successful in their tasks and missions because they produced what they were directed to whenever provided sufficient materials to do so.

Table 9.11. Explosives (in Pounds) Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

| Ammonium nitrate | Barium nitrate | Din1trotoluene (DNT) | Gelignite | Gunpowder | Irish Cheddara | Lumite | Potassium chlorate | War Flour | Unspecif1ed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 4,704 | 144.25 | 300.125 | 364.5 | 4,520 | 584 | 2,416 | 1,064 | 174.75 |

Source: “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book,” vols. 1–6, September 1920 to July 1921, NAI DE 6/11/1–6. The Directorate of Munitions also made 4,346 grenade necks during this period.

a This figure includes Irish Cheddar received from sources other than the Directorate of Chemicals, which provided the QMG 4,049 pounds of Irish cheddar during this period. See “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book,” vols. 1–6, September 1920–July 1921, NAI DE 6/11/1–6.

Finance

An army, as the old proverb says, may march on its stomach, but the rebels needed money. Although this was an enabling function, it is important to note its criticality. Smuggling is an expensive business, and it was a losing proposition from a funding standpoint. This was something Brugha either did not understand or merely used to attack Collins. The movement was not going to make money; its “product” was fighting capability and capacity, and this it delivered, one seafarer at a time.

Furthermore, the republicans were playing a numbers game: for each capture, more got through. This required volume, and the common denominator of acquisition and smuggling was money. The closing of republican finances would have effectively ended any significant purchasing activities. The British tried to follow the money trail by having magistrate Alan Bell investigate financial records throughout Dublin. He must have gotten too close because the Squad assassinated him in Dublin on 26 March 1920 in broad daylight.8 This probably indicated that Bell was the single greatest threat to the republican movement in the first half of that year.

Table 9.12. Director of Munitions Report on Grenade Manufacture

| Division | Number of foundries | Grenade cases manufactured by 31 October 1921 |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Southern | 3 | 3,060 |

| 2nd Southern | 1 | 470 |

| 3rd Southern | 2 | 166 |

| 1st Western | 1 | 133 |

| 3rd Northern | 1 | 1,000 |

| 1st Eastern | 1 | 1,740 |

| South Dublin | 1 | 60 |

| Dublin City | 1 | 3,000 |

| Total | 11 | 9629 |

Source: Director of Munitions to Minister for Defence, “I.R.A. Armament,” July 1921, Collins Papers, MAI A/606/III.

Table 9.13. Explosives Components Received by QMG Department, September 1920 to July 1921

| Electric detonators | “Ordinary” detonators | Fuses (1n feet) | Springs | Grenadesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 865 | 8,967 | 1,860 | 3,699 | 1,007 |

a The Directorate of Munitions provided 989 of these. The remainder came from other sources.

More importantly, the purchasers normally had sufficient funds for operations, unless they made mistakes and Collins had to send emergency relief. Keeping normal financial accounting books was simply asking too much from the purchasers and smugglers, a weakness Brugha later tried to exploit. Financially, in no small measure due to de Valera’s and other republicans’ fundraising efforts in America, the republican arms-acquisition efforts were as financially sound as they could have been.

Communications and Transportation

The IRA excelled in the closely allied realms of transportation and communications, especially considering the constraints of geography and the impediments emplaced by British security. Rebel communications, through which the arms and munitions passed, were rapid and usually secure, while extending throughout the United Kingdom, especially Ireland, and the rest of the world. In real terms, the rebels communicated wherever and with whomever they wished, virtually at will. In the same way, they transported and smuggled people, weapons, munitions, and almost any other supplies throughout the world. Owing to the anonymity of the republican couriers, the Volunteers moved virtually unhindered within Ireland. Further, the rebels surreptitiously transported coal, coke, and chemicals by the ton without attracting attention by masking them with legitimate businesses.

The rebels’ attempts to communicate safely and securely were successful overall. They could move a letter or package anywhere in Ireland in about four days and to Britain or the continent within a week; to the Western Hemisphere took at least two weeks. Critical to this was the infiltration by various nationalist and republican organizations into the Royal Mail. Many republicans joined the post office, while many others who were already working there joined various republican groups. This also had tremendous effects on the republican intelligence capabilities.9

The assistance of the railway workers was also critical to the communications and transportation efforts. Couriers could only convey so much; large shipments had to move by rail. By establishing way stations, by essentially looking the other way when the extra matériel or people came aboard, the railwaymen and -women formed part of the backbone of the communications network. Without the rail workers, the dockers, postal employees, and Cumann na mBan, the system would not have worked.

Moving matériel to and from the arms centers overland in Britain was dangerous work and one of the most valuable services the men and women of the IRA brigades, the IRB, and Cumann na mBan performed in Britain. Given the efforts of the men and women of the republican movement to acquire, manufacture, pay for, transport, and distribute weapons and munitions of all kinds and types, one must rate these “tactically”—and “operationally”—successful overall.

Assessment of Strategic-Level Arms Procurement

Despite the best efforts, sacrifices, injuries, deaths, and simple hard work of those involved in arms acquisition, the IRA still did not have enough weapons, ammunition, and explosives to fight the war to military victory at the truce. By any standard, while there were many successes, one must judge the overall, or strategic-level, arms effort a failure based on the stated goal of arming the Irish Volunteers for sustained combat operations.

The IRA needed large numbers of weapons and sufficient ammunition to sustain significant ground combat against British forces. By the spring of 1921, the British army was increasingly conducting cordon-and-search operations during combined arms “drives.” These involved infantry (both vehicle-mounted and dismounted), artillery, cavalry, and aircraft, with the Royal Engineers in support to deal with countermobility obstacles. Against these operations, the IRA needed to put hundreds of men into the field, ceding their natural advantages as guerrillas, especially elusiveness, lest the men be captured or killed in planned enemy offensives. Leaving aside the issue of whether or not the IRA was otherwise prepared to fight in a conventional manner, it was not armed sufficiently to resist these types of British combined arms operations by July 1921.

The only means of arming the rebels to this level was massive shipments of arms. With the exceptions of the Hoboken Thompsons and the Italian arms operation, there were no other large arms-landing operations to move beyond the mere conceptual phase. It is also significant that these two operations failed. Further, neither the Hoboken nor the Italian operations would have provided sufficient ammunition reserves with which to fight for long. These would only have delayed the inevitable military defeat, had the republicans chosen to fight conventionally in 1921.10

The Brilliance and Failure of Rebel Manufacturing

The rebels had turned to manufacturing to obtain explosives and explosive devices. Although the directorates of Chemicals and Munitions made substantial amounts of high explosives and grenades and bombs, these were not going to change the outcome of the conflict. One must question the utility of these weapons, especially given their apparent failure rates.

The frequency of malfunction, and worse, of accidental explosion, was such that the utility of these weapons was spotty at best. While there are no clear quantitative data, the malfunction problems affected Volunteers’ confidence in the weapons, especially grenades. The accidents and malfunctions were common enough that the IRA was often loath to use them. These weapons were only useful in a close fight—one where the forces engaged were close enough to throw the grenades by hand. In rural guerrilla battles, these weapons were less useful (and less commonly used), whereas in the towns and cities, where they saw more use, the frequency of the malfunctions affected use. The best use of bombs was as a road mine for ambushes, particularly against armored vehicles, but there was more to this issue, especially the ammunition shortage.

Historians Mo Moulton and Gerard Noonan have gone a step further and separately suggested that the IRA was either out of weapons and ammunition, or very close to it, by the time of the truce. Noonan cites captured rebel documents saying that the IRA “had only 43 rounds of ammunition for each revolver they possessed, 21 rounds for each rifle and seven rounds for each shotgun.”11 If true, this was not sufficient for any sort of prolonged combat operations against British army drives. Moulton quoted from Sean McGrath’s statement to Ernie O’Malley about a conversation McGrath had with Collins, who said that he would never have signed the treaty if the IRA sufficient weapons.12 While neither source is definitive, when combined with other information, such as the increasing cancellation of operations due to insufficient ammunition in 1921, as detailed in previous chapters, this is more than suggestive. Matt Kilcawley, vice commandant of the North Mayo Brigade, for instance, said that when he was in the column, he and his men were forced to conduct a quick attack at Loughglynn, County Roscommon, on 19 April 1921, with only three rounds of ammunition per man.13 Considering the columns and ASUs were handpicked and given more ammunition whenever possible, this incident is telling.

Further, the situation in the spring of 1921 became so severe that Mulcahy got involved directly in the arms business that Collins was running, an almost singular event. When the financial situation in the Glasgow arms center got to the point where the center had insufficient funds to purchase nine thousand rounds of ammunition, as mentioned in the previous chapter, Mulcahy not only ordered a full financial accounting, but also ordered Munitions to shift manufacturing to ammunition.14 Unfortunately for the Volunteers, this directive came too late to influence their shortages.

While these issues are telling, this is still insufficient evidence to prove the IRA was out of weapons or ammunition at the time of the truce. Indeed, there is considerable evidence to counter this. It also seems reasonable to conclude that there was a very significant weapons deficiency of about 50 percent, according to the documents available, and ammunition supply problem was certainly a severe problem for the Irish Volunteers at the time of the truce. The problem came from several areas at once: the varied number and type of weapons and calibers in the hands of the Volunteers, the difficulty finding all types of ammunition, and the republicans’ inability to smuggle large quantities of ammunition into Ireland. Finally, this issue clearly had a deleterious effect on IRA combat capabilities.

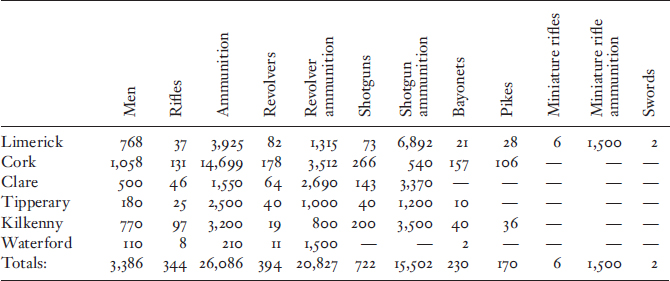

Table 9.14. Report of Arms Available in Munster, circa April 1921

Source: Lockhart to Hemming, photostat of captured IRA document, 10 April 1921, TNA HO 317/60.

Table 9.15. Corrected Reported Available Arms by Region, circa April 1921

Source: Table derived from Lockhart to Hemming, photostat of captured IRA document, 10 April 1921, TNA HO 317/60. Original document contains arithmetical errors that have been corrected in this reproduction.

Thus, when assessing the measure-of-effectiveness factor of Table 9.16. QMG Reported Ammunition Held, 19 December 1921 quantity, the republicans fall short. This clearly did not provide an “increase in combat effectiveness,” so the republicans must receive a “marginal” at best. When examining “frequency of supply,” it appears that, by the end of the conflict, the republicans had steady supplies coming and that this was “predictable.” Thus, they receive a “pass” on these. Ultimately, however, the IRA combat units did not have what they needed, in sufficient quantities in July 1921. On this criterion, they failed.

Table 9.16. QMG Reported Ammunition Held, 19 December 1921

| Ammunit1on | Southern Div1sions | Western Div1sions | Northern Div1sions | Eastern Div1sion | Midland Div1sion | Dublin Brigade | Wexford Brigade | Carlow Brigade | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifle | 64,040 | 13,250 | 30,020 | 9,220 | 3,310 | 55,330 | 2,530 | 1,790 | 179,490 |

| Shotgun | 43,260 | 8,120 | 9,460 | 7,020 | 4,460 | 5,160 | 6,190 | 3,650 | 87,320 |

| Semiautomatic pistol | 43,150 | 2,910 | 4,660 | 980 | 1,190 | 8,890 | 276 | 106 | 62,162 |

| Revolver | 24,530 | 11,000 | 9,720 | 4,000 | 2,950 | 9,059 | 1,230 | 490 | 62,979 |

| Grenades | 3,696 | 683 | 1,698 | 1,740 | 160 | 321 | 133 | 64 | 8,495 |

| Explosives (lbs.) | 3,800 | 2,490 | 3,380 | 960 | 550 | 95 | 296 | 150 | 11,721 |

Source: Director of Munitions to Minister for Defence, “I.R.A. Armament,” July 1921, Collins Papers, MAI A/0606/vi.

Table 9.17. Munitions Procured by the IRA, December 1920 and November 1921

| Machine guns | Rifles | Pistols | Rifle ammunition | Pistol ammunition | Sundry ammunition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57 | 463 | 1,047 | 59,316 | 80,727 | 52,000 |

Source: Director of Munitions to Minister for Defence, “I.R.A. Armament,” July 1921, Collins Papers, MAI a/0606/vi. These numbers do not include the unreported weapons coming in for brigades before the external pipeline to them was severed by order of Collins or those that were sent directly to Cork later on Collins’s order.

Table 9.18. QMG Reported Ammunition Held, 19 December 1921

| Firearms | Southern Divisions | Western Divisions | Northern Divisions | Eastern Divisions | Midland Divisions | Dublin Brigade | Wexford Brigade | Carlow Brigade | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifles | 1,531 | 417 | 648 | 147 | 123 | 305 | 91 | 33 | 3,295 |

| Shotguns | 7,356 | 2,279 | 1,509 | 1,706 | 1,012 | 240 | 744 | 411 | 15,257 |

| Semiautomatic pistols | 597 | 138 | 167 | 53 | 24 | 119 | 14 | 8 | 1,120 |

| Revolvers | 1,789 | 2,430 | 859 | 241 | 263 | 711 | 93 | 54 | 6,440 |

| Machine guns Thompsons | 14 | 9 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 2 | — | — | 43 |

| Lewis guns | 4 | — | — | — | — | 3 | — | — | 7 |

| Hotchkiss guns | 4 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 5 |

Source: IRA QMG Report, “Report on Activities of Department,” 19 December 1921, MAI A/0606.

As with so many factors in this realm, there is more to the story. While the IRA was struggling to obtain sufficient weapons and, especially ammunition, at the time of the truce, this greater examination must take into account the “truce era” (July 1921 to January 1922) and beyond because the protreaty side argued that there was insufficient weaponry to continue a renewed war. The records from GHQ clearly indicate significant increases in weapons and ammunition passing through the QMG to the end of 1921. Considering again that the divisions probably had more than they reported, the rebels were far better armed in January 1922 than in January or July 1921. The arms stockpiled grew from 2,075 firearms to 26,156, while the ammunition supplies had grown from 33,393 in the spring of 1921, to 391,951, an almost tenfold increase in just under a year.

While the number of the rifles the rebels in the units imported is unknown, without the resources that GHQ had these could not have equaled another 10 percent. Thus, more than 80 percent of the IRA’s rifles were captured or seized. In a similar vein, even with the ninety-seven thousand rounds of ammunition of all types that the QMG smuggled into the country, this was less than one third of what the IRA held as a whole by December 1921. Of course, that number is based on what the units reported they held, rather than what they actually held; the ratios were probably greater. This leads to the inevitable conclusion that the brigades were far more successful in their efforts to acquire arms and munitions than GHQ was in supplying them.

These increases in arms and ammunition are impressive by any standard, yet these massive increases do not tell the whole story either because these numbers are by class, not by caliber or type. One cannot calculate rifles available per Volunteer because there still were not enough rifles by December 1921 to arm each man. Thus, hypothetically, if all of the rifles were the same (they were not) and used the same ammunition (they did not), the rebels could only arm about three quarters of their men with rifles and only fifty-four rounds each. One could subtract the roughly fifteen hundred men of the Dublin Brigade from these calculations because of the nearly exclusive use of handguns in the city.15 Thus, one would find that the remaining IRA could be armed with rifles, and each man would have had more ammunition.

Just as the Dublin Brigade used the disposable and concealable pistol, it did not need heavy or light machine guns. The former were only useful for site defense due to their weight, while the latter were only beneficial as part of a rifle squad in rural environs. Surprisingly, although the Belfast Brigade used rifles (as detailed in Chapter 7), the IRA there did not want the light machine guns they were given in the arms exchange in 1922. This may have been due to a lack of operational experience, a lack of capable machine gun training, or the tactical reasons peculiar to Belfast.

Thompson submachine guns were new, untested, and held in awe by Volunteers, but the weapons were not terribly useful at the longer engagement ranges common in the rural brigades because they fired the .45 Automatic Colt Pistol cartridge. They were really only useful for closer fights—the same ranges as pistols or, at best, shotguns. Only the German army in World War I had used submachine guns in combat and then only among elite troops; thus, there was no doctrine available for their employment at this time. Further, while there is no way to know precisely how many rounds of .45 ACP ammunition the IRA had, the QMG received some ten thousand semiautomatic pistol rounds (.32 ACP, .38 ACP, 9mm Parabellum, and .45 ACP) during the war; of this, about half was .45 ACP. Thus, it is reasonable to assume the same ratio for the sixty-two thousand rounds of “automatic pistol” ammunition reported by the QMG. Some 13.6 percent of the semiautomatic pistols that the QMG received during the war were M1911 .45 ACPs, so it is also reasonable to assume the same ratios for the rest of the IRA. Thus, the man carrying an M1911 pistol in combat would probably carry at least four seven-round magazines in addition to one in the weapon and would have a total of thirty-five rounds. The M1911s would require some 4,550 rounds of ammunition, leaving 26,450 rounds for the Thompsons. These ratios would leave about 615 rounds of ammunition per submachine gun. These would have been quite effective if used properly—in an urban environment or close quarters. The problem was that the Thompsons were held disproportionately in Dublin, which was appropriate, and in the south, which was not. Given the imbalance in weapon types, calibers, and distribution, it is hard to see that the IRA would have been effective in renewed, more conventional war, but this was not necessarily what was going to happen if fighting broke out again. While it could be that Collins was unaware of Munster’s success, he must surely have known that the southern divisions had the equivalent of half of the combat ammunition that the QMG had imported by December 1921 and that Muster had it by April 1921. The April report contains errors that are inexplicable—the claim that all IRA brigades had less than half the amount of ammunition that Munster held by itself, for instance. The protreaty claim of insufficient ammunition does not stand up to scrutiny and would appear to have been fabrication on at least the QMG’s part, if not Collins’s and Mulcahy’s. Thus, any claim that the truce was necessary due to lack of ammunition is demonstrably false. Further, the claim from Piaras Beaslai that Liam Lynch, commandant of the First Southern Division, said the southern divisions were running out of ammunition is also false.16

As distasteful as it is for this researcher (undeniably no admirer of Brugha) to admit, Brugha’s questions to the QMG in December 1921 were entirely valid given the criticality of the questions at hand the next month during the treaty debates and the emphasis that Collins would then place on ammunition. Indeed, given this evidence, Brugha would have been negligent if he had not pursued this line of questioning. Furthermore, it appears that the QMG, Sean Russell, knew that the divisions had armed themselves for the fight and that the QMG Department was not nearly as effective as the underresourced fighting units.

Responsibility

At this point, it is important to take stock of the status of the analysis. The issues raised thus far fall into several categories: systemic, relational, temporal, and situational. The systemic concerns were the processes for arms acquisition that the groups developed during the course of the conflict. The domains within acquisition are purchasing, manufacturing, smuggling (communications and transportation), financial, and distribution. The republicans developed processes for the situations that confronted them. Most importantly, these efforts succeeded to some extent.

The relational refers to the various entities involved at the multiple levels. Intra-agency issues were those of the groups involved such as the arms centers, the QMG, the IRB, and even the Dáil. One can also see the interagency problems between the IRA, GHQ, the brigades, the Ministry for Defence, the Ministry for Finance, and the Dáil. The interdepartmental affairs, especially within GHQ and the directorates of Organisation and Intelligence, and the QMG (directorates of Purchases, Munitions, Chemicals, and Transport and the Engineering Office). One cannot ignore the concerns of the various external agencies such as the IRB, Cumann na mBan, Na Fianna Éireann, and the Clan na Gael. All of these bodies working in the same realm at once was difficult at best.

This situation was complex. There were no easy answers to the multitude of issues and problems that confronted the republicans. There was, however, one man in the republican movement with the access, contacts, knowledge, influence, and capability—not to mention authority (acquired, assumed, delegated, or otherwise)—to have positive influence over these issues: Michael Collins. As minister for finance, he had the resources available to fund acquisition of just about anything they needed. This failure was not about an inability to pay. The problem was one of smuggling and manufacturing priorities.

The republican global smuggling network was sufficiently robust to move anything they acquired—from coal, to coke, to iron and brass, to volatile chemicals—in addition to arms, ammunition, and explosives. The issue was that sending raw materials was, in many respects, easier than sending finished goods. Thus, the chemicals to make bombs might not attract as much attention as the bomb itself. Bringing in large numbers of arms and ammunition at once was virtually impossible for the IRA due to the increasing diligence of British intelligence. The smugglers could only do so much. The same was likewise true for the purchasers in Britain; obtaining great numbers of arms would attract too much attention, not to mention the virtually insurmountable storage and shipping requirements.

There were only three answers to the ammunition problem for the Volunteers: smuggle more ammunition into the country, cannibalize ammunition they could not use to make new rounds, and manufacture ammunition. The smuggling option was already running at nearly full capacity but could not supply more than a trickle. The rebels cannibalized as much as they could, but there were other problems.

Cannibalization, as described in chapter 4, did not require much technical skill or specialized equipment. One needed the rounds for cannibalization, but the IRA had 43,773 rounds of ammunition for Morris tubes and “miniature rifles,” which were all unsuitable for combat. These rounds were easy to disassemble, and although each round would not have supplied sufficient materials to make a new .303 rifle round, for instance, several together would have. These rounds would have been valuable for their propellants, their primers, the lead in the bullets, the copper in the jacketing, and the brass of their cases. Of course, the IRA was already performing this type of operation with the .303 and some thirty-five hundred .45 (probably .45–70 rifle) rounds cut down for use as revolver rounds in Dublin.17 One cannot help but consider that the rural brigades were desperate for rifle ammunition, while the Dublin IRA was concerned about pistol ammunition. Such cannibalization would have only slightly increased the lamentably small amounts of ammunition available.

The only reasonable, long-term solution for the republicans was to manufacture their own ammunition. The problem was that Collins set the purchasing and production priorities for the directorates of Purchases, Chemicals, and Munitions. Purchases focused on arms, ammunition, and explosives. Gelignite came mostly from the Scottish Brigade after Joe Vise’s reorganization, although the British-based IRA and IRB supplied the large shipments of chemicals that O’Donovan’s directorate mixed into various explosive compounds, as well as the raw materials and tools that Munitions used in the factories. However, none of these operations actually focused on ammunition until Mulcahy ordered them to in March 1921. This was Collins’s failure.

Table 9.19. Miscellaneous Munitions Statistics

| 16 Aug. 1920–11 July 1921– | 11 July 1921 17 Dec. 1921 | |

|---|---|---|

| Explosives manufactured by IRA | 1,900 lbs. | 40,000 lbs. |

| Cash value of materials purchased | £10,000 | £30,000 |

| Number of consignments | 500 | 600 |

| Weight of consignments | 18 tons | 90 tons |

Source: “Army Goods Inwards and Outwards Book,” vols. 1–6, September 1920–July 1921, NAI DE.

Fairness demands that one understand the temporal and situational factors involved with arms supply. There simply was not enough time for the movement to develop the systems necessary for this part of the war effort. Developing mature organizations, systems, and processes takes time, and this was something the republicans did not have. Unlike the classic protracted war of exhaustion that was to become common in revolutionary guerrilla warfare, the Irish republicans were not capable of waiting forever to get the British to give into their demands. The republicans could have focused their efforts in different areas but did not have long to make decisions. Who was going to make these decisions, and by whom were they to be advised? They created an or-ganization virtually from nothing, without experience or doctrine to guide them and on an as-needed basis. That is why, for instance, the IRA and the Dáil defaulted to using the British army and parliament as examples to copy. Finally, one must also recognize that the old military saying “the enemy gets a vote” was equally valid in Ireland.

Attempts to Stem the Arms Trade

The situation the republicans were in at the start of the new conflict has been well documented, but those areas directly touching on the arms-procurement efforts are the actions of the security forces. Skill in the counter-arms-trafficking realm depended on many factors including, experience, political will, information, coordination and cooperation, authority under the law, and clarity. When any of these was lacking, success came mainly through happenstance.

The Intelligence Effort

It took considerable time to establish effectual intelligence in Ireland after the Great War. The British first needed a functioning intelligence structure capable of collecting information from many different types of sources and getting it to analysts who could bring it together to form a realistic view of what was happening. There had to be a link between the intelligence collectors and the analysts and from them to the decision-makers. This process or cycle had to occur in sufficient time to be useful.

The government and police needed accurate and timely intelligence. In practical terms, this meant police and military raiders needed to pass any information, documents, maps, and other items to a central location for immediate examination. This required a manned, functioning, intelligence-analysis center that could act as a central clearinghouse. This did not exist until Brig. Gen. Ormond Winter became the head of the police intelligence effort in Ireland in late 1920. The problem with Winter, as Peter Hart pointed out, was that the military intelligence officers felt his operation was too centralized to be useful; his organization created another layer through which they had to wade to get the information they needed.18 Thus, as is generally the case, the dissemination of the intelligence to the operational elements was a problem. Winter’s attempt to centralize intelligence production was ahead of its time and mirrors the common practice of “intelligence fusion” today. That it failed does not change the importance of what he was trying to accomplish. The failure was due to inexperience, lack of communication between police and military, technological limitations, and time. There was insufficient time to gain the experience, to build trust between the various security forces, and to create viable and mature intelligence organizations in the seven months before the truce.

British intelligence capabilities never reached the level they needed to be. Of all the rebel smuggling and procurement failures mentioned throughout this work, almost all failed due to rebel mistakes rather than proactive British measures. This also highlights the point that the rebels had the upper hand but not the experience in smuggling to exploit this opportunity. The great exception to this was the Hoboken Thompsons incident in July 1921. This was a British intelligence victory but not one from Dublin Castle, Special Branch, the police, Winter’s Raid Bureau, or the nascent intelligence organization in London. It was solely due to the initiative of Consul-General Gloster Armstrong in New York—in other words, an outsider to their normal intelligence structure. Likewise, it was the constabularies of Liverpool and Manchester that inflicted the most significant losses to the rebel arms trade through the arrests of November 1920.19

Antismuggling

Contrary to republican propaganda, the United Kingdom was a nation of laws; thus, the government’s actions had to have some basis in law to be defensible. Before the world war, this was precisely the problem with the Ulster Volunteers. Without laws prohibiting arms possession or importation, since the lord lieutenant lost his authority to prohibit arms in 1906, all the government had to fall back upon was a statute from the fourteenth century and the Gun Licensing Act of 1870, a revenue statute. The legal opinions of the attorneys-general that UVF actions constituted “levying war against the king” were irrelevant because the politics surrounding the attempts to pass home rule made it politically impossible for Dublin Castle to acknowledge any significant problem in Ulster officially.

In December 1913, the Asquith government finally got a royal proclamation prohibiting arms (see chapter 2), but in many respects it was either too soon or too late. For the former, there were no structures or mechanisms in place, other than individual policemen, to enforce it. Against individuals this was not an issue, but for groups the police were inadequate against the efforts of organized Volunteers, north and south. The ineffectual response to the UVF arms landings at Larne and Donaghadee in 1914 is prima facie evidence of this. Deputy Commissioner Harrel’s ham-handed actions at Howth in 1914 likewise demonstrate this point; his was an overreaction to the police failure at Larne, regardless of any other possible motives.20

One must also recognize this entire situation changed with the outbreak of war in August 1914. The Defence of the Realm Act made it considerably easier to deal with the threat of dissident arms smuggling. When this power came into their hands, policemen no longer needed it; the UVF was beginning to work with the government, while the National Volunteers supported the government. The minority Irish Volunteers were almost insignificant in the beginning. When the Irish Volunteers became a threat, they suffered the failure of Casement’s attempt and had to go to the Easter Rising with what they already had. Thus, DORA did not come into play, in a gunrunning sense, until 1918. During the War of Independence, DORA and the replacement ROIA of 1920 continued to empower authorities until virtually the end. The last arms prohibitions came in March 1921 and were based on the Firearms Act of 1920.21

The continually worsening situation in Ireland eventually led to proclamations of martial law in December 1920, a partial admission of failure by the politicians that civil government could no longer function. Martial law, in the counties where it was proclaimed, did little to help in this process. The problem with martial law was that it did not give complete authority to the military, nor did the cabinet want to do so, although the goal was to create unity in leadership.22 Martial law, however, still gave the military greater powers to hunt rebels and arms, while increasing penalties for various activities. ROIA outlawed possession of arms with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, while martial law could impose death. The greatest limiting factor was that not all counties were under martial law.23 In the end, the martial law policy was insufficient due to its lack of actual substance.

At the same time, there was the question of whose responsibility it was to interdict the arms smuggling. The Board of Customs and Excise repeatedly maintained this was a police function.24 By 1920, Customs increased its searches of cargo, passengers and their luggage, crew members, and vessels.25 In response to the lord lieutenant’s request, the commissioners sent a “special staff” of “experienced officers” to Ireland for this duty.

This group of eight men must have posed a considerable threat to IRA smuggling since, within two weeks of their arrival, each man signed a petition to the commissioners of the Customs and Excise to be relieved of duty in Dublin and Kingstown and returned to London. The reasons they gave were sound. In the previous ten days, they had witnessed a gunfight in the Kingstown parcels office, the IRA had threatened to kill them once they made their first arms seizure, and they “were not informed and had no idea of the real conditions prevailing” in Ireland.26

How searches progressed depended entirely on who conducted them. With a large ocean liner, any search, to be of any use, required time and manpower. If the ship landed at Liverpool, the Customs and Excise officials, along with the Liverpool Constabulary, conducted the searches. These searches had to be conducted in strict accord with the law because the ROIA did not apply to Britain. The duty of searching inbound shipping was in the hands of the Customs officials and of the DMP and the local RIC in other ports. By early 1921, the smuggling situation was sufficiently critical that the Auxiliary Division of the RIC formed a new company in late March specifically to assist in searching ships in Dublin.

The Q Company Auxiliaries, based at the London and North Western Railway Hotel at the North Wall in Dublin, were entirely different from other Auxies. Of the only twenty-five sergeants and men in the company, all had experience at sea. The reason for this was their experience on civilian ships made them perfect for searching them.27 The effectiveness and operations of Q Company has not been examined.

While the available records are incomplete, they still permit a view into the world of the republican and, specifically, the QMG struggles to arm the IRA. The assessment of these struggles is varied. The record indicates considerable efforts at every level, in each aspect of these activities. There was little “slackness or neglect” on the part of the QMG or any of the republicans working to arm the IRA from outside the brigades.28 One must conclude, however, based on the data presented here, that these efforts were insufficient for the task.