THE EXISTENCE-TISSUE is made of hunger. It rustles. It is alive, forever moving and changing. It wants to recognize itself, wants to celebrate and explain itself, to understand the bottomless depths contained in the surfaces of appearance. And in its hunger, it evolved language and thought. In the modern West, linguistic thought is experienced in a mimetic sense, as a stable and changeless medium by which a transcendental soul represents objective reality. This sense of language assumes language did not evolve out of natural process, but that language is instead a kind of transcendental realm that somehow came into existence independently of natural process. In ancient Greece this was associated with the advent of writing, which was just beginning to reshape consciousness, creating a seemingly changeless interior realm of the soul. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, it was part and parcel with a god-created soul: Adam was created by God as a soul already endowed with language, presumably the language of God, since they spoke from the beginning and of course God created the universe by speaking commands, and so language was a transcendental medium that predates the appearance of humans as physical beings on earth. That god may be gone now; but when language functions in that mimetic sense, it still embodies an absolute separation between mind (soul) and reality, and that separation defines the most fundamental level of experience.

The history of language in China reveals that language was not experienced as a mimetic separation by the ancients, by Stone-Waves or Inkstone-Wander gazing out across ridgelines in the painting. They recognized language as an organic system evolved by the existence-tissue, as the existence-tissue describing and explaining itself. In the cultural myth, language begins in China with the hexagrams of the I Ching, such as the first two, Heaven and Earth:

These hexagrams embody the two fundamental elements of the Cosmos: yin and yang, female and male, whose dynamic interaction produces the cosmological process of change. The solid lines are yang, the broken lines yin, and the I Ching’s sixty-four hexagrams include every possible combination of yin and yang. A language is at bottom a description of reality, and the hexagrams describe the basic configurations of change, so they are a proto-language, the first stage in existence’s urge to recognize and describe itself. Indeed, in the cultural myth, they were created by the first man: Root-Breath, who emerged from Bright-Prosperity Mountain and was in fact half dragon, half human. That is, they grew out of earth and natural process.

The hexagrams did not attempt to describe the particulars of reality, but to embody the deeper forces and processes of reality. This engendered a similar assumption about the Chinese language which, according to cultural legend, appeared after the hexagrams. Rather than referring mimetically to things in the world (an assumption that sees reality primarily as noun, as permanence), classical Chinese words embody the configurations of change (thereby seeing reality primarily as verb, as transformation). A word did not so much refer to a thing as share that thing’s embryonic nature. That is, in the ongoing transformation of things, words emerge in the same way that the ten thousand things emerge, and from the same origins. And so, rather than alphabetic marks that are distant and arbitrary signs referring to reality from outside, ancient China’s artist-intellectuals ideally experienced words without the dualistic divide between empirical reality and language/consciousness as a kind of transcendental realm.

They sometimes felt that separation, though never as a fundamental metaphysical breech as in the West, and overcoming it is what spiritual practice was largely about. In their spiritual and artistic use of written language, in poetry and calligraphy, they experienced language as a return to origins, as the existence-tissue speaking through us, describing and understanding itself through us, decorating itself with meaning. Here we encounter the tantalizing fact that to translate a Chinese poem into English is to fundamentally misrepresent it, because the mimetic function of English, with its distancing, is exactly what a Chinese poem is meant to undo.

The Chinese language itself encourages this experience of origins, perhaps most obviously in its pictographic nature; wherein words are in fact images of things, and so share with things their origins and essential natures. In this, the language keeps alive its origins in primal image-making, like petroglyphs. We tend to look at primal art like petroglyphs and cave art through our own cultural lens, with its dualistic assumptions in which we are transcendental souls radically separate from the world around us. We assume that in chiseling animal figures into rock, artists were rendering objects outside of themselves in the world, much like an artist today would render something like an antelope. But primitive artists were largely free of those assumptions, because they were operating here in the beginning, where consciousness and existence are still a single tissue. When they etched an antelope in rock, there were no boundaries between self and antelope, self and rock. Instead, they were acting at the origin-place where antelope and image share their source, where they were bringing that antelope into existence here in the beginning, creating the way the Cosmos creates. That could only be described as a spiritual experience, a spiritual practice: the existence-tissue creating itself, decorating itself, caressing itself, celebrating itself. And again, as a matter of actual immediate experience, that is how words still work for us in our everyday lives.

This body of nondualistic assumptions remained alive in the Chinese language with its ideograms1 that in their earlier forms often look remarkably like petroglyphs. In this, ideograms maintained their nature as visual art where an imaged thing is experienced as both noun and verb simultaneously, as alive. And at the same time, it is experienced non-mimetically. These distinctive characteristics of the language are emphasized and exaggerated in poetry, and they function as the essence of poetry as a spiritual practice. In this sense, Chinese poetry can be thought of as returning the experience of language and its ideograms to their sources, which feels very close to petroglyphs that exist prior to the separation of consciousness and landscape/Cosmos.

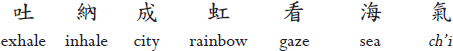

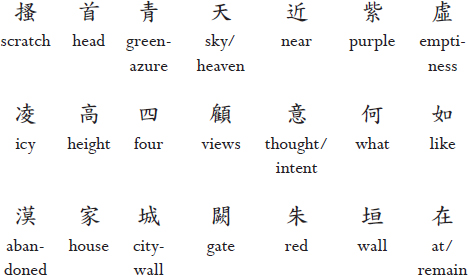

Equally profound is the way classical Chinese leaves out subjects and most other grammatical material, a characteristic that poetry exploits dramatically. In the poem inscribed on Stone-Waves’ painting, for instance, that grammatical minimalism renders Inkstone-Wander on the mountaintop not as a transcendental soul undergoing experiences, as a Western poem would, but as the existence-tissue experiencing itself:

In reading such a text, we conjure a subject from empty grammatical space, though it remains much more a nebulous presence than the clear definition that a pronoun produces. Here, the absent subject resides in the empty space preceding scratch. We read it first as I, because the convention for lyric poems like this is that they are about the poet’s immediate experience. But there are other possibilities for the missing pronoun: you or he/she, or the more universal we or one. The poetic language refuses to choose between those possibilities, and so describes the situation as a universalized human experience, or as the experience of human consciousness in general. And because we initially read the line with a first person I, that ambiguity enlarges self-identity into this general sense of shared consciousness that includes Stone-Waves and us, which reinforces the sense that we are meant to identify with the gazer in the painting.

So, reading I in this enlarged sense of consciousness, the first line is read provisionally: [I] scratch my head in wonder at green-azure heaven so close to purple emptiness. Here, consciousness appears as an absent presence, an empty grammatical space that only implies the presence of consciousness. But in poems like this with seven ideograms per line, there is always a grammatical pause after the fourth ideogram, and that presents a second possible reading: Scratching my head in wonder at green-azure heaven, [I] am close to purple emptiness. Because the line offers no grounds for choosing between these two readings, it begins to suggest a sense of consciousness as an absent presence distributed throughout the line, more and more indistinguishable from the green-azure heaven and purple emptiness we see in the painting. And remarkably, this sense is encouraged by the line’s grammatical minimalism, for the line could be read without pronouns, thereby conjuring a complete integration of consciousness and landscape: Green-azure heaven scratches its head in wonder this close to purple emptiness.

This reading is suggested by the philosophical resonance of 天. Although its primary meaning here is simply “sky,” 天 also means “heaven,” which is a central philosophical concept with a long history. For a time in early China, 天 was an impersonal deity that created and controlled all aspects of the Cosmos, but this concept was secularized and came to mean essentially “natural process,” thereby investing existence with the aura of the sacred. That concept informs the reading of this line, for the I has become “heaven” scratching its head. And so, Inkstone-Wander is returned to his place as an integral part of heaven, or the existence-tissue.

The poem’s fifth line produces a similar effect, for Inkstone-Wander again appears as an absent presence in the grammatical pause after the fourth ideogram:

This suggests the most straightforward reading of the line: As a rainbow breathes in and out of view over the city, [I] gaze into sea-mist. But in the most grammatically direct reading, it’s the rainbow that is looking. This ambiguity creates a weave of consciousness and landscape, encouraged by the description of the rainbow as inhaling and exhaling, and the fact that early legend considered the rainbow to be a rain-dragon: A rainbow breathing in and out of view over the city, [I] gaze into sea-mist, a reading that identifies the I with dragon, embodiment of cosmological change and transformation.

Even though much encourages us to fill in the poem’s empty grammatical space with personal pronouns, the poem does not definitively even specify this as a human experience. With its grammatical space emptied of restrictive pronouns, the Chinese does not separate a center of identity out from the tissue of existence, and it certainly does not create a transcendental soul as English does. Instead, all of these empty grammatical spaces might more accurately be filled in with something like existence-tissue (in human form). The 意 (intentionality/intelligence/desire) in line 2 reinforces this reading, for as we have seen, the “thoughts” could as well be the landscape’s “thoughts” as Inkstone-Wander’s or Stone-Waves’. And all along, because of the first-person presumption, the poem as spiritual practice returns Inkstone-Wander/us to his/our place as an integral part of the existence-tissue. This establishes the texture of the entire poem, defining it not as the experience of a transcendental soul as we would assume in the West, but of consciousness indistinguishable from the existence-tissue here in the beginning:

1. This term is used in its common sense, where it simply refers to Chinese written words while emphasizing their distinctive graphic form.