Proverbs

by Tremper Longman III

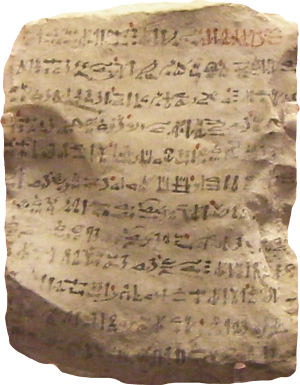

Egyptian scribes

Z. Radovan/www.BiblePlaces.com

Introduction

Proverbs is an anthology of wisdom sayings. While the main superscription associates the book with Solomon (1:1), elsewhere we find contributions by anonymous wise men (22:17), Agur (30:1), King Lemuel’s mother (31:1), and the men of Hezekiah (25:1). But it is Solomon who is featured (see also in 10:1; 25:1).

Solomon’s reign is described in Kings and Chronicles. These are years of unprecedented success and prosperity for Israel. Solomon inherited a united kingdom won by the wars of his father, David. The beginning of his reign was peaceful, with no significant internal or external enemies. Such a time was right for productive and positive international contact, including that between wisdom teachers.

Sumerian Proverbs from Nippur

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

The historical books describe Solomon’s wisdom as having a divine origin. In response to the king’s piety (1 Kings 3:1–15), God allowed him to choose a gift. Rather than wealth or honor, Solomon asked him for wisdom, and God granted it to him. Indeed, God was so pleased with his choice that he also gave him honor and wealth. The narrative that follows tells stories about the exercise of this divinely-granted wisdom (4:16–28).

It is notable that Solomon’s wisdom is frequently set in an international context. While the queen of Sheba’s visit is an event that illustrates Solomon’s international reputation (10:1–13), that reputation is described more fully in 4:29–32, 34:

God gave Solomon wisdom and very great insight, and a breadth of understanding as measureless as the sand on the seashore. Solomon’s wisdom was greater than the wisdom of all the men of the East, and greater than all the wisdom of Egypt. He was wiser than any other man, including Ethan the Ezrahite—wiser than Heman, Calcol and Darda, the sons of Mahol. And his fame spread to all the surrounding nations…. Men of all nations came to listen to Solomon’s wisdom, sent by all the kings of the world, who had heard of his wisdom.

What is significant about this description is that Solomon’s wisdom, though clearly superior, is evaluated in the light of international wisdom. In order for it to be truly complimentary, the passage must intend to grant honor also to wisdom found from outside of Israel. One could not imagine complimenting an Israelite prophet or priest by granting value to pagan religion.

On an important level, then, we observe in the historical texts an international context to wisdom. Once realized, it is not as much of a shock to see just how much of Israelite wisdom is shared with Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Aramaic wisdom texts.

Before continuing with this line of inquiry, however, it is important to make a caveat to this statement. The book of Proverbs offers its wisdom in a context that clearly gives all the glory to Yahweh, the God of Israel. In the first place, the prologue makes it clear that “the fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge.” Then there is the picture of Woman Wisdom, the one with whom the father urges the son to grow intimate. This woman stands for Yahweh’s wisdom and ultimately for Yahweh himself, while her counterpart, Woman Folly, represents the pagan deities that the Egyptians, Mesopotamians, and Aramaeans worshiped. Thus, even though we have good reason to think that the Israelite sages knew and learned from the wisdom of the broader ancient Near East, they would likely conclude that it was not so much that they were wise as they stumbled across the truth as they observed the rhythms of how the true God’s world worked.

In any case, as we will see from the following pages, the wisdom found in Proverbs is often discovered elsewhere in ancient Near Eastern wisdom. The modern comparative study of Proverbs began in earnest with the publication of the Instruction of Amenemope. The text had been known since the latter part of the nineteenth century, but it was not translated until 1923. But once published, similarities with the book of Proverbs, particularly with the “words of the wise” (22:17–24:22), became obvious and widely discussed. Up to recent times, the debate has not centered on whether there are similarities, but the direction of influence—some saying the Israelites used the Egyptian source and others taking the opposite view. The issue is relatively unimportant, though now most are convinced that the Egyptian predates the Israelite.

In any case, it is now clear that even if there is something of a special relationship between Proverbs and Amenemope, other ancient Near Eastern texts share many of the same values and principles as Proverbs and Amenemope. This is true not just of other Egyptian texts but also of Mesopotamian and especially Aramaic texts.

This is not to deny that there are also differences between the values expressed by the Bible and those by the surrounding wisdom literature. Here are a few examples of passages that give advice or observations that would not be found in Proverbs:

Woman is a pitfall—a pitfall, a hole, a ditch,

Woman is a sharp iron dagger that cuts a man’s throat. (Dialogue of Pessimism)1

Do not open your heart to your wife; what you have said to her goes into the street.2

But an offspring can make trouble:

If he strays, neglects your counsel.

Punish him for all his talk …

His guilt was fated from the womb. (Instructions of Ptahhotep)3

Apart from numerous points of detail, the fundamental difference between biblical and ancient Near Eastern wisdom is the ultimate motivation for behaving in a wise manner, namely, fear of Yahweh, the true God.

Proverbs were among the earliest forms of literature. This ancient Sumerian proverb says: “To speak, to speak is what humankind has most on heart.”

University of Pennsylvania Museum

The details and specific points will be illustrated in the notes that follow. For the remainder of this introduction we will provide descriptions of the main examples of ancient Near Eastern wisdom texts.

Egyptian Wisdom

Since the publication of Amenemope, Egyptian wisdom has occupied pride of place in the comparative study of Proverbs. The main genre of wisdom, and the one closest to the biblical book, is called in Egyptian sby3t, a word often translated “instruction.” These texts appear as early as the Old Kingdom (2715–2170 B.C.) and down to the latest periods of Egyptian history. The following examples are the ones cited in the following notes.

Kagemni. Though brief, the significance of the Instruction of Kagemni is that it is one of the oldest examples of the genre, most likely coming from the Fifth or Sixth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom Period.4 Kagemni was the recipient of these instructions that emphasize proper behavior in the area of speech and table etiquette. At the end of the text, it is mentioned that Kagemni becomes a vizier during the reign of King Sneferu.

Ptahhotep. Ptahhotep is a much longer, but still early example of the genre. Ptahhotep is said to be vizier under King Izezi of the Fifth Dynasty, but Egyptologists judge that it is more likely to be a product of the Sixth Dynasty. Its thirty-seven maxims promote the ideal of a quiet, contented man of humility over against a heated, anxious, striving man. The composition begins with a prologue that names Ptahhotep as the speaker and his son as the recipient, with the purpose being to instruct “the ignorant in knowledge and in the standard of excellent discourse, as profit for him who will hear, as woe to him who would neglect them.”5

Wisdom of Amenemhet

Caryn Reeder, courtesy of the British Museum

Merikare. Coming from late in the First Intermediate Period (Ninth or Tenth Dynasty), Merikare is the first example of a royal instruction. The speaker is not named in the extant text, and Merikare is the recipient. The assumption is that he is addressed by his predecessor, perhaps Achthoes III, but the suspicion is that that would be a fiction and that the text may have been produced by those under Merikare’s influence. In other words, the text may have been produced to provide propaganda supporting Merikare’s preferred agenda.

Instruction of Amennakht: “You are a man who listens to a speech to separate good from bad—attend and hear my speech! Do not neglect what I say!”

Lenka Peacock, courtesy of the British Museum

Any. Any was a mid-level bureaucrat in the court of Queen Nefertari, the wife of Ahmose, one of the early New Kingdom pharaohs (Eighteenth Dynasty). It treats a variety of topics, many of which are similar to those found in Proverbs, such as promiscuous women, honesty in commerce, silence, overindulgence, and generosity. The text ends with a unique epilogue, recording that Any’s son at first rejects his father’s counsel, but after his father confronts him, he ultimately accepts his teaching.

Amenemope. Amenemope is the instruction text most often compared to Proverbs, and indeed it shares many themes and even some more specific parallels (as will be pointed out below). The original exemplar of this composition is likely from somewhere between the tenth and sixth centuries B.C. Other partial copies of this popular composition are now known, none clearly older. Even so, most scholars today would date the writing of the text to the twelfth century B.C.6

The speaker is Amenemope, who is named “Overseer of Grains,” a mid-level government official, and he is addressing his remarks to his son, Hor-em-maa-kheru. After a lengthy prologue that gives the purpose of the composition, the advice section is divided into thirty chapters.

Ankhsheshonqy. This text is written in Demotic, the late cursive form of Egyptian, and is dated to the first century B.C., but there are reasons to believe it comes from the Ptolemaic period a century or two earlier.

The prologue introduces the unique setting for Ankhsheshonqy’s advice to his son. He is writing from prison, where the pharaoh sent him for not revealing a thwarted plot against his life. The style of his advice is formulated in short prose statements rather than the longer maxims of earlier instructions. Sometimes the short maxims are bundled together by topic, but there is still a rather random kind of structure. The theme may be described as “the ubiquity of change and the vicissitudes that go with it, and the fact that actions have consequences.”7

Papyrus Insinger. The last text of our survey is known from a papyrus from the first century A.D., though again the composition is likely Ptolemaic. Like Ankhsheshonqy, these texts are single line prose sentences, but unlike the earlier text, there is a definite thematic arrangement complete with headings.

Mesopotamian Wisdom

Mesopotamian wisdom is among the earliest literary writing in Sumerian. The Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians do not have much by way of material that is comparable to Proverbs. The following sampling discusses three texts that are most obviously comparable to the biblical book of Proverbs.

Sumerian proverbs. Recent study has shown that Sumerian proverb collections go back to the Early Dynastic period III (2600–2550 B.C.E.) and that they continued in use, being cited in the Sumerian language in Akkadian literature even after Sumerian was no longer a spoken language. Most of the texts come from the Old Babylonian period. These texts were translated into Akkadian and were found in Ashurbanipal’s library in the seventh century. The major topics of concern were “a woman’s daily routine, family relationships, the good man, the liar, legal proceedings, Fate, the palace, the temple and their gods, as well as historical and ethnic allusions.”8

Instruction of Shuruppak, Sumerian Proverbs from the 3rd millennium

Kim Walton

The Instruction of Shuruppak and the Counsels of Wisdom. Sumerian also attests an instruction similar to the Egyptian “instructions” described above, as well as Proverbs 1–9. The Instruction of Shuruppak is named after the father of the famous sage, Ziusudra, who survived the flood. We know this text primarily through what Alster calls the “standard version,” dated to 1900–1800 B.C., but it goes back to the Early Dynastic period (specifically the twenty-sixth century B.C.).9 There are some later Akkadian translations of this Sumerian work.

The text contains the instructions of Shuruppak to his son Ziusudra, and it addresses many of the subjects of wisdom instructions from other Near Eastern cultures, including Proverbs. Akkadian also attests a version of this composition as well as another text where a father teaches a son the Counsels of Wisdom.

Aramaic Wisdom

The proverbs of Ahiqar. Written in Aramaic, the story is set in the neo-Assyrian period. Ahiqar is a wise man to King Sennacherib. He is betrayed by his nephew, Nadin, whom he raised, and the latter turned the king against Ahiqar. The king sends one of his military henchmen to kill Ahiqar, but since the wise man had given the man earlier advice that saved his life, they plan a ruse. They take a beggar and burn him beyond recognition and pass him off as Ahiqar. Ahiqar goes into hiding.

Time passes and the Egyptians bring a problem to Sennacherib, who then wishes his old wise man was around to deal with the issue. The henchman considers this an opportune time to tell the king about the ruse, and Ahiqar is restored to the king’s good graces. Ahiqar then beats Nadin, and the instructions that follow this narrative constitute the lengthy didactic portion of the composition.

Education and Sages in the Ancient Near East10

The book of Proverbs is a book of instruction. A father teaches his son to follow in the way of wisdom and to avoid the way of folly. The metaphoric description of Woman Wisdom is that of a teacher as well. She desires to instruct her hearers in the way that leads to life.

The invention of writing was attributed to Thoth, god of learning and wisdom and patron of scribes, seen here in his baboon aspect. A scribe with an open papyrus roll on his lap is in attendance.

Werner Forman Archive/The Egyptian Museum, Berlin

The didactic nature of Proverbs and particularly its description of the wisdom teacher or sage raise the question of the status of the sage and education in ancient Israel. This question can only be approached in the context of the broader ancient Near East.

Statue of the scribe Amenhotep, minister during the reign of Amenhotep III

Werner Forman Archive/The Egyptian Museum, Cairo

The clearest evidence for education and the role of the sage comes from Mesopotamia, where we have educational tablets and literary compositions that talk about the life and formation of a young scribe. Indeed, the school has a name, the E-DUB-BA-(A), which means “house [or] room of the tablet.” Daniel was subjected to a Babylonian education while in exile in the court of Nebuchadnezzar, where he learned “the language and literature of the Babylonians” (Dan. 1:4). Egypt too had an long and distinguished tradition of education and the role of the sage in society. The Aramaic text of the Proverbs of Ahiqar illustrates what is found elsewhere: scribes under the employ of the royal court.

The picture is not so clear in ancient Israel, and scholars debate whether there were ancient schools and whether the sage was a professional designation. That there was some form of education is clear; the question is whether the schools were institutions connected to the court or the temple, or whether education took place in the context of the family. After all, there is no mention of schools until the intertestamental period when the Bet Midrash (“house of instruction”) is mentioned in Sirach (Sir. 51:23). But it has also been pointed out that educational type texts (so-called abecedaries) have been recovered that should be dated to the latter part of the monarchy.

No one doubts that writing was taught; the question is in what kind of context. That the sage was a professional designation seems clear from its use in the historical books (the roles of royal advisors like Jonadab [2 Sam. 13], Hushai, and Ahitophel [2 Sam. 15–17]) as well as the prophets (Jer. 18:18), but this does not mean that it is always used in such a way.

The instructions found in Proverbs have a diverse background: court, family, scribal, and perhaps even religious. For now the question of the social place of the use of Proverbs will have to remain an open-ended question, though the ancient tradition of schools in Mesopotamia and Egypt may invite speculation.