CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 3

Euthanasia

In 1975 twenty-one-year-old Karen Ann Quinlan went into a coma after having a few drinks at a party. Apparently, she had eaten very little in the days before the party and had also taken some drugs—perhaps tranquilizers. She was rushed to the hospital, where doctors connected her to a respirator. Unfortunately, by this time the lack of oxygen had caused permanent brain damage. Her parents, convinced that Karen would not have wanted to be kept alive by artificial means, asked the hospital to disconnect her from the respirator machine. The hospital refused.

The resulting controversy and court battles brought the issue of euthanasia to the public’s attention. The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that Karen Quinlan’s right to privacy had been violated by the hospital. As a result, she was removed from the machine and moved to a nursing home to die in peace. The Terri Schiavo case was followed by a shift in favor of euthanasia, going from 53 percent in favor of legalizing euthanasia in 1973 to 70 percent in 2013.1

WHAT IS EUTHANASIA?

The term euthanasia comes from the Greek eu and thanatos meaning “good death.” Euthanasia has come to mean painlessly bringing about the death of a person who is suffering from a terminal or incurable disease or condition.

Although physicians in the United States are permitted to withhold treatment for a dying patient, the law prohibits active euthanasia. This position is consistent with both that of the American Medical Association (AMA) and the British Medical Society. The AMA states:

For humane reasons, with informed consent, a physician may do what is medically necessary to alleviate severe pain, or cease or omit treatment to permit a terminally ill patient to die when death is imminent…. Even if death is not imminent but a patient is beyond doubt permanently unconscious … it is not unethical to discontinue all means of life-prolonging medical treatment … [which] includes medication and artificially or technologically supplied respiration, nutrition or hydration.

— AMA Council on Scientific Affairs and Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (1990)

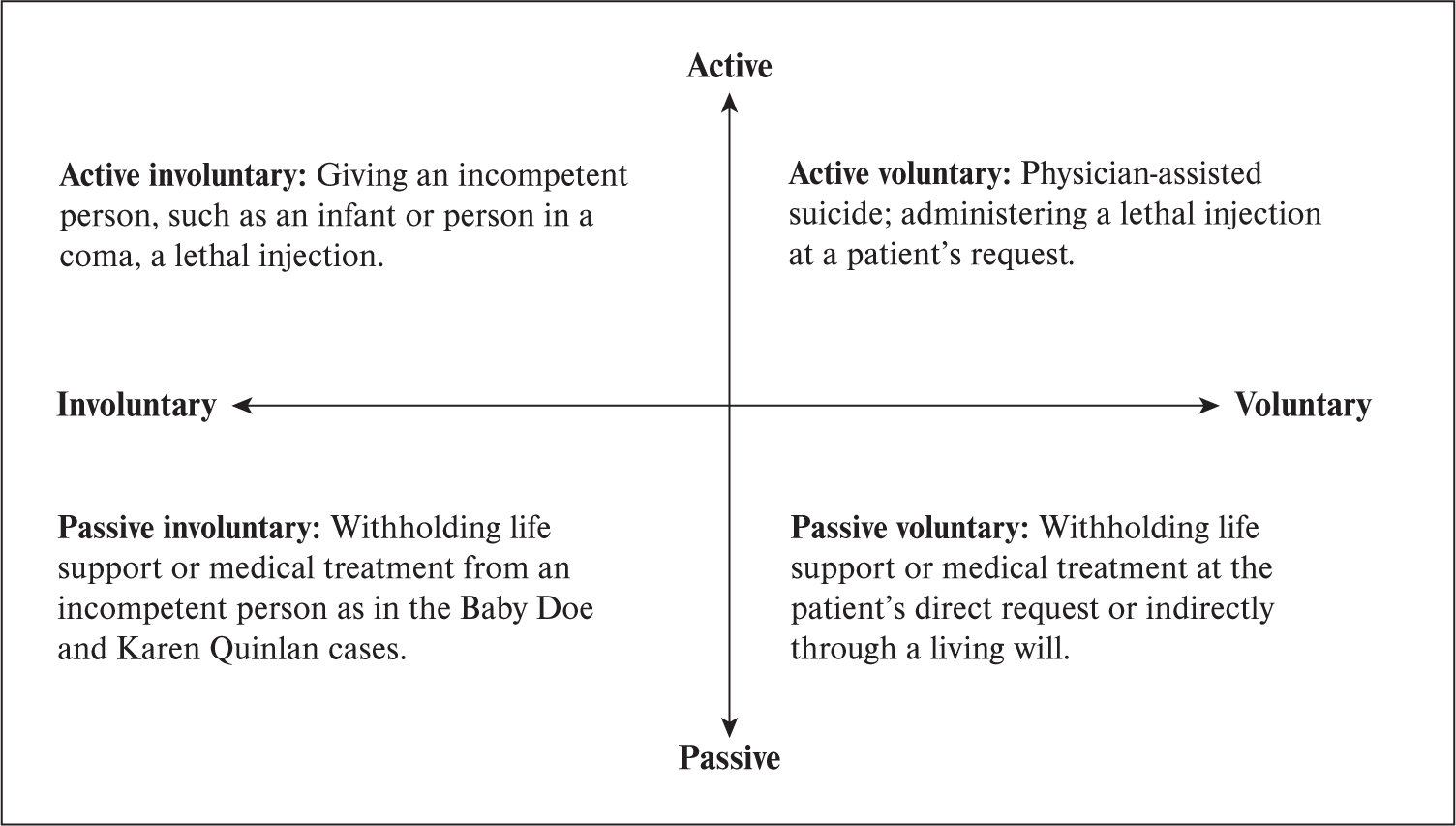

Voluntary euthanasia requires that the patient be competent—that is, rational and able to make his or her own health care decisions. The distinction between passive and active euthanasia is less straightforward since it often depends on the intention of the person carrying out the action.

Active euthanasia involves taking an action, such as giving a lethal injection, to bring about the patient’s death, while passive euthanasia entails withholding life support or treatment. Some argue that passive euthanasia is not strictly euthanasia since it does not involve intentional killing; rather, it is an effort to spare a person “additional and unjustified suffering” by withholding further treatment. In this chapter we will primarily consider the morality of active euthanasia.

THE PHILOSOPHERS ON EUTHANASIA

The contemporary philosophical debate on euthanasia has been influenced primarily by ancient Greek and Judeo-Christian views on death. Greek physicians regarded health as a human ideal par excellence. Because human worth and social usefulness depended on one’s state of health, chronically sick people were expendable. Plato favored euthanasia of deformed and sickly infants because they would be a burden on the polis. The early Stoics taught that humans ought to quit life nobly when they are no longer socially useful.

Not all Greek philosophers agreed with the Stoics. Aristotle believed that willful euthanasia was wrong. Virtue, he argued, requires that we face death bravely rather than take the cowardly way out by quitting life in the face of pain and suffering. The Pythagoreans, who wrote the Hippocratic oath, also opposed euthanasia on the grounds that we are the possessions of the gods. To kill ourselves is to sin against the gods:

Never will I give a deadly drug, not even if I am asked for one, nor will I give any advice tending in that direction.

—Hippocratic Oath

The theme that humans are owned by God is found in Hebrew scriptures (Gen. 2:2–27). As creations of God, no human has the right to destroy his or her life or wantonly take the life of another. This understanding of human life as inherently precious and belonging to God has been immensely influential on the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic views on euthanasia. In the Jewish 111tradition, death should never be hastened; physicians who kill patients, even if their intention is to relieve pain and suffering, are considered murderers. According to the Islamic religion, illness and suffering are part of God’s will. Taking a life interferes with God’s will.

In Buddhist philosophy self-willed death, even in cases of suffering and pain, violates the principle of the sanctity of life. It is also wrong because (1) suffering is a means to work out bad karma and (2) a person who assists in suicide or euthanasia will be negatively affected by that participation. Hinduism also teaches that suffering should be endured. Those who deliberately shorten their lives will carry their negative karma into a later life. The Dalai Lama teaches:

Your suffering is due to your own karma, and you have to bear the fruit of that karma anyway in this life or another, unless you can find some way of purifying it. In that case, it is considered to be better to experience the karma in this life of a human where you have more abilities to bear it in a better way, than, for example, an animal who is helpless and can suffer even more because of that.2

Thomas Aquinas incorporated the Aristotelian and biblical prohibition against euthanasia and suicide into his natural law theory, arguing that suicide is unnatural and immoral for three reasons:

First, everything naturally loves itself, the result being that everything naturally keeps itself in being…. Secondly, because every part, as such, belongs to the whole … and so, as such, he belongs to the community. Hence by killing himself he injures the community as the Philosopher [Aristotle] declares. Thirdly, because life is God’s gift to man, and is subject to His power, Who kills and makes to live. Hence whoever takes his own life sins against God…. For it belongs to God alone to pronounce sentence of death and life.3

Using the model of Jesus on the cross, Christians emphasize the redemptive aspect of suffering. John Locke regarded self-killing as cowardly, contrary to nature, and opposed to the commandments of God. His view is echoed in the modern Protestant prohibition of active euthanasia, although most Protestants agree that it is morally acceptable to withhold or discontinue treatment that is merely prolonging the dying process. One exception to this was David Hume who, in his 1783 essay “On Suicide,” argued that suicide may sometimes be part of our duty to society. (To read his essay in full, go to http://

Immanuel Kant regarded suicide and voluntary euthanasia as immoral. Suicide does not fulfill the requirements of the categorical imperative because it involves a contradiction—that of exercising our autonomy to destroy our autonomy by destroying ourselves. People who want to end their lives also show a lack of respect for themselves by viewing their lives as a means only rather than an end. The prohibition of euthanasia remained pretty much unchallenged right up to the end of the nineteenth century.

THE CONTEMPORARY DEBATE OVER EUTHANASIA

It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that the public began questioning the prohibition of euthanasia. Public debate over euthanasia turned to horror when it was learned that in Nazi Germany up to a hundred thousand mentally ill and disabled children and adults “considered incurable according to the best available human judgment” were, to use official language, “granted a mercy death.”4 The memory of this terrible event still haunts Germany, which now prohibits euthanasia.

The public debate over euthanasia resumed with the development of new life—sustaining technologies such as the mechanical respirator. In 1957, troubled by the ethical problems 112involved in resuscitating unconscious individuals, the International Congress of Anesthesiology sought moral guidance from Pope Pius XII. The pope responded that physicians should not act without the consent of the family. Physicians also have a moral duty to use ordinary, but not “extraordinary,” measures to prolong life. The pope’s position was supported by the Catholic Church’s “principle of double effect.”

The principle of double effect states that if an act has two effects, one intended (in this case to end pain and suffering) and the other unintended (the death of the patient), terminating treatment may be morally permissible if it is the only way to bring about the intended effect. This distinction between passive euthanasia and active euthanasia has remained unchallenged for years.

Public opinion began shifting in favor of legalized euthanasia in the early 1970s following the death of Karen Ann Quinlan. The debate gained momentum with the 2005 Terri Schiavo case. Terri Schiavo had suffered irreversible brain damage and had been in a persistent vegetative state since 1990. Her husband requested that the feeding tube be removed. Her parents disagreed with the decision. The courts repeatedly rejected the parents’ request to make the hospital reinsert the feeding tube that kept their daughter alive.

While the majority of Americans approve of legalizing euthanasia, support for legalizing it tends to be higher in other Western countries. Support for euthanasia is especially high in France and in the Netherlands, where active voluntary euthanasia has been legal for several years.

Support for euthanasia of incurably ill people is also high in China. However, despite pressure from some groups to legalize it, euthanasia remains illegal in China. Although Japanese views on euthanasia have been influenced by the Buddhist repugnance of killing, the influence of the Shinto religion’s glorification of self-willed death for the benefit of the country has led to a more permissive attitude toward euthanasia than in other Buddhist countries.

Muslims are also opposed to euthanasia. The Qur’an states, “Do not take life, which Allah made sacred, other than in the course of justice” (Qur’an 17:33) and “And no person can ever die except by Allah’s leave and at an appointed term” (Qur’an 3:145).

Judaism and Roman Catholicism, as well as some other Christian denominations, also prohibits euthanasia.

EUTHANASIA LEGISLATION

Active euthanasia is illegal in the United States although Oregon, Washington, Vermont, Colorado, and Montana permit physician-assisted suicide under certain circumstances. The 1976 California Natural Death Act was the first law in the United States to address the issue of decision making on the behalf of incompetent individuals. The act allows adults, under certain circumstances, to make decisions in advance about the kind of treatment they would receive at the end of their lives.

Most people, including two-thirds of Americans, do not have a living will. Thus, it is not surprising that many terminally ill patients end up being kept alive despite their apparent wishes or despite family requests to terminate treatment.5

In the 1990 landmark case Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that every competent individual has a constitutional liberty right to be free of unwanted medical treatment if there is “clear and convincing evidence” of the patient’s desire to have the medical treatment withdrawn. The Court left it up to the states to decide for incompetent individuals. (See pages 115–116 for excerpts from the case. See also Case Study 1: Nancy Cruzan: Seven Years in a Persistent Vegetative State.)

In 1994 the citizens of Oregon approved Ballot Measure 16 (the “Oregon Death with Dignity Act”), which legalized euthanasia under certain conditions. The Oregon Death with 113Dignity Act took effect in 1997 following a lengthy court appeal process. Since then, more than 1,000 people—mostly cancer patients and people over the age of 70 have chosen to end their lives.6 The conditions of the law, which requires that

- patients must be in their final six months of terminal illness;

- patients must make two oral requests and one written request to die, separated by a two-week period;

- patients must be mentally competent to make a decision; and

- two doctors must confirm the diagnosis.

Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act was challenged in 2002 by U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft, who charged that prescribing barbiturates to induce death is illegal under the Controlled Substances Act. The U.S. District Court ruled in favor of Ashcroft v. Oregon. The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and in 2006, the Court in Gonzales v. Oregon ruled in favor of Oregon, stating that the Controlled Substances Act does not give the attorney general the power to prevent physicians from prescribing controlled substances to patients for the purpose of euthanasia, if it is permitted by the law of the state.

While assisted suicide is legal in only a handful of states in the United States, it is legal in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Thailand, and Belgium and is tolerated in several other countries. Although the law in the Netherlands permits euthanasia only for medically classified physical or mental diseases and afflictions, many people are critical of this law on the grounds that it has too much potential for abuse. Indeed, active euthanasia is involved in an estimated 4.5 percent of deaths in the Netherlands.7 Unlike the Oregon law, physicians in the Netherlands are not required to determine whether the patient is of “sound mind” or competent to make such a decision. A Dutch study found that at least 50 percent of these patients were suffering from serious depression or dementia when they requested euthanasia.8 Children who are “hopelessly ill” or handicapped are also the target of euthanasia in the Netherlands, leading to the charge that the Dutch have already started down the slippery slope to involuntary euthanasia.

PHYSICIAN-ASSISTED SUICIDE

Americans are split over whether physician-assisted suicide—a type of active euthanasia in which a physician assists the patient in bringing about his or her death—should be legal. Because of laws in most states against euthanasia, most physicians who help patients die do not go public. One notable exception was Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who saw himself as a defender of liberty. In 1990 Kevorkian helped Janet Adkins, an Oregon woman who was suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, to end her life. The vision of Adkins lying dead on the crisp white sheets in the back of Kevorkian’s rusting ’68 Volkswagen van has become permanently etched onto the American psyche. Since 1990, Kevorkian presided over the deaths of more than 130 people. In April 1999 a Michigan judge sentenced Kevorkian to ten to twenty-five years in prison for second-degree murder. Kevorkian was released on parole in 2007. He died in 2011.

The publicity surrounding Kevorkian sparked intense debate over the morality of physician-assisted suicide. Kevorkian’s detractors dubbed him “Dr. Death.” Surgeon General C. Everett Koop denounced him as “a serial killer who should be put away.”9 Kevorkian’s opponents also pointed out that he was a pathologist, not a psychiatrist. Unlike health care workers, who know their patients for a long time, Kevorkian hardly knew his.

THE HOSPICE MOVEMENT

The modern hospice movement was founded in 1967 by British physician Cicely Saunders to help people die with dignity rather than with fear. The first hospice program in the United States opened in 1974. The philosophy behind hospice is to provide palliative care—pain relief, comfort, and compassion—to the dying. As such, hospice has been active in the development of pain control. Hospice also emphasizes attention to the emotional needs of the patient and the patient’s family.

There are currently over 4,000 hospice programs in the United States. According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, More than 1 million terminally ill patients received services from hospice in 2016.10

Hospice is opposed to the legalization of euthanasia. “If one of our patients requests euthanasia,” Saunders wrote, “it means we are not doing our job.” Saunders continued:

We are not so poor a society that we cannot afford time and trouble and money to help people live until they die. We owe it to all those for whom we can kill the pain which traps them in fear and bitterness. To do this we do not have to kill them…. To make voluntary [active] euthanasia lawful would be an irresponsible act, hindering help, pressuring the vulnerable, abrogating our true respect and responsibility to the frail and the old, the disabled and dying.11

Hospice believes that providing terminally ill people with better palliative care allows them to live their last days in relative comfort and dignity. Advocates of euthanasia maintain that while the hospice program is wonderful for many people, there are still cases in which pain cannot be controlled, and euthanasia should be an option.

THE MORAL ISSUES

The Sanctity of Life

Most Western philosophers believe that human life has intrinsic worth. Legalizing euthanasia, it is argued, will weaken this respect for human life. If life has intrinsic worth, our right not to be killed cannot be overridden, even at our own request.

A variation of this theme is the religious argument, cited by Islam, Judaism, and Roman Catholicism, that our lives are a gift from God and, therefore, we are not free to end them on our own terms. However, physicians are continuously working to prevent death and suffering. Does this interfere with God’s will? Furthermore, those who do not believe in God argue that people are not owned by God. As beings with intrinsic moral worth, we have inalienable rights that cannot be waived by anyone else. One of the most fundamental of these rights is the right of autonomy.

Autonomy and Self-Determination

In its study of why people request euthanasia, the Oregon Health Division found that fear of loss of autonomy was one of the main reasons. (See the report “A Year of Dignified Death” at the end of this chapter.) Autonomy requires two conditions: freedom from outside control and moral agency. According to Margaret Pabst Battin, autonomy is one of the two key principles in the euthanasia debate. Autonomy requires that, in general, physicians respect a competent person’s choices in determining his or her medical treatment, including euthanasia. If euthanasia is a positive right, as Battin claims, physicians may even have a duty to assist their patients in dying.

Some ethicists argue that autonomy and self-determination have been given too much weight in the euthanasia debate and that people do not have a right to do anything they want. In addition, the leap between claiming that people have a right to end their lives and the claim that it is morally acceptable for physicians to assist in this process is not as self-evident as most advocates of active euthanasia would have us believe.

There is also the danger that making euthanasia available will compromise our autonomy. Some people may feel pressured by circumstances, such as lack of medical insurance or family support, into requesting euthanasia. Susan Wolf, in her essay “A Feminist Critique of Physician-Assisted Suicide” from her book Feminism and Bioethics (1996), argues that, given the traditional view of women as self-sacrificing, women are especially vulnerable to these sorts of pressures. Indeed, all nine of the people Kevorkian helped euthanize during the first year were women. Of these, only a few were terminally ill.

Nonmaleficence and the Principle of Ahimsa

The principle of nonmaleficence, or “do no harm,” is one of the strongest moral principles. In the Buddhist prohibition against euthanasia, ahimsa is the deciding principle. Battin, on the other hand, argues that the principle of nonmaleficence and the duty to relieve pain and suffering may, at times, require euthanasia.

Compassion and the Principle of Mercy

The principle of mercy is based on the duty of nonmaleficence. It states that we have a duty both (1) not to cause further pain and suffering and (2) to relieve pain and suffering. Most philosophers agree that the first part of this duty justifies refusal of futile and painful treatment, even though withdrawing or withholding such treatment may result in an earlier death for the patient. Battin maintains that pain relief is a universal duty of physicians and that this duty may entail a positive obligation to use active euthanasia when it is the only way to end pain and suffering.

Hospice, on the other hand, maintains that the appropriate response to suffering is compassionate care, not conceding to a patient’s request to be put to death. The Vatican likewise opposes euthanasia. In the Terri Schiavo case, Pope John Paul II stated that feeding tubes are 117“morally obligatory” for most patients in persistent vegetative states as long as the feeding tube “provides nourishment” and “alleviates suffering.” Pope Francis likewise regards euthanasia as a sin against God and based on, what he calls, a “false sense of compassion.”

Death with Dignity

The expressions “death with dignity” and the “good death” are often heard in euthanasia debates. The number one fear of many people is not fear of dying or of pain, but of loss of control and dignity.12 Advocates of euthanasia argue that respect for the dignity of life entails allowing a person to die with dignity as well, rather than spend the last days of life hooked up to machines and wasting away.

Aaron Rothstein, MD, disagrees. According to him, there is nothing dignified about death. The phrase “death with dignity,” he argues, is simply a euphemism for what he calls “one of the most heart-wrenching and undignified events of a human existence.” (See Rothstein’s reading “All Death Is Death without Dignity” at the end of this chapter.)

Many opponents of euthanasia also believe that the good death involves courageously accepting the suffering entailed in dying. Survival or the inclination to continue living is a natural human goal. Since human dignity comes from seeking our ends, euthanasia is a violation of human dignity and, therefore, diminishes our humanness.

Quality of Life: Pain and Suffering

Human life is more than mere biological existence. As Battin points out, the ability to be in relationships with family and friends, to have hopes for the future, and to live without constant pain are all basic goods. When isolation, pain, and suffering outweigh any expectation of enjoying the goods of life, the quality of that life becomes a negative value and death may be preferable.

Pain, however, such as that associated with most cancers, can be relieved in up to 90 percent of cases. Despite this, many terminally ill people are not offered palliative care. A national survey found that 59 percent of people gave the quality of end-of-life care a fair or poor rating when it comes to making sure patients were as comfortable and pain-free as possible at the end of life.13 This is blamed, in part, not on the lack of effective pain relievers, but on Western society’s opiophobia—fear of drug addiction and abuse.14

There are also other types of suffering, such as lifelong disability, loneliness, and depression. Should there be a moral distinction between wanting to die because one is depressed or facing chronic illness and the pain associated with a terminal illness? (See Case Study 2: Dr. Kevorkian and the Assisted Suicide of Judith Curren.)

Another issue is determining the quality of life of incompetent patients, such as people in comas and young children with disabilities. Who, if anyone, should decide if their lives are worth living? If we answer that euthanasia should be voluntary only, we have to ask ourselves if it is fair that incompetent people be doomed to lives of suffering and hopelessness. On the other hand, John Hardwig asks in his article “Is There a Duty to Die,” if it is fair that society and families be forced to bear the burden of maintaining the lives of hopelessly ill people.15

Ordinary Versus Extraordinary Treatment

The AMA, while opposing active euthanasia, allows the withdrawal of extraordinary treatment. Ordinary medical treatment includes measures that have a reasonable hope of benefiting the 118patient, whereas extraordinary treatments provide no reasonable hope of benefiting the patient. This brings up the question of just when treatment becomes extraordinary. How should we draw the line between prolonging life and prolonging the dying process? Is using chemotherapy on an ailing eighty-five-year-old with cancer ordinary or extraordinary treatment? Also, what counts as a reasonable hope? Is continuing to keep a patient in a coma on artificial life support, even though there is only slight hope of recovery, ordinary or extraordinary treatment?

The Principle of Double Effect: Letting Die Versus Actively Killing

The traditional distinction between active and passive euthanasia rests on intention. In active euthanasia, the intention is to cause the death of another person. In passive euthanasia, there is a “double effect”: the death of the person is an unintended consequence of the intended effect—the elimination of pain and suffering.

Some philosophers claim that this distinction is hypocritical and that physicians are morally responsible for both intended and foreseen consequences. Knowing that high doses of painkillers may hasten a person’s death is an action as much as is administering a lethal injection on request. Both involve decision and action on the part of the physician. Indeed, some claim, there may be cases in which active euthanasia is the more humane alternative.

The Physician’s Role as Healer

Some opponents of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia, such as Ryan T. Anderson, argue that expecting physicians to be agents of death runs contrary to their training as healers and comforters and may damage trust in the patient–physician relationship. This argument, however, does not rule out euthanasia. The act of euthanasia could instead be left to others, perhaps people like Dr. Kevorkian or “death technicians,” who specialize in it.

Patient Competence

Two of the problems in deciding who should be a candidate for euthanasia are (1) determining if a patient is rational and competent to make such a decision and (2) determining whether it is a sincere request for death or a cry for help. What, in other words, are the patient’s real intentions? Furthermore, if the patient is incompetent, how do we determine what is in the patient’s best interests? Some people argue that physicians or close family members can usually be counted on to respect a patient’s self-determination, whereas others question the insidious effect of cultural biases, such as sexism, on these decisions.

Some claim that the request, especially in cases in which the patient is able to carry out the suicide without assistance, is often a cloaked request for help. Suicide prevention workers point out that people who are suicidal often feel a sense of depression, hopelessness, and despair. Rather than seeking to end their lives, the request to die is really an expression of that despair and, as such, is a cry for help.

Justice and the Principle of Equality

Some opponents of euthanasia maintain that it is always unjust because it involves the death of an innocent person. Battin, on the other hand, maintains that the duty of justice may require euthanasia, especially in cases in which keeping a person alive is tremendously expensive.

There is also the concern that euthanasia may be unjust because it unfairly targets certain groups. In societies that hold up self-sacrifice as a virtue for women, women are especially vulnerable to pressures to put the needs and desires of others before their own. The physician-assisted death of Judith Curren, who was later alleged to have been abused by her husband, is just one case in point (see Case Study 2: Dr. Kevorkian and the Assisted Suicide of Judith Curren).

Another concern is our society’s negative view of people who are disabled and the tendency to devalue their lives. While it may be countered that disabled people fall outside the scope of euthanasia because they are not terminally ill, the facts show that infants and children with disabilities, such as Baby Doe, are vulnerable to euthanasia. A study of infant deaths at the special-care unit of the Yale–New Haven Hospital between 1970 and 1972 revealed that of 299 deaths, 14 percent were associated with the withholding or withdrawal of treatment in cases of severe congenital disorders.16

Burdens to Society and a Duty to Die

The majority of Dutch and American doctors favor physician-assisted suicide for a patient in excruciating pain.17 However, they differ in their justifications of euthanasia. Dutch doctors are more likely to support physician-assisted suicide in cases in which a patient finds life meaningless; American physicians are more likely to consider a patient’s fear of being a burden as a justification for euthanasia.

Battin argues that when costly medical resources are needed to sustain a human life, the principle of justice may warrant involuntary active euthanasia. End-of-life costs account for 10 percent of total health care spending in the United States and 27 percent of Medicare expense.18 Medicare spent $55 billion in 2010 for hospital and physician care during the last two months of a patient’s life. Up to a third of this expense had no meaningful impact on the patient.19 In contrast, it costs only a few dollars to deliver a lethal injection.

The baby boomers, those 78 million Americans born between 1945 and 1961, are the largest generation in American history. The aging baby boomer population can be expected to drive up health care costs in the next few decades. Some people argue that the burden to family and society creates a “duty to die.” According to this point of view, there comes a time in life when we have a duty to let go. In a nonegalitarian society, however, where the lives of certain groups are valued less than others, a duty to die might come into conflict with the principle of justice by unfairly targeting certain people, such as women, the poor, and the disabled.

John Kelly, a disability rights activist, points out in his reading at the end of this chapter that people with disabilities, including newborns, are disproportionately targeted for euthanasia. If involuntary euthanasia were legalized, this would put these populations at even greater risk.

The Finality of Death versus the Hope of Recovery

Although rare, there are cases in which a patient comes out of a coma or makes a miraculous recovery despite a prognosis of imminent death or irreversible brain damage. Jackie Cole suffered a stroke and massive bleeding in her brain. The doctors predicted that without artificial life support she would be dead within a few days. Before slipping into a coma, she had made it clear that she did not want to be kept alive by artificial means. The court, however, refused her husband’s petition to have life support withdrawn. Six days later Cole awoke from the coma and slowly began to recover.

What is a reasonable cost of sustaining hope? Do cases like Jackie Cole’s justify spending millions of dollars keeping comatose people alive in hopes that a few of them will come out of it? Some opponents of euthanasia say yes. If euthanasia is legal, we are more likely to give up hope as well as not put as much effort into research for new cures.

Slippery Slope Argument

Even if euthanasia can be morally justified in principle, there may still be problems when it comes to legalizing it because of the difficulty of drawing the line between who should and who should not be eligible. If there is no definite line to stop abuses, it will be easy to slip down the slope toward greater and greater acceptance of euthanasia. A report from the Netherlands found that Dutch physicians “sometimes act without patient requests in performing euthanasia and that there was a sense among some patients that they had a duty to die.”20 The right to euthanasia, in other words, can slip into a duty to die. If euthanasia is an option, it will also be easy to redefine chronic medical conditions as terminal illnesses to justify the euthanasia of people who have Alzheimer’s or of children with genetic disorders, a practice that has already begun to some extent.21

CONCLUSION

The moral issues surrounding euthanasia are complex. Many of the relevant principles come into conflict with one another and need to be carefully weighed. A further complication is the uncertainty of medical prognoses and the presence of subjective factors in assessing patients’ requests for euthanasia. In addition, public policies on euthanasia need to be drafted within the wider social context. As with abortion, the judgment that euthanasia, or at least certain types of it, is morally acceptable does not imply that the law should permit it.

MARGARET PABST BATTIN

MARGARET PABST BATTIN

The Case for Euthanasia

Margaret Pabst Battin is a professor of philosophy and adjunct professor of internal medicine, Division of Medical Ethics, at the University of Utah. She is also the author of the book The Least Worst Death (1994). Battin argues that the moral values of mercy, justice, and autonomy support the legalization of euthanasia.

Author’s note: When this article was first published in 1987, the meaning of the term ‘euthanasia’ as used in the United States had both positive and negative connotations. ‘Passive euthanasia,’ understood as ‘allowing to die,’ was generally accepted; ‘active (voluntary) euthanasia’ was controversial; involuntary euthanasia was rejected. ‘Euthanasia’ was sometimes understood in the original Greek sense of ‘good death,’ as it is in the Netherlands, sometimes in the post-Nazi sense of killing on ulterior grounds having nothing to do with the interests of the patient. However, as this article is republished in 2018, more than a quarter-century after its first appearance, the terms ‘euthanasia’ and ‘killing’ as they are used in U.S. bioethics have come to have almost exclusively negative connotations. Furthermore, a distinction is now made between “suicide” as it is conventionally understood and “aid in dying” (see the 2017 statement of the American Association of Suicidology), such that the term “physician assisted suicide” is no longer regarded as appropriate. The reader of this article is asked to keep these linguistic changes in mind.

Battin, Margaret P., “The Case for Euthanasia”, from Health Care Ethics, edited by Donald Vandeveer and Tom Regan. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1987. Used with permission of the author. 58–95. Some notes have been omitted.

Because it arouses questions about the morality of killing, the effectiveness of consent, the duties of physicians, and equity in the distribution of resources, the problem of euthanasia is one of the most acute and uncomfortable contemporary problems in medical ethics. It is not a new problem; euthanasia has been discussed—and practiced—in both Eastern and Western cultures from the earliest historical times to the present. But because of medicine’s new technological capacities to extend life, the problem is much more pressing than it has been in the past, and both the discussion and practice of euthanasia are more widespread. Despite this, much of contemporary Western culture remains strongly opposed to euthanasia: doctors ought not kill people, its public voices maintain, and ought not let them die if it is possible to save life.

I believe that this opposition to euthanasia is in serious moral error—on grounds of mercy, autonomy, and justice. I shall argue for the rightness of granting a person a humane, merciful death, if he or she wants it, even when this can be achieved only by a direct and deliberate killing….

THE CASE FOR EUTHANASIA, PART I: MERCY

The case for euthanasia rests on three fundamental moral principles: mercy, autonomy, and justice.

The principle of mercy asserts that where possible, one ought to relieve the pain or suffering of another person, when it does not contravene that person’s wishes, where one can do so without undue costs to oneself, where one will not violate other moral obligations, where the pain or suffering itself is not necessary for the sufferer’s attainment of some overriding good, and where the pain or suffering can be relieved without precluding the sufferer’s attainment of some overriding good. This principle might best be called the principle of medical mercy, to distinguish it from principles concerning mercy in judicial contexts…. Contexts that require mercy sometimes require euthanasia as a way of granting mercy—both by direct killing and by letting die….

“Relief of pain is the least disputed and most universal of the moral obligations of the physician,” writes one doctor. “Few things a doctor does are more important than relieving pain,” says another.1 These are not simply assertions that the physician ought “do no harm,” as the Hippocratic oath is traditionally interpreted, but assertions of positive obligation….

This principle of mercy establishes two component duties:

the duty not to cause further pain or suffering; and

the duty to act to end pain or suffering already occurring.

Under the first of these, for a physician or other caregiver to extend mercy to a suffering patient may mean to refrain from procedures that cause further suffering—provided, of course, that the treatment offers the patient no overriding benefits. So, for instance, the physician must refrain from ordering painful tests, therapies, or surgical procedures when they cannot alleviate suffering or contribute to a patient’s improvement or cure….

Of course, whether a painful test or therapy will actually contribute to some overriding good for the patient is not always clear. Nevertheless, the principle of mercy directs that where such procedures can reasonably be expected to impose suffering on the patient without overriding benefits for him or her, they ought not be done….

In such cases, the principle of mercy demands that the “treatments” no longer be imposed, and that the patient be allowed to die.

But the principle of mercy may also demand “letting die” in a still stronger sense. Under its second component, the principle asserts a duty to act to end suffering that is already occurring. Medicine already honors this duty through its various techniques of pain management…. But there are some difficult cases in which pain or suffering is severe but cannot be effectively controlled, at least as long as the patient remains sentient at all. Classical examples include tumors of the throat (where agonizing discomfort is not just a matter of pain but of inability to swallow, “air hunger,” or acute shortness of breath), tumors of the brain or bone, and so on. Severe nausea, vomiting, and exhaustion may increase the patient’s misery. In these cases, continuing life—or at least continuing consciousness—may mean continuing pain. Consequently, mercy’s demand for euthanasia takes hold here: mercy demands that the pain, even if with it the life, be brought to an end.

Ending the pain, though with it the life, may be accomplished through what is usually called “passive euthanasia,” withholding or withdrawing treatment that 123could prolong life. In the most indirect of these cases, the patient is simply not given treatment that might extend his or her life—say, radiation therapy in advanced cancer….

But the second component of the principle of mercy may also demand the easing of pain by means more direct than mere allowing to die; it may require killing. This is usually called “active euthanasia,” and despite borderline cases (for instance, the ancient Greek practice of infanticide by exposure), it can in general be conceptually distinguished from passive euthanasia. In passive euthanasia, treatment is withheld that could support failing bodily functions, either in warding off external threats or in performing its own processes; active euthanasia, in contrast, involves the direct interruption of ongoing bodily processes that otherwise would have been adequate to sustain life. However, although it may be possible to draw a conceptual distinction between passive and active euthanasia, this provides no warrant for the ubiquitous view that killing is morally worse than letting die. Nor does it support the view that withdrawing treatment is worse than withholding it. If the patient’s condition is so tragic that continuing life brings only pain, and there is no other way to relieve the pain than by death, then the more merciful act is not one that merely removes support for bodily processes and waits for eventual death to ensue; rather, it is one that brings the pain—and the patient’s life—to an end now. …

But, it may be objected, the cases we have mentioned to illustrate intolerable pain are classical ones; such cases are controllable now. Pain is a thing of the medical past, and euthanasia is no longer necessary, though it once may have been, to relieve pain…. Particularly impressive are the huge advances under the hospice program in the amelioration of both the physical and emotional pain of terminal illness, and our culturewide fears of pain in terminal cancer are no longer justified: cancer pain, when it occurs, can now be controlled in virtually all cases. We can now end the pain without also ending the life.

This is a powerful objection, and one very frequently heard in medical circles. Nevertheless, it does not succeed. It is flatly incorrect to say that all pain, including pain in terminal illness, is or can be controlled. Some people still die in unspeakable agony. With superlative care, many kinds of pain can indeed be reduced in many patients, and adequate control of pain in terminal illness is often quite easy to achieve. Nevertheless, complete, universal, fully reliable pain control is a myth. Pain is not yet a “thing of the past,” nor are many associated kinds of physical distress…. Finally, there are cases in which pain control is theoretically possible but for various extraneous reasons does not occur. Some deaths take place in remote locations where there are no pain-relieving resources. Some patients are unable to communicate the nature or extent of their pain. And some institutions and institutional personnel who have the capacity to control pain do not do so, whether from inattention, malevolence, fears of addiction, or divergent priorities in resources.

In all these cases, of course, the patient can be sedated into unconsciousness; this does indeed end the pain. But in respect of the patient’s experience, this is tantamount to causing death: the patient has no further conscious experience and thus can achieve no goods, experience no significant communication, satisfy no goals. Furthermore, adequate sedation, by depressing respiratory function, may hasten death….

The principle of mercy holds that suffering ought to be relieved—unless, among other provisos, the suffering itself will give rise to some overriding benefit or unless the attainment of some benefit would be precluded by relieving the pain. But it might be argued that life itself is a benefit, always an overriding one. Certainly life is usually a benefit, one that we prize. But unless we accept certain metaphysical assumptions, such as “life is a gift from God,” we must recognize that life is a benefit because of the experiences and interests associated with it…. Philippa Foot treats this as a conceptual point: “Ordinary human lives, even very hard lives, contain a minimum of basic goods, but when these are absent the idea of life is no longer linked to that of good.”2

Such basic goods, she explains, include not being forced to work far beyond one’s capacity; having the support of a family or community; being able to more or less satisfy one’s hunger; having hopes for the future; and being able to lie down to rest at night. When these goods are missing, she asserts, the connection between life and good is broken, and we cannot count it as a benefit to the person whose life it is that his life is preserved.

These basic goods may all be severely compromised or entirely absent in the severely ill or dying patient…. Yet even for someone lacking all of what Foot considers to be basic goods, the experiences associated with life may not be unrelievedly negative. We must be very cautious in asserting of someone, even someone in the most 124abysmal-seeming conditions of the severely ill or dying, that life is no longer a benefit, since the way in which particular experiences, interests, and “basic goods” are valued may vary widely from one person to the next….

It is true that contemporary pain management techniques do make possible the control of pain to a considerable degree. But unless pain and discomforting symptoms are eliminated altogether without loss of function, the underlying problem for the principle of mercy remains: how does this patient value life, how does he or she weigh death against pain? We are accustomed to assume that only patients suffering extreme, irremediable pain could be candidates for euthanasia at all and do not consider whether some patients might choose death in preference to comparatively moderate chronic pain, even when the condition is not a terminal one. Of course, a patient’s perceptions of pain are extremely subject to stress, anxiety, fear, exhaustion, and other factors, but even though these perceptions may vary, the underlying weighing still demands respect. This is not just a matter of differing sensitivities to pain, but of differing values as well: for some patients, severe pain may be accepted with resignation or even pious joy, whereas for others mild or moderate discomfort is simply not worth enduring….

If the sufferer is the best judge of the relative values of that suffering and other benefits to himself, then his own choices in the matter of mercy ought to be respected. To impose “mercy” on someone who insists that despite his suffering life is still valuable to him would hardly be mercy; to withhold mercy from someone who pleads for it, on the basis that his life could still be worthwhile for him, is insensitive and cruel. Thus, the principle of mercy is conceptually tied to that of autonomy, at least insofar as what guarantees the best application of the principle—and hence, what guarantees the proper response to the ostensive premise in the argument from mercy—is respect for the patient’s own wishes concerning the relief of his suffering or pain.

To this issue we now turn.

THE CASE FOR EUTHANASIA, PART II: AUTONOMY

The second principle supporting euthanasia is that of (patient) autonomy: one ought to respect a competent person’s choices, where one can do so without undue costs to oneself, where doing so will not violate other moral obligations, and where these choices do not threaten harm to other persons or parties. This principle of autonomy, though limited by these provisos, grounds a person’s right to have his or her own choices respected in determining the course of medical treatment, including those relevant to euthanasia: whether the patient wishes treatment that will extend life, though perhaps also suffering, or whether he or she wants the suffering relieved, either by being killed or by being allowed to die. It would of course also require respect for the choices of the person whose condition is chronic but not terminal, the person who is disabled though not dying, and the person not yet suffering at all, but facing senility or old age. Indeed, the principle of autonomy would require respect for self-determination in the matter of life and death in any condition at all, provided that the choice is freely and rationally made and does not harm others or violate other moral rules. Thus, the principle of autonomy would protect a much wider range of life-and-death acts than those we call euthanasia, as well as those performed for reasons of mercy….

It is often objected that autonomy in euthanasia choices should not be recognized in practice, whether or not it is accepted in principle, because such choices are often erroneously made. One version of this argument points to physician error…. People diagnosed as dying rapidly of inexorable cancers have survived, cancer-free, for dozens of years; people in cardiac failure or long-term irreversible coma have revived and regained full health….

A second argument pointing to the possibility of erroneous choice on the part of the patient asserts the very great likelihood of impairment of the patient’s mental processes when seriously ill. Impairing factors include depression, anxiety, pain, fear, intimidation by authoritarian physicians or institutions, and drugs used in medical treatment that affect mental status. Perhaps a person in good health would be capable of calm, objective judgment even in such serious matters as euthanasia, so this view holds, but the person as patient is not. Depression, extremely common in terminal illness, is a particular culprit: it tends to narrow one’s view of the possibilities still open; … A choice of euthanasia in terminal illness, this view holds, probably reflects largely the gloominess of the depression, not the gravity of the underlying disease or any genuine intention to die.

If this is so, ought not the euthanasia request of a patient be ignored for his or her own sake? According to 125a limited paternalistic view (sometimes called “soft” or “weak” paternalism), intervention in a person’s choices for his or her own sake is justified if the person’s thinking is impaired. Under this principle, not every euthanasia request should be honored; such requests should be construed, rather, as pleas for more sensitive physical and emotional care.

It is no doubt true that many requests to die are pleas for better care or improved conditions of life. But this still does not establish that all euthanasia requests should be ignored, because the principle of paternalism licenses intervention in a person’s choices just for his or her own good. Sometimes the choice of euthanasia, though made in an impaired, irrational way, may seem to serve the person’s own good better than remaining alive. Thus, since the paternalist, in intervening, must act for the sake of the person in whose liberty he or she interferes, the paternalist must take into account not only the costs for the person of failing to interfere with a euthanasia decision when euthanasia was not warranted (the cost is death, when death was not in this person’s interests) but also the costs for that person of interfering in a decision that was warranted (the cost is continuing life—and continuing suffering—when death would have been the better choice). The likelihood of these two undesirable outcomes must then be weighed. To claim that “there’s always hope” or to insist that “the diagnosis could be wrong” in a morally responsible way, one must weigh not only the cost of unnecessary death to the patient but also the costs to the patient of dying in agony if the diagnosis is right and the cure does not materialize….

As with limited paternalism, extended “strong” or “hard” paternalism—permitting intervention not merely to counteract impairment but also to avoid great harm—provides a special case when applied to euthanasia situations. The hard paternalist may be tempted to argue that because death is the greatest of harms, euthanasia choices must always be thwarted. But the initial premise of this argument is precisely what is at issue in the euthanasia dispute itself, as we’ve seen: is death the worst of harms that can befall a person, or is unrelieved, hopeless suffering a still worse harm? The principle of mercy obliges us to relieve suffering when it does not serve some overriding good; but the principle itself cannot tell us whether sheer existence—life—is an overriding good. In the absence of an objectively valid answer, we must appeal to the individual’s own preferences and values….

To claim that an incessantly pain-racked but conscious person cannot make a rational choice in matters of life and death is to misconstrue the point: he or she, better than anyone else, can make such a choice, based on intimate acquaintance with pain and his or her own beliefs and fears about death. If the patient wishes to live, despite such suffering, he or she must be allowed to do so; or the patient must be granted help if he or she wishes to die.

But this introduces a further problem. The principle of autonomy, when there are no countervailing considerations on paternalistic grounds or on grounds of harm to others, supports the practice of voluntary euthanasia and, in fact, any form of rational, voluntary suicide. We already recognize a patient’s right to refuse any or all medical treatment and hence correlative duties of noninterference on the part of the physician to refrain from treating the patient against his or her will. But does the patient’s right of self-determination also give rise to any positive obligation on the part of the physician or other bystander to actively produce death? … Although we usually recognize only that the principle of autonomy generates rights to noninterference, in some circumstances a right of self-determination does generate claims to assistance or to the provision of goods….

Some singularly sympathetic cases—like that of the completely paralyzed cerebral palsy victim Elizabeth Bouvier—have brought this issue to public attention. But notice that in euthanasia situations, most persons are handicapped with respect to producing for themselves an easy, “good,” merciful death. The handicaps are occasionally physical, but most often involve lack of knowledge of how to bring this about and lack of access to means for so doing…. Full autonomy is not achieved until one can both choose and act upon one’s choices. It is here, in these cases of “handicap” that afflict many or most patients, that rights to self-determination may generate obligations on the part of physicians (provided, perhaps, that they do not have principled objections to participation in such activities themselves). The physician’s obligation is not only to respect the patient’s choices but also to make it possible for the patient to act upon his or her choices. This means supplying the knowledge and equipment to enable the person to stay alive, if he or she so chooses; this is an obligation 126physicians now recognize. But it may also mean providing the knowledge, equipment, and help to enable the patient to die, if that is his or her choice; this is the other part of the physician’s obligation, only now, beginning with the Oregon Death with Dignity Act of 1997 and as of 2018 legal in seven states and the District of Columbia, beginning to be recognized by the medical profession and the law in the United States.

This is not to say that any doctor should be forced to kill any person who asks that: other contravening considerations—particularly that of ascertaining that the request is autonomous and not the product of coerced or irrational choice, and that of controlling abuses by unscrupulous physicians, relatives, or patients—would quickly override. Nor would the physician have an obligation to assist in “euthanasia” for someone not severely ill. But when the physician is sufficiently familiar with the patient to know the seriousness of the condition and the earnestness of the patient’s request, when the patient is sufficiently helpless, and when there are no adequate objections on grounds of personal scruples or social welfare, then the principle of autonomy—like the principle of mercy— imposes on the physician the obligation to help the patient in achieving an easy, painless death.

THE CASE FOR EUTHANASIA, PART III: JUSTICE

Although the term “euthanasia” traditionally was employed in cases in which “good death” meant the avoidance of suffering, in recent years use of the term has been extended to cover cases in which the patient is neither suffering nor capable of choosing to die….

This argument from justice is usually employed only to justify the denial of treatment, that is, to justify passive euthanasia; but similar considerations also favor active euthanasia. Passive euthanasia is often practiced upon unsalvageable patients by withholding treatment if a medical crisis occurs: for instance, no-code orders are issued, or pneumonias are not treated, or electrolyte imbalances not corrected if they occur. If justice demands that, despite the prima facie claims of these patients, the resources allocated to their care are better assigned somewhere else, then we must notice that passive euthanasia does not provide the most just redistribution of these resources. To “allow” the patient to die may still involve enormous expenditures of money, scarce supplies, or caregiver time. This is most evident in cases of “irretrievably inaccessible” patients, for whom no considerations of mercy or autonomy override the demands of justice in weighing claims…. The total cost of maintaining a permanently comatose woman, who was injured in a riding accident in 1956 at age twenty-seven and died eighteen years later, has been estimated at just over $6,000,000; this care provided her with not a single moment of conscious life.3 The record survival for a coma patient is thirty-seven years and 111 days.4 The argument from justice demands that these patients, since their claims for care are so weak as to have virtually no force at all, be killed, not simply allowed to die.

OBJECTION TO THE ARGUMENT FROM JUSTICE: THE SLIPPERY SLOPE

But if justice, under the distributive principle employed here, licenses the killing of permanently comatose patients, will it not also license the killing of still-conscious, still-competent dying patients, perhaps still salvageable, close or not so close to death? What extensions of the scope of this principle might be made, should resources become still more scarce? These concerns introduce the “wedge” or “slippery slope” argument, which holds that although some acts of euthanasia may be morally permissible (say, on grounds of mercy or autonomy), to allow them to occur will set a logical precedent for, or will causally result in, consequences that are morally repugnant. Just as Hitler’s 1938 “euthanasia” program for mentally defective, senile, and terminally ill Aryans paved the way for the establishment of the extermination camps several years later, it is argued, so permissive euthanasia policies invite irreversible descent down that slippery slope that leads to mass murder….

As it is usually posed, the form of the argument that points to the Nazi experience does not succeed: the forces that brought the mass extermination camps into being were not caused by the earlier euthanasia program, and, other things being equal, the extermination camps for Jews would no doubt have been established had there been no euthanasia program at all. To argue that permitting euthanasia now will lead to death camps like 127Hitler’s is to overlook the many other political, social, and psychological factors of the Nazi period. Yet the wedge argument cannot be simply discarded; the factors operating to favor the slide from morally warranted euthanasia to murder are probably much stronger than we realize. They are best seen, I think, as misunderstandings or corruptions of the very principles that favor euthanasia: mercy, autonomy, and perhaps most prominently, justice.

A contemporary version of the wedge argument holds that to permit euthanasia at all—including cases justified on grounds of mercy, autonomy, or justice—will in the presence of strong financial incentives lead to circumstances in which people are killed who are not suffering or who do not wish to die. Furthermore, to permit some doctors to allow their patients to die or to kill them would invite cavalier attitudes concerning the lives of the patients and, in addition to financial incentives, ordinary greed, insensitivity, hastiness, and self-interest, would cause some doctors to let their patients die—or kill them—when there was no moral warrant for doing so. Doctors treating difficult or unresponding patients would find an easy way out. Medical blunders could be more easily covered up, and doctors might use euthanasia as a way of avoiding criticism in cases that were medically difficult to treat. Particularly important, perhaps, are societal and political pressures, most evident in cost-containment policies, to which doctors might respond. After all, to permit earlier, less expensive death would ease the enormous pressures on third-party insurers, public welfare, and the Social Security system: euthanasia is less expensive than continuing medical care….

Is there any reason to think such practices would actually occur? The reasons are closer to hand than one might imagine. Rather than predicting the future, we need simply look to our present practices for evidence that violations of the moral limits to euthanasia can occur….

The wedge argument assumes, without adequate justification, that the rights of those who may become the victims of abuses of a practice outweigh the rights of those who become victims if a practice is prohibited to whose benefits they are morally entitled and urgently need.

To protect those who might wrongly be killed or allowed to die might seem a stronger obligation than to satisfy the wishes of those who desire release from pain, analogous perhaps to the principle in law that “better ten guilty men go free than one be unjustly convicted.”… But to require the person who chooses to die to stay alive in order to protect those who might unwillingly be killed sometime in the future is to impose an extreme harm—intolerable suffering—on that person, which he or she must bear for the sake of others. Furthermore, since, as we’ve seen, the question of which is worse, suffering or death, is person—relative, we have no independent, objective basis for protecting the class of persons who might be killed at the expense of those who would suffer intolerable pain; perhaps our protecting ought to be done the other way around….

CONCLUSION: EUTHANASIA AND SUICIDE

It may be objected that requiring the patient to choose between death and life, insofar as the patient must antecedently consider treatment decisions that affect the circumstances and timing of his or her own demise, is equivalent to requiring the patient’s consideration of suicide. In a sense, it is; but this is also the more general solution to the euthanasia problem. Although euthanasia is indeed warranted on grounds of mercy, autonomy, and justice, these principles can be more effectively and safely honored by permitting suicide, perhaps assisted by the physician who has care of the patient or a family member under the advice of the physicians, and supplemented by nonvoluntary euthanasia only when the patient is permanently comatose or otherwise irretrievably inaccessible. Not only do practical reasons like avoiding greed and manipulation on the part of the physicians or the institutions controlling them speak for preferring physician-assisted suicide to physician-initiated euthanasia, but there are conceptual reasons as well. The conditions that distinguish morally permissible euthanasia from impermissable murder all involve matters that the patient, not the physician, is in a privileged position to know. To extend mercy, the physician must know how the patient weights suffering against death, and at what point for the patient death becomes the lesser of two evils. To respect the patient’s autonomy, the physician must know what his or her preferences are, given the alternatives available, in the matter of dying. And to exercise justice, the physician must know what treatment the patient realistically desires…. Consequently, since the risk of misinterpretation is great and the possibility of 128manipulation or coercion high, the physician should not be the one to initiate the choice. Rather, he or she must be prepared to assist the patient who chooses death, just as he or she is prepared to assist the patient who chooses continuing life….

NOTES

1. Edmund D. Pellegrino, M.D., “The Clinical Ethics of Pain Management in the Terminally Ill,” Hospital Formulary 17 (November 1982): 1495–1496; and Marcia Angell, “The Quality of Mercy,” New England Journal of Medicine 306 (January 1982): 98–99.

2. Philippa Foot, “Euthanasia,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 6 (Winter 1977): 95.

3. This case, originally presented in the Illinois Medical Journal and reprinted in Connecticut Medicine with commentary from medical, ethical, and legal experts, is summarized in Concern for Dying 8 (Summer 1982): 3.

4. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, Defining Death: Medical, Legal, and Ethical Issues in the Determination of Death (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1981), 18, citing the Guiness Book of World Records regarding the case of Elaine Esposito.

OREGON HEALTH DIVISION

OREGON HEALTH DIVISION

A Year of Dignified Death

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) became a legal option for terminally ill patients in Oregon in October 1997 under the Death with Dignity Act. The law requires the Health Division to collect information on the patients and physicians who use the legal option and to publish an annual statistical report. Following is a summary of first official report.

DIGNITY ACT REQUIREMENTS

To obtain a prescription for lethal medications in Oregon, a requesting patient must be an adult, at least 18 years old, and a resident of Oregon (specific residency requirements are not defined in the current law). The Act requires that the patient be “capable” (defined as being able to make and communicate healthcare decisions). The patient must have a terminal illness with less than 6 months to live, and the request for a lethal prescription must be voluntary.

A patient who meets these requirements must make one written and two verbal requests to his or her physician. The verbal requests must be separated by at least 15 days. The prescribing physician and a consultant physician are required to confirm the terminal diagnosis and prognosis, determine that the patient is capable and acting voluntarily, and refer the patient for counseling if either believes that the patient’s judgement is impaired by a psychiatric or psychological disorder. The prescribing physician must also inform the patient of feasible alternatives such as comfort care, hospice care, and pain control options. Patients and physicians who adhere to the requirements of the Act are protected from criminal prosecution. The law specifically prohibits euthanasia (i.e., the physician cannot directly administer the lethal medications).

“A Year of Dignified Death,” CD Summary, Vol. 48, No. 6, March 16, 1999. www.ohd.hr.state.or.us/

OHD’S ROLE

To fulfill its mandate, the Health Division enacted reporting rules and created reporting forms.† To be in legal compliance, physicians are required to report the writing of all prescriptions for lethal medications by either completing a set of forms (available from the OHD website) or providing copies of relevant portions of the patient’s chart. We compiled data from these physician prescription reports and from patient death certificates. To learn more about patients who participated in the Death with Dignity Act during the first year of legalized PAS, we also collected information by conducting in-depth interviews with each prescribing physician after receipt of their patient’s death certificate. Each physician was first asked if their patient took the lethal medications and was then asked a series of questions about their patient’s underlying illness, insurance status, and end-of-life care and concerns. Because of privacy concerns, we did not interview patients, their families, or other physicians who may have provided end-of-life care.

Because of the highly charged debates surrounding this issue, we believed it was important to provide more 130than just a descriptive characterization of the Death with Dignity participants. To this end, we performed two studies comparing terminally ill Oregonians who chose PAS and took their lethal medications, with Oregonians who died from similar terminal illnesses but who did not participate in the Death with Dignity Act. The comparison studies had two goals. The first was to better understand where PAS participants fit within the spectrum of all terminally- ill patients in Oregon. The second was to try and address some of the questions and concerns surrounding this issue. Who would choose PAS and why? Would PAS be disproportionately chosen by patients who were poor, less educated, uninsured, fearful of financial ruin, or lacking in access to end-of-life care or proper pain control?

WHY WE ASKED WHAT WE ASKED

In constructing our reporting system and comparison studies, we struggled with what specific questions and issues to address. The choice of PAS may potentially be influenced by moral, ethical, medical, or financial factors. We chose to focus on issues that government and public health might influence such as access to hospice care, palliative pain control, lack of insurance, or financial fears. We did not specifically examine the influence of moral, ethical, or religious views of the choice of PAS.

WHAT HAPPENED IN 1998?

Details of the methods and results are available in both of the published reports. Here are some of the key findings.

The Health Division received information on 23 persons who received prescriptions for lethal medications under the Death with Dignity Act in 1998 (no prescriptions were written under the Act in 1997). Of these 23 prescription recipients, 15 chose PAS and died after taking their lethal medications, 6 died from their underlying illnesses, and 2 were alive as of January 1, 1999. The 15 persons who chose PAS accounted for 5 of every 10,000 deaths in Oregon in 1998.

Patients who chose PAS were comparable to all Oregonians who died of similar underlying illnesses with respect to age, race, sex, and Portland residence. Patients who chose PAS were not disproportionately poor (as measured by Medicaid status), less educated, lacking in insurance coverage, lacking in access to hospice care, fearful of intractable end of life pain, or concerned about the financial impact of their illnesses. Rather, the choice of PAS was most strongly associated with concerns about loss of autonomy and loss of control of bodily functions.

In 1998, many physicians in Oregon were unable or unwilling to participate in PAS. The physicians who did participate, by writing lethal prescriptions for patients who chose PAS, represented a wide range of specialties, ages, and years in practice.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations that should be kept in mind when considering these findings. First, the small number of patients who chose PAS in 1998 limits our ability to detect smaller differences in the characteristics of patients who chose PAS and those who did not. Second, the possibility of physician recall bias must be considered. Because of the unique nature and requirements of the Death with Dignity Act, prescribing physicians may have recalled their conversations with requesting patients in greater detail than physicians for patients in the comparison group. For that matter, the entire account could have been a cock-and-bull story. We assume, however, that physicians were their usual careful and accurate selves. Finally, the Health Division has no formal enforcement role; however, we are required to report any noncompliance with the law to the Oregon Board of Medical Examiners for further investigation. Because of this obligation, we cannot detect or accurately comment on issues that may be under reported.

NEUTRALITY AND CONFIDENTIALITY

The Health Division’s goal is to be the Switzerland of this debate. Maintaining neutrality and protecting the confidentiality of the patients and physicians who participate in the Death with Dignity Act are paramount if this reporting system, and the resulting data, are to 131remain legitimate. The goals of our report do not include taking sides. Rather, we are charged with collecting data and have tried to present these data objectively and within the context of some of the ongoing debates.

DON’T FORGET US

Again, we remind all our physician readers that prescriptions written under the Death with Dignity Act must be reported. Not only is it the law, it is the only mechanism which offers you protection from criminal prosecution and offers your patient protection from insurance companies who may wish to deny benefits because of PAS. We are charged with monitoring compliance but we are not here to be intimately involved in the interactions between you and your patients or in the decision processes that may lead to the writing of a lethal prescription. Our surveillance is ongoing and your participation (and your patient’s) is held in the strictest confidence. The Death with Dignity Act, reporting rules, reporting forms, and 1998 report can be found at the Health Division’s web site (vide recto), or can be ordered by contacting us at 503/731-4024.

BRAD WENSTRUP

BRAD WENSTRUP

Resolution Before the United States House of Representatives Opposing Assisted Suicide (H. CON. RES. 80)

September 26, 2017

Brad Wenstrup is a U.S. representative from Ohio, 2nd Congressional district. In the following 2017 resolution opposing assisted suicide, Wenstrup and his fellow representatives argue that assisted suicide puts the most vulnerable at risk and undermines the integrity of health care and, 132therefore, should not be endorsed by the government. They argue instead that quality end-of-life care should be improved.

Mr. Wenstrup (for himself, Mr. Correa, Mr. Vargas, Mr. Langevin, Mr. Lipinski, Mr. Harris, Mr. LaHood, Mr. Abraham, Mr. Rothfus, and Mr. Suozzi) submitted the following concurrent resolution, which was referred to the Committee on Energy and Commerce. H.ConRes.80. 115th Congress, 1st Session, September 26, 2017

Expressing the sense of the Congress that assisted suicide (sometimes referred to as death with dignity, end-of-life options, aid-in-dying, or similar phrases) puts everyone, including those most vulnerable, at risk of deadly harm and undermines the integrity of the health care system.

Whereas “suicide” means the act of intentionally ending one’s own life, preempting death from disease, accident, injury, age, or other condition;

Whereas “assisting in a suicide” means knowingly and willingly prescribing, providing, dispensing, or distributing to an individual a substance, device, or other means that, if taken, used, ingested, or administered as directed, expected, or instructed, will, with reasonable medical certainty, result in the death of the individual, preempting death from disease, accident, injury, age, or other condition;

Whereas society has a longstanding policy of supporting suicide prevention such as through the efforts of many public and private suicide prevention programs, the benefits of which could be denied under a public policy of assisted suicide;

Whereas assisted suicide most directly threatens the lives of people who are elderly, experience depression, have a disability, or are subject to emotional or financial pressure to end their lives;

Whereas the Oregon Health Authority’s annual reports reveal that pain or the fear of pain is listed second to last (25 percent) among the reasons cited by all patients seeking lethal drugs since 1998, while the top five reasons cited are psychological and social concerns: “losing autonomy” (92 percent), “less able to engage in activities that make life enjoyable” (90 percent), “loss of dignity” (79 percent), “losing control of bodily functions” (48 percent), and “burden on family friends/caregivers” (41 percent);

Whereas the United States Supreme Court has ruled twice (in Washington v. Glucksberg and Vacco v. Quill) that there is no constitutional right to assisted suicide, that the Government has a legitimate interest in prohibiting assisted suicide, and that such prohibitions rationally relate to “protecting the vulnerable from coercion” and “protecting disabled and terminally ill people from prejudice, negative and inaccurate stereotypes, and ‘societal indifference;’” …

Whereas States that authorize assisted suicide for terminally ill patients do not require that such patients receive psychological screening or treatment, though studies show that the overwhelming majority of patients contemplating suicide experience depression;

Whereas the laws of such States contain no requirement for a medical attendant to be present at the time the lethal dose is taken, used, ingested, or administered to intervene in the event of medical complications;

Whereas such State laws contain no requirement that a qualified monitor be present to assure that the patient 133is knowingly and voluntarily taking, using, ingesting, or administering the lethal dose;

Whereas such State laws contain no requirement to secure lethal medication if unwanted or if death occurs before such medication is used;

Whereas such State laws do not prevent family members, heirs, or health care providers from pressuring patients to request assisted suicide;

Whereas such States qualify some patients for assisted suicide by using a broad definition of “terminal disease” and “going to die in six months or less” that includes diseases (such as diabetes or HIV) that, if appropriately treated, would not otherwise result in death within six months;

Whereas it is extremely difficult even for the most experienced doctors to accurately prognosticate a six-month life expectancy as required, making such a prognosis a prediction, not a certainty; …

Whereas there is an astounding lack of transparency in the practice of assisted suicide to the extent that State health departments and other authorities admittedly have no method of knowing if it is being practiced within the bounds of State laws and have no funding or authority to make such a determination;

Whereas some State laws actively conceal assisted suicide by directing the physician to list the cause of death as the underlying condition without reference to death by suicide;