Chapter 9

Inductors, Inductance, and PSpice Transient Analysis

INTRODUCTION

The following material on inductors and inductance is similar to that on capacitors and capacitance presented in Chap. 8. The reason for this similarity is that, mathematically speaking, the capacitor and inductor formulas are the same. Only the symbols differ. Where one has v, the other has i, and vice versa; where one has the capacitance quantity symbol C, the other has the inductance quantity symbol L; and where one has R, the other has G. It follows then that the basic inductor voltage-current formula is v = L di/dt in place of i = C dv/dt, that the energy stored is  Li2 instead of

Li2 instead of  Cv2, that, inductor currents, instead of capacitor voltages, cannot jump, that inductors are short circuits, instead of open circuits, to dc, and that the time constant is LG = L/R instead of CR. Although it is possible to approach the study of inductor action on the basis of this duality, the standard approach is to use magnetic flux.

Cv2, that, inductor currents, instead of capacitor voltages, cannot jump, that inductors are short circuits, instead of open circuits, to dc, and that the time constant is LG = L/R instead of CR. Although it is possible to approach the study of inductor action on the basis of this duality, the standard approach is to use magnetic flux.

This chapter also includes material on using PSpice to analyze transient circuits.

MAGNETIC FLUX

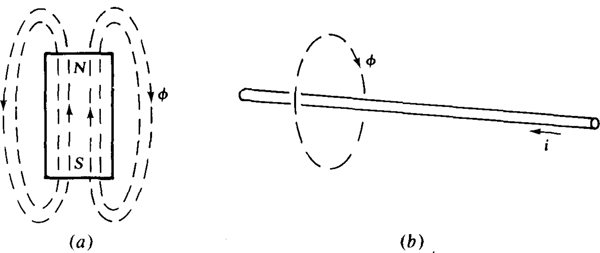

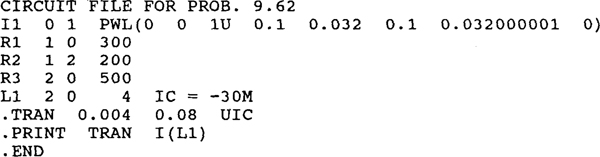

Magnetic phenomena are explained using magnetic flux, or just flux, which relates to magnetic lines of force that, for a magnet, extend in continuous lines from the magnetic north pole to the south pole outside the magnet and from the south pole to the north pole inside the magnet, as is shown in Fig. 9-la. The SI unit of flux is the weber, with unit symbol Wb. The quantity symbol is Φ for a constant flux and φ for a time-varying flux.

Fig. 9-1

Current flowing in a wire also produces flux, as shown in Fig. 9-1b. The relation between the direction of flux and the direction of current can be remembered from one version of the right-hand rule. If the thumb of the right hand is placed along, the wire in the direction of the current flow, the four fingers of the right hand curl in the direction of the flux about the wire. Coiling the wire enhances the flux, as does placing certain material, called ferromagnetic material, in and around the coil. For example, a current flowing in a coil wound on an iron cylindrical core produces more flux than the same current flowing in an identical coil wound on a plastic cylinder.

Permeability, with quantity symbol μ, is a measure of this flux-enhancing property. It has an SI unit of henry per meter and a unit symbol of H/m. (The henry, with unit symbol H, is the SI unit of inductance.) The permeability of vacuum, designated by μ0, is 0.47π μH/m. Permeabilities of other materials are related to that of vacuum by a factor called the relative permeability, with symbol μr. The relation is μ = μrμ0. Most materials have relative permeabilities close to 1, but pure iron has them in the range of 6000 to 8000, and nickel has them in the range of 400 to 1000. Permalloy, an alloy of 78.5 percent nickel and 21.5 percent iron, has a relative permeability of over 80 000.

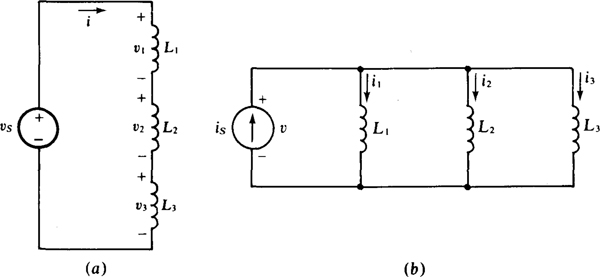

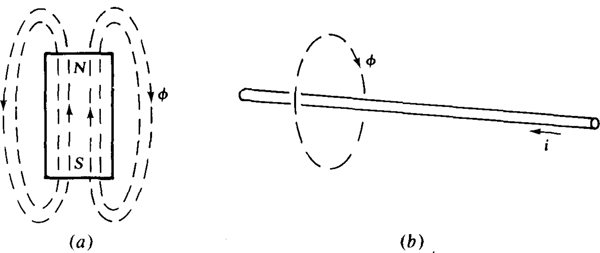

If a coil of N turns is linked by a φ amount of flux, this coil has a flux linkage of Nφ. Any change in flux linkages induces a voltage in the coil of

This is known as Faraday’s law. The voltage polarity is such that any current resulting from this voltage produces a flux that opposes the original change in flux.

INDUCTANCE AND INDUCTOR CONSTRUCTION

For most coils, a current i produces a flux linkage Nφ that is proportional to i. The equation relating Nφ and i has a constant of proportionality L that is the quantity symbol for the inductance of the coil. Specifically, Li = Nφ and L = Nφ/i. The SI unit of inductance is the henry, with unit symbol H. A component designed to be used for its inductance property is called an inductor. The terms “coil” and “choke” are also used. Figure 9-2 shows the circuit symbol for an inductor.

Fig. 9-2

The inductance of a coil depends on the shape of the coil, the permeability of the surrounding material, the number of turns, the spacing of the turns, and other factors. For the single-layer coil shown in Fig. 9-3, the inductance is approximately L = N2μA/l, where N is the number of turns of wire, A is the core cross-sectional area in square meters, l is the coil length in meters, and μ is the core permeability. The greater the length to diameter, the more accurate the formula. For a length of 10 times the diameter, the actual inductance is 4 percent less than the value given by the formula.

Fig. 9-3

INDUCTOR VOLTAGE AND CURRENT RELATION

Inductance instead of flux is used in analyzing circuits containing inductors. The equation relating inductor voltage, current, and inductance can be found from substituting Nφ = Li into v = d(Nφ)/dt. The result is v = L di/dt, with associated references assumed. If the voltage and current references are not associated, a negative sign must be included. Notice that the voltage at any instant depends on the rate of change of inductor current at that instant, but not at all on the value of current then.

One important fact from v = L di/dt is that if an inductor current is constant, not changing, then the inductor voltage is zero because di/dt = 0. With a current flowing through it, but zero voltage across it, an inductor acts as a short circuit: An inductor is a short circuit to dc. Remember, though, that it is only after an inductor current becomes constant that an inductor acts as a short circuit.

The relation v = L di/dt ≃ L Δi/Δt also means that an inductor current cannot jump. For a jump to occur, Δi would be nonzero while Δt was zero, with the result that Δi/Δt would be infinite, making the inductor voltage infinite. In other words, a jump in inductor current requires an infinite inductor voltage. But, of course, there are no sources of infinite voltage. Inductor voltage has no similar restriction. It can jump or even change polarity instantaneously. Inductor currents not jumping means that inductor currents immediately after a switching operation are the same as immediately before the operation. This is an important fact for RL (resistor-inductor) circuit analysis.

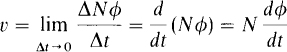

TOTAL INDUCTANCE

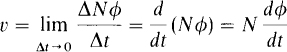

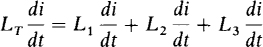

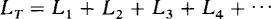

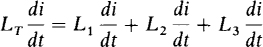

The total or equivalent inductance (LT or Leq) of inductors connected in series, as in the circuit shown in Fig. 9-4a, can be found from KVL: vs = v1 + v2 + v3. Substituting from v = L di/dt results in

Fig. 9-4

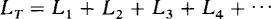

which upon division by di/dt reduces to LT = L1 + L2 + L3. Since the number of series inductors is not significant in this derivation, the result can be generalized to any number of series inductors:

which specifies that the total or equivalent inductance of series inductors is equal to the sum of the individual inductances.

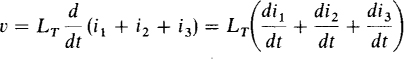

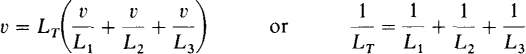

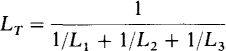

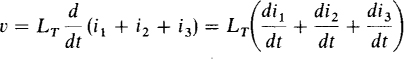

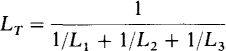

The total inductance of inductors connected in parallel, as in the circuit shown in Fig. 9-4b, can be found starting with the voltage-current equation at the source terminals: v = LTdis/dt, and substituting in is = i1 + i2 + i3:

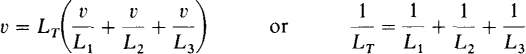

Each derivative can be eliminated using the appropriate di/dt = v/L:

which can also be written as

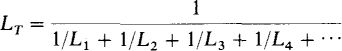

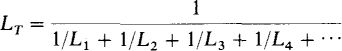

Generalizing,

which specifies that the total inductance of parallel inductors equals the reciprocal of the sum of the reciprocals of the individual inductances. For the special case of N parallel inductors having the same inductance L, this formula simplifies to LT = L/N. And for two parallel inductors it is LT = L1L2/(L1 + L2). Notice that the formulas for finding total inductances are the same as those for finding total resistances.

ENERGY STORAGE

As can be shown by using calculus, the energy stored in an inductor is

in which wL is in joules, L is in henries, and i is in amperes. This energy is considered to be stored in the magnetic field surrounding the inductor.

SINGLE-INDUCTOR DC-EXCITED CIRCUITS

When switches open or close in an RL dc-excited circuit with a single inductor, all voltages and currents that are not constant change exponentially from their initial values to their final constant values, as can be proved from differential equations. These exponential changes are the same as those illustrated in Fig. 8-5 for capacitors. Consequently, the voltage and current equations are the same: v = v (∞) + [v (0 +) – v (∞)]e–t/τ V and i = i (∞) + [i (0 +) – i (∞)]e–t/τ A. The time constant τ, though, is different. It is τ = L/RTh, in which RTh is the circuit Thévenin resistance at the inductor terminals. Of course, in one time constant the voltages and currents change by 63.2 percent of their total changes, and after five time constants they can be considered to be at their final values.

Because of the similarity of the RL and RC equations, it is possible to make RL timers. But, practically speaking, RC timers are much better. One reason is that inductors are not nearly as ideal as capacitors because the coils have resistances that are seldom negligible. Also, inductors are relatively bulky, heavy, and difficult to fabricate using integrated-circuit techniques. Additionally, the magnetic fields extending out from the inductors can induce unwanted voltages in other components. The problems with inductors are significant enough that designers of electronic circuits often exclude inductors entirely from their circuits.

PSPICE TRANSIENT ANALYSIS

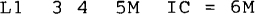

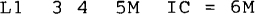

The PSpice statements for inductors and capacitors are similar to those for resistors but instead of an R, they begin with an L for an inductor and a C for a capacitor. Also, nonzero initial inductor currents and capacitor voltages must be specified in these statements. For example, the statement

specifies that inductor LI is connected between nodes 3 and 4, that its inductance is 5 mH, and that it has an initial current of 6 mA that enters at node 3 (the first specified node). The statement

specifies that capacitor C2 is connected between nodes 7 and 2, that its capacitance is 8 μF, and that it has an initial voltage of 9 V positive at node 7 (the first specified node).

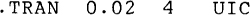

For PSpice to perform a transient analysis, the circuit file must include a statement having the form

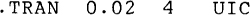

in which TSTEP and TSTOP specify times in seconds. This statement might be, for example,

in which 0.02 corresponds to TSTEP, 4 to TSTOP, and UIC to UIC, which means “use initial conditions.” The TSTEP of 0.02 s is the printing or plotting increment for the printer output, and the TSTOP of 4 s is the stop time for the analysis. A good value for TSTOP is four or five time constants. For the specified TSTEP and TSTOP times, the first output printed is for t = 0 s, the second for t = 0.02 s, the third for t = 0.04 s, and so on up to the last one for t = 4 s.

The. PRINT statement for a transient analysis is the same as that for a dc analysis except that TRAN replaces DC. The resulting printout consists of a table of columns. The first column consists of the times at which the outputs are to be specified, as directed by the specifications of the. TRAN statement. The second column comprises the values of the first specified output quantity in the. PRINT statement, which values correspond to the times of the first column. The third column comprises the values of the second specified output quantity, and so on.

With a plot statement, a plot of the output quantities versus time can be obtained. A plot statement is similar to a print statement except that it begins with.PLOT instead of.PRINT.

Improved plots can be obtained by running the graphics postprocessor Probe which is a separate executable program that can be obtained with PSpice. Probe is one of the menu items of the Control Shell. If the Control Shell is not being used, the statement. PROBE must be included in the circuit file for the use of Probe. Then, the PROBE mode may be automatically entered into after the running of the PSpice program.

With Probe, various plots can be obtained by responding to the menus that appear at the bottom of the screen. These menus are fairly self-explanatory and can be mastered with a little experimentation and trial-and-error.

For transient analysis, PSpice has five special time-dependent sources, only two of which will be considered here: the periodic-pulse source and the piecewise-linear source.

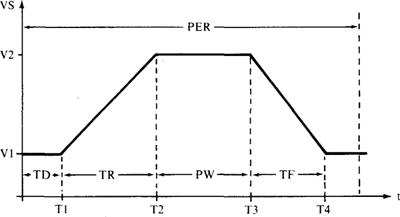

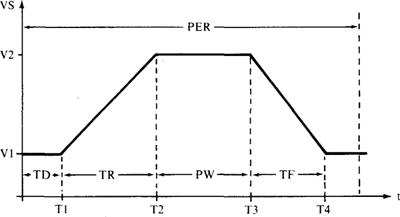

Figure 9-5 shows the general form of the pulse for the periodic-pulse source. This pulse can be periodic, but does not have to be and will not be for present purposes. The parameters signify VI for the initial value, V2 for the pulsed value, TD for time delay, TR for rise time, TF for fall time, PW for pulse width, and PER for period. For a pulse voltage source VI that is connected between nodes 2 and 3, with the positive reference at node 2, the corresponding PSpice statement has the form

Fig. 9-5

The commas do not have to be included. Also, if a pulse is not periodic, no PER parameter is specified. PSpice then assigns a default value, which is the TSTOP value in the. TRAN statement.

If a zero rise or fall time is specified, PSpice will use a default value equal to the TSTEP value in the. TRAN statement. Since this value is usually too large, nonzero but insignificant rise and fall times should be specified, such as one-millionth of a time constant.

The piecewise-linear source can be used to obtain a voltage or a current that has a waveform comprising only straight lines. It applies, for example, to the pulse of Fig. 9-5. The corresponding PSpice statement for it is

Again, the commas are optional. The entries within the parentheses are in pairs specifying the corners of the waveform, where the first specification is time (0, Tl, T2, etc.) and the second is the voltage at that time (VI, V2, V3, etc.). The times must continually increase, even if by very small increments—no two times can be exactly the same. If the last time specified in the PWL statement is less than TSTOP in the. TRAN statement, the pulse remains at its last specified value until the TSTOP time.

PWL statements can be used to obtain sources of voltage and current that have a much greater variety of waveforms than those that can be obtained with PULSE statements. However, PULSE statements apply to periodic waveforms while PWL statements do not.

Solved Problems

9.1 Find the voltage induced in a 50-turn coil from a constant flux of 104 Wb, and also from a changing flux of 3 Wb/s.

A constant flux linking a coil does not induce any voltage—only a changing flux does. A changing flux of 3 Wb/s induces a voltage of v = N dφ/dt = 50 × 3 = 150 V.

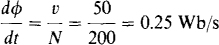

9.2 What is the rate of change of flux linking a 200-turn coil when 50 V is across the coil?

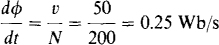

This rate of change is the dφ/dt in v = N dφ/dt:

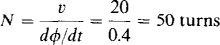

9.3 Find the number of turns of a coil for which a change of 0.4 Wb/s of flux linking the coil induces a coil voltage of 20 V.

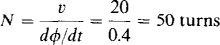

This number of turns is the N in v = N dφ/dt:

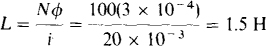

9.4 Find the inductance of a 100-turn coil that is linked by 3 × 10–4 Wb when a 20-mA current flows through it.

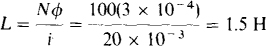

The pertinent formula is Li = Nφ. Thus,

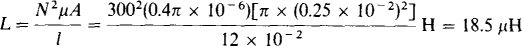

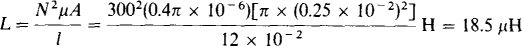

9.5 Find the approximate inductance of a single-layer coil that has 300 turns wound on a plastic cylinder 12 cm long and 0.5 cm in diameter.

The relative permeability of plastic is so nearly 1 that the permeability of vacuum can be used in the inductance formula for a single-layer cylindrical coil:

9.6 Find the approximate inductance of a single-layer 50-turn coil that is wound on a ferromagnetic cylinder 1.5 cm long and 1.5 mm in diameter. The ferromagnetic material has a relative permeability of 7000.

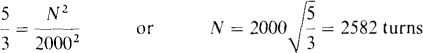

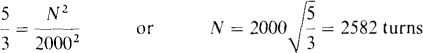

9.7 A 3-H inductor has 2000 turns. How many turns must be added to increase the inductance to 5 H?

In general, inductance is proportional to the square of the number of turns. By this proportionality,

So, 2582 – 2000 = 582 turns must be added without making any other changes.

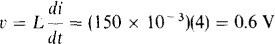

9.8 Find the voltage induced in a 150-mH coil when the current is constant at 4 A. Also, find the voltage when the current is changing at a rate of 4 A/s.

If the current is constant, di/dt = 0 and so the coil voltage is zero. For a rate of change of di/dt = 4 A/s,

9.9 Find the voltage induced in a 200-mH coil at t = 3 ms if the current increases uniformly from 30 mA at t = 2 ms to 90 mA at t = 5 ms.

Because the current increases uniformly, the induced voltage is constant over the time interval. The rate of increase is Δi/Δt, where Δi is the current at the end of the time interval minus the current at the beginning of the time interval: 90 – 30 = 60 mA. Of course, Δi is the time interval: 5 – 2 = 3 ms. The voltage is

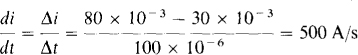

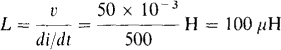

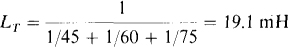

9.10 What is the inductance of a coil for which a changing current increasing uniformly from 30 mA to 80 mA in 100 μs induces 50 mV in the coil?

Because the increase is uniform (linear), the time derivative of the current equals the quotient of the current change and the time interval:

Then, from v = L di/dt,

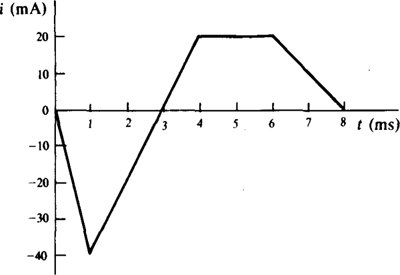

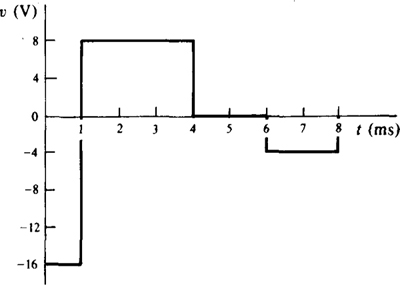

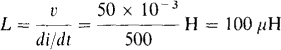

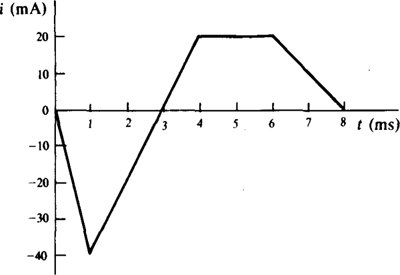

9.11 Find the voltage induced in a 400-mH coil from 0 s to 8 ms when the current shown in Fig. 9-6 flows through the coil.

Fig. 9-6

The approach is to find di/dt, the slope, from the graph and insert it into v = L di/dt for the various time intervals. For the first millisecond, the current decreases uniformly from 0 A to —40 mA. So, the slope is (—40 × 10—3 —0)/(1 × 10—3) = —40 A/s, which is the change in current divided by the corresponding change in time. The resulting voltage is v = L di/dt = (400 × 10—3)(—40) = —16 V. For the next three milliseconds, the slope is [20 × 10—3 — (—40 × 10—3)]/(3 × 10—3) = 20 A/s and the voltage is v = (400 × 10—3)(20) = 8 V. For the next two milliseconds, the current graph is horizontal, which means that the slope is zero. Consequently, the voltage is zero: v = 0 V. For the last two milliseconds, the slope is (0 — 20 × 10—3)/(2 × 10—3) = —10 A/s and v = (400 × 10—3)(—10) = –4 V.

Figure 9-7 shows the graph of voltage. Notice that the inductor voltage can jump and can even instantaneously change polarity.

Fig. 9-7

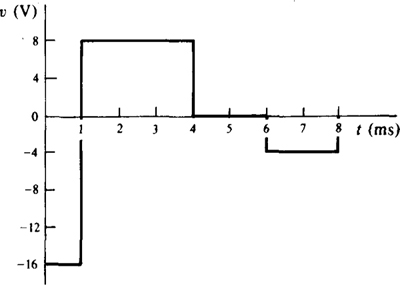

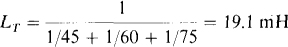

9.12 Find the total inductance of three parallel inductors having inductances of 45, 60, and 75 mH.

9.13 Find the inductance of the inductor that when connected in parallel with a 40-mH inductor produces a total inductance of 10 mH.

As has been derived, the reciprocal of the total inductance equals the sum of the reciprocals of the inductances of the individual parallel inductors:

9.14 Find the total inductance LT of the circuit shown in Fig. 9-8.

Fig. 9-8

The approach, of course, is to combine inductances starting with inductors at the end opposite the terminals at which LT is to be found. There, the parallel 70- and 30-mH inductors have a total inductance of 70(30)/(70 + 30) = 21 mH. This adds to the inductance of the 9-mH series inductor: 21 + 9 = 30 mH. This combines with the inductance of the parallel 60-mH inductor: 60(30)/(60 + 30) = 20 mH. And, finally, this adds with the inductances of the series 5- and 8-mH inductors: LT = 20 + 5 + 8 = 33 mH.

9.15 Find the energy stored in a 200-mH inductor that has 10 V across it.

Not enough information is given to determine the stored energy. The inductor current is needed, not the voltage, and there is no way of finding this current from the specified voltage.

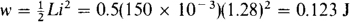

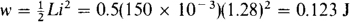

9.16 A current i = 0.32t A flows through a 150-mH inductor. Find the energy stored at t = 4 s.

At t = 4 s the inductor current is i = 0.32 × 4 = 1.28 A, and so the stored energy is

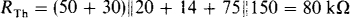

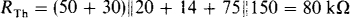

9.17 Find the time constant of the circuit shown in Fig. 9-9.

Fig. 9-9

The time constant is L/RTh, where RTh is the Thévenin resistance of the circuit at the inductor terminals. For this circuit,

and so τ = (50 × 10—3)/(80 × 103) s = 0.625 μs.

9.18 What is the energy stored in the inductor of the circuit shown in Fig. 9-9?

The inductor current is needed. Presumably, the circuit has been constructed long enough (5τ = 5 × 0.625 = 3.13 μs) for the inductor current to become constant and so for the inductor to be a short circuit. The current in this short circuit can be found from Thévenin’s resistance and voltage. The Thévenin resistance is 80 kΩ, as found in the solution to Prob. 9.17. The Thévenin voltage is the voltage across the 20-kΩ resistor if the inductor is replaced by an open circuit. This voltage will appear across the open circuit since the 14-, 75-, and 150-kΩ resistors will not carry any current. By voltage division, this voltage is

Because of the short-circuit inductor load, the inductor current is VTh/(RTh + 0) = 20/80 = 0.25 mA, and the stored energy is 0.5(50 × 10–3)(0.25 × 10–3)2 J = 1.56 nJ.

9.19 Closing a switch connects in series a 20-V source, a 2-Ω resistor, and a 3.6-H inductor. How long does it take the current to get to its maximum value, and what is this value?

The current reaches its maximum value five time constants after the switch closes: 5L/R = 5(3.6)/2 = 9 s. Since the inductor acts as a short circuit at that time, only the resistance limits the current: i (∞) = 20/2 = 10 A.

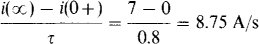

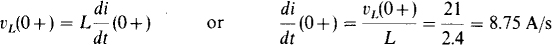

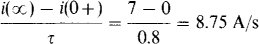

9.20 Closing a switch connects in series a 21-V source, a 3-Ω resistor, and a 2.4H inductor. Find (a) the initial and final currents, (b) the initial and final inductor voltages, and (c) the initial rate of current increase.

(a) Immediately after the switch closes, the inductor current is 0 A because it was 0 A immediately before the switch closed, and an inductor current cannot jump. The current increases from OA until it reaches its maximum value five time constants (5 × 2.4/3 = 4 s) after the switch closes. Then, because the current is constant, the inductor becomes a short circuit, and so i (∞) = V/R = 21/3 = 7 A.

(b) Since the current is zero immediately after the switch closes, the resistor voltage is 0 V, which means, by KVL, that all the source voltage is across the inductor: The initial inductor voltage is 21 V. Of course, the final inductor voltage is zero because the inductor is a short circuit to dc after five time constants.

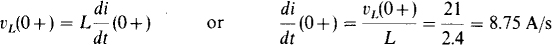

(c) As can be seen from Fig. 8-5b, the current initially increases at a rate such that the final current value would be reached in one time constant if the rate did not change. This initial rate is

Another way of finding this initial rate, which is di/dt at t = 0 +, is from the initial inductor voltage:

9.21 A closed switch connects a 120-V source to the field coils of a dc motor. These coils have 6 H of inductance and 30 Ω of resistance. A discharge resistor in parallel with the coil limits the maximum coil and switch voltages at the instants at which the switch is opened. Find the maximum value of the discharge resistor that will prevent the coil voltage from exceeding 300 V.

With the switch closed, the current in the coils is 120/30 = 4 A because the inductor part of the coils is a short circuit. Immediately after the switch is opened, the current must still be 4 A because an inductor current cannot jump—the magnetic field about the coil will change to produce whatever coil voltage is necessary to maintain this 4 A. In fact, if the discharge resistor were not present, this voltage would become great enough—thousands of volts—to produce arcing at the switch contacts to provide a current path to enable the current to decrease continuously. Such a large voltage might be destructive to the switch contacts and to the coil insulation. The discharge resistor provides an alternative path for the inductor current, which has a maximum value of 4 A. To limit the coil voltage to 300 V, the maximum value of discharge resistance is 300/4 = 75 Ω. Of course, any value less than 75 Ω will limit the voltage to less than 300 V, but a smaller resistance will result in more power dissipation when the switch is closed.

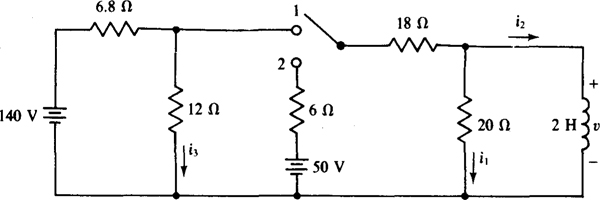

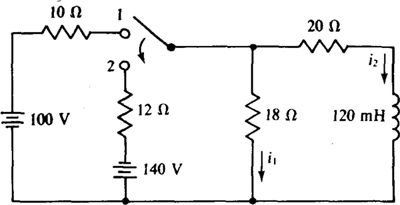

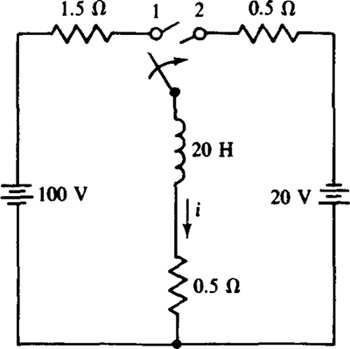

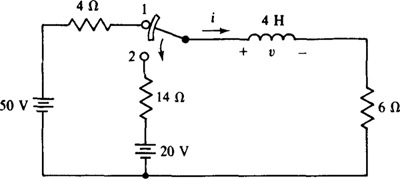

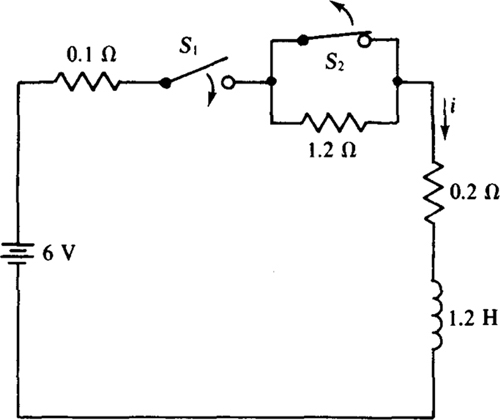

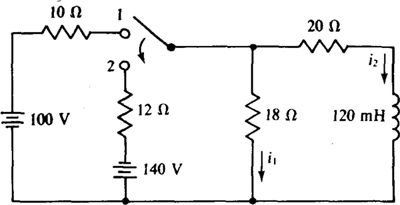

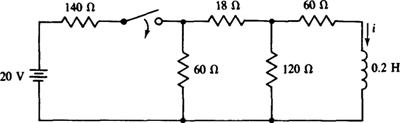

9.22 In the circuit shown in Fig. 9-10, find the indicated currents a long time after the switch has been in position 1.

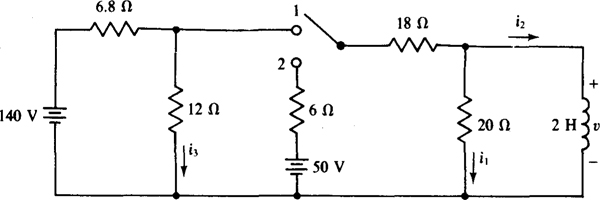

Fig. 9-10

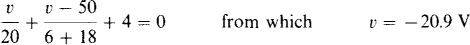

The inductor is, of course, a short circuit, and shorts out the 20-Ω resistor. As a result, i1 = 0 A. This short circuit also places the 18-Ω resistor in parallel with the 12-Ω resistor. Together they have a total resistance of 18(12)/(18 + 12) = 7.2 Ω. This adds to the resistance of the series 6.8-Ω resistor to produce 7.2 + 6.8 = 14 Ω at the source terminals. So, the source current is 140/14 = 10 A. By current division,

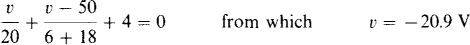

9.23 For the circuit shown in Fig. 9-10, find the indicated voltage and currents immediately after the switch is thrown to position 2 from position 1, where it has been a long time.

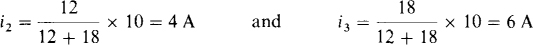

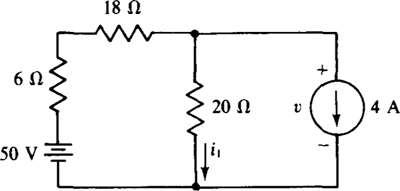

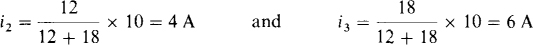

As soon as the switch leaves position 1, the left-hand side of the circuit is isolated, becoming a series circuit in which i3 = 140/(6.8 + 12) = 7.45 A. In the other part of the circuit, the inductor current cannot jump, and is 4 A, as was found in the solution to Prob. 9.22: i2 = 4 A. Since this is a known current, it can be considered to be from a current source, as shown in Fig. 9-11. Remember, though, that this circuit is valid only for the one instant of time immediately after the switch is thrown to position 2. By nodal analysis,

Fig. 9-11

And i1 = v/20 = –20.9/20 = –1.05 A.

This technique of replacing inductors in a circuit by current sources is completely general for an analysis at an instant of time immediately after a switching operation. (Similarly, capacitors can be replaced by voltage sources.) Of course, if an inductor current is zero, then the current source carries 0 A and so is equivalent to an open circuit.

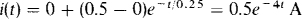

9.24 A short is placed across a coil that at the time is carrying 0.5 A. If the coil has an inductance of 0.5 H and a resistance of 2 Ω, what is the coil current 0.1 s after the short is applied?

The current equation is needed. For the basic formula i = i (∞) + [i (0 +) – i (∞)]e–t/τ, the initial current is i (0 +) = 0.5 A because the inductor current cannot jump, the final current is i (∞) = 0 A because the current will decay to zero after all the initially stored energy is dissipated in the resistance, and the time constant is τ = L/R = 0.5/2 = 0.25 s. So,

and i (0.1) = 0.5e–4(0.1) = 0.335 A.

9.25 A coil for a relay has a resistance of 30 Ω and an inductance of 2 H. If the relay requires 250 mA to operate, how soon will it operate after 12 V is applied to the coil?

For the current formula, i (0 +) = 0 A, i (∞) = 12/30 = 0.4 A, and τ = 2/30 = 1/15 s. So,

The time at which the current is 250 mA = 0.25 A can be found by substituting 0.25 for i and solving for t:

Taking the natural logarithm of both sides results in

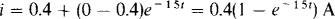

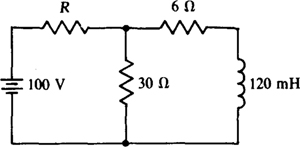

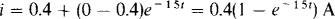

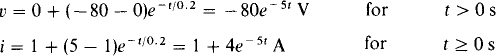

9.26 For the circuit shown in Fig. 9-12, find v and i for t > 0 s if at t = 0 s the switch is thrown to position 2 after having been in position 1 for a long time.

Fig. 9-12

The switch shown is a make-before-break switch that makes contact at the beginning of position 2 before breaking contact at position 1. This temporary double contacting provides a path for the inductor current during switching and prevents arcing at the switch contacts. To find the voltage and current, it is only necessary to get their initial and final values, along with the time constant, and insert these into the voltage and current formulas. The initial current i (0 +) is the same as the inductor current immediately before the switching operation, with the switch in position 1: i (0 +) = 50/(4 + 6) = 5 A. When the switch is in position 2, this current produces initial voltage drops of 5 × 6 = 30 V and 14 × 5 = 70 V across the 6- and 14-Ω resistors, respectively. By KVL, 30 + 70 + v (0 +) = 20, from which v (0 +) = = – 80 V. For the final values, clearly v (∞) = 0 V and i (∞) = 20/(14 + 6) = 1 A. The time constant is 4/20 = 0.2 s. With these values inserted, the voltage and current formulas are

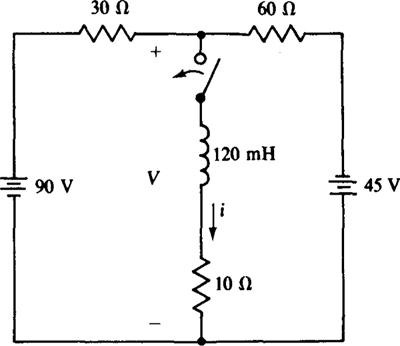

9.27 For the circuit shown in Fig. 9-13, find i for t ≥ 0 s if the switch is closed at t = 0 s after being open for a long time.

Fig. 9-13

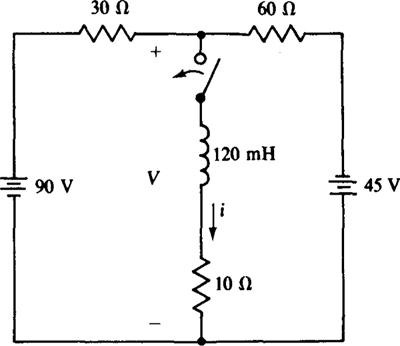

A good approach is to use the Thévenin equivalent circuit at the inductor terminals. The Thévenin resistance is easy to find because the resistors are in series-parallel when the sources are deactivated: RTh = 10 + 30||60 = 30 Ω. The Thévenin voltage is the indicated V with the center branch removed because replacing the inductor by an open circuit prevents the center branch from affecting this voltage. By nodal analysis,

So, the Thévenin equivalent circuit is a 30-Ω resistor in series with a 45-V source, and the polarity of the source is such as to produce a positive current i. With the Thévenin circuit connected to the inductor, it should be obvious that i (0 +) = 0 A, i (∞) = 45/30 = 1.5 A, τ = (120 × 10–3)/30 = 4 × 10–3s, and 1/τ = 250. These values inserted into the current formula result in i = 1.5 – 1.5e– 250t A for t ≥ 0 s.

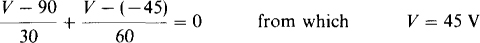

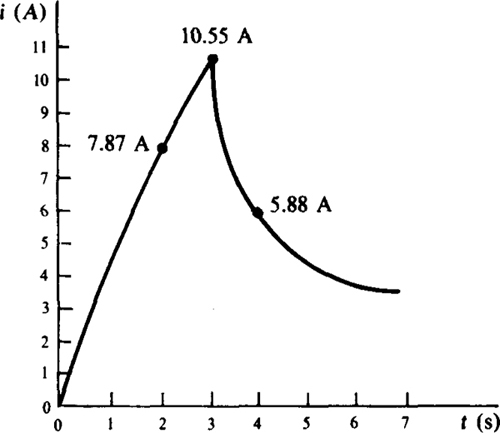

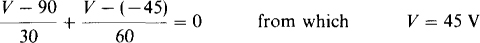

9.28 In the circuit shown in Fig. 9-14, switch S1 is closed at t = 0 s, and switch S2 is opened at t = 3 s. Find i (2) and i (4), and make a sketch of i for t ≥ 0 s.

Fig. 9-14

Two equations for i are needed: one with both switches closed, and the other with switch S1 closed and switch S2 open. At the time that S1 is closed, i (0 +) = 0 A, and i starts increasing toward a final value of i (∞) = 6/(0.1 + 0.2) = 20 A. The time constant is 1.2/(0.1 + 0.2) = 4 s. The 1.2-Ω resistor does not affect the current or time constant because this resistor is shorted by switch S2. So, for the first three seconds, i = 20 – 20e–t/4 A, and from this, i (2) = 20 – 20e–2/4 = 7.87 A.

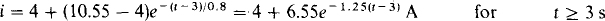

After switch S2 opens at t = 3 s, the equation for i must change because the circuit changes as a result of the insertion of the 1.2-Ω resistor. With the switching occurring at t = 3 s instead of at t = 0 s, the basic formula for i is i = i (∞) + [i (3 +) – i (∞)–]e–(t – 3)/τ A. The current i (3 +) can be calculated from the first i equation since the current cannot jump at t = 3 s: i (3 +) = 20 – 20e–3/4 = 10.55 A. Of course, i (∞) = 6/(0.1 + 1.2 + 0.2) = 4 A and τ = 1.2/1.5 = 0.8 s. With these values inserted, the current formula is

from which i (4) = 4 + 6.55e–1.25(4 – 3) = 5.88 A.

Figure 9-15 shows the graph of current based on the two current equations.

Fig. 9-15

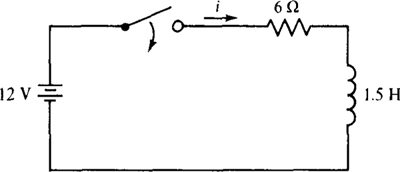

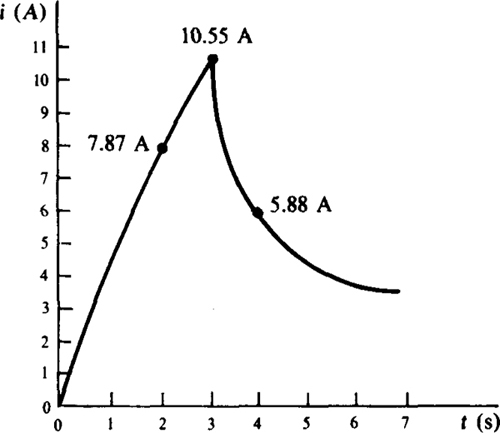

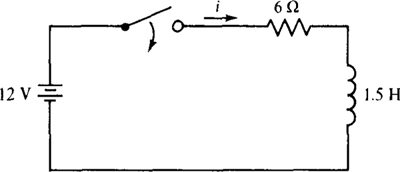

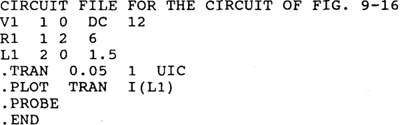

9.29 Use PSpice to find the current i in the circuit of Fig. 9-16.

Fig. 9-16

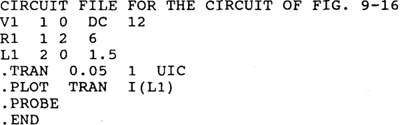

The time constant is τ = L/R = 1.5/6 = 0.25 s. So, a suitable value for TSTOP in the. TRAN statement is 4τ = 1 s because the current is at approximately its final value then. The number of time steps will be selected as only 20, for convenience. Then, TSTEP in the. TRAN statement is TSTOP/20 = 0.05 s. Even though the initial inductor current is zero, a UIC specification is needed in the. TRAN statement. Otherwise, only the final value of 2 A will be obtained. A. PLOT statement will be included to obtain a plot. Because a table of values will automatically be obtained with this plot, no. PRINT statement is needed. Probe will also be used to obtain a plot to demonstrate the superiority of its plot. Following is a suitable circuit file.

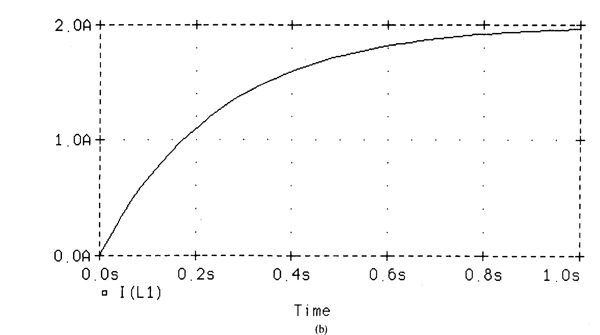

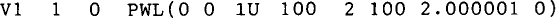

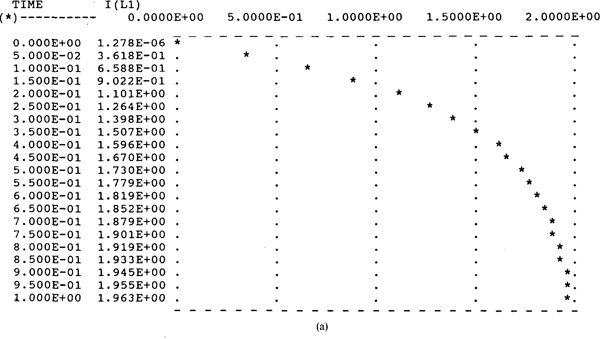

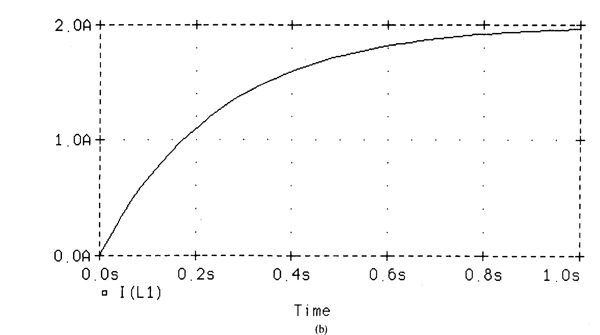

When PSpice is run with this circuit file, the plots of Figs. 9-17a and 9-17b are obtained from the. PLOT and. PROBE statements, respectively. The Probe plot required a little additional effort in responding to the menus at the bottom of the screen. The first column at the left-hand side of Fig. 9-17a gives the times at which the current is evaluated, and the second column gives the current values at these times. The values are plotted with the time axis being the vertical axis and the current axis the horizontal axis. The Probe plot of Fig. 9-17b is obviously superior in appearance, but it does not contain the current values explicitly at the various times as does the table with the other plot. But values can be obtained from the Probe plot by using the cursor feature which is included in the menus.

Fig. 9-17

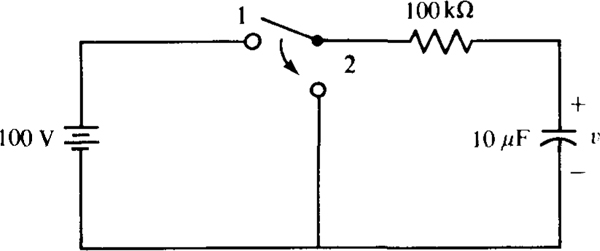

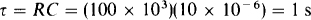

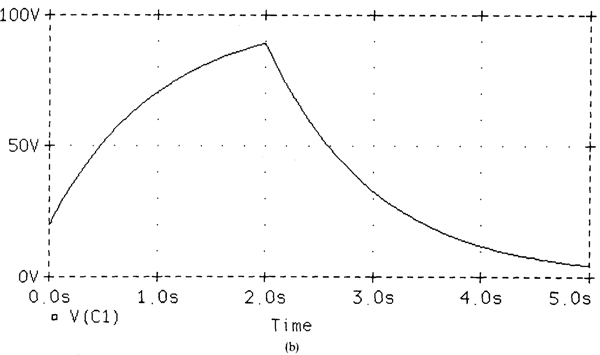

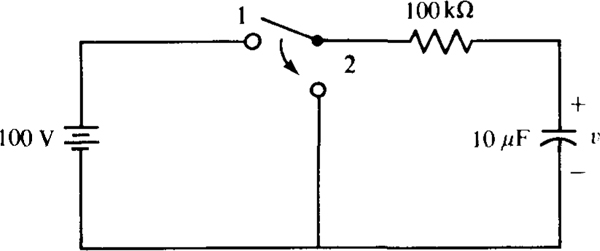

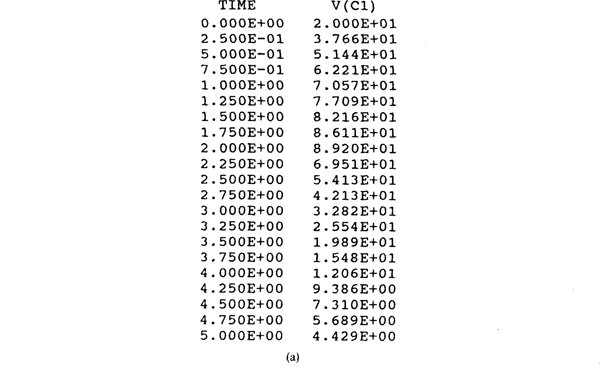

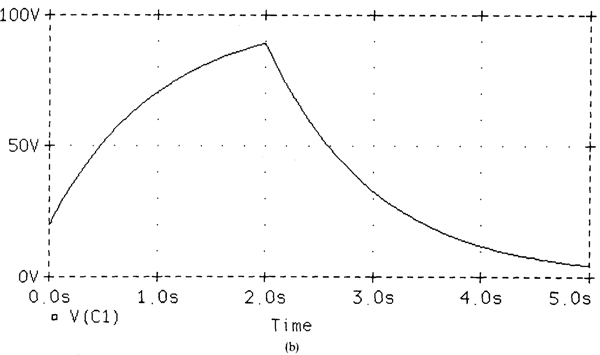

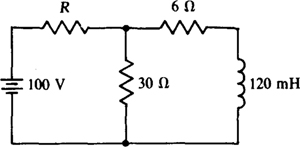

9.30 In the circuit of Fig. 9-18, the switch is moved to position 1 at t = 0 s and then to position 2 at t = 2 s. The initial capacitor voltage is v (0) = 20 V. Find v for t ≥ 0 s by hand and also by using PSpice.

Fig. 9-18

The time constant is

Also, v (0) = 20 V, and for the switch in position 1 the final voltage is v (∞) = 100 V. Therefore,

At t = 2 s,

So, for t ≥ 2 s, v (t) = 89.2e–(t – 2) = 658.9e –t V.

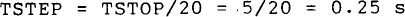

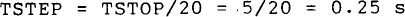

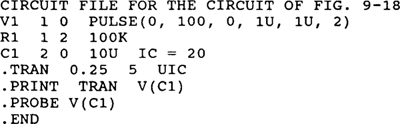

For the PSpice circuit file, a suitable value for TSTOP is 5 s, which is three time constants after the second switching. This time is not critical, of course, and perhaps a preferable time would be 6 s, which is four time constants after the second switching. But 5 s will be used. The number of time steps is not critical either. For convenience, 20 will be used. Then,

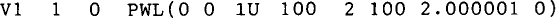

To obtain the effects of switching, a PULSE source will be used, with 0 V being one value and 100 V the other. The time duration of the 100 V is 2 s, of course. Alternatively, a PWL source could be used. A .PRINT statement will be included to generate a table of values, and a.PROBE statement to obtain a plot. Following is a suitable circuit file.

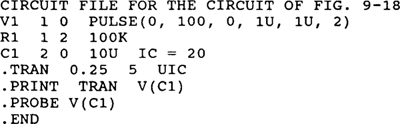

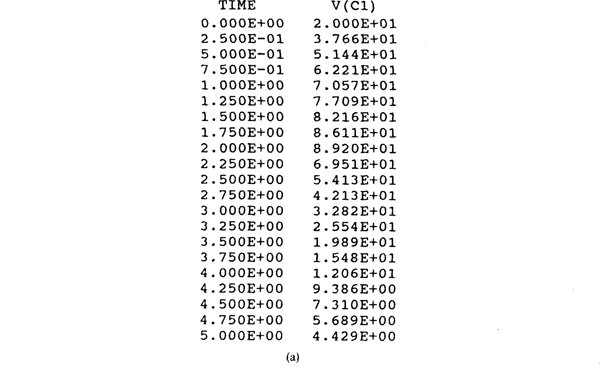

If a PWL source were used instead of the PULSE source, the VI statement would be

The V(C1) specification is included in the.PROBE statement so that Probe will store the V(2) node voltage under this name. Alternatively, this specification could be omitted and a trace of V(2) specified in the Probe mode.

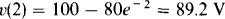

When PSpice is run with this circuit file, the. PRINT statement generates the table of Fig. 9-19a, and the.PROBE statement generates Fig. 9-19b. Notice that the voltage value at t = 2 s is 89.2 V, which completely agrees with the value obtained by hand.

Fig. 9-19

Supplementary Problems

9.31 Find the voltage induced in a 500-turn coil when the flux changes uniformly by 16 × 10–5 Wb in 2 ms.

Ans. 40 V

9.32 Find the change in flux linking an 800-turn coil when 3.2 V is induced for 6 ms.

Ans. 24 μWb

9.33 What is the number of turns of a coil for which a flux change of 40 × 10–6 Wb in 0.4 ms induces 70 V in the coil?

Ans. 700 turns

9.34 Find the flux linking a 500-turn, 0.1-H coil carrying a 2-mA current.

Ans. 0.4 μWb

9.35 Find the approximate inductance of a single-layer, 300-turn air-core coil that is 3 in long and 0.25 in in diameter.

Ans. 47 μH

9.36 Find the approximate inductance of a single-layer 500-turn coil that is wound on a ferromagnetic cylinder that is 1 in long and 0.1 in in diameter. The ferromagnetic material has a relative permeability of 8000.

Ans. 0.501 H

9.37 A 250-mH inductor has 500 turns. How many turns must be added to increase the inductance to 400 mH?

Ans. 132 turns

9.38 The current in a 300-mH inductor increases uniformly from 0.2 to 1 A in 0.5 s. What is the inductor voltage for this time?

Ans. 0.48 V

9.39 If a change in current in a 0.2-H inductor produces a constant 5-V inductor voltage, how long does the current take to increase from 30 to 200 mA?

Ans. 6.8 ms

9.40 What is the inductance of a coil for which a changing current increasing uniformly from 150 to 275 mA in 300 μs induces 75 mV in the coil?

Ans. 180 μH

9.41 Find the voltage induced in a 200-mH coil from 0 to 5 ms when a current i described as follows flows through the coil: i = 250t A for 0 s ≤ t ≤ 1 ms, i = 250 mA for 1 ms ≤ t ≤ 2 ms, and i = 416 – 83 000t mA for 2 ms ≤ t ≤ 5 ms.

Ans. v = 50 V for 0 s < t < 1 ms; 0 V for 1 ms < t < 2 ms; – 16.6 V for 2 ms < t < 5 ms

9.42 Find the total inductance of four parallel inductors having inductances of 80, 125, 200, and 350 mH.

Ans. 35.3 mH

9.43 Find the total inductance of a 40-mH inductor in series with the parallel combination of a 60-mH inductor, an 80-mH inductor, and a 100-mH inductor.

Ans. 65.5 mH

9.44 A 2-H inductor, a 430-Ω resistor, and a 50-V source have been connected in series for a long time. What is the energy stored in the inductor?

Ans. 13.5 mJ

9.45 A current i = 0.56t A flows through a 0.5-H inductor. Find the energy stored at t = 6 s.

Ans. 2.82 J

9.46 What is the energy stored by the inductor in the circuit shown in Fig. 9.20 if R = 20 Ω?

Fig. 9-20

Ans. 667 mJ

9.47 Find the time constant of the circuit shown in Fig. 9-20 for R = 90 Ω.

Ans. 4.21 ms

9.48 How long after a short circuit is placed across a coil carrying a current of 2 A does the current go to zero if the coil has 1.2 H of inductance and 40 Ω of resistance? Also, how much energy is dissipated?

Ans. 0.15 s, 2.4 J

9.49 A switch closing connects in series a 10-V source, an 8.2-Ω resistor, and a 1.2-H inductor. How long does the current take to reach its maximum value, and what is this value?

Ans. 732 ms, 1.22 A

9.50 In closing, a switch connects a 100-V source with 5 Ω of internal resistance across the parallel combination of a 20-Ω resistor and a 0.4-H inductor. What are the initial and final source currents, and what is the initial rate of inductor current increase?

Ans. 4 A, 20 A, 200 A/s

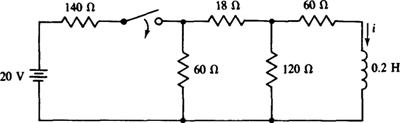

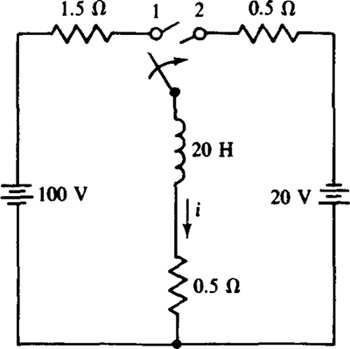

9.51 In the circuit shown in Fig. 9-21, the switch is thrown at t = 0 s from an open position to position 1. Find the indicated currents at t = 0+ s and also at a long time later.

Fig. 9-21

Ans. i1(0 +) = 3.57 A, i2(0 +) = 0 A, i1(∞) = 2.7 A, i2(∞) = 2.43 A

9.52 In the circuit shown in Fig. 9-21, the switch is thrown at t = 0 s to position 2 from position 1 where it has been a long time. Find the indicated currents at t = 0+ s and also at a long time later.

Ans. i1(0 +) = –5.64 A, i2(0 +) = 2.43 A, i1(∞) = –3.43 A, i2(∞) = –3.09 A

9.53 A switch closing at t = 0 s connects a 20-mH inductor to a 40-V source that has 10 Ω of internal resistance. Find the inductor voltage and current for t > 0 s.

Ans. v = 40e–500 t V, i = 4(1 – e– 500t) A

9.54 A switch closing at t = 0 s connects a 100-V source with a 15-Ω internal resistance to a coil that has 200 mH of inductance and 5 Ω of resistance. Find the coil voltage for t > 0 s.

Ans. 25 + 75e–100t V

9.55 A coil for a relay has a resistance of 20 Ω and an inductance of 1.2 H. The relay requires 300 mA to operate. How soon will the relay operate after a 20-V source with 5 Ω of internal resistance is applied to the coil?

Ans. 22.6 ms

9.56 For the circuit shown in Fig. 9-22, find i as a function of time after the switch closes at t = 0 s.

Fig. 9-22

Ans. 0.04(1 – e–500t) A

9.57 Assume that the switch in the circuit shown in Fig. 9-22 has been closed a long time. Find i as a function of time after the switch opens at t = 0 s.

Ans. 0.04e–536t A

9.58 In the circuit shown in Fig. 9-23, the switch is thrown to position 1 at t = 0 s after being open a long time. Then it is thrown to position 2 at t = 2.5 s. Find i for t ≥ 0 s.

Fig. 9-23

Ans. 50(1 – e0.1t) A for 0 s ≤ t ≤ 2.5 s; –20 + 31.1e–0.05(t – 2.5) A for t ≥ 2.5 s

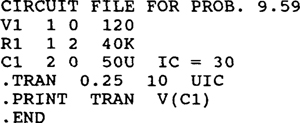

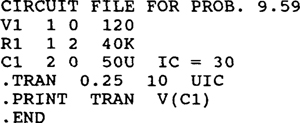

9.59 Obtain the expression for the response for t ≥ 0 s corresponding to the following circuit file. Also, from this expression, determine the 11th value that will be printed.

Ans. 120 – 90e–0.5t V, 94.2 V

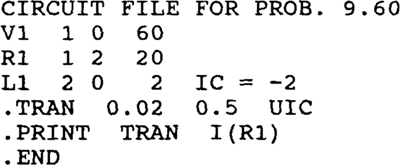

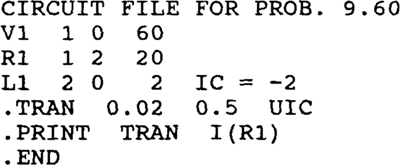

9.60 Obtain the expression for the response for t ≥ 0 s corresponding to the following circuit file. Also, from this expression, determine the 9th value that will be printed.

Ans. 3 – 5e–10t A, 1.99 A

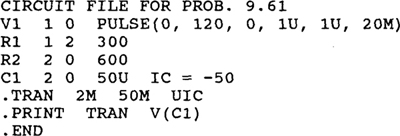

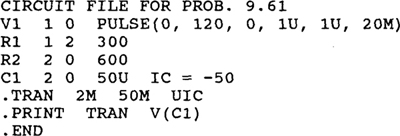

9.61 Obtain the expressions for the response for t ≥ 0 s corresponding to the following circuit file. Also, from these expressions, determine the 17th value that will be printed.

Ans. 80 – 130e–100t V for 0 s ≤ t ≤ 0.02 s; 62.4e–100(t – 0.02) V for t ≥ 0.02 s; 18.8V

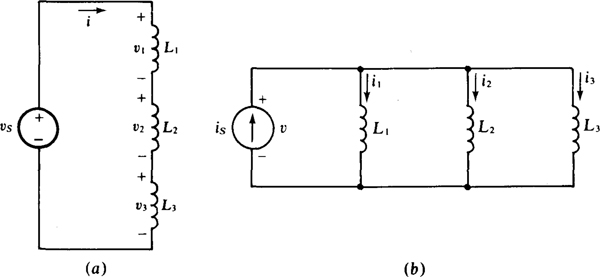

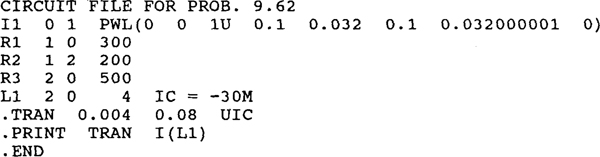

9.62 Obtain the expressions for the response for t ≥ 0 s corresponding to the following circuit file. Also, from these expressions, determine the 13th value that will be printed.

Ans. 60–90e–62.5t mA for 0 s ≤ t ≤ 32 ms; 47.8e–62.5(t – 0.032) mA for t ≥ 32 ms; 17.6 mA

Li2 instead of

Li2 instead of  Cv2, that, inductor currents, instead of capacitor voltages, cannot jump, that inductors are short circuits, instead of open circuits, to dc, and that the time constant is LG = L/R instead of CR. Although it is possible to approach the study of inductor action on the basis of this duality, the standard approach is to use magnetic flux.

Cv2, that, inductor currents, instead of capacitor voltages, cannot jump, that inductors are short circuits, instead of open circuits, to dc, and that the time constant is LG = L/R instead of CR. Although it is possible to approach the study of inductor action on the basis of this duality, the standard approach is to use magnetic flux.