29

The Supporting Cast’s Shining Moments

More than twenty years elapsed between the premiere of Star Trek and the debut of its first sequel series, Star Trek: The Next Generation. Television underwent many changes during the interim. One of the most profound was the emergence of hit series such as The Waltons (1972–81), Hill Street Blues (1981–87), and Cheers (1982–93), which were designed to feature a large ensemble of actors rather than one or two stars. This casting approach opened additional story possibilities for screenwriters and provided reassurance to producers, since the show could continue even if key cast members departed or died—as happened over the lifetime of all three of those programs. Star Trek’s Desilu-produced sister series Mission: Impossible was a forerunner of this ensemble approach.

The Next Generation (and every other Star Trek series to follow the original) was also an ensemble cast program. While the primary focus remained on Captain Picard (Patrick Stewart), individual installments often highlighted supporting characters such as Commander Data (Brent Spiner), engineer Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton), and Lieutenant Worf (Michael Dorn). Within the first few minutes, viewers could tell if this week’s installment would be a Geordi episode, a Worf episode, a Counselor Troi (Marina Sirtis) episode, and so on.

Nothing like this ever happened on the classic Star Trek series. Fans can only daydream about the tantalizing possibilities of the Uhura episodes or Sulu adventures that never were.

Most TV shows of the 1950s and ’60s were built around one or two stars and a revolving assortment of guest actors. On many programs, the recurring supporting characters amounted to little more than window dressing. Star Trek largely adhered to this traditional structure. Although it boasted three stars (William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, and DeForest Kelley), its supporting players weren’t guaranteed work in every episode, and their parts often were limited to glorified bits (little beyond the familiar “Aye, aye, Captain”). And William Shatner, out of both personal insecurity and a misguided sense of responsibility to “carry” the show, often tried to further reduce the screen time of the supporting cast.

All of this makes it difficult to fairly assess the capabilities and contributions of James Doohan, George Takei, Nichelle Nichols, Walter Koenig, and Majel Barrett. Fabled acting instructor Constantin Stanislavski once said that “there are no small parts, only small actors.” But there are only so many different ways to deliver the line “Hailing frequencies open, Captain.” Perhaps the best thing that can be said for Star Trek’s supporting players is that on those rare occasions when the script gave them something meaningful to play, they played it well. In the end, that’s all you can ask of any actor.

James Doohan

Like the character he played, “One-Take Doohan” was noted for his reliability.

If Star Trek had a fourth lead it was (or at least should have been) James Doohan, the busiest member of the supporting cast. Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott not only worked mechanical miracles on an almost weekly basis but was often assigned to landing parties, or else left in command of the ship while Kirk and Spock were away. Whatever the scenario, Doohan’s work was never less than exemplary, earning him the nickname “One-Take Doohan.” And Scotty became the show’s most popular supporting character. All of which is even more impressive considering that Gene Roddenberry tried to fire the actor after his first appearance.

Doohan was one of several actors hired for Star Trek’s second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” After NBC purchased the series, the show underwent a final round of recasting. Actors Lloyd Haynes (communications specialist Alden), Andrea Dromm (Yeoman Smith), and Paul Fix (Dr. Piper) were all jettisoned because Roddenberry was unsatisfied with their performances. Although he liked Doohan’s acting, Roddenberry considered Scotty a superfluous character and tried to cut him as a cost-saving measure. But Doohan was already under contract, and the forceful intervention of his agent, Paul Wilkins, kept the actor (and Scotty) on the show.

Doohan went on to appear in sixty-three of the series’ seventy-nine installments. Like the rest of the supporting cast, his shining moments are scattered across numerous adventures—a scene here and a scene there. Considered as a body of work, however, these performances constitute an impressive achievement. It was Doohan’s idea to make the character a Scotsman, and the actor’s mastery of accents brought a distinctive texture to the role that helped Scotty stand out. Doohan’s work was so skillful that he was able, through subtle alterations to Scotty’s brogue, to shift easily from drama to comedy as teleplays demanded.

The actor’s comedic gifts were best showcased in “The Trouble with Tribbles,” especially during the buildup to Scotty’s barroom brawl with Klingon officer Korax (Michael Pataki) while on shore leave at Space Station K-7. At first, Doohan seems relaxed and level-headed, calming Ensign Chekov when Korax, bent on picking a fight, insults Captain Kirk. But Doohan slowly steams up when Korax begins to denigrate the Enterprise, calling the ship a “saggy old rust-bucket” and comparing it with a garbage scow. “Laddy, don’t ye think ye should … rephrase that?” Doohan seethes, narrowing his eyes. Finally, he rises from his chair, wearing a satisfied grin, and lands a haymaker to the Klingon’s jaw. A melee quickly ensues. Doohan is also highly amusing in the following scene, in which a sheepish Scotty struggles to explain to Captain Kirk how the brawl began. Finally, according to Doohan, it was his idea to flip the verb from “trouble” to “tribble” in Scotty’s famous closing line (“where they’ll be no tribble at all”).

As funny and charming as Doohan could be, however, Star Trek was far more reliant on the actor’s dramatic chops. His deft, matter-of-fact handling of the show’s technospeak made Scotty (along with Mr. Spock) a go-to character for explaining foundational concepts such as the warp drive and transporter, helping shore up the credibility of the emerging Star Trek universe. The importance of this can’t be overstated, since most television audiences of 1960s were not well versed in science fiction. Screenwriters usually disguised this exposition within dramatic scenarios—for instance, with the Enterprise trapped in a decaying orbit during “The Naked Time” (in which Doohan uttered his famous line, “I canna change the laws o’ physics!”), or with Scotty struggling to bring the battle-damaged Starship Constellation back on line in “The Doomsday Machine.”

The actor’s self-assured performances in episodes such as “A Taste of Armageddon” and “Friday’s Child,” in which Scotty is left in charge of the ship, helped hide one of the show’s glaring logical weaknesses—namely, why were the captain and first officer constantly sent together on dangerous away missions? With Scotty in command, the ship always seemed to be in good hands. “I thought I ran the ship beautifully, to tell the truth,” Doohan wrote in his autobiography Beam Me Up, Scotty.

Doohan’s most searing dramatic performance came in “Wolf in the Fold,” in which Scotty is accused of butchering three young women while on shore leave on planet Argelius II. The crime was actually committed by a noncorporeal being that feeds on fear, but because the creature also blacked out Scotty’s memory, the engineer comes to doubt his own innocence. Presented with the murder knife and pressed for information about the first killing, Doohan chokes up, shakes his head, and stammers, “I don’t remember another thing!” with obvious frustration and terror. He seems even more desperate—wide-eyed, stunned—after the second killing. “I can’t even believe this is really happenin’,” Doohan almost weeps. Screenwriter Robert Bloch’s horror-tinged scenario works in part because Doohan convinces us that Scotty—whom audiences had grown to love—is in real danger and real pain.

In “The Lights of Zetar”—the closest thing to a Scotty episode ever produced—his character falls in love with a young lieutenant, Mira Romaine (Jan Shutan). Scotty’s behavior in this episode is extremely uncharacteristic (even Doohan, in his autobiography, dismissed the story’s romantic subplot as “a matter of plot contrivance”), but this didn’t prevent the actor from delivering a standout portrayal. The love-struck engineer seems distracted, twice abandoning his post to look after his girlfriend. But Doohan moons over Shutan so sweetly (addressing her tenderly, wearing an almost dazed-looking grin, eyes sparkling) that the audience attributes these lapses to romantic exuberance rather than sloppy screenwriting.

Nichelle Nichols

Lieutenant Uhura participated in so few away missions that Nichelle Nichols had to stand in front of a shot from “The Cage” to create this publicity still.

Although she appeared in more installments than Doohan (sixty-eight in all) Nichelle Nichols had far fewer opportunities to shine. She spent most of her time seated at Lieutenant Uhura’s communications console, dutifully reporting that hailing frequencies were open in episode after episode. Although she and Roddenberry had worked out an elaborate backstory for Uhura (including the idea that she led a large team of communications technicians and specialists), screenwriters made little use of this material. Nichols grew so dissatisfied that she decided to leave the show following its first season, only to be talked out of quitting by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who met the actress at a party and urged her to reconsider.

Still, Nichols made the most of her rare opportunities to leave the bridge. She left a stunning impression in “Mirror, Mirror,” not only because of her striking Mirror Universe costume (a sexy two-piece, bare midriff outfit) but due to her subtle and evocative work in a pair of unforgettable scenes. Accidentally transported onto an evil parallel version of the Enterprise along with the rest of an ill-fated away team, Uhura must tap into the ship’s computers and learn all she can about this twisted universe. That means taking her station on the bridge alongside the creepy alter egos of her usual crewmates, a prospect which gives her pause. She halts before leaving the relative safety of sick bay. “Captain, I …” she begins, but her words trail off. Nichols’s body language and half-choked delivery make clear that the frightened Uhura needs a moment to steel her nerves for the potentially dangerous assignment. She plays this moment of hesitation with authenticity and dignity, seeming frightened without undercutting her character’s inner strength. That strength rises to the fore later, when Uhura distracts the evil Mirror Sulu by coming on to him, then smacking him across the face. “You take a lotta chances,” the frustrated Sulu growls. “So do you, Mister,” Nichols hisses in response, pulling a dagger from her boot and backing away warily. “Mirror, Mirror” was an excellent outing for most members of the cast—Leonard Nimoy, George Takei, and Walter Koenig are also particularly good here—but no one was more impressive than Nichols. “Mirror, Mirror” remains the single episode that best encapsulates all the qualities she brought to her role—an appealing blend of self-confidence, vulnerability, and sex appeal that made Uhura one of the show’s most beloved characters.

Those same qualities are on display in “Plato’s Stepchildren,” the episode in which she and Shatner locked lips in TV’s first interracial kiss. Once again, Nichols’s believable, heartfelt portrayal prevented her character from seeming demeaned or diminished, even though she’s forced by superpowered aliens to behave uncharacteristic ways. Like Doohan’s work in “The Lights of Zetar,” Nichols’s performance in the otherwise unimpressive “Plato’s Stepchildren” was a triumph of actor over material.

In “The Trouble with Tribbles,” Nichols accentuated Uhura’s tender side. “Oooh, it’s adorable! What is it?” Nichols asks, as Uhura holds a tribble for the first time. Then she brings the cooing creature to ear and giggles. “Listen, it’s purring!” Her glowing smile and almost musical laughter charms viewers every bit as much as the tribble. On those rare occasions, such as in “Charlie X,” when the scenario afforded Nichols a chance to sing, Star Trek was better for it. (For more on Nichols’s musical contributions, see Chapter 24, “Then Play On.”) Despite the actress’s best efforts, however, the Uhura character was never developed to its full potential during the run of the classic Star Trek series. In the animated adventure “The Lorelei Signal,” however, Uhura (out of necessity, since the Enterprise’s male leadership has been taken prisoner by a race of space sirens) takes command and mounts a rescue mission, saving the lives of Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Scotty, and Sulu in a nick of time. Too bad stories like this never unfolded on the live-action series!

George Takei

Like Nichols, George Takei piled up a lot of appearances (fifty-two altogether) but only a smattering of episodes that gave him the chance to leave his station on the bridge. Yet, even when his dialogue was limited to “Aye, aye, Captain” or repeating “Warp factor two,” Takei found small ways of expressing himself. He mastered a collection of facial expressions that revealed helmsman Sulu’s state of mind—raising an eyebrow and half-grinning at Chekov (or another navigator) to indicate relief or confidence, furrowing his brow and looking straight ahead to express anxiety, and so forth. He also worked out a consistent pattern of switches he flipped whenever Sulu put the starship in motion, rather than simply pressing buttons randomly. These small, often overlooked choices quietly fleshed out the character and enhanced the believability of the show.

Takei’s single most memorable moment came early on, in Season One’s “The Naked Time.” Under the influence of an inhibition-loosening disease, Sulu strips to his bare chest, takes up a fencing foil, and begins charging through the corridors of the Enterprise like some demented Robin Hood, even bounding onto the bridge to “rescue” Uhura and challenge Captain Kirk. Takei’s sheer exuberance makes this sequence the most memorable scene in a very good episode. Indeed, it ranks among the most unforgettable moments in any Star Trek adventure. Writer-producer John Meredith Lucas approached Takei while writing the script for “The Naked Time” and asked the actor if he could handle a sword. Naturally Takei lied and said he could, then immediately enrolled in a fencing class. The actor also dieted and worked out to tone his physique for his bare-chested romp. “After so many episodes of being adhered to the bridge console, this [episode] sounded absolutely delicious,” Takei wrote of in his autobiography To the Stars.

Unfortunately, after “The Naked Time,” it was back to the usual diet of scraps for Takei, who fell victim to bad luck as the show’s first season wound down and its second campaign began. Originally, he was to be featured prominently in the Season One episode “This Side of Paradise,” but in rewrites the story’s romantic subplot was taken away from Sulu and given to Spock. Then Takei agreed to appear in the John Wayne war picture The Green Berets during the summer break between Trek’s first two seasons. When shooting on the movie ran over schedule, Takei found himself trapped in rural Georgia while production of Star Trek resumed in Los Angeles. As a result, a handful of teleplays with scenes written to spotlight Sulu were retooled, with those moments reassigned to the Enterprise’s new navigator, Ensign Chekov (Walter Koenig).

Fortunately, Takei returned to the fold just in time for “Mirror, Mirror,” in which he delivered another indelible performance as the lecherous, scar-faced Mirror Universe Sulu, merciless security chief of the Imperial starship Enterprise. On the bridge, Takei (looking sweaty and disheveled) saunters over to Lieutenant Uhura’s station, leers down her blouse, and then cups her chin in his hand. “Still no interest, Uhura?” he asks. “I could make you change your mind.” Takei’s harsh demeanor makes this line sound like a threat rather than an attempted seduction. Later, the ruthless Sulu hatches a scheme to assassinate both Kirk and Spock, twirling a dagger in his hand as he coolly explains his plan. Takei seems more aroused by the prospect of murdering his superiors than he did in his earlier scenes with Nichols, adding to the subtly unnerving quality of his performance. All of which made Takei’s Evil Sulu by far the most intimidating of the episode’s Mirror Universe characters.

The richness of his performances in “The Naked Time” and “Mirror, Mirror” display versatility and nuance that went untapped in most of Takei’s other episodes. The full range of the actor’s talents, lamentably, remained underutilized.

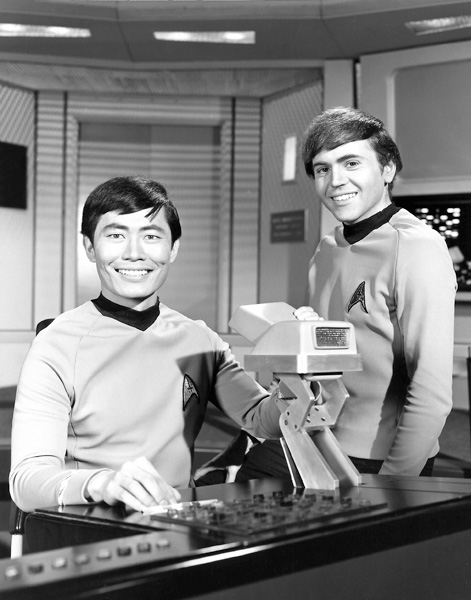

Even though George Takei initially resented Walter Koenig, the two eventually became close friends.

Walter Koenig

Koenig may not have been Star Trek’s most talented performer, and Ensign Pavel Chekov certainly wasn’t its best-written character. Yet, each was a perfect fit for the other. The Enterprise’s exuberant young navigator was essentially a sawed-off version of Captain Kirk—a daring, fresh-faced swashbuckler and junior varsity Playboy of the Galaxy. True, Koenig’s accent was laughable. No matter. He sold audiences on Chekov anyway, with an energetic, tongue-in-cheek approach that meshed perfectly with the character. Yes, all those jokes about Leningrad were terrible. But Koenig knew they were terrible and often delivered them with a sly grin that suggested Chekov didn’t actually believe Scotch was invented by a little old lady from Moscow; he simply enjoyed confounding his crewmates with wild assertions of ethnic pride. Koenig appeared in a total of thirty-six adventures, and his vivid, zesty performances enlivened every installment.

Thanks in part to Takei’s Green Berets misfortune, Koenig made a favorable impression quickly, with small but effective moments in a handful episodes shot during his first few months on the show, including “Friday’s Child,” “Who Mourns for Adonais,” and “The Apple.” Producers added the actor to the cast to try to attract some of the young, female viewers that had made The Monkees a surprise hit the previous season. (Koenig bore a resemblance to diminutive Monkees vocalist Davy Jones.) Beginning with “The Apple,” Chekov was often seen romancing young women among the Enterprise crew, or wherever opportunity presented itself.

By the time “Spectre of the Gun” was made during Season Three, the actor had perfected a personal brand of frothy, seriocomic romance. In this episode, Chekov is part of a landing party forced to recreate the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral—standing in for the villainous (and doomed) Clanton Gang. Mistaking him for Clanton Gang member Billy Clayburn, a young woman named Sylvia (Bonnie Beecher) rushes up and plants an enthusiastic kiss on the startled Chekov. This early scene is played for laughs, and Koenig affects an amusing “I can’t help it if I’m irresistible” attitude as he comes up for air between lingering, passionate kisses. “What can I do, Captain?” he grins, wearing a droopy-eyed look of blissful submission. “You know we’re always supposed to maintain good relations with the natives.” Later, Chekov and Sylvia share a tender moment on the front porch of the general store. When she asks him if he’s forgotten about next week’s dance, he reassures her he has not. “I’m looking forward to it … very much.” Koenig delivers the line with an audible, and even visible, shift in tone during the brief pause before “very much.” His tone of voice softens, his eyes linger on Sylvia. It’s a brilliantly played moment of revelation, as Chekov suddenly realizes he has real feelings for Sylvia. In the middle of this line, the tone of the scene changes. Suddenly, Chekov must try to rebuff Sylvia’s proposal of marriage (“I’m not someone you can marry,” Koenig says, his voice thick with regret) and gets lured into a (seemingly) fatal gunfight. “Spectre of the Gun” remains a fine episode, but it loses a bit of steam with Chekov’s “death” midway through.

“Mirror, Mirror” and “Day of the Dove” gave Koenig rare opportunities to demonstrate wider range. In “Mirror, Mirror,” Chekov’s venal alter ego attempts to assassinate Captain Kirk (and is foiled when one of his henchmen abruptly switches allegiances). Koenig is excellent here, although given their troubled off-screen relationship, seeming gleeful while attempting to kill William Shatner may not have required much acting. In “Day of the Dove,” a hate-eating life force dupes Chekov into thinking that the Klingons killed his brother. He becomes bent on revenge—even though, as Sulu later informs us, Chekov is an only child! “Cossacks! Filthy Klingon murderers! You killed my brother Petr!” Koenig rages, rushing the Klingons bare-handed, radiating hatred from every pore. Apart from these two adventures, however, nearly all Koenig’s notable performances adhered to the contours of his work in “Spectre of the Gun,” balancing comedy and romance, sometimes with a dramatic turn toward the end. The actor would have to find vehicles beyond Star Trek—such as his performance as the villainous Bester on Babylon 5—to further showcase his versatility.

Majel Barrett

After prominent supporting roles in her first two appearances (“The Naked Time” and “What Are Little Girls Made Of?”), Majel Barrett soon faded into the background. Even though she had more influence with creator-producer Gene Roddenberry than any other cast member, Barrett’s Nurse Chapel seemed like a secondary character even among the show’s secondary characters. Screenwriters treated the nurse like a walking prop. She rarely ventured out of sick bay, where she served as a compliant sounding board for Dr. McCoy but seldom took any initiative.

“Amok Time” was a rare exception. In this installment, Chapel’s romantic yearnings for Mr. Spock (established in “The Naked Time”) find their most touching and believable expression. A hopeful Chapel brings Spock a bowl of Vulcan plomeek soup, which the Pon Farr–rattled first officer hurls into the hallway. Cowering in the corridor, Barrett looks puzzled and terrified. Later, when Spock apologizes to her, a silent tear streaks her right cheek. She turns her back to him to hide her tears. When Spock calls her “Nurse Chapel,” she reminds him, “My name is Christine.” Barrett’s voice cracks. The line reverberates with barely hidden longing.

Chapel had more lines and showier scenes in both “The Naked Time,” in which, stricken by the inhibition-freeing disease, Chapel first confesses her love for Spock; and ‘Little Girls,” in which she reunites with a lost love who turns out to be a mad scientist. But her subtle, touching work in “Amok Time” remains her finest performance—or at least her finest live-action performance, as Nurse Chapel. Barrett was also central to the highly amusing animated adventure “Mudd’s Passion,” in which Chapel gives a love potion to Mr. Spock, with disastrous consequences. In this animated yarn, Barrett displayed a gift for comedy that served her well in her later appearances as Lwaxana Troi.

While Barrett made a negligible contribution to the classic Trek series as the underwritten Chapel (she was arguably more important to the show as the voice of the Enterprise computer), she wowed audiences in her nine later appearances (six on Next Gen, three on Deep Space Nine) as the colorful, outspoken Lwaxana. If Christine Chapel had had a bit more Lwaxana in her, Star Trek would have been a livelier show.

Grace Lee Whitney

Prior to her unceremonious ouster midway through Star Trek’s first season, Grace Lee Whitney contributed winning performances to a pair of memorable episodes. Her tenderhearted scenes with the lovesick Charlie Evans (Robert Walker Jr.) provide the classic installment “Charlie X” with much of its emotional resonance. She was also very effective in “Miri,” as the lovely, young Yeoman Rand struggles with the emotional ramifications of contracting a disease that will not merely kill her but, in the process, disfigure her. Both of these performances suggest that Whitney could have made a more meaningful contribution to the show had her tenure continued.