32

Close Encounters with the (Practically) Divine

Mankind has no need for gods.

—James T. Kirk, “Who Mourns for Adonais”

Gene Roddenberry rejected his parents’ Southern Baptist faith, and although he married Majel Barrett in a Shinto-Buddhist ceremony in Japan in 1969, he claimed no affiliation with that belief system either. For most of his life, Roddenberry remained evasive about his spiritual beliefs (if any). However, during his extensive, wide-ranging interviews with author Yvonne Fern, a former nun, for her book Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation, Roddenberry voiced both his ambivalence about the concept of a Creator and his unwavering faith in a bright future for humankind. Both of these threads were woven into the fabric of Star Trek from the outset.

The show’s dismissive attitude toward religion was, in part, a reflection of its times, an era of dwindling church attendance and increasing secularization. The U.S. Supreme Court, in landmark decisions in 1962 and ’63, decreed that state-sponsored prayer in public schools was unconstitutional. While Star Trek’s second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” was being filmed in the summer of 1965, the Roman Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council was concluding a series of sweeping changes designed to modernize worship and redefine the church’s relationship to a rapidly changing world. In April 1966, while Roddenberry and his team were gearing up to begin production of Star Trek’s first season, Time magazine published its famous “Is God Dead?” cover story, about the challenges contemporary theologians face in trying to make God seem relevant to an increasingly uninterested public.

Primarily, however, Star Trek’s religious skepticism originated with its creator-producer. “We must question the story logic of having an all-knowing, all-powerful God, who creates faulty humans and then blames them for his own mistakes,” Roddenberry said during one of his campus lectures in the early 1970s.

More than a dozen times during the original seventy-nine episodes and twenty-two animated adventures, the crew of the Enterprise encountered “gods” or beings with godlike powers, always with grievous consequences. Many of these teleplays were rewritten by Roddenberry or based on his original stories, and all were crafted under his watchful eye. During the creation of the animated episode “Bem,” screenwriter David Gerrold met repeatedly with Roddenberry, who suggested several revisions to the scenario. “Gene said, ‘How about they meet God on this planet?’” Gerrold shared in a DVD audio commentary. “And my gut-level [reaction] was, ‘Haven’t we done that one enough?’” Apparently not, because in 1975, when Paramount Pictures asked the Great Bird of the Galaxy to write a Star Trek feature film, Roddenberry returned to this familiar concept yet again, delivering a treatment titled The God Thing that Paramount rejected as too antireligious. In this screenplay, “God” turns out to be a faulty computer from another dimension; Jesus Christ is an android from outer space.

The abandoned God Thing story was only the latest in a series of Star Trek yarns that pitted Kirk and Spock against seemingly godlike beings.

The Gods Themselves

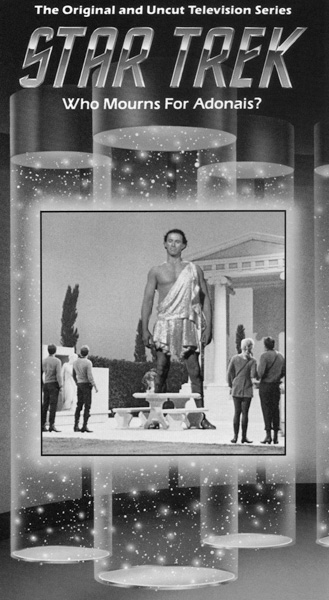

Apollo (Michael Forest, looming over the landing party) needs human worship to survive.

Although credited to screenwriter Gilbert Ralston, “Who Mourns for Adonais?” could serve as the ur-text for Roddenberry’s secular humanist attitude toward divine beings. On planet Pollux IV, an away team is held captive by a being who claims to be the Greek god Apollo. Meanwhile, the orbiting Enterprise is held (literally) in the deity’s grip—by an energy field that looks like a giant green hand. Apollo wants the humans to worship him as they once did on Earth (“You will gather laurel leaves, light the ancient fires, kill a deer, make your sacrifices to me. Apollo has spoken!”), but Captain Kirk balks at the idea. “Mankind has no need for gods,” he says. Although this statement is tempered when Kirk continues with “We find the one quite adequate,” this addendum plays like a half-hearted, last-second throw-in to appease the NBC Standards and Practices department. Earlier McCoy stated flatly, “Scotty doesn’t believe in gods.” And when the haughty deity announced, “I am Apollo,” Chekov sarcastically replied, “And I am the tsar of all the Russias.”

The story’s argument for atheism is so thinly veiled it’s practically a single-entendre: The gods need human worship to survive; without it, they fade away. (In other words, gods exist only so long as humans believe they exist.) The other Greek gods have already passed into nonexistence. Although the scenario involves a pagan deity, the teleplay invites comparisons with the Old Testament god worshipped by the Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) by making Apollo the only survivor of Olympus—that is, the One God. Ultimately, Apollo is revealed to be—well, Apollo, the entity once worshipped by the ancient Greeks. However, he’s an advanced alien life form with the power to manipulate energy, not a supernatural being. He is vanquished when the landing party discovers and destroys his power source. Apollo’s last words, as he fades from existence, sum up Roddenberry’s beliefs succinctly: “The time has passed. There is no room for gods!”

The Emmy-winning animated adventure “How Sharper Than a Serpent’s Tooth” is a virtual rewrite of “Who Mourns for Adonais?” with the Native American Kukulkan standing in for the Greek Apollo. Once again the Enterprise encounters an ancient deity that requires worship for survival. In other, similar live-action episodes, beings with godlike powers are revealed to be weaklings (“Catspaw”) or misbehaving children (“The Squire of Gothos”). The “friendly angel” (actually, a malevolent extraterrestrial) of “And the Children Shall Lead” dupes a group of youngsters into killing their parents and then trying to take over the Enterprise. Invariably, Star Trek’s “gods” are fakes of one type or another. Only the dangers they pose are real.

Aside from those episodes, many other installments contain offhandedly dismissive remarks toward religious faith. For instance, at the conclusion of “Obsession,” after Scotty and Spock have beamed up Captain Kirk and a security officer, despite interference from an antimatter explosion, Scotty exclaims, “Thank heaven!” To which Spock replies, “Mr. Scott, there was no deity involved. It was my cross-circuiting to B that recovered them.” Then McCoy chimes in, “Well then, thank pitchforks and pointed ears!”

Star Trek’s attitude toward gods and religious figures of all sorts is almost uniformly negative, but there are exceptions for every rule. Occasional nods to the existence of a creator sneak in, as in “Metamorphosis,” when the Companion states that the creation of life is reserved for “the Maker of all things.” The most surprising exception to Star Trek’s prevailing atheism is “Bread and Circuses.” In this episode, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy discover a parallel Earth where Rome never fell and gladiatorial contests are broadcast on television. Throughout the adventure, the away team receives aid from a group of peace-loving “sun worshipers.” During the wrap-up, Spock remarks on the illogic of this, since sun worship is usually a primitive, superstitious faith. Then Uhura chimes in, explaining that the natives don’t worship “the sun up in the sky” but rather “the son of God.” Kirk smiles. “Caesar … and Christ,” he says. “They had them both. And the Word is spreading only now.” Spock predicts that this newfound faith will bring peace, love, and brotherhood to the planet in less than a hundred years. (The Vulcan apparently assumes the natives of this unnamed world somehow will avoid repeating Earth’s bloody crusades, reformation, counter-reformation, witch trials, and so on.) The unabashedly pro-Christian stance of “Bread and Circuses” sets it apart from every other classic Trek adventure. Astonishingly, this episode was coauthored by Roddenberry and Gene Coon. It should be emphasized, however, that the proreligious sentiment is reserved for the episode’s epilogue. “Bread and Circuses” remains primarily a satire of TV.

Prophets of Repression

Perhaps the pro-Christian stance of “Bread and Circuses” can be chalked up as an expression of Roddenberry’s own conflicted beliefs. Despite his apparent atheism, Roddenberry sometimes (albeit rarely) spoke of a nebulous higher power he referred to as “the All.” This was pointedly not the Judeo-Christian God. He never explained this idea fully, and may have never completely worked out the concept himself. But it appears that Roddenberry at least considered the possible existence of a guiding force (along the line of Carl Jung’s collective unconscious but perhaps best thought of as “the human spirit”) that pulls humankind perpetually forward, ever nearer to perfection. He discusses this idea, warily, with Fern in The Last Conversation.

But while Roddenberry’s attitude toward the metaphysical realm may have wavered, his opinion of religion was unchanging: He had no use for it. Roddenberry vehemently rejected an NBC executive’s suggestion that the Enterprise crew include a chaplain. (This idea was tendered as a way of alleviating concerns over the ship’s satanic-looking first officer.) Whenever religious leaders appear on Star Trek, they prove troublesome. At their best (as in “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky”), they are well-meaning but ignorant and misguided; at their worst, they are agents of inhuman, individuality-crushing repression. The latter was the case in “The Return of the Archons,” written by Boris Sobelman from Roddenberry’s original story. In this tale, the Great Bird asserted his feelings about religion in no uncertain terms.

An Enterprise landing party beams down to Beta III to investigate the disappearance of the Starship Archon, which crashed on the planet 100 years earlier. They discover a world full of placid, dazed-looking people. Suddenly, “Red Hour” strikes, and the mild-mannered Betans go on a rampage of senseless destruction and violence. Afterward, the populace returns to a state that Kirk describes as “mindless, vacant contentment.” The Betans, we learn, are under the mental control of Landru, a tyrannical, telepathic supercomputer that is worshiped as a god. (The followers of Landru refer to themselves as “the Body.” Not coincidentally, Christian churches sometimes refer to themselves as “the body of Christ.”) Landru protects and cares for the population but keeps the Betans docile and servile. They perform the functions necessary to keep themselves and Landru alive but have no free will, no liberty of thought or expression. They serve “the will of Landru,” which is enforced by the Lawgivers. These cloaked, monkish figures carry crosier-like rods that deliver high-voltage electric jolts to anyone who defies Landru’s will. Nearly all the Betans are brainwashed followers of Landru. Even McCoy is “absorbed” into the cult. The Earthmen come to the aid of a handful of valiant unbelievers, dissidents who oppose this evil theocracy.

It’s significant, of course, that Landru is revealed to be a computer. This dovetails perfectly with the mildly technophobic undercurrent of Star Trek’s humanism. (For more on this, see the preceding chapter.) To reach their potential, this episode argues, humans must rely on themselves, not on machines, and certainly not on appeals to some artificial deity. Religion only crushes the human spirit—or at least represses original thought and independent initiative.

Other installments also present religion as a force for repression or source of conflict. In “The Apple,” Vaal (another computer-god) provides for the people of planet Gamma Trianguli VI—keeping them at peace, eternally healthy, and eternally young—but forbids romantic love. In “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” the Oracle (yet another godlike computer) hides the truth from the passengers of a giant starship, perpetuating the lie that the people are still on their home world. And in the animated adventure “The Jihad,” a madman tries to trigger an intergalactic war by manipulating an alien race’s religious fervor. These episodes underscored Roddenberry’s often-stated conviction that religion was a divisive force that would have to be set aside (or outgrown) for humankind to achieve its full potential.

Throughout Roddenberry’s lifetime, Star Trek’s attitude toward religion remained belligerent. The franchise finally struck a less strident note with Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, in which the Bajoran religion was treated seriously and, for the most part, sympathetically—even though the true nature of the Bajoran “prophets” (also known as the “wormhole aliens”) remained ambiguous. While imperfect, the Bajoran religion brought healing and solidarity to a beleaguered civilization. However, DS9 was created by Rick Berman and Michael Piller, not Roddenberry, and premiered two years after the Great Bird’s death.

Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely

Not only are gods and religions untrustworthy, but godhood is not to be sought. That’s the moral of several more Star Trek episodes, including the series’ second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

In this seminal adventure, navigator Gary Mitchell (Gary Lockwood) and psychologist Elizabeth Dehner (Sally Kellerman) acquire fantastic telekinetic powers after the Enterprise attempts to cross an energy barrier that surrounds the galaxy. Lockwood, in particular, grows ever more dangerous as his powers quickly increase. He begins to consider himself a god and his former crewmates lesser beings. Once he achieves “godhood,” Mitchell loses all compassion for humanity, as well as any ethical inhibitions. “Morals are for men, not gods,” Mitchell declares. There’s a great deal of talk about gods in this teleplay, none of it flattering to the “deity,” which might be more accurately described as inhuman rather than superhuman. When an attempt to maroon Mitchell on a remote mining colony goes awry, Kirk is forced to kill his former friend, who’s now well on his way to becoming a ruthless superpowered despot who wants to enslave the inferior humans. To survive, to retain its freedom, humanity must destroy the “god.”

“Where No Man Has Gone Before” went where many Star Trek episodes would subsequently travel. Repeatedly in later teleplays, godlike power corrupts those who come to possess it. In “Plato’s Stepchildren,” denizens of a remote planet have gained psychokinetic superpowers by ingesting high doses of the rare element kironide. Now they lord it over a dwarf lackey and torment luckless visitors to the planet, including an Enterprise landing party. Dr. McCoy injects Kirk and Spock with high doses of kironide, empowering our heroes to unseat the cruel leader of the aliens, Parmen (Liam Sullivan). “Uncontrolled power will make even saints into savages,” Parmen says, succinctly making the thematic point. Teenager Charlie Evans, a space crash survivor raised by godlike alien beings, gains psychic powers in “Charlie X” but uses them improperly—doing cheap card tricks to impress girls and “thinking” out of existence anyone who hurts his tender feelings. In both “Return to Tomorrow” and “By Any Other Name,” superadvanced, nearly divine beings evolved beyond corporeal form to take possession of human bodies and begin committing very human sins, including murder. And in “Requiem for Methuselah,” Flint (James Daly) gains immortality but finds no comfort in it, forced to endure the aging and death of all his loved ones throughout hundreds of lifetimes.

Ironically, perhaps, given the show’s general hostility toward religious faith, many observers have commented on the religious-like fervor of Star Trek fans. “Those 79 episodes are their revealed texts, the sacred tablets by which their lives here and now and beyond are charted,” wrote a reporter from the Calgary Herald, describing a 1975 Trek convention. In 1994, University of Wisconsin professor Michael Jendra published a paper in the journal Sociology of Religion titled “Star Trek Fandom as a Religious Phenomenon.” In his essay, Jendra notes that fandom “involves a sacralization of elements of our culture, along with the formation of communities with regularized practices that include a ‘canon’ and a hierarchy. Star Trek fandom is also associated with a popular stigma, giving fans a sense of persecution and identity common to active religious groups.” He later clarifies that fans’ Star Trek “faith” doesn’t supplant other religious beliefs (when present) but is held in combination with them.

Struggling to explain the ongoing appeal of the franchise in his memoir The View from the Bridge, director Nicholas Meyer—who helmed two of the most successful Star Trek feature films (The Wrath of Khan and The Undiscovered Country) and cowrote a third (The Voyage Home)—described Star Trek as “religion without theology.” Meyer equated fans repeatedly rewatching the same episodes with Catholics attending Mass.

At the least, Star Trek remains the textbook definition of a “cult” television series.

However, Roddenberry always eschewed religious comparisons. “I’m not a guru and don’t want to be,” he told an Associated Press interviewer in 1976. “It frightens me when I learn of 10,000 people treating a Star Trek script as if it were Scripture. I certainly didn’t write Scripture, and my feeling is that those who did weren’t treated very well in the end.”