Freud once said that when two people make love, there are six people in bed—the couple and their parents. After an affair, add a seventh: the ghost of the lover. This chapter helps you to pull your parents and the lover out from under the covers, warm up the space between you, and get sexually intimate again. By sexual intimacy I mean that in the presence of your partner you can:

• feel emotionally safe and protected, though physically naked;

• be yourself yet feel connected;

• value passion and playfulness in bed, but trust that closeness matters more to both of you than performance;

• acknowledge your own sexual fears and frustrations, and still feel accepted and respected;

• ask openly for what pleases you sexually yet set limits on what feels uncomfortable;

• have compassion for each other, knowing that what makes you frail and imperfect also makes you human.

Right now, such closeness may seem light-years away.

You, the hurt partner, are likely to hunger for the reassurance of physical closeness, while pushing your partner away to protect your vulnerable self. Nowhere are you going to feel more insecure, more undesirable, than in the bedroom, where you compare yourself to your partner’s lover, magnifying this person’s physical appeal and minimizing your own.

You, the unfaithful partner, are likely to miss the illicitness, the drama, the newness of the affair. After so much high chemistry, you may have trouble getting sexually aroused with a partner who seems tentative, self-conscious, or rejecting. You may be put off by the pressure that your partner puts on you, or that you put on yourself, to prove your love in bed.

As you both struggle to reestablish intimate ties, two cognitive errors may block your way. One is your tendency to attribute meaning to your partner’s sexual behavior without examining the evidence (for example, a wife assumes that if her husband can’t get an erection, he must be cheating on her). The other is your tendency to set such rigid or unrealistically high sexual standards for yourself and your partner that your physical relationship seems inadequate (for example, a husband assumes that his wife should always know what pleases him).

Hurt partners typically assume:

1. “If you’re not interested in making love, or can’t stay aroused, it’s because you don’t find me sexy or desirable.”

2. “If you’re not interested in making love, or can’t stay aroused, it’s because you’re still cheating on me.”

3. “I’ll never be able to satisfy you the way your lover did. I can’t compete.”

Unfaithful partners typically assume:

1. “If I don’t satisfy you in bed, you’ll think I’ve lost interest in you or am still cheating on you.”

2. “I had great sex with my lover. Since my sex life with you can’t compare, you must be the problem.”

Both of you are likely to assume:

1. “Sex should come naturally and easily. We shouldn’t touch or be physical until we feel more comfortable together.”

2. “If I let you touch me, you’ll want to go further.”

3. “If you masturbate, it means you don’t love me and our relationship’s in trouble.”

4. “Sex should always be passionate.”

5. “You should always know what pleases me sexually.”

6. “If I ask for changes in the way we make love, I’ll hurt your feelings. If I do what you ask, I’ll violate mine. Change isn’t worth it.”

7. “We should reach orgasm simultaneously.”

8. “We should have multiple orgasms.”

9. “We should reach orgasm through intercourse.”

10. “We should reach orgasm every time we make love.”

11. “We should want sex with the same frequency, and at the same time.”

12. “If our relationship were strong enough, and we were normal people, we wouldn’t have to use fantasy or sex tools.”

13. “The subject of getting tested for AIDS, or other sexually transmitted diseases, is too inflammatory to bring up.”

14. “I’ll never overcome the shame I feel about my body and my lovemaking.”

Let’s look at each of these questionable assumptions, and go through some exercises to help you think and act in more intimate ways.

If your partner seems less than excited by you sexually, you’re likely to assume that you’re the cause and ignore your partner’s contribution to the problem. Traumatized by the affair, you may see your partner’s slightest hesitation as proof of your own sexual inadequacy.

After Mark’s affair, his wife, Wendy, blamed herself for their problems in bed. Her response is typical.

“I question myself all the time,” she told me. “Maybe I’m no good for Mark. I take too long to come. I don’t lubricate as well as before. I’m too afraid to let go. I never believed I was sexy or attractive enough for him, and now I resent him for making me feel I was right.”

Buried in self-doubt, Wendy never entertained the idea that Mark might have his own sexual anxieties, which were as central to their problems as anything inherently deficient in her. Some of these anxieties, in fact, predated their relationship. It was only when Wendy took herself out of the picture and looked outward that she realized:

• Mark had worried that his penis was shamefully small years before she met him. He had long seen himself as a sexually ineffectual, unattractive man who came too fast and couldn’t please her.

• The affair put Mark under enormous pressure to perform to prove his love to her—he knew how damaged and undesirable his infidelity made her feel—and the tension may have killed his desire.

• Mark probably expected her to reject him after what he had done, and, conflict avoider that he was, he may not have wanted to initiate sex and risk being turned down.

You, like Wendy, need to be aware of misinterpreting your partner’s sexual response. The problem could be not that your partner is having negative thoughts about you but that you think your partner is. What your partner may want most is a compassionate response to embarrassing problems, and help in overcoming them.

If you’re sleeping on opposite sides of the bed, don’t automatically assume your partner doesn’t love you or want to be with you. Sex is only one way to relate, and right now it may be one of the most stressful. Wendy realized that though her husband was dodging her sexually, he was making an effort to come home early from work on a regular basis and planning fun things to do on weekends. You, too, should take notice when your partner wants to spend time with you and seems to enjoy your company in nonsexual ways. What’s important is that you nourish and notice positive interactions. Not all of them have to be sexual.

1. Try to generate a list of explanations for your partner’s desire and arousal problems that don’t implicate you. Wendy named three:

• deep-seated feelings of sexual inadequacy;

• pressure to perform;

• fear of rejection or confrontation.

Other explanations might include:

• need to regain power or reassert control;

• wish to hurt or punish you;

• menstruation;

• medical disorders;

• fatigue or other forms of stress;

• effects of medication, alcohol, or drugs;

• compulsion to get things done before allowing time for relaxation or intimacy;

• fear of opening up and feeling vulnerable or ridiculed;

• fear of pregnancy;

• self-consciousness caused by lack of privacy (children or live-in relatives);

• puritanical attitudes toward sex (feeling whorish, dirty, or sinful);

• homosexual proclivities;

• sexual trauma from the past.

2. Let your partner know that you’re struggling to take his or her disinterest in sex less personally. In a gentle, nonjudgmental way, ask for help in finding alternative explanations that are equally plausible.

3. It’s your job as the hurt partner to reassure your mate that you’re not looking for fantastic sex but for the beginning of a reconnection. Find your own way of asking, “What can I do to convince you that I just want us to move closer together?” Let your partner know that performance is unimportant, that erections or orgasms are unimportant, that what matters is that the two of you create a climate of acceptance, openness, and warmth.

4. Try to value time spent together that is intimate but not necessarily sexual—sharing the Sunday paper, cooking a favorite meal, going for a bike ride or a walk.

Virtually all of you are likely to jump to this conclusion, though you may have no proof, only vague suspicions and a heightened sense of vulnerability and distrust. No matter how much evidence you amass to the contrary, these unsubstantiated fears will probably gnaw at you for months or even years, and make it all but impossible for you to risk intimacy.

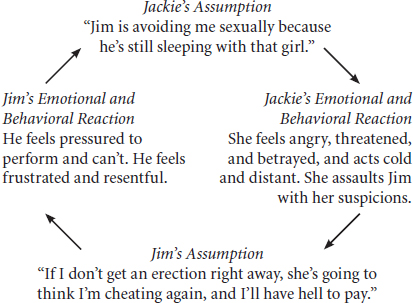

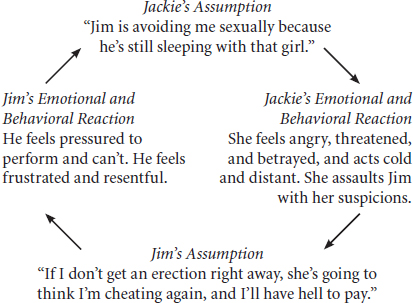

A forty-six-year-old accountant named Jackie found herself picking apart her husband’s every move, searching for confirmation of her fear that he was still straying. Her accusations increased the pressure he felt to prove his love in bed. This, of course, destroyed his desire and, in turn, reinforced her suspicions that he was sleeping with someone else. Here’s how you might diagram their interaction:

You shouldn’t automatically assume, as Jackie did, that because you’re suspicious, there are grounds for it. If you’re wrong, you’re likely to poison your relationship as much as if your partner were still cheating on you.

1. Try to distinguish fact from fear. Ask yourself, “How much do I know, as opposed to how much do I suspect for no reason except that I’ve been betrayed before?” If you have solid proof that your partner is unfaithful, it’s time for some serious thinking about whether it’s in your best interest to stick around. If all you have are lingering suspicions, however, counter them with evidence that your partner is reaching out and trying to reconnect—initiating conversations that matter to you, inviting you on business trips, perhaps just calling during the day to see how you’re feeling. These gestures won’t by themselves improve your sex life or make you feel more sexually desired, but they should help you talk back to your doubts and obsessions, and begin to trust your partner’s professions of fidelity.

There could be many reasons for your partner’s desire or arousal problems that have nothing to do with cheating. Some are listed on Assumption #1, chapter 8. It may help to review these alternative explanations and balance them against your unconfirmed fears.

2. You may not be able to erase your suspicions, but you can try to stop them from dominating or poisoning your life. Two techniques may help.

One simple but effective ploy is called thought stopping. As soon as you begin to think of your partner with someone else, try to break your concentration by saying, out loud or to yourself (the exact words are up to you), “Stop. Here I go again, dragging myself down. Let it go.” Then, focusing your attention outward, notice or describe something upbeat or intriguing around you or recall the last time you had a warm or funny interaction with someone you care about. You can also turn inward and, breathing deeply, send messages to your muscles to loosen and relax. You may not be able to force your mind to stop thinking particular thoughts, but you can gently distract it.

The other technique—call it challenging your assumptions—involves the use of a Dysfunctional Thought Form. What you do is record the event as objectively as possible, as well as your immediate feelings and thoughts. You then systematically challenge, or talk back to, your thoughts, looking for cognitive errors.

Here’s an example of how one wife talked herself through her suspicions and avoided an ugly scene with her husband, Jim, that would have left them further apart than before. The husband had admitted to several one-night stands on previous trips, but had been working to prove his fidelity ever since.

Objective event: When Jim got home from Zurich, he went right to sleep. He had zero interest in sex.

Emotional reaction: Scared, rejected, suspicious.

Automatic thoughts: “I bet he slept with someone while he was away. We haven’t had sex for over a week—he never goes that long. He’s been extra nice to me since he left—added proof that he feels guilty.”

Rational response: “You’re taking his behavior personally and jumping to conclusions. Maybe there are other reasons that he doesn’t want you tonight. Like what? Like he’s tired—he just got off an eight-hour flight. Like he has a big work day tomorrow and it’s late. Like he’s afraid he won’t perform well and you’ll get upset.

“Stick to the facts. He invited you to join him, and when you couldn’t, he shared a room with one of his male associates. He called every day. He seemed really happy to see you when you picked him up at the airport, and he brought you your favorite perfume. Sure, it may not all be heartfelt—part of him may just be trying to reassure you. But what’s wrong with that? Restoring trust takes time. He clearly cares about you and wants to make everything okay again. Just because you’re suspicious doesn’t mean he’s done something wrong. Let it go. The truth is, you’re tired tonight, too. If you weren’t feeling so insecure, you wouldn’t be that interested in sex, either.”

It’s common to compare yourself to the affair-person in the most unflattering and self-deprecating ways. Whatever you hate about your body or your performance in bed, you’re likely to admire in that person, especially if you’ve never met. You think your breasts are too small? The lover must have huge ones. Your penis seems too soft? The lover’s must be made of steel. Your lovemaking seems ordinary? Your partner and the lover must have enjoyed the wildest, darkest, most uninhibited sex, and together reached a thousand multiple orgasms.

Fantasies like these are likely to make you feel so undesirable and inferior, so convinced that you lack the goods, that you can no longer function as an active sex partner. If your sex life is ever going to get back on track, you need to see these fantasies for what they probably are: expressions of your sexual insecurities after the trauma of the affair.

The reality is that men frequently have affairs even when they’re sexually satisfied at home, and women often stray not for better sex but to feel more loved, appreciated, and respected.1 In my own clinical practice, unfaithful partners, both men and women, report that sex with the affair-person is often both awkward and infrequent, and that they only wished it measured up to their partner’s wild imaginings. In an authoritative national study of sex habits in America, “the people who reported being the most physically pleased and emotionally satisfied were the married couples.... The lowest rates of satisfaction were among men and women who were neither married nor living with someone—the very group thought to be having the hottest sex.”2

This isn’t to say that sex with the affair-person wasn’t at times more torrid than it is with you; torridness is hard to come by when you have one eye on the clock and the other on the kids. Laced with a spirit of defiance and secrecy, illicit sex is bound to seem more transcendent. But try not to be demoralized. Romantic love is a distorting and transient experience, and the heat your partner may have generated with another person would have cooled in time, as it has perhaps with you. Passion often loses its edge when it’s no longer new or forbidden.

Keep in mind that if your partner has decided to recommit to you, it’s likely to be because you offer something deeper, more enduring, than romantic love. You need to believe in and reclaim those aspects of yourself that your partner values in you and that you value in yourself. You need to trust that you’re worth loving, and work to regain that sense of self that informs you that you’re a wonderful person who has made your partner happy, and can continue to do so in countless ways.

Don’t let your obsession with the affair-person distract you from what should be the real issue right now: restoring intimacy with your partner, in and out of bed. Instead of making useless comparisons, try to find new ways of injecting creativity, energy, and romance back into your own lovemaking; instead of competing with the affair-person, step out of the ring, bring the focus back on your relationship, and address the issues that let the affair-person get between you.

When I speak of you, I mean both of you; it’s not your job alone to satisfy your partner or create a fulfilling sex life. Developing sexual intimacy is a two-person project.

1. If you consider yourself sexually inept or just uninformed, why not educate yourself? Self-help guides such as Getting the Sex You Want3 or For Each Other4 can teach you about your body and your sexual responses, and make you feel more competent in bed. You can watch X-rated videos (some are instructive; others exploit women as sex objects), or consult a friend or sex therapist. You can also learn from each other what gives you pleasure (see the exercise on Assumption #6, chapter 8).

2. Sometimes, when you’re feeling insecure, it helps to work things out inside your own head. But at other times you need to share your vulnerabilities and ask your partner for help and reassurance. Try to keep the focus on yourself—on your insecurities, fears, obsessions—not on the affair-person or on the details of the affair. Instead of asking, “Did you see that woman again?” you might say, “I keep thinking about you and that woman. I’m feeling terribly threatened today and I don’t think it’s because of anything you’ve done, but you seem to be lost in your own thoughts. Can you reassure me?”

It’s fair to expect your partner to reach out and try to comfort you. If your partner can’t, you may want to question whether this is the person you want to spend your life with.

You may be right: Your partner may believe that if your response falls short, you must want to be somewhere else. But the pressure to be interested and aroused may also come from you—from your guilt, your qualms about reconnecting, your inflated ideas about what your partner expects from you. What may matter most to your partner is not your performance but your commitment.

Whatever you’re feeling, try to talk it out—it may reduce the pressure you feel to perform, as well as the likelihood that your partner will misread your response.

One unfaithful partner, a thirty-nine-year-old oral surgeon named Phil, told his wife, “I feel I have to be some incredible stud to prove I want to be here, and the pressure’s killing me. I wish we could just get into bed and hold each other, and then whatever happens, happens.”

It may help you, as it did Phil, to explain that you’re having sexual problems not because you find your partner unattractive or are preoccupied with someone else, but because you’re worrying about letting your partner down. Don’t be surprised or put off, though, if you continue to be accused of cheating or rejecting your partner. From the time the affair is revealed and you completely disconnect from the affair-person, it often takes at least eighteen months to restore the trust you violated.

Only you can provide the reassurances your partner needs to move the healing process forward. Among the things you can do:

1. Let your partner know when you’re feeling loving and glad to be together. Speak up when you feel more hopeful or positive about the two of you; don’t assume your partner knows when you’re happy. “I was thinking at work today how beautiful you looked last night”; “I really felt close to you when we stayed in bed talking this morning”—the exact words don’t matter; the reassurances do.

2. Describe what you like about your partner’s body and lovemaking. Most people like to be complimented on their looks and to know what their partners find attractive about them. Whatever you choose to comment on—“I love how that dress looks on you,” “Your face makes me smile,” “The way you’re touching me feels great”—don’t lie, don’t fabricate, but don’t hold back positive feedback, either. Be generous.

3. Reveal any sex problems you had with the affair-person. It may help your partner dispel the notion that everything was so terrific for you and that person if you reveal whatever sexual difficulties you may have had. The affair-person never reached orgasm, you had sex only twice in a nine-month affair, the explosiveness you experienced in bed was overshadowed by the explosiveness of the relationship—these sorts of corrective realities bring the affair down to earth and make it easier for your partner to stop obsessing and move on.

4. Reveal any sex problems you have that predate, or are unrelated to, your relationship with your partner. If your partner wrongly assumes responsibility for any of your sexual difficulties, it’s important to set the record straight. Freed from blame, your partner is apt to reduce the pressure on you to perform, and even become your ally in overcoming whatever it is that sexually disables or inhibits you.

A fifty-two-year-old attorney named Arnold had problems getting an erection ever since he started taking medication to control his high blood pressure. After his affair, he avoided his wife, and she assumed he no longer found her attractive. “I’ve had this problem on and off ever since I started taking diuretics,” he reminded her. “The problem’s not my attraction to you; it’s medical. And the pressure I put on myself, wanting to please you, just makes it worse.”

5. Coach yourself to stay sexually involved and not get discouraged. When you’re having arousal or desire problems, you’re likely to want to avoid all physical contact, and may need to coach yourself to stay involved. Filling out a Dysfunctional Thought Form may help you monitor your resistance, confront your avoidance tactics, and keep yourself sexually connected.

Here’s one that Arnold filled out to overcome his pattern of anxiety, shame, and withdrawal.

Objective event: It’s Saturday morning. I’m lying in bed with June [my wife], thinking about initiating sex.

Emotional reaction: Anxious, angry, paralyzed, discouraged.

Automatic thoughts: “It’s ridiculous, being afraid to approach June after fifteen years of marriage. But she’s so sensitive and takes everything so personally that I’m scared I won’t get hard, and then she’ll assume I’m getting sex elsewhere or that I’ve lost interest in her. She even keeps a record of when we last had sex. Celibacy would be easier.”

Rational response: “Of course you’re feeling uncomfortable. This is going to take time. The problem, which you caused, won’t go away overnight. She needs to know you’re committed. If you avoid her, she’ll feel more rejected, more unloved, and you’ll just poison the relationship more. You may not get hard, but so what? Your erections mean too much to you—maybe to her, too. Let her know you want to be more loving and connected, but she’s got to stop rating your performance (this goes for you, too). Can she accept this? Go ahead, take the first step. Reach out to her.”

If you’re avoiding sex, as Arnold did, you too may want to use a Dysfunctional Thought Form to help you overcome your fears and frustrations. Above all, however, you need to be patient, persist, and convey again and again the message that you’re committed and want to work out your sexual issues together.

When sex seems less satisfying with your partner than with your lover, it’s common to assume your partner is to blame. You may be right; your partner may be too inhibited or rejecting to give you what you need. But the problem may reside within you.

There are a number of ways in which you may be undermining your love life at home. Let’s look at four of them.

1. You continue to make unfair and unproductive comparisons between your partner and your lover. This is a contest you need to stop. As long as you expect prescribed sex with your partner to compete with proscribed sex with your lover, you’re going to be disappointed and excuse yourself from the real task at hand: revitalizing your love life at home. Yes, sex is usually hotter and spicier in an unfamiliar bed, but so what? Passion cools, disenchantment follows; if you had stayed with the affair-person, you probably would have run up against many of the same intimacy problems you’re having now with your partner. Familiarity can breed boredom, even contempt. This is a reality you need to confront, whoever your partner is.

2. You fail to nourish intimacy outside the bedroom. If you don’t make your partner feel valued and loved outside the bedroom, how can you expect your partner to warm up to you inside the bedroom? Before you complain about your sex life, you should show your partner at least as much tenderness and regard as you lavished on the affair-person.

No one could accuse Chuck of such sensitivity. When he got home from work, he typically left his wife to bathe the two kids, read to them, and tuck them into bed, while he chortled on the phone with his business manager. When his wife finally crawled under the covers, he was waiting for her, bathed and ready for sex. “By that time, I was so furious at him,” she told me, “the last thing I wanted was for him to touch me. He accused me of being frigid—and I was—but he never understood how cold his self-centeredness made me feel.”

3. You don’t know how to arouse your partner. As great a lover as you may fancy yourself, you may have no clue how your partner needs to be stimulated to become aroused. Though you assail your mate for being unresponsive, the problem may be that you’re pushing the wrong buttons, and your partner, knowing how sensitive you are to criticism, is afraid to give you corrective feedback. If you want to be a better lover and improve your sex life, you need to consult the real expert—your partner—and ask for a lesson.

4. You blame your partner for your own sexual or intimacy problems, which predate your relationship. It’s so much easier to point a finger at your partner than to look in the mirror and ask yourself how you’ve contributed to your sexual dissatisfaction. It’s unfair, though, to fault your partner alone for making you feel unesteemed, unsexy, or inadequate, when you’ve felt this way for as long as you remember.

1. If you’re plagued with thoughts about the affair-person, try the thought-stopping technique I recommended earlier. As soon as you find yourself obsessing, break your concentration by calling out “Stop,” or some similar expression, and diverting your attention to another subject.

2. Instead of focusing on the affair-person, explore what it was about your experience with that person that affected you in such a powerful way. Did you feel young, potent, wanted, alive? These may be clues into vulnerabilities and yearnings you need to address if you’re going to be satisfied in any relationship.

3. Use the Dysfunctional Thought Form in this chapter to challenge your unrealistic ideas about love and romance.

4. Learn to broaden your concept of intimacy beyond the thrill of sex.

These “should” statements are so unrealistic and self-defeating that they’re bound to put your sex life on ice; by the time it thaws, one of you is likely to be gone. If you expect to feel relaxed in bed now, you’re dreaming. What’s more likely is that you’re feeling nakedly self-conscious—stripped of your defenses and embarrassed in each other’s presence.

“So what do I do?” you ask. “Submit to something I feel unready for, that may give me more discomfort than pleasure?”

Yes, exactly. Intimacy building is an active process. It requires a conscious attitude, a deliberate choice, a cognitive decision to get more closely connected. The process begins when you decide to begin, not necessarily when you feel motivated, confident, or certain. You can’t just wait around, asking yourself, “How can I open myself up to someone I have such conflicting feelings toward? How can I be intimate with someone who has caused me so much harm?” You need to go beyond these feelings, take chances, and engage each other physically. Becoming more intimate outside the bedroom may help restore trust, but it doesn’t automatically translate into greater sexual intimacy. You need to take your partner’s hand, caress, kiss, and allow feelings of intimacy to flow between you. You need to begin acting not according to the way you feel but according to the way you would like to feel.

Reaching out to each other may leave you feeling vulnerable; sealing yourself off may make you feel safe. I urge you, however, not to wait until you’re more comfortable before you begin to touch again; comfort comes with an accumulation of healing experiences, not with time. Getting physical is likely to feel awkward at first, but awkward is exactly what you should be feeling as you demonstrate your willingness to stretch emotionally and take risks. Reenacting old, familiar patterns—avoiding intimacy, maintaining a barrier of distrust—may feel comfortable, but is often highly dysfunctional.

1. I can’t stress this point strongly enough: To get closer, you have to begin touching again. You might begin by telling each other, face to face or on paper, exactly how you would like to be touched. Your requests are likely to be very idiosyncratic, so don’t expect what pleases you to necessarily please your partner. Try to satisfy at least one of your partner’s requests every day.

Common examples include:

• “When you come into the house, kiss me on the mouth.”

• “Take my hand when we walk.”

• “Rub my feet with oil.”

• “Give me a massage.”

• “Hug me for a few moments.”

• “Sleep or lie near me with one arm around me.”

• “Run your fingertips gently over my eyelids and eyebrows in bed.”

• “Brush my hair.”

• “Stay in bed with me for a few minutes after the alarm goes off; lie in my arms with your face close to mine.”

• “Touch my shoulder or waist when you walk with me.”

2. Sex therapist Warwick Williams suggests that couples work out a “physical trust position” in bed. You begin by agreeing on one or two positions that both of you find safe, and then experiment. The idea is to combine physical closeness and trust. Among the positions Williams recommends are:

• One of you curls up on your side while your partner holds you from behind (the “spoons” position).

• You both lie on your sides, facing each other, holding hands (you may want to hug or close your eyes).

• One of you sits up, comfortably supported, cradling your partner’s head in your lap, and stroking your partner’s hair.5

You can talk or not, wear clothes or not, have sex or not. The idea at this point is to reestablish physical contact and engender trust. Remember: You can only get so close to someone you don’t touch.

You may worry that once you begin to touch, your partner will ignore the limits you set, turn up the heat, and try to force a simmer into a boil. Not wanting to go further than feels comfortable to you, you put up barriers, and forfeit an opportunity for closeness.

“After I found out about Jeff’s affair, he kept wanting to make love, but I wouldn’t let him near me,” Leah told me. “I even made him sleep in the guest bedroom. The truth is, I wanted to feel him next to me, to fall asleep with his arms around me, but I didn’t trust that he’d stop there, and I wasn’t ready for anything more. To make love meant, ‘I’ve forgiven you. Everything’s fine now between us.’ And it wasn’t. I suppose I was testing him. If I refused to have sex with him and he went elsewhere, I’d know he wasn’t truly repentant and didn’t really love me for myself. After what he did, I earned the right to make him prove himself.”

Jeff saw Leah’s behavior in a different light. To him, she was being manipulative—pushing him away to control and punish him despite his genuine efforts to convince her of his commitment. His frustration turned to anger. To protect his self-esteem, he stopped initiating sex. Both partners felt alone and trapped. (In the next section, we’ll see how they resolved this dilemma.)

While you, like Leah, may not feel ready for intercourse, you need to decide what you are ready for. Sex and celibacy are not the only choices. Remember, to rebuild intimacy you have to get physically connected again. Withholding sex may help you regain the power or equity that you lost because of the affair, but power and equity make poor bedfellows. A scale tipped in your favor is still off balance.

While you, like Jeff, may love to make love, you may need to agree to your partner’s timetable while the two of you rebuild trust and intimacy in other ways.

1. You need to tell each other what feels comfortable sexually, and then prove to each other that you respect each other’s limits. Find some concrete way of signaling when you only want to touch or when you want more. One couple came up with their own playful solution: The aroused partner took a ceramic frog they had bought on their honeymoon and placed it on the other’s night table; the “invited” spouse was free to take the leap or not. Another couple decided that since it was the hurt partner who felt more ambivalent and vulnerable, that person, for now, would always be the one to initiate genital sex.

2. A popular exercise called “sensate focus”6 may help you to begin touching again and to learn how you like to be touched, while eliminating the pressure to feel aroused, perform any specific sexual acts, have intercourse, or reach climax, until you’re both ready. Set aside an agreed-upon amount of time—I suggest fifteen to twenty minutes, no longer—during which one of you massages or touches the other in nongenital areas. Both of you should be fully clothed. The next time, reverse roles, one person always giving pleasure, the other always receiving it. The person receiving pleasure need not say or do anything except to signal occasionally in some way—lifting a finger, saying “mmm”—when the touching feels good.

When you’re comfortable with this exercise, you can try it with your clothes off, but again without genital touching. That comes next, with the understanding that before you agree to intercourse, both of you have to give the green light—the frog—first.

Now is a good time to discuss your attitudes about masturbation. No topic comes packaged with more myths, ranging from the idea that touching yourself causes pimples to the notion that it permanently alters the size, shape, and color of your genitals and saps your ability to have good sex. Though masturbation is still condemned by various religious and cultural groups, most people do it at some time in their lives, though they tend to conceal it. In a study of twenty-four couples reported in The Kinsey Institute New Report on Sex, 92 percent of the husbands and 8 percent of the wives believed their spouses never touched themselves, when in fact all of them did.7 Among the thousands of people interviewed by Kinsey in the 1940s and 1950s, some 94 percent of males and 40 percent of females admitted having masturbated to orgasm. More recent studies have corroborated these figures for men, but found that the percentage of females who masturbate has increased to around 84 percent.8 Most couples reported that masturbation did not make them feel less loving toward their partner, or detract from the quality of their lovemaking, but served as a supplemental component of a sexually active lifestyle.9 Another recent study of sexual habits in America reported that, of men and women between the ages of twenty-four and forty-nine, 85 percent of the men and 45 percent of the women who were living with a partner said they had masturbated during the past year.10 Of those people who had regular partners for sexual intercourse, one man in four and one woman in ten said they masturbated at least once a week.11 The same study reported that married people were more likely to masturbate than people who were living alone.12

Let’s return to our couple, Leah and Jeff, who were struggling to set boundaries for touching in the previous section. One night Leah walked in on Jeff and found him masturbating. She became terribly upset and accused him of behaving like an animal. Jeff didn’t know whether he was more embarrassed or annoyed. “It’s better than sleeping around,” he told her. “Sleeping with you doesn’t seem to be an option.”

Leah thought about Jeff’s response, and later, in a couples session, told him that she resented the pressure he put on her to make love whenever they touched.

“Fine,” he said, “but you’ve got to give me some other outlet.”

“Your masturbating scares me,” she explained. “It’s another secret, another way you have of keeping yourself from me and showing that you don’t need me.”

“That’s not what it means to me,” Jeff said. “I see it as a healthy alternative to forcing myself on you or getting satisfied elsewhere. What else do you suggest?”

The solution they came up with was that they would sleep in the same bed, but Jeff would respect Leah’s need to postpone intercourse. Leah, in turn, agreed to hold Jeff and kiss him as he touched himself. The compromise seemed to work. At the next session Leah told me, “Being there together takes the threat away, and I’m glad to have him back in bed with me. It’s not ideal but it’s better than where we were.”

As a couple, it’s important that you find mutually agreeable sexual options. Don’t set traps for each other or issue ultimatums; set alternatives. Try to keep an open mind about what should happen sexually between you, and be creative about satisfying each other’s needs for closeness and sexual release. What matters most is not that you engage in any particular sexual act, but that you problem-solve as friends and build a sense of partnership.

This idea reflects an idealized, romantic standard that’s impossible to meet on a consistent basis. Imposing it on an already fragile relationship is bound to leave you feeling disappointed, insecure, and critical of yourself and your partner. The reality is that sex after an affair will probably not be passionate, but graceless and trying. Hurt partners are unlikely to act with abandon when they fear being abandoned. Unfaithful partners, as we’ve seen, are likely to be inhibited by the pressure to perform, and distracted by memories of the affair-person.

What you should both keep in mind is that, given what you’ve been through, any kind of touching, with or without genital sex, can be incredibly intimate and courageous. Don’t heap so much onto a fire that’s just trying to catch hold. The emphasis now should be less on producing a high flame than on allowing yourself to rekindle tender feelings.

After her husband admitted sleeping with his friend’s wife, Carol wanted their lovemaking to be white-hot. When it fell short of her expectations, she felt frightened and let down. “Nothing is clicking,” she told me. “We’re just going through the motions. Something’s very wrong.”

What was wrong was not the sex, but Carol’s extravagant notion that she and her husband must feel some intensely erotic connection at all times. This unreasonable expectation made it impossible for her to enjoy or even find comfort in the pleasure he gave her.

Carol’s experience was further contaminated by the personal meaning she attached to passionate love: that it proved her attractiveness and desirability in the eyes of her husband. Passion assumed an overcharged importance because she looked to it for reassurance of her specialness to her spouse. Lovemaking, to her, was not a way to reconnect but a chore, a performance, a test. How could it not disappoint her?

If you, like Carol, need to have a “ten” experience in bed, you’re likely to have nothing more than a “three.” Sex in movies and magazines is often portrayed as a fiery furnace when in real life it’s more like central heating with an irregular thermostat.13 To make your sexual relationship warm and loving you need to take off more than your clothes, you need to shed your exacting expectations.

1. Ask yourself, “Why is passion so important to me? What meaning do I assign to it that it seems so weighted with importance? Does it signify that my partner is genuinely happy to be with me? Finds me attractive? Is less likely to stray? Has forgiven me?”

It may take the pressure off you to realize that these and other meanings are subjective—that a passive partner may be happy, faithful, and forgiving, and that a sexually aggressive partner may be miserable, unfaithful, and condemning. By reframing the meaning of passion, you may be able to accept and enjoy lovemaking that’s less intense than you dreamed it might be, but just as loving.

2. Work on developing an expanded, more useful, and realistic definition of intimacy that goes beyond high chemistry and includes feeling of tenderness, caring, understanding, and respect.

3. One of the greatest sexual turn-ons is a turned-on partner. Conversely, one of the biggest turn-offs is a partner who is sexually dead. It follows that if you want more passion from your partner, you need to be more passionate yourself.

This idea is convenient because it lets you dump the burden of responsibility for your sexual satisfaction in your partner’s lap and then blame your partner when your needs aren’t met. Nothing could be more dysfunctional, since those needs will remain unknown until you speak up.

My prescription, then, is this: If you want to be more satisfied in bed, you need to take a more active role in making it happen—it’s not a job for your partner alone.

I invite you to:

• become an expert in what your body likes;

• convey this information with sensitivity and candor;

• respond to your partner’s efforts to please you, however fumbling, in a complimentary and encouraging way.

Phil, a forty-three-year-old antiques dealer, had mastered the maladaptive pattern of holding his wife responsible for intuiting his needs, then holding her in silent contempt when they weren’t met. “Last night Susan held my face tightly in her hands, and I realized just how much I hate it when she does that,” he told me. “It reminds me of my mother. She must know it drives me crazy, but she’s been doing it since the day we met.”

Phil confronted his response on a Dysfunctional Thought Form. “Why must she know?” he wrote. “You’ve never told her. You never told anyone. You keep everything to yourself and then complain that no one understands you. You’ve done this your whole life, first with your mother and now with Susan. Let her know what you like. Give her a chance to please you. In your heart you know she wants to.”

Many of you, like Phil, have trouble telling your partner what you want physically—you think you’re not worth it, you’re worried about getting rejected or reproached, you’re afraid to hurt your partner’s feelings, you’re stuck in the belief that “if I have to ask, it’s no good.” It would be wonderful, of course, if your partner could always intuit what you want and give it to you freely. The problem is that no one can read your mind. At times like this, when you’re feeling so estranged, you need to learn to be direct and assertive, more there for yourself.

1. Sometimes it’s best to communicate your needs by example rather than words—to show your partner exactly what feels good to you. Men can demonstrate how they like oral sex, for instance, by sucking their partner’s finger, and women, by kissing their partner’s mouth. The idea is to go beyond language, to touch your partner in erotic or playful ways, and give this person a chance to feel what you would like to feel.

2. Name two irksome things your partner does in bed that you’ve complained about in the past. One of my patients told her husband, “You squeeze my nipples even though I’ve told you this hurts me, and you bury your chin bone in my neck when you’re on top of me.” Her husband explained that when they made love, he got absorbed in the moment and didn’t realize he was hurting her. He seemed more than willing to change.

3. Take notice of those times when you want to ask your partner to please you, but don’t. Write down whether you believe your silence is worthwhile, how it makes you feel, what it accomplishes. Do the same when you speak up. Try to make your partner aware of your struggle, and ask for encouragement in communicating what matters to you.

What could be more delicate than asking for, or agreeing to, new sexual behaviors—a different way of touching, say, or a new position or technique? Those of you who want changes may say nothing for fear of upsetting your partner and causing a further rupture in your relationship. Those of you who are asked to change may refuse, feeling insulted or manipulated into doing something that violates you. Is it any wonder that you both stay stuck in the past, dancing the old unbeautiful dance?

“I want Tim to know that I’ve never been able to climax through intercourse, that I much prefer oral sex,” Carol told me, “but if I tell him, I’m afraid he’ll think he’s a lousy lover and try to prove himself again with someone else. I’m willing to fake orgasms to keep him around.”

Tim had his own secret. “Lisa [the affair-person] did something incredible that I wish Carol would do,” he told me. “She moved her pelvis up into mine while we were making love, as though she were meeting me halfway. It made me feel wanted. Carol just lies there, like she’s sacrificing herself. Whether she’s angry at me, embarrassed to be physically aggressive, or just bored, I have no idea. I’d love to tell her what I want, but she’d know I learned it from Lisa. It doesn’t seem worth it, making her feel more insecure than she already does.”

You, like Tim and Carol, may decide to keep your sexual wishes to yourself and not risk provoking an ugly confrontation. But your silence is likely to increase the emotional distance between you, even more than your lackluster sex life.

A peaceful facade is no substitute for intimacy. Hiding what you want may protect your partner’s feelings, but if your goal is getting closer, not just getting by, you have to voice what matters to you, even if the truth stings. In the end you may discover that your partner wishes you had spoken up sooner, and welcomes the chance to satisfy you.

Asking for sexual changes won’t bring you closer unless you’re also willing to entertain them. I don’t mean necessarily agreeing to the changes your partner wants, but being willing to consider them with an open mind.

That’s what a patient named Marilyn refused to do. When her unfaithful husband asked her to douche so he could enjoy cunnilingus with her, she flashed back, “My vagina is a self-cleaning oven. If you don’t like the way it smells, get your nose out of there.”

Your resistance to change, like Marilyn’s, may be understandable, but it may deprive you of an experience that could bring you both pleasure, and move you closer together. If your partner is making genuine efforts to become more sexually intimate, and backing them with loving gestures outside the bedroom, I suggest that you view requests for change not as criticism, a put-down, or an unflattering comparison with the affair-person, but as a gift in service of your relationship.

At the same time, you shouldn’t agree too quickly to changes that seem repugnant or premature, or that otherwise seem to compromise your integrity or well-being. “The idea of oral sex has always made me gag,” one straying partner told me. “But I feel I’ve got to do it to convince my husband I’m back for good.” “My husband wanted sexual surprises,” a hurt partner explained, “so I met him at the airport wearing nothing but a raincoat. He got an enormous kick out of it, but I never felt so cheap in my life. I had gone too far.”

It’s not reconstructive for you, the unfaithful one, to satisfy your partner only from a sense of guilt, or for you, the hurt one, to satisfy your partner only from feelings of insecurity and a desperate wish to please. Neither of you should feel you have to respond sexually just to prove your love or commitment. Both of you need to respect each other’s right to say no.

To help you communicate your sexual preferences, I encourage you to share your responses to the following list of behaviors, which many partners consider pleasing. Rate each behavior on a scale of one to three: one = not pleasing; two = somewhat pleasing; three = very pleasing. Be sure to add your own requests to the list, in language that is positive and specific, not negative and global. Saying, “I hate how fast you move into intercourse,” is less helpful than, “I’d like you to kiss and stroke me for at least ten minutes before we go further.” Remember, communicating what pleases you only informs and directs your partner, it doesn’t require your partner to do it.

I would like you to:

Partner A |

Partner B |

|

__________ |

__________ |

come to bed bathed and smelling clean. |

__________ |

__________ |

take a shower with me before we get into bed. |

__________ |

__________ |

brush your teeth before coming to bed. |

__________ |

__________ |

stop smoking cigarettes a few hours before we get into bed, and use mouthwash. |

__________ |

__________ |

wrap your legs around me when I enter you. |

__________ |

__________ |

lick my ear, finger, nipple … in this way (explain). |

__________ |

__________ |

ask me to show you how I want to be touched. |

__________ |

__________ |

kiss me on the mouth for a while before touching my genitals. |

__________ |

__________ |

run your fingertips lightly over my body. |

__________ |

__________ |

reassure me that I’m not taking too long to reach orgasm. |

__________ |

__________ |

be patient with me and make me feel you want me to come, even after you’ve come. |

__________ |

__________ |

gently stroke my testicles. |

__________ |

__________ |

use lubrication on my clitoris. |

__________ |

__________ |

suggest we make love in a new place. |

__________ |

__________ |

put on romantic, relaxing music. |

__________ |

__________ |

dance with me slowly before we get into bed. |

__________ |

__________ |

whisper in my ear how much you love me. |

__________ |

__________ |

talk dirty to me. |

__________ |

__________ |

come to bed naked. |

__________ |

__________ |

come to bed wearing something sexy. |

__________ |

__________ |

come on to me when you feel aroused (don’t just ask me if I’m interested). |

__________ |

__________ |

ask how I feel before you come on to me. |

__________ |

__________ |

make love to me in front of the fireplace. |

__________ |

__________ |

snuggle with me in bed for at least ten minutes after we make love. |

__________ |

__________ |

stimulate me orally while I do the same to you. |

__________ |

__________ |

show me how I can please you orally in ways that are acceptable to me. |

When I ask my patients, “Do you believe any of these ‘should’ statements?” many say, “Don’t be ridiculous.” Yet when these expectations aren’t fulfilled, these same people are often disappointed. When I ask why, they respond, “Well, I don’t believe these ideas intellectually, but I believe them emotionally,” or “I don’t believe them for others, but I do for myself.”

The fact is, many of you hold yourselves to relentlessly high sexual standards. It’s no wonder that lack of sexual desire is the common cold of sexual disorders: Who has the energy to start when the finish line is beyond reach?

One of the most common misconceptions is that women who are uninhibited or sufficiently aroused not only should be able to reach vaginal orgasm, but prefer it to manual or oral stimulation.14 In reality, most women, anatomically, don’t get the clitoral stimulation they need through intercourse alone, and therefore cannot reach orgasm this way—ever.

Men, too, often find that they need or prefer other kinds of stimulation than what they get through intercourse, but they’re ashamed to admit it. This overemphasis on orgasm through intercourse puts pressure on them to make it happen. When it doesn’t, they’re often left worrying that they’ll never get their needs met with their partner, or that there’s something deficient about themselves or their bodies.

Jerry blamed himself for never being able to bring his wife to orgasm. “For years I believed Ann couldn’t come because of me,” he told me. “I wasn’t big enough, I came too soon, the chemistry wasn’t right. My own negative feelings about my performance—about myself—were one reason I had an affair with Sally. She came to climax so quickly through intercourse—it made me feel virile, and vindicated. But as we spent time together, she let me know she needed other kinds of stimulation and taught me things about a woman’s anatomy I was totally ignorant about. I couldn’t believe how little my wife and I knew about our bodies—about how to give and receive pleasure. I realized I had run away from our sexual difficulties; I might not have, if I had seen them as problems to be solved.”

Another unrealistic idea is that you should reach orgasm every time you make love. According to one of the most recent national sex surveys, most Americans fantasize about the incredible sex in other people’s lives, and have an exaggerated sense of what is normal. The study found: “Despite the fascination with orgasms, despite the popular notion that frequent orgasms are essential to a happy sex life, there was not a strong relationship between having orgasms and having a satisfying sexual life.” Some 75 percent of men said they always reached orgasm during sex with their partners, while only 29 percent of women said they always did. Yet the percentage of men and women who reported being extremely satisfied both physically and emotionally was equal—40 percent. As the researchers point out, orgasm could not be the only key to sexual fulfillment, or men and women would have reported different levels of satisfaction.15

What often matters as much as orgasm are your ideas about orgasm. Rigid, unrealistic expectations are likely to leave you feeling frustrated, dissatisfied, and defective. You’re more apt to have a loving, intimate experience when you emphasize the process rather than the results. As British writer Leonard Woolf pointed out, it’s the journey, not the arrival, that matters.

Let your partner know how you’d like to reach orgasm, and give up the notion that there’s one superior way—through the magnificent penis.

If you, as a woman, want to climax through intercourse but have been unable to, try stimulating your clitoris while your partner enters you either from above (holding himself slightly over you) or from the side (lying behind you). It may help to use lubrication, saliva, or gel; the notion that there’s something shameful about needing lubrication is another popular misconception.

If, as a man, you have difficulty reaching orgasm through intercourse, try lying on your back and having your partner stimulate you orally, manually, or with a vibrator. You can also touch yourself while your partner strokes your testicles or kisses your nipples. What may be causing your problem is your attitude that real men come only through intercourse.

Both of you, men and women, need to figure out what makes sex pleasurable for you—what works, what doesn’t—and adopt a nonevaluative attitude that says, “Any way we reach orgasm is fine and perfectly normal as long as we both feel comfortable with it. There’s no one right or better way.”

Listen to your bodies. They’ll tell you what they like.

After an affair, prepare yourselves for sudden and seemingly inexplicable shifts in levels of sexual desire. Unfaithful partners may completely lose interest in sex while hurt partners may experience a magnified need for it to overcome their doubts about themselves as lovers. The opposite is also true: Unfaithful partners may be hungry to resume sexual relations, while hurt partners may feel afraid to risk such intensity of feeling.

One hurt partner, Barbara, found that after her husband’s affair she had an insatiable need to make love. “I want to wear him out so he won’t have the energy for anyone else,” she told me. “I want to prove to him that I can make him happy, that I can be as hot as his lover.”

Her husband didn’t know how to react. “I’m trying to strike a balance,” he told me, “sometimes giving in to her, even when I have no desire, just to make her feel secure; sometimes telling her I’m not up for sex but reassuring her of my commitment and love. But when she senses I’m not totally interested, she starts wondering why. We always enjoyed each other in bed, but this neediness of hers is putting me off.”

One unfaithful partner, Bob, went into a protective shell after revealing his affair and lost all sexual desire, not just for his wife but for anyone. He stopped masturbating as well. “I’ve just shut down sexually,” he told me. “Maybe this is my way of punishing myself for what I’ve done, of controlling my urges so they don’t get out of hand again.”

At first, his wife worried that he had lost interest in her. Then she worried that when his interest returned, he would leave again.

As with these two couples—Barbara and her husband, Bob and his wife—your satisfaction with your partner may have less to do with different levels of desire than with your assumptions about them. If you believe that two sexually compatible people should want to make love with the same frequency 100 percent of the time, you’re likely to be alarmed by your differences and go in search of satisfaction elsewhere. If you believe that two people rarely have the same physical needs at any given moment, you’re likely to be more tolerant of your differences and negotiate them within the confines of your relationship.

The pressure to match your partner’s needs is compounded when you’re both a woman and the hurt partner. Pop culture tells you it’s your job to satisfy the man or he’ll replace you. “Thus it falls to the wife to match his [her husband’s] ‘drive,’ pretend to match it, or suffer a penalty,” writes Dr. Thelma Jean Goodrich. “Even in therapy, the wife’s deviation from the husband’s ‘drive’ is typically seen as the problem to solve.” When your husband invites you to make love, therefore, you may want to check in with yourself and ask, “Am I answering with a good wife voice, a scared voice, or my own voice?” Your partner, in turn, should question, “Is my wife having sex as a kindness to me, out of fear of losing me, or out of her own desire?”16

There is nothing maladaptive about accommodating to your partner’s sexual timetable as long as it doesn’t make you feel compromised, coerced, or resentful, and you’re not alone in working to rebuild the partnership. I see nothing dysfunctional in you, the betrayed wife, having sex at times to please your husband, even out of fear of losing him, as long as he’s trying to make you feel more secure and loved. What is unacceptable is when one of you always ignores the other’s rights and privileges, or accedes to the other’s needs. Relationships seldom thrive without a spirit of equity and reciprocity.

Keep in mind that your level of sexual desire will vacillate throughout your life, regardless of your gender or your role in the affair. As we age, we experience normal fluctuations in desire caused by hormonal changes. Men typically reach their peak frequency of sexual expression between mid-adolescence and their mid-twenties, at which point it gradually declines. Women reach their sexual peak later—typically between ages thirty and forty, usually followed by a gradual decline that continues until old age, with perhaps an increase in desire for at least a few years after menopause.17

Transitional life events also influence your levels of sexual desire. “I felt like a sexual nonentity after my child was born,” a patient named Betty told me. “I became the milkman, nursing day and night, totally bent on giving my baby a healthy start. Sex was the last thing on my mind. Eric [my husband] infuriated me, constantly pressuring me to come to bed with him—he seemed to need me more than the baby did—and I hated it when he fondled my breasts. Now, eighteen years later, the baby’s in college and the tables are turned. Eric’s working overtime to make ends meet, and I’m more hot to trot than he is.”

Nothing may feel more alienating than your partner’s lack of desire, but your tendency to read the worst into it will only push you further apart. I encourage you to look beyond your partner’s apparent disinterest, beyond your own immediate needs, and work out a way of sustaining intimacy despite your periodic disappointment or frustration. Part of becoming intimate is learning to remain attached to your partner in caring ways, even when your partner can’t or won’t satisfy your every desire.

Distressed partners often develop polarized perceptions of each other’s sexual responsiveness; one person is seen as a stone, never wanting sex; the other is seen as a rabbit, constantly wanting it. This exercise—I call it “the Rabbit and the Stone”—will help you develop a more realistic sense of each other’s sexual desires, and reach a compromise that satisfies both of you.

First, I’d like each of you to write down how often you ideally would like to have sex (meaning if you weren’t influenced by how often you believe your partner wants it), and how often you believe your partner ideally would like it. Then, write down the frequency level you would be willing to settle for (meaning how often you would be willing to have sex to accommodate your partner). Next, write down the frequency level you believe your partner would settle for. What the two of you are likely to discover from this exercise is that your range of responses is narrower than you expected, and that a solution agreeable to both of you requires less compromise than you feared.

Here’s what one couple, Valerie and Todd, found:

1. How often does Valerie want sex?

Valerie’s response: once a week.

Todd’s response: once a month.

2. How often would Valerie settle for?

Valerie’s response: once or twice a week.

Todd’s response: twice a month.

3. How often does Todd want sex?

Valerie’s response: every day.

Todd’s response: two or three times a week.

4. How often would Todd settle for?

Valerie’s response: three times a week.

Todd’s response: once a week.

The couple found themselves laughing at their mistaken notions about each other, and arrived at the following compromise: They would have sex at least once every five days to satisfy Todd’s level of interest, but not more than that, in deference to Valerie’s (unless she wanted to). Each partner was responsible for initiating sex every other time. When it was Todd’s turn, he usually approached Valerie that same evening; she often waited the full five days. It was agreed that if either of them refused to do as promised, that person would think through his or her objections on a Dysfunctional Thought Form, discuss them with the other partner, and set another date.

Once, when Valerie wanted an extension, she wrote down the following negative thoughts: “I’m angry. When his mother came to visit, he dumped her in my lap even though I had a report that was overdue. He doesn’t value my time and expects everyone to bow down to his schedule.”

She then talked back to herself: “You’ve been nursing your resentment all week—why are you withholding sex now? You need to confront Todd as soon as you get angry with him and give him a chance to address what’s bothering you. Don’t fall into the trap of turning Todd into your father, who always put himself first, and becoming your mother, who stayed with Dad only for your sake and cloaked her rage in coldness. Tell him what’s upsetting you, as you do in therapy, and ask him to mirror your feelings. Then do the same for him. Don’t use sex as a weapon. If you’re direct, he’s more likely to support you.”

Instead of pushing Todd away, Valerie listened to her more resourceful self and explained her anger and acknowledged her own dysfunctional behavior patterns. On the fifth day she initiated lovemaking, as she had agreed.

Many of you are likely to believe that the only proper way to have sex is with both of you focused on, and being stimulated by, each other. Normal people, you assume, should not need or want sexual gadgets or mental machinations to get aroused.

Conversely, you’re apt to believe that if you like or need sexual enhancers—vibrators, X-rated videos, and so on—your relationship is in trouble or you’re perverted, cheap, disloyal, strange, or sick.

The fact is that there are as many different ways to arouse your body as there are to cook a chicken—probably more. The problem with rigid proscriptions for sexual behavior is that they’re likely to close you off from some of the most playful and sensuous aspects of lovemaking. And at a time when your relationship is so strained, playfulness and sensuality should not be dismissed lightly.

It’s been said that the most important sex organ is the brain, because what goes on in your head significantly affects your body’s sexual responses. If, while making love, you fill your mind with thoughts that are spicy, even forbidden, you’re more likely to get aroused than if you’re thinking, “My partner never puts his dishes in the dishwasher.” That’s unlikely to work up much of a lather.

Sexual fantasy is a natural activity that can distract you from your anger, your feelings of inadequacy, your thoughts about the affair-person—whatever it is that interferes with your arousal at this complicated time. It can also enhance your sexual responsiveness by sending messages to those organs that activate penile erection or vaginal lubrication.

“But shouldn’t my partner be enough for me?” you ask. “Isn’t it obscene to be thinking of someone else while I’m making love with my partner?” No, I would say, there’s a difference between thinking about sex with others and having sex with them. As well-known sex therapists Heiman, LoPiccolo, and LoPiccolo point out, “Fantasizing about something does not mean that you will actually do it. In fact, the beauty of fantasy is that it allows you the freedom to experiment with sexual variety beyond the limits of reality.”18 The idea that if you loved someone you would never be attracted to, or think of making love with, anyone else goes against human nature. It’s normal to have sexual thoughts about other people. What’s important is that you and your partner look forward to lovemaking, that you make your time in bed together rewarding, enjoyable, intimate, fun; and if that includes fantasy—fine.

I would just not advise either one of you to fantasize about the affair-person, though it’s unrealistic to think this won’t happen. You, the unfaithful partner, have acted on these fantasies before, so it’s best not to nourish them. You, the hurt partner, may actually be aroused by images of your partner in passionate embrace with another person, but these mind videos are also likely to ignite your insecurity, even if at times you find them highly erotic. When you tune in to the affair-person, it’s time to change channels.

One way to do this is to train yourself to conjure up other, less threatening images. Men in Love19 and My Secret Garden,20 both by Nancy Friday, are filled with explicit and provocative sexual fantasies, the first by men, the second by women. Some of them may turn you on.

Another way to heighten arousal is to incorporate sexual devices in your lovemaking. Some of you are bound to recoil at this suggestion because of the meaning you ascribe to it. If you’re ever to enjoy these enhancers, you need to see them in a new light, as John, one of my patients, did.

As he and his wife, Judy, were recovering from the damage of his infidelity, she revealed that during their months of separation she had begun using a vibrator and now wanted to continue using it to intensify her orgasms during intercourse. John took her request as a slap in the face. “She’s trying to get back at me for my affair,” he told me. “It’s like she’s saying, ‘I can replace you just as easily as you replaced me.’”

Judy explained that she loved making love with him but couldn’t reach orgasm through vaginal stimulation alone and wanted him to touch her and stay close to her while she used the vibrator. John resisted at first, but over time, after talking it over and reshaping its meaning in his own mind, he came to accept it. At times he even got aroused watching her pleasure herself.

A hurt partner named Marge came to a similar accommodation with her spouse. Since she could see that he was working to revitalize their marriage, she struggled not to feel demeaned by his wish for visual stimulation. When he asked her to slip into the black lace teddy he had bought her and watch an X-rated movie with him, she agreed. But the next day she felt cheap. “He needs these toys to keep him aroused,” she told me. “They have nothing to do with me. If he loved me and enjoyed my body, I’d be enough for him.”

With help, Marge recognized the subjectivity of her assumptions, and talked back to them. “He bought me this silly, pretty thing before he had his affair,” she told herself. “He’s always liked to see me in sexy clothes. And he’s always liked porn. That doesn’t make him bad, and it doesn’t make me less attractive or less loved by him. Why read something into it that isn’t there?”

Ultimately, what created the most intimacy for Marge and her husband was not their use of any particular sexual enhancer, but their willingness to consider each other’s idiosyncratic sexual preferences without passing judgment on them.

1. Take time to develop one or two provocative fantasies that you feel comfortable summoning up while you’re having sex. You can begin by using them while you masturbate or as you touch your body in the shower.

When you incorporate a fantasy into your lovemaking, try to move back and forth in your mind between the fantasy and the sensations you’re experiencing with your partner. Don’t get totally lost in your dream world, but don’t hesitate to drift into it when you’re having disruptive thoughts about your partner or the affair-person.

Have fun with this and try to let your mind go, dreaming up scenes that excite you. What makes fantasy exciting is its forbiddenness or novelty; what may work best for you are scenes that you would find frightening or morally repugnant in real life. Remember, your partner never needs to know you use fantasy or what your fantasy is. An extramarital fantasy is not an extramarital affair. I talk more about this in chapter 10 on affairs in cyberspace.

2. Invite your partner to visit a sex shop with you on- or offline. Some of the items may disgust you, others may make you laugh. Talk about the ones you would like to try. Share your feelings about them.

In renewing your physical relationship, you’re both bound to confront one of the most anxiety-riddled, post-infidelity sex issues—concern over sexually transmitted diseases such as AIDS.

Though you, the unfaithful partner, may insist that you had safe sex with the affair-person, your partner is likely to need more proof than your word and refuse to have genital sex with you until you both pass medical tests. If you resist this injunction, you’re dead wrong and need to ask yourself why you’re feeling so defensive. The meaning you attach to your partner’s demand may agitate you, particularly if you see it as an attempt to control or punish you, but no matter how offensive your partner’s intentions may seem, you have no moral right to expose another person to a disabling or fatal disease. I offer the following mindset to help you follow through: “AIDS [or any other sexually transmitted disease] is real, prevalent, and life-threatening. It’s indefensible to put someone else’s life at risk. Getting tested is a way of demonstrating my respect for my partner’s feelings and my commitment to our relationship. I can choose to see my partner’s demand as coercion, or I can choose to see how pathetically selfless and dependent my partner would have to be to agree to sex without knowing my health status. Besides, why should my partner trust my word that I’ve had safe sex when I’ve lied [so many times] before?”

You, the hurt partner, certainly have the right to ask your partner to be tested; in fact, it’s the only responsible thing to do. But try not to use your request as a vehicle for avoiding intimate contact or of conveying your rage or anguish. If you’re worried about your health, speak up. Give your partner a chance to allay your anxieties and earn back your trust.

Get tested—both of you. Tell your partner when you have made an appointment, and then share the results. Don’t put your partner in the position of having to nag you.

Shame often stands in the way of greater intimacy—shame about the way your body looks and shame about the way it performs. When you lock these feelings up inside you, they inhibit you from going with your natural inclinations and openly enjoying and expressing yourself in bed. To draw closer together, you need to identify what you feel ashamed about, and then risk talking about it. Revealing your deepest, darkest, most shame-laden ideas about your sexual self is bound to make you feel vulnerable, but it will give your partner a chance to contradict your assumptions and accept you for the way you are. Shame needs to be aired to be exorcised.

Here’s a list of ideas or facts that many partners admit to feeling ashamed or embarrassed about. I encourage you to discuss them and add your own:

• “My body is ugly.”

• “My breasts are too small/big.”

• “My penis is too small/big.”

• “I don’t get hard enough.”

• “My penis has a weird shape.”

• “My nipples are inverted.”

• “I can’t reach orgasm through intercourse.”

• “I’m more klutzy than sensuous in bed.”

• “My needs are too kinky.”

• “I make too much noise.”

• “I’m too quiet when we make love. I have trouble expressing myself.”

• “My pubic hair is ugly.”

• “I’m too fat/thin.”

• “My tush is too flat/soft/fat.”

• “I come too fast.”

• “I take forever to come.”

• “I can’t get you to climax.”

• “My vagina is too stretched out/too small.”

• “I’ve never had an orgasm.”

• “I don’t lubricate enough/I lubricate too much.”

• “I worry my vagina tastes bad.”

• “I don’t know how to please you.”

• “I can’t tell you how to please me in bed.”

• “I feel awkward showing passion.”

• “I’m afraid of letting go/losing control.”

• “I feel cheap when I give oral sex.”

• “I’m afraid I’ll choke on your penis if I put it in my mouth.”

• “I’m afraid you’ll come in my mouth.”

• “I think about making love with someone of my own sex.”

• “When I initiate sex I feel too forward.”

• “I like watching porn.”

• “I’d like us to use a vibrator at times.”

• “I masturbate when you’re not around.”

As you listen to your partner’s admissions, it’s important to realize that you’re being entrusted with deeply personal information. Treat it with the utmost sensitivity. If what your partner believes seems untrue to you, now is the time to say so. When one of my patients named Vera told her husband how much she hated the black hairs around her nipples—they made her feel unfeminine, she said—he joked, “The only hair I’ve ever worried about is the forest that’s growing out of my nose and ears. I won’t make fun of your imperfections if you don’t make fun of mine.”

When you confess your shame and your partner helps you reduce its sting or overcome it, you remove a major barrier to intimacy.

After you’ve revised your assumptions about sexual desire, arousal, and orgasms; ousted the affair-person from your bedroom; set realistic expectations about passion and the use of fantasy; and acknowledged your own personal intimacy issues, you still may be afraid to heal and love your partner again.

Fear of reinvesting in a damaged relationship, fear of opening yourself up and letting your partner love you again, fear of hope itself—these are common among partners who are struggling to reestablish intimate ties after an affair.

Equally daunting is the fear of change. When you realize how old and deep your dysfunctional patterns are, how integral to your sense of self, you may say, “I am who I am. It’s too late to become someone else.”

“You step off the curb and begin to walk across the street, not knowing what it’s going to be like when you get to the other side,” one hurt partner told me. “If I become more loving, more sexual, more direct about what I need, I’ll experience my husband differently, and myself, too. I’ll be a different person. I’ve always felt ignored, disappointed, deprived. If I give that up, who will I be?”

It’s natural to repeat what’s familiar and well-rehearsed, no matter how maladaptive. But you may be more capable of intimacy than you believe.

If you want to move closer, you can begin by identifying and taking responsibility for how you’ve kept your partner at a distance, how you’ve sabotaged your partner’s efforts to know you. You can go back before the affair, before the two of you met, and look for maladaptive patterns in the way you’ve related to significant others since childhood. And you can consciously coach yourself to experiment with new, more loving ways of interacting.

Try talking back to your fears. You have a small window of opportunity in which to remake yourself and your relationship. Don’t squander it, blindly adhering to arrested patterns of intimacy learned in childhood. Don’t waste your energy keeping your relationship cold. Ask yourself, “What am I waiting for? When will I feel more ready to love again? How many more chances will we have to rebuild our life together?” It’s going to take many corrective experiences to feel emotionally safe, to restore a level of trust where you can “put your deepest feelings and fears into the palm of your partner’s hand, knowing they will be handled with care.”21 But I encourage you to break the seal that keeps you apart, and begin the process.