First version completed on July 8, 1954. First published on April 18, 1959, in Lianhe Bao Fukan 聯合報副刊 (United Daily News: Supplement).

Like a hidden paradise on earth, the plain at Jianshan has hills on all four sides. On one side is the Taiwan Central Range; the other three sides are mere hillocks. Mostly they are covered in rocky soil on which nothing but wild grasses grows.

The Central Range extends in many peaks and ridges, the nearest of which are covered all over with teak forest, the pride of the Forestry Bureau. The teak forest is a tender, translucent green, reminiscent of a fresh watercolor. Further into the mountains the forest is painted a dark, even green. In the deepest parts of the range the high peaks are swathed in a mauve haze, like immortals wearing Taoists’ robes. The highest summits are wrapped in layer upon layer of mist and clouds, giving an appearance of solemnity, delicacy, and grace.

The sky is a pure wash of blue, like a bolt of indanthrene cotton before its first wash. The sun has risen to the mere height of a bamboo pole, with a white cloud flitting to and fro before it. In the far southeast another column of gray cloud is gathering.

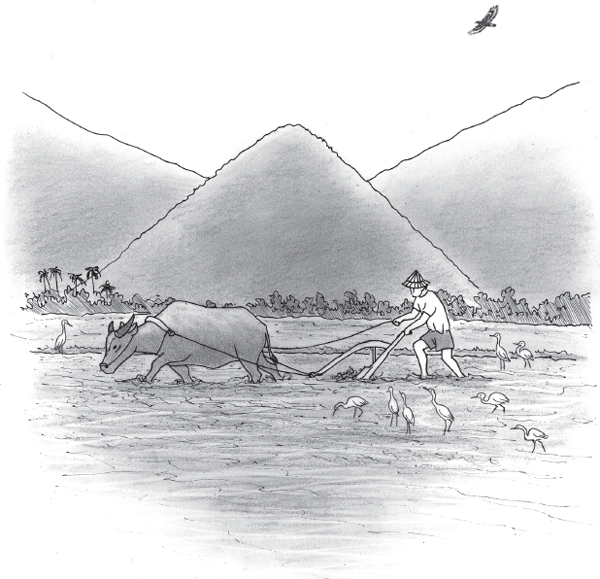

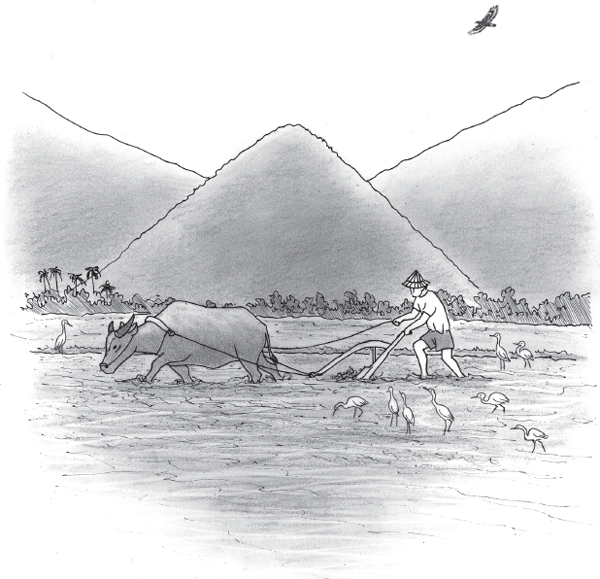

Sky, clouds, and hills lie quietly upside down in the brimming paddyfields. The plowman plows them up along with the clods and water. Together with rampant tendrils of sesban weed, they become entangled on the plowshare, like a scarf. Every two or three paces a great bundle of weeds, sky, clouds, and hills twines itself round the plow. It’s as if the whole field is draping itself over the plow: the ox stumbles, staggers, and comes to a halt.

The plow has run aground!

“Yah!” The plowman scolds, lifting his whip and flourishing it. “Yah! Dammit, I’ll beat you to death!”

Startled, the ox lunges forward with all its might, stretching the hitch-ropes as tight as steel cables, but it can’t budge an inch, as if it has taken root. Well, no wonder: those are the sky and the hills caught on the plow; how could the ox ever lift them?

Looking very hard done-to the plowman bends to clear the tangled mess that clogs the plow. And so the plow moves freely again, the ox pulls with renewed vigor, and the plowman’s in the mood for whistling once more.

When the plowing is done it’s the turn of the thirteen-toothed harrow to break the clods. Then they harness the “ironing plank” to “iron” the field flat. By this point the field looks like a gray woolen blanket spread out on the ground, smooth and even.

Now the rice seedlings can be planted out.

The planters bend their waists, backs to the clear blue sky, like so many insects. But these insects do not crawl forward; instead they inch backward.

1 The men’s dark-red backs are bare, giving off a dull, dark, steely sheen in the sunlight, like the carapaces of beetles. Luckily, the morning breeze comes blowing—sweeping away at the steadily growing summer heat.

The young women are repairing the banks and paths, or else cutting the weeds growing there and on the banks of the ditches. They wear colorfully patterned cotton smocks tied at the waist with multicolored cords. The tails of the blue squares of cloth folded and tied round their bamboo hats flutter in the breeze like sails. As they work, their hill songs and laughter adorn their youthful vivacity. Each of them is a fresh bloom, and these flowers are blossoming all over Jianshan’s little patch of pastoral heaven, embellishing it with fresh and lovely life.

High above the people’s heads, a crested serpent eagle spreads its mighty wings and traces circles as big as cartwheels, uttering short, high calls as it seeks what the land tries to conceal: perhaps a snake or a dead field mouse. At such a time there is no shortage: the raptor need only look on the banks, in the grass thickets, or on the little slopes. High in the sky it soars, searching, its small head alert as it focuses on the ground, now to the left, now to the right. Then suddenly it gathers itself and plummets with all the force of a thunderbolt. When it flies up again its claws are grasping something long and thin. It’s a snake, and the eagle flies off with it toward some cliff or forest corner.

From east to west, from south to north, the whole Jianshan plain is full of human shapes, bright laughter, hill songs, children’s squeals, birdsong, and the wordless murmuring of water. The rank smell of the earth, the sweet fragrance of grass and seedlings, the stench of sweat and sesban and dead creatures rotting in the field: mingled together, these smells float on the air. The sun climbs ever higher.

Everything is concentrated in a joyful, harmonious rhythm, rolling on toward a solemn common goal.

A member of one of the planting gangs starts to sing a Hengchun song:

Yearning; longing …

1. It is a well-known curiosity in Taiwan that when planting out seedlings, Hakka farm workers move backward instead of forward.