As the following chapter makes clear, history is not merely about leaders and politics but also the masses of people and their everyday lives. In the following pages, I tell about the ways Ottoman subjects earned livelihoods in the various sectors of the economy. This overview of the Ottoman economy is not a lesson in elementary economics, overflowing with statistics at micro- and macro-levels. Rather, it is designed to demonstrate how people in the Ottoman Empire made their livings and how these patterns changed over time. To achieve this goal, the chapter emphasizes a complex matrix that relates demographic information on population size, mobility, and location with changes in the significant sectors of the economy. After reviewing population changes, the chapter turns to the first sector, agriculture that, in 1700, was the dominant economic activity, as it was virtually everywhere else in the world. The chapter then turns to each of the other economic sectors in which people worked – manufacturing, trade, transport, and mining – in the rank order of importance just listed. As will become evident, although the economy remained basically agrarian, agriculture itself changed dramatically, becoming more diverse and more commercially oriented. In addition, Ottoman manufacturing struggled first with Asian, then with European competitors, yet obtained surprising levels of production. If these transformations did not lead to anything approaching an industrial revolution, they nonetheless did sustain improving levels of living until the end of the empire.

The Ottoman state, before the late nineteenth century, counted the wealth of its subjects but not the people themselves. When examining its human resources, it enumerated only those responsible for the payment of taxes (household heads, usually males) or likely to be of military use (young men). Therefore, population size for a given area or the empire as a whole can only be approximated until the 1880s, when the first real censuses appear. But, while the actual numbers of people cannot be known, the general patterns of demographic change can be seen, and so let us begin with these.

In the early eighteenth century, about all that can be said with certainty is that the aggregate Ottoman population was smaller than it had been towards the end of the sixteenth century. It seems quite likely that the overall population declined in the seventeenth century, part of a general Mediterranean population trough. Moreover, as seen, the empire was declining in global demographic importance (chapter 5). Further, by 1800, the populations of the Anatolian and Balkan provinces were about the same whereas, in the seventeenth century, that of the Balkan provinces had been greater. And finally, it seems safe to say that, in the eighteenth century, the population of the Arab lands was declining, with very sharp drops after c. 1775. In the nineteenth century, by contrast, the population of all three regions – the Balkans, Anatolia, and the Arab lands – increased.

A few numbers here might be useful: the total population may have equaled some 25–32 millions in 1800. According to one estimate, there were 10–11 millions in the European provinces, 11 millions in the Asiatic areas, and another 3 millions in the North African provinces. Another estimate indicates the Balkan regions accounted for one half or more of a total 30 millions during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In 1914, more certainly, Ottoman subjects totaled some 26 millions. To understand these figures, we need to consider that the territorial size of the empire had been much reduced – from a total area of 777,000 to 337,000 square miles (3.0 to 1.3 million square kilometers). Thus, while population totals in 1800 and 1914 were about the same, the densities approximately had doubled since the same number of inhabitants were squeezed into less than half the area they had occupied. Further, the demographic center of the empire remained in Europe, until quite near the very end. Population densities in Rumeli (the Balkans) were double those in Anatolia, while these latter were triple the densities in Iraq and Syria and five times those in the Arabian peninsula. To realize the demographic importance of the Balkan provinces, consider the following figures. In the 1850s, Rumeli held about one-half the total Ottoman population while, in 1906, the tiny Balkan fragments remaining in Ottoman hands still accounted for a full one-quarter of the total Ottoman population. Demographically, the Balkan provinces were crucial and their loss was a terrible economic blow for the Ottoman economy and state.

Ottoman subjects did not live very long: Muslims in Anatolia in the final decades of the empire averaged, from birth, a lifespan of twenty-seven to thirty-two years. If they managed to survive until the age of five, then forty-nine years was the norm. Similarly, inhabitants of early nineteenth-century Serbia lived an average of twenty-five years from birth.

In Istanbul, Anatolia (and perhaps the Balkans), Ottoman subjects did not live in multiple households of three generations of family – grandparents, parents, and children. Rather, they dwelt in simple or nuclear families, that is, with parents and children together and only rarely, the grandparents. Rural households in Anatolia were five to six persons in size. Households in three cities in the Danubian areas of the Balkans averaged 4.5 persons (in 1866). Istanbul households, at the end of the nineteenth century, averaged about four persons, probably the smallest in the empire. But (equally), fragmentary evidence suggests different patterns in the Arab provinces. Households in Aleppo and Tripoli (in Lebanon) were much larger than the urban figures just seen and held 7.5 and 5.5 persons (in c. 1908). And, at Damascus, one of the larger cities of the empire, residential patterns differed greatly from those in Istanbul. Four-fifths of Damascene households contained at least two generations and one-third of these held more than three generations! At the end of the nineteenth century, houses in Damascus often were quite large and more than one-half of these residences contained more than one family. Indeed, the Damascus multiple-family household averaged nearly three persons more than Istanbul households. The differences between the two likely derive from several factors. Notably, in Istanbul and Ottoman Anatolia, households generally divided on the death of the father while many Damascene households containing siblings continued after the parents’ deaths. There were other factors. Polygyny rates were much higher at Damascus although, overall, polygyny among Muslims was not nearly as common as stereotypes would suggest. In the small Arab town of Nablus, 16 percent of the men maintained polygynous relationships while 12 percent of the Muslim men in Damascus did but only 2 percent in Istanbul. Overall, it may be the case that households in Anatolia, Istanbul (and perhaps the Balkans) were smaller and less complex than those in the Arab provinces.

As an example from Aleppo (and likely elsewhere) suggests, there was no visible difference in the structure of households among Muslims, Jews, and Christians, except for the fact that the latter two legally practiced neither concubinage nor polygyny. Divorce was permitted and not uncommon among Ottoman Muslims (and likely the other communities). Because of the need to maintain political ties and property, upper-class Muslim men and women divorced less frequently than did their counterparts lower down in the political and economic order.

A host of factors affected mortality rates, positively and negatively. Knowledge of birth control was widespread but its actual extent remains uncertain. The state passed laws against it in the later nineteenth century but this may have reflected growing official concerns as much as increasing usage. In Aleppo during the eighteenth century, abortion as a form of birth control was practiced but apparently not very frequently. To postpone pregnancies, extended nursing, lactation, commonly was employed while delayed marriage was frequent in late nineteenth-century Istanbul and likely other locations as well. Better sanitation and hygiene played a positive role in extending longevity thanks, in part, to a more activist state that, for example, established quarantine stations and hospitals during the later nineteenth century. Epidemic diseases were grave afflictions. Plague remained a major event in Ottoman society until the second quarter of the nineteenth century. In the capital, for example, plague struck repeatedly during the later 1820s, undermining resistance to Russian invaders not far from the city. In 1785, one-sixth of the population of Egypt died from plague. From the standpoint of disease, the clusters of people concentrated in cities were loci of infection that regularly were devastated. In most areas, urban dwellers formed perhaps 10–20 percent of the total population while, in Ottoman Macedonia, the proportion was an unusually high 25 percent. Plague-devastated cities were refilled by immigration from the countryside. Izmir, because it was a great port city in constant contact with the wider world, perhaps suffered more than average, with plagues recurring in more than half the years of the eighteenth century. Salonica, another port city, endured major eruptions of plague during twelve years of that same century. But how are we to understand a report that, in 1781, plague killed some 25,000 persons there? Such figures surely are incorrect since these represent 50 percent of the population of Salonica at the time. Instead of 25,000 dead, we should understand the report as saying simply that a lot of people died. More accurate death rates exist for the city of Aleppo because a European physician lived in the city during the later eighteenth century and personally counted and recorded plague deaths. Aleppo, an important center on the caravan routes, suffered eight major eruptions of plague, that lasted for fifteen years in the eighteenth century, and four more between 1802 and 1827. According to this physician’s figures, deaths from plague, also called the black death, equaled 15–20 percent of the population of Aleppo in the late 1700s. Cities remained dangerous places not merely because of disease. Fire routinely ravaged entire neighborhoods because, in many regions of the empire, wooden houses prevailed. For example, in the capital city during the mid 1820s, a series of fires occurring in just over a week destroyed 21,000 homes!

Famines also took a severe toll. Famines often do not derive merely from natural causes such as bad weather and voracious insects. Quite often, perhaps most of the time, man-made factors that interfere with the distribution of food – including politics, bad transportation, and war – cause famine. Egypt suffered six famines between 1687 and 1731. But, thanks to improvements in transport and communication, they declined in frequency everywhere in the empire during the nineteenth century. Famine faded from many Balkan provinces in the 1830s while the last killing famine in Anatolia occurred four decades later, during the mid 1870s. Thereafter, crop failures in an area usually were offset by shipments of food from outside, thanks to steamships, railroads, and telegraph lines. During wars and other political crises, however, famine re-emerged as supply systems sagged and collapsed. Wars were terrible killers of Ottomans and vast numbers died on the battlefield and away from it as well, of wounds and disease. In this way, wars helped to reduce the male proportion of the population and upset the demographic balance between males and females. Wars, however, killed not only the fathers of the next generation but also its mothers, and vast numbers of noncombatant grandparents and children. Death came with the bullets and also malnutrition and its accompanying diseases. Wars appeared all too frequently in Ottoman history. These terrible killers raged in a full 55 percent of all the years of the eighteenth century and in 45 percent of all the years between 1800 and 1918. And finally, emigration also reduced the overall population. Over one million Ottoman subjects emigrated to the New World between c. 1860 and 1914. The vast majority, 80–85 percent, were Christians and many of these left after 1909, when conscription of Ottoman Christians was enacted. Moreover, the evidence suggests that since more males than females emigrated, the sex ratio of those remaining tilted still more heavily in favor of females.

During the nineteenth century, some clustering of population occurred in coastal areas, thanks to the rise of port cities to serve the growing international trade of the empire. Demographically, port cities grew far faster than the overall population. Most of them were deep-water harbors and closely linked to their hinterlands, at first by caravans and later by railroads. Three examples of port city population growth will suffice – one each from the Balkan, Anatolian, and Arab provinces. In the area of modern-day Greece, the port of Salonica rose from 55,000 persons in 1800 to 160,000 in 1912. On the western Aegean coast of Anatolia, the superlative port of Izmir held c. 100,000 inhabitants in 1800 (double the number of the late sixteenth century) and some 300,000 in 1914. Beirut, in modern Lebanon, grew from a small town of 10,000 in 1800 to a staggering 150,000 in 1914.

By contrast, the population of inland towns and cities often stagnated or declined. Sometimes the causes were political, such as in Belgrade where the population fell by two-thirds, from 25,000 to 8,000, during the civil strife of the early nineteenth century that accompanied the rise of the Serbian state. The number of Diyarbekir dwellers declined from 54,000 to 31,000 between 1830 and 1912 as its trade routes dwindled in importance. Ankara, also in the Anatolian interior, had been an important manufacturing center of mohair wool, cloth, and yarn. During the early nineteenth century, however, its monopoly faded and these activities disappeared because of international competition. But then Ankara became a railhead, the terminus of the Anatolian Railway from Istanbul, and its fortunes revived. And so, its population in 1914 was about the same as a century before, although it surely had dipped sharply during the years in between. Thus bare population statistics mask different stories of rising or falling populations of particular places.

Migrations affected population distribution throughout Ottoman history. These movements of peoples occurred for a host of reasons, economic as well as political. Among migrations for economic opportunity can be counted those to coastal Izmir by Ottoman subjects from interior regions and from the nearby islands in the Aegean Sea. There, and at Beirut, Alexandria, and Salonica, the new arrivals joined migrants from across the Mediterranean world – Malta, Greece, Italy, and France. Thanks to them, the port cities developed a cosmopolitan, multi-lingual “Levantine” culture, more a part of the general Mediterranean world as a whole than the Ottoman Empire in particular. Generally, economic migration to urban centers was a normal and important feature of Ottoman life. Workers often traveled vast distances to work in cities and, after several or more years, returned home, as did, for example, the masons and other construction workers who built the great imperial mosques of Istanbul during the sixteenth and later centuries. Also, to build railroads in the Balkan, Anatolian, and Arab provinces during the later nineteenth century, workers by the thousands came from afar as well as from nearby areas. And, in patterns that date back centuries and continued until the end of the empire, men trudged on foot for months from humble villages in eastern Anatolia to work as porters and stevedores in far away Istanbul, there setting up communal bachelor quarters. Others came from central and north Anatolian towns to serve as the capital’s tailors or laundrymen. Like the porters, these remained for several years and were replaced by others from the same village. In the nineteenth century, ethnic Croats and Montenegrins traveled from their northwest Balkan homes to the coalmines at Zonguldak on the Black Sea, bringing along their long traditions of mining skills, and often settling permanently in the region.

In common with economically driven migrations, those for political reasons often were dramatic and still affect the area today. Take, for example, the demographic impact of the Habsburg–Ottoman wars, dating from the late seventeenth century and continuing into the eighteenth century. To escape the fighting, Orthodox Serbs migrated from their homes around Kossovo (southern modern-day Yugoslavia) in an intermittent stream northward. Until then, the Kossovo area had been heavily Serb but after they left, Albanians gradually migrated in, filling the empty spaces. Some Serbs moved into eastern Bosnia, where, consequently, a Muslim majority gave way to an important Christian presence. Other Serbs continued north and crossed over into the Habsburg lands, for example, after the Ottoman victories in the 1736–1739 war. Here, then, is the Ottoman background to the Bosnian and Kossovo crises of the 1990s.

Many of the other politically compelled migrations elsewhere in the Ottoman world were different in their origins and vastly greater in magnitude. These were triggered by two sets of events. In the first, Czarist Russia conquered Muslim states around the northern and eastern Black Sea littoral; the Crimean khanate was among them but there were many others. In the second, the Russian and Habsburg states annexed Ottoman territories or promoted the formation of independent states in the western Black Sea littoral and in the Balkan peninsula overall. As these processes unfolded, some Muslim residents fled, not wishing to live under the domination of new masters. Many more, however, suffered forcible expulsion by the Czars and the governments of the newly independent states. For both, the Muslims were enemies, undesirable “others,” to be removed by whatever means necessary. As a result, Muslim refugees began flooding into the Ottoman world in huge numbers, beginning in the late eighteenth century. Between 1783 and 1913, an estimated 5–7 million refugees, at least 3.8 million of whom were Russian subjects, poured into the shrinking Ottoman state. For example, between 1770 and 1784, some 200,000 Crimean Tatars fled to the Dobruja, the delta of the Danube. Still more fled during the period around World War I; in 1921, for example, up to 100,000 refugees overwhelmed Istanbul, most of them from Russia. Many refugees fled once, then again, settling elsewhere in the Ottoman Balkans, only to leave again when that area became independent. Another example: some 2 million people left the Caucasus region, for destinations in the Ottoman Balkans (some 12,000 at Sofia alone), Anatolia, and Syria. The refugees either went voluntarily or by government design, for example, to populate the frontiers or the empty lands along the new railroads. In 1878 alone, at least 25,000 Circassians arrived in south Syria and another 20,000 came to the areas around Aleppo. In Anatolia, the government settled refugees, often with incentives, to people the areas along the developing Anatolian railroad. These refugees endured enormous sufferings: perhaps one-fifth of the Caucasian migrants died on the journey of malnutrition and disease. Between 1860 and 1865, some 53,000 died at Trabzon on the Black Sea, a major point of entry.

These migrations have left a profound mark, not the least of which are the bitter memories of expulsion that still can inflame relations between modern-day countries like Turkey and Bulgaria. Today, the descendants of refugees occupy important leadership positions in the economies and political structures of countries such as Jordan, Turkey, and Syria. The migrations acted like a centrifuge in southern Russia and the Balkans, reducing previously more diverse populations to a simpler one, and depriving the original economies of skilled artisans, merchants, manufacturers, and agriculturalists. The societies of the host regions, for their parts, became ethnically more complex and diverse while both the originating and host societies became religiously more homogeneous. Thus, the Balkans became more heavily Christian than before (although Muslims remained in some areas) while the Anatolian and Arab areas became more Muslim. Subsequently, following the expulsion and murder of Ottoman Armenians and Greeks during and after World War I, the population of Anatolia became more homogeneous in religion.

Over the 1700–1922 period, some urbanization occurred, and the proportion of the total populace living in towns and cities increased. There is fragmentary evidence of an earlier increase in urban populations during the seventeenth century and perhaps part of the next century, partly because of the flight to towns and cities that were safer than the countryside in politically insecure times. Also, as seen above, port cities grew sharply in the eighteenth century but especially during the nineteenth century. Further, ongoing improvements in hygiene and sanitation generally made cities healthier and more attractive places to live during the nineteenth century.

The population also became more sedentary and less nomadic between 1700 and 1922. During the eighteenth century, nomads dominated the economic and political life of some regions in central and east Anatolia and in the Syrian, Iraqi, and Arabian penninsula areas as well. On several occasions, nomads pillaged the pilgrimage caravans on their way from Damascus to Mecca and, generally, dominated the steppe zones of central and east Syria and points east and south. During the nineteenth century, the state successfully broke the power of many tribes. For example, it forcibly settled tribes in southeast Anatolia where vast numbers of them died in the malarial heat of their new homes. Elsewhere, too, it sedentarized tribes, forcing them into agricultural lives and reducing or altogether eliminating their ability to move about at will. Moreover, when the state settled the immigrant refugees, it often used them to create buffer zones of population between the older areas of agrarian settlement and the nomads, forcing these deeper into the desert. There is no doubt that the nomads’ numerical importance fell sharply after 1800 (see also under “Agriculture” below). But, it is also true that tribes in some areas, including the Transjordanian frontier, eastern Anatolia and the region of modern-day Iraq continued to exercise considerable autonomy.

A comparison of transportation methods during the more distant and recent pasts powerfully evokes the incredible changes that have taken place in the modern era. Until the development of the steam engine in the later eighteenth century, transport by water was the only realistic form of shipping goods in bulk. Sea transport by oared galleys in the Mediterranean world had given way to sailing vessels as the eighteenth century opened. Shipment via sailing vessels was vastly cheaper and almost always faster than land transport. Shipment by land had been prohibitively expensive because – except for the shortest distances – the fodder the animals consumed cost more than the goods they carried. Even the smallest ships of the early modern period carried 200 times more weight than the most efficient forms of land transport. But, unlike that by land, sea transport was wildly unpredictable because of changing weather, currents, and winds. Once embarked on a sea journey, there was no way to predict the day or even the week of arrival, never mind the hour. Under the sailing technologies that prevailed in the eighteenth century, the 900-mile journey between Istanbul and Venice, one of the main trade arteries, could take as short a time as fifteen days with favorable winds. But, in adverse conditions, that same journey lasted eighty-one days. Similarly, the 1,100-mile Alexandria–Venice voyage could go quickly, seventeen days, but it also could last eighty-nine days, five times as long. Thus in the pre-modern period, great uncertainty prevailed about shipping dates and arrival times. Moreover, sailing vessels were very small, tiny by modern standards. The typical merchant ship of the day was 50–100 tons, staffed by a half dozen crew members.

During the nineteenth century, water transport underwent a radical transformation thanks to the emplacement of steam engines that pushed ships through currents, tides, and winds. Predictability increased to the point that timetables appeared, noting exactly the scheduled departure and arrival of ships. Steamships first appeared in the Ottoman Middle East during the 1820s, not long after their development in Western Europe. Steam also brought about a vast increase in the size of the ships. By the 1870s, steamships in Ottoman waters reached 1,000 tons, some ten to twenty times larger than the average size of ships in the sailing era. (By modern standards, however, these were tiny: the Titanic was 66,000 tons while the Queen Mary 2 displaces 76,000 tons.)

This sea-borne transportation revolution, however, did not take place overnight. During the 1860s, sailing vessels remained commonplace and four times as many sailing as steam vessels called on the port of Istanbul. But, by 1900, the transformation was complete: sails accounted for only 5 percent of the ships visiting the capital city. Nonetheless, astonishingly, this 5 percent represented more sailing vessels than had visited Istanbul in any preceding year during the nineteenth century, a measure of the extraordinary increase in shipping taking place.

Steamships also revolutionized river transport. Until their appearance, river voyages typically were one way, down river only, with the current. The Nile was the great exception: there the current flows south to north while the prevailing winds are north to south, thus making sailing ship transport both down and upriver routinely possible. This situation, however, is very rare in Middle Eastern waters. Normally, vessels floated down river with their goods; on arrival, the ships were broken up and the timber sold since moving upriver against the current was next to impossible. And so, transport on the great rivers of the Balkan provinces, such as the Danube, or on smaller ones, such as the Maritza river through Edirne, was uni-directional from the interior to the Black Sea. In the Arab provinces, similarly, goods only flowed down the Tigris on the 215-mile trip from Diyarbekir to Mosul and Baghdad. This particular journey, despite the inefficiency of one-way transport, cost one-half as much as the cheapest land transportation. With steam power, ships traveled both up as well as down rivers, enormously impacting the interior regions of the Danubian and Tigris–Euphrates basins.

Steamships both resulted from and promoted the vast rise of commerce during the nineteenth century (see below). This increase could not have occurred but for the technological revolution in transportation which in turn facilitated still greater upward movements in the volume of commerce. The additional effects were equally important. For example, Western economic penetration of the empire intensified: Europeans owned almost all – 90 percent of the total tonnage – of the commercial ships operating in Ottoman waters in 1914. These ships also accelerated the growth of port cities with harbors deep and broad enough to accommodate the ever-larger ships. Also, the steamships’ regularity and dramatically lower costs made possible the vast emigrations to the New World from the Ottoman Empire (and west, central, and eastern Europe as well).

Steamships also prompted construction of the Suez Canal in 1869, an event that helped bring about the European occupation of Egypt (see map 5 p. 60). Further, the all-water route of the canal drastically reduced shipping times and costs. The Iraqi lands thus prospered as the canal made it possible for their produce to be routed through the canal to European consumers. But other Ottoman towns and cities suffered grave losses as the canal diverted overland trade routes. Damascus, Aleppo, Mosul, even Beirut and Istanbul, all lost business because of the diversion of the trade of Iraq, Arabia, and Iran to the canal.

The changes in land transport equaled in drama and scope those of the sea-borne revolution. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, animate transport, human and animal – horse, camel, donkey, mule, and oxen – totally monopolized the shipment of goods over land. The use of human power quite likely was restricted to local, quite short, shipments of goods within villages. Land transport was so laborious, slow, and irregular that journeys were measured not in miles or kilometers but in the time that they would take, depending on the season and the terrain. Take, for example, an 1875 guide book that described trips foreign visitors might take in Ottoman Anatolia, an early indication of the emerging tourist industry. The trip for a horse-mounted traveler from Trabzon to Erzurum −180 miles distance – was fifty-eight hours long, to be done in eight stages, each stage ranging from four to ten hours.

In terms of transport, the Ottoman world generally divided into two parts – the wheeled zone of the European provinces and the unwheeled world of the Anatolian and Arab provinces. This division more or less coincided with another: horses dominated the Balkan transport routes while camels tended to prevail in the Arab and Anatolian lands. To this general rule, there were exceptions. Ottoman armies had used massive numbers of camels to transport goods up the Danubian basin while horses, mules, and donkeys dominated the important Tabriz–Trabzon trade routes. But the general rule nonetheless held. In the early nineteenth century, the Salonica–Vienna journey took fifty days and involved horse caravans of 20,000 animals. In the 1860s, long caravans of carts trekked from the Bulgarian hill town of Koprivshtitsa on a one-month journey bringing manufactured goods to Istanbul for resale in the Arab lands. But east of the waterways separating the European from the Asian provinces, camels generally prevailed. Superior to all other beasts of burden, the camel could carry a quarter-ton of goods for at least 25 kilometers daily, 20 percent more weight than horses and mules and three times more than donkeys. Mules, donkeys, and horses, however, often were preferred for shorter trips and on the great Tabriz–Erzurum–Trabzon caravan route because of their greater speed. This famed trail annually used 45,000 animals, three caravans per year, each with 15,000 animals carrying a total of 25,000 tons. But nearly everywhere else in the Asian provinces, long strings of camels were the more familiar sight. In the early nineteenth century, 5,000 camels worked the twenty-eight-day Baghdad–Aleppo route while the Alexandretta–Diyarbekir journey of 250 miles required sixteen days. The Aleppo–Istanbul caravan route stretched 500 miles and forty days, and four great caravans annually made the trip during the eighteenth century. Because their carrying capacity comparatively was limited, caravans almost always carried high-cost, low-bulk goods such as textiles and other manufactured goods, as well as relatively expensive raw materials such as spices. Caravan shipments of foodstuffs, on the other hand, were rare because the transport costs usually exceeded their selling price. For example, caravan shipment of grain from Ankara to Istanbul (216 miles) would have raised its price 3.5 times and that from Erzurum to Trabzon (188 miles) three times. These pre-railroad realities meant that fertile lands not near cheap sea transport supported the needs of the local population and the rest was left fallow or for animal raising.

There were several minor changes in the existing, animal-based, land-transport technologies during the nineteenth century. First, in a relatively significant way, wheeled vehicles were re-introduced into the Anatolian and Arab provinces (they largely had disappeared during the fall of the Roman Empire) by Circassian refugees and by European Jewish settlers in Palestine. Also, as commerce increased, there was some improvement of a few so-called metaled roads. Across the width of these roads, strips of metal were laid to reduce the mud. One such highway between Baghdad and Aleppo was built in 1910 and cut the travel time from twenty-eight days to twenty-two days.

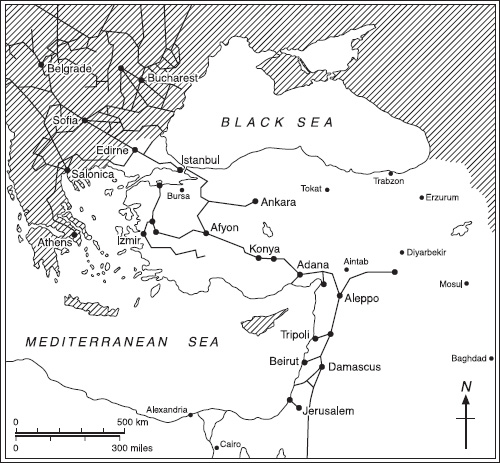

Railroads – steamships on land – revolutionized land transport in a profound way. Based on a principle of hauling large numbers of cars – each of which carried as much grain as at least 125 camels – on a low friction track, railroads offered incredibly cheap and more regular transport, especially for bulk goods such as cereal grains. For the very first time in history, the potential of fertile interior regions – such as central Anatolia or the Hawran valley in Syria – could be realized. When railroads were built into such areas, market agriculture immediately developed because the products could be sold at competitive prices. Within just a few years, cultivators in newly opened regions were growing and the railroads were shipping hundreds of thousands of tons of cereals. Overall, by volume, cereals formed the overwhelming majority of goods shipped by rail (map 7).

For a number of reasons, including very low population densities and the lack of capital, the Ottoman lands contained a relatively small railroad network. (In Egypt, by contrast, dense populations concentrated in a narrow strip of rich soils prompted the appearance of a very thick system of trunk and feeder lines by 1905.) The first Anatolian lines were built in the 1860s. But the biggest development by far occurred in the more heavily settled European provinces that, in 1875, contained 731 miles of track. With just a few exceptions, foreign capital built the lines that accelerated economic development, thus increasing foreign financial control. German capital, for example, financed the Anatolian railway and brought a boom to inner Anatolia. In 1911, Ottoman railroads overall transported 16 million passengers and 2.6 million tons of freight on some 4,030 miles of track. Lines in the Balkans contained 1,054 miles of track and carried 8 million passengers while those in Anatolia held 1,488 miles with 7 million passengers. By contrast, the 1,488 miles of track in the Arab provinces carried only 0.9 millions, a reflection of the scant population (plates 3–4).

Map 7 Railroads in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1914, and its former European possessions

Adapted from Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994), 805.

Plate 3 Bond certificate of the “Anatolian Railway Company,” second series, 1893

Personal collection of author.

Plate 4 Third class coach on the Berlin–Baghdad railway, 1908. Stereo-Travel Company, 1908

Personal collection of author.

Railroads created a brand new source of employment and, by 1911, more than 13,000 persons worked on Ottoman railroads. Also noteworthy are the new social horizons opened up both by railroad employ and travel. The 16 million passenger trips physically brought many Ottoman subjects to places they had never been before, promoting more communication than ever between and among regions and forever changing rural–urban relations. Dangerous trips that once had taken months on foot now took place in safety, over just a few days.

Railroads affected earlier forms of land transport in ways that are sometimes surprising. Relatively dense networks of feeder railroads – smaller lines leading to a larger main line – emerged in the hinterlands of port cities such as Beirut and Izmir and to a lesser extent in the Balkan provinces. But these were an exception. More generally, the Ottoman railroads evolved as a trunk system – for example, the Istanbul – Ankara and Istanbul–Konya and Konya–Baghdad railroads – characterized by main lines with few rail links feeding into them. In the absence of rail feeders, animal transport was needed to bring goods to the main lines. As the volume of crops grown for export in the railroad areas boomed, the number of animals bringing the goods to the trunk lines increased enormously. In the Aegean area, some 10,000 camels worked to supply the two local railroads. At the Ankara station, terminus of the line from Istanbul, a thousand camels at a time waited to unload the goods they had brought. Hence, even though caravan operators on routes parallel to the railroads soon went out of business, those servicing the main lines found new work. Thus, like the sailing vessels in Istanbul, traditional forms of land transport were invigorated at least temporarily by the vast increases in commerce prompted by steam engine technologies.

Commerce in the Ottoman system took many forms but generally can be divided into international and domestic – that is, trade between the Ottoman and other economies and that within the borders of the empire. Throughout the 1700–1922 period, international trade was more visible but less important than domestic trade, both in volume and value.

World wide during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, international trade increased enormously but less so in the Ottoman lands. Whereas, for example, international commerce globally grew sixty-four times during the nineteenth century, it increased a comparatively meager ten- to sixteen-fold in the Ottoman Empire. Thus, it is not surprising to learn that while, in 1600, the Ottoman market was a crucial one for the West Europeans, this no longer was true in 1900. The global commercial importance of the Ottoman empire had declined. The Ottoman economy was not shrinking – to the contrary – but it was declining in relative significance. It is also true that it remained among the most important trade partners of the leading economic powers, such as Britain, France, and Germany.

As the preceding section indicated, transportation improvements in steamships and railroads played a major role in the development of Ottoman commerce after their introduction in the early and middle parts of the nineteenth century. Railroad lines, extensive port facilities and harbors were constructed because international demand already was present for the products they would ship, while the new facilities themselves further stimulated the trade.

Let me begin this section by discussing two of the more important additional factors affecting both domestic and international commerce, namely wars and government policies. Wars disrupted commerce not only during the times of fighting, when it was dangerous to move goods across borders and sometimes within the empire. Even worse, they brought territorial losses that ripped and tore apart the fabric of Ottoman economic unity, weakening and often destroying marketing relationships and patterns that had endured for many centuries. Here are two examples. First, when Russia conquered the northern Black Sea shores, it wrecked an important trading network for Ottoman producers. That is, it annexed a major market area in which Ottoman textile producers from Anatolia long had been selling their goods. Thereafter, the new imperial frontiers between Russia and the Ottoman Empire impeded or choked off altogether the longstanding flow of goods and peoples between two areas that had been part of one economic zone but now were divided between two empires. The other example is the fate of Aleppo following World War I, the conflict that ended the Ottoman Empire and, among other things, gave birth to the Turkish republic and a French-occupied state of Syria. Aleppo had been a major producer of textiles, shipping these mainly to Anatolia, that is, from one point to another within a single Ottoman imperial system. With the disappearance of the Ottoman Empire, the producers were in one country – Syria – while the customers were in another – Turkey. Seeking to remold its new Syrian colony into an economic appendage, France prevented the textiles from being shipped and thus triggered a collapse in Aleppo textile production. Thus, the Russian and Aleppo examples show the disastrous effects of border shifts on economic activity.

The role of government policy on commerce and the economy in general is hotly debated. Some argue that policy can have a major impact, a position supported by the example of French actions regarding Aleppo textiles. Others assert that policy merely formalizes changes already taking place in the economy. The capitulations, for example, are said to have played a vital important role in Ottoman social, economic, and political history. But did they? Without them, is it possible to imagine that the Ottomans would have maintained political and economic parity with western Europe? Or, consider the coincidence of massive state interference and economic recession during the late eighteenth century – which is the chicken and which the egg (see chapter 3)? Subsequent nineteenth-century state actions in favor of free trade include the 1826 destruction of the Janissary protectors of monopoly and restriction, the 1838 Anglo-Turkish Convention, and the two imperial reform decrees of 1839 and 1856. As a result, most policy-promoted barriers to Ottoman international and internal commerce disappeared or were reduced sharply. But, whether or not these decisions played a key role in Ottoman commercial and, more generally, economic development, remains an open question.

The importance of international trade is easy to overstate because it is so well documented, easily measured and endlessly discussed in readily accessible western-language sources. The overall patterns in international commerce seem clear enough. During the eighteenth century, international trade became more important, especially after c. 1750. From improved but still low levels, it then sharply rose in importance during the early nineteenth century, following the end of the Napoleonic wars. The balance of trade – the relation of exports to imports – often fluctuated in the short run but overall moved against the Ottomans. The aggregate value and nature of the goods being traded certainly changed a great deal. Trade was really quite limited during the early eighteenth century. The Ottoman economy re-exported high-value luxury goods, mainly silks from lands further east, and exported a host of its own goods, such as Angora wool cloth and, later on, cotton yarn. In exchange, imports such as luxury goods arrived. As the eighteenth century wore on, however, Ottoman exports shifted over to unprocessed goods including raw cotton as well as cereals, tobacco, wool, and hides. At same time, Ottomans increasingly imported commodities from the colonies of western Europe in the New World and East Asia. These “colonial goods” – sugar, dyestuffs, and coffee, produced by slave labor and thus lower in price – undercut the sugar from the Mediterranean, the coffee from Arabia (mocha) and the dyestuffs from India. Ottoman consumers also imported quantities of textiles, mainly from India and to a secondary degree from Europe. According to some scholars, a favorable balance of trade still existed at the end of the eighteenth century.

Although, as seen, the volume of international trade rose ten- to sixteen-fold between 1840 and 1914, the pattern of exports in agricultural commodities resembled that of the eighteenth century. Ottomans generally exported a mixed group of foodstuffs and raw materials including wheat, barley, cotton, tobacco, and opium. After 1850, however, some manufactured goods exports appeared, notably carpets and raw silk. In a way, these export manufactures replaced those of mohair cloth and luxury silks that had been important in the eighteenth century and before. While the basket of exported agricultural goods remained relatively fixed, the relative importance of the particular goods in the basket changed considerably over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By way of example, take cotton exports: these boomed and collapsed during the eighteenth century, boomed during the American Civil War, subsequently collapsed again and then soared in the early twentieth century. Regarding the basket of imports: colonial goods remained high on the list while those of finished goods – notably textiles, hardware, and glass – became far more important than during the eighteenth century.

Domestic trade, although not well documented, in fact vastly exceeded international trade in terms of volume and value throughout the entire 1700–1922 period. The flow of goods within and between regions was quite valuable but direct measurements are available only rarely. Consider the following scattered facts as suggestive of the importance of Ottoman domestic trade. First, the French Ambassador in 1759 stated that total textile imports into the Ottoman Empire would clothe not more than 800,000 persons per year, at a time when the overall population exceeded 20 millions. Second, in 1914, not more than 25 percent of total agricultural output was being exported, meaning that domestic trade accounted for the remaining 75 percent. Third, during the early 1860s, the trade in Ottoman-made goods within the province of Damascus surpassed by five times the value of all foreign-made goods sold there. Fourth and finally, among the rare data on internal trade are statistics from the 1890s concerning the domestic commerce of three Ottoman cities – Diyarbekir, Mosul, and Harput. None of these three ranked as a leading economic center. And yet, during the 1890s, the sum value of their interregional trade (1 million pounds sterling) equaled about 5 percent of the total Ottoman international export trade at the time. This is an impressively high figure when we consider their minor economic status. What would the total figure be if the internal trade of the rest of Ottoman cities and towns and villages were known? The domestic trade of any single commercial center such as Istanbul, Edirne, Salonica, Beirut, Damascus, and Aleppo was far greater than these three combined. Consider, too, that the domestic trade of literally dozens of medium-size towns also remains uncounted; similarly unknown is the domestic commerce of thousands of villages and smaller towns. In sum, domestic trade overwhelmingly outweighed the international.

The increasing international trade powerfully impacted the composition of the Ottoman merchant community. Ottoman Muslims as a major merchant group had faded in importance during the eighteenth century when foreigners and Ottoman non-Muslims became dominant in the mounting foreign trade. At first, the international trade was nearly exclusively in the hands of the west Europeans who brought the goods. By the eighteenth century, these merchants had found partners and helped growing numbers of non-Muslim merchants to obtain certificates (berats) granting them the capitulatory privileges which foreign merchants had, namely lower taxes and thus lower costs. In 1793, some 1,500 certificates were issued to non-Muslims in Aleppo alone. Although foreigners still controlled the international trade of the empire in 1800, their non-Muslim Ottoman protégés replaced them over the course of the nineteenth century. The best illustration of the new prominence of the non-Muslim Ottoman merchant class might be an early twentieth-century list of 1,000 registered merchants in Istanbul. Only 3 percent of these merchants were French, British, or German, although their home countries controlled more than one-half of Ottoman foreign trade. Most of the rest were non-Muslims. Nonetheless, Muslim merchants still dominated the trade of interior towns and often between the interior and the port cities on the coast. That is, for all the changes in the international merchant community, it seems that Ottoman Muslims controlled most of the domestic trade, plus much of the commerce in international goods once these had passed into the Ottoman economy from abroad.

Throughout its entire history, the Ottoman Empire remained overwhelmingly an agrarian economy that was labor scarce, land rich, and capital poor. The bulk of the population, usually 80–90 percent, lived on and drew sustenance from the land, almost always in family holdings rather than large estates. Agriculture generated most of the wealth in the economy, although the absence of statistical data prevents meaningful measurements until nearly the twentieth century. One indicator of this sector’s overall economic importance is the significance of agriculturally derived revenues to the Ottoman state. In the mid-nineteenth century, two taxes on agriculture – the tithe and the land tax – alone contributed about 40 percent of all taxes collected in the empire. Agriculture indirectly contributed to the imperial treasury in many other ways – for example, customs revenues on exports that, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, were mainly agricultural commodities.

Most Ottoman subjects therefore were cultivators. The majority of these in turn were subsistence farmers, living directly from the fruits of their labors. They cultivated, overall, small plots of land, growing a variety of crops for their own consumption, mainly cereals, and also fruits, olives, and vegetables. Quite often they raised some animals, for the milk and wool or hair. Most cultivating families lived on a modest diet, drinking water or a form of liquid yoghurt, eating various forms of bread or porridge and some vegetables, but hardly ever any meat. The animals were beasts of burden and gave their wool or hair which the female members spun into thread and often wove into cloth for family use. In many areas, both in Ottoman Europe and Asia, family members also worked as peddlers, selling home-made goods or those provided by merchants. Some rural families, as we shall see, also manufactured goods for sale to others: Balkan villagers traveled to Anatolia and Syria for months to sell their wool cloth. In western Anatolia, women and men spun yarn for town weavers. And, as just noted, village men in some areas left for work in Istanbul and other far away places. In sum, cultivator families drew their livelihoods from a complex set of different economic activities and not merely from growing crops.

The picture presented above was largely true in 1700 and remained so in 1900: the economy was agrarian and most cultivators possessed small landholdings, engaging in a host of tasks, with their crops and animal products mainly dedicated to self-consumption. But enormous changes over time occurred in the agrarian sector.

To begin with, take the rising importance of formerly nomadic populations in Ottoman agricultural life. The rural countryside, after all, held pastoral nomads as well as sedentary cultivators. Nomads played a complex and important role in the economy, providing goods and services such as animal products, textiles, and transportation. Some nomads depended solely on animal raising while others also grew crops, sometimes sowing them, leaving them unattended for the season and returning in time for the harvest. And it is also true that they often were disruptive of trade and agriculture. For the state, nomads were hard to control and a political headache, and long-standing state pacification programs thus acquired new force in the nineteenth century. As seen above, these sedentarization programs took place at the same time as the massive influx of refugees, a combination that reduced the lands on which nomads freely could move. In the aggregate, animal raising by tribes likely declined while their cultivated lands increased.

A second major set of changes concerns the rising commercialization of agriculture – the production of goods for sale to others. Over time, more and more people grew or raised increasing amounts for sale to domestic and international consumers, a trend that began in the eighteenth century and mounted impressively thereafter. At least three major engines increased agricultural production devoted to the market, the first being rising demand, both international and domestic. Abroad, especially after 1840, the levels of living and buying power of many Europeans improved substantially, permitting them to buy a wider choice and quantity of goods. Rising domestic markets within the empire also were important thanks to increased urbanization as well as mounting personal consumption (see below). The newly opened railroad districts brought a flow of domestic wheat and other cereals to Istanbul, Salonica, Izmir, and Beirut; railroads also attracted truck gardeners who now could grow and ship fruits and vegetables to the expanding and newly accessible markets of these cities. With their rising cash incomes, moreover, the consumption of goods by cultivators in the railroad districts increased.

The second engine driving agricultural output concerns cultivators’ increasing payment of their taxes in cash rather than kind. Some historians have asserted that the increasing commitment to market agriculture was a product both of a mounting per capita tax burden and the state’s growing preference for tax payments in cash rather than kind. In this argument, such governmental decisions forced cultivators to grow crops for sale in order to pay their taxes. Such an argument credits state policy as the most important factor influencing the cultivator’s shift from subsistence to the market. In this same vein, some have asserted that the state’s demand for cash taxes from Ottoman Christians had a crucial role in Ottoman history. Namely, Ottoman Christians and Jews for many centuries had been required to pay a special tax (cizye) in cash, that assured them state protection in the exercise of their religion. Because of this cash tax, Ottoman Christians supposedly became more involved in market activities than their Muslim counterparts. Such an argument, however, does not explain why Ottoman Jews, who also paid the tax, were not as commercially active. The more relevant variable explaining economic success was not cash taxes but rather the Great Power protection that Ottoman Christians but not Jews enjoyed. This protection won Ottoman Christians capitulatory-like benefits, tax exemptions, and the lower business costs that help to explain their rise to economic prominence.

Cultivators’ rising involvement in the market was not simply a reactive response to state demands for cash taxes. Other factors were at work. There was a third engine driving increasing agricultural production – cultivators’ own desires for consumer goods. Among Ottoman consumers, increasingly frequent taste changes, along with the rising availability of cheap imported goods, stimulated a rising consumption of goods. This pattern of mounting consumption began in the eighteenth century, as seen by the urban phenomenon of the Tulip Period (1718–1730), and accelerated subsequently. Wanting more consumer goods, cultivators needed more cash. Thus, rural families worked harder than they had previously, not merely because of cash taxes but because of their own wants for more consumer goods. In such circumstances, leisure time diminished, cash incomes rose, and the flow of consumer goods into the countryside accelerated. The railroad districts are an excellent example of rising consumption desires promoting increased agricultural production. Given the opportunity to produce more crops for sale, cereal growers responded immediately, annually shipping one – half million tons of cereals within a decade of the inauguration of rail service.

Increases in agricultural production both promoted and accompanied a vast expansion in the area of land under cultivation. At the beginning of the eighteenth century and indeed until the end of the empire, there remained vast stretches of uncultivated, sometimes nearly empty, land on every side. These spaces began to fill in, a process finally completed only in the 1950s in most areas of the former empire. Many factors were involved. Families frequently increased the amount of time at work, bringing into cultivation fallow land already under their control. They also engaged in sharecropping, agreeing to work another’s land, paying the person a share of the output. Often such acreage had been pasturage for animals but now farmers plowed the land and grew crops. The extraordinarily fertile lands of Moldavia and Wallachia, for example, had been among the least populated lands of the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century. There, in an unusual, perhaps unique development, local notables brutally compelled more labor from local inhabitants and brought more land under the plow. Elsewhere, millions of refugees brought into production enormous amounts of untilled land. While some settled in populated areas, a process that often caused tensions, vast numbers went to relatively vacant regions, bringing lands under cultivation for the first time (in many centuries). As seen, the empty central Anatolian basin and steppe zone in the Syrian provinces, between the desert and the coast, were frequent refugee destinations. There, government agencies parceled out the land in small holdings of equal size.

Overall, significant concentrations of commercial agriculture first formed in areas easily accessible by water, for example, the Danubian basin, some river valleys in Bulgaria and the coastal areas of Macedonia, as well as the western Aegean coast of Anatolia and the attendant river systems. During the nineteenth century, expansion in such areas continued and interior regions joined the list as well.

Many virginal holdings became large estates, which formed an ever-larger but nonetheless minority proportion of the cultivated land during the 1700–1922 era. On empty lands, large estate formation was made easier because there were no or few cultivators present defending their rights. Such processes occurred in Bulgaria, Moldavia, and Wallachia in the eighteenth century and a century later, on the vast Çukorova plain in southeast Anatolia, as these zones fell under the plow for the first time. By 1900, the Çukorova plain had become a special area of great estates with massive inputs of agricultural machinery. Further east and south, the Hama region of Syria also developed a large landholding pattern. But, in most areas of the empire, severe shortages of labor and the lack of capital hindered the formation of large estates and thus they remained rare. Small landholdings instead prevailed as the Ottoman norm almost everywhere.

There were some increases in productivity – the amount grown on a unit of land. Irrigation projects, one form of intensive agriculture, developed in some areas. More significantly, the use of modern agricultural tools increased during the nineteenth century. By 1900, tens of thousands of iron plows, thousands of reapers, and other examples of advanced agricultural technologies such as combines dotted the Balkan, Anatolian, and Arab rural lands. But more intensive exploitation of existing resources remained comparatively unusual, and most of the increases in agricultural production derived from placing additional land under cultivation.

Rising agricultural production for sale also prompted important changes in the rural labor relations of some areas. Waged labor appeared in some regions of large commercial cultivation. Hence, in west and in southeast Anatolia, gangs of migrant workers harvested the crops for cash wages. Sharecropping rather than wage labor, however, remained more common on large holdings. In Moldavia and Wallachia, as stated above, a form of sharecropping led to near serfdom and some of the worst conditions in the empire. There, eighteenth-century market possibilities had led large holders to rent lands to peasants who paid increasingly heavy rents, taxes, and labor services. At first, for example, peasants owed twelve days of labor but, by the mid-nineteenth century, they worked between twenty-four and fifty days per year – conditions far worse than in the neighboring Habsburg and Romanov empires. Forms of communal exploitation of land, where all worked and shared the produce, prevailed in some Ottoman areas. For example, in some parts of Palestine and in the Iraqi provinces, communal lands were worked jointly, often by tribal members under the direction of their sheikh who supervised distribution of the proceeds.

And finally, foreign ownership of land remained quite uncommon, despite the political weakness of the Ottoman state. While legally permitted to acquire land after 1867, foreigners could not overcome the difficulties posed by the opposition of segments of Ottoman society, including an intact local notable group jealously guarding its privileges, and persistent labor shortages. This seems noteworthy and provides a further indication of the character of the Ottoman Empire during the age of imperialism. While no longer fully independent (see, for example, the discussion of the Public Debt Administration), the Ottoman state still maintained sovereignty over most of its domestic affairs.

Despite visible increases in mechanization during the later nineteenth century, most Ottoman manufactured goods continued to be made by manual labor until the end of the empire. Manufacturing in the countryside, increasingly by female labor, became more important and that by urban-based, male, often guild-organized, workers less so. Further, the global place of Ottoman manufacturing diminished; most of its international markets dried up and production focused on the still vast but highly competitive domestic market. And yet, selected manufacturing sectors for international export significantly expanded production.

The mechanized production of Ottoman goods, at its peak, remained a growing if still minor portion of total manufacturing output. After c. 1875, a small number of factories emerged, mainly in the cities of Ottoman Europe, Istanbul, and western Anatolia, with additional clusters amidst the cotton fields in southeast Anatolia (for cotton spinning) and in various silk raising districts for silk reeling, especially at Bursa and in the Lebanon. Big port cities like Salonica, Izmir, Beirut, and Istanbul held the most concentrated collections of mechanized factories. Most Ottoman factories processed foods, spun thread and occasionally wove cloth. One measure: in 1911, mechanized factories accounted for only 25 percent of all the cotton yarn and less than 1 percent of all the cotton cloth then being consumed within the empire. As in agriculture, the lack of capital deterred the mechanization of production.

While it did not significantly mechanize, the Ottoman manufacturing sector nonetheless successfully underwent a host of important changes as it struggled to survive in the age of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, where technology and the greater exploitation of labor produced a host of cheap and well-made goods. Until the later eighteenth century, goods made by hand in the Ottoman Empire were highly sought after in the surrounding empires and states. The fine textiles, hand-made yarns, and leathers of the eighteenth century, however, gradually lost their foreign markets. By the early nineteenth century, almost all of the high quality goods formerly characterizing the Ottoman export sector had vanished. But, after a half-century hiatus, production for international export re-emerged c. 1850, in the form of raw silk, a kind of silk thread and, more importantly, Oriental carpets. Steam-powered silk reeling factories emerged in Salonica, Edirne, and west Anatolia and in the Lebanon. Particularly in west and central Anatolia, factory-made yarns and dyes combined with hand labor to make mind-boggling numbers of carpets for European and American buyers. The two industries together employed 100,000 persons in c. 1914, two-thirds of them in carpet making. Most workers were women and girls, receiving wages that were the lowest in the entire Ottoman manufacturing sector. In addition, several thousands of other female workers hand made Ottoman lace that imitated Irish lace, finding important markets in Europe.

The overwhelming majority of producers focused on the Ottoman domestic market of 26 million consumers, who sometimes lived in the same or adjacent regions as the manufacturer but also, sometimes, in distant parts of the empire. Producing for a domestic market that itself is difficult to examine and trace, these manufacturers are nearly invisible to the historian’s scrutiny because most did not belong to organizations or firms that left records. Quite to the contrary, they were widely dispersed in non-mechanized forms of production, either working alone or in very small groups located in homes and small workshops, in urban areas and in the countryside. For example, cotton and wool yarn producers, an essential part of the textile industry, worked in numerous locations (some of which are noted on map 8). While there were yarn factories in places like Izmir, Salonica, and Adana, handwork accounted for the yarn in most of the places noted.

During the 1700–1922 period, the importance of guilds in the manufacture of goods fell very sharply but they did not disappear entirely. The evolution, nature and role of guilds (esnaf, taife), however, is not well understood and neither is their prevalence. The economic crisis of the later eighteenth century, with its persistent ruinous inflation, may have accelerated the formal organization of guilds as a self-protective act by producers. Workers banded together to collectively buy implements but often, as in southern Bulgaria, fell under the control of wealthier masters better able to weather the crisis.1 Thus, ironically, labor organizations may have been evolving into a new phase, towards guilds, as Ottoman manufacturing was hit by the competition of the Industrial Revolution.

Guilds generally acted to safeguard the livelihood of their members, restricting production, controlling quality and prices. To protect their livelihoods, members paid a price – namely, high production costs. (Some historians, however, incorrectly have argued that guilds primarily served as instruments of state control.) After reaching agreement among the members, guild leaders often went to the local courts and registered the new prices to gain official recognition of the change. The presence of a steward indeed is one mark of the existence of a guild. At least some guilds had features such as communal chests to support members in times of illness, pay their funeral expenses, or help their widows and children (plate 5).

Guilds in the capital city of Istanbul were very well developed, perhaps more so than anywhere else in the empire. They likewise existed in many of the larger cities such as Salonica, Belgrade, Aleppo, and Damascus. Smaller towns and cities, such as Amasya often also contained guilds, but their overall prevalence, form, and function remain uncertain. There seems to be a correlation between the size of a city and the likelihood that it held a guild – but not every urban center had them.

Janissaries, until 1826, played a vital role in the life of the guilds. Prior to and throughout the eighteenth century, in every corner of the empire and in its capital city, many, perhaps most, Muslim guildsmen had become Janissaries. This was true, for example, in Ottoman Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia, Macedonia, as well as Istanbul. In some cities, the Janissaries themselves were the manufacturing guildsmen but in others, such as Aleppo and Istanbul, they functioned as mafia-like protectors of such workers. At Istanbul and some other big cities, they dominated the building and carrying trades. Time after time and in many cities besides the capital, the Janissaries mobilized to defend popular interests, either as guildsmen or in co-operation with them. Terrorizing governors and deposing grand viziers and sultans, these potent popular coalitions fought for guild privilege and protection, seeking to maintain prices and restrictive practices. In Bulgaria, for example, the Janissaries struggled to protect urban guilds against the rural manufacturing that threatened their jobs.2

Map 8 Some cotton and wool yarnmaking locations in the nineteenth century

Donald Quataert, Ottoman manufacturing in the age of the Industrial Revolution (Cambridge, 1994), 28.

Plate 5 Procession of guilds (esnaf) in Amasya, nineteenth century

Raymond H. Kevorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, eds., Les Arméniens dans l'empire ottoman à la veille du genocide (Paris, 1992). With permission.

Hence Sultan Mahmut II’s destruction of the Janissaries in 1826 also was a terrible blow for the guilds. It fell precisely at the moment when international competition was mounting rapidly in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars. Bereft of protectors in an age when their restrictive practices kept costs too high, the guilds began to disappear. They failed to compete because of what they were: restrictive organizations seeking high prices to benefit members. In Damascus, for example, masters allowed journeymen’s wages to fall so steadily in the 1830s to 1870s that the latter could not accumulate enough capital to open their own shops. Whatever importance they may have possessed before, the guilds’ role as an organizing unit of Ottoman manufacturing declined during the nineteenth century. In some areas, such as Bulgaria and Aleppo, they indeed survived until very late in the period. But often their form evolved from monopolistic producer to a chamber of commerce-like body that merely registered the names of local manufacturers.

It is important to reiterate that manufacturing guilds declined but Ottoman manufacturing did not. Instead, production shifted to workers outside of a guild framework. Sometimes these were nonguild shops in urban areas. In Istanbul, for example, shoemaking flourished at the end of the nineteenth century but as home production and no longer a guild-organized activity. In many regions of the empire, rural manufacturing in homes and workshops played a key role in the survival of manufacturing. The flight to the countryside – to reduce costs by cutting wages – was well underway in the eighteenth century in a number of areas. During the later part of the century, for example, producers began moving out of the north Anatolian city of Tokat, a major manufacturing center, and set up business in nearby smaller cities and villages. Similar patterns have been documented for areas as dissimilar as Bulgaria and the city of Aleppo. Strikingly, women and girls – Muslim, Christian, and Jewish alike – came to play an ever-more important role. Their participation in the workforce hardly was new to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but their level of involvement mounted impressively. In many urban and rural homes, women wove, spun, and knitted goods for merchants who paid piece-work wages. In the Ottoman universe, as everywhere else in the world, women obtained less money for equal work than men. And so, a vital part of the story of Ottoman manufacturing centers on the shift from male, urban, guild-based production to female, unorganized, rural and urban labor.

Entries marked with a * designate recommended readings for new students of the subject.

Akarlı, Engin Deniz. “Gedik implements, mastership, shop usufruct, and monopoly among Istanbul artisans, 1750–1850,” Wissenschaftskolleg Jahrbuch, 1986, 225–231.

*Beinin, Joel. Workers and peasants in the modern Middle East. Cambridge, 2001.

Blaisdell, Donald. European financial control in the Ottoman Empire (New York, 1929).

*Braudel, Fernand. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the time of Philip II, 2 vols. (New York, 1973).

*Doumani, Beshara, ed. Family history in the Middle East. Household, property and gender (Albany, 2003).

Duman, Yüksel. “Notables, textiles and copper in Ottoman Tokat, 1750–1840.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Binghamton University, 1998.

Erdem, Hakkan. Slavery in the Ottoman Empire and its demise, 1800–1909 (New York, 1996).

*Faroqhi, Suraiya. “Agriculture and rural life in the Ottoman Empire (c. 1500–1878),” New Perspectives on Turkey, Fall 1987, 3–34.

Faroqhi, Suraiya and Randi Deguilhem, eds. Crafts and craftsmen in the Middle East: fashioning the individual in the Muslim Mediterranean (London, 2005).

*Gerber, Haim. The social origins of the modern Middle East (Boulder, CO, 1987).

*Goldberg, Ellis, ed. The social history of labor in the Middle East (Boulder, CO, 1996).

Gould, Andrew Gordon. “Pashas and brigands: Ottoman provincial reform and its impact on the nomadic tribes of southern Anatolia 1840–1885.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, 1973.

Hutteroth, Wolf-Dieter. “The influence of social structure on land division and settlement in Inner Anatolia,” in Peter Benedict, Erol Tümertekin and Fatma Mansur, eds., Turkey: geographic and social perspectives (Leiden, 1974), 19–47.

İnalcık, Halil. “The emergence of big farms, çıftlıks: State, landlord and tenants,” in Keyder and Tabak, cited below, 17–53.

Karpat, Kemal. Ottoman population, 1830–1914: Demographic and social characteristics (Madison, 1985).

“The Ottoman emigration to America, 1860–1914,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 17 (2) (1985), 175–209.

Keyder, Ça lar and Faruk Tabak, eds. Landholding and commercial agriculture in the Middle East (Albany, 1991).

lar and Faruk Tabak, eds. Landholding and commercial agriculture in the Middle East (Albany, 1991).

Khalidi, Tarif, ed. Land tenure and transformation in the Middle East (Beirut, 1984).

Lewis, Norman. Nomads and settlers in Syria and Jordan, 1800–1980 (Cambridge, 1987).

*Marcus, Abraham. The Middle East on the eve of modernity (New York, 1989).

Mears, Eliot Grinnell. Modern Turkey (London, 1924).

Meriwether, Margaret L. “Women and economic change in nineteenth-century Aleppo,” in Judith E. Tucker, ed., Arab women (Washington, 1993), 65–83.

Owen, Roger. The Middle East in the world economy, 1800–1914 (London, 1981).

*Palairet, Michael. The Balkan economies c. 1800–1914: Evolution without development (Cambridge, 1997).

*Pamuk, Şevket. The Ottoman Empire and European capitalism, 1820–1913 (Cam-bridge, 1987).

A monetary history of the Ottoman Empire (Cambridge, 2000).

*Quataert, Donald. Social disintegration and popular resistance in the Ottoman Empire, 1881–1908 (New York, 1983).

Ottoman manufacturing in the age of the Industrial Revolution (Cambridge, 1993).

Salzmann, Ariel. “Measures of empire: tax farmers and the Ottoman ancien régime, 1695–1807.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 1995.

Shields, Sarah. Mosul before Iraq: Like bees making five-sided cells (Albany, 2000).

Toledano, Ehud. The Ottoman slave trade and its suppression, 1840–1890 (Princeton, 1982).

*Vatter, Sherry. “Militant journeymen in nineteenth-century Damascus: implications for the Middle Eastern labor history agenda,” in Zachary Lockman, ed., Workers and working classes in the Middle East: Struggles, histories, historiographies (Albany, 1994), 1–19.

Zilfi, Madeline. “Elite circulation in the Ottoman Empire: great mollas of the eighteenth century,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 26, 3 (1983), 318–364.

Politics of piety: The Ottoman ulama in the post-classical age (Minneapolis, 1986).

*Women in the Ottoman Empire: Middle Eastern women in the early modern era (Leiden, 1997).

1This is the conclusion of Suraiya Faroqhi who presently is studying the evolution of guilds.

2Donald Quataert, “Janissaries, artisans and the question of Ottoman decline, 1730–1826,” in Donald Quataert, ed., Workers, peasants and economic change in the Ottoman Empire, 1730–1914 (Istanbul, 1993), 197–203.