In marked contrast to the military and political successes of the 1300–1683 era, defeats and territorial withdrawals characterized this long eighteenth century, 1683–1798. The political structure continued to evolve steadily, taking new forms in a process that should be seen as transformation but not decline. Central rule continued in a new and more disguised fashion as negotiation more frequently than command came to assure obedience. Important changes occurred in the Ottoman economy as well: the circulation of goods began to increase; levels of personal consumption probably rose; and the world economy came to play an ever-larger role in the everyday lives of Ottoman subjects.

On the international stage, military defeats and territorial contraction marked the era, when the imperial Ottoman state was much less successful than before. At the outset, it seems worthwhile to make several general points.

First, at bottom, the Ottoman defeats are as difficult to explain as the victories of earlier centuries. Sometime during the early sixteenth century, as the wealth of the New World poured into Europe, the military balance shifted away from the Ottomans; they lost their edge in military technology and using similar and then inferior weapons and tactics, battled European enemies. Moreover, the earlier military imbalance between offensive and defensive warfare in favor of the aggressor had worked to the Ottomans’ advantage, but now defenses became more sophisticated and vastly more expensive. Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, whose reign had seen so many successes, died before the walls of Szigetvar, poignantly symbolizing the difficulty of attacking fortified cities that had become an increasingly common feature of warfare. Further, Western economies could better afford the mounting costs of the new technologies and defensive combat in part because of the vast infusion of wealth from the New World. The story of Ottoman slippage and west European ascendancy is vastly more complicated, of course, and is continued in the subsequent chapters.

Second, during the eighteenth century, absolute monarchies emerged in Europe that were growing more centralized than ever before. To a certain extent, the Ottomans shared in this evolution but other states in the world did not. The Iranian state weakened after a brief resurgence in the earlier part of the century, collapsed, and failed to recover any cohesive strength until the early twentieth century. Still further east, the Moghul state and all of the rest of the Indian subcontinent fell under French or British domination.

Third, the Ottoman defeats and territorial losses of the eighteenth century were a very grim business but would have been still greater except for the rivalries among west, east, and central European states. On a number of occasions, European diplomats intervened in post-war negotiations with the Ottomans to prevent rivals from gaining too many concessions, thus giving the defeated Ottomans a wedge they employed to retain lands that otherwise would have been lost. Also, while it is easy to think of the era as one of unmitigated disasters since there were so many defeats and withdrawals, the force of Ottoman arms and diplomatic skills did win a number of successes, especially in the first half of the period.

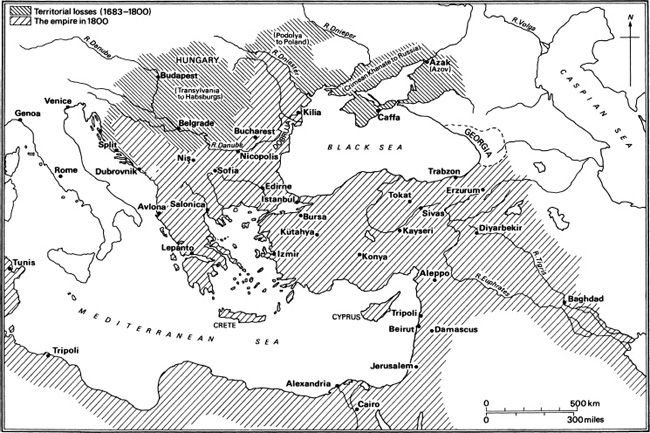

A century of military defeats began at Vienna in 1683 and ended with Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 (map 3). The events immediately following the failed siege in 1683 which turned into a rout were terrible and catastrophic for the Istanbul regime, and include the loss of the key fortress of Belgrade and, in 1691, a military disaster at Slankamen that was compounded by the battlefield death of the grand vizier, Fazıl Mustafa. Elsewhere, the newly emergent Russian foe (the Ottoman–Russian wars began in 1677) attacked the Crimea in 1689 and captured the crucial port of Azov six years later. Yet another catastrophe occurred at Zenta, in 1697, at the hands of the Habsburg military commander, Prince Eugene, of Savoy. The Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 sealed these losses and began a new phase of Ottoman history. For the first time, an Ottoman sovereign formally acknowledged his defeat and the permanent loss of (rather than temporary withdrawal from) lands conquered by his ancestors. Thus, the sultan surrendered all of Hungary (except the Banat of Temeşvar), as well as Transylvania, Croatia, and Slovenia to the Habsburgs while yielding Dalmatia, the Morea, and some Aegean islands to Venice and Podolia and the south Ukraine to Poland. Russia, for its part, fought on until 1700 in order to again gain Azov (which the Ottomans were to win and then lose again in 1736) and the regions north of the Dniester river.

Map 3 The Ottoman Empire, c. 1683–1800

Adapted from Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1914), xxxvii.

Two decades later, the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz ceded the Banat (and Belgrade again), about one-half of Serbia as well as Wallachia. Ottoman forces similarly were unsuccessful on the eastern front and, in a series of wars between 1723 and 1736, lost Azerbaijan and other lands on the Persian–Ottoman frontier. Exactly one decade later, in 1746, two centuries of war between the Ottomans and their Iranian-based rivals ended with the descent of the latter into political anarchy.

The agreement signed at Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 with the Romanovs, similar to the 1699 Karlowitz treaty, highlights the extent of the losses suffered during the eighteenth century. The 1768–1774 war, the first with Czarina Catherine the Great, included the annihilation of the Ottoman fleet in the Aegean Sea near Çeşme by Russian ships that had sailed from the Baltic Sea, through Gibraltar, and across the Mediterranean. In a sense, the vast indemnity paid was the least of the burdens imposed by the treaty. For it severed the tie between the Ottoman sultan and Crimean khan; the khans became formally independent, thus losing sultanic protection. This status left the Ottoman armies without the khan’s military forces that had been a mainstay during the eighteenth century, when they partially had filled the gap left by the decay of the Janissaries as a fighting unit (see below). Equally bad, the Ottomans also surrendered their monopolistic control over the Black Sea while giving up vast lands between the Dnieper and the Bug rivers, thereafter losing the north shore of the Black Sea. Other provisions of the treaty were to be of enormous consequence later on. Russia obtained the right both to build an Orthodox Church in Istanbul and protect those who worshiped there. Subsequently, this rather modest concession became the pretext under which Russia claimed the right to intercede on behalf of all Orthodox subjects of the sultan. In another provision of the treaty, Russia recognized the sultan as caliph of the Muslims of the Crimea. Later sultans, especially Abdülhamit II (1876–1909) expanded this caliphal claim to include not only all Ottoman subjects but also Muslims everywhere in the world (see below and chapter 6). Thus, as is evident, the 1774 Küçük Kaynarca treaty played a vital role in shaping subsequent internal and international events in the Ottoman world. The Treaty of Jassy ended another Ottoman–Russian war, that between 1787 and 1792, and acknowledged the Russian takeover of Georgia. Further, the Crimean khanate, left exposed by the 1774 treaty, now was formally annexed by the Czarist state.

Bonaparte’s motives for invading Egypt in 1798 long have been debated by historians. Was he on the road to British India, or merely blocking Britain’s path to the future jewel in its crown? Or, as his unsuccessful march north into Palestine seems to suggest, was he seeking to replace the Ottoman Empire with his own? Regardless, the invasion marked the end of Ottoman domination of this vital and rich province along the Nile and its emergence as a separate state under Muhammad Ali Pasha and his descendants. Henceforth, Ottoman–Egyptian relations fluctuated enormously. Muhammad Ali Pasha nearly overthrew the Ottoman state during his lifetime (d. 1848), but his successors kept close ties with their nominal overlords. Nevertheless, during the nineteenth century, except for a tribute payment, Egyptian revenues no longer were at the disposal of Istanbul.

While a review of these battles, campaigns, and treaties makes apparent the pace and depth of the Ottoman defeats, the process was not quite so clear at the time. There were a number of important victories, at least during the first half of the eighteenth century. For example, although Belgrade fell just after the 1683 siege, the Ottomans recaptured it, along with Bulgaria, Serbia, and Transylvania, in their counter-offensives during 1689 and 1690. In fact Belgrade reverted to the sultan’s rule at least three times and remained in Ottoman hands until the early nineteenth century. In 1711, to give another example, an Ottoman army completely surrounded the forces of Czar Peter the Great at the Pruth river on the Moldavian border, forcing him to abandon all of his recent conquests. Several years later, the Ottomans regained the lost fortress of Azov on the Black Sea. In a 1714–1718 war with Venice, the Istanbul regime regained the Morea and retained it for more than a century, until the Greek war of independence. Ottoman forces won other important victories in 1737, against both Austrians and Russians. For several reasons, including French mediation and Habsburg fears of Russian success, the Ottomans, in the 1739 peace of Belgrade, regained all that they had surrendered to the Habsburgs in the earlier Treaty of Passarowitz. In the same year, they again obtained Azov from the Russians who withdrew all commercial and war ships from the Black Sea and also pulled out of Wallachia. Even after the disasters of the war that ended at Küçük Kaynarca, the Ottomans won some victories, compelling Russia to withdraw again from the principalities (and from the Caucasus). Catherine did so again in 1792 when she also agreed to withdraw from ports at the mouth of the Danube.

Historians have hotly debated the nature and role of state policies in Ottoman economic change. Some say that in the eighteenth century the state was too controlling, while others argue the opposite. Those in the latter group assert that eighteenth-century regimes in Europe adopted mercantilistic policies that controlled the flow of goods and materials within and across their borders, allowing them to shape the world market in their favor and to become powerful. But, they say, the Ottoman state failed to do so in sufficient measure and, for this reason, it declined in power.

As in the past, the eighteenth-century Ottoman state claimed the right to command and move about economic resources as it deemed necessary. Experience, however, had shown the dangers of such intervention and so, after c. 1600, the state did so only selectively. But, when it did – to provide foodstuffs, raw materials, and manufactured goods for the palace, other state elites, the military, and the inhabitants of the capital city – these interventions powerfully affected producers and consumers. The effects usually were doubly disruptive and negative since the state often paid below-market prices for the goods and, often drained away all or most of a commodity, thus creating scarcities. Crops of entire areas or the manufacturing output of certain guilds were commandeered for particular purposes, for example, to supply the royal household or marching armies. On the Balkan front during the later eighteenth century, for example, nearby regions supplied the army with grain while other supplies, such as rice, coffee, and biscuits flowed from more distant Egypt and Cyprus. The state also devoted considerable energies to the feeding of the population of Istanbul, not from charitable concern but rather fear that food shortages would provoke political unrest. And so innumerable regulations dictated the transport of wheat and sheep to fill the tables of the capital’s enormous population.

Whether such policies strangled the economy during the late eighteenth-century era of wartime crisis and had a decisively negative impact on Ottoman economic development, or whether the state foundered because it was not sufficiently rigorous and mercantilist, cannot be known for certain. It is clear, however, that both sides of the debate give the state more power than it actually had. Indeed, global market forces may have affected the eighteenth-century Ottoman economy more powerfully than state policies. It thus seems more useful to look to other factors for a fuller understanding of Ottoman economic change (see chapter 7). More confidently, we can assert that, after c. 1850 (see chapter 4), the state moved away from such so-called provisioning policies and market forces played a greater role than before.

During the eighteenth century, the sultan most often possessed symbolic power only, confirming changes or actions initiated by others in political life. Although the end of the so-called “rule of the harem” closed a famous version of female political control, elite women remained powerful. The dynasty continued to marry its daughters to ranking officials as a means of forging alliances and maintaining authority. Such support may have become even more important as power shifted out of the palace. Since at least 1656, when Sultan Mehmet IV gave over his executive powers to Grand Vizier Köprülü Mehmet Pasha, political rule had rested in the households of viziers and pashas. Also, warrior skills fell out of fashion in favor of administrative and financial skills as the exploitation of existing resources rather than acquisition of new lands became the major sources of state revenues. Hence, the vizier and pasha households furnished most office appointees, providing the now crucial financial and administrative training, and were often bound to the palace through the marriages of Ottoman princesses. Unlike the “slaves of the sultan” who had ruled earlier, these male and female elites did not remain aloof from society but were involved in its economic life through their control of pious foundations and lifetime tax farms and partnerships with merchants. The entourages of these viziers and pashas served as recruiting grounds for the new elites, providing them with employment, protection, training, and the right contacts. By the end of the seventeenth century, most domestic and foreign policy matters rested in these households.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, however, Sultan Mustafa II unsuccessfully sought to overturn this trend and reconcentrate power in his own hands and that of the palace and the military. Desperately trying to regain power and reposition himself in the political center, Mustafa II somewhat shockingly confirmed hereditary rights to timars, the financial backbone of a cavalry that already was militarily obsolete. But his coup attempt, the so-called “Edirne Event” (Edirne Vakası) of 1703, failed. Thereafter the sultan’s powers and stature were so reduced that he was required to seek the advice of “interested parties” and heed their counsel. This set of events sealed the ascendancy of the vizier–pasha households and of their allies within the religious scholarly community, the ulema, and set the tone for eighteenth-century politics at the center. And so, at a moment when many continental European states were concentrating power in the hands of the monarch, the Ottoman political structure evolved in a different direction, taking power out of the ruler’s hands.

As the sultans lost out in the struggle for domestic political supremacy, they sought new tools and techniques for maintaining their political presence. Beginning in the early eighteenth century, for example, the central state reorganized the pilgrimage routes to the Holy Cities in an effort to enhance its own legitimacy and consolidate power (see chapter 6). (It is, however, unclear if the sultan or other figures at the center initiated this action.) Developments during the so-called Tulip Period (1718–30) more certainly illustrate the subtle means that sultans used to prop up their legitimacy. This Tulip Period, a time of extraordinary experimentation in Ottoman history, was so named by a twentieth-century historian after its frequent tulip breeding competitions. The tulip symbolized both conspicuous consumption and cross-cultural borrowings since it was an item of exchange between the Ottoman Empire, west Europe, and east Asia. Sultan Ahmet III and his Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha (married to Fatma, the Sultan’s daughter), as part of their effort to negotiate power, employed the weapon of consumption to dominate the Istanbul elites. Like the court of King Louis XIV at Versailles, that of the Tulip Period was one of sumptuous consumption – in the Ottoman case not only of tulips but also art, cooking, luxury goods, clothing, and the building of pleasure palaces. With this new tool – the consumption of goods – the sultan and grand vizier sought to control the vizier and pasha households in the manner of King Louis, who compelled nobles to live at the Versailles seat of power and join in financially ruinous balls and banquets. Sultan Ahmet and Ibrahim Pasha tried to lead the Istanbul elites in consumption, establishing themselves at the social center as models for emulation. By leading in consumption, they sought to enhance their political status and legitimacy as well.

Later in the eighteenth century, other sultans frequently used clothing laws in a similar effort to maintain or enhance legitimacy and power. Clothing laws – a standard feature of Ottoman and other pre-modern societies – stipulated the dress, of both body and head, that persons of different ranks, religions, and occupations should wear. For example, Muslims were told that only they could wear certain colors and fabrics that were forbidden to Christians and Jews who, for their part, were ordered to wear other colors and materials. By enacting or enforcing clothing laws, or appearing to do so, sultans presented themselves as guardians of the boundaries differentiating their subjects, as the enforcers of morality, order, and justice. Through these laws, the rulers acted to place themselves as arbitrators in the jostlings for social place, seeking to reinforce their legitimacy as sovereigns, at a time when they neither commanded armies nor actually led the bureaucracy (see also chapter 8).

At the political center and in other Ottoman cities were contests not only within the elites for political domination but also between the elites and the popular masses. In this struggle the famed Janissary corps played a vital role. As seen above, the Janissaries once had been an effective military force that fought at the center of armies and served as urban garrisons. By the eighteenth century, they had become militarily ineffectual but still went to war. Their arms and training had deteriorated so sharply that the Crimean Tatars and other provincial military forces had replaced them as the fighting center of the army. The discipline and rigorous training marking this once elite fire-armed infantry had disappeared by 1700, transforming the corps from the terror of its foreign foes to the terror of the sultans. Already in the later sixteenth century, they had insulted the corpse of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent and denied his son Selim access to the throne until appropriate gifts of money had been offered. Their proximity to the sultan – serving as his bodyguards – and elite military status placed them in the tempting role of kingmakers, with a ready ability to make and unmake rulers.

Certainly during the eighteenth century if not before, the Janissaries’ primary identity shifted from that of soldiers to civilian wage earners. Their ability to live on their military salaries faded as the mounting costs of wars prevented the state from paying Janissary salaries that could keep up with inflation. As garrisons, they physically were part of the urban fabric. To counteract declining real wages, members of the garrisons developed economic connections with the people they were guarding and supervising in Istanbul and other important cities including Belgrade, Sofia, Cairo, Damascus, and points in between. There they became butchers, bakers, boatmen, porters, and worked in a number of artisanal crafts; many owned coffee houses. By the eighteenth century, Janissaries either themselves had entered these trades and businesses or had become mafia-like chieftains protecting trades for a fee. They thus came to represent the interests of the urban productive classes, including corporate guild privilege and economic protectionist policies, and were part and parcel of the urban crowd. And yet their membership in the Janissary corps meant that they were part of the elites. And further, their commander, the agha of the Janissaries, administratively was an important man, sitting on the highest councils of state. As they increasingly became part of the urban economy, the Janissaries began to pass on their elite status. Earlier prohibitions against marriage and living outside the barracks fell away and gradually the sons of city-dwelling Janissaries replaced the peasant boys of the devşirme recruitment (the last devşirme levy was in 1703). By the early eighteenth century, this fire-armed infantry had become hereditary and urban in origin, a position passed from fathers to sons who were Muslim not Christian by birth.

The elite-popular identity of the Janissaries – born among the popular classes and yet part of and linked to the elites – gave them an important role in domestic politics. They repeatedly made and unmade sultans, appointing or toppling grand viziers and other high officials, sometimes as part of intra-elite quarrels but often on behalf of the popular classes. Until their annihilation in 1826, they often served as ramparts against elite tyrannies and a popular militia defending the interests of the people. If we consider them in this role rather than as fallen angels – corrupted elite soldiers and elements of the state apparatus run amok – then the eighteenth century becomes a golden age of popular politics in many Ottoman cities when the voice of the street, orchestrated by the Janissaries, was greater than ever before or since in Ottoman history.

The shifting locus of political power in the center – from the sultans to sultanic households to the households of viziers and pashas to the streets – was paralleled by important transformations in the political life of the provinces. Overall, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, provincial political power seemed to operate more autonomously of control from the capital. Nearly everywhere the central state became visibly less important and local notable families more so in the everyday lives of most persons. Whole sections of the empire fell under the political domination of provincial notable families. For example, the families of the Karaosmanoğlu, Çapanoğlu, and Canıklı Ali Paşaoğlu respectively dominated the economic and political affairs of west, central, and northeast Anatolia; in the Balkan lands, Ali Pasha of Janina ruled Epirus, while Osman Pasvanoğlu of Vidin controlled the lower Danube from Belgrade to the sea. And, in the Arab provinces, the family of Süleyman the Great ruled Baghdad for the entire eighteenth century (1704–1831) as did the Jalili family in Mosul, while powerful men such as Ali Bey dominated Egypt.

These provincial notables can be placed in three groups, each reflecting a different social context. The first group descended from persons who had come to an area as centrally appointed officials and subsequently put down local roots, a marked violation of central state regulations to the contrary. Central control, indeed, had never been as extensive or thorough as the state’s own declarations had suggested. Officials did circulate from appointment to appointment, but the presence of careful land surveys and lists of rotating officials notwithstanding, not as often or regularly as the state would have preferred. Nonetheless, such appointees to positions of provincial authority, whether governors or timar holders, remained in office for shorter periods in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and longer periods during the eighteenth century. That is, by comparison with the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the circulation of centrally appointed officials in the provinces slowed considerably during the eighteenth century. Through negotiations with the center, these individuals gained the legal right to stay. Thus, for example, the al Azm family in Damascus and the Jalili family in Mosul had risen in Ottoman service as governors while, from lower-ranking posts, so had the Karaosmanoğlu dynasty in western Anatolia. In each case family members remained in formal positions of provincial power for several generations and longer.

The second group consisted of prominent notables whose families had been among the local elites of an area before the Ottoman period. In some cases the sultans had recognized their status and power at the moment of incorporation, for example, as they did with many great landholding families in Bosnia. Historians likely have underestimated the retention of local political power by such pre-Ottoman elite groups, and more of these families played an important role in the subsequent Ottoman centuries than has been credited. In another pattern, existing elite groups who originally were stripped of power gradually re-acquired political control and recognition by the state.

The third group – that seems to have existed only in the Arab provinces of the empire – consisted of slave soldiers, Mamluks, whose origins went back to medieval Islamic times. Mamluks, for example, had governed Egypt for centuries, annually importing several thousands of slaves, until their overthrow by the Ottomans in 1516–1517. During the Ottoman era, a Mamluk typically was born outside the region, enslaved through war or raids, and transported into the Ottoman world. Governors or military commanders then bought the slave in regional or local slave markets, brought him into the household as a military slave or apprentice and trained him in the administrative and military arts. Manumitted at some point in the training process, the Mamluk continued to serve the master, rose to local pre-eminence and eventually set up his own household, which he staffed through slave purchases, thus perpetuating the system. The powerful Ahmet Jezzar Pasha who ruled Sidon and Acre (1785–1805) in the Lebanon–Palestine region, and Süleyman the Great at Baghdad, each began as a Mamluk in the service of Ali Bey in Egypt.

The evolution of rule by local notables in the areas of Moldavia and Wallachia – modern-day Rumania–was unique. Local princes, at least nominally selected by the regional nobility, had served there as the “slaves and tribute payers” of the sultans, that is, as tribute-paying vassals, until after 1711, when they were removed because they had offered help to Czar Peter during his Pruth campaign. In their stead, the capital appointed powerful and rich members of the Greek Orthodox community, who lived in the so-called Fener/Phanar district of the capital. For the remainder of the century and, in fact, until the Greek war of independence, these Phanariotes ruled the two principalities with full autonomy in exchange for tribute payments. They implemented the most brutal and oppressive rule seen in the Ottoman world, one that closely approximated serfdom. They were centrally appointed (without even nominal input from regional nobles) but ran the principalities with a totally free hand, thus appearing as exceptions in the picture being offered here.

In general, whether these provincial notables originated from central appointees, pre-Ottoman elites, or Mamluks, they built and maintained intimate ties with the local religious scholarly community of the ulema, as well as merchants and landholders. In the case of the first two notable groups – the descendants of central appointees or pre-Ottoman elites – the marriage of women from notable families was part of their process of local power accumulation. In addition, these elite women held considerable properties and tax farms and administered pious foundations in their own names. They thus wielded considerable personal power that also could be used by the family in its negotiations with local elites or with the Ottoman center.

It seems important to stress that a notable family’s establishment of authority in an area usually was not a rebellion against Ottoman central authority. Rather, local dynasts recognized the sultan and central authority in general, forwarded some taxes to the center and sent troops for imperial wars – actions that reflected the complex and fascinating interaction of mutual need existing between province and center in the eighteenth-century Ottoman world. Indeed, since the late seventeenth century, the central state had been depending on provincial notables for both the recruiting and provisioning of troops. As seen, this relationship gave considerable leverage and bargaining power to the local elites. On the other hand, the notables despatched provincial troops because they needed the central state for legitimation and, as we now shall see, their economic wellbeing as well.

Beginning in 1695, the central state developed lifetime tax farms (malikane), a grant of the right to collect the taxes of an area in exchange for cash payments to the treasury. Very quickly, by 1703, these lifetime tax farms had spread and came into wide use in the Balkan, Anatolian, and Arab provinces alike. Malikane are crucial for understanding how the central state maintained some control in the provinces, long after its imperial military troops had vanished from the area. Vizier and pasha households in the capital controlled the auctions of the lifetime tax farms, letting and subletting them to the local elites of the various provincial areas. In this way the Istanbul elites maintained a shared financial interest with notable families while, since they could remove this lucrative privilege, exercising control over them. Thus, in any test of power, notable families ultimately either yielded or risked losing their lifetime tax farms. The existence of these lifetime tax farm links between the capital and the provinces thus helps to explain why the notable groups in fact usually submitted and sent troops when requested.

This pattern of negotiation, mutual recognition, and control predominated between c. 1700 and 1768 but was shaken during the remainder of the eighteenth century. The fighting in the Russo-Ottoman wars of 1768–1774 and 1787–1792 caused massive disruptions in the battle zones and everywhere imposed enormous manpower and financial strains. In this situation, the notables’ knowledge of and access to local resources became more important than ever, while the wartime chaos gave them greater latitude of action. Thus, it seems, the malikane system partly disintegrated, weakening provincial ties to the center. In this chaotic period, notables such as Jezzar Pasha and the Karaosmanoğlu pursued foreign policies apart from the central state, while others such as Ali Pasha of Janina and Osman Pasvanoğlu undertook separate military campaigns, sometimes against other notables and sometimes against the Russians. Some historians have considered these actions de facto efforts to break away from Ottoman suzerainty. But probably they were not, as the following suggests.

In 1808, one of the notables briefly served as grand vizier, an event that marks the power of provincial groups during this crisis period. Bayraktar Mustafa Pasha, from the Bulgarian areas along the Danube, marched on the imperial capital in an unsuccessful effort to rescue the sultan from his Janissary enemies. Once in Istanbul, he convened an assembly that included many powerful notables from the Balkan and Anatolian provinces. In the ensuing assembly, the notables negotiated with the sultan over the respective rights and power of the contending parties. A formal written document (sened-i ittifak) was prepared but, in the end, went unsigned by the sultan and most of the notables. Nonetheless, the incident illustrates the evolution of the Ottoman state to that point. On the one hand, the sultan’s need for a document ratifying the notables’ willingness to obey him suggests how independent they had become in the context of the late eighteenth-century crisis. On the other hand, the fact that the notables did affirm their support of the sultan, when they collectively held the balance of military power over the central state, suggests the continuing importance of the dynasty in economic and political life, even when the sultanate and central state were very weak. The debate over this 1808 agreement underscores the commitment of provincial notables and central elites to their ongoing reciprocal and mutually profitable relationship. The center badly needed notables’ monies, troops, and other services. The notables for their part relied on the central state and the sultan to arbitrate among the provincial elites’ competing claims by conferring formal recognition of their political power and access to official revenue sources. These were “local Ottomans” and, in however disguised a manner, sought to be and were part of an Ottoman system.

Unlike the notables mentioned so far, the leaders of the Wahhabi movement (and the Saudi dynasty connected to it) categorically rejected the legitimacy of Ottoman rule. The rationale of the Wahhabi emergence must be located in the larger issue of how the non-European world, in this case areas with substantial Muslim populations, sought to deal with the terrible losses being inflicted on them. Muslim states everywhere – in North Africa, the Ottoman lands, Iran, and India – were on the defensive, losing populations and revenues in repeatedly unsuccessful confrontations with one or another European power.

During the eighteenth and subsequent centuries, writers posed the problem of weakness in two distinctly different ways and thus proposed totally dissimilar solutions. On the one hand, the first group viewed the crisis of defeat as a technical problem that could be solved by technical means. Thus, the Ottomans were weak because of technological inferiority to the Europeans. The solution therefore focused on adoption of the best military technology available, as sultans had in the past. In the eighteenth century, this meant borrowing from Europe. And so European military officers were summoned to the capital city; for example, Baron de Tott served from 1755 to 1776 in order to create a modern, rapid-fire artillery corps. Also, the Ottoman Grand Admiral Gazi Hasan Pasha sought to rebuild the fleet according to the highest and most modern standards.

On the other hand, a series of religious activists considered the crisis of defeat as a religious and moral problem, to be resolved through moral reform. This solution was presented more or less simultaneously by the Tijaniyya Sufi order in North Africa, the Wahhabis in Arabia and Shah Waliullah of Delhi on the Indian subcontinent. The three movements each offered a religious answer to the problem posed by the weakness of Islamic states in the world. The Wahhabi movement of concern here aimed to revive society by eliminating all of the allegedly un-Islamic practices that had crept in since the time of the Prophet Muhammad. In central Arabia, Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab (1703–1792) preached the need to return to the principles of early Islam as understood by the great medieval jurist ibn Hanbal. Muslims, Abdul Wahhab said, had forgotten the faith that God revealed to the Prophet.

For the Ottomans, this message posed grave risks. Early in the eighteenth century, they already had lost control of parts of the Arabian peninsula, the Yemen and Hadramaut. Followers of Abdul Wahhab then seized control of much of the rest of Arabia and raided deep into Iraq, thus threatening Ottoman sovereignty in those locations. But this Wahhabi threat was far worse than mere territorial occupation. Abdul Wahhab preached that the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina, under Ottoman protection, were filled with abominations and un-Islamic shrines. These cities, as well as the Islam of the Ottomans, were corrupt, he asserted, and needed cleansing. To do so, Abdul Wahhab allied himself with Muhammad ibn Saud, whose descendants would come to lead the Wahhabi movement, seize, sack, and purify the Holy Cities in 1803 and, more than a century later, found the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Thus, unlike most other provincial leaders, the Wahhabis denied the legitimacy of the Ottoman regime and sought to replace it with their own reformed Islamic state. And they would base their own legitimacy on these teachings and on their control of Mecca and Medina.

This fundamental challenge to Ottoman legitimacy did not go unanswered. At about the same time that Abdul Wahhab began preaching, the central government began placing greater emphasis on protecting the Holy Places and those making the sacred pilgrimage. And from the later eighteenth century the sultans increasingly articulated their role as caliph, leader of Muslims everywhere. Thus, Wahhabi successes in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries helped trigger Ottoman appropriation of these religious symbols (see chapter 6).

Entries marked with a * designate recommended readings for new students of the subject.

*Abou-El-Haj, Rifaat. The 1703 rebellion and the structure of Ottoman politics (Istanbul, 1984).

Aksan, Virginia. An Ottoman statesman in war and peace (Leiden, 1995).

Artan, Tülay. “Architecture as a theatre of life: Profile of the eighteenth-century Bosphorus.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1989.

Cuno, Kenneth. The Pasha’s peasants: Land, society and economy in lower Egypt 1740–1858 (Cambridge, 1992).

Duman, Yüksel, “Notables, textiles and copper in Ottoman Tokat, 1750–1840.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Binghamton University, 1998.

Hathaway, Jane. A tale of two factions. Myth, memory and identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen (Albany, 2003).

*Hourani, Albert. “Ottoman reform and the politics of the notables,” in W. Polk and R. Chambers, eds., The beginnings of modernization in the Middle East: The nineteenth century (Chicago, 1968), 41–68.

Ivanova, Svetlana. “The divorce between Zubaida Hatun and Esseid Osman Aga: Women in the eighteenth-century Shari‘a court of Rumelia,” in Amira El Azhary Sonbol, Women, the family, and divorce laws in Islamic history (Syracuse, 1996), 112–125.

*Keddie, Nikki, ed. Women and gender in Middle Eastern history (New Haven, 1991).

*Khoury, Dina. State and provincial society in the Ottoman Empire: Mosul 1540–1834 (Cambridge, 1997).

Kırlı, Cengiz. “The struggle over space: coffee houses of Ottoman Istanbul, 1780–1845.” Ph.D. dissertation, Binghamton University, 2000.

Masters, Bruce. The origins of western economic dominance in the Middle East: Mercantilism and the Islamic economy in Aleppo, 1600–1750 (New York, 1988).

*McGown, Bruce. “The age of ayans, 1699–1812,” in Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994), 637–758.

Olson, Robert. “The esnaf and the Patrona Halil rebellion of 1730: A realignment in Ottoman politics,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 17 (1974), 329–344.

Pamuk, Şevket. “Prices in the Ottoman Empire, 1469–1914,” International Journal of Middle East Studies (August 2004), 451–468.

Panaite, Viorel. “Power relationships in the Ottoman Empire: the sultans and the tribute-paying princes of Wallachia and Moldavia from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century.” International Journal of Turkish Studies, 7, 1 & 2 (2001), 26–53.

Raymond, André. The great Arab cities in the 16th–18th centuries (New York, 1984).

*Quataert, Donald. “Janissaries, artisans and the question of Ottoman decline, 1730–1826,” in Donald Quataert, ed., Workers, peasants and economic change in the Ottoman Empire, 1730–1914 (Istanbul, 1993), 197–203.

Salzmann, Ariel. “Measures of empire: Tax farmers and the Ottoman ancien régime, 1695–1807.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 1995.

*“An ancien régime revisited: Privatization and political economy in the 18th century Ottoman Empire,” Politics and society, 21, 4 (1993), 393–423.

Shaw, Stanford. Between old and new: The Ottoman Empire under Sultan Selim III 1789–1807 (Cambridge, MA, 1971).

Silay, Kemal. Nedim and the poetics of the Ottoman court: Medieval inheritance and the need for change (Bloomington, 1994).

Sousa, Nadim. The capitulatory regime in Turkey (Baltimore, 1933).

Wortley Montagu, Lady Mary. The Turkish Embassy letters (London, reprint, 1994).

Zilfi, Madeline. “Elite circulation in the Ottoman Empire: Great mollas of the eighteenth century,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 26, 3 (1983), 318–364.

Politics of piety: The Ottoman ulama in the post-classical age (Minneapolis, 1986).

*“Women and society in the Tulip era, 1718–1730,” in Amira El Azhary Sonbol, ed., Women, the family, and divorce laws in Islamic history (Syracuse, 1996), 290–303.

*Zilfi, Madeline, ed. Women in the Ottoman Empire: Middle Eastern women in the early modern era (Leiden, 1997).