This chapter continues the emphasis presented in chapter 7, a depiction of the everyday lives of Ottoman subjects. To do so, it draws on an unusual body of literature to look at social organization, popular culture, and forms of sociability and it offers a cultural investigation into various forms of meaning. Societies as complex as the Ottoman are to be understood not only in terms of administrative decrees, bureaucratic rationalization, military campaigns, and economic productivity. They structure spaces within which people think about the common issues of life, death, celebration, and mourning. Often those spaces are highly gendered and at other times they bring men and women of certain classes together.

All societies, including the Ottoman, consist of complex sets of relationships among individuals and collections of individuals that sometimes overlap and interlock but at other times remain distinct and apart. Persons assemble voluntarily or gather into a number of often distinct groups. On one occasion, they might identify themselves or be identified by others as belonging to a particular group, yet at other times another identity might come to the fore. At a very general level, the Ottoman world may be described as holding the ruling and subject classes and also divisions by religious affiliations such as Sunni Muslim or Armenian Catholic. There were also occupational groups, sometimes but not always organized as corporate groups (esnaf, taife) that we call guilds, as well as huge groups such as women, peasants, or tribes. In all cases, each social group was hardly homogeneous and varied vastly in terms of wealth and status.

We should not straitjacket the Ottoman individual or collective into one or another fixed identity but rather we need to acknowledge the ambiguity and porosity of the boundaries between and among such individuals and groups. On one occasion or another, a particular expression of identity might come to the fore, such as being female but at another time, being a weaver or a Jew might emerge to take precedence over the female identity. Religion, to use another example, functioned as one but not the only means of differentiation. It alone did not confer status but did so in combination with other forms of identity. Nor should we assign a necessarily negative value to differentiation. Difference is a marker distinguishing individuals and groups but it need not be negative, a source of conflict, simply because difference exists. Indeed, in most societies most of the time, differences are merely that. Unusually, they become sources of violence, a theme examined later (chapter 9).

Consider the assertion, too popular in Middle East literature, that by the mere fact of their religious allegiance, Muslims enjoyed a legally superior status to non-Muslims. A glance at the historical records quickly shows that vast numbers of Ottoman Christians and Jews were higher up the social hierarchy than Muslims, enjoying greater wealth and access to political power. For example, in many circumstances, a wealthy Christian merchant possessed greater local prestige and influence than an impoverished Muslim soldier. That is, the category of Muslim or Christian or of being part of the subject or the military class alone did not encompass a person’s social, economic, and political reality. Rather, such a quality was but one of several attributes identifying that individual.

To give another example of the many components that constituted identity, take the religious scholars, the ulema, who supposedly formed a particular social category. How meaningful is it to attach a single identity label, in this case “ulema,” to a very heterogeneous collection of individuals. Some members of the ulema trained for decades at the feet of teachers in the great and prestigious educational institutions such as al-Azhar in Cairo or the Süleymaniye in Istanbul. But others were scarcely literate. At Istanbul during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, rich and powerful ulema families intermarried and formed a distinct upper class group. But, at the same time, lower ranking ulema served in poor neighborhoods and in rural areas. These poor or rural religious scholars, although ulema and thus in one sense part of the same category as the Istanbul elites, had more in common socially, culturally, and economically with their artisan and peasant neighbors than the lofty ulema grandees. In sum, while “ulema” is a useful concept, it alone does not describe the place of the individual in Ottoman society.

Let us now turn to the specific issue of social mobility, the extraordinary movement within and between collectivities during the period. Until the eighteenth century, social mobility mainly occurred via the state apparatus. In earlier years, until perhaps the mid seventeenth century, the expansion of the empire had offered enormous opportunities for advancement. The devşirme, with its administrator and Janissary graduates, had meant that thousands of Christian peasants’ sons rose to high positions of military and political power, enabling the acquisition of wealth and social prestige. Similarly, poor Turkish nomads routinely became the commanders of armies and rulers of provinces, or more modestly, unit leaders, with all the accompanying social and economic privilege. But, as territorial expansion slowed, so did mobility via military channels. Nonetheless, the vizier and pasha households offered graduates ready avenues along other career trajectories. Also, as seen, new civil members of the political elite, sometimes ulema, found sources of wealth outside the state, for example, in pious foundations.

Clothing laws since early times served as important indicators of social mobility and marked out the differences among officials, between officials and the subject classes and also among the subjects. The laws denoted the particular headgear and robes reserved for persons of each particular rank, emphasizing headgear but making distinctions in terms of types and colors of clothing, shoes, belts and other apparel. These laws were intended to divide people into separate groups, each with specific attire, and create a social order in which all knew their limits and gave respect to the notables (plates 6–8). Sometimes the state initiated the clothing laws or their enforcement. But on other occasions subjects did; fearing the erosion of their place in society, they appealed to the state for action. Clothing laws had prevailed in many areas of the “pre-modern” world, and historians have noted the close correlation between fashion changes and changes in the social structure. It seems important that Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (1520–1566) passed a massive set of regulations governing sartorial behavior, just as the empire was completing an era of great social mobility and fluidity. Thereafter, clothing laws remained basically unchanged for more than 150 years, until c. 1720. During this period, one no longer of territorial expansion but rather state consolidation, there were relatively few fashion changes and comparatively little social mobility. But then, starting in the early eighteenth century, a steady stream of clothing laws flowed. At this time, everywhere in the world – in Europe, the Americas, East Asia, and the Ottoman Empire – new groups were emerging which challenged the economic, social, and political power of ruling dynasties and their supporters. In the Ottoman world, status derived from wealth increasingly competed with status gained from office holding, a process begun c. 1650 with the vizier and pasha households based on pious foundations. In the early eighteenth century, two new groups began to emerge. First, thanks to mounting international trade and the general increase in the circulation of commodities, new Muslim and non-Muslim merchant groups developed. And second, the life-time tax farmers (malikanecis) who were created in the 1690s became a potent new source of political power, one bound to state wealth and functioning within the state apparatus.

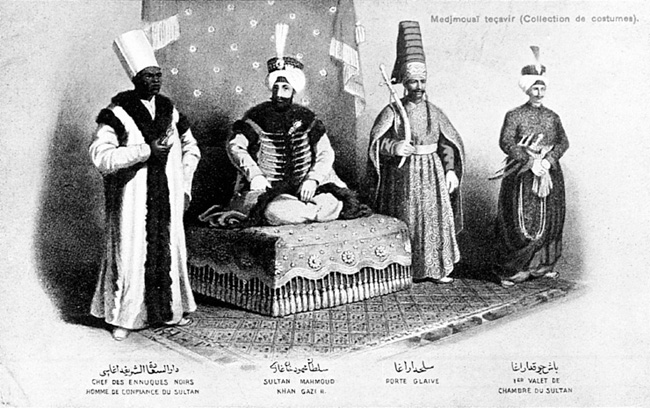

Plate 6 Sultan Mahmut II and some of his personal attendants

Postcard from the Mecmua-ı Tecavür, early nineteenth century. Personal collection of the author.

Plate 7 Grand vizier and some high-ranking attendants and officials

Postcard from the Mecmua-ı Tecavür, early nineteenth century. Personal collection of the author.

Plate 8 Police, military, and other officials

Postcard from Mecmua-ı Tecavür, early nineteenth century. Personal collection of the author.

Already during the Tulip Period, 1718–1730, the new wealth was evident and the court used competitive displays of consumption in order to keep the new rival groups at bay. Hence, Sultan Ahmet III and his son-in-law, Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha sponsored competitions of palace building and festivities, as well as other consumption displays such as tulip breeding. Their primary targets perhaps mainly were the lifetime tax farmers since international trade at this time was just beginning to become prominent.

Beginning in the Tulip Period and for the remainder of the eighteenth century, a host of clothing laws appeared, for example, in the 1720s, 1750s and 1790s. These laws preached for a status quo that was all too fugitive – for morality, social discipline, and order – and ranted against women’s and men’s clothing that was variously too tight, too immodest, too rich, too extravagant, or the wrong color. In the 1760s, laws condemned merchants and artisans for wearing ermine fur, reserved for the sultan and his viziers. In 1792, women’s overcoats were said to be so thin as to be translucent and so were prohibited while, just a few years before, non-Muslims allegedly were wearing yellow shoes, a color permitted only to Muslims. Vibrant social change and mobility was occurring, to the consternation of the state and the social groups whose privileged place was being threatened. And so, they demanded that the state do something about it. To maintain its own legitimacy and the loyalties of the challenged groups – who often were from the older merchant groups and the state servant ranks – the state enacted this barrage of laws.

Social change and mobility became so extreme and so beyond the state’s ability to control that, in 1829, Sultan Mahmut II overnight gave in and abolished the old social markers based on wearing apparel. Instead, a new set of regulations demanded that all officials wear the fez, that is, exactly the same headgear. With this action, all state servants looked the same: the different turbans and robes of honor were gone. The religious classes specifically were exempted from the legislation. Ottoman women, for their part, simply were ignored. Moreover, the Sultan intended that the non-official classes put on the fez as well, to create an undifferentiated Ottoman subjecthood without distinction. The 1829 law reversed the previous practice of using clothing legislation to create or maintain difference. Instead, it sought to impose visual uniformity among all male state servants and subjects.

Plate 9 Court functionaries at a ceremony in the Topkapi palace during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamit II

Carney E. S. Gavin et al., “Imperial self-portrait; the Ottoman Empire as revealed in the Sultan Abdul Hamid’s photograph albums,” special issue of Journal of Turkish Studies (1998), 98. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Long-standing rules that had sought to distinguish cobblers from silversmiths and merchants from artisans and Muslims from non-Muslims disappeared overnight. In wearing the fez, government officials and the rest of male society (outside of the religious classes) thereafter were to look the same before the monarch and to one another. There were to be no clothing indicators of occupation, rank, or religion. The 1829 law thus anticipated the more famous Tanzimat decrees of 1839 and 1856 that sought to establish equality among all Ottoman subjects, regardless of religious or other group identity.

Many welcomed the final disappearance of the old markers that had strained and finally collapsed in the face of mounting social change (plates 9 and 17). The fez, frock coat, and pants became the new “uniform” of the official classes. Now free of legal restraints, many wealthy merchants, who primarily were non-Muslims, immediately adopted the new attire in order to escape the discrimination that difference sometimes had brought. But other Ottoman subjects rejected the effort to create uniform clothing and instead created new social markers. At the lower end of the social scale, for example, Ottoman workers – Muslims and non-Muslims alike – often rejected the fez. This was not a reactionary measure opposing equality of Muslim and non-Muslim. Rather, the workers were insisting on their identity as workers, on retaining class difference and a solidarity against a state that was attacking guild privilege, had destroyed their Janissary protectors, and was dismantling economic programs that long had afforded privilege and protection to workers. Many but not all Muslim and non-Muslim workers insisted on headgear that marked them as a distinct group. See plates 5, 10, and 11 that show some workers with the fez and others retaining distinctive headgear. Further up the social ladder, many wealthy Muslims and non-Muslims displayed their new wealth, power, and social prominence by dressing extravagantly in the latest fashions. In the process, they made a mockery of the 1829 legislation attempting to impose uniformity, modesty, and simplicity.

Plate 10 Example of workers’ headgear and clothing, later nineteenth century: kebab seller and others, probably Istanbul

Sébah and Joaillier photograph. Personal collection of the author.

The mounting sartorial heterogeneity of the nineteenth century thus mirrored rising social fluidity and the ongoing dissolution of the old boundaries among various occupational and religious groups and ranks in Ottoman society. These extraordinary and accelerating changes in dress also occurred among Ottoman women, as seen below, reflecting the transformations that marked eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Ottoman society.

Plate 11 Example of workers’ headgear and clothing, later nineteenth century: textile workers, Urfa, c. 1900

Raymond H. Kevorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, eds., Les Arméniens dans l’empire ottoman à laveille du genocide (Paris, 1992). With permission.

In the Ottoman world, the home often was the testing ground for social innovation. Women first tried out fashions in private, at home, and from there took them out into the public spaces. While this process likely was not uniquely Ottoman, it was not a universal principle either. In nineteenth-century Japan, for example, western clothing was worn in public spaces but inside the home older forms of clothing prevailed. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Ottoman women in their residences had worn baggy pants (shalvar) and a flowing, three-skirted, household dress. As the nineteenth century wore on, however, urban elite women began to wear new fashions at home, shifting to puffy skirts, corsets for a thin-waisted look, and a chignon hairstyle. Following these experiments at home, they wore the new styles in the public spaces, taking care to conceal them with a long skirted veil that covered practically every part of the body. Over time, this long skirted veil became transformed into something resembling European women’s coats and the veil became more and more transparent (plate 12). Still later, c. 1910, the flapper look appeared.

Not only fashions but also other social innovations were first tested in the home. For example, the prevailing Ottoman practice of separate socializing for males and for females was experimented with and then broken at home. Among elite nineteenth-century families, initially in Istanbul and the port cities and then elsewhere, couples began visiting close friends together, as couples, and the practices of women visiting women and men visiting men diminished.

Specialists argue over the meaning of the western clothing that Ottoman women and men wore. Some analysts state that the adoption of western attire and other cultural forms reflected westernization, or the desire to be part of the West. This view seems difficult to maintain. If this is true, how then are we to understand the widespread Ottoman use of Indian textiles in the early nineteenth century – were the Ottomans trying to become Indian? Others see the adoption of western fashions in a more complex way, not as an effort to integrate into western society but rather part of a larger “civilizing process” during the nineteenth century. By donning lace dresses or cutaway coats in the latest Parisian fashion, individuals were seeking to mark their social differentiation and modernity – that they were part of the new, not the old, and were superior to those in their own society who did not wear such attire (plate 13).

We need to remember the extraordinary variety of the Ottoman world that stretched from Belgrade to Istanbul to Aintab to Damascus and Beirut. My goal here is not to make categorically true statements about all homes but rather to leave an impression of Ottoman domestic life, both urban and rural, during the 1700–1922 period. With that in mind, let us begin.

The spatial layout of urban homes before the nineteenth century was more conducive to separate gender spaces than rural homes. In many urban homes, there was a selamlik section, the predominantly male space, at the front while the haremlik, the female space, was located elsewhere. This haremlik may have been primarily an urban, upper-class phenomenon. Urban homes often held the selamlik room, which the oldest male had the prerogative to use, in the center with independent rooms off of it but without corridors linking these to each other. Males socialized in the one space, and females in the other. Before the nineteenth century, in virtually all urban elite and non-elite homes, furnishings consisted of pillows on raised platforms placed against the walls. People sat on pillows on carpeted or matted floors. When eating, they gathered around large trays, raised perhaps a foot above the floor, and ate with their hands from communal dishes. Wealthy people ate meat, previously cut into small pieces. Rooms tended to be multi-purpose; the entertaining areas of the male and female sections converted to bedrooms in the evening. Furnishings often were modest. For example, the home of a wealthy urban family in Syria in the 1780s contained carpets, mats, cushions, some small cotton cloths, copper and wood platters, stewing pans, a mortar and portable coffee mill, a little porcelain, and some tinned plates.

Plate 12 Female outdoor attire, c. 1890, likely Istanbul

Edwin A. Grosvenor, Constantinople (Boston, 1895).

Plate 13 Female indoor attire: Muhlise, the daughter of photographer Ali Sami, Istanbul, 1907

From the collection of Engin Çizgen, with thanks.

In the early nineteenth century, important furnishing changes were taking place. At the port city of Izmir, homes of wealthy merchants were filling up with goods from Paris and London, including knives, forks, tables, chairs, and English fireplaces along with English coal. By the end of the century, chairs, tables, beds, and bedsteads had become relatively common in elite homes in Istanbul and the port cities and were spreading to inland cities and towns. As the new furniture moved in, the functions of Ottoman domestic spaces changed. Multi-purpose rooms of the past became single purpose. Separate bedrooms, living rooms, and dining rooms emerged, each filled with specialized furniture that could not be moved about or stored in order to use the room for another purpose.

Turning now to homes in rural areas, we find that many peasant dwellings divided simply into three rooms, one for sleeping, and the others for cooking/storage and for sitting. These were very small spaces with no real spatial division by gender. Here is a nineteenth-century description of village homes in the Black Sea coastal areas around Trabzon:

The cottage is fairly clean, especially if its inhabitants are Mahometan [Muslim], and is much more spacious than the dwelling of the town artizan. Regularly it has three rooms, one for sleeping, one for sitting in, and one for cooking… Glass is unknown; the roof, made of wooden shingles in the coast region, of earth if in the interior, is far from water-tight, and the walls let in wind and rain everywhere…

The peasant’s food is mostly vegetable, and in great measure the produce of his own ground. Maize bread in the littoral districts, and brown bread, in which rye and barley are largely mixed for the inland provinces, form nine-tenths of a coarse but not unwholesome diet. This is varied occasionally with milk, curds, cheese, and eggs; the more so if the household happens to possess a cow and barn-door fowls. Dried meat or fish are rare but highly esteemed luxuries. Water is the only drink…1

To demonstrate the variety of rural housing in the various areas of the empire, consider another description, this one from the Bulgarian regions during the nineteenth century:

The houses of the better class of peasant farmers are solidly constructed of stone, and sufficiently comfortable. The cottages of the poorer class, however, are of the most primitive style of architecture. A number of poles mark out the extent to be given to the edifice, the spaces between them being filled up with wattles of osier, plastered thickly within and without with clay and cow dung mixed with straw…The interior of an average cottage is divided into three rooms – the common living-room, the family bedroom, and the storeroom. The floor is of earth, beaten hard, and is covered with coarse matting and thick homemade rugs. The furniture consists chiefly of cushions covered with thick woven tissues which also serve the family as beds… Like all the peasants of Turkey [the Ottoman empire], the Bulgarians are most economical and even frugal in their habits. They are content with very little, and live generally on rye bread and maize porridge, or beans seasoned with vinegar and pepper, supplemented by the produce of the dairy.2

The homes of nomads were even simpler than those of sedentary peasants. In the late eighteenth century, the bedouin of Syria lived in tents, within which were weapons, a pipe, a portable coffee mill, a cooking pot, leather bucket, coffee roaster, mat, clothes, black wool mantle and a few pieces of glass or silver.

In the 1870s, by comparison, some three-quarter million pastoral nomads of the Erzurum–Diyarbekir region lived in the following manner:

During the winter they live in small huts constructed of loose stone, but of a far more miserable character, if possible, than those … situated in low-lying valleys. Their flocks and horses are penned and tethered in similar but larger buildings communicating with the dwelling chamber, as in other villages already noticed. In spring and summer they migrate to the hills in their or adjacent districts, where they live in spacious goathair or woollen tents. Their food is the same as that of the agricultural class… with them, also, meat is rarely used, unless travellers of consequence alight at their homes … Their furniture is rather better than that of the other classes, inasmuch as their females manufacture good carpets, with which every family is provided, in addition to fine felts.3

The economic, social, and political transformations reflected by the changes in Ottoman apparel and private spaces, that were more pronounced in urban centers than rural areas, also can be seen in the emergence of new public spaces in the nineteenth century. Control of public space should be understood as an extension of the struggle for political clout and social pre-eminence. Unfortunately, virtually all of the evidence presented here applies only to the capital city. Istanbul and the port cities felt the kinds of developments traced below earlier and more acutely than elsewhere in the empire, for in these places the economic changes were the most pronounced.

Sites of public display, where persons came out to promenade and show their finery, were important places of socialization in pre-modern cities with their narrow, winding, and often very muddy streets. In Istanbul, the most important sites for centuries were two stream valleys named the Sweet Waters of Europe, situated up the Golden Horn, and the Sweet Waters of Asia, on the other side of the Bosphorus. There, the wealthy and powerful of the imperial capital long had congregated, picnicked, and paraded their wealth and power. In the early nineteenth century, “the poorer classes who are unable to command a carriage, or a caique [small boat], will cheerfully toil on foot from the city, under a scorching sun, in order to secure their portion of the festival” (see plates 14 and 15).4 The major religions during the nineteenth century maintained a certain sharing of the spaces: on Fridays, crowds of Muslims dominated while on Sundays, Christians took over the places.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, however, the public gradually abandoned these sites in favor of new places of public display. Unlike at the two Sweet Waters locations, rich non-Muslims dominated these new public spaces, setting the tone with their fashion finery. Both of these new public spaces were cemeteries and adjacent open areas – named the Grand and Petit Champs du Morts – and were located in the Pera district, that is, in the predominantly European and Ottoman Christian sections of the city. To these places and not to the Sweet Waters increasingly went the fashion leaders, the fancy people, the trend setters, and those who wanted to know the latest fashions. Thus, non-Muslims replaced the Muslims as fashion leaders. Social status was contested in the clothing competitions of the public spaces. While the fez and frock coat became the standard attire of the official classes, the non-Muslims led the way in wearing elegant, expensive, up-to-the-minute fashions from Paris.

Plate 14 Sweet Waters of Europe, c. 1900

Personal collection of author.

Plate 15 Sweet Waters of Asia, c. 1900

Personal collection of author.

Significantly, non-Muslims as a group were the fashion setters and the economic leaders but not the political leaders. A tension existed between their mounting economic wealth, their social/sartorial leadership roles and their politically subordinate position, a contradiction which the 1829 clothing legislation and the 1839 and 1856 reform decrees sought to resolve.

In the Ottoman world, the coffee house served as the pre-eminent public male space. Coffee houses initially appeared in Istanbul with coffee in 1555, entering via Aleppo and Damascus from Arabia, the source of the first coffee, mocha. Soon after, c. 1609, tobacco arrived. Thereafter, the combination of coffee and tobacco became hallmarks of Ottoman and Middle East culture, inseparable from hospitality and socialization. The two over time became the first truly mass consumption commodities in the Ottoman world. From its introduction until the second half of the twentieth century, the coffee house functioned as the very center of male public life in the Ottoman and post-Ottoman world. (Thanks to television, it now seems to be dying in most areas of the Middle East.) Coffee houses were everywhere: in early nineteenth-century Istanbul, for example, they accounted for perhaps one in five commercial shops in the city.5 Hence, the vast expansion of male gendered public spaces in the Ottoman world was intricately linked with a consumer revolution that began in the seventeenth century (and took on new forms with the accelerating changes in clothing fashion of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries). In these coffee houses, men drank, smoked, and enjoyed story telling, music, cards, backgammon, and other forms of entertainment that sometimes were held outside, in front of the coffee house.

Bathhouses, for their part, provided public gendered spaces for female (and male) sociability. In earlier times, indoor plumbing, although known, was exceptional. Most people did not have an in-home water source and so depended on public bathing facilities. This hygienic need for bathhouses was compounded by the powerful emphasis that Islam and the Muslim world places on personal cleanliness. As a result, bathhouses were a routine presence in Ottoman towns and cities. Larger ones afforded separate facilities for men and for women while the smaller bathhouses scheduled times for women only and for men only. Bathhouses provided women with crucial spaces for socialization outside the home. There they not only met friends but also negotiated marriage alliances and made business contacts.

Eating out places were very uncommon until the later nineteenth century. But men and women routinely traveled to market places, an important public site. There, women, dressed in their public garb, bought and sold from merchants on a regular basis. Similarly, the areas before places of worship – mosques, churches, and synagogues – afforded spaces for conversation, entertainment, and business negotiations.

In such spaces, the Ottoman public enjoyed story telling by professionals who recited tales, some of them Homeric in length and speaking of sultans and heroes and great deeds. Other reciters spoke of life, of love, and emotion, often in poetic form, and sometimes quite explicitly. Take these examples from a seventeenth-century folk poet, very popular in later years as well:

… tell them I’m dead

Let them gather to pray for my soul

Let them bury me by the side of the road

Let young girls pause at my grave

or

Save me, O lord

My eyes have seen her ripe breasts

How I long to gather her peaches

To kiss the down on her cheeks6

Shadow puppet theater (karagöz), that today still is enjoyed from Greece to Indonesia, was perhaps the most popular entertainment in Ottoman times. Audiences gathered before a translucent screen. Behind the screen worked one or more puppetmasters who used short poles to hold the paper-thin, colored, shadow puppets against the screen, moving them about as the plot dictated. These shadow puppets were made of scraped animal skin, incised and multi-colored. To the sides of the screen were fixed stage props (göstermelik), made of the same materials. There were scores of fixed stories immediately familiar to the audiences watching them – about love, politics, folly, and sagacity – based on folk wisdom with the characters representing the common voice. In addition, the performers prepared impromptu plots reflecting current political conditions. For example, karagöz masters in Aleppo ridiculed the Janissaries who were returning from their failed campaign in the Ottoman–Russian War of 1768. The shadow puppet theaters were places of social commentary, safe places from which to criticize contemporary events, the state, and its elites.

In the nineteenth century, competing forms of entertainment began arriving from Western Europe. Many foreign troupes performed operas in Istanbul during the late 1830s while Western theater arrived in 1840, also performed by a traveling company. Within several decades, the performances were by Ottoman subjects, not foreigners, and even some smaller provincial towns had their theater companies. Movies arrived in Istanbul in 1897, two years after their invention in France by the brothers Lumière.

In the world of Ottoman sports, wrestling was very popular, particularly in the Balkan provinces while archery and falconry enjoyed a following among elites. By the late nineteenth century, a host of competing sports activities had arrived from abroad in Istanbul and the port cities such as Salonica. These included football (soccer), tennis, cycling, swimming, flying, gymnastics, croquet, and boxing. Similarly, a football and rugby club appeared in Izmir in 1890. Football caught on somewhat while other sports did not; for example, tennis in Istanbul remained within the palace grounds (as it did in contemporary imperial China).

The Sufi brotherhoods and lodges, which included men and women, played a central role in Ottoman social life and were another important place of socialization outside the home. In this case, the place exclusively was Muslim and contained within it both male and female spaces, for visitors as well as adherents. Some brotherhoods had emerged with the Turkish invasions of the Middle East and had assisted in the Ottoman rise to power during the fourteenth century. Many thus were located in areas where ethnic Turks had settled, such as Anatolia and parts of the Balkans. But they also were thoroughly commonplace across the Arab lands as well. Everywhere, these brotherhoods were crucially important both in the realm of religion and for their social functions. Although the mosque, its prayers, rituals, and instruction were central to the religious life of Ottoman Muslims, the brotherhoods’ religious importance can hardly be overstated. The beliefs and practices of the brotherhoods provided many women and men with a set of vital, personal, and intimate religious experiences that alternately combined with or transcended those of the mosque. Also, the brotherhoods served as among the most important socialization spaces for Muslim men and women in Ottoman society, providing members with a host of relationships important in social, commercial, and sometimes political life. It is often said that, during the nineteenth century, most residents of the imperial capital and many major cities were either members or affiliates of a brotherhood.

Brotherhoods formed around loyalty to the teachings of a male or female individual, the founding sheikh, usually revered as a saint. These holy persons, by their example and teachings, had formed a distinctive path to religious truth and to the mystical experience. The teachings of each brotherhood varied but shared in a common effort to have an intimate encounter with God and find personal peace. Members gathered in a lodge (tekke), for communal prayer (zikr) and to perform a set of specific devotional practices. The Mevlevi brotherhoods whirled about in circles seeking to gain the mystic vision, others chanted. Financed by members’ contributions, lodges in nineteenth-century Istanbul most often were ordinary buildings, usually the house of the sheikh who was its living leader. Many lodges, however, consisted of a complex of buildings that included a library, hospice, and tomb, a cell for the sheikh and the students, both men and women, as well as classrooms, a kitchen, public bath, and toilets. In addition, “grand lodges” (asitane) held residential buildings for families, single persons, and for visitors, male and female, in addition to the library, prayer hall, and kitchen. In late Ottoman times, Istanbul alone contained some twenty different brotherhoods that together possessed 300 lodges (compared with perhaps 500 in the seventeenth century). Among the most popular brotherhoods in nineteenth-century Istanbul were the Kadiri with fifty-seven lodges and Nakshibandi with fifty-six lodges. The Halveti, Celveti, Sa’di and Rufai also were important, followed by groups such as the Mevlevi with fewer than ten lodges. The brotherhoods often drew on distinct social groups. The Mevlevis, for example, were small in size but politically powerful because its members belonged to the upper classes and included many state leaders. The Bektashis, by contrast, drew from the artisanal and lower classes. They had been chaplains of the Janissaries and thus were suppressed in 1826.

The brotherhoods, as seen, had close connections to holy men and women, saints who were highly revered in the Ottoman world. Visiting their tombs was widely practiced and supplicants often arrived in families or in groups of lodge members. Visitors prayed at the tombs for the saint’s intercession, lighting candles and sleeping near or on the tomb, a few hours for most illnesses but up to forty days for graver diseases and mental problems. Women often prayed to conceive a child or for a successful pregnancy. To obtain the blessings of the saint, supplicants frequently tied ribbons to the bushes nearby or to the grillwork of the tomb structure; or they placed a water offering or a shirt or piece of clothing on the tomb.

Many Muslim shrines arose on sites of religious importance that dated back to the Christian era, places which in turn often had pre-Christian significance. At least ten tombs in the Balkan provinces were devoted to the Muslim saint Sari Saltuk – who possessed the attributes of St. George – and one of these, in Albania, is in a grotto where the saint reportedly had killed a dragon with seven heads. Sanctuaries of saints frequently served both Christians and Muslims, for example a Bektashi shrine on Mount Tomor in Albania was dedicated to the Holy Virgin. In central Anatolia, within a single shrine stood a Christian church at one end and a mosque at the other while in the city of Salonica, the Church of St. Dimitri had become a mosque but the saint’s tomb remained open to Christians. Not unusually, Christians and Muslims in many areas celebrated the holy day of the same person on the same day in the same place, but using different names for the saint. At Deli Orman, in the Balkans, the Muslim Demir Baba and the Christian St. Elias were both remembered on August 1. Near Kossovo, there was a shrine of a different sort, preserving blood from the body of Sultan Murat I, who was killed on the battlefield in 1389, and later transported to Bursa for burial.

Holidays were a special time, to dress up in the best clothes, go for a promenade and enjoy special entertainments. Almost all Ottoman holidays commemorated religious events and drew on a number of different religious traditions and calendars. In the late nineteenth century, official calendars noted the day according to the Julian system for Christians; the hijra for Muslims (based on an event in the life of the Prophet Muhammad); and the financial calendar. The notable exceptions to religious festivals were celebrations connected to the life of the dynasty, including weddings and circumcisions and, during the late nineteenth century at least, empire-wide observations of the sultan’s birthday. To give another example of another non-religious holiday: in the early twentieth century, miners and officials in the coal mining districts of the Black Sea coast gathered to commemorate the accession anniversary of the sultan, a ceremony intended to foster loyalty and a sense of wider identity, and perhaps community among managers and workers (plate 16). Some holidays in earlier times had celebrated great military victories. In the eighteenth century, when these were few, an annual banquet prior to the departure of the fleet celebrated its coming tour of the Mediterranean.

Plate 16 Holiday ceremony, Black Sea region c. 1900 Personal collection of author.

Certain religious holidays went beyond the particular religion: the Muslim Ramadan in part was a holiday for all (see below). The blessing of Muslim fishing vessels occurred on the feast day of the Epiphany, a Christian festival. Among Ottoman Christians, St. John’s Day in July and the Assumption of the Virgin in August were important days: Greek women, even the humblest of them, the fishermen’s wives, are said to have worn elegant dresses of silk or velvet and cloaks lined with expensive furs. There were many Muslim holidays, including days that commemorated the birth of the Prophet or his ascent into heaven.

Ramadan, however, easily loomed as the most important holiday, the most significant time of public life in the Ottoman world.7 This greatest of all Muslim holidays is the ninth month of the hijra calendar. In this month, the Koran was revealed, the “Night of Power” (Leyl ul qadir). Ramadan was doubly and triply important for during this month fell the anniversaries of the birth of Hüseyin, and of the deaths of Ali and of Khadija – three vitally important figures in Islamic history and religion. Moreover, Ramadan also celebrated the anniversary of the battle of Badr, the first important military victory of the Prophet Muhammad. To honor these events, especially the Night of Power, Muslims observed a month of fasting, Ramadan. From the first crack of sunrise until sunset they are enjoined not to eat, drink (not even water), smoke, or have sex. Cannon shots signaled sunset as well as the onset of the fast at sunrise. The fast month ended with the Şeker Bayramı, one of the two major holidays in the Islamic calendar.

During Ramadan, a time of intense socializing, the rhythm of daily life profoundly changed. Istanbul and the other cities in effect shut down during the daytime, both in the public and private sectors. But then, shops and coffee houses stayed open all night long, lighted by lamps. Only during Ramadan did night life flourish – the holiday changed night into day. In the weeks before, houses were cleaned, insects removed, pillows re-stuffed and preparations begun for the many special foods. The daily breaking of the fast, a celebratory meal named the iftar, brought forth foods and breads especially prepared for the occasion. A central social event in this intensely social month, the iftar meal each day provided the occasion for visiting and for hospitality. Grandees maintained open tables and strangers – the poor, beggars – would show up, be fed and given a gift, often cash, on departure. In the eighteenth century, the grand vizier routinely gave presents – gold, furs, textiles, and jewels – to state dignitaries at iftar. Sheikhs of various brotherhoods were especially honored, often with fur-lined coats. These protocol visits at home among officials, however, actually were legislated out of existence during the 1840s; thereafter, official visiting occurred only in the offices. Lower down in the social order, masters gave gifts to their servants and to persons doing services for them, for example, merchants, watchmen and firemen (tulumbacıs). In the mid-nineteenth century, the poor presented themselves at the palace of Sultan Abdülmecit, to receive gifts from the sultan’s aides de camp. (This had been a more general custom until the Tanzimat reforms but thereafter was restricted to the iftar during Ramadan.) During at least the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, on the fifteenth day of Ramadan, the sultans visited the sacred mantle of the Prophet Muhammad within the Topkapi palace and distributed sweets (baklava) to the Janissaries. After 1826, sultans continued to honor the army, giving them special Ramadan breads. During the reign of Sultan Abdülhamit II, a different regiment dined at Yildiz palace each evening and received gifts.

Ramadan provided a month of distractions, not only by exchanging home visits but also through a host of special public amusements. It was the grand season for karagöz shadow puppet theater and performers memorized twenty-eight different stories in order to present a different one each night up to the eve of the bayram. Similarly, as theater developed in the later nineteenth century, Ramadan became the theater season, with special shows customary by the early twentieth century. And, there were special Ramadan cinema shows in Istanbul within a decade of the introduction of movies. In the eighteenth century, social events had turned on the iftar and included promenades, karagöz, and coffee houses while, in the nineteenth century, these had expanded to include new entertainment forms such as the theater and cinema. Ramadan, in a certain sense, was a month of carnival when social barriers fell or, as in carnival in Europe, the rules were suspended. Hence, for example, the state during the early nineteenth century generally forbade men and women from going about together in public but an imperial command allowed them to do so at the Şeker Bayramı.

And, this month also was a time of heightened religious sensibilities and religious activity. Across the empire, ulema continuously read the Koran in the mosques of towns and cities until the eve of the Şeker Bayramı. During Ramadan, many visited holy places and the tombs of the saints including, in Istanbul, the Eyüp shrine as well as the graves of their relatives where they passed the entire night in tents. After the Şeker Bayramı prayer, families gathered in silence at the tombs of parents and close relatives. Also, the ranking ulema offered special lessons, with readings of the Koran, before the sultan. Students preparing for a career in the religious ranks left their schools during Ramadan and toured the countryside preaching, receiving both money and gifts in kind from the villagers. In Istanbul, in a practice that may have begun during the Tulip Period of the early eighteenth century, the mosques and minarets were strung with lights, sometimes in the form of words or symbols (called mahya). Until public lighting was installed in 1860, the effect of such lights must have been amazing. Imagine the impact of these strings of lighted words and symbols on an otherwise-darkened city of nearly a million, normally lighted only by the lamps that persons were required to carry.

Ramadan also promoted inter-communal relations. Many non-Muslims were invited to break the fast at the imperial palace, a practice that set and mirrored the standard of behavior for the rest of society; many Muslims opened their homes to non-Muslim neighbors and friends for the breaking of the fast. Thus, the festival both heightened the sense of Muslim-ness while also promoting social relations between Muslims and non-Muslims.

The actual observance of the fast of course varied enormously, by place, time, and individual. Overall, the public complied and transgressions were in private without wider consequences. In eighteenth-century Istanbul, the neighborhood exerted social pressure but levied no punishments beyond public condemnation – usually by the imam or a person (kabadayı) who acted as its guarantor of public honor. During the nineteenth century, this began to change. Fasting in Istanbul became an issue of public order as the old system of regulating public behavior dissolved. The clothing changes of Sultan Mahmut II, which rendered visible distinctions less clear, made it easier for transgressing Muslims to slip into non-Muslim quarters of the city in order to eat or drink. Other forms of state regulation of public behavior changed as well. A government official (mühtesib) had supervised the market and kept local order. But the post was abolished in 1854 and its functions split between two sets of law and order authorities, the police and the gendarmes. These changes, together with the enactment of new legal codes, spelled confusion in the regulation of public behavior. Unsure of their position, the ulema more stridently demanded adherence to fasting and sought new rationales – at one point arguing that fasting made for good health. The civil authorities were similarly uncertain: in one quarter of the capital, the police used a bastinado on those who publicly ate or drank during Ramadan. But the typicality of such public punishments remains uncertain.

From the very highest levels, the state during the late nineteenth century sent confusing signals about the observance of Ramadan. Recall Sultan Abdülhamit II, who powerfully stressed his role as caliph, leader of the Muslim faithful. It seems at first surprising to read that officials in his Yildiz palace offices ate, drank, and smoked all through Ramadan. Such behavior derived from the state’s effort during the nineteenth century to create a new discipline and keep people at work in their offices. Hence, regulations declared fasting as incompatible with modern civilization. Work life was to go on as usual and the normal business hours for government offices would be kept. But the state behaved differently towards late nineteenth-century schools. Ramadan remained a holiday in the Muslim religious schools, the medreses, as in the past. And, when the state opened hundreds of schools of several types and at various levels – primary, secondary, medical, and military and others – it maintained Ramadan as a school holiday.

Only a tiny minority could read in what long had been and largely remained an oral Ottoman culture: in 1752, the largest library in the city of Aleppo contained only 3,000 volumes. At the time, Aleppo held thirty-one Muslim medrese schools, altogether educating perhaps hundreds of students. Among females, extremely few could read, a far smaller proportion than among males. Literacy overall increased sharply during the nineteenth century due to both private and public initiatives. On the one hand, the number of privately funded schools among Ottoman Christians and Jews rose dramatically, as did the presence of foreign-run missionary schools that catered mainly to the Greek and Armenian communities. For example, fifty private Jewish schools annually trained 9,000 students in late nineteenth-century Salonica, that contained a large Jewish population. On the other hand, a state-sponsored educational system emerged, especially in the final third of the century. A network of officially financed schools evolved at all levels, ranging from the elementary, lower secondary, and upper secondary to the professional. Estimates suggest general Muslim literacy rates equaling about 2–3 percent in the early nineteenth century and perhaps 15 percent at its end. In what remained of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the nineteenth century, nearly 5,000 state primary schools enrolled over 650,000 students. Less than 10 percent of these were girls (plates 17–19). And, in the early twentieth century, approximately 40,000 students attended the state-run secondary schools. While these are impressive increases, the numbers of students being trained paled before the educational needs of the population. Strapped Ottoman finances continued to retard the fuller emergence of the state-run school system.

Plate 17 Graduating class of the National College, Harput, 1909–1910

Raymond H. Kevorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, eds., Les Arméniens dans l’empire ottoman à laveille du genocide (Paris, 1992). With permission.

Plate 18 Students at the secondary school for girls at Emirgan, Istanbul, during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamit II

Carney E. S. Gavin et al., “Imperial self-portrait: the Ottoman Empire as revealed in the Sultan Abdul Hamid’s photograph albums,” special issue of Journal of Turkish Studies (1998), 98. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Another measure of literacy is to count the number of books and newspapers being published. Before 1840, only eleven books annually were published in Istanbul while that number had increased to 285, produced by ninety-nine printing houses, in 1908. Other statistics yield a similar impression of rapidly mounting book production and literacy. Between 1729 and 1829, c. 180 titles appeared in print while during the mere sixteen years between 1876 and 1892, the number increased to 6,357. And, remarkably, 10,601 titles appeared between 1893 and 1907. There were similarly impressive increases in the number of newspapers and journals being published: 1875 – 87; 1895 – 226; 1903 – 365, and 1911 – 548. Two of the leading newspapers in Istanbul daily printed 15,000 and 12,000 copies each during Sultan Abdülhamit II’s reign, when censorship prevailed. Circulation soared after the Young Turk Revolution and the emergence of a free press, respectively to 60,000 and 40,000 daily issues.8

Plate 19 Students at the Imperial Medical School, c. 1890

From the Sultan Abdülhamit II’s albums. Personal collection of the author.

Entries marked with a * designate recommended readings for new students of the subject.

*And, Metin. Karagöz, 3rd edn (Istanbul, n.d.).

Andrews, Walter et al., eds. and trans. Ottoman lyric poetry: an anthology (Austin, 1997).

Artan, Tülay. “Architecture as a theatre of life: profile of the eighteenth-century Bosphorus.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1989.

*Atıl, Esen. Levni and the surname. The story of an eighteenth century Ottoman festival (Istanbul, 1999).

Barnes, John Robert. An introduction to religious foundations in the Ottoman Empire (Leiden, 1986).

Behar, Cem. “Neighborhood nuptials: Islamic personal law and local customs – marriage records in a mahalle of traditional Istanbul (1864–1907),” International Journal of Middle East Studies 36, 4 (2004), 537–559.

Bierman, Irene, et al. The Ottoman city and its parts (New Rochelle, 1991).

Birge, John Kingsley. The Bektashi order of dervishes (London, 1965).

*Brown, Sarah Graham. Images of women: The portrayal of women in photography of the Middle East, 1860–1950 (London, 1988).

*Çelik, Zeyneb. The remaking of Istanbul (Seattle and London, 1989).

*Doumani, Beshara, ed. Family history in the Middle East. Household, property and gender (Albany, 2003).

Duben, Alan and Cem Behar. Istanbul households: Marriage, family and fertility 1880–1940 (Cambridge, 1991).

*Esenbel, Selcuk. “The anguish of civilized behavior: the use of western cultural forms in the everyday lives of the Meijii Japanese and the Ottoman Turks during the nineteenth century,” Japan Review, 5 (1995), 145–185.

Feldman, Walter. Music of the Ottoman court (Berlin, 1996).

Garnett, Lucy M. J. Mysticism and magic in Turkey (London, 1912).

The women of Turkey and their folk-lore, 2 vols. (London, 1890).

Gibb, E. J. W. Ottoman poetry, 6 vols. (London, 1900–1909).

Jirousek, Charlotte A.. “The transition to mass fashion dress in the later Ottoman Empire,” in Donald Quataert, ed., Consumption studies and the history of the Ottoman Empire, 1550–1922: An introduction (Albany, 2000), 201–241.

Karabaş, Seyfi and Judith Yarnall. Poems by Karacao lan: A Turkish bard (Bloomington, 1996).

lan: A Turkish bard (Bloomington, 1996).

*Keddie, Nikki, ed. Women and gender in Middle Eastern history (New Haven, 1991).

Lifchez, Raymond. The dervish lodge: Architecture, art and Sufism in Ottoman Turkey (Berkeley, 1992).

*Marcus, Abraham. The Middle East on the eve of modernity: Aleppo in the eighteenth century (New York, 1989).

*Mardin, Şerif. “Super westernization in urban life in the Ottoman Empire in the last quarter of the nineteenth century,” in Peter Benedict, Erol Tümertekin and Fatma Mansur, eds., Turkey. Geographic and social perspectives (Leiden, 1974), 403–446.

Quataert, Donald, ed., Consumption studies and the history of the Ottoman Empire, 1550–1922: An introduction (Albany, 2000).

*Quataert, Donald. “Clothing laws, state and society in the Ottoman Empire, 1720–1829,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 29, 3 (August 1997), 403–425.

*Social disintegration and popular resistance in the Ottoman Empire, 1881–1908 (New York, 1983).

Scarce, Jennifer. Women’s costume of the Near and Middle East (London, 1987).

Somel, Selçuk Akşın. The modernization of public education in the Ottoman Empire, 1839–1908 (Leiden, 2001).

Sonbol, Amira El Azhary, Women, the family, and divorce laws in Islamic history (Syracuse, 1996).

*Tunçay, Mete and Erik Zürcher, eds. Socialism and nationalism in the Ottoman Empire, 1876–1923 (London, 1994).

*Wortley Montagu, Lady Mary. The Turkish Embassy letters (reprint, London, 1994).

Zilfi, Madeline. “Elite circulation in the Ottoman Empire: great mollas of the eighteenth century,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 26, 3 (1983), 318–364.

Politics of piety: The Ottoman ulama in the post-classical age (Minneapolis, 1986).

*Women in the Ottoman Empire. Middle Eastern women in the early modern era (Leiden, 1997).

1British consul Palgrave at Trabzon; cited in Şevket Pamuk, The Ottoman Empire and European capitalism, 1820–1913 (Cambridge, 1987), 188.

2Lucy M. J. Garnett, Balkan home life (New York, 1917), 180; but written when Bulgaria was inside the Ottoman Empire.

3British consul Wilkinson at Erzurum, cited in Pamuk, The Ottoman Empire, 186.

4Julia Pardoe, Beauties of the Bosphorus (London, 1839 and 1840), 8.

5Cengiz Kırlı, “The struggle over space: coffeehouses of Ottoman Istanbul, 1780–1840,” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation (Binghamton University, 2000).

6Seyfi Karabaş and Judith Yarnall, Poems by Karacao lan: A Turkish bard (Bloomington, 1996).

lan: A Turkish bard (Bloomington, 1996).

7The material on Ramadan is drawn from: François Georgeon, “Le ramadan à Istanbul,” in F. Georgeon and P. Dumont, Vivre dans l’empire Ottoman. Sociabilités et relations inter-communautaires (xviie-xxe siècles) (Paris, 1997), 31–113.

8Robert Mantran, Histoire de l’Empire ottoman (Paris, 1989), 556–557.