Catalogue

[1989–2011]

.jpg)

1

2

Catalogue

[1989–2011]

.jpg)

1

2

1 — Untitled, 1989

2 — Punto di vista mobile, 1989

In the late 1980s, as Maurizio Cattelan was transitioning away from furniture making and toward a more artistic practice, he created several objects that straddled art and design. He was exploring the possibilities of art making and beginning to figure out what it means to be an artist. During this time, he collected materials from junkyards, forming them into sculptures that maintained references to his design work but divorced the found objects from their function. For Untitled (1989), he welded discarded bicycle parts into a spare, anthropomorphic figure. Punto di vista mobile (Mobile point of view, 1989) best evokes the transitional spirit of this period, alluding to the ways in which his outlook on the arts was changing. The work, which comprises two footrests, formerly used to guide foot placement in a train toilet, is intended to afford anyone who steps onto it a slight shift in perspective. By altering the viewer’s sight lines in this small way, the new point of view becomes a gesture both literal and figurative.

ST

3

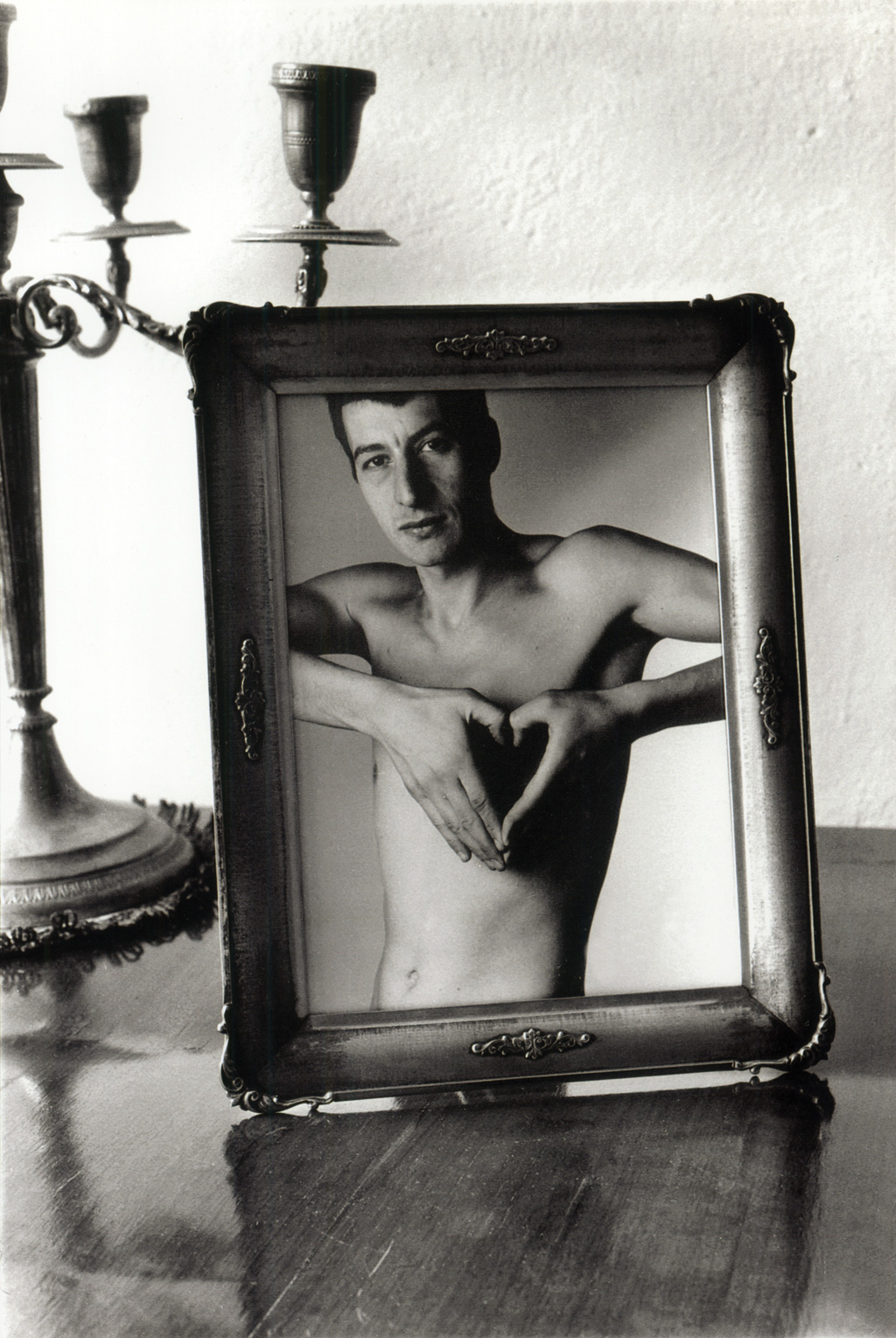

3 — Lessico familiare, 1989

Lessico familiare (Family syntax, 1989), a framed photograph that derives from a site-specific project realized at the San Sabastiano oratory in Forlì in 1989, could be considered Cattelan’s first project as an artist. While his earlier furniture designs of the late 1980s playfully reimagined standard home furnishings, the original installation of Lessico familiare evoked a surprisingly conventional domestic scene. On an ornate wooden side table, the artist assembled a diorama of Italian middle-class taste, at the center of which he placed an ornamented silver frame holding a black-and-white self-portrait. With its dramatic interplay of light and shadow, the photograph depicts a shirtless Cattelan holding his hands together over his chest so that his fingers outline the shape of a heart.

Cattelan, the son of a truck driver and a cleaner, has appropriated the trappings of economic and social success, but rendered their meanings ambiguous. Italian families commonly reserve similarly ornate silver frames for wedding photographs. Yet Cattelan’s depiction of himself, half-naked and alone, hardly seems to celebrate matrimonial love, even if his sleepy-eyed pose suggests romance.

WS

4

4 — Grammatica quotidiana, 1989

Grammatica quotidiana (Daily grammar, 1989) at first appears to be the kind of tear-away calendar that restaurants distribute as advertisements. However, Cattelan has fundamentally altered its function by printing the word oggi (Italian for today) on every page. His intervention guarantees the calendar’s accuracy, always and forever, but he has also eliminated the possibility of it registering chronological progression. Day after day, the repetition of oggi suggests a continuous present isolated from history and separated from any hope for the future.

In this sense, Grammatica quotidiana responds to 1960s and ’70s Conceptual practices in which the form of a calendar was used to question the chronological experience of time. For instance, On Kawara has completed thousands of paintings that record the date on which he painted them for his Today Series (1966– ). Cattelan’s work similarly investigates the flow and repetition of time, but its casual efficiency could be interpreted as mocking Kawara’s relentless commitment to his work and the sublime scope of his practice. The kitsch seascapes and landscapes that adorn the various versions of Grammatica quotidiana also undermine Conceptual art’s austere visual vocabulary while pointing to the calendar’s original raison d’être, advertising a bakery in Forlì, where Cattelan lived in the late 1980s. In fact, the work can also read as a gimmicky tagline: the Panificio Modernissimo is the place to go for one’s daily bread.

WS

5

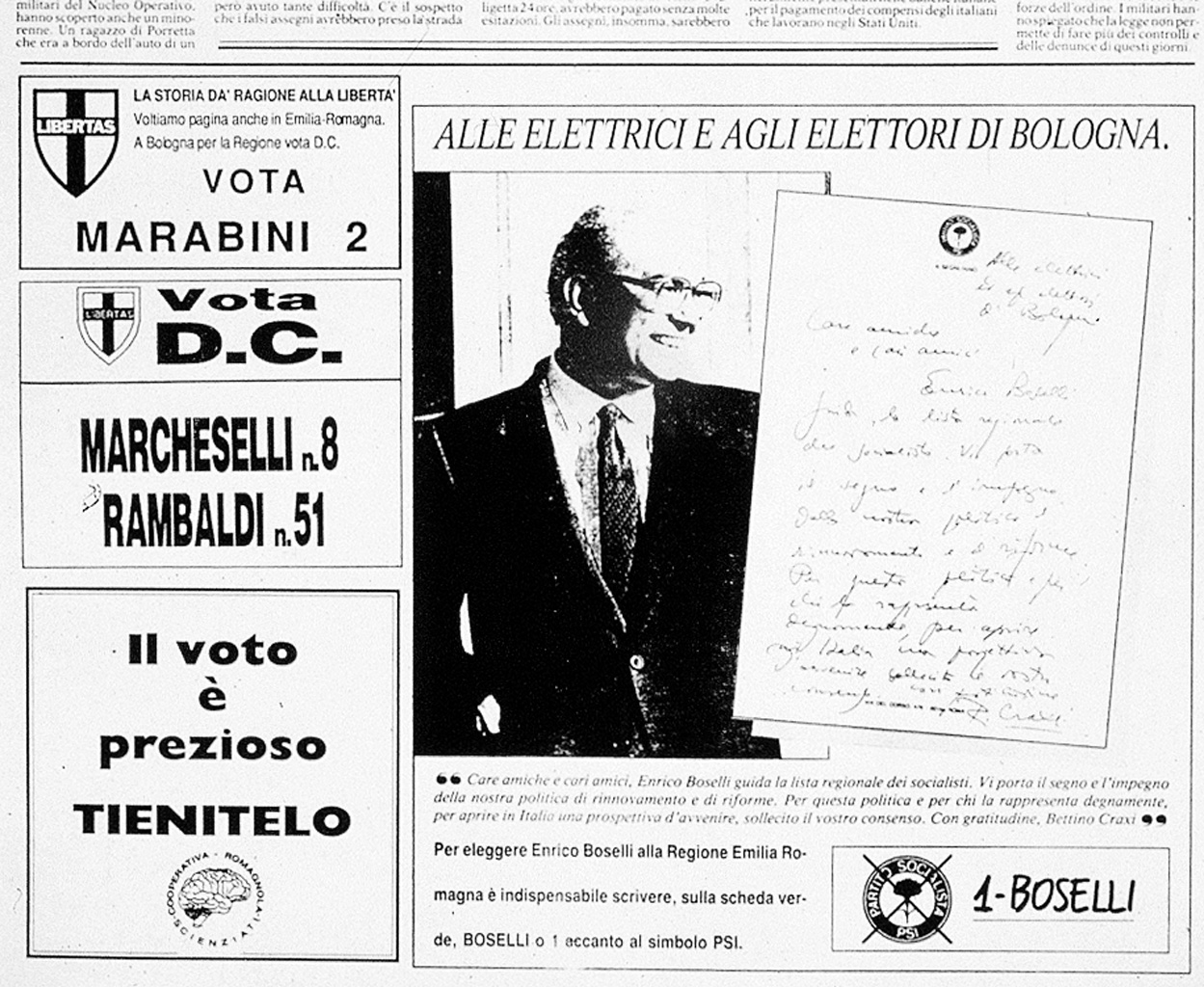

5 — Campagna elettorale, 1989

In 1989, under the guise of the Cooperativa Romagnola Scienziati (Romagna scientists cooperative), Cattelan placed an ad in La Repubblica alongside several campaign advertisements. While the other ads encouraged voters to select various candidates, Cattelan’s read simply “Il voto è prezioso/TIENITELO” (Your vote is precious/KEEP IT). Reversing the common logic that the preciousness of one’s vote compels one not to waste it and cast it wisely, Cattelan presented a counterintuitive call to inaction. The ad humorously questioned the value of a vote by suggesting that a citizen might benefit from holding onto it, even though this commodity only has currency within the context of an election. The placement of the ad in a daily newspaper references the conceptual gestures of Joseph Kosuth, who, in the late 1960s, used the newspaper ad as a medium out of an interest in immateriality. Kosuth took out ad space in four publications, inserting one of the four thesaurus definitions of the word “existence” in each. Kosuth was interested in activating spaces for social engagement, but in Campagna elettorale (Electoral campaign, 1989), Cattelan sought the opposite effect by encouraging others to abstain from political participation.

ST

6

6 — Torno subito, 1989

In 1989 Cattelan was invited to present a solo exhibition at the Galleria Neon, Bologna. Although representing a longed-for breakthrough in his career, this momentous opportunity plunged the young artist into paroxysms of indecision, self-doubt, and crippling performance anxiety. Unhappy with the idea of showing examples from his existing body of work but unable to find a compelling new concept for his debut show, Cattelan established a strategy of evasion that would become a recurring trope in his oeuvre. Seeking to avoid both the perils of failed promise and the onerous burden of production, his solution was to avoid public exposure altogether by constructing a simple escape route. When visitors arrived at the gallery, they were greeted by a locked door and an unassuming Plexiglas sign engraved with the phrase Torno subito (Be back soon), as if the proprietor had popped out to run a quick errand. This tantalizing promise was an empty one, however. The “absent” gallery custodian never returned, and the space remained empty for the entire run of the exhibition, isolating the visitor in a moment of perpetually deferred revelation.

KB

7

7 — Non si accettano testimoni di Geova, 1989

After being approached at home by members of the Jehovah’s Witness faith, a group that frequently engages in door-to-door evangelism, one of Cattelan’s neighbors placed a note on his door that read “Non si accettano testimoni di Geova” (We don’t accept Jehovah’s Witnesses). Interested in the ways in which both the desire to convert others and the note rejecting such efforts represent intolerance for other faiths, Cattelan decided to take this note and have it engraved in brass. Resembling “No Soliciting” signs that are often placed outside homes to discourage salespeople, the work also evokes the type of placards that have marked various eras of racism throughout history, such as “No Irish Need Apply.” Arranged with several stolen plaques from various local businesses, such as doctors’ and lawyers’ offices, the resultant grouping seems to imply that all the professionals in a building have decided not to offer their services to this specific religious group. With this gesture, the original desire to deflect residential solicitation has transformed into broader social discrimination as the sign moves from private to public property.

ST

8

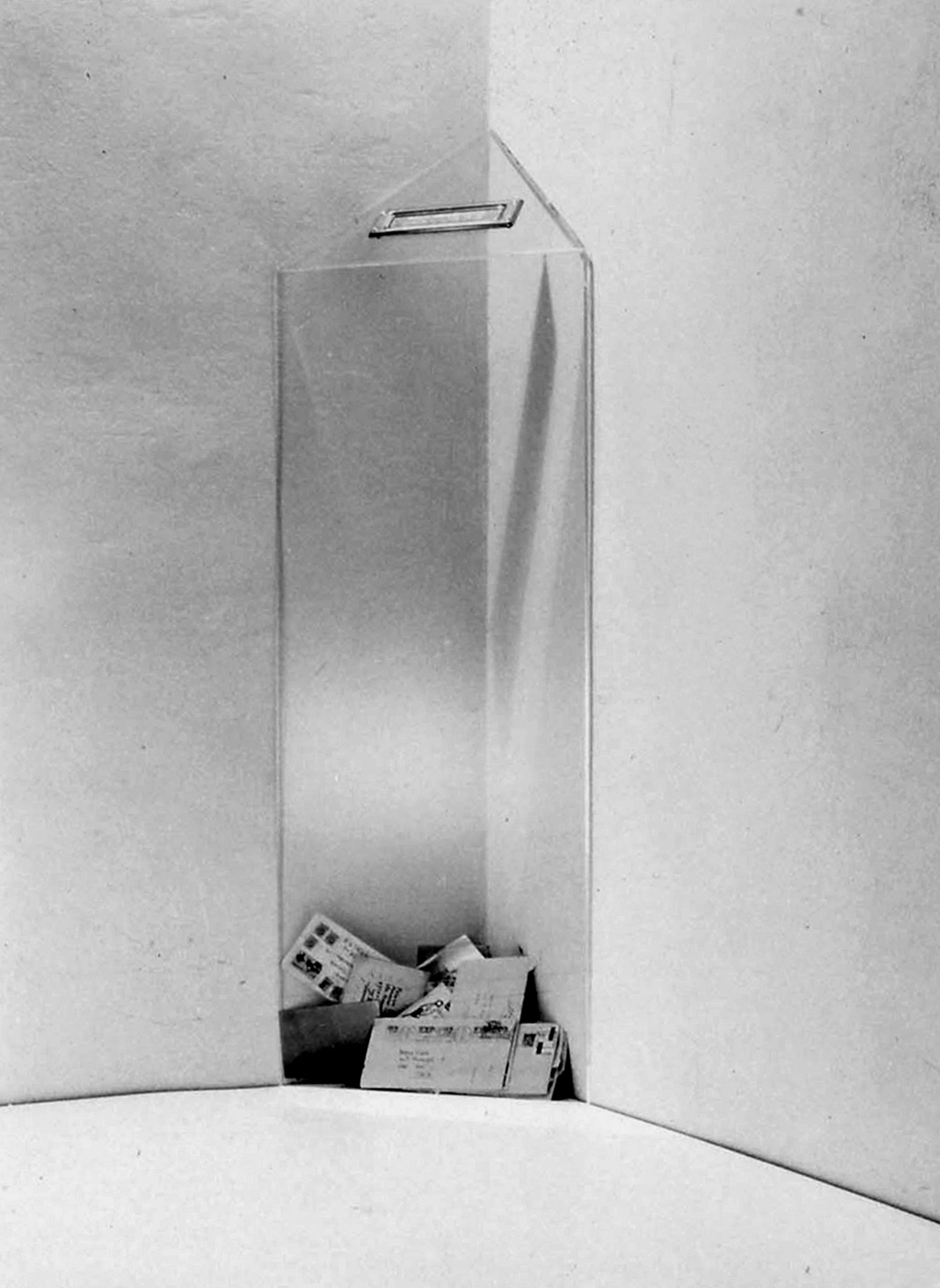

8 — Angolo dei ricordi, 1989

— Angolo dei Ricordi, 1991

Angolo dei ricordi (1989 and 1991), which can be translated as “memory corner” or “memento corner,” is a simple Plexiglas vessel with a brass letterbox slot at the top, containing an assortment of postcards and letters. Due to the box’s transparency, the contents are partially legible, but because the letters are impossible to retrieve once deposited, they are frustratingly inaccessible to the curious reader. This eccentric wedge-shaped structure, which was originally conceived for the corner of Cattelan’s apartment, was designed as a repository for correspondence sent to his girlfriend by her former lovers. The secure entrapment of these documents neutralized some of their potency, but they remained an indelible presence in the couple’s shared home, a poignant metaphor for the inevitable and at times oppressive traces of past experiences in a new relationship. In addition to its emotional resonance, Cattelan was interested in the work’s ability to activate the liminal space of the corner—a traditional site of marginalization and childhood punishment that has provided rich terrain for iconic Minimalist and Post-Minimalist sculptural interventions. Cattelan created a second version of the work in 1991, this time using his own mail.

KB

9

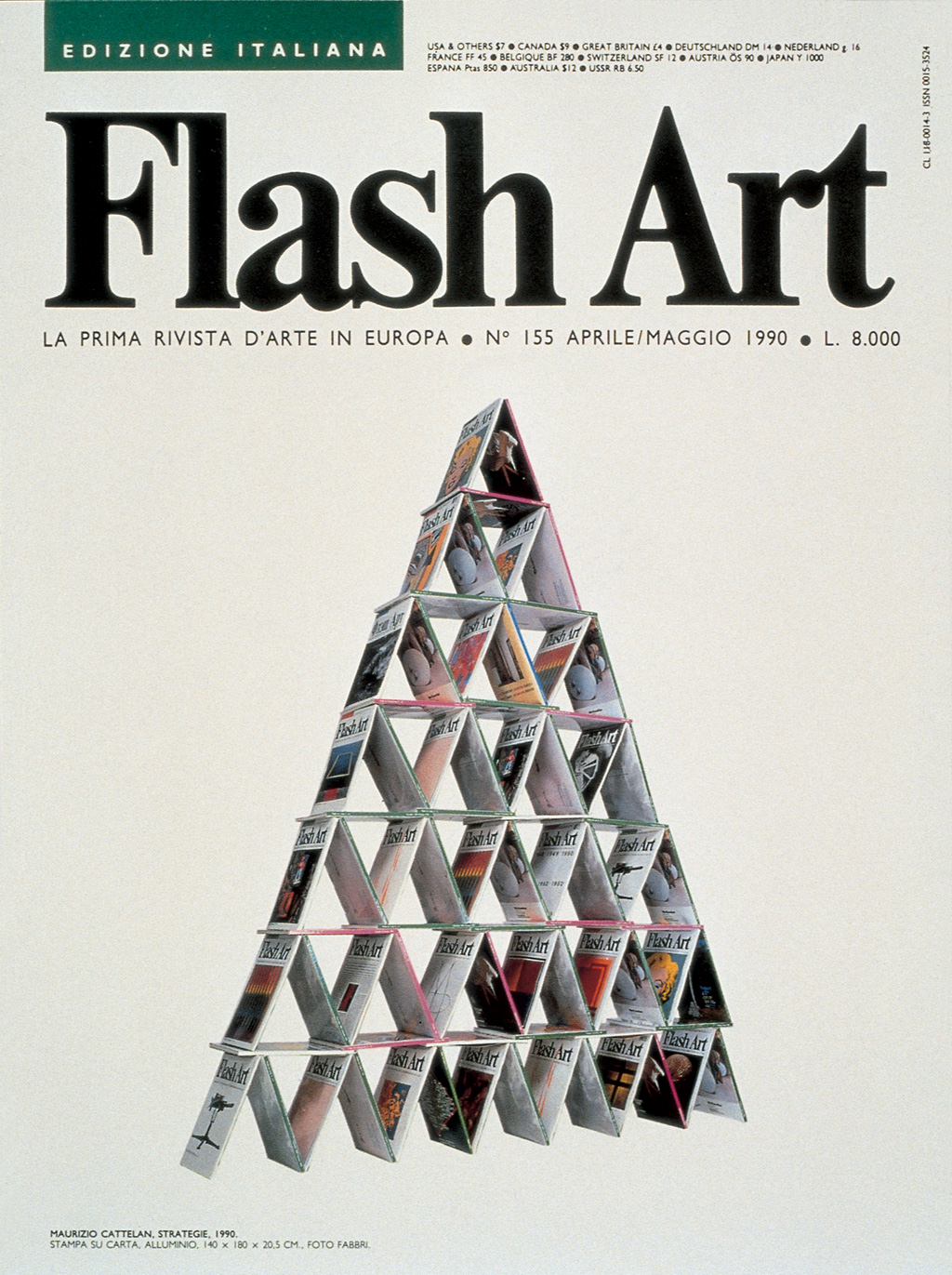

— Strategies, 1990

9 — Strategies, 1990

Strategies (1990) is a pyramidal structure fabricated from aluminum sheets and faced with multiple issues of the contemporary art magazine Flash Art. Beyond its status as an object, the work also circulates as a reproducible image. Cattelan designed a counterfeit cover of Flash Art featuring a photograph of Strategies. He even purchased unbound copies of the magazine directly from the printer and distributed them, with his cover, to galleries around Milan.

Strategies appears in photographs as an unstable house of cards. The visual metaphor alludes to the tricky balance that publications like Flash Art have to maintain. Commercial galleries rely on positive reviews from supposedly disinterested publications to bolster sales, while the latter depend on the former for ad revenue. Rather than bemoaning such open secrets as conflicts of interest, Cattelan has consistently used these inherent contradictions between commerce and intellectual activity as sources of creative tension. By hijacking a magazine whose credibility is real and valuable, Cattelan not only offered a possible critique of its role in a market-driven art system, he also found a shortcut to having his work featured on the cover of the most influential art magazine in Italy.

WS

.jpg)

10

10 — Untitled, 1991

Originally titled Repetita iuvant, Untitled (1991) recalls the repetitive writing exercises that teachers frequently assign to students as punishments. “Fighting in class is dangerous” has been carefully spelled out again and again in Italian on sheets of notebook paper pinned to a wall. Equally careful and persistent are the red ink marks that correct a single preposition in each sentence. The otherwise minor change from “in” to “di” shifts the admonishment against horsing around to a more consequential warning: “Class struggle is dangerous.” In interviews Cattelan has discussed how his work has been informed by the difficulties he experienced as a student, especially a failed writing test that Cattelan remembers as a particularly painful incident. More than a meditation on any individual’s education, however, the work conflates classroom disruptions with political resistance, treating the school system as a microcosm of the social tensions that persist in the adult world. Indeed, it suggests that the lesson taught through rote repetition may also lay the foundation for a docile citizenry.

WS

11

11 — Edizioni dell’obbligo, 1991

Working with a teacher from Ravenna, Cattelan collected workbooks from her class of elementary-school children and published the handwritten exercises in softcover versions under the imprint Edizioni dell’obbligo (Obligatory editions). He presented these books at the Castello di Belgioioso book fair, where he set up a booth and identified himself as a publisher. Each volume features a drawing on the cover, apparently by the child author. In contrast to the illustrations’ naïve creativity, the titles convey deadpan contempt for school and resistance to the act of writing. Stefano Tutulo’s “Scrivere non è il mio mestiere” (Writing is not my job) and Erika Bongiovanni’s “Orrori ed errori” (Horrors and errors), among others, reflect disdain for the repetitive coursework in the books they were required to create.

Cattelan’s publishing project is part of a series of works that examine the systematic constraints on thought and action inherent in education. While the artist remembers his time in school as particularly fraught by such restrictions, his publishing venture raises questions about authorship that recur frequently in his practice. With Edizioni dell’obbligo (1991), Cattelan abandons the traditional role of the artist as creator to work instead as a publisher and editor. His books provide only a new context for preexisting content—children’s drawings and schoolwork—that would be considered neither art nor literature in any other setting. Their exhibition further critiques clichéd conceptions of writing as a creative process by showcasing the work of “authors” who labored against their will to meet the arbitrary demands of authority figures.

WS

12

— Cesena 47 – A.C. Forniture Sud 12, 1991 [fig. 11]

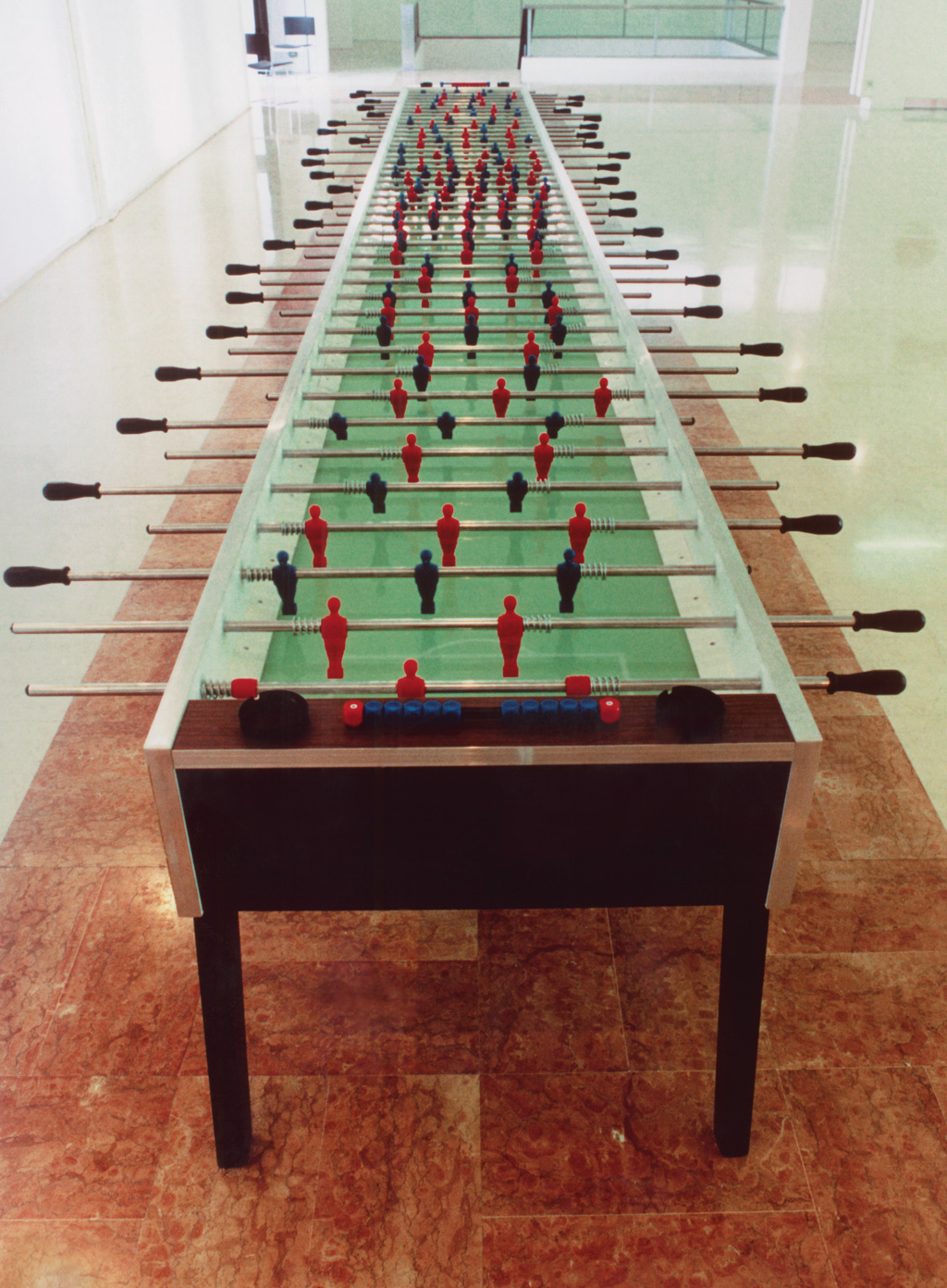

12 — Stadium, 1991

In the early 1990s, Cattelan founded a soccer team made up of North African immigrants, which competed in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy. In artworks and performances with the team, Cattelan alluded to contemporary racial tensions and xenophobia toward immigrants while exploiting the institution of the European soccer team as both a capitalist money-generator and vehicle for national aspirations. A.C. Forniture Sud (Southern Suppliers FC [Football Club]) was sponsored by a fictional transport company called Rauss (derived from a Nazi slogan that means “get out”). In 1991, Cattelan infiltrated Bologna Arte Fiera, an annual fair, with his Stand abusivo (Illegal stand), which he used as an opportunity to promote A.C. Forniture Sud memorabilia.

That same year, Cattelan produced Stadium, a foosball table that accommodates eleven players on each side, and orchestrated a live foosball match at Galleria comunale d’arte moderna, Bologna, pitting his team against an all-white group of northern Italians. Athletic, uniformed players hunched over the long, narrow tabletop provided a comical sight, but the makeup of the teams and the manipulation of the wooden figures suggested serious world politics. Now shown as a stand-alone sculpture with several balls on the table at once, the viewer is invited to interact with Stadium, retaining the original project’s spirit of communal play.

DK

.jpg)

13

13 — Untitled, 1991

In 1991, unable or unwilling to produce a new work for Briefing, a group show at Galleria Luciano Inga-Pin, Milan, Cattelan instead submitted a framed police report detailing the theft of an “invisible” artwork from his girlfriend’s car, dated the night before the opening. The report notes the alleged robbery’s date and time as well as the car’s make and license plate. Clearly stating that the work was meant for an exhibition in Milan and was of emotional value, it is neatly typed, dutifully stamped, and signed by all requisite parties. Yet, this document of an event registers less as a dubious robbery and more as a bureaucratic exchange of information. By exhibiting the paperwork as a substitute for the invisible stolen object, Cattelan turns a Conceptual art maxim as enunciated by Lawrence Weiner—“The work need not be built”—into an alibi. Moreover, rather than conjuring the immaterial by playing on the viewer’s imagination or claiming an idea as material, Cattelan inserts a whimsical idea into a nonart system through an encounter with municipal functionaries. He then reintroduces that idea to the art world, where invisible artwork is not as absurd as convoluted bureaucratic paperwork, and the viewer is left wondering who is playing the joke on whom.

DK

.jpg)

14

— -76.000.000, 1992

— -157.000.000, 1992

14 — -74.400.000, 1996

In a 1992 group exhibition at the Galleria d’arte moderna e contemporanea, Accademia Carrara, in Bergamo, Italy, Cattelan exhibited for the first time two safes from which burglars had stolen tens of millions of lire. Each of these works is titled with a minus sign and a number denoting the amount of money that was removed during the robbery. Though Cattelan has denied that they directly challenge art-world conventions, his cracked safes assert the uncomfortable connection between readymade art and common theft. Still bearing the cuts and scrapes of the thieves’ tools, the safes effectively equate the gallery with a crime scene.

WS

15

15 — Oblomov Foundation, 1992 [fig. 8]

The title character of Ivan Goncharov’s 1859 novel Oblomov is a Russian nobleman who fails to muster the initiative to accomplish his ambitious dreams. The novel’s first third famously narrates his struggles simply to get out of bed one morning. Cattelan’s Oblomov Foundation (1992) institutionalizes this spirit by mimicking, paradoxically, the relentless fund-raising activities that sustain the art world. Cattelan asked one hundred donors for $100 each to fund a scholarship. While most granting organizations require at least some evidence of work from the artists they support, the foundation’s $10,000 award came with a single caveat: the recipient must not exhibit work for a year.

Artists who accepted the money would have risked their careers by essentially dropping out of the art world—a gamble that no one was willing to take. While the foundation failed to distribute its funds as planned, Cattelan still recognized the donors’ generosity. He had their names engraved on a glass plaque, reminiscent of those in museum lobbies, and surreptitiously affixed it to the facade of the Accademia di belle arti di Brera, Milan, where it remained on view for a year before academy officials had it removed. With the award unclaimed, Cattelan reconfigured the scholarship into a travel grant to finance his own career-boosting move from Italy to the United States.

WS

16

16 — Una Domenica a Rivara, 1992 [fig. 6]

Cattelan originally installed Una Domenica a Rivara (A Sunday in Rivara, 1992) at the Castello di Rivara, Centro d’arte contemporanea, a prestigious venue located near Turin, that invited him to show at what was then an early stage in his career. Cattelan’s intuitive response to his anxiety about the exhibition was to devise a literal and symbolic escape. A series of bed sheets knotted together hanging outside a window is a familiar symbol of outlaw freedom; in movies, prisoners and boarding-school students construct similar devices to liberate themselves from institutions. By employing such a well-worn cliché, Una Domenica a Rivara would seem to cast the museum as an authoritarian establishment from which the artist might have to abscond. More than a simple fantasy of flight, however, the work points to the ambivalence with which Cattelan has since embraced art institutions. While offering a dramatic exit route from the gallery, the knotted sheets ultimately remained tethered to it. After all, only the legitimacy conferred by institutions like the Castello di Rivara allow the piece to be recognized as a performative work of art rather than an empty gesture.

WS

17

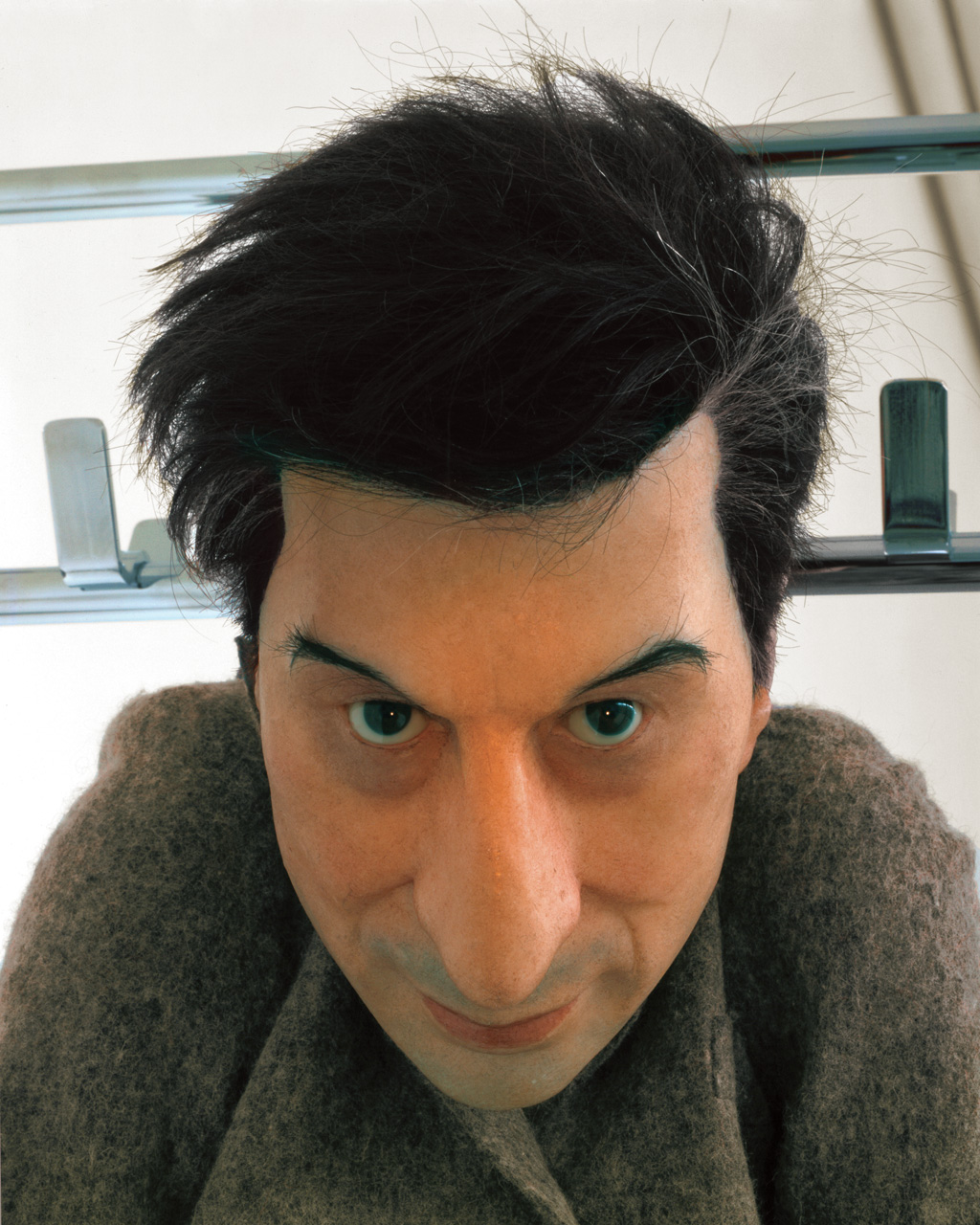

— Super Us, 1992

17 — Super Us, 1998

An early take on the self-portrait, Super Us (1992) establishes Cattelan’s irreverent approach to the genre. The work, which he has remade a number of times, consists of multiple portraits of Cattelan produced by police-composite-sketch artists and based on descriptions submitted by friends and acquaintances. The results are a record of the varying impressions that he had made on those who provided the descriptions, each an illustration of a relationship as much as an image of the artist. Beyond portraying the self as a network of other people’s appraisals, Cattelan’s goal was also to visualize the way in which our perceptions of others can never form a complete picture. In the aggregate, only the most exaggerated features recur, as if ultimately we picture each other as cartoons.

The acetate sheets are displayed unframed and tacked up on the wall in an unorganized swarm, evoking a bulletin board of most wanted criminals. Though Cattelan denies casting himself as a police suspect, the imagery underscores his elusive public identity and habit of escaping his appointments, whether by sending others in his place to interviews or producing last-minute stunts as work for commissioned exhibitions.

DK

18

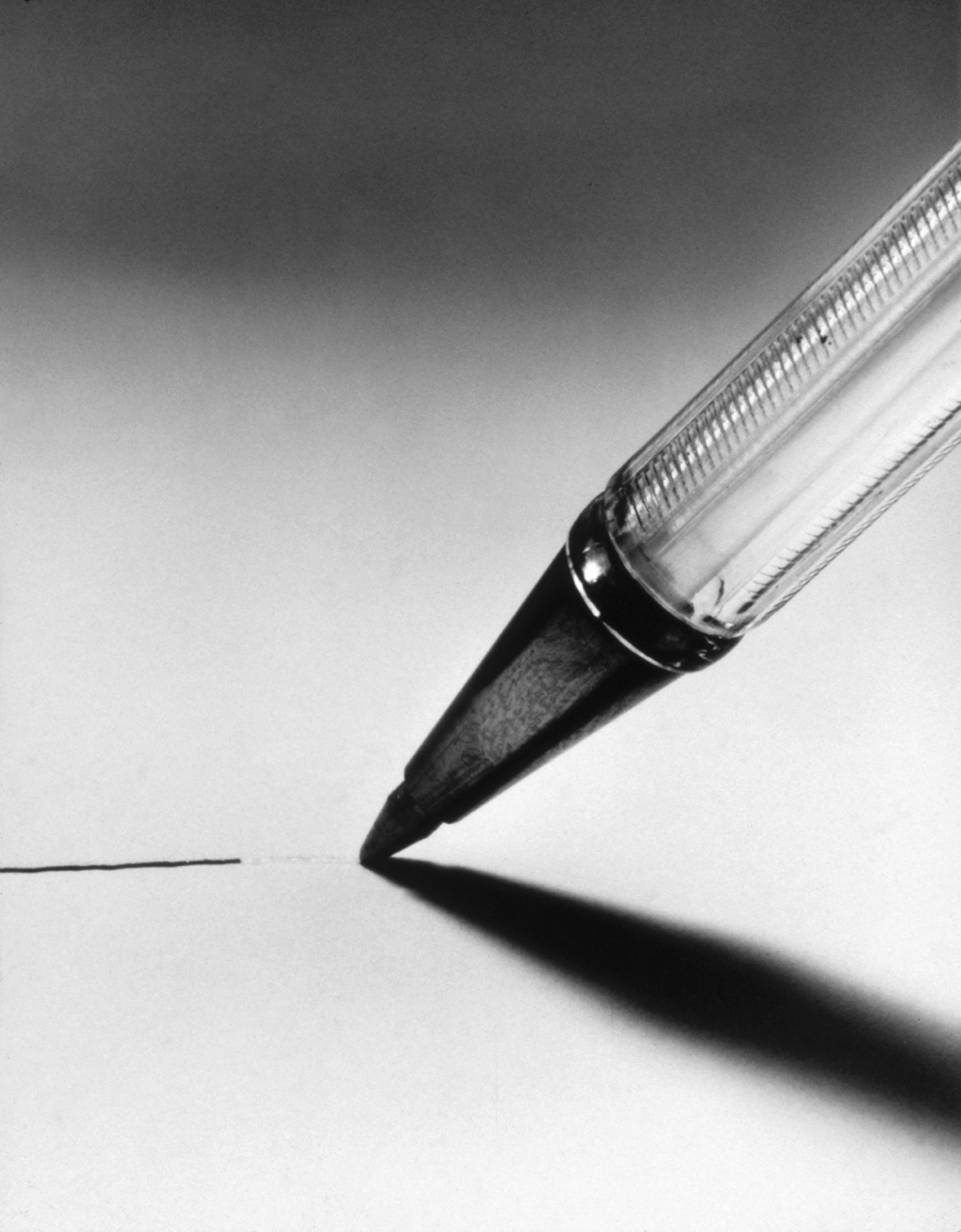

18 — Esaurita, 1992

The impetus for Esaurita (Depleted, 1992) came when a cheap Bic pen that Cattelan was using ran out of ink. Cattelan began to view the pen as an allegory for the artist who may eventually run out of ideas. Curious about the art world’s potential response to such creative collapse, Cattelan sold the broken pen to a collector in a bet with his gallerist who thought it would not be possible to sell. He also documented Esaurita in a black-and-white photograph, in which an abruptly discontinued line dramatizes the pen’s inability to function. The spare composition, close-up view, and looming shadow bestow a feeling of drama and consequence on the otherwise mundane scene, endowing the pen with a monumental presence.

Although its subject matter belongs to the present, Esaurita recalls a long tradition of melancholy imagery in art. Similar emblems include the disused scientific instruments scattered about Albrecht Dürer’s print Melencolia I (1514) and even the ruined churches and palaces that fascinated Romantic painters. With Esaurita, Cattelan updates these meditations on loss for a society comfortable with planned obsolescence. Here the contemplative mood fostered by earlier melancholy imagery is mitigated by the knowledge that the pen is disposable and easily replaced.

WS

19

20

19 — Tarzan & Jane, 1993

20 — Errotin, le vrai lapin, 1995 [fig. 26]

— Untitled, 1999 [fig. 25]

On multiple occasions Cattelan has directly implicated his gallery representatives in his work. For the first of these projects, Tarzan & Jane (1993), he had the owners of Galleria Raucci/Santamaria, Naples, dress up in lion costumes for the entire run of his solo exhibition. Next, he collaborated with a cartoonist to develop a costume for his Parisian dealer Emmanuel Perrotin, designed to reflect his playboy persona. In Errotin, le vrai lapin (Errotin, the true rabbit, 1995), Perrotin wore a pink rabbit costume that resembled an oversized penis and testicles in the gallery every day of Cattelan’s show. For Untitled (1999), which was originally titled A Perfect Day, Milan gallerist Massimo De Carlo was affixed to the gallery wall with duct tape during the exhibition’s two-hour opening. Though amusing for the event’s attendees, the situation took a more serious turn later in the night when De Carlo was rushed to the hospital after suffering from a shortage of oxygen.

In these works, the gallerists, whose usual role is to promote the artist and sell his art, embodied the intervention, a gesture that collapsed the layers of the market by incorporating the middleman. By putting his dealers in awkward and often demeaning positions, Cattelan also altered the power dynamic between gallerist and artist.

ST

-16-36-21.jpg)

21

21 — Untitled, 1993

Through the run of Cattelan’s first solo exhibition at Galleria Massimo De Carlo, Milan, bricks walled off the gallery’s door, barring entry. Intrepid visitors intent on seeing inside discovered that from a particular vantage point through a window, they could view a mechanical teddy bear cycling back and forth on a tightrope strung between two walls of the gallery. The lone figure, as if absorbed in his repetitious performance, oblivious to his scorned potential audience, created a memorable image that was humorous yet laced with sadness, suggesting an artist’s self-imposed isolation. Untitled (1993) is Cattelan’s first work using an animal subject, and this blend of absurd comedy and melancholy, along with an animal as the artist’s surrogate, became hallmarks of works to follow. Beyond the physical tableau, the work’s meaning hinges on the architectural intervention. By denying entry to the gallery, Cattelan dramatically altered the space’s function, halting the gallery’s social and monetary transactions and realizing an inaccessibility that could be a metaphor for the unattainable status too often associated with contemporary art.

DK

22

22 — Working Is a Bad Job, 1993

For the 1993 Venice Biennale, Cattelan was afforded a centrally located gallery in the Aperto, a sprawling exhibition organized by a team of influential curators. Cattelan’s project, Working Is a Bad Job (1993), capitalized on the location’s prominence while appearing to mock the show’s entire premise. Rather than create a new piece himself, Cattelan rented his space to an advertising firm, which installed a large billboard for a new brand of perfume.

Long a forum for collectors to browse the latest work and speculate on new talent, the lines between commerce and culture at the biennale were already blurred. While seemingly out of place among the paintings and sculptures on view, Cattelan’s piece carried the possible critical subtext that the Aperto was an all-too-appropriate venue for overt marketing. In his account of the project, however, Cattelan emphasizes its contradictory mix of publicity and self-effacement. By outsourcing aesthetic choices to an advertising agency, Cattelan sidestepped the anxiety he felt about having to fill the space with his work, but at the cost, it might seem, of his artistic authority.

WS

.jpg)

23

23 — Untitled, 1996 (from the Zorro Paintings, 1993–99) [fig. 28]

The first time film audiences witnessed Zorro carve his famous “Z” mark, he did it with three quick rapier swipes to a corrupt army officer’s rear end. Douglas Fairbanks, who starred as the black-clad avenger in the original 1920 film, played the scene for comedy, even pausing mid-swordfight to laugh at his humiliated opponent. While Zorro’s famous initial subsequently became a noble symbol of the hero’s identity, it was thus initially an irreverent affront to authority. Cattelan channels this genealogy of the pop-culture icon in a series of slashed monochromatic canvases that evoke the mark of Zorro in order to deflate some of the twentieth century’s most high-minded artworks.

Monochromatic painting epitomizes an impulse in modern art toward austerity and inaccessibility. Cattelan’s Zorro paintings, which were created between 1993 and 1999 in a range of colors and sizes, take aim in particular at Lucio Fontana, an Italian artist who investigated the aesthetic and philosophical implications of radically simplified forms. With his Concetti spaziali (Spatial concepts) series (1949–60), Fontana hoped to escape the limitations of a flat monochromatic canvas by literally cutting through its surface. Fontana described his slash as a liberating gesture that could open painting into an exploration of infinite space. Mocking these claims to transcendence through art, Cattelan grounds the spatial concept in popular culture, where Fontana’s signature formal device must double as Zorro’s signature.

WS

24

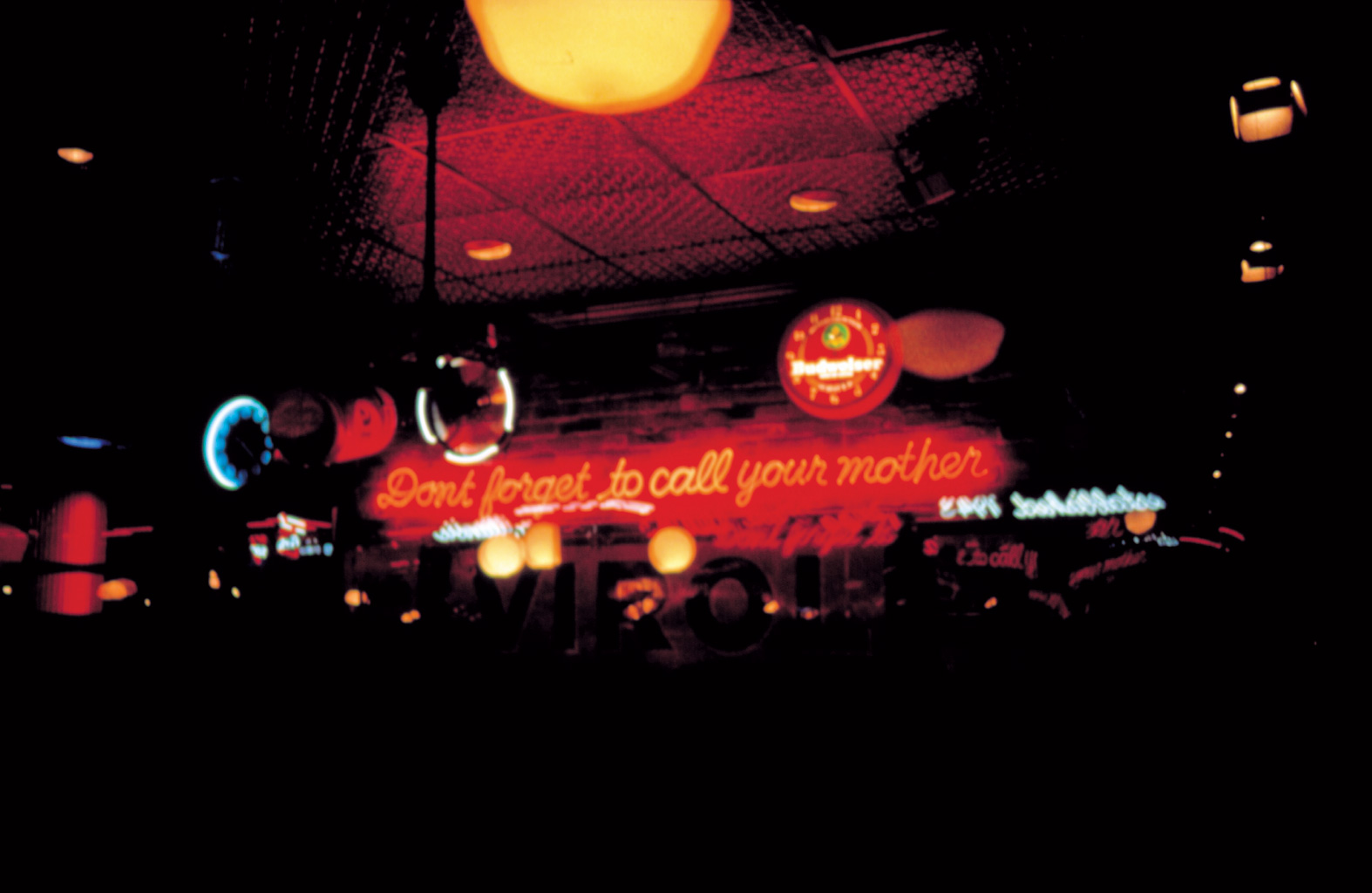

24 — Catttelan, 1994 [fig. 10]

For Catttelan (1994), the artist wrote his surname with a pen, inserting a third letter t into the traditional spelling, and had the resulting design enlarged and fabricated in neon. This transformed signature was then installed in Laure Genillard Gallery, London, the middle t centered in a corner. This positioning invokes an inevitable association with Minimalism and its preoccupation with the possibilities contained within the space of the corner, particularly the work of Dan Flavin, who used fluorescent lights to explore the relationships among light, space, and vision, and often similarly activated corners. The use of neon resonates closely with the work of Arte Povera artist Mario Merz and Post-Minimalist artist Bruce Nauman, who both deployed the material to form words and phrases.

The three lowercase letter t’s easily read as crosses, and arranged with the tallest one in the center, they allude to Jesus’s crucifixion as described in Luke 23. In this account, two thieves hung beside Christ on Calvary: one who mocked Jesus along with other bystanders, and another who defended him and repented his own sins. These crosses on either side of Christ have come to represent the dichotomy of the damned and the redeemed. By gathering these shapes in the lettering of his name, Cattelan perhaps acknowledges the presence of both within himself.

ST

25

25 — I Found My Love in Portofino, 1994

— Il Bel Paese, 1994 [fig. 12]

In I Found My Love in Portofino (1994) and Il Bel paese (1994), Cattelan grapples with the subject of Italy through one of its most mundane products: Bel Paese cheese. Meaning “beautiful country,” the concept of “bel paese” represents a quaint and bucolic view of his homeland that pervades international perception despite the contemporary political conflicts that Cattelan has addressed in other mid-1990s works. In I Found My Love in Portofino, black mice nibble at a round of this cheese, gnawing away the map of Italy on the product’s iconic label. For the exhibition Soggetto-Soggetto: Una nuova relazione nell’arte di oggi (1994) at Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin, Cattelan covered the lobby with a large circular carpet, which resembled an enlarged version of the label. The carpet, and consequently its image of Italy, eventually became soiled and dingy from extensive foot traffic. Il Bel paese is perhaps a commentary on the large Italian tourism industry and the hordes that similarly wear down the country’s treasures. There is much to be celebrated about Italy’s rich history, beautiful landscapes, fine art, and excellent cuisine, but in both works, Cattelan indicts this perfect (and widely marketed) image by allowing its representation to become slowly defiled.

ST

26

— Lullaby, 1994 [fig. 10]

26 — Lullaby, 1994

In Italy, the mid-1990s were a convulsive political period defined by the nationwide Mani Pulite (clean hands) campaign that investigated widespread political corruption; in reaction, a wave of Mafia-related terrorism swept the nation. In Milan in 1993, one bomb killed five people and nearly leveled the art center PAC Padiglione d’arte contemporanea. Cattelan saw the event as a poignant confrontation between forces of progress and destruction. As he was preparing for his first solo show outside Italy, he questioned how to export Italian culture during such turmoil. In a typically bold response, he created two sculptures titled Lullaby (1994), both made of rubble from the bomb site. For his solo exhibition at the Laure Genillard Gallery, London, he showed the rubble encased in a blue carryall bag, a typical mode of transport for demolition crews that he compared to a hospital laundry bag. Simultaneously, for a group show at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, the rubble was wrapped in plastic and stacked on wooden pallets. Both displays highlighted the transport element to emphasize the material as debris. The sculptures’ packaging also shrouded the controversial contents, respectfully or even mournfully covering the remains. The title, Lullaby, is an incongruous word to call detritus from a terrorist attack, yet Cattelan points out the hypocrisy of the viewer who balks at such a combination—lullabies and terrorism invariably coexist in the world, and neither prevents the other.

DK

.jpg)

27

.jpg)

28

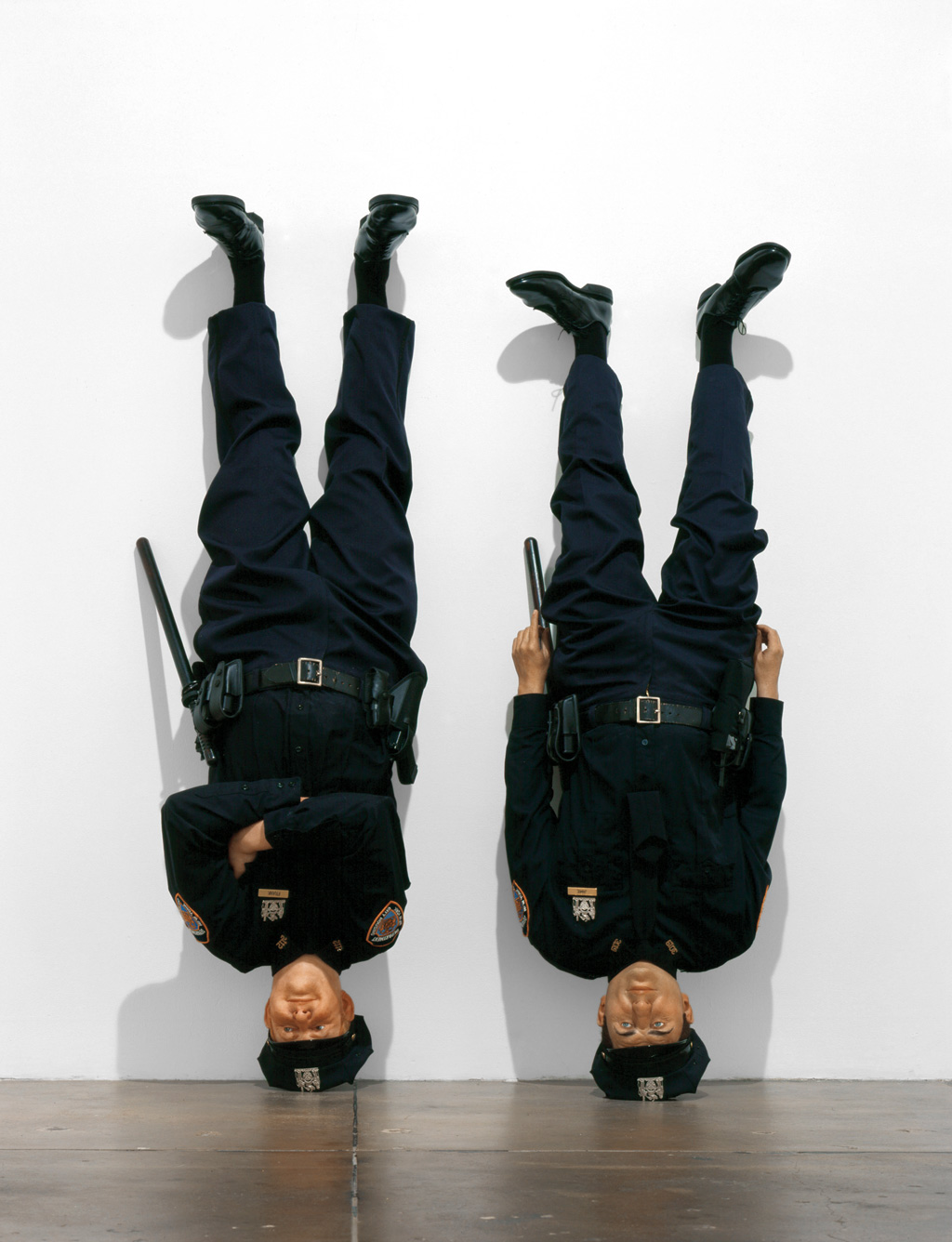

— Warning! Enter at your own risk. Do not touch, do not feed, no smoking, no photographs, no dogs, thank you, 1994 [fig. 4]

27 — Untitled, 2002

28 — Untitled, 2004

When Cattelan exhibited a live donkey for his 1994 New York gallery debut, at Daniel Newburg Gallery, he claimed to identify with the animal’s reputation as a buffoon. While the gallery’s landlord closed the exhibition almost immediately because of noise complaints, Cattelan revisited the image of the donkey nearly a decade later in a series of untitled taxidermy works.

For a 2002 sculpture, Cattelan suspended a preserved donkey via a harness connected to an overloaded cart, giving three-dimensional form to a well-known image. A photograph of a donkey in the same position, taken somewhere in Asia, is an early Internet meme that went viral in the late 1990s. As much as Cattelan might see himself in the donkey’s ridiculous situation, the elaborate sculpture also draws on a readymade image that still circulates online.

Seated on its hindquarters with splayed back legs, a second donkey, made in 2004, seems to invite sympathy with its cartoonlike posture and sad-eyed stare. Appearing to be stuck in as awkward a pose as his counterpart in the harness, the seated donkey, rather than merely an object of pity, also suggests stubborn refusal.

WS

29

30

31

32

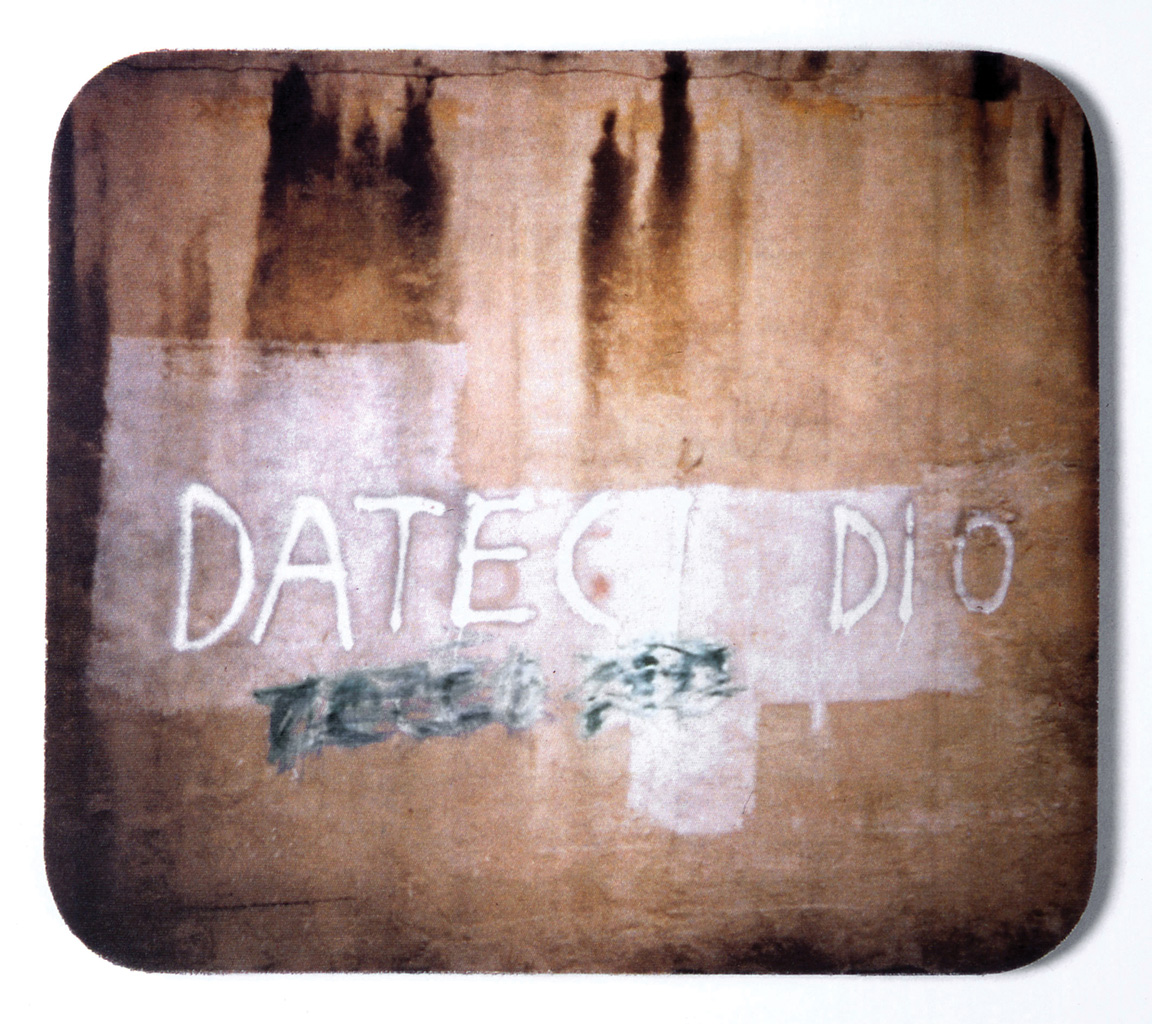

29 — Christmas ’94, 1994

30 — Christmas ’95, 1995

31 — Christmas ’96, 1996

32 — Christmas ’97, 1997

From 1994 to 1997, Cattelan produced an annual nativity scene that replaced traditional depictions of Christ’s birth in a manger with a sculptural vignette featuring surreal, erotic imagery and radical political iconography. The three nude figures in Christmas ’94 (1994) are based on a trio from the central panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (ca. 1500–05). Art historians continue to debate the significance of the bizarre sexual rites that Bosch depicted, but his combination of Christian imagery and scenes of nudes pleasuring one another with flower stems inspired Cattelan as he irreverently confronted the traditional Catholic art of his youth. For Christmas ’95 (1995), Cattelan evoked the shooting star that guided the three Magi to Bethlehem. Rendered in red neon lights, however, Cattelan’s star is more of a pentagram and, further, recalls the logo of the ultra-leftist group Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades). The third scene is the most enigmatic. Described by some critics as loosely interpreting Bosch’s idiosyncratic visions, Christmas ’96 (1996) comprises a rubber hand with tiny trees growing from its fingertips. The last of the four works—a battered and stained mouse pad with the words “Dateci Dio” (“Give us God”) scrawled on its surface—draws the nativity’s transcendent implications into the debased secular world. Smeared on a mouse pad, the impudent demand for salvation is equated with the worldly conquest of electronic information.

WS

.jpg)

33

33 — Untitled, 1994

In 1994, Cattelan decided to produce a small catalogue of his work and organized the project by pinning images of every piece he had ever made to a wall. A photograph of this installation became Untitled (1994), a single-image chronicle of his artistic output up to that point. He used the proceeds from the photograph’s sale to print the catalogue as a booklet. Made in miniature, it took the form of one long, narrow sheet folded like an accordion. The following year, dissatisfied with the final printed booklet but nevertheless inspired by the tiny images featured within, he embarked on a new project. Cutting out these images by hand and giving each a rough-hewn scalloped edge, he affixed them as stamps to postcards addressed to himself and put them in the mail. To his surprise, they were all delivered without detection despite the forged postage. By repurposing the images from the catalogue, he was able to revive a disappointing past project into something more intellectually and artistically satisfying.

ST

.jpg)

34

34 — Untitled, 1994

Cattelan was eighteen years old in 1978 when the ultra-leftist Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades) kidnapped and eventually assassinated the former Italian prime minister Aldo Moro. A photograph of the hostage posed before the group’s banner was published in newspapers worldwide and became an icon for a decade rife with conflict in Italy. For Untitled (1994), Cattelan installed a wall-sized enlargement of a newspaper front page announcing Moro’s capture, at Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne. With a crudely spray-painted line, the artist transformed the Red Brigades’ Communist logo into a shooting star. Although not an obvious Christmas motif, a similarly modified Red Brigade logo evokes the Star of Bethlehem that the Magi followed to witness the birth of Christ in Cattelan’s idiosyncratic mock holiday vignette Christmas ’95 (1995).

Cattelan’s appropriation of documents from Italian history suggests an ambivalent attitude toward that era’s radicalism. While old enough to have experienced the reaction to Moro’s murder, Cattelan also claims enough historical distance to address the upheaval with detachment and, indeed, irony. His conflation of the killing with the Christmas story, although seeming to mock the former, may instead acknowledge its transformative significance, initiating a process of reconciling the past.

WS

35

36

35 — Love Saves Life, 1995 [fig. 20]

36 — Love Lasts Forever, 1997 [fig. 21]

Love Saves Life (1995) and Love Lasts Forever (1997) are twinned sculptures depicting the Bremen Town Musicians. In this Brothers Grimm fable, four animals, who are no longer useful on their farms, escape from their murderous owners with the dream of becoming musicians. When they happen upon thieves who have holed up in a safe house, the animals’ singing frightens them away and the aspiring musicians move into the former hideaway, having achieved their freedom. Cattelan seizes on the tale as a utopian vision of a socialist community, the moral being that through friendship, shared commitment, and creativity, we accomplish our dreams. Unlike the tourist-attracting bronze public sculptures and Disney animations that have visually represented the story, Cattelan presents the animals as is: Love Saves Life is a stack of a taxidermied donkey, dog, cat, and rooster, with teeth bared, frozen in mid-song.

The underlying eeriness of the animals immobilized in a silent scream is underscored in Love Lasts Forever. When curator Kasper König requested Love Saves Life for the 1997 Skulptur: Projekte in Münster, Cattelan responded by creating a new sculpture picturing the animals two years later: the animal tower has been reduced to skeletons. Their experiment in freedom seems to have been tragically short, but their bonds have lasted through death.

DK

.jpg)

37

37 — Untitled, 1995

Invited to participate in the first Gwangju Biennial in 1995, Cattelan was given a large gallery in which to present his work. He left the space entirely dark, save a small spotlight in the center. Viewers crossed the darkened space to find that the light illuminated a sculpture so tiny that they had to crouch down in order to determine what it was. Close inspection revealed a figure of an ant, standing upright and confronting visitors with the gesto dell’ombrello. This gesture, tantamount to an obscenity in many Western cultures, is formed by making a fist with one hand and bending the arm upward into an L-shape, while reaching across with the other hand to grasp the upraised inner elbow. The diminutive ant insults those who have come to observe it (many of whom had crossed not just the room, but also the world in order to visit this show in South Korea), rebuffing them with its confrontational and decidedly unwelcoming attitude. The defiant figure, perhaps feeling small and overwhelmed, shields his insecurity with an act of bravado that is simultaneously amusing in its absurdity, disconcerting in its belligerence, and heartening in its temerity.

ST

.jpg)

38

38 — Untitled, 1995

Untitled (1995) is a playful photograph that shows the artist lying on his back, arms and legs curled up in the air, and tongue hanging out like a dog panting with excitement. The black-and-white photo, taken at ground level, features Cattelan in dark clothing set against a white background, grinning at the camera. After 1989’s Lessico familiare (Family syntax), it is Cattelan’s second photographic self-portrait, a form to which he would later return repeatedly. It also presages a series he began in 1997 based on dogs: some taxidermied to appear asleep, others skeletal and carrying newspapers in their teeth, but all deceased. In Untitled, Cattelan’s pose might mimic that of a dead cartoon animal, legs up and tongue out, but with a big smile and open eyes, the dog he performs here appears alert and begging to be petted. With this gamely photo, Cattelan portrays himself as a jester, rolling on the floor. In his role as a dog, he is obedient, eager to please, and awaiting a treat—a possible caricature of a keen young artist trying to succeed in the art world.

ST

39

— Another Fucking Readymade, 1996 [fig. 7]

39 — Reflection in his eyes, 1997

— Moi-même-soi-même, 1997

Though Cattelan’s work often exhibits imagery alluding to robbery and escape, for two prominent projects, he blatantly stole from other artists, proudly displayed the spoils, and emerged consequence-free. Another Fucking Readymade (1996) was Cattelan’s contribution to Crap Shoot at de Appel, Amsterdam. Challenged to create new work within weeks, Cattelan broke into the nearby Galerie Bloom along with members of a curatorial training program and hastily packed up the artworks and gallery furnishings with the goal of showing them at de Appel. The victimized gallery called the police, who used the license plate of the getaway vehicle to track the thieves, and the art center had to intervene to keep Cattelan out of jail. Since the works were removed from the exhibition space before the opening, they were never shown at de Appel, though the stacks of packing boxes have been memorialized in a photograph. In 1997, Cattelan presented the exhibition Moi-même-Soi-même (Myself, oneself) at Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Paris. From the signage and press release to the contents, the show exactly replicated Carsten Höller’s exhibition next door at the gallery Air de Paris, which included the works Reflection in his eyes (1997) and Moi-même-soi-même (1997), offering a distinctively clever pun. Confronted with mirrored exhibitions without explanation, visitors were left to grapple with knotty questions of authenticity and authorship, unaware that Cattelan’s show was the copy.

The title Another Fucking Readymade flippantly dismisses Marcel Duchamp, suggesting that the readymade is no longer interesting. However, Cattelan has urged viewers to focus on both interventions’ experiential qualities, including the sense of displacement, recurrence, or renewal. Both works’ success seems to be the introduction of confusion into the exhibitions by way of reflection, distortion, and relocation.

DK

40

40 — Bidibidobidiboo, 1996 [fig. 2]

Bidibidobidiboo (1996) features a life-size, taxidermied squirrel slumped over his yellow, formica-topped dinette, a revolver at his feet, and dirty dishes in the adjacent sink, revealing the pathos within Cattelan’s particular brand of comedy. The scene’s unexpected melodrama—at once amusing in its absurdity and disturbing in the deep, human despair it represents—plays on anthropomorphized storytelling from Aesop to Walt Disney. For Bidibidobidiboo, Cattelan was specifically inspired by Chip ’n’ Dale, Donald Duck’s mischievous chipmunk foes in Disney cartoons of the 1950s. Their playful, striving attitudes are the antithesis of Cattelan’s poor anonymous squirrel, who is confined to a life of economic immobility evidenced by his shabby surroundings. The work’s title, meant to conjure the magic words of Cinderella’s fairy godmother (“Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo”) in the 1950 Disney film, demonstrates the impotence of cartoon magic in the face of real-world misfortune. Cattelan modeled the squirrel’s surroundings on the humble kitchen of his childhood, typical of an Italian working-class apartment, heightening the scene’s authenticity. In this miniature replica, displayed on the floor so that viewers must bend down to examine it, Cattelan produces a tiny alter ego, an alternate story line perhaps, that kneeling viewers pay reverence to.

DK

.jpg)

41

.jpg)

42

41 — Untitled, 1996

42 — Untitled, 1996

Untitled (1996), which was once called Free Carrot, features a bunny with monstrously elongated ears suspended in mid-air. The image of a white rabbit belongs to a stratum of popular culture that includes Easter bunnies, magic shows, and Hallmark cards. Grounded in that context, Cattelan’s otherwise morbidly disfigured creature might read as a banal joke; the bunny’s erect ears seem to register its uncontainable excitement about the prospect of a “free carrot.” Bizarre in physical proportion but conforming easily to a cultural type, Cattelan’s rabbit is equally strange and familiar, like the creature that Alice followed down the rabbit hole in Lewis Carroll’s fable.

Similarly charting an unstable boundary between seductive kitsch and perversity, another untitled 1996 work comprises two hares with enlarged eyes that sit silently on a small shelf. Furry animals with enormous eyes can seem especially cute and endearing, but Cattelan’s rabbits stare with an alien intensity that suggests genetic modification gone wrong. Previously called Riccardo Cuor di Leone, the rabbits are in fact hybrid creatures, having been fitted with glass eyes designed for taxidermied lions. The original title’s reference to the medieval crusader Richard the Lionheart points to the way that such cross-species hybrids, while disturbing when taken literally, have long provided metaphors central to human identity.

WS

.jpg)

43

43 — Untitled, 1996

In an untitled black-and-white photograph from 1996, five hands, spreading out their first two fingers as in a peace sign, join to form a five-pointed star. The image was used on the invitation to Cattelan’s 1996 solo exhibition at Ars Futura Galerie in Zurich. The installation reinterpreted the setting of the Order of the Solar Temple’s tragic mass suicide, which had occurred just two years before in an underground chapel in the Swiss Alps. Cattelan adapted the cult’s ceremonial robes and symbols but installed an incongruous element: a disco dancer.

Outside Switzerland, the star image in the photograph took on larger significance. For any Italian, the link to the terrorist organization Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades), whose symbol is an encircled five-pointed star, is immediate. In the image, the disembodied but united hands offer a sense of both the anonymity and community of groups built on shared ideology. In turn, the crystalline formation suggests the power structures formed by such organizations. The artist has also noted that he has used hands to make shapes and form gestures in his works since the beginning of his career. Nonetheless, the dynamic formal composition with the black background and manicured hands is highly stylized, evocative of a sleek commercial image. By invoking the loaded symbol in a photograph that looks as if it could have been lifted from a magazine, Cattelan mocks the legacy of extremist groups of both Switzerland’s and Italy’s recent past.

DK

.jpg)

44

44 — Untitled, 1996

— Novecento, 1997 [fig. 16]

Untitled (1996) is the first of Cattelan’s works to feature a taxidermied horse suspended from the ceiling. Novecento (Twentieth century, 1997) revisits the image using the body of a former racehorse named Tiramisu. In the latter work, which he considers more successful, the horse’s legs are extended and its head positioned lower in relation to its body. The distended limbs and drooping posture may better emphasize the hopelessness of the horse’s situation as if it has already resigned to its fate and succumbed to the effects of gravity.

The increasing importance of taxidermy to Cattelan’s practice by the mid-1990s reflects his interest in exploring how humans project their ideals and anxieties onto images of animals. The titles of these two works refer to fraught episodes from the twentieth century: Untitled was originally called The Ballad of Trotsky, evoking the popular folk songs composed in Mexico to honor the assassinated Soviet revolutionary, Leon Trotsky, while Novecento shares its name with both Bernardo Bertolucci’s epic 1976 film about the rise of Italian Fascism and a conservative artistic movement that emerged in Milan in the 1920s. Created just before the turn of the millennium, Cattelan’s suspended horses may function equally well as retrospective emblems for a century marked by crushed dreams and cruel spectacles of violence, or as morbid heralds for the century to come.

WS

45

— Andreas e Mattia, 1996

45 — Kenneth, 1998

Cattelan’s sculptures of faceless homeless people, created out of rags and articles of clothing and placed in city streets, are contingent with the urban landscape, illuminate unfair social structures, and aggravate the municipal authorities. And ultimately, they play a prank on their audience. Cattelan clearly relishes the comic reactions to these decoys, as when the first version Andreas e Mattia (Andreas and Mattia, 1996) was shown at a group show in Turin and visitors called the police to have the figure removed. Two years later, when his effigy Kenneth (1998) was installed on the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, campus, it inspired theft, copycat sculptures, and the imagery to support a campus protest against rising tuition costs.

Playfulness aside, these works depend on a serious reality—the manner in which people see the homeless as inanimate features of the urban environment to be avoided and ignored. Rather than intending for his sculptures to scandalize the public, Cattelan draws attention to the coarseness of everyday life. On another level, the reappearance of the tramp in Cattelan’s work (several versions have been presented) suggests that the homeless are among the cast of characters that Cattelan uses to act out the narrative of the artist in society: anonymous peripatetic fixtures who are ignored until successful. With these avatars, Cattelan creates disguised public sculptures that reveal the social friction that they commemorate only when recognized.

DK

.jpg)

46

.jpg)

47

46 — Untitled, 1997

47 — Untitled, 1997

Cattelan’s contribution to a group exhibition at Stadio della vittoria in Bari, Italy, Untitled (1997) is comprised of three light boxes in the shape of the letters B, A, and R. The work is modeled after the generic signs commonly used in Italy to denote the site of a bar, a type of establishment that serves drinks, pastries, and small sandwiches. In this work, Cattelan explored the signifiers that announce certain spaces and the ease with which these intentions can be confused and redirected. Hung outside the exhibition venue, the sign seemed to indicate the entryway for a bar, perplexing both those intending to arrive at an art space and those expecting to find refreshment. Because of this innocuous bait and switch, surely several unassuming visitors entered the gallery for a coffee, but then stayed to look at the exhibition.

Later that year, Cattelan reprised the concept for a show at Galleria Massimo De Carlo, Milan, with a red sign in the shape of a cross, typically used in Italy to identify a pharmacy. Placed outside the gallery, Untitled (1997) seemed to advertise a shop selling medicine, not art. These signs, misleading though they are, might also suggest that the art inside can offer the same salve as a drink or an aspirin.

ST

48

.jpg)

49

48 — Charlie Don’t Surf, 1997 [fig. 3]

49 — Untitled, 1997

Cattelan first installed Charlie Don’t Surf (1997) at the Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin. In an ornate room, he positioned the figure of a young boy seated at a desk in front of an enormous window. Only upon approaching closely could viewers see that each of the boy’s hands had been pinned to the desk with a pencil—a posture that is replicated in a work from the same year showing a similarly mutilated but disembodied hand.

The surprisingly grisly scene, suggesting a classroom crucifixion, recalls the childhood traumas that Cattelan frequently describes in interviews, including a particularly memorable failed writing test, and an incident in which he stabbed a classmate in the hand with a ballpoint pen. Like many Cattelan works, Charlie Don’t Surf intertwines autobiographical narratives with allusions to popular culture. In the Vietnam War film Apocalypse Now (1979), Robert Duvall plays a brash cavalry officer with equal affection for well-coordinated aerial assaults and quality surfing opportunities. Perfectly articulating this perverse combination of violence and whimsy, “Charlie don’t surf!” serves as the officer’s rallying cry for a brutal attack. The name “Charlie”—Vietnam-era American military slang for its guerrilla opponent, the Vietcong—recurs in several Cattelan titles and designates an alter ego of sorts.

WS

50

50 — Dynamo Secession, 1997

— Untitled, 1997

Invited to exhibit at the 1997 Vienna Secession and offered a space in the basement, Cattelan presented Dynamo Secession, which consists of two bicycles wired to generators and overhead lightbulbs, connected so that pedaling powers the light. Uniformed museum guards constantly rode the bicycles to provide feeble, flickering light from the low-wattage bulbs that had replaced the galleries’ existing lighting. By linking his installation in the institution’s underbelly to its overall operation, Cattelan visualized the labor that makes up a museum, from the workers’ hourly toil to the more abstract work of artistic production. Drawing on the cartoon image of a bare lightbulb representing a creative spark, Dynamo Secession creates a scene of figures chasing futilely after an idea.

Asked to contribute to the Venice Biennale’s Italian pavilion that same year, Cattelan placed used bicycles (Untitled, 1997), next to his coexhibitors’ highly valued paintings, among other interventions. Highlighting the incongruity of the outside world and the exhibition display, the bicycles were so subtle that exhibition attendants repeatedly removed them, only for Cattelan to replace them. Art historically, the used bicycles invoke Marcel Duchamp’s first readymade Roue de bicyclette (Bicycle wheel, 1913); they also serve as a personal symbol for the artist, for whom bicycles are a primary means of transportation.

DK

51

51 — Less than ten items, 1997

For a 1997 solo exhibition at Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin, Cattelan installed work not only in the room designated for his show but also in other parts of the museum, such as the hallways and permanent-collection galleries. One such work was Less than ten items (1997), a group of overly elongated shopping carts that seemed to invite visitors to fill them—perhaps even with the art of the galleries in which the carts were found.

Less than ten items also calls attention to the close connection between art collecting and other forms of commercial consumption. The absurdly long carts seem particularly designed for a shopping spree, the kind of concentrated bulk purchasing that major art fairs encourage. Their distorted size seems to imply that the user will need plenty of space to hold the many purchases from such events. The work’s title is taken from standard supermarket signage that denotes an express lane. That those using these carts are express shoppers suggests that their purchasing decisions are made quickly and impulsively.

ST

52

Ostensibly a self-portrait, Spermini (1997) consists of hundreds of tiny, latex masks of Cattelan’s face. In projects and interviews, Cattelan has suggested that his goal is to subtly insinuate his work into the real world, and these impish protrusions illustrate that ambition. While the cartoonish caricatures avoid true visual representation, the sense of humor and playful barrage offer a layered portrait of the artist’s character while indicating that one’s personality can be seen in innumerable ways.

The masks have been displayed in a number of different configurations since 1997 and have even inspired a New York–based bootlegger who sells copies at art fairs. This subdividing and rapid dissemination live up to the bawdy title. At the same time, given that ejaculate has at times been considered a viable medium for a scornful male artist, Cattelan’s diminutive figures poke fun at the egotism behind such brash displays of masculinity.

DK

53

.jpg)

54

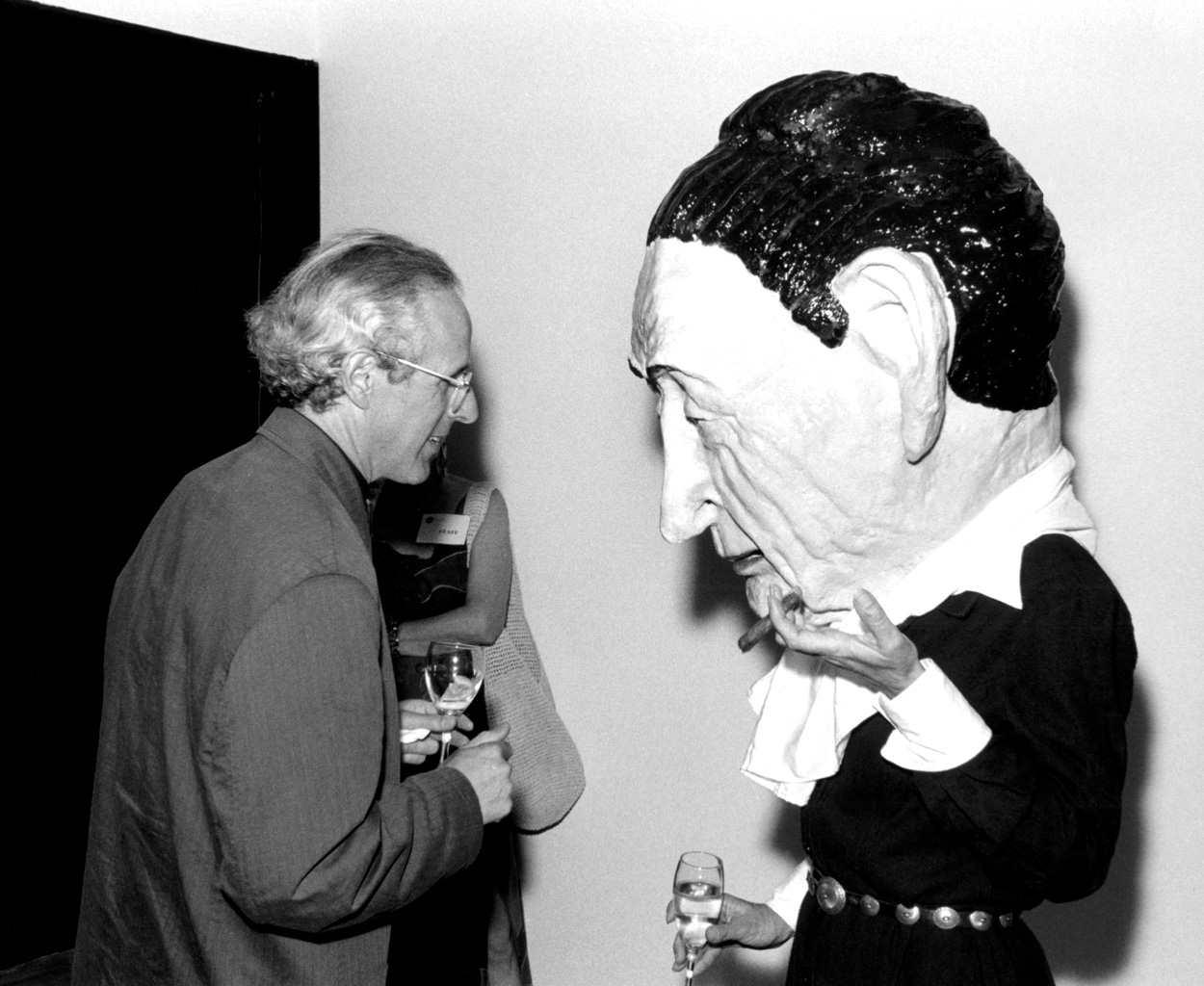

53 — Georgia on My Mind, 1997

54 — Untitled, 1998 [fig. 27]

Among the many noteworthy attendees at the 1997 SITE Santa Fe opening, one guest stood out: Georgia O’Keeffe made a posthumous appearance in the form of a costumed actor. Wearing an oversized papier-mâché head, the character mingled with guests at the event, which occurred soon after a nearby museum dedicated to the painter was inaugurated. The city of Santa Fe takes great pride in its association with O’Keeffe, and the protagonist of Georgia on My Mind (1997) made all the more explicit her status as its emblematic art star.

The following year, Cattelan revisited the concept of the artist as mascot for his Projects series show at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. He identified Pablo Picasso as the museum’s signature artist since he is often hailed as the father of modernism and is significantly represented in its collection. For the run of the show, an actor dressed as Picasso in a large mask and the artist’s striped boat-neck shirt occupied the galleries. Modeled after festival figures from parades in Viareggio, Italy, the character behaved like an amusement-park mascot, greeting visitors, posing for pictures, and signing autographs. The presence of the iconic character called attention to the fact that MoMA, like other major tourist attractions, is an international cultural destination and engages in self-promotion, from logo-stamped merchandise to affiliations with iconic individuals. The performance also highlighted the phenomenon of the glorified celebrity artist and the degree to which art history idolizes such figures.

ST

55

56

55 — Stone dead, 1997

56 — Good Boy, 1998

With his series of taxidermied dogs, Cattelan employs familiar animal forms to question human attitudes about death. The artist avoids exhibiting the dogs in ways that would make them easily identifiable as artworks. Viewers might encounter the dogs curled up in an inconspicuous corner of the room or napping in a chair, rather than on pedestals or cordoned off behind ropes. Unlike Cattelan’s taxidermied horses, donkeys, and assorted barnyard animals, the dogs do not immediately seem out of place in a collector’s house or a museum. Instead, their presence can at first impart a homeyness to the space, as if a curator had casually brought a pet to work. In that sense, the dogs’ domesticity functions as a kind of camouflage, delaying and intensifying the moment of comprehension. Indeed, the dogs’ deceptively lifelike appearance only heightens the morbid implications of their preservation. Cattelan has permanently fixed their physical presence, but in doing so he has also brought into sharper focus the more fundamental reality of their condition.

WS

57

— Tourists, 1997 [fig. 29]

57 — Others, 2011

Germano Celant, curator of the 1997 Venice Biennale and its Italian pavilion, organized a collaboration between Cattelan and two artists with markedly divergent aesthetics: reductivist sculptor Ettore Spalletti and Neo-Expressionist painter Enzo Cucchi. As part of his contribution to the exhibition, Cattelan installed a flock of stuffed pigeons in the pavilion’s rafters and along its sprinkler system and heating ducts. Silently perched above the gallery, the birds appeared to watch over the visitors who in turn had come to look at the work on view. Recalling the menacing flocks in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), the pigeons appeared to intrude on the space reserved for art, an effect heightened by a generous smattering of bird droppings on the floor.

Cattelan developed the idea for the piece, entitled Tourists (1997), following his initial visit to the exhibition hall. In contrast to the slick galleries familiar to visitors, he found that the pavilion had become a dilapidated home for hundreds of pigeons during the off-season. Tourists highlighted parallels in the gallery’s double life as both a site for hoards of art aficionados and for the birds that prove a perennial nuisance in Venice. Through this clever use of “found” materials that were already on-site, Cattelan is perhaps subtly referring to the characteristic economy of means associated with Arte Povera, the Italian avant-garde movement that Celant championed as a critic in the 1960s and ’70s.

In 2011, Cattelan created a new iteration of the work for the international exhibition of the Venice Biennale, curated by Bice Curiger. Now titled Others and encompassing over two thousand birds, clusters of pigeons were prominently displayed on the exterior and throughout the galleries of the Palace of Exhibitions in the Giardini.

WS

.jpg)

58

58 — Untitled, 1997

In an untitled work from 1997, a taxidermied ostrich buries his head in the gallery floor, unwilling to participate in the exhibition and hiding in full view. The work was shown in the exhibition Fatto in Italia (Made in Italy), organized by Paolo Colombo for the Centre d’art contemporain, Geneva, and the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London, prominently signaling the growing significance of contemporary Italian artists. Cattelan expressed his feelings toward the recognition not with a posture of conquest or even defiance, but with an image of ambivalence. He attempted to lash out in other areas by covertly spray-painting “Bloody Wops” on an ICA exterior wall and secretly planting paper bags containing inactive hand grenades, which were later stolen from the galleries. In contrast, the ostrich betrayed a distinct sense of vulnerability. The flightless bird is in the gallery space yet desperately wishes it were elsewhere, a universally accessible attitude that may also have applied to the artist’s predicament. Beyond the ostrich’s existential quandary, the viewer also experiences a sense of double reality, as the work is just realistic enough to invite the visitor into its own fiction. Without a pedestal, the sculpture is stripped of any monumentality, and the young ostrich behaves in the gallery exactly as it does in nature. In this way, the viewer is transported into the surreal space of the artwork.

DK

59

As part of his contribution to the 1997 Skulptur: Projekte in Münster, a decennial event that integrates commissioned artworks into public spaces, Cattelan focused on the town’s idyllic Lake Aa. Aspiring to create a macabre mythology around the site, he deposited a lifelike female figure in the water that would confront boaters with the horrifying vision of a discarded corpse or even a spectral presence. Although the sculpture was intended to be visible just below the lake’s surface, it sank into the depths almost immediately after its installation, leaving only a label on the grassy banks (listing the work’s former title, Out of the Blue), a documentary photograph, and a tangle of rumor and conjecture. Despite this unforeseen malfunction, the project proved more powerfully resonant in the public imagination than the artist could have imagined. Local residents were so troubled at the thought of this eerie presence concealed in a cherished spot that the lake was dredged and the “body” removed and destroyed, returning the site to a state of pastoral innocence.

KB

.jpg)

60

60 — Untitled, 1997

Like his series of taxidermied dogs that appear to be sleeping comfortably, the canine skeleton that Cattelan posed with a newspaper in its jaw is an uncanny image of a familiar domestic animal. The dog’s skeleton has been preserved as if an object in a natural-history museum; yet the scientific pretense for the otherwise morbid act of displaying a skeleton falls away with the addition of the paper wedged between its teeth.

Fetching the newspaper and delivering it by mouth is a task assigned to dogs in cartoons, usually for comic effect when the paper arrives covered in drool. While emphatically real in that the skeleton constitutes the remains of a living thing, Cattelan’s dog has thus also been shaped by shared cultural conventions. The vignette employs a well-worn iconography of cuteness—the newspaper alone suggests a loyal animal eager to please its master. Intertwined with evidence of death, the dog has thus been stripped of any hint of its own personality and is frozen in a posture of service, rendering the creature incapable of anything but eternal loyalty.

WS

.jpg)

61

.jpg)

62

61 — Untitled, 1997

62 — Untitled, 2000

For a series of miniature sculptural tableaux, Cattelan posed taxidermied mice in various human settings or anthropomorphic poses. Whether reclining in a deck chair beneath a toy umbrella, engaged in a lively domestic spat, dangling on a rope, or simply relaxing on a cushion, these pests-cum-protagonists are alternately adorable and revolting. Though the violence to which Cattelan subjects animals in other works is absent in these sculptures, the implied narratives are not entirely harmonious. In one work, a lone mouse maintains a precarious grasp on a string suspended above the ground like a tightrope walker who has lost his balance. For another vignette, Cattelan created a fully domesticated mouse hole, complete with a tiny front door set into a wall and a garbage can placed outside. The work’s cozy feel is disrupted by the sounds of an argument emanating from inside the mouse house. The suggestion that a pair of mice lovers could be experiencing ordinary trials and tribulations in their relationship may only facilitate closer identification between viewers and animals. Cattelan recorded the audio one night at a residency at Artpace, San Antonio, Texas, having asked the director to argue with her husband.

WS

.jpg)

63

63 — Untitled, 1997

— Untitled, 1997

For a solo exhibition at Le consortium in Dijon, France, in 1997, Cattelan emptied the entire gallery space of art objects. The only obvious trace of his intervention entailed an act of removal: in one room Cattelan dug a rectangular hole in the floor, heaping what appeared to be pulverized remnants of the gallery’s foundation and plumbing system into an adjacent pile. The excavation drew attention to the physical site underlying the otherwise contemplative space bounded by the gallery’s ethereal white walls. At the same time, the hole’s resemblance to a freshly dug grave lent a deathly quality to Le consortium’s stark, empty rooms. Only the signs of life emerging from a large metal cabinet in the main lobby interrupted the tomblike atmosphere. Having removed the cabinet’s back, Cattelan positioned it in front of a doorway to the offices so that employees had to pass through it on their way to and from work. This playfully banal version of a secret passageway led not to the thrilling worlds of spy movies (much less the rich fantasyland of C. S. Lewis’s wardrobe) but merely to routine office activities, which constitute a sharp counterpoint to any romantic notions of “art work.”

WS

.jpg)

64

64 — Untitled, 1997

Invited to participate in the 1997 India Triennial in New Delhi, Cattelan proposed to exhibit a taxidermied cow with two Vespa handles inserted into its head as horns. The strange hybrid—a cow with the features of a bull—combined an animal that Hindus revere with an internationally recognized icon of Italian industrial design. No stranger to controversy, Cattelan had taken aim at various, less literal sacred cows in the past. His work was in fact prevented from being exhibited at the triennial, but only because of delays in India’s customs agency rather than concerns about the work’s handling of a religious symbol.

Cattelan frequently describes himself as an artist without a fixed home or studio, roaming from one project site to the next. Posed in an awkward seated position, the taxidermied cow can be seen, perhaps, as an ironic meditation on mobility. Part scooter, part beast of burden, Cattelan’s transcultural assemblage nonetheless appears to be stuck in place.

WS

65

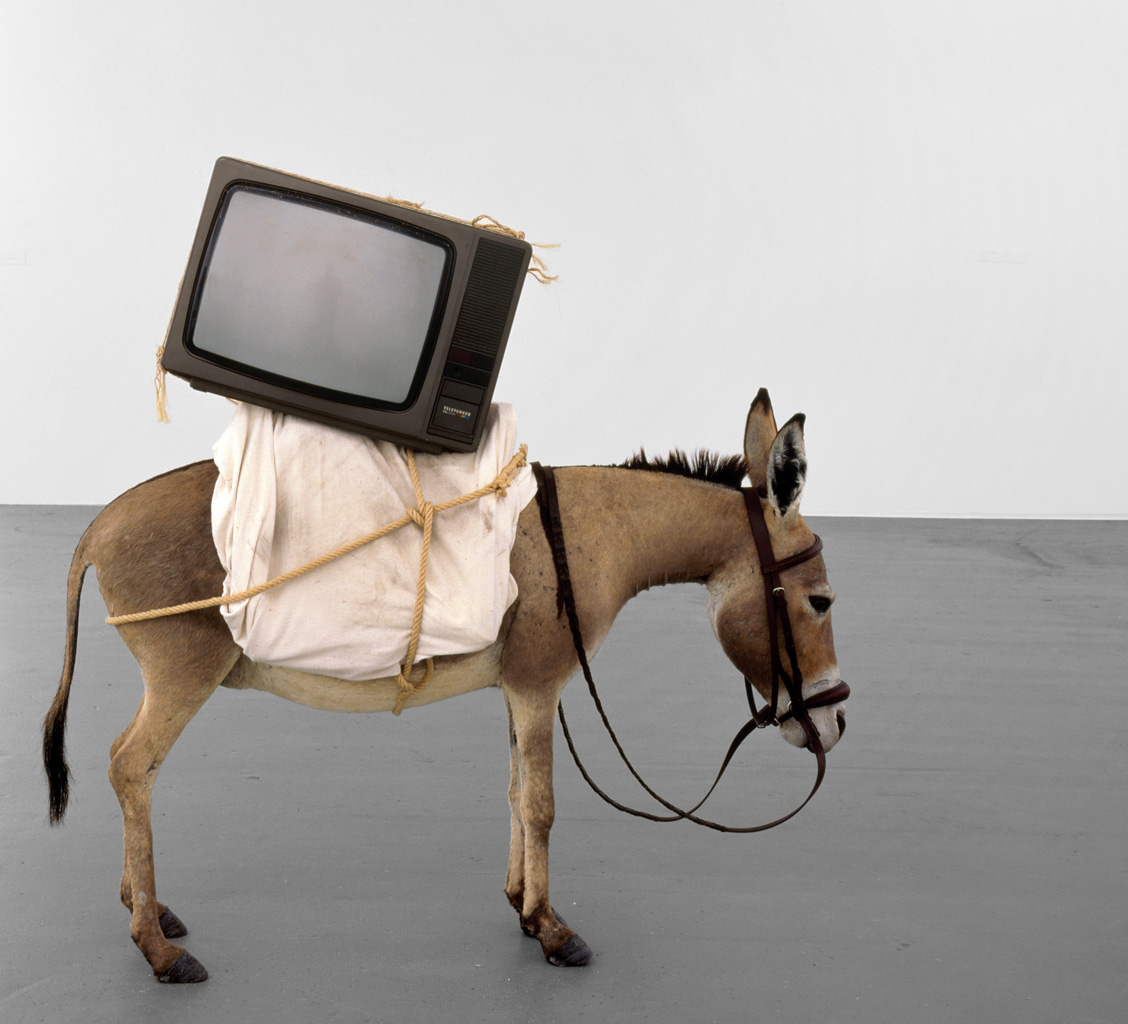

65 — If a Tree Falls in the Forest and There is no One Around it, Does it Make A Sound?, 1998

If a Tree Falls in the Forest and There is no One Around it, Does it Make a Sound? (1998) consists of a taxidermied donkey with a 1980s-era television set strapped to its back with a rope. One plausible narrative for the ambiguous scene is that it depicts the transport of a television to a remote, rural area. Given that the titular question is meant to demonstrate that reality depends on observation, one wonders about the implications for the contemporary world, in which few territories remain untouched and much of our observation takes place through a screen. On another level, the work invokes the image of Christ on a donkey, which is a prevalent allegory for his sober and simple lifestyle. In Cattelan’s vision, the spiritual leader is replaced with a conveyor of media culture. The work’s potential interpretations multiply when one considers that Cattelan has previously identified with the figure of the donkey. His career has also been marked by a perceptive manipulation of the media and an awareness that artworks exist primarily as images that only gain power with reproduction. In If a Tree Falls . . . , the communication device has the pride of place, and the animal, head bowed, is resigned to its weight.

DK

.jpg)

66

66 — Untitled, 1998

For Manifesta 2 in 1998, Cattelan submitted simple instructions for a new work: install a living olive tree in the Casino Luxembourg, its roots secured in a large mound of soil. Untitled (1998) confronted viewers with an impossible sight—an enormous living sculpture transplanted into an incongruously opulent room, a sample from the natural world inserted into an art exhibition. The olive tree’s lyrical associations, from the crown of leaves bestowed on classical Greek and Roman victors to the Christian allegory of the covenant between God and man, are not likely significant to Cattelan; of greater importance is the simple image stripped of potential references. Disappointed in the rigid cube of soil in Luxembourg, which referred too much to Minimalist sculpture, Cattelan requested a looser, rounded base when the work was acquired in 1999 by Castello di Rivoli, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin.

The olive tree’s Mediterranean origin does suggest a sly autobiographical note in the form of Italian territorialism, literally exporting part of the Italian landscape. Its national lineage is further underscored by Cattelan’s acknowledged inspiration: artist Alighiero Boetti’s unrealized Monumento all’agricoltura (Monument to agriculture). From 1969 through 1970, Boetti worked on a plan for a permanent monument in Milan that would consist of an apple tree growing out of a twenty-five-meter-tall column of soil. The unrealized work achieved mythical status within Arte Povera as an impossible, utopian project. By realizing Untitled (1998), Cattelan’s homage to Boetti created a monument to visionary yet impractical ideas.

DK

67

67 — 6th Caribbean Biennial, 1999 [fig. 34]

In response to the rapid rise of international biennials in the late 1990s, Cattelan, in collaboration with curator Jens Hoffmann, organized his own. With a biennial president, press office, and official advertisements placed in art magazines, the 6th Caribbean Biennial seemed a legitimate art-world endeavor. Cattelan designed the project, however, so that there would be no actual exhibition. Ten prominent artists, selected for their ubiquity in other biennials, were invited to participate, their attendance constituting their only contribution. Instead of presenting their work, they spent the eight days of the exhibition’s run relaxing on the beaches of Saint Kitts, a venue chosen for its appeal as a travel destination. With this project, Cattelan called attention to a biennial culture in which cities use the contributions of successful artists to legitimize their exhibitions and draw international tourism, while artists benefit from funded travel to an exotic locale.

ST

68

68 — La Nona Ora, 1999 [fig. 30]

La Nona Ora (The ninth hour, 1999) is among Cattelan’s most well-known and provocative works. First exhibited at the Kunsthalle Basel, the realistic wax statue of Pope John Paul II crushed by a meteorite forms part of an elaborate theatrical tableau. The stricken pope, dressed in formal ecclesiastical gowns, lies prostrate on a broad, red carpet. Shards of glass surround the figure, suggesting the meteorite’s presumed point of entry through a smashed skylight overhead. Named for the time when Christ died on the cross, the dramatic image of physical suffering is also a comically irreverent affront to the head of the Catholic Church. The pope is one of many authority figures that Cattelan has targeted in his practice, and the artist denies that La Nona Ora is specifically anti-Catholic. Still, Cattelan’s vivid depiction of the religious leader felled by a rock from the heavens has drawn charges of blasphemy from critics, and the piece was vandalized when exhibited in the pope’s native Poland in 2001. The work exists in two different versions, one in which the pontiff is clothed in white robes and one in which he wears gold and red vestments.

WS

69

Mini-me (1999), a twelve-inch figure peering down from a ledge, is one of the artist’s most diminutive self-portraits. Sharing its name with a character in the 1999 Austin Powers movie (the tiny clone of Dr. Evil), Cattelan’s character likewise seems to represent its procreator’s inner voice. Whereas Dr. Evil’s miniature acts out his id, Cattelan’s Mini-me grips the edge of his perch and looks downward anxiously in an accessible expression of self-doubt. The work perhaps illustrates the cautious superego, more along the lines of Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio’s conscience.

Like Cattelan’s other self-portraits, this alter ego exhibits a tension between self-effacement and self-promotion. Mini-me is an editioned work, and each unique variant is accessorized with different clothes that were exact replicas of current items in the artist’s wardrobe. A self-portrait whose form and display recall a collectible action figure indicates an instinct toward replication and increased visibility. At the same time, the notion of creating avatars and the title Mini-me refer in part to Cattelan’s history of deflecting a codified public persona by sending others in his place to public engagements.

DK

.jpg)

70

70 — Mother, 1999

For the Aperto section of the 1999 Venice Biennale, Cattelan hired an Indian holy man known as a fakir to bury himself beneath a mound of dirt for two hours at a time. Only the fakir’s hands, pressed together in a gesture of prayer or greeting, protruded from the suffocating pile of earth. Fakirs routinely perform such grueling feats as affirmations of spiritual devotion, but the context of a largely secular international art exhibition complicated the act’s meaning. By ceding his space in the prestigious exhibition to the enactment of a ritual with elements common to both Hindus and Sufis, Cattelan’s intervention may have reflected the biennale’s multicultural ethos. Yet the fakir’s act was removed from its cultural moorings and aestheticized. As much as it belonged to a specific tradition of ascetic mysticism, a more familiar reference for the biennale crowd would have been Western performance and body art from the 1960s and ’70s. The specific cultural origins for the performance eluded many critics, who disagreed about whether the man was Hindu or Muslim; whether he should be called a fakir, sadhu, or yogi; or even whether the burial, which occurred in private, was faked. The title of the piece further compounded its ambiguity. Cattelan has explained it in unusually personal terms as a reflection on the burial of his own mother, whose funeral he had been unable to attend.

WS

71

71 — Ten Part Story, 1999

In the mid-1990s, Cattelan developed an interest in photography and began taking pictures during his travels and in his everyday life. Uncertain as to how he might formalize this process or integrate it into his broader practice, he started sending the images to recipients around the world as postcards. The various photographs, which depicted things such as a painted ceiling fan, a marked-up chalkboard, and a plastic picnic table set, were sent in groups of ten, each set becoming a “ten-part story,” as the title suggests. These stories are not meant to communicate a particular narrative, but the grouped images encourage the viewer to find associations and relationships among them. This project became a way for Cattelan to begin to understand how photography could operate in his work, and the explorations of Ten Part Story (1999) are related to his simultaneous experiments with Permanent Food (1996– ), a magazine composed entirely of appropriated images, the relationships between which suggest unexpected narratives.

ST

.jpg)

72

72 — Untitled, 1999