fig. 34

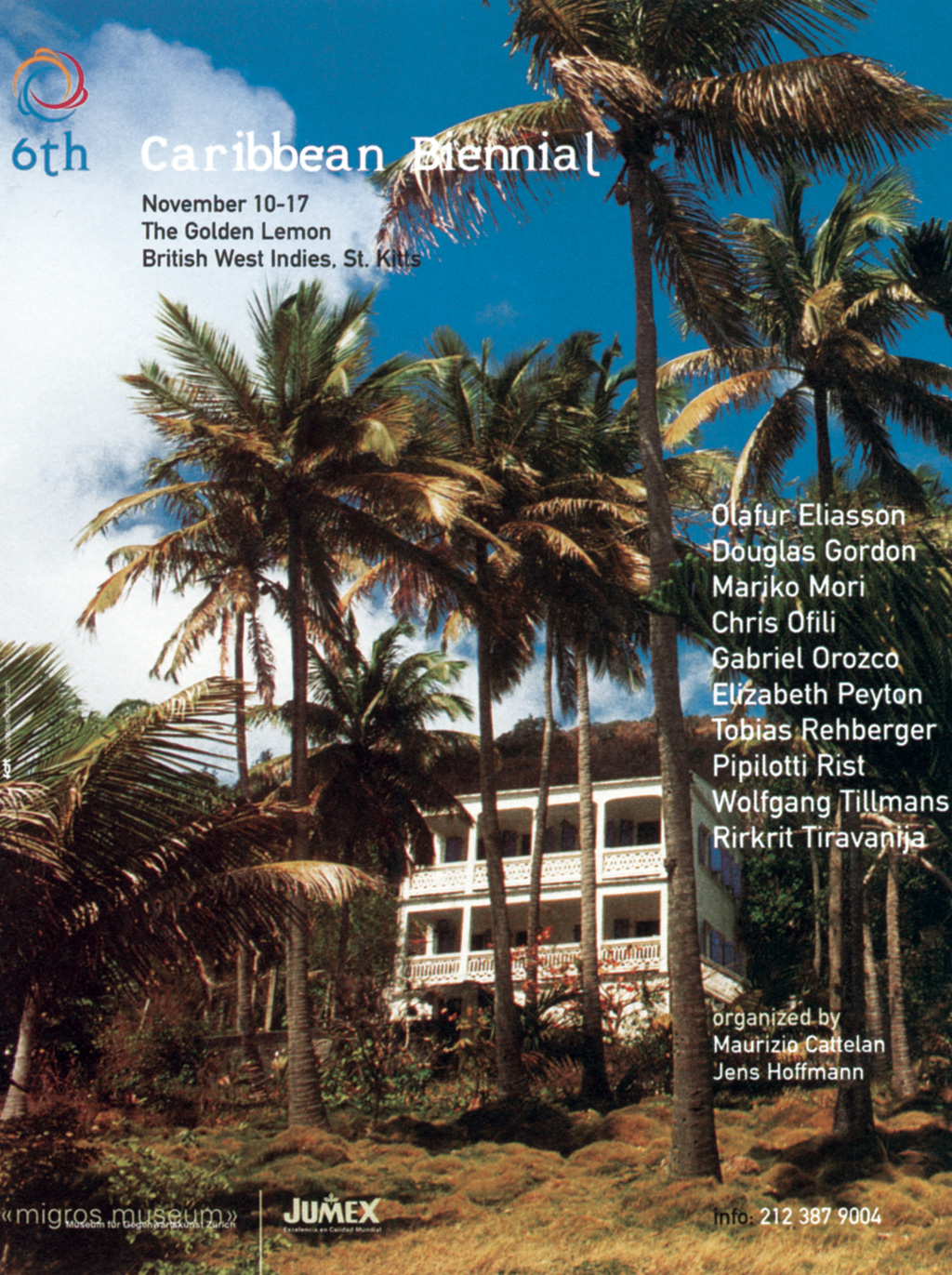

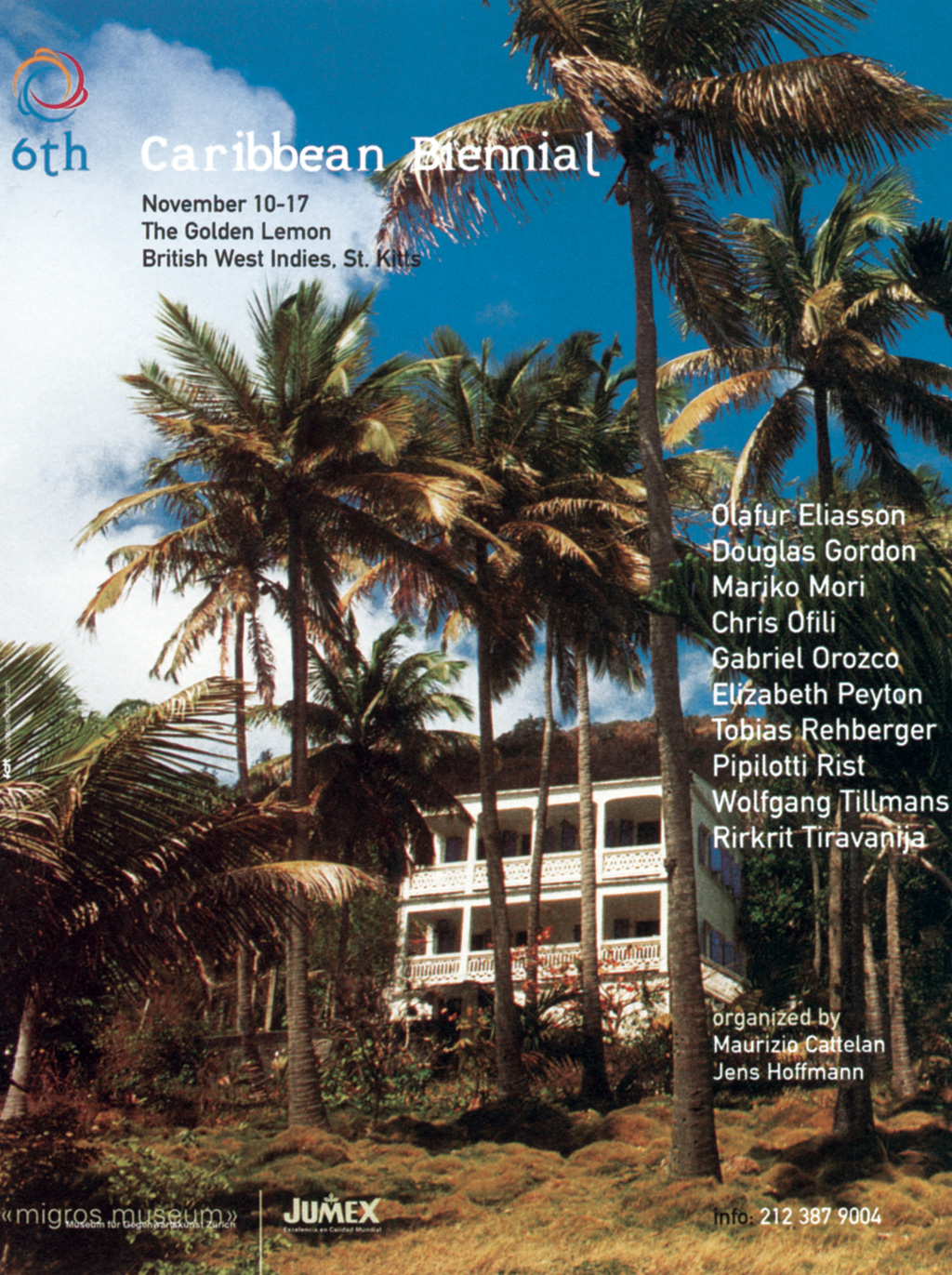

Advertisement for the 6th Caribbean Biennial (1999), 1999

5

Spectacle Culture and the Mediated Image

I’m really seduced by images that already belong to everybody, very public, basic images, things that have an international language. The more you go basic, the more you are close to icons.106

ABOVE all else, Cattelan understands and exploits the capacity of images to seduce, provoke, and disrupt. From the beginning of his career, he has orchestrated actions, created sculptures, and produced events with their dissemination as photographic images in mind; he judges the success of a work by how well it translates into a picture and how well this picture is reproduced and transmitted by the media. The conversion from three to two dimensions is not, in Cattelan’s view, a diminishment of effect but rather a natural transition through which the work fulfills its destiny in the world. Certainly, the shock value associated with La Nona Ora, Him, and Now earned these works extensive media attention well beyond the rather circumscribed circle of art publications, as was the case more recently with coverage of L.O.V.E. in Milan. The iconic visuality of these sculptures as singular, recognizable figures makes their adaptation to the pictorial realm extremely effective. And their persuasive “aura” as original objects is not devalued when they are illustrated in print. The images manage to have the same destabilizing intellectual and emotional impact as the sculptures do in person. When reproduced in mainstream journalistic outlets—newspapers, websites, and magazines—the images interrupt the expected flow of information, eliciting either confusion, indignation, or, in some cases, respect for the brutal honesty of the scenario depicted, even if it is fictional.

Cattelan has a highly developed editorial eye and has assimilated the tactics of advertising and commercial photography, so prevalent in our media-saturated culture.107 His strategic emphasis on the photographic within what has evolved into a largely sculptural oeuvre is symptomatic of the fact that we all operate within an inescapably mediated society. Photography and screen-based representation have infiltrated all aspects of daily life, effectively blurring the differences between lived and perceived reality. Condemned by Guy Debord in 1967 as the “society of the spectacle,” late-capitalist culture has become a shadow world in which “everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.”108 Accordingly, the commodity and the image have become indistinguishable, and all social relations are formulated under their conjunction. As a child of the 1960s, Cattelan is a product of this relentlessly mediated environment, in which the spectacle is no longer “understood as a mere visual excess produced by mass-media technologies” but rather “a worldview . . . that has become objective.”109 Cattelan is not at all interested in conquering the totalizing perspective of the spectacle, in opposition to Debord and the other Situationists, critical forbears to his artistic generation. Rather, he infiltrates spectacle culture in order to choreograph its effects from within, with a long-term goal of reclaiming subjectivity and raising consciousness about significant moral issues.110

Cattelan’s efforts to harness the media date to the very beginnings of his career, when in 1990 he created a bootleg version of a Flash Art magazine cover that showcased his own work (cat. no. 9). By appropriating the cover of Italy’s most prominent internationally distributed art periodical, the artist announced his ambitions to be recognized, even if through an act of theft. “I thought about the rules of the system,” he explained, “and it was clear that they would not put me on the cover, so I thought I might as well do it myself. It was a self-legitimizing action. I went to the printer who works for Giancarlo [Politi, editor of Flash Art] . . . [and] bought a thousand copies that still hadn’t been bound.”111 The ersatz magazine cover, aptly titled Strategies, depicts a triangular house of cards constructed from previous issues of Flash Art. This formal tautology makes a not-too-subtle reference to the navel-gazing rampant in visual-arts coverage. With the precariousness of the depicted structure, it also comments on the sheer ephemerality of fame, that elusive Warholian fifteen minutes for which so many in our culture strive, a young Cattelan being one of them.112

The artist has continued to probe the seductive and coercive powers of the media throughout his career, even suggesting that our culture’s obsession with images, be they broadcast, projected, or printed, is a kind of modern-day idolatry. In a sculpture from 1998 of a taxidermied donkey carrying a TV set (cat. no. 65), Cattelan seems to be commenting on the elision of difference between religion and spectacle culture in today’s media-saturated society.113 Conjuring up imagery of Christ riding a donkey into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, or the traditional Palmesel statues wheeled during the processions marking it, the work suggests that the media is a new kind of godhead, inspiring devotion and sacrifice. It is certainly an opiate of the people, simultaneously sedating and seducing the masses into confusing the phantasmagoric quality of the moving image with the hallucinatory magic of the sacred. The propensity of people to assign an image agency, an imagined subjectivity, is well documented by art historians and cultural theorists.114 Cattelan understands this phenomenon inherently, and while exposing its ethical implications, he exploits its potential to captivate and transform an audience.

The slippage between reality and myth lies at the heart of the artist’s 2001 Hollywood sign project, conceived as an off-site, adjunct exhibition for that year’s Venice Biennale (fig. 35, cat. no. 83). As part of his ongoing investigation of the monument, Cattelan erected a larger-than-life replica of the Los Angeles landmark above the city garbage dump in Palermo, Sicily. In doing so, he transposed an image associated with the dreams of a culture smitten with the movie industry to a completely antithetical locale. On the one hand, according to the artist, the culture of Southern California lives only for the realm of what might happen: “In a way Hollywood and Los Angeles have become what they are by simply erasing their past. They shape their image according to a mirage: they have decided to live in the shadow of the future.”115 The sign itself, which originally spelled out “Hollywoodland” as an advertisement for a real-estate development in 1923, perfectly embodies this liminal position, seamlessly representing the slippage between the fantasized and the actual. It is a sign without a specific referent, suggesting that Hollywood is more of a state of mind than an actual place.116 In contrast, continues Cattelan, Palermo is “a city that has to struggle everyday with its own conception of its past and present.”117 This inversion of realities—a “cut and paste dream”— reveals the inherent contradictions between two radically different cultures, but at the same time it begins to tease out points at which they coincide. It is here that Cattelan’s artwork takes on a hallucinatory quality. Palermo and Los Angeles are both major metropolises, southern in their geographic orientation and relatively parched. Both are stricken with economic problems and urban unrest, with racial tensions in Los Angeles and organized crime in Palermo being defining factors in each city’s public profile. And in fact, like Hollywood, Sicily has captured the imagination of many illustrious feature-film directors, including Michelangelo Antonioni (L’avventura, 1960), Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather, 1972), Roberto Rossellini (Stromboli, terra di dio, 1949), Giuseppe Tornatore (Cinema Paradiso, 1988), and Luchino Visconti (Il gattopardo, 1963). Cattelan’s transposition of the sign to its site in Palermo, where it was visible for all to see, rendered the city a living film set, its inhabitants becoming unwitting participants in a real-time performance with no script or prescribed ending.

In this epically scaled project, Cattelan produced a facsimile of the empirical world with a one-to-one scale relationship between fiction and reality. On the one hand, it invoked the environmental interventions of the earthworks artists—Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, and Robert Smithson, to name a few—and on the other, it indicated a desire to alter the actual through a sustained engagement with the imaginary. Cattelan shares this strategy with a number of his peers, including Gonzalez-Foerster, Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, and Francis Alÿs, who create contemporary myths by shifting the levers of reality ever so slightly. One apt comparison would be Alÿs’s performative project When Faith Moves Mountains (2002), in which some five hundred volunteers armed with shovels formed a line at the end of a massive, 1,600-foot sand dune just outside of Lima, Peru, and began shifting the sand from its original location. The fact that the dune was ultimately moved only about four inches mattered far less than the narrative effect of their unified efforts. With When Faith Moves Mountains, Alÿs created a profound allegory about the potential of collective human will, a grand tale that would circulate for generations. Cattelan understood this to be the underlying implication of his gesture in Palermo. He knew he was creating a story that would have broad cultural reverberations. “The best art works live in your head,” he explained. “They must carry something that produces information, something that triggers your attention and stays with you. . . . I think the best art works have always . . . [carried] the germ of a story, something that grows and changes as you pass it along to others.”118

The catalogue for the Hollywood sign project, itself a cunning act of appropriation, generated a similar confusion over competing realities. To create the book, the artist simply replaced the jacket of Vanity Fair’s Hollywood—a coffee-table tome from 2000 replete with full-color photographs of movie stars by Cecil Beaton, Horst P. Horst, David LaChapelle, Annie Leibovitz, Helmut Newton, and Bruce Weber, among others—with one featuring an image of his ersatz sign. The back-cover flap provided the only clue to Cattelan’s involvement, with its list of Palermo project credits, Biennale di Venezia stamp, and thumbnail-size installation shots. This propensity for theft, well documented in this essay and elsewhere, extends even to interviews: he has been known to respond to writers’ questions with answers pilfered from already-published discussions with other artists. Himself a champion of the interview format, he has conducted many Q & As with both the living and the dead. Published largely but not exclusively in Flash Art, these dialogues form an interesting sidebar to Cattelan’s practice, indicating a well-informed appreciation for a younger generation of artists, which includes Hernan Bas, Guy Ben-Ner, Paul Chan, Seth Price, Tino Sehgal, and Andro Wekua, among others. As with all of his work, Cattelan collaborates with behind-the-scenes assistants to construct the conversations, often inviting the artists themselves to create and respond to their own questions. In the case of deceased artists, like Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Pino Pascali, the answers are culled from previous interviews and recombined with fresh questions to create something that is simultaneously old and new.

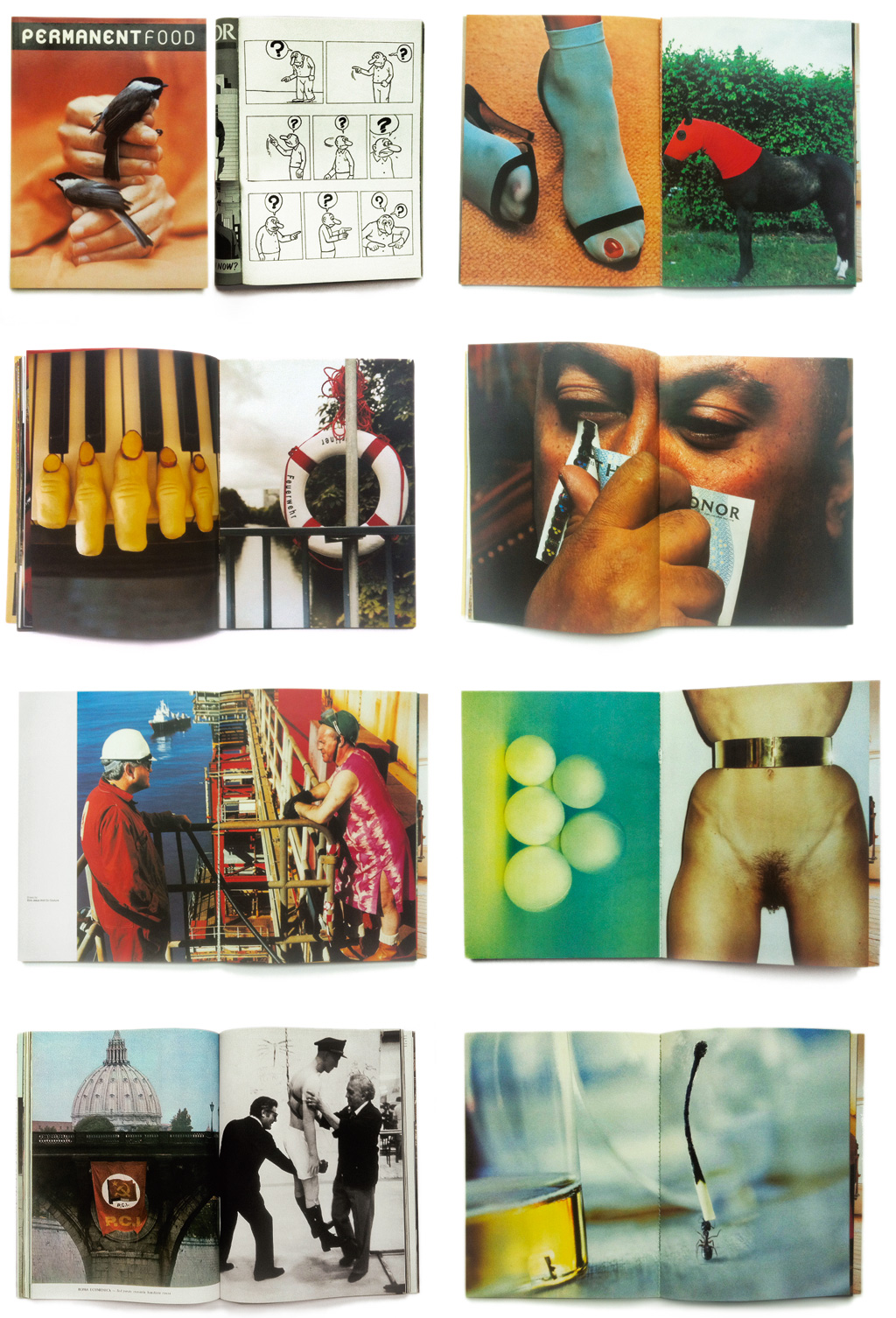

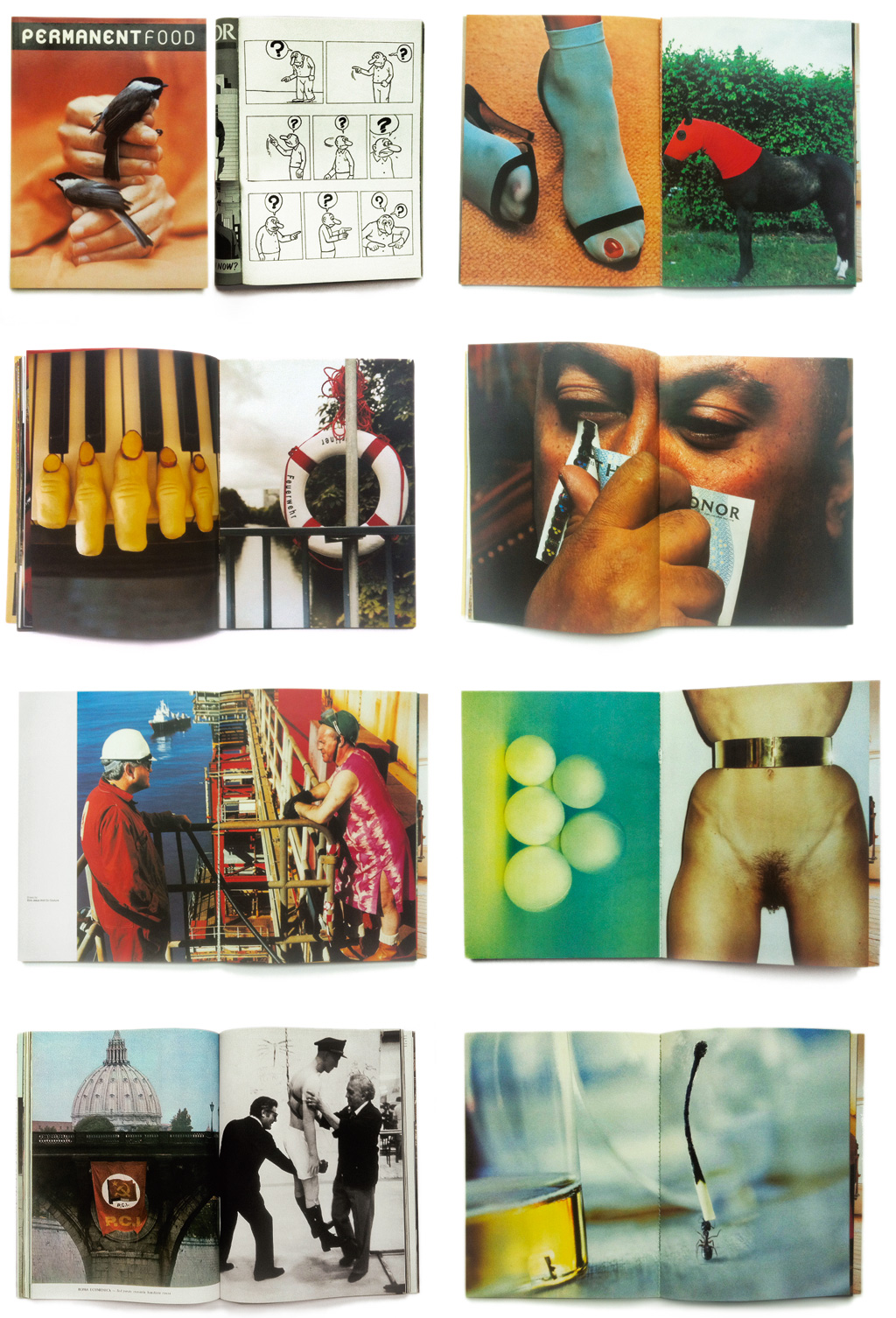

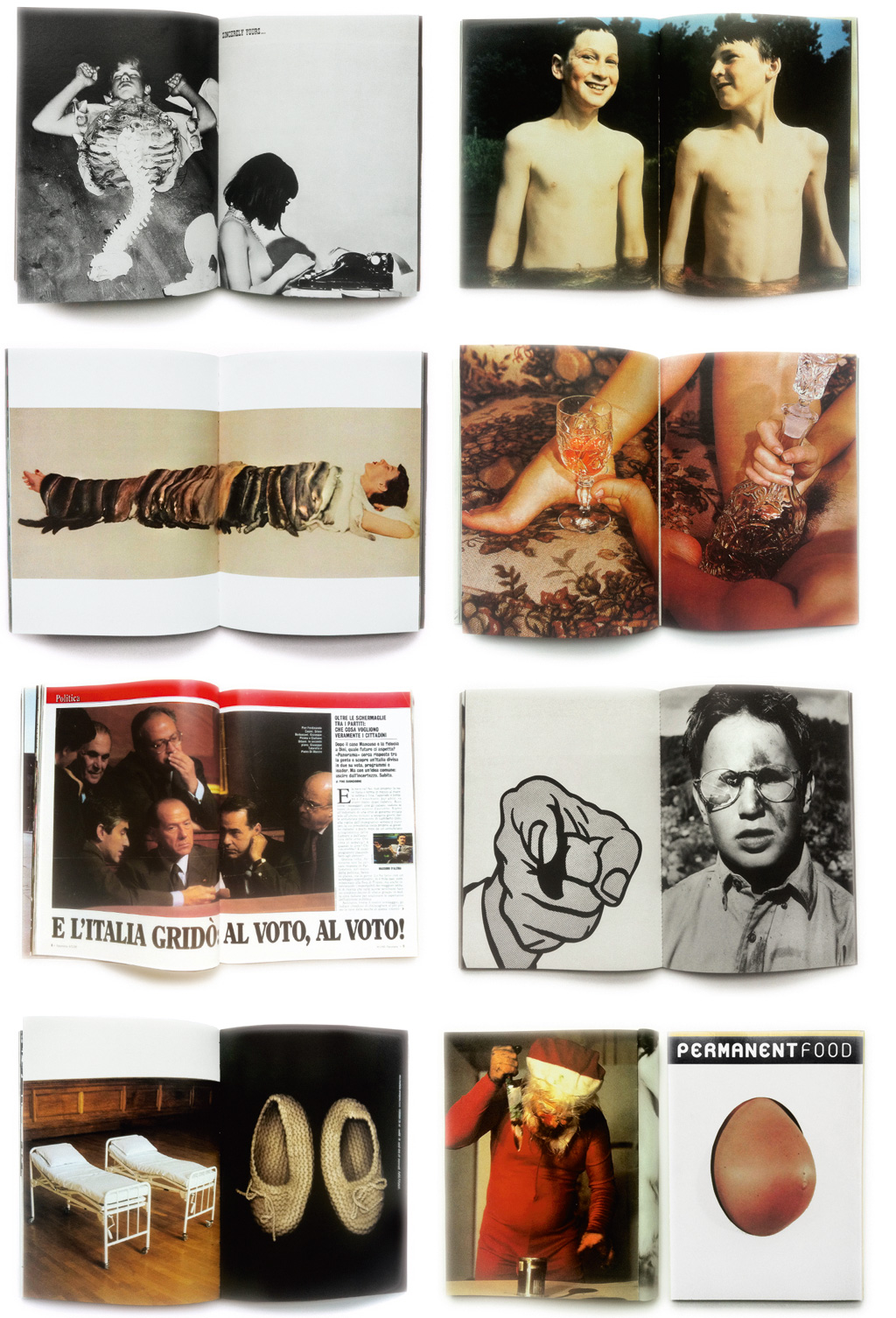

Cattelan’s obsession with print media and his appropriative tendencies brilliantly intersect in the magazine Permanent Food, which he founded in 1995 with Gonzalez-Foerster and has edited ever since (figs. 36–37). It is now in its fifteenth issue. The publication comprises pages lifted from thousands of magazines around the world, making it, as critic Vince Aletti has described it, the perfect postmodern periodical.119 Initially, the magazine came together collectively; its early issues comprised pages ripped out of other periodicals and sent in by friends and colleagues. “Permanent was a magazine with no style or personality,” Cattelan has explained, “simply because any style was available, any personality interchangeable.”120 In its collective mentality, therefore, Permanent Food celebrates the postauthorial condition and the idea that content can be generated communally.121 The multiplicity of perspectives available contributes to a truly eclectic publication, which is edited to underscore the uncanny and often grotesque imagery at hand. Oscillating between the slick, seductive look of fashion photography and the gruesome exhibitionism of cult journals, Permanent Food refuses to behave. After the first few issues, Cattelan and his new collaborator, Paola Manfrin, an art director and image consultant in Milan, took over the selection process, but the freewheeling quality of their purloined source material has remained intact. A magpie of the image world, Cattelan has cut out, scanned, or downloaded pages from every conceivable source, which, when isolated from their original contexts and juxtaposed with others, begin to radiate new meaning. His macabre sensibility is present throughout, as is his corresponding appreciation for the odd, the sensual, and the silly. The magazine has no text other than its title and that which might appear on any one of its pilfered pages. Accordingly, Permanent Food is not for reading but rather for the sheer visual delectation of random imagery deftly edited to create a most seductive rhythm of the unpredictable and the inappropriate. Described by Cattelan as a “second generation magazine,” it is, he claims, without copyright, a free zone for his and Manfrin’s irreverent virtuoso experiments with our mediated culture.122

fig. 36

Cover of Permanent Food 9 (2003)

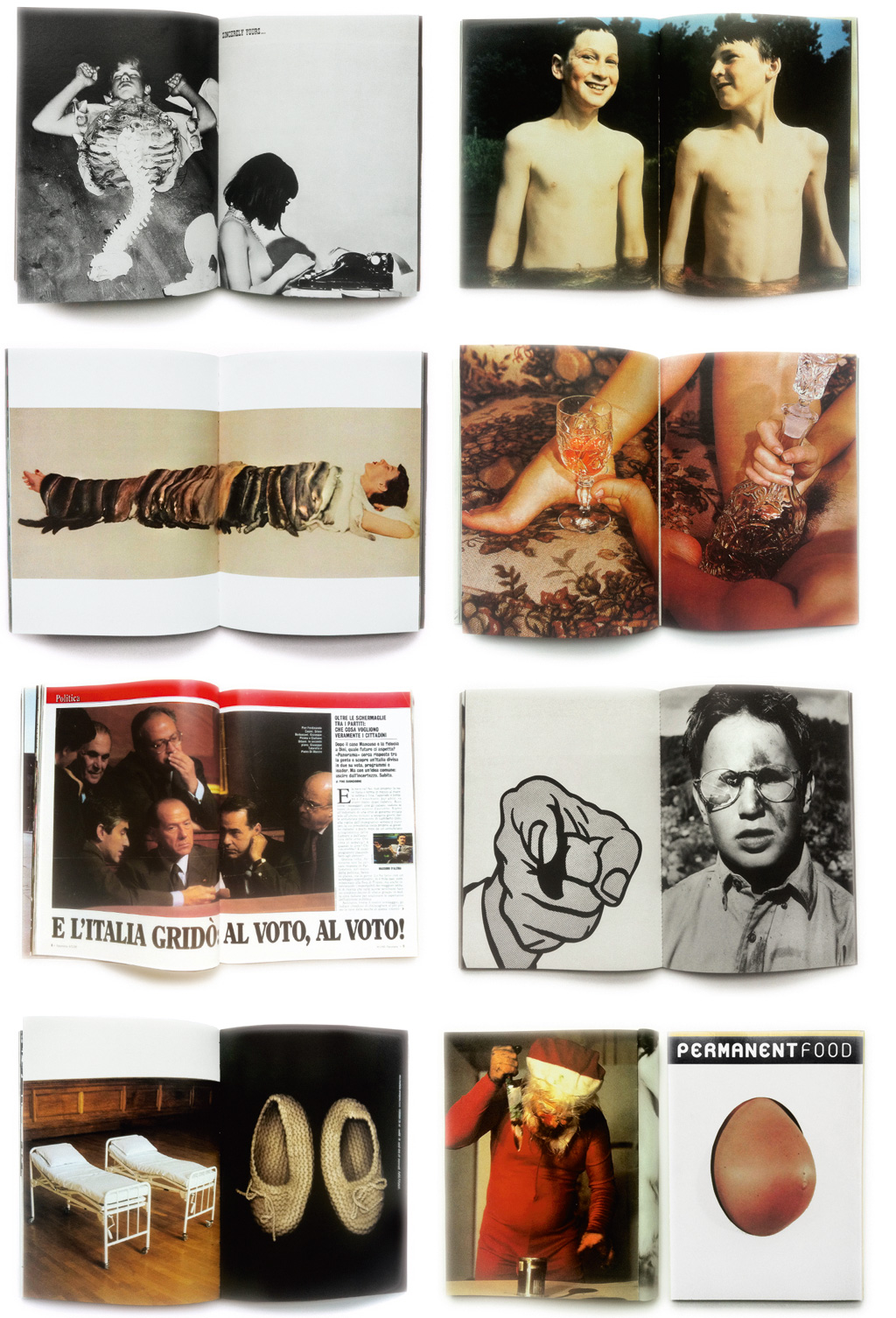

fig. 37

Covers and interior spreads from Permanent Food, 1997–2007

Cattelan founded Permanent Food because, he has claimed, he wanted to have his own magazine, just like he had wanted to have his own soccer team.123 Artist-run magazines certainly have a place in art history. The Surrealists, for instance, published journals like Minotaure (1933–39) or La révolution surréaliste (1924–29), as did Dadaists like Francis Picabia, who produced the satirical 391 (1917–24). Though quite different in content, perhaps the closest historical correlate, with its focus on popular culture in all mediums and its undeniable flirtation with the cool, is Andy Warhol’s Interview, founded in 1969. Cattelan has professed his admiration for Warhol on many occasions, identifying with the American artist’s entrepreneurial spirit and cultural ubiquity. “We live in a Warhol world as much as we live in the city of the Empire State Building,” he has explained. “He’s something we can’t avoid but also something we don’t need to think about. That’s probably the greatest thing about Warhol: the way he penetrated and summarized our world, to the point that distinguishing between him and our everyday life is basically impossible, and in any case useless.”124 Indeed, Warhol was an artist who intrinsically understood the power of the image, no matter how mundane or sensationalistic it may be. Whether a soup can or car crash or celebrity portrait, Warhol’s pictures reflect the broad surface of postwar American culture. For Cattelan, it was Warhol’s capacity to pinpoint the very icons of contemporary society—the Coca-Cola bottle, a weeping Jackie Kennedy—that earned him a place in the artist’s pantheon of patron saints. The multidisciplinary nature of his artistic universe—Warhol was known as a visual artist, cult star, TV producer, publisher, filmmaker, author, producer, and collector—has also no doubt inspired Cattelan in pursuing his own “extracurricular” activities in the cultural realm.125

In addition to Permanent Food, with its parasitic relationship to pop culture, Cattelan produces another publication called Charley (fig. 38), which is more directly focused on the mechanics and machinations of the art world. In this way, it is an insular, incestuous affair that plays on familiarity and cronyism. Cattelan edits Charley with a pair of art-world insiders: Ali Subotnick, as of this writing Adjunct Curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and Massimiliano Gioni, Associate Director and Director of Exhibitions at the New Museum in New York.126 Unlike Permanent Food, Charley transforms itself in format, style, and substance for each installment, of which there are currently six in circulation. For the inaugural issue, published in spring 2002, the editors invited more than seventy curators, artists, and critics (including Jan Avgikos, Carlos Basualdo, Bice Curiger, Kasper König, Glenn Ligon, Akiko Miyake, Beatrix Ruf, and Rirkrit Tiravanija, among other notables) to identify their choices of the best emerging artists. Each new talent—including such then up-and-coming artists as Christoph Büchel, Trisha Donnelly, Mark Leckey, Rivane Neuenschwander, and Roman Ondák—was represented by a page torn from another magazine showing one image of his or her work. In a deliberately crude layout conceived by Conny Purtill (who has designed all the Charleys), these appropriated pages were all photographed from above on the same concrete studio floor, creating a rough gray frame for each of the images. The second Charley, published in fall 2002, comprises 142 unbound color postcards that collectively provide a “snapshot of the New York City art season from fall 2001 through summer 2002, featuring over 140 exhibitions and events.” The editors described the compilation of cards as the perfect “play list,” which, because of their imprimatur, will take on increased importance over time. Cattelan’s support of other artists, his peers as well as the young and the overlooked, is sincere. While Charley may have an ironic edge, given its parody of our cultural obsession with list making and ranking, his goal is to use the art world to expand on and crack open its system of inclusion and exclusion. The magazine celebrates both success and failure, revealing how precarious and elusive the distinction between them can be. Charley 03 (2003), for instance, focused on one hundred artists whose careers seemed most promising during the 1980s and 1990s but who, for one reason or another, had fallen out of favor. As with the previous issue, the artists are each represented by a rephotographed catalogue or magazine page of their work, showing them at their perceived apex. This issue, more than the others, testifies to the fickleness of taste and the cruelty of history. With its archaeological bent, Charley 03 reclaims a semiforgotten past while ironically relegating the artists it includes to a second-rate status. One’s presence in the publication can be interpreted as either a rediscovery or a reinforcement of rejection, depending on the reader’s perspective.

fig. 38

Cover of Charley 05 (2007)

Charley 04 (2006), otherwise titled Checkpoint Charley, was published on the occasion of the 4th Berlin Biennial, which was curated by the three editors, Cattelan, Gioni, and Subotnick. As a complement to the catalogue they produced for the exhibition, this generously sized softcover book includes an image of work by the more than seven hundred artists they had considered for the show through studio visits, recommendations, or their own existing knowledge base. This attempt at egalitarianism shares the true Charley spirit, where inclusion signals some form of elimination, or rejection earns inclusion. Charley 05 (2007), in contrast, focuses on the perpetually excluded, artists whose careers have hovered on the very periphery of public awareness. Considered outsiders, visionaries, or freaks, these artists have often toiled in obscurity for decades, their work garnering attention only after their deaths. Others have operated within the system, but the prophetic nature of their practices has remained unappreciated or misunderstood. And as with previous issues, the material is all appropriated, with biographical texts downloaded largely from Wikipedia. No one ever agrees to be featured in Charley. With the exception of the first two volumes, it is a dubious distinction at best.127

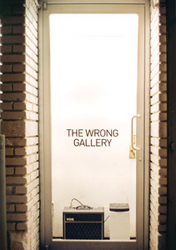

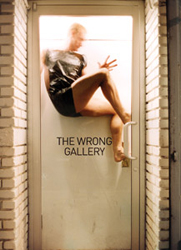

Cattelan’s Warholian extension of his practice into other modes of cultural production was catalyzed by his association with Gioni and Subotnick. This team of three, which organized the aforementioned Berlin Biennial to great critical acclaim, began their collaborative curatorial activities in 2002 with the founding of the Wrong Gallery (fig. 39). Created in reaction to what they perceived to be a lack of experimentation in the New York art world, they opened their own “alternative” space—a glass door with approximately one square foot of exhibition area behind it.128 The “gallery” was expressly not for profit and ran on a shoestring budget supplemented by a lot of good will from artists and fellow gallery owners.129 Located on West Twentieth Street in the heart of the Chelsea gallery district—a kind of urban mall of competing commercial art spaces—the Wrong Gallery showcased over a period of five years the work of forty international artists, who in some cases had no other representation in New York. Their roster, which included such up-and-coming talents as Tomma Abts, Paweł Althamer, Cameron Jamie, Adam McEwen, and Paola Pivi, as well as established artists like Isa Genzken, Paul McCarthy, and Lawrence Weiner, quickly propelled the enterprise into an unanticipated, most likely undesired realm of art-world respectability. What began as a bit of a joke or an attempt, according to Cattelan, to simply have some fun, evolved into something rather serious. Over the course of its existence, the Wrong Gallery morphed into a high-gear production company, making appearances at the Whitney Biennial in 2006 and at four Frieze Art Fairs with provocative, even scandalous interventions, including a 2006 reenactment of Italian artist Gino De Dominicis’s 1972 performance Seconda soluzione di immortalità: L’universo è immobile (Second solution of immortality: the universe is immobile), in which a man with Down syndrome stares in silence at a stone, a sphere, and an imaginary cube.130 Prior to that, they had presented a work by Sehgal in which children enacted an archive of his situation-based art and offered it for sale (2003); a performance by Pivi involving fifty identically dressed Chinese men and women all staring into space (2005); and a work by Noritoshi Hirakawa that quite literally revealed the results of his dietarily based efforts to produce scent-free excrement (2004).131 By 2005, when the Wrong Gallery took up shop at Tate Modern in London for some two years after its lease expired in New York, it had become an art-world brand, recognized for its radical curatorial perspective and Cattelanesque penchant for trouble. The team even created a miniature version of its doorfront gallery, complete with souvenir-sized artworks, evoking Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (1935–41).132 The idea was to “provide a kind of DIY gallery for people to create their own extended exhibition programs” on a very personal scale.133

fig. 39

Performance and exhibitions at the Wrong Gallery, New York. Clockwise from top left: Daniel Squires, Merce Cunningham Dance Company, November 15, 2002; Phil Collins, Sinisa and Sanja, November 21–December 10, 2002; Martin Creed, Work No. 122: All the sounds on a drum machine, October 12–November 16, 2002; Paul McCarthy and Jason Rhoades, Humpback (The Fifth Day of Christmas) (from 13 Days of Christmas Shit Plugs), December 12, 2002–January 17, 2003

Many have viewed Cattelan’s forays into publishing and curating as an escape from his career as an artist, a professed source of ongoing anxiety. In fact, rumors circulated during the Berlin Biennial that he had retired from object making to focus exclusively on these other, seemingly tangential activities, as if they somehow precluded his making “real art” or vice versa. It can be argued, instead, that his magazines and curatorial projects—all achieved collaboratively—represent an expanded art practice, one that time and again returns to the power of the image. Both Permanent Food and Charley exist only as photographic documents; the reproducible image is part of their very DNA. And the aim of exhibition making, while an activity in real space, is often to create a memorable tableau, an image that will remain burned onto the retinas of receptive visitors. In recent years, Cattelan has expressed his preference for choosing and arranging over making, however blasphemous that may still sound for a visual artist, even in 2011. He is less interested in production of the new than in collecting and collating already-existing material. His medium resides at the core of our spectacle culture—the countless images that drive our collective obsessions, desires, and fears, now ever-available to be downloaded or scanned and recycled at will.134

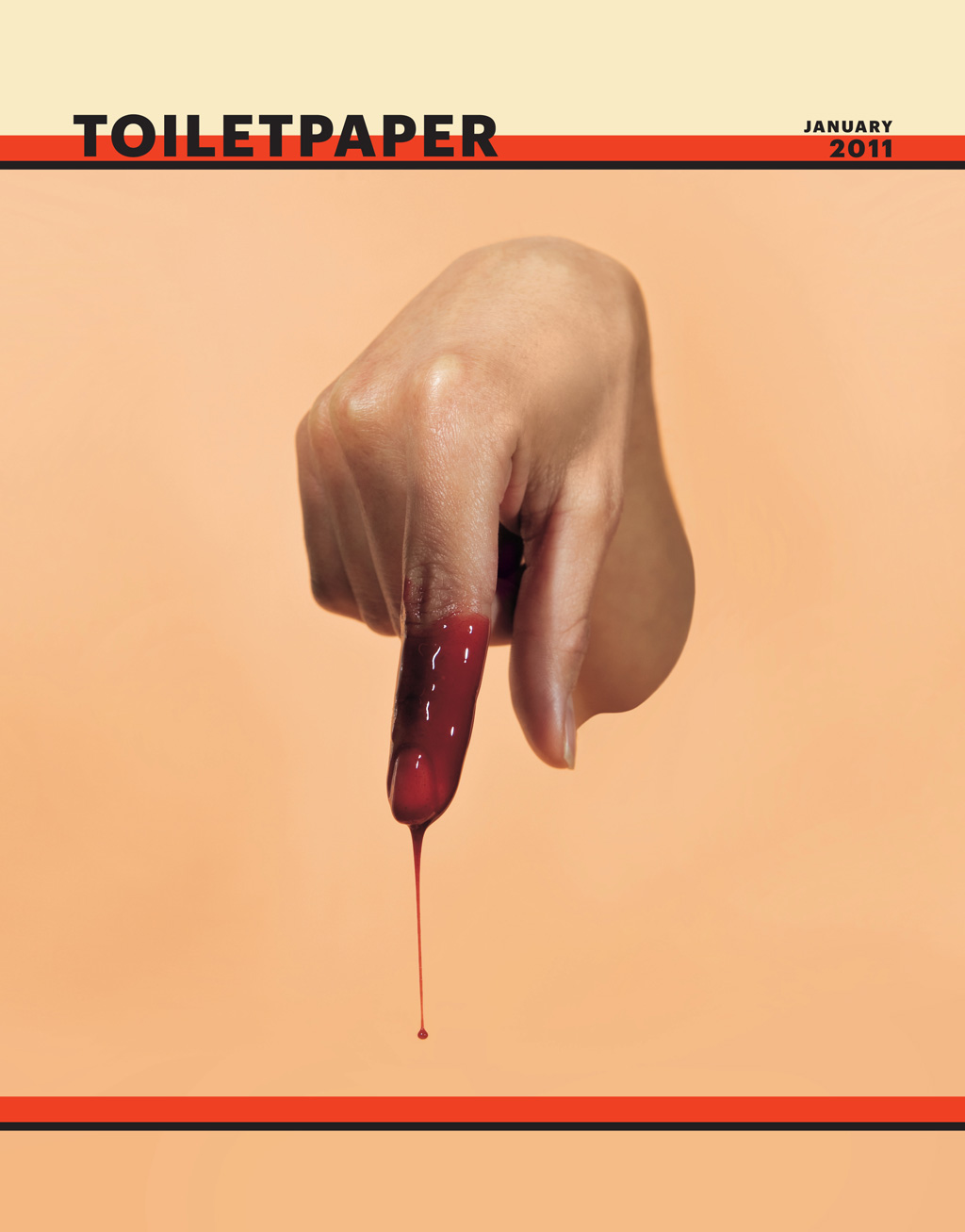

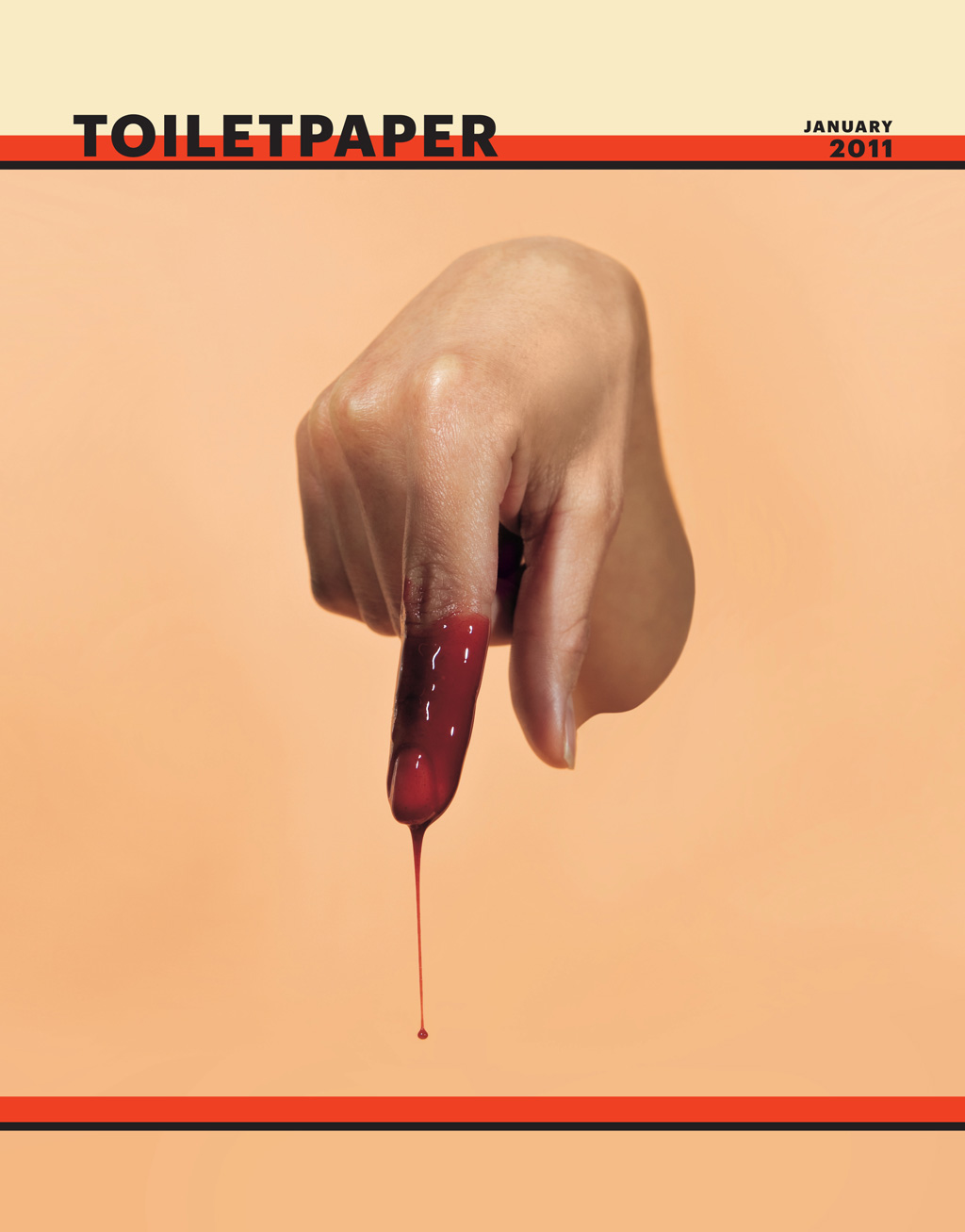

Cattelan’s ongoing absorption into the photographic vocabulary of everyday life has found an outlet in his latest publishing project, one that, surprisingly, inverts the logic of his previous, appropriated magazines. Called Toilet Paper after the ultimate disposability of print journalism, the periodical has been cocreated with the Italian fashion photographer Pierpaolo Ferrari, who worked with Cattelan on a visually riveting set of spreads featuring Linda Evangelista for W magazine’s art issue in 2009.135 Unlike its antecedents, Toilet Paper is a “first-generation” magazine—all of its photographs have been imagined, constructed, art directed, and shot expressly for the publication (figs. 40–41). Everything, it seems, is original. A nun (or is it a man in nun drag?) shoots up; a woman seen from the waist down cuts an aloe plant with sharp scissors; a blindfolded woman plays the imaginary keys of a piano seen behind her; a young brunette licks a doorknob; a woman dangles from a noose with a stopwatch affixed to her ankle. Linked by an underlying surrealist valence, the pictures probe the unconscious, tapping into sublimated perversions and spasms of violence. The images oscillate between noirish black-and-white and full-throttle color, evoking genres as wide ranging as early-twentieth-century spiritualist photography, slick fashion shoots, Japanese horror films, and annual-report-style portraiture. While Cattelan here declines to hijack photographs from our contemporary image world, he is instead stealing our memories of them: these are pictures we swear we have seen before but just can’t place. Was it this movie or that advertisement, this sitcom or that fashion spread? To some extent, the images in Toilet Paper look like those in Permanent Food but “brought to life.” Interestingly, this effect is enhanced on the magazine’s website, where a few of the photographs exist in video format, with the models shown moving into position while uncannily making eye contact with the viewer.136

fig. 40

Cover of Toilet Paper, no. 2 (January 2011)

Larger in size and much thinner than the perfect-bound Permanent Food, the staple-bound Toilet Paper feels far more disposable than its predecessors. This is ironic, given how elaborately each of the twenty-two images in the first issue have been staged. And while the pictures certainly feature a few recurring motifs—disembodied body parts, for example—their great visual variety indicates the amount of effort expended to create so many distinct photographic universes. A correlation can be made between Cattelan’s art-directed pictures for Toilet Paper, which call to mind the construction of detailed movie sets, and Gregory Crewdson’s intricately designed cinematic tableaux. But the difference is very telling. Crewdson’s photographs are framed and exhibited, produced in editions, bought, and sold; unquestionably they are to be considered artworks. Cattelan’s Toilet Paper pictures exist only in magazine format, a medium that can be endlessly circulated but is more likely to be thrown away. After all, the shelf life of a magazine is rather brief. Cattelan considers the images he produces for Toilet Paper to be “almost art.” Some, he thinks, may eventually be elevated to the rank of art but not until they have proven themselves in the world: not until they have become iconic.

fig. 41

Interior spread from Toilet Paper, no. 2 (January 2011)

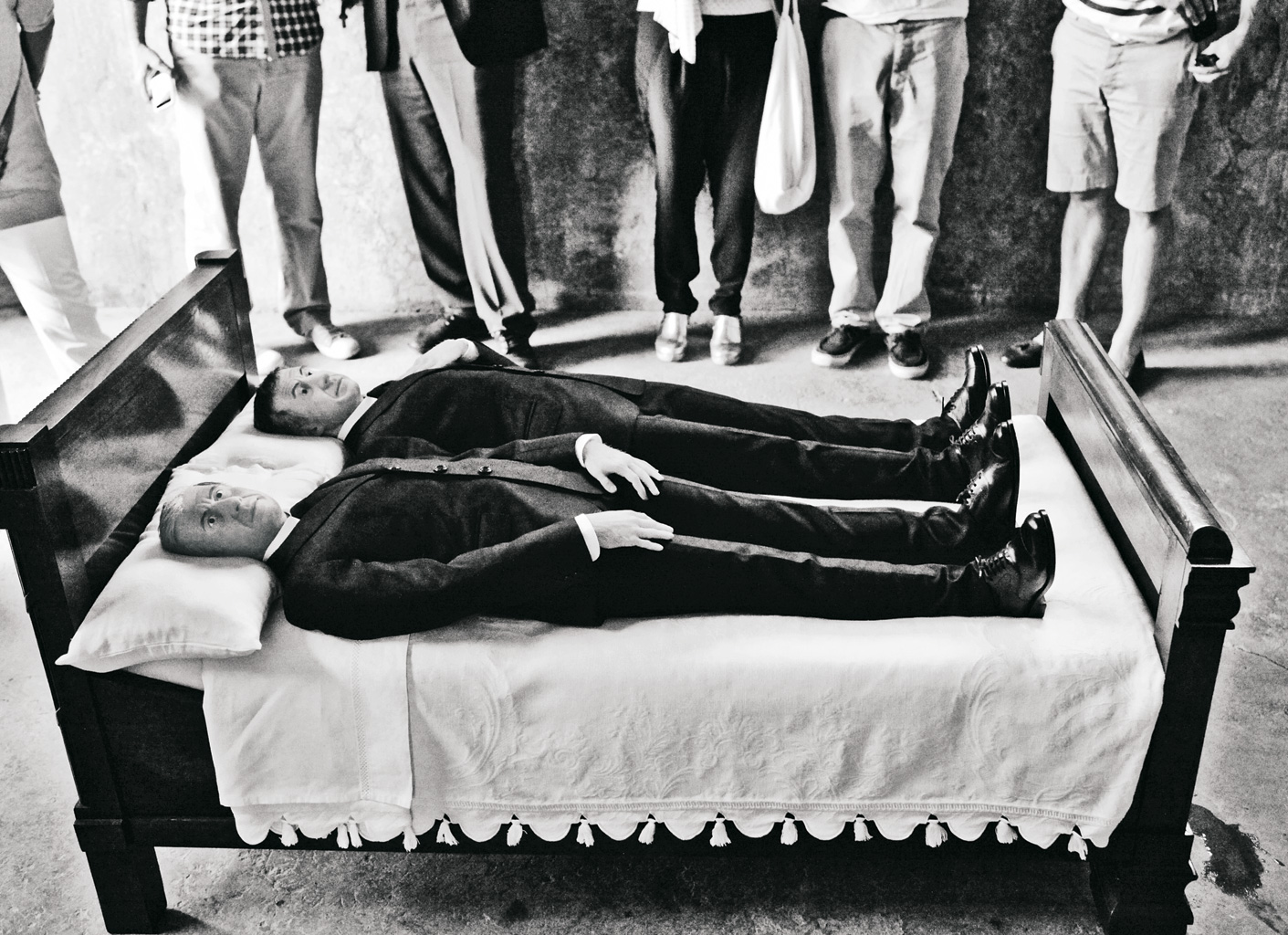

Toilet Paper is a vehicle for retreat. It offers Cattelan a chance to test the success of his constructed photographs in the public sphere without the pressures of the art market’s demand for salable objects. Cattelan’s shift from notorious picture thief to respected art director is new. While it may eventually force a reinterpretation of his practice, it now simply cements the centrality of the mass-mediated image in his work. Cattelan’s obsession with finding—or now making—and disseminating the unforgettable picture ultimately defines the trajectory of his art. Cattelan’s recent work We (2010, fig. 42, cat. no. 110), a double self-portrait, playfully rehearses the reproducibility of the photograph in sculptural form. Exhibited in Greek collector Dakis Joannou’s repurposed slaughterhouse on the isle of Hydra, the piece comprises two virtually identical effigies of the artist lying next to one another in a double bed. Fully dressed in the finest of Italian suits, one blue and one black, these figures are slightly smaller than the artist. They are almost child size yet emphatically adult, like his portrayal of Hitler. One of the mini-Cattelans, with hand over heart, glances at his twin. Is it with surprise, complicity, or affection? It is difficult to say. Whatever its intended meaning—and there is certainly more than one possible reading—the piece resonates with multiple insider art references. Perhaps We is a mock tribute to Gilbert and George, the always-suited English artists, forever joined together in their performative partnership. Or it is a teasing of Robert Gober, whose sculpted beds and cribs function as platforms for psychological anguish in a register quite different from Cattelan’s? Or maybe it is an homage to Alighiero e Boetti, the Italian Conceptual artist who always referred to himself as two.137 Cattelan, who often professes his admiration for Boetti, has his own habit of describing himself in the plural, using the royal “we” when discussing his thoughts and actions. This quirk may be in deference to the fact that behind any one of his projects is a team of collaborators. But it might point to an inherent artistic schizophrenia, which allows Cattelan his deep delving into popular culture while sustaining his role as a “fine” artist.

The twinned figures—an image and its copy—suggest a sculptural analogue to photography, with its capacity for endless mechanical reproduction. And despite its ability to record any fleeting moment of lived reality, the photograph has been theorized as a portent of death. Perhaps most poignantly articulated by Barthes in his meditation on photography Camera Lucida, photography’s correlation with mortality is deep and multivalent. Present in every photograph, claimed the author, is “the return of the dead,” an inescapable reminder that whatever was recorded by the camera no longer exists in the state pictured; the moment rendered is forever vanished, save for a fading image. And the photograph unnervingly predicts the future. Perusing an old photo of a young prisoner sentenced to death, Barthes notes that the man “is going to die.” This reality is inherent to all photography, a medium that simultaneously imparts both “this has been” and “this will be.” Barthes perceives in this photograph an “anterior future of which death is the stake,” a past that is yet to come.138 Might We then be read as a funereal image, a portrait of the artist contemplating his doppelgänger, his uncanny clone as sign of his demise? With a culminating air, the sculpture brings together three strands within the artist’s oeuvre: the self-portrait as cipher for the human condition, the inevitability of death, and the power of the image to seduce and horrify with this existential truth.

NOTES

“I’ll Be Right Back: An Interview with Maurizio Cattelan,” by Jan Estep, New Art Examiner 29, no. 4 (March–April 2002), p. 40.

This point was made by Gioni in “Maurizio Cattelan—Rebel with a Pose,” p. 180.

Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (1967), Thesis 1. My essay cites the 2002 translation by Ken Knabb, available on the website Bureau of Public Secrets, www.bopsecrets.org/SI/debord/index.htm, accessed February 3, 2011. For an earlier and less agile translation, see the 1977 version published by Black & Red Press (Detroit).

Ibid., Thesis 5.

Pierre Huyghe, Cattelan’s peer and collaborator in the 1990s, explained his generation’s investment in the spectacle, in an interview with George Baker. He stated that “we must dispel one received idea and that is the spectacle is a fatalism, inherently alienating. The spectacle is a format, it is a way to do things. It is a ‘how.’ This ‘how’ is a tool, not an allegory.” See Baker, “An Interview with Pierre Huyghe,” October 110 (Fall 2004), p. 104.

“Maurizio Cattelan,” interview with Caroline Corbetta, Klat, no. 2 (Spring 2010), p. 44.

With the proliferation of media outlets, the emergence of reality TV, and the appearance of social-media sites on the Internet, access to “fame”—or at least notoriety—has become increasingly within reach of the average individual, creating a new kind of cultural obsession. See my essay “Fifteen Minutes Is No Longer Enough,” in Monument to Now: The Dakis Joannou Collection (Athens: Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art, 2004), pp. 364–417.

The title is If a Tree Falls in the Forest and There is no One Around it, Does it Make a Sound?

See Freedberg, The Power of Images, pp. 379–81 and 384–85, and W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), pp. 28–56.

Quoted in Mark Sanders, “Maurizio Cattelan,” Dazed and Confused, no. 81 (September 2001), p. 185.

See Edward Dimendberg, “The Kinetic Icon: Reyner Banham on Los Angeles as Mobile Metropolis,” Urban History 33, no. 1 (2006), pp. 106–25, http://journals.cambridge.org/fulltext_content/supplementary/Urban_Icons/atlas/content/06_dimendberg.htm. To quote Dimendberg, “The Hollywood sign, constructed atop Mt. Lee in 1923, is a . . . candidate for selection as urban icon. Yet its intended purpose as an advertisement for the Hollywoodland real estate development lacks a direct connection to the entertainment industry, and the neighbourhood of Hollywood is only one of many in the city. Pundits may well argue that this absence of a referent, a sign that is just a sign, perfectly captures the notion that Hollywood is less a physical place than a state of mind, if not a veil of deception. The entertainment industry with which Hollywood has become synonymous is itself widely dispersed throughout the region. . . . Whether measured in relation to its economic significance to the region, or considered with respect to the foreign ownership of studios such as Sony, the movie business is not Los Angeles, and Los Angeles is more than the movie business.”

Quoted in “Maurizio Cattelan,” interview with Mark Sanders, p. 185.

Quoted in ibid.

Vince Aletti, “Hunting and Gathering: Plundering the Image Bank with Cattelan and Feldmann,” Village Voice, April 16, 2002, http://www.villagevoice.com/content/printVersion/169297.

Quoted in ibid.

On this note, see Emily King, “Fantasy Publishing: Maurizio Cattelan’s Publication Permanent Food,” 032c, no. 8 (Winter 2004–05), pp. 128–31, http://032c.com/2004/fantasy-publishing.

Inserted into a contents page borrowed from Numéro magazine in Permanent Food, no. 8 (2000/2001) is the following note: “Permanent Food is a non-profit magazine with a selection of pages taken from magazines all over the word [sic]. Permanent Food is a second generation magazine with a free copyright.”

See King, “Fantasy Publishing.”

Cattelan, as told to Katy Siegel, “Army of One,” Artforum International 43, no. 2 (October 2004), p. 148.

Cattelan discussed his appreciation for Warhol’s eclectic practice in ibid., p. 149: “Warhol’s work is not about a specific decade or style; it’s about being contemporary, being now. And there’s so much work, and there are so many different forms of expression—paintings, portraits, music, films, performances, studios, Polaroids, tapes—that you can always find something that’s both pure Warhol and perfectly timed for your present moment.”

Bettina Funcke, formally an editor at Dia Art Foundation and at the time of this writing Head of Publications for Documenta 13, collaborated with the group on the first issue in 2002. Cattelan’s associates have risen within the ranks of the art world since they began work on the first Charley: Gioni was an editor at Flash Art and Subotnick worked at Parkett magazine.

The most recent Charley publication was produced to accompany No Soul for Sale—A Festival of Independents at Tate Modern, London, in 2010, which was organized by Cattelan along with Cecilia Alemani, Gioni, and Subotnick. The project, which took the guise of an art fair, brought together more than eighty nonprofit spaces and artists’ collectives from around the world to showcase new forms of distribution and engagement. The publication, Charley Independents, documents each participant.

The address of the original Wrong Gallery was 516A1/2 West Twentieth Street. They opened a second “doorfront” gallery, which had an exhibition space with a depth of approximately two feet, at 520A1/2 West Twentieth Street.

The gallery was not officially not-for-profit, i.e., incorporated as a not-for-profit corporation under U.S. law. It simply did not make any money from gallery exhibitions.

When exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1972, this performance created quite the scandal and remained on view for only a few hours. The Vatican decried the work, claiming it “destroyed any credibility of art and offended human reason.” On the other end of the political spectrum, Pier Paolo Pasolini denounced De Dominicis as being “an accomplice of the repressive ideology of capitalism.” For quotes, see Anna Somers Cocks, “Wrong Gallery re-enacts 1972 performance which outraged Italy and the Vatican,” Art Newspaper, October 11, 2006, http://www.theartnewspaper.com/fairs/frieze/2006/FRIEZE06_issue1.pdf.

The works are Sehgal, This is right; Pivi, 100 Chinese; and Hirakawa, The Homecoming of Navel Strings.

Published by Cereal Art, the multiple was created at a 1:6 scale of the original in an edition of 1,000. See http://www.cerealart.com/shopexd.asp?id=423, accessed February 10, 2011.

Cattelan in conversation with the author, February 28, 2011.

So far, Cattelan has been lucky in that all the artists, photographers, editors, publishers, and advertising agencies whose work has been borrowed have respected his claim for copyright independence (or have remained unaware of his practice). Like a computer hacker, he treats visual culture as entirely open-source material to be exploited for his own use. Appropriation artists like Jeff Koons and Richard Prince have faced damaging copyright-infringement lawsuits that bring to the fore how one defines “fair use” under the law.

“Maurizio Cattelan,” W 38, no. 11 (November 2009), pp. 110–33.

See http://www.toiletpapermagazine.com, accessed February 10, 2011. Cattelan’s turn to video suggests a possible new, uncharted direction in his work.

This would not be the first homage to Boetti in Cattelan’s oeuvre. His untitled 1998 sculpture of a live olive tree embedded in an enormous cube of earth (cat. no. 66), realized for Manifesta 2 in Luxembourg, was a manifestation of Boetti’s unrealized Monumento all’agricoltura (Monument to agriculture, 1970). For details, see Barbara Vanderlinden, “Untitled, Manifesta 2,” in Maurizio Cattelan (2003), pp. 90–97.

Barthes, Camera Lucida, p. 96.