The Boone and Crockett Club’s big-game records keeping deals only with certain native North American big game animals. For such purposes, the southern boundary is defined as the south boundary of Mexico. Only cougar, jaguar, and whitetail deer of the recognized trophy categories range south of this boundary, and only the first two reach recordable size south of Mexico. The northern limit for trophies such as polar bear and walrus is the limit of the continent and associated waters held by the United States, Canada, or Greenland. Continental limits and held waters define east and west boundaries for all categories.

A number of species show geographical variation so that there are smaller varieties inhabiting some parts of the continent and larger ones elsewhere. For example, mature moose from Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, etc., of the Shiras’ variety, although they may grow large and beautiful racks, are unable to compete with the monstrous moose from the Alaska-Yukon region. So it has been necessary to break up the total ranges of some of the species into various categories in order to provide proper recognition.

The Records Committee has, over the years, gradually defined the areas from which trophies may be entered and has modified these boundaries in some cases when more thorough knowledge of the distribution of the animals in question has become known. The Committee creates new categories from time to time. Other new trophy categories have been proposed, but the Committee maintains a conservative stance in reviewing such proposals. New categories are considered only when the following conditions are met:

1) there are extensive geographical areas where the proposed animals occur,

2) the animals occur in good numbers,

3) there are suitable boundaries that can be drawn, and

4) the game department(s) managing the proposed class are in favor of setting up such a new category.

The following material will review the categories for which there are geographically defined boundaries. Obviously these boundaries must be observed in the taking of a trophy in order for it to be considered for that category. As a general rule, the categories are set so there is virtually no chance of a larger category specimen (or a cross-bred animal) being taken within the boundary for the smaller category. While this may exclude some deserving specimens of the smaller category that are resident in the larger category’s range, it is a price that must be paid to keep the smaller categories pure.

The bigger brown bears are found on Kodiak and Afognak Islands, the Alaska Peninsula, and eastward and southeastward along the coast of Alaska. The smaller interior grizzly is found in the remaining parts of the continent. The boundary between the two was first defined as an imaginary line extending 75 miles inland from the coast of Alaska. Later this boundary was more precisely defined (figure 2-A) with the current definition as follows:

A line of separation between the larger growing coastal brown bear and the smaller interior grizzly has been developed such that west and south of this line (to and including Unimak Island) bear trophies are recorded as Alaska brown bear. North and east of this line, bear trophies are recorded as grizzly bear. The boundary line description is as follows: Starting at Pearse Canal and following the Canadian-Alaskan boundary northwesterly to Mt. St. Elias on the 141 degree meridian; thence north along the Canadian-Alaskan boundary to Mt. Natazhat; thence west northwest along the divide of the Wrangell Range to Mt. Jarvis at the western end of the Wrangell Range; thence north along the divide of the Mentasta Range to Mentasta Pass; thence in a general westerly direction along the divide of the Alaska Range to Houston Pass; thence westerly following the 62nd parallel of latitude to the Bering Sea.

Polar bear must be taken in either United States or Canadian-held water and/or land mass in order to be eligible. This definition is necessary because of the wide range of polar bears in the far northern hemisphere.

Jaguar must be taken north of the south boundary of Mexico (the southern boundary of North America for big-game records-keeping purposes) in order to be eligible.

To be eligible for entry, walrus trophies must be taken within U.S., Canadian, or Greenland waters and/or land areas. The geographical boundary for Pacific walrus is that portion of the Bering Sea east of the International Dateline; south along coastal Alaska, including the Pribilof Islands and Bristol Bay; extending eastward into Canada to the southwest coasts of Banks and Victoria Islands and the mouth of Bathurst Inlet in Nunavut Province (formerly known as Northwest Territories).

The geographical boundary for Atlantic walrus is basically the Arctic and Atlantic coasts south to Massachusetts. More specifically the Atlantic walrus boundary in Canada extends westward to Mould Bay of Prince Patrick Island, to just east of Cape George Richards of Melville Island and to Taloyoak, Nunavut Province (formerly known as Spence Bay, Northwest Territories); and eastward to include trophies taken in Greenland.

The Roosevelt’s elk category was established in 1980. Roosevelt’s elk trophies have thicker, shorter antlers, and many of the largest trophies develop crown points, a very distinctive feature.

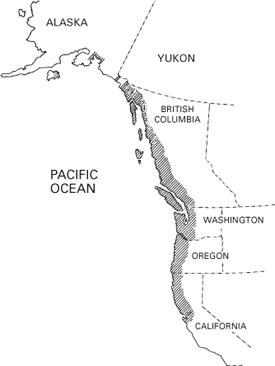

Roosevelt’s elk are acceptable from Del Norte, Humboldt, and Trinity Counties, California, as well as that portion of Siskiyou County west of I-5 in northern California; from west of I-5 in Oregon and Washington; from Afognak and Raspberry Islands of Alaska; and from Vancouver Island and all of the islands in the Strait of Georgia in British Columbia. On the British Columbia mainland, the Roosevelt’s elk boundary includes all of the coastal watersheds of Butte Inlet at the north to Frazer River, Harrison River/Harrison Lake and the Lollooet River and all it’s tributaries at the south.

The Alaskan animals are the result of a successful transplant from the Olympic Peninsula of Washington. To date, only one Alaskan trophy, exceeding the Awards book minimum of 270 points, has been accepted for listing in the Club’s records books. Washington State is the top Roosevelt’s elk producing state, followed by Oregon, California, and the province of British Columbia.

The tule elk category was established in 1998 by the Records Committee after several years of careful and detailed review. The geographical boundary (figure 2-B) for tule elk is as follows: That portion of California within a line beginning at the junction of the Pacific Ocean and the Ventura-Santa Barbara County line; north along the Ventura-Santa Barbara County line to the Kern County line; east along the Kern County line to I-5; north along I-5 to the Kern County line; east along the Kern County line to the San Bernardino County line; east along the San Bernardino County line to the California-Nevada state line; northwest along the California-Nevada state line to I-50; west along I-50 to I-5 in Sacramento County; north along I-5 to the Tehama County line; west along the Tehama County line to the Mendocino County line; north and then west along the Mendocino County line to US Highway 101; south along US Highway 101 to State Route 156 in Monterey County; southwest along State Route 156 to State Route 1 in Monterey County; south along State Route 1 to San Jose Creek in Monterey County; south along San Jose Creek to the crest of the Santa Lucia Range in Monterey County; southeast along the crest of the Santa Lucia Range to State Route 41 in San Luis Obispo County; southwest along State Route 41 to Morro Creek in San Luis Obispo County; southwest along Morro Creek to the Pacific Ocean; south along the Pacific Ocean to the point of beginning.

All other elk varieties, from the Rocky Mountains and eastward, are now referred to as either typical or non-typical American elk.

The problem of properly defining the boundary between the large antlered mule deer, which ranges widely over most of the western third of the United States and western Canada, and its smaller relatives, the Columbia and Sitka blacktails of the West Coast, has been difficult from the beginning of records keeping. The three varieties belong to the same species and thus are able to interbreed readily where their ranges meet. The intent of the Club in drawing suitable boundary lines is to exclude intergrades from each of the three categories. These boundaries have been redrawn as necessary, as more details have become known about the precise ranges of these animals. Current B&C sponsored DNA research may result in additional boundary changes.

The current boundary (figure 2-C) for mule and Columbia blacktail deer is as follows:

British Columbia — Starting at the Washington-British Columbia border, blacktail deer range runs west of the height of land between the Skagit and the Chilliwack Ranges, intersecting the Fraser River opposite the mouth of Ruby Creek, then west to and up Harrison Lake to and up Tipella Creek to the height of land in Garibaldi Park and northwesterly along this divide past Alta Lake, Mt. Dalgleish, and Mt. Waddington, thence north to Bella Coola. From Bella Coola, the boundary continues north to the head of Dean Channel, Gardner Canal, and Douglas Channel to the town of Anyox, then due west to the Alaska-British Columbia border, which is then followed south to open water. This boundary excludes the area west of the Klesilkwa River and the west side of the Lillooet River.

Washington — Beginning at the Washington-British Columbia border, the boundary line runs south along the west boundary of North Cascades National Park to the range line between R10E and R11E, Willamette Meridian, which is then followed directly south to its intersection with the township line between T18N and T17N, which is then followed westward until it connects with the north border of Mt. Rainier National Park, then along the north, west and south park boundaries until it intersects with the range line between R9E and R10E, Willamette Meridian, which is then followed directly south to the Columbia River near Cook.

Oregon — Beginning at Multnomah Falls on the Columbia River, the boundary runs south along the western boundary of the National Forest to Tiller in Douglas County, then south along Highway 227 to Highway 62 at Trail, then south following Highway 62 to Medford, from which the boundary follows the range line between R1W and R2W, Willamette Meridian, to the California border.

California — Beginning in Siskiyou County at the Oregon-California border, the boundary lies between townships R8W and R9W M.D.M., extending south to and along the Klamath River to Hamburg, then south along the road to Scott Bar, continuing south and then east on the unimproved road from Scott Bar to its intersection with the paved road to Mugginsville, then south through Mugginsville to State Highway 3, which is then followed to Douglas City in Trinity County, from which the line runs east on State Highway 299 to I-5. The line follows I-5 south to the area of Anderson, where the Sacramento River moves east of I-5, following the Sacramento River until it joins with the San Joaquin River, which is followed to the south border of Stanislaus County. The line then runs west along this border to the east border of Santa Clara County. The east and south borders of Santa Clara County are then followed to the south border of Santa Cruz County, which is then followed to the edge of Monterey Bay.

On the Queen Charlotte Islands of British Columbia and along the coast of Alaska ranges another subspecies of mule deer, the Sitka blacktail. Accordingly, after a compilation of scores of the largest Sitka blacktail deer trophies from southern Alaska (including those from Kodiak Island where they have been transplanted), a separate trophy category was established for Sitka blacktail deer in 1984 with a minimum All-time records book entry score of 108.

Sitka blacktails have been transplanted to the Queen Charlotte Islands and are abundant there. Thus, the acceptable area for this category includes southeastern Alaska and the Queen Charlotte Islands of British Columbia.

Whitetail deer range widely over North America, with recordable trophies known from almost all of this range. The largest specimens are more common from the northern states and southern Canada. Although there is some sentiment for subdividing the range of whitetails into more than two categories, with lower minimums for the southern states, there are no natural boundaries to use in such an effort. But, the tiny Coues’ whitetail of the southwest is a different story. It has been recognized in a separate trophy category since the start of the Club’s big game records keeping in 1932. The acceptable area for Coues’ whitetail deer entries is defined as central and southern Arizona and the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua. In New Mexico the Coues’ whitetail deer boundary is defined as: the Arizona border to the west, the New Mexico border to the south, the Rio Grande River to the east and I-40 to the north. Current B&C sponsored DNA research may result in additional boundary changes.

The boundaries for the three classes of moose have remained essentially unchanged since the beginning of the records keeping. But, hunting opportunities for moose have increased in recent years so that moose are now hunted in the Mackenzie Mountains of Northwest Territories, northern Utah, northeastern Washington, northern Minnesota, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont.

The Alaska-Yukon moose category includes moose from Alaska, Yukon Territory, and Northwest Territories.

The Canada moose category includes moose from all of the remaining provinces of Canada, plus Maine, Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Dakota and Vermont.

The Shiras’ moose category has the Canadian border as its northern boundary. Its range includes all of the Rocky Mountain region south of Canada and west to the Pacific Ocean, including the following states: Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

The various varieties of caribou, which vary widely in size and antler configuration, have required subdivision of the species into five different trophy categories: mountain, woodland, barren ground, Central Canada barren ground, and Quebec-Labrador. Prior to 1960, the classification of the different species and subspecies of the world was in disarray. At that time, Frank Banfield (a Canadian wildlife biologist) reviewed all of the available museum specimens of the world’s caribou and reduced the number of valid subspecies. Among his conclusions were that the new world caribou and the old world reindeer should all be classified as one species, but that northern barren ground caribou differ from the more southerly distributed woodland caribou, both in Eurasia and in North America.

The largest antlered caribou from North America are the Grant’s variety from Alaska and northern Yukon Territory. These caribou, called barren ground caribou for records-keeping purposes, have long, rounded main beams with very long top points. They also have the highest all-time records book minimum entry score of 400 points. (See below for description of boundary between barren ground caribou and mountain caribou in Yukon Territory.)

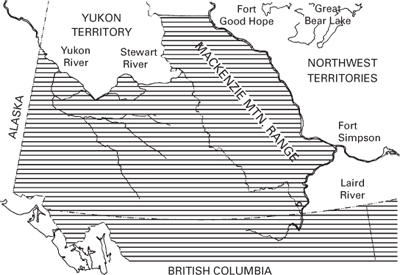

The so-called mountain caribou, now regarded as a variety of woodland caribou, is found in British Columbia, Alberta, southern Yukon Territory, and the Mackenzie Mountains of Northwest Territories. In Yukon Territory, the boundary (figure 2-D) begins at the intersection of the Yukon River with the boundary between Yukon Territory and the state of Alaska. The boundary runs southeasterly following the Yukon River upstream to Dawson; then easterly and southerly along the Klondike Highway to Stewart Crossing; then easterly following the road to Mayo; then northeasterly following the road to McQuesten Lake; then easterly following the south shore of McQuesten Lake and then upstream following the main drainage to the divide leading to Scougale Creek to its confluence with the Beaver River; then south following the Beaver River downstream to its confluence with the Rackla River; then southeasterly following the Rackla River downstream to its confluence with the Stewart River; then northeasterly following the Stewart River upstream to its confluence with the North Stewart River to the boundary between Yukon Territory and Northwest Territories. North of this line caribou are classified as barren ground caribou for records-keeping purposes, while those specimens taken south of this line are considered mountain caribou.

Central Canada barren ground caribou occur on Baffin Island and the mainland of Northwest Territories and Nunavut, as well as in northern Manitoba and northern Saskatchewan. Caribou from other Arctic islands north of the mainland of Northwest Territories/Nunavut are ineligible for entry in B&C’s records books. The geographic boundaries in the mainland of Northwest Territories are: the Mackenzie River to the west; the north edge of the continent to the north (excluding any islands except Baffin Island); Hudson’s Bay to the east; and the southern boundary of Northwest Territories to the south.

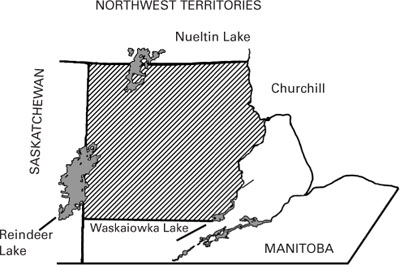

The boundary (figure 2-E) for Central Canada barren ground caribou in Manitoba begins at the point of intersection of the south limit of township 87 with the provincial boundary between the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. The boundary then follows this township line east to the point of confluence with Waskaiowka Lake. From there it proceeds in a northeasterly direction along the high-water mark of the north shore of the aforementioned lake following the sinuosities of the shoreline to the point of intersection with the water connection to Hale Lake. From this point, the high-water mark of the north shoreline is followed to the point of intersection with the Little Churchill River. Henceforth, it follows the high-water mark of the north or westerly shore of the Little Churchill River including expansions of the river into lakes to the point of confluence with the Churchill River. From there the boundary crosses the mouth of the Little Churchill River and follows the high-water mark on the south or easterly shore of the Churchill River to the community of Churchill located on Hudson Bay.

Caribou taken in Manitoba north of the above described boundary are classified as Central Canada barren ground caribou.

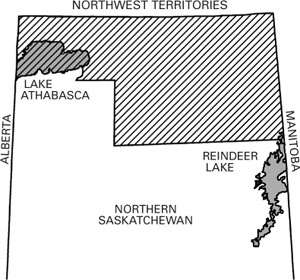

In Saskatchewan, Central Canada barren ground caribou occur within Wildlife Management Zone #76 (figure 2-F). The boundary begins at the intersection between the 59th parallel and the Alberta-Saskatchewan border (intersection of 59th parallel and 110th meridian), runs east a few kilometers along the 59th parallel to its juncture with the south shore of Lake Athabasca, then follows the south shore of Lake Athabasca north easterly to the mouth of the MacFarlane River, turns south along the MacFarlane River to its juncture with the 109th meridian, follows the 109th meridian south a few kms to its intersection with the 58th parallel, turns easterly along the 58th parallel to its intersection with the 107th meridian, turns south along the 107th meridian until its intersection with the 58th parallel, then turns east and follows the 58th parallel to the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border (intersection of 58th parallel and 102nd meridian). North of this line is the Central Canada barren-ground caribou zone (Wildlife Management Zone 76) where Central Canada barren ground caribou may be legally hunted in Saskatchewan.

The Quebec-Labrador caribou category was established in 1968. This large woodland caribou has very wide, long-beamed antlers with almost universally palmated bez formations. To have left these animals in competition with the woodland caribou of Newfoundland would have resulted in a complete swamping of the smaller-antlered woodland caribou from Newfoundland. Boundaries for Quebec-Labrador caribou are just as the name implies, Quebec and Labrador.

Woodland caribou are eligible for entry from Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and New Brunswick. Woodland caribou occur sparingly all the way across Canada to southern British Columbia. Although there may be some open seasons in these provinces, they are not taken in large numbers anywhere. It would seem inappropriate to place such animals in competition with those from Newfoundland where they have been regularly hunted for more than 100 years.

Bison exist as wild, free-ranging herds in their original setting in very few places. They are eligible for entry in B&C from states and provinces that recognize them as wild and free-ranging big game animals and for which a hunting license and big game tag are issued. Table 2-A on the following page lists the specific areas within those states and provinces from which bison are accepted.

BISON LOCATIONS

Locations from which B&C currently accepts bison entries.

A. ALASKA

1. Copper River

2. Delta Junction

3. Farewell

B. ARIZONA

1. House Rock Valley Herd – Coconino County

2. Raymond Wildlife Area – Coconino County

C. MONTANA

1. Areas adjacent to Yellowstone National Park – Park County

2. Portions of Crow Indian Reservation

D. SOUTH DAKOTA

1. Custer State Park

E. UTAH

1. Antelope Island – Davis County

2. Henry Mountains – Garfield, Wayne and San Juan Counties

3. Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation

F. WYOMING

1. Areas adjacent to Yellowstone National Park – Teton County

G. ALBERTA

1. Northern

H. BRITISH COLUMBIA

1. Pink Mountain

I. NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

1. Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary

J. YUKON TERRITORY

1. Aishihik Wood Bison Herd

Beginning with the 8th edition (1981) of the All-time records book, the two previously recognized categories of musk ox (Greenland and barren ground) were combined into a single category. Musk ox from Alaska, Canada, and Greenland are all eligible for entry into the single category recognized today.

The wild sheep of North America belong in only two species, the thin-horned sheep of northern British Columbia northward (Ovis dalli), and the bighorn sheep ranging from central B.C. southward to Baja, California (Ovis canadensis).

Dall’s (or white) sheep range over much of Alaska, most of Yukon Territory, the Mackenzie Mountains of Northwest Territories, and an isolated area of British Columbia. Stone’s sheep occur primarily in northern British Columbia. Where the ranges of these two subspecies meet, the intergrade animals may range through a variety of dark gray shades to almost white. This intergrade was, at one time, regarded as a separate subspecies (Fannin’s sheep), but this form cannot really be defined and the idea of a separate category for such animals was rejected many years ago. After consultation with guides, knowledgeable biologists and hunters, the decision was made that any thin-horned sheep that shows any black hairs on the body is classified as a Stone’s sheep, unless only the tail is black. In the case of a black tail only, the trophy would be considered a Dall’s sheep. The area from which Fannin-type trophies are known is primarily the Pelly Mountains of the southern Yukon. But, they might be recorded from extreme northern British Columbia, and perhaps other localities in the southern Yukon.

The bighorn sheep are separable into Rocky Mountain bighorn and desert bighorn. Desert sheep are found in Nevada and southward into and including Mexico, and eastward into Arizona and southern New Mexico into extreme western Texas. Rocky Mountain bighorns are found in the main Rocky Mountains northward into western Alberta and southeastern British Columbia. Numerous bighorn sheep transplants have been made in the Western states, some of which have been spectacularly successful in restoring sheep to ancestral ranges. In some cases, extremely high scoring trophies have come from these transplanted animals or their progeny.

These transplants have resulted in problems for trophy recordation in the case of the restoration of the so-called California bighorn, which has flourished in natural populations only from central and southcentral British Columbia. This subspecies originally ranged from extreme northeastern California through eastern Oregon, into eastern and central Washington, extreme southwestern Idaho, and northward into central British Columbia. Successful transplants from British Columbia have now been made into North Dakota (where the now extinct Audubon’s sheep originally occurred), as well as many other areas within the original range of the subspecies. Currently, a few California bighorns are recorded in the listing for Rocky Mountain bighorns, and these specimens are largely from native animals taken in British Columbia. Since it appears that California bighorns do not have as large horns as those from the Rocky Mountains, there have naturally been requests to establish a new trophy category for such animals. For now, they are considered as Rocky Mountain bighorns for the records keeping.

Several years ago the Club started receiving Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep from Greenlee County, Arizona, where specimens of this category of sheep were transplanted a number of years ago. More recently, the Club received a desert sheep from Mesa County, Colorado, where specimens of this category were transplanted some years ago. ■