Nelson and His Times

The latter portion of 1805 was one of suspense to the people of Britain. The great war with Napoleon had lasted with but brief intermission since 1793. On land the French arms had been victorious. Europe lay under the domination of the newly-crowned French Emperor. The war at sea, at first largely confined to a struggle to capture or retain colonies, had gradually assumed a more threatening aspect so far as invasion of England was concerned. Events had brought home to Napoleon that his real enemy was Great Britain. He had imposed his rule and peace, at will, on all the European nations except those of these islands, and it was they who, with money and their fleet, energetically continued to oppose his autocratic assumption of ruling the destinies of Europe.

The two weapons at his disposal to reduce this country to obedience were actual invasion and commercial starvation. The former was the one which appeared to be the more feasible, and it was this threat that lay most heavily over our nation. Our one hope for immunity from the consummation of Napoleon’s designs lay in the Navy. Our Navy was but slightly numerically stronger than that of the French Navy combined with those of the varying Allies of France. It was, therefore, fortunate for us that our Navy was at that time vastly superior to the French and every other European nation in sea experience. For a moment let us trace the causes that led to this superiority.

The great war which began in 1793, and which convulsed Europe for over twenty years, was the direct outcome of the French Revolution. The Revolution had shaken the structure of French social organization with violence, destroying both bad and good alike, and disorganizing all the public services; none of which suffered more than the French Navy.

In 1790 the French Navy was a service to be proud of: in 1794 it was a disorganized rabble. In Lord Howe’s victory at the battle of the 1st of June, 1794, the three admirals and twenty-six captains of the French Fleet had three years before held the following positions: The Commander-in-Chief had been a lieutenant; one of the two other admirals had been a lieutenant and the other a sub-lieutenant. Of the captains, three had been lieutenants, eleven sub-lieutenants, nine had been merchant ship officers, one a seaman in the navy, one a boatswain, and one unknown.1 The French Navy, therefore, was at that time as regards its officers in a thoroughly disorganized condition. As regards the men it was little better.

Moreover, energetic action on the part of our naval authorities had instituted blockades off all the French naval ports. This was with a view to preventing the various units of their fleet leaving and combining without being brought to action; but it had a secondary and far-reaching effect, in that it imposed idleness on the crews of the French vessels, and denied them that constant practice and experience in handling and working sailing ships, as well as in gunnery, which was absolutely necessary for reasonable efficiency in action.

With us the blockade had the exact contrary effect: our ships were constantly at sea, sometimes for two years or more, always sailing, always practised in manoeuvring and working the ships; reefing, trimming, shortening and making sail, until sea-lore was a commonplace.

When the French fleet put to sea it was more or less a rabble. Unused to the motion, the men suffered from sea-sickness; but, beyond all, that feeling of accustomedness to sea work, and the confidence begotten by it, were absent. In their place a feeling of diffidence and uncertainty supervened, increased almost to despair by the early evidences of the inexperience of officers and crews as their vessels passed the heads of their ports and met the ocean swell and the shifting winds. It is useless to make a cavalry charge with raw recruits, or to fight a naval action in sailing ships with unpractised crews.

Confidence is an asset of incalculable value to a fighting force, and this was even more so in the old sailing days, when the whole crew were implicated in the sailing and handling of the ships, and often were called on to take a part in hand-to-hand fighting. In present years the handling of the ships is largely independent of the crew, who merely tend the oil fuel and keep an eye on the lubrication of the turbines or load the guns. The movements of the ship are controlled by one or at the most two officers, and the fire of the guns is, again, in the hands of half a dozen officers; the men merely load and lay the guns mechanically in obedience to the movements of certain pointers.

Such then was the condition of the French Navy in Nelson’s time. It is well to keep these facts in mind when we look back on the old-time victories. We may well be filled with admiration of the deeds of our old sea heroes, but at the same time we must give due weight to the conditions prevailing in those times which aided our seamen in gaining the sweeping victories that history has recorded, and which we are apt to ascribe solely to a superiority of courage or genius in our race.

It is not infrequently the practice of modern writers to compare some existing popular naval officer with Nelson, and to judge the actions of others by what they call the “Nelsonic standard”. Nelson was, and always will be, a unique personality; but much of the picturesqueness of his complex character was due to the conditions of the times in which he lived. Had Nelson lived in the twentieth century he would appear to those writers to be totally different to the Nelson of whom they write, and who lived in the early nineteenth century.

The day of complete freedom of action at sea has gone, wireless telegraphy and telegrams have destroyed the conditions which developed much of the independence of his character. Hand-to-hand combats have passed; little chance remains of exhibiting exceptional gallantry in an action. The fiery longing to exhibit personal prowess and the love of close combat can now be satisfied only on the rarest occasions, and then only in vessels of small value like destroyers. Those impulses would develop into a positive danger to the nation if indulged in by those in command of our more valuable vessels.

The kernel of Nelson’s character would still remain if he were alive today; his devotion to duty and prompt decision, the result of earnest thought, would persist; but the conditions that govern the use of these qualities in a modern navy are so different that they would appear to be totally different attributes. The one predominant quality that Nelson exhibited, and which stamps him as a great sea commander, was a swift and unerring judgment and quick determination in a crisis in battle. He had many other high qualities as an officer: restless activity, a high sense of duty, a natural love of fighting, which, of course, endowed him with a personal gallantry conspicuous even in his own day of gallant fighters.

Many others have possessed these qualities to as great an extent as Nelson, although perhaps they have not given expression in words, or writing, so fully to their feelings regarding duty and love of fighting as Nelson through his peculiar singleness of character was wont to do. It is this constant repetition in correspondence and conversation, of “doing his duty” of “getting at the enemy” that reveal the constant thought and rumination over the problems that confronted him, and undoubtedly it was the constant thought over possibilities, and visualizing probable and possible conditions, that sharpened his natural rapidity of thought and caused him to recognize and to act instantly in a critical phase of an action.

Independence of action bred of profound belief in himself and his judgment (a most necessary quality in every officer) led him immediately to take the action he considered to be right. It is utterly improbable that Nelson, like many other officers, considered personal gallantry as anything but a matter of course. Thousands of officers would not hesitate to place themselves in positions of risk and danger when they considered such action necessary. Nelson never threw himself into a position of danger merely to exhibit his gallantry. He was to himself merely one of the ship’s company; to share with them the hazards that duty demanded – this is the correct spirit of an officer.

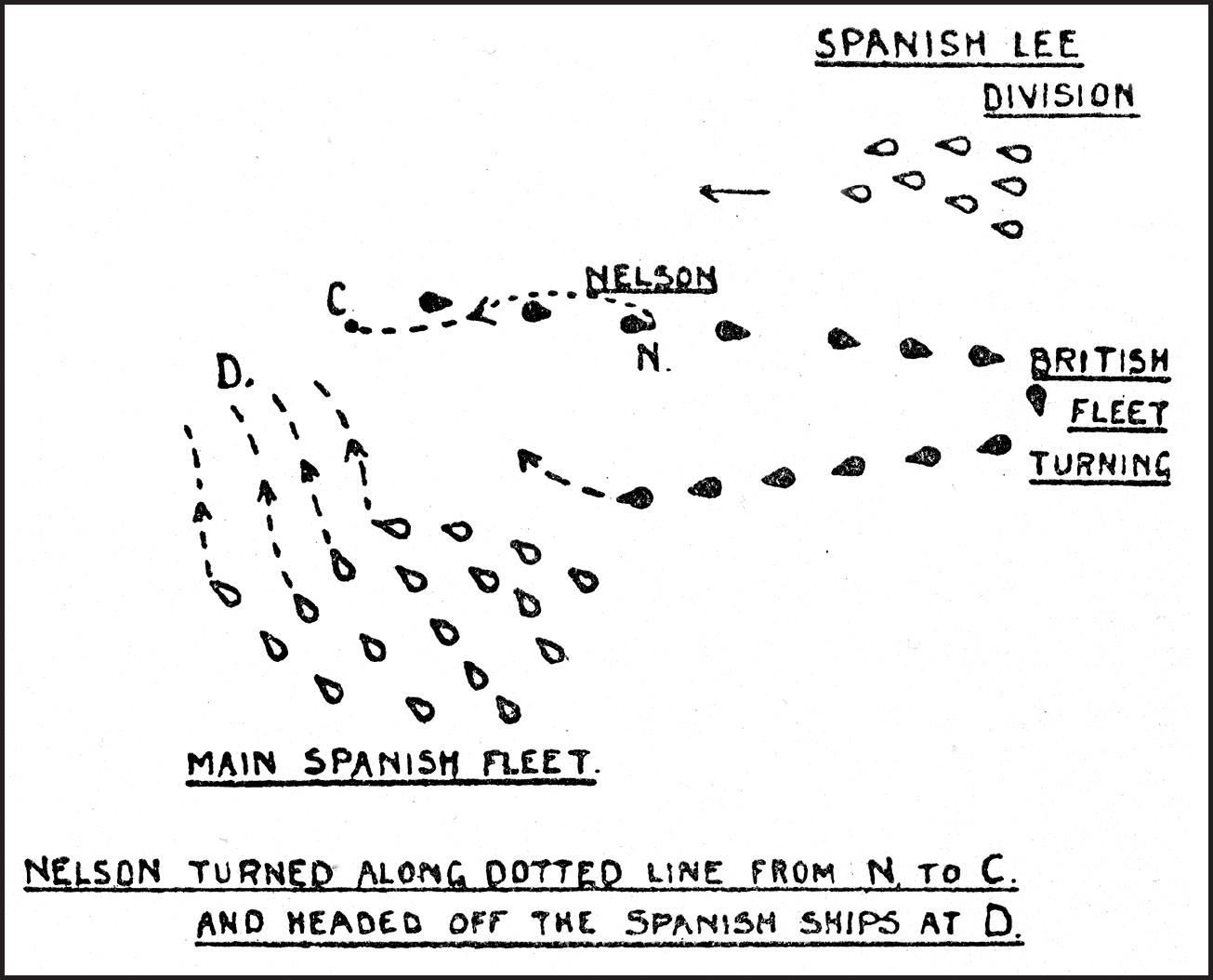

DIAGRAM 1

In every action at sea in which Nelson was engaged he showed unerring judgment at some crisis. In the battle of Cape St. Vincent, his first fleet action, he commanded the Captain, which according to seniority was stationed as the thirteenth ship in the line. Sir John Jervis, afterwards Lord St. Vincent, led the British line of battle down between two portions of the Spanish Fleet which had become separated from each other – one group of ships lay to windward of him, and the other group to leeward. Now, in sailing days, it took a long time for ships to leeward to beat up and join those to windward, since the wind was blowing dead against them, and they had to make long zigzags to reach the desired point. In fact, for a line-of-battle ship to reach a point three miles to windward, it had to sail approximately sixteen miles through the water. On the other hand, ships to windward had only to steer a straight course with the wind behind them to join their consorts to leeward of them.

When the Spaniards detected Jervis’s design, the captains of the ships to windward altered course to join their detached unit to leeward, in order to reunite their fleet in one compact body and so defeat the British tactics. Nelson saw their intention and at once appreciated the full measure of their manoeuvre; without hesitation, he left the line of battle and threw his ship in the road of the ships bearing down, bringing his broadside to bear and raking the leading ship. His resolute action miraculously stopped the remainder of the Spanish ships following the example of their leaders. The ship next astern of Nelson followed suit and supported him; thus the success of Jervis’s manoeuvre was assured.

Now the details of this operation give much food for thought. Nelson exhibited a rapid appreciation of the crisis and prompt action in carrying out his decision. The captain next astern was equally gallant, but Nelson was solely responsible for the quickness of brain and independence of action that led to the brilliant manoeuvre.

In discussing this action we must give due weight to the traditions of the times. To break out of the line might well have been considered by some admirals a deadly sin, and had the action been lost Nelson might have been made a scapegoat. It was his decision to do, against precedent, what he considered was right that showed a moral courage far more rare than mere gallantry. A man who had merely lived in the present, without daily analysing the past or visualizing the future, would have let the opportunity slip. Moral courage, prepared thought and accurate judgment were the attributes Nelson showed at the battle of St. Vincent.

Let us now pass over two years and turn to Nelson’s next sea fight, that of Aboukir Bay, probably the most dramatic of all sea battles, fought at night, with all the weirdness of night fighting, where the grappling hand-to-hand struggle in the darkness was illumined by the flash of guns and explosions. The young Rear-Admiral, selected specially to command the fleet detached to watch the French in Toulon, had, through no fault of his own, allowed their vessels to escape from that port in a gale. He had fruitlessly chased to the east to find them.

Mortified in spirit, he was perfectly conscious that it was luck merely that had favoured their escape; but he also knew the ignorance of the British public and their avidity for blaming all but successful officers; painfully he felt that his chances of serving his country, as he knew that with the right opportunity he could serve her, were slipping by. When almost in despair the French Fleet was sighted at anchor in Aboukir Bay. He decided to attack at once, although darkness would close down before the battle could be decided. Let it not be forgotten that the deterrents to modern night fighting were all absent – no torpedoes or torpedo-craft existed; the enemy was at anchor, and there was no chance, therefore, of mistaking friend for foe.

Captain Foley led the line, and when approaching the French Fleet had one of those flashes of thought which experience only can originate. The ships at anchor conjured up to his mind their swinging round their anchors at the full scope of their cables, and therefore he recognized intuitively that there was enough water inshore of them to float his ship. The unpreparedness of guns on the disengaged side, because of the lumber which was often temporarily placed around them in the sudden emergency of a surprise fight, flashed into his mind. So without hesitation he led the line inshore of the enemy and engaged them on their unprepared side. The next six ships followed him and passed inside, till Nelson, in the Vanguard, reached the head of the French line. Without hesitation he led the remainder outside and placed them to seaward of the enemy, thereby having, roughly speaking, one English ship on each side of each ship in the northern half of the French Fleet; while the southern half of that fleet was left with their broadsides pointing harmlessly to the east and west altogether out of the action, and totally unable to assist the head of the line, which was being sorely engaged, and rapidly crushed by the overwhelming force of a one to two fight.

DIAGRAM 2

Disputes have centred round the point as to whether Nelson or Foley doubled the line. Some, who have been unable to give credit to anyone but Nelson, have suggested that the situation had been previously discussed, and that Nelson had indicated the action to be followed. This is most unlikely, since there is no reason to suppose that Nelson ever anticipated fighting the French Fleet at anchor – an utterly improbable situation. Let us give Foley the credit of leading the ships round to the disengaged side – a flash of genius bred of experience – but let us take the common-sense view that Foley never intended by his action to “double the line”, that is, to place one ship each side of each of the French vessels. That was due to Nelson’s genius. As a sea officer, Nelson must have appreciated that Foley had given him the enormous advantage, the great initial advantage, of engaging the unprepared side of the enemy’s vessels; but, as a master of tactics, he saw that every minute given to the enemy allowed the French vessels to prepare the guns on their shoreward side for action; and that the doubling of two of our ships to one of the enemy was fifty times more valuable than the temporary advantage that Foley’s action had given to the leading vessels.

Let us note most carefully that Nelson’s tactics were not what modern critics would call “Nelsonic”; personal bravery was subordinated to the end to be achieved. He did not disdain to place his ship, coming fresh and without a shot having been fired at her, alongside a half-beaten ship to complete her destruction. He did not dash in a fiery manner to engage a new and unattacked enemy; he did merely what his unerring judgment told him was the right course, one dictated by the brain and not the lust of the fighter.

Years elapsed and Nelson was in the North Sea, second-in-command to Sir Hyde Parker. He had reconnoitred the offing of Copenhagen and decided in his mind that he could attack and reduce the batteries.

No previous attack of this nature had been tried on a grand scale; there was no previous experience to guide him and to enable him to appreciate the advantages that well-prepared shore positions possess against the attack of ships. He persuaded the Commander-in-Chief to allow him to make the attack with a portion of the fleet. Nothing was left to chance that could be done previous to the engagement. The passage was surveyed and all made ready.

The fight began and its progress showed that the outcome was, to say the least, doubtful. Nelson’s judgment suppressed his fighting ardour: he arranged an armistice and saved his squadron. Brain and clear thought in the middle of a fierce fight saved the ships. Nelson showed himself in a new light; no similar deed had ever been done by a naval commander, but his unfaltering judgment in action suppressed his love of fighting. The course he followed can hardly again be called “Nelsonic” in the popular sense, but in no action has Nelson, as an admiral in command, shown greater brain power or judgment than at the Battle of Copenhagen.

One word in passing. The famous episode of Nelson disregarding Hyde Parker’s signal to discontinue the action has its lessons. The Commander-in-Chief had given his consent to the undertaking – the attack was launched, and he had no right to cancel his permission unless some new information had reached him to cause him to reconsider the position; or, unless conditions had arisen whereby his portion of the fleet was compromised by the absence of Nelson’s ships.

Neither of these had occurred, and therefore he had no right to get “cold feet” and cancel the operation. Or, perhaps, since “cold feet” are constitutional, and it is out of the power of the individual to avoid them, he might bitterly regret having given his sanction – but it was his duty to maintain sufficient self-control not to hamper a subordinate to whom he had assigned a definite detached operation. Nelson’s conduct in disregarding the signal was dictated by common sense. He knew his Commander-in-Chief, and we may let it rest at that: or, to put the matter in a nutshell, if St. Vincent had recalled him, Nelson would have put his telescope to his good eye, for he would have known there was a reason for the signal; but his blind eye came into use with Hyde Parker because Nelson knew Hyde Parker.

The Battle of Trafalgar saw Nelson at his prime as a naval Commander-in-Chief. The years between the Battle of Copenhagen and 1805 had been full of experience and incident. He had had unique opportunities for making an accurate estimate of the French Navy and also the Spanish Navy as fighting forces, and on those estimates he was able to base the tactics of his fleet. The quiet of Merton had given him the opportunity of reviewing the past and of thoroughly analysing the busy years of the war. Whilst at Merton he evolved the future tactics of any fleet he might command. It is not difficult to trace the lasting impression made on him by the Battle of the Nile in his development of the “Nelson touch”, as he loved to call his tactical scheme for a fleet action.

Briefly the scheme was to divide his fleet into two squadrons; to throw one half on to a lesser number of the enemy while he, with the other, took up a position to threaten the unengaged portion of the enemy’s ships should they attempt to go to the succour of their engaged vessels.

Here, again, we have the true Nelson spirit shown. Not the “Nelsonic spirit”. He did not propose to engage; he did not propose to rush helter-skelter into the action; but to remain clear of the fighting, because by so doing he was free to bring his mature judgment to bear, and to seize the critical moment when the disengaged section of the enemy might attempt to turn to assist their heavily beset comrades. His time for fighting would come later when the first stage of the battle was decided; then he would hurl himself on the disengaged half of a fleet whose other half had been beaten.

Let us then, above all, correct any mistaken ideas we may have imbibed from sensational writings about Nelson as a sea officer. He was not in any way merely “a bull at the gate” fighter; there were, at that time, dozens of such men in the British Navy who never rose above mere passing distinction. He was essentially a thinker and an organizer and a great leader of men.

Loyalty and single-mindedness were such marked features in his character that never would he have permitted anyone to let their adulation overstep the limits of propriety and seek to magnify Nelson at the expense of any of his Commanders-in-Chief.

His action at St. Vincent was that of a man who had a profound grasp of the essentials of fleet tactics, and the eye to size up the situation and to seize the opportunity. His doubling his ships on those of the enemy at the Nile and not disdaining to engage a ship already being engaged instead of choosing one that was not being fought, again stamps him as a tactician who could keep his thirst for glory under control.

At Copenhagen his adroitness in getting his fleet out of what might have been a disastrous dilemma again shows an appreciation of when to fight and when to retire. He mastered every detail of supply, health and gunnery of his fleet; the men consequently were healthy and his ships could be relied on to shoot with considerable accuracy.

Lastly, his tactic known as the “Nelson touch” was designed to keep half of the fleet under his immediate command, in reserve ready to help the other half and ward off any concentration on the part of the enemy. If, therefore, Nelson the great sea officer had been in command of the Grand Fleet at Jutland, we may be perfectly certain of one thing; that he would have done nothing foolish, he would never have allowed any gallery display to lead him to risk the Grand Fleet, he would never have applied Trafalgar tactics to twentieth-century fighting. It is grossly libellous to imagine he would have done so. We may be quite sure that the sound tactic was the one that would have been followed by him instantly as the occasion for it might arise.