Colonial houses on Providence’s Benefit Street are like casseroles at a church supper: too much of a good thing. Yet, the yellow colonial house across the street from my office attracts attention. The door, at street level, opens directly into a stone-lined cellar. Since the house is set gable end to the street and built into a steeply rising hill, the main entrance is approached by climbing a flight of granite steps, then entering the yard through a gate. On the gatepost, four signs, in neatly lettered French, seem to warn of the wirehaired terriers, whose yapping muzzles bob above the low picket fence as if attached to yo-yo strings.

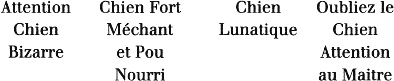

Fans of H. P. Lovecraft (1890—1937), and they are legion in Rhode Island, know the house at 135 Benefit Street as the “shunned house,” the title of one of his short stories. I don’t believe the signs are there to warn unwary strangers about the hyperactive dogs; rather, I think the owners of the house are sharing an inside joke with Lovecraft devotees who enjoy tracking down the places that he insinuates into his tales. The hidden meaning of their signs—directing visitors to beware of a bizarre, undernourished, mad dog, then instructing them to forget the dog and heed the master—is plain to those who have read “The Shunned House” (1937).

Lovecraft fans come in several varieties. I’m the casual sort who appreciates his embedding of history, local landmarks, and genealogy into outrageous fantasies. Lovecraft’s subtle transmutations of factual material glide by unchallenged, unless one seeks esoteric conversations with like-minded fans. Ordinarily, I’m not up for the task. Having read “The Shunned House,” though, I knew that Lovecraft alluded to the Mercy Brown event, stopping short of naming names. I didn’t think much about it until I began to follow a trail of entries in Ernest Baughman’s Type and Motif-Index of the Folktales of England and America. Under the heading “Vampire sucks blood of victims (usually close relatives) by unknown means,” I found references to vampire stories collected in Rhode Island, Vermont, and New York. I put the last two on hold to follow the Rhode Island trail, which revealed some links that the word “fascinating” only begins to portray. Vampires and werewolves and … Tillinghasts? Oh, my!

I picked up the trail at Baughman’s reference to Charles M. Skinner’s Myths and Legends of Our Own Land (1896). Skinner tells readers that his entries were “gathered from sources the most diverse: records, histories, newspapers, magazines, oral narrative—in every case reconstructed.” Alas, Skinner “reconstructed” the tales (which I take to mean that he took the liberty of rewriting them in his own words), and he did not provide his sources. Still, Skinner’s two-volume collection is, in itself, a valuable source for legends. In his tale “The Green Picture” (the one Baughman cited as a vampire story), the Mercy Brown incident from Exeter seems to function as a sort of explanatory device, saying, in effect, “there are people in this region who actually believe in vampires.”

In a cellar in Green Street, Schenectady, there appeared, some years ago, the silhouette of a human form, painted on the floor in mould. It was swept and scrubbed away, but presently it was there again, and month by month, after each removal, it returned: a mass of fluffy mould, always in the shape of a recumbent man. When it was found that the house stood on the site of the old Dutch burial ground, the gossips fitted this and that together and concluded that the mould was planted by a spirit whose mortal part was put to rest a century and more ago, on the spot covered by the house, and that the spirit took this way of apprising people that they were trespassing on its grave. Others held that foul play had been done, and that a corpse, hastily and shallowly buried, was yielding itself back to the damp cellar in vegetable form, before its resolution into simpler elements. But a darker meaning was that it was the outline of a vampire that vainly strove to leave its grave, and could not because a virtuous spell had been worked about the place.

A vampire is a dead man who walks about seeking for those whose blood he can suck, for only by supplying new life to its cold limbs can he keep the privilege of moving about the earth. He fights his way from his coffin, and those who meet his gray and stiffened shape, with fishy eyes and blackened mouth, lurking by open windows, biding his time to steal in and drink up a human life, fly from him in terror and disgust. In northern Rhode Island those who die of consumption are believed to be victims of vampires who work by charm, draining the blood by slow draughts as they lie in their graves. To lay this monster he must be taken up and burned; at least, his heart must be; and he must be disinterred in the daytime when he is asleep and unaware. If he died with blood in his heart he has this power of nightly resurrection. As late as 1892 the ceremony of heart-burning was performed at Exeter, Rhode Island, to save the family of a dead woman that was threatened with the same disease that removed her, namely, consumption. But the Schenectady vampire has yielded up all his substance, and the green picture is no more.

The sinister mould on the basement floor, interpreted as a vampire, coupled with the mention of the Exeter case of 1892, sent me back for a closer reading of “The Shunned House,” which also includes those elements. Writing in the first person, Lovecraft weaves fact and fiction into a seamless, gripping narrative whose focal point is an abandoned house built into a hillside on Benefit Street in Providence, odd in that its gable end faces the street and its small door opens directly into the cellar. Community legend had it that no one would live in the house because “people died there in alarmingly great numbers.” As a youngster, Lovecraft avoided the house, fearing its bad odors and especially the weirdly shaped, phosphorescent fungi that grew on the dirt floor of the cellar that the front door opened into. Aided by the tales of his uncle, Dr. Elihu Whipple, a medical doctor and a lover of local history and legend (who often conversed “with such controversial guardians of tradition as Sidney S. Rider and Thomas W. Bicknell”), Lovecraft pieced together the morbid history of the shunned house, built, according to his story, in 1763 by William Harris for his wife, Rhoby Dexter, and their four children.

Things were bad from the beginning. The first child born in the house to Harris and his wife was stillborn. (“Nor was any child to be born alive in that house for a century and a half,” according to Lovecraft’s text.) Soon, the older children began to die, too. Although the doctors made a diagnosis of “infantile fever,” people said it was a “wasting-away” condition. Then the servants, and then Harris himself, succumbed, and the widowed Rhoby “fell victim to a mild form of insanity, and was thereafter confined to the upper part of the house.” Her older sister, Mercy Dexter, moved in to manage the household. By this time, those servants who had not died, fled. Seven deaths and a case of insanity, all in the space of five years, made securing new servants next to impossible. Mercy at last found Ann White, “a morose woman” from Exeter, who, as Lovecraft wrote,

first gave definite shape to the sinister idle talk. Mercy should have known better than to hire anyone from the Nooseneck Hill country, for that remote bit of backwoods was then, as now, a seat of the most uncomfortable superstitions. As lately as 1892 an Exeter community exhumed a dead body and ceremoniously burnt its heart in order to prevent certain alleged visitations injurious to the public health and peace, and one may imagine the point of view of the same section in 1768.

Ann White was soon discharged, but life in the house continued its downward slide.

The violent fits of Rhoby Harris increased in fury. “Certainly it sounds absurd to hear that a woman educated only in the rudiments of French often shouted for hours in a coarse and idiomatic form of that language, or that the same person, alone and guarded, complained wildly of a staring thing which bit and chewed at her.” She died the next year. As the tragic years rolled by, it became clear to people in the community that the evil was not in the family, but in the house and, specifically, the cellar. “There had been servants—Ann White especially—who would not use the cellar kitchen, and at least three well-defined legends bore upon the queer quasi-human or diabolic outlines assumed by tree-roots and patches of mould in that region.”

Lovecraft elaborated:

Ann White, with her Exeter superstition, had promulgated the most extravagant and at the same time most consistent tale; alleging that there must lie buried beneath the house one of those vampires—the dead who retain their bodily form and live on the blood or breath of the living—whose hideous legions send their preying shapes or spirits abroad at night. To destroy a vampire, one must, the grandmothers say, exhume it and burn its heart, or at least drive a stake through that organ; and Ann’s dogged insistence on a search under the cellar had been prominent in bringing about her discharge.

Even so, Ann’s tale made sense to many because of the way it “dove-tailed with certain other things”: the ravings of Rhoby Harris, who muttered of “the sharp teeth of a glassy-eyed, half-visible presence;” the servant who had preceded Ann White complaining that something “sucked his breath” at night; the death certificates of fever victims of 1804 showing that “the four deceased persons” were “all unaccountably lacking in blood;” and the land that the house was built upon once being used as a cemetery (although the graves all had been transferred to the North Burial Ground prior to the building of the Harris house).

After he interviewed surviving family members concerning the house, Lovecraft turned to the historical record. He found the French connection in one Etienne Roulet, who had leased the land in 1697. The Roulets had used a plot behind their small cottage as a family graveyard—and Lovecraft found no record of a transfer of graves. The Roulets, from the small village of Caude in France, were part of the unfortunate group of Huguenots who settled in East Greenwich in the late seventeenth century, but eventually abandoned their property in the face of unrelenting intimidation by neighbors who laid claim to land the Huguenots believed they had purchased. Before fleeing to Providence, Etienne Roulet (“less apt at agriculture than at reading queer books and drawing queer diagrams”) had been given a clerical post “in the warehouse at Pardon Tillinghast’s wharf, far south in Town Street” in East Greenwich. Speculation and gossip concerning such activities as witchcraft followed the Roulets. Lovecraft, in his “wider reading,” came upon an “ominous item in the annals of morbid horror” that recounted the trial of a Jacques Roulet, condemned to be burned at the stake in Caude, France, in 1598. “He had been found covered with blood and shreds of flesh in a wood, shortly after the killing and rending of a boy by a pair of wolves. One wolf was seen to lope away unhurt.” For some unexplained reason, the wolfman was spared the death penalty by the parliament in Paris and locked away in a madhouse.

In light of this new evidence, the “anthropomorphic patch of mould” in the cellar acquired an increased terror, and Lovecraft noticed that above it rose “a subtle, sickish, almost luminous vapour which as it hung trembling in the dampness seemed to develop vague and shocking suggestions of form, gradually trailing off into nebulous decay and passing up into the blackness of the great chimney with a foetor in its wake.” Lovecraft and his uncle, Dr. Whipple (filling a role similar to that of Dr. Van Helsing in Dracula) decided to spend the night in the cellar, augmented with scientific apparatus to analyze and, if necessary, destroy the evil entity, which they surmised was “traceable to one or another of the ill-savoured French settlers of two centuries before, and still operative through rare and unknown laws of atomic and electronic motion.” One of their weapons, a flamethrower, was to be used “in case it proved partly material and susceptible of mechanical destruction—for like the superstitious Exeter rustics, we were prepared to burn the thing’s heart out if heart existed to burn.” Since the outcome of Lovecraft’s tale has no direct bearing on the issues at hand, I won’t spoil a good story by revealing its conclusion without purpose.

I could speculate that Lovecraft knew of Skinner’s “Green Picture” or, perhaps, the unascribed source used by Skinner. The parallels suggest more than simple coincidence. The core of both tales is an odious mould on a cellar floor (Skinner’s “silhouette of a human form, painted on the floor in mould” and Lovecraft’s “anthropomorphic patch of mould”), whose description matches up, feature for feature. Both tales refer to three explanatory legends that account for the mould, including that the ground beneath was the site of an old cemetery (Dutch vs. French) and that it is the grave of a vampire. Of the human-shaped stain on the basement floor, Lovecraft wrote, “Later I heard that a similar notion entered into some of the wild ancient tales of the common folk—a notion likewise alluding to ghoulish, wolfish shapes taken by smoke from the great chimney, and queer contours assumed by certain of the sinuous tree-roots that thrust their way into the cellar through the loose foundation-stones.” Then, of course, there are the allusions to the Exeter case of 1892, attached to the end of “The Green Door” but, consistent with Lovecraft’s narrative style, woven into “The Shunned House” in several strands, with varying degrees of subtlety. Lovecraft may have had a playful smile on his face when he introduced Mercy Dexter (though not from Exeter) and Ann White (not Brown, the Exeter maid/vampire expert).

The house that Lovecraft calls the Stephen Harris House was built about 1764 for John Mawney, a physician. One of the first houses built on Benefit Street, it was in the Mawney family for many years, but by the time Lovecraft penned his short story, it had been abandoned and was in sad disrepair—favorable elements for a haunted house.

We are familiar with the Sidney S. Rider that Lovecraft’s Uncle Elihu Whipple enjoys conversing with. He’s the historian who first printed the story of Snuffy Stuke in 1888, omitting the family name of Tillinghast. And what a coincidence that Lovecraft’s Frenchman-cum-werewolf, Etienne Roulet, happened to find employment with Pardon “Molasses” Tillinghast, Snuffy’s great-grandfather! Thomas W. Bicknell, the other “controversial guardian of tradition” in Whipple’s circle, actually published a five-volume history of the state in 1920 that included a chapter on the French Huguenots in Rhode Island. Etienne Roulet is nowhere to be found in this chapter, nor is he listed in the state’s cemetery database. But Jacques Roulet does indeed appear in the historical record, perhaps most accessibly to Lovecraft and other English readers, in Montague Summer’s The Werewolf. By the time this book appeared in 1934, Summers had already published two books on witchcraft and two on vampires, the second of which contained a citation of the William Rose case in Rhode Island (discussed in Chapter 4).

In his chapter on the werewolf in France, Summers included several accounts of cases that had come before Judge Pierre de Lancre (1553-1631). De Lancre had written extensively about his tenure as a trial judge for cases involving those accused of witchcraft. He had interviewed (perhaps taking depositions under duress?) both the witnesses and the accused. Believing that his predecessors had been too soft on witches and their ilk, De Lancre undertook to set things right. He boasted of having burned 600 of the heretics. Following is Summers’ synopsis of one of De Lancre’s published accounts of a werewolf trial over which he presided in 1598:

In the remote and wild spot near Caude, Symphorien Damon, an archer of the Provost’s company, and some rustics came across the nude body of a boy aged about fifteen, shockingly mutilated and torn. The limbs, drenched in blood, were yet warm and palpitating, and as the companions approached two wolves were seen to bound away into the boscage. Being armed and a goodly number to boot, the men gave chase, and to their amaze [sic] came upon a fearful figure, a tall gaunt creature of human aspect with long matted hair and beard, half-clothed in filthy rags, his hands dyed in fresh blood, his long nails clotted with garbage of red human flesh. So loathly was he and verminous they scarce could seize and bind him, but when haled before the magistrate he proved to be an abram-cove [a cant word among thieves, signifying a naked or poor man; also a strong, “lusty rogue, with hardly any cloaths on his back: a tatterdemallion”] named Jacques Roulet, who with his brother Jean and a cousin Julien vagabonded from village to village in a state of abject poverty. On 8th August, 1598, he confessed to Maître Pierre Hérault, the lieutenant général et criminel, that his parents, who were of the hamlet of Gressiére, had devoted him to the Devil, and that by the use of an unguent they had given him he could assume the form of a wolf with bestial appetite. The two wolves who were seen to flee into the forest, leaving the body of the slain boy whose name was Cornier, he declared were his fellow padders, Jean and Julien. He confessed to having attacked and devoured with his teeth and nails many children in various parts of the country whither he had roamed. As to his guilt there could be no question, since he gave precise details, the exact time and place, where a few days before, near Bournaut, had been found the mutilated body of a child, whom he swore he had throttled and then eaten in part as a wolf. He also confessed to attendance at the sabbat. This varlet was justly condemned to death, but for some inexplicable reason the Parliament of Paris decided that he should be rather confined in the hospital of Saint Germain-des-Prés, where at any rate he would be instructed in the faith and fear of God. It would seem that the wretched creature was a mere dommerer who could hardly speak plain, but uttered for the most part animal sounds. The full details of the case are not clear.

I recalled that the anonymous author of “The Vampire Tradition” (the article pasted into a scrapbook in the Arnold Collection of the Providence Public Library) speculated that the tradition was brought to Rhode Island by “the French Huguenot settlers who lived at Frenchtown, below East Greenwich, in the early part of the eighteenth century.” What are the grounds for this connection? In his chapter on the Huguenots in Rhode Island, Bicknell is nothing but aglow with praise for these “people of singular purity and austere virtues.” He writes that it was a “suicidal act” for Louis XIV to revoke, in 1685, the Edict of Nantes, thus ensuring the exile of “the most valuable citizens of France,—artisans, scientists, men of learning and of good wealth, industrious, virtuous, freedom loving, law abiding men and women.” A possible motive for Rhode Islanders’ animosity toward the Huguenots, and, thus, a willingness to blame them for introducing ghastly superstitions, hinges on two events. It appears that the Huguenots were deceived by an unscrupulous group of land speculators (based in Massachusetts) and, as a result, almost all of them were driven out through continual harassment, including destruction of their homes and their church, by neighbors who had claims to land the Huguenots believed they had purchased. That, combined with the beginning of war between England and France, and perhaps religious prejudice as well, made the French Huguenots an unwelcome group, and convenient scapegoats.

I thought it might be worth looking through Lovecraft’s other works and was surprised—delighted, really—to see the village where I live, and its landmarks, mentioned in his short novel The Case of Charles Dexter Ward (1927-28). Following the trail of his ancestor, Joseph Curwin—a wizard and alchemist who abandoned Salem for Providence soon after the witch trials began—leads Ward to the ghastly discovery of Curwin’s pact with evil in the pursuit of immortality. Ward’s doom is sealed, as he is possessed by Curwin. Lovecraft writes into his novel a vampire scare in Pawtuxet Village that centers around Rhodes-on-the Pawtuxet, a community landmark from the Victorian era that still stands less than two blocks from my house. During the time of these nocturnal assaults, Charles Ward’s parents were becoming increasingly alarmed at his “haggard and haunted” visage, and his nighttime excursions. In fact,

most of the more academic alienists unite at present in charging him with the revolting cases of vampirism which the press so sensationally reported about this time, but which have not yet been definitely traced to any known perpetrator. These cases, too recent and celebrated to need detailed mention, involved victims of every age and type and seemed to cluster around two distinct localities; the residential hill and the North End, near the Ward home, and the suburban districts across the Cranston line near Pawtuxet. Both late wayfarers and sleepers with open windows were attacked, and those who lived to tell the tale spoke unanimously of a lean, lithe, leaping monster with burning eyes which fastened its teeth in the throat or upper arm and feasted ravenously.

Benefit Street is no stranger to either hauntings or horror writers. Nearly a hundred years before Lovecraft, the street was frequented by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), whose work Lovecraft admired and imitated. From the Providence Athenaeum at 251 Benefit (a favorite haunt of both Poe and Lovecraft), Poe often strolled the several blocks to the John Reynolds House (c. 1785) at 88 Benefit Street to visit Sarah Helen Whitman (1803-1878), to whom Poe was romantically attached. Just north of the Reynolds House, between Benefit Street and North Main Street, is St. John’s (formerly, King’s) Churchyard, a cemetery dating back to the early 1700s. Lovecraft wrote to a friend about feeling some vampiric presence and seeing a corpse light in the cemetery, experiences that recall the “almost luminous vapor” emanating from the cellar floor of the shunned house:

About the hidden churchyard of St. John’s—there must be some unsuspected vampiric horror burrowing down there & emitting vague miasmatic influences, since you are the third person to receive a definite creep of fear from it.… the others being Samuel Loveman & H. Warner Munn. I took Loveman there at midnight, & when we got separated among the tombs he couldn’t be quite sure whether a faint luminosity bobbing above a distant nameless grave was my electric torch or a corpse-light of less describable origin!

Lovecraft later wrote in a letter (1937) that “Poe knew of this place, & is said to have wandered among its whispering willows during his visits here 90 years ago.”

Poe, himself, wrote several vampire stories. His vampires are subtle, implicit, undesignated. In “The Oval Portrait” (1842), for example, the life essence of an artist’s model is drained as her portrait emerges on the canvas. The magical transference is completed at the final sitting, as the model dies and the painting assumes the vitality of life. But it is Poe’s short story, “Ligeia” (1838), that has New England parallels. “Ligeia” begins with a quote from Joseph Glanvill (1636-80), an English clergyman and philosopher who was chaplain to King Charles II, but, more to the point, also a believer in the spirit world and witchcraft. He refuted atheism by attempting to prove scientifically that witches and ghosts exist.

And the will therein lieth, which dieth not. Who knoweth the mysteries of the will, with its vigor? For God is but a great will pervading all things by nature of its intentness. Man doth not yield himself to the angels, nor unto death utterly, save only through the weakness of his feeble will.

The story’s narrator, after years of reflection, finds “some remote connection between this passage in the English moralist and a portion of the character of Ligeia”—his wife.

Early in the narrative, we get hints of Ligeia’s supernatural qualities: This woman of “strange beauty … came and departed as a shadow.” Then Ligeia grew ill, becoming pale with “the transparent waxen hue of the grave.” “Words are impotent to convey any just idea of the fierceness of resistance with which she wrestled with the Shadow … in the intensity of her wild desire for life … solace and reason were the uttermost folly.” On the day of her death, Ligeia asks her husband to repeat some verses she had recently composed. The last two were:

But see, amid the mimic rout,

A crawling shape intrude!

A blood-red thing that writhes from out

The scenic solitude!

It writhes!—it writhes!—with mortal pangs

The mimes become its food,

And the seraphs sob at vermin fangs

In human gore imbued.

Out—out are the lights—out all!

And over each quivering form,

The curtain, a funeral pall,

Comes down with the rush of a storm,

And the angels, all pallid and wan,

Uprising, unveiling, affirm

That the play is the tragedy, “Man”,

And its hero the Conqueror Worm.

Fleeing “the dim and decaying city by the Rhine,” the narrator repairs to the “wildest and least frequented portions of fair England,” where he meets “the successor of the unforgotten Ligeia—the fair-haired and blue-eyed Lady Rowena.” But he comes to loath her “with a hatred belonging more to demon than to man.” Like her predecessor, Rowena begins to languish. Emaciated and pallid, she suffers bouts of night sweats and fever that alternate with apparent recovery. Ligeia seems to haunt more than the narrator’s memory: “I had felt that some palpable although invisible object had passed lightly by my person … and I saw … a faint, indefinite shadow of angelic aspect—such as might be fancied for the shadow of a shade.” Then he becomes “distinctly aware of a gentle footfall upon the carpet, and near the couch” where Rowena was raising a glass of wine to her lips. In that instant, he “saw, or may have dreamed” he saw, “three or four large drops of a brilliant and ruby colored fluid … fall within the goblet, as if from some invisible spring in the atmosphere of the room.” Four nights after drinking the wine, the Lady Rowena is dead.

Watching the corpse of his newly dead wife, the narrator’s “passionate waking visions of Ligeia” are interrupted by a low and gentle sobbing. He turns to Rowena’s corpse to see that a slight “tinge of color had flushed up within the cheeks.” Rowena still lived! But before he can take action, there is a relapse: “the color disappeared from both eyelid and cheek” and “the lips became doubly shrivelled and pinched up in the ghastly expression of death.” This scene is repeated throughout the night, as Rowena appears to revive, then relapse, and the narrator is haunted by visions of Ligeia. Near dawn, the corpse stirred “now more vigorously than ever” and, “arising from the bed, tottering, with feeble steps, with closed eyes, and with the manner of one bewildered in a dream, the thing that was enshrouded advanced boldly and palpably into the middle of the apartment.” Transfixed, unable to move, the narrator begins to doubt the identity of the shrouded figure. He wonders, “had she then grown taller since her malady?” He approaches her. “Shrinking from my touch, she let fall from her head, unloosened, the ghastly cerements which had confined it.… And now slowly opened the eyes of the figure which stood before me. ‘Here then, at least,’ I shrieked aloud, ‘… can I never be mistaken—these are the full, and the black, and the wild eyes—of my lost love—of the lady—of the LADY LIGEIA.”

Poe’s Ligeia appears to share some features with the New-England vampire in a poem by Amy Lowell. In her lengthy narrative poem, “A Dracula of the Hills,” Lowell (1874-1925) shuns the European-derived literary vampire and turns, instead, to the New England vampire superstition. Lowell’s vampire, Florella, follows the traditional New England pattern, killing silently from the grave, beginning with her most beloved, her husband. Lowell’s dark, atmospheric story is set in western Massachusetts during the late 1800s. Like the other free-verse poems in her posthumous collection East Wind (1926), Lowell’s vampire narrative unfolds in the style of the traditional ballad, developed more through dialogue, rendered in dialect, than description, leaping from scene to scene, and lingering on the crucial episodes that move the plot towards its dramatic climax.

Becky Wales, the narrator, recalls an incident that occurred when she was a young girl living “t’other side o’ Bear Mountain to Penowasset.” While her good memories seem “all jumbled up together,” Becky relates that there are “some fearful strange things I can’t never lose a mite of, no matter how I try.” Whether you call it a custom or superstition (“ ‘Twarn’t th’ first time th’ like had happened, I know”), Becky says,

Seein’s believin’ all th’ world over,

An’ ‘twas my own father seed

An’ others besides him.

Because she was a young girl, she wasn’t allowed to view the ghastly act.

But I watched th’ beginning’s;

An’ what my eyes didn’t see, my ears heerd,

An’ that afore other folks’ seein’ was cold, as you

might say.

Florella Perry, “Fragile as a chiney plate,” contracts consumption and finally is confined to bed. As she withers, she vows:

“But I won’t die. You’ll see.

I’ll find some way o’ livin’.

Even ef they bury me, I’ll live.

You can’t kill me, I ain’t th’ kind to kill.

I’ll live! I’ll live, I tell you,

Ef there’s a Devil to help me do it!”

After “Dr. Smilie said ther’ warn’t nothin’ to do for her,” Florella “took a notion to see Anabel Flesche … a queer sort of woman … she lived in a little shed of a place over Chester way.” Despite Anabel’s knowledge of “herbs and semples … an’ things like that … Florella didn’t change none” but kept “sinkin’ an’ sinkin’ ” until “ther’ warn’t nothin’ lef’ of her but eyes an’ bones.” Becky’s mother and Miss Pierce “used to take it in turns to watch her.” The night before Florella died, Becky heard the whippoorwills and knew “Florella’s time was come.” Before she died, she “was jest plumb crazy … worryin’ ‘bout th’ life was leavin’ her, an’ all eat up with consumption.” Becky describes the sight of Florella’s corpse at the funeral:

I can’t a-bear to look on a corpse

An’ Florella’s was dretful.

Not that she warn’t pretty;

She was. Even her sickness hadn’t sp’iled her beauty.

She was like herself in a glass, somehow,

An old glass where you don’t see real clear.

‘Twas like music to look at her,

Only for her mouth.

Ther’ was a queer, awful smile ‘bout her mouth.

It made her look jeery, not a bit th’ way Florella used

to look.

Not long after the funeral, Florella’s husband, Joe, began to show the dreaded symptoms. When Joe reveals that he was consulting with Anabel Flesche, Dr. Smilie vows, “I’ll see that hussy stops her trapesin’… Rilin’ up a sick man with her witch stories … I’ll witch her, I’ll run her out o’ town if she comes agin.” One day, while Becky is on “death watch” for her friend, Joe, “all of a sudden crash down come Florella’s picture / on th’ floor with th’ cord broke.” Joe sees it as a death omen, that, “It can’t go on much longer.” Becky begins picking up the pieces when she notices that Florella’s picture has been cut, “All about th’ mouth too. / It make it look th’ way Florella’s corpse did an’ give me a turn.” Her fears that Joe would wake up and see the picture proved unfounded, for Joe never again woke up. Taken ill in Winter and dead by Autumn, Joe had gone down more quickly, and more peacefully, than his wife.

Soon after Joe’s funeral, Becky’s father encounters the witch, Anabel Flesche. She suggests, “in a queer, sly way,” that Florella loved life, and that “Joe’s gone, but ther’s others.” Taking Anabel’s hint, the father joins Jared Pierce in discussing the situation with the Selectmen. “Then some old people rec’llected things which / had happened years ago, / An’ puttin’ two an’ two together, they decided to see / for themselves.” At night, “so’s not to scare folks,” with lanterns, pickaxes, and spades they raise the coffin and open it.

Florella’s body was all gone to dust,

Though ‘twarnt’ much more’n a year she’d be’n

buried,

But her heart was as fresh as a livin’ person’s,

Father said it glittered like a garnet when they took

th’ lid off th’ coffin.

It was so ’live, it seemed to beat almost.

Father said a light come from it so strong it made

shadows

Much heavier than th’ lantern shadows an’ runnin’

in a diff’rent direction.

Oh, they burnt it; they al’ays do in such cases,

Nobody’s safe till it’s burnt.

Now, sir, will you tell me how such things used to be?

They don’t happen now, seemingly, but this happened.

You can see Joe’s grave over to Penowasset buryin’-ground

Ef you go that way.

The church-members wouldn’t let Florella’s ashes

be put back in hers,

So you won’t find that.

Only an open space with a maple in th’ middle of it;

They planted th’ tree so’s no one wouldn’t ever be

buried in that spot agin.

Lowell’s poem begs scrutiny. I wonder if Lowell, herself, saw any similarities between her Florella and Poe’s Ligeia? In some respects, Florella is like a Swamp Yankee version of Lady Ligeia. Both are strong-willed and unable to let go of life, determined to defeat death, even if it entails draining the life from the living. Ligeia’s conquest though, is more dramatic, as she saps the essence of her husband’s new wife, bodily supplanting her successor. Where might Lowell have learned of the vampire tradition? Born into a wealthy, aristocratic, and prominent family in Brookline, Massachusetts (very near Boston), and educated at home and in exclusive schools, Amy Lowell’s knowledge of the vampire tradition surely must have been secondhand. She wrote that her upbringing was “very cosmopolitan” and that “the decaying New England” had been “no part of my immediate surroundings.” Regarding the native Yankee, she admitted to being “a complete alien.” Fortunately, it didn’t take exhaustive research to find her source. In a letter to Glenn Frank, editor of Century Magazine, Lowell wrote in 1921: “The last case of digging up a woman to prevent her dead self from killing the other members of her family occurred in a small village in Vermont in the ’80’s. Doesn’t it seem extraordinary?” She said her source was the American Folk-Lore Journal.

Bing! A bell sounded in my head. Baughman’s folktale index, which had directed me to Charles M. Skinner’s tale of the insidious patch on the cellar floor, also listed an account from Vermont that appeared in the Journal of American Folklore (JAF) in 1889. Could the report below have been Lowell’s source?

Even in New England curious and interesting material may be found among old people descended from the English colonial settlers. About five years ago an old lady told me that fifty-five years before our conversation the heart of a man was burned on Woodstock Green, Vermont. The man had died of consumption six months before and his body buried in the ground. A brother of the deceased fell ill soon after and in a short time it appeared that he, too, had consumption; when this became known the family decided at once to disinter the body of the dead man and examine his heart. They did so, and found the heart undecayed, and containing liquid blood. Then they reinterred the body, took the heart to the middle of Woodstock Green, where they kindled a fire under an iron pot, in which they placed the heart and burned it to ashes.

The old lady who told me this was living in Woodstock at the time, and said she saw the disinterment and the burning with her own eyes.

… The old lady informed me that the belief was quite common when she was a girl, about seventy-five years ago, that if a person died of consumption and one of the family, that is, a brother or sister, or the father or mother, was attacked soon after, people thought the attack came from the deceased. They opened the grave at once and examined the heart; if bloodless and decaying, the disease was supposed to be from some other cause, and the heart was restored to its body; but if the heart was fresh and contained liquid blood, it was feeding on the life of the sick person. In all such cases, they burned the heart to ashes in a pot, as on Woodstock Green.

The details of this case don’t quite jibe with the brief description Lowell wrote in her letter. The Woodstock vampire was a man, not a woman, and the event, though reported in the 1880s, apparently took place some fifty-five years before, in 1834.

I searched the early volumes of the Journal of American Folklore (published quarterly, beginning in 1888) to see if I could find a better match. I did not. But I did encounter some items that made me wonder if Lowell had preceded me along this trail some seven decades before, looking for material to include in her two volumes of narrative poetry set in rural New England (Men, Women and Ghosts and East Wind).The 1891JAF included a note describing several death omens from New York’s Champlain Valley, near the Vermont border, including the call of the whippoorwill and the deathwatch. Five pages in front of this article, the poet James Russell Lowell, Amy’s first cousin, had contributed some nursery rhymes from Maine. Immediately following the Champlain Valley note was James Russell Lowell’s obituary. Three years later, a JAF article on New England funerals included an anecdote illustrating the custom of viewing the corpse. Young girls who were coerced into looking at the ghastly remains of a woman who had been burned to death had nightmares for weeks afterward. The article also related the common belief that death is foretold by “the falling of a picture from the wall, especially if it were the portrait of the same individual.” And, in “A Dracula of the Hills,” we once again encounter the widespread corpse light tradition, in the form of a light “so strong it made shadows” radiating from Florella’s tainted heart.

Amy Lowell’s high regard for the romantic poetry of John Keats (himself a consumptive) led her to write a biography of him. Certainly, she was well acquainted with his two vampire poems. Both “The Lamia” and “La Belle Dame sans Merci” were composed in 1816 and center around an implicitly vampiric female. In ancient Greece, after Lamia bears Zeus’ children, a jealous Hera kills them. In a rage, the spurned Lamia seeks revenge, feeding on the flesh and blood of the children of others. Lamia is a bogeyman in early folklore. Stories about her were told to control the behavior of young children. Tradition later transformed her into a shape-shifting succubus who could appear to young men as a beautiful woman. After seducing them, she sucked their blood and ate their flesh. It is upon this latter image that Keats based his poem in which Lycius succumbs to the shape-shifting lamia, who drains his vitality until he becomes like her and is finally saved, against his wish, by Apollonius.

“La Belle Dame sans Merci” takes the form of the traditional English and Scottish ballad, consisting of twelve, four-line stanzas. In this short narrative poem, a knight relates how he was enchanted by a beautiful woman, pale with “wild wild eyes,” and, after accompanying her to her elfin cave and kissing her, he fell asleep. He dreamed that he “saw pale kings and princes too, / Pale warriors, death-pale were they all; / They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci / Hath thee in thrall!’ ” He awakens alone on a cold hillside and finds that, he too, is pale and withering.

The romantic movement to which Keats was a strong contributor spawned an interest in indigenous cultures and ancient roots. Reacting against the ordered world of the Enlightenment and its belief in reason, romantics sought spiritual fulfillment, beauty and truth in the natural environment rather than the artificial world of the intellect. But, since nature also has a dark side, romantic fiction frequently went beyond the ordinary world to reveal a shadowy supernatural realm, tinged with horror, dread, death, and decay. A romantic writer, such as Keats, could explore the dual nature of humankind through an established figure of folklore, the vampire. He did not have to create, as Robert Louis Stevenson would later do, a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Perhaps Lowell’s choice of the specific “Dracula” instead of the generic “vampire” for her poem’s title is telling. The term “vampire” did not appear in the Journal of American Folklore articles nor in her letter to Glenn Frank in which she comments on the “extraordinary” custom. Did she make the connection herself? Or had she used other sources of the New England superstition? Her choice of the literary Dracula suggests that Lowell assumed her readers would know the novel and be able to link Florella with the Count. By the early 1920s, when Lowell had completed this poem, Dracula was well on the road to total domination of the vampire genre; the terms “Dracula” and “vampire” had become synonymous. How did this occur?

The New England vampire tradition, as incorporated into the works of Lovecraft and Lowell, has had no discernible effect on the popular imagination. Indeed, even the impact of the European folk vampire has been less formidable than we might believe. Although the vampire was a genuine figure in the folk traditions of Europe, and remained so in isolated areas of Eastern Europe well into the twentieth century, in the urban centers of Western and Northern Europe the vampire was known principally through written communication. And writing, unlike the malleable oral tradition, freezes texts and images.

Augustine Calmet’s recounting of the Arnod Paole incident of the early 1730s had an enormous influence on succeeding generations of writers. In 1746, he described, in Dissertation on Those Persons Who Return to Earth Bodily, how a series of unaccountable deaths in the Serbian village of Medvegia prompted a visit by a team of medical officers. Villagers claimed to have seen the reanimated corpse of Paole, an army veteran who broke his neck falling off a hay wagon. In their investigative report, Visum et Repertum (Seen and Discovered), the officers described the apparent vampire attacks on villagers and the exhumations of Paole and several other suspected vampires. When unearthed, Paole’s ruddy corpse appeared undecayed, there was fresh blood on his face and shirt, and he had grown new nails and skin. As the villagers drove a stake through his heart, Paole groaned and bled profusely. They burned his corpse and reburied the ashes. Legend has it that Paole, while on duty in Greece with the army, had been sucked by a vampire, an event that he eventually disclosed to his wife, Mina. (Is it coincidence that Mina is the name Bram Stoker chose for Jonathan Harker’s fiancée, later wife, who assumes a prominent role in hunting down Dracula?)

The vampires of literature have taken on some of the more sensational features of folk vampires, but they have become character types in their own right, designed to fulfill their Gothic mission of embodying the dark side of human nature. Even though no other literary vampire has matched the immense popularity of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897, several predecessors brought vampires into the world of art and entertainment. Coleridge introduced readers to “Christabel” in 1816, the same year that Keats composed “The Lamia” and “La Belle Dame sans Merci.” John Polidori’s The Vampyre, A Tale (1819) was extremely successful and, like the later Dracula, spawned numerous derivative works: plays, comic operettas, vaudevilles, and even operas. In this novel, Lord Ruthven is a thinly disguised Gothic villain with a thirst for blood. Most of his characteristics belong to literature, not folklore: Ruthven bites his victims’ necks to suck their blood, is immortal, pale, egotistical, influenced by the lunar cycles, and associated with Satan. He has supernatural strength, hypnotic power—which he uses to develop master-slave relationships—and he travels, sometimes great distances, in search of his prey. Like his mortal Gothic counterparts, the misanthropic Lord Ruthven is ruthless, immoral, vengeful, and world-weary. Another widely read vampire tale was Varney the Vampire or The Feast of Blood, a serialized thriller (with more than one hundred weekly installments begun in 1847) that might be regarded as a legitimate precursor to the “Dark Shadows” television soap opera. Sir Francis Varney bears a striking resemblance to Lord Ruthven: he is pale, with fang-like teeth and long fingernails, and he bites the necks of his female victims to suck their blood.

Stoker used these earlier literary models, as well as elements from vampire folklore, to create what became the prototype for all subsequent vampires of literature and popular culture. Even though the one-dimensional vampires of fiction pale in comparison to the diverse and colorful vampires of folklore and history, it is Dracula’s shadow that falls over the entire vampire landscape. (Actually, demons, ghosts, and ogres cast no shadows. Stoker’s Dracula to the contrary, folk tradition generally does not apply this characteristic to vampires.) Jennie and Paul Boldan’s version of the Foster vampire story reflects the length of Dracula’s shadow, which extends even to the remotest parts of New England. I have often wondered if it is possible to imagine a vampire without having Dracula’s image intrude.