ONLY BY GOING ALONE IN SILENCE, WITHOUT LUGGAGE, CAN ONE TRULY GET INTO THE HEART OF THE WILDERNESS.

—John Muir

The principal appeal of tenkara fly fishing lies in its simplicity, pared down to a rod, a line, and a fly. In comparison to western fly fishing, the amount of necessary gear is minimal. The small amount of gear you do decide to carry should reflect the water you fish, your inventiveness, and your comfort level. Take only what seems essential and fitting. Scrutinize everything. It must serve you, not burden you.

Modern tenkara rods are technological wonders. Carbon-reinforced polymers have revolutionized tenkara. These rods are amazingly light, have a high strength-to-weight ratio, and have a telescoping package that allows for compact storage. Modern tenkara rods typically weigh two to four ounces, and are generally nine to fifteen feet long, with as many as eleven sections. The handle or grip contains the telescoping sections, allowing for easy transport. The remarkable collapsed package is only fourteen to twenty-four inches long, perfect for carry-on luggage or an ultralight backpack.

There are a surprising number of telescoping rods in Japan, each aimed at a specific type of fishing. However, a tenkara rod by definition has a grip, and its length is effectively limited to fifteen feet or less. The grip and length limitation are necessary to provide a light, balanced rod, which is comfortable for the repeated casting needed for all-day fly presentation. Great care is taken to properly balance a tenkara rod.

Since tenkara rods have no reels, the line is attached at the tip. This may remind you of a cane pole, and, in many ways, a tenkara rod does reflect the cane pole’s simplicity. The grace and delicate presentation of the tenkara rod, however, supplied by its smooth application of power, far exceeds the cane pole or its poor cousins, the crappie pole and loop rod. The hollow, refined carbon modular components allow a transfer of force through the rod’s long lever arm, resulting in an almost effortless turning over of the line and fly. The rod actually becomes part of the flexing compound curve that turns over the line. Its tip, in the range of three hundredths of an inch (0.03"), is so flexible it becomes part of the cast. Indeed I have often said that the tenkara rod simply “launches a leader,” rather than a line.

Tenkara rods are rated by a ratio based on the number of stiff to supple sections. For instance, a 6:4 rod has six stiffer sections combined with four more flexible ones: the larger the ratio, the stiffer, or “faster,” the rod. When you “shake test” a tenkara rod, this ratio will predict the point of maximum flex. But keep in mind that the tenkara rod, particularly because of its length, is slower than traditional fly rods. This makes it ideal for short and delicate presentations.

A standardized method of describing a fly rod’s action in its entirety has not yet been devised. The “Common Cents System”1 is perhaps the most useful. When you choose your rod, remember that tenkara rods do not describe the same kind of compound curve as do fly rods. The so-called “action angle” is of little use in describing their speed. More useful, the ERN (Effective Rod Number) values that correspond to the weight of line in the western system roughly correlate with the “stiffness” of the tenkara rod. Measurements of a sampling of tenkara rods correspond with western rods, from a one-weight all the way to a six-weight rod. I prefer rods at the softer (lower) end for their ease in casting. A stiffer (higher) rod has the ability to manage larger fish but tends to need a bit more muscle in casting. For now, test casting a tenkara rod is the best way to match your particular sensibilities and style.

One particularly ingenious innovation of the modern tenkara rod is in its telescoping grip storage. This compact storage makes for one of the smallest packages in fishing even while creating one of the longest reaches. With a simple unscrewing of the butt cap, all the pieces can be removed for cleaning and easily and inexpensively replaced if damaged. When extending or collapsing your tenkara rod, be sure to push and pull in-line with the long axis; most damage occurs when collapsing the rod. Make sure the sections are snug, ensuring a smooth action, but don’t over tighten. Cleaning your rod from time to time with a soft cloth and drying it after a day on the stream is always a good idea, and can make for a nice, mindful conclusion to a fishing excursion. Gear readiness also makes your next spontaneous outing more likely. Lightly waxing the joining sections can aid the fit, making telescoping in freezing weather easier.

Tenkara rod grips are made from cork, wood, or foam. Wooden handles weigh the most, though some anglers like their balance or claim they transmit vibration better. Generally speaking, traditional cork is more practical, lighter, and causes less chafing. I prefer it. Foam is light and the least expensive, but can cause significantly more hand friction during a long day of fishing. Grip length is a personal preference, though longer grips allow some adjustment for near and far casting.

Carbon fiber naturally has a matte finish, though a glossy coating can be more attractive. It is doubtful that the reflectivity of such a coating spooks fish, although waving anything repeatedly above a fish will, of course, send it running for cover. Carbon fiber is an excellent conductor of electricity, so be careful around power lines and be aware of lightning risk. In an electrical storm, collapse and drop your rod. Carbon fiber will burn too, so never attempt to loosen frozen sections with a flame.

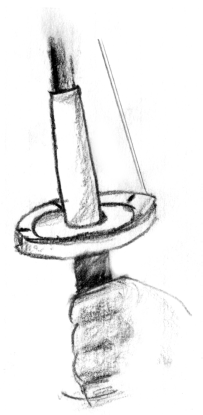

The tip of a tenkara rod has an epoxy-secured, braided line called a lilian.2 The line is attached to this line with a simple hitch, which transfers the energy of the cast with efficiency and grace. The lilian is traditionally red for visibility and is simply glued in place.

Tenkara rods may be the ideal fishing rod for a beginner of any age. With its ultralight weight, a tenkara rod is easily managed by even the smallest hands. In the absence of a reel, line handling is simplified, and having only a length of line a little longer than rod length decreases snags and tangles. Single de-barbed fishhooks are safer than trebled hooks, and with the feather-light fly, tenkara packs less of a punch than gear-heavy lure fishing. A light, stealthy fly presentation is almost guaranteed by a furled line setup. Lastly, tenkara rods are perhaps the most intuitive method of fishing with a rod. One naturally hooks and lands with a simple lift of the rod. The ease of tenkara rods have made them especially valuable to youth fly-fishing, scouting, and disabled veterans programs for the same reasons.

Given the simplicity of this gear, learning is intuitive and simple. The gear does not get in the way of the more important education: stream craft and the connection to nature. The productivity of tenkara encourages early success, and simplicity makes sure it is fun. By contrast, the learning curve of western fly fishing can be discouragingly steep. With tenkara a beginner can start on the water.

The tenkara fly line consists of only two parts: line and tippet. Depending on the needs of the stream and personal preference, a fisherman can modify several different elements in this basic combination.

Simply fishing a fluorocarbon line, like regular spinning line, works well, especially when fishing under the surface. It is inexpensive and easily obtained. Fluorocarbon line, because of its density, may allow for longer casts, since the line is less susceptible to deflection and less prone to straying in the wind. A ten- to eighteen-pound test line (diameter of .011 to .016 inches) is generally preferred, depending on the wind and water conditions. Ten-pound test is usually only suitable for light air, but does allow for a delicate presentation; a fifteen-pound test is a good compromise. When the diameter of the line is the same and not tapered, it is called a level line. One advantage of using a level line is that the length can be adjusted easily on the stream, shortening it for easier casting on brushy streams or lengthening it for a greater reach on clearer water.

Fluorocarbon, with its low refractive index, becomes almost invisible in water, which means fewer spooked fish. Tenkara fluorocarbon lines often have some tint, which aids in seeing your line when casting and seems not to greatly affect its underwater appearance. As we will see, tenkara is usually fished with most of the line off the water, and the thinner fluorocarbon diameter helps the rod in keeping the line high. In this case tint can be very helpful in detecting strikes. Fluorocarbon’s stiffness and density is also an asset, and is needed to cast easily.

Fluorocarbon can also be tapered in steps from thick to thinner, exactly like western fly lines and with similar characteristics. Indeed combining a stiff butt with a machine-tapered fluorocarbon line works quite well.

A few anglers combine a fluorocarbon line with a nylon intermediate section to allow for easy casting, yet some float. More commonly, a small section of brightly tinted nylon can be used as an indicator. Nylon monofilament3 as the sole level line, however, makes a poor substitute, with its coil memory keeping it from lying straight and low density making it harder to cast.

Many tenkara fishermen, however, prefer a tapered line of the furled or braided type, usually made from monofilament, synthetic thread, or fluorocarbon. Furled lines are made by twisting small fibers together like a double-braided rope. The number of small fibers can be adjusted and tapered with great precision. Furled lines have several advantages, and should be especially appealing to beginners. First, furled lines retain little memory, casting and transferring energy more smoothly than fluorocarbon. Lack of coiling allows a limper drop onto the water, and the air resistance of the furled lines almost guarantees that a fly will land lightly rather than splashing. Second, a furled line resists tangles and tailing knots better than fluorocarbon. For the beginner, untangling a bird’s nest of line is certainly a lesson in patience, though has little else to recommend it.

Furled lines are also more durable than fluorocarbon level lines and with care can last several seasons. They have a slightly higher cost, however, and perhaps higher visibility, though the latter seems to make little difference once you add several feet of tippet (the final section of very light monofilament to which the hook is knotted). The cost is certainly offset by its durability.

Some complain of line spray from a furled line, but this usually occurs only on a backcast. Of course, this is completely remedied with a false cast away from the fish. In reality though, line spray is not much of a problem with furled lines, and frankly, not much different from that which occurs with a level line.

Furled lines, because of their multi-thread composition, can spring back into a kinked tangle after pulling very hard against a tree-snagged fly. It looks worse than it is though, and can simply be “combed out” in less than a minute, simply by working your fingers down the length of the line.

Making furled lines is not difficult and allows you to control taper, weight, length, and color, as well as sink and floatability. It is also a way to save a few dollars if you have the time. (The making of single filament and furled lines will be discussed later.)

Though both level lines and furled lines have their fans, many tenkara anglers carry both. They use a level line if they need a longer cast or are fishing in windy conditions. They use furled lines if a more delicate approach is needed or if fishing in shallow streams. Because a simple hitch, easily released, is used to attach both, changing lines is simple and quick. When I teach, for instance, rather than waste time unsnarling a more complicated tangle, it is quite easy to quickly change lines and save the untangling for later.

A few tenkara fishermen use a floating, PVC-coated running line of the type made for western fly rods. The PVC line weight aids casting and the plastic coating releases easily from grassy streamside conditions. Even with the smallest diameters and weight, however, it is an easy line for fish to see, and the splash and visibility essentially sacrifice the advantage of tenkara’s soft presentation. The typical tenkara furled-line weight, by comparison, is about half the weight of a 000 fly line. Experimentation has also been done with mixed material furled lines, but the fluorocarbon level line and simple furled line remain preferred.

Attached to the business end of the line, as mentioned, will be your tippet. Tippet stealth becomes very important since the fly is attached directly to it. Use a light tippet to protect your tenkara rod, based on the manufacturer’s recommendations. With your increased ability to “nose” the fish, or control him, you may be surprised at how large a fish you can land on a tenkara rod and light tippet. The rod’s suppleness and length adds shock protection as well. Though rod flexibility does slow your hook set slightly, this is counterbalanced by increased sensitivity. In practice, quick hooking seems to be little trouble.

Tippet can be made of nylon or fluorocarbon, the latter being less visible and sinking more quickly, and the former stretching more and giving better shock protection. It is perhaps telling that most competitive anglers favor fluorocarbon for its stealth. If you fish mostly dry flies, however, a nylon tippet is less expensive, floats better, and is kinder to the environment. Please dispose of tippet scraps properly. As they say, “mind your mono.” Even biodegradable tippet may pose a wildlife danger for up to five years, while nylon lasts for much longer and fluorocarbon nearly forever.

Replace any tippet or line that is excessively worn and check your tippet for nicks after landing a fish, especially when playing it over rough streambeds and snags. If in doubt, replace it. Nylon is susceptible to ultraviolet degradation, so don’t store tippet in a sunny spot and replace your supply of nylon tippet each season. Fluorocarbon can safely be used for several seasons.

Tippet can be stored on the spool on which it is purchased. Rarely will you need more than one or two sizes, 5X to 7X being the most popular. Smaller flies and clear water conditions require the finer 7X tippet, while larger flies and fish favor larger diameter tippet.

When you are fishing frequently or are simply moving from one spot to another, leave your line and tippet attached to the lilian. Partially or fully collapsing your tenkara rod allows easier walking through brush and can be accomplished quickly without re-rigging. Keep in mind though that a partially collapsed rod is susceptible to breakage; if in very brushy conditions, collapse the rod completely.

When moving, simply wind the line around a tippet spool with the fly still attached. Then by simply extending the rod as you unwind the spool, you can go from the collapsed and protected rod to fishing in less than a minute. The spool can be stored on the rod by placing it over the collapsed shaft and snugging its center hole against the cork grip. This is the traditional way to carry it in Japan.

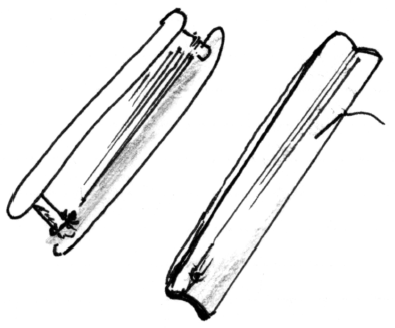

Instead of a spool, tenkara fishermen often wind their line on a “cast holder.” A cast holder was a traditional wooden holder in Europe and the colonies; the hook and line were wound in readiness for adding to a fly line or simply fishing by hand. A cast holder for a tenkara rod can be made out of a stiff piece of plastic, closed-cell foam, or light wood, anything around which the line can be wound. A groove in each end captures the point hook and the line windings. Commercial snelled-hook and dropper rig holders work too. Dropper rigs often come in a handy box, allowing you to keep a couple level lines and furled lines loaded and ready for quick changes.

The slight advantage of a cast holder over a spool when backpacking is that it can be slid, along with the rod, into a protective tube, such as the rod storage tube, a plastic mailing tube, or fluorescent light tube, protecting both line and rod from brush and snags. When hiking, I lash such a mailing tube to my trekking pole, which keeps the rod handy without interfering with the trekking pole’s function, even in the tightest brush.

The best solution I have found is to attach two removable hook keepers on the first part of the rod shaft. These keepers are easily attached with strong rubber O-rings, with which they are supplied. If you face them in opposing directions, they make for an easy way to store your line quickly on the stream, whether the rod is collapsed or partially extended. When not in use, the keepers retract and store against the rod, out of the way with nothing extra to carry. You can secure the hook behind a rubber band or hair elastic, though some anglers will simply embed the hook in the cork grip, something I cannot bring myself to do. I usually leave the line on these keepers when fishing frequently or when moving from spot to spot, ready to cast in seconds.

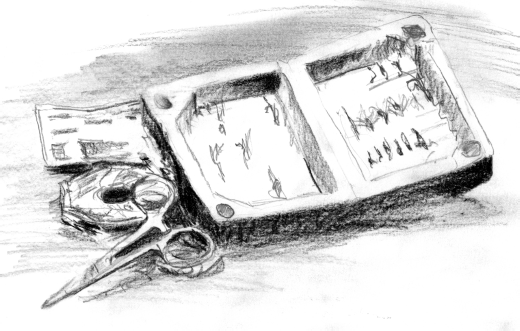

Fly boxes, of course, come in an endless variety. Almost anything you choose to store your flies in will work. As we will see later, the traditional tenkara fisherman carries a limited number of flies, sometimes based on tradition but always limited by simplicity. We are going to discuss flies a little later. For now, remember that even fly choice is influenced by tenkara’s philosophy of simplicity: Don’t overdo it.

To my mind, the weight of the box is the most important consideration. Simple foam fly boxes closed by small magnets have much in their favor. The fact that they float is another advantage, especially in swift water. I have found the magnets handy to temporarily hold a fly, too. Some boxes are better at protecting the hackles of dry flies—an important consideration. Boxes that have removable fly-threaders or nippers with threaders built in can be a great aid to those whose vision or dexterity makes tying on a fly tedious, and are more reliable than any other threading aid. They are quite expensive, however; most sewing needle threaders work fine and at a fraction of the cost.

Dry-fly floatant is rarely if ever needed in tenkara fishing. Dry-fly gels and aerosol sprays seem a needless complication when you are fishing the short drifts and shallow subsurface that characterize tenkara. Blotting your dry fly on your shirt or kerchief or a brisk back-and-forth false cast will dry your fly quite reasonably. Should we be introducing silicone and hydrocarbon mixes to our streams, no matter how small the amount?

A hemostat (more properly, a needle holder and not a forceps), especially with built-in scissors, is a convenient addition, the smaller the better as long as it fits your fingers. Sometimes there is no more effective way to remove a hook, and the cutting edge is generally all you need for line preparation, though some will insist on nippers (similar to a nail clipper and giving a finer cut). I like hemostats in black or with a quick spray of muting paint. Shiny metal will spook fish. I use the hemostat to tie knots quickly and with much more dexterity than I can manage with cold hands. (I’ll show you how to tie quickly with the hemostat in a later chapter.) I clip mine to my shirt pocket flap for easy access and have yet to lose one. Some people attach them to a zinger, a spring-loaded safety cord that can be pinned to a shirt or vest, but these seem to always end up wrapped around something. Nippers do better on a zinger than hemostats.

And speaking of vests, some anglers love the convenience and the multiple pockets of the fishing vest, as well as the traditional look. If you like them, search for vests that have simple and secure closures, with few line-snagging tags and very little exposed Velcro. They should also be lightweight and comfortable, especially around the shoulder and neck. “Shorties” enable you to wade into deeper water without soaking.

Rather than a vest, I prefer a small fanny pack, which easily holds all I need for a day on the stream, including lunch, a raincoat, and a water bottle. I twist it in front of me to access its contents. It has several small pockets to keep me organized, and a neck yoke to hold it higher and convert it to a chest pack for deep water. On shorter fishes when my truck will be near, I leave the pack behind; all I need fits in my shirt pocket. When I teach, I use a small chest pack that keeps tippet, magnifying glasses, and replacement flies handy. This is my preferred pack for canoe and kayak fishing too.

Shoulder bags are comfortable and have a traditional look, doubling as a creel if needed. They have a tendency to bang around a bit when hiking rough terrain, however, and can swing in front of you when bending over to land a fish. Bags with a belt or waist clip are better. Neck lanyards are rightly popular too, though an alligator clip to your shirt is needed to prevent similar swinging. They certainly keep everything handy, although having such a clatter of gear and tippet at the ready is not as pressing with tenkara.

A fish net can be a help in landing a fish, extending your reach and gaining control of a flopping fish more quickly than bringing one to hand. Soft rubber netting is easier on fish, and certainly heavily knotted cord nets are rough, and tend to snag fishing line and hooks. Japanese anglers favor a round net called a tamo with a short handle while Catskill anglers like a teardrop shape and slightly longer handle. Traditionally, Japanese include a bit of deer antler in their net design, thought to protect the angler on the stream. In the backcountry, nets tend to get snagged on brush easily. Capturing the net, with a rubber band on the handle, is a trick Gary Borger (the great fly-fishing instructor) passed on to me, and helps in avoiding snags, yet releases quickly. In the thickest of backcountry, nets are extraneous in my view, and many anglers dispense with them completely. From a boat or canoe though, nets are nearly essential. Proper handling is necessary with either method to ensure fish survival, such as wetting the hands before handling.

Adding bug juice, sunscreen, a lighter or waterproof matches, and an LED headlamp are sensible precautions. An emergency campfire in the backcountry has provided welcome warmth more than once, and a headlamp sure makes it easier to hike out in the dark. I also like to protect my hands from sun exposure with lightweight, fingerless gloves. (Skin cancers are most common on the back of hands, as well as forehead, top of the ears, and the neck area of the upper chest.) Polarized sunglasses and a hat with a dark, light-absorbing brim on the underside are a must, both to see fish and to protect eyes and face from sun and wayward hooks. Polarized lenses should have wide coverage and a way to get them out of the way when you need close-up vision; neck straps are fine as are clip-ons.

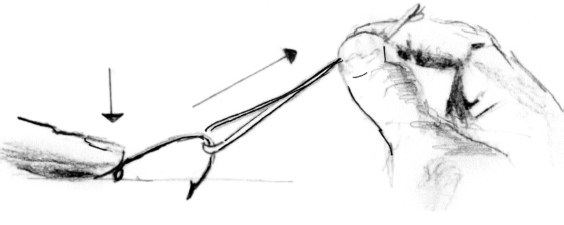

Accidental skin hooking does happen, and is much easier to remedy if everyone in your party uses barbless hooks. As a lakeside physician for many years, I’ve used the following trick hundreds of times and it is almost always successful, even with a buried barb. First, with fishing line or a shoestring, make a loop around the hook bend. Then as you push down firmly on the eye of the hook, give the loop of line an abrupt firm tug. The hook comes out almost pain free. But be careful . . . it can go flying.

Wading in the summer requires only an old pair of tennis shoes for foot protection. Dedicated wading shoes that drain and grip are better. Sandals, without toe protection, will sooner or later result in a laceration. Hip waders are perhaps the best all-around protection for small streams. Felt soles offer a slightly better grip, but rubber soles are much better for the walk in and they don’t ice up during late season fishing. Waist high or chest waders offer the most complete protection, and, especially in breathable fabrics, remain comfortable in the summer heat. Kneeling and squatting is drier in bibs too. All waders will leak eventually it seems, especially if you do much crawling. Knee protectors help, and shin pads additionally ease water pressure when wading fast water. Try the ones made for paintball; they even come in camouflage. One last option, which is great for backpackers, is the river overshoe, which pulls on over your hiking boots and makes very effective hippers. You leave your boots on so you don’t have to cache them somewhere streamside.

Invasive species such as didymo, zebra mussels, and mud snails and whirling disease are serious and growing problems for our waters and native fish. The trend away from felt soles, which can transport invasive algae and larva, toward rubber cleats is not a substitute for thoroughly cleaning and drying your gear. The most important step is to clean any mud or algae off your gear at streamside, with a brush if need be. Cleaning at home with diluted chlorine, full-strength vinegar, very hot or salty water, or simply allowing gear to dry five days will further prevent these dangerous hitchhikers. If you do use these solutions, rinse thoroughly to prevent gear damage.

Finally, you may want to consider a wading staff. I use the same carbon trekking pole I use for hiking, which has saved me from many a spill. Old ski poles are a cheap alternative. Consider a rubber tip or duct tape padding if your aluminum staff is a bit noisy. A simple wooden staff works too, but I don’t like to rely on streamside limbs, except in a pinch. Attaching a length of line between the handle of your staff and your belt allows you to drop the pole without worry, if you need your other hand to land a fish, for instance. With tenkara fishing, you can easily fish with one hand while steadying yourself with the other, unlike traditional fly fishing that requires two-handed line handling. Walking while casting is not a good idea though . . . both will suffer.

Cold weather fishing requires a few extras, including a change of clothes in a dry bag, gloves, and a pocket heat pack, which is admittedly a luxury. (Drop a heat pack into your waders for a quick warmup.) Winter fishing requires an obligatory thermos of coffee or tea, which does a better job of warming one than a flask of spirits. Of course the most important cold weather gear is the clothing you wear. Layers are important, as sweating can be as much a danger as getting wet. I think fleece is grand, but I won’t argue against your rag wool either. And for heaven’s sake wear a warm toboggan hat and give up your baseball cap in winter. A modern wool-blend sock, perhaps with a thin liner, is best for keeping your feet warm, which may be the first body part to get cold. Synthetic socks retain dampness inside waders.

There are many other gadgets that may add to your knowledge or enjoyment. A seine or fish-tank net (for sampling aquatic insects—a cheesecloth sack over your fish net works nicely too), magnifying loop, binoculars (I carry a 0.8-ounce monocular), and a stream thermometer can be interesting and fun additions. But remember, the more gear you take the more weighted down you will be and the more you can lose or break. More importantly, though, the more gear you take the more you will be tempted to fiddle rather than fish. I especially admire the angler whose kit is simple but whose approach to the water is elegant.

1. Hanneman, William, www.common-cents.info.

2. Likely a shortening of "lily yarn,” referring to the manufacturing method, patented in 1923 in Kyoto. Prior to this it was referred to as hebikuchi, or "snake mouth,” for its resemblance to the tongue of a snake.

3. The common convention of calling nylon line "monofilament” and fluorocarbon line "fluorocarbon” is used here, though both are single filaments of synthetic fiber.