THE COMMON EYE SEES ONLY THE OUTSIDE OF THINGS, AND JUDGES BY THAT, BUT THE SEEING EYE PIERCES THROUGH AND READS THE HEART AND THE SOUL.

—Mark Twain

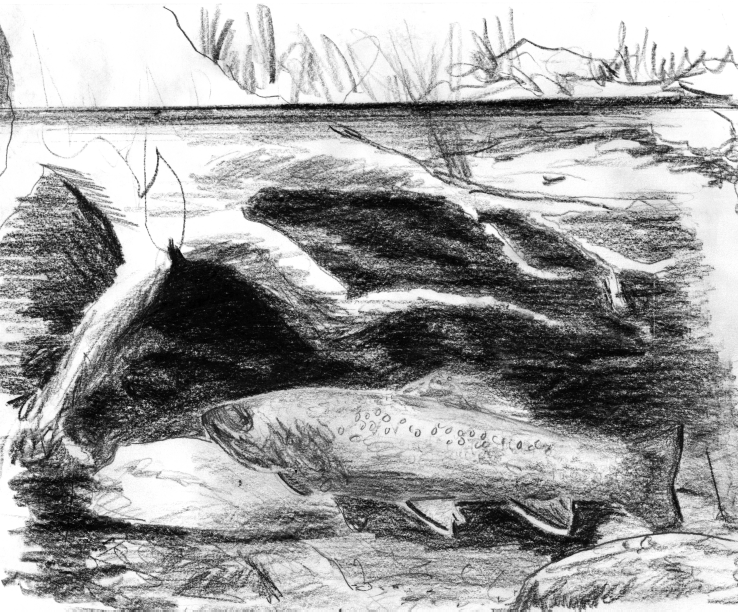

Have you ever navigated across a room in the dark, knowing where the furniture was without seeing it, and then finding the light switch? Subsurface fishing is similar. When you are fishing wet flies well, you are visualizing the fly as it drifts and swings underwater without seeing it or the fish. You anticipate where the best lies are as you guide the fly through these likely spots based on your reading of the surface currents, signs of underwater obstructions, the topography of bank and shade, and your intuitive feeling for the water. The best wet fly anglers develop a sixth sense about the fly’s location and appearance, and can often anticipate the take with consistent accuracy.

Subsurface fishing is ideal for the tenkara rod. Because of its long reach, the tenkara rod can stay in touch with the tiny movements of the fly all through its drift. Tenkara rods allow the angler to keep most of the line off the water, while leading the subsurface fly through the best lies. Because the majority of the time trout feed below the surface, subsurface fishing is usually the most productive type of fishing, day in and day out.

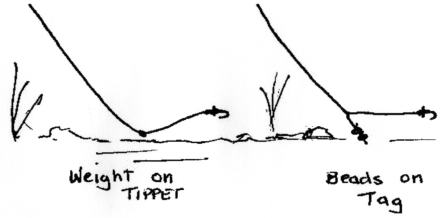

There are three basic types of flies used for subsurface fishing: the nymph, the Soft-Hackle wet fly, and the streamer. The nymph is a slightly tapered or cone-shaped fly, with thorax or chest larger than abdomen, some indication of legs, and generally weighted. The wet fly has a sparser body and uses undulating feather hackles to represent the actively swimming emerger. The streamer is a larger, streamlined fly, whose waving feathers or moving fur represents a fleeing fish such as a minnow or fry.

Tenkara allows for excellent control when drifting a nymph with the current. By casting upstream and keeping your rod tip nearly even with the nymph, tip held high, you should allow a small amount of tippet slack to be the lead for your nymph. Much like the leash on a dog, you want to keep track of things without losing control, yet allowing some slack, while tightening up from time to time. Keep your eye on this slack at the point where the line enters the water, as the nymph bounces and skips across the bottom. Watch the line for anything out of the ordinary, as takes near the bottom can be very subtle. With this cast you are nicely imitating an immature insect that has lost its grip on the bottom gravel and is tumbling into danger. Try hard to visualize this tumble in three dimensions. Add a lift of the rod tip, tightening the line, and you are imitating a nymph seeking the surface.

Fish feeding on nymphs typically lie in the bottom twelve inches of the stream. When fishing nymphs, be sure to use enough weight to get to the bottom. The faster the water, the more weight will be needed. Ideally the nymph itself had enough weight built into it when it was tied. This makes for an easier cast and lighter feel, a real consideration with a soft tenkara rod. I like bead-headed nymphs for this reason.

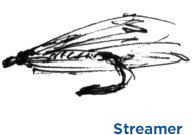

However, you can add split shot to a tag or on the tippet above a nymph. Putting the weight on a tag rather than putting weight above the fly on the tippet allows for slightly more sensitivity in the line, allowing you to more readily detect a bite. Shot on the tag will break off if snagged on the bottom, thus saving the fly. Glass, brass, and tungsten beads held on the tag with a jammed toothpick work well too. Placement of the weight no more than fifteen inches above the nymph helps ensure the nymph will stay near the productive bottom. Always use nontoxic shot; lead weight can kill waterfowl.1

When fishing nymphs, make sure to cast far enough upstream to allow the nymph enough time to sink to the bottom before drifting into the target zone. This is especially important with a tenkara rod, where you will have a somewhat limited reach. When casting heavily weighted nymphs, slow your upstream cast to avoid tangling your line; lob the weighted flies upstream. There is a fine line between too little and too much weight. Adjust the amount frequently if you are having little success. A few inches deeper can make a difference when fish are sluggish.

Remember as well that the heavier your tippet the slower your sink rate. Each transition to a thinner-diameter tippet lowers drag by 35 to 40 percent. With a heavier tippet it is more difficult to get to that target twelve inches. Fluorocarbon density also aids sink rate.

The tenkara traditionalist will eschew added weight, and indeed it does change the feel of the cast and drift. In moderate water, casting technique can compensate for less weight by casting further upstream. This allows a deeper penetration by the unweighted fly.

The Soft-Hackle wet fly wiggles through the water. The hackle is called “soft” given that it is usually made from hen or partridge feathers, more pliable than the stiffer hackles used in dry flies. Soft-Hackles are tied so that water pressure “works” them, alternately collapsing and expanding the feather collar. The wet fly is the most traditional of British chalkstream flies, but the Japanese have a traditional wet fly, too.

Japanese flies, or kebari, are generally so simple and versatile yet effective that they are the exclusive fly of some anglers. Different regions of Japan claim different styles of this fly, but they all have simplicity in common, both in construction and in fishing technique. Kebari flies are most often fished in the top six inches of water, and are cast somewhat harder to break the surface tension, then retrieved in pulses. If cast further upstream and allowed to sink, the kebari fly can be used to explore greater depths. Cast dry, it can be worked on the surface. With its variety of presentations, the kebari is a very versatile fly. Traditional tenkara flies have reverse hackles with the tips pointing forward toward the hook eye, increasing water resistance and providing for greater animation. The texture of the hackles can be used to alter the movement.

Wet flies use motion to attract fish, which allows them to be fished from the top to the bottom of the water column. Given that there is less concern for drag, they can be fished both across a stream and downstream. Fishing two or three wet flies on the same tippet is a traditional western means of increasing your odds. This lineup of flies gave the original meaning to a “cast of flies.”

The wet fly is usually cast across a stream and allowed to swing downstream. Lifting and dropping the tip of your rod causes the wet fly to follow. These gentle lifts can be done anytime during the cast but are very effective when approaching a suspected lie. Remember that a sluggish fish is like a sports fan in a recliner . . . he’s not going to move far to eat.

Though wet flies seem out of favor with western anglers, their adaptability, if not their venerable history, should keep some wet flies in your box. Besides, they work! The sensitive tip of the tenkara rod allows working these flies quite nicely. I predict that with the growth of tenkara, we will see a resurgence of the Soft-Hackle wet fly. The wet fly fisherman always stays alert with a “tight line” leading to the underwater rooms his fly is exploring.

Streamers are wet flies that resemble feeder fish, both in profile and motion. They are cast across a stream. Because feeder fish are the preferred food of larger fish, streamers are the first choice when prospecting for bigger fish. Streamers can be given a darting motion very effectively with the tenkara rod. Observing minnows in a shallow spot is a good way to picture the motion you are trying to create. Fish a streamer broadside to or slightly away from a suspected lie. (No frightened baitfish will swim toward a predator fish.) Streamers can be drifted, tumbled, twitched . . . just about any presentation you can imagine. I like a lighter dressing when fishing streamers with tenkara as they cast more gently. Just because the reach of a tenkara rod precludes the traditional stripping of line does not mean that streamers cannot be deadly efficient tenkara flies.

All of these subsurface flies can be fished with an indicator, too. In fact, indicators are a big help in faster water and for beginning nymph anglers, though you may find as you improve your fishing skills an indicator becomes optional. I use them regularly if the water is tumbling or riffled, as they help me see bites on a bouncing line and do not spook fish as badly when the surface is broken. An indicator is any float that suspends a subsurface fly at a specific depth or telegraphs its hidden motion (even if not suspending it). Plastic bubbles are a sturdy favorite for “heavy” or turbulent water while “corkies” are the cork or foam version. Both can spook fish in quieter water. Make sure the indicator you use can be moved up and down to easily adjust for depth, and use the smallest one that will work.

Using a buoyant dry fly as an indicator with a subsurface fly tied to the bend of the hook works well in lieu of an indicator. A grasshopper imitation is a common choice for the dry because it is large, floats well, and is easily followed. This combination is called the “hopper-dropper,” and can be very productive on warm days, with fish hitting either fly. Smaller dries like a parachute are used in quieter water.

Yarn added to the line will also serve as an indicator. The yarn can be captured in the knot joining the tippet to the line or tied to the tag of this knot, as well as simply forming a slip-loop mid tippet. For a movable method, tie the yarn to the line with another piece of tippet with a clinch knot or uni knot. Yarn tends to soak easily, though, which necessitates the use of floatant.

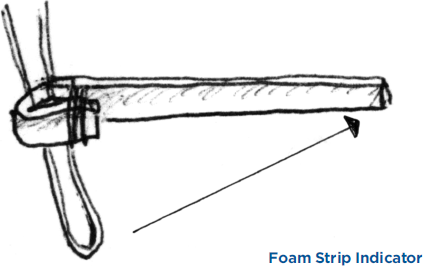

For tenkara nymph fishing in moderate water, you can use a foam-strip indicator. To make your own, cut a one-and-a-half-inch to two-inch strip of closed cell foam in the color you prefer, about ⅛ to ¼ inch wide. Fold over one end and whip it with thread. When fishing, feed a loop of line through the foam loop as shown. (Hemostats can be inserted through the stretchable foam loop to grab the line.) Loop the line over the bulk of the indicator and tighten. Leave the loop in the notch of the short leg. This makes it easier to move and prevents kinking. With a heavily weighted fly, two strip indicators set a foot apart work well. A strip indicator is very sensitive and casts well while not requiring floatant, and the direction it points gives important information about the drift.

Tie in a small section of brightly tinted monofilament before the tippet for another easily followed indicator, or better yet two colors in series to give you a sensitive visual display on sly takes. Setting a coil of heavier monofilament in this section (a five-minute boil followed by an overnight freeze with the line wrapped tightly around a bolt will do it) makes it especially visible.

There is evidence that Japanese tenkara anglers may have used floats in the past, and I have found them very useful in helping beginner anglers catch their first fish. The tenkara angler should not feel pressed to do without them. However, most tenkara anglers will jettison them eventually, opting for the increased sensitivity and ease of casting that is found with a light and less “gear-laden” line. The short distance to your fly and ultrasensitive rod tip makes this transition easier than it sounds. Concentration is, however, an essential ingredient.

Immature insects are found underwater all year long, and fish do seem to be less wary while they’re feeding underwater. Fish mostly prefer the bottom, and will often feed on a nymph drifting at their level even when they won’t cruise to another level to feed. With less light penetration, fly imitation underwater is easier too. A fly that gives just a general impression of food will often be taken where a dry fly would have resulted in refusals.

The best anglers focus on the area of water through which the fly is moving, the line where it touches the water, and the feel transmitted through the sensitive rod tip to the grip. Keep as much line off the water as possible. This is one of the major advantages of tenkara fishing, so practice holding the line away from the surface. Drag remains important underwater, so lead the fly with a bit of slack tippet when dead-drifting a subsurface fly. Any unusual movement in the fly could result in it being refused. As you drift the fly, look for an excuse for a quick, hook-setting motion, especially when you think that fly is drifting through a likely spot. I am surprised how often a subtle bump turns out to be a bite when responded to quickly. Some nymphing instructors say that you should arbitrarily hook-set at least once during the drift. Fish can nibble gently underwater, and we likely miss as many as half or more of the bites. After all, underwater prey can’t simply fly away. The shadowed depths give fish the home court advantage.

1. Lead sinkers (not just bird shot) are a major cause of death in loons, cranes, and swans as demonstrated by autopsy studies at Tufts University, Sidor et al. 2003 and Pokras et al. 2008.