When was the last time you tried something on in a shop under fluorescent lighting and emerged wanting to hang yourself from the nearest rack of skintight jeggings? Although it may alarm passing children, let’s face it, they have to find out about mortality one way or another. Meanwhile, your dreams of pulling off a leather minidress were just crushed by the iron fist of reality as you caught sight of your reflection in one of those disturbing three-way mirrors that allowed you to see your profile in all its chinless glory. Suicide is seemingly the only viable option.

It’s a sad fact that, although most women have never uttered the immortal words ‘Does my bum look big in this?’ – mainly because it’s such a terrible cliché – pretty much every woman (even, we suspect, the Victoria’s Secret Angels) has at one point said or thought, ‘I hate my body’. Words like ‘I’m so ugly’ or ‘I’m so fat’ come tumbling out of women’s mouths with alarming frequency, confirming everything that we’ve been led by the media and its cycle of insecurity-mongering to believe about ourselves: as though we are born vain, insecure and self-obsessed as a sex, rather than moulded that way. After years of our bodies and their individual parts (camel toe, cankles, sideboob, bingo wings, et al.) being viewed as legitimate topics, is it any wonder that some of us engage in body-shaming ‘fat chat’ with our friends and loved ones?

Blokes apparently don’t worry about such trivial things: if and when they develop the frown lines and porcine bellies of middle age, it merely lends them a jowly distinction that commands the respect of man and beast alike: just look at the Cabinet! Of course, in reality, there is an escalating pressure on men to conform to certain body types as well, but the most piercing scrutiny has always been fixed firmly on the gals: our (hopefully large) breasts, our (hopefully tiny) waists, our (hopefully fulsome but rock-hard) bums, and everything in between. Magazines take an instructive role, claiming to be able to teach you everything you need to know about being a woman, before presenting you with a parade of bodily problems which need ‘fixing’, and then laying on advertisements for miraculous products which can supposedly do just that. Indeed, Mitchell and Webb’s excellent parody advert captured just how many things advertisers can find wrong with your body: ‘Women: you’re leaking, ageing, hairy, overweight and everything hurts, and your children’s clothes are filthy. For God’s sake sort yourselves out’ (the men’s slogan was ‘Men: shave and get drunk, because you’re already brilliant’). Such advertising is so heavily oriented towards women’s innumerable ‘problem areas’, and so pervasive, that you’re a fully paid up lady consumer before you know it: a lady customer who knows that the only way to remedy her flaws is to spend, spend, spend – and the only way to know what to buy is to read yet more magazines.

Meanwhile, despite the fact that the size of the average woman in the UK oscillates between a 14 and a 16, we’re force-fed the notion that there’s nothing better than being skinny. Magazines such as Closer ruthlessly document the yo-yo dieting of D-List celebrities and always ensure that there’s a ‘bloated’ bikini body on the cover. Other magazines hammer home the fact that your body is a work in progress, and reassure you that you can guarantee yourself a ‘flab-free holiday’ by following 832 simple steps. A Danish television show called Blachman, after its creator Thomas Blachman (‘the Danish version of Simon Cowell’, according to the Telegraph) even made body-bashing its central premise in 2013: a naked woman would stand before a panel of (male, fully clothed) judges while they delivered merciless feedback on her body, cellulite and all. A May 2013 article in Time magazine stated that ‘Blachman purportedly created the show to get “men discussing the aesthetics of a female body without allowing the conversation to become pornographic or politically correct.”’ Oh, and did we mention the fact that the woman under review isn’t allowed to speak?

Despite what Thomas Blachman may think, male scrutiny of the female body in the media is not lacking: it is, instead, very much in hyperdrive. How has this state of affairs become so normalised? Perhaps you buy into the idea that a trickle-down from porn has led to the shiny, plastic, hair- and cellulite-free bodies we’re confronted with on every billboard; or perhaps you think that the ageism of Hollywood and the fashion industry has more to answer for – but either way, as they say at Alcoholics Anonymous, the first step is admitting we have a problem. Unfortunately for women, certain men have always regarded our bodies and our ladyparts as common property, to be prodded and ogled and lusted after like sexy livestock at an agricultural auction, and as women have come closer to achieving equality with men, the pressure we are under to embody unrealistic physical ideals increases exponentially.

In today’s visual media, the objectified female body is so prevalent that many of us don’t even notice it any more; we just accept our decorative status as fact. Most lasses we know wouldn’t blink an eye at the average grinding, frotting, rutting sweaty sex-fest of a modern pop or hip hop video, or think twice about Jay Z’s assertion that he collects ‘Money, Cash, Hoes’ (despite the fact that money and cash are the same thing). A fleeting glance at a stack of US-based Seventeen magazines proves that women are ‘trained’ to accept objectification from an early age: one 2013 cover had ‘Find your BEST LOOK INSIDE’ (‘make-up artist tricks & more’) juxtaposed with ‘THE HEALTHY DIET’ (‘look and feel better in just 2 weeks’) and ‘How to be a great date (and get asked out again!)’, deliberately collating beauty, dieting and social acceptance. Another issue of Seventeen ran ‘SPRING BEAUTY SECRETS’ (‘sexy eye make-up, hot new lipsticks’) above ‘DOES HE LOVE YOU? Find out now’. It sounds like the stereotype of a middle-aged housewife’s paranoid mind from a Dear Deidre strip, but it’s the cover of a magazine beloved by America’s young teens.

So how did we get here, to the self-hatred in the changing rooms and the public figures vilified for not doing their hair right, and the ‘sexy eye make-up’ tips that will make somebody love you? It seems we stood by fairly sedately as the standards of beauty in media outlets, helped by a great big dollop of photoshop, became increasingly difficult and then impossible to emulate. It happened gradually; we took it all in our stride. And then one day we looked up at the doe-eyed, gazelle-legged movie star on the latest billboard whose digital manipulation had gone so far that she was almost indistinguishable from the cartoon beside her, and realised that no human in the world – including the woman who posed for the picture – actually looked like that, yet the magazines are telling us we need to spend our lives vainly pursuing that ideal. And so we all continue to nod along, pinching the fat on our thighs resignedly as we refuse another cheesecake; or we keep silent.

Reading a contemporary women’s magazine is often like waiting for an insecurity bomb to go off. One minute you’re looking at a nice harmless little feature about a group of women who set up their own coconut yoghurt factory, and then – BAM! – you and your enormous, gelatinous arse are running for cover as giant capitalised letters implore you to ‘Take your butt to bootcamp’. Then just as you’ve recovered and have turned over to find out about a new kind of dance meditation that everyone in showbiz insists you have to try, the second bomb detonates with an almighty CRASH because they’ve said your thighs should be no wider than eighteen inches in circumference and yours are twenty-freaking-five. Before you know it, you’re lying face down in a puddle of your own tears and wondering how many pounds you’d lose if you amputated your legs from the knees downwards. Woman’s Own once ran a front cover with a radiant, smiling Dawn French, dressed up for a press event, splashed across it. The accompanying text was: ‘Dawn – FAT AND OUT OF CONTROL? PLUS: Fern and Denise – their skinniest bodies ever!’ If that’s not enough to make you cry at the counter, what is?

Meanwhile, the UK government has had to resort to sending out leaflets to parents to advise them on how to talk to their children about body image, because young children cannot differentiate between bodies that are photoshopped and ones that aren’t – and most adults can’t either. By the time a girl is 13, magazines are telling her ‘love your body, but try this diet’, in preparation for a complete and utter indoctrination by Cosmo and Glamour, who’ll print saccharine articles on body confidence and the importance of self-esteem, and then whack them next to a cosmetic surgery advertorial. Confused? You’re not the only one.

Picture the scene: you’re 13 or 14, maybe even younger, and all hell is breaking loose in your body. Somehow, pubes have started sprouting overnight, your nipples are in agony, and you’re bleeding from that hole in the middle that you weren’t even totally ready to believe existed yet. Copiously. In fact, your vagina is basically Stalingrad. Every time you look in the mirror, the war seems to have broken out on a different front. You’re developing lumps and bumps in places where previously there were none and you’re grouchy and irritable, and massively hormonal. Your mum doesn’t understand you and, on seeing your first bout of virgin acne, feels it appropriate to announce to the dinner table that you’re just ‘going through puberty’ but ‘still look pretty underneath, despite the obvious’. And if that wasn’t bad enough, a strange foreign animal species called ‘boy’ that smells vaguely of Lynx, knobcheese and Hubba Bubba is starting to show an interest in you through the tried-and-tested methods of insult and torment (usually by asking you why you haven’t got any tits and then pinging your bra strap while his other hand readjusts his knackers). If you could, you’d sleep 18 hours a day and never talk to anyone again. No one speaks to you the way that Courtney Love/Alanis Morissette/Avril Lavigne/Lady GaGa/Taylor Swift does (delete according to age and taste). It’s no wonder so many of us end up backcombing our hair, throwing on an oversized crucifix necklace and becoming goths for a couple of years: being a teenage girl is shit.

In the midst of that adolescent whirlwind, just as your strange new body is being transformed into that of a woman – whichever sort of woman your genetics have already dictated that you’ll be – you’re told that you should either be aspiring to have the skinny, bony frame of a child, or be transforming yourself into a pneumatic pornstar with tits the size of melons and a bald vagina not unlike the one you had before your pubes hit. That we live in a society where young teenage girls who are not even fully developed yet are begging their mums for a boob job makes us want to down our seventh gin and grow a penis (which could, in all fairness, make for a spectacular night on the town).

It’s not as though baby girls emerge from the womb already hating their podgy thighs, yet a study by University of Central Florida professor Stacey Tantleff-Dunn and Sharon Hayes published in the British Journal of Psychology in 2009 showed that half of 3- to 5-year-old girls worry about being fat, and that by age nine, half of them have already been on a diet.5 We can just see them in the back garden now – ‘No mud pie for me, ta, a moment on the lips means a lifetime on the hips!’ – and it’s not a pretty picture. The same piece of research found that girls between the ages of 11 and 17 cite ‘looking good’ as their number one aim in life; once this mindset is developed, advertisers quickly jump in to define exactly what ‘good’ is, before the girls have time to think for themselves.

We live in a world now where we are able to vote and work and even sometimes run whole countries, so hasn’t feminism achieved its goals? Where’s the beef? Well, our main point of contention is that, while we’re technically allowed to do all these things, we’re still supposed to have a cracking cleavage while we’re doing them. (A man, meanwhile, can be a political tour de force while simultaneously looking as rough as a badger’s sphincter. But we’re mentioning no names.) If you have the audacity to be a woman and walk around cultivating a prominent career for yourself, it’s pretty much taken as read that your appearance will be used by the media to discredit you. Take the website HillaryUgly.com, which was set up to mock Hillary Clinton for being ‘one ugly old Hag’ with ‘ideas … even scarier than her looks’ – or the cover of the New York Post which ran an unflattering picture of her angrily discussing Benghazi politics with the headline: ‘No wonder Bill’s afraid’. Or perhaps the numerous women’s magazines that ran ‘Margaret Thatcher style’ features in the wake of the former Prime Minister’s death, yet neglected to mention any of her policies. Or the comments made by the leader of the Liberal and Democratic Party in Russia, who stated that US diplomat Condoleezza Rice was an ugly woman whose political stance on Russia is negative because ‘this is the only way for her to attract men’s attention’.

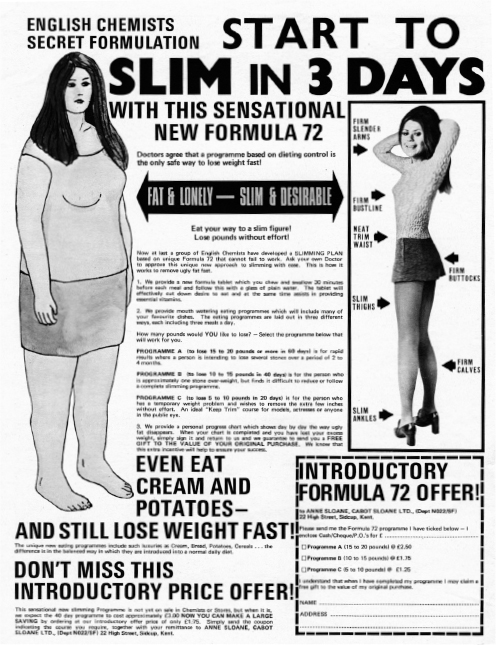

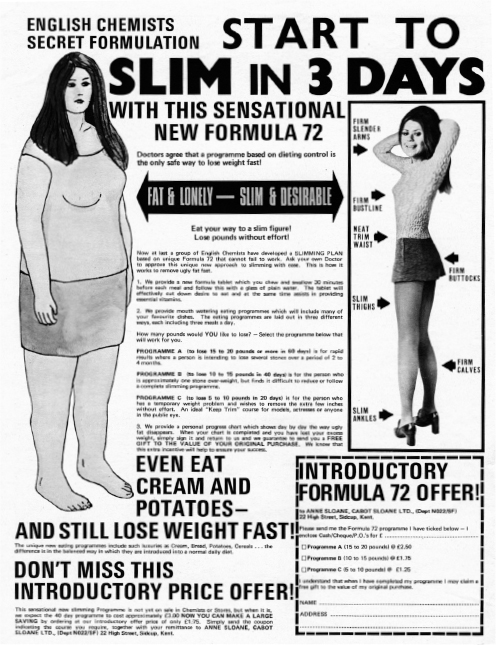

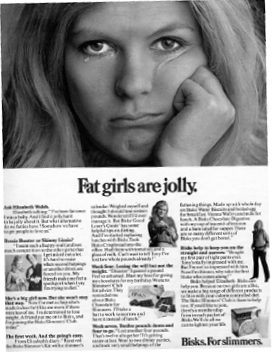

The fact of the matter is that ever since women became a target group for those shadowy suits known as advertising executives, the media have been creating a lack of body confidence and then using the resultant anxiety as a marketing tactic. One advert for Palmolive from the 1950s shows a drawing of a woman sitting in front of a mirror and carries the strapline, ‘Most men ask, “Is she pretty?” not, “Is she clever?”’ (Just in case you were unsure as to where your life priorities should lie.) Indeed, the 1950s were prime time for advertisers hell-bent on insecurity-mongering and their campaigns created neurosis wherever they went. They interrogated the magazine readers of the time, shaming them for every natural bodily process going, asking product-oriented questions that included: ‘Does your husband look younger than you do?’, ‘Why couldn’t Grace get partners? Because her nervousness and worry brought on NERVOUS B.O.’ and ‘YOU, 5,000,000 women who want to get married: how’s your breath today?’ No wonder poor Grace was so sweaty.

Meanwhile, over twenty years later when the feminist revolution was supposed to be well under way, Black & Decker, which at that time made exercise machines, gave us a pretty hefty taste of ‘same shit, different decade’ with a bitchy ad that read: ‘Are you twice the woman your husband married?’ Nice. The thing is, that when you look at these adverts they can seem charmingly quaint and retro. ‘Ha ha!’ you chuckle, ‘How silly and ignorant those advertisers were back then. Thank God we’ve all moved on.’ But look a little closer, beyond vintage imagery’s current trendy status, and you’ll realise that advertisers’ tactics have barely changed. In the last few years, magazines have run adverts for diet pills and plastic surgery that used the taglines ‘I hated every kilo on my body’ (diet pills advertised in Reveal magazine, April 2012) or ‘I just had my breasts done, but the biggest smile you’ll see is on my face’ (Transform Medical Group’s adverts for plastic surgery, plastered across the London Underground and Cosmopolitan magazine throughout 2012).

We’re not saying we’re against cosmetic surgery as a choice per se, but it becomes less of a choice and more of an imperative when every picture of a woman that you see is trying to convert you to surgery with the persistence of an airbrushed Jehovah’s Witness. What does send us on a trip to Outrage Mountain, however, is the notion that it’s the only option. Magazines tend to opt for some simpering twaddle to disguise this, such as the unforgettable line in Glamour magazine: ‘Let’s get one thing straight: at Glamour, we don’t want you to have plastic surgery. We love you (and ourselves, thanks) just the way you are’, before undoing it all by going on to say ‘all the experts we spoke to confirmed that, in the right patient, at the right time, aesthetic procedures can have powerful positive outcomes’, and advertising five different Harley Street clinics in the back pages. Much like your ex-boyfriend, Glamour doesn’t really love you at all. It only wants you for your body, and you deserve better.

The revelation that advertisers and magazines create our insecurities as a selling tactic is nothing new, but their cynicism does seem to have jumped up a notch. In late 2013, media news outlet Adweek reported on research which revealed when female consumers are at their most insecure. This turned out to be Mondays, a ‘good time’ to market ‘quick beauty rescues’, apparently. And magazines not only try to capitalise on your existing insecurities but also create new ones (‘back fat’, anyone?) until you become dependent upon them for cures for all your horrible flaws. Without them, you’re on your own: a fat, unattractive loser who has no idea what probiotic frozen yoghurt is and thinks ‘free radicals’ either means a nineties band or a Cold War era film about communists on the loose. ‘We’ll be your friend,’ they bleat from the supermarket racks. ‘We’ll show you how to pass in this crazy world, how to wear the right clothes, discuss the right topics, and eat the right foods.’ Much better to pick up the latest copy and join the body-trashing ranks. As keen consumers of women’s magazines ourselves, we both noticed that the more we bought them, the worse we felt about our bodies.

Magazines’ obsession with women’s bodies at the expense of their minds is obvious. We once counted 45 ‘body terms’ used in a single issue of Cosmo (words such as ‘bum’, ‘thigh’, ‘curves’, ‘figure’), compared with 9 ‘mind terms’ (‘mind’, ‘brain’, ‘think’, ‘thoughts’) – and that wasn’t an unusual edition, by any means. Their obsession becomes your obsession, and once they’ve created it within you, they live to feed it.

So how can you go about spotting this confidence-damaging content in magazines, especially when it can be so subtle that your brain doesn’t even notice it’s soaking it all up like a sponge until it’s punishing you in front of the full-length mirror later? The first step is understanding their tactics. A prime example of their cunning bitchiness is the way magazines and newspapers will call a woman ‘curvy’. ‘Celebrity X celebrates her new curves!’ the headline will say, giving the impression that the article is about body acceptance and female empowerment, when in fact the main text alludes to ‘yo-yo dieting’ and ‘struggles with weight gain’. While ‘curvy’ may initially have been used as a way to describe larger women without being downright rude, it has now become a catch-all term for anyone with a little bit of flesh on her bones. The Mail Online has even taken to referring to pregnancy as ‘getting curvy’. Another classic is the phrase ‘womanly shape’ or ‘real woman’, as though having a ‘non-womanly shape’ makes you some kind of fake mannequin woman masquerading as human. Size 8 Daisy Lowe famously referred to herself as ‘curvy’ in a Grazia interview in early 2013 (‘Being skinny doesn’t suit me’), having previously done so in the Daily Telegraph back in 2010. It was surprising to hear a successful, slender model talk about going to shoots ‘where the clothes didn’t fit and you feel horrendous about yourself’, but her admission that she loves being ‘curvy’ seemed to provoke a kind of curvy warfare, with the Telegraph choosing to pick up the story with a piece entitled ‘Daisy Lowe is not “curvy”, says fellow model Zara Martin’. People tied themselves up in knots to decide whether ‘curvy’ meant ‘curvy’ or not. Was Daisy fat-shaming herself? Are size 8 girls allowed to call themselves ‘curvy’ if it’s actually a euphemism for plus-size? You may well think that you give zero fucks, but it turns out that enough people care to make a mini media storm.

What’s even more perplexing about the use of terms such as ‘curvy’ is the fact that by the early noughties, body fascism had become so universal that any woman going about her business who didn’t look like a malnourished size zero was immediately lavished with praise for her ‘body confidence’. As Kim Kardashian has regularly demonstrated to us, simply being a female with an arse has become a noteworthy occupation (if you’re taking a ‘belfie’ of it, even better); the same with Christina Hendricks and an ample chest. Being a celebrity with a ‘womanly figure’ means having shit-tons of journalists praise you for the ‘bravery’ and ‘individuality’ you exhibit simply by owning a pair of tits. It seems that, if you’re not busy lamenting your cup size and your unwilling membership of the Itty Bitty Titty Committee, then your hourglass figure is being flaunted as proof that you’re courageous. It’s a D-cup, darling, not a battle with leukaemia.

Advertisers realised that it was high time to cash in on all this ‘body acceptance’, and launched the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty (perhaps that’s a bit of a cynical take on it, but hear us out). The campaign focused on celebrity photographer Rankin’s portraits of ‘real women’ (not all those skinny bitches who apparently don’t count) with insecurities that, it was implied, had been developed by the beauty industry. One demonstrably slim young woman who featured appeared with the tagline ‘Thinks she’s fat’. Another poster showed underwear-clad women of all sizes cavorting together in wondrous merriment like a basket of puppies on adoption day. ‘Dove has liberated us from the shackles of media expectations!’ they seemed to cry, as they let their love handles jiggle wild and free. Despite the fact that one of these campaigns was for a cream that supposedly smooths out cellulite (because we all know that is simple enough to shift), at least the portrayal of diverse body types spearheaded by Dove could be seen as one step in a positive direction. Unfortunately, however, nothing seems to have changed very much since then, and certain corners of the media continue pitting various female body types against one another and labelling them either ‘real’ or fictitious.

A particularly insidious form of body-shaming subjects women to the scrutiny of ‘trained celebrity nutritionists’. Nice, normal women are photographed in their bras and pants before being called fat and ugly in a variety of backhanded ways by a team of pseudo-scientific ‘experts’ with a printed-out qualification from the College of Body Contouring Remedies. ‘You need more wheatgrass in your diet,’ they’ll say, clutching their empty clipboards. And they’re not the only ones who seem to know what’s best for women’s bodies while covertly feeding them expensive poison.

Then there are the leading questions. Women are often asked, ‘What’s your least favourite part of your body?’ or, ‘What’s your ideal celebrity body?’ as part of PR-led surveys for nefarious companies, which then end up recycled and regurgitated and placed in amongst the genuine news: ‘65% of British women detest their noses!’ the headline will say, when in fact it’s nearly always just 65% of the women who happened to be passing a certain spot on that particular Saturday afternoon, a spot which, coincidentally, is just around the corner from the rhinoplasty clinic that they were heading to. Next, there is the kind of feature where a couple are interviewed about each other and the guy gets ‘Does your girlfriend prefer her bum or her boobs?’ while the girl is asked ‘Does your boyfriend prefer the James Bond franchise or Tarkovsky?’

It’s not just the shape of your body that you should be paranoid about, however, it’s also the way it smells. In 2013 ‘intimate wash’ company Femfresh had to pull its ‘Woohoo for my FrooFroo’ campaign after a massive social media backlash (which, let’s say, we were not uninvolved with) during which the company’s Facebook page was swamped with ‘VAGINA’ comments and a hefty serving of future suggestions for Femfresh flavours, including ‘houmous’ and ‘mojito’. People were angered that they were being told their vaginas were somehow naturally dirty, when in fact they are far more inclined towards self-cleaning than testicles and penises (and yet wiener cleaner is not available on the market). The rule of thumb that ‘if the guys aren’t doing it, it’s probably sexist’ applies here.

It’s as though the media want us in a constant battle with the processes of our bodies, as though they want us to remove all traces of anything natural, such as body hair or crow’s feet or freckles, to become a doll-like version of femininity. These bodies exist in a world where when you get your period blue liquid comes out, cystitis is non-existent and no one ever, ever gets the kind of yeast infection where you’re constantly crossing your eyes as well as your legs and cutting every conversation short to resume your quest for a toilet cubicle in which to scratch yourself to oblivion.

In the eyes of these magazines, these advertisers, these executives, a woman is only the sum of her squeaky-clean parts (and sometimes, owing to the over-zealous use of Photoshop, they aren’t even her own parts). As a result, she becomes piecemeal, fragmented: a collection of boobs and thighs and bum and waist and calves, as though these body parts are somehow separable from her. Women such as Germaine Greer and Susie Orbach have been saying this for years, of course, but nothing has really changed. In fact, it’s getting worse. The overwhelming message is that a woman’s individual body parts mean more than she does. Take Cosmo’s ‘50 great things to do with your boobs’ (because, y’know, you have the time), an article which implies that your breasts are such fascinating appendages that you’ve been searching for years for a way to maximise their usefulness. Unfortunately, the magazine’s ‘boob fun’ suggestions were nowhere near as fun as those of our readers, mainly because Cosmo’s, funnily enough, all seemed to revolve around men (‘Put temporary tattoos of his name around your nipples, and give him a peek when you bend forward in an undone button-up’). Not nearly as enjoyable as one reader’s suggestion, which was to ‘get an arty friend to paint them with a leaf design then hide topless in a hedge’. (After all, if you’re going to spend a significant part of your life worrying about your body parts, you might as well use them to conduct interesting experiments now and then.) The point is, they’re our breasts, and we don’t need an instruction manual full of helpful suggestions and rainy day activities to help us enjoy them (especially when we can just take them to a gig), just as we don’t need to call our vaginas ‘minkies’ in order to talk about them, because we’re not six-year-olds). And, while this may all seem fairly trivial, it doesn’t take a procession of justifiably disgruntled pro-choicers holding up placards to politicians saying ‘Keep your rosaries off my ovaries!’ to remind you that women’s bodies are still considered everyone else’s business – and no more so than when it comes to the humble vagine.

Whether it’s another majority-male debate on abortion in the White House or the House of Commons, a pharmacist telling you that you should have kept your legs closed when you’ve gone in for the morning-after pill, or another tedious Vagisil advert, everyone’s got something to say about your vagina and what you do with it. Getting all its hair torn off is commonplace; labiaplasty is now de rigueur, and we’ve paid hundreds of pounds in VAT – or ‘tampon taxes’, if you will – here in the UK, because the stuff needed for your monthly visit from Aunt Rose apparently counts as ‘luxury goods’ in the eyes of the government (they were, however, kind enough to lower the VAT rate from a whopping 17.5% to 5% in 2001. Yippee.) Go ahead and luxuriate in the feeling of shedding your womb lining, girls – you deserve it.

But the interest in what’s inside your knickers doesn’t end there: anti-abortion campaigners will openly debate whether the rights of an adult woman not to be penetrated against her will by a vaginal ultrasound are less important than the rights of the month-old foetus living in her womb, and certain politicians seem fetishistically obsessed with our vaginas, telling us what should be going down up there. It’s surprising any of us even bother to continue taking off our knickers of a Friday night (don’t say we’re not troopers). Indeed, the man calling for vaginal ultrasounds, US Republican Ryan McDougle, considered himself an expert on the inner workings of women’s bodies until his Facebook page was inundated with vaginal updates (‘During my last period, I had to use the Super tampons because I had some chunky blood issues. Do you know anything about that?’). Others of the McDougle ilk have been overwhelmed by hand-knitted uteruses (uteri?) sent anonymously through the post: craftivism at its best. As a wise American woman once said during one of these protests, ‘If I wanted the government in my vagina, I’d fuck a senator.’

So what is it exactly that makes everyone so loose-lipped about labia, and where will this obsession with our vaginas end? For a while it seemed that the appearance of your vag, safely encased as it was in a pair of pants (most of the time, at least) was beyond reproach, even if the rest of your body was dissected by media moguls. What (and who) you did with it sexually was, and still is, another matter, but if you fancied cultivating a massive 1970s bush then that was your prerogative. But it was not to last, and partly since the skyrocketing growth of the adult entertainment industry in the 1980s and ’90s, we’re now at the point where even our vaginas are supposed to represent porno pussy perfection and, as a result, a variety of products and treatments have sprung up. (Vajacial, anyone? It’s like a facial, but for your vagina. Cos that’s, like, totally your other face.)

In 2011 and 2012, a number of advertising campaigns in Thailand and India appeared which hinted strongly that women would be more desirable to men if they bought vaginal whitening products (seriously) because shades of brown just make for a vulgar vulva, sweetie. Meanwhile, a ‘genital cosmetic colorant’ (vag dye, basically) called My New Pink Button was being marketed in the English-speaking world as a way to get back the ‘youthful’ colour of your flaps and ‘increase sexual confidence’. As one reviewer drily noted, ‘I would never buy this product. Instead I like to get a sick thrill from skulking around in the shadows, tricking men into my beige vagina.’ We don’t know about you, but the colour of our clits never really factored in to our sexual confidence. We were too busy worrying about whether the ‘happy pancake’ really was a sex position (it is, apparently) and whether the condom had wiggled to the end of the guy’s knob or not, rather than whether or not we had fifty shades of grey labia. But if we don’t come back at the onslaught of these ‘developments’ with a massive ‘I DON’T CARE’, while wielding a big vagina-shaped tennis racket to bat this load of balls out of the court, then they’ll keep trying to convince us that we do.

Just to top off the mountain of ‘WTF’ vajayjay-changing products out there, the particularly brazen company Ultratech also suggested that they had made a ‘vaginal tightening cream’ in 2012 to reinstate that oh-so-fetishised state of female virginity. If that’s not enough to turn your stomach, maybe the fact that it was called ‘18 Again’ will – or try YouTubing the commercial, featuring an actress singing that ‘it feels like the first time all over again’ (because that’s a sexual experience every woman out there is just gagging to repeat). Meanwhile, plastic surgeons the world over offer the ‘beautification’ of vaginas and ‘reattachment’ of hymens, despite the fact that, in our personal experience, losing your hymen is about as pleasurable as having someone rap your knuckles with a frozen veggie sausage. It is now routine for surgeons in the US to perform labiaplasty operations, because it’s such a lucrative business, and feminist and medical groups have argued in the last few years that such procedures, which can lead to recurrent bleeding, infection and permanent scarring, should count as genital mutilation. In 2011, there was even a ‘Muff March’, organised by campaign group UK Feminista and performance art group The Muffia, down Harley Street, London’s plastic surgery haven, in protest. At the dawn of the ‘designer vagina’ craze in the early twenty-first century, the NHS reported that double the number of labiaplasty operations had been performed in one year (2006) than had been performed during the previous four.6 In 2013, WhatClinic reported a 109% increase in enquires regarding the operation, while The Cosmetic Surgery Guide reported that 24% of their female readers would be interested in hearing more about vaginal rejuvenation. Clearly, this one is a continuing trend.

Like most new products for women, this veritable smorgasbord of idiocy came with the promise that it was the latest ‘solution’ for females. Funnily enough, we didn’t know we had half of these problems in the first place, but when we’re surrounded by these messages daily, we start to believe that our bodies have flaws that do need fixing. And nowhere has a campaign to ‘solve’ women’s bodies been more successful than in the case of hair removal.

You might be forgiven for forgetting that a natural part of puberty for women involves growing thicker, darker hairs on their legs, ladyparts and underarms. After all, magazines are full of pictures of smooth, shiny, hairless women and any female celebrity who has decided to do something more important than get the razor out is immediately lassoed with a magazine circle of shame or declared part of a ‘Celebrity armpit hair face-off’ (Metro, July 2012), like Julia Roberts and, more recently, Pixie Lott. Poor old Pixie was even subjected to the headline ‘Pixie Lott explains why she was flashing armpit hair on the red carpet’, followed by the tagline ‘Popstar doesn’t seem embarrassed by her red carpet fail’ in Reveal, despite the fact that she’d merely accidentally shown some stubble while posing with her hand on her hip as opposed to, say, parading through the premiere with hirsute arms in the air and a women’s rights placard over her naked breasts (although that would have been amazing). Dare to suggest that any fuzz might be allowed to stay in place – barring, perhaps, a small triangle perched above the labia charmingly known in beauty salons as ‘the landing strip’, useful in a world of increasing ambiguity to signify that you actually have sat your Year Nine SATs – and there will be an outcry.

Thanks to pre-teen exposure to magazines, learning the word ‘pubes’ comes hand-in-trembling-hand with ‘Veet’ and ‘tweezers’ and ‘G-string wax’: just consider the fact that Uni.K.Wax salons in the US held a promotion offering 50% off waxing for the under-15s back in the summer of 2012. The world of women’s grooming is mad keen to point out that if you’re going to have sex, you’re going to have to make sure you look the part, and that includes pubic grooming. Much affectionate fun has been made of the teenage boy’s first shave, bound as it is to leave a few blood-soaked tabs of toilet paper in its wake, but little has been made of the shamefaced tiptoe of the teenage girl into her parents’ bedroom to seek out Daddy’s razor blade and apply it to her newly furry areas. Sure, aftershave stings (we imagine) – but try ingrown hairs along your knicker line, cuts near your sexy parts, and the itch of regrowth in a place God never intended to itch when healthy and functional. The jumpy 17-year-old who eventually deflowers you will most likely forget to glance down anyways but be prepared in case he does, lest you break his spirit with your untamed lady-garden and consign him to a lifetime of hysterical celibacy.

The anti-pube brigade dictates that women should look basically prepubescent all the time; ideally even when they’re knocking on for the menopause. We’re not saying that how you choose to tame your minge isn’t your choice (believe us, we couldn’t care less what you do with your pubes), but the suggestion that landscaping the front garden is now absolutely necessary for a normal sex life is so prevalent that it’s become an obligation. If you’ve ever seen porn, you’ll know that the acceptable pubic hairline is rapidly receding. This all ties in with the shiny, vacant, sterilised version of sex that the media and its delinquent cousin pornography sell you.

We’ve both fallen prey to the brigade ourselves in the past. Having bought some budget own-brand waxing strips as part of a two-for-one deal using her pocket money, the intrepid 15-year-old Rhiannon waited until her mother was out and then locked herself in the bathroom. She applied the wax strip to the left half of her nether regions, but as soon as she actually grasped the reality of what she was about to do, she suddenly lost every ounce of plucky resolve and became too frightened to tear it off. An hour later, after several tentative attempts, she finally ripped it off like a plaster, screaming blue murder. She was stuck with the resultant half hairy/half baldy fanny for weeks. And there’s not much better waiting for you in a salon, where Holly fainted during a particularly brutal ‘G-string wax’ at the embarrassing age of 21. It’s another situation where the ladies are under pressure to do something that the boys aren’t (sexism alert), and yet, in our experience, men never seem to respond well to suggestions that, if they want a smoothy-smooth snatch to play with then they should respond in kind by removing all their bollock hair. If it hurts more than your last heavy period and you need a hot water bottle and a good cry afterwards, then it’s not just a beauty routine, whatever the sadist with the electrolysis machine tells you.

For women to show any hair from the neck downwards has always, to an extent, been frowned upon, especially pubic hair, which, as a sign of rampant sexuality, has long been regarded as immodest. Indeed, nude depictions of women in painting often neglected to feature pubes (though it should be noted that upper-class Victorian lovers gave one another their pubes as souvenirs). However, there wasn’t really any attempt to control what the masses did with their body hair until the early twentieth century, when sleeveless dresses came into fashion and unshaven underarms suddenly seemed obscene. This was closely followed by legs, then, with the advent of the two-piece bathing suit, V-zones, back in the time when the phrase ‘bikini line’ hadn’t even tunnelled its way out of the glossy pink woodwork, never mind the concept of a vajazzle.

It was US magazine Harper’s Bazaar, targeted at the ‘better sort’ of women, that published the first advertisement warning against fanny fuzz in May 1915. Back then, ads were still getting into the swing of subtle manipulation, so they just went out there with a pretty straightforward message. ‘Summer dress and modern dancing combine to make necessary the removal of objectionable hair’, read the snappy tagline – despite the fact that body hair had never been ‘objectionable’ before. The late-Edwardian ‘fash pack’ pushed the idea that a ‘woman of fashion’ would never be seen compromising her new sleeveless outfit by daring to bare hair, and slowly this message trickled down to most women in North America, the UK and, yes, despite the hairy stereotypes, France (where a ‘landing strip’ is referred to as a ticket metro) – though surely French feminist group La Barbe, committed fans of novelty hair – which the BBC delightfully described as ‘fighting inequality with sarcastic humour and fake beards’ – are sure to be vociferous in the defence of their bearded clams.

But why is fanny fuzz such an issue at all? When we published an article on the Vagenda website written by our friend Emer O’Toole describing how she had turned her back on the razor, the response was overwhelming, and while lots of readers praised our contributor’s straight-up attitude to her hairy bits, just as many reacted against her decision to boycott the whole shebang. The controversy surrounding one young woman’s thoughts about her armpits, legs and fanny was such that she made national headlines, showed off her pits on This Morning, and was even asked to do a topless shoot by that classy tabloid the Sunday Sport (she said no, FYI). If we needed proof that women’s bodies were still subject to dizzying levels of social judgement, then this was it. Body hair is, after all, just a natural part of being an adult: dye it, braid it, pull it out, sew charming Yuletide scarves with it. But if you really, truly find it revolting to the point of disturbance, we invite you to go ahead and watch a ‘back, sack and crack’ waxing session (if you can ever find a willing live male to undergo it in front of you). The resulting mess looks like a passionate night in with honey gone wrong, and when a slightly furry fanny turns your stomach more than that, you must be truly chaetophobic.

Many would argue that their decision to wax or not to wax is their choice, and on the most basic level it is. But there doesn’t seem to be much out there in the way of pube positivity – the anti-muff brigade is certainly winning. Bikinis are embroiled in a bitter dispute with the postage stamp to see who can take up the least space in the world at any one time, and for many years the Brazilian wax was the rule rather than the exception. Once upon a time, the ‘muffstache’ was something it was considered poor taste to mention in polite company, but now you’re expected to be porno-perfect in preparation for that close-up money shot at all times. In this day and age, most beauty therapists seem to privately consider you a bit of a hippie if your waxing regimen hasn’t included getting on all fours and allowing them to get acquainted with the minutiae of your bumhole. With that much societal pressure, coupled with the fact that we hardly know anyone who will freely admit to not shaving, the decision to remove the hair isn’t so much a decision as an imperative. Perhaps it’s time to say a muff is a muff (sorry) to the notion that pubic hair is somehow repulsive or disgusting, and to the myth that only after a close shave, a bit of colonic irrigation, and a sesh of bleaching your arsehole (preferably not in that order) will your privates be just about decent enough to get intimate with.