My work is like the light in a fridge. It only works when there are people there to open the fridge door. Without people, it is not art, it is something else: stuff in a room.

Liam Gillick, 2000

SUBJECTIVITY

a kaleidoscope endowed with consciousness…

Charles Baudelaire, 1863

Whatever responses artists may be seeking from the viewing public, most would agree with Liam Gillick that the bodies and minds of the persons who pass through and interact with the work are the essential, sentient elements that complete the work. Claire Bishop is one among many who has emphasised the importance of the gallery-goer in the development of installation art. Fundamental to its practice, she says, is a common ‘desire to heighten the viewer’s awareness of how objects are positioned (installed) in space, and of our bodily response to this’.1 She emphasises works that stimulate viewers’ senses, particularly those faculties associated with orientation, whilst simultaneously orchestrating audiences’ subjective responses, engaging them in a healthy exercise in self-awareness. While these broad outlines are useful, a number of questions remain unanswered: who is looking at an artist’s work? What determines the viewer’s response? While a deeper examination of the ideas enlivening our understanding of identity, cognition, perception and consciousness is beyond the scope of this volume, I will briefly signal my own allegiances as I have periodically tuned in to the discussion. We have already touched on the psychoanalytic model of spectatorship that turns on audiences temporarily identifying with the illusory world onscreen. We might reject the Cartesian model of the self, summarised by the philosopher Paul Snowdon as an ‘immaterial, spiritual ego, related to the body but separate from the body’.2 We may, instead, adopt a purely physiological approach, and subscribe to Antonio Damasio’s concept of a ‘protoself’ rooted in the theatre of the senses. According to Damasio, our responses are mediated by the work of ‘a coherent collection of neural patterns, which constantly map, moment by moment, the state of the physical structure of the organism in its many dimensions’.3 A cybernetic system of proprioceptors and neurons is responsible for the viewer’s understanding of her position in space and the nature of what surrounds her. As we have discussed, this corporeal operating system is what militates against total immersion in the illusionism of film, what keeps our feet on the ground. If the senses orient us in space, what constitutes the interpretive mechanism that assesses what we see, hear, smell and feel? We conventionally imagine an inner theatre of the mind where we locate the ‘I’ of consciousness, that endogenous viewer who observes and decodes the world conjured up by the senses. However, this notion goes against the thrust of scientific argument of the last thirty years. In her essay ‘Mysteries of the Mind’, Susan Blackmore, a firm believer in the pre-eminence of science in general and neuroscience in particular, scorns any whiff of Cartesian dualism and confidently asserts: ‘The show, the theatre and its inner observer are all illusions.’4 There is no unified self, separate from its own physical make-up, and the age and state of health of the human organism will determine its waxing or waning capacity to interact with its surroundings. This view promotes the search for the key to consciousness in the infinitesimal mappings of our physiology achieved by the combined revelations of DNA, our body chemistry and the ever-more acute probing of MRI scanners. Science, which has long-forgotten the theory of the four cardinal humours (blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile), now tells us that our bodies are made up of about 60% water, and our minds are nothing but the effect of electrical and chemical changes geared to the optimum survival of the organism. I will explore further this mechanistic view in my discussion of cognitive science and the moving image in chapter twelve.

Other correlational theories of the self propose that we exist only in a web of social and cultural connectivity. Modelled to some degree on Richard Dawkins’ ‘selfish gene’ and the networked signifying regimes of structural linguistics, the viral theory of memes configures individuals as staging posts for ideas, entities that, in succession, are infected by an itinerant concept. The subject is modified to a greater or lesser extent by the meme and then passes it on.5 It is easy to become depressed by a belief in the cultural helplessness of the de-centered being, vulnerable to every passing injunction of cognitive capitalism pitched by advertisers, politicians, entertainers or online entrepreneurs.6 The more recent arguments of speculative realism offer little comfort; they too roundly condemn any theoretical position that might incorporate an autonomous, active subject.7 Within the logic of speculative realism, objects are given the same weight and value as human beings, or rather, people are reduced to the status of objects in an sea of inanimate entities. In this flattened universe, J. J. Charlesworth concludes: ‘there should not be much of the subject left of which to speak’.8 Confronted by another attempt to annihilate the individual, this time centred on ‘the extreme negation of subjectivity’,9 I find myself instinctively drawn to John Locke’s seventeenth-century notion of identity as a construction based on the persistence of consciousness and memory over time. Even more reassuring are the recent postulations of Steven Shaviro, who argues that ‘every object retains a hidden reserve of being, one that is never exhausted by, and never fully expressed in, its contact with other objects’10 and, one could add, in its contact with culture and its institutions. The new feminist materialism offers a vision of the interconnectedness of matter and culture, language and biology, and Michael Hames-Garcia configures the subject and her body as ‘something more than an inert, passive object on which ideology inscribes meaning, but rather it is an agential reality with its own causal role in making meaning’.11 In earlier chapters, I have emphasised the influence of cultural and political forces, the impact of the Althusserian ‘state apparatus’ on the development of a human being; and I have acknowledged the ability of cultural artefacts to interpellate the viewer. However, for the purposes of this discussion, I will conceive of the subject as instantiating a unique coincidence of physical and psychic attributes, framed by historical and socio-political circumstances, and endowed with varying propensities to resist or be altered by an experience of a moving image installation.

THE IMPERFECT SPECTATOR

Malcolm Le Grice has lamented the loss of concentrated attentiveness to the moving image in an installation context, which, he says, is ‘not a good one for anything that has any temporal development’.12 As a result, spectators will respond predominantly to ‘concept and idea’ rather than seek out an ‘engaged experience’.13 The splitting of attention between multiple dimensions in a gallery can indeed render us imperfect spectators. The diffusion of awareness, or what Peter Osborne calls ‘psychic attention in dispersal’,14 is not limited to the connoisseur of moving image installations. The grazing TV viewer dozing off on the couch at home is engaged in a similar ‘distracted reception’ as is the young couple at the cinema, dividing their attention between the film, the popcorn and their mutual gestures of affection. Siegfried Kracauer writing in 1926 suspended his earlier celebrations of mass spectacle and condemned the superficiality of the sensory experiences engendered by both film and modern life. Even if the spectator is naturally inclined to an active engagement with art, film images, like the dizzying impressions of the teaming metropolis, ‘succeed each other with such rapidity that there is no room left for even the slightest contemplation to squeeze in between them’.15 Kracauer portrayed the viewer ensconced in a gilded picture palace, enslaved to the senses at the cost of the intellect – the over-stimulated body eclipsing the Socratic soul. In Society of the Spectacle (1967), Guy Debord reconfigured spectatorial captivity along an axis of desire. He charted the progressive alienation of the social subject, transformed into a compulsive agent of consumption and floundering in a sea of appearances. The spectator of film was condemned as merely ‘a consumer hungry for thrills’.16 Moviegoers were said to be divorced from reality as they indulged their ‘lust for the eye’, a circulating desire that can never to be satisfied. Spectatorial attention had scattered, and the quality of that attentiveness, the criticality of the viewing subject, was seen to be compromised by modernity with its high turnover of irresistible enchantments.

The denigration of the spectator was not, however, universal. Michel de Certeau, for instance, argued that the ‘distracted’ viewer was not so much a lobotomised consumer of culture as an active user of cultural products.17 Consumers have long repurposed popular culture and commercially produced artefacts for their own ends. To borrow de Certeau’s notion of a book as a ‘rented apartment’ for the creative enterprise of the reader, a cinema, a TV set or gallery space is also literally a hired space for the spectator’s internal and interpersonal transactions. This leads us to the multiple functions of spectatorial engagement; not only can the landscape of the imagination find enrichment in mass entertainment, but the TV viewer or gallery-goer may be simultaneously interacting with her family and friends around the shared experience of a show. The young couple partaking of an evening at the cinema are building memories of their own and exploiting the darkness to progress their courtship, aided no doubt by the film’s romantic scenario mingling with the lovers’ dreams of a conjoined future. They will participate in the social bonding that proceeds from the experience of communal laughter and tears. The gallery-goer may be equally active in her encounter with a moving image installation, especially if she is an artist herself and is attending a private view when, in parallel with her appreciation of the exhibit, comparisons to her own practice become inevitable, and social interaction and ‘networking’ take place, a process indispensible for her career progression.

THE SPECTATOR: SEEING DOUBLE

In the cinema, I am simultaneously in this action and outside it, in this space and out of this space. Having the power of ubiquity, I am everywhere and nowhere.

As I have argued, our appreciation of the filmic elements of an installation mobilises our ability to read the moving image both as a material phenomenon and as an ‘other’ reality in a recessed, illusionistic space. We maintain the two forms of knowledge concurrently, drawing our conclusions from these enmeshed conditions of understanding. It is in early childhood that we learn the skill of inhabiting two worlds simultaneously, when we first hear fairy tales and ascribe to transitional objects identities beyond their material condition: a doll becomes a baby, a bear a trusted friend, a toy pirate a sworn enemy.19 Bruno Bettleheim believed that young children use these journeys into fantasy to ‘bring order’ to the chaos of their inner lives, and fairy tales ‘offer symbolic solutions to [their] difficulties’.20 However, this flight into the world of the imagination rarely leads to confusion, as Bettleheim observed, ‘after the age of approximately five – the age when fairy tales become truly meaningful – no normal child takes these stories as true to external reality’.21 In our adulthood, we maintain this ability to separate the two realms of fantasy and the real world, and although, as Richard Allen points out, cinematic spectatorship ‘involves entertaining the thought that the object perceived is before us’, at no point do we ‘believe the object is before us’ nor do we imagine that we are ‘witnessing real events’.22 Andrew Uroskie has also evoked our cognitive ability to entertain two conditions of apperception simultaneously when we watch gallery films. He describes it as a ‘double consciousness’,23 a term that recalls Kate Mondloch’s notion of ‘spectatorial doubleness’; echoing Bettleheim, she asserts that viewers are like children listening to a story and are ‘present in the real gallery space and the virtual screen space simultaneously’.24 As noted in chapter two, Richard Wollheim considered the appreciation of art to be predicated on this split recognition and in the mid-1970s, Roland Barthes advocated surrender to the dual fascinations of the filmic encounter. The initial embodied response, Barthes contended, is to become ‘lost in the proximate mirror’ of the screen and the second, to fetishise what exceeds the image, ‘the texture of the sound, the auditorium, the darkness, the undifferentiated mass of the other bodies, the projection beam, the entry and the exit from the space’.25 The cinema, suggested Barthes, has its own, built-in mechanisms of Brechtian distanciation, conditions that also apply to gallery installations. The majority of spectators remain singularly unperturbed by the knowledge that eye and brain are being deceived and what appears to be there is, in fact, absent. Perhaps the reason that a ghostly apparition strikes terror into its victim is because it manifests without any clue to its method of production; it is like a video without a screen, a film with no projector. Without any visible means of support, a spectre is like a moving image that has lost its ‘doubleness’.

In spite of the advent of digital technologies that have blurred the distinction between material and virtual zones of reality, offering us ever more opportunities to draw on what Barthes identified as the healing properties of cinematic ‘hypnosis’, we cognitively preserve the separateness of the screen world whether encountered in a gallery, cinema or online. This is especially the case when we are watching a film or video and, at the same time, making decisions about where to walk, stand or sit in a gallery-based environment. As we have seen, our senses signal vital information about our immediate environment. Guiliana Bruno emphasises the haptic sense, the ability to ‘apprehend space’ by means of touch as well as the kinaesthetic property of the organism, which allows spectators to ‘sense their own movement in space’.26 We also maintain the distinction between the two realities with the help of the screen frame, the fixed boundary that delimits the image, a demarcation line constantly hovering on the periphery of vision. The border is established by the effect of parallax as we move across the gallery space. As Robert Morris said of sculpture, the object is grasped in the relationship between ‘the known constant and the experienced variable’.27 The frame of the screen marks the difference between what moves and what remains static, what belongs to the world of things and what exists in the realm of illusion. Our levels of attention to the image vary according to individual taste – whether or not we like what we see – and are modified by the fluctuations of extra-screen distractions in the gallery space. Nevertheless, the general principle proposed by Graham Harman, that ‘we are always in contact with reality in one way or another’, in most cases would apply.28

FILM FORMS THE MIND

My instinctual humanism has insisted on asserting the critical mass that is an individual and, in spite of the indisputable allure of contemporary mainstream media, I have argued for a degree of autonomy for the spectator, in contrast to the theory of the passive spectator propounded by the structuralist regime of the 1960s and 1970s. This optimism tends to presuppose a virginal spectator, endowed with innate common sense and a moral compass, qualities that will protect her from the worst influences of screen entertainment. However, for the sake of argument, I will turn to the opposing view. Even at an early age, the human subject is socialised and interpellated by culture in general and film culture in particular. Some have argued that electronic media not only disperses attention, but it has also colonised human consciousness to such an extent that it constitutes the governing reality of quotidian life. Sean Cubitt has suggested that our cognitive immersion in simulated realities is no longer a periodic diversion from the everyday business of getting along in the world. ‘Media are the visible material of humanity,’ he has argued, ‘they are what humanity does when we are being human’.29 In recent years, the idea has gained ground that together with its later manifestations within television and online, moving image more than any other medium determines the ways in which we experience, understand and represent the world.

As early as 1916, Hugo Münsterberg argued that film mimics functional cognition, the inner workings of the mind, and he identified equivalences between, for instance, close-ups and our ability to pay attention exclusively to one aspect of the visual field; flashbacks, he said, replicate the way memory modifies our responses to the present. For Münsterberg, the ‘photoplay’ converted external reality into ‘the forms of the inner world, namely, attention, memory, imagination and emotion’.30 Eisenstein believed that montage, as a fragmentation of perceptions, was already part of our thinking processes. Paul Virilio suggested that perception itself is governed by cinema and we see reality through the prism of cinematic representation. This contention is echoed by Max Andrews, who argued that film culture permeates all aspects of our thinking and feeling, and underwrites the way we respond to life events:

Maybe our memories are made up of films and all of our expectations about love and death and how we deal with things have already been portrayed to us in films, and when these things happen to us, we can reference these things we have third-party memories of, and then behave with them.31

Contemporary commentators such as Vivian Sobchack and Kate Mondloch regard human spectators as, respectively, transformed in their sense of self by mainstream culture, and mutated from autonomous beings into ‘screen subjects’. According to Mondloch, we remain ‘largely defined by our daily interactions mediated through a range of screen-based technologies and devices’.32 The implication is that the more time we spend in front of screens, the more our experience is funnelled through the media, who digest and reconstitute the world for our daily consumption.

Others have argued that our bodies as well as our minds are inscribed by the ideologies of mainstream media imagery, themselves mirroring societal rules enshrined in language, nation and law. We have already seen how Peggy Phelan framed the body as culturally ‘marked’ by ideology, and in Snows (1967) Carolee Schneemann re-cycled projected images of the Vietnam War, which she described as entering and changing her body like a virus. More recent research by Dr. Bill Lewinski suggests that police marksmen’s reaction times are likely to be reduced because they hold their guns in the positions adopted by television cops for dramatic effect rather than take up the appropriate stance before aiming and firing. The judgement of cases in which officers mistakenly shoot innocent civilians is similarly distorted by fictional cases. As Lewinski argues, ‘everybody in our nation, including law enforcement, gets their training about police shootings from Hollywood’.33

If cinema and its contemporary manifestations can influence how we interpret and act in the world, so too does it colour the way artists manipulate established forms of expression. In 1967, Bertolt Brecht wrote of the impact of film on literature: ‘cinema spectators will now read texts in a different way, and those who write them will themselves also be spectators of cinema’.34 Writers would now include in their source material what the new technologies are capable of showing and, in the age of cinema, the creative thinking of an author becomes progressively instrumentalised, their work, increasingly cinematographic.

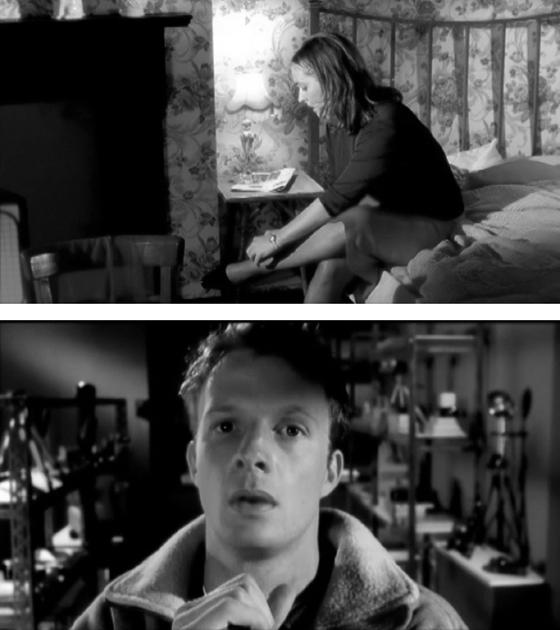

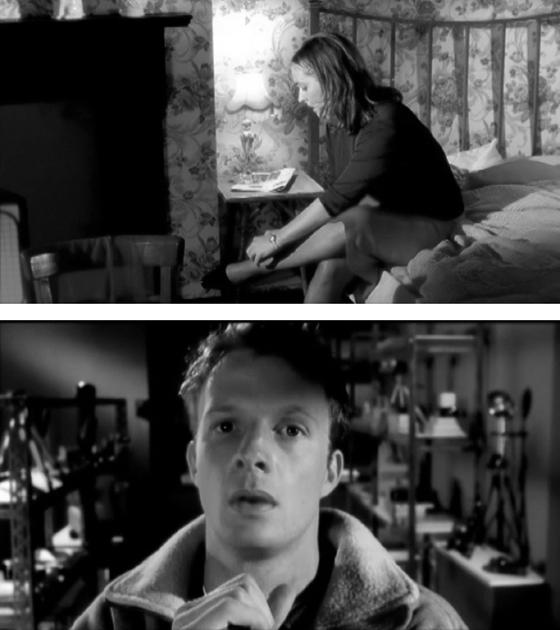

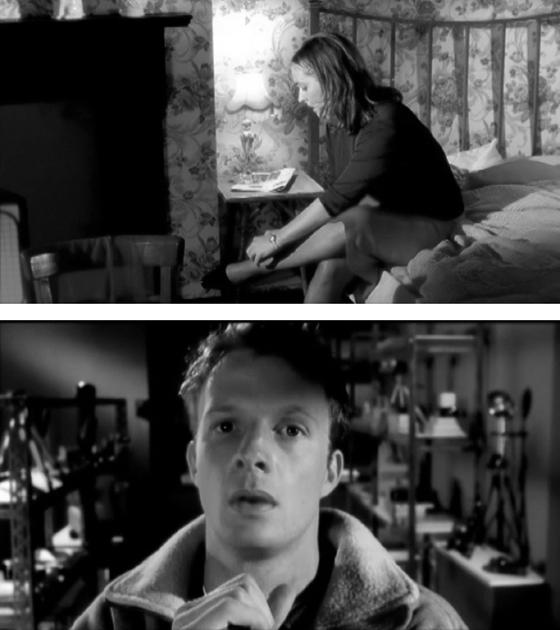

Once the structuralist prohibition on narrative and visual pleasure lifted from film and video art in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it became clear that the long arm of Hollywood had already infiltrated artists’ creative imaginations and substantially influenced the manner in which they were to formulate their work. A feeding frenzy around the canon of Hollywood film was unleashed and innumerable classics were plundered and ‘mashed up’. Mainstream television was also appropriated, and televisual ready-mades were ‘scratched’ and reconstituted as art. These tributes to the titans of television and Hollywood were transposed to the gallery space, which became what Chris Darke dubbed ‘the autopsy room’ of the movies; there, ‘artists undertook a forensic dissection of film grammar and cinema history’.35 Post-modern pastiches and remakes of Hitchcock classics became popular – Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho being the most faithful, slow-drip homage to the great man. Artists acted out the films that were most personally resonant for them. In the 1980s, Ann Magnuson created video re-runs of stock television shows, casting herself as anything from a tragic heroine to asinine children’s TV presenter. Twenty years on, Candice Breitz mobilised her own acting talents in Becoming (2003), miming the lines performed by her favourite stars of the silver screen (Diaz, Roberts and Witherspoon) alongside clips from their films including Pretty Woman (Garry Marshall, 1990) and The Sweetest Thing (Roger Kumble, 2002). Both ‘pop hackers’ negotiated the fine line between critique and narcissistic enslavement to the skin-deep attractions of television and Hollywood glamour. One of the most ingenious mainstream appropriations came in the form of Mark Lewis’s Peeping Tom (2000). The artist re-created the film within the film that Michael Powell’s murderous protagonist is shooting in the movie of the same name (1960). Lewis (who shares a name with Powell’s anti-hero) trades on the collective memories we have formed of the original film notably the thoroughly unpleasant spectacle of female victims being skewered with a spike attached to ‘Lewis’s’ camera, an image that is seared into Powell’s back catalogue. Gordon, Breitz and Lewis confirm Bill Viola’s thesis that, for artists, ‘all the movies [they] have ever seen and all the television [they] have ever watched is in there when [they] pick up that camera’.36

Mark Lewis, Peeping Tom (2000), 35mm transferred to DVD, 5:31 min. Film still courtesy and © the artist.

I will return to the Hollywood tributes of the 1990s and beyond, but for the moment, offer the provisional conclusion that notwithstanding individual variations and resistances, both producers and consumers respond to the moving image through the prism of their accumulated experience of mainstream film and television and, increasingly, the great cultural babble of the Internet. It is undeniable that the compromised and imperfect nature of our pre-formed viewing is exacerbated by the dispersion of our attention across the multiple media devices offering us global connectivity via computers, tablets, iPhones and whatever technologies the future may throw up. It takes skill and a strong mind to negotiate what Chris Darke calls ‘the image storm’ that invades our quotidian lives.37 We try to balance the real and the simulated and nurture a criticality in relation to what we see and hear so that information does not control us but serves us, personally and politically. I would argue that installation and the moving image dramatises and focuses our relationship to culture by creating a separate space of interaction, an ante-room to reality, a play room in which visitors can explore and seek new ways of participating in our increasingly fragmented, polyphonic and mediatised environment.

THE MANY FACES OF THE SPECTATOR

In this seesawing, dichotomous account of the spectator – one minute an independent-minded, discerning art devotee, and a hapless product of the mainstream the next – we should now consider the unspoken assumption that we are dealing with a universal, homogenised spectator. The oppositional practices of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s insistently validated the non-standard subjectivities of artists, paradoxically drawing on the cult of individualism associated with fine art to bolster an attack on the normalising tendencies of dominant representations. A polyphony of ‘othernesses’, was celebrated by artists who proudly declared their specificities of gender, race, age, culture and creed as well as their sexual orientation, economic status and state of health. Artists such as Keith Piper, Carolee Schneemann and Derek Jarman celebrated the athletic prowess of youth and the body beautiful while Ann Whitehurst and Stephen Dwoskin revealed the hidden lives of the disabled. If artists could embody a multiplicity of subjectivities, then moving image viewers were no less heterogeneous. Earlier theories of monocultural spectatorship dominated by fixed sets of generic responses to screen information proved untenable. Film theorists such as Jackie Stacey, Jackie Byars and Jeanne Allen were determined to displace the conventional formation of the white, middle-class, heterosexual male viewer indulging in a sadistic brand of cinematic consumption from a position of fictional mastery while Laura Mulvey’s female spectator oscillated between passively identifying with wilting heroines onscreen and adopting a dominant male gaze. Stacey and others countered these models of spectatorship with a theory of the desiring female viewer caught up in a fascination between women and consuming movies containing subtexts that she could invest with her own meanings.38 Linda Williams argued that spectators, women in particular, can ‘juggle’, that is, identify with a range of onscreen characters, both male and female.39 Meanwhile Mary Ann Doane contended that ‘female masquerade’ in its more extreme Hollywood manifestations can productively ‘defamiliarise’ representations of gender identity, thus allowing women viewers to distance themselves from the more pernicious effects of female stereotyping.40 In a more recent theory of spectatorship reminiscent of Bettleheim’s account of fairy tales, Michele Aaron advances a concept of film viewing as a form of engagement in which spectators, through a process of surrogacy, act out, presumably from a safe distance, ‘the unconscious anxieties and desires that the text provokes’.41 The therapeutic or cathartic aspects of watching frightening movies progress from voluntary submission to the image, in what Aaron describes as a masochistic, but active embrace of ‘the pleasure of unpleasure’.42 Although it seems somewhat limiting that the only form of active pleasure a woman spectator might derive from the image is a variant on masochism, the rehearsal of fears, including the fear of death itself, would appear to be a deep-seated function of our response to narration in mainstream film.43 We might reasonably suppose that the same psychic mechanisms are at work in our contemplation of more spatialised evocations of thanatos (the Freudian death drive) encountered in artists’ installations such as Bill Viola’s Nantes Triptych (1992), a work that features footage of his dying mother.

If the unsubstantiated, speculative theories of psychoanalysis applied to film fail to convince, we can turn to Stuart Hall, who in his 1980 essay ‘Encoding/Decoding’ argued persuasively against the passive model of spectatorship using a formulation derived from reception theory.44 According to Hall, there is an inevitable mismatch between the intended meaning of the producer, ‘the dominant code’ and what is ultimately decoded and understood by the spectator, a problem he identified principally in the transmission and reception of television broadcasts. Although much of what we see on the big and small screen promulgates a world view that we generally accept as a given, Hall was convinced that we can nevertheless take up an oppositional stance in relation to the social order in-representation, and ‘retotalize [its] message within some alternative frame of reference’.45 If mainstream fare is as malleable as Hall suggests then how much more open to interpretation is the ambiguous terrain of artists’ moving image installation? It was certainly not the intention that spectators should resist the underlying rhetoric of avant-garde films; indeed Gidal, Snow, Le Grice et al. hoped dissention would be directed towards the implied iniquities of Hollywood. However, a spectator’s oppositional ‘decoding’ could just as easily provide a counter-reading to the meanings intended by filmmakers such as Gidal, and in my experience, the exercise of interpretive freedom in relation to the avant-garde is rarely welcomed by its practitioners.

In order to demonstrate the polysemy of moving image culture in general and the potential range of meanings embedded in an individual installation, I shall examine a single work: Bear (1993) by Steve McQueen. Bear is a single-screen film installation featuring two naked wrestlers circling each other in a veiled allusion to the famous homoerotic fight scene in Women in Love (Ken Russell, 1969). The tense and enigmatic image of the black bodies locked in mutual posturing – half seduction, half pugilistic threat – could be read variously as a reference to colonial history, a celebration of male sexuality, a positive role model for young boys seeking sporting heroes or an object of fear in the implied violence of the performers’ movements. Black audiences in particular might draw inspiration from evidence of McQueen’s professional successes (presaging his later triumphs in mainstream film). We might also follow Richard Dyer’s lead in his 1982 article in which he recast the image of the male body as a ‘source of erotic visual pleasure for men and women’,46 an enrichment of signification that encompasses the black male bodies featured in Bear.47 The work might also provide fodder for a formal analysis of artists’ film and video, the equation of the ‘skin of the film’ with the surface of the bodies depicted. In my case, the work inspired profound admiration and, at the same time, exasperation at the spurious insistence on spectatorial mobility that leads galleries to refuse adequate seating to pensioners. As Deirdre Heddon argued, the spectator is ‘actively always engaged in narrating and translating, appropriating the story in order to make it her story’,48 and each story will be different. In the same way that siblings rarely experienced the same childhoods, spectators of moving image installations never see exactly the same work.

The meaning of a work is multiple and polymorphous and any instance of interpretation largely depends on who is doing the looking. The person engaged in active transaction with the work also brings to it her individual life history, her belief systems, political affiliations and her aspirations for the future, not to mention, as Viola reminded us, the kaleidoscope of memories of all the films, videos, television shows and installations she has ever seen. Not only are the autobiographical specificities of each spectatorial subject critical to a reading of the work, but other contextual factors come into play. The historical moment in which the work is screened will inflect its meaning; for instance, as we saw in chapter six, early works by the Cantrills in Australia, shot in the bush around Canberra were formally radical in the 1960s and 1970s but today take on additional meaning as historical records of an Aboriginal landscape now swamped by unrestricted urban expansion. A work will also be coloured by the institutional setting in which it is located – from the modest artistrun ‘alternative’ gallery to the grandest of national museums. It is marked further by the economic conditions of its production and reception as well as the critical response that gives it legitimacy or indeed, by silence in the art press that cuts short its life. All of these factors taken in aggregate lead us to conclude that the meaning of a moving image installation is multi-layered and indeterminate. Change any one of these variables and the work is potentially transformed.

Where Stuart Hall championed the agency of the spectator based on her ability to decode mainstream moving image to suit her own agenda, more recent film theory has figured the viewer continually linking and comparing the image presented to her own experiences – a kind of spectatorial reality testing. Jacques Rancière introduced the idea of the ‘emancipated spectator’ based on his observations of theatre in which, he said, the audience harnesses the ‘reasoning distance’ the live event affords, and spectators thus maintain their ability to see and think.49 If, as Rancière contends, we preserve our critical faculties in relation to a staged work, an equally ‘staged’ moving image installation also gives rise to active interpretation, and ‘interpreting the world is already a means of transforming it’.50 Rancière’s optimism was recently reiterated by Raymond Bellour for whom even the immobile, seated spectator in a movie theatre engages positively with the spectacle. In a reversal of recent trends in the study of spectatorship, Bellour has characterised physical stasis as a decided advantage because it ‘gives freedom for mental activity’51 and for the mobilisation of memory. In this respect, Bellour is echoing Socrates who, according to Plato, declared that ‘pure knowledge’ could only be achieved when the mind is ‘freed from the shackles of the body’.52 Bellour also echoes Donna Harraway who championed the cyborg as an alternative to biological determinism,53 as well as Jean-Louis Baudry, who endowed the camera with the power to create a wayfaring spectator ‘no longer fettered by a body, by the laws of matter and time’.54 If there are ‘no more assignable limits to its displacement’, then the ‘transcendental subject’ achieves a certain power in the exercise of its imagination.55

COMPLICIT AND EMPATHIC SPECTATORSHIP

With power comes responsibility and Michele Aaron raises the issue of the ‘inevitable complicity … that lies at the heart of spectatorship’, especially in relation to obscene, violent or potentially unethical material.56 Does one participate in the ongoing misery of the alcoholics Gillian Wearing invited to her studio and plied with drink, their drunken behaviour forming the material for her video installation Drunk (2000)? How does the work deflect the ‘irresponsibility or neutrality of looking on’?57 Aaron’s answer is that only works that insistently and uncomfortably foreground the spectatorship of the audience avoid the potential charge of complicity. However, in the examples Aaron provides, principally Dogme films, and indeed in Wearing’s installation, the illusionism and narrative structures of mainstream media are barely breached and, in my view, as onlookers, we remain implicated in the cruelty that has been staged for our entertainment. Spectatorial unease has certainly been achieved; however, I would argue that the only truly ethical stance would involve looking away.

In the discussion so far, we have overlooked the issue of empathy, a response that we might have expected Wearing’s cast of alcoholics to elicit. In 1873, Robert Vischer concluded that empathy necessitates a suspension of the ego in favour of the subject in view, who is recognised as similar to ourselves.58 Beyond our identification with the alcoholics in Drunk (‘there but for the grace of God go I’), another, parallel interpersonal correspondence exists between the viewer and the artist, in this case Wearing, who paid the drunks in question to appear in her work. We are likely to achieve a ‘heteropathic’ empathy with Wearing, one that acknowledges the distance between ourselves as viewers and the artist as producer.59 However, we might find our sympathies evaporate as we question the ethics of the piece, and ask, would we have done this?60 Such an interrogation might limit our feelings of empathy towards Wearing as we wrestle with the ambiguity of her potentially exploitative relationship to her subjects. We might also question her ability to feel compassion for the people whose addiction she transformed into a large-scale media spectacle, where in Julian Stallabrass’s words, we are invited to ‘holiday in other peoples’ misery’.61

A NOTE ON THE MOBILE SPECTATOR

As I have suggested, many of the critiques of experimental film and video in the 1960s and 1970s were based on the view that traditional forms of moving image involve the gradual contamination of vulnerable minds by the ideologies of the state (capitalism). This process was understood to be aided and abetted by the fixed, seated, regimented and muted positions we adopt when indulging in these dangerous forms of cinematic pleasure. Since then, a new radicality for moving image installation has been claimed based on the liberation of the viewer from the restrictions of sedentary spectatorship. Freedom of movement, it was said, would facilitate an active engagement with the work. Erika Balsom has highlighted the absurdity of ‘conflating physical stasis with regressive mystification and physical ambulation with criticality’.62 Citing Deleuze, Balsom has also argued that far from inducing in the consumer critical thoughtfulness, perpetual motion is the condition that best serves the interests of the experience economy. ‘To circulate and participate’, she observes ‘are by no means activities of resistance’ but like window-shopping, they reproduce ‘the perceptual regimes of mass culture’.63 There is also the view that mobility allows us to see installed works in ways that would elude the static spectator. In chapter two, I made a case for the potential of gallery goers to deconstruct the image by getting up close enough to read the pixels (more difficult with high definition). However, simply walking past a single- or double-screen projection – what most of us do – does not substantially change the image we see. It looks much the same from anywhere in the room. Spectators tend to pause at the ideal viewing position, equivalent to the one they would occupy in a cinema, watch awhile and then move on.64

As Le Grice pointed out, one of the disadvantages of encouraging audiences to drift through the gallery is that their commitment to the duration of a work cannot be guaranteed. The newly ‘emancipated’ spectator, browsing the work like a cultural flaneur can simply walk past if not immediately grabbed by the installation. Although the reduced attention span of the ‘media-bombed’ contemporary viewer is undoubtedly a factor, a reluctance to stay the course of a film projection is exacerbated by the lure of other elements in a multi-media work. Like the Parisian arcades and pleasure gardens that so fascinated Walter Benjamin, contemporary museum exhibitions and festivals also feature an array of attractions, what Balsom designated the ‘endless parade of objects to be consumed’.65 In the case of group shows, the next installation is always beckoning tantalisingly on the edge of peripheral vision, its sound bleeding into the audio track of the work under immediate consideration. Benjamin’s ‘distracted’ viewer, raised in a screensaver culture of constantly refreshing images, can be particularly hard to snare especially with works featuring long sequences of raw, unedited footage in which very little is happening. Chris Darke has suggested that gallery film and video, in slowing the pace, offer respite from ‘the image storm’, yet what Laurie Anderson called ‘difficult’ film often demands more patience and too great an effort of the imagination for the average contemporary spectator to draw from the work coherent meaning. As a result, cognitive dissonance, or what Peter Osborne regards as the failure of distraction, triggers feelings of anxiety in the viewer.66 Fortunately, this discomfort is quickly alleviated by turning to other works in the space, by chatting to friends, or by perusing the explanatory wall-printed notes devised by the curators – although these can be a challenge in themselves. Osborne makes a similar point when he observes that the general environment of the gallery ‘the sight of other viewers, the beguiling architecture of gallery-space, the view out of the window’, together, ‘provide the reassurance of possible distractions’.67 Should the difficulty of the work inside the gallery prove too great a challenge, we are always free to leave.

Spectatorial attention deficit has certainly been exacerbated by the oversaturation of the digital moving image in galleries and in both civic and domestic spaces. In spite of technical developments that enabled multi-screen works, large-scale, high definition projections, miniaturised LCD devices, interactive components and dazzling digital effects, the moving image has lost much of its novelty value and works can become what William Horrigan describes as ‘just another evanescent patch of light’ drifting in a sea of clones.68 According to Horrigan, video art (and, we might add the advent of video-streaming on the Internet) is responsible for desensitising visitors to media-based installations: ‘video has taught us to pass by images as nineteenth-century viewers passed by lighted shop windows’.69 The browsing gallery-goers are certainly willing to attend, particularly signature venues like the Tanks at Tate Modern, the Pompidou Centre or the Whitney Museum, but how does an artist make them stay long enough to hear and see the arguments of their work or the experiential qualities dependent on duration and attention?

STRATEGIES FOR SUSTAINING SPECTATORIAL ATTENTION

Practitioners must face the challenge of designing a work for the once-captive cinema spectator now transformed into an unpredictable, browsing and, at times, unreflective art consumer. Like Balsom, Volker Pantenburg is cautious, pointing out that neither cinema nor spatialised installations can guarantee ‘attentive perceptions’ leading to ‘reflection and a critical approach’.70 More positively, Peter Osborne regards the new forms of fractured attention played out among installations of the moving image as fertile terrain for artists, especially if they are able to create ‘new reflective rhythms of absorption and distraction’.71 Kate Mondloch has suggested that artists take full advantage of the enduring enchantments of the flickering screen, and, I would add, they do so whether historically engaged in the structural/materialist project of the 1970s or embroiled in more recent post-modern, relational or speculative realist alignments. Artists of whatever persuasion work with moving image because of its power to beguile. Where Horrigan sees ‘just another patch of light’, Mondloch emphasises the magnetic attraction of the screen, which, she says ‘insistently solicits the observer’s gaze’.72 She quotes the neurologist Christof Koch who remarks that ‘it takes wilful effort to avoid glancing at the moving images on the TV placed above the bar’.73 This argument aligns with the ‘pictorial turn’ popularised in the 1990s by W. J. T. Mitchell who evaluated images according to their intrinsic power, their enduring vitality, a force that takes possession of the spectator.74

To hold the viewer, classic cinema has relied on the charms of storytelling, the emotive power of musical soundtracks, song and dance, the glamour of movie stars, the sumptuousness of scenery and costumes, not to mention the frisson of paracinematic celebrity gossip, all of which conspire to fix people to their seats. Many artists have now resorted to the strategies that created the cinematic traditions from which they were only recently so keen to liberate the viewer. In the 1990s, Isaac Julien recreated Hollywood costume dramas with his use of period dress while Sam Taylor-Wood enlisted her celebrity friends to add their fairy dust to her work. Artists and filmmakers from Jayne Parker to Manon de Boer have worked with professional musicians and dancers, and Douglas Gordon has trained his lens on Zinedine Zidane, the world-famous footballer. Installation artists now frequently replicate the CinemaScope embrace of the wide movie screen, or cloak every wall and surface in a space with projected light so that the immersive potential of the image is fully realised. In the case of video, artists may multiply the monitors to create monumental sculptural installations along the lines of stacked-monitor works from the 1970s by Nam June Paik or David Hall. Here sculptural scale is used to mitigate the distancing effect of the bare technology; they overwhelm the spectator with video ‘writ large’, as Hall was fond of saying.

Some installation artists such as Mark Lewis and Julian Rosefeldt have deftly appropriated the emblematic techniques of commercial film, the panoramic vistas, the slow pans, the tracking shots and, in Lewis’s case, the classic transport device of back projection. Others, such as Matthew Barney in his epic Cremaster Cycle, have revamped surrealist film with Hollywood production values embellished by elaborate sets, exotic locations and fantastical costumes, what Erika Balsom has wryly described as a ‘parade of surfaces proper to a perfume advertisement’.75 Just to be certain of the impact of his work, Barney has returned the whole production to the cinema where once again seated spectators feel compelled to stay the course of the whole film. Within installed gallery works, there is a tendency to either build a cinema within the space or limit the running times of any moving image element to about ten minutes; the maximum one might expect a gallery-goer with a choice to devote to a work. Artists such as Gillian Wearing, Kutlug Ataman and Ann-Sofi Siden have embraced the long form and strayed into the territory of documentary, in the hope of capturing the viewer with the familiarity of narrative modes. Although they avoid the ‘voice of God’ narrations of expository documentaries, they embrace linear narratives and avoid pictorial ambiguity. Wearing, Ataman, Siden and Phil Collins have all adopted the format of extended, confessional interviews and in common with reality television, they mine the underside of society for their material. Spectators witness the sensational confessions of alcoholics, trans-gender performers, terrorists, exhibitionists and prostitutes, their life stories neatly packaged and contained within the minimalist chic of modern gallery spaces. Ataman and Siden pique audience interest by multiplying the viewers’ choices, offering up several subjects scattered throughout the gallery on monitors or projected onto walls – simulating the effect of the channel hopping we indulge in at home. Others have gone for the large-scale optical effect of the moving image, from Bill Viola’s incandescent projections of figures plunging, in slow motion, into water, through the computer-generated distortions of reality to pure, immersive abstractions achieved by artists such as Jordan Belson, Woody and Steina Vasulka, William Latham or Yoichiro Kawagushi. As we have seen, many artists who braved the open field of installation in the last decades, from Candice Breitz to Douglas Gordon, have plundered the archive of film as well as television history. They either sample found footage or restage moments from movie history thereby re-exploiting the appeal of the mainstream original, complete with high production values and immediately recognisable stars. Archival works flatter the movie buff in us all as they revisit the cherished ‘gestures of the master-directors’.76 However, they also tweak the material sufficiently to assert the artists’ signature and establish his/her conceptual credentials dressed in a veneer of modern-day, ‘plunderphonic’ irony.

There are those who believe that the only way to hold the viewer is to physically involve them in the resolution if not the creation of the work. We have already seen how Gary Hill incorporated laser beams in Tall Ships (1992) enabling visitors to manipulate the video projections by approaching and retreating from the screens. From these modest beginnings, ‘interactive’ works became increasingly elaborate into the new millennium. Adam Chapman and Camille Utterback’s networked Gathering (2004) allowed children to see themselves embedded in a world of drifting coloured discs, which they could shrug off or kick or punch into various configurations. Other artists have canvassed spectatorial attention by enlisting gallery-goers’ own mobile phone devices. As Balsom’s ‘perfume advertisement’ comments suggests, we have reached the point when art becomes congruent with commercials now that it shares the imperative to hail the consumer by whatever means. Computers linked via the Internet have made possible interactive works between remote locations on separate continents and it is now almost instinctive to look for the interactive, pushbutton or screen-sweep element in a gallery-based installation. In some works, the division between art and life collapses entirely and, as the curator George Fifield observed, art comes to ‘mirror the way we interact with the real world’.77 In the contemporary period, the anxiety about snaring and retaining the interest of fickle, screen-wearied audiences has indeed led to an upsurge of interactivity in gallery-based installations. It has also triggered a tendency to lapse into the promiscuous use of powerful sensory stimuli – large, loud, bright, colourful, dynamic or shocking in order to discipline responses, thus reversing the declared intentions of artists from the counter-cultural era to open up their work to a multiplicity of interpretative responses. However, ambiguities do feature in work by artists such as Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, who parody pop culture and what Lisa Akervall calls the ‘hyperactivity and narcissism’ of reality TV and social media, cultural spaces that are propelled by ‘neo-liberal networks and flows’; in performances to camera reminiscent of Ann Magneson’s television spoofs in the 1980s, Trecartin and Fitch camp up ‘hypermagnified’ identities in works such as Center Jenny (2013).78 While they offer some resistance to the commodification of the subject, argues Akervall, they cannot claim an outsider position and inadvertently reproduce naturalised modes of being (exemplified by the Kardashians) that already traffic in exaggerations of the self. The artists undoubtedly capitalise on the currency of the popularised forms they adopt and hold spectatorial attention as much through the attractions of the seductive prancing of the performers as by the critique buried in the hyperbole.

NOTES

1 Claire Bishop (2005b) Installation Art: A Critical History. London: Tate, p. 6.

2 Paul Snowdon speaking at The Curated Ego: What Makes a Good Selfie? National Portrait Gallery, 16 January 2014.

3 Antonio Damasio ([1999] 2000, 2nd edn) The Feeling of What Happens: Body, Emotion and the Making of Consciousness. London: Vintage, p. 154.

4 Susan Blackmore (2009) ‘Mysteries of the Mind’, in Walking in my Mind catalogue. London: Hayward Gallery, p. 39.

5 See Susan Blackmore (1999) The Meme Machine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

6 I am reminded of my Catholic upbringing in which I was informed by the nuns that God could read all my thoughts and foretell my future misdeeds. This baffling pronouncement left me struggling to sustain an opposing Catholic principle, that of free will; if God was all seeing, in what sense was I free to choose my actions, how could I take credit for resisting sin?

7 The leading exponents of speculative realism include Ray Brassier, Graham Harman and Quentin Meillassoux; see chapter four for a discussion of speculative realism in the context of performance art.

8 J. J. Charlesworth (2014) ‘Subjects v Objects’, Art Monthly, 374, p. 3.

10 Steven Shaviro (2011) ‘The Actual Volcano: Whitehead, Harman and the Problem of Relations’, in Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek and Graham Harman (eds) The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and Realism. Melbourne: re-press, p. 282.

11 Michael Hames-Garcia (2008) ‘How Real is Race?’, in Stacy Alaimo and Susan Hekman (eds) Material Feminisms. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, p. 327. For an overview of the materialist ‘turn’ see Iris Van der Tuin (2011) ‘New Feminist Materialisms – Review Essay’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 34: 4, pp. 271–7.

13 Malcolm Le Grice (2001) ‘Improvising time and image’, Filmwaves, 14: 1, pp. 14–19.

14 Peter Osborne (2004) ‘ Distracted Reception: Time, Art and Technology’, Time Zones catalogue. London: Tate, p. 73.

15 Siegfried Kracauer ([1926] 1995) ‘The Cult of Distraction: On Berlin’s Picture Palaces’, in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, trans. Thomas Y. Leving. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 326.

16 Tom Gunning ([1989] 1994) ‘An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator’, in Linda Williams (ed.) Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, p. 126.

18 Jean Mitry (1965) Esthétique et psychologie du cinéma. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, p. 179.

19 See D. W. Winnicott ([1971] 1980, 2nd edn) Playing and Reality. Middlesex: Penguin.

20 Bruno Bettleheim (1978) The Uses of Enchantment. London: Peregrine, p.53.

22 Richard Allen (1997) Projecting Illusion: Film Spectatorship and the Impression of Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 100.

23 See Andrew V. Uroskie (2008) ‘Siting Cinema’ in Tanya Leighton (ed.) Art and the Moving Image. London: Tate/Afterall, pp. 386–400. The term ‘double consciousness’ has another application beginning in the writings of W. E. B Dubois in the 1900s where it refers to the black experience of harbouring both a self-determined identity and one that is filtered through a white perspective of ethnic races.

24 Kate Mondloch (2010) Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, p. xx.

25 Roland Barthes (1976) ‘En sortant du cinéma’, Communications, 23:1, p. 106 (my translation).

28 Graham Harman quoted by Steven Shaviro (2011), op. cit., p. 280.

29 Sean Cubitt in an e-mail to the MIRAJ editorial team, 13 July 2010. It is outside the scope of the present volume to pursue a deeper analysis of the effects of television, the Internet and other communication devices on children and adults. Social scientists have observed behavioural changes among children, a reduced tolerance to delayed gratification, decreased family and peer group interaction and civic participation, and an increase of obesity in adults, all of which they attribute to higher levels of exposure to screen-based material. A useful summary of current research can be found in K. Subrahmanyam et al. (2001) ‘The impact of computer use on children’s and adolescents’ development’, Applied Developmental Psychology, 22, pp. 7–30.

30 Hugo Münsterberg ([1916] 2004) ‘Defining the Photoplay’, in Thomas E. Wartenberg and Angela Curran (eds) The Philosophy of Film: Introductory Texts and Readings. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, p. 44.

31 Max Andrews (2006) in conversation with Jordan Wolfson, ‘How does the perfect human fall? Like this’, Uovo, 2, p.184.

32 Kate Mondloch (2010), op. cit., p. 19. See also Vivian Sobchack (1998) ‘The Scene of the Screen: Envisioning Cinematic and Electronic “Presence”’, in Materialities of Communication (Writing Science) (1994), Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht and K. Ludwig Pfeiffer (eds). Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 83–106.

33 Bill Lewinski speaking on Panorama (2006) BBC1. 15 October.

34 Bertolt Brecht (1967) Sur le Cinéma. Paris: L’Arche, p. 165 (my translation).

35 Chris Darke (2000) Light Readings: Film Criticism and Screen Arts. London: Wallflower Press, p. 163.

36 Bill Viola quoted in Chris Darke, ibid., p. 187.

38 See E. Deidre Pribram (ed.) (1988) Female Spectators: Looking at Film and Television. London: Verso.

39 See Linda Williams (1984) ‘“Something Else besides a Mother”: “Stella Dallas” and the Maternal Melodrama’, Cinema Journal, 24: 1, pp. 2–27; ‘For rather than adopting either the distance and mastery of the masculine voyeur or the over-identification of Doane’s woman … the female spectator is in a constant state of juggling all positions at once’, p. 19.

40 See Mary Ann Doane ([1982] 1999) ‘Film and Masquerade: Theorising the Female Spectator’, in Sue Thornham (ed.) Feminist Film Theory: A Reader. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 131–56.

41 Michele Aaron (2007), op cit., p. 3.

43 Aaron acknowledges a potential drawback to her theory of masochism for women when she quotes Linda Williams: ‘the recovery of masochism as a form of pleasure does not bode well for a feminist perspective whose political point of departure is the relative powerlessness of women’, ibid., pp. 79-80.

44 Stuart Hall ([1980] 2001) ‘Encoding/decoding’, in Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner (eds) Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks. New York: Wiley, pp. 166–76.

46 See Richard Dyer (1982) ‘Don’t Look Now’, Screen, 23: 3/4, pp. 61–73.

47 The athletic, black body has other, post-colonial implications that are less positive, with echoes of the ‘noble savage’ resonating in the elevation of the African sports competitor to star status whilst disavowing continued racial discrimination in society at large.

48 Deirdre Heddon (2012) ‘The Politics of Live Art’, in Deirdre Heddon and Jennie Klein (eds) Histories and Practices of Live Art. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 191.

49 Jacques Rancière (2009) The Emancipated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliott. London: Verso, p. 5.

51 Raymond Bellour in conversation with Eulalia Valldosera, July 2012, Caroll/Fletcher Gallery, London.

52 Plato, The Last Days of Socrates (1954), trans. Hugh Tredennick. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, p. 112.

53 See Donna Harraway (1991) ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century’, in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, pp. 149–81.

54 Jean-Louis Baudry ([1971] 2009) ‘Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus’, in Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (eds) Film Theory and Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 360.

56 Michele Aaron (2007), op. cit., p. 98.

58 See Robert Vischer ([1873] 1994) ‘On the Optical Sense of Form: A Contribution to Aesthetics’, in H. F. Mallgrave and E. Ikonomou (eds) Empathy, Form and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics 1873–1893. Santa Monica, CA: Getty Center for the History of Arts and the Humanities, pp. 89–123.

59 See Kaja Silverman (1996) The Threshold of the Visible World. New York: Routledge. Silverman draws a distinction between idiopathic empathy, one that is based on the incorporation of the other into the self, and heteropathic, which preserves and respects difference.

60 I asked myself these same questions in relation to videos I made with my son Bruno in the early 1980s when he was a small boy and unable to protest. In retrospect, I find these works if not indefensible, then certainly ethically ambiguous.

61 Julian Stallabrass (1999) High Art Lite: British Art in the 1990s. London: Verso, p. 256.

62 Erika Balsom (2013) Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 53.

64 Of course, there are interactive works fitted with motion sensors that will indeed change the image as the viewer walks past, but these are the exception rather than the rule.

65 Erika Balsom (2013), op. cit., p. 53.

66 See Peter Osborne (2004), op. cit., 66–75.

68 William Horrigan speaking at the Moving Image as Art: Time Based Media in the Art Gallery conference, Tate Britain and Tate Modern, London, June 2001.

70 Volker Pantenburg (2014) ‘Migrational aesthetics: On experience in the cinema and the museum’, MIRAJ, 3: 1, pp. 25–35.

71 Peter Osborne (2004), op.cit., p. 73.

72 Kate Mondloch (2010), op.cit., p.21.

73 Christof Koch quoted by Kate Mondloch, ibid., p. 161.

74 See W. J. T. Mitchell (2005) What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. For a recent survey of the new theories of pictorial and object autonomy see Francis Fascina (2014) ‘Object/Self’, Art Monthly, 375, pp. 5–8.

75 Erika Balsom (2013), op. cit., p. 55.

76 Chris Darke (2000), op.cit., p. 164.

78 Lisa Akervall speaking on ‘Videoart’s inverted panopticon: a critical aesthetics of postcinematic subjectivity’ at the Screen conference, Glasgow, June 2014.