L’illusion est le premier plaisir.

‘La Pucelle d’Orléans’, Voltaire, 1762

NATURALISM: THE ENCHANTMENTS OF THE SCREEN

Michael O’Pray described the cinematic outpourings of avant-garde artists in the 1960s and 1970s as a ‘promiscuous activity, taking many forms and showing in a range of contexts’, including clubs, cinemas, artist-run venues, cable TV and galleries.1 At different times, the work was labelled experimental film, avant-garde film, structural/materialist film or, in the USA in particular, underground film, a term O’Pray favours because of ‘its implication for an art that comes from below, from beneath the accepted culture as opposed to leading from in front’.2 Many practitioners did indeed believe that they were the as-yet-unrecognised radical vanguard of a new age of creative if not political efflorescence and it was in this period that film came into its own as an autonomous art practice. An elaborate scholarly armature was developed to investigate the material, procedural, industrial, psychoanalytic, phenomenological, political and ontological specificities of the medium, encompassing moving image in both popular culture and art. In the pages of a bevy of film theory and art magazines,3 avant-garde film became so heavily academicised that watching films was now understood to be what A. L. Rees called ‘an act of reading’4 rather than the opportunity to go on a journey of ‘visual emotion’ as Virginia Woolf suggested, where we could ‘open our minds wide to beauty’.5

A detailed discussion of the fine distinctions between the different factions of experimental film or indeed the intricacies of Peter Wollen’s ‘Two Avant-Gardes’6 is beyond the scope of the present volume – Rees, O’Pray, David Curtis and Malcolm Le Grice are reliable sources in this respect.7 Instead, I shall concentrate on tendencies that carried over into expanded cinema and installation, primarily work that was concerned with the physical presence of the filmic apparatus and artists who undertook the deconstruction of cinematic codes driven by broadly leftist and feminist political convictions. We begin our tour of avant-garde film by revisiting the staging of mainstream, illusionist cinema, and proceed to consider its disassembly by syntactical critique and material interference in the work of avant-garde filmmakers.

In the previous chapter, we considered Tom Gunning’s argument that the pioneering filmmakers of the nineteenth century, far from wishing to trick the eye and brain of their audiences, maintained ‘a conscious focus on the fact that [their films] were only illusions’.8 The gasps of early cinema audiences, said Gunning, were as much for the ingenuity of the technology as for the ‘visual trauma’ of believing in phantasmagorical apparitions. The apparatus of film formed an integral part of the spectacle. However, the development of Hollywood narrative meant that cinematic verisimilitude gradually took precedence over the self-referential showmanship that was so much in evidence at the dawn of cinema. Lights were dimmed, the projector disappeared into its hermetically sealed booth, speakers were embedded into walls and cinema seats were upholstered in velvet to absorb the sound of sweet wrappers and shenanigans in the back row. In a parallel development in theatre, the mayhem of early audience participation in pubs, fairs and music halls gave way to what Ross Brown called ‘the dramaturgical mode of audition’, one that required the increasing separation of spectacle and audience.9 The design of theatres, concert halls and early picture palaces gradually perfected the muting of the audience, the silencing of their bodily presence and the narrowing of attention to what was taking place onstage or on the big screen.

Once fixated on the cavalcade of images parading in the dark, the suspension of disbelief came into play. As we saw in the last chapter, this allowed viewers to enter into the imaginative space of a movie where they became schooled in the syntax of cinema based on narrative, continuity and realism. Cinematic mimesis is itself dependent on the structuring framework of perspective, a Euclidian spatial logic in which movement, parallax and scale enable the perception of depth while viewing distances are calibrated to the functional range of the human eye and ear. As I proposed in chapter five, once acquired, film-reading skills become the unconscious organising principle of spectatorship. In the late 1960s, Christian Metz inaugurated a systematic study of film syntax based on Saussurean linguistics in which the film is understood as a semiotic text deriving its meaning from its differential position within a network of texts.10 Where Metz studied the structures of cinematic signification, Giuliana Bruno elaborated her concept of movies as ‘atlases of emotion’, cartographic journeys that transport us through the sentimental landscape of humanity.11 Mieke Bal similarly refocused on the impact of cinematic content arguing that the key attribute of the figurative image is its capacity to move the spectator.12 Many experimental filmmakers rejected figuration adopting instead varying degrees of abstraction; however, a significant number retained mimetic representations of reality including filmic portraits of individuals. Cognitive science tells us that the human form, when reproduced photographically and set in motion on a screen, has a unique ability to capture spectatorial attention. The empirical research of Uri Hasson or Tim Smith confirms that within the field of vision, the human brain prioritises people in general and the human face in particular while peripheral vision is primed to register movement.13 As social beings, the ability to recognise human manifestations in space is critical to survival. Stephen Heath in his 1976 essay Narrative Space proposed that the viewer has a further need: to occupy a secure position in relation to perspectival space, one that is threatened by the constant motion of filmic images. Christian Metz identified another level of spectatorial anxiety around the possibility that the illusion at any moment might break down.14 Heath describes how a reassuringly coherent sense of space is achieved by the logic of narrative into which the spectator is ‘sutured’. The entire filmic experience is bookended by the establishing and closing vues, the static wide shots of the terrain across which the drama unfolded and came to a conclusion, ‘the final word of its reality’.15 Following Heath, Tim O’Riley has noted that mainstream cinema creates a ‘desire for a unified perception of both space and narrative’.16 This need for pictorial and diegetic coherence generates an appetite to discover what happens next and motivates the spectator to make sense of the succession of partial views in precarious motion that constitute the average movie or television drama, a reading of cinematic code that, for us, has become second nature.

It was the remarkable willingness of spectators to suspend the here and now and allow themselves to be transported into another world that formed the focus of the avant-garde critique of narrative cinema in the counter-cultural maelstrom of the 1960s and 1970s. According to the rhetoric of the age, ‘passive spectatorship’ made cinemagoers vulnerable to the ideological messages smuggled into pleasurable escapism, into what most of us would regard as harmless entertainment. These messages were programmed to reinforce the prevailing structures of the ‘social order’, promoting ways of seeing the world that tended to naturalise the power and influence of those in control whilst justifying the subjugation of the majority of the population. In the age of protest, mainstream television and cinema were accused of insidiously perpetuating inequality by means of subliminal indoctrination. However, this critique is not restricted to the 1960s and 1970s; since then, throughout the postmodern period, commentators and artists have continued to express concern about the deleterious effects of exposure to cinematic entertainment. In the 1990s, Luke Gibbons, writing about the propagation of negative Irish stereotypes in popular culture, asserted that ‘media representations … act as transformative forces in society, rather than as “reflections” or mimetic forms at one remove from reality’.17 The innocence of the image is not to be reinstated and Gibbons emphasised its continuing power to mould the individual. Into the millennium, in our increasingly mediatised environment, Slavoj Žižek has warned of the pernicious invisibility of covert political indoctrination: ‘we live in times where ideology is very strong, to the extent that it isn’t even experienced as ideology’.18 The normalisation of the neo-liberal/conservative agenda means that its notions of nationhood, progress, growth, ‘us’ and ‘them’ are so well assimilated that voices of dissent struggle to make an impact. The concept of the spectator ‘dumbly sit[ting] in awe’ of idealised societal exemplars, wherever they are accessed – billboards, television, cinema, newspapers, magazines, in print or online – underscores contemporary investigations of spectatorship, implicitly or explicitly.19 The new cultural stereotypes (not so different from the old) themselves modulate artists’ creative responses to the ideologically inflected representational field in which we all struggle to build a viable identity.

PSYCHOANALYSIS AND FEMINISM

In the 1960s and 1970s, artists and academics struggled to understand the process of cathexis, the emotional investment in on-screen entities. Why, they asked, do we desire to enter the action ‘as if it mattered to us’?20 Christian Metz believed that our appetite for pleasurable identification with aspirational cinematic scenarios is driven by a psychic formation laid down in Jacques Lacan’s ‘mirror phase’, a developmental milestone triggered by the infant’s first encounter with her own image in a mirror. The child perceives her reflection, her self-in-representation as a coherent, integrated being, an idealised image split off from her subjective experience, which is itself fragmented and dispersed, mired in the chaotic emotions and bodily sensations of infancy.21 The mirror phase heralds the child’s evolving sense of herself as a social being, out there in the world, a product of the ‘social order’ and its regimes of representation. According to Metz, the cinema spectator indulges in a pleasurable re-visiting of the idealised and imaginary identity now reincarnated in the elegant beings animating the cinema screen.

The psychoanalytic model of spectatorship seeks to explain how the replaying of the mirror phase, and the embrace of the imaginary might function in cinema. Metz argues that the cinema stages our own desire, and this becomes translated into a desire to both possess and embody the reified models of humanity in the starry firmament of Hollywood. According to the psychoanalytical paradigm, the projection and identification is achieved by means of narrative immersion undergird by narcissistic fantasies of omnipotence. Protected by the dark auditorium and enveloped in their ‘cloaks of invisibility’, spectators can retreat into the scopophilic delights of observing the desired object unseen, just as the Elders spied on the beautiful Susanna from behind conveniently-placed biblical bushes. As Virginia Woolf observed, we ‘behold’ onscreen performers ‘as they are when we are not there’ and taking up the privileged position of the all-powerful gaze, cinema-going audiences can fetishistically consume images of the stars who, like Susanna, appeared to be unaware of being observed.22 The point about desire, of course, is that it can never be satisfied. As Count Vronsky discovered, once in possession of the enchanting Anna Karenin, her conquest ‘brought him no more than a grain of sand out of the mountain of bliss he had expected’.23 The realisation then dawns that he has been guilty of the ‘eternal error men make in imagining that happiness consists in the realisation of their desires’.24 Cinema materialises and regulates the eternal circulation of desire and as we have seen, audiences, luxuriating in its voyeuristic delights, can become so hypnotised by the onscreen world that they remain oblivious to the ‘transformative forces’ Gibbons and Žižek claim are still operating within media representations. It is these forces, subtly applied to the human psyche that film theorists in the 1970s identified as capable of modulating individuals’ perceptions of the society to which they belong, locking down their position within it and influencing their life choices.

The feminist critique of spectatorship differentiated between the male and female spectator, and nominated both the eye of the camera and the eye of the beholder as constitutionally phallocentric, predominantly organised around the erotic desires of men. In her celebrated essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975), Laura Mulvey argued that the female spectator was condemned to oscillate between two modes of spectatorship. She could either passively identify with an objectified, sexualised heroine onscreen (a character condemned to be ‘the bearer of meaning, not the maker of meaning’), or actively associate with the scopophilic gaze of the male protagonists and by extension that of the male members of the audience, her co-occupants of the auditorium.25 Mulvey went on to show the predicament of the woman spectator who co-opts the agency of the active male hero but gains her position of spectatorial mastery only by abdicating her given gender. Although Mulvey among others has since revised her initial theory of female spectatorship, it served to highlight the crucial role of identification with cultural icons in the socialisation of girls, an instrumental educational force that remains with us today.26 As I have suggested, the process of evolving as a social being is structured around the search for a viable place in the world, one that the individual might productively occupy. No less today than in the 1960s, media images, by virtue of their ubiquity, continue to influence our ideas about who we think we are, what we aspire to become and how we experience our lives from a gendered, ethnic and age-defined standpoint. It may seem tiresome to labour this point but in 2008 the then culture minister Barbara Follett made a chilling observation: ‘If you ask little girls, they either want to be footballers’ wives or win The X Factor.’ Follett concluded that ‘our society is in danger of being Barbie-dolled’.27 Natasha Walter has shown how a new brand of biological determinism is masking cultural reinforcement and rationalising girls’ apparent preference for all things pink as ‘an inescapable result of biology, which is assumed to be resistant to change’.28 The equally worrying findings of an Ofsted report in 2011 highlight the continuing lack of ambition among girls beyond the traditionally proscribed roles for women in Western society.29

With repeated exposure to narratives supporting this view, whether consciously or not, women may feel that without the positive charge of youth and sexual desirability, their social value is considerably diminished. Angela McRobbie has observed that in the so-called ‘post-feminist’ age, women have been sold a spurious notion of empowerment and freedom of choice that, in fact, is geared to commodity consumption and reinstates the rule of individualism, thus inhibiting collective political initiatives.30 Not only that, but with the abandonment of ‘we’ in favour of ‘I’, feminism has been ‘disarticulated’, severed from its natural allies in the trade union movement and among anti-racist and gay activists.31 Despite the legislative reforms that have instituted (in principle) equal opportunities for women, LGBT and ethnic minorities in Western societies, mainstream moving image frequently operates as an opposing, reactionary force. It insinuates its neo-liberal, retrogressive ideological messages into the tender ambitions of the young and the continuing expectations of the old, into the hopes of the marginalised and the dreams of the displaced.

INDEXICALITY

It is possible to argue that the persuasive power of the moving image has been overstated both by the experimental film generation to which I belong and indeed by current commentators, and I shall indeed pursue that line in due course. However, the illusionism of film derives its plausibility partly from the presupposition of indexicality, a concept formulated by the philosopher C. S. Peirce in his 1902 essay Three Trichotomies of Signs.32 ‘An Index is a sign,’ declared Peirce, ‘which refers to the Object that it denotes by virtue of being really affected by that Object’.33 The footprint is most commonly cited as an analogue of the indexicality of film – changing patterns of light imprint themselves on the photosensitive material of the filmstrip in the same way that a foot bearing the weight of a body makes its mark in fresh snow. The new impression takes the shape of the foot that created it and thus becomes a sign for the absent body while the host material is physically transformed in the encounter, whether snow or celluloid. Peirce’s notion of indexicality was elaborated by Peter Wollen who, in Signs and Meaning in the Cinema (1972), drew a distinction between the iconic and the indexical, elegantly summarised by Ian Christie as follows: ‘iconic because film images resemble those things which they signify; and indexical because their manner of production – cinematography – produces Peirce’s “genuine relation” between sign and “object”.’34 This direct causal relationship came to be celebrated by experimental filmmakers as a specific characteristic of film residing, as Nicky Hamlyn observed, in its ability to generate ‘traces that evidence a certain situation existed in the room where the event took place’, an event that was witnessed by a camera.35

The systemic indexicality of film therefore carries with it an assumption of documentary authenticity, a corollary to the ‘essentially objective character’ of photography on which André Bazin based his ‘mummification’ theory. The photographic image, both still and moving, he contended, enables ‘a man’ to ‘preserve, artificially, his bodily appearance’ and thus provide ‘a defence against the passage of time’, a means to cheat death through representation.36 Richard Allen has argued that films, like photographs ‘carry a presumption of truth for the viewer that rests upon the causal relationship between object and image’.37 Like Bazin, Allen concluded that the analogical model of the photographic image has carried over into film where any footage, documentary or fictional is interpreted by an audience as ‘actuality footage’, and in its near-perfect mimicry of the real world acquires ‘evidentiary status’.38 Allen goes on to propose that although we are not ‘naive’, that is, we do not mistake a fiction film for reality, we nonetheless ‘believe that what we see is actuality unless there is reasonable evidence to the contrary’. In whatever form it takes, ‘reproductive illusion trades upon this belief’.39 The facticity of film has acquired an archival gloss in contemporary re-appraisals of mainstream films. Catherine Russell has identified a radical ‘untimeliness’ to the cities and landscapes that appear in the backgrounds of mainstream films.40 They stand as an historical document, an indexical trace of the locations against which the action was set. This is also true of artists’ films. For instance, the films shot by Arthur and Corinne Cantrill around Canberra, Australia, in the 1970s remain a potent ‘mummified’ record of a landscape once integral to Aboriginal culture, now blighted by Western settlement and development.41

In spite of the sophistication of today’s cinema audiences, including the international community of film historians who are finding new meaning in the backgrounds of canonical films, we still occasionally witness the phenomenon of delusional stalker fans who cannot differentiate between fiction and reality. In their frenzied pursuit of stars, they believe they are worshiping the character not the actor.42 If this sounds like an extreme and exceptional example of media introjection, akin to Freud’s ‘psychosis’ of dreams, we do not need to look very far for evidence of the power that media representation continues to exert on the psyches of the citizenry. I have already suggested that girls restrict their ambitions in line with the role models they are exposed to in film, television and on the Internet, but I shall end with the testimony of the British soldier Anthony Swofford. In 2003, he admitted to a Guardian reporter that in the run up to the first Gulf conflict, he and his fellow marines watched jingoistic war films ‘and were excited by them, because they celebrated the terrible and despicable beauty of our fighting skills’.43 The aestheticisation and normalisation of violence is another product of media representation, as is institutionalised racism and the creeping influence of religion in secular life, including education.44 It would be unwise to dismiss the critiques of representation developed in the 1960s and 1970s. The power of mainstream cultural representations remains undiminished and the impact of film has been amplified by the digital age; its tentacles reach every corner of our lives as we fill our homes with ever-wider-screened receivers and voluntarily carry around with us miniaturised ‘influence machines’.45

STRATEGIES OF DECONSTRUCTION: ANTI−NARRATIVE

In common with their contemporaries in the fields of social science, literary criticism and political philosophy, artists working within the zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s began to question Western society’s ‘rigid cultural conventions’.46 In the wider international, postcolonial context, radical practitioners interrogated Western powers’ belligerent foreign policies, past and present, as well as their ‘misguided public posturing’.47 Closer to home, oppositional thinkers exposed entrenched social inequalities legitimised by essentialism – the appeal to universal truths based on binary oppositions of black vs. white, female vs. male, heterosexual vs. ‘deviant’, primitive vs. civilised, nature vs. culture. The avant-garde as it evolved into the 1970s and 1980s embraced Jacques Derrida’s critique of the unified subject, and aspired to an identity that was fluid, provisional, fragmented and impure. Film and videomakers sought to mitigate the negative impact of surreptitious indoctrination encoded in cinematic and televisual content. Their aim was to transform spectators from docile consumers of dominant ideology into what Michele Aaron called ‘intrinsically politicised subject(s)’.48 If ideological messages work their nefarious magic by means of visual pleasure and narcissistic identification with defined characters populating a fictional scenario, then the first step was to intervene in the structures of cinematic representation. The imperative was to disrupt the viewer’s habitual responses and inhibit what Nicky Hamlyn called ‘their gestalt-forming efforts’, that is, their ability to create satisfactory, coherent narratives out of a succession of disparate onscreen events.49 Filmmakers such as Laura Mulvey were determined to emancipate the spectator and adopted measures to ensure the ‘destruction of pleasure as a radical weapon’.50 The deconstructive programme thus began by jettisoning conventional narrative, linear storytelling and any dramaturgical entertainment that involved actors, dancers, singers, costumes, music, exotic locations and elaborate sets. Although filmmakers such as Mulvey herself, as well as videomakers including Stuart Marshall, adapted narrative and documentary codes, they devised strategies to subvert them, in the case of Marshall by using stilted, amateurish acting, and Mulvey by means of extended 360˚ shots. As we shall see, in the more extreme cases of cinematic deconstruction, the fracturing of language advocated by Derrida resulted in the virtual destruction of filmic illusionism and the denial of the fetishistic pleasures of voyeurism.

CASTRATING THE GAZE

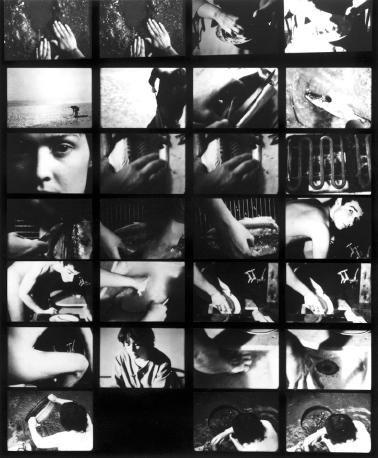

Peter Gidal decreed that in avant-garde film ‘the shape of the material’ should be ‘primary to any representational content’, and this precept became the governing principle of much British work.51 A number of formal and analytical strategies were adopted to achieve this aim, on the one hand deconstructing the language of mainstream film and, on the other, making physical interventions into the filmic apparatus. In the following sections, I shall outline some of these approaches, both semiotic and materialist, collectively intended to reveal and undermine the smooth workings of illusionism in narrative film as well as disrupt conventional modes of spectatorship. Feminist filmmakers such as Laura Mulvey, Sally Potter and Joyce Wieland adopted a simple technique for ‘castrating the gaze’ in which the woman onscreen, the actress or, in Weiland’s case, her feline alter ego, breaks the cardinal rule of narrative cinema and looks directly into the lens of the camera. The theory was that when a woman returns the gaze of the camera and the (male) spectator beyond, she blows their cover, voyeurism is exposed and the filmgoer is denied the pleasures of consuming the female body from a position of spectatorial privilege. Jayne Parker’s I Dish (1982) is a case in point. The female protagonist, engaged in the preparation of a fish for the table, regularly turns her gaze back to the viewer, the ‘I’ of her eye, registering her awareness of the apparatus of film and of the audience watching, and at the same time, asserting her own gendered subjectivity.

Jayne Parker, I Dish (1982), 16mm, b/w, 16 min. Courtesy of the artist and LUX.

The radical films of the feminist deconstructive school were, at times, bewildering to contemporary audiences. In Light Reading (1978), Lis Rhodes refused all but the most oblique representations of a woman’s body on the grounds that it could not escape erotic retrieval even if the performer’s gaze was locked onto the eye of the beholder. Peggy Phelan condemned the display of the ideologically ‘marked’ body of woman in art, because it could be used to ‘“prove” that sexual difference is a real difference’.52 Rhodes avoided offering up her body to the camera and instead asserted her subjectivity through her voice and in the skills she deployed to create an editing regime of complex layering, fragmentation and repetition. The film opens with an elegiac monologue in which the artist is heard musing on her entrapment in language, followed by a declaration of her modus operandi. ‘I am placed in darkness only to be apparent, to appear without image’, she intones, the words spoken over an uncompromisingly uniform black screen marking her presence as a creative agent and her absence as image.53 Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s Riddles of the Sphinx (1977), the slow, subjective record of a day in the life of an average housewife, and Colette Lafont’s extended bouts of convulsive laughter in Sally Potter’s Thriller (1979) both confounded all expectations of entertaining screen time. In the 1970s, such subversive films often found themselves at the centre of factional conflicts. Marxist and feminist film- and videomakers believed the struggle should be conducted at the level of cinematic language while the campaigning wings of socialism and feminism, which Peter Wollen judged to be ‘aesthetically conservative’, found it politically expedient to adopt didactic documentary modes of communication.54 Experimental work was frequently dismissed for being obscure and elitist and out of touch with the struggles of ordinary, working-class men and women.55 However, the groundbreaking films of Mulvey, Rhodes, Potter and Parker, along with their male counterparts in experimental film were, in many cases, moving evocations of subjectivities in transition, and with imaginatively adapted narrative forms and richly textured visual landscapes, they were, in fact, comparatively accessible works. They inspired only a small fraction of the incomprehension (my own included) that met the advent of structural/materialist film.

STRUCTURAL/MATERIALISM

Peter Gidal first aired his radical doctrine of film in his 1975 essay ‘Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film’.56 Any recourse to the conventional language of mainstream film would run the risk of creating ‘meanings which are then posited as natural, as inherent’.57 Such lapses Gidal condemned as a return to the exercise of what he called ‘processes of power-enactment’.58 To counter the inequities embedded in dominant filmic language, Gidal launched a programme of self-reflexive filmmaking located in the London Film-Makers’ Co-op in the late 1960s and early 1970s. A group of artists including Malcolm Le Grice, Nicky Hamlyn, Lis Rhodes, Annabel Nicolson, William Raban and Gill Eatherley produced a body of work designed to render visible the workings of the apparatus of film, largely by means of sabotage. All the rules of cinematic grammar were broken: narrative logic imploded, continuity disrupted, and edits made visible by substituting smooth dissolves with disconnected jump cuts. The synchronisation of image and sound was uncoupled and the audio track disintegrated into a cacophony of voices, screeching instruments and electronic noise or, in homage to early film, remained utterly silent. Actors stepped out of their roles or spoke gibberish, sets were revealed as fake, camera operators were no longer anonymous – unstable, out-of-focus, and handheld footage betrayed their mediating presence. Directors shouted incoherent instructions from out of frame, lighting went haywire with studio lights or the sun regularly blinding the lens, or the auditorium was suddenly plunged into darkness as the lights were inexplicably extinguished. Abstruse messages flashed on the screen in a parody of intertitles, found footage was mangled and regurgitated into a visual gallimaufry accompanied by a mélange of incidental sound. The conventional roles of the film set were overturned as the filmmaker regularly doubled as performer, camera operator, editor, projectionist and distributor and, after hours, became a philosophical apologist for avant-garde film in learned journals such as Screen and Undercut in the UK, the Cantrill Filmnotes in Australia and Millennium Film Journal in the USA.

In addition to witnessing the deconstruction of established film grammar, and the unmasking what were regarded as the deceptions perpetrated by cinematic illusionism, spectatorial attention was redirected towards the means of production, the gadgetry as well as the physical and chemical substrate of film, all of these material attributes being previously concealed. Experimental artists now brought to the fore the creative processes of pre- and post-production as well as the final stages of filmmaking embodied in the paraphernalia of the cinema: the projector, filmstrip and the light beam that together with the mechanical transport of the film at 24 frames per second, generate a moving image. ‘What is at stake’ wrote Philip Drummond, ‘is not merely the “deconstruction” of film narrative, but rather the entire internal dialectic of film construction’.59 Finally, practitioners such as Le Grice, Rhodes and Eatherley in the UK, Michael Snow in Canada, Peter Weibel in Germany and Ken Jacobs in the USA, brought into the equation the idea of film as a time-based projection event encompassing the technology, the space – both social and physical – and, in concert with the project of expanded cinema and installation art beyond it, the experience of spectators.

With the curtain ripped away from the tricks of mainstream narrative film both intrinsically within the diegetic space of the film and extrinsically in its visible technical supports, the illusionism of cinema was shaken to its core and in the aftershocks, the suspension of disbelief struggled to maintain its hold on the viewer. Through repetition, abstraction and fragmentation, the cinematic sign was cleaved from its referent and in a free play of signifiers, the transparency of film, its ability to veil itself in mimesis of reality, was negated.

Robert Hughes, writing in the late 1970s, attempted to define the principles steering avant-garde visual strategies. Artists, said Hughes, nurtured the belief that ‘by changing the language of art, you affect the modes of thought, you change life’.60 It was this creed that drove Gidal’s somewhat utopian determination to reeducate the spectator by means of denial, in accordance with a strict ‘theology of negation’.61 If you withhold the delights of narrative immersion in the ‘dream screen’, so the theory went, and instead expose your audience to a film-as-film, one ‘that does not represent or document anything’,62 they will come to realise the degree to which mainstream film manipulates their responses for the benefit of those in power. In addition, once liberated from ‘mindless’ absorption in narrative entertainment, the viewer would become productively aware of her own perceptual processes, the cognitive mechanisms of film spectatorship that are mobilised in realist cinema, and that she has learned like a conditioned reflex. This new sensitivity to the spectatorial experience was the focus and key to many of the films of the period. The final objective was to develop in the spectator the ability to recognise and refute the politically-motivated messages lurking in mass media, and, by extension, the more direct, official utterances of the ruling elite. Once wise to the machinations of power, the decision to become politically active within the counter-culture was but one short step away. I will return to Gidal’s theories, but for the moment, I wish to note the consciousness-raising motivation driving his ‘negative aesthetics’.63

NORTH AMERICAN STRUCTURALISM

Boredom is a powerful tool.

Peter Campus, 2008

There was considerable overlap between the British structural/materialist movement and structural or underground film in the USA and Canada. Like their British counterparts, North American filmmakers such as Bruce Connor, Paul Sharits, Joyce Wieland and Ken Jacobs followed the modernist precept of ‘truth to materials’, and drew attention away from the symbolism of narrative content, refocusing on the ‘materiality of the medium [and] the formal structure or shape of the film’.64 According to A. L. Rees, this marked the moment when ‘form became content’, and, as in the UK, the new opacity of film gave rise to the possibility of reflecting on the experience of spectatorship, as the work unfolded.65 The term ‘structural film’ was coined by P. Adams Sitney in his text Visionary Film – The American Avant-Garde (1974) in which he enumerated the characteristics of a structural film: a fixed camera position, the strobe effect (a technique perfected by Paul Sharits in his flicker films), the use of loops or repetition and filming pre-existing footage off the screen.66 In fact, very few films conformed exactly to these requirements and, according to Rees, many practitioners rejected the notion of structural film altogether. He quotes Hollis Frampton who in 1972 opined that the term structuralism ‘should have been left in France to confound the Gaul for another generation’.67 In spite of filmmakers’ aversion to being in any way misrepresented and their need for their particular interpretation of the zeitgeist to be accurately defined, the term ‘structural film’ adhered to a wide range of practices arising from the new engagement with the semiotics, materials, apparatus and processes of film.

TEMPORAL TAMPERING: FAST AND SLOW

Time, said A … was by far the most artificial of all our inventions.

As I have outlined, the foregrounding of filmic language took place when artists flagrantly broke the rules of mainstream cinema and a few examples from both sides of the Atlantic may give a flavour of the aesthetics to which this approach gave rise. Artists disrupted the sequential flow of film, the apparent unfolding of dramatic events within a linear temporality that in the syntax of film approximates the pace of life. ‘It is a mistake to think of the cinematographic image as being by nature in the present’ observed Gilles Deleuze,69 and avant-garde filmmakers set out to prove the elasticity of time by compressing, stretching and looping it, disrupting the logic of conventional cinematic continuities. Film time was accelerated by means of rapid camera motion – hand-held on the hoof, or shot from fast-moving cars or trains. An epidemic of quick-fire editing erupted that not only thrust into the limelight the invisible joins beloved of skilful industry editors, but also pushed the work to the limit of perceptual legibility, thereby destroying the internal narrative coherence of the film. Marie Menken used stop-motion in her vertiginous Go! Go! Go! (1962), a work in the ‘city symphony’ tradition of early European film, but taken at breakneck speed. The camera races us through the city, past the docks milling with workers, along body-strewn beaches, stopping off momentarily for social events – a graduation day, a body-building contest and a debutante ball – the filmmaker abandoning herself to the chance delights of a summer in New York City. The swiftness with which the film moves makes it impossible to linger over any particular scene and there is no narrative in the conventional sense.70 However, as is the case in practically all the structural films of the period, a narrative of sorts emerges, whether by chance or by subconscious intent. The film demonstrates both a sensuous opticality, reaching almost hallucinatory levels in the forward momentum of the camera in flight. The pace of the film is analogous to the energy of a city on the brink of profound social change, but with vestiges of more conservative times glimpsed in the twirl of the debutantes’ dresses. Today the film has acquired a patina of nostalgia as we recognise the shortening skirts, the bouffant hairdos, and formal suits of the men on their way to work. We are now looking at an example of Catherine Russell’s ‘archival cinema’, a record of a city in transition, a social document as well as a fine example of the anti-narrative impulse of the American avant-garde.

Chris Welsby, Park Film (1972–3), 7min., 16mm, silent (24fps). Courtesy of the artist.

In the UK, the use of time-lapse to compress both time and space was much in evidence, principally in the work of William Raban, Mike Leggett and Chris Welsby whose Park Film (1972–3) recorded three days in the life of a London park, an oasis of green in the built environment of the metropolis. Like many artists at the time, Welsby was influenced by Gregory Bateson’s systems theory and structured his filmic observations of nature according to pre-set rules, in this case, exposing a single frame each time an individual passed through the fixed frame view of the park. Over a number of films, Welsby combined film technology with aleatory elements. In Park Film, these took the form of moving bodies, the frequency of their appearances dependent on the vagaries of the weather, fewer when it was raining and more in clement weather. The film, then, was constructed as much by the weather as by the camera and the artist, and as Welsby himself declared, Park Film was not a film about a park but ‘a film that was part of the park as much as a film can be’.71 Beyond the elegance of its conceptual framework, the film provides a kaleidoscopic portrait of a place in which twitching, stick-like people have a Lowryesque charm.72 However, the assimilation of the ‘stuttering’ figures into the landscape also provides an environmental resonance while a certain magic arises from the evocation of what a later exponent of time-lapse, Emily Richardson, described as ‘the breath of nature’.73 For her – and, I suspect, for Welsby before her – these depictions of human traffic andthe invisible labours of nature are also ‘suggestive of inner worlds or states of mind’.74

At the other end of the scale, decelerated film was cooling the pace in the form of both slow motion and the long duration of the films themselves. Following Abel Gance, artists such as Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, Joyce Weiland and Andy Warhol extended the conventional running times of narrative films, notably Warhol’s Sleep (1964), in which ‘real time’ shots of a sleeping man were spliced together, monitoring six hours of his slumbers. The experience of being licensed to stare at another individual not only indulges the fetishism of the gaze but also demonstrates its ultimate frustration. The face alone tells us little about the reality of the man to whom it belongs and although history reveals that he was John Giorno, Warhol’s lover, the film itself betrays none of his secrets. We are left with our own scopophilic desires and the conditioned assumptions we project onto the beauty of Giorno’s supine form.

As we have seen, in the UK, David Hall regarded time as a creative tool, elaborating his notion of ‘sculpting in time’ across film, video and installation, while in Canada Michael Snow endowed time with specific weight, enabling him, through film, to ‘make a shape in time’.75 Like Hall and Snow, Hollis Frampton celebrated the formal properties of time which, he said, in cinema are ‘precisely as plastic, malleable and tactile as the physical substance of film itself’.76 He also designated time as the central metaphor of film, one that is experienced by the viewer as ‘the density, the sense that something will happen; that nothing will happen’ and in this respect, ‘time is the name for something which is consciousness’.77 Malcolm Le Grice explored the relationship between space and time noting that temporal tamperings change ‘spatial perception through progressively altering the rate of change of the image’.78 Taking Chris Welsby’s time-lapse films as an example, Le Grice observes that ‘when time compression results in a rapid apparent motion, then the rate of change in the images begins to visibly deform the space being recorded’.79 Bringing down the tempo once again, Peter Gidal, the master of slow films, also embraced duration ‘as a material piece of time’80 and argued that boredom in the face of interminable durational films was a passport to a higher level of consciousness. This is a sentiment recently echoed by Tacita Dean who confessed:

I do court boredom, what is euphemistically called longueur … there is a sort of surrender … you have to give yourself up to it visually. There isn’t a narrative thread, the narrative is the narrative of the day passing.81

In this existential time-space it is possible to experience what Dorothea Franck calls the ‘depth of time in contemplative experience [in] full presence’.82 The longueurs of real-time films by Dean, and Gidal before her, therefore encourage sustained meditation on temporality and also bring the timeframe of the film and that of the viewer into a 1:1 equivalence. This becomes a feature of much moving image installation in the later part of the twentieth century and into the new millennium, notably Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho (1995) and Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010). Kate Mondloch has argued that works such as these stage time in space, and there has been no starrier staging than Marclay’s filmic chronometer made up of countless classic movie clips.83 What links them is a direct reference in each to times of day, signalled by clocks, watches and actors declaring ‘time for tea’, the ensemble synchronised precisely to real time. No less impressive was Gordon’s reworking of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), an attenuated, 24-hour, ultra-slow motion version of the film classic. Melissa Gronlund has argued that slow motion solidifies time into an object or a ‘time portrait’ that in the case of 24 Hour Psycho ‘forces attention onto each frame as an image to be beheld rather than a film to be watched’.84 Paul O’Kane has found in the ‘glacial time’ of slow motion the same revelation of nature that Richardson discovered in time-lapse. ‘Slow motion,’ he writes ‘not only presents familiar qualities of movement but reveals in them entirely unknown ones […] The act of reaching for a lighter or a spoon is familiar routine, yet we hardly know what really goes on between hand and metal.’85 The conceit of Gordon’s reworking of Psycho was that the slow, forensic analysis of human movement and bodily expression was simultaneously the unveiling of cinematic artifice, dismantling the thin disguises of acting, costume, props and studio scenery. The enactment of simple gestures was now lifted into the realm of what O’Kane dubbed ‘supernatural motions’.86

High-speed digital technology has allowed Bill Viola to produce video portraits of actors emoting grief in extreme slow motion, the image barely breathing. In The Passions (2000–3), he achieves very high image resolution ironing out the visible scan lines that distinguished analogue video and the grain that was such a feature of Psycho’s slow motion, thereby renouncing what O’Kane christened ‘the special grace awarded by grainy black-and-white cine film’.87 Curiously, by reducing the moving image to virtual stasis – the progress of the image in The Passions is barely perceptible – the emotional transport that O’Kane attributes to slow motion is also extinguished. Without the support of narrative context, a storyline that might provide a clue to the actors’ apparent distress, the work remains clinically objective.88

REPETITIONS, LAYERS AND LOOPS: SCRATCHING AND PAINTING

The rejection of narrative and continuity, of ‘one damn thing after another’89 in experimental film of the 1960s and 1970s often entailed the use of repetition and loops, devices designed to counter narrative progression and extend time indefinitely, with only the gradual erosion of the film circulating through the projector as a verifiable register of change. Like rapid edits and slow motion, repetition remains a staple of experimental film, and similarly unravels the sequential march of time to which mainstream film is confined. We will return to the repeat edit in our discussion of video in chapter eleven, but here it will suffice to note the ability of repetition to unfix given meaning, to wrest the sign from its referent and reinvest the image with new connotations, both emotional and semantic. Repetition, which Catherine Fowler describes as a ‘double exposure’, can evoke the circularity of obsessional behaviour, the inescapability of recurring nightmares and the pitiless replay of anxieties that lead to mental breakdown.90 In Anticipation of the Night (1958), Stan Brakhage adopts a tight, claustrophobic framing, defamiliarising a montage of his everyday environment. A handheld, restless camera picks out menacing shadows of hands, arms, the agitated headlights of oncoming traffic, tangled foliage, glimpses of a child. These images briefly fill the screen but keep returning, like the unwelcome hallucinations of a ‘bad trip’, anticipating another dark night of the soul. As P. Adams Sitney observed, when an image recurs, ‘it gains new meaning through its new context and in relation to the material that has passed during the interval’.91 In the reiterative poetics of Malcolm Le Grice’s Berlin Horse (1970), the image sheds layers of its original meaning as it acquires its new symbolic carapace. A short sequence of film depicting a horse circling its trainer on the end of a leading rein is repeated, reversed and colourised, and finally juxtaposed with a second film clip, this time a similarly reworked fragment of early newsreel of horses being hurried out of a burning barn, to escape the conflagration. The hypnotic repetition of the images with subtle variations in visual treatment on each iteration, and the accompanying trance-inducing soundtrack by Brian Eno, erode and shift the meaning according to the viewer’s own associative proclivities. My own reading of the film gradually transmigrated from an appreciation of the magnificence of the animal to feeling, somewhere in my bones, the tension between it and the unseen trainer, the febrile line connecting them a symbol of the horse’s captivity, one that was ground into the repetitive structure of the film. Le Grice himself regards the film as an exploration of the paradoxical relationship between ‘the “real” time, which exists when the film was being shot’ and ‘the “real” time, which exists when the film is being screened’.92 Where filmmakers like Gidal and Warhol employed ‘real time’ to create a 1:1 equivalence between the two temporalities, Le Grice with his mesmeric loops and repetitions demonstrated how that equation ‘can be modulated by technical manipulation of the image’.93 Mainstream film achieves temporal elasticity by compressing time – ‘five years later’ – and through the digressional time travel of flashbacks as well as the simultaneity of parallel editing – ‘meanwhile, back at the ranch’. However, none of these contrivances breaks the illusion of continuity, what Le Grice calls a ‘consequential temporality’.94 Ultimately, they do little to compromise the linear unfolding of events onscreen, a construct that mirrors the spectator’s own conceptualisation of how time, measured out, regulates and gives meaning to her progression through life. Berlin Horse makes it difficult to establish that temporal equivalence, because of the lack of distinctive, logical, forward momentum in the film, because of its uncompromising, vertiginous circularity.

Malcolm Le Grice, Berlin Horse (1970), simulated film strip of 16mm double projection film. Sound: Brian Eno. Courtesy of the artist.

In the middle of Berlin Horse there is a transitional section in which the equine sequences, for a time, alternate and then are superimposed, one image swimming into the other. Superimposition, the layering of the image, was a widespread practice in experimental film of the 1960s and 1970s. In Ming Green (1966), Gregory Markopolous built up pictorial layers using double and triple exposures, so that images of evocative interiors repeatedly drown in a vortex of complex patterning, what David Curtis defined as the visual equivalent of ‘a ricochet of ideas’,95 only to resurface into brief legibility before once again being overwhelmed by new strata of visual information.

As we saw in our discussion of abstract film, some practitioners created these cinematic palimpsests by scratching and painting directly onto celluloid, the process of ‘handmade films’ being structured around a confederacy of predetermination and chance. In this way, it was possible to foreground the surface and materiality of the filmstrip, ‘the field of grain that bears the image’.96 Ultimately, it is the interaction of surface and depth established in painting that determines the formalist approach in film, one that Grahame Weinbren characterises as ‘emphasizing the interface between a physical screen and a non-material depiction’.97 At the same time, artists such as Pat O’Neill in the USA and Jeff Keen in the UK simply revelled in the highly decorative knots of visual incident they could now generate, combining macerated found footage with sequences they shot themselves as well as graphic interventions to the surface of the film. Direct filmmaking created abstract pictorial condensations that, argued Le Grice, ‘work in [their] own time’.98 They seem to rise up out of the temporal flow of the film into a state of suspended animation, or stasis, analogous to the condition of abstract painting.

It is in these heady concentrations of levitating signs that we become aware of the distinction between the Greek concepts of kairos that defines how time feels, and chronos, chronological time that simply marks the duration of events. This leads us into the complexities of Gilles Deleuze’s theories about time. Although he makes no reference to experimental film or video in his great tract Cinema 2: The Time-Image (1985), his notion of non-chronological time has been widely applied to artists’ moving image. Deleuze draws on the philosophy of Henri Bergson, who argued that our perception of time cannot be reduced to the forward march of unitised, consecutive, horological time, when our experience of time is stretched and compressed according to circumstances – from the endlessness of a reverie to moments of crisis when events seem to flash by in an instant. The relationship between past, present and future is equally difficult to define when the past pulls a veil of memories over the present and projections into the future similarly permeate our experience of the ‘actual’, the here and now. According to Deleuze, non-chronological time is therefore ‘at once a past and always to come’.99 More relevant to our purposes is Deleuze’s notion of ‘time images’ in which the linear propulsion of narrative hesitates before an ambiguous pictorial phenomenon – a figure halted by a reverie whose origin remains unexplained, an action that contradicts what has gone before. Cognitive dissonance, the inability to cohere meaning within a logical, pre-existing framework, instigates protracted forays into memories of scenarios and images past that might elucidate what is presented now to the eye, resulting in a swelling of the experience of the present by the past. Maya Deren’s earlier formulation of ‘vertical investigation’ is relevant here, a concept she developed in the 1940s. The filmmaker saw the forward march of a narrative as a ‘horizontal’ temporality based on ‘the logic of actions’.100 In contrast, on a ‘vertical’ axis, can be found moments in film that are ‘concerned with quality and depth’. These are ‘held together by an emotion or a meaning that they have in common’. Such intensities, Deren contends, are analogous to ‘the structure of poetry’, an art that shares a non-linear dynamic that, following Deren, Catherine Fowler attributes to the ‘vertical’ expansion of meaning in film. In moments that give us pause, there is instituted a temporality that ‘does not move on but moves back and around’ its subject.101 Vertical meanings thus exist in ‘a time of meanwhile’ and ask us to stay with and ‘think around’ an event.102 When the image on the screen is of another human being, ‘staying with’ the subject becomes critical to the depth of engagement that can be achieved. ‘We initially perceive individuals as objects’ observed the artist Olivier Bardin, ‘we … need time to recognise them as subjects’.103 The sustained ‘Screen Test’ film portraits by Warhol in the 1960s, or Breda Beban and Hrvoje Horvatic’s Geography in 1989, offer us the opportunity to ‘stay with’ another person, to register the lineaments of a face, and, over time, to catch the fleeting expressions that play across human features as the interior life momentarily breaks the surface.

The temporal investigations by experimental ‘film as film’ artists, their expansion, contraction and looping of time, has been applied to moving image installations, particularly those fielding several screens. Here, the artist hails the passing viewer with a succession of Deren’s moments of verticality, with a series of enframed cinematic events that invite the viewer to step out of literal space and chronological time and experience the imaginative amplification (or contraction) of both dimensions.

NOTES

1 Michael O’Pray (ed.) (1996) The British Avant-Garde Film, 1926 to 1995. London: Arts Council of England/John Libbey Media, p. 2.

2 Ibid. In spite of his endorsement of the term ‘underground film’, O’Pray himself settles for ‘avant-garde’ for the title of his book.

3 For instance Screen, Millennium Film Journal, Film Forum and October.

4 A. L. Rees ([1999] 2011, 2nd edn) A History of Experimental Film and Video. London: British Film Institute/Palgrave Macmillan, p. 79.

6 See Peter Wollen ([1975] 1996) ‘The Two Avant-Gardes’, in Michael O’Pray (ed.) The British Avant-Garde Film, 1926 to 1995. London: Arts Council of England/John Libbey Media, pp. 133–44.

7 See Michael O’Pray (ed.) (1996) op. cit.; A. L. Rees (2011) op. cit.; David Curtis (2007) A History of Artists’ Film and Video in Britain. London: British Film Institute; and Malcolm Le Grice (1977) Abstract Film and Beyond. London: Studio Vista.

8 Tom Gunning (1994) ‘An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator’, in Linda Williams (ed.) Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, p. 117.

9 Ross Brown speaking at the London College of Communication, 23 March 2011. The actor Jos Vantyler in the lead role as Robin Hood at the Oxford Playhouse in 2013 revealed that during the performance, he had little sense of what was going on in the auditorium and was informed about the different levels of audience reactions via an earpiece.

10 See Christian Metz ([1967] 1974) Film, Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema, trans. Michael Taylor. New York: Oxford University Press.

11 See Giuliana Bruno ([2002] 2007, 2nd edn) Atlas of Emotion. London: Verso.

12 See Mieke Bal (2013) The Politics of Video Art Installation According to Eija-Liisa Ahtila. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

13 I will discuss the work of Tim Smith and other cognitive scientists who study film spectatorship in the concluding chapter.

14 See Christian Metz (1982) The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema, trans. Celia Britton, Annwyl Williams, Ben Brewster and Alfred Guzzetti. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

16 Tim O’Riley (2005) ‘Representing Illusions: Space, Narrative and the Spectator’, in Katy Macloed and Lin Holdridge (eds) Thinking Through Art: Reflections on Art as Research. London: Routledge, p. 72.

17 Luke Gibbons (1996) Transformations in Irish Culture. Cork: Cork University Press, p. xii.

18 Slavoj Žižek in conversation with Julian Assange, 2 July 2011, Troxy Theatre, London.

19 A survey of the impact of social media and the Internet on art practice is beyond the scope of this book. See Omar Kholeif (ed.) (2014) Art After the Internet. Manchester: Cornerhouse.

20 Malcolm Le Grice speaking at Expanded Cinema, the Live Record, 6 December 2008, BFI Southbank, London.

21 Jacques Lacan ([1936] 1977) ‘The Mirror Stage as formative of the function of the I’, in Ecrits: A Selection, trans. Alan Sheridan. London: Tavistock, pp.1–7.

22 Virginia Woolf (1926), op. cit.

23 Leo Tolstoy ([1849] 2009) Anna Karenin, trans. Rosemary Edmonds. London: Penguin, p. 490.

26 See Laura Mulvey (1981) ‘Afterthoughts on “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” Inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946)’, Framework, 15, 16, 17, pp. 12–15; see also Laura Mulvey (1996) ‘Film, Feminism and the Avant-Garde’, in Michael O’Pray (ed.) The British Avant-Garde Film, 1926 to 1995. London: Arts Council of England/John Libbey Media, 199–216.

27 Barbara Follett quoted in Steven Adams (2008) ‘Girls just want to win The X Factor or marry a footballer, says minister’, Daily Telegraph, 14 October. On the Barbie-fication of culture today, see Natasha Walter (2010) Living Dolls: The Return to Sexism. London: Virago, pp. 199–216..

28 Natasha Walter (2010), ibid., p. 11; see also Cordelia Fine (2010) Delusions of Gender: The Real Science Behind Sex Differences. London: Icon. Fine examines the recent attempts of neuroscientists to explain the differences between male and female behaviour in terms of divergences in brain structure.

29 ‘From an early age, the girls surveyed had held conventionally stereotypical views about jobs for men and women. They retained those views throughout their schooling despite being taught about equality of opportunity and knowing their rights to access any kind of future career.’ Ofsted report (2011) Girls’ career aspirations, p. 5. Available online: http://www.dtc.org.au/Documents/236.pdf (accessed 17 November 2013).

30 See Angela McRobbie (2009) The Aftermath of Feminism. London: Sage.

31 I am grateful to Catherine Long for drawing my attention to McRobbie’s writing.

34 Ian Christie, unpublished notes towards a presentation at the AHRC MIRAJ conference, University of the Arts London, 2011.

35 Nicky Hamlyn (2010) Medium Practices, unpaginated, unpublished essay.

36 André Bazin ([1958] 1960) ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’, trans. Hugh Gray, Film Quarterly, 13: 4, pp. 4–9.

37 Richard Allen (1997) Projecting Illusion: Film Spectatorship and the Repression of Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 91.

41 See Catherine Elwes (2013b) ‘Figuring Landscapes in Australian Artists’ Film and Video’, in Jonathan Rayner and Graeme Harper (eds) Film Landscapes. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 164–83.

42 In 2014, the actress Sandra Bullock was confronted by stalker Joshua James Corbett who had penetrated her home as far as her bedroom door. The Los Angeles Times reported that ‘they found photos of the actress in his pockets, a letter portraying himself as her husband and the love of his life and a concealed weapon permit from Utah’ (July 15). Other actors who have been stalked include Halle Berry, Selena Gomez and Rebecca Schaeffer, who was murdered by a stalker in 1989; see http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-sandra-bullock-stalker-bedroom-20140715-story.html (accessed 17 July 2014).

43 Anthony Swofford (2003) ‘The Sniper’s Tale’, Guardian Weekend, 10 March.

44 The current (2014) debates in the British government about the influence of Islamic fundamentalists in British schools highlight the role of faith schools of all denominations in forming the minds of the young.

45 The title of Tony Oursler’s 2000 installation, Soho Square, London.

46 See, for instance, Walter Metz (2001) ‘“What Went Wrong?”: The American Avant-Garde Cinema of the 1960s’, in Paul Monaco (ed.) The Sixities: 1960–1969. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 260.

48 Michele Aaron (2007) Spectatorship: The Power of Looking On. London: Wallflower Press, p. 4.

49 Nicky Hamlyn (2010), op. cit., unpaginated.

50 Laura Mulvey (1975), op. cit.

52 See Peggy Phelan (1993) Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London: Routledge, p. 4.

53 ‘Active vanishing’ can also be found in more contemporary work. In 2006, the Swedish artist Kajsa Dahlberg made the video Female Fist in which an activist speaks of the difficulties involved in creating lesbian pornography in a hetero-normative culture. Like Rhodes, Dahlberg maintains a black screen, but adds subtitles. I am grateful to Catherine Long for alerting me to Dahlberg’s work.

54 Peter Wollen ([1975] 1996), op. cit., p. 140.

55 I once attended an event at the Chenies Street Drill Hall in London where Mary Kelly was in conversation with Susan Hiller. Hiller, with her background in anthropology and Kelly drawing on psychoanalytic theory together wove a fascinating discourse on their respective practices, one that went over the heads of the majority of assembled women. This led to hostile accusations of obscurantism and the inappropriateness of adopting ‘male’ theoretical models (Lacan, Saussure, Freud et al) to illuminate women’s lives. Kelly attempted to heal the potential breach in the ranks by suggesting that her crypto-visual work, including her Post Partum Document (1973-79) operated on many levels, both aesthetic, emotional and theoretical and that it was possible to approach it according to one’s abilities and education. The implied feminist hierarchy somewhat undermined Kelly’s attempt to placate the audience.

56 Peter Gidal (1975), op. cit., pp. 189–96.

57 Peter Gidal (1996) ‘Theory and Definition of Structuralist/Materialist Film’, reprinted in Michael O’Pray (ed.), op. cit., p. 153.

58 Peter Gidal (2001) ‘There is no other’, Filmwaves, 14, p. 58.

59 Philip Drummond (1979) ‘Notions of Avant-garde Cinema’, in Film as Film catalogue. London: Hayward Gallery/Arts Council of Great Britain, p. 14.

60 Robert Hughes (1979) ‘10 Years that Buried the Avant-Garde’, Sunday Times magazine, 30 December, p. 19.

61 James Donald’s term, quoted by Steven McIntyre in his perceptive reassessment of Gidal’s contribution to film theory and education; see (2013) ‘Peter Gidal’s anti-narrative: An art of reprisal reappraised’, MIRAJ, 2: 1, pp. 26–37.

62 Peter Gidal (1996), op. cit., p. 189.

63 James Donald (ed.) (1989) Fantasy and the Cinema. London: British Film Institute, p. 4.

64 Deke Dusinberre (1977) ‘Some early films by Peter Gidal’, catalogue essay in Perspectives on British Avant-Garde Film, Hayward Gallery.

65 A. L. Rees [2011], op. cit., p. 79.

66 See P. Adams Sitney (1974) Visionary Film – The American Avant-Garde. New York: Oxford University Press.

67 Hollis Frampton quoted by A. L. Rees [2011], op. cit., p. 81.

68 W. G. Sebald ([2001] 2002, 2nd edn) Austerlitz. London: Penguin, p. 14.

69 Gilles Deleuze (1989) Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, p. 105.

70 The film is available online and in the digital age it is possible to freeze individual frames and access the detail that was so difficult to grasp in the original screenings. This new ability to still the film gives rise to what Raymond Bellour has called the ‘pensive spectator’, a theme I will return to, but in the meantime it is worth taking a moment to appreciate this film online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s3PvFohWfPo (accessed 6 January 2014).

71 Chris Welsby (2013) ‘In Conversation with Catherine Elwes’, MIRAJ, 2: 2, p. 316.

72 Allan Cameron and Richard Misek have observed that the ‘stuttering’ effect of time-lapse tends to ‘decorporealise’ human figures – they become like automata, an incidental effect of the technology; see Allan Cameron and Richard Misek (2014) ‘Time-lapse and the projected body’, MIRAJ, 3: 1, pp. 38–51.

73 Emily Richardson (2008) Catalogue entry in Steven Ball, Catherine Elwes, Eu Jin Chua (eds) Figuring Landscapes: Artists’ Moving Image from Australia and the UK. London: Arts Council England, p. 80.

75 Michael Snow in conversation with Chris Meigh-Andrews and Elisabetta Fabrizi, BFI Southbank, London, 6 December 2008.

76 Hollis Frampton speaking at An Evening with Hollis Frampton, 8 March 1973 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Audio recording available through MOMA sound archives: www.moma.org/learn/resources/archives.

78 Malcolm Le Grice (1982) Abstract Film and Beyond. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 126.

80 Peter Gidal (1996), op. cit., p. 153.

81 Tacita Dean speaking to Isaac Julien on a Guide to Artists’ Filmmaking, BBC Radio 4, 18 January 2011.

82 Dorothea Franck (2010) ‘Deep Looking: A Buddhist Look at the Work of Stansfield/Hooykaas’, in Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds) Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij De Buitenkant, p. 127.

83 See Kate Mondloch (2010) Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

84 Melissa Gronlund (2012) ‘Observational film: Administration of social reality’, MIRAJ, 1: 2, p. 173.

85 Paul O’Kane (2012) ‘On Making Art’, Art Monthly, 360, p. 2.

88 This is in contrast to Crying Men (2004), a photographic work by Sam Taylor-Wood featuring well-known actors weeping. The images are still, the men are acting but the tears, we assume are real and in order to produce them, each man will have drawn on his own reservoirs of painful memories. The impact of these autobiographical tears, these fragile moments when ‘big boys’ do cry, is in many cases, surprisingly moving.

89 Attributed variously to Arnold Toynbee/Winston Churchill/Mark Twain: ‘History is “just one damned thing after another”’.

90 Catherine Fowler (2004) ‘Room for experiment: gallery films and vertical time from Maya Deren to Eija Liisa Ahtila’, Screen, 45: 4, p. 328.

94 Malcolm Le Grice (1996) ‘The History We Need’, in Michael O’Pray (ed.) (1996) The British Avant-Garde Film, 1926 to 1995. London: Arts Council of England/John Libbey Media, p. 186.

95 David Curtis, in conversation with the author, sometime in the late 1990s.

96 Nicky Hamly (2010), op cit..

97 Grahame Weinbren (2012) ‘Coloured paper in monument valley: Contradictions, resonances and pluralities in the art of Pat O’Neill’, MIRAJ, 1: 2, p. 160.

98 Malcolm Le Grice, Luxonline website, op. cit.

99 Gilles Deleuze ([1989] 2005) Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, p. 123.

100 All Maya Deren quotes are from an address to the Poetry and the Film Symposium, 28 October 1953. Available online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HA-yzqykwcQ (accessed 12 January 2014); see also Maya Deren ([1946] 2001) ‘An anagram of ideas on art, form and film’, in Bill Nichols (ed.) Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 7–49.

101 Catherine Fowler, op. cit., p. 328.

103 Olivier Bardin quoted by Maeve Connolly (2014) TV Museum: Contemporary Art and the Age of Television. Bristol: Intellect, p. 113.