Never before has an artist been able to summon instantaneously an image, which reconstitutes itself ceaselessly before our eyes…

René Bauermeister, 1976

TELEVISION ROOTS

By the mid-1960s, the general population of the UK was watching a potential eleven hours of broadcast television per day. Gallery-goers were already familiar with the gleaming face of ‘elsewhere’ trapped in a box, its quality of instantaneity, its promise of connectivity, its ‘community of address’.1 The viewing public was already fluent in the representational language and spectatorial codes of television when artists engaged with and re-cast television as installation art. At home, the television displaced the hearth as the focus of family life. The ‘box’, nested within the four-walled enclosure of the home, first appeared as a humble piece of furniture sometimes equipped with a sliding door that could be drawn across the screen at night to allow the normal patterns of human intercourse to resume. ‘Viewing a TV receiver,’ mused David Hall, is like

looking at a picture-box … something we have at least got manual control over, if not the content. It is an object which exists in the same continuum as ourselves. We can become involved in it, but never lost in it.2

The home television of the 1960s formed part of a well-lit domestic installation surrounded by the paraphernalia of everyday life, furnishings, ornaments and interior design embelishments that all competed for attention with the eerily glowing screen. In addition, family comings and goings periodically broke into the flow of broadcast material resulting in Peter Osborne’s ‘distracted spectator’. An evening’s viewing was itself fragmented, interrupted by commercial breaks, news bulletins and announcements. In the early days, it was not always easy to read the flickering, black-and-white pictures as a window onto another, parallel reality. The image resolution was poor and one peered into the equivalent of Maxim Gorky’s ‘Kingdom of Shadows’ glimpsed through a London fog, an unheimlich netherworld in the heart of the home.3 The frontal viewing position, determined by the normal optical range, and the modest size of the standard television screen set in a thick casing, provided further conditions of distanciation. Owing to the constellation of factors compromising viewers’ attention to broadcast content, early television was heavily dependent on narrative codes derived from theatre and cinema, repetitive formats and, crucially, dialogue that could be followed even while in the kitchen making a cup of tea. The ability of sound to penetrate beyond the immediate vicinity of the television set contributed to the success of early broadcasting.

From the outset, the ‘liveness’ of television and the direct address to the audience by presenters created what John Ellis has called a spurious ‘co-presence’ across the technological divide.4 Similarly, Maeve Connolly has noted that ‘television separated people and connected them simultaneously’.5 The human scale of the head and shoulders onscreen enhanced this effect of untouchable intimacy. Like a distant friend of the family, ‘Auntie Beeb’ chatted from ‘the box’ encouraging everyone to sit back and enjoy the show. By the end of the 1960s, the seriousness of tone adopted by early public service broadcasting was entirely abandoned in favour of ‘Happy Talk’, the jaunty delivery we are familiar with today.6 David Hendy has attributed the power of radio and, by extension, of television, to the warm timbre of the presenters’ voices, observing that ‘the friendlier the voice, the more the listeners obey its commands’.7 Peggy Gale has emphasised the anthropomorphism of the TV set, which ‘projects its message from within as would a person who is interacting directly with us’.8 Chantal Akerman attributes the human effect to the frontality of the device: ‘When I am facing you’, she declares, ‘we have a strong relationship’, one that is non-threatening.9

The manufactured camaraderie of the TV host assumes a common culture underwritten by a putative political neutrality, exemplified in the UK by the BBC and by other state broadcasters such as France Inter across the channel. At its inception, the BBC established a laudable Reithian commitment to the continuing education of the British people and also undertook the somewhat imperial task of ‘spread[ing] throughout the world the doctrine of common sense’.10 Early video artists accused the Corporation and commercial television stations of serving the interests of the establishment rather than those of viewers. J. G. Ballard argued that ‘the real aim of TV is fulfilling its own needs’.11 Promoting loyalty to familiar TV faces kept the viewing figures healthy, which in the case of commercial television stimulated consumerism and guaranteed the flow of advertising revenue.12 In 1973, by means of scrolling texts, Richard Serra’s eponymous video proclaimed, ‘television delivers people’ to the corporations and to add insult to injury, ‘the viewer pays for the privilege of having himself sold’.13 Television, continued Serra, ‘is the basis on WHICH YOU MAKE JUDGEMENTS. By which you think.’ Framed by a declared critique of the pervasive and pernicious influence of television, but fired by a genuine fascination with the creative possibilities of a new medium, 1960s artists began to investigate.

A SHORT HISTORY OF VIDEO

When artists first installed televisions in a gallery, they were following the tradition of found objects established by Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain – the infamous urinal that he exhibited in 1917 at the Society for Independent Artists in New York. Both urinal and television are mass-produced objects, with TV receivers also carrying the association of the home environment in which female influence traditionally holds sway. David A. Ross described the introduction of monitors into the gallery as a ‘dissonant moment’14 in art and its association with domesticity may well account for the distinct lack of status attached to the device itself.15 ‘When people saw those screens in the gallery’, observed Steve Hawley, ‘they just thought about the domestic, they thought about having their tea’.16 The French Lettriste artist César displayed unalloyed hostility towards the new one-way communication device, and in Télévision (1962) he mounted a stripped-down working television on a scrap metal plinth, encased it in Perspex and in a public gesture, threatened it with a gun. A year later, Wolf Vostell, a proponent of the Fluxus principle of dé-collage,17 insulted a working television by throwing cream cakes at it. He then wrapped it in barbed wire and gave it a ritualised burial in a nearby field by way of a finale.18 No less critical of the babbling box, in Untitled (1970) Joseph Beuys covered the screen in felt, donned boxing gloves and accompanied by the muffled sounds of a daytime TV programme, repeatedly punched himself in the face. If we disregard for the moment the issue of César and Vostell’s menacing behaviour, and Beuys’s attempts to wake himself from a television-induced torpor, we can consider how the spectacle of the TV set placed centre stage in a temple of culture altered the viewer’s perception of a very familiar domestic appliance. Unlike the home environment, the gallery was rarely furnished with seating, leaving viewers standing to attention before the newly reified box. The absence of a sofa highlighted the conventional spatiality of television viewing delineated by a crescent of comfortable chairs surrounding the TV/hearth while the new freedom to circumambulate the three-dimensional ‘box’ brought to mind its more common position wedged into the corner of a room, its cabling coyly pressed to the wall. Artists not only snatched the set from its natural habitat and stripped it of its personalised domestic decorations, but in conformity with the modernist, deconstructive project, they also foregrounded the materials that create the image, exposing those parts of the apparatus that are normally concealed or ignored: the wires, casing and control knobs, as well as the television’s electronic innards.

The antagonism artists displayed towards this object of mass entertainment can be interpreted as a challenge to the power of television, a medium that Marshall McLuhan warned would compromise human interaction and transform social behaviours.19 César and Vostell were, perhaps, simply defending themselves. As indicated in chapter six, videomakers often rehearsed many of the same arguments about the pernicious effects of television viewing that structural filmmakers aimed at mainstream film. Artists resisted the exhortations of commercial television to purchase vast collections of non-essential consumer goods and services; feminist, black and gay activists lamented the lack of representation in the medium for minorities beyond the standard stereotypes; and the traditional status of television as the medium of truth, with the illusion of ‘infinite coverage’20 drew further criticism. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, television had already overtaken radio as the trusted portal onto news of the world and broadcasters were framing our picture of reality, and in Hendy’s estimation, ‘slowly rewiring our minds’.21 Colin Perry has argued that in the age of the Internet, ‘television’s power has not waned’ and corporate television in particular ‘has widened its potential reach’ online.22 Jonathan Crary has gone a step further and suggested that nowadays it is impossible to achieve ‘perceptual and cognitive experiences outside dominant possibilities offered by contemporary media and technology’.23 Early video installation artists were not yet exposed to this degree of psychic pollution from the mainstream, but they accurately predicted the gradual encroachment of televisual reality into our own.

Those who were motivated by strong political conviction fielded counter-cultural, ‘agit-prop’ campaign tapes supporting causes from ‘abortion on demand’, through racial equality to the miner’s strike.24 Others made more subjective works promoting alternative, minority worldviews. Anticipating the global reach of the Internet, many artists sought wider audiences through broadcasting and alternative social networks – the unions, women’s groups or residents’ associations – at the same time harbouring a natural mistrust of the ‘capitalist’ gallery system.25 However, artists were drawn to the medium for more than its discursive capabilities, its powers of advocacy and unorthodox distribution networks. Just as the devotees of expanded cinema built their critique of Hollywood whilst mining the hidden potentialities of celluloid film, the new portable video technology offered scope for creativity. Both the sculptural apparatus of television and the luminous quality of its image fed the imagination of artists. In the early 1980s, broadcasting provided Dara Birnbaum with the raw material for her mischievous television appropriations of Wonder Woman, the Winter Olympics and Kojak. By displacing and reworking these ‘time readymades’26 in a new context, the ‘natural’ relationship between TV images and their conventional meaning was disrupted, and as Birnbaum contested, her videos ‘called into question television’s claims to authenticity’.27 The original ‘pirater of popular cultural images’28 was quickly followed in the UK by the ‘scratch video’ movement spearheaded by George Barber, Sandra Goldbacher, the Duvet Brothers and Gorilla Tapes. Scratch, as much a product of VJ culture as art, has continued to evolve, reaching untold pictorial sophistication in the age of sampling and digital ‘mash ups’. The original scratch artists not only hijacked mainstream footage (often illegally) but they also developed a new formal language of fragmentation, with its bleeding colours, vertiginous layering and stuttering repeat edits, all of which were almost immediately appropriated by the burgeoning music video industry. Maeve Connolly holds the view that oppositional artists saw television primarily as an ‘object of reform’;29 however, Birnbaum tells us that in the early 1980s, she ‘chose to reinvest in American TV, both formally and politically.30 Like many women of her generation she had to contend with over-eroticised media stereotypes of femininity, so she purloined one of the few images of a powerful woman to be found on American television, albeit based on a cartoon character. In common with many feminist artists of the day, Birnbaum chose to ‘wrestle with the icon, continually: and with her full body weight’,31 a struggle perfectly encapsulated by her image of the determinedly and comically spinning Wonder Woman.32

For all their antagonism, Beuys, Vostell and César offered up a domestic appliance as an object of aesthetic contemplation as well as a wonder of contemporary design. Many other artists, notably Peter Donebauer in the UK, the Vasulkas in Europe and Nam June Paik in the US, were instrumental in developing pioneering image processing technologies for analogue video, synthesisers that were subsequently taken up by industry. It could be argued that the counter-cultural generation condemned the institutional conservatism of national broadcasting while enacting a rescue of the televisual. Birnbaum ‘re-paticularised’33 an idol of the small screen, while César plucked one lonely receiver from the obscurity of mass production and invested it with a tragic, flayed poetry, making a claim for its ‘aesthetic autonomy’.34 There is ambiguity in César’s armed confrontation with a TV. He may have been critiquing the medium that was set to dominate our conception of the world, but he was also celebrating the technological miracle that made it possible.

MIRROR, MIRROR

The mirroring effect of video, its live image-feedback, was one of the principal characteristics that distinguished the medium from film. John Baldessari declared that ‘video will become like a pencil in the artist’s hand’.35 With live relay of the image, it was indeed possible to work directly with the camera, as in a drawing, altering the image according to what emerged on the monitor. Live feedback also enabled artists to see themselves as they appeared to others and contemplate parts of their bodies – the back of the head (Vito Acconci), anus (Pierrick Sorin), epidermis (Nan Hoover) and, later, internal organs (Mona Hatoum) – that only a complicated arrangement of mirrors, or a microscope or x-ray would previously allow. The benefits of analogue video included the ability to work independently, following the most basic induction to the technology. In the privacy of a studio or at home it was possible to proceed without a crew and record for up to an hour uninterrupted, wiping the tape clean and starting again if the initial attempt proved unsatisfactory.36 The immediacy and intimacy with the video image promoted the sense of the medium as an extension of thought, with ‘nothing prior’.37 The investigative and spontaneous nature of video recording particularly benefitted artists engaged in identity politics in the 1960s and 1970s. They undertook a programme of self-scrutiny, drawing on autobiographical material as well as examining their culturally ‘marked’ bodies, as in a mirror. The experience of racism triggered by the colour of the artist’s skin was the subject of Howardena Pindell’s Free White and 21 (1980). The work intersects racial and gender discrimination as the artist, in a simple to-camera testament recounts a childhood in which a babysitter tried to wash her ‘dirty’ black skin with lye resulting in permanent scarring. She also describes the dismissal of her experiences as a black woman by white feminists.38 Pindell’s confident narration recalls Patricia Mellancamp’s observation that artists such as Cecilia Conduit and VALIE EXPORT ‘turned being looked at into an aggressive act’,39 and, quoting Mary Russo, she added, they ‘put on femininity with a vengeance’, which in turn ‘suggests the power of taking it off’.40 Video artists driven by diverse agendas embarked on the wholesale deconstruction and reconstruction of their body-image, in a bid to renegotiate the terms of their visibility.41

In the early years, artists such as Bruce Nauman, David Hall, Roger Barnard and Peter Campus enabled viewers similarly to interact with their own image by means of live relay. These video self-portraits were often multiplied, layered or intercut with pre-recorded material, or a time delay was introduced, confusing viewers’ conceptions of events as linear and obscuring the time code governing the technology. As they would in a hall of mirrors, viewers became disoriented, not knowing where they stood relative to the rest of the world, their sense of emplacement destabilised. Nauman’s stated aim was to balance gallery-goers ‘on the edge of one kind of way of relating to the space and another’, and they were ‘never quite allowed to do either’.42 This form of cognitive disturbance was also a side effect of Roger Barnard’s Corridor (1974) in which a camera above a narrow passageway recorded the progress of a spectator walking along its length. The image was then mixed with live footage of the next viewer travelling the same route as the first. The resulting layering of the image appeared to the first visitor on a monitor just beyond the corridor. In Barnard’s installation, the wholeness and integrity that the video mirror promises the ego was ruptured by the collapse of time and space as the recent past was inscribed in the present and phantom companions traversed spaces in which viewers believed themselves to be alone. By virtue of experiencing the work and drawing on a basic knowledge of the technology, that initial perplexity could be dispelled as spectators ‘learned’ the work. They began as what Thomas Elsaesser has nominated a ‘rube’, the dupe of early cinema who confuses illusion and reality and leaps from his seat to embrace the beautiful dancer onscreen.43 Momentarily then, the ‘rube’ spectator of Corridor finds she can no longer trust her proprioceptors, the sensors distributed throughout her body that locate her in space and establish the boundaries of her body, until, that is, she ‘gets’ the work and learns ‘afresh [a] different role and form of spectatorship’.44

The artist and critic Stuart Marshall suggested that installations employing the mirroring effect of closed-circuit video return the viewer to the moment psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan described as the ‘mirror phase’. As we saw in chapter six, this marks the first encounter of the still-uncoordinated infant with its own image in the mirror. The integrated, centred entity the child perceives gives birth to the fantasy of an idealised, masterful self that the individual strives to embody throughout life. Marshall postulated that video artists who self-display, and by extension, gallery-goers who are snared by the video mirror, all indulge in a nostalgic return to the mis-recognition of that ideal ‘other’ self.45 Rosalind Krauss famously objected to what she called ‘self-encapsulation’ in which viewers become fixated on their own video-image cutting them off from other objects, histories and the social sphere. They enter a closed circuit that produces a ‘collapsed present’ in which the viewer experiences the self as ‘other’ in electronic perpetuity.46 Krauss’s critique has since been challenged, notably by Anne M. Wagner who pointed out that a monitor ‘itself ask for monitoring’,47 implying a future spectator and an interpersonal connection across time that breaks the closed circuit. In Corridor, narcissistic absorption is tempered by the electronic layering and fracturing of the spectators’ video reflections. Narcissism is also inhibited by the technical imperfections and low resolution of the analogue black-and-white image, creating a kind of post-mesmeric condition, the spectatorial ego dissociated through its awareness of process. Corridor also reintroduced a social dimension with the added frisson of uncertainty about the physical status of those ‘other’ beings with whom the spectator shared the space of reception. Krauss herself conceded that the interruption of material reality – cables, monitors, walls and other people – breaks through the hermetic seal of the video bubble. She finds another mitigating structural element in Richard Serra’s Boomerang (1974), in which Nancy Holt listens to her own voice fed back to her on headphones with a slight but disorienting delay. Krauss identifies the use of audio feedback as the key to creating ‘an angle of vision’ for the spectator that allows her to ‘look onto it from outside’, thus breaking the narcissistic loop.48

If these distancing effects were not sufficient to stave off video vanities, the technology could also enact a decentering of the subject, for instance, through the infinite regressions of video feedback, an overused effect achieved by pointing the camera directly at the monitor to which it is connected. The mirror image fractures into a vortex of ever-receding multiples, an effect familiar to viewers of early Dr. Who (BBC 1963–present), in which the good Doctor regularly plunged through holes in time. The proliferation of selves might well carry sinister overtones of the doppelgänger as a portent of death; however, we now read video feedback nostalgically as a ‘naff’ special effect of early sci-fi television and the mind-bending psychedelia of the epoch. The more consequential impact of closed circuit video systems relates to today’s pervasive surveillance of public space, enacting Michel Foucault’s vision of the Panopticon that structures the all-seeing, controlling eye of authority.49 Lisa Akervall has suggested that the ‘complete visuality’ of our contemporary ‘networked selves’ represents an ‘inverted panopticon’ in which we are rewarded for constant self-exposure.50 Here appearance is paramount and the introjected ideal ego originating in the mirror phase, now conflated with current societal norms, acts as a constant companion, and we publicly self-flagellate for our failures to become the fairest, richest and most successful of them all.

VIDEO PERFORMANCE − LIVE

In chapter four, I touched on the ancestral links between performance and installation, and artists’ use of video as a vehicle for their own declamations to camera. I also discussed the combination of live and pre-recorded material in the work of artists such as Mona Hatoum, Rose Garrard and Vito Acconci. When the direct involvement of spectators in the outcome of a performance occurs, it emphatically reinstates the social in a medium overshadowed by Krauss’s accusations of narcissism. In Dan Graham’s Performer/Mirror/Audience (1975), a video system was installed in a large mirrored room registering the presence of the artist flanked by his audience, a group of seated students, who, he said, constituted ‘a public mass (as a unity)’.51 Graham ‘objectively’ narrated his impressions of his own reflected image as he walked across the room. He coolly described his clothes, the way he was standing, ‘a macho kind of pose’, the self-image he presented to the world. He shifted his weight from side to side, examined his hands, glanced at the audience and remarked, ‘people are smiling’. Graham now transferred his attention to his spectators, singling out hapless individuals, extracting them from the safe anonymity of the ‘public mass’, and subjected them to the same verbal appraisal of dress and gesture, mirroring them back ‘in terms of the performer’s perception’.52 Graham’s enforced exposure to public scrutiny of the students’ appearance once again anticipated the willing self-display that today proliferates on social media. In video events of the 1970s, however, the emphasis was not on remote connectivity enabled by technology, but on the re-inscription of the social in a live encounter with the work. Video performance was not intended as a simple antidote to the perceived narcissism of the medium; instead it played on the uncertain rules of engagement that attend performance art and, by extension, tested the boundaries of personal space and public behaviours. Graham’s video performances also signalled the difficulties that arise with the misalignment between the interior world of experience and what individuals succeed in communicating to others through the blunt instrument of language, verbal, sartorial and gestural. Finally, Performer/Mirror/Audience staged the power of institutions to fix identity. The law, the media, religion, education and employment all enforce the hierarchical organisation of human typologies through the allocation of specific roles to specific individuals. In his video performance, Graham assumed the power to name others in the context of his art and through the judgements of his commentary, symbolically established the value of each human presence he put in the spotlight.53

The ‘presentness’ of Graham’s performance underlined the capacity of video to parallel real time, to run alongside our own passage through life, in synch with what David Hall called the ‘real-time continuum’.54 In the late 1960s, video progressed in horological time because artists had no access to editing. The work ended when the tape ran out, inscribing an equivalence between the temporalities of recording and viewing. Where film was a frame-by-frame document of past events, ‘the elongated frame of the video image’55 created a fluid vision of time-in-the-making, even when pre-recorded. Video editing became available in the late 1970s and enabled artists to develop ‘methodologies for structuring time’56 through compression, acceleration, looping and deceleration – the ubiquitous slow motion. The phenomena of ‘seeing time’ in single screen works (David Ross)57 and ‘staging’ time in the spaces of video installation (Kate Mondloch) are also at play in live relay and performative works.

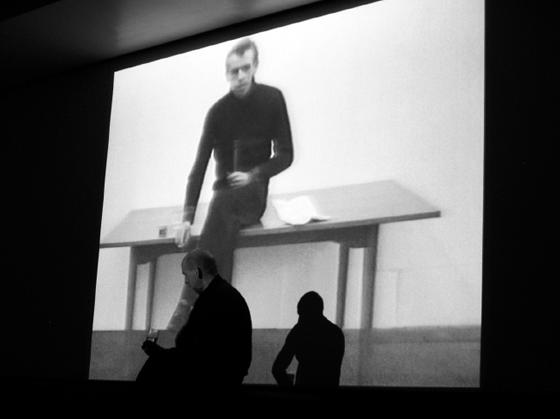

A more recent semi-scripted performance by Kevin Atherton encapsulates many of the characteristics typical of early video art: live relay, ‘self-performance’58 and the manipulation of time as a material. Atherton’s In Two Minds – Past Version (1978/2006) combined the live with the pre-recorded, not simply as an exercise in stretching or condensing history to fit the dimensions of the work, but to enact the enfolding of the past in the present. The first iteration of In Two Minds (1978) featured the artist performing live, engaged in a heated debate with a pre-recorded version of himself on a monitor. In 2006, the now considerably older Atherton submitted to the same grilling by his younger self across the time-space of over twenty years, with the youthful interlocutor now digitised and video projected onto a screen behind the older Atherton’s lean frame. The temporal gap between now and then was marked by the ageing of the artist’s face set against the nostalgic patina of the analogue black and white footage, the latter’s wavering scan lines saluting both Atherton’s longevity and the history of the medium. The passage of time was also registered by the changed cultural conditions described by the artist as an older man, and by the contrasting aesthetics and politics of the respective art worlds the two ages of Atherton inhabited. At the same time, young Atherton, suspended in the aspic of analogue video took part in an (albeit illusory) time travel into the present enacting a form of immortality through video technology.59 Slavoj Žižek has interpreted Freud’s death drive (thanatos) as a striving for an ‘un-dead’ condition, a living death immortalised in the movies by ghosts, ghouls and other entities beyond the control of the living. This ‘third dimension’60 can be achieved symbolically through video’s capacity to collapse time as we saw in Atherton’s performance, or physically by a walk-through video installation such as Corridor in which viewers themselves become the ‘un-dead’, ghosts in the machine indulging in a little technological haunting.61

Kevin Atherton, In Two Minds – Past Version (1978/2006). Video performance, Tate Britain, London. Photo: Catherine Elwes. Courtesy of the artist.

OBJECTS IN SPACE

Video is a face-to-face space.

Vito Acconci, 2003

As I have argued elsewhere, from the outset broadcast television was a fundamentally spatial phenomenon. There is a correspondence between the physical organisation of a television studio, with its simulated domestic spaces and stratified community of operatives, and the millions of crowded homes to which the studio is connected via the umbilical cord of the broadcast signal.62 This parallelism survived the transmigration of video technology to the gallery. Here, a congruence emerged between the artist’s studio and the gallery space, particularly when the two locations were collapsed as artists like Peter Campus, Joan Jonas or Dan Graham took up residence in the gallery. The gallery was transformed temporarily into the artists’ laboratory and the work occurred only in the moment of encounter between the technology, the artist/master of ceremonies and the spectators. In more recent times, artists such as Alexis Hudgins and Lakshmi Luthra have used galleries as TV studios, and in Reverse Cut (2010) they created a working reality TV set, complete with control room and ‘green screen’ interview room operated by professional technicians.63 With the advent of the Internet, the home itself has been transformed into a television studio with individuals ‘directing their own continuing mini-dramas’ from their bedrooms.64 Surrounded by the latest sound and video equipment, they launch their manufactured personas onto an unsuspecting world, often webcasting live from their laptops.

Back in the age of monocultural broadcasting, certain artists reversed the oneway street of television by persuading the public and commercial stations to cede them some precious airtime. A few gained access to professional studios enabling them to explore the potentialities of global communication systems. In Boston, Stan VanDerBeek’s Violence Sonata (1970) was broadcast on two WGBH channels simultaneously making it possible to create a two-screen installation in the home by placing together two televisions tuned respectively to channel 2 and 44. In 1969, John Hopkins and Sue Hall founded TVX, an activist group tackling social issues such as housing. Based in London, the group was also dedicated to ‘the liberation of communications technology for public access’.65 Although the BBC broadcast two of their productions, they drew the line when TVX took mescaline in a studio at Television Centre and created a trippy mix of dancing, debating and narcotic drifting intercut with archive footage. Meanwhile, WDR Cologne broadcast Aldo Tambelini and Otto Piene’s Black Gate Cologne (1968), an elaborate installation featuring a live audience, inflatables and film projections that included news footage of the Kennedy assassination.66 The most famous incursion into the monolith of public broadcasting was the short-lived Television Gallery created by Gerry Schum and Ursula Wevers in 1969, and hosted by the West Berlin station Sender Freies Berlin. In a moment of liberalisation before anxiety about viewing figures stifled arts programming, SFB broadcast a programme of ‘Minimal art for the millions, performance art for viewers at home in front of the box’.67 Land Art (1969) and Identifications (1970) included work by such luminaries of modern art as Gilbert and George, Richard Long, Klaus Rinke and Richard Serra, but it was Dutch artist Jan Dibbets who produced the emblematic work of artists’ television with his elegantly minimal TV as Fireplace (1969). The image beamed into thousands of German homes consisted of nothing but a flickering fire. At a stroke, Dibbets converted domestic televisions back into the hearths they had displaced, encouraging the resumption of conversation, storytelling and communal singing that, in the past, had cemented family unity.

David Hall, TV Interruptions (7 TV Pieces) (1971, Scottish TV). Installation view (2006), at REWIND, Duncan of Jordanstone, UK. Photo: Catherine Elwes.

In concert with the zeitgeist of the avant-garde, Schum and Wevers were committed to facilitating an ‘immaterial form of art consumption’ that ‘reached the largest audience possible’.68 Importantly, this was a practice that bypassed the capitalist art market by operating ‘without an artistic product for sale’69 beyond the moment of transmission. The Television Gallery events, and later broadcasting interventions in the UK, including David Hall’s TV Interruptions (7 TV Pieces) (1971, Scottish TV), may well have created an ‘immaterial form of art’ but viewers could not access the work without the volumetric object, the piece of kit that was increasingly dominating their living rooms. As Jeremy Welsh has argued, video art, whether beamed into the home or removed to the gallery, ‘pulled the trick of encasing the immaterial in a material form … and the individual, material presence of the art object was paradoxically firmly re-established during the video decade’.70 Some artists emphasised the body of the technology by reducing the power of the televisual image. Following Richard Hamilton’s advice that ‘it is best to avoid content on television’,71 they adopted a pared-down minimalism in featureless landscapes (Long, just walking), formal, repetitive gestures (Gilbert and George sitting under a tree) and conceptual conceits (Hall slowly filling the screen with water). This restrained visual language displaced the intense, rehearsed intimacy of television presenters, as well as the ‘needle-like dissection’72 of everyday life that broadcasting presses on our consciousness, distracting us from the political realities of our times.

The refusal of conventional narrative tropes, the degraded, Gothic black-and-white imagery, the cooling of visual information into diverse forms of abstraction put the screen content of analogue video at one remove. Through the sculptural organisation of the material elements of the technology, artists engendered a simultaneous appreciation of the cuboid ‘objectness’ of monitors, surrounded by rivulets of cables. The illusion of recessional space onscreen constantly played against the verifiable, known dimensions of its bulky support; as noted in chapter seven, John Welshman identified this tension as ‘the battlefield between depth and surface’.73 Unmasked and marooned in the glare of aesthetic attention, the television revealed itself as a box of magic tricks of bewildering technological complexity, a cultural signifier (the medium as the message) and a defamiliarised domestic appliance. Both exposed and venerated, the analogue video monitor, thus singled out, invited critical reflection upon the relationship we maintained with mainstream, corporate television, already a significant force in contemporary culture. According to Robert Hughes, television was a medium that produced forms of spectatorship equivalent to ‘passive smoke inhalation’.74 Video artists hoped to offer a cure.

TECHNOLOGICAL TAMPERINGS

Throughout the preceding chapters, video installation has periodically entered the discussion and I have several times rehearsed the now-familiar political critique of mainstream broadcasting, and 1970s artists’ attempts to undermine the power of television with the reflexive revelation of its method of production. This was most actively pursued by artists who tampered with the workings of the technology itself – ‘in order to hate it more properly’ as Nam June Paik often said. In 1963, he wired up a radio to a TV set, which interpreted the sound signal as a point of light on the darkened screen. By turning the volume controls on Paik’s ‘prepared’ set, viewers could expand and contract the light. Point of Light brought spectators into more intimate contact with the workings of the technology, inviting them to adjust the set, but he denied them the resolution of an ‘improved’ picture.

At a psychological level, the disappearing point of light stirs fears associated with abstraction, so frequently adopted by video artists to direct attention to the objectness of the monitor. Julia Kristeva linked abstraction to the Freudian concept of thanatos, the death drive. ‘The work of death,’ she wrote, ‘can be spotted precisely in the dissociation of form itself, when form is distorted, abstracted, disfigured, hollowed out’.75 Paik’s sabotage of individual sets created a sense of the world as we know it falling apart. In the context of the 1960s and 1970s, the malfunctioning of the broadcast signal evoked not only some generalised sense of entropy but also the dreaded television blackout, that apocalyptic moment when radio and television would go dead heralding a nuclear attack that, during the Cold War, seemed imminent.76

In the UK, the strategy of precipitating technological malfunctions, with the audience as accomplice, was more ludic – and offered greater potential for Krauss’s ‘narcissistic’ interaction. Under the title Vidicon Inscriptions (1975), David Hall exploited a basic fault of analogue cameras. When pointed at a bright source of light, the camera was quickly overloaded and the image ‘burned’, leaving a ghostly double of itself permanently etched onto the vidicon tube. The light spots would overlay any subsequent scene to which the camera was exposed, the history of its light-gazing forming a palimpsest of temporal images. In order to exploit this fault, Hall set up a video camera whose lens opened on the approach of a viewer, also triggering a bank of bright lights that ‘exposed’ the scene for a few seconds. The frozen image of the viewer was then routed to a monitor and temporarily superimposed over slowly-fading images of others who had similarly imprinted their likeness in the technology. Some may have appreciated the darker overtones of the work, reading the fugitive nature of the image as a metaphor for the mutability of life. However, many viewers responded with playful and uninhibited preening before their ‘same-time images’.77 It was hard to resist the pleasures of becoming, for a few seconds, the ‘star’ of a broadcast medium that in the early 1970s excluded all but the most privileged.78

THE MONITOR MULTIPLE

The postmodern world-view revolved around the dissolution of the autonomous object, the decentring of the subject and the collapse of the master narratives that sustained teleological notions of scientific and social progress in the earlier part of the twentieth century. Walter Benjamin proclaimed the death by drowning of the art object as it sank into the infinite reduplication of cultural artefacts in both industrial production and photographic reproduction. The cost of the new accessibility to visual culture was the concurrent loss of the object’s irreducible soul, its ‘aura’ and, as a result, ‘the quality of its presence is always depreciated’.79 In a sea of simulacra and production-line clones, the television monitor was similarly interchangeable with any other and the mimetic impressions animating its screen were themselves copies from nature. A reading of televisions as multiple cultural signifiers in an alienated world of illusion was applicable in installations that multiplied TVs into complex sculptural installations. Tricolor Video (1982), Nam June Paik’s most ambitious spectacle of mechanical reproduction, involved 384 upturned matched-monitors. Echoing Andy Warhol’s repeated images of Campbell’s soup tins, Paik’s monitors displayed identical video sequences in groups of four fed by eight tape-decks featuring fast-cut assemblages of found footage including an excerpt from Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. Seen from above at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the carpet of flickering monitors reduced the broadcast footage to abstract colour bursts that together made up the bleu, blanc, rouge of the French flag and, according to Ina Blom, ‘explicitly evoked the ecstatic quality of TV’.80 Paik’s monitors created a play of cultural signifiers, including a metonymic sign for French national identity, conjured from a vortex of optical effects. Beyond the familiar dialogue between televisual illusionism and the sheer bulk of the massed monitors, the work seemed to suggest that devotion to broadcast media was taking over from allegiance to la patrie, or even that a new, nefarious alliance between politics and entertainment was corrupting a medium that Paik was doing his best to highjack for his own ends.

In the more austere environment of the UK, David Hall denied viewers the visual pleasures of the screen by erecting a wall of identical televisions, but with their faces turned away into the angle of a room, leaving the viewer to contemplate the curiously vulnerable bare backs of the sets. The Situation Envisaged: The Rite II (1989) insisted on the phenomenological presence of the machines and by tuning each set to a different off-air channel, Hall reduced the broadcast material to an inchoate cacophony of mediated sounds. Many artists have since multiplied the monitor. As we saw in chapter nine, Angela Bulloch’s video wall Z-Point depicted the climactic moment of the explosion in Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, the image magnified digitally and deployed across a bank of monitors, reducing the filmic material to modular blocks of abstract colour, to the condition of light boxes. Other artists have varied the scale of the monitors. In Inasmuch as It Is Always Already Taking Place (1990), the American Gary Hill assembled an assortment of television sets, stripped them of their casings and devoted their screens to images of fragmented body parts. Hill reiterated the screen/skin analogy and the eternal televisual tease of ‘look but don’t touch’, what Thomas Elsaesser identifies as ‘the never-to-be-satisfied desire for palpability’.81 In Family of Robot: Mother and Father (1986), Nam June Paik combined different sized television sets to construct effigies of a family so enamoured of their TVs that they turned into them. In both cases, the loss of uniformity served to personalise the technology and allowed the work to embody monumentality when taken in as a whole as well as intimacy when smaller monitors were examined close up. Family of Robot: Mother and Father was overlaid with classic Paik irony giving rise to the absurd thought that the small monitors might one day grow up to reach the 12-inch proportions of their elders. In the new millennium, such works take on a vintage gloss of the obsolete, now that the building-block TVs assembled by Paik and Hall have become collectors’ items. The sets also embody the cultural memory of a generation raised on television and memorialise the artists who first imprinted the medium with their own creativity.

David Hall, 1001 TV Sets (End Piece) (1972–2012). Installation view, Ambika P3 gallery, London. Photo: Catherine Elwes.

David Hall’s monumental 1001 TV Sets (End Piece) (1972–2012) has come to symbolise the period of video installation before the monitor ‘box’ was confined to the deep as artists adopted flat screens and ever-higher resolution video projectors. 1001 TV Sets simultaneously celebrated the life and death of analogue television, for so many years the ‘bad object’ of counter-cultural video art as well as its source of inspiration. Staged in the cavernous Ambika 3 gallery in London, Hall installed a sea of 1,001 upturned cathode ray TV sets, irregularly angled and randomly tuned to different terrestrial channels creating a wall of sound that reached the viewer before the installation proper came into view. As the national switchover from analogue to digital broadcasting took place in the UK, staggered across two days in April 2012, the babble of chattering monitors gradually reverted to a field of white noise, the images atomised into ‘an agitated snow of untuned signals’.82 In just a few days, the installation became a junkyard of obsolete TVs, as well as an elegant arrangement oof boxes reminiscent of Donald Judd’s luminous metal sculptures. In Steven Ball’s estimation, the beauty of the work resided in the fact that ‘the medium performed itself’.83 Hall devised an ingenious method of marking the passing of a transmission signal that had come to represent the achievements of analogue video, a brief, forty-year efflorescence now subsumed in the multimedia digital landscape we witness today. The ‘graveyard of analogue televisions’84 represented for Hall a ‘seismic’ cultural shift as much as the transition from analogue to digital. The communal experience of four-channel terrestrial broadcasting, the ‘singular input’ of fireside entertainment has slowly given way to a proliferation of TV stations and the online distribution of multiple, borderless content generated by both commercial and self-funded producers. Ball has characterised the new condition of television as ‘fully remediated in a cross-platform digital afterlife’,85 manifesting on an array of screen-based devices, portable and fixed, accessed inside the home and on the move. Meanwhile the television archive is being picked over by both the corporations and by artists whose own histories are inscribed in the TV anthems of the 1970s and beyond.

A TELEVISION RE−RUN: FAMILY HISTORY

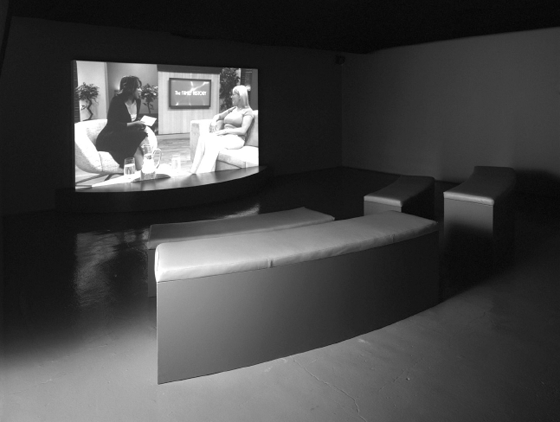

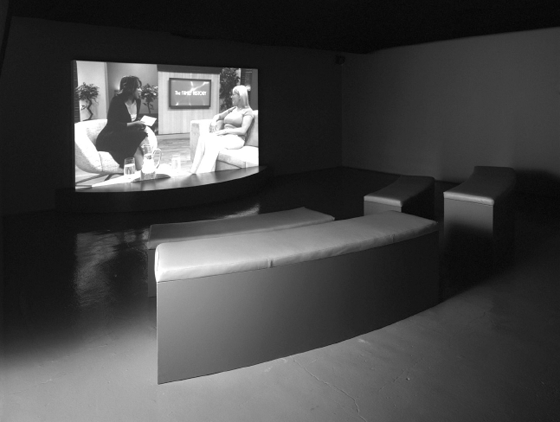

Steven Ball expressed a twinge of nostalgia when he caught the ‘sustained trumpet from the theme tune to Coronation Street’86 chorused by hundreds of Hall’s 1,001 TVs. Gillian Wearing looked for echoes of her own childhood in the development of observational documentaries at the BBC and their portrayal of working-class life. In Family History (2006), Wearing recalled the moments in which, as a small child, she witnessed the first fly-on-the-wall documentary broadcast in the UK. The Family (1974, BBC, producer, Paul Watson), tracked the daily lives of a working-class family living in a council flat in Reading. Maeve Connolly has observed that in these circumstances, the subjects are ‘performing both as themselves and as representatives of marginalised social groups’.87 Wearing identified with the 15-year-old daughter of the house, Heather Wilkins, particularly her sullen rebellion against the perceived restrictions placed on her by her teachers and parents. Wearing chose to locate the restaging of this moment of personal and televisual history in a high-rise in Birmingham, close to where she was living as a child in the 1970s. In one room, a small flat-screen monitor showed a little girl, a stand-in for Wearing, watching the original documentary on a TV placed in a mocked-up sitting room. The Family footage was sometimes raw, the protagonists behaving with none of the knowing artifice of the Kardashians and other contemporary reality TV clans. The Wilkinses did little to conceal the poverty of their surroundings, their lack of a bathroom, the explosive family arguments that sometimes ended in violence. In an adjacent room, Wearing placed a widescreen monitor devoted to an interview between the ‘Queen of crying-time TV’,88 the chat show host Trisha Goddard and Heather Wikins, now in her late forties, cosily confiding in another ersatz ‘sitting room’ set. Heather recounts the impact of the original documentary on the family. They became instant celebrities but were criticised by the press for their ‘bad’ behaviour, and they fared no better with academia, one sociologist describing them as a ‘non-verbal working-class family’.

Gillian Wearing, Family History (2006). Colour video for projection: 35:32 min., 16mm film transferred to DVD for monitor: 2:52 min. Installation view; a high rise flat, Birmingham, UK. Photo: Catherine Elwes. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

Now, thirty years later, Heather has lost her innocence and is more TV savvy. She knows how their ‘not acting’ came across in the final cut; she knows that television ‘reality’ is limited only by the performance skills of the participants; she wishes her 15-year-old self had simply ‘shut up’. Heather has abandoned her working-class accent for the bland ‘estuary English’ that now dominates the amorphous mass of skilled and non-skilled Britons who regard themselves ‘middle class’. She responds to Goddard’s skilful questioning with great care. Exposure to broadcasting in the intervening years has moulded Heather’s persona and, as Maria Walsh remarked, ‘her repertoire of gestures are the invention of television’.89 Heather insists the family was ‘normal, happy’ and they would always ‘protect each other’; sequences reflecting this reality did not make the final cut. The anthropologist Chris Wright has shown how families whose ancestors feature in colonial films view the footage quite differently than do academics. Indigenous communities do not see the history of colonialism, but their own family histories, and they cherish the often only extant visual records of their antecedents. In addition, they interpret the footage in terms of what it might say ‘about the present, the social, political and economic conditions in which they currently exist’.90 The Family now forms part of the history of television documentary but it has a double function. For the Wilkins household, it is entwined in the fabric of their identities; it has put flesh on their memories. ‘It is something we have’, declares Heather; it is ‘the family document’. By updating Heather’s story, Wearing demonstrated how personal narratives interweave with media and social history, and how an individual story can be ‘representative of a larger cultural experience’.91 However, these contingent memories exist in excess of official historical records and Family History also interrogates the role broadcast media still plays in shaping the beliefs we hold about the world beyond the membrane of our homes.

Where earlier videomakers differentiated their practice from the commercial imperatives of the mainstream, in Family History, Wearing engaged with the media in terms of the material she treated and in her collaboration with Goddard. A matrix of celebrity was at play: the once-famous child-star of The Family making a modest comeback, the doyenne of afternoon TV plying her trade and the renowned artist progressing her creative enterprise. These players were all engaged in a process of mutual authentication. The joint venture granted Wearing access to mass audiences and a healthy budget, Goddard acquired the intellectual endorsement of high art and Wilkins finally told her side of the story. The position of Wearing herself was ambiguous. Her art world status was the catalyst for the project, yet she remained a muted presence in the work itself. By calling the shots, she was able to avoid the overexposure to which Wilkins was unwittingly subjected as a teenager; Wearing surveyed her subject from a safe distance.

Gillian Wearing, Family History (2006). Colour video for projection: 35:32 min., 16mm film transferred to DVD for monitor: 2:52 min. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London. © the artist.

THE POST−EVERYTHING ERA

Television and cinema history are beginning to converge. The generation of the 1990s, including Douglas Gordon, Candice Breitz and Gillian Wearing, differed from the previous generation in that they experienced the Hollywood back catalogue ‘in bed … through the conduit of television’,92 and indeed interactively via the VCR. Nowadays, the canon of mainstream moving image culture is easily accessed online, via any digital device and, as Erika Balsom has remarked, these private viewings are rendered ‘gigantic’ when returned to the public space of the gallery.93 Maeve Connolly has identified a new generation of artists who, like Wearing, ‘explore interconnections between familial and national histories involving material drawn from broadcast archives’,94 and who reposition their findings in the arena of art. She cites in particular the work the Finnish artist Laura Horelli whose mother worked as a presenter on children’s television in the 1980s. In contrast to comparable practices from the 1960s to the 1980s, the ‘televisual turn’, argues Connolly, is predicated not so much on a critique of television as ‘an object of reform’95 but on the excavation of television and its archives as a creative resource. The TV studio is adopted as a ‘space of performance’96 and of experimentation, and provides an opportunity for collective working practices. Contemporary artists such as Nathaniel Mellors, Ryan Trecartin & Lizzie Fitch, Michele Dignan and Superflex, are now employing professional TV technicians and performers and embracing mainstream production values.97 Nevertheless, the social engagement of the avant-garde still survives; Superflex, who work with tenant groups, have indicated a political agenda when they expressed their frustration that their project tenantspin (2001–2) failed to prevent the demolition of the residents’ homes.98

While some artists embrace the glossy surface of hi-res contemporary television, others such as Stefanos Tsivopoulos return nostalgically to the cumbersome analogue technologies of early television. Gerard Byrne memorialises television by adopting outmoded analogue video effects, while in 19:30 (2010) Aleksandra Domanović relives childhood memories of war-time news broadcasts. She remixes Bosnian and Croatian television news idents that stylistically recall the 1980s Scratch video movement in the UK, which may in turn have influenced the development of television graphics.

Thomas Elsaesser has argued that media archaeology offers artists and audiences an opportunity to discover ‘the repressed potentialities’ of the cinema and television archive, and opines that a ‘more open-ended past’ might then lead to a ‘more open-ended future’ for moving image culture.99 Nevertheless, it would be a mistake for artists to suspend criticality and ignore the normative pressure exerted by television today (X-Factor, the Kardashians, Jeremy Kyle), nor should they overlook the mirroring of state power and the framing of world events in what David Joselit calls the ‘locked-down terrain of television’.100 The co-opting of artists’ creative strategies in television’s own navel gazing should also be an area of concern.101 At the 2014 Screen conference in Glasgow, Lisa Akervall articulated a notion of ‘the redistribution of the critical’ in which artists attempt to reveal what are naturalised practices within broadcasting and Internet culture, working from the inside on the basis that it is no longer possible to occupy an outsider position. As many artists discovered in the 1960s and 1970s, this method is always already compromised and only rigorous attention to the workings of televisual language will avoid simply reproducing the object of critique. Whatever strategies artists adopt in the future, the indications are that broadcast culture and, as the recent spate of pastiches and re-enactments attest, historical analogue video art will continue to provide creative capital to reinvest in the ‘theatres of TV’102 that contemporary galleries and museums have latterly become.

NOTES

1 John Ellis’s term used throughout Seeing Things: Television in the Age of Uncertainty (2000). London: I.B. Tauris.

2 David Hall (1975) ‘Video Art and the Video Show’, Film Video Extra, 4, p. 2.

4 See John Ellis (2000), op. cit.; also Lynn Spigel (1992) Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

5 Maeve Connolly speaking at LUX, London, 17 May 2014.

6 See Maeve Connolly (2014) TV Museum: Contemporary Art and the Age of Television. Bristol: Intellect; ‘Human interest stories, banter between co-anchors and changes in vocal delivery including the use of an energetic, upbeat tone’ was found to have a positive impact on ratings, p. 134.

7 David Hendy (2010) The Cultivated Mind. BBC Radio 4, first broadcast 18 June.

8 Peggy Gale (1995) ‘Video has Captured our Imagination’, in Peggy Gale and Lisa Steele (eds) Video re/View. Toronto: Art Metropole and Vtape, p. 118.

9 Chantal Ackerman in conversation with Michael Newman, Tate Modern, London, March 2002.

10 David Hendy (2010), op. cit.

12 In Bad Science (2009, Harper Perennial), Ben Goldacre asserted that where they formally dealt with doctors, pharmaceutical companies in America have increased their spending on direct-to-consumer advertising, because patients then petition their GPs for the drugs, thereby increasing sales.

13 Quotes are from the text of the work itself.

14 David A. Ross in conversation with Peter Campus and Douglas Gordon, 17 April 2008, Tate Modern, London.

15 In the 1970s, analogue monitors generally displayed only locally inputted video signals from a camera or video player. Monitors were soon developed that could both receive broadcast signals and display footage from an external device.

16 Steve Hawley quoted in Catherine Elwes (2005a) Video Art: A Guided Tour. London: I.B. Tauris, p. 141.

17 Dé-collage was derived from the torn posters of the French affichistes, now applied to other consumer objects. See John G. Hanhardt (1990) ‘De-colage/Collage: Notes Towards a Reexamination of the Origins of Video Art’, in Doug Hall and Sally Jo Fifer (eds) Illuminating Video: An Essential Guide to Video Art. New York: Aperture/BAVC, pp. 71–9.

18 The destruction of television sets developed into something of a genre, exemplified by Ant Farm in San Francisco, who in Media Burn (1975) drove a Cadillac through a wall of burning TVs.

19 See Marshall McLuhan (1964) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

20 Catherine Russell (2000) ‘Autoethnography: Journeys of the Self’, in Steve Reinke and Tom Taylor (eds) Lux: A Decade of Artists’ Film & Video. Toronto: Pleasure Dome/YYZ Books, p. 99.

21 David Hendy,The Ethereal Mind (2010), BBC Radio 4, first broadcast 14 June.

22 Colin Perry (2011–12) ‘TV Makeover’, Art Monthly, 352, p. 13.

23 Jonathan Crary, in his foreword to Nicolas de Oliveira, with Nicola Oxley and Michael Petry (2003) Installation Art in the New Millennium: The Empire of the Senses. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 6–11. A similar view is expressed in Theodor Adorno’s 1954 essay, ‘How to Look at Television’ in J.M. Bernstein (ed.), The Culture Industry (2001). New York: Routledge, pp. 158–77.

24 For example, in 1984 Mike Stubbs, Roland Denning and Mike Rushton compiled the Miner’s Tapes from their own actuality footage inluding interviews with strikers and their families. The tapes were edited at London Video Arts, an artist-run co-operative, and distributed by the National Union of Mineworkers.

25 Some artists’ tapes were aired on television, predominantly cable TV in America, but in the UK, Channel 4 briefly championed experimental video. See Rod Stoneman (1996) ‘Incursions and Inclusions: The Avant-Garde on Channel 4, 1983–93’, in Michael O’Pray (ed.) The British Avant-Garde Film, 1926 to 1995. London: The Arts Council of England/John Libbey Media, pp. 285–96.

26 Hans-Ulrich Obrist’s term quoted in Kate Mondloch (2010) Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, p.43.

27 Dara Birnbaum quoted in Chris Meigh-Andrews (2006) A History of Video Art: The Development of Form and Function. Oxford: Berg, p. 170. Birnbaum worked in post-production for an American television company where, in 1979, she ‘borrowed’ broadcast footage for her ‘technological transformations’.

29 Maeve Connolly (2014), op. cit. p. 253.

30 Dara Birnbaum quoted in Chris Meigh-Andrews (2006), op. cit.

31 Kathleen Pirrie Adams (1999) ‘Lady in the Lake: fluid forms of self in performance video’, Promise catalogue, Toronto, YYZ.

32 Birnbaum repeat-edits Wonder Woman spinning as she undergoes her transformation from ordinary citizen into superheroine. See Technology Tranformation: Wonder Woman (1979). Available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6xZOUXNyQg (accessed 16 April 2014).

33 I am borrowing a term Miwon Kwon used in relation to landscape in which a place is re-invested with specific human significance through sustained occupation and social practices; see Miwon Kwon (1997) ‘One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity’, October, 80, pp. 85–110.

34 Colin Perry’s term in ‘TV Makeover’ (2011–12), op. cit., p. 11.

35 John Baldessari quoted by Isaac Julien, Guide to Artists’ Filmmaking, BBC Radio 4, 18 January 2011.

36 For me, the simplicity of the technology was key. I had no need of a light meter, which I did not understand, and I could work alone. However, the weight of the ‘portable’ portapak was a problem. Inspired by the heroic image of Bill Viola facing the desert with the camera hoisted onto one shoulder and the portapak slung across the other, I made Spring (1988) in which, with the same equipment, I attempted to follow a young girl leading me through a wood. The pauses in my journey correspond to the moments when I can no longer carry the equipment, and have to stop and catch my breath.

37 Catherine Russell (2000), op. cit., p. 102.

38 I am grateful to Catherine Long for drawing my attention to Pindell’s video.

39 Patricia Mellancamp (1990) Indiscretions: Avant-Garde Film, Video & Feminism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, p. 129.

40 Mary Russo quoted by Patricia Mellancamp, ibid.

41 For further discussion of the uses of video in liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s, see Catherine Elwes (2005a), op. cit.

43 See Thomas Elsaesser (2006) ‘Discipline Through Diegesis: The Rube Film Between “Attractions” and “Narrative Integration”’, in Wanda Strauven (ed.) The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 205–23.

45 See Stuart Marshall (1975) ‘Video Art, the imaginary and the parole vide’, Studio International, May/June, pp. 243–7.

46 See Rosalind Krauss (1976) ‘Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism’, October, 1, p. 53.

47 Anne M. Wagner (2000) ‘Performance, Video, and the Rhetoric of Presence’, October, 91, p. 68. I am grateful to Kate Pelling for alerting me to this reference.

48 Rosalind Krauss (1976), op. cit., p. 59.

49 See Michel Foucault (1975) Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la Prison. Paris: Gallimard. Foucault discusses Jeremy Bentham’s prison design in which a single warder could survey, unseen, a large number of cells fanning out from a central viewing station. He uses the panopticon as a metaphor for mechanisms of technological and state power.

50 From my notes on Lisa Akervall’s paper ‘Videoart’s Inverted Panopticon: A Critical Aesthetics of Postcinematic Subjectivity’, delivered at the Screen conference, Glasgow, June 2014.

53 When I was a student at the Slade in the late 1970s, I attended a re-enactment of Graham’s video performance staged by a duo whose name now escapes me. When they launched into their meticulous descriptions of the art rabble who had gathered for the event, I cowered behind a large sculptor and prayed that I would be overlooked. ‘There is Cate Cary-Elwes’, quipped one of the likely lads, ‘she’s pretty intimidating when you first meet her’, he continued, prefacing a forensic demolition of my character. I was devastated.

54 David Hall (1975), op. cit., p. 2.

55 Maria Sturken (1999) ‘Reimagining the Archive’, in Seeing Time: Selections from the Pamela & Richard Kramlich Collection of Media Art, exhibition catalogue, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, p. 38.

56 Anthony McCall, speaking at the Shoot, Shoot, Shoot, conference, Tate Modern, London, May 2002.

57 David A. Ross (1999) ‘Seeing in Real Time’, in Seeing Time: Selections from the Pamela & Richard Kramlich Collection of Media Art (1999), exhibition catalogue, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, p. 10.

58 See Catherine Fowler (2013) ‘Once more with feeling: Performing the self in the work of Gillian Wearing, Kutlug Ataman and Phil Collins’, MIRAJ, 2:1, pp. 10–24.

59 A new adaptation of In Two Minds entitled Past and Future Versions features the artist talking to a heavily made up Atherton impersonating an even older self. This phase of the work, he says, allows him ‘to create fictional art works, make public my career aspirations, and imagine how my personal life might pan out’. REWIND catalogue, Dundee Contemporary Arts (2006).

60 A term used by Slavoj Žižek speaking at Tate Britain on 25 May 2006.

61 Atherton and Graham represent a generation whose presence in the work was central to its investigation of perception and identity. A new generation has adopted a practice of what Claire Bishop has ordained ‘delegated performance’ in which ‘collaborators’ perform as surrogates for the artist (again, see Catherine Fowler (2013), op. cit.). My focus here is on early examples of artists who worked live with video.

62 For a more in-depth discussion of the domestic origins of video installation, see Catherine Elwes (2011) ‘The Domestic Spaces of Video Installation’, in A. L. Rees, Duncan White, Steven Ball and David Curtis (eds) Expanded Cinema: Art, Performance, Film. London: Tate, pp. 276–87.

63 Spectators were walked through the space in small groups while the ‘cast’ and crew worked around them. In the control room, visitors could listen in to subjects who were wired with microphones for 24 hours a day over three days.

64 J. G. Ballard quoted by Nicolas de Oliveira (2003) Installation Art in the New Millennium. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 22. He continues: ‘Reality is turning into a home movie, in which an infanticized version of ourselves runs across a garden of artificial grass.’

65 John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins quoted in Chris Meigh-Andrews ([2006] 2014, 2nd edn), op. cit., p. 56.

66 Where British artists made inroads into public service broadcasting, principally Channel 4, Americans found a receptive context for their work in the nationwide network of cable stations such as KQED in San Francisco and WGBH in Boston.

68 Barbara Hess (2005) ‘Our machines now are ready to shoot’, Dispatch, 114, Norwich Art Gallery, unpaginated.

69 Gerry Schum quoted in Barbara Hess, ibid.

70 Jeremy Welsh (1996) ‘One Nation Under a Will (of Iron), or: The Shiny Toys of Thatcher’s Children’, in Julia Knight (ed.) Diverse Practices: A Critical Reader on British Video Art. Luton: Luton Press/Arts Council of England, p. 160.

72 David Hendy, The Fallible Mind (2010), BBC Radio 4, first broadcast 17 June.

73 John Welshman speaking about Tony Oursler at the Drawn Encounters, Complex Identities conference, The British School at Rome, September 2008.

74 Robert Hughes quoted by David Hendy, as above.

75 Julia Kristeva ([1987] 1997) ‘Black Sun’, in The Portable Kristeva. New York: Columbia University Press, p. 27.

76 During the industrial disputes in the 1970s and early 1980s, technicians’ and journalists’ unions periodically pulled the plug on broadcasting. However, the screens did not go completely blank, programmes were replaced by a text message apologising for the break in transmission.

77 David Hall (1975), op. cit., p. 2.

78 A recent attempt to recreate this work for the ‘REWIND’ project in Dundee had to be abandoned because the original cameras had lost their phosphorescent coatings through age and contemporary cameras no longer register an electronic after image.

80 Ina Blom (2007) On the Style Site: Art, Sociality and Media Culture. New York: Sternberg Press, p. 85.

81 Thomas Elsaesser (2006), op. cit., p. 214.

82 Steven Ball (2013) ‘The end of television: David Hall’s 1001 TV Sets (End Piece)’, MIRAJ, 2: 1, p. 136.

84 David Hall quoted in Emma Barnett (2012) ‘Artist marks digital switchover with ‘‘TV Graveyard’’’, The Telegraph, 16 March.

85 Steven Ball (2013), op. cit.

87 Maeve Connolly (2014), op. cit., p. 108.

88 Stuart Jeffries (2006) ‘Get Real’, The Guardian, 6 July.

89 Maria Walsh (2006) ‘Gillian Wearing’, Art Monthly, 300, p. 26.

90 Chris Wright speaking at the Documentary & Ethnographic Avant-Garde seminar, AHRC Artists Moving Image Research Network, LCC, 26 January 2012.

91 Maeve Connolly (2014), op. cit., p. 147. Family History intersects with a famous social document generated by television itself. Michael Apted’s 7 Up series. Begun in 1964, it followed the lives of fourteen girls and boys from a range of social backgrounds, culminating most recently in 56 Up when they were well into middle age. The programme’s principal objective was to demonstrate the effects on individuals of the British class system.

93 Erika Balsom (2013a) Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 142.

94 Maeve Connolly (2013) ‘Television, outmoded technologies, and the work of Lana Lin’, MIRAJ, 2: 2, p. 286.

95 Maeve Connolly (2014), op. cit., p. 21.

97 Some also work with unpaid non-professional performers, whose status in the work gives rise to questions about the employment hierarchies dominating the television industry and how these inequalities might translate into an art context.

98 Maeve Connolly (2014), op. cit. p. 113.

99 Thomas Elsaesser, ‘The Poetics and Politics of Obsolescence’, paper delivered at AHRC Artists Moving Image Research Network, LCC, 8 June 2014.

100 David Joselit quoted by Maeve Connolly (2014), op. cit., p. 55. Connolly later quotes Laurie Ouelette’s research into reality TV; he interviews a judge who blames soap operas for ‘legitimising the most back-stabbing, low down, slime-ball behaviour’, p. 112.

101 See Colin Perry (2011–12), op. cit.

102 Maeve Connolly (2014), op. cit., p. 47.