(Expanded cinema) radically alters the spatial discreteness of the audience vis-à-vis the screen and the projector by manipulating the projection facilities in a manner which elevates their role to that of the performance itself…

Deke Dusinberre, 1975

TANGLED ROOTS

The American critic Gene Youngblood is credited with coining the term ‘expanded cinema’ in his eponymous book written in 1970.1 Youngblood interpreted the new practice as a symptom of the impact of television and modern communication systems on the creative lives and individual psyches of artists growing up in the burgeoning ‘intermedia’ environment, which, he declared ‘is our environment’.2 In spite of Youngblood’s influential text, there is no consensus on a precise nomenclature for this multivalent cinematic art; Peter Kubelka referred to ‘invisible film’, Carolee Schneemann favoured ‘cinematic theatre’ and Stan VanDerBeek, ‘the cultural intercom’. Some now proclaim ‘situated/locational film’ or ‘artists’ cinema’ as the collective term for an opening out of the filmic encounter. The young American media performer Jacolby Satterwhite describes himself in flamboyant terms as an ‘extended frame, video installation performance diva’, neatly encapsulating the hybridisation of art processes and disciplines. However, Youngblood’s ‘expanded cinema’ is the commonly accepted term, one that historically denotes the condition of what VALIE EXPORT called ‘liberated film’, a practice that develops the making and viewing of film beyond the conventional screen-to-seating configuration of movie theatres and multiplexes.3 The impulse to liberate both film and its audiences manifest in Europe, America and Japan, notably at the Workshop of the Film Form in Lódz and the KwieKulik’s ‘Open Form’ film collective in Poland; in the work of José Val del Omar in Spain; that of EXPORT, Willem and Birgit Hein and Peter Weibel in Germany; and the Gutai group in Japan.4 Expanded cinema turns attention away from conventional narrative, and what Malcolm Le Grice called ‘the single line of access to a story’5 and refocuses on the drama of the apparatus of film: the projector, the screen(s), the filmstrip, the projection beam and the ‘primary experience’, the ‘present tense’6 of the unique, one-off cinematic event. These stagings of film often unrolled into several iterations of the same work. In his six-screen installation After Leonardo (1973), Le Grice included the dates of all its previous exhibitions, charting the work’s material history. Like Le Grice, William Raban extended the temporality of his expanded works, and in 2’ 45” (1973) he layered recordings of successive film performances in which he stood before a projection, stated the date and time, and announced ‘a camera is filming the audience watching yesterday’s audience watching the blank screen. Sounds of the projection and the audience’s responses are being recorded.’ The audience spied on earlier audiences, aware that they were themselves becoming fodder for the next in a ‘recursive time-lapse containing the entire history of the event’.7 Both Raban and Le Grice have also highlighted the importance of improvisation and chance in each iteration of an expanded work, which Le Grice classifies as open-ended, unfinished, a ‘non definitive’ practice.8 The temporality of the work shifted from the narrative compressions and elisions that enable a biopic to tell the story of a life in an hour or so, to a consideration of the time it takes a film to pass through the projector witnessed by spectators held in the same parcel of time. These attributes align expanded cinema with the broader materialist concerns of avant-garde film and video as they emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. In common with many experimental filmmakers, proponents of expanded cinema were committed to eliciting the participation of the viewer in the space of projection, both viewer and environment being regarded as material components of the work. Further, expanded cinema explored the relationship of film to what Duncan White describes as ‘the environment of perception’,9 testing the limits of cognition by seeking to establish the minimum legibility of sound and picture, the degree of semantic coherence required for the projection to be read as a film.

William Raban, 2’ 45” (1973). Courtesy of the artist.

If, as Siegfried Kracauer suggested, ‘film images affect primarily the spectator’s senses, engaging him physiologically before he is in a position to respond intellectually’,10 then they do so predominantly by means of two senses: vision and hearing. Expanded cinema, fundamentally committed to galvanising the critical faculties of an audience did so, paradoxically, by mobilising the whole gamut of sense perceptions, by stimulating touch, smell, spatial awareness and even taste. This was achieved through the deployment of film gadgetry generating rhythmic sound, both mechanically produced and simulated; miscellaneous objects and built environments; live performers, animals, food, smoke or the artist in person all representing points of concentrated meaning in a spatialised, temporal ensemble of artefacts collectively coded as art. Whether great or small, any constellation of elements enlisted for an expanded cinema event acts in correspondence with the pivotal filmic images onscreen(s), both live (in the case of video), and pre-recorded. Where there is a difference in presentation between expanded cinema in the counter-cultural era and contemporary moving image installation, it is largely a question of emphasis. Nowadays an installation is less likely to focus on the specificities of a given medium and its apparatus, and artists tend towards a catholic use of materials, picking and choosing their medium according to the requirements of the project. Although a hard core of artists still maintain loyalty to the now-obsolete charms of celluloid film – possibly, as Colin Perry suggested, because they embody ‘subjective desire, nostalgia and memory’11 – contemporary artists generally default to the digital in terms of moving image because of its convenience and the high-definition resolution that can now be achieved.12 At its inception, however, the technology of expanded cinema, its mechanical armature was indeed critical. Commentators, notably Chrissie Iles, have stressed the sculptural dimension of the apparatus, and here the artisanal, hands-on, serendipitous aspects of working directly with celluloid find happy historical bedfellows in the modernist wielders of saws, chisels and palette knives and, in the case of Gustav Metzger’s ‘auto-destructive’ art, acid, with which he attacked the illusionism of pictures on stretched nylon canvas. The artist was now engaged in a form of hand-to-hand combat with the traditional materials and processes of both painting and film.

Other academics have highlighted those characteristics that expanded cinema holds in common with classic cinema itself: the time-base of the projected image, the schedule of screenings, the dependence on concentrated points of artificial light in a darkened, cloistered space, the generation and control of sound, and, as Maeve Connolly has explored in depth, the social arena these circumstances create.13 Even the viewing conditions ascribed to both museum and cinema have begun to merge, not least because of the frequent transformation of galleries into temporary movie houses where the viewer can choose to be sedentary as in a traditional theatre or move in and out of the space at will as is sanctioned in a gallery environment.

Across the years, a minimalist aesthetic regularly attends works in expanded cinema and Chrissie Iles has observed that artists have expanded film ‘precisely by contracting it’,14 by reducing it to its constituent parts and exploring their inherent qualities. As we have seen, the contraction also occurs through the expulsion or disfiguration of traditional forms of representation and narrative arcs. For some practitioners of the genre, the objective is to reduce the image to a function of the apparatus that gives it life with no reference to realities beyond the present event of the film screening. The expansion-via-contraction of film was thus achieved in the counter-cultural era by means of forensic, though often tender, dissection of its components and processes before a live audience, isolating mechanisms whose interdependence have defined mainstream cinema since the last century. This structural vivisection enables us to call on different manifestations of expanded cinema to draw up a provisional anatomy of film itself.

THE FILMSTRIP: AUTO DESTRUCTIVE FILM

In our consideration of film as film, we saw how artists made physical interventions in the filmstrip, scratching, puncturing and painting, and, in projection, rendering those traces as flashes of light in complex, animated abstract patterns. However, a group of artists expanded the temporal envelope of the film by altering the physical make up of the celluloid over long periods of time. In Standing Film/Moving Film (1968), the German artist Werner Nekes created what he called one-frame film performances. Like so many experimental works these ‘films’ came about accidentally. Nekes stored some footage in a damp cellar, and, over several months, the filmstrips became contaminated with mould. When he extracted a single frame of the film and placed it in a projector, as the lamp came to life, ‘the microbes in or on the celluloid started moving because of the heat’.15 Nekes was stretching the parameters of what constitutes a film by asking whether ‘a single frame could be a film’.16 In 2014, Patrick Tarrant proposed the concept of ‘magic materialism’ in relation to ‘microbial’ work of this kind.17 In his discussion of Ben Rivers’s Two Years at Sea (2011), Tarrant observed how chemical blemishes on the film strip, what he called the ‘chemical landscape’ took on narrative significance. Rivers’s film is about a rural recluse, Jake Williams, and the stains on the celluloid, when projected, become mountains looming over the figure of Williams walking in the distance. Where Rivers enacted a ‘merging of the real and representation’,18 Nekes was more concerned to demonstrate the material death of film by dramatising the sinister work of the microbes on the time-limited material of celluloid. When the results of their chemical labour are blown up to the cinematic proportions of a snuff movie, an equally mortal audience is given pause for thought.

Ben Rivers, Two Years at Sea (2011). Courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry Gallery. Funded by Arts Council England through FLAMIN.

Other artists advanced the necrotic body/film analogy underpinned by our ‘shared organic existence’ by making films over ‘long spaces of time’19 with a natural life that could theoretically extend to years, in the case of Tony Conrad’s Yellow Movie (1973) to something over four decades. These were barely films, merely painted ‘movie frames’ using cheap emulsion that gradually yellowed when exposed to natural light. Conrad also created ‘cameraless’ films made up of unprojectable celluloid fragments that he subjected to pickling, baking or hammer attack as a way to escape the ‘inextricable bind to the commercial process[es]’ of the film industry.20 VALIE EXPORT and Peter Weibel separated the filmstrip from the camera and projector, and indeed dispensed with celluloid altogether in their Instant Film (1968). Transparent PVC sheets were offered to spectators with which to make their own films by ‘hanging [them] on the wall, in front of different coloured backgrounds’,21 or with their own cigarette-burned apertures, create a window on their world. The conceptual stretch in these works is almost at breaking point, and as Conrad reminds us, ‘movies always take place in your imagination’.22 This has led Genevieve Yue to conclude that although apparently concerned with decay, artists like Conrad and Nekes have made permanent works at a conceptual level.23 Yue quotes Peter Kubelka who declared: ‘With this film, I have done something which will survive the whole of film history because it is repeatable by anyone. It is written down in a script, it is beyond decay’.24 Yue identifies in structural works and, in this context, expanded cinematic projects what she calls ‘two diametric strains’ in which the work both ‘endures as a concept … but in material form it inevitably decays’.25

Although the radical impulse to oppose both the art market and the film industry was always strong in these works – the ‘films’ remained uncollectable – a macabre, fin de siècle preoccupation with the material disintegration of film seemed to predominate in the 1960s. A similar aesthetic resurfaced at the end of the 1990s in David Gatten’s What the Water Said, nos. 1–3 (1997). The artist threw unprocessed film into the surf and let the sea create the film as a combination of marks made on impact with the solid matter of sand, rocks and living creatures, and the chemical interaction of seawater with celluloid.26 The resulting pictorial symphony to the sea created an elegiac double lament for both the dissolution of analogue film, and the slow death of marine life in our oceans. We will return to the topic of obsolescence and cinematic necrophilia, but where Conrad, Nekes and Gatten emphasised the material instability of the filmstrip, and by extension, the body and latterly, the environment, other artists concentrated on the moment of projection, and the apparatus that could magically bring film to life – but only in darkness.

VISION: DARKNESS

Light … like air … tends to go unnoticed unless it suddenly dies.

Nicky Hamlyn, 2003

Expanded cinema is an event that transforms the space through the changing effects of projected light and is dependent for its impact on both darkness and a reliable source of electricity to power the projector and sound system. The crucial condition for the existence of the shaft of projected light is thus the absence of natural light. Should daylight or any other source of artificial light seep into the darkened space, the projection would be compromised. In Flat Prune (1965), the theatre-trained American Robert Whitman lowered a bare light bulb in front of a film projection where it both bleached out the image and became an element for live performers to manipulate, effectively bringing the lighting technicians onto the stage.

At around the same time, Malcolm Le Grice in the UK also dramatised the fragility of the projection beam and thus the cinematic image by intermittently switching on a bare light bulb hanging in front of the screen. Castle One (1966) consisted of a montage of found footage depicting demonstrations and political speeches intercut with shots of an identical light bulb to the one threatening the screen in the projection space. When the material bulb lit up and obliterated the filmic image, it abruptly wrenched its audience from the immersive drama onscreen, creating a momentary disorientation like the confusion experienced when waking suddenly from a dream. Torn from the comfort and anonymity of voyeuristic immersion in the illusory universe of the screen, viewers became ‘self-spectators’,27 engaged in a form of mutual objectification.28 Where the light in Flat Prune drew attention to the onstage performers, in Castle One the light bulb stayed on long enough for normal social interactions to resume among audience members, only for the conversations to be abruptly cut short when the bulb was once again extinguished and the ‘other’ filmic reality resumed its dominance. The unceremonious lurching between the two perceptual states not only confronted viewers with the physical reality of the mechanisms of film illusionism, but also anticipated by several decades Martin Creed’s now infamous installation Lights Going On and Off at the Tate Gallery in 2001, a work to which we will return.29

Le Grice also drew attention to the social conditions of traditional cinema, in which the dimmed lighting of the picture palace brought with it both promise and the occasional hazard lurking in the stalls – as a boy, Rupert Everett was admonished, ‘don’t sit too close to Mr. Barnard from Millens & Dawson, there’s a good boy’.30 The cover of darkness allowed courting couples to indulge in behaviours not sanctioned in daylight – this being particularly so in the 1940s and 1950s and even into the 1960s when young people had few opportunities of being alone before marriage. Overall, the darkness of the cinema auditorium is customarily experienced as benign.31 In Moby Dick, Herman Melville suggested that it is only when a man’s ‘eyes be closed’ that he ‘can ever feel his own identity aright … as if darkness were indeed the proper element of our essences’.32 If we go to the cinema to discover, in the dark, our human essences then, according to Eric de Bruyn, cinema does its best to facilitate that quest and makes us welcome. Quoting Peter Kubelka he contends that cinema creates the pleasurable ‘feeling of being in the dark mother’s womb from which one would then be born into another world, the world of the film’.33 Le Grice was intent on disrupting precisely that agreeable rebirth, the routine by which viewers are eased into the imaginative space of a mainstream movie – the popcorn, the curtains rising, the trailers and the opening credits – and obligingly escorted back into the light of day at the end via the dénouement, the credits, and, way back when, the national anthem.34 Beyond its self-reflexive lessons in the duplicity of illusionism, Castle One played on the comfort we derive from the enveloping darkness of cinema, the nocturnal descent into Plato’s cave of shadows, the transition to a state of enchantment that is the precondition of filmic experience. As Raymond Bellour remarked: ‘I have never studied or written about a film that does not stem from what happened to me in the dark. This is the singular effect of cinema.’35

There is always sufficient light in a cinema for the contours of the auditorium to remain legible, for people to keep their bearings, and come and go without fear of injury. This is not simply due to the rows of small floor-level lights that lead spectators to the exit, but from the film itself, the brightness of the image irradiating the theatre, and the changes of light and dark throughout the film can be seen flickering across the faces of the spectators. By contrast, it is increasingly common for moving image installations to require visitors to push aside heavy felt blackout curtains and enter a space only to be plunged into a sightless, debilitating blackness. Spectators often have to grope their way along a light trap corridor before they can discover the work itself. Before night vision kicks in and with all points of visual reference extinguished, the visitor is profoundly disoriented and it can take up to thirty minutes for her eyes to fully adapt to the new crepuscular conditions. Although, rationally, we know that we have entered an artwork, the instinctive, embodied interpretation of the lights going out is that we have gone blind, or the apocalypse is upon us. Total darkness spells dissolution and death in the human imagination and without visual cues to aid orientation and locate others of our kind, we simply feel that we are alone in the dark.36 Of the innumerable installations that engulf the viewer in darkness, In Camera (1999) by Smith and Stewart most effectively inspired in me the terror of losing my sight. Out of total blackness, a single, monochrome monitor set high on a wall suddenly comes to life and casts a beacon of light into the space. The image on the monitor (with a nod to Laurie Anderson) represents a view from the recess of a mouth where a tiny camera has been placed, looking out. Only when the mouth is open does an image appear. When the mouth clamps shut, the gallery is once again enveloped in darkness. Smith and Stewart created an experience that instilled fear but also confused the body clock, the internal timekeeper that uses light to distinguish night from day, and to regulate sleeping and waking. Coming away from the work into the light gave some small sense of the release prisoners must feel after a period of light deprivation and solitary confinement. As Nicky Hamlyn observed, we recognise the significance of light only when ‘it suddenly dies’.

Darkness, then, is the pre-condition of cinema. According to Lucy Reynolds, darkness rather than light is ‘the subject of cinema’.37 Without it, no projected image will maintain a retinal presence. Blackout may instil in the spectator the comforts of the maternal womb, from where narrative film and its psychological and sensory pleasures may be indulged, particularly in the half-light of cinema spaces; it may also represent what Reynolds has dubbed, ‘the territory of fear’.38 When the blackness is total, it produces disorientation and simulates the loss of sight, the curtailment of liberty or even ‘the dying of the light’, the extinction of life itself.39

THE SPACE OF PROJECTION: LIGHT

The moment of projection … refers to nothing beyond real time. It contains no illusion. It is a primary experience, not a secondary one.

Anthony McCall, 2006

British expanded cinema artists in the 1960s and 1970s were principally concerned with the sculptural and phenomenological properties of the projection beam and the spatial relationship between the projector, the shaft of light and the surface it strikes to create an image. In his emblematic Line Describing a Cone (1973), Anthony McCall placed the light beam at the centre of the work, in an attempt to define ‘the moment of projection’. Although initially presented in a cinema, the work was later reconstituted as a gallery installation devoid of seating. A single projector mounted on a plinth was accompanied by the mechanical clatter and purr of its moving parts, for older viewers stirring memories of nights at the movies. Once the machine flickered into life, a thin beam pierced the darkness tracing a line of light that ended when it struck the opposing wall. However, the screen-image was not where the ‘film’ took place. Over the course of thirty minutes, the sliver of light slowly grew until it described a perfect cone, a volumetric entity with the projector at its apex and point of origin. In the 1970s, films enjoyed a fugitive pre-existence in the turbulence of cigarette smoke and dust particles animating the projection beam. McCall recreated the rendering of light as mass, initially with the aid of his friends’ reckless smoking, and later, by pumping dry ice into the gallery. Where the cinema viewer previously sat in a fixed position, McCall now adapted the work for an ambulatory spectator and as the artist commented, his ‘solid light films’ could not be ‘fully experienced by a stationary spectator’.40 The work was ‘made’ by the gallery goer who discovered changing perspectives while physically moving through the beam. A more recent work, Between You and I (2006), staged in a church in London, featured two beams of light projected downwards from a great height creating ‘vertical chambers to enter and leave’.41 The beams followed the evolution of a circle and a straight line that together constituted McCall’s ‘total vocabulary’.42 The projectors, now digital, no longer made their presence felt through their familiar clatter but were swallowed up by the darkness above, their mechanisms inaudible. With no discernible source of the light, it was now possible to replace a materialist reading with a more spiritual one. The ascension of the projectors into what I took to be the church tower, reiterated the verticality of the architecture and the Christian belief in a celestial deity. Even as a lapsed Catholic, I found myself unwilling to speak above a whisper. McCall has observed how the fragility of his work instils in visitors a rare courtesy; viewers avoid obscuring the beam from others and when I saw the work in the context of a private view, the interpersonal elements, the breathless conversations in the semi-darkness returned the work to the shared raptures of a pleasure palace.

Anthony McCall, Between You and I (2006). Installation view, Peer/The Round Chapel, Hackney, London. Courtesy of the artist.

Many spectators explored the curious experience of passing a hand through what appeared solid but could not be grasped. The form is pushed ‘in and out of solidity’, wrote George Baker and thus ‘in and out of the sculptural field altogether’.43 Less concerned with artistic classifications and prompted once more by my religious upbringing, I discovered a reluctance to interrupt the purity or ‘sacredness’ of the beams, and found myself pondering the nature of faith and its creation of the two great intangibles: religion and art. When I saw McCall’s Long Film for Four Projectors (1974) restaged at Tate Britain in 2004, I equated the horizontal matrix of intersecting projection beams with the valiant searchlights crisscrossing the night skies above London during the Blitz, and recalled the bravery of those (including my mother) who stayed behind to keep the city going.

McCall’s spatial films clearly reiterate both the architecture of film projection and the fabric of the building in which he installs his work, in the case of the Round Chapel in Dalston, also articulating the intended public function of the building as a place of worship. However, McCall’s ‘solid light’ films also demonstrate the extent to which expanded cinema, steeped in a minimalist, structural tradition, can activate human emotion and our proclivity to plunder both personal and cultural iconography to narrativise non-narrative sense data. As Daniel Chandler affirmed, ‘above all, we are surely Homo Significans – meaning-makers’,44 and the weaker the representational content of the work, the more we invent its significance.

In spite of the perhaps unintended resonances of their work (the nature of religious faith; London in the Blitz), most first-generation expanded cinematic artists insisted that the ensemble of a projection event – the projector, the light beam, the space and the spectators – remained the central concern of the work. They emphasised the presentness of the live screening in contrast to what Malcolm Le Grice called the ‘retrospection’ of narrative cinema.45 An artist who combined the self-reflexivity of expanded cinema and the ‘retrospection’ of history was the American artist Tony Oursler. Since the 1980s he has created singular media events and, like McCall, used dry ice to make manifest the projection beam and the image that it conducted. In chapter five, I introduced Oursler’s multi-projection installation The Influence Machine (2000) staged in London’s Soho Square. As darkness fell, he released waves of billowing ‘smoke’ onto which were projected the faces of actors assuming the characters of inventors who had once lived in the neighbourhood, including John Logie Baird, the architect of television. While the work made clear references to pre-cinematic magic shows, it also recreated the spatiality of a film set or television studio complete with surround sound and vision. Spectators explored and edited their own version of the film as they went, with the real (the square, the buildings) and the illusory (the faces, the voices) held in almost perfect balance. By superimposing disembodied ghosts from the past onto the fragile substance of the present, drifting with the barest means of support, the work also created an uncanny sense of walking among the dead. There is a clear reference here to the rich tradition of Hollywood horrors, to fictional ghosts such as Dickens’s Jacob Marley and the ghoulish family in The Others (Alejandro Amenábar, 2001). However, Oursler also gestures towards the Derridian notion of hauntology, which the moving image so neatly illustrates with its ability to parade spectres from the past, messengers come to disturb the present with their unfinished business.46 These untimely intruders outstay their welcome and unsettle our concept of the chronological march of history.

In Borrowed Time (1997/2002), David Cotterrell drew on both film history and precedents in expanded cinema when he created a three-dimensional screen out of a mass of artificial smoke (liquid carbon dioxide) into which he projected footage of a rapidly oncoming train. The billowing ‘smoke’ was propelled towards the audience and engulfed the space so that, together with a soundtrack to match the ectoplasmic runaway train, the impression of imminent danger was palpable in spite of its obviously illusory nature. Cotterrell’s speeding train borne forth on its miraculous clouds nostalgically recreated some of the wonderment and terror early film audiences are said to have experienced when first exposed to the Lumière Brothers’ The Arrival of a Train (1895) or Thomas Edison’s Black Diamond Express (1896), with the added attraction that Cotterrell’s train was actually moving through space. Cotterrell appropriated and extended the reflexive strategies of expanded cinema from the 1970s, but like many artists before him, he exposed the mechanisms of the illusion whilst simultaneously celebrating its power to conjure up what is not there – in the case of Borrowed Time, the ghostly remains of the cinematic archive and the last gasp of the age of steam.

David Cotterrell, Borrowed Time (1997/2002). Montage using the original footage. Courtesy of the artist.

THE BEAM INTERRUPTED − BY THE ARTIST

Where Cotterrell and McCall animated the space between the screen and the projector with dry ice, other artists broke the projection beam with their own bodies and, like performance artists, they worked live, calling on audiences to attend timetabled events. As Robert Whitman remarked, in spite of its iconoclasm, performance has rules and ‘the convention here is that everyone is going to be in the same place at the same time’.47 In Zen for Film (1964), Nam June Paik presented an audience with the stark prospect of himself dressed in black, bathed in the light of a film entirely made up of clear, unexposed 16mm leader. The artist had his back turned to the audience and appeared to be contemplating his doppelgänger, his own shadow sharp-cut into the pure field of light, evoking shadow play, the most rudimentary film form. Paik and his shadow acted out simple tasks becoming what he called a ‘living film’ while the filmstrip itself was gradually polluted by the scratches and dirt that accumulated over repeated projections, creating a calligraphy of its own history. In chapter five, I discussed Gill Eatherley’s Aperture Sweep (1973), in which the artist stepped into the projection beam and cast a shadow, doubling her action of sweeping the ‘film’ with a broom. Adjacent to this image, she projected a film in which she is seen similarly engaged in the fruitless task of cleaning up a white wall that will forever attract the dirt. The humorous reference to the old adage that ‘a woman’s work is never done’ reverberates with a more rigorous critique of domestic labour and the low status of those who do it, paid or unpaid. Yet deeper resonances of the images both Paik and Eatherley generated suggest the allusive powers of shadows. ‘Shades collect the distracted attention,’ wrote Caspar Johann Lavater in 1778, and ‘confine it to an outline, and thus render the observation more simple, easy, and precise’.48 This condensation of meaning has its advantages.

In Carolee Schneemann’s Snows (1967), the artist and her band of performers cast shadows and broke the beams of several projections simultaneously, interrupting a montage of filmed atrocities from the Vietnam War. Snows expressed the anger of her generation towards an administration that was sacrificing thousands of US and Vietnamese lives to an indefensible war. Schneemann’s ‘rage and indignation’ is decipherable in the way she used bodies to ‘both absorb and fracture the film imagery’ and so ‘reoccupy’49 a medium that had packaged and laundered the war for home consumption. The bodies in Snows were not engaged in what Kenneth Koutts-Smith dubbed ‘an individual assertion of ego’;50 they were impersonal – as Schneemann asserted, she and her troupe were ‘visible carriers’ of the image, of meaning, but the body ‘is the material, it is not you’.51 Ulrike Rosenbach and Schneemann herself had begun by projecting slides onto their bodies, in Rosenbach’s case the image of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486). As Robert Whitman discovered, projection flattens the body, rendering it as functional as a cut out, and at that time, ‘it seemed natural to use a person as a surface’,52 a blank canvas on which to project film. However, there are moments in Whitman’s Prune Flat in which the figure cavorting in front of the screen synchronises with the fictional space of the filmic image, and here, the image ‘bursts into a superreality’.53 The figure, suddenly sprung out of its flatness, presents in the round and surges towards the audience in an early approximation of 3D film. The loss of anonymity for the performer, now the flesh-and-blood ‘hot spot’ at the centre of film, reminds us that a real person inhabits a fictional character in mainstream film. The role is brought to life by the skill of an individual who suffers and sweats, as those in the front row of Prune Flat will have been able to see for themselves.

A minimal work by Malcolm Le Grice in the UK centred on the single figure caught in the beam and also dramatised the individuality of the performer. In Horror Film 1 (1971), Le Grice stood naked in the path of three projected films loops, each creating a different field of colour. The visual display was accompanied by the sound of breathing and the mechanical heartbeats of the projectors. As Le Grice insisted, the spectator was offered no pro-filmic event. The ‘complete material of the film’ was presented direct to the audience.54 Having described the limits of each frame by stretching out his arms, Le Grice stepped backwards towards the projector so that his shadow or the negative space he cut out of the screen grew in tandem with his movements. Le Grice acknowledges that ‘something magical’ happens even though the audience knows how the film event is created. With nothing to cover his nakedness but shoulder-length hair and a fashionable beard, and with his arms outstretched, Le Grice presented a Christ-like, sacrificial figure anticipating Bill Viola’s later video works featuring the male figure drifting in liquid space. Both Le Grice and Viola gesture towards devotional imagery, but with the artists’ own images or shadows acting as a surrogates for the divinity, one might suspect a surrender to pure narcissism. However, I detect in Horror Film 1 a melancholic, elegiac quality, suggesting an acceptance of mortality and the fragility of the human frame. It could be that Le Grice, like Levin in Anna Karenin, is ‘stricken with horror, not so much at death as at life’ and in spite of the accumulated wisdom of science is left, ‘without the least conception of [life’s] origin, its purpose, its reason, its nature’.55 Where Levin, like Socrates, finds meaning in a life of ‘goodness’, the artist seeks transcendence and the comforts of enchantment in that moment of magic that film can produce. It is ‘OK to die’, mused Whitman, if ‘you know what it is all about for that moment when you are awe struck’.56

Malcolm Le Grice, Horror Film 1 (1971), 16mm film and shadow performance. Sound: Le Grice. Performance documentation stills. Courtesy of the artist.

In 1977 at the Hayward Gallery, Chris Welsby experienced a delightful audience response when he installed Shoreline 1, a work referenced in chapter five. A row of six 16mm projectors showed a looped sequence of the seashore on a sunny day. In spite of the slight gaps between the projected images and the lack of synchronisation in wave formations across the screens, the six images made up a broad panorama of the ocean’s horizon and the liminal space between land and sea. With the projectors positioned at the back of the gallery, the only way to access the work was to interrupt the projections. Welsby takes up the story:

When you walk through those beams of light, you get a ‘now you see me, now you don’t’ alternating effect because you cast a shadow on the screen until you get in a gap between the projectors … One young woman upset the uniformed attendants when she did a series of cartwheels straight through the beams of the projectors. This produced a wonderful chain of frozen images across the six screens. It was a great little performance piece and the result looked like an animated film.57

Chris Welsby, Shoreline 1 (1977), ACME Gallery, a six screen film installation/16mm film loops. Sound: ‘live’, 6 projectors. Courtesy of the artist.

The anonymous acrobat showed her instinctual understanding of the piece by enacting another layer of live, paracinematic film. She transformed herself into a sequential, intermittent double image, a girl and her shadow taking flight, whilst simultaneously defying the institution by breaking its unwritten rules of decorum.

THE BEAM INTERRUPTED − BY OBJECTS

In spite of the anarchic gesture of Welsby’s spectator and the enigmatic presence of Le Grice-as-Christ, a body part-hidden, part-revealed in a projection beam is flattened and fractured, and, as Whitman observed, it takes on a more generic aspect approaching the condition of an object. Conversely, some artists have projected onto inanimate objects so that the moving images might appear to bring them to life. In the UK, Ron Haselden projected a film of a naked woman and her dog onto stills of the same film so that the figures appeared to lift out of a flat plane. In the 1970s, Tim Head took slides of objects and projected them back onto those same objects. The image appeared to hover over its double like an extrusion or an aura. In 1980 at the Whitechapel Gallery, Head collaborated with Miranda Tufnell and a troupe of dancers to create a dynamic projection performance (untitled) using simple boards. Head describes the work as follows:

This piece consisted of a large film projection of a waterfall (filmed by Richard Welsby). The dancers stood in front of the projection holding large flat white screens over which the waterfall cascaded. When the film started, the dancers/screens were invisible but throughout the piece, they moved the screens in different directions, revealing themselves and increasingly breaking up the image.58

Depending on its proximity to the projector, each incursion by a roving board varied the scale and resolution of the filmic image. When thus confined to a smaller frame, the fragments of the projection took on moments of solidity only to be cast back into the flow of the larger image as the dancers and their screen/boards disappeared. The work articulated a notion of cognition that David Peat has derived from both David Bohm and Carl Jung, one in which the senses piece together an impression of the world from elements extracted from the undifferentiated flux. In order to communicate its perceptions, the human subject has recourse to language and representation, which further compress and schematise reality.59 Nevertheless, in Whitman’s moments of awe, the subject momentarily reconnects with the flux of the world, with what Bohm calls its ‘holomovement’. The elfin figures in Head’s projection performance with their fugitive moments of pictorial condensation went some way to evoking the deeper connectivity of the discernible parts to the immeasurable whole.

Film projection onto objects has taken many forms, adopting image-supports that are sometimes as ephemeral as the projected image itself. In chapter three, we saw how James Elkins endowed objects with agency capable of changing us through the ‘threads of desire’ that bind us to them.60 There are works that expose our desire for the object by thwarting it, by revealing the coveted artefact to be a chimera. When Carolee Schneemann performed in front of a screen in Ghost Rev (1965), she blew soap bubbles that, for a moment, became floating, spherical screens. No sooner had these entrancing globes come into being than they popped, casting the image into oblivion. In Germany, VALIE EXPORT was equally fascinated by the ephemerality of film, and as I discussed in relationship to architecture, its ability to dissolve solid matter. Export employed the material and reflective properties of a mirror to simulate the effect of film without the use of traditional film materials and processes. In abstract film no. 1 (1967–68), a projector’s light beam was directed at a mirror down which bands of red paint were slowly trickling. The image was refracted, at an angle, onto a wall, which gave the illusion of moving pictures deriving from a projector with no film, which was confusingly pointing away from the screen. The object interrupting the light created, not a shadow, but the moving images themselves. In Italy, Marinella Pirelli constructed a grid of semi-transparent, semi-reflective screens for her installation Film Ambiente (1969) into which she projected abstract films.61 The complex arrangement of screens interrupting and refracting the light resulted in the image detaching from the screens and hovering in the spaces between, forming a volumetric, glowing mass.62 If Pirelli used film to thicken light into a solid filmic presence, artists such as Schneemann, Dan Graham or Guy Sherwin manipulated mirrors to scatter the image around a space, a process that was most affectingly exploited by David Dye in his film performance Western Reversal (1973–2009). Crouching at the front of the gathering, his back turned to the audience, the artist lifted into position a board on which were fixed sixteen car wing mirrors, arranged in a grid. Into the mirrors, he projected a Super 8 film of a looped sequence from a cowboy film featuring a posse in hot pursuit of an archetypal baddie. Dye gradually angled the mirrors so that the film fractured into perfect part-views of the sequence, creating a firmament of rushing cowboys travelling up walls and across the ceiling. As the film spread out, it demanded an increased effort to mentally reassemble the fragments into a coherent image. The work created a slow motion, exploded cinema anticipating Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), in which a garden shed was famously blown up and the shards reassembled to simulate the moment of execution. Dye also restored his film, turning the mirrors so that each element was slowly brought back into alignment, once again forming a legible representation. The deconstruction and reconstruction of the cowboy sequence conformed to the avant-garde requirement for reflexivity and explored the ‘complex relationships of technology’, old and new.63 It also amply demonstrated the playfulness, the gleeful tinkering with vision machines of much expanded cinema from the 1970s. The same delight in homemade gadgetry, providing what A. L. Rees defined as ‘all the world in a sink’,64 is still much evidence today. Torsten Lauschmann’s media performance The Amen Break (2014) similarly deploys mirror reflections, this time bouncing the film off a rotating mirror ball and radiating a constellation of moving points of light around the gallery. A reassuring patina of dance hall nostalgia was interwoven with complex digital sounds and images, themselves guarded by two hectic digital clocks counting out a slice of the audience’s allocated time on earth, creating a rollercoaster sense of kairological time (as experienced), running out at an alarming rate.

If Lauschmann’s work was designed to stimulate both enchantment (the lights) and anxiety (the clocks), System for Dramatic Feedback (1994) by Tony Oursler sought to stir empathic human responses in its audiences. Oursler projected onto the blank faces of small rag dolls footage of human heads in the throes of emotional turmoil – one stuffed creature, slumped pathetically in a corner, cried out ‘Oh no! Oh no!’ The anguished faces animating the cloth heads contrasted with the paralysis of their limbs and suggested deformed or stunted adults at the same time conjuring the Punch and Judy shows of childhood. In his essay The Uncanny (1919), Freud quotes Ernst Jentsch who discovers the uncanny in the ‘impression made by waxwork figures, ingeniously constructed dolls and automata’ and these produce ‘doubts … whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate’.65 The heightened realism of the moving image certainly contributed to the live/lifeless ambiguity of Oursler’s dolls and their small scale relative to the bodies of the viewers inspired a physical response, a perhaps parental urge to rescue the distressed effigies and dry their tears. As we saw in chapter eight, the empathetic response enables the spectator to ‘feel himself into a kindred object’66 from which s/he may derive a new perspective, new knowledge of the world. In this case, a double empathy is at play, first for the tormented human subject embodied by the image and secondly for the object onto which it is projected, and, according to Christine Olden, this is achieved only when ‘the subject temporarily gives up his own ego for that of the object’.67 By means of such a renunciation, the spectator may reverberate with the feelings of others. The obvious, burlesque fakery of the ‘human’ spectacle: the overacting, the video projector, beam of light and crudely-made toys rendered the impulse to rescue Oursler’s inanimate creatures absurd, but no less powerful for that realisation. By revisiting the self-reflexivity of three-dimensional let’s-pretend, and setting up a physical relationship between the spectator and the dolls, emotional engagement took place where, for me, works by Bill Viola and Sam Taylor-Wood that similarly employ actors ‘emoting’ in flat-screen projected works remain curiously remote. It may well be that through System for Dramatic Feedback Oursler is expressing his own identification with people, machines, artefacts and objects onto which he projects his fears and desires, and his yearnings for almost animistic transcendence. As the artist affirms, ‘mimetic technology’ is ‘a direct extension of psychological states’.68

Tony Oursler, System for Dramatic Feedback (1994). Courtesy of the artist.

THE BEAM MULTIPLIED AND MANIPULATED

The multiplication of the projection beam increased the potential for both the creative enterprise of artists and the audience’s interactions with projected light. In 1964, Charles and Ray Eames installed the IBM ‘Information Machine’ at the New York World’s Fair, a dome fitted with 22-screens across which paraded the wonders of modern American life. A year later, Stan VanDerBeek’s ‘cultural intercom’, offered a new media environment that included image transmission, radio, electronic sound, cinema and theatre. Movie-Drome (1965) was a technical Gesamtkunstwerk in which ‘simultaneous images of all sorts would be projected onto an entire dome-screen’.69 In the UK, Lis Rhodes’ Light Music (1975) was a modest two-machine affair, the light beams staring each other down while a vertiginous cascade of geometric shapes sparred in the no-man’s-land in between. Caught in the cross-fire, I was reminded of James Elkins’ epithet that light is ‘an acid; it burns into me, it remakes me in its own image’.70 The network of lines scurried across the bodies of the spectators and I felt we had been transformed into mere topographical accidents in the terrain of Rhodes’ vertiginous optical fields. Although many multi-projection works were frontal, others deployed screens irregularly in the gallery and the simultaneity of the projected images both spatialised the work and compromised the linearity of cinematic time – it was not possible to follow all the screens at once. The multiplication of the image was also occurring in video as we will see in chapter eleven, but in terms of film installation, the deployment of several simultaneous projections emphasised the fragmented nature of perception, the partial view that is any representation. Lacking eyes in the backs of their heads, spectators were obliged to accept that they could never apprehend the total artwork but only self-edit a truncated version within which all other permutations were contained as unrealised potentialities.

Multiple-projection expanded works by artists such as Steve Farrer, Lis Rhodes, Nicky Hamlyn and, later, Tacita Dean reiterated the projector as an industrial machine playing its part in the complex system of production, distribution and exhibition of film, whilst repurposing the device as a ‘sculptural presence’,71 whose functions became the material of an aesthetic display. In their most dynamic, massed presentations, projectors also took on the aura of military hardware, an equivalence first intimated by Paul Virilio when he linked projectors with the mechanism of a machine gun.72 In the early 1960s, the US military developed a portable video device used for the ‘enlargement of the military field of perception’ in Vietnam; just one example of the entwined industries of cinema and ‘the theatre of war’ where a ‘deadly harmony … always establishes itself between the functions of eye and weapon’.73 The act of projection could itself constitute a form of aggression. Spectators captured in the line of fire between projection beam and screen can experience a work that shoots light at them, or that blinds them with strobing light, as a form of assault. In Mirror Performance (1974), the Polish artist Jósef Robakowski did just that. Journalists with flash cameras retaliated by firing bursts of light back at the projector, thus participating in an extended light beam shoot-out.

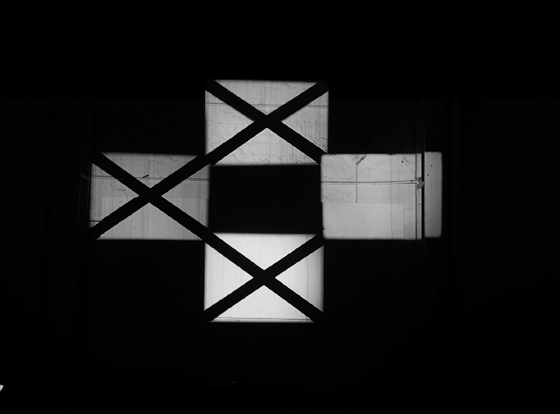

In the 1970s, British artist Nicky Hamlyn operated banks of projectors aligned to create shifting fields of abstract imagery and in an apparent reversal of installation principles, he adopted a frontal presentation for seated audiences summoned by a timetabled event. Where Dye fractured and dispersed a single image by means of mirrors, in 4 X LOOPS (1974), Hamlyn assembled his ‘film’ from the four source projectors. As the work progressed, he slowly angled the projectors to create several permutations of abstract grids – vertical, horizontal and diagonal – built on the interaction of the films consisting simply of four identical ‘Xs’, looping through each projector. The repeat patterns that formed and dissolved could theoretically have extended beyond the frame into infinite space and time. Where X would conventionally mark a spot, the drifting crosses never settled in one place, never found a definitive semiotic anchorage nor formed a stable aesthetic arrangement. The projectors, rather than embodying single, deterministic points of view, represented one among many potential perspectives in a choreographed performance in which chance also played a part. The decisions the artist made on the day, random interruptions of the beams by viewers, variations in the technical set-up and the local conditions subtly inflected each iteration of the work. When 4 X LOOPS was re-enacted in 2004, the row of four projectors seemed to stand to attention and salute the history of analogue film. Beyond this impression, the work resisted interpretation and participated in a form of cinema in which, as art historian Michael Fried advocated, ‘conditions of seeing prevail’.74 The slow manipulation of a graphic sign, drained of referential content through repetition, was intended to maintain in the audience a consciousness of the cognitive processes the human subject undergoes as it deciphers both media information and the cacophony of sense data emanating from the world at large.

Nicky Hamlyn, 4 X LOOPS (1974). Courtesy of the artist.

David Dye and contemporary exponents of the accented-apparatus genre of expanded cinema transformed the film projector from what Hamlyn described as a ‘passive projection device’ into an ‘active tool for the creation of new kinds of films’.75 They dramatised both the mechanics of projection and the hidden skills of the projectionist. In Against the Steady Stare (1988), Steve Farrer not only explored the projector’s latent potential, but also gestured towards the associations of violence ascribed to the technology by Virilio. Combining the function of camera and projector, Farrer utilised the same device to both shoot and project the film. He placed the machine in the centre of a space surrounded by a circular, continuous screen, creating an arena into which spectators might venture. The camera-projector came to life and, with the aid of motors, rotated on its axis extremely rapidly creating an unbroken, frameless film that could either be followed athletically by turning at the same breakneck speed as the projector, or by concentrating on one part of the screen. Spectators were then rewarded with visions of spectral figures mysteriously appearing and fading away, a function of the coincidence of the spinning projector’s speed and the persistence of vision. It was like sitting inside a giant zoetrope surrounded by the ghosts in the vision machines of yesteryear. Beyond the auratic materiality of the projector and the enchantments of the apparitions onscreen, the dominant readings of the work remained the materialist anatomisation of the film apparatus and Virilio’s machine-gun/projector analogy. However, as mentioned in chapter three, the real danger of the installation emerged at a screening in Modern Art Oxford; the artist cheerfully announced that the projector might fly off its housing at any moment in which eventuality, we would be best advised to duck. Nicky Hamlyn remarked that Against the Steady Stare ‘recreated in three dimensions the layout of the pro-filmic space’,76 collapsing the distinction between the architecture of the conventional cinematic projection and that of the set or location in which the film was shot. A further equivalence existed in the identical speed with which the camera/projector rotated when both filming and projecting the film. The structural specificities of the work were certainly apparent at the screening I attended, however; the sense of personal risk and the spectral effect of the image created an intensity of experience that was more visceral than conceptual, an affective dimension that was much in evidence in expanded cinema of the period.

LIGHT WORKS AND ‘PARACINEMA’

As the wings and limbs were being pulled off the butterfly of film and its vital organs laid out for forensic scrutiny, a variation on expanded cinematic works emerged for which Jonathan Walley popularised the term ‘paracinema’. These were practices, he said, that ‘recognise cinematic properties outside the standard film apparatus’.77 Paracinematic works often dispensed with the conventional architecture of film, camera, projector and screen, or, like much structural film, isolated one or two key components such as light, time, the filmstrip and/or the presence of an audience. As I have indicated, Steve Farrer made several ‘cameraless’ films, such as Ten Drawings (1976) in which he painted directly onto strips of film laid out on the floor, celluloid canvases that, once joined together, constituted a film in which time had been rendered as space.

Within the paracinematic logic, any manifestation of artificial light might contain within it the essence of film. Natural light was already an object of fascination in the sculptural ‘sky observatories’ of the great poet of light, James Turrell. Tungsten light, the artificial, man-made source of night-time illumination, which provided the life-blood of analogue film, was similarly foregrounded, and sometimes separated entirely from the projector, as we saw in Le Grice’s Castle One. Robakowski had already attempted to blind his audience with projected light and in Light Wall (2000), Carsten Holler further exploited the destructive potential of light, bombarding viewers with flashing searchlights powerful enough to induce an epileptic fit in the susceptible. In a similar vein, Eva Koch exhibited tungsten light in its revelatory mode and then gradually exposed its capacity to obliterate vision. Multi-media sculpture (1990) consisted of a high-walled enclosure in the shape of a spiral that lured the visitor in with a light that grew in intensity until, at the heart of the structure she was confronted with a scorching, blinding 1,000-watt lamp that made it impossible to discern what, if anything, lay beyond. Other artists have exploited the afterimage that lingers once the source of a bright light has been extinguished, thereby bringing into awareness the impact of light on the rods and cones of the retina and the interpretive work of the visual cortex. Luke Jerram took advantage of the optical effect of afterimage in his Retinal Memory Volume (1997), staged in a darkened space in which a chair was just discernible in the gloom. Three flashes of bright light, released in quick succession created a three-dimensional afterimage of the chair that seemed to float in the field of vision. The chimerical chair was created entirely by the physiological apparatus of vision responding to a sudden onslaught of light. Once the afterimage faded, its documentation resided only in memory.

The light from a projector lamp gives life to filmic impressions but its heat can also consume the image if the filmstrip is brought to a halt. Many artists staged the scorching of celluloid ‘seized’ in a projector. In Bad Burns (1982) Paul Sharits compiled a series of ‘mis-takes’ from an earlier film, complete with visible sprocket holes and impenetrable, blurred imagery. Running vertically past a powerful source of light, the footage is displayed in full flight, periodically juddering to a stop, at which point the viewer witnesses the execution of the condemned frame as the heat from the lamp melts the celluloid, the damage spreading like a stain across the image. Sharits drew an analogy between the fragility of human life and the vulnerability of the filmstrip to the element that both brings it into being and potentially destroys it.78 Both the filmstrip and the human subject ‘struggle on’, but like many pyromaniacs, the artist sees ‘a formal beauty in the destructiveness of the burning film’.79

Another effect of light within the apparatus of film attracted the forensic attention of artists such as Sharits, Brion Gysin and Tony Conrad. They all contrived to amplify the flicker inherent in analogue film to the point that it compromised visual perception and rendered the film unwatchable. Conrad’s The Flicker (1966) consisted of alternating black and white frames, creating a stroboscopic effect and inducing in spectators if not epileptic fits then hallucinations, debilitating retinal afterimages and prolonged headaches. Sharits’s double screen, ‘locational’ installation Epileptic Seizure Comparison (1976) explicitly linked the optical effect of flicker to physiological malfunction, showing two men undergoing ‘majestic’ convulsions, their contortions corresponding to the pulsation of the footage alternating with black, interspersed by passages of pure, abstract flicker. This optical endurance test was wrapped in a soundtrack devoted to the distorted utterances of the epilepsy sufferers layered with recordings of their electromagnetic brain activity. The work was a powerful testament to the dangers of the extreme effects of light, latent in the normal functioning of motion pictures, and the vulnerability of the perceptual system.

SENSORY OVERLOAD

When expanded cinema assaults the senses, it calls into question avant-garde claims that such work promotes interactivity and the mobilisation of a critical, reflective viewer freed from the manipulations of cinematic illusionism and narrative identification. Nicolas de Oliveira commented that in contemporary installation, ‘sensation itself appears to have replaced the traditional art object’.80 A positive gloss has attached to this ‘empire of the senses’ following Maurice Merleau-Ponty who in The Phenomenology of Perception (1945) declared that objects cannot be separated from the system that apprehends them, whether human or mechanical. Yet it has been one of the objectives of the avant-garde to disconnect the various perceptual effects from the cinematic apparatus that generates them. Merleau-Ponty also observed that we attribute values to objects through the senses, and many artists have enlisted those same senses precisely to divest objects of conventional meanings, to enact a détournement of associations as a way of wresting the sign from its referent and loosening inhibitions on the imagination.

Other commentators such as the installation artist Robert Irwin and the filmmaker Malcolm Le Grice have suggested that the senses, when sufficiently stimulated, can circumvent the intellect thereby downplaying the long reach of culture into our embodied experiences. According to Le Grice, through purely sensory stimulus, especially colour, we can bypass the regime of Western rationalism and ‘return, if momentarily, to the pre-verbal, the regressive and ecstatic’.81 This is a sentiment echoed by Gilles Deleuze when he argues that cinema is a ‘composition of images and signs that is a pre-verbal, intelligible content (pure semiotics)’.82 This invocation of the unmediated purity of the primitive human sensorium leads Irwin in particular to the conclusion that when identically stimulated, all men (and women), in their delirium, are rendered equal.83 Claire Bishop pointed out that in the 1960s, the affirmation of La vivencia, or sensory plenitude, was a form of political resistance to the repressive military regime holding sway in Brazil. The senses represented one of the few areas of existence that could evade policing by the state.84

Beyond its democratising potential, extreme sensation is also said to activate a transgressive repertoire of unconscious dreams, fears and desires. This belief informed the cathartic performances of the Viennese Aktionists in the 1960s as well as the philosophy of Georges Bataille, who advocated sensuality and the body in extremis as a route to the sacred and ‘a privileged moment of communal unity’.85 However, I would suggest that sensory overload can also crush all but the most spontaneous reactions of the autonomic nervous system, and inhibit the kind of critical thinking the avant-garde ostensibly wished to promote. In the early 1960s, Andy Warhol created even more elaborate multi-media works than those of VanDerBeek, combining films, slides, light shows, dancers and a barrage of sounds including live performances by the Velvet Underground. If the intention was, at least in part, to raise viewers’ awareness of their own cognitive and interpretive processes, in practice, Warhol made it virtually impossible for the audience to interact with the work other than by surrendering to its purely immersive, sensory aspects. Reviewing Warhol’s multi-media extravaganza Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966), Michaela Williams was driven to protest that people ‘become nothing more than parts of it, receptors essential to its functioning but subordinate to it and manipulated by it’.86 Far from being empowered, visitors were stupefied by the visual fireworks and the din and, said Williams, ‘to experience it [was] to be brutalised, helpless’.87 My own notes on viewing a re-enactment of Steve Farrer’s 10 Drawings (1976) expressed much the same sentiment: ‘from lines to grains, blips and rushing sounds, a hideous insistent rhythm … I can’t shake off an overwhelming urge to escape’.88 As I have intimated, I have responded in much the same way to optical works by Michael Snow, or loud, durational pieces by Gibson and Recoder or other installations by artists determined to deafen, blind and disorient their audience or bore into their brains with rapid-fire repetitions. However engaged I might be with the conceptual underpinnings of the work, the event itself gives rise only to my finely-tuned sense of survival when confronted by inassimilable sense data. At the extremes of expanded cinema where a kind of anti-narrative, vertiginous abstraction ruled, the audience was indeed an instrument of the work. In this context, the principle of distanciation, or the oscillating ‘alienation effect’ advocated by Berthold Brecht becomes all but redundant.89 The potential of distanciation to create a questioning, engaged audience is occluded when all thought is drowned out by the strickened senses. All that remains is to decide whether to stay or safely remove oneself and consider the significance of the work including the possibility that it is a simple act of aggression. In moving image works deploying disproportionate optical and sonic stimuli, it is the artist’s will that is positioned as the dominant, organising principle of the work, forcibly taking control of spectators’ reactions. Narrative film is a mere amateur in audience manipulation in the face of work specialising in sensory overload. Keith Tyson has reflected the underlying intellectual poverty of such practices when he remarked that spectators should not ask ‘what is it about, but how do I feel?’90 His attitude heralds a return to emotionalism and a retreat from the political and ethical principles that informed installation-based work in the counter-cultural era.

Even benignly immersive, meditative and ambient works designed to enchant rather than terrify – Pipilotti Rist’s mood-enhancing, diaphanous multi-screen Administrating Eternity (2011) or Doug Aitken’s New Ocean (2001), a surround-sea projection complete with passing ships and melting glaciers – can be problematic. In 1851, Herman Melville warned aspirant sailors of the hypnotic effects of gazing too long at the sea: ‘lulled into such an opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious reverie is this absent-minded youth by the blending cadence of waves with thoughts, that at last he loses his identity’.91 When exposed to enveloping, oceanic installations there is a loosening of spectatorial agency in the process of what Peter Osborne calls ‘contemplative immersion’.92 The work functions as a ‘vehicle of flight from actuality, from the very temporal structure of experience which it must engage if is to be “contemporary” and “effective’”.93 The avant-garde commitment to ‘actuality’, to the here-and-now of the cinematic apparatus is thus undermined by the soporific effects of immersive works that do little to enlighten the spectator beyond the ‘culinary’94 pleasures of mainstream fodder. As I have suggested, at the other end of the scale, barrages of ear-splitting noise and blinding light effectively exclude spectators from the work. However, there are artists working in expanded cinema who have more fruitfully exploited three key components in the anatomy of cinema, namely light, colour and sound.

LIGHT SIGNALS

When operating within the standard tolerance of vision, lights have functioned as a means of communication since time immemorial. Installation artists have migrated to the gallery the semiosis of light, drawing inspiration from hilltop fires, reflected light signals and Morse code. Their works have incorporated the warning beams of lighthouses (Chris Wainwright, Tacita Dean, Susan Trangmar), airport runway lights (Graham Ellard), climatic indicators (Chris Meigh-Andrews) and the emergency lights in African mines (Steve McQueen). In their paracinematic, detached condition, lights can generate new meanings. For example, in Lights in the City (1999) Alfredo Jaar converted red lights conventionally associated with love for sale to a social and political purpose. The artist rigged up a 100,000-watt beacon in the cupola of a market tower in Montreal and linked it to the local shelter for the homeless. Every time a new client came in for the night, the light in the cupola was triggered and blazed its crimson message across the city. Through a flagrant consumption of electricity, Jaar drew attention to the plight of the 15,000 people living on the streets, a crisis that the civic authorities were doing little to alleviate. The symbolism of the red lights, the emotional impact of the glowing tower proved more instructive than would a documentary exposition of the social ills suffered by the poorest in Canadian society.

A more distinctively paracinematic framework informed Long Film for Ambient Light (1975) by Anthony McCall, a work that invoked the traditions of both gallery and cinema, but dispensed with all the paraphernalia of film except light. The gallery space was illuminated by day with diffused natural light from a series of semi-screened windows and by night by a bare light bulb with visitors coming and going, staying as long as they chose to remain ‘in the film’. The subject of the film was the gallery itself, and its visitors acted as the performers – cast adrift without a script. In Matches (1975), Annabel Nicolson similarly rejected standard film conditions and substituted conventional illumination with the most ‘precarious light source’, a match.95 Two members of the audience were summoned to read the ‘script’, the rhythm of the piece being determined by the duration of the flare of each match, the sole means of illuminating the text. Lucy Reynolds has argued that Matches recalls a darker age of softly flickering shadows before electricity rendered them static and hard-edged. The ‘unstable flame’ also embodies Nicolson’s notion of ‘fugitive vision’,96 encapsulated in her evanescent but highly resonant expanded works. Martin Creed is a contemporary exponent of this tradition, fusing the paracinematic with the space and conventions of the gallery. I have already cited his Lights Going On and Off, installed in an empty gallery at Tate Britain in London, a work that won him the coveted Turner Prize. This ultra-minimalist work consisted of a simple switching mechanism that did what it said on the tin: switched the lights on and off at regulated intervals. The ultimate contraction of film to the presence or absence of light in Nicolson, McCall and Creed is arguably equivalent to the modernist blank canvas. At one level, it represents the tautological end game of conceptual art, at another the pursuit of a reductive sublime, and light according to Goethe is ‘the simplest most undivided, most homogenous being that we know’.97 Works that pursue the essence of cinema have yet to divest themselves of the final encumbrance of an artwork – the spectator – leaving the light to flicker in its own splendid isolation (surely the next logical step?).98 Even the most reductive of paracinematic, minimalist or contracted/expanded cinema works, then as now, still needs the spectator, a participating witness to register the drift of film towards the precipice of its own demise as a separate category of cultural activity – and indeed bear testament to its rescue.

COLOURED LIGHT

Pick up any art book and look at the index. No reds, blues or greens.

Derek Jarman, Chroma, 1995

If we return from the brink of film extinction and, taking our cue from Alfredo Jaar, consider colour as another element in the repertoire of expanded cinema, it allows us to put our mapping of film anatomy back on track. Colour like light, which contains the whole spectrum of hues, helps us to negotiate our environment, and identify and classify objects. In ‘retinal’ painting, the Impressionists began the process of liberating colour from objects while the Fauvists used vibrant colour to rupture everyday appearances. Matisse is credited with placing colour in the service of pure expression although the Church must be allowed to claim the distinction of first exploiting the mystical power of saturated colour in its dazzling stained-glass windows. Many minimalist artists have separated colours from their association with objects and re-presented them in a purely optical register capable of eliciting emotional, aesthetic and even transcendental states of mind. ‘Colour is the most distant thing there is from words’,99 declared Malcolm Le Grice and in Matrix (1973–2006), a three-screen film installation, he explored the affective power of the three primary colours randomly distributed across a rapidly cycling matrix of squares. In Primary Phase (2006), Simon Payne fielded four projectors in a looping, balletic study of primary colour relationships in which unfettered chromatic spillage beyond the frame occurred – reds, yellows and blues leeching into the surrounding area. Payne’s installation edges into the age of digital projection and was anticipated in the UK by analogue video works by the Japanese artist Mineo Aayamaguchi, who embraced the bleeding of colour as a constitutional feature of video, confirming Yves Klein’s assertion that colour is imprisoned by line. In The Crystals (1983), the British composer Brian Eno used upturned monitors emitting coloured light to bathe staggered abstract structures, like film flats in a Disney fantasy. The same ability of video display units to wash a space with colour is evident in Angela Bulloch’s Z-Point (2001). The artist reduced a scene from Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point to its component colour pixels blown up as a grid of slowly changing, coloured light boxes. Stripped of their narrative purpose, these experiential colour works evoke the dizzying harmonies and contrasts of jazz. Le Grice cites a longstanding correspondence between colour and music, and quotes Wassily Kandinsky who sought to establish universal meanings for colours: ‘vermilion stimulates like a flame … keen lemon-yellow hurts the eye as does a prolonged and shrill bugle note the ear, and one turns away for relief to blue or green’.100 Following Goethe’s famous 1810 Theory of Colours, a thesis that ranked the experience of colour above the science of optics, Kandinsky studied the effects of synaesthesia linking colour to smell, temperature and especially to sound. Le Grice himself observed that the computer, through which passes most contemporary imagery, is essentially synaesthetic in that it can code the same set of numbers as either colour or sound. In the wider culture, black and white or a reduced palette connotes either ‘time past’, melancholy or ‘serious content’, and is much favoured by the current flowering of ‘Nordic Noir’.101 It is principally film and television aimed at children, and advertising that exploits saturated, contrasting colour. The visual impact of primaries is also used to enhance the appeal of consumer products, music videos, commercials, programme idents and sports events. Even cricketers have abandoned white.

David Batchelor maintains that such promiscuous use of colour was outlawed in the modernist period of high art when the grey fields of minimalism and conceptualism prevailed.102 As a result, Batchelor asserts, colour has been coded in the discourse of art as kitsch, decadent and subversive, associated with the body, with homosexuality and the feminine. Kenneth Anger, speaking in London in 2009, declared that ‘Lucifer is the patron saint of colour’,103 confirming the association of colour with the desires of the flesh and a fall from grace. Women artists also exploited the cultural correspondence of deviancy and colour. Since the 1960s, Yayoi Kusama has covered herself in polka dots, predominantly red, pink and white, and camouflaged her body in environments that were similarly tinted. In her film Self Obliteration (1967), Kusama fused her own body with that of a tree, a horse, a cat and a stream by scattering them indiscriminately with her trademark dots. Red dominates her colour palette, evident in the blood red of her costume and in the bleeding circular shapes she released into the stream. Claire Bishop has interpreted Kusama’s work as a reference to Freud’s theories of the death drive and the desire to fuse with inanimate objects and thus return to the earth. However, colour in Kusama’s work could also be read as a symptom of a persistently phallocentric culture. Femininity is red seeing red, and borrowing Jarman’s colour coding, in Kusama, red is ‘the daughter of aggression, mother of all colours’.104 Superficially, the red may seem to serve a surface ornamentation; however, red here also signals excess, delirium, danger, the edge of madness. The artist’s body ‘holds the psychedelic color’105 that not only expands the mind but is also the red of menstrual blood with its folkloric taboos derived from the ancient belief that menstruating women could blight crops and cause livestock to miscarry. In the utopian zeitgeist of the 1960s, Kusama was, through her art, opting out of an equally alienating modern world in which the American subject was ‘mechanized and standardized’.106 Instead, she tuned herself into a universe of colour, a place in which she could achieve mystic union with all of creation and, garmented in her matrix of dots, lose herself ‘in the ever-advancing stream of eternity’.107

Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration (1967), 16mm, 23 min. Courtesy of the artist. © Yayoi Kusama.

SINKING INTO RED, YELLOW AND BLUE

Colour enables Kusama to erase her boundaries, camouflage her mental turmoil and melt into the landscape. However, when colour is released from representation altogether and escapes the regimentation of the film frame, or the more cordoned, display-style form of installation, it can displace reality and undermine the classification of things, the orientation of objects in space and, as Le Grice observed, spectators find themselves ‘responding to a sensation outside the field of meaning’.108 In Wedgework III (1969), James Turrell created what seemed to be a wedge-shaped wall that, in fact, consisted of projected coloured light, in this case a soft lapis blue. The illusion was so convincing that a woman leaned against the ‘wall’ and fell through it, later trying to sue the artist for the trauma she allegedly suffered. Turrell conceives of his retinal installations as ‘objects of perception’ and the colour fields he creates are designed to highlight the workings of vision and colour perception, and as in all these colour-saturated environments, they make us aware that the eye is only a messenger – seeing is the work of the brain.