Detour: The Route Valcarlos

Detour: The Route ValcarlosSaint-Jean-Pied-de-Port Km 779.9

Few places on the Camino capture the exhilaration of the journey ahead as this threshold at the foot of the Pyrenees. Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port has been a pilgrims’ staging place for over 900 years. Many knew that going forward from here was the final commitment: once they crossed the mountains, there was no turning back. The deeply worn cobblestones of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port echo the electricity and the anticipation of hundreds of Camino travelers arriving each day to begin their adventure. Here, and in Roncesvalles on the other side of the mountains, is where many form the beginnings of their “Camino family” with people who share the same albergue (hostel) on the first night of their journey. Your “family” is part of the magic of the Camino. They will serendipitously appear on and off for the rest of the trek, becoming a part of a network of reliance and comfort peregrinos (pilgrims) offer each other throughout.

This stretch of the Camino passes through some of the prettiest natural landscapes of the entire route. The Valcarlos Pass over the Pyrenees offers stunning views from one of the three highest altitudes of the Camino (the other two are in León and Galicia, at Monte Irago and O Cebreiro respectively). The trail through the forests from Roncesvalles to Zubiri is enchanted with beech, oak, and pine trees, and native wildflower and birdlife. This section of the Camino also weaves together several overlapping cultures and languages—Basque, Navarrese, Gascogne, Occitan, French, and Spanish. It also traverses the territory where Ernest Hemingway liked to go trout fishing in the Pyrenees (in Burguete, just after Roncesvalles), a passion captured viscerally in his novel The Sun Also Rises. The rivers here are still plentiful with excellent trout, which make their way onto many local menus, fried with cured ham and red peppers, and served with local wines—from the effervescent white txakoli to the coveted Irouléguy and Navarrese rosés.

In spring, the hills erupt with multicolored wildflowers even as morning frost still frames the leaves and grasses with shimmering edges. In autumn, the African pigeon makes a massive migration south, turning this part of the Pyrenees into pigeon-hunting madness for the succulent bird. This is a territory rich in fertile mountains and river valleys, in culinary traditions, and in some of Europe’s oldest cultural practices and outlooks. Quite a threshold indeed to begin the Camino, with a first day set to surmount one of the trail’s toughest legs.

If you are arriving in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port directly from a far-flung international destination, consider allowing yourself two days here to recover from jetlag and to have time to soak up the pilgrim town, your only French town before crossing the Pyrenees on the Camino. Allow 3-4 days for walking this 68.4-kilometer (42.5-mile) stretch, when averaging 20-25 kilometers (12.5-15.5 miles) a day. You may also want to build flexibility into your start to allow for changes of weather any time of year, especially from early autumn to early summer, that might delay crossing the Pyrenees.

Note that not all accommodations, especially the pilgrims’ albergues in Saint-Jean, have wifi (though you can get it at the Pilgrims’ Office in town). When you cross the Pyrenees on the way to Roncesvalles, wifi is all but nonexistent.

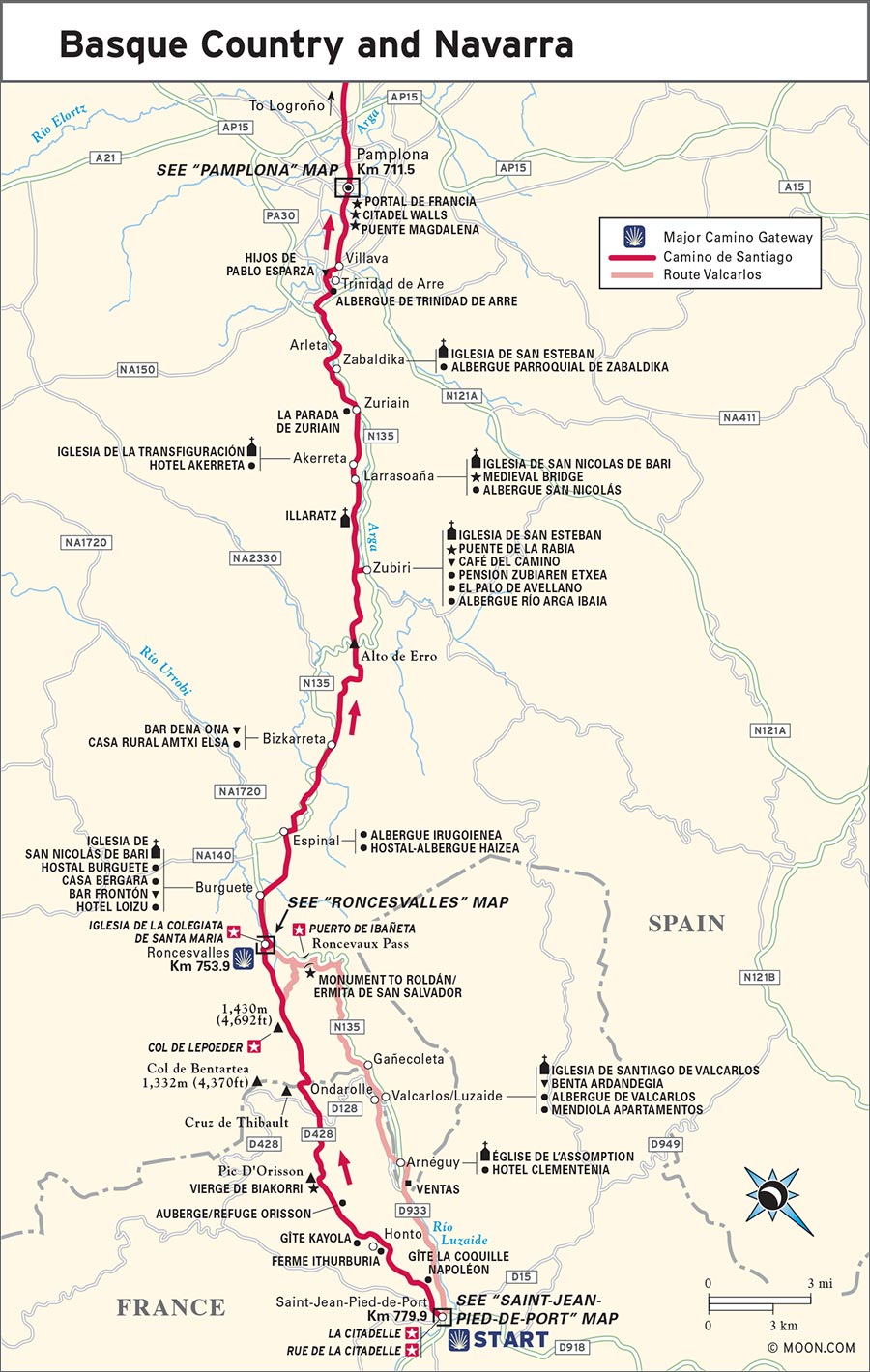

Right off the bat, you have two choices for routes leaving Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. The Route Napoleon (open Apr.-Oct. and at its best mid-June to mid-Sept.) is the most popular route, celebrated for its high vistas that are some of the Camino’s most beautiful views. The Route Valcarlos, the winter route, is open all year, but is also to be taken only if weather permits, as it too has treacherous sections not advised in heavy rain or snow.

a citril finch in Navarra

pilgrims on the path to Espinal

trail marker after Zubiri

Because the Route Valcarlos is considered the “safer” route, there is a misconception that the Route Napoleon is harder, and therefore “better.” The Route Valcarlos is not necessarily easier: the path ascends slowly at first, then climbs up and down on narrow footpaths, some along the edge of the mountain highway and some skirting the steep mountainsides. It also has one dramatically steep and persistent 7.6-kilometer (4.7-mile) climb from Gañecoleta to Puerto de Ibañeta. The Route Napoleon makes a higher elevation climb than the Route Valcarlos, peaking at Col de Lepoeder (1,430 m/4,692 ft), where it then makes a steep descent to Roncesvalles. From the Col de Lepoeder, you have two possible paths: The steepest is straight ahead (4 km/2.5 mi long and only advised when the trail is dry), while a path to the right leads to Puerto de Ibañeta, where it joins the Route Valcarlos to continue into Roncesvalles (a total of 5.6 km/3.5 mi).

The two routes are almost the same length: Route Napoleon is 24.7 kilometers (15.3 miles) long (or 26.3 km/16.3 mi, if you take the final path to the right to Puerto de Ibañeta), and the Route Valcarlos is 24 kilometers (15 miles) long. Both route options are well marked (with red and white parallel stripes in France, and yellow and blue scallop shells and yellow arrows in Spain), except for a 2-kilometer (1.2-mile) section in the final 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) of the Route Valcarlos.

Regardless of which route you choose, pilgrims who decide to begin at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port set before them one of the hardest days of trekking on the Camino. This is one of the Camino’s steepest and longest ascents—and it is on the first day, when pilgrims, even those who trained in advance, are not yet acclimated. Remember to take it slow and steady. Even if you have trained for this, the Camino’s lesson (and its challenge) is endurance and perseverance, not speed. A good idea is to break the first day, the Pyrenean crossing from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port to Roncesvalles, into two days, spending one night midway up into the mountains, either in Orisson (7.6 km/4.7 mi. after Saint-Jean) if taking the Route Napoleon, or in Valcarlos (if taking the Route Valcarlos).

On the Route Napoleon, you cross from France into Spain at Col de Bentartea. If you take the Route Valcarlos, you’ll cross from France into Spain after Arnéguy (Km 771.5). Because both France and Spain are members of the western European Schengen Area, there are no passport border controls; you will simply walk across the border.

On the Route Napoleon, after you leave Orisson, there is no support until Roncesvalles, over 18 kilometers (11.2 miles) away. On the Route Valcarlos, after the town of Valcarlos there are no support structures until Roncesvalles, over 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) away. Stock up in Orisson or Valcarlos on both water and food.

After the two routes rejoin in Roncesvalles, the Camino enters rolling foothills and dense forests, weaving its way to Pamplona. Near Zubiri, the forested trail gets very rocky. This is a point at which many pilgrims are tired, nearing Zubiri as their final destination for the day, so it is a good time to slow down and step carefully.

Average temperatures in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port are in the range of 3°C (37°F) in winter to 27°C (80°F) in summer. But weather in this foothill town is not an indication of weather on the high mountaintops: The higher-altitude portions of the climb over the Pyrenees can plummet to below freezing nearly any time of year, and at times in the summer can exceed 30°C (86°F). The Route Napoleon can get freezing rains, dense fog that blocks visibility, and, in the late spring, even snow. Take the weather seriously, and inquire with locals at the Pilgrims’ Welcome Office before leaving Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. Pilgrims have been injured, and have even died, by pushing ahead on the higher route in inclement weather.

The Route Valcarlos is used in winter and during bad weather, but even that route warrants caution. Heed local advice. If the weather is bad and you can’t wait for it to clear up, be prepared to take a taxi to Roncesvalles, which you can share with other pilgrims to defray the cost (around €55 for the 45-minute drive).

An average of 12 percent of pilgrims begin in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, the contemporary Camino’s official starting point. Roncesvalles is another common starting point, and allows you to skip the rigorous mountain crossing from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, which can be treacherous in bad weather.

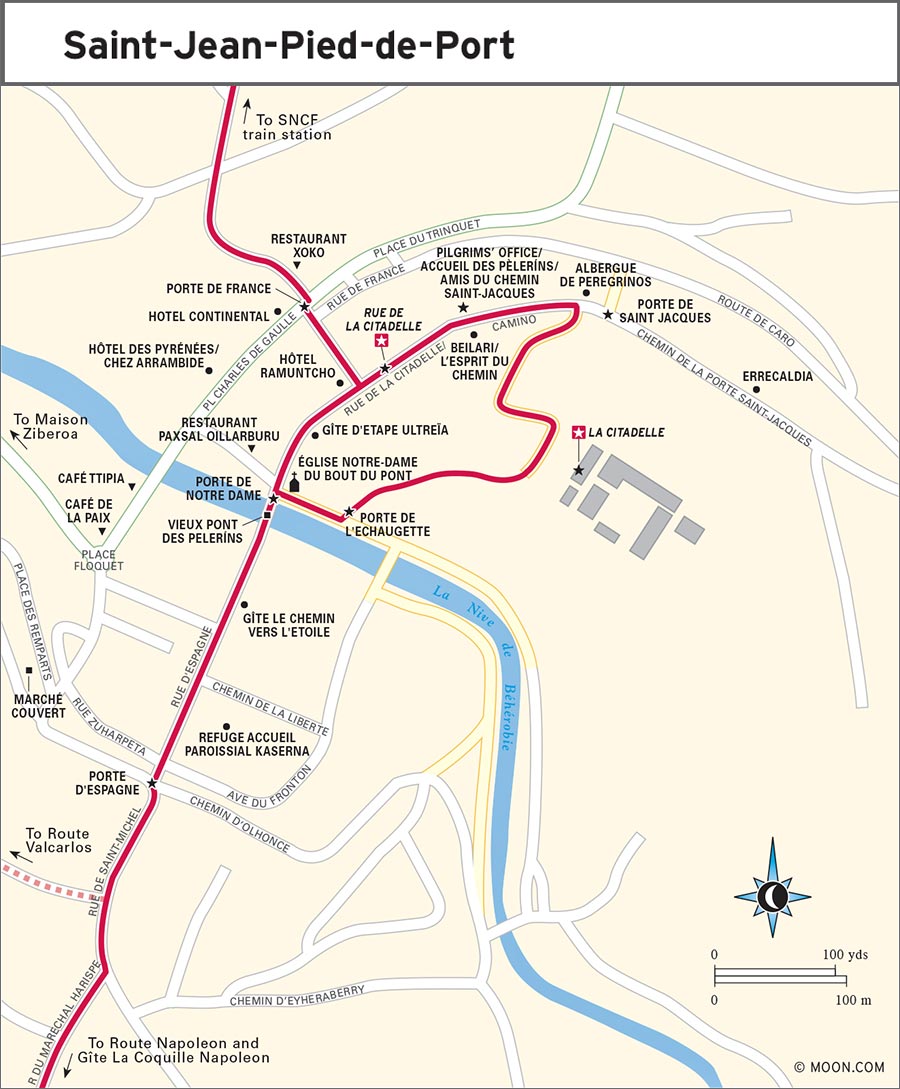

Rue de la Citadelle, Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

Both Saint-Jean and Roncesvalles have transport networks via train, bus, shuttle, and taxi—expressly for getting pilgrims to their desired starting point—despite the fact that both places are far from urban hubs and nestled in rugged foothills.

If driving the Camino from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port or Roncesvalles, the best airports to fly into and rent a car are Bilbao, San Sebastian, and Biarritz.

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port connects to Roncesvalles via the mountain road D933 in France, which becomes the N-135 after you cross into Spain. (You will rarely find any passport control stopping you at the border of France and Spain, and the only indications you’ve crossed the border will be a road sign welcoming you to Spain and the change in the naming of the road you are on.) The D933 in France/N-135 in Spain passes over the Pyrenees and runs parallel with the Route Valcarlos. After Roncesvalles, continue on the N-135, driving southwest, which follows and parallels the Camino de Santiago all the way to Pamplona.

The most common international entry points to reach the Camino are Paris—at both Charles De Gaulle Airport (CDG) and Orly Airport (ORY)—Madrid Barajas Airport (MAD), and Barcelona El Prat International Airport (BCN), with connecting flights to Bilbao Airport (BIO), Pamplona Nóain Airport (PNA), and Biarritz Parme Airport (BIQ), the nearest airports to Roncesvalles and Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

Express Bourricot (661-960-476, www.expressbourricot.com, €19-220, based on distance and number of passengers) runs shuttles from the Biarritz, Bilbao, and Pamplona airports to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Roncesvalles.

SCNF (892-353-535, www.oui.sncf) efficiently connects trains from Paris to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, with changes in Bordeaux and Bayonne. From Madrid and Barcelona, RENFE (902-240-505, www.renfe.com) goes as far as Pamplona, where a bus, shuttle, or taxi can deliver you to Roncesvalles or Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

ALSA (902-422-242, www.alsa.com) connects Madrid and Barcelona to Pamplona, and Pamplona to Roncesvalles and Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. Autocares Artieda (www.autocaresartieda.com) runs buses between Pamplona and Roncesvalles.

Taxi Urolategui (948-790-218 or 636-191-423, €55-100) is based in Valcarlos, with service between Pamplona, Roncesvalles, and Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

After 1177, the year Richard the Lionheart (1157-1199) destroyed the older pilgrim town of Saint-Jean-le-Vieux, locals rebuilt here, nearer the foot of the Pyrenees—hence the name, pied de port, foot of the pass. It was a strategic move, a more protected place and higher up where they could see marauders before they were at the town walls.

The new Saint-Jean (called Donibane Garazi in Basque, pop. 1,600) has splendid enclosing walls built of earth-red schist, like all of the town’s buildings. They wrap around the medieval town and mark it out well for arriving pilgrims, creating a physical container that is rich with spiritual energy. Just walking along its ancient passageways and climbing up to its citadel, which overlooks and protects the town, naturally transports you to the Middle Ages—but with all the modern advantages of great food and hot showers.

When pilgrims coming from destinations across France and Europe passed here on their way toward the Pyrenees and Spain, it would have been an emotional moment: Many had been on the path for days and weeks already, but the mountains they were about to climb were famous for making or breaking a pilgrim. If they made the passage, they had a good chance of getting to Compostela. If they did not, no gate of pardon would free them of their mortal burdens.

Over the centuries, this small French town has received millions of pilgrims arriving on foot, and its layout is built for pedestrians. These medieval pilgrims would have passed by the older settlement of Saint-Jean-le-Vieux, and then entered Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port via the Porte de Saint Jacques. This then leads straight onto the Rue de la Citadelle, the road on which millions, and by now billions, of feet have passed, for over 900 years—all sharing the same purpose as you now, to walk the Camino over the Pyrenees and into Spain.

Modern pilgrims coming from roads in France still take this same approach. The vast majority arrive by train, and from the station, it’s an easy 10-minute walk through the modern town to the Porte de France, which accesses the medieval walled town from a side gate on the lower end. Inside, you will readily find the Rue de la Citadelle—it defines the central spine of the walled settlement—and discover the church straight ahead, the bridge to your right, and the rest uphill and to your left and right. If you’re arriving in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port by taxi, ask your driver to drop you off in town at the top road of the citadel to experience the town as pilgrims of yore did.

More recent than the walled town below it, La Citadelle (559-370-092, www.saintjeanpieddeport-paysbasque-tourisme.com/citadelle) was built for defense in 1628 and rebuilt by military engineers in 1680. The Citadelle building itself is closed to the public—it is now a school—but the extensive surrounding grounds are free to access and an open-air sight that’s open all day (dawn to dusk) but gated off at night. The highest point in Saint-Jean, the site offers impressive views, not only of the town below, but also of the deep folds of foothills and river valley and of the steep sloping vineyards on the other end of Saint-Jean. For the best views, climb to the lookout platform located at the high point of the citadel walls. Someone has fastened a dream catcher to the railing there, a lovely reminder that many who come here are riding on hopes and dreams.

Access to explore the outer walls of the citadel has two paths. One is uphill, on the Rue de la Citadelle, near the Porte-St-Jacques. I prefer the other because it aligns you to descend from the citadel and enter Saint-Jean the way medieval pilgrims did, passing through the Porte de Saint Jacques. This path is accessed via the footpath along the river Nive. Go past the Église de Notre-Dame du Bout du Pont, through the arched gate, and approach the bridge, but don’t cross. Instead, make a left and go about 20 meters (66 feet) along the river, where to the left you’ll see an iron gate, called the Porte de l’Echaugette, that leads to steep steps going up. Climb these steps to the path that traces the upper wall of the old town. From here, you’ll see the Église de Notre Dame below you, a great perspective on the back side of this red stone Gothic church. Continue on the path toward the top of the citadel walls. The path then wraps around the walled citadel grounds and exits at the top of Rue de la Citadelle, next to the Porte de Saint Jacques. The full circuit will take about 20 minutes to complete.

Porte de Saint Jacques (Saint James’s Gate), a delightful arched passage of dark red stone, enters Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port from the east, bringing in pilgrims from three of the four main roads in France that merge a few kilometers before here to cross the Pyrenees at the Cize/Valcarlos pass ahead. This feels like a natural threshold, stepping through this gate and into the footsteps of medieval pilgrims arriving from across France. It also sets you at the top of the steep Rue de la Citadelle, the street that cuts through the medieval town, with great views of the old town below.

When you step onto this road, you are officially stepping onto the Camino as it enters and passes through the first half of medieval Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. Here, it may be that for the first time you will feel the reality that you are now following in the footsteps of countless thousands of other pilgrims who have come to this town over hundreds of years to walk the Camino. Seeing and feeling the timeworn cobblestones underfoot can be emotional: it is as if pilgrims have left energetic postcards between the stone cracks to cheer you forward on this amazing adventure. Slow down and really savor it.

The Rue de la Citadelle is also the road along which the vast majority of pilgrim albergues (auberges or gîtes in French) in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Portare are arrayed, as is the all-important office, Accueil des Peleríns (Pilgrims’ Welcome Office) of the Amis du Chemin Saint Jacques, where you can get your credential (€2), as well as all the advice and enthusiasm you need.

Rue de la Citadelle naturally descends down the hill toward the ancient church of Notre-Dame du Bout du Pont, the dark red schist stone church of Our Lady. This is the spot of the original church building that was constructed soon after 1177, though this particular structure dates to the 13th and 14th centuries. It has a strong Gothic style but with quirky details, such as especially expressive carving in the entrance door’s pillar capitals (look for the two women who look like best buddies and seem to watch your every move). The inside feels more intimate, maybe because of the warm red stone. The church can get busy, with tourists popping in during the late morning and early afternoon, but returns to its role as a quiet sanctuary in the early evening and early morning. During those times, it is a pleasure to come here and perhaps light a candle to shed light and blessings upon your forthcoming pilgrimage over the Pyrenees. Daily mass is typically offered at 10:30am.

Vieux Pont des Peleríns (Old Pilgrims’ Bridge) is the picturesque and often photographed bridge over the river Nive that all pilgrims pass over. As you approach it from the Rue de la Citadelle, with the church of Notre-Dame du Bout du Pont to your left, look up over the gate, called the Porte de Notre Dame, to see a sculpture of Saint-Jean’s namesake, Saint John the Baptist. After you pass under it and cross the river, stop and turn around to see the other side, this time, of a wooden sculpture of Mary, Notre Dame du Bout du Pont, in the overhead niche.

Many pilgrims take turns taking pictures of each other crossing this bridge, a ritual moment of stepping foot into the great transformative journey ahead.

The old pilgrims’ bridge leads to another momentous threshold, Porte d’Espagne. This gate at the far end of the medieval town is your exit from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and your entry onto the full Camino before you: It is 779.9 kilometers (484.6 miles) from here to Santiago de Compostela. Not as elaborate as the Porte de Saint Jacques, the passage is marked by two thick square pillars. But just before passing through, you step over a black-and-white stone inlay of a massive scallop shell, the symbol of the Camino.

While there is no true official starting point of the Camino—traditionally, it is from your front door when you set off on the Camino—this feels like the official threshold. Once you step off from here, you are entering your destiny on the Way of Saint James, an ancient route taken by hunters and gatherers, herders, Romans, Charlemagne and Roland, Napoleon’s troops, and countless millions of pilgrims for over one thousand years.

This pilgrim town is full of great little restaurants, some that are more oriented toward the river and hidden from the street. Wander around and follow what pulls you in. Be sure to try the local cheese, the creamy but firm sheep’s milk Ossau-Iraty AOC (appellation d’origine contrôlée, protected name of origin), and the wine unique to this little region, Irouléguy AOC, which is produced in white (10%), rosé (20%), and red (70%) varieties.

S Café Ttipia (2 Place Floquet; 559-371-196; www.cafettipia.com; €15-20) is a classic French brasserie elevated with the fresh and colorful flavors of southwestern French and classic Basque cuisine, such as spring greens salad with almonds and port-poached foie gras, grilled lamb with red peppers and salad, and the gabure maison (the house-made, rich vegetable stew of this part of the Pyrenees). Dining is at long wooden communal tables, assuring you’ll fold in to local life and cheer. Local Irouléguy wines and Ossau-Iraty cheeses are on hand to try.

S Restaurant Paxsal Oillarburu (8 Rue Eglise; 559-370-644; €15) is the place to come for trout, grilled and seasoned with Espelette, the special red pepper grown in the region and named after the central town of Espelette, 37 kilometers (23 miles) northwest of Saint-Jean. Also try the piquillos, the confit de canard (duck confit), and the grilled squid with peppers. A warming fire roars in the fireplace on cold nights, and outdoor café tables splay on the terraced sidewalk on warm days.

Restaurant Xoko (1 Place du Trinquet; 559-373-935; €12.50-15) has morning-to-evening good eats, from full meals to just coffee or a glass of wine. Try the café gourmand, the gourmet coffee, that comes with an array of small tastes of various desserts with an espresso. The menu includes a selection of salads, grilled plates and charcuterie, and omelets, with specific offerings changing each day based on market finds.

Restaurant Xoko and the town center of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

Café de la Paix (4 Place Foquet; 559-370-099) has well-priced offerings with a solid daily menu (€12.50) that includes local specialties such as red pepper-spiced sausages, hot goat cheese salad, and thin-crust pizzas. Locals come here as much as visitors, and each time I’ve been here, the service has been impeccable and amicable.

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port has a lot of accommodations, most of them very good—and not all of it just for pilgrims, as this is also a popular holiday destination for Spanish and French trekkers as well as food and wine lovers. Most of the pilgrim albergue-style accommodations are in the old walled city, and the hotels are all around town outside the medieval walls.

If you land here without a place to stay, head first to the Pilgrims’ Welcome Office of the Amis de Chemin Saint-Jacques (39 Rue de la Citadelle), where they will help you find a bed. I’ve seen them work miracles over and over, dealing with “no rooms at the inn” and other situations that seemed unsolvable, and landing everyone a good place to stay. Here are some favorites, popular with many—and so it’s a good idea to book ahead.

Errecaldia (5 Chemin de la Porte St-Jacques; 559-491-702; www.errecaldia.com; €55-75), right across from the upper street passing the Citadelle and just outside the medieval walls above the Porte de Saint-Jacques, is a traditional home from 1673 that two local transplants from England, Tim and Louisa, have turned into a splendid B&B with three rooms with ensuite bath and a delicious breakfast including local breads, cheese, and ham.

The municipal Albergue de Peregrinos (55 Rue de la Citadelle; 617-103-189; open all year; 32 beds in three dorm rooms, €10 including breakfast) takes no reservations—just show up and see if there is a bed in this traditional stone, stucco, and wood-beam town home with solid wood bunks.

S Beilari, also known as L’Esprit du Chemin (40 rue de la Citadelle; www.beilari.info; 559-372-468; open Mar.-Oct.; 18 beds in three dorm rooms; €33 for a bed, dinner and breakfast) is right across from the Pilgrims’ Office. Josef and Jakline, who speak English, offer the sincere welcome of those who honor the deep spirit of the pilgrimage and you as an honored guest. Reservations are recommended and can be easily done online via email. A name card (if you reserved ahead) and a candy rest on the stack of clean sheets, blanket, and pillow of your assigned bunk. After the generous vegetarian dinner, the hosts guide guests through a moving ritual that frames and celebrates the pilgrimage ahead. You can arrange a packed lunch for the next day (€5).

Gíte d’Etape Ultreia (8 Rue de la Citadelle; 680-884-622; www.ultreia64.fr), which opened in 2009, is run by an experienced and passionate hiker who wants others to experience living in a well-restored traditional home as if it were their own. Available are two dorm rooms with both bunk and single beds (11 beds total; €16-17) and two private rooms (€44-48). Breakfast is €5, and there is also a communal kitchen for guests’ use. Proprietor speaks English.

The Refuge Accueil Paroissial Kaserna (43 Rue d’Espagne; 559-376-517; 14 beds in two bunkhouses) is a parochial albergue, run by the Diocese of Bayonne, a simple, basic, and clean place that is open Apr.-Oct. A donation of €15-20, which includes the very good communal dinner and breakfast, is suggested for those who can afford to pay. You’ll find this albergue to the left on the Rue d’Espagne as the Camino makes its way out of the old city and toward the Cize Pass.

A few steps outside of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port on the Route Napoleon (to your right after you pass the Porte d’Espagne), you can find the Gîte La Coquille Napoleon (Route Napoleon; 662-259-940; www.lacoquillenapoleon.simplesite.com; 10 beds in one bunkhouse for €20 and two private rooms, each for €48), a pretty white-and-red-trim country house with a very warm welcome. Communal dinner is €12, and breakfast is €4. Bunk beds are built into the wall, each with its own window, a luxury dorm bed on the Camino. A backyard porch with a long dining table makes for an enchanted gathering place.

Gîte le Chemin vers l’Etoile (21 Rue d’Espagne; 559-372-071; www.pelerinage-saint-jacques-compostelle.com; 46 beds in five dormitories; €17-20) has a winding staircase with mezzanine view to the ground floor in this traditional home from 1580 that was turned into an auberge in 2009. Shared rooms range from having several beds to as few as two or three beds. For €12, you can dine in for the evening meal. Ask also for their packed lunch to take with you onto the trail, for an additional €5-7. Proprietors speak English.

Looking out on the outer walls of the old city, Hotel des Pyrénées (19 Place Charles de Gaulle; €180) is a high-end luxury hotel worthy of a honeymoon, with engaging and attentive staff who speak English. The traditional building harbors elegant contemporary rooms and a private back-garden pool. The hotel restaurant Chez Arrambide creates dishes that are as beautiful as they are tasty, with the vibrant colors and flavors of local produce, made with both modern and postmodern techniques (including foams)—but, like the hotel, they are truly not for the budget minded: A tasting menu begins at €110.

Hotel Ramuntcho (1 Rue de France; 559-370-391; www.hotel-ramuntcho.com; 16 rooms; €75-100) is the place for central location and comfort. It is a traditional Basque building with modern comforts and amenities, a private courtyard garden, view of the rooftops and mountains, and central location on the Rue de la Citadelle. The staff engagement is less personal and more like what you would find in an international chain hotel, compared to the more personable pilgrim gîtes and albergues on the street. They run a good restaurant, with a street-side terrace café that is a delight to sit in and watch the old town.

A few paces from the western outskirts of the old city is the delightful Maison Ziberoa (3 Route d’Arneguy; 661-235-944; www.ziberoa.com; four rooms; €65-80; dinner, €24), with crisp bed linens and plush beds, large windows opening onto the countryside, and rooms painted in soft but saturated colors, like the interior of a classic French country farmhouse. The large walled garden has a stand of wisteria that acts as a natural parasol over reclining chairs. Guests get to dine in with home cooking, including piquillos, French lentil and carrot casserole, and roasted white asparagus. Proprietors speak English.

The Hotel Continental (3 Avenue Renaud; 559-370-025; €65) has to be mentioned, for this is where Tom (Martin Sheen) stayed in the 2010 movie The Way. But it is not a luxury hotel: It is in need of a make-over, but still charming (for its enthusiastic, rugby-loving owner). In fact, it is in every way what it appeared in the movie: old-fashioned, basic, and informal. I mention this here for those nostalgic peregrinos dedicated to visiting sites found in the movie.

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port is best reached by train via Bayonne, where the trains from Paris, via Bordeaux, connect to Saint-Jean. If you want to fly to the nearest airport and arrange a shuttle, Biarritz is the nearest airport in southwestern France. You can also take a shuttle, bus, or shared taxi from Pamplona.

One of the most direct ways to get to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port is to fly into Paris with a connecting flight to Biarritz (www.biarritz.aeroport.fr). The shuttle service Express Bourricot (31 Rue de la Citadelle; 661-960-476; www.expressbourricot.com; cash only) picks passengers up at Biarritz’s airport and takes them directly to the Pilgrims’ Office in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (about 1 hour, €19-84, depending on number of passengers in the shuttle). You can arrange a similar pickup from Bilbao and Pamplona’s airports and train stations via Express Bourricot to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Roncesvalles (around 2.5 hours from Bilbao and 1.5 hours from Pamplona, €20-220). The prices of these shuttles vary based on distance and how many passangers are in a shuttle. As such, it is a good idea to inquire ahead about the price and schedule via the contact page on the website, where you can also book your ride.

Rent-A-Car has an agency in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (Route de Bayonne, Garage DTH; 559-507-060; www.rentacar.fr), with other offices in Biarritz and Bayonne.

From Santander (291 km/181 mi; 3.5 hours), where ferry passengers arrive, take the S-10 south and A-8 to AP-8, past Bilbao, east to the border at Irun and Hendaye, and continue on the A-63 south of Anglet; exit onto D-932 southeast and follow D-918 to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

Similarly, from Bilbao (192 km/120 mi; 2.5 hours), take AP-8 east to the border at Irun and Hendaye, then A-63 south of Anglet; exit onto D-932 southeast and follow D-918 to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

From Pamplona (75 km/47 mi; 1.5 hours), take the N-135 north to Roncesvalles and continue to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port via Valcarlos. The N-135 becomes the N-933 in France.

From Bordeaux (235 km/146 mi; 3 hours), exit south to Bayonne on the A-63; after Bayonne, take the D-932 and D-918 to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

From the airport in Biarritz (53 km/33 mi; 1 hr.), take D-810 southwest to D-932 and D-918 to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

SNCF (892-353-535; www.oui.scnf) runs trains from Bayonne (five trains daily; 1.5 hours; €11) to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, which is the train line’s last stop. From Paris, you can buy your ticket for the whole journey; you will change trains in Bordeaux and in Bayonne to reach Saint-Jean. Note that Paris’s Charles De Gaulle Airport (CDG) has its own SNCF train station and has one daily departure directly for Bordeaux, so if you get on one of these, you won’t have to go into Paris. The whole trip, from CDG to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (€180-200), will take around 8 hours, including the time to change trains in Bordeaux and Bayonne. All other trains depart Paris’s Montparnasse Station, also with train changes in Bordeaux and Bayonne (three daily; 6.5-7 hours total, including train changes; €124-180).

RENFE (902-240-505; www.renfe.com) runs nine daily direct trains from Madrid to Pamplona (3-4 hours; €46-60), from where you will need to catch a bus, taxi, or Express Bourricot shuttle to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

If you take the train from Bayonne, the most common way pilgrims get to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, the ride is a part of the magic—not only for the landscape, but also for the camaraderie of other pilgrims, as well as locals (this is a commuter line). By the time you disembark, you may already have found members of your “Camino family.” The train will deposit you at the town’s train station, a 5-10-minute walk from the north side of town into the center to the Porte de France, the gate into the medieval walled town. Signs from the station will direct you to the historic center, where most of the accommodations are.

ALSA (www.alsa.com) connects Pamplona to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (3-4 buses daily; 2 hours; €22) with a stop in Roncesvalles. ALSA also runs from Roncesvalles to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (three buses daily; 45 min.; €5).

A taxi from Pamplona to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (1.5 hours) costs around €110-120. Taxi Goenaga (559-370-500) and Taxi Maïtia (683-946-932) are both based in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

Before you leave, check with the pilgrims’ office about the weather conditions and which path—the more popular Route Napoleon up the mountain, or the Route Valcarlos, used during bad weather and in winter—they recommend that day. Both routes are accessed after you leave the walled town through the Porte d’Espagne. Soon after passing this gate, signs will direct you ahead on the Route Napoleon (24.7 km/15.3 mi) and to the right toward the Route Valcarlos (24 km/15 mi).

Be sure also to stock up on food and water before leaving Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, whichever route you decide to take. On the Route Napoleon your last place for food and water before reaching Roncesvalles is in Orisson, 7.6 kilometers (4.7 miles) after Saint-Jean. On the Route Valcarlos, there are only two places to refuel on the 11.7-kilometer (7.3-mile) stretch between Saint-Jean and Valcarlos: a shopping complex called Ventas (7.4 km/4.6 mi. after Saint-Jean) and the town of Arnéguy (8.4 km/5.2 mi after Saint-Jean); and Valcarlos is the last place to stock up on food and water before reaching Roncesvalles (a 12.3-km/7.6-mi stretch).

Both routes have historic roots and pass through the Cize Pass, the easiest pass to traverse on the western side of the Pyrenees. In Roman times this was a part of the Via Traiana, the road that began in Bordeaux (Roman Burdegala) and went over the mountains, continuing across the north of Spain to connect to the mines at Astorga. The Romans preferred the higher, mountaintop Route Napoleon, which allowed them to see all around and which reduced the risk of being ambushed by marauders. (Down in the valley, the Route Valcarlos had many places where bandits hid, preying upon vulnerable pilgrims, as the Camino grew in popularity in later centuries. Today, the only safety concerns on the Route Valcarlos are the stretches where you have to walk on the mountain road—watch for cars!) Historically, the valley route had the advantage of better access to water and food, and was the path Charlemagne (Charles the Great) took to return to France in AD 778; this is why Valcarlos—Carlos’s Valley—is named after him.

Considered the recommended route in good weather, and only open April- October, this path is largely recommended for its departure from major roads and its breathtaking mountaintop views. If you embark on the Route Napoleon on a sunny day, you will be rewarded with those promised views of the Pyrenees mountains stretching in layers to the ends of the horizon, hawks and griffins circling the sky, and white and black sheep dotting the green slopes. But if you embark on an overcast day, chances are good that once you ascend to the first high point, at the Pic D’Orisson and Vierge de Biakorri, you will have your head quite physically in the clouds and will see nothing but the trail just a few feet before you. In this case, keep vigilant to stay on the trail and look for way-markers. Your best view will be from the highest point, the second highest on the whole Camino, at Col de Lepoeder, and then 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) later, arriving at Roncesvalles, the monastery complex promising warmth and food.

A good strategy for this ascent, if the weather is iffy or if you want to break up the trek into two days, is to reserve ahead at one of the two auberges (albergues) on the mountain, in Honto or in Orisson (the larger and more popular of the two). Both lodging options are pretty much all that there is, but they offer gorgeous views of the mountains.

The path will veer slightly left as you depart Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and follow the D428 uphill to Honto.

In Honto (also spelled Huntto) you have views of both the town of Saint-Jean nestled at the foot of the mountains below, and of the mountains before you yet to traverse. Honto essentially consists of one traditional farm house, which is open for lodging (and for dinner and breakfast, for those staying there).

climbing to La Citadelle in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

Refuge Orisson

the view from Honto

Ferme Ithurburia (on D-428 through Honto; 559-371-117; www.gite64.com/ferme), a farmhouse to the left of the road in Honto, offers private rooms in its Chambre d’Hôtes (€55) for up to 14 people, and beds for up to 22 people (€16) in its Gîte. The evening meal is €20. Proprietors speak English.

A dirt path just after Honto will lead you left off the D428 for 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) and then will return to the D428 just before entering Orisson.

Orisson consists of the refuge serving pilgrims, and it is your last settement before reaching Roncesvalles.

Jean-Jacques Etchandy runs both the Refuge Orisson and the Gîte Kayola (559-491-303; www.refuge-orisson.com; both open Apr.-mid-Oct.), the only structures in Orisson. Both are on the Camino’s path, which continues on the D428. The Gîte Kayola appears first, to the left of the road. Kayola is intended for pilgrims desiring just a bed (15 beds in one dorm room; some beds are single beds; €15), not dinner or breakfast, in a small country abode with a shared kitchen where you can prepare your own dinner and breakfast. It also has a rustic common room with dining table and fireplace, but you can opt to use the bar-restaurant attached to the Auberge Orisson for drinks, snacks, and meals (at extra cost). Just let Jean-Jacques know you will be there for dinner so he can add a plate.

Eight hundred meters (0.5 miles) onward after Kayola is the Refuge Orisson, which straddles both sides of the road, and is for those seeking dinner and breakfast as a part of their accommodations. The rate (€36) includes your dorm bed, communal dinner, and breakfast the next day. For another €4-5 (make sure to request it the day before), you can secure a packed lunch to take on the trail—a good idea if you have not brought your own provisions, as after Orisson, there are no places for food until Roncesvalles. You check in upon arriving at the Refuge Orisson restaurant, the building on the right as you hike in, where you will be assigned your bed and where you can order lunch for the next day. The pilgrim dorms are on the other side of the road and trail, on your left as you enter Orisson, hugging the steep slope of the mountainside. Some of the Refuge Orisson dorm rooms are a bit tight, with too many bunks packed in, but still it is a spotless place with decent bathrooms. The location and the communal dinner are the highlights. Enjoy locally procured produce and products and classic Basque French home cooking—the coq au vin is a specialty.

Before leaving Orisson, be sure you fill your water bottles and stock up on food for lunch: There are no other guaranteed places for food until Roncesvalles, over 18 kilometers (11.2 miles) ahead. For water, you will have the option to refill bottles at the pilgrims’ fountain, Fontaine de Roland (Roland’s Fountain), 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) past Orisson near the French-Spanish border at Col de Bentartea peak.

From Orisson, continue walking on the small D428 mountain road for another 8.8 kilometers (5.5 miles). In 3.8 kilometers (2.4 miles), you will reach the Pic d’Orisson.

Pic D’Orisson (1,095 meters/3,593 feet), the first summit after Orisson, is most famous for its ceramic Mary statue, called the Vierge de Biakorri (Biakorri Virgin) or Vierge d’Orisson, that is mounted on the top of a pile of rocks at the highest point. She stands just to the left of the trail, and if a fog descends, it will be easy to miss her. Two decades ago, the stand of stones on which she rests was split in half by lightning, but the statue held firm and was unharmed. The stones and the statue of the Vierge de Biakorri make for a picturesque outdoor shrine, with flower offerings from locals tucked near her feet. She is known as the Vierge de Bergers (Shepherds’ Virgin), an important patroness and protector of shepherds and their sheep, as well as of all who pass here on this climactic mountaintop.

If you happen to be here on the Sunday after August 15, you will see locals dedicated to Mary’s grace making a pilgrimage to this point to attend a mass that is held here once a year. A local priest began the tradition in 1995 after lamenting that shepherds in his parish could rarely make it down the mountain to attend mass. The date of the pilgrimage in August commemorates Mary’s Assumption (her body and soul ascending to heaven).

At 3.6 kilometers (2.2 miles) after Pic D’Orisson, a crucero (standing crossroads crucifix) known as Cruz de Thibault marks where the path veers to the right and off the D428 road onto a rocky dirt path. From this fork, in another 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) and on the left side of the trail, you will pass the Fontaine de Roland (Roland’s Fountain), named in honor of Charlemagne’s officer who, according to legend, died in these mountains. If you need water, fill up here: It’s another 8 kilometers (5 miles) to Roncesvalles. In a few meters, at the peak of Col de Bentartea (1,332 meters/4,370 feet, Km 763.3), you will cross the French-Spanish border. The next 3.8 kilometers (2.7 miles) from the Col de Bentartea to Col de Lepoeder are a steep but final climb.

Top Experience

At 1,430 meters (4,692 feet), this is the highest peak of this crossing and the second highest peak of the whole Camino (the highest is Monte Irago, in Leon, at 1,515 meters/4,970 feet). The views afforded here are expansive and revealing of the geology of the Pyrenees mountains. It is exhilarating to see all of Spain sweeping before you and France behind you, the steep jutting green-gray-blue mountain peaks capped with snow or dotted with herds of cream-colored sheep, and griffon vultures with nine-foot (274-cm) wingspans riding air currents overhead. Equally exhilarating may be the fact that you can see the huddled rooftops of Roncesvalles, signaling that you are almost there.

Although you’ve reached the apex, the hardest part of the hike is to come: the steep descent. Thankfully, here you have a choice of two possible trails, both marked. If you wish, you can continue straight ahead on the Route Napoleon down a sharply steep hillside, a task that should only be undertaken with strong knees, no rain, and a dry trail. It is this one descent that causes the bulk of injuries for pilgrims, all too early on their Camino. If you take this path, another 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) remain to reach Roncesvalles.

Alternatively, you can follow the sign-posted trail to the right from Col de Lepoeder for a 4.3-kilometer (2.7-mile) trek on a gentler, paved path to Puerto de Ibañeta, the pass where Charlemagne’s military guard led by Roland was defeated; here, the trail joins the Route Valcarlos for the rest of the 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) to Roncesvalles. This route adds 1.8 kilometers (1.1 miles) more to the walk, a total of 5.8 kilometers (3.6 miles) from Col de Lepoeder to Roncesvalles. This is a recommended path, not only for the softer slope down, but also the chance to see the views from Ibañeta pass.

Detour: The Route Valcarlos

Detour: The Route ValcarlosThis sublimely beautiful 24-kilometer (15-mile) route is dense with native beech, chestnut, oak, and pine forest, and intimate valley passages along steep cliffs carved out by the Nive river. The Camino follows the river toward Valcarlos and Roncesvalles. It parallels in many places the mountain road D933, as it is called in France, and the N-135, as the same road is called after you cross into Spain—but more often you will be on smaller country lanes or dedicted foot paths. In two places you will have to walk directly on the N-135, as there is no bank: On the 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) before Gañecoleta (Km 765), and a 2-kilometer (1.2-mile) stretch that begins 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) past Gañecoleta. Be cautious of cars, and step carefully to avoid slipping down the steep slope to the river below.

The trail from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port via Valcarlos to Roncesvalles is marked with the French-style red and white stripes, along with yellow signs indicating place names and distances. It is well marked, except for the 2-kilometer (1.2-mile) stretch after Valcarlos, overlapping with the first of two sections where the path has no bank and is on the N-135.

One kilometer (0.6 miles) before the village of Arnéguy, plunked in the midst of wild terrain, you will pass through a somewhat incongruently modern luxury goods shopping complex, Ventas (Km 772.5), a good place nonetheless to do some food shopping at the grocery store, to refill water bottles, or to grab a bite at the café.

Your last settlement in France—truly the last, as it sits right on the border between France and Spain—Arnéguy (pop. 232) is an international zone where you still feel the strong French culture as well as that of the Basques, the Navarrese, the Spanish, and most profoundly, the special mountain mood of people from the heart of the Pyrenees. Many locals speak all three languages—Basque, French, and Spanish—and enjoy welcoming pilgrims to their mountain spot on the pretty banks of the Nive d’Arnéguy river. Neat rows of kitchen gardens and hanging terraces line the water’s edge. Arnéguy’s 17th-century church, Église de l’Assomption, is on the central high spot of the village and is easy to find.

Enjoy the terraces and country inn rooms at the riverside Hotel Clementenia (on the left on the D933 through Arnéguy; 524-341-006; www.hotelclementenia.com; €45-70), which offers nine spotless and cozy rooms. The restaurant serves home-cooked meals, including on-the-spot special requests for vegetarian dishes. Some rooms look out on the river. Proprietors speak English.

Note that the D933 becomes the N-135 as you cross into Spain. (There are no passport or border controls, so you may not even notice the crossing.) The Camino continues to parallel the N-135 after Arnéguy, but you have an alternate option to take a smaller country road just a few meters to the left off the N-135, toward the hamlet of Ondarolle (Km 768.9), less than 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) before Valcarlos. Take this option; it is beautiful and calm, with little traffic, and adds no significant extra distance.

The final 400-meter climb into Valcarlos goes from the river up to the mountainside to the town and is steep and paved. It is surrounded by chestnut trees that drop nuts, making it easy to slip; step carefully to avoid turning an ankle.

Called Luzaide in Basque, Valcarlos (pop. 387) is named for the valley where Charlemagne is thought to have camped in 778, as he and his army retreated back to France after a war campaign in Spain. Valcarlos today is a neat, tiny mountain town steeped in ancient Pyrenees traditions, despite being a thoroughfare from France to Spain. It is also a place where people passionate for hiking, immersion in nature, and trout fishing come for holidays. The narrow Nive River valley offers respite and retreat all around you.

Monument to Roldan at Puerto de Ibañeta

In the Middle Ages, Valcarlos was a pilgrim town with a medieval hospital and church, neither of which have survived. The modern town church, Iglesia de Santiago, stands on the highest point on the road that cuts centrally through town. You will most likely find it locked, but you can ask for the key from the town hall (Ayuntamiento de Luzaide; Calle Elizaldea s/n; 948-790-117; www.luzaide-valcarlos.net), across the street from the church. An interesting modern mural a few paces from the church, on the same side of the street, depicts traditional aspects of Basque culture. In the mural’s foreground, a man in a traditional Basque red-and-white shirt and trousers walks toward a pilgrim with a staff, with the hilly green countryside and Valcarlos’s church sweeping down behind them. Most intriguingly, in front of the painted church are three women and a dancing bullheaded creature, all of them circling a large bonfire. This image is similar to one by the famous 18th-century Spanish painter, Francisco de Goya, who is known for for his paintings on brujería (witchcraft). Both Goya and this muralist drew inspiration from the older source of local folklore, which held that witchcraft was not a dark force but a positive healing force. This mural feels like a celebration.

The rivers of the Pyrenees are full of trout, but it was the streams crossed by the Camino that drew Hemingway. Many restaurants in the area feature the fish, but few capture the panache of Valcarlos’s pub, restaurant, and grocery store, S Benta Ardandegia (Calle Elizaldea, 15; 948-796-002; www.ardandegia.com), a one-stop shop for all food needs. Come here for a three-course menú (€10, including local trout and Ossau-Iraty sheep’s milk cheese), a drink with fellow pilgrims and locals, or to do your grocery shopping: just-picked produce, regional food products, or a freshly baked loaf. The staff is determined to make their customers happy and the chef is a master, turning an ordinary daily menu into a gastronomic adventure, including thick grilled steaks, vibrant fresh garden salads, and homemade desserts—including the classic yogurt-like custard, cuajada, served with local honey. But it is her trout, caught fresh and fried with cured ham, that tops the list. The grocery store stays open as long as the bar and restaurant are open, and this can be late into the night. Come here for the trout, stay for the society.

the village of Arnéguy

sheep on the cliffside in the village of Gañecoleta

stone honoring Our Lady Roncesvalles at Ermita de San Salvador

The municipal Albergue de Valcarlos (Plaza de Santiago; 948-790-117; turismo@luzaide-valcarlos.net; 24 beds in two dorm rooms; €10), which opened in 2008, is excellent. Located next to the school, this albergue is small and efficient, with new facilities including a washing machine, kitchen equipment, and sturdy metal bunks—plus a view overlooking the gardens of the river valley you just climbed up from. You will either have to cook for yourself or enjoy the bars and restaurants in town, all of which are an easy saunter up the small hill to the main road.

Mendiola Apartamentos (Calle Elizaldea, 113; 609-755-105; www.turismomendiola.com) consists of six rural apartments in a mountain chalet structure with white walls and dark slate tiles and roof. The owner makes these available for one night and offers peregrinos the chance to cook in a private kitchen in their own space at remarkable prices: While they run around €75, which can be shared with several people, you may be able to get an apartment for €25 in the low season. A bouquet of fresh mountain flowers and herbs on the counter adds a splash of love to the place.

On the 12.3 kilometers (7.6 miles) from Valcarlos to Roncesvalles, there are no places for food, water, or lodging. Be sure to fill water bottles and carry enough food for lunch and snacks. The Camino continues to be marked with a mix of yellow arrows, red-and-white-striped trail markers, and pillars with the blue-and-yellow scallop shell. It leaves Valcarlos following the N-135 south (the sun will rise to your left). Carefully stick to the bank of the road, watching for blind turns and oncoming traffic. About 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) after leaving Valcarlos, trail markers disappear for the next 2-3 kilometers (1.2-1.9 miles), and so does the road bank—you will need to walk on the road itself. Markers will appear more frequently again thereafter, and thankfully will also lead you to the left, off the road and onto a peaceful country path toward the village of Gañecoleta.

Huddled in a narrow dale of the Nive d’Arneguy river, this hamlet (pop. <10) is forgotten by time, with sheep grazing along its steep sides and foot bridges crossing bucolically from one side of the settlement to the other. The path passes through groves, gardens, and dense undergrowth; sunlight barely reaches here, a few hours a day at most, because it is so narrow and steep. Chestnut trees grow densely all around. The dirt trail is narrow in many spots, sometimes with a steep edge. Step carefully. It will often be damp and covered with leaves. More and more, yellow arrows and blue-and-yellow scallop-shell markers will guide you on the trail.

the Route Valcarlos trail through chestnut and beech forest after Gañecoleta

At 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) beyond Gañecoleta, the Camino will return to the N-135 for 2.4 kilometers (1.5 miles): Be very careful on this stretch, as there is little bank and you will be walking on the road itself. The Camino then veers off the road to the left and departs the N-135 for good, to pass on dirt footpaths through wild beech forests. This passage, from here all the way to Roncesvalles, is resplendent with some of the most beautiful chestnut and beech forests anywhere in the north, competing with the forests of Galicia. The entire 7.6-kilometer (4.7-mile) stretch, from here to Puerto de Ibañeta, is also an upward climb; the last 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) are especially steep and relentless

Top Experience

At 1,057 meters (3,468 feet), this is the highest point on the Route Valcarlos, affording a bird’s eye view of the multicolored heather- and fern-covered mountains facing France, as well as the rolling forest terrain facing Spain and leveling out toward Roncesvalles. Of this site, Aimery Picaud, the purported author of the Codex Calixtinus (the 12th-century pilgrim guide), wrote that it “is so high it appears to touch the sky; those who make the ascent believe they can touch the heavens” (courtesy of T.A. Layton’s translation that appears in his book, The Way of Saint James, 1976).

This is also where some believe Charlemagne’s officer Roland fell during his defeat in 778, when the local Basques defended their territory against Charlemagne’s expansionist designs on the region.

This historic marker, an upright rough-cut gray standing stone, is engraved simply with the name Roland, the date of his death (778), and the date the stone was erected, 1967. It makes a good fixed point in the foreground for the magnificent backdrop of mountains facing back toward France.

Down the hill from the monument is the Ermita de San Salvador (948-790-301; www.roncesvalles.es; usually closed), a small A-frame chapel of red schist and black slate, built in 1964. It marks the site of the earlier chapel of Charlemagne, where it is believed he fell to his knees and prayed to Santiago. (For Charlemagne did return, many times, according to legends. In fact, after his death Charlemagne was made one of the Camino’s leading champions; like Saint James, he leapt from far places to arrive in the nick of time for the church.)

More interesting than the 1964 chapel are some of the stones from the original walls of the medieval monastery that rest just in front of the modern chapel, tracing an outline of the wall foundations. Next to these scant remains is a pretty, modern standing stone engraved with the image of Our Lady of Roncesvalles, where you are invited to stand and utter a silent prayer. The outlines of the older ruin may date to the 11th century. This was the original chapel that sounded a bell at night and in fog to guide pilgrims to Roncesvalles. That bell is now said to be the one set in the Capilla de Santiago in Roncesvalles.

From here, Roncesvalles is a gentle, 1.5-kilometer (1 mile) downhill walk through more lovely beech and oak forest. You will soon see the blessed view of Roncesvalles’s monastery slipping above the trees and enter the hamlet through a passage along the back wall, near the albergue, monastery hotel, and collegiate church. Sometimes horses graze the forest here. Don’t be surprised if they meet you on the path.

The present monastery complex that defines the village of Roncesvalles (known as Orreaga in Basque) dates to the 12th century, but people have been traversing this territory for millennia. Given its importance as a pilgrim stop, it may come as a shock to discover the year-round population is only 21 people. The cream-white stone and black-slate-roofed hamlet is huddled around itself, with the monastery and abbey church at the center. Forest, more hills, and fertile fields surround the whole.

Roncesvalles is essentially a hamlet founded for, and defined by, its large 12th-century monastery complex of interlocking white and gray buildings. Collectively it is called La Colegiata de Roncesvalles, and to confuse matters, its most illustrious part, the monastery church of Santa Maria, is often simply called La Colegiata as well. The full extent of the Colegiata monastery complex includes (in the order you will encounter them as you step into Roncesvalles on the Camino): the pilgrims’ Albergue Real Colegiata de Roncesvalles, where most peregrinos stay in Roncesvalles; Hotel Roncesvalles (on your right after a short arched passageway), a modern hotel located inside a historic pilgrims’ hospital called Casa de los Beneficiados; the Iglesia de la Colegiata de Santa Maria (on your left); and finally, the rest of the monastery complex, immediately in front of you from the church. The cloister shares a wall with the church and is located just past the church on the left (closed from view and behind the wall). Straight ahead, the long Casa Prioral (Priory House) houses the monastery’s museum. Museum admission will give you access to the cloister, the exhibits, and the priory house, as well as a guided tour to the two other historic buildings of Roncesvalles, the Capilla de Santiago and the Capilla del Espíritu Santo, which otherwise remain closed.

The abbey or collegiate church, Iglesia de la Colegiata de Santa Maria (948-790-480; www.roncesvalles.es; daily, 8am-9pm) was consecrated in 1219 and is the monastery complex’s greatest highlight, an early Gothic building with beautiful stained-glass windows depicting both sacred and profane (but royal) personages.

Iglesia de la Colegiata de Santa Maria

detail on the Iglesia de la Colegiata de Santa María

the pilgrims’ albergue in Roncesvalles

At the center is a silver-wrought canopy sheltering the altar and the church’s most sacred possession: the 13th-century Gothic statue of Nuestra Señora de Roncesvalles, Our Lady of Roncesvalles. It is possible that a devout pilgrim brought the statue from Toulouse, where it was most likely made. I find the best-spent time in Roncesvalles to be in the church itself, enjoying the stained glass and the sweeping stone walls that form a structure that is more square than rectangular, embracing you on all sides. This is Spain’s earliest Gothic church and a great place to contemplate the Queen of the Pyrenees, as Our Lady of Roncesvalles is called all across the mountain range.

You can enjoy celebrations of Mary during mass, a formal and celebratory observation for pilgrims and locals, which is followed by a pilgrims’ blessing every evening at 8pm. This is one of the more formal and potent masses on the Camino, even for secular pilgrims, because it is a colorful ritual enacted at the beginning of a charged journey on the Camino. The power here also comes from the great sense of accomplishment at meeting the challenge of climbing over the Pyrenees.

The highlight of the Museo (948-790-480; www.roncesvalles.es; daily 10am-2pm and 3:30-7pm; €5, €4 for pilgrims) is the guided tour (English possible), included in the price of admission, which takes you through the small square monastery cloister and the other historic buildings of Roncesvalles, Capilla de Santiago and the Capilla del Espíritu Santo, that are otherwise closed to the public.

The museum itself is also interesting for two pieces of religious history associated with the village’s Camino history. First, there is an oliphant, an ancient horn made from an elephant tusk that can make quite a blasting sound; it may be the one that Roland blew on Puerto de Ibañeta when he was seeking Charlemagne’s aid. (The other possible candidate is held in a basilica in Bordeaux.) Then there is the so-called Charlemagne’s chessboard, a pretty inlaid black-and-white chessboard pattern found not on a board, but on a reliquary box from the 14th century. Though it’s neither a chessboard nor personally associated with Charlemagne, who lived in the 8th and early 9th centuries, it is a fine example of fine medieval craftsmanship. The museum occupies the space of the long, two-storied Casa Prioral (Priory House), which connects perpendicularly to the collegiate church and cloister.

Once you pass the large monastery complex, to your left you will see the Capilla de Santiago and the Capilla del Espíritu Santo standing side to side. The diminutive Capilla de Santiago (access by guided tour is included with admission to the Museo de la Colegiata) is a 13th-century Gothic building, and since that century its bell has been rung at night to help delayed or lost pilgrims make their way to Roncesvalles in the dark. In Christianity, the bell symbolizes the voice of God calling the faithful to him. It is possible this is the same bell that once belonged to the 11th-century chapel of San Salvador at Puerto de Ibañeta. Inside, it is a simple stone single-aisle nave chapel with a solitary sculpture of Saint James on the altar.

the Capilla de Santiago and Capilla del Espíritu Santo in Roncesvalles

Right next to the Iglesia de Santiago you’ll find the broad, square, 12th-century Capilla del Espíritu Santo. The chapel is built over a crypt holding the bones of pilgrims who died during the Valcarlos crossing; it is a somber reminder of the fleeting nature of life. The chapel was built first in memory of Charlemagne and Roland; some believe that the bones of Roland and some of his men were buried here, too. The structure is rarely open, except for on a tour arranged via the museum, but it’s always visible through the iron gate and open arcaded windows.

Along with Lourdes, Roncesvalles is one of the most important Marian sanctuaries in the Pyrenees. Region-wide festivities in Mary’s honor take place in September, to celebrate her birth on September 8.

Every Sunday in May and early June, there are small pilgrimages made to Roncesvalles from the surrounding villages—beautiful, cheerful, and reverent processions that are all dedicated to the Mary of Roncesvalles. To see which village makes its pilgrimage on which Sunday, visit www.roncesvalles.es. I especially enjoyed being part of one from Burguete, right on the Camino, making a reverse walk back to Roncesvalles.

Roncesvalles is a tiny hamlet, despite the large and famous monastery, and you will find everything easily by standing in the middle of the settlement and simply looking around. All the accommodations are next to each other.

The largest and most traditional, in operation since 1127, is now housed in the modern and fully renovated sections of Roncesvalles’s monastery, the Albergue Real Colegiata (open all year; 948-760-000; www.alberguederoncesvalles.com; 218 beds; €12). The albergue is managed by Dutch hospitaleros and is clean, with very comfortable facilities, hot showers, and semi-private cubicle accommodations (four beds per compartment). The communal meal is fortifying, basic but good.

Next door, also on church grounds, the priests’ quarters known as the Casa de Beneficiados, built in 1724, have been renovated and converted into the Hotel Roncesvalles (Calle Nuestra Señora de Roncesvalles, 14; 948-760-105; www.hotelroncesvalles.com; €55-135), with 25 luxury apartments or rooms. You can step in to see the space, though it looks more like a modern luxury hotel on the inside; the outside remains unchanged and shows continuity with the pilgrims’ albergue that you just passed. The accommodations here are impeccable, but the atmosphere and reception is somewhat neutral and far less interested in you as a pilgrim than other local accommodations. There is a decent hotel restaurant, but try to get a table at Casa Sabina for a more engaging and memorable meal.

Casa Sabina (N135, s/n, Roncesvalles; 948-760-012; www.casasabina.roncesvalles.es; rooms are €45-55; breakfast €3.50, lunch and dinner €13-20) is both a cute country-style inn with rooms on the upper floors and a popular S café-restaurant on the entry level. Given that this is a small place, and massive amounts of people pour over the mountains on any given day, sometimes the place is too packed and busy and can’t cater to everyone. Try to get in, though, for the creative appetizers on their picoteo (pintxo) menu, but also for the entrees, including homemade ravioli and empanadas (savory pies).

The entryway of La Posada (N135, s/n, Roncesvalles; 948-790-322; www.laposada.roncesvalles.es; open Mar.-Dec.; 19 rooms; €55-75) will look familiar if you love the movie The Way: This is where the character Tom (Martin Sheen) stayed his first night on the Camino. In the movie, La Posada is cast as a basic albergue, but in reality, it is a comfy country inn with a bar on the entry floor and, for €10, a quality plato del peregrino (pilgrim’s plate) for guests. (Everyone, however, can enjoy the bar.) Also contrary to the movie, the owner is energetic and excited about welcoming peregrinos, not tired and washed out. He’ll even help you find alternative accommodations if the town is fully booked.

Roncesvalles has shuttle, bus, and taxi services that connect it to larger urban hubs, including Pamplona (the closest), Biarritz, and Bilbao.

The best way to reach Roncesvalles is from Pamplona, which is connected to the international hubs of Barcelona and Madrid by train. From Pamplona, you can take a bus with ALSA (www.alsa.com) or a more costly but efficient pre-arranged shuttle with Express Bourricot (www.expressbourricot.com) to Roncesvalles. You can also fly into Bilbao and arrange this same shuttle to take you to Roncesvalles.

From Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (27.5 km/17 mi; 40 min.): Take the D933 in France south to Arnéguy, where it crosses the border (no border controls) and remains the same road but is called the N-135 in Spain.

From Santander via Bilbao (300 km/186 mi; 4 hours): Take the A-8 east and exit onto the AP-68 south at Bilbao. Continue on the AP-68/N-622 to Vitoria-Gasteiz and exit onto the A-1 and A-10. Take exit 97 onto the AP-15 to Pamplona. Take the PA-30 to N-135 (Carretera de Francia) that goes to Roncesvalles.

From Pamplona (47 km/29 mi; 1 hour): Take the N-135 north from Pamplona to Roncesvalles.

From Madrid (440 km/273 mi; 5.5 hours): Leave the city on the A-2/E-90 northeast toward Medinaceli; take the N-111 after Soria; next get on the N-232/A-12/LO-20 at Logroño. Continue on the A-12 south of Pamplona and take the exit to the A-21, then exit onto the N-234. Take NA-1720 at Urrozo and take it to the N-135 and Roncesvalles.

From Barcelona (535 km/332 mi; 6 hours): Exit west on E-90 to AP7, then AP-2 to Zaragoza; exit to AP-68/E-805 to AP-15 past Tudela and to Pamplona; take the AP-15 to PA-30 and exit north onto N-135 to Roncesvalles.

Express Bourricot (www.expressbourricot.com) runs shuttles from the airports and train stations in Pamplona (1 hour) and Bilbao (2.5 hours) to Roncesvalles (€84-220).

RENFE (www.renfe.com) connects Madrid (seven trains daily; 3-4 hours; €42-78) and Barcelona (seven trains daily; 4-5 hours; €33-61) to Pamplona, where buses, taxis, and shuttle connect to Roncesvalles.

Autocares Artieda (www.autocaresartieda.com; 1.5 hours; €7) runs one bus between Pamplona and Roncesvalles, Monday through Saturday; no buses on Sunday.

Nothing could be easier: Look for the road sign that says “Santiago de Compostela 790 km” (491 mi—that’s the distance a car drives, but the numbers are a bit different for thru-hikers). The Camino runs to the right of the sign and road.

The forest between Roncesvalles and Burguete grows dense and intimate, thick with beech and oak growing in animated shapes and postures. It feels physically enchanted. Though the road is not far to the left, here it can get very quiet and still, as if nature spirits are watching. It was believed that in this forest, up until their persecution in the 16th century, witches—white witches, curanderas—would meet to hold their healing rituals, in private and in the power of a remarkable natural setting. This “coven” was tried under some of the famous witch trials in Spain, where nine from this area were burned at the stake by the Inquisition’s authorities, five of them in Burguete.

In 2 kilometers (1.2 miles)—1 kilometer (0.6 miles) before Burguete, on the left of the forest path—stands La Cruz Blanca (“the white cross”), also called Roland’s Cross, erected here in the 17th century to protect the path between Roncesvalles and Burguete. As the commemorative plaque states, the cross is a “symbol of divine protection,” and it could have been intended for the healers as much as for anyone else. These matters, now in hindsight, are being recast with a more balanced view, as the information board associated with the cross here attests. A similar information board, also on the local witchcraft tradition, can be found in front of the village church in Burguete.

Best known as Hemingway’s village in the Pyrenees, Burguete (pop. 244) is where the writer would come and stay, in the Hostal Burguete, to go trout fishing with friends nearby. More than Roncesvalles, Burguete gives the feel of a Navarran-Basque village removed from the demands of city life and tourist pressure, and of the two villages I prefer to spend the night here. Whitewashed stone homes with thick, shuttered windows and heavy stone doorways engraved with coats of arms line the village’s single street. Here, too, you’ll find several good places to eat and stay.

The interior of this church (Plaza del Ayuntamiento; 948-760-032; www.burguete.es) is a highlight of Burguete, but unfortunately it is open only at select hours for Sunday mass and on festival days. Inside, the story of the stag and the Lady of Roncesvalles takes on Mistress of Animals and Mother Forest proportions: Observe the large, beautiful stained-glass window of Our Lady of Roncesvalles seated in a forest, very likely the one you just walked through, appearing like a gracious healer surrounded by leaves, trees, and flowers.

In front of the church is a small billboard with information about the history of witchcraft in the village and surrounding region; it identifies this as the site where five “witches” (traditional healers) were persecuted and some burned at the stake in the 16th century.

Sturdy stone walls and green shutters identify the S Hostal Burguete (Calle San Nicolás, 71; 948-760-005; www.hotelburguete.com; 20 private rooms; €30-59) on the right entering town. Inside, wooden floors, white walls, and heavy hand-carved furniture greet the visitor, much as they did Ernest Hemingway when he came here to go trout fishing in the Pyrenees. With its private rooms and large window views of the Pyrenees, this is an ideal respite from the crowds lining up for bunk beds 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) farther back in Roncesvalles. The attached village bar and restaurant makes mojitos and also serves excellent local wines and good, rustic, home-cooked meals. Room 23 is the fabled room where Hemingway stayed and wrote.

la Cruz Blanca in the forest between Roncesvalles and Burguete

Bar Frontón in Burguete

the Hostal de Burguete where Hemingway stayed to go trout fishing

Casa Bergara (Calle San Nicolás, 44; 948-760-044; four rooms; €30-40) is a family home—a mansion, really—with simple but comfortable guest rooms on the upper floor, all with private bath and old-fashioned beds with carved wood frames. Some bedside stands hold Eastern Orthodox painted icons of Mary and Jesus, just for a little bit of extra grace. The matron of the house is low key, but kind and concerned for her guests’ comfort.

A great café for drinks, snacks, and casual meals is the S Bar Frontón (Calle San Nicolás, 58; 948-790-406; €3-11) on the village’s main square, on your left just before passing the church. Often a large friendly husky lies at your feet, happy to ignore you. Check out the coat of arms over the door as you leave. See the stag? It’s a reference to the legend about the discovery of Our Lady of Roncesvalles by two shepherds who followed a deer, possibly a stag. Try the empanandas (savory pies), especially the one filled with garlicky spinach and eggs (€3-6).

At Hotel Loizu (Calle San Nicolás, 13; 948-760-008; www.loizu.com; rooms at €55-80), you’ll find a consistently good menú del peregrino (€10, including locally caught trout, steak, various pasta dishes, and salads) plus more choices on the à la carte menu (€15-20), as well as standard hotel rooms (used by a lot of tour groups) that are neat, fresh, and restful. Best of all, the staff are always positive, energetic, and welcoming.

The Camino continues to follow the road through the center of town, and then, about mid-way, makes a sharp right off the road, right before passing the bank building of Banco Santander, and through a farmstead, where you may share the path with caramel-colored cows. This marks the point where you are no longer walking south but have now turned more toward the west; you will remain westward bound for the rest of the Camino, however far it takes you.

Approximately 1.5 kilometers (1 mile) after leaving Burguete, you enter rolling hills and dale, forests of oak and beech, an area rich with bird life—from hawks, falcons, and eagles to titmice, robins, and gold finches. This beautiful 3-kilometer (1.9-mile) stretch flourishes with columbines in spring and October crocuses in autumn. The forest and hills open up on the final approach to Espinal village, with its sturdy stone farmhouses elegantly tucked at the foot of the slope.

Known as Aurizberri in Basque, Espinal (pop. 239) is a quintessential Basque-Navarran village of stucco stone and timber homes painted white with red stone doorways and thick wood windows and shutters. Look for the ever-present herb- and thistle-flower bundles on many of the doors in the village. Espinal was founded in 1269 to support and protect pilgrims on their passage through Navarra. Today it remains a pilgrim-friendly place with food and lodging options.

Albergue Irugoienea (Calle Oihanilun, 2; 649-412-487; www.irugoienea.com; open from Easter to Oct.) has 21 beds in two dorm rooms (€12) and three private rooms (€37-52), all spotless and homey, plus a communal dinner and breakfast (€11, €4) with a great little covered porch and garden. You’ll find it in the last building on the left down the main road.

In the same direction, before Albergue Irugoienea, you’ll pass the S Hostal-Albergue Haizea (www.hostalhaizea.com; 948-760-379), featuring a great café for stopping for refreshments (breakfast is popular, €4-5), full meals (€12), or a night’s sleep (28 beds in three dorms, €12; 12 private rooms, €45-60). With a rustic wood dining area with a warming fireplace, as well as a sunny terrace overlooking the green hills of Navarra just 100 meters (328 feet) off the edge of the trail, Haizea hits the spot for a mid-morning breakfast or snack to fuel up for the trek to Zubiri. Dorm-room beds are more single-standing than bunks (there are a few of these), and are set in pleasingly angled roof rooms with high wood beams. They are open all year, except the last two weeks of November.

From Espinal to Biskarreta is an idyllic saunter through rolling hills, forests, and grazing pastures. Views of the mountain landscape beyond reveal glimpses of several river valleys and forests you will eventually cross.

leaving Espinal

Biskarreta (pop. 97) is also spelled Viscarreta and is also known by its Basque name, Guerendiain. The village produces patxaran, a red-colored brandy-like elixir made from sloe, a locally grown fruit which is similar to small plums. It is a popular digestive drink, typically consumed after a meal, made and drunk in Navarra and Basque Country. You can sample it at Bar Dena Ona, but be warned: Its alcohol content is high!

The best place for food is S Bar Dena Ona (Calle San Pedro, 2; 669-755-564; €5-10), to the left of the trail before you enter the village proper. (Look for the funky clay-and-metal animal sculptures arrayed across the yard.) While tortilla Española is ubiquitous bar food, found everywhere in Spain, I think Dena Ona’s may be one of the best examples of this thick, caramelized-onion-and-potato Spanish omelet. Order a bowl of big, plump green olives to go with it, and if you think you can handle it, a foaming cold beer. Heaven. This is also the place to try the locally produced brandy-like elixir called patxaran.

Casa Rural Amtxi Elsa (Calle San Pedro, 14; 626-560-675; www.amatxielsa.com; five rooms at €35-60) is to the right of the Camino as you are about to enter into the village. The very kind and warm hosts, Elsa Fábrega and her husband, Jorge, welcome you into a traditional stone and timber Navarran country family home turned into a rural inn. A common room has a corner fireplace and stuffed leather chairs, while an outdoor terrace overlooking the garden is a nice place for breakfast or to enjoy a pre-dinner drink.

The Camino passes though Biskarreta and is well marked. Notice the door lintels of the houses you pass; many are engraved with dates and original designs that relate to each household’s history. You will walk past backyard gardens, farmsteads, and oak forest.

Bar Dena Ona in Biskarreta

Around 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) before Zubiri, the path begins to get progressively rockier and more uneven, and the oak forest denser. You’ll pass over the lookout point Alto de Erro (Km 736) 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) before Zubiri. At 810 meters (2,657 feet), this offers one last panoramic view of the mountains before making a gradual descent toward the valley that holds Pamplona.

trail marker near Alto de Erro

If you plan to sleep in Zubiri, cross the bridge into town. Otherwise, do not cross the bridge, but instead go left from where the trail enters the edge of Zubiri and follow the way-markers along the left side of the village; the village and the river Arga will be to your right as you continue.