Detour: The Via Romana

Detour: The Via RomanaS San Antón Monastery Ruins Km 452.5

S Ermita de San Nicolás at Puente de Itero Km 441.3

Villarmentero de Campos Km 417.5

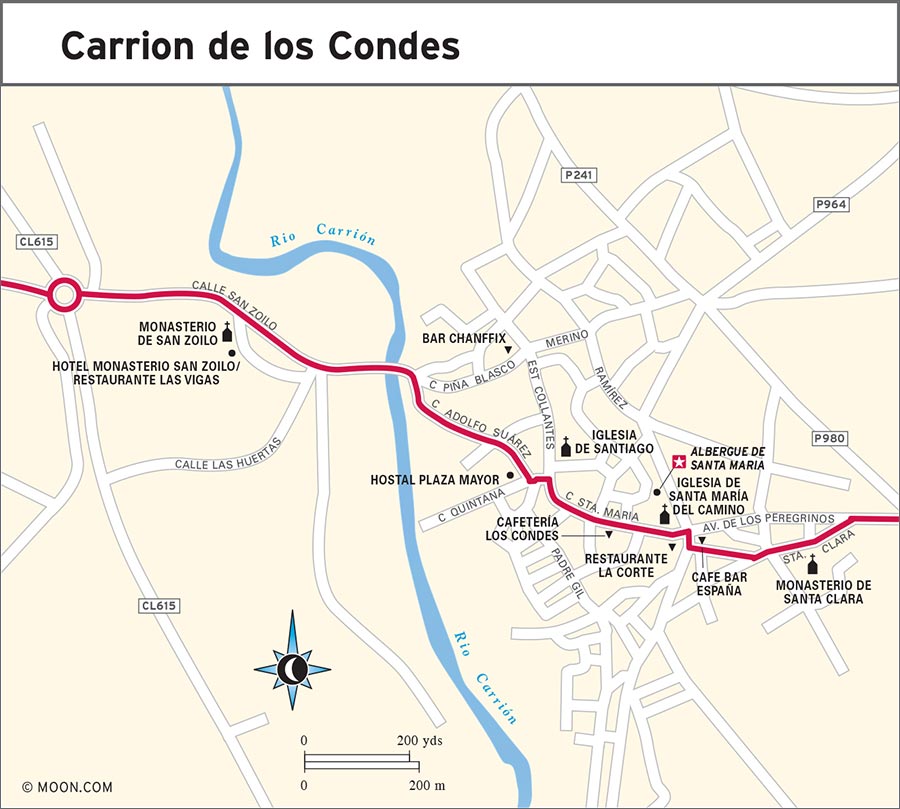

Carrión de los Condes Km 404.2

Terradillos de los Templarios Km 377.8

San Nicolás del Camino Real Km 372

Ermita de la Virgen del Puente Km 366.9

Bercianos del Real Camino Km 353.9

Mansilla de las Mulas Km 327.4

Archaeological Site of Lancía Km 324.4

This is the classic meseta, the high plateau of Castile and León, framed perfectly between the two regal cities of Burgos and León. In stark contrast to the ascent and descent and forest cover of the first sections of the Camino, here it is all open sky and endless horizon—but with its share of wave-like rolling terrain, in some places 950 meters (3,117 feet) in altitude. The region has a beauty all its own. The wildlife here is stunning and, like pilgrims, is more active at dawn and dusk to cope with the intense sun, wind, heat, and cold. Look for clusters of white butterflies clinging, fast asleep, to vertical stalks of purple thistle, or frogs burbling in canals and creeks. If you get an early start, be sure to turn around and watch the sun rise from the eastern horizon in a rainbow swirl of orange, fuchsia, violet, and lavender.

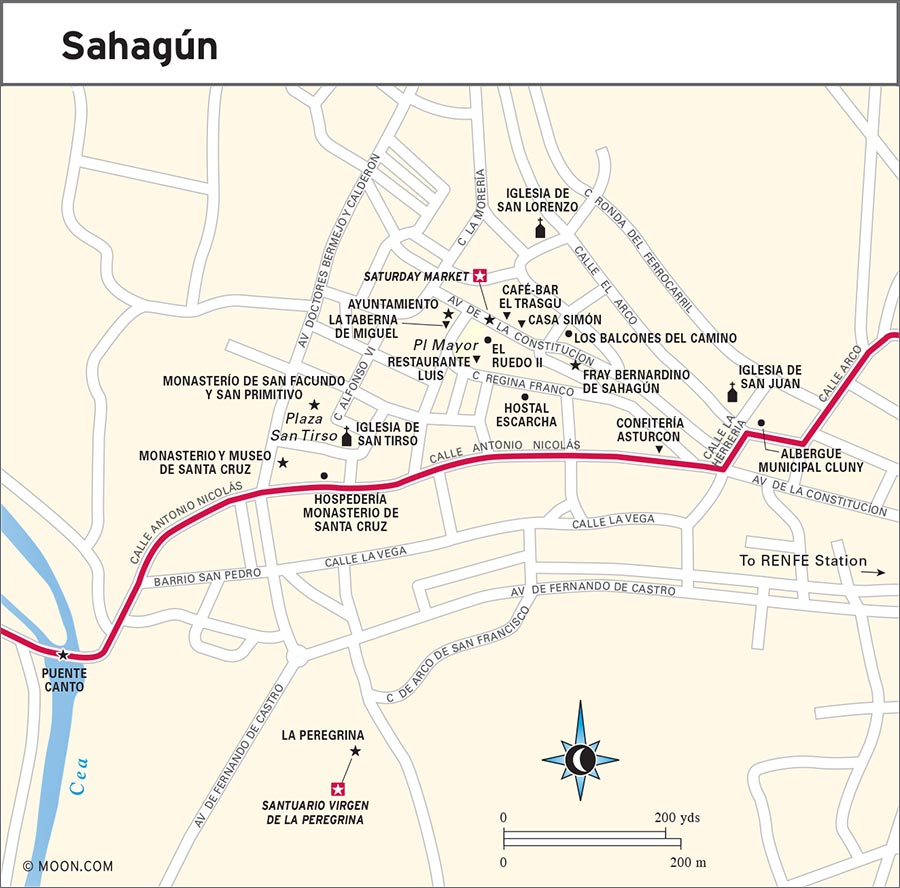

The landscape of Castile and Léon brings to life the medieval knights and royal battles for power over Iberia, not only between the Christian north and the Muslim south, but also between the rival Christian kingdoms of Castile, León, Navarra, and Aragon. This is the territory of El Cid, a Castilian mercenary with an Arab nickname (al-sidi, meaning “lord” or “sir”) who fought on many sides, north and south. And here is another irony: As much as the region’s history depicts battles between Muslims and Christians, it also offers proof that those centuries were ones of creative flourishing, cohabitation, and diversity—convivencia. In Castile, more than anywhere else on the Camino, you will see the influence of Spain’s two other major faith communities, Muslims and Jews; It’s evident in the aesthetics of the churches and monasteries, especially in Burgos and Sahagún.

You are also now in core bodega country. (Bodegas are family wine cellars with underground passages dug into natural or manmade hills.) This is where each family makes and stores their annual wine, and also where they store other harvested and produced foods, from cheeses, sausages, and cured hams to grains, roots, and legumes. The entrance, the room nearest the surface, is often where friends visit the family and enjoy a drink, tapas, and meal. Each bodega has Hobbit-hole-like doors and icons around the entrance that seem both to decorate and protect the contents. Walking the Camino, you’ll pass many bodegas as you approach the villages and towns.

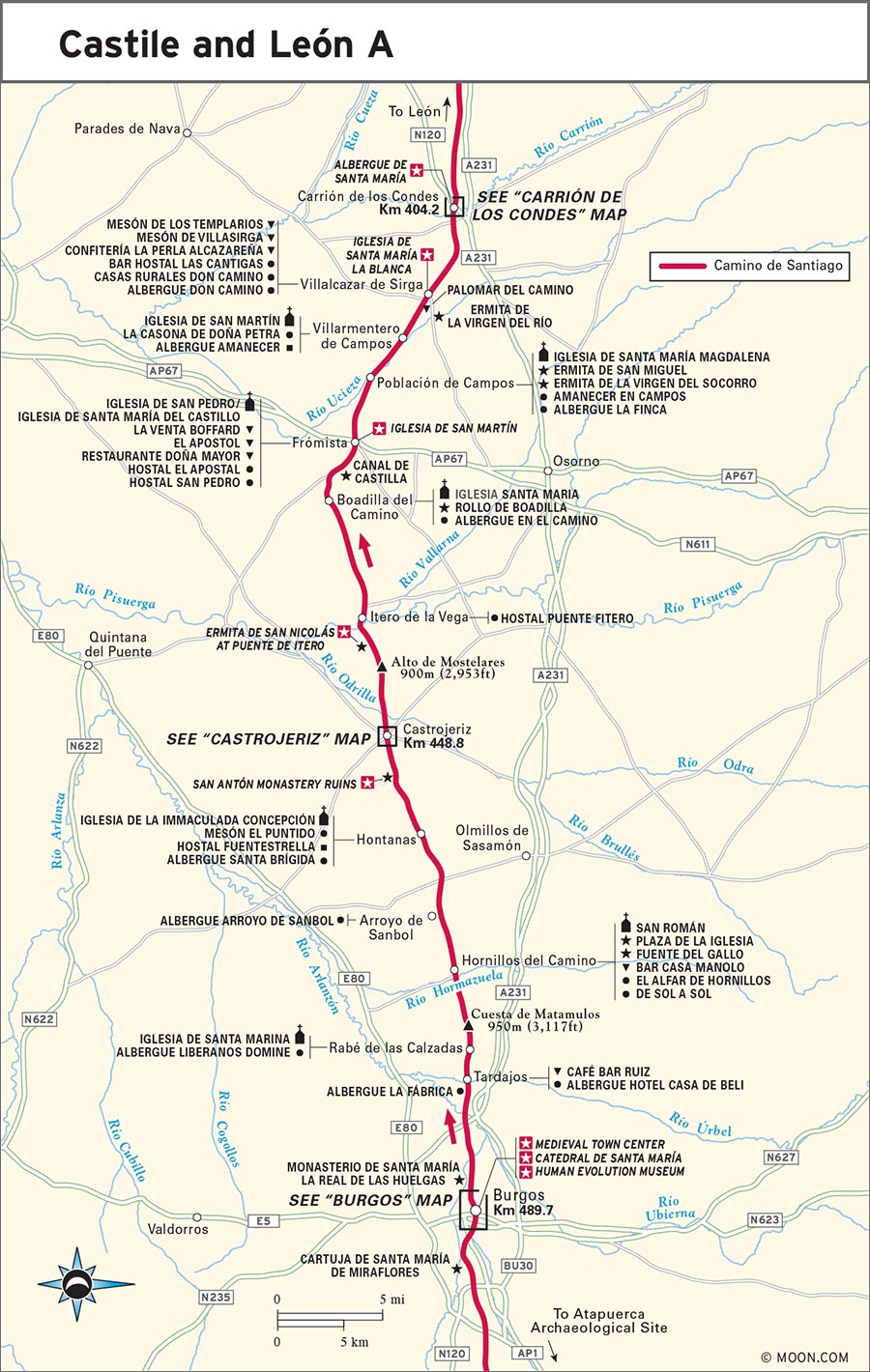

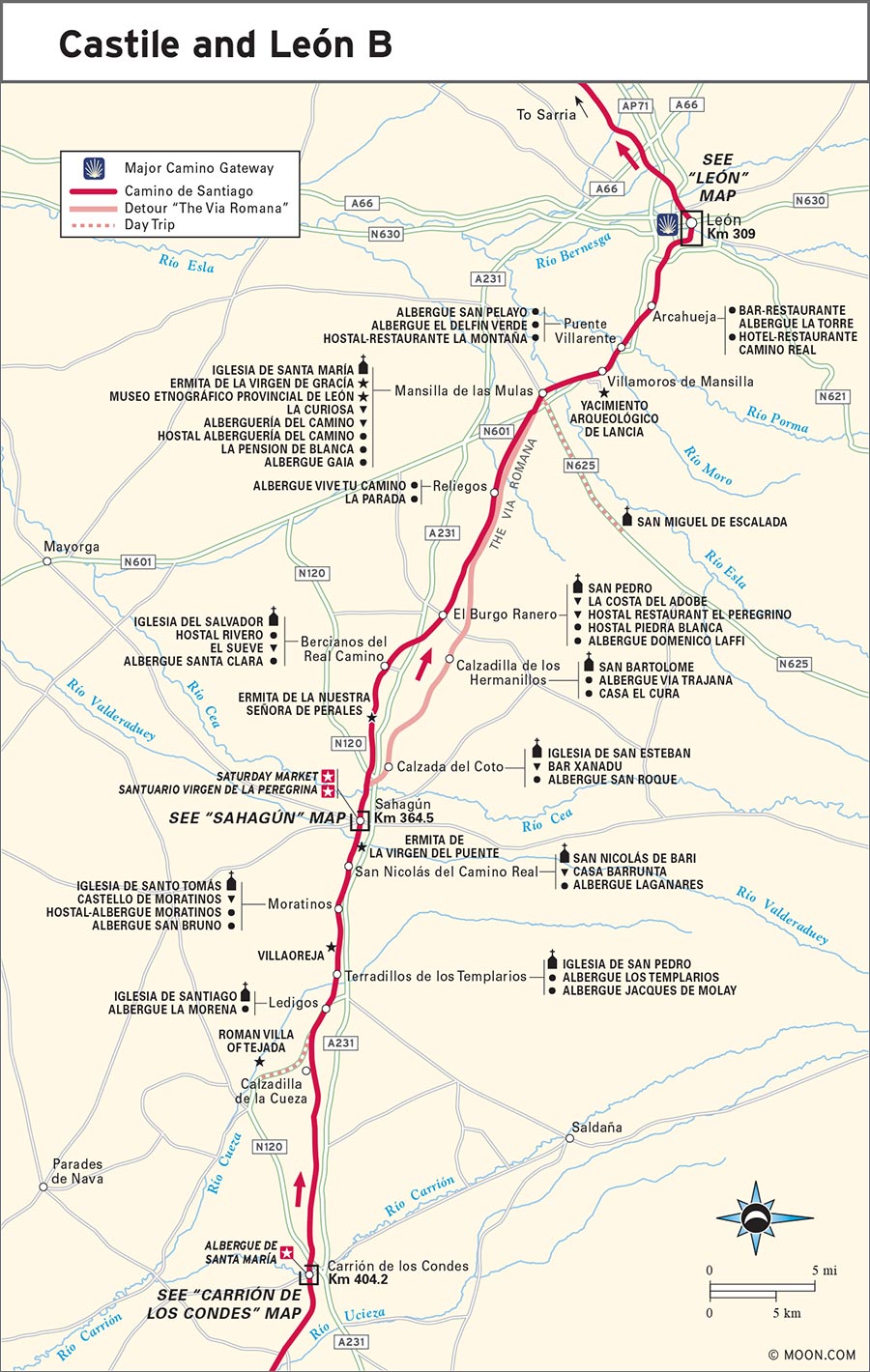

Walking the full 181-kilometer (112-mile) stretch of the Camino from Burgos to León will take 7-9 days if you average 20-25 kilometers (12.5-15.5 miles) per day. This pace allows time to explore a little each day.

Consider 1-2 days to explore Burgos, and a day to visit Atapuerca, Europe’s oldest site for human fossils. Add another day to make a detour from Mansilla de las Mulas to visit the rare 10th-century pre-Romanesque and Visigothic chapel of San Miguel de Escalada.

Two detours reduce the long tracts where the Camino runs parallel to the road after Frómista (Km 424). The first is an easy side-step, a few meters farther to the right of the road and the historic Camino, to follow the bank of the Ucieza river from Población de Campos (Km 420.6) to Villalcazar de Sirga (Km 409.8).

The second detour, 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) after Sahagún (Km 364.5), takes the path where once the Roman road, the Via Calzada (also called Via Romana and Via Trajana/Traiana), passed. This detour adds little by way of extra distance (less than 1 km/0.6 mi) but takes you away from the road along a 31-kilometer (19.2-mile) stretch, 17.7 kilometers (11 miles) of which lacks support structures. The two paths join as one again at both Reliegos (Km 333.7) and Mansilla de las Mulas (Km 327.4).

If you find yourself short on time, or if you want to bypass the unappealing industrial outskirts of León, you can get a bus from El Burgo Ranero, Mansilla de las Mulas, or Puente Villarente to León. You’ll gain about one or two days of walking, but unless you wait until Puente Villarente to get on the bus, you’ll miss the Roman archaeological site of Lancía, which is just after Mansilla de las Mulas. Another popular option to speed your journey is to bike from Burgos to León.

The route from Burgos to León traverses the bulk of north-central Spain’s meseta, a high plateau. This is big plains and big sky country, though there are still hills, especially on the stretch from Burgos (Km 489.7) to Boadilla del Camino (Km 429.7). After Boadilla del Camino, the terrain levels significantly and invites a new challenge—seemingly endless and unvaried terrain that can take pilgrims more deeply into their own thoughts.

The trail is well marked. Yellow arrows painted or engraved on stone and wood surfaces continue to guide the way, as do the knee-high stone pillars with engraved and stylized scallop shells. There is not a lot of walking parallel to a road in the first portion of this section, but from Frómista to León, about 50 percent of the historic Camino passes parallel to the road. Two detours significantly reduce this.

There are three other stretches where there are few or no support structures for more than 8 kilometers (5 miles): the 16.9-kilometer (10.5-mile) section from Carrión de los Condes (Km 404.2) to Calzadilla de la Cueza (Km 387.3); the 10.6-kilometer (6.6-mile) stretch from Sahagún (Km 364.5) to Bercianos del Real Camino (Km 353.9); and the 12.9 kilometers (8 miles) between El Burgo Ranero (Km 346.6) to Reliegos (Km 333.7).

The meseta is open, exposed, and often high-altitude plains that average around 850 meters (2,789 feet). This makes for a place of sweltering heat with little shelter or shade in summer that is equally exposed to wind, rain, snow, and frigid temperatures in winter. In spring and autumn, the climate can fluctuate, but generally these are the most pleasant and moderate seasons. If walking in summer, it is imperative to have sun protection and to carry plenty of water. It is also best to start walking early in the day and finish walking by early afternoon. In winter, bring layers. Days are shorter, and many places may be closed after October, so you will want to walk at the first sunlight; be ready to stop before the sun goes down, and be prepared to stay in hotels if albergues are closed.

The most popular starting point is Burgos, the second-largest city on the Camino, after Pamplona. The city is most easily accessed by train or bus. Another popular and well-connected starting point is midway, in Sahagún, which is most easily reached by train. El Burgo Ranero is a rare village with a transit hub on the meseta, connecting to León via bus and train.

Camino bikers in front of the Catedral de Burgos

The east-west autoroute A-12/A-231 and N-120, named for the Camino, Autovía del Camino de Santiago, is never far from the walking trail between Burgos and León.

No convenient flights connect to Burgos’s municipal airport (RGS). The nearest airport is Bilbao (BIO; www.aena.es/es/aeropuerto-bilbao), coming from several destinations in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, and from Brussels in Belgium and Lisbon in Portugal. Frequent bus and train departures connect Bilbao to Burgos.

RENFE (www.renfe.es) has several stops along this stretch of the Camino. The train has many connections from all points in the country and also has a line running along the Camino, stopping in Sahagún and El Burgo Ranero between its stops in León and Burgos. Frómista is also accessible via train from Madrid.

Monbus (www.monbus.es) and ALSA (www.alsa.es)—often working in concert—serve destinations between Burgos and León (including Castrojeriz, Frómista, Carrión de los Condes, Terradillos de los Templarios, and Mansilla de las Mulas). The bus is often the most efficient way to get around, as many locals in rural areas rely on this service to get to urban centers for work and shopping.

There’s also a direct bus from Madrid to Burgos.

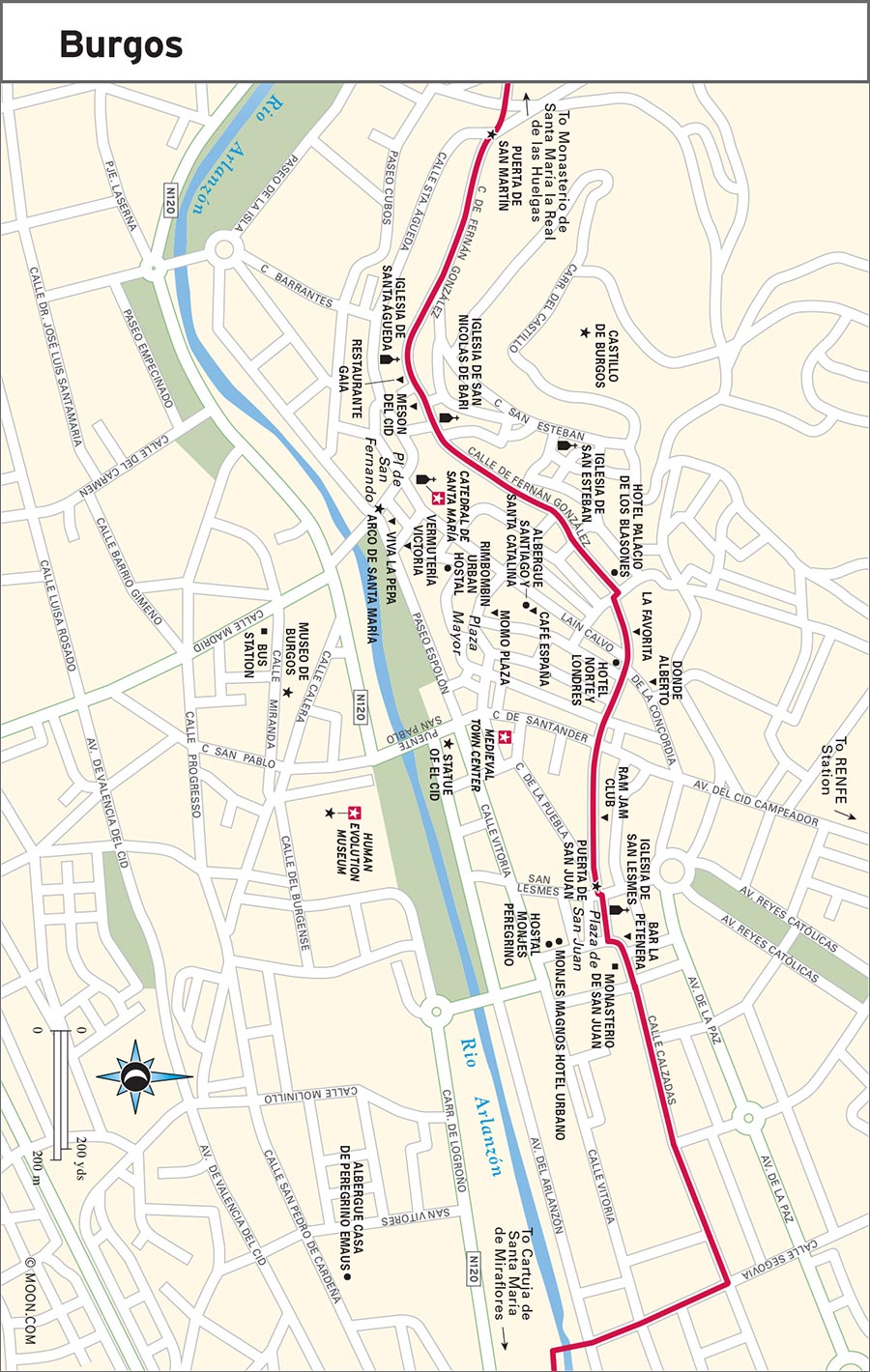

Burgos (pop. 178,966) is a beautiful and prosperous city on both sides of the Arlanzón river. The medieval walls of the enclosed town are a dramatic backdrop to the river and a splendid atmosphere for the nightlife that it draws, especially on weekends. Inside the walled city and around the walls are several interesting churches, the most dominant being Burgos’s imposing cathedral, Spain’s third largest after Seville and Toledo. The other churches—San Lesmes, San Nicolas, San Gil, San Esteban, and San Águeda—offer more intimacy by contrast and are worth visiting for a better sense of what medieval Burgos felt like.

Burgos is also home to one of the world’s most important human evolution museums, thanks in large part to the nearby archaeological site of Atapuerca. It is also a university town and has a vibrant student population, with tapas bars, restaurants, outdoor cafés, and tree-lined walks and parks. Much of the action takes place along the river that flows through the city. All this makes the city an ideal place to explore for an extra day or two before returning to the Camino. The Camino itself passes through the heart of the medieval walled town, entering at Puerta de San Juan and exiting at the Puerta de San Martín.

Most of these sights are within the walls of medieval Burgos, easily navigated if you use the cathedral in its heart as your beacon. The exceptions can be accessed by using the river as your guide, from east to west, in this order: Cartuja de Miraflores; a small jaunt over the river to the Iglesia de San Lesmes; back again to the south bank for the Museo de la Evolución Humana; and then to the Monasterio de las Huelgas on the western end.

The 15th-century Cartusian monastery Cartuja de Santa María de Miraflores (Carretera Fuentes Blancas; 947-252-586; www.cartuja.org; Mon.-Sat., 10:15am-3pm and 4-6pm; Sun., 11am-3pm and 4-6pm; donation) is set on the edge of a lovely pine forest on the east end of town. Still inhabited by monks of the order who live in seclusion and solitude, the monastery church is nevertheless open to the public. Inside, you can view the tombs of Queen Isabel la Católica’s parents, King Juan II and Isabel of Portugal, in the center, and that of her brother, Alfonso, set in the wall. Her parents’ tombs, completed in 1498, are perhaps the most dramatic and elaborate of any royal tombs, with a series of symbols and figures surrounding the lifelike carved-marble images of the reclining couple, who rest on a raised star-shaped platform. The monks living here are known for their craftsmanship of rosaries made from rose petals. On Sundays the public can attend mass at 10:15am.

Adelelmo (who would be named Burgos’s patron saint, San Lesmes) was a French Benedictine monk who arrived in Burgos in the 11th century to dedicate his life to serving pilgrims in the monastery of San Juan, which was founded here. He died in 1097, and the present church, the Gothic and 15th-century Iglesia de San Lesmes (Plaza de San Juan, s/n; 947-204-380; www.aytoburgos.es; free), holds his tomb in the center of its nave. It is open daily, with several religious services throughout the day. Visitors are asked to limit sightseeing visits to before or after services.

After visiting the church, step outside onto the Plaza de San Juan. If you stand with the church to your left, you will face the Benedictine Monasterio de San Juan (947-205-687; www.aytoburgos.es; Tues.-Sat., 11am-2pm and 5-9pm, Sun., 11am-2pm, closed Sun. afternoon, Mondays and holidays), where San Lesmes and his order housed and cared for pilgrims. It is now an interesting art exhibit space, with a lovely enclosed garden that’s open to the public during opening hours. In spring, if you look up at the old bell tower from the plaza, you will likely see nesting storks raising their young. Just to the right of the old monastery is Burgos’s public library, the Biblioteca Pública, an ultramodern building that retains the Gothic door from the old hospital of San Juan.

Burgos’s charismatic town center is surrounded by thick medieval walls that jut up along the north bank of the Río Arlanzón, containing the cathedral in its heart and the castle above it. With churches and plazas anchoring the interior, vibrant eateries, and locals coming here for a paseo, you’re sure to be pulled in.

If you are walking the Camino, you’ll find the medieval town center simply by following the yellow arrows and scallop shells inlaid into the pavement. Enter the medieval walled city through the gate on the eastern side of town, Puerta de San Juan, just off the Plaza de San Juan, outside the walls. Once inside the walls, allow yourself to meander. All roads within the walls ultimately will take you toward the cathedral, and to its south, the Plaza Mayor, an appealing and unpretentious square, each building painted a different color, with many cafés, restaurants, and bars offering diverse options for eating or for relaxing in the sun at an outdoor table.

the colorful Plaza Mayor in Burgos.

From the Puerta de San Juan, the Camino moves past the north side of the cathedral and the Iglesia de San Nicolas de Bari (947-260-539; Monday-Saturday, 11am-2pm and 5-7pm; Sundays, before and after mass; €1.50, free on Mondays), a well-endowed 15th-century church once favored by Burgos’s merchant guilds. Off this street and up the hill lie the castle ruins, some towers still standing.

In the 9th century, the king of León, Alfonso III, built a small castle over the remains of an early Roman fortress. Early medieval Burgos formed around this castle and the fortification and protection it offered several surrounding villages, which were known as burgos, burgs. It was modified and expanded over the Middle Ages to defend the region from incursions, and survived reasonably intact until it was blown up by Napoleon’s troops in 1813.

Today, it’s worth the climb up the hilltop to see the archaeological site of the Castillo de Burgos (Cerro de San Miguel; 947-203-857; www.aytoburgos.es/direcciones/castillo-de-burgos; €3.70; Jul.-Sept., Sat.-Sun. 11am-8:30pm, 11am-2:30pm). The city has restored aspects of the castle, and you can see the outline of the medieval foundations and some of the walls and towers. There are also good displays that recreate the medieval world from this hilltop, plus a great view down onto the cathedral just below and the city all around.

Just below the castle is the Iglesia de San Esteban. It is rarely open, so enjoy the exterior of this survivor from the 13th and 14th centuries, with its lyrical side porch with thick timbered roof and playful animal engravings around the doorway arch—including a smiling rabbit running towards two scallop shells. Could he be a pilgrim?

For lovers of religious art, Burgos’s Catedral de Santa María (Plaza de Santa María; 947-204-712; www.catedraldeburgos.es; Mar. 19-Oct. 31, 9:30am-7:30pm, Nov. 1-Mar. 18 10am-6pm, closed Dec. 25 and Jan. 1; €7, €4.50 for pilgrims) is as much a museum as a place of worship, not to mention of pomp and politics.

Begun by King Fernando III in AD 1221, it was completed a mere 22 years later, a feat that gives the church its unified aesthetic. That Gothic structure was then added to and elaborated on, becoming the multilayered walk through Castilian history that you see today.

You can spend several hours here, exploring the many chapels, elaborately carved choir, cloister, and layers of medieval to early modern art. But whatever your timeframe, be sure to see these four highlights:

• Transept: The place in the church’s cross-shaped ground plan where the arms intersect is beautiful and symbolic. Destroyed by a fire three centuries after it was built, the current vault was reconstructed in 1568 by Juan de Vallejo, who was inspired by the Mudéjar—Iberian Muslim—art of Spain. In the center of the transept’s dome is an elegant filigree eight-pointed star, which lets in soft natural light. You’ve seen this same pattern in the reconstruction of the church of El Puy in Estella (if you have been walking from there), and you’ll see it again in the Constable’s Chapel beyond the apse here, too. The crossing also stands directly over a rose-toned marble stone, marking the tombs of El Cid (1043-1099) and his wife Jimena Díaz (1046-1116) underfoot. Their bodies have been here only since 1921, when they were moved here from the monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña just southeast of Burgos.

• Rose window: The west entrance’s rose window with its six-pointed star—a common decorative motif in Christian, Islamic, and Jewish art—is ethereal and beautiful when viewed from the nave. It can represent many things, but top among them is the Seal of Solomon, symbol of a just and wise ruler. His seal also represents the force of heaven intersecting with that of earth, as with justice and wisdom, creating a perfect harmony. From the nave, you will also find the ornately carved wooden choir, built in the 16th century. At that time, it was the style in Spain to set these in the center of earlier churches, obstructing the full line of the nave. While that is unfortunate, take time to look closely at the interesting characters in the engravings. Some are humorous, expressive, and highly animated.

• Capilla de Condestable: The octagonal Constable’s Chapel is just behind the apse. This is an incredibly ornate Gothic to Renaissance space, largely from the 15th and 16th centuries. Look for the detailed tombs of Burgos’s first constable and his wife, Don Pedro Fernandez de Velasco and Doña Mencía de Mendoza, then take a look up at the chapel ceiling to see the Gothic-Mudéjar-fusion eight-pointed star. Similar to the Mudéjar-inspired star in the transept, this one precedes it and is by the late 15th-century architect Simón de Colonia.

• Cloister: Saunter through the late-13th- and early-14th-century Gothic cloister. Largely original, it offers a more serene and organic experience of the cathedral.

Iglesia de Santa Águeda (Calle Santa Águeda; 947-206-755; Mon.-Wed., 12-1pm and Thurs.-Sat., 5:30-7pm; free), west of the cathedral, is where in AD 1072 El Cid made his patron, King Alfonso VI of León (and imminently also King of Castile), swear that he played no role in the murder of his brother, King Sancho II of Castile. You’ll see this history forged in ironwork on the outside entrance door’s lock, an image of an altar with El Cid on one side holding his sword, and Alfonso VI on the other wearing the king’s crown. The current church, also known as Santa Gadea, is Gothic and from the 15th century, built over the 11th-century site.

The iconic passage of the Arco de Santa María was the main entry gate into medieval Burgos during the 14th century. Its present ornate and flamboyant appearance come from the 16th century, when the Hapsburg king of Spain, Carlos V, commissioned the building of a larger gate, its decoration directed toward the imperative that citizens be loyal to the crown.

If you return back to the Camino’s passage through the medieval town and follow it west, it eventually exits at the Puerta de San Martín, which marks the general vicinity where Burgos’s medieval Jewish and Muslim neighborhoods once stood. Though San Martín’s gate is a reconstruction, it retains the signature Mudéjar brickwork of Iberia’s Muslims (you’ll see more of this in Sahagún). Recent archaeological excavations around the gate of San Martín have revealed many layers of the city’s history, including tiles that date to the medieval Muslim neighborhood and structures related to the medieval Jewish one, one of Iberia’s most important Jewish communities. From here, the Camino meanders through city-park-lined neighborhoods and onward to the plains.

One of the world’s most important museums on human evolution, the Museo de Evolución Humana (Paseo Sierra de Atapuerca, s/n; 902-024-246; www.museoevolucionhumana.com; €6) showcases finds from the nearby Atapuerca archaeological site, a layer cake of human existence in Europe. The museum contains artifacts from over a million years ago, especially highlighting the earliest humans, Homo antecessor, who lived here 1.2 million to 800,000 years ago, and Europe’s earliest Neandertals, around 400,000 years old.

Museo de Evolución Humana in Burgos

the Arco de Santa Maria entrance gate into the walled center of medieval Burgos

bakery shop window in Burgos

This museum is also an important center for research about human evolution. Exhibit spaces are engaging, creative, and interactive: Experience a simulated brain as it fires off neurons for functions such as speaking, then learn about early human art and why we create these symbolic forms of communication. Descriptive panels are also in English.

The museums opening times are: Oct.-June, Tues.-Fri., 10am-2:30pm and 4:30-8pm; Sat., weekends and holidays, 10am-8pm; July-Sept., 10am-8pm. Admission is free on Wednesdays from 4:30-8pm and Tuesdays and Thursdays from 7-8pm; closed Mondays. General admission includes entrance to the nearby Museo de Burgos (Calle Miranda, 13; 947-265-875; www.museodeburgos; Oct.-June, Tues.-Sat., 10am-2pm and 4-7pm, July-Sept., Tues.-Sat. 10am-2pm and 5-8pm, Sundays, all year, 10am-2pm; €1), which also displays archaeological remains from the area, from the Paleolithic era through the Roman period and into the medieval era. It also houses a good collection of 19th- and 20th-century art.

Founded in AD 1175 on the land of one of Castilian king Alfonso VIII’s country palaces, the Monasterio de las Huelgas (Calle de Compases, s/n, 947-201-630; www.patrimonionacional.es/real-sito; open Tues.-Sat., 10am-2pm and 4-6:30pm, Sundays and holidays, 10:30am-3pm; €6) was Cistercian from the start and a convent for women from the nobility. Its abbess was powerful and oversaw several towns and other Cistercian monasteries. Las Huelgas was also the site of Castile’s royal pantheon, tombs that you can visit today, where kings were crowned and knights knighted. Not only was it the center of Castilian royal and religious power, it remains a treasure of Mudéjar architecture blended with the complex’s Romanesque and Gothic, reflecting convivencia—mixing and living together in harmony—over conflict.

The Mudéjar influence is clear in the tomb engravings, as well as in the roof and ceiling woodwork of the cloisters, the lacey plasterwork on the walls of the Capilla de la Asunción and the Capilla de Santiago, the multi-lobed archways of the former and the inlaid wooden ceiling of the latter, among many other spaces.

Today Las Huelgas remains an active Cistercian convent, with 32 nuns carrying on monastic life and service (www.monasteriodelashuelgas.org).

Every Wednesday and Saturday (9am-2pm) the weekly produce market sets up on the east end of town along the Calle El Plantío, running parallel along the north bank of the Río Arlanzón—midway between the Cartuja de Miraflores and the Human Evolution Museum, though these landmarks are on the south bank. Every Sunday (10am-2pm) is Burgos’s flea market, El Rastro, on the Plaza de España, to the northeast of the castle and cathedral, where you can browse antiques, books, stamps and old coins, among other things—something like an open-air ethnography museum of daily life from a bygone era. Open-air textile, clothing and shoe markets also set up Wednesdays (Parque de los Poetas; 9am-2pm), Fridays (Paseo de Empecinado; 9am-2pm), and Sundays (Calle El Plantío; 9am-2pm).

S Meson del Cid (Plaza Santa María, 8; 947-208-715; €35) has large windows overlooking the cathedral from the Plaza de Santa María and an interior of medieval-style stained-glass windows, ceramic tiles, and crisp white linens. This is the place to try Burgos’s famous morcilla (blood sausage), either on its own or in alubias rojas de Ibeas (a red bean stew with morcilla and chorizo, €9.90). Other signature dishes are the roast lamb (€23), the high-quality jamón Iberico de bellota (acorn-fed, free-range cured ham), and clams and artichokes simmered in white wine and herbs.

With its casual country décor, white wood walls, and contemporary cuisine emphasizing fresh, local, and healthy, Viva La Pepa (Paseo del Espolón, 4; 947-102-771; www.vivalapepaburgos.com) feels a bit like California. (Check out their smoothies or their tofu and spring greens salad.) They have an elaborate breakfast menu (€3-10) that is unusual in Spain, plus tapas (€7-10), lunch (€13.50), or dinner (€18-26). Though the address is on Paseo Espolón, the gardened promenade on the riverside, it has an entrance on the other side from the Plaza del Rey San Fernando, which faces the cathedral.

S Momo Plaza (Plaza Mayor, 16; 947-250-423; €5-12) offers excellent regional wines to go with their creative and tasty array of pinchos, such as beef-and-onion-stuffed mushrooms, red peppers filled with cod and hot sauce, and mussels stuffed with minced tomatoes, onions, and bread crumbs, then deep fried. They also make superb cocktails.

La Favorita (Calle Avellanos, 8; 947-205-949; www.lafavoritaburgos.com; €12-20) has beautiful stone and brick walls, elegant white tablecloths, and an immense bodega—wine cellar—with a wide selection of wines. They serve plates of regional cheeses and several kinds of Ibérico cured hams, grilled blood sausage (morcilla), salads, omelets, fois gras cooked in port, and a variety of grilled meats and vegetables.

Restaurante Gaia (Calle de Fernán González, 37; 947-279-728; €11) caters to vegetarians, offering something for nearly every taste thanks to a world-cuisine approach with inspired ideas, diverse ingredients, and bold spices and seasonings.

S Bar La Petenera (Plaza de San Juan; €5-10) is tucked in behind the Iglesia de San Lesmes (apse side) on the Plaza de San Juan. The setting alone makes the bar a place to visit, but the delicious pinchos, upbeat servers, and friendly customers will all keep you here. Bar La Petenera feels more like secret neighborhood spot than a tourist attraction. On warm days and evenings, the bar expands with outdoor seating into the plaza.

Donde Alberto (Plaza Alonso-Martínez, 5; 637-016-461; €4-10) is run by the ever-cheerful and upbeat Alberto, who also makes the fresh and innovative pinchos that line his counters from one end to the other. Everything is amazingly inexpensive. There is a wide selection of wines. It can get pretty crowded at night, but midday can make for a good lunch venue with fewer people.

This university town is alive with evening and weekend energy. The medieval town center is a major hub for multi-generational nightlife, and in many venues, even the Ram Jam Club, you’ll see people of all ages. Nearly everyone is out for the evening paseo to enjoy the squares and cafés, and to meet up with friends for a drink, an activity that flows seamlessly into a long night of hopping from one tapas bar to the next. If you meander through the Plaza Mayor and cathedral areas, as well as around the Puerta de San Juan and the riverside cafes around the Arco de Santa María, many of which also open on to the Plaza de San Fernando, you will come upon many enticing places to stop and enjoy the flow.

To join the vermouth resurgence in Spain, and especially Castile, head to Vermutería Victoria (Plaza Rey San Fernando, 947-204-281). Founded in 1931, the bar and dining room is an energetic mix of turn-of-the-century Belle Époque floral plaster carved walls and ceiling, classical paintings, and big-band music surging through the vermouth-laced air. As vermouth is considered a pre-dinner aperitif and you are in Spain, anytime before 10pm you’ll find the place festive and packed.

Ram Jam Club (Calle San Juan, 29; 629-709-447) is casual with a mellow, café-society feel, where a good selection of inexpensive drinks combines with rich conversation as well as occasional live music. It can get more pulsating during weekends, and is popular with students as well as music lovers of all generations. You can’t miss it for its clock sculpture at the entrance, the hour numbers all reading 6, and the wavy lines of the hour and minute hands implying that time can be left at the door. It is also a venue for the cider festival, Fiesta de Sidra, which takes place around the summer solstice in June.

Café España (Calle de Lain Calvo, 12; 947-205-337; www.cafeespana.es) is a classy place holding down the same spot since 1921. Known for its wide variety of coffee drinks, some straight-laced and others spiked, several evenings a week the café can turn out live blues, jazz, and flamenco. Sundays are Poesía y Música nights, where literature and music combine into a soiree of readings, performances, and discussions.

Albergue Casa de Peregrino Emaus (Calle San Pedro de Cardeña, 31a; 947-205-363; Easter-Nov. 1; 20 beds; €5) is a recently opened ecclesiastical albergue. Clean, well-run, and welcoming, it is popular among pilgrims and is an inexpensive place to stay in the city. It also has a good communal meal, based on donation, and a small chapel with evening service.

Albergue Santiago y Santa Catalina (Calle Lain Calvo, 10; 947-207-952; Mar.-Nov.; 16 beds; €6) is also known as the Albergue Divina Pastora because of its ideal location just above the chapel, Capilla de la Divina Pastora, a stone’s throw from the cathedral. They have eight bunk beds, for walking pilgrims only, in their simple but clean and uncrowded single-room dormitory.

Hotel Palacio de los Blasones (Calle Fernán González, 10; 947-271-000; www.hotelricepalaciodelosblasones.com; €90-100) is in an old palace in the heart of the pedestrian medieval town. With beautiful thick stone walls and simple decor, it’s a lyrical merging of past and present.

Hotel Mesón del Cid (Plaza de Santa María, 8; 947-208-715; www.mesondelcid.es; 49 rooms; €65-75), located in a stunning setting right in front of the cathedral, offers consistent high quality. Rooms are colorful, spacious, and simply but tastefully decorated, with spacious modern bathrooms.

S Monjes Magnos Hotel Urbano (Calle Cardenal Beniloch s/n; 947-205-134; www.monjesmagnoshotel.com; €50-70, call to inquire about special pilgrim prices not advertised online) offers several options at different price ranges. Ismael Díaz Peña takes great pride in running a welcoming and efficient place, which is geared toward pilgrims as much as other visitors. Clean and modern, the hotel is right on the square near the pilgrim church of San Lesmes, and the surroundings are fetchingly historic. On weekends in the warm season, many weddings take place on the facing Plaza de San Juan. Proprietors speak English.

Just around the corner is the Hostal Monjes Peregrino (Calle Bernabé Pérez Ortiz, 1; 947-205-134; www.monjesmagnoshotel.com), run by the same English-speaking management as Monjes Magnos. The hostal is expressly outfitted for the pilgrim while still offering the comfort of private rooms with baths. Rooms are spare but elegant and airy, with large beds. Common areas have spaces to gather for food and drink. There is a gym, in case you haven’t walked enough.

Hotel Norte y Londres (Plaza Alonso Martínez, 10; 947-264-125; www.hotelnorteylondres.com; 50 rooms; €50-65), founded in 1904, is a classy boutique hotel overlooking a sweet little square in the medieval center of town. Some rooms have glass-enclosed balconies looking out on the Plaza Alonso Martínez. Warm, professional, English-speaking staff are ready to assist.

For something a little different, the Rimbombin Urban Hostal (Calle Sombrerería 6; 947-261-200; www.rimbombin.com; €55) is deep in pedestrian Burgos between the cathedral and the river. Modern, airy, and light-filled rooms have private baths. A communal kitchen and salon are convenient if you want to gather provisions from Burgos’s produce markets and have a meal in.

Burgos is a transit hub, and is well connected to the rest of Spain by all modes of ground transportation. The most convenient and easy ways to arrive are by train and by bus.

If you are driving the Autovía del Camino de Santiago, the romantically named east-west A-12/N-120 highway from Pamplona to Burgos (and onward to Santiago), your entry into Burgos will be on the east side on the N-120. The whole drive on the N-120 from Pamplona to Burgos is 200 kilometers (124 miles, 2.5 hours). From San Juan de la Ortega to Burgos it is 30 kilometers (19 miles, 30 minutes).

Burgos is 246 kilometers (153 miles) due north of Madrid on the A-1, 158 kilometers (98 miles) southwest of Bilbao and 214 kilometers (133 miles) southwest of San Sebastián on the AP-68 and A-1, and 606 kilometers (377 miles) west of Barcelona via Zaragoza on the E-90 and E-804.

Burgos has a vast array of car rental companies, including Thrifty (www.thrifty.com), Dollar (www.dollar.com), Hertz (www.hertz.com), and Avis (www.avis.com). The RENFE station also has car rentals with Enterprise (www.enterprise.es) and Gavis (www.gavis.es). The next municipality along this section of the Camino with rental agencies is León.

RENFE trains (www.renfe.com) connect to Burgos from Madrid (3-5 daily, 2.5-4.5 hours, €35), Bilbao (3-4 daily, 2.5-3 hours, €14-19), Barcelona (3-7 daily, 6-8.5 hours, €45-114), and Pamplona (2-4 daily, 2-4 hours, €14-21), among many other destinations. Burgos’s large and ultra modern Rosa de Lima Station is five kilometers (3.1 miles) north of the city. When you arrive, taxis into town (€12-15) can be shared with 2-3 other passengers, and bus shuttles (€2) transport passengers hourly to the city.

If traveling by train from Burgos, you can purchase train tickets in the city center at the RENFE office (Calle Moneda, 23, 947-209-131; Mon.-Fri., 9:30 am-1:30pm and 5-8pm, Sat., 9:30am-1:30pm, closed Sun. and holidays).

Unlike the new train station, Burgos’s Estación de Autobuses (Calle de Miranda, 4; 947-265-565) is super-central, set in from the south bank side of the Río Arlanzón across the bridge from the Arco de Santa María. Buses run by Monbus (www.monbus.es) and ALSA (www.alsa.es) cover regional and national destinations. There are 12-20 buses daily from Madrid (2.5-3 hours, €15-19) as well as from other major hubs, including Bilbao (8-9 daily, 2-3.5 hours, €9-14), León (3-4 daily, 2-3 hours, €16), Barcelona (4-8 daily, 8-9 hours, €32-55), and in France, Biarritz (one daily, 4.5 hours, €25). Autobuses Jiménez (902-202-787; www.autobusesjimenez) runs buses connecting Logroño to Burgos (10 daily). There are no direct buses from Pamplona, but the train is direct and efficient.

ALSA has a direct bus to Burgos from Terminal T4 in Madrid Barajas airport (11-14 daily, 2.5-3 hours, €15-27).

Call Radiotaxi Burgos (947-481-010; www.radiotaxiburgos.es); Taxi Burgos (634-430-234; www.taxiburgos.com), with whom you can get discounts if reserving via the internet; or Abutaxi (947-277-777; www.abutaxi.com).

The passage out of Burgos soon turns into rolling countryside and, in a little over 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) arrives at the village of Tardajos (pop. 794). Though little of historical significance is left here, in the 10th century this village had three churches. Long before then, there was a Roman villa here, and possibly before that, a small Celtiberian castro (settlement).

This is a great place for a rest at the energetic and upbeat Café Bar Ruiz (Calle Pozas, 10; 947-451-433; €4-5), which churns out creative breakfast sandwiches intended to fuel a trekker, such as egg-in-a-hole with cheese and ham.

Two popular albergues offer accommodation if you wish to stop here. The Albergue La Fábrica (Camino de la Fábrica; 646-000-908; open all year; 14 beds; €12) opened in 2014 in a restored old stone building that was once a flour mill. They have dorm-style bunk beds as well as private rooms, meals, and good hospitality.

The Hotel-Albergue La Casa de Beli (Avenida General Yagüe, 16; 629-351-675; www.lacasadebeli.com; open all year; 30 beds; €10) is a new pilgrims’ hostel, opened in 2016, with beautiful thick stone walls and elegant private rooms (€35-45) along with dorm-style sleeping (30 beds at €10). The albergue also offers a warm welcome, tasty meals, and a relaxing garden in back.

Tardajos also has a municipal albergue (Calle Asunción, s/n; 947-451-189; 18 beds in three dorm rooms; donation; mid-Mar.-Oct.31) operated by volunteers from the pilgrim association, Asociación de Amigos del Camino de Santiago de Madrid.

Rabé de las Calzadas (pop. 214) has a pretty chapel, Iglesia de Santa Marina (Calle Santa Marina, 4), typically open daily, where you can get a stamp in your pilgrim’s credential as well as enjoy the heavily fortified stone walls of the 13th-century transitional Gothic church. Storks love the building and in spring you may see them active in their nests on the bell tower.

The S Albergue Liberanos Domine (Plaza Francisco Riberas, 10; 695-116-901; www.liberanosdomine.com; open year-round; 24 beds; €8) opened in 2009 and is simple but flawlessly clean and efficiently run by joyous hospitaleras attuned to the old tradition of pilgrim hospitality on the Camino. They also serve a fresh, simple, and satisfying communal dinner, usually offering soup, salad, pasta, and dessert (€8), and breakfast (€3.5).

About 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) after leaving Rabé de las Calzadas, you’ll pass a section of the Camino, several meters long, known as Pedras Sagradas (approximately Km 473.8). Here, passing pilgrims have built mounds and cairns from the stark-white local fieldstones, giving the wild terrain the feel of a Shinto shrine.

You are now ascending to the Cuesta de Matamulos, a hill that rises 950 meters (3,117 feet) above sea level. Here, the horizon opens up to a glorious vista below, followed by a dramatic descent into Hornillos del Camino. This stretch is stunning in all seasons, but especially in spring, when red poppies speckle the pale green fields with splashes of color.

The name Hornillos (“little oven” or “little kiln”) hints at some past industry, perhaps smelting, but this town (pop. 58) was and remains an important stop for pilgrims for food and shelter in this off-the-beaten-path country.

The 13th-century Gothic church of San Román on the Plaza de la Iglesia holds the highest point in the village. In the 12th century, monks from Saint Denis in Paris founded a monastery here that later was transferred to Benedictines in south-central France. Inside the church is a sculpture of the famous Black Madonna of Rocamadour, a reminder of this French connection. Sloping down from the church toward the main street is an inviting village square with Fuente del Gallo, the Rooster’s Fountain, in the center.

On the main street, facing the church and square, is the lively Bar Casa Manolo (Calle Real, 14; 947-564-798), serving refreshments, tapas, and sandwiches in the bar and sit-down meals in the dining room, with fresh and good home-cooked options on the daily menú de peregrino (€10).

A favorite albergue, El Alfar de Hornillos (Calle Cantarranas, 3; 654-263-857; www.elalfardehornillos.es; 20 beds; €9) is open from Apr.-Oct. It is family run, in a comfortable space with an outdoor patio and a family-style dining room. They also offer a communal dinner (€9; they are especially known for their paella) and breakfast (€3). Sleeping options are in three rooms, one with four beds, one with six beds, and the third with 10 beds.

De Sol a Sol (Calle Cantarranas, 7 bajo; 649-876-091) is situated in a family home-turned-hostal with shared kitchen, dining area, lounge, garden, and clean and homey sleeping spaces with seven rooms, one being a room with bunkbeds (€10/bed) and the others double rooms with private baths (€40-50). For many, it is the owner, Samuel, that makes this place special; he welcomes everyone warmly and wants to help in any way that he can. When Martin Sheen walked the Camino with his son, Emilio Estévez, and grandson, Taylor Levi Estévez (before the father and son came back to film The Way), the three arrived at Samuel’s place, but it was full. Out of concern that they have a place to stay, Samuel sent them to his mother’s home, where Taylor met Samuel’s sister and became smitten; eventually, the two married.

This little oasis, the Arroyo de Sanbol, also called Sambol, has no inhabitants other than the hospitaleros and the pilgrims who stay in the albergue. There is pilgrim lore regarding its natural spring, located a few meters south of the Camino. That spring may be why people built the monastery of San Baudillo here in the 11th century. Though little remains of San Baudillo, the spring still flows and some pilgrims say it has curative powers. (Many claim that washing their feet in the locale’s freshwater pool relieves them of foot problems for the rest of the Camino.)

Here in this sparse outpost is the municipal, beehive-shaped Albergue Arroyo de Sanbol (606-893-407; €5 for a bed; €7 for dinner), which offers rustic—no plumbing or electricity—but impeccably clean and charming accommodation for up to 12 pilgrims. If you desire simplicity and to sleep in deep silence under a big starry sky, this is your adventure. It comes with a great pilgrim meal shared around a large wooden round table. Bedtime is at 9pm.

The village of Hontanas (pop. 73) is named for the many sources of water that flow through the area. (The name is born from fuentes in Spanish, fontaines in French, and fons and fontibus in Latin.) The central church in Hontanas is the Iglesia de la Immaculada Concepción (Calle Iglesia, 3), a sturdy 14th-century structure that defines the horizon as you approach. It has a lovely modern twist, a niche portraying a strong ecumenical feel with images of leaders and holy people from many faiths across the world, honoring all of humanity’s sacred traditions. For some pilgrims, this open and peaceful atmosphere is reason enough to stay in Hontanas.

The excellent bar and restaurant Mesón El Puntido (Calle Iglesia, 6; €4-10) turns out fresh and creative meals morning to night. It’s set in a historic stone and wood building along the main street, across from the church.

Next door, Hotel Fuentestrella (Calle Iglesia, 4; 947-377-261; www.fuentestrella.com) is modest but serene and clean, with five double rooms (€35-45) and one triple room (€55), all with private bath. An adjoining restaurant offers good meal options—home-cooked dishes, both on a traditional menú del peregrino as well as different a la carte offerings. A dining terrace out on the small square adds to the ambiance.

Albergue Santa Brigada (Calle Real, 19; 609-164-697; open Mar.-Oct.; 16 beds in three rooms; €8) is a pretty and clean place to stay. An adjoining bar and shop sell food. They also serve dinner (€8) and breakfast (€3).

Founded in 1146 by the French order of Antonines, the present ruins of the monastery of San Antón Abad stand alone in the nook of a small ravine, mostly to the left of the Camino. Largely Gothic and from the 14th century, the monastery existed in service to pilgrims as a hospital. The Camino romantically passes under one of the monastery’s half-crumbled arches. In the Middle Ages, this site contained a sheltered porch area where pilgrims who arrived after the monastery gates had been locked for the night could find a protected place to sleep. There, the monks also left food and drink in two stone niches set within the wall. The niches survive today, and pilgrims fill them with notes, poems, and other offerings.

Pedras Sagradas (sacred stones) on the trail just past Rabé de las Calzadas

partially standing walls in the ruins of San Anton’s medieval monastery

Bar Casa Manolo in Hornillos del Camino

Before fully passing under this arch to continue on the Camino, follow the wall to your left to see what else survives of the ruins. Standing in the middle of the monastery, with its collapsed ceiling, decaying Gothic walls, and grass growing across the monastic floor, is a hauntingly beautiful experience. Look at the windows to find the one showing the symbol of the Antonines, the form of a Tau cross: a cross with three arms, somewhere between a T and a Y. Medieval brothers baked the Tau cross into loaves of bread in order to heal pilgrims of illnesses—especially Saint Anthony’s Fire. The Tau was (and by some, still is) considered an esoteric symbol through which Saint Anthony comes to one’s aid and administers cures. In recent Camino lore, the Tao cross is also associated with the Templars, who like the Antonines were on the Camino to protect and serve the pilgrims.

You can still sleep in the ruins, in a simple small shelter built against the side of one of the standing moanstery walls, and benefit from the legacy of kindness and a simple but good meal at the donation-based Albergue San Antón (Open Oct.-Apr.; 14 beds). The sleeping area and toilets are very clean. There is water but no hot water and no electricity. Dinner is by candlelight.

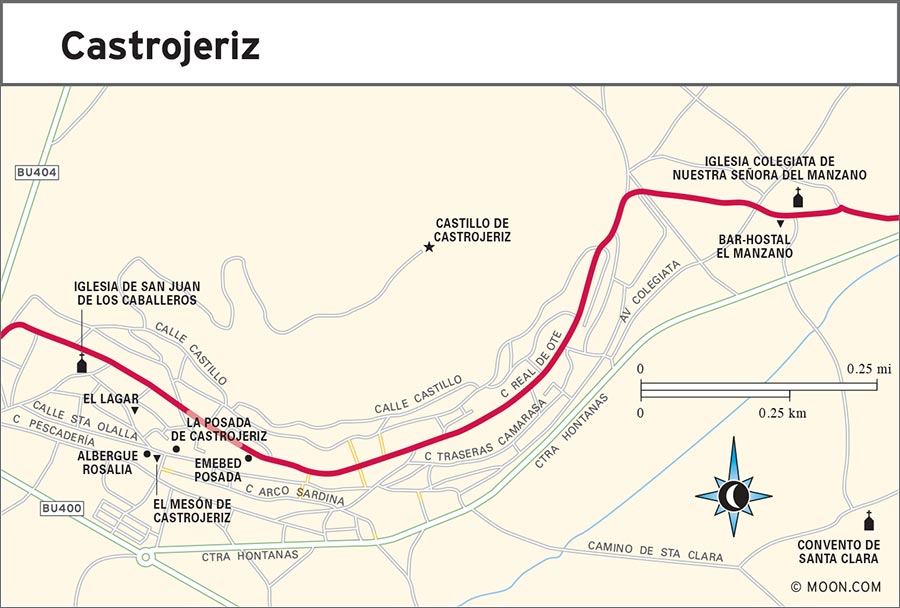

The approach to the hilltop town of Castrojeriz (pop. 552) is beautiful: the Iglesia del Manzano appears on the horizon, tucked into the protective foot of the castle hill, and grows slowly larger as you approach. The town is small and seemingly sleepy but full service, lively, warm, and with a vibrant community that comes to life after the siesta hour. Underneath the entire town are interconnecting tunnels that hide wine cellars. They are privately owned, but you can get a glimpse of these if you stay in the Posada Emebed, or just ask anywhere you alight if you can get a glimpse of the subterranean world.

Castrojeriz was an Iron Age Celtiberian site that was later dominated by Romans. In the early Middle Ages, Visigoths took this hill, and soon after them, Iberian Muslims and Christians alternated control over the town many times, until it fell permanently into the hands of the latter. Castrojeriz was incorporated into the Kingdom of Castile and León in 974 and was an important commercial and pilgrim town. At one point it had seven pilgrim hospitals and five churches. The Jewish population here was highly valued and protected, and some vestiges of their lives here remain, especially if you stop for a drink or a meal in El Lagar, a bar and restaurant set over what most likely was once the synagogue.

The Camino passes into the center of Castrojeriz, built on the lower half of the hill’s slope, after passing the Iglesia del Manzano on the path’s right, and all the while the castle on the hilltop far above, towering protectively over the town, also stands on your right.

The Iglesia de Nuestra Señora del Manzano, Our Lady of the apple tree, stands on the site where Mary miraculously appeared to Saint James, who was passing through on horseback. When Saint James neared an apple tree in the orchard that grew here, he saw Mary, and his horse left hoof prints in stone marking the spot where he saw the image. Local lore says that rock is still there, on the south-side entrance to the church.

This is the Virgin whose numerous miracles King Alfonso X (1221-1284) of Castile and León celebrated in his sacred songs, the Cantigas de Santa María. Out of a total of some 427 songs, five of them were dedicated to the miracles of this Mary, who especially looked out for stonemasons. Among her miracles, she’s credited with saving several masons from falls that would have been fatal without her intervention.

The church foundations reach back to the 11th and 12th centuries, though the reconstructed vaults date to the 16th to 18th centuries. The image of Alfonso X’s miraculous Madonna, the 13th-century polychrome-painted stone statue, stands in the heart of the altar, an interesting depiction of Mary holding Jesus in a complete profile view; Mary herself appears as you might see classical images of the Greek earth goddess, Demeter.

This castle’s medieval foundations carry aspects of the town’s earlier occupants: the Visigoths built a castle, here, too, and incorporated aspects of the earlier Roman fortress into it (and Romans doubtlessly used aspects of the Celtiberian castro). The builders of the medieval fortification used aspects of both Roman and Visigothic foundations.

Castrojeriz’s Igelsia del Manzano, village, and protective castle hill

The medieval castle actually survived intact until 1755, when it crumbled into ruins during an earthquake that more famously destroyed Lisbon. Today, about one-third of the heavily walled, fortified castle survives, most of it having crumbled into poetic heaps except for one central wall that stands out straight into the sky.

If you want to understand the surrounding landscape’s topography, and enjoy exploring castle ruins, make the climb to the top of the hill and enjoy its view over the meseta. Both Iberian Christians and Muslims controlled the territory from this hill, on and off in the early Middle Ages.

The heavily fortified, largely Gothic, 13th-century Iglesia de San Juan (Calle Cordón, 22; 947-377-011) has, among its sacred symbols, a beautiful and unusual window in the shape of a five-pointed star. The star represents the five wounds of Christ; in medieval sacred geometry, especially for stonemasons and builders, it was the ancient Pythagorean sign of wholeness and divine perfection. In the ancient world, the five-pointed star represented Venus.

This church was originally a Romanesque building, and these foundations define the structure. It was later reformed with Gothic, Mudéjar, and Baroque elements. Ornate Mudéjar woodwork and painting forms the ceiling of the beautifully preserved cloister. In the cloister garden, notice the solar disk tombstones, which are common across Basque Country and Navarra and signify the blending of earlier pagan ideas with later Christian ones. The tombstones are round and engraved with images of intersecting arms that suggest both a radiating sun and an equal-armed cross. In pagan religion, the sun was considered the supreme life-giving and life-regenerating power, an association that translated smoothly to the image and concept of the cross and its representation of Jesus as the bringer of light and rebirth.

On the southeast outskirts of town are the restored convent ruins of Convento de Santa Clara (Camino de Santa Clara; 947-377-011; www.castrojeriz.com; 9am-7pm), with a lovely Gothic monastery church and walled-in compound surrounding it, containing resident and garden spaces. Alfonso X founded this convent in the 13th century, though builders constructed the current church in the 14th century and it was massively restored in the 18th century.

Once a Franciscan monastery, today the convent is run by Clarist nuns and thus is called Santa Clara. They make their living providing large-scale laundry service for businesses, and selling special pastries. (Try their puños de San Francisco, Saint Francis’s Cuffs, a spongy, cuff-shaped vanilla cake roll filled with rich cream, which you can buy directly from them at a the convent.) Daily mass is at 8:30pm in the convent church; the hours may be earlier in winter. Additionally, Lauds is at 8am (7:50 on Sundays and holidays); the Eucharist at 8:30am; Rosary Benediction at 5pm; and Vespers at 8:20pm (7:30 on Sundays and holidays).

Castrojeriz has some vibrant festivals that all involve festive processions, traditional attire, song, dance, and music. Fiesta de San Juan—Saint John’s Festival—occurs every June 24, celebrating both the summer solstice and Saint John the Baptist’s feast day; the Fiesta de Ajo—Garlic Festival—happens in mid-July, and the Fiesta de Sejo, the town’s sacred celebration of their patroness, Nuestra Señora del Manzano, is on the second Sunday in September, with processions and celebrations of the town’s folk traditions in music, dance, and food.

Like so many towns across Spain, at siesta hour Castrojeriz can feel like a ghost town, then suddenly explodes into life and activity as people leave their homes, meet friends in cafés, do afternoon and evening shopping, go to church, stroll about, and stop to gossip with neighbors. During this time, late afternoon into evening, the small squares and narrow streets hum with activity, and locals will make you feel a welcome part of it.

On entering town, break for a drink, a snack, or a meal (really good pizza is the main option, as well as the ubiquitous tortilla, Spanish omelet) at the inviting Bar-Hostal Manzano (Avenida Virgen del Manzano, 1; 620-782-768) right beside the Iglesia del Manzano. You can also check in for the night (double rooms with bath, €35) for a basic, clean, and peaceful rest. The owners sustain a remarkable sense of hospitality as thousands of tired pilgrims walk past on their way to Castrojeriz’s center, another few hundred meters ahead.

El Lagar (Calle Cordón, 16; 947-377-441) is a great tapas bar and restaurant for home-cooked meals, but it also was once the likely location of Castrojeriz’s synagogue. El Lagar, which means “the wine press,” is named after the wine press that once operated here and is still located on the premises.

El Mesón de Castrojeriz (Calle Cordón, 1; 947-378-610), the bar and restaurant connected to La Posada hotel, offers a good dinner menu (including a €10 menú del peregrino) featuring traditional Castilian cuisine from this region, such as cecina (dry cured beef), cocido (a pot au feu-style stew with meats, garbanzos, cabbage and other vegetables), various lamb dishes, and rice pudding.

Among the town’s seven albergues, the super-clean and charming Albergue Rosalia (Calle Cordon, 2; 947-373-714; open Mar.-Oct.; four rooms on two floors; 32 beds; €10) is a top pick and wins points for offering single, generous-sized beds—not bunks—arrayed in several small dormitories with rustic low timbered roofs, stucco whitewashed walls and sleek wooden floors. An honor system in the wonderful country kitchen allows pilgrims to cook at their leisure and pay for stocked items that they use, such as eggs, coffee, and pasta.

Of the five hotels in Castrojeriz, the centrally located Posada Emebed (Plaza Mayor, 5; 947-377-268; www.emebedposada.com; 10 rooms, each very different; €50-70) most feels like an elegant medieval manor (though it dates to the 19th century) in the quality of the furnishings and the stately stone walls, while possessing all the modern comforts: large rooms, comfortable beds with plush linens, private terraces with café tables, and a great view across the meseta. Additional services include massage therapy (arranged in advance) and bikes for exploring the surrounding area. If you stay here, ask the English-speaking owners to show you the underground wine cellars.

La Posada de Castrojeriz (Landelino Tardajos, 5; 947-378-610; info@laposadadecastrojeriz.es; €45) is a bit more basic, but rooms are still spacious and elegant. A nice interior courtyard patio has a good library and is an enjoyable space in which to relax.

One of the most beautiful vistas of the meseta is 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) after leaving Castrojeriz. A steep climb leads up the slope of the high ridge, Alto de Mostelares, (900-meters/2,953 feet). You are well rewarded for the hard effort to get here with limitless views of the yellow and green wheat fields of the meseta looking like a billowing patchwork quilt. Pilgrims have built stone mounds on this hilltop that add to the beauty. Be careful on the descent: The path is at a steep angle and is paved, making it easier to slip. High winds also gust on this hilltop and across the vast wheat fields you are hiking toward. At the end of the slope where the trail levels out again you will spy another reward, the refreshing Rio Pisuerga with the Ermita de San Nicolás settled along its eastern bank.

There is a special feng shui to the surviving vestige of this 12th-century hospice and hermitage, Ermita de San Nicolás, now a refuge. The single rectangular stone building stands at the base of a dale, with a sweeping horizon through wheat fields beyond. The Rio Pisuerga flows nearby, crossed by the lovely Puente de Itero, a bridge with 11 arches dating to Alfonso VI’s rule in the 11th century.

Before crossing the bridge, stop to visit the inside of the hermitage and consider staying at S Ermita de San Nicolás (947-377-359; open mid-May through September; 12 beds; €5). It is well run and serene, if rustic. Originally run by Benedictine monks, today it is run by Italian hospitaleros, who offer excellent hospitality and serve a communal meal by candlelight (only the bathroom has electricity). The river burbling nearby completes the calm atmosphere. At night, this a great place to view the Milky Way.

A little over 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) after crossing the bridge next to the hermitage, you’ll pass a 16th-century church as you enter into the village of Itero de la Vega (Km 438), an oasis in the middle of vast swaths of wheat fields. The village’s Hostal Puente Fitero (979-151-822; eight rooms; €30-40) is also an albergue (22 beds; €6) bar, restaurant (with menú del peregrino for €10), and little food shop. The whole establishment is well run and impeccable.

Before you leave, stock up on water and food if you need it; the next stretch is 8.5 kilometers (5.3 miles) without support services until you reach Boadilla del Camino. Three kilometers (1.9 miles) after Itero de la Vega, you’ll cross the Canal de Pisuerga, a manmade canal built to irrigate farmland in this wheat-growing territory, which defines the 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) to Boadilla.

In the center of Boadilla, you pass the farming village’s most distinctive feature: the Rollo de Boadilla, a towering and intricately carved Gothic cross covered in scallop shells. The 15th-century cross has a macabre history attached to its artistry: This was a post of justice, and people found guilty of serious crimes were hanged here. Its tradition comes from the era of Enrique IV (1425-1474), who granted Boadilla self-governance from outside powers. Near the cross is the 15th- and 16th-century church of Santa María, a solid structure that was restored and reformed many times into the 18th century.

Boadilla del Camino’s medieval post of justice, the Rollo de Boadilla

Off the same square as the church, Albergue En El Camino (Plaza el Rollo; 979-810-284; www.boadilladelcamino.com; Mar.-Oct.) is a favorite pause, in part for its large garden and pool, but mostly for the easy-going warmth of its hospitaleros, who also offer great food and drink. They offer 70 beds in four large dorm rooms (€8/bed), and an evening meal for €10; breakfast is €3.

Approximately 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) after Boadilla del Camino, the Camino meets up with and runs parallel to the left of the Canal de Castilla, which was built for irrigation in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is rife with frog, toad, and bird life, as well as wild yellow irises, four types of lizards, and water snakes. From here, another 4.8 kilometers (3 miles) remain to Frómista.

lock of the Canal de Castilla just before Frómista

To enter Frómista (pop. 790), the Camino crosses a bridge over the Canal de Castilla at the point of an elaborate damming gate that controls the flow of water. You then enter on the main road into town, passing the train station on your left.

Sunflowers, wheat, and barley cover the fields surrounding Frómista, making the horizon a gorgeous melding of bright blue sky and golden undulating earth. In spring, that horizon transforms into a pale green speckled with red poppies. This territory has long been the heart of Spain’s breadbasket. Celts and Celtiberians cultivated the land here, and Romans called this town frumentum (“cereal” in Latin). By the 11th century, Frómista was an important religious and market center on the Camino. It also was home to an ancient Jewish community that continued to thrive into the 14th century. In 1492, when the Spanish monarchs Isabel and Ferdinand forced conversion or expulsion upon its Jewish and Muslim communities, the economy and agriculture diminished with their decline, here as well as across significant parts of the country.

Frómista today is still about wheat and bread—this is its main industry—but also about cheese, which is celebrated at an annual festival in July. If you can’t be here for the festival, be sure to visit the local art exhibit space, café, and sale venue for local cheeses, La Venta de Boffard.

For a town of nearly 800, Frómista feels more like 200, but you’ll nevertheless find several nice places to eat and sleep. The outdoor cafés surrounding the church of San Martín probably offer the best atmosphere, but don’t overlook the more intimate square behind the Iglesia de San Pedro, also with several good cafés and inns.

Frómista has three churches: the Iglesia de San Pedro, fortified, sturdy, largely unadorned but with elegant vaults, from the 13th century; the largely 16th-century Iglesia de Santa María del Castillo; and the reason why people visit Frómista, the Iglesia de San Martín, one of the jewels of medieval Iberia, built in the 11th century. San Martín is worth all the time you can offer it, both to take in all the stone images engraved in the corbels and capitals inside and out, and also to enjoy the visceral feeling of being in a sacred space built to perfect proportions for the human form.

The Iglesia de San Martín de Tours (Plaza San Martín, 3; 979-810-144; Apr.-Sept., daily, 9:30am-2pm and 4:30-8pm; €1, free on Wed.), was built in AD 1066 and once belonged to an adjoining Benedictine monastery that no longer stands. It is considered the purest French Romanesque church in Spain, and in many ways, it is a prototype for understanding the proportions, harmony, and richly expressive sculpture of the Romanesque style in France as well. Step inside to take in the pleasing pale yellow domed ceiling sweeping overhead, or the many carved capitals recounting Biblical, historical, moral, and humorous tales. A personal favorite, on the second pillar from the back end of the church, on the left in the central nave, depicts the vain raven with a loaf of bread in his beak, and the clever fox who wanted to steal it. The fox praised the raven’s magnificence, and when the raven opened his mouth to respond, the loaf fell and the fox took off with it. The imagery culminates in the statue of Jesus at the altar, and, to his right, the compelling dark-toned wooden sculpture of La Virgen de la Acogida, the Virgin of the host. Another aspect of the intimate artistry is how the proportions and shape create perfect acoustics. If you sing here, the resonating sound will wash over you and transport you to another level of sacred experience.

sculptures on Frómista’s Iglesia de San Martín

Once, risqué corbels—a veritable Kama Sutra of the Middle Ages—adorned the church’s exterior, but many of these were replaced with sedate floral and geometric patterns when the church was restored between 1896 and 1904. (Ironically, those sexually explicit sculptures reflected not inhibition, but an earth-bound and honest view of humanity in 11th-century Europe. In fact, at the time, it was the norm in Europe to show that chaotic world on the outside of churches, and then invite the nonliterate populace to step inside the church, where the chaos and wildness of life is controlled and tamed.)

A few of the saucy corbels do remain, along with many expressive and idiosyncratic characters that depict local folklore and stories. Look especially for the contemplative sage wearing a turban, the woman who has just given birth, the giant baring his sharp teeth, and the playful animals with charming expressions. There are also three sculptures of waterfowl (ducks, geese, and swans), considered symbols of fidelity and also guides and gatekeepers of the heavens. They also may have an association with the medieval-to-early modern-game, the Game of the Goose, where they also act as guides and guardians of pilgrims on the Camino.

In the third week of July is the Feria del Queso (979-810-001; administracion@Frómista.es), the cheese fair where you can taste the artisanal cheeses (largely sheep’s milk) and meats (including chorizos and morcillas) produced in the region.

To purchase gourmet goods for a picnic before heading back on the trail, especially the sheep’s milk cheese from Frómista, queso de oveja Boffard, stop at La Venta de Boffard, a shop as well as a café, bar, restaurant, art gallery, and garden.

La Venta de Boffard (Plaza San Martín, 8; 979-810-012; www.laventafromista.com; €10-12) is an art exhibit space, music venue, and a food-lover’s paradise, combining a love for Palencia’s foods (cheese, charcuterie, homegrown greens) with art and ethnography. Run by two English-speaking sisters from Palencian and Basque backgrounds, they welcome everyone warmly and hold pilgrims as special guests. In this spirit, they prepare a gourmet menú de peregrino as well as an array of other offerings, such as savory toasts with bellota (acorn-fed cured ham), Boffard cheese, and smoked salmon, as well as desserts such as white chocolate flan. The Iglesia de San Martin, just outside on the square, adds to the artsy atmosphere.

El Apostal (Avenida Ejército Español, 5; 979-033-209; www.hostalelapostal.com; €10) is frequented as much by locals as by pilgrims. They offer a straightforward and fresh menú del dia that offers three courses with many choices, including vibrant fresh salads, grilled fish, and stuffed red peppers, with just-plucked Persian melon for dessert.

S Restaurante Doña Mayor (Calle Francesa, 31; 979-810-588; www.hoteldonamayor.com; €18) is more than a hotel; it’s also a great restaurant and bar. Departing from the typical menu, the Doña Mayor offers an a la carte splurge with dishes such as lemon- and rosemary-grilled salmon, a vegetarian sauté of local vegetables with chickpeas and artichoke mayonnaise, and two varieties of lasagna (spinach or meat). Desserts include blackberry cheesecake, brownies, and lemon-blueberry sponge cake, served on slate planks. In good weather, you can choose to dine in the private garden.

Frómista has a wide array of accommodation among its four albergues and almost a dozen pensions, hostales, and hotels. Nothing distinguishes the albergues, but the range of other accommodation might entice you to splurge for private digs; if you share a room with one or two other pilgrims, the price can be quite sweet.

Named after the 11th-century patroness of the Iglesia de San Martín, the Hotel Doña Mayor (Calle Francesa 31; 979-810-588; www.hoteldonamayor.com; 12 rooms; €70-100, which typically includes breakfast) is a modern building in the old center of town with an excellent bar and restaurant. All spaces—guest rooms and dining—are contemporary designs with earthy and appealing woodwork along the walls and floors. Large floor-to-ceiling windows let in copious light. They offer a large buffet breakfast with gluten-free options (€9). Proprietors speak English.

Hostal El Apostal (Avenida Ejército Español, 5; 979-033-209; www.hostalelapostal.com; €30/45/60 with breakfast) is not only a great restaurant but also a lovely inn on a quiet square next to Iglesia de San Pedro. Rooms are a mix of modern and cozy. Proprietors speak English.

Across the street from Iglesia San Pedro, S Hostal San Pedro (Avenida Ejército Español, 8; 979-810-016; www.hostalsanpedrofromista.com; €30-55) feels like home. The welcoming and engaging proprietor, July (pronounced who-lee), has designed her boutique-like hostal with great artistic flair. Rooms are painted with saturated, earthy colors, and the floors are sleek gray tiles. Bathrooms are spotless. The whole place is decorated with restored antiques from 19th- and 20th-century Castile. July offers a good buffet breakfast (€4.50) in the communal dining room.

Three trains daily depart Madrid, with a change in Valladolid, for Frómista (2.5-4.5 hours; €27-40).

You will walk on a dirt path that runs parallel to the right side of the P-980 from Frómista to Población de Campos (3.4 km/2.1 mi).

Just a few hundred meters before arriving in Poblacion de Campos (pop. 137), a village founded in the 11th century, you pass the lyrical hermitage, Ermita de San Miguel, a small chapel with transitional Romanesque corbels and Gothic doorway from the 13th century. The villagers of Poblacion de Campos have arrayed picnic tables here for pilgrims to enjoy a rest in the shade of the poplar trees, an oasis in the meseta.

The village has two other churches. The 16th-century Iglesia de Santa María la Magdalena is on the village’s highest hill. Just below it is a hermitage set almost below ground—or, more accurately, the ground level has risen from later building over older settlements—making for a slight climb below street level to enter into the earthy and acoustically rich 13th-century Ermita de la Virgen del Socorro.

The rural hotel, Amanecer en Campos (Calle Fuente Nueva, 5; 979-811-099; www.hotelamanecerencampos.com) offers lunches and dinners based on home-cooked dishes passed down for generations, including paella, Castilian soups, dishes from locally harvested vegetables, and homemade desserts. They also have 14 country-inn-style rooms (floral bedspreads, colorful walls with floral paintings) for €30-45, all with private baths; breakfast is €3.

The Albergue La Finca (on the P-980 across the road from the Ermita de San Miguel; 979-067-028 and 620-785-999; www.alberguelafinca.es; 20 beds; €10) is a stone, brick, and terracotta farmhouse with wonderful modern interiors—wide-planked wooden floors, modern bathrooms, a large country-style dining room, and an open lounge and kitchen with copious natural sunlight. A garden with pool and Japanese bridge are a calm space to rest. Beds (singles, not bunk beds) are in inset wall nooks with curtains, offering privacy. The restaurant and bar serves a menú del peregrino (€10) or an a la carte menu, specializing in regional dishes and Castilian wines.

Población’s more basic municipal albergue (Calle Escuelas, 17; 979-811-099; €5) has 18 beds in one dorm room. Both albergues are open all year. The town also has three bars for meals, snacks, and drinks, and a shop for provisions.

Soon after Población de Campos, the Camino splits. Both paths lead to Villarmentero de Campos. The path heading to the right eventually becomes a riverside path and adds 0.9 kilometers (0.6 miles) to the walk. The other continues straight on the P-980 road that you have been on since Frómista.

The river path is more appealing and passes along the life-giving waters of the Río Ucieza, where you’ll see stands of poplar trees and rich bird life, including European robins, canary-like serins, green woodpeckers, owls, hawks, and falcons.

The P-980 leads directly to Villarmentero de Campos (pop. 23). If you took the riverside path, the town is connected by a few-hundred-meter-long country road from the river—look for the distinctive white teepees in a field that identify the village. The 16th-century village church, Iglesia de San Martín, is interesting for its Mudéjar—Islamic-style—ceiling. (To go inside, ask a local if someone can unlock it.)

La Casona de Doña Petra (Calle Ramón y Cajal, 14; 979-065-978; www.lacasonadepetra.com; €35-55) with 12 private rooms, offering meals (€15) and breakfast (€5), was once a pilgrim hospice that operated until the late 17th century. Interestingly, when the present (English-speaking) owners restored the place, they discovered a hidden box containing an ancient deed in Hebrew that identified a Jewish resident as the owner.

The Albergue Almanecer (Calle Jose Antonio, 2; 629-178-543) offers 18 beds, three teepees (the very ones you saw when you approached the village), and three outdoor hammocks. For outdoor sleeping and sharing the grounds with wandering farm animals (donkeys, chicken, geese), the hammocks (€3) and teepees (€3; the ground is hard) give a novel twist to pilgrim lodging. Inside are comfortable bunkbeds (€6). The couple who runs Almanecer is celebrated for their homemade communal meals, prepared with care and passion. The dining area feels like a country farmhouse, with a wonderful long wooden table.

Both paths—the P-980, or the dirt road back to the river path—lead next to Villalcazar de Sirga. I recommend that you continue on the riverside path, where just before Villalcazar you’ll arrive at Ermita de la Virgen del Río after crossing a bridge over the Ucieza river. Once a 12th-century Romanesque church, now largely from the 18th century, this hermitage remains an active sacred center for the people of Villalcazar de Sirga. This Lady of the River has a story similar to that of Logroño’s Virgen del Ebro, who was found floating in the Ebro river: Locals found the Virgen del Río’s icon floating up the Río Ucieza after a flood, and this shrine marks the spot where she came ashore. The brotherhood of the Virgen del Río, formed in 1650, carries on annual celebrations in her honor on the Monday after Pentecost Sunday (seven Sundays after Easter). The hermitage is open only on feast days, but has a generous covered porch where you can rest as well as some picnic tables on its grounds.

teepees for peregrinos at the Albergue Amanecer in Villarmentero de Campos

Iglesia de Santa María la Blanca in Villalcázar de Sirga

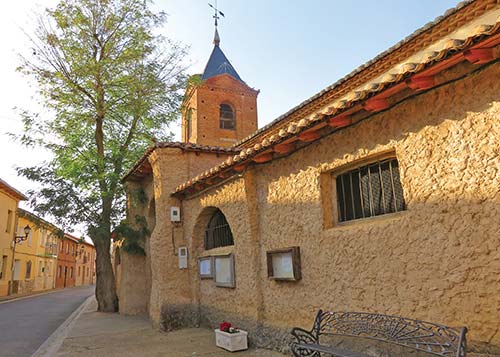

Iglesia de Santiago in Carrión de los Condes

Just before entering Villalcazar de Sirga (approximately 30 meters/100 feet), if you have been walking the river side path, is Palomar del Camino (Kilometer 10 on the P-981; 653-916-600; www.palomardelcamino.com; menú del peregrino €10, a la carte €15), a good place for food and drink on the left side of the Camino and located in the round, white-stucco 19th-century dovecote (palomar) with shady terrace seating. A nice alternative to the lusty meats, stews, and casseroles of Castilian cuisine (which you will find in the restaurants in Villalcazar’s central Plaza Mayor), it serves up nourishing and tasty lunches such as fresh salads and empanadas. Proprietors speak English.

As you enter the small village of Villalcázar (pop. 172), notice the mounds and Hobbit-like holes with doors in the hillsides. These bodegas are where local families make and store their wine, as well as their harvest, cheeses, and cured meats. They are also social gathering places; in summer they can be a surprisingly cool.

Villacázar revolves around its celebrated church, Iglesia de Santa María la Blanca, and the Madonna, La Blanca, that it houses. In the 13th century, King Alfonso X of Castile and León wrote, or commissioned, twelve of his sacred songs, Cantigas, about La Blanca’s miracles. In fact, La Virgen Blanca performed so many stunning miracles—from restoring a blind man’s sight to lifting a 24-pound weight a sinner was sentenced to carry—that Villalcázar became an important pilgrimage destination, and the Camino was actually redicted in the 13th century to pass through it.

It is possible that the Templar Knights used Villalcázar as a base from which to protect and serve pilgrims on the Camino. However, it seems more likely that this service was fulfilled by another knightly order, the Order of Santiago, though tradition and lore still refer to this as a Templar town. The Templar residence, the cloister, the towers, walls, gates, and pilgrim hospices were all largely destroyed by the 1755 earthquake or soon crumbled thereafter. That the church is still here is something. What remains feels epic: you feel the church’s towering height as you walk into town.

Built in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, the transitioning Romanesque-to-Gothic Church of Santa María la Blanca (Plaza Mayor, s/n; 979-880-854) is like a fortress, and probably was used as one in times of duress. The high-porched entrance has Christ in Majesty and the Tetramorphs on the upper sculptured line; below them is Santa María la Blanca.

Inside, the church is unusual in that it has three naves and two crossings. You’ll find the sculpture of the miraculous Mary of Alfonso X’s Cantigas in the center of the altar’s retable. This sculpture is also distinct in that it is carved of stone—like that of Castrojeriz’s Virgen del Manzano—and not wood, the more common medium of revered Marian icons along the Camino.

You’ll easily locate the chapel dedicated to Santiago; it is in the end of the transept that includes the church’s beautiful and unusual rose window. With 14 petals, rather than the more typical 6, 8 or 12, this window is also aligned to let in the midday sun.

The posted visiting hours are May-Oct.15 10:30am-2pm and 4:30-7pm; Oct.16-Apr. Mon.-Fri. by arrangement, Sat.-Sun. and holidays 12-2pm and 5-6:30pm; visits are free unless you arrange a guided tour (€1). Despite these posted hours, the church, especially in the early autumn, is typically open in the mornings, but the afternoons are less certain.

S Mesón de los Templarios (Plaza Mayor; 979-888-022; www.mesonlostemplarios.com), next to the church, and S Meson de Villasirga (Plaza Mayor; 979-888-022; www.mesonvillasirga.com) are run by the same proprietor, Pablo Payo. He opened the former in 1984 and the latter in 1965. Both are on the Plaza Mayor, kitty-corner from each other. Both serve classic Castilian food, medieval-banquet style, including roasted meats on bread plates meant to be eaten, large casseroles, and special pastries, including the anisseed-laced ones you may have smelled on entering the village. These are among the Camino’s most traditional (and sought out) restaurants. Payo opened the original, Mesón de Villasirga, to better serve pilgrims’ culinary needs, which it delivers in a large communal hall. The Mesón de los Templarios is also intended for pilgrims and other visitors, but is a bit more formal and transports you more to the Middle Ages. People habitually drive from Burgos and Madrid just to eat at both places, where a meal typically can run €15-25. If one place is fully booked or closed, be sure to try the other.

S Confitería La Perla Alcazareña (Calle El Ángel, 4; 979-888-020; www.pastelvillasirga.com), family operated for four generations (since 1870), lures locals and visitors alike with the butter-and-anise aroma that wafts from its ovens down all the streets of this little village. The bakery’s creations include traditional Castilian almond cookies, almendrados, and little almond cakes, amarguillos. They also supply the dessert served at Meson de los Templarios and Meson de Villasirga. You’ll find the bakery on the Camino as it is about to depart the village, on the right side.