The Camino de Santiago as a Christian pilgrimage began in the 9th century, with the purported discovery of Santiago’s tomb in northwestern Spain. That discovery alone speaks of older pathways that would make it such an appealing place to bury a saint, and one of Jesus’s Twelve Apostles at that. Medieval pilgrims used the older roads forged by millions of feet before them, from prehistoric nomadic hunting and gathering peoples to Neolithic farmers and herders, from Celtic speakers to Romans. In this sense, the idea of the Camino as a 1,200-year old pilgrimage is really the path’s newest layer.

Though the Camino as we know it is defined by the medieval Christian pilgrimage, the territory in southwestern France and across northern Spain has been a significant corridor of nomadic migrations for as long as 1.2 million years.

Archaeologists call the whole territory from southwestern France across northern Spain the Franco-Cantabrian Region, because this terrain is unified by groups of prehistoric peoples who lived here in the Paleolithic era, when humans made stone tools and lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers. These early humans were drawn to this region by its rich sources of food, water, and shelter. It is no accident that one of Europe’s oldest native peoples, the Basques, live in the intersection of this ancient region.

Evidence of early human inhabitation has cropped up along the Camino, and several sites are open for the curious visitor to explore. In 2007-2008, archaeologists working at Atapuerca, 21 kilometers (13 miles) east of Burgos, discovered human remains that may date back as far as 1.2 million years, the oldest found anywhere in Europe.

In later prehistory (15,000-10,000 years ago), Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, followed by Neolithic early farmers and herders (7,000 years ago), forged paths across the rich territories of northern Spain. Some of those routes remain in use today, namely by herders who crisscross the Camino, moving their animals from summer to winter pastures as ancient Iberians have done for millennia. Your chances of encountering these sheepherders are good while walking the Camino across Navarra, La Rioja, Castile, León, and Galicia.

The whole northern territory of the Camino is also rich in dolmens (standing stones), which are associated with the early farmers of the Neolithic era. Most are around 5,000-4,000 years old. They are especially concentrated in Navarra, La Rioja, and Galicia. Some still stand near the medieval hilltop wine town of Laguardia, which is an easy day trip by bus from the Camino at Logroño.

Neolithic and later Bronze Age peoples (around 4,000 to 2,700 years ago) also created petroglyphs, stone surfaces engraved with dots, spirals, labyrinths, crosses, deer, and what seem to be solar or lunar markings. These appear in northern Spain, from Asturias to León and Galicia. In fact, in the city of Santiago de Compostela proper, one is preserved, the Castriño de Conxo, and you can visit it.

Celtic speakers were a diverse group of Atlantic coast-dwelling tribes from Ireland to Iberia that were interrelated through coastal seafaring, shared language, and trade. They were also an important part of Iberia, and left strong traces of their settlements, crafts, and cultures. It’s now thought that Celtic speakers may have first originated along the Atlantic (perhaps around 4,000 years ago), not in central Europe, and that their Atlantic culture made its way into interior Europe later (around 2,500 years ago), via the river mouths along the shore lines of France and Spain.

The oldest Celtic speakers may have come from either Ireland or Iberia. Remains of Iberia’s Celtic speakers are all along the Camino, some mingling so much with the earlier Iberians that their cultures are referred to as Celtiberian. Celtic speakers and Celtiberians built settlements known as castros (fortified hilltop villages and towns). These are especially present in the area near La Rioja, such as in Logroño, which has Celtiberian foundations; they become more concentrated across Castile into León and Galicia. Castro sites are most numerous in Galicia, right up to the Atlantic coast at Finisterre and Muxía. Castro de Castromaior, just a 200-meter (656-foot) detour off the Camino in Galicia, is beautifully intact and well worth a visit. Santiago de Compostela itself may be on an old castro site, which some archaeologists refer to as Castro de Susana, named after the Romanesque and Gothic church that is built on the neighboring hill to the hill of Santiago’s cathedral.

Neolithic and Bronze Age peoples, and especially the Celtic speakers, forged paths that connected their settlements to other significant sites, such as sacred places centered on water sources and mountaintops. (A few examples of these sacred natural places are the Ebro river that you cross upon entering Logroño; Monte Teleno, the mountain that dominates the horizon just after Astorga; and the Cruz de Ferro on Monte Irago, the highest mountain on the Camino, just after Foncebadón).

When the Romans infiltrated and gradually conquered Iberia, between 2,200 and 2,000 years ago, they made use of these prior routes to build their extensive road system for the transport of people and goods, such as silver, gold, tin, grains, and wine, across the empire. Romans also built major cities and extensive villas across the Peninsula, including important centers that you pass on the Camino—from Pamplona to Logroño, León, and Astorga. Even the Catedral de Santiago de Compostela stands on an old Roman burial hill. Large tracts of the medieval Camino also utilized Roman roads, most notably the well-preserved Roman road and bridge just after Cirauqui, where pilgrims will actually step over grooves left by the wheels of Roman carts.

With the decline of the Roman world, several Germanic tribes invaded Iberia in the early 400s, including the Alans, the Suevi, and the Visigoths. The latter eventually dominated and ruled Iberia (466-711) with divisive (and bigoted) polices toward the native populations, which made Iberia ripe for yet another invasion, one encouraged by the downtrodden locals.

In 711, Berbers and Arabs from North Africa invaded and over the next decades quickly dominated Iberia. Their Islamic policy of tolerance toward peoples of other faiths and backgrounds—especially Jews and Christians—helped assure their deeply rooted presence in the Peninsula for many centuries to follow. Many Visigoths and those of Roman-Hispanic descent were granted land immediately after the invasion, but some fled to the north, to the other side of the Cantabrian mountains, aspiring to set up their own kingdoms; this initiated the birth of the kingdoms of Asturias, then León and Galicia, Navarra, and Aragón. It also initiated the seeds of the idea of the Reconquista (Reconquest), which by the Middle Ages became a strong ideology of unifying the kingdoms toward a common cause to take back Iberia for themselves.

In the 700s, North Africans also pushed into France, making toward Poitiers (in 732) where Charles Martel, Charlemagne’s grandfather and head of the newly formed Frankish kingdom of the Carolingians, deflected the advance and sent the invading troops back over the Pyrenees. Here, indeed, is the root of Charlemagne’s ambition: he became king of the Franks in 768, and by 800 had unified almost all of western Europe (except Iberia) under his power, the first time a single power had controlled that vast territory since the fall of Rome. With the rise of a similarly imperialistic dynasty in Córdoba, in Islamic Iberia, Charlemagne aspired to take all of the Peninsula into his empire, too.

Pinched between Córdoba to the south and Charlemagne’s campaigns in the north, the tiny kingdoms of northern Iberia needed to come together. They never really did manage to do that, but soon, the legends of Saint James in Galicia arose, and with them, the Camino. This gave northern Iberians a unified identity, not to mention a road right along the path of the frontier lands dividing the Peninsula’s north and south.

Saint James the Greater (Santiago in Spanish), one of Jesus’s twelve disciples, was beheaded in the Holy Land in AD 44. Although no historical documents connect him to Spain, legends began to circulate after his death. It’s said that Saint James spent several years in Iberia evangelizing before returning to the Holy Land, where he was martyred. His two closest disciples then delivered his body in a stone boat guided by angels to Galicia, burying him on a hill at Santiago de Compostela.

In more legend, around the year 814, the hermit Pelayo followed a trail of stars to discover the tomb of Saint James. A chapel was soon constructed over the tomb, on the site of the modern Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Pelayo’s journey became the root of the pilgrimage as we know it today. King Alfonso II of Asturias made the first royal pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela sometime between 818 and 842, traveling a path through the Cantabrian mountains that’s now known as the Camino Primitivo. In 950, Le Puy en Velay’s bishop, Godescalc, made the first official pilgrimage from outside Iberia, beginning in south-central France, using old Roman roads, and crossing the Pyrenees to reach Santiago’s tomb.

At this time, the Caliphate of Córdoba, also known as al-Andalus, was still strong and unified; the northern Iberian kingdoms of Leon, Castile, Navarra, and Aragón were not. Under the leadership of Almanzor, troops from al-Andalus raided León and Zamora in 989, Carrión de los Condes and Astorga in 995, and Santiago de Compostela in 997. During the raid on Santiago de Compostela, Almanzor’s troops famously took the cathedral’s bells back to Córdoba, though Almanzor protected Santiago’s tomb from being disturbed in the fighting. Upon Almanzor’s death in 1002, the southern kingdom of Córdoba began to splinter into several city-states. The north, meanwhile, was becoming more unified and organized. This also was the era of El Cid, Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (1043-1099), the mercenary who served both the kingdoms of the Muslim south as well as the king of Castile, Alfonso VI (1040-1109). This also was the time when the Camino’s popularity began to rise.

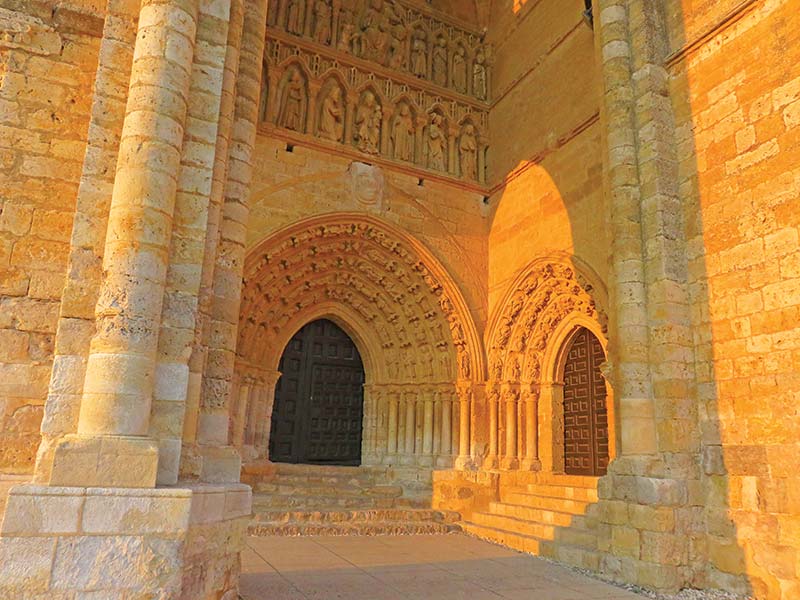

The Camino grew in popularity in the 11th and 12th centuries, becoming one of the most dynamic places in Europe and receiving explorers, adventurers, scholars, artists, artisans, and merchants from across the Continent, Africa, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Asia. This is also when the greatest development efforts of its medieval history took place. Among its apex developments was the building of the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela, along with many other commissions of beautiful and expressive Romanesque architecture and sculptures that capture, to this day, the rich religious and sacred traditions not only of European Christians but also of Iberian Jews, Muslims, and pagans. This is also when masons built the many pilgrim hospices, hospitals, roads, and bridges to give pilgrims safer passage (especially by the sainted engineers, Santo Domingo de la Calzada and San Juan de Ortega).

Curiously, in many ways the heyday of the Camino and of the northern kings could not have happened without the Muslim kingdoms of the south. As their power waned, they had to pay tribute to the northern kings, especially Fernando I of Castile (r.1037-1065) and his son, Alfonso VI (r. 1065-1109). These kings in turn gave an annual payment (largely gold from al-Andalus) to the powerful Benedictine order of Cluny in Burgundy. Cluny had begun as an order in the 10th century, but became a leader of western monasticism by the 11th and 12th centuries. Through Cluny and the commission of many Romanesque churches as well as monasteries, hospitals, and hospices, the Camino developed into a remarkable destination, and Europe’s greatest adventure for the devout, the penitent, and the rebellious. Other northern kings also aided in the development of the Camino, including Sancho III of Navarra (1000-1035) and Sancho Ramírez, who ruled Aragón from 1063-1094 and Navarra from 1076-1094. They encouraged French immigrants to settle along the Camino and build up its towns and commerce. (These settlers, and the influence from Cluny, combine to reflect the name of this most famous route of the Camino de Santiago: el Camino Francés, the French Way.)

During this era, many Franks and other northern Europeans arrived and settled along the Camino, as did Jews and Muslims, many of whom were farmers and craftspeople. The Muslim style of art and architecture forged in Christian Spain, referred to as Mudéjar for its distinctive Islamic geometric patterns and styles, is visible across the Camino, such as in a trio of churches in Sahagún. Christian builders from Islamic Spain also arrived to live on the Camino. They, too, had a distinctive style, known as Mozárabe, a mix of Islamic and Visigothic styles with a pinch of Roman, such as the church of San Miguel de Escalada near Mansilla de las Mulas and Santo Tomás de las Ollas in Ponferrada.

The Camino’s heyday centuries are also defined by the rise of many military-religious orders of knights who came to develop and protect the pilgrimage route and pilgrims. Among them were the Knights of the Order of Saint John (also known as the Hospitallers and the Knights of Malta), the Order of San Antón (who ran the Monasterio de San Antón, now elegant ruins on the way to Castrojeriz), the Order of Santiago, and the Order of Calatrava. But none is more famous or present across the Camino than the Knights Templar. Founded in 1118 by nine knights in Jerusalem living near the Temple Mound (hence the name, Templar), they took vows of celibacy, poverty, and service, especially to protect pilgrims to Christian holy sites. On the Camino they hold a special aura, not only as powerful knights but also as keepers of mystical Christian spiritual traditions that some modern pilgrims seek to uncover by walking the Camino. Signs of the Templar presence still survive all along the Camino, but Ponferrada stands out for its massive Templar castle that served as one of their key headquarters.

Through the 11th and 12th centuries, the south and north of Spain coexisted competitively but also harmoniously. However, by the 13th century, the kingdoms of the north had gained territory, control, and confidence. The last Muslim kingdom, of Granada, held ground by paying tribute to Castile’s kings from 1246-1492. In Christian territories, Iberia’s Jews began to experience rising attitudes of intolerance, which peaked in 1391 with horrific attacks across Castile against the Jewish communities. To protect themselves, many Jews either converted to Catholicism or moved to the safer Muslim kingdom of Granada. The north remained dangerous for anyone other than Christians, including pagans, Jews, Muslims, and, by the early 1500s (with Martin Luther’s reforms), Protestants.

The Catholic kings Isabel and Ferdinand in 1492 ended the Kingdom of Granada and absorbed it into Castile and Aragón and unified all of Spain into one Catholic nation, their original agenda and intent, no longer happy to just collect tribute. This unified Spain is the geographical shape of country we see today. Granada’s Jews were first forced to convert in 1492, as were Granada’s Muslims starting in 1499. Those who did not convert were expelled. These policies not only ended the rich cross-cultural flourishing that had built the Camino, they also contributed to the lessening popularity of the Camino itself. Pilgrimage had fallen out of fashion, as a rational world that valued the material over the spiritual took hold. Instead of pilgrimage, Spain (and Europe) was about to dive head-first into conquests abroad. Ironically, they took Santiago with them—not the peaceful pilgrim, but instead the sword-swinging warrior (popularly known as Santiago Matamoros) who was used as a symbol in the conquering of the non-Christian worlds of the Americas.

By the 15th and 16th centuries, pilgrimage to Compostela was already in decline. With fewer pilgrims walking, and fewer knightly orders to defend the route, the pilgrimage was a dangerous enterprise. Bandits and rogues traveled the Camino, preying on defenseless travelers. Protestant reforms outside of Spain further diminished interest in Catholic pilgrimage, which was seen as extravagant and superstitious.

depiction of Saint James as a pilgrim

Roman mosaics and villa ruins in Astorga

Romanesque sculpture of birds on Frómista’s Iglesia de San Martín

By the early 19th century, the trend in Spain was toward more liberal and secular government, and many, including landless farmers, saw the vast uncultivated lands held by monastic orders as a social and economic detriment. In 1835, the ruling minister of Spain banished the Jesuits. The next minister expelled most of the remaining religious orders, emptying nearly all the monasteries and convents. From 1835-1860, a good portion of Spain’s monasteries, including those along the Camino, were abandoned or fell into disrepair. Many were gutted and sacked, their art sold to collectors and their stones carted off for use in other construction. This, along with the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1809, explains why so many places have required massive restoration efforts in more recent years.

Since the late 19th century, other religious orders have come to Spain, occupied old monasteries, and worked not only to rebuild them but also to turn them into productive living centers of spiritual devotion, service, and communal enrichment. Many of the monasteries on the Camino today are occupied by these newer orders.

The history of Spain’s 19th century, and the first half of the 20th century, reads like a swinging pendulum of succession and control between liberal and conservative groups, until 1936, when the Franco regime plunged the country into a bloody civil war (1936-1939). Spain is still healing from this war and Franco’s dictatorship, and the Camino is one place among many where it cannot be pushed under the surface. In efforts to improve the trail, workers have inadvertently uncovered mass graves where people were executed and buried during the Civil War and the early Franco years. One is marked on the border of Navarra and La Rioja, right as you are entering Logroño, and another is found in the forest tract on your way from Villafranca Montes de Oca to San Juan de Ortega.

The Camino that we experience today can really be traced to the 1980s and 1990s, largely thanks to the efforts of O Cebreiro’s parish priest, Elias Valiño Sampedro, who from the 1960s to 1980s dedicated himself to retracing, mapping, and marking the path of the medieval Camino. It is he who is responsible for the beloved convention of painting bright yellow arrows as way-markers on the path. Sampedro also wrote the first modern Spanish guidebook to the Camino, The Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago, published in 1984 and translated into English in 1992. This, along with a 1989 French guidebook by Abbé George Bernès, Georges Veron, and Louis Laborde Balen, The Pilgrimage Route to Compostela in Search of Saint James, became the foundation for all other guidebooks that followed.

Pope John Paul II visited Santiago de Compostela twice, in 1982 and 1989; the Spanish built a memorial to commemorate his visit on Monte de Gozo hill, in 1993, to coincide with the Holy Year that year, when Santiago’s feast day, July 25, fell on a Sunday. Monte de Gozo is the last hill pilgrims pass before seeing the spires of Santiago’s cathedral for the first time. In 1987, the European Community named the Camino a European Cultural Itinerary. In 1993, UNESCO declared the road a Universal Patrimony of Humanity.

Since the mid-1990s, with surging numbers since 2007, the Camino has been achieving popularity similar to its heyday in the 11th and 12th centuries. Each year, 10,000 to 15,000 more people walk the Camino than walked it the year before:

• 1986: 2,491 pilgrims received a Compostela.

• 2005: 93,924 pilgrims received a Compostela.

• 2010: 272,135 pilgrims received a Compostela.

• 2018: More than 300,000 pilgrims received a Compostela.

The year 2010 was a holy year (when Santiago’s feast day, July 25, falls on a Sunday), which partly explains the surge in numbers that year. The release of the movie The Way, in November 2010, has since contributed to greater numbers of pilgrims on the Camino. But when you consider that these numbers don’t even include the many pilgrims (as many as 50 percent) who do not gather a certificate upon finishing, the numbers are impressive. Travelogues and movies in France, Spain, Japan, Brazil, Canada, the USA, and Germany, among other nations, continue to draw new pilgrims.

Camino trekkers are a diverse bunch. About 50 percent of pilgrims are from Spain (45 percent) and France (5 percent), the two most historic nations associated with the Camino, and the rest are from around the world. In recent years, over 140 other nationalities walked the Camino. The largest groups were from Italy (8 percent), Germany (8 percent), the USA (5 percent), Portugal (5 percent), Ireland (2 percent), the UK (2 percent), Korea (2 percent), and Australia (2 percent), followed by Brazil and Canada. Alongside the devout Christian pilgrims are Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, pagan, secular, agnostic, atheistic, and otherly-oriented pilgrims. About half the pilgrims are women and half are men.

Trekkers also come from all walks of life. Students walk it on their “gap year,” as do recent retirees as they figure out what lies ahead. Many pilgrims are professionals, self-employed or office nine-to-fivers, who see it as a way to clear one’s head while meeting people from all over the world. Wives/husbands and mothers/fathers walk it to reconnect with themselves and work out what to do after children have grown. Divorcees, widows, and widowers do so for healing, wholeness, and clarity. And the list goes on. Also, walking the Camino more than once is also becoming a trend as returning pilgrims use it as a reset button on their everyday lives, discovering it is more fresh and powerfully rejuvenating each time.

Many, but not all, people who decide to walk the Camino arrive calling themselves pilgrims. Even for those who don’t start out doing so, something curious happens once they start walking: Locals call them pèlerins (in France) and peregrinos (in Spain), and soon they embrace the term themselves, whether or not they are religious or spiritual journeyers. Especially because the title peregrino is directed toward walkers by locals deeply committed to service to the Camino, the term possesses an initiatory and transformative power that reveals the quest and adventure ahead, leading even secular travelers to start thinking of themselves as pilgrims in some way or another.