1

Symbol, the Casablanca Conference

From a worm’s eye viewpoint it was apparent that we were confronted by generations and generations of experience in committee work, in diplomacy, and in rationalizing points of view. They had us on the defensive practically all the time.

—Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, U.S. Army, February 1943

One cannot help suspecting that the U.S. Military Authorities who are now in complete control wish to gain an advance upon us, and feel that, having now benefitted from the fruits of our early endeavors, they will not suffer unduly by casting us aside.

—Message to Winston Churchill from Sir John Anderson, Tube Alloys director, January 20, 1943

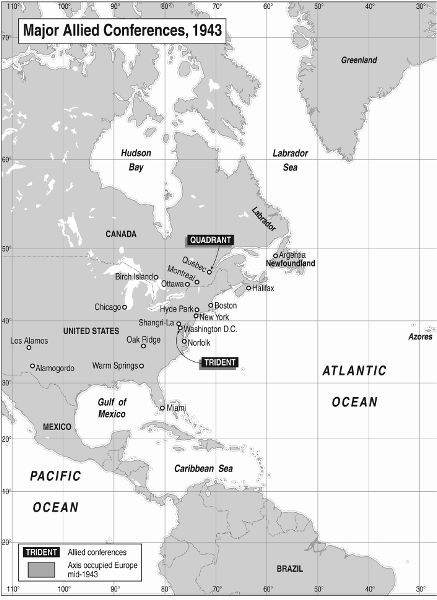

In November 1942, the Moroccan sky had reverberated from the shock waves of the bombs and naval guns of an invading Allied force. Now the January stillness was broken by throbbing bass quartets of heavy aero engines. From north and south, the top political and military leadership of the United Kingdom and the United States were converging on Casablanca to parley. Their ally, the Soviet Union, would not be represented because Joseph Stalin, although invited, claimed he needed to remain in Moscow to direct military operations.

Arriving first from the south in two four-engine C-54 transports on January 11, 1943, were the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) of the U.S. Navy, Army, and Army Air Force. They included Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall, Adm. Ernest King, commander of the Navy, and Lt. Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, Army Air Force commander.1 Traveling with the JCS to Casablanca was British Army Field Marshal Sir John Dill, head of the British military liaison in Washington. Dill’s perceptiveness, tact, and his friendship with Marshall would be crucial to the Anglo-American alliance at Casablanca and in the year ahead.2

Marshall had won Roosevelt’s respect when he alone openly disagreed with the president during a White House meeting five years earlier. Although he was told by others that his dissent had ended his career, Marshall was chosen by FDR in 1938 to be Army chief of staff. Admiral King had served throughout the Navy that he now led. During the First World War, King had spent time with the Royal Navy. Abrasive and authoritarian by nature, King came out of that experience as an Anglophobe as well. But because he was intelligent and insightful, King often would bring the British and American chiefs to the central point of their discussion. Arnold learned to fly from the Wright Brothers. He was an aviation pioneer and a firm advocate for air power. The American chiefs arrived fresh in crisp uniforms, but with limited staff and little preparation. This was a mistake.

Having arrived in Miami, Florida, secretly by train from Washington the previous night, Roosevelt took off aboard the Pan American Airlines flying boat Dixie Clipper for Casablanca on January 11 at 6:00 a.m. His party flew a three-day, mirror image J-shaped course via the Caribbean and Brazil to West Africa. At Bathurst on the Gambia River, January 13, they transferred to an Army Air Force C-54, nicknamed The Sacred Cow, for the onward flight to Casablanca.3

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a wealthy, sixth-generation patrician from New York’s Hudson River valley, unpretentious, and a Democrat. After serving as assistant secretary of the Navy he loved, he was stricken with polio. Roosevelt never gave in to this affliction. He was elected governor of New York in 1928 and president in 1932 in the depths of the Great Depression. In a time when there was concern for democracy’s viability against the challenges of Fascism and Communism, and when populist domestic demagogues preached division, FDR governed through optimistic pragmatism and appeals for unity. His New Deal eventually brought the country through the Depression, only to face a new world war. FDR came to Casablanca halfway into his unprecedented third term and with politics never far from his mind.

The flight to Casablanca made FDR the first U.S. president to fly and the first since Woodrow Wilson to depart the country while in office. In North Africa, he would become the first U.S. president to review troops in the field since Abraham Lincoln.4 The president brought with him his close adviser, Harry Hopkins, and selected White House staff. FDR’s chief of staff and chairman of the JCS, Adm. William Leahy, took sick en route and had to be left in Trinidad to recover.5

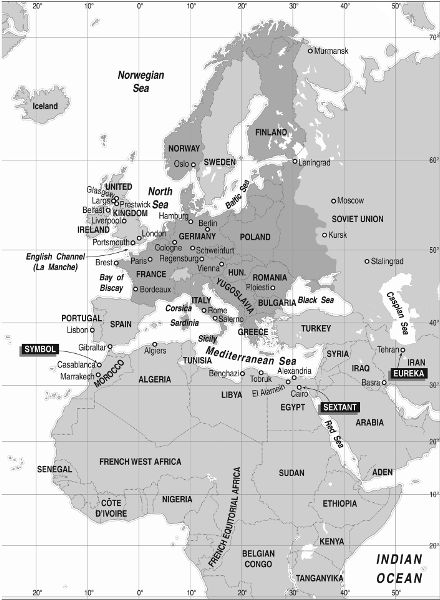

To Casablanca from the north on January 13 came four Royal Air Force B-24 bombers, converted into transports. Each flight had arced well out to the west over the Atlantic to avoid detection from German-occupied France or neutral but Axis-sympathizing Spain. Churchill’s B-24, Commando, carried the British prime minister, his immediate staff, and FDR’s emissary, Averill Harriman. Crowded onto the three following B-24s in “grim conditions” were the British military Chiefs of Staff (COS) and their support.6 Led by the chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), Gen. Sir Alan Brooke, were Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound, Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, Combined Operations commander Vice Adm. Lord Louis Mountbatten, and others.

More than three years of war had tested the British chiefs, men already hardened by combat in the First World War. Until recently, they had fought this war desperately short of resources and come back from defeat after defeat. Each had a worldview shaped by the experience of empire. Gen. Sir Alan Brooke was an exemplar strategist who seemed perpetually critical of those around him and personally unhappy. Professional in his public demeanor, Brooke was scathing in his personal diary. Under unrelenting pressure from the Germans, Pound had kept Britain’s maritime lifelines open. A fighter and bomber pilot in World War I, Portal had been a pioneer in the use of air power for imperial policing of tribal areas.7 That became part of the base of experience from which developed the interwar notion that an adversary population could be bombed into political submission. Mountbatten, who had risen quickly, had a reputation for dash to the point of recklessness that had been deepened by the disastrous August 1942 Dieppe raid. But from his experience of combined operations, Mountbatten brought a readiness to innovate to the prospect of an eventual return to the Continent.

By January 1943, Churchill already had led a full and influential life, rich in adventure. Becoming Britain’s prime minister at the country’s most desperate hour in May 1940, he rallied the British people with his eloquent determination while secretly beating back domestic advocates for capitulation. Serving as his own minister of defense, Churchill had a direct involvement in leading Britain’s war and day-to-day presence in its councils that could intimidate organized dissent, even when his chiefs disagreed with his ideas.8 He could drive his ministers and military chiefs to distraction, particularly Brooke, with his fire hose of “action this day” memoranda and fits of temper. But Churchill kept his subordinates informed of his actions and thinking while Roosevelt kept his cabinet and military chiefs guessing.

Difficult and cold, the British flights also brought the prospect of a subtropical respite from winter and London’s wartime privation. So, clad in a silk nightshirt, Churchill nearly froze on his flight.9 The COS arrived tired and disheveled.10 However, the British had been preceded by a large, well-prepared, and equipped support team that included an innovative floating headquarters ship, HMS Bulolo, which was a signal advantage.11

For the site of the conference, code-named Symbol, an Anglo-American team had selected Anfa, a Phoenician town five miles west of Casablanca with a view of the Atlantic Ocean. The airport, two miles away, could accommodate the heavy B-24s. Easily protected in the middle of a traffic circle with fourteen comfortable, even lavish villas nearby was the hilltop Anfa Hotel.12 With four stories and wrap-around balconies, the hotel featured Le Restaurant Panoramique in the center of a rooftop terrace. Rounded and painted white with the occupying Americans’ stars and stripes snapping in the breeze, the little art deco hotel resembled an excursion steamer putting out for a jaunt on the nearby ocean. Or was it a flagship for the villas? Commandeered together, they became “Anfa Camp” for the Symbol Conference.

Britain and the United States were convening in Casablanca to address the open question of global strategy for the coming year, particularly how best to reenter the European continent and defeat the Axis in the west. Commanded by Lt. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the successful November 1942 landing of a 107,000-man Anglo-American army in Morocco and Algeria put the Allies at the beginning of a new phase of the war. They were on the offensive. Foreseeable at the start of 1943, in the fresh knowledge of the cost to win, was the challenge ahead. Although the 1942 victories of Midway, El Alamein, and Stalingrad in its final phase were having greatly positive consequences, they were but an opening. These hard-fought battles had delivered the Allies out of a defensive war to the geographic threshold of taking the offense onto the Continent and in the Pacific against still-formidable enemies.

Should the Allies misstep, Germany conceivably could force a favorable outcome for itself in the form of a stalemate, possibly yielding an armistice. Distraction from the war in the Pacific risked allowing Japan the opportunity to entrench its forward position to the point of impregnability. If the British and American teams arriving in Casablanca needed a cautionary metaphor to balance the flush of recent victories, they had only to look to their successfully landed North African army’s current situation. Advance to the east was bogged down in Tunisia’s winter cold and mud.13

Soon after U.S. entry into the war in December 1941, the Americans and the British faced imminent threats of defeat both in Europe and the Pacific. They responded by agreeing at the Arcadia Conference in Washington to establish a critically important, ultimately successful body to command their worldwide fight. The British Chiefs of Staff, navy, army, and air force, and their American counterparts stood up as a Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) to prosecute the war globally from Washington. Their permanent representatives met daily in Washington, and the chiefs themselves met at Anglo-American summits. In Casablanca, over just ten days, the CCS would hold their fifty-fifth through sixty-ninth meetings.14

Creation of the facility for defining and directing collective action, however, was far from a guarantee of Anglo-American agreement on what was needed and how to achieve it. Although Churchill and Roosevelt quickly developed an affinity for each other, whether or not Churchill saw this quality in the president, each man remained firm in pursuit of his nation’s interests. Privately, Churchill was dismissive of FDR’s intellect and thought him malleable. The prime minister was to learn otherwise. The British and American military chiefs and their staffs came to their alliance with very different views of the world, their nation’s role in it, threats, and how to deal with them. The British and Americans were facing a harsh reality.

The bond of collective security forged in winning the First World War had been broken in intervening years by corrosive misperception, bias, and resentment. That could not now be reversed easily or quickly, even to meet shared existential threats. Perhaps this was inevitable between two cultures whose similarity could be as deceptive as their military traditions were different. Prevailing over the many Allied military disasters and near-disasters of 1942 had come at the cost of accelerated and intensified Anglo-American friction. Everyone gathering in Casablanca knew that the now urgent question drawing them together, offensive strategy had already been their frequent ground for conflict.

At the highest level, the United States and United Kingdom were in agreement that Germany was the most dangerous enemy. Japan could not win standing alone. But if the Allies were distracted to defeat Japan first, Germany—allowed time and latitude to stymy the Soviet Union and to consolidate the captured resources of occupied Europe—could become impregnable. Thus the Allied strategy of “Germany first” rested on a compelling but intellectual argument. For Americans, however, both among the public and tugging at the military leadership, particularly in the U.S. Navy, the emotional case favored strategic priority for retaliating against a Japan that had attacked first in the Pacific.

In the American public’s divided opinion on war priorities, Roosevelt and his Democratic Party perceived a nascent political threat. Republicans were seeking to build in 1944 on gains they had won in the off-year November 1942 congressional elections. An open question in 1943 was whether Roosevelt would seek reelection to the presidency in 1944 for a fourth term. Public adulation of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who had escaped the devastating defeat and capture of his American and Filipino troops, was seen as a potential Republican election opportunity. In 1942, through Michigan senator Arthur Vandenberg and Connecticut congresswoman Claire Booth Luce, Republicans had floated a “MacArthur for president in 1944” bubble in which MacArthur, commanding in the Southwest Pacific, was an innocent if somewhat interested party.15 Anticipating attractiveness to voters in the 1944 presidential contest, which might flow from altered public opinion, especially if FDR declined to run for a fourth term, the “draft MacArthur” advocates were preparing in 1943 to appeal again to voter emotions with a “Pacific first” political campaign strategy.

Not coincidentally, Madame Chiang Kai-shek was embarking on a barnstorm tour of the United States to build on the public’s demonstrated instinct to support China. Arriving in Casablanca with the sting of his party’s off-year election drubbing still fresh, FDR knew that Madame Chiang was to address both houses of the U.S. Congress in February, a month away.16

Among Roosevelt’s military chiefs, competition for resources often led the Army and Navy to divided positions on strategy. The European and Pacific theaters demanded generation of military forces and weapons in unprecedented quantities, even as response to the theaters’ differing geographies fueled interservice competition. The U.S. Navy’s leadership constantly pleaded for more resources for the Pacific where in fact the Army and Navy both struggled to fulfill bare minimal needs. The Navy tended to characterize allocations to the European theater as taking from the Pacific to the benefit of the Army in a zero-sum game. Given the shortage of steel and other materials, this often described the actual if not the intended result.

Although their motives might diverge, the U.S. Army and the Navy, nevertheless, could join in reaction to British initiatives that diverted the American buildup of forces in the British Isles away from the quick-thrust strategy of cross-Channel attack the JCS wanted. Pressed to their limit, the JCS’s response was to play the Pacific card. In July 1942, they had recommended to Roosevelt that if cross-Channel attack was not to be the Allies’ strategy, then the United States should shift attention and resources away from Europe and toward a “Pacific first” strategy, only to be rebuffed by FDR.17 Nevertheless, in CCS meetings, the Americans would warn the British of this U.S. contingency option. They would do so again at Casablanca.

Roosevelt, his Republican Secretary of War Henry Stimson, and Harry Hopkins took in a larger picture and generally sought balance between the two opposing views. They tended to the more measured view that the British had not been wrong in 1942 to resist a cross-Channel attack as premature. Resolute in their determination that Hitler must be defeated first, they also were concerned about leaning too far in favor of further British proposals for operations in the Mediterranean and the Balkans. Doing so would risk a public perception of the prospect for a longer war for objectives peripheral to U.S. interests, specifically objectives of the British Empire. Secondary to Roosevelt and Hopkins’s objective goals for the war, but not excluded from their considerations was that this could redound to the advantage of domestic political opponents who would not put Europe first.

The U.S. military chiefs went into World War II with a sequential strategy for fighting the global conflict, based on the goal of winning a short war. First, defeat Germany in Europe as the most dangerous threat,18 shift to the Pacific to defeat Japan, and then come home. Before 1943 ended, the third objective, coming home, would be deferred indefinitely by a transformational change in perception of the role of the United States in the world.

The way to achieve the first objective and facilitate the second, in the view of the U.S. chiefs, was a violent, overwhelming thrust across the English Channel, through northwestern Europe, into the German citadel. Planners for this objective in early 1942, then overseen by recently promoted Brig. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, conceived Operation Roundup to be a massive offensive by forty-eight divisions, thirty U.S. and eighteen British, supported by 5,800 aircraft. Roundup’s U.S. planners optimistically foresaw such a force being assembled in the United Kingdom by April 1, 1943. With the Soviet Union then waging a desperate, as yet uncertain, defense against invading Axis armies, the United States also envisioned a much smaller emergency invasion to take pressure off the Soviets in the event of their imminent collapse. This contingency operation, named Sledgehammer, called for a cross-Channel assault with whatever forces were available in the UK. The objective was to draw some German divisions out of Russia with the threat of an Allied lodgment in the west. The U.S. planners anticipated shipping available to sustain just five divisions supported by 700 aircraft for Sledgehammer by September and October 1942.19 Sustainment was not the same thing as an opposed landing of a force of this size on the Continent. For that, the needed amphibious lift did not then exist.

The U.S. plans and estimates were wildly optimistic from their inception. To advocate for them, U.S. Army chief of staff Marshall and Navy commander in chief Ernest King,20 accompanied by Harry Hopkins representing FDR, had gone to London in April 1942. The JCS opposed the idea of an amphibious invasion of North Africa, Gymnast, as a diversion of resources. They were keeping on the table the U.S. option to switch their priority to the Pacific.

The British chiefs and Churchill initially expressed to Marshall and King assent, mild but disingenuous, for the cross-Channel attack strategy, even though the majority of forces for Sledgehammer would be British. They believed that neither the United States nor Britain would have the means to mount and complete either cross-Channel operation in 1942–43, unless Germany were suddenly to collapse from within as it had in 1918. That contingency, which the Americans acknowledged, the British were seeking to induce through aerial bombing and maritime blockade. The British chiefs’ own strategy of peripheral attack, principally around the Mediterranean while attempting to weaken Germany, was then in gestation. Learning through Harry Hopkins that FDR’s goal was to get U.S. troops into the fight in Europe before the end of 1942 “in the most useful place, and in the place where they could attain superiority,”21 Churchill and the British chiefs saw their out. Hopkins’s candor had determined for them that the president was less fixed on the point of initial engagement in Europe than his military chiefs were.

Marshall, King, and Hopkins returned to London in July 1942 with more specific instructions from their commander in chief. These FDR had developed in consultation with Hopkins. This time, Churchill learned from Hopkins that Roosevelt had taken first priority for the Pacific off the table and that getting U.S. forces into combat in the European theater in 1942 was the president’s priority. So Churchill knew that he could resist Marshall’s cross-Channel strategy for 1942–43 and advance his own Mediterranean strategy without risk. He did so.22

In London in July, Marshall, King, and the newly established American command staff with help from Lord Mountbatten’s Combined Operations Command labored to produce a better plan for Sledgehammer as a precursor for Roundup. They offered their result in vain. FDR’s directive and Churchill’s informed resistance left no alternative to an invasion of North Africa as the next operation. Over the months that followed, the American chiefs fiercely argued for their preference. In the end, they had to accept resurrection of the renamed plan for an Anglo-American invasion of North Africa, Operation Torch, which was carried out in November 1942.

With their own European strategy kicked into the indeterminate future, the U.S. chiefs arrived in Casablanca in January 1943 with little confidence in Roosevelt’s ability to resist Churchill and with hard feelings toward their British counterparts. They feared that the North African landings they had been forced to accept were but the first step along an endless path into the Mediterranean. There were plenty of doubts and suspicions about capabilities and motives on both sides.

Among the U.S. military staff still could be found adherents to the view of America’s isolationists that the United States had been duped into World War I by the British. There was lingering suspicion, influencing staff papers signed off by U.S. service chiefs, that the British put priority on preserving their empire in context with a favorable postwar European balance of power. They could lapse into thinking that this goal drove the British position on strategy as much as their desire to defeat the Axis.23 The JCS and their lieutenants’ admiration for Britain’s firm stand alone against Hitler’s onslaught in 1940–41 was mixed with their sense that recurring defeats had eroded their British counterparts’ aggressiveness.

Members of the British Chiefs of Staff perceived the United States to be lacking in military leadership capability to match its potential in manpower and materiel. That was not an unreasonable conclusion to draw from early U.S. overreach to advocate for a cross-Channel invasion that the British considered naïve and from initial stumbles by the U.S. military in the dark year of 1942. The British were acutely sensitive to the fact that General Marshall specifically had no experience leading armies in combat.24

Self-doubt and friction also dogged internal relations between each country’s military and political leadership. Winston Churchill’s micromanagement, flashes of ill temper, and stream of “action this day” directives exasperated the British COS and affected their personal opinions of his leadership ability.25 For his part, having struggled to generate requested troops and resources only to endure British defeat after defeat in battle, Churchill apparently had come to suspect the capability of his military chiefs.26

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff felt that FDR could not be relied on to stand up for U.S. goals and strategy against Churchill’s persuasiveness. The chiefs had felt undercut by Roosevelt’s shift from support for a cross-Channel invasion to instead redeploy forces for the invasion of North Africa that both FDR and Churchill desired. While outwardly supporting General Marshall’s advocacy in London for a cross-Channel attack, Roosevelt’s key aide, Harry Hopkins, had privately signaled more flexibility to Churchill.27

Marshall was astute enough to understand how the JCS had been maneuvered into accepting Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. But the military’s reliance and confidence in Harry Hopkins endured out of necessity. Beyond their unanimous appreciation for Hopkins’s personal commitment to winning the war, the JCS knew this former social worker of frail constitution had an unequaled ability to draw decisions from the evasive Roosevelt. Marshall and Hopkins also had in common the bond between fathers whose sons were on active duty. Each would come to grieve the death of a son in combat.28

*

Winston Churchill brought with him to Casablanca from London a brand-new problem, one entirely different from military strategy and closely held. Britain’s participation in the super secret Anglo-American work to develop an atomic bomb and access to information on its new discoveries in physics had been curtailed by the Americans. First together in the same theater at Casablanca, but standing well apart, the two issues, European war strategy and the ostensibly joint quest for an atomic bomb, would move onto the same stage and ever closer in proximity as 1943 progressed.

In October 1941, President Roosevelt had proposed that the two nations’ efforts on weaponizing atomic energy should be “coordinated and even jointly conducted.”29 Believing they were ahead of the Americans on the science, the British at first had demurred. Then the British changed their minds after further considering the vast intellectual and financial resources required, access to natural resources, and the relative safety from military threat gained by basing the project in North America.

Since an informal oral agreement reached during a meeting between FDR and Churchill at the president’s Hyde Park, New York, estate in July 1942, Britain and the United States had been moving toward a coordinated effort to speed research and produce an atomic bomb.30 The Anglo-American scientific community’s knowledge of discoveries by German scientists, combined with intelligence reports, persuaded them that they were in an all-out race to beat the Third Reich to the bomb. The British established an advance team of scientists in Montreal anticipating closer involvement with the Americans. But, only six months later, the U.S. side of the project put the British on notice that exchange of information on atomic weapons research would be sharply limited.31

On the day of departure for Casablanca, January 11, Churchill received a letter from Sir John Anderson, the lord president of the Privy Council, written with the concurrence of Lord Cherwell, the paymaster general and Churchill’s scientific adviser. Anderson and Cherwell were the prime minister’s principal advisers on atomic matters. The letter notified Churchill of the new restrictive U.S. policy on cooperative atomic bomb information interchange, the project that the British code named “Tube Alloys” and their American counterparts called “S-1.”32 For the British, the new U.S. restrictions plunged the project into crisis.

Writing for both men, Anderson said, “This development has come as a bombshell, and is quite intolerable.” Anderson and Cherwell recommended “that an approach to President Roosevelt is urgently necessary.” On the attached extract from the U.S. memorandum detailing the specifics of what was to be withheld, Churchill circled in red two references to “element forty-nine,” code for plutonium by then identified as the most potent fissile material for a bomb. At the top of the first page, he wrote and circled a single word, Symbol, the code name for the conference with Roosevelt in Casablanca to which Churchill would fly that night.33

Weaponizing the energy of the atom, a possibility to which British science had contributed so much important early research, was foreseen by Churchill to become a fundamental determinant of political-military power in the postwar world. That world was likely to be dominated by the United States and the Soviet Union. In January 1943, awareness of the postwar importance to Britain of having its own bomb was dawning apace with unfolding realization that the decision to shift atomic research to North America for sound reasons had an unintended consequence. Achieving an independent British atomic weapon capability had become dependent on a nation that for its own reasons might not accommodate British interests.

Beyond an Anglo-American race to acquire an atomic bomb before Hitler, Churchill understood that this also was a unilaterally British issue for the future that demanded attention in the present. Could Anglo-American pursuit of an atomic bomb continue as a joint endeavor toward a result equally available to both countries?

The overt reason for the new U.S. policy, as explained to the British, was based on a security principle. The British suspected, however, that there was a deeper reason not stated to them.

Oversight for atomic research and its product on the U.S. side was through the Military Policy Committee, involving Vice President Henry Wallace, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, George Marshal, Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) director Vannevar Bush, and Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves. Since September 1942, Groves had command of the Manhattan Project, created to produce an atomic bomb from the scientists’ research. Leading implementation of the project for the United States was a civilian-military management team: Bush, his OSRD deputy director, James Conant, and Brig. Gen. Groves. Physicist Robert Oppenheimer led the scientific team.

Dr. Conant was a chemist and president of Harvard University. Dr. Bush had come from directorship of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Electrical Engineering Department to become president of the Carnegie Institution. Then, as the first presidential science adviser, he became director of OSRD. That organization had vast influence on science’s contribution to the U.S. war effort.

By late 1942, strongly encouraged by Groves, Bush and Conant had concluded that the United States was making 90 percent of the effort and providing 90 percent of the investment to develop and build a bomb for this war, while Britain’s level of effort could not yield a bomb in time for the current war. Bush and Conant would come to the position that sharing knowledge of how to produce such a weapon with a foreign nation was neither in the U.S. national security interest nor within the scope of FDR’s war powers. In their later correspondence, they can be seen to be jointly concerned that sharing knowledge of the bomb could not be done without an alliance that would constrain U.S. latitude to act in its own national security interest. Churchill’s end goal, not openly put to the Americans until September 1944, in fact was an alliance that would continue after the current war.34

The three men chose to employ a narrower rationale to meet their concern. They convinced the Military Policy Committee that in the context of FDR’s legal authority to wage the current war, information shared with the British and the British-sponsored team in Canada should be based strictly on the principle of “need to know.” The British should receive all the information that would help advance the areas of their participation contributing to the project for this war, but were not entitled to any other information. The three men expressed their decision as a straightforward extension of the principle of need to know that was in effect throughout the U.S. war effort. Bush and Conant believed that their action was consistent with what the president wanted: an impression that FDR fostered with his December 28, 1942, acceptance of all the Military Policy Committee recommendations and later did nothing to discourage.35

Dr. Conant informally described the imminent U.S. policy change to the British representative to the project in Washington, Wallace Akers, on December 11, 1942. Following the Military Policy Committee’s decision, Conant outlined the new policy in a letter that he wrote with Bush’s knowledge and sent to the British on January 2, 1943, via the Anglo-Canadian team working on the project in Montreal. Conant then wrote on January 7 a more extensive memorandum that detailed how the new policy would be applied to specific elements of the project, the details of which became known to Akers.36

Wallace Akers was a principal engineer at Imperial Chemical Industries, on loan to the government to help lead British atomic research. The Americans, Bush, Conant, and particularly Groves, were opposed to Akers as the British representative on the grounds that an ICI executive would gain for his company and country a postwar global competitive advantage in atomic power generation.37 Possibly they actually saw more than their match in the cultured and thoughtful Akers’s effectiveness in representing British interests through his hard work and perceptiveness.38

Even without the assumed conflict of interest and interpersonal tension, a rupture in cooperation would have been impossible to avoid. The new American policy’s negative impact on British interests spawned an Anglo-American standoff in Washington that immediately became a crisis in London.

The British were quick to see that restricting their participation on a “need to know” basis would result in an essentially one-way flow of information to the benefit of the United States and to the detriment of essential aspects of their own atomic research. Although not expressed by them in these words, the British position was that the corollary to “need to know” was their U.S. ally’s obligation to share. From an impression that the OSRD civilians, Bush and Conant, found General Groves intimidating, the British almost immediately began to suspect a deeper motive beyond the stated concern for security. They believed that the U.S. military desired to take exclusive control of atomic research.39

So it was that Winston Churchill arrived in Casablanca, where his military chiefs would engage in certain-to-be-fraught military strategy discussions, with the rupture of Anglo-American atomic information interchange very much on his mind. At the outset of 1943, the British COS themselves had little if any knowledge of the importance or even the existence of the Tube Alloys project. Neither were they aware of the newly contentious issue’s presence at Casablanca.40

Within two hours of their 13 January arrival, tired though they were, the British COS met with Field Marshal Sir John Dill, who briefed them on the Americans’ general military strategy position and relations among the American chiefs. This was time well spent. The British chiefs were forewarned by Dill that their American counterparts for multiple reasons strongly opposed following up the recent landings in North Africa, Operation Torch, with new initiatives in the Mediterranean. The Americans thought it would reduce the likelihood of a major cross-Channel assault into France. According to Dill, they also thought Mediterranean operations would draw resources away from the bombing of Germany and expend scarce naval craft and merchant shipping for less than optimal returns. A diversion to the Mediterranean would retard operations in Burma [Myanmar], which the Americans thought were significant to keeping China in the war, Dill said. The American chiefs, in Dill’s assessment, questioned the strength of the British commitment to the war in East Asia. In pressing for a rapid defeat of Hitler, the Americans believed that if given time to dig in by a drawn-out European campaign, Japan would become impossible to defeat. Dill also told the British chiefs of friction between the U.S. Army under Marshall and the Navy under King.41 The informative meeting with Dill concluded, British COS next met with Churchill at 6:00 p.m. and briefed him on their position going into the negotiation with the Americans. General Brooke then met with General Marshall for dinner followed by “a long talk.”42

*

President Roosevelt arrived in Casablanca late on the afternoon of January 14. He was taken to the villa set aside for him in Anfa Camp, whereupon Harry Hopkins immediately fetched Churchill from his villa for drinks. The president then summoned the British and American chiefs to join the two leaders for a convivial dinner that lasted late into the night.43 When the lights were extinguished for an air raid warning that turned out to be false, the evening ended with the faces of the assembled illuminated by candlelight.44

The following morning, Marshall, King, and Arnold met with FDR, Hopkins, and Harriman for the last time before the JCS sat down with the British. Marshall led the briefing of the president, speaking with the benefit of his talk with General Brooke the evening before.45 Marshall quite accurately told FDR that the British chiefs’ strategic concept for Europe called for first expanding bombing of the Axis and that they favored expanded Mediterranean operations as the best means to force Germany to disperse air resources. Marshall told FDR that the British favored Sicily over Sardinia for the next Allied operation. In Marshall’s observation, the British were “extremely fearful of any direct action against the Continent until a decided crack in the German efficiency and morale has become apparent.” Marshall told FDR that any operation in the Mediterranean “will definitely retard Bolero,” the transatlantic buildup of U.S. forces in the British Isles for a cross-Channel attack into France. Marshall found the British and U.S. chiefs to be in agreement on giving priority to defeating the U-boats.46

That afternoon, curtains were drawn across the Anfa Hotel’s broad windows. The Combined Chiefs of Staff sat down to their first substantive meeting. It started out well enough.

General agreement came quickly on the first topic, fulfilling antisubmarine warfare (ASW) requirements. For that the CCS had good reason. Everything the Allies were doing and hoped to do depended on shipping. Before the onset of winter storms in the North Atlantic brought partial relief to the convoys, November 1942 had seen the U-boat wolf pack predations at their worst. Sinking of Allied and neutral shipping set a new monthly record at 636,907 tons.47 The U-boat threat had to be countered by spring, whatever the Allies’ strategy choice for Europe.

Everywhere, the Allies always were short of surface escorts to protect the convoys. Only the introduction of operationally ready, new construction escort vessels could provide relief. Also agreed by the chiefs was that patrolling aircraft were highly effective in suppressing the U-boats. However, ASW patrolling required a lot of aircraft and flying time. The absolute “minimum requirement for Atlantic basin and UK home waters was 120 to 135 long-range bombers,” according to Admiral Pound.48 With this language, the note takers glossed over internal interservice contentions under way in both London and Washington on the allocation of bombers.

The most critical need was not for long-range but for very long-range (VLR) bombers to close a mid-Atlantic Ocean gap in air coverage where U-boats still enjoyed too much freedom to hunt. Competition was sharp between bombing advocates and ASW commanders for the still too few VLR candidate aircraft. Agreeing to the need, but kicking distribution into the future, the CCS directed the Combined Staff planners to assess and report the minimum requirements for escorts, aircraft carriers, and land-based aircraft to secure the United Nations’ sea communications everywhere during 1943.49

Lt. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander in North Africa, entered the room after a rough, trouble-plagued flight from his headquarters in Algiers. He briefed the CCS on the current situation in North Africa and followed up with a briefing on his proposed attack with U.S. forces on the Axis-held Tunisian town of Sfax. Eisenhower’s plan was sharply criticized by General Brooke for its lack of coordination with the British First and Eighth Armies, neither of which would be in a position to support the attack. As a result, Brooke said, the proposed U.S. attack risked being defeated in detail by Gen. Erwin Rommel’s German forces.50

Criticism of Eisenhower’s plan could not help but stir British perceptions of inexperience and inadequacy in U.S. generalship. That was an inauspicious lead into what followed. The Combined Chiefs of Staff next turned to strategy for the European theater, so beginning three days of deadlock.

Gen. Sir Alan Brooke led off. He first set up the options for a cross-Channel attack into northwestern Europe and then described in some detail the slim advantages such an attack offered. Not for the first time, the negatives associated with a cross-Channel attack were easily cited and difficult to counter in the absence of rigorous Allied planning for this strategy option. Brooke, with the benefit of planning for the British alternative, then described a Mediterranean strategy that offered many options with good potential and cascading advantages. A great benefit in Brooke’s view was that focus on the Mediterranean, by limiting a buildup of tactical air units, would allow a greater heavy bomber force to be built up in the United Kingdom than if the Allies concentrated on invading France.51 Thus, in a larger sense, the emerging Mediterranean strategy supported the British preference for defeating Germany through attrition and would diminish materiel resources for the American-preferred alternative.52

The British chiefs, deft in their serial coordination, countered successive, weak U.S. criticisms of the British position and an uncoordinated defense by the American chiefs of their own bid for greater priority and resources for the Pacific theater.53 The British then moved the discussion on to the advantages of following up anticipated success in North Africa by next attacking Sicily not Sardinia.54

From this meeting, the CCS reconvened at 5:30 p.m. for the first of three plenary sessions with FDR and Churchill. There Roosevelt made statements that favored Mediterranean operations.55 This indicated to the British that, once again, a division on strategy existed between the president and his JCS as it did among the CCS themselves. That was their opening to isolate General Marshall and his desire for a cross-Channel attack, as had been done in 1942 when the decision was made in favor of the North African landings.

In London, meanwhile, the anxiety of Britain’s Tube Alloy scientific leadership ratcheted up. That evening they received from the British Scientific Mission in Washington Wallace Akers’s transmission of the text of the Conant memorandum detailing seven specific areas in which information exchange would be withheld or limited.56 As yet, Anderson and Lord Cherwell had received no response from Churchill in Casablanca.

On January 16 the CCS met twice more on the issues of strategy. Their discussion went along much the same lines as the day before. General Brooke wrote in his diary that this was a slow and tiring process. The slog was fueled by Brooke’s growing disdain for the American chiefs, particularly what he saw as the absence of a sense of strategy among Marshall’s “very high qualities.”57

General Brooke possibly was reacting to Marshall’s challenge to the British chiefs in this day’s CCS meetings to articulate their best plan for defeating Germany. In so doing, Marshall, by his use of argument alone, clearly was trying to compensate for the absence from the conference of a prepared U.S. staff comparable to that of the British. Given that the British had cited aid to the Red Army as a key to victory, Marshall insisted that logic compelled them to invade the Continent. Thus in the meeting, Marshall attempted to set a strategy of direct action against the strategy of attrition. Still, he was ready to take an additional step with the British into the Mediterranean, to Sicily, if doing so would be the last step before committing the Allies to giving priority to the cross-Channel attack-based strategy. To Marshall, direct attack across the Channel and then on into Germany itself was “the main plot” of the war in Europe.58

At 5:00 p.m., the British and U.S. chiefs parted to report and consult separately with their leaders. General Marshall conveyed to FDR the importance to the British of obtaining a crack in German morale as a prerequisite for a return to the Continent.59

“A desperate day!” was how Brooke began his diary account of how, on the following day, Sunday, January 17, the CCS wrangled again over strategy. The chief of the Imperial General Staff concluded that in his opinion, the Combined Chiefs were “further from obtaining agreement than we ever were!” Admiral King and General Marshall had been emphatic on the need to maintain pressure on Japan. Warning that the immense cost in resources to engage the Japanese affected every other United Nations operation worldwide, Marshall ominously warned that “a situation might arise in the Pacific at any time that would necessitate the United States regretfully withdrawing from commitments in the European Theater.” Hearing the Americans’ advocacy for the Pacific, particularly Marshall’s stark warning, the British chiefs concluded that the bedrock principle of defeating Germany first was back on the table. They directed their staff to prepare a new paper with which to confront this issue on the following day.60

The CCS resumed meetings on January 18. For the strategy debate at this conference, the day would be decisive. They began by discussing a contemplated amphibious landing, Operation Anakim, to retake Burma, then a Japanese-occupied British colony, as a step to keep China in the war. Around Anakim and the larger question of the allocation of effort to the Pacific again swirled the fundamental question. Was the Anglo-American commitment to the concept of defeating Germany first still firmly shared?61

The British attempted compromise by offering agreement with the U.S. Pacific strategy but, referring to the new British COS paper, “provided always that its application does not prejudice the earliest possible defeat of Germany.” That drew a response from Admiral King that the British statement could be read to mean that “anything which was done in the Pacific interfered with the earliest possible defeat of Germany and that the Pacific theater should therefore remain totally inactive” (italics in the CCS meeting minutes). Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal attempted to counter King’s objection by citing the immediate opportunity for engaging Germany in the Mediterranean and increasing bombing of Germany directly out of the United Kingdom, thereby assisting the Russians. But Portal helped nothing when he admitted that it was impossible to say exactly where the Allies should stop in the Mediterranean. The chiefs’ argument went on at length, finally turning to other subjects with nothing resolved.62

Gen. Sir Alan Brooke left the morning meeting despairing to Field Marshal Sir John Dill, “It is no use, we shall never get agreement with them!” Dill, who in 1941 had been eased out and replaced as CIGS by Brooke, told the younger man that most points already were agreed between the two allies. After lunch, the two met in Brooke’s hotel room where Dill ticked off the remaining points of disagreement and asked how far Brooke would go to get agreement. When Brooke replied that he would not move an inch, Dill replied, “Oh, yes, you will. You know that you must come to some agreement with the Americans and that you cannot bring the unsolved problem up to the Prime Minister and the President. You know as well as I do what a mess they will make of it.”63

Air Marshall Portal came into the room with a similar proposed plan for agreement. The paper Portal carried had been written by his assistant chief of staff, Air Vice Marshal Sir John Slessor, over lunch at the hotel’s rooftop restaurant. With consensus among the three British officers, Dill left to discuss their proposal with his friend Marshall.64 When the CCS reconvened at 3:00 p.m., Brooke presented the compromise paper, which was accepted with few changes. The chiefs then briefed Churchill and Roosevelt, who gave the plan their approval, after which everyone was photographed together.65 The smiles were tight.

Over the next three days, the CCS moved toward a concluding conference document with actionable objectives. They agreed that “the defeat of the U-boat must remain a first charge on the resources of the United Nations.” Also agreed was that Soviet forces must be sustained by the greatest volume of supplies possible that could be transported to Russia without prohibitive cost in shipping. Operations in the European theater would seek to defeat Germany in 1943 with the maximum forces that can be brought to bear. In the Mediterranean, this would mean the occupation of Sicily and seeking to enlist Turkey in the war. From the United Kingdom, this would mean “the heaviest possible bomber offensive against the German war effort” (from Air Vice Marshal Slessor’s paper), limited amphibious raids as may be practicable, and “assembly of the strongest possible force . . . in constant readiness to reenter the Continent as soon as German resistance is weakened to the required extent.”66

The last objective was qualified to be limited by the needs of the Mediterranean and operations in the Pacific and East Asia to the narrow extent that those had been approved. The much discussed recapture of Burma (Anakim) was approved subject to all of the other calls on time and resources. Operations against the Marshall and Caroline Islands, after the recapture of Rabaul, were approved if not prejudicial to Anakim.67

Self-evident in the concluding CCS document of priorities for 1943 were many provisos subject to future interpretation. Between its lines was the British belief, a hope at this stage shared by Roosevelt, that Hitler’s Reich could be induced to implode by forcing a collapse of German morale.

The contentious issue of European theater war strategy had been consigned to an uneasy agreement with the expectation of another major conference in the spring of 1943. The Combined Chiefs used their remaining days in Anfa Camp to address issues that, although of a lower order, would have a decisive effect on prosecution of the war in Europe.

The chiefs took up better coordination of the bombing of occupied Europe and Germany. At Casablanca, the U.S. Army Air Force and the Royal Air Force leadership were allies in the advocacy of air power, while disagreeing on how to use their respective long-range bombers. The RAF’s campaign, ever increasing through 1942, was based on night area bombing of German cities. The still-small but soon to grow USAAF operations were founded on a belief in the effectiveness of daylight precision bombing of defined military-industrial point targets. Bombing results, or their lack to date, was a source of criticism for both operations. The RAF and USAAF banded together at Casablanca and won endorsement for integrating their different operations as a day-and-night Combined Bomber Offensive.

At their sixty-fifth meeting on January 21, the Combined Chiefs approved a governing “directive” to the RAF and USAAF operational commanders with the objective of “the progressive dislocation of the German military, industrial, and economic systems, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.”68 How the Combined Bomber Offensive was implemented would become important to opposition to the cross-Channel attack-based strategy and also, through a collateral effect on the Luftwaffe still to unfold, the success of that very strategy.69

On January 22, the Combined Chiefs took a significant if less noticed decision to discern the viability and substance of cross-Channel attack. They agreed to establish in London an Allied team to plan for a return to the Continent. Previous separate and thinly resourced planning efforts would be replaced with an integrated, stand-alone organization of British and American composition. General Brooke said that a special staff for cross-Channel operations should be set up without delay. Among the structures recommended by General Marshall was that the head of the team should be designated the chief of staff to the still-to-be-named Supreme Allied Commander.70

In what must have been a bitter pill for the American delegation to Casablanca, the proposal to form the new unit took as a given that “there is no chance of our being able to stage a large scale invasion of the Continent against unbroken opposition during 1943.” The proposal then described activities for which planning was needed including small-scale amphibious operations, such as reoccupation of the British Channel Islands, and readiness for a pick-up invasion to exploit “a sudden and unexpected collapse of German resistance.” The example planning activities led lastly to planning for an invasion in force in 1944.71 Beyond setting the year 1944, specifics as to timing and the means for implementing these plans were left to be determined.

The CCS did recognize the need and committed to providing the new planning unit with a “clear directive . . . setting out the objects of the plans and the resources likely to be available.”72 Although the details were uncertain, the mandate to begin genuinely allied planning to liberate the Continent now was a fact. Whether a cross-Channel attack-based strategy could succeed was an open question.

*

As the Combined Chiefs argued toward a military strategy compromise, essentially limited in scope to 1943.73 Winston Churchill took up the separate crisis over a break in Anglo-American atomic information interchange. Acting on Sir John Anderson’s January 11 letter of deep concern, Churchill made an approach to the Americans. Instead of appealing the new restrictive policy directly to Roosevelt, the prime minister elected to take the issue to FDR’s close adviser, Harry Hopkins.74 Churchill had developed a liking for Hopkins and placed deep trust in him. For that he had good reason. Hopkins was to Churchill a frequent source of intimate, often decisive insight into the thinking of the ever-smiling but often inscrutable Roosevelt.

The details of this exchange between the prime minister and Hopkins have not survived. However, Churchill found Hopkins’s response on Tube Alloys information interchange satisfactory. From Casablanca on January 18, Churchill’s assistant secretary sent a message to Sir John Anderson in London. The message said that the prime minister “spoke to Mr. Harry Hopkins about this matter and was assured that the President, while he did not wish to telegraph about it, knew exactly how it should be handled, and it would be entirely in accordance with our wishes.”75

By January 19, the crisis in London had reached the boiling point. That day, possibly unaware or not privy to the message about Churchill’s initiative in Casablanca, British Tube Alloy scientists and program managers began to discuss responding to the new U.S. policy by withholding British information.76 By the following day, Anderson and Lord Cherwell were discussing the scientists’ restrictive response. In a “Note for the Record,” William Gorell Barnes wrote that, on January 20, Anderson and Cherwell “decided that, for the time being, we should continue to give the impression of not withholding information from the Americans regarding our progress on Tube Alloys, but, at the same time, should be careful not to give away any important secrets until the position has clarified.”77

That may have mollified the scientists, but the anxiety of the Tube Alloy leadership in London had not been stilled. Also on January 20, again writing on behalf of Lord Cherwell as well as himself, Anderson sent an immediate precedence, “Hush Most Secret” telegram to Churchill. Anderson conveyed nothing of the equivocal guidance he and Cherwell had given to the Tube Alloy scientists. Of the new U.S. policy, much as he already had said in his January 11 letter, Anderson told Churchill that “there is to be no further interchange of information in regard to many of the most important processes. . . . Pretext for this policy is need for secrecy, but one cannot help suspecting that the U.S. Military Authorities who are now in complete control wish to gain an advance upon us and feel that, having now benefitted from the fruits of our early endeavors, they will not suffer unduly by casting us aside. . . . We hope you will be able to prevail upon the President to put matters right. If not, we shall have to consider drastic changes in our programme and policy.”78

On January 23, Churchill himself sent a “Hush Most Secret” message of reply directly back to Sir John Anderson stating, “I may be obtaining most satisfactory personal assurances but it is thought better not to send telegraphic instructions from here.”79 Churchill’s personal message reassured the Tube Alloy community, if only for the present.80

*

The Casablanca Conference was extended three days in large part to allow for delicate maneuvering by Roosevelt and Churchill to bridge the estrangement between two competing French leaders. They were Free French Gen. Charles de Gaulle and the surviving leader of the former Vichy forces in North Africa, Gen. Henri Giraud.81 Through a process of cajolery and threats with lots of help from Harry Hopkins and British Foreign Minister Sir Anthony Eden, the endeavor culminated in a much-photographed and wary public handshake by the two generals before Churchill and a delighted FDR.

This happened at a concluding garden press conference on January 24, forever to be remembered for Roosevelt’s controversial declaration that the Allies would prosecute the war until the Axis surrendered unconditionally. FDR’s preceding remark that the French generals’ handshake reminded him of the ending of the American Civil War with a handshake between Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. “Unconditional Surrender” Grant left an impression that the president’s announcement of an Allied policy was impromptu. It was not.

On January 7, before any of them left for Casablanca, Roosevelt told the JCS that he would discuss with Churchill “the advisability of informing Mr. Stalin that the United Nations were to continue on until they reach Berlin, and that the only terms would be unconditional surrender.” He did so, and in the days before the January 24 press conference, Churchill approved provided that Italy was left out of the declaration.82 By the conclusion of the military talks in Casablanca, with everyone aware that the second front could not be opened in 1943, FDR and Churchill had still stronger reason to reassure Stalin that his western allies would not attempt to end the war short of Nazism’s unconditional surrender. Speaking from a prepared text, that reassurance was Roosevelt’s intent.83 FDR’s unconditional surrender statement remains controversial to this day.

Churchill and Roosevelt departed Casablanca by road for Marrakech. There they enjoyed an evening of peace in a villa with a sublime view from the villa’s tower of the Atlas Mountains at twilight. On the morning of January 25, Roosevelt flew off to retrace his route back to Washington.84 In two hours, Churchill made his only painting of the war as a future gift to FDR and left for Cairo and a meeting in Turkey with that country’s president, Ismet Inönü.85

Except for Brooke, who went with Churchill, the British chiefs returned to London satisfied with the commitment to invade Sicily as the next Allied operation but also with the responsibility to set up the new Allied organization to plan for a return to the Continent. The American chiefs returned to Washington with an acute sense of having been bested roundly by superior British coordination and staff work. Knowing the CCS would meet again in the spring, they vowed not to come off second again.