Epilogue

It is on the beaches that the fate of the invasion will be decided . . . during the first twenty-four hours.

—Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, December 1943

I was on Omaha Beach on D-Day and I tell you we hung on there by our eyelashes for hours.

—Gen. Thomas Handy

The Texas Task Group joined with soldier-filled assault ships and craft, from Portland on England’s south coast, to become part of Force O. Royal Navy cruiser HMS Glasgow took the lead as Force O cleared Point Z, the “Piccadilly Circus” assembly area, in darkness. At General Quarters, steering against a strong westerly crosscurrent, the assault craft pitching miserably in the chop, at 2244 on June 5, 1944, Force O silently proceeded down Swept Channel Three through the minefield leading to Omaha Beach.1 The gunfire support ships of the Texas Task Group would remain at Battle Stations for the next forty-two hours. The troops they supported would fight the battle of their lives.

*

The plan for Operation Neptune that was executed on D-Day was not as envisioned in the COSSAC “Overlord Outline Plan,” which had sufficed to win conditional approval from Roosevelt, Churchill, and the Combined Chiefs at Quebec. The COSSAC plan and the forces for it had been expanded, just as defenses of the beaches and fields on which the Allies would land were being made much more formidable by the Germans.

Consensus had emerged among the Allies by the end of 1943 to recognize that COSSAC’s three-division plan for the initial assault into Normandy would be insufficient to achieve success. Quickly, upon taking his post as Supreme Allied Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower assigned his land force commander for Overlord, British Gen. Bernard Montgomery, to lead a new assessment of what would be required. Montgomery sharply criticized COSSAC’s plan, which had been constrained to the forces the CCS had allotted in May 1943. His recommended increases actually were in line with what General Morgan and his staff would have preferred almost from the outset.2 By January 24, Eisenhower had the combined recommendations of his land, air, and naval commanders. From his new Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force in London, Eisenhower submitted the recommendation to the Combined Chiefs of Staff.3

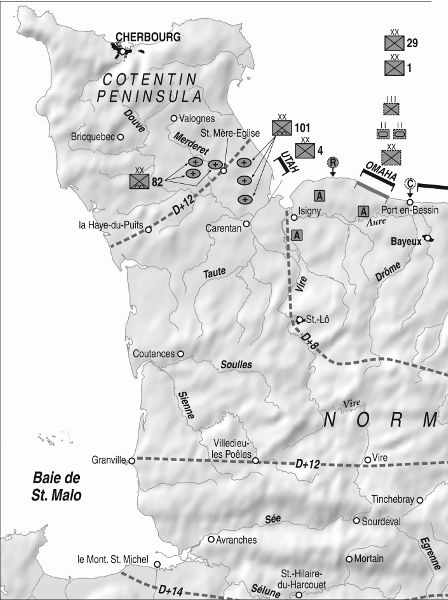

Map 3. The COSSAC 1943 Overlord Plan and D-Day as Carried Out (Neptune). Map by Philip Schwartzberg, Meridian Mapping.

By D-Day, the COSSAC plan had been expanded from three to six divisions assaulting from the sea onto five landing beaches (increased from three) on a frontage broadened to sixty miles.4 Three airborne divisions, one British and two American, would jump into Normandy behind the landing beaches. The expanded assault force required in support many more fighter squadrons, hundreds more troop carrier aircraft, and the addition of one more complete naval assault group.5 To permit assembling this larger force and all its support in the United Kingdom, the date for the invasion was shifted from May 1 to as early as possible in June.

Eisenhower’s January request for expansion met not with hesitation but with shared commitment and determination. For Overlord, the Combined Chiefs found the requested additions “reasonable” and fulfilled them. To also sustain the now-delayed supporting landing into southern France (Anvil), they were prepared to get the resources needed “by hook or by crook.”6

The sober-eyed reassessment of the COSSAC plan by Eisenhower and his deputies was rooted in the lessons of recent combat and evident fact: the experience they had gained, individually and as a team, in what had been required in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy to fight the Germans and win. They also knew that their enemy was going to test that hard-won knowledge further. Through signals intelligence, and tactical reconnaissance, they could see for a fact that the defenses they would confront in Normandy were strengthening rapidly for the worse.

Anticipating an Allied invasion in 1944, Hitler foresaw an enormous threat as well as a valuable opportunity. A successful Allied landing in France would be a dagger pointed at the heart of the Reich. If the Allies could be thrown back into the sea, however, they would not be able to try again for at least a year. Should the invasion be defeated, German forces could be transferred from west to east in an attempt to stop the advancing Russians and possibly end the war with German borders unpenetrated.7

In December 1943, at Hitler’s order, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had made a tour of inspection of the Atlantic Wall. Surveying with his knowledge of the ferocity of the battlefield attack of which the Allies were capable, particularly with their air power, Rommel saw weaknesses so pervasive as to suggest to him that the Wall was “an enormous bluff.”8 He found much of the Wehrmacht force stationed there to be comprised of poorly equipped and unfit units passed over for or in recovery from fighting on the eastern front. Rommel took particular note of the thin defenses in Normandy.

By D-Day, over the five months since his inspection, Rommel had been beefing up at a furious pace the anti-invasion defenses in depth with fortifications and millions of mines.9 Although his work was not complete, he had increased and reinvigorated the troops. By May, the Germans’ mobile reserve for counterattacking included first line panzer divisions that were positioned relatively forward in Normandy, but not consistently so. Particularly worrisome to Eisenhower were increases in German strength in the Cotentin Peninsula into which the two U.S. paratroop divisions would make a night jump.10

However, the Germans were in a strategy disagreement over how to use their mobile armored reserves, the Panzers, in response to an invasion. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the commander of the western front, with support from panzer expert Gen. Heinz Guderian, wanted to allow the Allies to move inland before he sought decisive battle in the interior of France beyond the range of the Allies’ naval guns. Rommel believed that the strength of Allied tactical air power would never permit the panzers the freedom of maneuver essential to von Rundstedt’s strategy.11 He wanted the armored units well forward for rapid counterattack before the Allies could get off the beaches.12 Rommel’s preference would put the panzers right under the Allies’ naval guns. The conflict between von Rundstedt and Rommel, which showed in the positioning of the mobile reserves on the eve of D-Day, was never resolved fully.

COSSAC’s “Overlord Outline Plan” had been conditional in part on there being no more than twelve first line German division equivalents in France on D-Day. In their January reassessment of the plan, the Allies had dropped that condition, which would not be met. In late May, British intelligence advised that the German division equivalents in France could be up to sixteen in number, and many would be units of higher quality.13

As the Germans were divided on how to deploy their reserves, the massive enterprise of Overlord was the Allies’ maximum possible effort and not easily readjusted. On D-Day, both sides would be rolling iron dice.

*

Texas had a particular initial fire mission for D-Day morning, one vital to the success of Neptune, Pointe du Hoc. The promontory of Pointe du Hoc lies between Omaha and Utah Beaches. The Germans had established a 155mm gun battery there, protected by thick reinforced concrete fortifications. If not taken out, these guns could sweep the armada and landing beaches with fire at the most critical moment.

At H-Hour, 0630, all along the sixty-mile frontage of the Allies’ assault, naval gunfire erupted from battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. Shells from the ten-gun, 14-inch main battery of Texas pounded into the German emplacements atop Pointe du Hoc as U.S. Army Rangers scaled its cliff from the sea below despite Germans shooting downward and grenading from above. Fighting at close quarters and scrambling over and around shattered concrete and massive shell craters, still visible today, the rangers who made it to the top found the gun emplacements . . . empty! Later on D-Day, the rangers found the guns hidden a mile inland and spiked them.

Timed to the Channel’s tides, the assault troops hit the five beaches in serial from west to east: first the Americans at Utah followed by Omaha, then the British at Gold, Canadians at Juno, and British at Sword. The difference in timing, though slight, afforded the beaches to the east a somewhat longer period of naval preparatory fire. To the east, the British and Canadian assault troops made good progress in establishing themselves ashore. At Utah, tidal crosscurrents put the first wave landing force ashore a mile away from where it intended to land. Unanticipated, this had the good effect of avoiding heavier than expected German defenses, but threatened to disperse the troops to follow. Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ashore in the first wave responded under fire to make a decision critical to redirecting the incoming waves of troops: “We’ll start the war from right here!”14

On Omaha Beach, the American Twenty-Ninth and First Infantry Divisions were in serious trouble. Hundreds of Allied bombers had been assigned to salvo the beach and defenses on the escarpment above it. However, fearful of hitting the inbound landing craft filled with troops, the bombers had dropped their loads moments too late in their flight, causing their bombs to land too far inland. That left the German defenses at Omaha relatively unscathed and created none of the craters among the beach hummocks that the troops hoped to use as cover in their advance. Looking down from the escarpment, the German defenders directed withering fire into the growing mass of troops, soon pinned on the beach, and into the landing craft offshore.15 The landing stalled with the troops taking heavy casualties only yards beyond the water’s edge. The next tide soon would inundate the heavily mined beach, littered with dead and wounded. By 0830, the navy beach masters had stopped further waves of troops and equipment from coming ashore. This set many loaded landing craft to milling around, among Rommel’s mines and half-submerged obstacles, while taking shellfire from the Germans. On Omaha Beach, realization of Churchill’s worst fears for Overlord appeared imminent.

Navy Lt. George Elsey of the White House Map Room was at Normandy for D-Day, having obtained FDR’s approval for this temporary duty to gather information for naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison.16 Elsey went with the Force O intelligence officer, Cdr. Curtis Munson, in a small boat from the command ship USS Ancon to investigate the disturbing reports coming from Omaha Beach. On their harrowing trip, Elsey found that “everywhere was the same: wrecked, swamped, broached, burning boats; tanks, guns, and trucks in a flotsam of fuel cans, cartridge cases, life belts, soldiers’ packs—and bodies of men killed by enemy fire or drowned in the onrushing tide.” Over the din of gunfire, explosions, and revving boat engines, Munson shouted to Elsey, “It’s in the balance now. You can’t tell which way it’s going.”17

Overlord advocate Maj. Gen. Thomas Handy and his convert to the strategy, Rear Adm. Savvy Cooke, had flown from Washington to be present for D-Day. They could have observed from relative safety aboard the Ancon, miles out in the Channel. Instead, they had gone ashore at Omaha Beach with the troops in the early hours when the issue was in serious doubt. With their firsthand information, Handy and Cooke returned to the Ancon to report to V Corps commander Lt. Gen. Leonard Gerow. Withdrawing from Omaha Beach was being seriously considered. Asked his opinion by Gerow, Handy replied, “Gee, the only thing I see that can be done is push the doughs in far enough to get that beach out from under small arms and mortar fire because as Savvy Cooke describes it, ‘this is carnage.’”18

The Americans would stay and push inland. Handy and Cooke left Ancon to go back to observe the fighting along the American beachheads.19

On Omaha, the Army could not get its artillery ashore on schedule. To compensate for that, Navy destroyers, some of which had escorted UT convoys, moved inshore, so close that some nearly grounded. Anchoring so as to be more stable gun platforms, despite drifting mines, the destroyers fired thousands of rounds from their five-inch guns to support the infantry and the handful of tanks that had made it ashore. At times, the destroyers’ 40 millimeter antiaircraft guns joined the close in battle, firing nearly point blank. Radio communication with the beach largely had been disrupted by casualties among the shore fire control parties. The destroyers effected a silent coordination with the troops by observing through binoculars and directing their own gunfire to where the troops were firing.20 So it was that in initially small groups the troops advanced up from the beach. Navy Combat Demolitions Units, while taking 41 percent casualties, began to make real progress in clearing obstacles and opening up beach exits to move inland.21

D-Day dawned for the people of Normandy bringing the thrill of liberation in equal measure with violence, uncertainty, and fear. Shepherded by his mother, five-year-old Jacques Delente sheltered with his extended family inside a dormant lime kiln. All day long in the dark, they could hear the noise of the battle being fought outside. Too young to be afraid, Jacques peered upward through the kiln’s chimney excited to see Allied planes racing across his patch of sky. When the family returned home, they found on their dining room table a German soldier who had died from his wounds and been left by his comrades in retreat.

The day after D-Day, when Lieutenant Elsey went back to Omaha Beach, the scene was being transformed. The escarpment taken, fighting had moved inland. Engineers were clearing obstacles and building roads up to the heights. Troops, tanks, and guns transported from England in LSTs were streaming over the beach and toward the slowly expanding American frontlines. Standing on the beach, Rear Adm. John Hall, a veteran of the Mediterranean landings, said this to Elsey of “Easy Red,” a critical section of Omaha Beach where the day before nothing had been easy: “This is the most strongly defended beach I’ve ever seen. In another month, we might not have made it.”22

As Americans, up from the western beaches, linked up with the paratroopers and fought field by field through the thick hedgerows in the bocage, the Germans were attempting to mount an armored counterattack in the Anglo-Canadian sector to the east. If the Allies were allowed time to establish their armies ashore, Rommel was certain all would be lost.

Between Caen and Bayeux stretches a broad, open plain that slopes down to the beaches where the British and Canadians came ashore. This good tank country had been a concern for the Allies from early in COSSAC’s planning. From Juno Beach, on D-Day, according to plan, the tank and mobile artillery-heavy Canadian Third Division had pushed inland to take up a defense of the beachhead on this plain. The Germans needed to capture a “start line” for what Rommel hoped would be a three-division armored attack by the First Panzer Corps to drive the Allies into the sea. But their attempts to capture ground for the start line were frustrated. Repeated, fanatical attacks, June 7–10, by the Twelfth SS Hitler Youth Division broke against the Canadians’ skilled and steadfast defense.23

While the panzers were trying and failing to gain position for their counterattack, more Allied strengths took decisive effect against the Germans. On D-Day, the Allies owned the skies over Normandy. The growth in the German fighter force in 1943 had been overcome and reversed. The Luftwaffe had been so depleted in defending Germany against the Combined Bomber Offensive that it lacked the planes and pilots to make anything but a token response to Neptune. Allied fighter-bombers roamed the region beyond the beachhead striking any German unit.

Liberation of Europe from the west was in the balance for the Allies in this critical battle. Given that, the Allies’ concern about compromising Ultra, their access into German encrypted communications, did not prevent application of this priceless intelligence now, tactically. Movement to the front of German units was hindered and German command and control was particularly hard hit by fighters directed on the basis of sanitized Ultra-based reports to strafe, rocket, and bomb field command posts.24

Time to mount a counterattack toward the beachhead was running out when the vast Allied deception program that had supported D-Day for months now induced the maldeployment of German reinforcements at the critical time. Deceived by the Allies’ Fortitude South operation into accepting the existence of an imaginary First U.S. Army Group, still in England, alarm spread in the German command. Normandy was a feint, German High Command and Berlin believed. The real blow was about to land elsewhere. Orders were cancelled for panzer units of the German Fifteenth Army in Belgium and northern France to move south toward Normandy. They were ordered instead to stay to defend against the main Allied landing to come in the Pas de Calais, a fictional threat generated and sustained by Allied deception.25 Denied position and reinforcement, the greatest potential threat to the Allied beachhead dissipated.

The Germans put up fierce resistance all around the beachhead’s perimeter for over a month, but they could not stop the buildup of forces for an Allied breakout to liberate northwestern Europe. Despite a major Channel storm June 19–22 that destroyed one of Neptune’s two artificial harbors, the crucial, over-the-beach logistical battle to reinforce and sustain Overlord recovered and continued to great effect, even after French ports were liberated and put back into operation. In July with Operation Cobra, the Allies broke out to begin their eastward dash across France. The critical first phase of Overlord had been won.

Before D-Day ended, elements of twelve divisions were established on the landing grounds and beaches of Normandy, not to be pushed off. Their numbers swelled daily until, after 336 more days of hard fighting, the Allied armies from the west and the Red Army from the east ended the war in Europe. When Germany surrendered unconditionally on May 8, 1945, Operation Overlord concluded in victory.

*

Overlord’s preparation and implementation was paced by the progress of the atomic bomb project in the United States. Work to develop an atomic bomb at secret locations in the United States had expanded and accelerated dramatically, and since the resumption of Anglo-American atomic cooperation in September 1943, British scientists were integral to it. The Manhattan Project was developing two bomb designs in parallel. The simplest and most certain but wasteful of fissile material was the gun-type. In this design, a uranium-235 bullet was fired into a uranium target to achieve nuclear fission. The scientists had so much confidence in the gun-type bomb that they froze its design in February 1945 and skipped conducting an explosive test before releasing this bomb (when ready) for combat. The second implosion-type bomb design used an extremely precise conventional explosion to implode a spherical, hollow core of plutonium (U-239), a new element created from uranium. In March 1945 the design for the implosion-type bomb was frozen, but that proved to be no assurance of smooth sailing.26 Design and production of the implosion-type bomb presented challenges never before addressed that would throw the project into crisis several times.

By November 1943, direct British participation in the Manhattan Project had grown to around two dozen scientists, a dozen of whom were living at the secret Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.27 Among the British scientists at Los Alamos were the Austrian émigré Otto Frisch and the young German theoretical physicist Klaus Fuchs. Again and again, Frisch’s innovative work would prove critical to success in designing the implosion-type bomb.28 Having slipped through British security screening, Fuchs, on the other hand, had begun covertly passing atomic secrets to the Soviets in London and continued to do so from Los Alamos.29

Manhattan Project costs indicate its quickening growth. From $16 million for all of 1942, expenditures increased to $344 million in 1943. That figure was topped in just the first half of 1944 with expenditures in each month to follow projected to approach $100 million.30 Adjusted for inflation, the cost in 2018 U.S. dollars would be $100 billion through mid-1944 and growing at $1.3 billion per month.

The atomic bomb team still had ahead of it serious obstacles in physics, engineering, and production. However, their progress thus far had a palpable effect of optimism mixed with foreboding. This extended to the worldview of the project’s mixed scientific-military-political appointee leadership. Reporting back to Sir John Anderson in London on work of the Anglo-American Combined Policy Committee, unknowingly apace with imminent D-Day, Ronald Campbell wrote on May 31, 1944, that

we note a natural but increasing sense of American self-confidence and buoyancy as to their ability to carry through this project. On the part of some Americans this is accompanied by a growing sense of responsibility and anxiety about their ability to play their just role in international affairs; on the part of others there is certainly evidence of a thought that this weapon can be kept a tight monopoly and can thus give the maximum protection to America.31

On the other side of the Atlantic, too, the dissonance between the promise and danger of atomic energy spurred actions to call attention to the postwar future. In April 1944, Sir John Anderson had appealed to Churchill to approach FDR about eventual postwar control of atomic energy.32 Supported by Lord Cherwell, Anderson encouraged and facilitated the renowned and like-minded Danish physicist Niels Bohr to meet with Churchill. Bohr held the view that the best opportunity for postwar international control of the atom was to take the Russians into the Allies’ confidence at a surface level before the bomb became a demonstrated reality. In this, Bohr was ahead of Anderson who, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, would come to support inclusion of the Russians in control measures. Bohr certainly was ahead of Churchill and FDR.

Bohr’s meeting with Churchill, a week before D-Day, went badly. Bohr already had met at the White House in March 1944 with Roosevelt. In that meeting, as had many before him, the scientist had mistaken ambiguity for encouragement.33 Bohr’s meetings were failures, producing in both leaders only suspicion.

To the postwar military importance of the bomb, Lord Cherwell asked Churchill from London on September 18, 1944, to “try to discover from the President in broad outline what the Americans have in mind about [joint] work on T.A. after the war ends.”34 That day, meeting with Roosevelt at Hyde Park, following the Second Quebec Conference (Octagon), Churchill and FDR agreed to a one-page aide-memoire on Tube Alloys that they initialed in the early hours of September 19. They rejected a proposal that the world should be notified about the bomb “with a view to an international agreement regarding its control and use,” and specifically directed that Dr. Bohr be prevented from “leakage of information, particularly to the Russians.” Roosevelt and Churchill then agreed that “full collaboration between the United States and the British Government in developing Tube Alloys for military and commercial purposes should continue after the defeat of Japan unless and until terminated by joint agreement.”35

The president never told his advisers on atomic matters, including his secretary of war, of the aide-memoire’s contents.36 Vannevar Bush suspected there was an agreement to an exclusive Anglo-American partnership. This both Bush and Conant opposed, fearing that it would stimulate an atomic arms race with the Russians.37 Stimson had been open to an international control regime that included the Russians if the right conditions could be secured verifiably. But growing friction, suspicion of postwar intentions, and loss of confidence in Russia’s word caused Stimson to change his position.38

On April 12, 1945, Roosevelt died in Warm Springs, Georgia. Having led the country out of the existential crisis of the Great Depression, he did not live to see victory in the war, in which his leadership had been so essential. He also had not told the vice president who succeeded him about the atomic bomb.

The new president, Harry Truman, was told informally about the atomic bomb by both James Byrnes and Henry Stimson within twenty-four hours of taking office. Not until April 25 did Truman receive a detailed briefing on the Manhattan Project from Secretary of War Stimson and General Groves. Foreign affairs, particularly increasingly adversarial relations with the Soviet Union, were discussed at length in the context of the bomb’s political-military implications.39

In a conference room at the Pentagon two days later, on April 27, the Target Committee, composed of Army Air Force officers and a small Anglo-American group of Manhattan Project scientists, met for the first time. They were gathered to identify four cities in Japan as candidate targets for an atomic bomb. Theirs was not an easy task. The night firebombing of Japanese cities by Twentieth Air Force B-29s had been under way since March. Not many “pristine” targets remained in Japan.40 The target selection criteria stipulated by General Groves, to whom the committee would report, assigned secondary importance to military effectiveness. Not an airman but an Army engineer, Groves’s primary criterion fit exactly the interwar air power theory of bombing to break a people’s morale, a theory not proven in six years of European war. For the committee, Groves recounted in his book, “I had set as the governing factors that the targets chosen should be places the bombing of which would most adversely affect the will of the Japanese people to continue the war. Beyond that, they should be military in nature.”41

The Target Committee recommended Kyoto and Hiroshima as their first and second choices. Over the weeks that followed, Stimson, who deeply appreciated Asian culture, had become ever more appalled by the human toll of the conventional firebombing raids. In a May 30 meeting with Groves, Stimson learned that the general would deliver the target recommendation to General Marshall the following day. The civilian secretary intervened in this military decision by immediately removing from the list Kyoto, Japan’s ancient former capital and storied center of culture.42

Into the summer, the scientists at Los Alamos struggled to overcome challenges to prepare the implosion-type bomb for a test while a gun-type device, “Little Boy,” was readied for shipment to war. On July 16 at 5:30 a.m. in the desert outside Alamogordo, New Mexico, the first atomic bomb was detonated at Trinity Site with a yield of 18.6 kilotons in a flash brighter than the sun. Four hours later, the cruiser Indianapolis departed San Francisco carrying the gun-design bomb, Little Boy, on its long Pacific voyage to be delivered to the B-29 that would drop it on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.43 Three days later on August 9, an implosion-type atomic bomb would be dropped on Nagasaki. On August 15, making a radio address to his people, who were hearing his voice for the first time, the emperor announced that Japan would surrender to the Allies. Certainly an important element, the nature and relative weight of the two atomic bombs’ influence on Japan’s decision to end the war when it did continues to be debated. So bombing casualties suffered by the Japanese remain estimates with the pervasiveness of destruction precluding certainty. In combination, the conventional fire bombing and the two atomic bombs took at least 330,000 lives but possibly as many as 900,000.

At the time of the Trinity test, the victorious Big Three were meeting at Potsdam, Germany, a suburb of Berlin for the Terminal Conference. When President Truman received word of the scientists’ success a few hours after the bomb test, he decided to tell Stalin, but asked Churchill’s advice on when and how. Apparently unaware of Soviet espionage, Churchill advised framing Truman’s communication as a test of which the two of them had just learned. The intent was to avoid being asked in response why the Russians were not told sooner about their allies’ Manhattan Project.44 Truman did so without revealing any details of the bomb test. Not apparent in the Soviet premier’s reaction was that Stalin already knew about the atomic project and was confident that he soon would know the details of the Trinity test.

The six-year cataclysm of war in Europe had concluded with the Nazis regime crushed and freedom restored to half of the European continent. The approval for Overlord, so critical to this victory, had in its advocacy intertwined with agreement to cooperate in developing the atomic bomb. With the European war barely ended, an ominous new era of global nuclear anxiety was dawning.