Graham Lock

One evening in 1926, Bessie Smith’s traveling tent show company arrived in a little town near Cincinnati and, because the streets were flooded, had to be transported by boat to their lodgings above an undertaker’s parlor. This inauspicious event engendered three remarkable works of art. First, Smith wrote “Backwater Blues” and, with the help of James P. Johnson on piano, turned it into one of her finest recordings.1 When, by chance, the disc’s release coincided with the terrible Mississippi floods of 1927, the song gave moving voice to the sufferings of more than half a million displaced people along the delta. Then, marking its status in the black community, Sterling Brown featured the song in his “Ma Rainey,” widely regarded as the definitive blues-related poem of the twentieth century.2 Finally, nearly two decades later, a young painter named Rose Piper, who had just bought the Smith recording on Sterling Brown’s recommendation, was inspired to make Back Water, a canvas of haunting emotional power.

However, while Smith’s performance and Brown’s poem are now rightly acknowledged as great art, Piper’s work has, for a variety of reasons, remained largely overlooked by art critics and little known to the wider public.3 This is all the more regrettable because, as well as Back Water, she made a number of other canvases in response to recordings by classic blueswomen such as Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith that include some outstanding examples of early semi-abstract expressionism. They may also be the first paintings directly inspired by blues records.4 So I want here to take a closer look at Piper’s art and to pursue what I think is a key question: to what extent did the blues she heard prompt and guide her experiments with abstraction?

First, a little background.5 Piper was born Rose Theodora Sams in New York City on 7 October 1917.6 She got her BA (majoring in art, minoring in geometry) from Hunter College in 1940 and attended the Art Students League from 1943 to 1946, where she studied with Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Vaclav Vytlacil. Though raised in the Bronx, where her father taught Greek and Latin in the public school system, she became fascinated by her parents’ stories of the South and began to research African American folklore. She was introduced to Sterling Brown by the poet Myron O’Higgins, who was a student of Brown’s at Howard University, and it was Brown, an expert in black folklore, who tutored her in the blues and advised her to seek out Race records in Harlem, which she duly did. “I ran out and got all kinds of recordings and listened to them,” she recalled in 1989, adding with a laugh, “I worked at it.”7

In January 1946, she applied for a Rosenwald Fellowship—“to do a series of paintings depicting first, the folk Negro, urban and rural, as he comments on himself in his blues”8—and in April was awarded a grant of $1,500. This money enabled her to spend the summer of 1946 traveling in the South, especially Georgia (where her father had family), an experience she later described as “worthwhile for the sights and sounds and feel to be imbibed from the people who seem to have fashioned the very substance of the blues.”9

The end result of Piper’s research and her immersion in blues records was her first solo exhibition, entitled Blues and Negro Folk Songs, which ran at New York’s RoKo Gallery from 28 September to 30 October 1947.10 Of the fourteen works on display, twelve were related to blues and folk themes: these were Lula, Guitar Blues, Back Water, I Been to the City, St. Louis Cyclone Blues, Conjur, I’m Gonna Take My Wings and Cleave the Air, Long, Long Time to Freedom, The Death of Bessie Smith, Slow Down, Freight Train, Grievin’ Hearted, and Empty Bed Blues. 11 (The two remaining canvases were Subway Nuns, based on lines from a poem by Myron O’Higgins, and Circus Clowns.)12 The exhibition proved a great success: it was well received in the press, its run was extended for an extra week, and many of the paintings were sold.

By this time Piper had her own studio in Greenwich Village and was a rising star on the New York art scene. She was friendly with painters Charles Alston (who had adopted her as his protégée),13 Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence, and with sculptors Richmond Barthé and Glenn Chamberlain, and she also knew several writers and musicians, including James Baldwin, Billie Holiday, Langston Hughes, and Claude McKay. She liked to party, too: as she told Ann Eden Gibson in 1989, “There was a club in Harlem called the Mimo, I’d come in and they’d line up seven Alexanders on the bar for me. I loved to go and dance. I had the greatest time. The world was at my feet.”14

Certainly her reputation continued to soar. In April 1948, Grievin’ Hearted, one of the RoKo show paintings, was awarded the prize for Best Portrait or Figure Painting at Atlanta University’s Seventh Annual Exhibition of Paintings, Sculpture and Prints by Negro Artists.15 This was the top purchase prize at what was then one of the most prestigious competitions open to black artists. (Other entrants that year included Barthé, Lawrence, Bob Blackburn, and Hale Woodruff.)16 Piper herself spent several months of 1948 in Paris, thanks to a second Rosenwald Fellowship. She returned to New York confident of securing a prominent place in the art world: as she recalled in 1989, “I felt that nothing could stop me.”17

The paintings from the RoKo exhibition suggest that Piper’s belief in her talent was not misplaced. What seems to have most impressed the critics was her “new and striking” approach to paintings with a social theme, an approach she described at the time as “a liberation of style” that had come about as she worked on the Blues series.18 Romare Bearden, visiting her studio prior to the RoKo exhibition, noted that Piper “has been investigating new avenues of approach to her subject matter. Her latest efforts are created out of broad semi-abstract planes, in which she employs a restrained palette in keeping with her concept of the subject.”19 Reviewing the show some months later, the critic from Art News made a similar observation, contrasting “early luminous romantic canvases” with “recent pictures [that] are strong, flat, semi-abstract compositions, simple in design and somewhat mournful in their color harmonies.”20While such a stark contrast fails to do justice to Piper’s assurance across a range of stylistic gradations, from the subtly expressive realism of Back Water to the flattened perspectives and geometric shapings of Slow Down, Freight Train and The Death of Bessie Smith, it does confirm that her art had moved toward what she too would later characterize as a “semi-abstract expressionism.”21

This shift to semi-abstraction did not entail any desire to create a nonreferential art: the human figure remains at the center of the Blues and Negro Folk Songs paintings. While some of her abstract expressionist contemporaries may have been eager to get away from recognizable subject matter and accessible meaning, Piper kept such considerations at the forefront of her art, which she saw as having a specific political purpose: “to help to erase segregation, ridicule, humiliation and violence” and to “[fight] injustice the best way I know how—by putting it on the canvas.”22 Working with the blues enabled her to pursue these goals because she regarded the music itself as a valuable form of social commentary on black life and black history:

The Negro sings about how weary he is of being hungry, diseased, overworked, oppressed and lynched. He sings about flood-waters, meagre crops, the need for travel. From the plantation shacks, from the wharves, from the fugitive slaves in the hills came voices that sang of trouble, death, humor and hope—a rising, swelling torrent of expression that for the most part was unheeded, ignored and denied.23

Many of these themes are reprised in Piper’s RoKo paintings. However, remembering Bearden’s comment that her “concept of the subject” had influenced her color palette, we may wonder if listening to all those blues recordings also affected her thinking about other formal criteria—if, perhaps, it was a factor in her embrace of semi-abstraction.

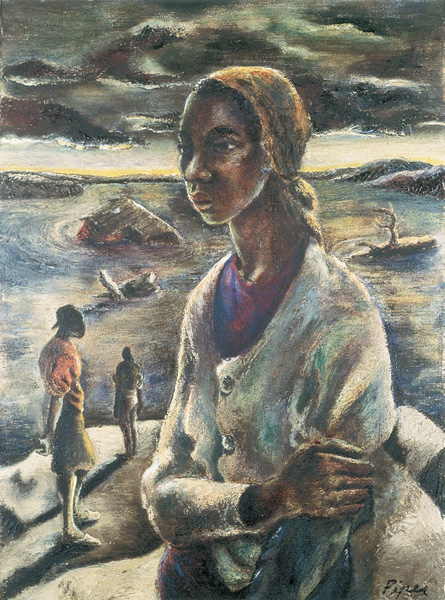

Several of the Blues and Negro Folk Songs series refer to specific recordings, so by comparing painting with disc we may be able to identify how the blues has left its traces on the canvas.24Back Water,25 painted in 1946, is one of Piper’s earlier works and while there is a small degree of stylization (for example, in the delineation of the central figure), it is less abstract than many others in the series (Figure 2.1).)26Its relationship to the recording that inspired it could be described as fairly literal: the painting appears to illustrate Bessie Smith’s lyrics, so we are shown flood waters, thunderclouds, homeless people, a collapsed house, and in the foreground a young woman on a “high and lonesome hill,” as described in the song. The young woman, who looks numb with shock, presumably corresponds to the singer’s persona: her facial expression and body posture are certainly evocative of the singer’s closing lines, in which, literally bemoaning her plight, she laments that she “can’t move no mo’, ” and has no place to go.27

Figure 2.1 Rose Piper, Back Water. 1946. Oil on canvas, 30 in. × 22 in. © Rose Piper Estate. Courtesy of Kenkeleba Gallery.

But there is a sense in which the painting could be said to reflect the sound of the recording as well. The figure of the young woman is the dominant presence in the painting, much as Bessie Smith’s voice commands the recording, and both convey a somber air of strength muted by tragedy. The young woman’s immobility, underlined by the arm across her body and the emphatic handclasp of the elbow (as if she is trying to hold herself together), is comparable to the singer’s lack of dynamic variation and contrasts with the background activity of swirling waters, floating debris, and looming clouds, much as Smith’s restrained vocals are offset by James P. Johnson’s agile piano responses, as he animates in sound the lyrics’ verbal imagery. What I am suggesting is a kind of emotional and formal match between painting and recording that may be attributable, at least in part, to Piper’s listening to the performers and then allowing what she heard to inform not only the scene she depicted but also how she composed it.

While it is not clear whether Slow Down, Freight Train was painted in 1946 or 1947, this painting represents a very different aesthetic approach to that of Back Water: this is Piper at her most semi-abstract (Figure 2.2). When the Ackland Art Museum acquired the work in 1990, director Charles Millard wrote to Piper, inquiring about the origin of the title.28 Piper replied that the title referred to “Freight Train Blues,” a recording by Trixie Smith, who “sang and recorded the misery of the women who had been left behind by men who hopped freight trains to the North.” She explained:

Part of “Freight Train Blues” goes as follows:

“When a woman gets the blues, she goes to her room and hides

“When a woman gets the blues, she goes to her room and hides

“When a man gets the blues, he catch the freight train and rides.”

The title of my painting is a woman’s plea for the train to slow down so she might go along with her man.29

(Piper seems to have confused the two different versions of “Freight Train Blues” that Trixie Smith recorded. The first, made in 1924, includes the lines that Piper quotes, but actually concerns the singer’s desire to escape from her man: “Gonna leave this town/’Cause my man is so unkind.” However, when Smith re-recorded the song in 1938, she changed the lyrics so the singer does want to catch the freight to follow her man, but she also omitted the lines that Piper quotes.) 30 The more abstract approach does not indicate any lessening of interest in representation on Piper’s part. The human figure remains the chief focus of the painting, which follows the example of the recording in addressing the social theme of economic migration through a depiction of its emotional cost in a very personal context.

Yet there is not the literal relationship to the song that we saw in the case of Back Water. Rather than put the singer—or her persona—in the picture, Piper has painted it as if from her perspective (an early example of the female gaze?), so the central image is of her man departing in a freight car, his highly stylized features—elongated neck, upturned ovoid head—a telling expression of his heartache. Piper later declared,“ My painting draws on the powerful passions and anguished recollections of the Black experience. The abstraction of the human figure arises out of a single moment of heightened expression. The attenuated form suggests the essence of longing.”31

Figure 2.2 Rose Piper, Slow Down, Freight Train. 1946–47. Oil on canvas, 29½ in. × 23 in.© Rose Piper Estate. Courtesy of Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ackland Fund.

Here, I think, is a clue as to why Piper turned to abstraction in painting the Blues and Negro Folk Songs series: it allowed her to portray heightened expression and the essence of feeling. And the reason she wanted to portray such qualities may be that she heard them in the blues records she was playing, given that she described blues at the time as a music that was itself“ highly personal and charged with emotion.”32 Certainly the abstraction and attenuation of the departing lover in Slow Down, Freight Train gives vivid expression to his charged emotions. I would argue that the blues reveals such feelings through aesthetic processes of stylization and distillation comparable to those of Piper’s semi-abstract expressionism;33 and, as with many blues performers, Piper’s technique entails the sophisticated manipulation of a few basic formal elements—here, the play of a limited array of colors and shapes: the complementary muted background shades of greens, yellows, and browns and the contrasting bright foreground red (like a raw wound), the network of straight lines that frame—and pierce—the rounder, softer outlines of the human figure.

I am not claiming that these correspondences are due solely to Piper’s listening to the blues, but I do think it likely that she heard in the blues certain formal qualities that resonated with her own aesthetic preferences (which had presumably been shaped for the most part by her study of painting) and that, now and again, these formal qualities perhaps suggested certain equivalent visual strategies. Grievin’ Hearted (presumably titled after Ma Rainey’s recording “Grievin’ Hearted Blues”) provides a further example of this blues resonance, which here takes a slightly different shape (Figure 2.3). Kirsten Mullen, in a brief essay on the painting, has noted Picasso’s influence, particularly in the way Piper has represented the central figure of the grieving man:

The male figure in Grievin’ Hearted evokes immediate comparisons to Picasso with his stylized pose, impossibly curved spine and a general heaviness which seems to root him to the ground.“He is rooted to the spot, immobile, a statue. He’s done in,” Piper said. Her articulation of body parts is most unusual: references to musculature, particularly the delicate hand resting on the shoulder in a state of lassitude; the strong, almost sculptural toes; and tree trunk-like right arm set Piper’s work apart from the realistic figure painting of her peers.34

Figure 2.3 Rose Piper, Grievin’ Hearted. 1947. Oil on canvas, 36 in. × 30 in. © Rose Piper Estate. Courtesy of Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries.

What Piper does, I think, is to again convey highly personal and charged emotions through distortion and exaggeration of the figure: his listless despair caught in the gently rolling upper-body lines; the weight of his grief, its heavy immobility, captured in the rigid right arm and emphatic feet. Mullen is right, of course, to cite Picasso (an influence that Piper herself readily acknowledged), but—at the risk of seeming fanciful—I wonder if there could be an echo here, perhaps subconscious, of the instrumentation on the Rainey recording: the gently undulating violin lines underpinned by the heavier plucked and strummed guitar part.35 I wonder too if the blues has not had a more general impact. I am thinking of the blues tradition of vivid hyperbole—whether you are sitting on top of the world, pouring water on a drowning man, holding the world in a jug, or thinking that a matchbox might hold your clothes—which also uses exaggeration to depict feelings, much as Piper’s distortions of the scale of the male figure reveal his inner emotional state. (As, indeed, does her use of color: this is a blues painting in more ways than one.)

Ma Rainey’s record of “Grievin’ Hearted Blues” begins with the lines:

You drove me away, you treated me mean

I loved you better than any man I’ve seen

My heart is bleedin’, I’ve been refused

I’ve got those grievin’ hearted blues.36

An intriguing aspect of Piper’s painting is that she has switched the genders: it is the man who is shown grieving, while the woman can be seen walking away in the background. What prompted this change? We know this painting was based on personal experience: she explained to Kirsten Mullen in 1998,“I was very unhappy when I painted Grievin’ Hearted. It was me being broken hearted, grievin’ hearted. I had been jilted. I was that man.”37 (In 1989, she had mentioned to Ann Eden Gibson that the painting referred to the end of her relationship with Myron O’Higgins.)38 Possibly Piper found it too painful to depict herself in that situation and, taking a cue from Rainey’s line “You’ll find you love me, daddy, some sweet day,” she projected her grief onto her ex-lover at the moment of his realization of that fact. But there may be more complex reasons at play here, to do with her relationship with the blues.

Piper later recalled what a free spirit she had been in the 1940s—“I was so independent. You have no idea how independent I was”39—and suggested that she had been attracted to recordings by classic blueswomen such as Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith because she heard in their music the same strength and independence that she sought in her own life and art.40 This strength came across in their recordings, even though many of the songs ostensibly dealt with feelings of loss and betrayal. Angela Davis has pointed out:

While the overwhelming majority of Bessie Smith’s 160 available recorded songs allude to rejection, abuse, desertion, and unfaithful lovers, the preponderant emotional stance of the singer-protagonist—also true of Ma Rainey—is far from resignation and despair. On the contrary, the most frequent stance assumed by the women in these songs is independence and assertiveness—indeed defiance.41

Possibly Piper’s decision to show the male figure as grievin’ hearted was her act of defiance, inspired by the spirit of assertiveness she heard in the blueswomen. To have shown the woman grieving would have risked her artwork contributing to the kind of gender stereotyping that characterized women as emotionally dependent on men; 42 and just as the independent emotional stance of the blues-women undermined such stereotyping when it occurred in the lyrics they sang (many of which, of course, were written by men), so Piper’s switching of genders in Grievin’ Hearted can be seen as the painterly equivalent of this emotional stance, which, whatever her feelings about O’Higgins, was in overall accord with her own aesthetic and political values.43

Ann Eden Gibson has argued that what we might call the proto-feminist impact of the blues on Piper’s art went even further. Her RoKo paintings, says Gibson, reflected

her refusal to maintain the “proper” degree of feminine middle-class distance from erotic subject matter. The expressive realism of the images … [was] based not only on the veiled resistance to white economic domination chronicled in the lyrics of Negro work songs, but also on the taboo topic of female eroticism, which was made explicit in the tradition of women blues singers like Bessie Smith’s “I’m Wild about that Thing” and “Empty Bed Blues.” This subject matter suggests that she was aware of social pressures to conform to prescribed sexual roles but was determined not to accept them.44

“Empty Bed Blues” is indeed one of the blues’ more explicit avowals of female sexual pleasure and need, and in using that title Piper was presumably endorsing the truth of the song lyric, even though her painting Empty Bed Blues, which portrays a forlorn-looking young woman sitting in front of a large empty bed, is much more indirect in its representation of female sexuality.45 Still, given that the painting dates from soon after the end of World War II, when many husbands and boyfriends were still away in the armed forces, it is a work whose implications were very clear and acutely topical.

The kinship that Piper felt with Bessie Smith (“To me, she was a symbol of an emancipated woman”) meant that the singer’s death following a car crash made a deep impression on her, not least for the manner in which it was believed to have happened: “I was shocked when I first learned Bessie Smith had been allowed to bleed to death.”46 Piper’s painting The Death of Bessie Smith shows the singer lying alone in the road, her head haloed by moonlight (or streetlight), threads of blood running across her throat and winding down her arms; behind and around her is a flattened geometric landscape that evokes an urban desolation of sharp-cornered curbstones and blank-walled buildings (Figure 2.4). The semi-abstraction of the art again appears to express the essence of feeling that we saw in Slow Down, Freight Train; here the emotional core of the picture is a feeling of abandonment and isolation, of the stricken singer’s desperation at being left to die alone in a bleakly uncaring environment.

Romare Bearden was particularly impressed by this canvas, writing that: “one [work] depicting the death of the now-legendary blues singer Bessie Smith, with the highly stylized blood running along her hands, I thought evidenced real imagination and stylistic inventiveness.”47 Bearden also remarked on how well this and other RoKo paintings caught the “feeling of lament” that one hears in the blues. In the case of The Death of Bessie Smith, while the painting does not refer to a particular recording, I think it does convey something of that blues lament: the viewer feels that the singer’s cry of pain and shock is the artist’s too. In fact, I believe the painting almost certainly refers to a poem by Myron O’Higgins. A draft version of a press release for Piper’s RoKo exhibition declares that the paintings,“in a few instances,” refer to “lines of poetry composed on blues themes by Myron O’Higgins.”48 We know that Subway Nuns was based on lines from an O’Higgins poem (though not one on blues themes); my guess is that The Death of Bessie Smith is another of those instances. The poem to which I think it refers is “Blues for Bessie,” O’Higgins’s account of Smith’s death, the first and last verses of which end with the lines, “Well, dey lef ’ po’ Bessie dyin’ /wid de blood (Lawd) a-streamin’ down”49—lines that could stand as an apt summary of the painting too. O’Higgins, like Piper, believed Smith had been left to bleed to death as a consequence of southern racism and he includes one verse that focuses on the feeling of abandonment, which I think is such a powerful element in the painting:

Figure 2.4 Rose Piper, The Death of Bessie Smith. 1947. Oil on canvas, 25 in. × 30 in. © Rose Piper Estate. Courtesy of M. Lee Stone Fine Prints.

She holler, “Lawd, please help me!”,

but He never heerd a word she say

Holler,“Please, somebody help me!”,

but dey never heerd a word she say

Frien’, when yo’ luck run out in Dixie,

well, it doan do no good to pray.50

piper herself felt that the Blues series was an artistic success, declaring:

Some of the canvases appear to me to stand not far from gratifying both major concerns: that for the faithful expression of the spirit of the work songs and blues, and that for the painting of a picture that is in its completion meaningful on the most universal and aesthetic terms.51

However, she also appears to have become increasingly concerned that, by pursuing her interest in folk materials, she risked her work being open to racial stereotyping by the viewer. As a result, she abandoned plans to further explore folklore in the South and in South America (at one time she had hoped to study with Diego Rivera in Mexico) and chose instead to go to Paris. Explaining her decision to the Rosenwald Fund administrators, she argued that

to gain first attention in any degree with the folk works would be to associate myself from the beginning with folk songs, and to support the fixed idea in the public mind of the propriety of folk subjects for artists from the minorities. It could prejudice my own freedom to work outside the context of my experience as a Negro and within the larger framework of my experience as a person; it could aid in perpetuating segregation in the arts, which in its most destructive implication means the appropriation of Negro painters by their Negro materials.52

How Piper would have avoided this appropriation, what she would have taken for her subject matter, and how this might have affected her aesthetic ideas are all moot points because, on her return from Paris in 1948, a run of personal misfortunes abruptly halted her artistic career. She discovered she had sublet her apartment to a “crazy person” who, in her absence, had thrown out many of her belongings, including her clothes, her records, and her paintings: two of the RoKo works, Lula and I’m Gonna Take My Wings and Cleave the Air were lost, as was a third painting about which little is known except its title, Ain’t Got Nothin’. 53 But worse was to follow. As Piper told Ann Eden Gibson in 1989, “Everything crashed at the same time. My father got cancer, he was dying of cancer, my mother became senile, and my husband had a complete nervous breakdown—everything at once!”54

Suddenly Piper found herself the sole breadwinner for a family of six (she also had a seven-year-old son and a baby daughter) and she was forced to abandon her painting to find more financially secure work. For a few years she ran her own greeting card company before opting for employment as a textile and knitwear designer, at which she proved very successful: when she retired in 1978 she had risen to senior vice president and was acknowledged as one of the industry’s top designers.55 The downside of this success was that, for some three decades, from the late 1940s to the late 1970s, she did no painting whatsoever. “ I so regret I had to stop,” she said in 1989. “I have a lot of catching up to do. I felt like I was cheated out of thirty years of painting. I figure if I have twenty more years ahead of me, I’m gonna make it!”56

She did not have twenty more years. Following a series of strokes soon after the turn of the century, which severely impaired her mobility and her memory, Piper died in a Connecticut nursing home on 11 May 2005. But she did make a successful return to painting. Her second solo exhibition, some four decades after her first, ran at the Phelps Stokes Fund in New York from 1–13 May 1989. Again, many of her paintings had a link to African American music: the centerpiece of the new show was a series of ten miniature (12” × 9”) works based on, and titled after, lines from spirituals.57 The impetus for what Piper called the Slave Song Series had come from her reading of John Lovell Jr.’s book Black Song: The Forge and the Flame, but this time the music was not an influence—the paintings were based solely on printed lyrics. Piper told Ann Eden Gibson that she had never heard, and did not even know the tunes of, several of the spirituals she had used. Forty years later, her style was drastically altered too, the muted colors and semi-abstraction replaced now by a precisely detailed realism and an altogether brighter palette, changes Piper attributed to her experience in textile design (where she had to work within the confines of tiny grid patterns) as well as to a shift to acrylics from the oils she had used in the 1940s. Rather than Picasso, the aesthetic models she now cited were early Flemish School painters, such as Van Eyck and Memling, and the medieval tradition of the Book of Hours.58

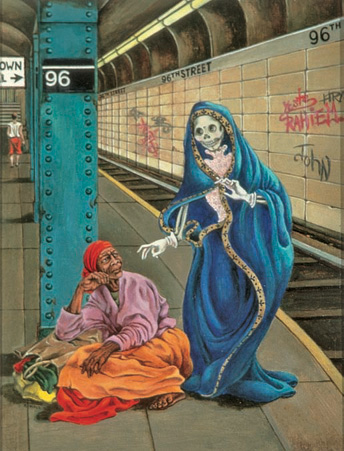

But some things had not changed. Piper saw the spirituals, as she had seen the blues, as encompassing the entire gamut of black experience: the slave, she wrote, “did not merely sing his sorrows and joys. He sang his suppressed hopes and his broken, bleeding heart…he lived to the hilt the cruel life handed him, and sang the totality of that life.”59 And her political purpose, that desire to place injustice on the canvas, remained strong: noting that “the current state of many inner-city blacks is not unlike the desperate situation of the slave ancestors,”60Piper set half of her Slave Song paintings in contemporary cityscapes, most notably I Want Yuh to Go Down, Death, Easy/An’ Bring My Servant Home, in which she depicted her local subway station, Ninety-sixth Street, where the skeletal figure of Death, dressed in a blue velvet robe and white lace gloves, waits to escort a female vagrant, who sits crumpled in rags on the platform floor (Figure 2.5). It is an arresting image, and beautifully executed, but, like the rest of the Slave Song Series, it seems to me the work of a highly skilled technician, whereas the earlier Blues and Negro Folk Songs paintings reveal an artist of exceptional boldness and originality. During that unfortunate thirty-year hiatus, Piper’s interest in the abstract seems to have slipped away, and with it much of her earlier formal daring: her later work is often witty and compassionate but, in terms of its formal qualities, for this viewer at least, the thrill is gone.

Figure 2.5 Rose Piper, I Want Yuh to Go Down, Death, Easy/An’ Bring My Servant Home. 1988. From the Slave Song Series. Acrylic on masonite, 12 in. × 9 in. © Rose Piper Estate. Collection of Khela Ransier. Courtesy of Lynn E. DeRosa, Primavera Gallery.

In contrast, the 1940s canvases, I think, mark a decisive moment, when Piper brought together the abstraction that was in the air and the blues that she heard on disc to create some of the most remarkable American artworks of the mid-twentieth century. No doubt her imagination, her talent as a painter, and her knowledge of art history played crucial roles; but it was listening to her blues records that defined her subject matter, that reaffirmed her political ideals, and that helped to shape her aesthetic choices. She put the blues on her brush, and sixty years later they continue to resonate from the canvas.

To see more work by Rose Piper and to hear Ma Rainey’s recording of “Grievin’ Hearted Blues,” courtesy of Document Records, please go to the Hearing Eye Web site at www.oup.com/us/thehearingeye.

I would particularly like to thank Khela Ransier, Ann Eden Gibson, and Lynn DeRosa for their exceptional generosity and support in providing the materials that made this chapter possible.—GL

1. The story of how Smith came to write “Backwater Blues” is related by her sister-in-law Maud in Chris Albertson, Bessie: Empress of the Blues (1972; rev. and exp. ed., New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 146. The song was recorded on 17 February 1927 in New York City and is currently available on Bessie Smith, The Complete Recordings, Volume 3 (Columbia/Legacy C2K 47474, 1992). A backwater was an area, often inhabited by black people, that would be deliberately flooded to divert the floodwaters from damaging other areas, often inhabited by white people. Modern variations on this practice are alleged to have taken place when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005. See Julian Borger, “Behind the Facade, a City Left to Rot,” Guardian 29 August 2006: 3.

2. Sterling A. Brown, “Ma Rainey,” The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown, ed. Michael S. Harper (1980; reprint, Evanston, IL: TriQuarterly/Northwestern University Press, 2000), 62–63.

3. There are brief references to Piper in several books on African American art, but the only extended discussion of her work I have seen is in Ann Eden Gibson, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), esp. 110–12, 138–39; and the same author’s essay “Two Worlds: African American Abstraction in New York at Mid-Century,” in The Search for Freedom: African American Abstract Painting 1945–75, exhibition catalogue (New York: Kenkeleba Gallery, 1991), 11–53. (The latter is hard to find since it was never officially issued, following a dispute over the quality of the printing.)

4. Previous canvases that referred to the music, such as Archibald Motley’s Blues and William Johnson’s Street Musicians, tended to depict live performance. There are earlier examples of American painters inspired by recordings: for example, Arthur Dove did a series of works in 1927 in response to discs by the Paul Whiteman Orchestra of compositions by George Gershwin and Irving Berlin—but these were not blues and Dove’s canvases were wholly non-figurative. They were experiments at creating a painterly equivalent to musical performance that he based on “a rather literal lexicon for visualizing musical sounds: line describes melody and tempo, color the instrumentation, hue and line density the loudness or softness of sounds.” See Donna M. Cassidy, Painting the Musical City: Jazz and Cultural Identity in American Art, 1910–1940 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997), 85–87.

5. The published material on Piper contains numerous minor discrepancies in names, titles, dates, and the like. Wherever possible, I have consulted the relevant original documents. I am also extremely grateful for the information provided by Piper’s daughter, Khela Ransier. Although I was fortunate enough to meet Rose Piper herself in New York in 2003 and 2004, her memory had so deteriorated by that time that she was unable to answer most of my queries about her life and work.

6. In some reference books, Piper’s middle name is listed as Theodosia, although certainly in the 1940s (in grant applications, for example) she gave her middle name as Theodora. According to Khela Ransier, “In her last passport, her middle name is Theodosia, while in her divorce and marriage papers from 1959, the middle name is Theodora. Her birth certificate does not include a middle name, so now who knows the truth?”

7. Ann Eden Gibson, taped interview with Rose Piper, New York City, 8 June 1989. I am extremely grateful to Professor Gibson for sending me a recording of this interview.

8. Rose Piper, “Statement of Plan of Work,” application for a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for 1946, Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection, Box 440, Fisk University Library, Nashville, Tennessee. My thanks to my colleague Richard H. King for seeking out the Fisk material relating to Piper’s applications for Rosenwald Fellowships in 1946 and 1947.

9. Piper, “Report of Progress under Grant,” 2, Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection.

10. The title has been given incorrectly in some recent publications. Blues and Negro Folk Songs is the title that appears on the RoKo Gallery’s publicity material for the exhibition and in the initial press coverage. See RoKo Gallery file, Box 5, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. The exhibition was initially scheduled to close on 23 October but was extended for a further week. See ibid.

11. These are the titles as listed at the time of the exhibition. Back Water has more recently been referred to as Backwater Blues.

12. On the back of an undated black-and-white photograph of Subway Nuns, Piper (or someone) has written: “Two nuns on the subway / Begging blood at corners / Back to back.” O’Higgins’s poem, as published in 1948, was called “Nun on the Subway” and the relevant lines read: “ . . this way she listens for the gourd / and waits to join the dead who / wander clockwise / begging blood at corners back to back . . ” (ellipses in original), in Robert Hayden and Myron O’Higgins, The Lion and the Archer: Poems (n.p.: Counterpoise, 1948), n.p. The painting’s current whereabouts are unknown. My thanks to Khela Ransier for sending me the photograph of Subway Nuns.

13. Ann Eden Gibson has suggested that Piper’s interest in, and success with, blues subjects may have prompted Alston’s Blues Singer I–IV series of paintings (all of women) in the early 1950s. See Gibson, “Two Worlds,” 26.

14. Gibson, interview with Piper.

15. “The Annual Art Exhibit,” Atlanta University Bulletin, 3.63 (July 1948): 7, 17–18.

16. These names are taken from the list of works in the original exhibition catalogue. Contrary to some other reports, no works by either Charles Alston or Romare Bearden are listed. My thanks to Tina Dunkley at Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries for supplying this and other documents.

17. Gibson, interview with Piper.

18. Unidentified press clipping headed “Folk Songs Told in Paint and Canvas,” RoKo Gallery file, Box 5, AAA; Piper, “Report of Progress under Grant,” 2.

19. Romare Bearden, letter of reference in support of Piper’s 1947 application for a Rosenwald Fellowship, Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection.

20. Clipping from Art News, November 1947, in RoKo Gallery file, Box 5, AAA.

21. Quoted in Kirsten Mullen, “Rose Piper,” To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities, ed. Richard J. Powell and Jock Reynolds, exhibition catalogue (Andover and New York: Addison Gallery of American Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, 1999), 220.

22. Piper, “Statement of Plan of Work.”

23. Ibid.

24. According to Piper, “the single canvas has usually been directly associable with a more or less specific portion of the blues or the folk songs.” “Report of Progress under Grant,” 2. As far as I am aware, five of the RoKo paintings refer to particular blues titles and Piper has matched three of them to specific recordings: these are “Backwater Blues” and “Empty Bed Blues” by Bessie Smith and “Freight Train Blues” by Trixie Smith. The other two recordings I assume are relevant here are “Grievin’ Hearted Blues” by Ma Rainey and “St. Louis Cyclone Blues” by Elzadie Robinson (the latter was also recorded by Lonnie Johnson). I have not included Piper’s St. Louis Cyclone Blues in this discussion because I have seen only a black-and-white photograph of it. The painting’s current whereabouts are unknown and no color reproduction is believed to exist. (The black-and-white photograph can be seen on the Hearing Eye Web site, courtesy of Khela Ransier.)

25. The original canvas of Back Water is currently held in Kenkeleba House in New York City. I am very grateful to Corrine Jennings at Kenkeleba House for allowing me to see the painting, even though it is not on public show. It is certainly better viewed in situ because I doubt any reproduction could do justice to Piper’s subtle uses of color here, particularly in the clothing of the main figure.

26. We do not know the exact order in which the paintings were made. Khela Ransier, in personal correspondence, says her mother dated Back Water and Empty Bed Blues to 1946 and the remaining RoKo paintings to 1947. However, in a letter written in 1990, Piper states that Slow Down, Freight Train was painted in 1946. Since this is one of the more abstract works in the series, we should perhaps be wary of imposing a simple linear chronology on Piper’s move toward abstraction. See Piper, letter to Charles Millard, 1 August 1990, Ackland Art Museum archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. My thanks to Tammy Wells-Angerer at Ackland Art Museum for sending me a copy of this letter and other documents.

27. Bessie Smith, “Backwater Blues.”

28. Charles Millard, letter to Rose Piper, 25 July 1990, Ackland Art Museum archives.

29. Piper, letter to Charles Millard.

30. The information about the different versions of “Freight Train Blues” comes from Rosetta Reitz, liner notes to Sorry but I Can’t Take You: Women’s Railroad Blues (LP; Rosetta Records RR 1301, 1980). The LP includes Trixie Smith’s 1938 version of “Freight Train Blues” and the 1924 version of the song as recorded by Clara Smith. Trixie Smith’s 1924 recording can be heard on her Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, Vol. 1 (1922–1924) (Document Records DOC-5332, 1995).

31. Quoted in undated publicity material from the Ackland Art Museum.

32. Piper, “Statement of Plan of Work.”

33. I am thinking, for example, of Sterling Brown’s description of the best blues imagery as “highly compressed, concrete, imaginative, original.” Sterling A. Brown, “The Blues as Folk Poetry” (1930), reprinted in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, ed. Robert G. O’Meally (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 549. Blues form, too, could be characterized as stylized and distilled.

34. Mullen, “Rose Piper,” 220.

35. Ma Rainey, “Grievin’ Hearted Blues,” Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, Volume 4, c. November 1926 to c. December 1927 (Document Records DOCD 5584, 1997). The guitarist is Blind Blake, the violinist probably Leroy Pickett. Rainey did not write this blues herself; the composer is unknown. (The track can be heard on the Hearing Eye Web site, courtesy of Document Records.)

36. Ibid.

37. Mullen, “Rose Piper,” 220.

38. While looking at a reproduction of Grievin’ Hearted, Piper says, “This was an interlude when Bill Piper [her first husband, whom she married in 1940] was in the navy. But I was not alone. I was living with a poet and this is the poet I fell in love with, Myron O’Higgins. He wrote poetry, I was a painter—it was idyllic! [Laughs.] It was great.” Gibson, interview with Piper. In 1948 O’Higgins published a poem entitled “Two Artists at Odds,” which includes the lines:

and there between those slender

towers is the house that he would swear

was gray

and she would argue it were green […]

there on the steps he sits and looks

up far beyond the rooftops

and she looks down and fastens every line

to moorings

and transforms sound into a screeching red,

and thin and thinning yellow borrow blue

and black and green to build the mood…

(last ellipses in original), in Hayden and O’Higgins, The Lion and the Archer: Poems, n.p. Since very little seems to be known about Myron O’Higgins, I should report that Rose Piper told me his real name was Higgins—the O’ was, she said, just an affectation—and Khela Ransier later told me she had found a Departures book among her mother’s effects, in which O’Higgins was listed as having died in 1978. That Piper had noted his passing, some thirty years after their breakup, presumably reflects the depth of the feelings she had once had for him, and which is certainly evident in the painting.

39. Gibson, interview with Piper.

40. Gibson, Abstract Expressionism, 111.

41. Angela Y. Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (New York: Vintage, 1999), 21.

42. I wonder if this was a consideration in Slow Down, Freight Train, too, where, unlike the recording of “Freight Train Blues,” Piper’s focus is on the man’s feelings of loss at the separation from his lover.

43. The issue is further complicated by information from Khela Ransier, who reports that her mother had “abandonment, or perceived abandonment, issues,” which probably stemmed “from the death of her identical twin sister, Virginia, when they were about a month from their eleventh birthday.” This may partly explain why many of Piper’s paintings deal with feelings of loss, separation, and abandonment, even while she emphasized her independence, and it suggests that her attraction to the blues was multifaceted—its articulation of loss, its defiant voice, and its aesthetic template of stylization and distillation were all valuable resources for her art.

44. Gibson, Abstract Expressionism, 139.

45. I have seen only a black-and-white photograph of Empty Bed Blues. The painting is in a private collection and, as far as I am aware, no color reproductions are in circulation. (The photograph can be seen on the Hearing Eye Web site, courtesy of Khela Ransier.)

46. Gibson, Abstract Expressionism, 111, 225 (n. 72). It was widely believed, and reported, that Smith bled to death because a whites-only hospital refused to treat her after she sustained serious injuries in a car crash. We now know this was not the case; see Albertson, 255–67.

47. Bearden, letter of reference.

48. My thanks to Khela Ransier for supplying a copy of this document.

49. Myron O’Higgins, “Blues for Bessie,” in Blues Poems, ed. Kevin Young (London: Everyman’s Library, 2003), 235, 237. Although I have not been able to ascertain when the poem was written, it had been published by 1945 (in Paris), so it definitely predates the painting.

50. O’Higgins,“Blues for Bessie,” 236.

51. Piper, “Report of Progress under Grant.”

52. Piper, “Plan of Work,” application for a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for 1947.

53. This information comes from Khela Ransier, who speculates that many more paintings (presumably untitled or unfinished) may have been destroyed at the same time. The title Ain’t Got Nothin’ suggests to me that this painting may have been intended for the RoKo show. Draft publicity for the exhibition does mention that fifteen works would be shown, whereas in the event only fourteen were included, so possibly Ain’t Got Nothin’ was either not finished in time or withdrawn by Piper for some reason. A black-and-white photograph of the painting has survived; on the evidence of that, I would say this was one of Piper’s weakest paintings, and I think it possible she could have withdrawn it for that reason.

54. Gibson, interview with Piper. The husband she mentions here is her second husband, Glenn Ransier, whom she married in 1947 after divorcing Bill Piper in 1946. She later divorced Ransier and in 1959 married her third husband, George Wheeler.

55. See Textiles Designers, dir. Michelle Hill, video, Cinque Gallery, 1995.

56. Gibson, interview with Piper.

57. I am extremely grateful to Lynn DeRosa, who went to considerable trouble to send me all the slides and lyrics pertaining to these paintings as well as various associated publicity materials. Ms. DeRosa, who is now retired, was director of the Primavera Gallery in Huntingdon, New York, which exhibited Piper’s work in the 1990s. My thanks also to Tammi Lawson at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture for the documentation that led me to Lynn DeRosa.

58. The information in this paragraph comes chiefly from publicity material from the Primavera Gallery, kindly supplied by Lynn DeRosa.

59. Quoted in publicity material from the Primavera Gallery. It is not clear whether Piper wrote this herself or is quoting Lovell.

60. Quoted in a 1995 curriculum vitae for Piper, kindly supplied by Khela Ransier.

Rainey, Ma. Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, Volume 4, c. November 1926 to c. December 1927. Document Records DOCD 5584, 1997.

Smith, Bessie. The Complete Recordings, Volume 3. Columbia/Legacy C2K 47474, 1992.

Smith, Trixie. Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, Volume 1 (1922–1924). Document Records DOCD-5332, 1995. Sorry but I Can’t Take You: Women’s Railroad Blues. LP. Rosetta Records RR 1301, 1980.

Albertson, Chris. Bessie: Empress of the Blues. 1972. Revised and expanded edition, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

“The Annual Art Exhibit.” Atlanta University Bulletin, 3.63 (July 1948): 7, 17–18.

Art News. Unidentified clipping from November 1947. RoKo Gallery file. Box 5. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Bearden, Romare. Letter of reference in support of Rose Piper. Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection. Box 440. Fisk University Library, Nashville, Tennessee.

Borger, Julian. “Behind the Facade, a City Left to Rot.” Guardian 29 August 2006: 3.

Brown, Sterling A. “The Blues as Folk Poetry.” 1930. In The Jazz Cadence of American Culture. Ed. Robert G. O’Meally. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. 540–51.

———. The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown. Ed. Michael S. Harper. 1980.

Reprint, Evanston, IL: TriQuarterly/Northwestern University Press, 2000.

Cassidy, Donna M. Painting the Musical City: Jazz and Cultural Identity in American Art, 1910–1940. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997.

Davis, Angela Y. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism. New York: Vintage, 1999.

Gibson, Ann Eden. Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

———. Taped interview with Rose Piper. New York City, 8 June 1989.

———. “Two Worlds: African American Abstraction in New York at Mid-Century.” In The Search for Freedom: African American Abstract Painting 1945–75. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Kenkeleba Gallery, 1991. 11–53.

Hayden, Robert, and Myron O’Higgins. The Lion and the Archer: Poems. N.p: Counterpoise, 1948.

Millard, Charles. Letter to Rose Piper. 25 July 1990. Ackland Art Museum archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Mullen, Kirsten. “Rose Piper.” In To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Ed. Richard J. Powell and Jock Reynolds. Exhibition catalogue. Andover and New York: Addison Gallery of American Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, 1999. 219–20.

O’Higgins, Myron.“Blues for Bessie.” In Blues Poems. Ed. Kevin Young. London: Everyman’s Library, 2003. 235–37.

———.“Nun on the Subway.” In Hayden and O’Higgins, The Lion and the Archer, n.p.

———. “Two Artists at Odds.” In Hayden and O’Higgins, The Lion and the Archer, n.p.

Piper, Rose. Curriculum Vitae. 1995.

———. Letter to Charles Millard. 1 August 1990. Ackland Art Museum archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

———. “Plan of Work.” (1947 application.) Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection. Box 440. Fisk University Library, Nashville, Tennessee.

———. “Report of Progress under Grant.” Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection.

———. “Statement of Plan of Work.” (1946 application.) Julius Rosenwald Fund Collection.

Reitz, Rosetta. Liner notes. Sorry but I Can’t Take You: Women’s Railroad Blues. LP. Rosetta Records RR 1301, 1980.

Textiles Designers. Dir. Michelle Hill. Cinque Gallery, 1995.